Abstract

Enriching iron (Fe) and zinc (Zn) content in rice grains, while minimizing cadmium (Cd) levels, is important for human health and nutrition. Natural genetic variation in rice grain Zn enables Zn-biofortification through conventional breeding, but limited natural Fe variation has led to a need for genetic modification approaches, including over-expressing genes responsible for Fe storage, chelators, and transporters. Generally, Cd uptake and allocation is associated with divalent metal cations (including Fe and Zn) transporters, but the details of this process are still unknown in rice. In addition to genetic variation, metal uptake is sometimes limited by its bioavailability in the soil. The availability of Fe, Zn, and Cd for plant uptake varies widely depending on soil redox potential. The typical practice of flooding rice increases Fe while decreasing Zn and Cd availability. On the other hand, moderate soil drying improves Zn uptake but also increases Cd and decreases Fe uptake. Use of Zn- or Fe-containing fertilizers complements breeding efforts by providing sufficient metals for plant uptake. In addition, the timing of nitrogen fertilization has also been shown to affect metal accumulation in grains. The purpose of this mini-review is to identify knowledge gaps and prioritize strategies for improving the nutritional value and safety of rice.

Keywords: rice, Cd contamination, genetic biofortification, risk mitigation, Zn enriched rice, Fe enriched rice, agronomic biofortification

INTRODUCTION

Iron (Fe) and zinc (Zn) deficiencies affect more than two billion people globally (McLean et al., 2009; Wessells and Brown, 2012). Fe-deficiency anemia can cause impaired cognitive and physical development in children and reduction of daily productivity in adults (Black et al., 2013; Stevens et al., 2013). Recently, low maternal Fe intake has been linked to autism spectrum disorder in their offspring (Schmidt et al., 2014). Adequate Zn nutrition is also important for child growth, immune function, and neurobehavioral development (Wessells and Brown, 2012). Biofortification, defined as increasing the micronutrient content in staple food (Bouis et al., 2011), has the potential to combat Fe and Zn deficiencies, but it is important to ensure low presence of undesirable toxic metals. Because cadmium (Cd) tends to accumulate in kidneys throughout a person’s life, there is concern that regular consumption of rice with even moderate Cd concentration may result in health problems, especially for people who consume rice as a staple food (Meharg et al., 2013). Here we review the genetics and nutrient management approaches to increasing Fe and Zn and minimizing possible Cd contamination.

CONVENTIONAL, MARKER ASSISTED AND TRANSGENIC BREEDING APPROACHES FOR BIOFORTIFICATION TO ENHANCE Fe AND Zn CONCENTRATIONS IN RICE

Nutritional studies suggested that 24–28 mg kg-1 Zn and 13 mg kg-1 Fe concentration in polished grain is essential to reach the 30% of human estimated average requirement (Bouis et al., 2011). Based on this, rice germplasm diversity has been exploited to breed Zn-dense varieties conventionally (Graham et al., 1999). Two Zn-enriched varieties, reaching up to 19 and 24 mg kg-1 Zn in rice grains, have been released by Bangladesh Rice Research Institute (BRRI) in collaboration with the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) under the HarvestPlus project. Identification of quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for low to moderate Zn enhancement in the existing rice germplasm were reported (Stangoulis et al., 2006; Anuradha et al., 2012; Neelamraju et al., 2012). In addition, genome wide association mapping revealed several loci associated with Zn levels in grains (Norton et al., 2014). However, large effect Zn QTLs (≥30% phenotypic variation) have not been identified yet. Conventional breeding efforts for developing Fe-enriched polished rice have not progressed effectively due to limited variation of Fe concentration in polished rice. Evaluation of more than 20,000 rice accessions from Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean for Fe and Zn concentration revealed a maximum of only 8 mg kg-1 in polished grains (Gregorio et al., 2000; Graham, 2003; Martínez et al., 2010). Most Fe and Zn are concentrated in the aleurone layers of rice bran. There are between 1 and 5 aleurone layers in different rice accessions (del Rosario et al., 1968); therefore, the high Fe levels in unpolished grains can be due to thickness of the bran layers. Conventional breeding has so far been unsuccessful in the development of Fe-enriched polished rice (Bashir et al., 2013a).

Transgenic approaches to enhance Fe in the starchy endosperm were first explored more than a decade ago (Goto et al., 1999). Since then, researchers have attempted to increase Fe content in rice endosperm by overexpressing genes involved in Fe uptake from the soil and translocation from roots, shoot, flag leaf to grains, and by increasing the efficiency of Fe storage proteins (Table 1; Kobayashi and Nishizawa, 2012; Lee et al., 2012; Bashir et al., 2013a; Masuda et al., 2013a). Among these studies, the concomitant increase in Fe and Zn content in rice grains was obtained by the overexpression or activation of the NAS (nicotianamine synthase) genes, either in solo or in combination with other transporters or Fe storage genes (Table 1). NAS catalyzes the synthesis of the divalent metal chelator nicotianamine acid (NA) from the precursor molecule 2’-deoxymugeneic acid (MA). Constitutive expression of OsNAS2 resulted in increased Fe concentration as high as 19 mg kg-1and Zn concentration to as high as 76 mg kg-1 within the endosperm of polished rice grains (Johnson et al., 2011). On the other hand, the baseline of O. japonica cv. Nipponbare in this study is 4 mg kg-1 Fe, which is higher than other studies employing japonica accessions (Table 1), possibly due to a favorable micro-environment. Combinations of genes involved in chelating, transporting or storing Fe significantly enhanced Fe concentration to reach polished grain concentration as high as 8–9 mg kg-1 (Masuda et al., 2012, 2013b; Aung et al., 2013). These studies also demonstrated the stability of the trait over multiple plant generations; nevertheless, reaching the recommended target level still remains a challenge. Furthermore, to accelerate the farmers’ adoption and consumers’ acceptance, Oliva et al. (2014) generated phytoferritin over-expressor events in popular indica variety without selectable marker genes; however, the level of Fe was not sufficient to reach the target.

Table 1.

