Abstract

It is generally held that inhibition of mammalian sterile 20-like kinase 1 (Mst1) protects the heart through reducing myocyte apoptosis. We determined whether inhibition with a dominant-negative Mst1 (DN-Mst1) would protect against the cardiomyopathy induced by chronic β1-adrenergic receptor (β1-AR) stimulation by preventing myocyte apoptosis. DN-Mst1 mice were mated with β1-AR transgenic (Tg) mice and followed for 20 months. β1-AR Tg mice developed cardiomyopathy as they aged, as reflected by premature mortality and depressed cardiac function, which were rescued in β1-AR × DN-Mst1 bigenic mice. Surprisingly, myocyte apoptosis did not significantly decrease with Mst1 inhibition. Instead, Mst1 inhibition predominantly reduced non-myocyte apoptosis, e.g., fibroblasts, macrophages, neutrophils and endothelial cells. Fibrosis in the hearts with cardiomyopathy increased fivefold and this increase was nearly abolished in the bigenic mice with Mst1 inhibition. Regression analysis showed no correlation between myocyte apoptosis and cardiac function or myocyte number, whereas the latter two correlated significantly, p < 0.05, with fibrosis, which generally results from necrosis. To examine the role of myocyte necrosis, chronic β-AR stimulation with isoproterenol was induced for 24 h and myocyte necrosis was assessed by 1 % Evans blue dye. Compared to WT, DN-Mst1 mice showed significant inhibition, p < 0.05, of myocyte necrosis. We confirmed this result in Mst1-knockout mice, which also showed significant protection, p < 0.05, against myocyte necrosis compared to WT. These data indicate that Mst1 inhibition rescued cardiac fibrosis and myocardial dysfunction in β1-AR cardiomyopathy. However, this did not occur through Mst1 inhibition of myocyte apoptosis but rather by inhibition of cardiomyocyte necrosis and non-myocyte apoptosis, features of Mst1 not considered previously.

Keywords: β-Adrenergic receptor, Mammalian sterile 20-like kinase 1, Cardiomyopathy, Apoptosis, Necrosis

Introduction

Mammalian sterile 20-like kinase 1 (Mst1) is a serine/threonine kinase of the Hippo signaling pathway, with regulating apoptosis as one of its major functions [4, 11, 12, 25]. Prior studies in the heart concluded that Mst1 induces cardiac damage through activating myocyte apoptosis and that inhibiting Mst1 is cardioprotective by reducing myocyte apoptosis [5, 6, 27, 31, 45]. The tacit assumption is that Mst1 regulates cardiomyocyte numbers, thereby affecting cardiac function, but this has rarely been measured. To investigate this concept, we examined the extent to which the cardiomyopathy induced by chronic β1-adrenergic receptor (β1-AR) signaling in β1-AR transgenic (Tg) mice [8] was rescued by mating them with dominant-negative Mst1 mice (DN-Mst1) [45]. Our first goal was to determine whether the rescue should occur through reducing apoptosis of myocytes. Given that 75 % of the cells in the heart are non-myocytes [17], we discriminated the effects of the cardiomyopathy and its rescue with DN-Mst1 on myocyte vs. non-myocyte apoptosis. The finding that apoptosis predominantly occurred in non-myocytes and DN-Mst1 predominantly rescued non-myocyte apoptosis, supports the hypothesis that DN-Mst1 protects against necrosis, since non-myocytes, e.g., fibroblasts, macrophages, neutrophils, endothelial cells [33, 34, 36, 40], are all known to be involved in inflammation [9, 18, 39], which is more closely coupled to necrosis, rather than apoptosis [7, 10, 20, 22, 29, 38]. In further support of the role of necrosis, we also found that myocardial fibrosis, which is generally thought to be an outcome of necrosis rather than apoptosis [3, 10], was also rescued in the bigenic mice. Finally, we examined whether Mst1 inhibition could prevent necrotic myocyte death. To accomplish this, we subjected DN-Mst1 mice, as well as Mst1-knockout (Mst1-KO) mice to chronic isoproterenol (ISO) challenge and assessed necrotic myocyte injury by in vivo labeling with Evans blue dye (EBD).

Materials and methods

Animals

The development and characterization of mice with cardiac-specific overexpression of β1-AR and DN-Mst1 have been described previously [8, 45]. β1-AR Tg mice were a generous gift from Dr. Stefan Engelhardt from the University of Wüerzburg. β1-AR Tg mice were backcrossed to B6SJL background for seven generations and the resulting mice were mated with DN-Mst1 mice (C57BL6 background) to generate WT, DN-Mst1 Tg, β1-AR Tg and β1-AR × DN-Mst1 bigenic mice (B6SJL-C57BL6 mixed background). In studies involving old mice, age-matched WT, DN-Mst1 Tg, β1-AR Tg and β1-AR × DN-Mst1 bigenic littermates, with an average age of 18–20 months were used. Mst1-knockout (Mst1-KO) mice (C57BL6-129Sv) [47] were a generous gift from Dr. Joseph Avruch from Harvard Medical School. Animals used in this study were maintained in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 8th Edition 2011). All animal care and protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Rutgers-New Jersey Medical School, Newark, New Jersey, USA.

Measurement of cardiac function

Two-dimensional echocardiography was performed in mice using ultrasonography (Accuson 256, Siemens Medical Solutions) with a 13-MHz linear ultrasound transducer. Left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), LV end-systolic diameter (LVESD), LV fractional shortening (FS), and LV ejection fraction (EF) and LV anterior and posterior wall thickness in systole (LVAWs, LVPWs, respectively) were measured. Cardiac catheterization was performed using a Millar micromanometer in the LV to measure LV systolic pressure (LVSP) and LV end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP). LV systolic wall stress (kdyn/cm2) was calculated as: (1.35 × LVSP × LVESD)/[4 × LVPWs × (1 + LVPWs/LVESD)].

Detection of apoptosis

Tissue samples were fixed with 10 % neutral buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Apoptosis was detected by TUNEL assay (Roche). To discriminate apoptosis in myocytes and non-myocytes, tissue sections (5 µm thickness) were co-stained with rhodamine-conjugated wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) (Vector Laboratories) or Troponin I (TnI, Thermo Scientific), a myocyte marker, as previously described [33, 34]. Nuclei were visualized by ProLong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen). Apoptotic rate was expressed as the percentage of TUNEL positive cells of interest per myocyte or non-myocyte nuclei. Myocyte apoptosis was also confirmed by western blot analysis measuring cleaved caspase-3 level in isolated cardiomyocytes.

Detection of fibrosis

To examine collagen deposition, LV sections were stained with Masson’s trichrome or picrosirius red (PSR). The percentage of fibrosis in LV sections stained with PSR was manually quantified on ImagePro-Plus software.

Detection of myocyte necrosis induced by chronic ISO challenge

Isoproterenol (Sigma-Aldrich) was subcutaneously delivered to WT, DN-Mst1 and Mst1-KO mice (average age of 6 months) by mini-osmotic pumps (ALZET model 2001, DURECT Corp, Cupertino, CA, USA) at a dose of 60 mg/kg/day as described [23] for 24 h. Immediately after pump implantation, WT, DN-Mst1 and Mst1-KO mice were injected with 1 % Evans blue dye (EBD) via tail-vein at a dose of 100 mg/kg [28]. After 24 h, animals were killed. LV was mounted in Tissue-Tek OCT compound (Sakura, Torrance, CA, USA) and frozen in isopentane pre-cooled in liquid nitrogen. Cryostat sections (10 µm thickness) were counterstained with WGA Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate (Invitrogen) and EBD positive myocytes were quantified. Necrotic myocytes were presented as percentage of EBD positive myocytes per myocyte nuclei.

Detection of inflammatory cells

Left ventricular sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to visualize infiltrating inflammatory cells.

Calculation of myocyte number

The total number of LV myocytes was measured by the modified method of Olivetti et al. [32], as reported previously [34].

Isolation of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes and cell culture

Primary cultures of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes were prepared from 1-day-old Wistar rats. Briefly, ventricular myocytes were enzymatically dissociated and pre-plated for 1 h to enrich for myocytes. Cells were plated onto gelatin-coated culture dishes and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 5 % horse serum. Culture medium was changed to serum-free media after 24 h. The cells were further cultured under serum-free conditions for 24 h and then treated with the β-AR agonist, ISO (50 µM).

Isolation of adult cardiac myocytes

Adult cardiomyocytes were isolated from Langendorff-perfused mouse hearts as previously described [16]. Briefly, hearts were perfused with enzyme solution containing 1 mg/ml collagenase (type II; Worthington), 0.1 mg/ml protease (type XIV; Sigma) and 10 µM blebbistatin (Toronto Research Chemicals) followed by washing. Digested hearts were removed from the apparatus, placed in a culture dish and mechanically disrupted to release free myocytes. Ca2+ was gradually added to a final concentration of 1.0 mM.

Mst1 kinase assay

Left ventricular tissue homogenates were incubated overnight with anti-Mst1/2 antibody and followed by Protein G–Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences) for an additional 2 h to precipitate endogenous Mst1. After washing, the beads were incubated with [γ-32P]ATP (PerkinElmer) and 5 mg substrate myelin basic protein (MBP) in 2× kinase assay buffer [40 mM Hepes/NaOH pH 7.4, 20 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT (dithiothreitol), 1 mM ATP, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 50 mM sodium fluoride and complete protease inhibitor (Roche)] at 30 °C for 20 min. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 0.5 volumes of 3 × Laemmli sample buffer. The samples were incubated at 95 °C for 5 min., resolved on SDS/PAGE (12 % gels) and analyzed by autoradiography.

Matrix metallopeptidase 2 (MMP-2) activity assay

Matrix metallopeptidase 2 activity was measured in LV homogenates using MMP-2 Biotrak Activity Assay (GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

Cellular subfractionation and western blot analysis

Cell fractions from cardiac tissue homogenates were separated by sequential centrifugations at 4 °C, including: 500×g for 5 min (nuclei), 30,000×g for 10 min in the presence of 0.25 M sucrose/15 mM NaCl (mitochondria), 100,000×g for 90 min (plasma membrane). The final supernatant contained the cytosolic fraction. Protein extracts were denatured in sample loading buffer by boiling, resolved on 4–20 % SDS/PAGE, and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane. Immunoblotting was performed using antibodies to Mst1, NFκB, IL-1 from Cell Signaling. Immunodetection was visualized by chemiluminescence (ECL) kit (Amersham Biosciences) and protein expression was quantified by densitometry.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± SEM. To compare two independent groups, we used Student’s unpaired t test. For comparisons among three or more groups, one-way ANOVA with Holm Sidak post hoc test was used. Survival analysis was performed by the Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, log rank test. For correlation studies, linear regression analysis was performed, examining the slopes of the relationship and the statistical significance of the correlations. p < 0.05 was taken as a minimal level of significance for all statistical tests.

Results

Mst1 inhibition rescues β1-AR cardiomyopathy

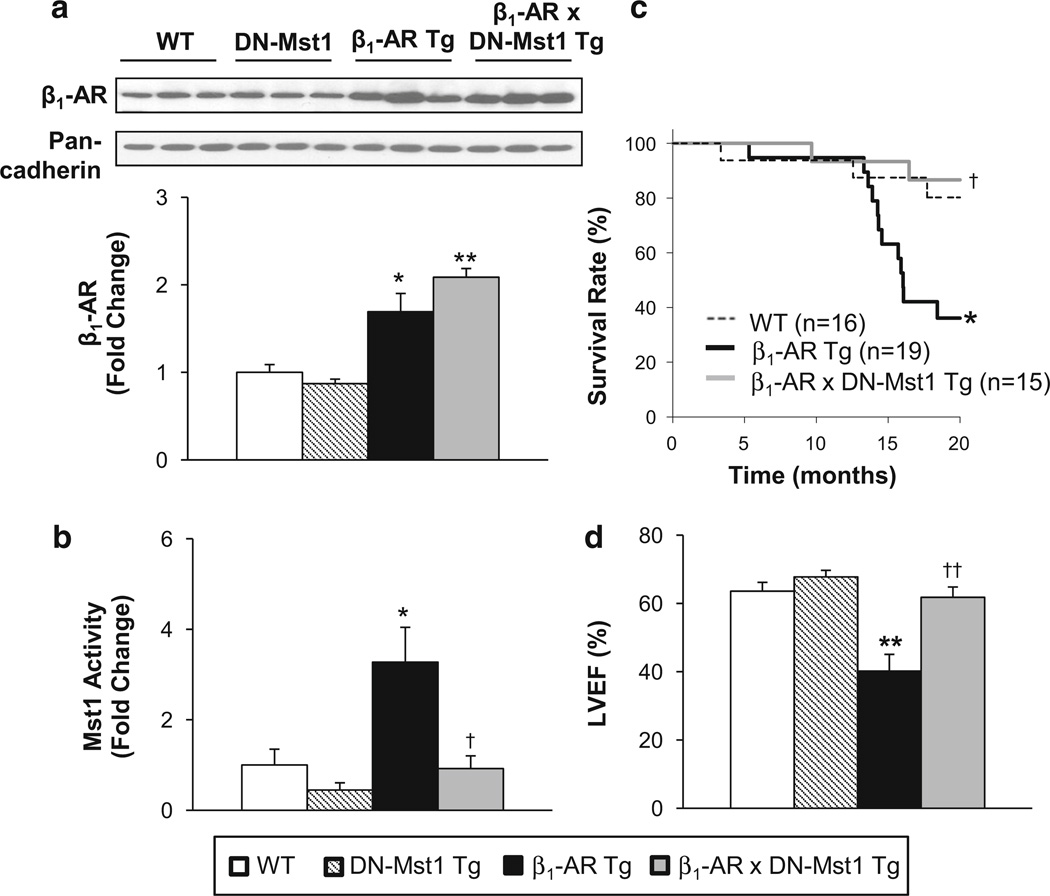

Compared to WT, β1-AR Tg mice had significantly increased β1-AR protein levels in the heart, which was maintained in the bigenic mice. However, the increased cardiac Mst1 activity in β1-AR Tg mice was absent in the bigenic mice (Fig. 1a, b). We followed the mice for 20 months and assessed their survival by Kaplan–Meier analysis. Whereas β1-AR Tg mice showed premature mortality beginning at the age of 13 months, the bigenic mice showed a marked improvement in survival, p < 0.05, which was no longer different from that in WT mice (Fig. 1c). The β1-AR Tg mice developed cardiomyopathy as they aged, as reflected by increased myocardial fibrosis (Fig. 3b), increased lung/body weight ratio (5.9 ± 0.5 vs. 4.8 ± 0.2, p < 0.05) and LV weight/body weight ratio (3.8 ± 0.3 vs. 3.3 ± 0.1, p < 0.05) without a difference in body weight. Additionally, cardiac function was reduced: compared to old WT, age-matched β1-AR Tg mice showed reduced LV ejection fraction (Fig. 1d), decreased LV fractional shortening and LV wall thickness, and increased and heart rate (Table 1). In old bigenics, LV ejection fraction (Fig. 1d), LV fractional shortening, and LV wall thickness were all rescued (Table 1). No differences were observed between old DN-Mst1 and age-matched WT. LV wall stress was not different in WT and DN-Mst1 (60 ± 6 vs. 54 ± 4 kdyn/cm2), but doubled, p < 0.05, in β1-AR Tg (115 ± 20 kdyn/cm2) and was rescued in old bigenics (51 ± 4 kdyn/cm2).