Summary of transgenic approaches to improve Iron (Fe)/Zinc (Zn) concentrations in rice grains and to reduce Cadmium (Cd).

| Gene | Promoter | Cultivar | Growth conditions | Generation of seeds | Fe concentration (ppm) | Fold increase in Fe | Zn concentration (ppm) | Fold increase in Zn | Effect on Cd concentration in the grains | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) Overexpression approaches | ||||||||||

| (1) Brown seeds | ||||||||||

| SoyferH1 | OsGluBI | Japonica cv. Kitaake | Greenhouse | T1 | ∼38.0 | 3.0 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | Goto et al. (1999) |

| SoyFerH1 | OsGlu ; OsGtbl | Japonica cv. Kiktake | Sreenhouse | T3 to T6 | up to 27.0 | 3.0 | up to 46.0 | 1.1 | Similar to WT | Qu et al. (2005) |

| PyFerritin+rgMT | OsGluBl | Japonica cv. Taipei 309 | Greenhouse | T1 | ∼22.0 | 2.0 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | Lucca et al. (2002) |

| TOM1 | CaMV 35S | Japonica cv. Tsukinohikari | Hydroponic | T1 | ∼18.0 | 1.2 | ∼45.0 | 1.6 | n.a. | Nozoye et al. (2011) |

| SoyferH1 | ZmUbil | Indica cv. M12 | Greenhouse | T2 homozygous | ∼18.0 | No significant increase | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | Drakakaki et al. (2000) |

| OsIRO2 | CaMV 35S | Japonica cv. Tsukinohikari | Greenhouse | T1 | up to 15.5 | 2.8 | up to 13.0 | 1.4 | Ogo et al. (2011) | |

| (Calcareous soil) | ||||||||||

| OsYSL15 | OsAcinl | Japonica cv. Dongjin | Paddy field | T1 | ∼14.0 | 1.1 | ∼23.5 | 1.0 | n.a. | Lee et al. (2009a) |

| OsIRT1 | ZmUbil | Japonica cv. Dongjin | Paddy field | T3 homozygous | ∼12.0 | 1.1 | ∼22 | 1.1 | Similar to WT (roots and shoots) | Lee and An (2009) |

| HvNAS1, HvNAS1+HvNAAT, IDS3 | Genomic fragments | Japonica cv. Tsukinohikari | Paddy field (Calcareous soil) | T1 | up to 7.3 | 1.2 | up to 15.3 | 1.4 | n.a. | Suzuki et al. (2008) |

| OsNAS1 | OsGluBl | Japonica cv. Xiushui 110 | field | ?? | ∼5.0 | 1.0 | ∼30.0 | 1.3 | n.a. | Zheng et al. (2010) |

| (2) Milled seeds | ||||||||||

| SoyFerH1 | OsGluBl | Indica cv. IR68144 | Screenhouse | T2 | 3.7 | ∼55.0 | 1.4 | n.a. | Vasconcelos et al. (2003) | |

| SoyFerH1 | Indica cv. Swama | Greenhouse | BC2F5 | up to 16.0 | 2.5 | up to 27.5 | 1.5 | n.a. | Paul et al. (2014) | |

| OsFer2 | OsGluA2 | Basmati rice (Indica cv. Pusa-Sugandh II) | Greenhouse | T3 | up to 15.9 | 2.1 | up to 30.75 | 1.4 | n.a. | Paul et al. (2012) |

| OsNAS3 | Activation tagging | Japonica cv. Dongjin | Greenhouse | T1 | ∼12.0 | 2.6 | ∼35.0 | 2.2 | Similar to WT | Lee et al. (2009b) |

| OsNAS2 | Activation tagging | Japonica cv. Dongjin | Greenhouse | ?? | ∼10.0 | 3.0 | ∼42.0 | 2.7 | Similar to WT | Lee et al. (2011, 2012) |

| (3) Polished seeds | ||||||||||

| OsNAS1, OsNAS2, OsNAS3 | CaMV 35S | Japonica cv. Nipponbare | Glasshouse | T1 | up to 19.0 | 2.2, 4.2, 2.2 | up to 76.0 | 1.4, 2.2, 1,4 | n.a. | Johnson et al. (2011) |

| SoyFerH1 | GluB1 | Indica cv. BR29 | Greenhouse | T3 | up to 9.2 | 2.4 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | Khalekuzzaman et al. (2006) |

| HvNAS1 | CaMV 35S | Japonica cv. Tsukinohikari | Greenhouse | T2 | ∼8.5 | 2.5 | ∼28.0 | 1.5 | n.a. | Higuchi et al. (2001), Masuda et al. (2009) |

| SoyFerH1, SoyFerH2, OsFer1C, OsFer2C | CluBI and GluB4, CluB1 and GluB4, CluB1 and GluB4, CluB1 and GluB4 | Indica cv. 1R64 | Greenhouse | T4 | up to 7.6 | 2.3 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | Oliva et al. (2014) |

| SoyFerH1, SoyFerH2 | CluB1 and GluB4, CluB1 | Indica cv. IR64 | Greenhouse | T5 | up to 5.9 | 1.8 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | |

| HvNAS1 | OsActinl | Japonica cv. Tsukinohikari | Greenhouse | T1 | ∼7.5 | 3.4 | ∼35.0 | 2.3 | n.a. | Masuda et al. (2009) |

| OsYSL2 | OsSUT1 | Japonica cv. Tsukinohikari | Glasshouse | T1 | ∼7.5 | 4.4 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | Ishimaru et al. (2010) |

| AtNAS1+, Pvferritin+, Afphytase | CaMV 35S, Glbl, Glbl | Japonica cv. Taipei 309 | Hydroponic | T1 | ∼7.0 | 6.3 | ∼33.0 | 1.6 | n.a. | Wirth et al. (2009) |

| OsYSL2+, SoyFerH2+, HvNAS1 | OsSUT1 and Glbl, GluB1 and Glbl, OsActl | Japonica cv. Tsukinohikari | Greenhouse (and paddy field) | T2 (and 73) | up to 7.0 | 6 (and 4) | ∼20.0 | 1.6 | Similar to WT | Masuda et al. (2012) |

| SoyFerH2+, HvNAS1+, OsYSL2 | OsGluBl and OsG1b, OsActinl, OsSUT1 and OsGtbl | Tropical Japonica cv. Paw San Yin (Myanmar high quality rice) | Greenhouse | T1 (and T2) | 6.3 (up to 5.02) | 2 (up to 3.4) | 34.2 (up to 39.2) | 1.1 (up to 1.3) | .1, | Aung et al. (2013) |

| SoyFerH2, HvNAS1, HvNAAT-A, -B and IDS3 genome fragments | OsGluBl, OsGtbl | Japonica cv. Tsukinohikari | Greenhouse Greenhouse (calcareous soil) | T3 T3 | up to 4.0 up to 5.0 | 2.6 2.5 | up to 31 up to 25.0 | 1.5 1.4 | n.a. n.a. | Masuda et al. (2013b) |

| HyNAS1, HyNAS1+HyNAAT, IDS3 | Genomic fragments | Japonica cv. Tsukinohikari | Paddy field (Andosolsoi) | T1 | 1.11, 1.19, 1.49 | 1.0, 1.1, 1.4 | 11.3, 11.9, 14.3 | 1.0, 1.1, 1.3 | n.a. | Masuda et al. (2008) |

| (B) Silencing approaches | ||||||||||

| OsVIT | T-DNA mutant | Japonica cv. Zhonghual 1 | Paddy field | ∼16 | ∼1.4 | ∼31 | ∼1.2 | ↑ | Zhang et al. (2012) | |

| (0.55 ppm Cd) | ||||||||||

| OsVIT2 | T-DNA mutant | Japonica cv. Dongjin | Paddy field (0.55 ppm Cd) | ∼14 | ∼1.5 | ∼30 | ∼1.3 | ↑ | Zhang et al. (2012) | |

| OsNRAMP5 | RNAi | Japonica cv. Tsukinohikari | glasshouse (10μM Cd) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | ↓ | Ishimaru et al. (2012)∗ |

*Silencing of OsNRAMP5 (Natural Resistance-Associated Macrophage Protein 5) has also been obtained through ion-beam irradiation (Ishikawa et al., 2012). Different approaches have been grouped based the transgenic over expression vs. down regulation (silencing) approaches, and available Fe/Zn data (polished grain or brown rice). The arrows (↑) or (↓) indicate the increase/decrease of Cd concentration in rice grains.