Fig. 1.

Mst1 rescues β1-AR cardiomyopathy. a Western blot analysis shows maintained β1-AR expression level in β1-AR × DN-Mst1 mice compared to β1-AR mice. b Mst1 activity was significantly decreased in β1-AR × DN-Mst1 mice compared to β1-AR mice. c Kaplan–Meier survival curves show a significant increase in survival in β1-AR × DN-Mst1 mice compared to β1-AR mice (log rank test). d Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was preserved in old β1-AR × DN-Mst1 mice compared to β1-AR Tg mice. n = 8–10/each group. *p < 0.05 vs. WT; **p < 0.01 vs. WT; †p < 0.05 vs. β1-AR Tg; ††p < 0.01 vs. β1-AR Tg (ANOVA)

Fig. 3.

Mst1 inhibition reduces cardiac fibrosis in β1-AR mice. a Representative image of LV sections stained with Masson’s trichrome. b Quantification of fibrosis from LV sections stained with picrosirius red (PSR) reveals significant decrease of cardiac fibrosis in β1-AR × DN-Mst1 mice compared to β1-AR mice. n = 7–8/each group. **p < 0.01 vs. WT; ††p < 0.01 vs. β1-AR Tg

Table 1.

Echocardiographic results

| WT | DN-Mst1 Tg | β1-AR Tg | β1-AR × DN-Mst1 Tg | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 9 | 8 | 8 | 10 |

| Age (months) | 18 | 18 | 18 | 20 |

| LV end-diastolic diameter (mm) | 4.3 ± 0.1 | 4.0 ± 0.1 | 4.9 ± 0.3 | 4.1 ± 0.1 |

| LV end-systolic diameter (mm) | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 4.2 ± 0.4* | 2.9 ± 0.1 |

| LV systolic anterior wall thickness (mm) | 1.31 ± 0.04 | 1.23 ± 0.08 | 1.10 ± 0.05* | 1.29 ± 0.06 |

| LV systolic posterior wall thickness (mm) | 1.05 ± 0.06 | 1.07 ± 0.07 | 0.85 ± 0.03* | 1.04 ± 0.04 |

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 64 ± 3 | 68 ± 2 | 40 ± 5* | 62 ± 3 |

| Fractional shortening (%) | 29 ± 2 | 32 ± 1 | 16 ± 2* | 28 ± 2 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 433 ± 18 | 445 ± 32 | 508 ± 22* | 496 ± 19 |