The average of 2 mg kg-1 Fe in well-polished rice g rains is the general baseline in popular varieties (Bouis et al., 2011). However, there was a marked variation in the baseline of Fe concentration between genotypes used in the studies described in Table 1. Such variation could be due to differences in the milling degree of rice grains, the respective genotypes as such, or the growth conditions, and fertilizer applications. In addition, Fe measurement is also highly prone to contamination during seed processing, milling, and analytical process.

Most Fe biofortification studies were conducted under favorable glasshouse conditions, with only limited studies performed under field conditions (Masuda et al., 2008, 2012). In the first study, moderate increases of 1.40-fold for Fe and 1.35-fold for Zn concentrations of transgenic polished rice grains were observed compared to the control (Masuda et al., 2008). In the second study, a significant decrease (up to 50%) was observed in the Fe concentration in polished grains in the subsequent generation of T3 homozygous plants grown under paddy field conditions (4 mg kg-1) compared to the earlier generation grown under the glasshouse condition (Masuda et al., 2012) that reached up to 7–8 mg kg-1 (six times the concentration of the wild type control).

Among genetic improvement options for increasing rice grain Fe and Zn, we recommend the prioritization of the sink and source strategy (Wirth et al., 2009; Masuda et al., 2013a). However, despite the fast progress, reaching the nutritionist recommended target level of 13 mg kg-1 for Fe under field conditions (Bouis et al., 2011) still remains a challenge (Bashir et al., 2013a). Therefore, to enhance Fe and Zn content in polished rice grains, the expression of most optimum orthologoues of chelator(s), transporter genes and iron storage genes still needs to be evaluated. In addition, for product development, data on the transgene copy number is required.

GENETICS OF CADMIUM UPTAKE

In general, indica varieties accumulated higher Cd concentrations compared to japonica in Cd-polluted soils or in hydroponic solution with high Cd (Arao and Ishikawa, 2006). The physiological mechanisms for Cd uptake and its translocation to shoots in rice have been associated with several chemically related metal ions (Kim et al., 2002; Arao and Ishikawa, 2006; Uraguchi and Fujiwara, 2012). Absorption of Cd in hydroponically grown Fe-deficient plants was thought to be mediated through the Fe-uptake system, particularly through the OsIRT1 and OsIRT2 genes (Nakanishi et al., 2006). OsNRAMP1 (Natural Resistance-Associated Macrophage Protein 1) is another transporter protein shown to be related to the absorption of Cd in rice roots (Takahashi et al., 2011). Functional analysis of the gene confirmed its expression in roots, whilst the protein was localized in the plasma membrane, indicating its role in Cd absorbance and transport (Takahashi et al., 2011).

Recently, it has been demonstrated that the OsNRAMP5 gene in rice acts as a major transporter of Cd and Mn in the roots (Ishikawa et al., 2012; Sasaki et al., 2012). Expression analysis showed that its presence was restricted to roots, as well as in tissues around the xylem (Ishimaru et al., 2012; Sasaki et al., 2012). In addition, extensive analysis of silencing, insertion knock-out plants, and ion-beam irradiation mutants confirmed the role of OsNRAMP5 in reducing the Cd accumulation both in straw and in grains to negligible levels, even when grown in Cd-contaminated paddy fields (Ishikawa et al., 2012; Ishimaru et al., 2012; Sasaki et al., 2012). Using a different approach, hydroponic and soil culture experiments suggested root-to-shoot Cd translocation via the xylem as the major physiological process for determining grain Cd accumulation in rice (Uraguchi et al., 2009). Analysis of mapping populations for identification of QTLs related to Cd accumulation in rice grains indicated the presence of a genetic locus in chromosome 7 (qGCd7; Ishikawa et al., 2005, 2010). This QTL was shown to be specific to Cd since it was not related to the absorption/translocation of other metal cations or to any agronomic characteristics. Fine mapping of the qGCd7 resulted in the identification of OsHMA3, a gene responsible for limiting the root-to-shoot translocation of Cd by selectively sequestering it within the vacuoles (Ueno et al., 2010; Miyadate et al., 2011). OsHMA2, a close homolog of OsHMA3, has also been shown to be involved in the root-to-shoot translocation of Cd in rice plants, through the xylem network (Satoh-Nagasawa et al., 2012; Takahashi et al., 2012).

Furthermore, Uraguchi et al. (2011) proposed a different route for reducing Cd within the rice grains. The identification of the low-affinity cation transporter (OsLCT1) reduced the Cd accumulation within rice grains by significantly decreasing its phloem-mediated transport. Suppression of OsLCT1 did not have any negative effect on the content of other metal ions in the grains, indicating its specificity for Cd (Uraguchi et al., 2011, 2014). Among genetic strategies for decreasing Cd concentration in rice, we recommend prioritization of strategies reducing the sequestration of Cd in roots, such as down-regulation of OsNRAMP5. This has been achieved recently by RNAi transgenic approach and mutation technologies (Ishikawa et al., 2012; Ishimaru et al., 2012).

HAS CADMIUM BEEN ACCUMULATED IN ENRICHED Fe/Zn RICE?

Conventional breeding lines with enriched grain Zn have not been reported to contain elevated Cd. The fact that Fe/Zn-biofortification by transgenic approaches exploited different transporter genes (Table 1) raises the possibility of Cd accumulation because Zn-associated transporters often co-transport Zn-mimic Cd (Olsen and Palmgren, 2014). The upper limit of Cd set by FAO/WHO in rice grain is 0.4 mg kg-1 (Codex Alimentarius, 2010). The transgenic approaches that tended to simultaneously increase grain Zn as well as Fe were the ones involving the NAS family genes (Table 1). However, assessment of seedlings of OsNAS3 activation tag lines and its wild counterpart in plant growth medium with elevated Cd showed no difference in Cd level amongst different germplasm and tissues (Lee and An, 2009; Lee et al., 2009b, 2011), suggesting the specificity of NA to Zn over Cd (Olsen and Palmgren, 2014). In addition, a 20% reduction in the Cd accumulation was identified in T2 polished grains compared to the non-transgenic counterparts expressing transporters and phytoferritin genes (Aung et al., 2013). Another transporter protein, OsIRT1, has been suggested to be involved in the Fe and Cd uptake pathway earlier (Nakanishi et al., 2006). However, the translocation of excess Cd from the roots to shoots was minimal. Recent studies in osvit1 and osvit2 T-DNA knock out mutants reported some increase in Cd level in rice grains (Zhang et al., 2012). To date only one report on transgenic biofortified rice shows a slight increase in the Cd levels (Zhang et al., 2012), whilst there have been no reports yet on the grain Cd level on the Zn-enriched conventional breeding lines. In all the reported approaches, the acquired Cd concentrations were significantly lower than the threshold toxic levels for the polished rice grains.

MANAGEMENT AND ENVIRONMENT EFFECTS ON Fe, Zn, and Cd UPTAKE IN RICE

The performance of biofortified genotypes is often restricted due to low available pools of Zn or Fe in soil. Under these conditions, enriching Fe or Zn concentration in grains through either fertilization or water management, called agronomic biofortification, is a short term strategy which would complement the breeding programs. Some of these management and environment effects have also been shown to change Cd uptake patterns.

WATER MANAGEMENT

Irrigation management in rice strongly influences soil redox potential, which affects the availability of Fe, Zn, and Cd. Rice was domesticated under flooded conditions, and it is still grown with continuous soil submergence in many places. However, for a variety of reasons, rice is now produced across the entire range of irrigation management options, including fields which are always aerobic, always anaerobic, and many variations along the aerobic-anaerobic spectrum (Bouman et al., 2007). Because socioeconomic drivers are so important in designing irrigation systems, it seems unlikely that farmers would choose irrigation options solely for the purpose of changing the soil availability of Fe, Zn, or Cd. Therefore, we need to understand the effect that water management has on the benefits and risks of enriching grains with metals, even though the opportunities for managing the risks this way are limited.

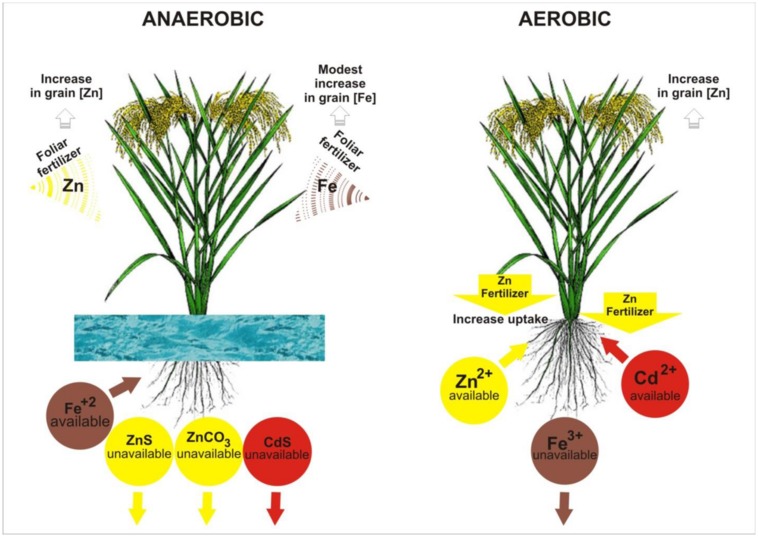

As a soil changes from aerobic to anaerobic conditions after flooding, Fe- oxides are dissolved when the Fe3+ is reduced to Fe2+ (Figure 1), which weakens the oxide stability and increases its water-solubility (Kirk, 2004). This releases much more Fe into the soil solution, so flooded soil nearly always has sufficient Fe for plant uptake, and rice has therefore become somewhat adapted to Fe toxicity. Most rice plants have mechanisms to prevent excessive uptake of Fe. Anti-oxidative mechanisms, including induction of ferritin gene, have been reported as one of the plant mechanisms against excessive plant endogenous Fe2+ (Briat et al., 2010). In contrast, in aerobic soils, Fe deficiency can occur (Zuo and Zhang, 2011), while Zn and Cd both tend to be more available in this soil. Both elements are predominantly present in the +2 oxidation state, regardless of soil redox potential, so the effect of flooding is indirect (rather than direct as with Fe). The availability of Zn decreases with flooding due to precipitation (Figure 1) as insoluble zinc sulphide (after sulfate is reduced to sulphide, Bostick et al., 2001) or as insoluble carbonate mixtures (after decomposing organic matter causes an increase in the partial pressure of carbon dioxide in soil solution, Kirk, 2004). Cadmium behaves similarly to Zn (Du Laing et al., 2009). In summary, changing a soil from aerobic to anaerobic conditions by flooding will increase Fe availability and suppress Cd, but will also decrease Zn availability (Figure 1). The possibility of managing irrigation to optimize the plant uptake of Fe, Zn, and Cd simultaneously is negligible.

FIGURE 1.

Illustration of water and fertilizer managements and their effects on zinc (Zn), iron (Fe), and cadmium (Cd) uptake and accumulation in rice grain. The arrows (↓) under the compounds indicate precipitation.

FERTILIZATION OPTIONS

Most evidence has shown that applying Fe or Zn fertilizers to the soil is ineffective at increasing grain Fe or Zn in rice. Under aerobic water management, the soil-applied Fe (usually in the form of Fe2+, either chelated or as a sulfate salt) is rapidly converted to unavailable Fe3+, and hence, foliar application is a better option to overcome Fe deficiency and to increase grain Fe and its bioavailability in rice (Wei et al., 2012a). Under anaerobic water management, Fe2+ is readily available to rice plants (Figure 1), so no fertilization is needed. Application of Zn at 5–25 kg Zn ha-1 as zinc sulfate incorporated to the soil before flooding or after transplanting is the most common Zn fertilizer recommendation for rice (Dobermann and Fairhurst, 2000). However, soil-applied zinc sulfate has often been unsuccessful in improving grain Zn concentration and yield under flooded paddy due to redox induced fixation of applied Zn (Srivastava et al., 1999; Johnson-Beebout et al., 2009). In rice, positive effects of soil Zn fertilization on grain Zn have been noticed primarily with aerobic water management (Wang et al., 2014). On the other hand, foliar Zn application has been more effective in improving grain Zn concentration in flooded rice compared to soil Zn fertilization (Wissuwa et al., 2008; Wirth et al., 2009). Zn and Fe fertilization strategies and its effects on the uptake and accumulation of Zn, Fe, and Cd in rice are illustrated in Figure 1.