p < 0.05 vs. WT

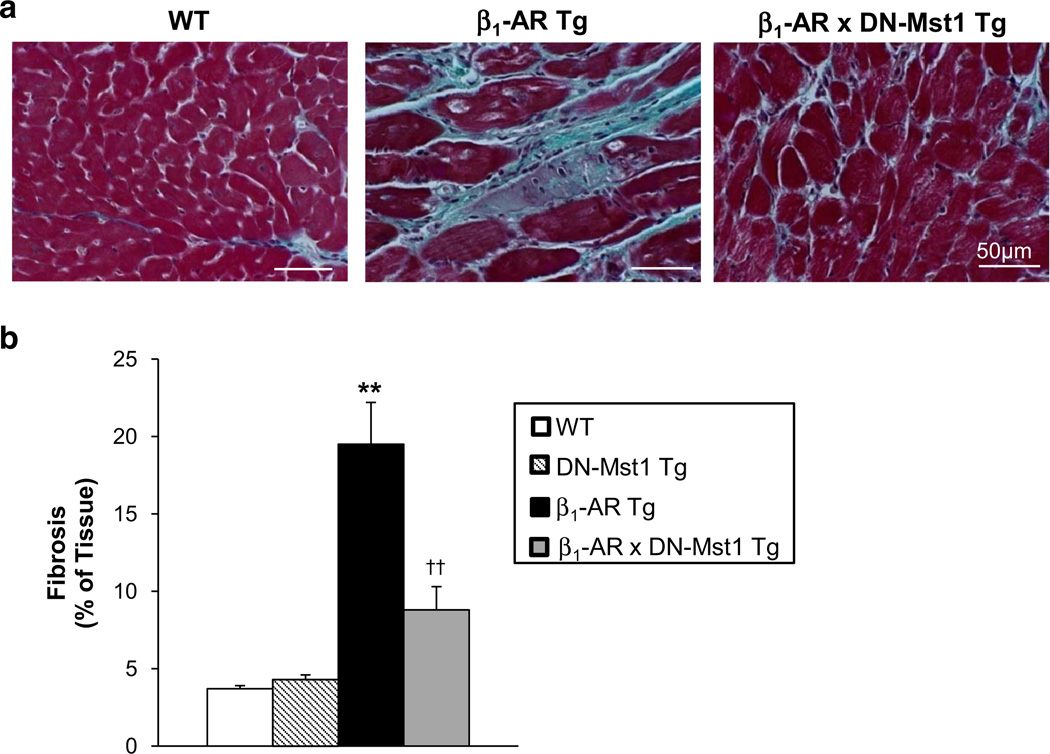

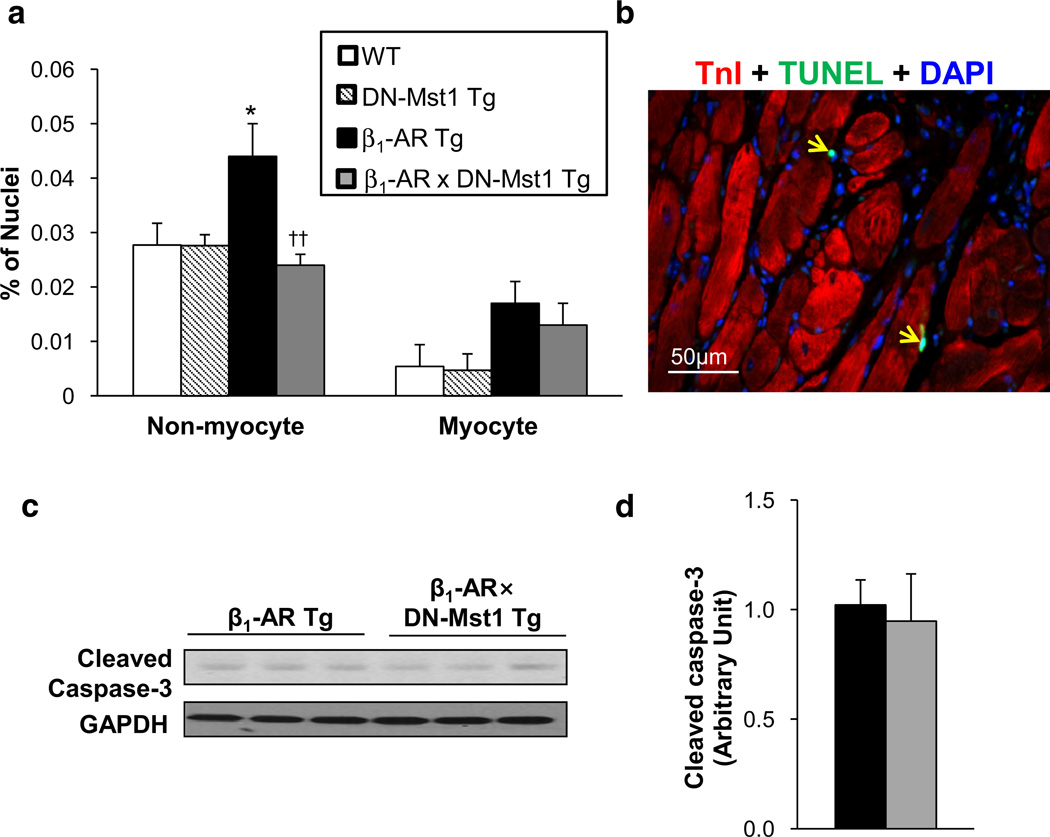

Mst1 inhibition does not protect against myocyte apoptosis

Total apoptotic cells in the heart increased almost twofold in old β1-AR Tg mice compared to age-matched WT, and were rescued in the bigenic mice. The goal of this study was to examine myocyte-specific apoptosis and non-myocyte apoptosis. Co-staining with TnI or WGA to distinguish myocytes from non-myocytes (Fig. 2b) revealed that 95 % of the increase in apoptosis occurred in non-myocytes (Fig. 2a); whereas, myocyte apoptosis comprised only 5 % of the increase in total apoptosis. Conversely, the rescue of apoptosis in the bigenic mice was comprised of 98 % of non-myocytes and only 2 % of myocytes. In fact, the increase in myocyte apoptosis in β1-AR Tg mice (0.017 ± 0.004 %) was not significantly reduced in the bigenic mice (0.013 ± 0.004 %). In support of this finding, isolated myocytes from bigenic and β1-AR Tg hearts showed no difference in cleaved caspase-3 levels (Fig. 2c, d). We examined apoptosis in young mice (3–4 months old) and found similar results to old mice; myocyte apoptosis ranged from 0.003 to 0.009 %, with no significant differences among the groups in young mice.

Fig. 2.

Mst1 inhibition does not rescue myocyte apoptosis in β1-AR cardiomyopathy. a Quantification of TUNEL assay in LV section of old mice shows that myocyte apoptosis was not significantly rescued in β1-AR × DN-Mst1 mice. n = 8/each group. *p < 0.05 vs. WT; ††p < 0.01 vs. β1-AR Tg (ANOVA). b Representative image of TUNEL assay (green) on LV section counterstained with Tn I (red) for cardiac muscle and DAPI (blue) for nucleus. Yellow arrows indicate non-myocyte apoptosis. c Western blot analysis of cleaved caspase-3 expression in isolated myocytes from β1-AR and β1-AR × DN-Mst1 hearts. d Expression level of cleaved caspase-3 was not different in isolated myocytes from β1-AR to β1-AR × DN-Mst1 hearts

Mst1 inhibition reduces myocardial fibrosis

Left ventricular sections stained with Masson’s trichrome or PSR revealed a fivefold increase in myocardial fibrosis in old β1-AR Tg mice compared to WT (19.7 ± 2.3 vs. 3.7 ± 0.2 %, p < 0.01) (Fig. 3a, b), which was alleviated, but not abolished, in old bigenic mice (7.4 ± 0.8 %, p < 0.01).

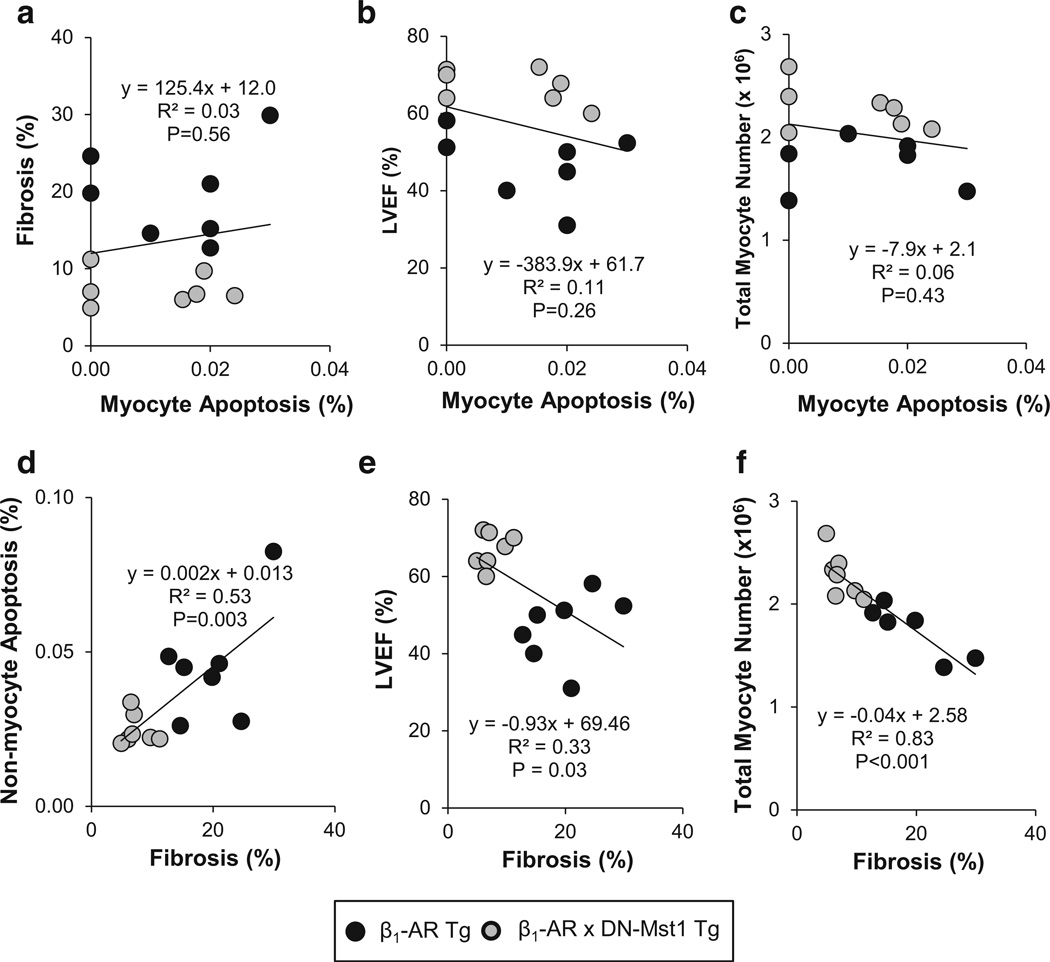

Correlations

To further clarify the role of myocyte apoptosis and fibrosis in the rescue of cardiomyopathy, we correlated these two parameters individually with each other and with LV ejection fraction. There was absolutely no correlation between myocyte apoptosis and fibrosis (p = 0.56) (Fig. 4a) nor between myocyte apoptosis and LV ejection fraction (p = 0.26) (Fig. 4b). Conversely, fibrosis correlated significantly with both non-myocyte apoptosis (p = 0.003) (Fig. 4d) and LV ejection fraction (p = 0.03) (Fig. 4e). Since the hypothesis that inhibiting Mst1 would protect the development of cardiomyopathy through reducing myocyte apoptosis is predicated on its efficacy in preserving contractile units in the heart, it was considered important to correlate myocyte apoptosis and fibrosis with total myocyte numbers in the heart. There was no correlation between myocyte apoptosis and total myocyte number (p = 0.43) (Fig. 4c); whereas fibrosis showed strong correlation with total myocyte number (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4f). These data suggest that Mst1 inhibition preserves myocyte contractile units not by preventing myocyte apoptosis, but rather by inhibiting fibrosis.