Although foliar application of Fe or Zn is more promising than soil application for enhancing grain Fe or Zn, the efficiency of foliar applied Fe or Zn varies depending on the time of fertilization, source of Zn fertilization and ability of genotypes to remobilize Zn or Fe from source tissues to grain (Karak et al., 2006; Cakmak, 2009; Wei et al., 2012b). Late season foliar application of Zn or Fe at flowering or at early grain filling stage is more effective in improving grain Zn or Fe, respectively, than early season application (Phattarakul et al., 2012; Mabesa et al., 2013). Though the levels of Zn and Fe in grains are positively related, fertilization of one element did not affect the grain concentration of the other (Cakmak et al., 2010; Wei et al., 2012a,b). However, foliar fertilization of combined Fe and Zn fertilizers enhanced both grain-Fe and -Zn content without any antagonistic effects (Wei et al., 2012a). Among fertilization strategies for flooded rice, the most likely to succeed is a combined foliar Zn and Fe spray soon after flowering or at early grain filling stage, and it is important to study how to make foliar fertilizers more effective.

Optimized management of N fertilizer could improve grain Fe and Zn, as indicated by a strong correlation of seed Fe and Zn with N in several crop species under sufficient Zn supply (Zhang et al., 2008; Cakmak et al., 2010; Kutman et al., 2010) Better N nutrition promotes protein synthesis, which is a major sink for Fe and Zn, and enhances the expression Zn and Fe transporter proteins, such as ZIP family transporters (Cakmak et al., 2010). Better N nutrition may also enhance the production of other nitrogenous compounds such as NA and deoxymugineic acid (DMA), and YSL proteins involved in Zn transport within the plant (Haydon and Cobbett, 2007; Curie et al., 2009). Under high N supply, vegetative growth is enhanced and plants remain green for a longer time, resulting in longer grain filling periods, and delayed senescence (Kutman et al., 2010). However, under low Zn conditions, increased biomass production induced by optimal N fertilization can decrease grain Zn concentration due to biological dilution (Zhang et al., 2008; Kutman et al., 2012). In summary, it is always important to optimize N fertilization in rice production, but there is not very much scope for adjusting N management for the purpose of biofortification.

Phosphate fertilizers are major sources of Cd input in agricultural land and in cereal crops (Eriksson, 1990; He and Singh, 1993; Gao et al., 2010). They can contain significant amounts of Cd due to its presence in the rock phosphate used for production (Williams and David, 1973). However, once recognized, these relatively high-Cd phosphate rock sources have been avoided in the production of fertilizer, so there is very little evidence of actual P-fertilizer-related Cd uptake in rice. The effect of Zn fertilization on Cd uptake by plants is highly dependent on the soil Cd and Zn concentrations. Higher biomass accumulation under high NPK fertilization, results in enhanced Cd uptake but may either increase or decrease concentration, depending on the balance of fertilizer effects on crop growth, root distribution, and Cd availability. This could be a useful strategy for phytoremediation but not for cereal production. Increase in Cd uptake under higher rate of fertilization than lower rate of fertilization (Singh, 1990), suggests that efficient management of fertilizers is necessary to keep a control on Cd accumulation in agricultural crops.

IMPROVING IRON AND ZINC NUTRITION, AND MITIGATING CADMIUM TOXICITY RISK THROUGH GENETICS AND MANAGEMENT APPROACHES

Biofortified rice has a potential to reach areas that currently could not be reached by other interventions since rice consumption is high in affected regions. In flooded rice fields, Cd uptake risk is low (Uraguchi and Fujiwara, 2012), but the trend is for more rice fields to become aerobic due to erratic rain or scarce water resources. Therefore, the risk of Cd accumulation will increase with more aerobic water management, particularly in Cd contaminated areas. To mitigate this, it is essential to develop a low Cd accumulating cultivar by down-regulating the expression of endogenous genes involved in Cd uptake and/or translocation by identifying a genetic marker and subsequently introgressing the trait into the popular varieties through marker assisted breeding. The latter approach has been validated in the field using the dysfuntionalOsNRAMP5 mutant (Ishikawa et al., 2012). It significantly decreases root Cd uptake and Cd content in the straw and grain, apparently without decreasing Fe uptake in root, shoot, and straw (Ishimaru et al., 2012; Sasaki et al., 2012). As we continue to identify new pathways to biofortification of rice with Fe and Zn, it is critical to examine the potential for each biofortification mechanism to affect Cd uptake.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge HarvestPlus ("http://www.harvestplus.org/) for financial support. The Indonesian Institute of Sciences is acknowledged for supporting IS-L at International Rice Research Institute.

REFERENCES

- Anuradha K., Agarwal S., Batchu A. K., Babu A. P., Swamy B. P. M., Longvah T., et al. (2012). Evaluating rice germplasm for iron and zinc concentration in brown rice and seed dimensions. J. Phytol. 4 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Arao T., Ishikawa S. (2006). Genotypic differences in cadmium concentration and distribution of soybean and rice. Jpn. Agric. Res. Q. 40 21–30 10.6090/jarq.40.21 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aung M. S., Masuda H., Kobayashi T., Nakanishi H., Yamakawa T., Nishizawa N. K. (2013). Iron biofortification of Myanmar rice. Front. Plant Sci. 4:158 10.3389/fpls.2013.00158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashir K., Takahashi R., Nakanishi H., Nishizawa N. K. (2013a). The road to micronutrient biofortification of rice: progress and prospects. Front. Plant Sci. 4:15 10.3389/fpls.2013.00015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashir K., Takahashi R., Akhtar S., Ishimaru Y., Nakanishi H., Nishizawa N. K. (2013b). The knockdown of OsVIT2 and MIT affects iron localization in rice seed. Rice (N. Y.) 6 31 10.1186/1939-8433-6-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black R. E., Victora C. G., Walker S. P., Bhutta Z. A., Christian P., de Onis M., et al. (2013). Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 382 427–451 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60937-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostick B. C., Hansel C. M., La Force M. J., Fendorf S. (2001). Seasonalfluctuations in zinc speciation within a contaminated wetland. Environ. Sci. Technol. 35 3823–3829 10.1021/es010549d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouis H. E., Hotz C., McClafferty B., Meenakshi J. V., Pfeiffer W. H. (2011). Biofortification: a new tool to reduce micronutrient malnutrition. Food Nutr. Bull. 32 S31–S40 10.1021/es010549d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouman B., Barker R., Humphreys E., Tuong T. P., Atlin G., Bennett J., et al. (2007). “Rice: Feeding the billion,” in Water for Food, Water for Life: a Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture, ed.Molden D. (London: Earthscan and Colombo: International Water Management Institute; ) 515–549. [Google Scholar]

- Briat J. F., Ravet K., Arnaud N., Duc C., Boucherez J., Touraine B., et al. (2010). New insights into ferritin synthesis and function highlight a link between iron homeostasis and oxidative stress in plants. Ann. Bot. 105 811–822 10.1093/aob/mcp128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cakmak I. (2009). Enrichment of fertilizers with zinc: an excellent investment for humanity and crop production in India. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 23 281–289 10.1016/j.jtemb.2009.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cakmak I., Pfeiffer W. H., McClafferty B. (2010). Biofortifcation of durum wheat with zinc and iron. Cereal Chem. 87 10–20 10.1094/CCHEM-87-1-0010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Codex Alimentarius C. (2010). Codex Alimentarius Commision. Codex Stand. 193 44. [Google Scholar]

- Curie C., Cassin G., Couch D., Divol F., Higuchi K., Jean M. L., et al. (2009). Metal movement within plant: contribution of nicotianamine and yellow stripe 1-like transporters. Ann. Bot. 103 1–11 10.1093/aob/mcn207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Rosario A. R., Briones V. P., Vidal A. J., Juliano B. O. (1968). Composition and endosperm structure of developing and mature rice kernel. Cereal Chem. 45 225–235. [Google Scholar]

- Dobermann A., Fairhurst T. H. (2000). Nutrient Disorders and Nutrient Management. Philippines: Potash and Phosphate Institute, Canada and International Rice Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Drakakaki G., Christou P., Stöger E. (2000). Constitutive expression of soybean ferritin cDNA in transgenic wheat and rice results in increased iron levels in vegetative tissues but not in seeds. Transgenic Res. 9 445–452 10.1023/A:1026534009483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Laing G., Rinklebe J., Vandecasteele B., Meers E., Tack F. M. G. (2009). Trace metal behaviour in estuarine and rivering floodplain soils and sediments: a review. Sci. Total Environ. 407 3972–3985 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.07.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson J. E. (1990). Effect of nitrogen-containing fertilizers on solubility and plant uptake of cadmium. Water Air Soil Pollut. 49 355–368 10.1007/BF00507075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y., Wang L., Xin Z., Zhao L., An X., Hu Q. (2008). Effect of foliar application of zinc, selenium, and iron fertilizers on nutrients concentration and yield of rice grain in China. J. Agric. Food Chem. 56 2079–2084 10.1021/jf800150z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X., Brown K. R., Racz G. J., Grant C. A. (2010). Concentration of cadmium in durum wheat as affected by tim, source and placement of nitrogen fertilization under reduced and conventional-tillage mangement. Plant Soil 337 341–354 10.1007/s11104-010-0531-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goto F., Yoshihara T., Shigemoto N., Toki S., Takaiwa F. (1999). Iron fortification of rice seed by the soybean ferritin gene. Nat. Biotechnol. 17 282–286 10.1038/7029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham R. D. (2003). Biofortification: a global challenge. Int. Rice Res. Notes 28 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Graham R., Senadhira D., Beebe S., Iglesias C., Monasterio I. (1999). Breeding for micronutrient density in edible portions of staple food crops: conventional approaches. Fields Crops Res. 60 57–80 10.1016/S0378-4290(98)00133-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gregorio G., Senadhira D., Htut H., Graham R. R. (2000). Breeding for trace mineral density in rice. Food Nutr. Bull. 21 382–386. [Google Scholar]

- Haydon M. J., Cobbett C. S. (2007). Transporters of ligands for essential metal ions in plants. New Phytol. 174 499–506 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02051.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Q. B., Singh B. R. (1993). Plant availablity of cadmium in soils. 1. Extractable cadmium in newly and long term cultivated soils. Acta Agric. Scand. B Soil Plant Sci. 43 134–141. [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi K., Watanabe S., Takahashi M., Kawasaki S., Nakanishi H., Nishizawa N. K., et al. (2001). Nicotianamine synthase gene expression differs in barley and rice under Fe-deficient conditions. Plant J. 25 159–167 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.00951.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa S., Abe T., Kuramata M., Yamaguchi M., Ando T., Yamamoto T., et al. (2010). A major quantitative trait locus for increasing cadmium-specific concentration in rice grain is located on the short arm of chromosome 7. J. Exp. Bot. 61 923–934 10.1093/jxb/erp360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa S., Ae N., Yano M. (2005). Chromosomal regions with quantitative trait loci controlling cadmium concentration in brown rice (Oryza sativa). New Phytol. 168 345–350 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01516.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa S., Ishimaru Y., Igura M., Kuramata M., Abe T., Senoura T., et al. (2012). Ion-beam irradiation, gene identification, and marker-assisted breeding in the development of low-cadmium rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 19166–19171 10.1073/pnas.1211132109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru Y., Masuda H., Bashir K., Inoue H., Tsukamoto T., Takahashi M., et al. (2010). Rice metal-nicotianamine transporter, OsYSL2, is required for the long-distance transport of iron and manganese. Plant J. 62 379–390 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04158.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru Y., Takahashi R., Bashir K., Shimo H., Senoura T., Sugimoto K., et al. (2012). Characterizing the role of rice NRAMP5 in manganese, iron and cadmium transport. Sci. Rep. 2 286 10.1038/srep00286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A. A. T., Kyriacou B., Callahan D. L., Carruthers L., Stangoulis J., Lombi E., et al. (2011). Constitutive overexpression of the OsNAS gene family reveals single-gene strategies for effective iron- and zinc-biofortification of rice endosperm. PLoS ONE 6:e24476 10.1371/journal.pone.0024476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Beebout S. E., Lauren J. G., Duxbury J. M. (2009). Immobilization of zinc fertilizer in flooded soils monitored by adapted DTPA soil test. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 40 1842–1861 10.1080/00103620902896738 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karak T., Das D. K., Maiti D. (2006). Yield and zinc uptake in rice (Oryza sativa) as influenced by sources and times of zinc application. Indian J. Agric. Sci. 76 346–348. [Google Scholar]