Fig. 4.

Linear regression analysis. a–c There is no significant correlation between myocyte apoptosis (%) and either fibrosis (%), LV ejection fraction (LVEF) (%), or total LV myocyte number. d–f Fibrosis was significantly correlated with non-myocyte apoptosis (%), LVEF (%), and total LV myocyte number

Mst1 inhibition reduces myocardial necrosis

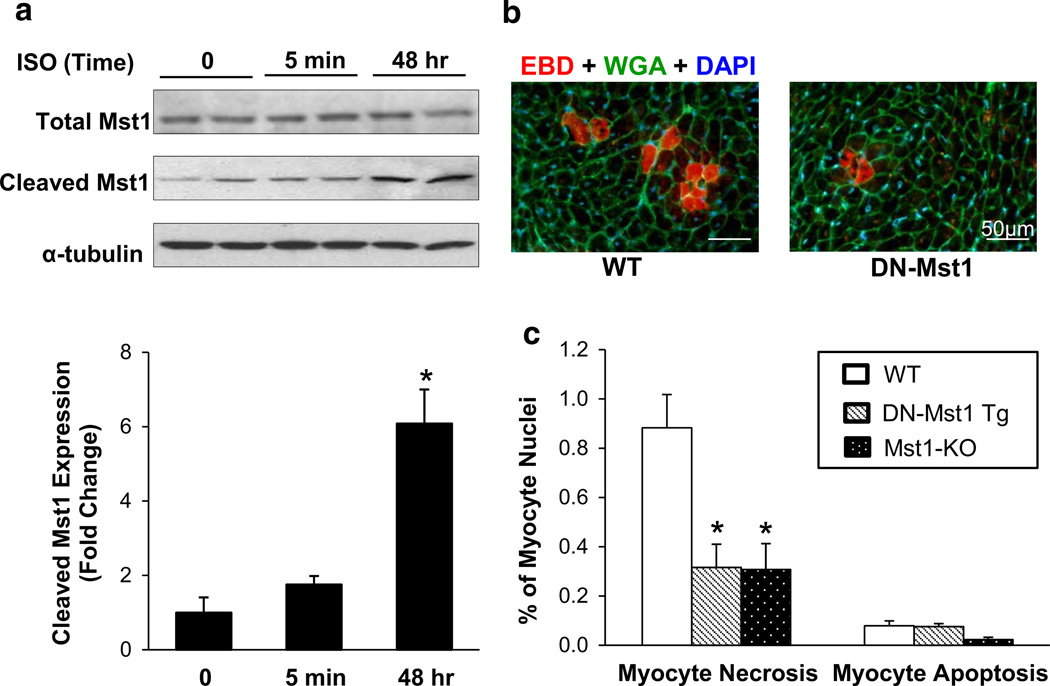

Since fibrosis is the aftermath of necrosis, rather than apoptosis [3, 10], we examined the frequency of necrotic myocytes in young DN-Mst1 and WT mice after 24 h of chronic ISO challenge, which increases Mst1 activation in vitro (Fig. 5a). In vivo labeling with 1 % EBD, which fluoresces red after binding to albumin [28], revealed massive necrotic myocyte death in WT hearts, while DN-Mst1 mice showed minimal necrotic injury (0.88 ± 0.14 vs. 0.32 ± 0.09 %, p < 0.05) (Fig. 5b, c). Apoptotic myocytes were also examined by TUNEL, which showed ninefold less positivity in comparison to necrotic myocytes in the WT. Moreover, there was no discernible difference in myocyte apoptosis between WT and DN-Mst1 mice (0.09 ± 0.03 vs. 0.08 ± 0.01 %). To further confirm these results, Mst1 knockout (Mst1-KO) mice were subjected to 24 h of chronic ISO. Mst1-KO mice, like the DN-Mst1 mice, showed significant reduction in necrotic myocytes (0.31 ± 0.11 %, p < 0.05), while having no significant effect on myocyte apoptosis (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

DN-Mst1 protects against myocyte necrosis. a Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes treated with isoproterenol (ISO; 50 µM) increased Mst1 activation in a time-dependent manner. b Representative image of Evans blue dye (red) incorporation in LV sections counterstained with WGA (green) and DAPI (blue). c Quantification of Evans blue dye (EBD) infiltrated myocytes shows that necrotic myocytes are significantly reduced in DN-Mst1 and Mst1-KO. No change in myocyte apoptosis was observed. n = 3–8/each group. *p < 0.05 vs. WT (Student t test)

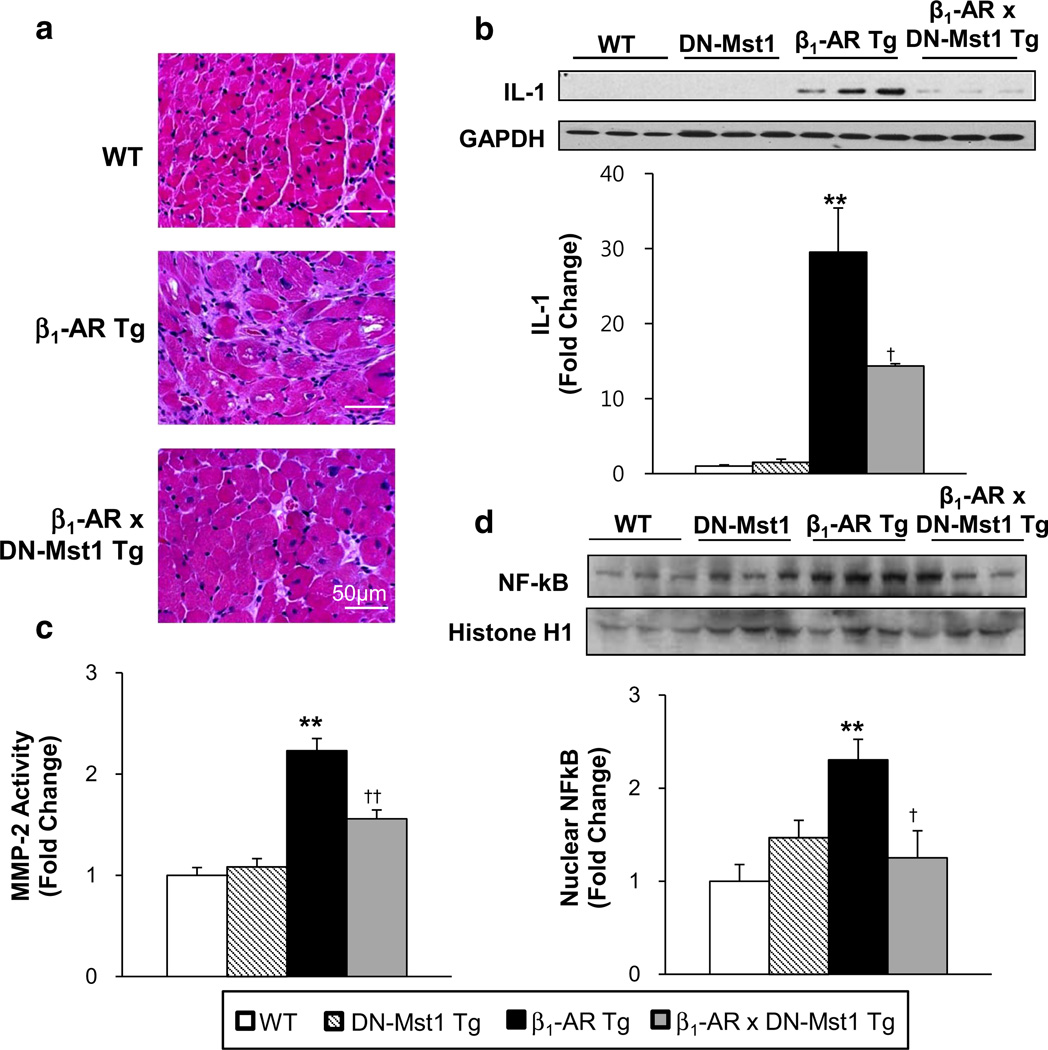

Inhibition of Mst1 reduces pro-inflammatory responses

Given the significant rescue of non-myocyte apoptosis in the bigenic mice and the fact that non-myocytes are comprised of fibroblasts, macrophages, neutrophils and endothelial cells [33, 34, 36, 40], which are involved in inflammatory processes following necrotic death [7, 10, 20, 22, 29, 38], we examined whether Mst1 inhibition attenuates pro-inflammatory mechanisms in β1-AR Tg mice. LV sections stained with H&E revealed greater inflammatory cell infiltration in β1-AR mice, while the bigenic mice only showed a modest increase (Fig. 6a). Furthermore, the proinflammatory cytokine, IL-1, was significantly elevated in β1-AR Tg hearts compared to WT, but drastically reduced in the bigenic hearts (Fig. 6b). We examined matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2), a proteolytic enzyme that is intimately involved in extracellular remodeling as well as inflammatory responses, and found significantly increased activity in β1-AR Tg hearts compared to WT, but significantly attenuated in the bigenic hearts (Fig. 6c). Moreover, activation of inflammatory transcription factor nuclear factor κB (NFκB), which has been implicated in the transcriptional regulation of several MMPs, was drastically reduced in the bigenic mice compared to β1-AR mice, as reflected by decreased NFκB levels in the nucleus (Fig. 6d).

Fig. 6.

Inhibition of Mst1 decreases pro-inflammatory responses in β1-AR mice. a Representative image of LV sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). b IL-1 expression level was significantly reduced in β1-AR × DN-Mst1 mice compared to β1-AR mice. c MMP-2 activity was significantly increased in β1-AR mice, but reduced in β1-AR × DN-Mst1 mice. d Nuclear NFκB expression level is significantly reduced in β1-AR × DN-Mst1 mice compared to β1-AR Tg mice. **p < 0.01 vs. WT; †p < 0.05 vs. β1-AR; ††p < 0.01 vs. β1-AR (ANOVA)

Discussion

Although this study demonstrated for the first time that inhibition of Mst1 rescued the cardiomyopathy induced by chronic β-AR stimulation, the major finding of this investigation was that inhibition of Mst1 protects against nonmyocyte apoptosis and myocyte necrosis, rather than myocyte apoptosis, suggesting a new mechanistic role for Mst1. As noted above, the β1-adrenergically induced cardiomyopathy was characterized by increased premature mortality, reduced cardiac function and increased myocardial fibrosis. The decrease in LV function with the development of cardiomyopathy was most likely underestimated, since the mice that died early likely had the most severe heart failure. Mating these mice with DN-Mst1 mice prevented the development of β1-AR cardiomyopathy; the bigenic mice showed significant decreases in mortality and cardiac fibrosis and preservation of cardiac function compared to β1-AR mice.

However, in view of Mst1’s important role in mediating apoptosis [4, 11, 12, 25], prior studies concluded that the deleterious or protective effects of Mst1 activation or inhibition was due to its regulation of myocyte apoptosis [5, 6, 27, 31, 45]. Their underlying concept was that inhibition of Mst1 protects apoptosis, which in turn, reduces myocyte loss and consequently maintains the number of contractile units in the heart. This concept is entirely dependent on demonstrating that the apoptosis and its protection occurred in myocytes. Accordingly, we tested this hypothesis. Unlike prior studies on Mst1, we found that the rescue of apoptosis in the bigenic mice predominantly occurred in non-myocytes, while having no significant effects on myocytes. Even though non-myocyte apoptosis is generally unrecognized and has not been reported in prior studies of Mst1 [5, 6, 27, 31, 45], it is of importance, since 75 % of cells in the heart are non-myocytes [17]. We then correlated the myocyte apoptosis with LV function, and with cardiac fibrosis and found no correlation (Fig. 4a, b), suggesting that myocyte apoptosis was not important for the development of the cardiomyopathy or its prevention with DN-Mst1. Since the cardioprotection conferred by Mst1 inhibition is rooted on the concept of preserving myocyte numbers by reducing myocyte apoptosis, we then examined the correlation between myocyte apoptosis and total myocyte numbers. Again, we found no correlation (Fig. 4c). In contrast, we found a strong correlation between non-myocyte apoptosis and fibrosis (Fig. 4d), which can be related to Mst1 regulation of non-myocyte apoptosis, since non-myocytes play an important role in formation of fibrosis [13, 14, 21, 24, 46], which in turn primarily results from necrosis [3, 10]. Therefore, our results differ from all the prior studies concluding that regulation of myocyte apoptosis is the mechanism behind the cardioprotective effects of DN-Mst1 and provide the novel concept that Mst1 regulates myocardial necrosis.

It is well recognized that chronic β-AR stimulation either with isoproterenol [19, 30, 41, 43, 44] or in transgenic models of chronic β-AR stimulation [8, 35], or in almost all models of heart failure of almost any etiology, which are also characterized by increased β-AR stimulation, involves development of cardiac necrosis [15, 19, 30, 41, 43], which in turn leads to myocardial fibrosis [3, 10]; an effect not generally considered an end result from apoptosis. Since we found that development of the β1-AR Tg cardiomyopathy was characterized by significantly increased myocardial fibrosis, that was no longer observed in the bigenic mice as they aged, we surmised that the mechanism of the β1-AR Tg cardiomyopathy involves to a significant extent myocardial necrosis, and that its rescue by the DN-Mst1 involved protection against myocyte necrosis. In vivo labeling with Evans blue dye showed significant necrotic myocyte death in WT mice after 24 h of chronic ISO; whereas DN-Mst1 and Mst1-KO mice showed strong resistance to necrotic injury, while having no effect on myocyte apoptosis. Our conclusion that the protection against necrosis by Mst1 inhibition is also supported by the finding that DN-Mst1 significantly reduced pro-inflammatory processes, which are linked more closely to necrosis than apoptosis [7, 10, 20, 22, 29, 38]. This concept coupled with the findings of non-myocyte apoptosis in cells that are known to be involved in inflammation, e.g., fibroblasts, macrophages, neutrophils, and endothelial cells [33, 34, 36, 40], support the conclusion that Mst1 mediates necrosis. A characteristic feature of necrosis is the release of several factors, which not only attract macrophages but also initiate the release of proinflammatory cytokines [2, 38, 42]. Increases in proinflammatory cytokines were demonstrated in this study by the elevated expression level of cytokine IL-1 as well as increases in MMP-2 and NFκB activity in β1-AR Tg hearts and their significant decrease in bigenic hearts. This may be one mechanism by which Mst1 inhibition in cardiomyocytes mediates the reduction of non-myocyte apoptosis, i.e., crosstalk between cardiomyocytes and nonmyocytes. It has been shown that serum of patients with congestive heart failure induces endothelial cell apoptosis in vitro [1, 37] and the pro-apoptotic activity was due to pro-inflammatory cytokines released from cardiomyocytes during stress [26, 37]. In the present study, we found significant elevation of pro-inflammatory cytokine, IL-1, in β1-AR cardiomyopathy, but a decrease in IL-1 levels as well as reduced non-myocyte apoptosis in animals with cardiac-specific inhibition of Mst1, supporting this crosstalk mechanism.