- Khalekuzzaman M., Datta K., Olival N., Alam M. F., Joarder I., Datta S. K. (2006). Stable integration, expression and inheritance of the ferritin gene in transgenic elite indica rice cultivar BR29 with enhanced iron level in the endosperm. Indian J. 5 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.-Y., Yang Y.-Y., Lee Y. (2002). Pb and Cd uptake in rice roots. Physiol. Plant. 116 368–372 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2002.1160312.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk G. (2004). The Biogeochemistry of Submerged Soils. Chichester: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T., Nishizawa N. K. (2012). Iron uptake, translocation, and regulation in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 63 131–152 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutman U. B., Yildiz B., Ceylan Y., Ova E. A., Cakmak I. (2012). Contributions of root uptake and remobilization in wheat depending on post-anthesis zinc availability and nitrogen nutrition. Plant Soil 361 1–2 10.1007/s11104-012-1300-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kutman U. B., Yildiz B., Ozturk L., Cakmak I. (2010). Biofortification of durum wheat with zinc through soil and foliar applications of nitrogen. Cereal Chem. 87 1–9 10.1094/CCHEM-87-1-0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., An G. (2009). Over-expression of OsIRT1 leads to increased iron and zinc accumulations in rice. Plant. Cell Environ. 32 408–416 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.01935.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Chiecko J. C., Kim S. A., Walker E. L., Lee Y., Guerinot M. L., An G. (2009a). Disruption of OsYSL15 leads to iron inefficiency in rice plants. Plant Physiol. 150 786–800 10.1104/pp.109.135418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Jeon U. S., Lee S. J., Kim Y.-K., Persson D. P., Husted S., et al. (2009b). Iron fortification of rice seeds through activation of the nicotianamine synthase gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 22014–22019 10.1073/pnas.0910950106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Jeon J.-S., An G. (2012). Iron homeostasis and fortification in rice. J. Plant Biol. 55 261–267 10.1007/s12374-011-0386-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S., Persson D. P., Hansen T. H., Husted S., Schjoerring J. K., Kim Y.-S., et al. (2011). Bio-available zinc in rice seeds is increased by activation tagging of nicotianamine synthase. Plant Biotechnol. J. 9 865–873 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2011.00606.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucca P., Hurrell R., Potrykus I. (2002). Fighting iron deficiency anemia with iron-rich rice. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 21 184–190 10.1080/07315724.2002.10719264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabesa R. L., Impa S. M., Grewal D., Johnson-Beebout S. E. (2013). Contrasting grain-Zn response of biofortification rice (Oryza sativa L.) breeding lines to foliar Zn application. Field Crops Res. 149 223–233 10.1016/j.fcr.2013.05.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez C., Borrero J., Taboada R., Viana J. L., Neves P., Narvaez L., et al. (2010). Rice cultivars with enhanced iron and zinc content to improve human nutrition. Paper Presented at the 28th International Rice Research Conference, Hanoi. [Google Scholar]

- Masuda H., Aung M. S., Nishizawa N. K. (2013a). Iron biofortification of rice using different transgenic approaches. Rice 6 40 10.1186/1939-8433-6-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda H., Kobayashi T., Ishimaru Y., Takahashi M., Aung M. S., Nakanishi H., et al. (2013b). Iron-biofortification in rice by the introduction of three barley genes participated in mugineic acid biosynthesis with soybean ferritin gene. Front. Plant Sci. 4:132 10.3389/fpls.2013.00132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda H., Ishimaru Y., Aung M. S., Kobayashi T., Kakei Y., Takahashi M., et al. (2012). Iron biofortification in rice by the introduction of multiple genes involved in iron nutrition. Sci. Rep. 2 1–7 10.1038/srep00543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda H., Suzuki M., Morikawa K. C., Kobayashi T., Nakanishi H., Takahashi M., et al. (2008). Increase in iron and zinc concentrations in rice grains via the introduction of barley genes involved in phytosiderophore synthesis. Rice 1 100–108 10.1007/s12284-008-9007-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda H., Usuda K., Kobayashi T., Ishimaru Y., Kakei Y., Takahashi M., et al. (2009). Overexpression of the barley nicotianamine synthase gene HvNAS1 increases iron and zinc concentrations in rice grains. Rice 2 155–166 10.1007/s12284-009-9031-9031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLean E., Cogswell M., Egli I., Wojdyla D., de Benoist B. (2009). Worldwide prevalence of anaemia, WHO Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System, 1993-2005. Public Health Nutr. 12 444–454 10.1017/S1368980008002401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meharg A. A., Norton G., Deacon C., Williams P., Adomako E. E., Price A., et al. (2013). Variation in rice cadmium related to human exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47 5613–5618 10.1021/es400521h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyadate H., Adachi S., Hiraizumi A., Tezuka K., Nakazawa N., Kawamoto T., et al. (2011). OsHMA3, a P1B-type of ATPase affects root-to-shoot cadmium translocation in rice by mediating efflux into vacuoles. New Phytol. 189 190–199 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03459.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi H., Ogawa I., Ishimaru Y., Mori S., Nishizawa N. K. (2006). Iron deficiency enhances cadmium uptake and translocation mediated by the Fe2+ transporters OsIRT1 and OsIRT2 in rice. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 52 464–469 10.1111/j.1747-0765.2006.00055.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neelamraju S., MallikarjunaSwamy B. P., Kaladhar K., Anuradha K., VenkateshwarRao Y., Batchu A. K., et al. (2012). Increasing iron and zinc in rice grains using deep water rices and wild species – identifying genomic segments and candidate genes. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crop. Foods 4 138–138 10.1111/j.1757-837X.2012.00142.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norton G. J., Douglas A., Lahner B., Yakubova E., Guerinot M. L., Pinson S. R., et al. (2014). Genome wide association mapping of grain arsenic, copper, molybdenum and zinc in rice (Oryza sativa L.) grown at four international field sites. PLoS ONE 9:e89685. 10.1371/journal.pone.0089685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozoye T., Nagasaka S., Kobayashi T., Takahashi M., Sato Y., Sato Y., et al. (2011). Phytosiderophore efflux transporters are crucial for iron acquisition in graminaceous plants. J. Biol. Chem. 286 5446–5454 10.1074/jbc.M110.180026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogo Y., Itai R. N., Kobayashi T., Aung M. S., Nakanishi H., Nishizawa N. K. (2011). OsIRO2 is responsible for iron utilization in rice and improves growth and yield in calcareous soil. Plant Mol. Biol. 75 593–605 10.1007/s11103-011-9752-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva N., Chadha-Mohanty P., Poletti S., Abrigo E., Atienza G., Torrizo L., et al. (2014). Large-scale production and evaluation of marker-free indica rice IR64 expressing phytoferritin genes. Mol. Breed. 33 23–37 10.1007/s11032-013-9931-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen L. I., Palmgren M. G. (2014). Many rivers to cross: the journey of zinc from soil to seed. Front. Plant Sci. 5:30 10.3389/fpls.2014.00030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul S., Ali N., Datta S. K., Datta K. (2014). Development of an iron-enriched high-yieldings indica rice cultivar by introgression of a high-iron trait from transgenic iron-biofortified rice. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 69 203–208 10.1007/s11130-014-0431-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul S., Ali N., Gayen D., Datta S. K., Datta K. (2012). Molecular breeding of Osfer 2 gene to increase iron nutrition in rice grain. GM Crops Food 3 310–316 10.4161/gmcr.22104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phattarakul N., Rerkasem B., Li L. J., Wu L. H., Zou C. Q., Ram H., et al. (2012). Biofortification of rice grain with zinc through zinc fertilization in different countries. Plant Soil 361 131–141 10.1007/s11104-012-1211-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qu L. Q., Yoshihara T., Ooyama A., Goto F., Takaiwa F. (2005). Iron accumulation does not parallel the high expression level of ferritin in transgenic rice seeds. Planta 222 225–233 10.1007/s00425-005-1530-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki A., Yamaji N., Yokosho K., Ma J. F. (2012). Nramp5 is a major transporter responsible for manganese and cadmium uptake in rice. Plant Cell 24 2155–2167 10.1105/tpc.112.096925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh-Nagasawa N., Mori M., Nakazawa N., Kawamoto T., Nagato Y., Sakurai K., et al. (2012). Mutations in rice (Oryza sativa) heavy metal ATPase 2 (OsHMA2) restrict the translocation of zinc and cadmium. Plant Cell Physiol. 53 213–224 10.1093/pcp/pcr166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt R. J., Tancredi D. J., Krakowiak P., Hansen R. L., Ozonoff S. (2014). Maternal intake of supplemental iron and risk of autism spectrum disorder. Am. J. Epidemiol. 180 890–900 10.1093/aje/kwu208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh B. R. (1990). Uptake of cadmium and fluoride by oat from phosphate fertilizers. Norw J. Agric. Sci. 4 239–249. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava P. C., Ghosh D., Sing V. P. (1999). Evaluation of different zinc sources for lowland rice production. Biol. Fert. Soil 30 168–172 10.1007/s003740050604 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stangoulis J. C. R., Huynh B.-L., Welch R. M., Choi E.-Y., Graham R. D. (2006). Quantitative trait loci for phytate in rice grain and their relationship with grain micronutrient content. Euphytica 154 289–294 10.1007/s10681-006-9211-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens G. A., Finucane M. M., De-Regil L. M., Paciorek C. J., Flaxman S. R., Branca F., et al. (2013). Global, regional, and national trends in haemoglobin concentration and prevalence of total and severe anaemia in children and pregnant and non-pregnant women for 1995–2011: a systematic analysis of population-representative data. Lancet Glob. Health 1 e16–e25 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70001-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M., Morikawa K. C., Nakanishi H., Takahashi M., Saigusa M., Mori S., et al. (2008). Transgenic rice lines that include barley genes have increased tolerance to low iron availability in a calcareous paddy soil. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 54 77–85 10.1111/j.1747-0765.2007.00205.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi R., Ishimaru Y., Senoura T., Shimo H., Ishikawa S., Arao T., et al. (2011). The OsNRAMP1 iron transporter is involved in Cd accumulation in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 62 4843–4850 10.1093/jxb/err136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi R., Ishimaru Y., Shimo H., Ogo Y., Senoura T., Nishizawa N. K., et al. (2012). The OsHMA2 transporter is involved in root-to-shoot translocation of Zn and Cd in rice. Plant Cell Environ. 35 1948–1957 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02527.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno D., Yamaji N., Kono I., Huang C. F., Ando T., Yano M., et al. (2010). Gene limiting cadmium accumulation in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 16500–16505 10.1073/pnas.1005396107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uraguchi S., Fujiwara T. (2012). Cadmium transport and tolerance in rice: perspectives for reducing grain cadmium accumulation. Rice 5 5 10.1186/1939-8433-5-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uraguchi S., Kamiya T., Clemens S., Fujiwara T. (2014). Characterization of OsLCT1, a cadmium transporter from indica rice (Oryza sativa). Physiol. Plant. 151 339–347 10.1111/ppl.12189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uraguchi S., Kamiya T., Sakamoto T., Kasai K., Sato Y., Nagamura Y., et al. (2011). Low-affinity cation transporter (OsLCT1) regulates cadmium transport into rice grains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 20959–20964 10.1073/pnas.1116531109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uraguchi S., Mori S., Kuramata M., Kawasaki A., Arao T., Ishikawa S. (2009). Root-to-shoot Cd translocation via the xylem is the major process determining shoot and grain cadmium accumulation in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 60 2677–2688 10.1093/jxb/erp119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos M., Datta K., Oliva N., Khalekuzzaman M., Torrizo L., Krishnan S., et al. (2003). Enhanced iron and zinc accumulation in transgenic rice with the ferritin gene. Plant Sci. 164 371–378 10.1016/S0168-9452(02)00421-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Wei Y., Dong L., Lu L., Feng Y., Zhang J., et al. (2014). Improved yield and Zn accumulation for rice grain by Zn fertilization and optimized water management. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 15 365–374 10.1631/jzus.B1300263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y., Shohag M. J. I., Yang X., Yibin Z. (2012a). Effects of foliar iron application on iron concentration in polished rice grain and its bioavailability. J. Agric. Food Chem. 60 11433–11439 10.1021/jf3036462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y., Shohag M. J. I., Yang X. (2012b). Biofortification and bioavailability of rice grain zinc as affected by different forms of foliar Zinc fertilization. PLoS ONE 7:e45428 10.137/journal.pone.0045428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessells K. R., Brown K. H. (2012). Estimating the global prevalence of zinc deficiency: results based on zinc availability in national food supplies and the prevalence of stunting. PLoS ONE 7:e50568 10.1371/journal.pone.0050568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams C. H., David D. J. (1973). The effect of superphosphate on the Cd content of soils and plants. Aust. J. Soil Res. 11 43–56 10.1071/SR9730043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wirth J., Poletti S., Aeschlimann B., Yakandawala N., Drosse B., Osorio S., et al. (2009). Rice endosperm iron biofortification by targeted and synergistic action of nicotianamine synthase and ferritin. Plant Biotechnol. J. 7 631–644 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2009.00430.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wissuwa M., Ismail A. M., Graham R. D. (2008). Rice grain zinc concentrations as affected by genotype, native soil-zinc availability, and zinc fertilization. Plant Soil 306 37–48 10.1007/s11104-007-9368-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Wu L., Wang M. (2008). Can iron and zinc in rice grains (Oryza sativa L.) be biofortified with nitrogen fertilization under pot conditions? J. Sci. Food Agric. 88 1172–1177 10.1002/jsfa.3194 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Xu Y.-H., Yi H.-Y., Gong J.-M. (2012). Vacuolar membrane transporters OsVIT1 and OsVIT2 modulate iron translocation between flag leaves and seeds in rice. Plant J. 72 400–410 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05088.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L., Cheng Z., Ai C., Jiang X., Bei X., Zheng Y., et al. (2010). Nicotianamine, a novel enhancer of rice iron bioavailability to humans. PLoS ONE 5:e10190. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo Y., Zhang F. (2011). Soil and crop management strategies to prevent iron deficiency in crops. Plant Soil 339 83–95 10.1007/s11104-010-0566-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]