Therefore, although Mst1 does regulate apoptosis in the heart, it predominantly regulates non-myocyte apoptosis, rather than myocyte apoptosis. The major finding of the present study is that inhibiting Mst1 rescued β1-AR cardiomyopathy not through protection of myocyte apoptosis, as would have been predicted from the literature, but rather by reducing myocyte necrosis and non-myocyte apoptosis. These data indicate that Mst1 has a novel role in mediating cellular death in the heart, not previously recognized.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Stefan Engelhardt for the generous gift of β1-AR Tg mice. We also thank Dr. Joseph Avruch for the kind gift of Mst1-KO mice.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest There are no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Grace J. Lee, Department of Cell Biology and Molecular Medicine, Cardiovascular Research Institute, New Jersey Medical School, Rutgers University, 185 South Orange Avenue, MSB G609, Newark, NJ 07103, USA

Lin Yan, Department of Cell Biology and Molecular Medicine, Cardiovascular Research Institute, New Jersey Medical School, Rutgers University, 185 South Orange Avenue, MSB G609, Newark, NJ 07103, USA.

Dorothy E. Vatner, Department of Medicine, New Jersey Medical School, Rutgers University, Newark, NJ 07103, USA

Stephen F. Vatner, Email: vatnersf@njms.rutgers.edu, Department of Cell Biology and Molecular Medicine, Cardiovascular Research Institute, New Jersey Medical School, Rutgers University, 185 South Orange Avenue, MSB G609, Newark, NJ 07103, USA.

References

- 1.Agnoletti L, Curello S, Bachetti T, Malacarne F, Gaia G, Comini L, Volterrani M, Bonetti P, Parrinello G, Cadei M, Grigolato PG, Ferrari R. Serum from patients with severe heart failure downregulates eNOS and is proapoptotic: role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Circulation. 1999;100:1983–1991. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.19.1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrassy M, Volz HC, Igwe JC, Funke B, Eichberger SN, Kaya Z, Buss S, Autschbach F, Pleger ST, Lukic IK, Bea F, Hardt SE, Humpert PM, Bianchi ME, Mairbaurl H, Nawroth PP, Remppis A, Katus HA, Bierhaus A. High-mobility group box-1 in ischemia-reperfusion injury of the heart. Circulation. 2008;117:3216–3226. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.769331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benjamin IJ, Jalil JE, Tan LB, Cho K, Weber KT, Clark WA. Isoproterenol-induced myocardial fibrosis in relation to myocyte necrosis. Circ Res. 1989;65:657–670. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.3.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Souza PM, Lindsay MA. Mammalian Sterile20-like kinase 1 and the regulation of apoptosis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:485–488. doi: 10.1042/BST0320485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Del Re DP, Matsuda T, Zhai P, Gao S, Clark GJ, Van Der Weyden L, Sadoshima J. Proapoptotic Rassf1A/Mst1 signaling in cardiac fibroblasts is protective against pressure overload in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3555–3567. doi: 10.1172/JCI43569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Del Re DP, Matsuda T, Zhai P, Maejima Y, Jain MR, Liu T, Li H, Hsu CP, Sadoshima J. Mst1 promotes cardiac myocyte apoptosis through phosphorylation and inhibition of Bcl-xL. Mol Cell. 2014;54:639–650. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorn GW., 2nd Molecular mechanisms that differentiate apoptosis from programmed necrosis. Toxicol Pathol. 2013;41:227–234. doi: 10.1177/0192623312466961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engelhardt S, Hein L, Wiesmann F, Lohse MJ. Progressive hypertrophy and heart failure in beta1-adrenergic receptor transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7059–7064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.7059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frangogiannis NG. Regulation of the inflammatory response in cardiac repair. Circ Res. 2012;110:159–173. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gandhi MS, Kamalov G, Shahbaz AU, Bhattacharya SK, Ahokas RA, Sun Y, Gerling IC, Weber KT. Cellular and molecular pathways to myocardial necrosis and replacement fibrosis. Heart Fail Rev. 2011;16:23–34. doi: 10.1007/s10741-010-9169-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graves JD, Gotoh Y, Draves KE, Ambrose D, Han DK, Wright M, Chernoff J, Clark EA, Krebs EG. Caspase-mediated activation and induction of apoptosis by the mammalian Ste20-like kinase Mst1. EMBO J. 1998;17:2224–2234. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harvey KF, Pfleger CM, Hariharan IK. The Drosophila Mst ortholog, hippo, restricts growth and cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis. Cell. 2003;114:457–467. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00557-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayashidani S, Tsutsui H, Shiomi T, Ikeuchi M, Matsusaka H, Suematsu N, Wen J, Egashira K, Takeshita A. Antimonocyte chemoattractant protein-1 gene therapy attenuates left ventricular remodeling and failure after experimental myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2003;108:2134–2140. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000092890.29552.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hinglais N, Heudes D, Nicoletti A, Mandet C, Laurent M, Bariety J, Michel JB. Colocalization of myocardial fibrosis and inflammatory cells in rats. Lab Invest. 1994;70:286–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iwase M, Bishop SP, Uechi M, Vatner DE, Shannon RP, Kudej RK, Wight DC, Wagner TE, Ishikawa Y, Homcy CJ, Vatner SF. Adverse effects of chronic endogenous sympathetic drive induced by cardiac GS alpha overexpression. Circ Res. 1996;78:517–524. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.4.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iwatsubo K, Bravo C, Uechi M, Baljinnyam E, Nakamura T, Umemura M, Lai L, Gao S, Yan L, Zhao X, Park M, Qiu H, Okumura S, Iwatsubo M, Vatner DE, Vatner SF, Ishikawa Y. Prevention of heart failure in mice by an antiviral agent that inhibits type 5 cardiac adenylyl cyclase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H2622–H2628. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00190.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jugdutt BI. Ventricular remodeling after infarction and the extracellular collagen matrix: when is enough enough? Circulation. 2003;108:1395–1403. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000085658.98621.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawaguchi M, Takahashi M, Hata T, Kashima Y, Usui F, Morimoto H, Izawa A, Takahashi Y, Masumoto J, Koyama J, Hongo M, Noda T, Nakayama J, Sagara J, Taniguchi S, Ikeda U. Inflammasome activation of cardiac fibroblasts is essential for myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation. 2011;123:594–604. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.982777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knufman NM, van der Laarse A, Vliegen HW, Brinkman CJ. Quantification of myocardial necrosis and cardiac hypertrophy in isoproterenol-treated rats. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol. 1987;57:15–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kono H, Rock KL. How dying cells alert the immune system to danger. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:279–289. doi: 10.1038/nri2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koyanagi M, Egashira K, Kitamoto S, Ni W, Shimokawa H, Takeya M, Yoshimura T, Takeshita A. Role of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in cardiovascular remodeling induced by chronic blockade of nitric oxide synthesis. Circulation. 2000;102:2243–2248. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.18.2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kung G, Konstantinidis K, Kitsis RN. Programmed necrosis, not apoptosis, in the heart. Circ Res. 2011;108:1017–1036. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.225730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lai L, Yan L, Gao S, Hu CL, Ge H, Davidow A, Park M, Bravo C, Iwatsubo K, Ishikawa Y, Auwerx J, Sinclair DA, Vatner SF, Vatner DE. Type 5 adenylyl cyclase increases oxidative stress by transcriptional regulation of manganese superoxide dismutase via the SIRT1/FoxO3a pathway. Circulation. 2013;127:1692–1701. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.001212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laplante P, Sirois I, Raymond MA, Kokta V, Beliveau A, Prat A, Pshezhetsky AV, Hebert MJ. Caspase-3-mediated secretion of connective tissue growth factor by apoptotic endothelial cells promotes fibrosis. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:291–303. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee KK, Ohyama T, Yajima N, Tsubuki S, Yonehara S. MST, a physiological caspase substrate, highly sensitizes apoptosis both upstream and downstream of caspase activation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:19276–19285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005109200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maass DL, Hybki DP, White J, Horton JW. The time course of cardiac NF-kappaB activation and TNF-alpha secretion by cardiac myocytes after burn injury: contribution to burn-related cardiac contractile dysfunction. Shock. 2002;17:293–299. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200204000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maejima Y, Kyoi S, Zhai P, Liu T, Li H, Ivessa A, Sciarretta S, Del Re DP, Zablocki DK, Hsu CP, Lim DS, Isobe M, Sadoshima J. Mst1 inhibits autophagy by promoting the interaction between Beclin1 and Bcl-2. Nat Med. 2013;19:1478–1488. doi: 10.1038/nm.3322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller DL, Li P, Dou C, Armstrong WF, Gordon D. Evans blue staining of cardiomyocytes induced by myocardial contrast echocardiography in rats: evidence for necrosis instead of apoptosis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2007;33:1988–1996. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munoz LE, Peter C, Herrmann M, Wesselborg S, Lauber K. Scent of dying cells: the role of attraction signals in the clearance of apoptotic cells and its immunological consequences. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:425–430. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakayama H, Chen X, Baines CP, Klevitsky R, Zhang X, Zhang H, Jaleel N, Chua BH, Hewett TE, Robbins J, Houser SR, Molkentin JD. Ca2+- and mitochondrial-dependent cardiomyocyte necrosis as a primary mediator of heart failure. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2431–2444. doi: 10.1172/JCI31060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Odashima M, Usui S, Takagi H, Hong C, Liu J, Yokota M, Sadoshima J. Inhibition of endogenous Mst1 prevents apoptosis and cardiac dysfunction without affecting cardiac hypertrophy after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2007;100:1344–1352. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000265846.23485.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olivetti G, Ricci R, Anversa P. Hyperplasia of myocyte nuclei in long-term cardiac hypertrophy in rats. J Clin Invest. 1987;80:1818–1821. doi: 10.1172/JCI113278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park M, Shen YT, Gaussin V, Heyndrickx GR, Bartunek J, Resuello RR, Natividad FF, Kitsis RN, Vatner DE, Vatner SF. Apoptosis predominates in nonmyocytes in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H785–H791. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00310.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park M, Vatner SF, Yan L, Gao S, Yoon S, Lee GJ, Xie LH, Kitsis RN, Vatner DE. Novel mechanisms for caspase inhibition protecting cardiac function with chronic pressure overload. Basic Res Cardiol. 2013;108:324. doi: 10.1007/s00395-012-0324-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peter PS, Brady JE, Yan L, Chen W, Engelhardt S, Wang Y, Sadoshima J, Vatner SF, Vatner DE. Inhibition of p38 alpha MAPK rescues cardiomyopathy induced by overexpressed beta 2-adrenergic receptor, but not beta 1-adrenergic receptor. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1335–1343. doi: 10.1172/JCI29576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rafatian N, Westcott KV, White RA, Leenen FH. Cardiac macrophages and apoptosis after myocardial infarction: effects of central MR blockade. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2014;307:R879–R887. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00075.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rossig L, Haendeler J, Mallat Z, Hugel B, Freyssinet JM, Tedgui A, Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Congestive heart failure induces endothelial cell apoptosis: protective role of carvedilol. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:2081–2089. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scaffidi P, Misteli T, Bianchi ME. Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature. 2002;418:191–195. doi: 10.1038/nature00858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shivakumar K, Sollott SJ, Sangeetha M, Sapna S, Ziman B, Wang S, Lakatta EG. Paracrine effects of hypoxic fibroblast-derived factors on the MPT-ROS threshold and viability of adult rat cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H2653–H2658. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.91443.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takemura G, Ohno M, Hayakawa Y, Misao J, Kanoh M, Ohno A, Uno Y, Minatoguchi S, Fujiwara T, Fujiwara H. Role of apoptosis in the disappearance of infiltrated and proliferated interstitial cells after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 1998;82:1130–1138. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.11.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teerlink JR, Pfeffer JM, Pfeffer MA. Progressive ventricular remodeling in response to diffuse isoproterenol-induced myocardial necrosis in rats. Circ Res. 1994;75:105–113. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tian J, Avalos AM, Mao SY, Chen B, Senthil K, Wu H, Parroche P, Drabic S, Golenbock D, Sirois C, Hua J, An LL, Audoly L, La Rosa G, Bierhaus A, Naworth P, Marshak-Rothstein A, Crow MK, Fitzgerald KA, Latz E, Kiener PA, Coyle AJ. Toll-like receptor 9-dependent activation by DNA-containing immune complexes is mediated by HMGB1 and RAGE. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:487–496. doi: 10.1038/ni1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Todd GL, Cullan GE, Cullan GM. Isoproterenol-induced myocardial necrosis and membrane permeability alterations in the isolated perfused rabbit heart. Exp Mol Pathol. 1980;33:43–54. doi: 10.1016/0014-4800(80)90006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang W, Zhang H, Gao H, Kubo H, Berretta RM, Chen X, Houser SR. β1-Adrenergic receptor activation induces mouse cardiac myocyte death through both L-type calcium channel-dependent and -independent pathways. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299:H322–H331. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00392.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamamoto S, Yang G, Zablocki D, Liu J, Hong C, Kim SJ, Soler S, Odashima M, Thaisz J, Yehia G, Molina CA, Yatani A, Vatner DE, Vatner SF, Sadoshima J. Activation of Mst1 causes dilated cardiomyopathy by stimulating apoptosis without compensatory ventricular myocyte hypertrophy. J Clin Investig. 2003;111:1463–1474. doi: 10.1172/JCI17459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang F, Yang XP, Liu YH, Xu J, Cingolani O, Rhaleb NE, Carretero OA. Ac-SDKP reverses inflammation and fibrosis in rats with heart failure after myocardial infarction. Hypertension. 2004;43:229–236. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107777.91185.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou D, Conrad C, Xia F, Park JS, Payer B, Yin Y, Lauwers GY, Thasler W, Lee JT, Avruch J, Bardeesy N. Mst1 and Mst2 maintain hepatocyte quiescence and suppress hepatocellular carcinoma development through inactivation of the Yap1 oncogene. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:425–438. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]