Abstract

Objective To determine the risk of neuropsychiatric adverse events associated with use of varenicline compared with placebo in randomised controlled trials.

Design Systematic review and meta-analysis comparing study effects using two summary estimates in fixed effects models, risk differences, and Peto odds ratios.

Data sources Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and clinicaltrials.gov.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies Randomised controlled trials with a placebo comparison group that reported on neuropsychiatric adverse events (depression, suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, suicide, insomnia, sleep disorders, abnormal dreams, somnolence, fatigue, anxiety) and death. Studies that did not involve human participants, did not use the maximum recommended dose of varenicline (1 mg twice daily), and were cross over trials were excluded.

Results In the 39 randomised controlled trials (10 761 participants), there was no evidence of an increased risk of suicide or attempted suicide (odds ratio 1.67, 95% confidence interval 0.33 to 8.57), suicidal ideation (0.58, 0.28 to 1.20), depression (0.96, 0.75 to 1.22), irritability (0.98, 0.81 to 1.17), aggression (0.91, 0.52 to 1.59), or death (1.05, 0.47 to 2.38) in the varenicline users compared with placebo users. Varenicline was associated with an increased risk of sleep disorders (1.63, 1.29 to 2.07), insomnia (1.56, 1.36 to 1.78), abnormal dreams (2.38, 2.05 to 2.77), and fatigue (1.28, 1.06 to 1.55) but a reduced risk of anxiety (0.75, 0.61 to 0.93). Similar findings were observed when risk differences were reported. There was no evidence for a variation in depression and suicidal ideation by age group, sex, ethnicity, smoking status, presence or absence of psychiatric illness, and type of study sponsor (that is, pharmaceutical industry or other).

Conclusions This meta-analysis found no evidence of an increased risk of suicide or attempted suicide, suicidal ideation, depression, or death with varenicline. These findings provide some reassurance for users and prescribers regarding the neuropsychiatric safety of varenicline. There was evidence that varenicline was associated with a higher risk of sleep problems such as insomnia and abnormal dreams. These side effects, however,are already well recognised.

Systematic review registration PROSPERO 2014:CRD42014009224.

Introduction

Smoking is the major avoidable cause of preventable morbidity and premature mortality in the United Kingdom and internationally.1 2 Researchers have estimated that smoking related illnesses cost the National Health Service (NHS) about £5bn (€7bn, $8bn) annually.3 Varenicline was first licensed in the UK in 2006. Randomised controlled trials have shown it to be the most clinically effective drug for short term abstinence in smoking cessation.4 Concerns about its neuropsychiatric safety, however, led the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) to issue warnings about varenicline in the UK in 2008.5 Similarly, since 2009, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has required the addition of a black box warning (the strongest safety warning that can be issued by the agency) to the labelling of varenicline.6 These warnings were based on spontaneous reports of adverse drug reactions from the yellow card scheme and the FDA adverse events reporting system.

Since the original safety warnings, several studies have investigated the neuropsychiatric safety of varenicline.7 8 9 10 Most of the studies were observational cohorts,7 8 9 although one study examined the risk in a meta-analysis of 17 industry sponsored trials.10 None of the studies found evidence of an increased risk of depression, suicide, or non-fatal self harm with varenicline. Two major concerns, however, have been raised about the validity of these findings. Firstly, observational studies are prone to confounding by indication.11 For example, the use of drugs for smoking cessation might seem to be associated with an increased risk of suicide because smokers themselves are at increased risk of mental illness and suicide.12 13 Secondly, there is evidence that industry sponsored trials are more likely than other trials to report outcomes that are favourable to the study sponsor.14 Though the number of prescription items of varenicline dispensed in England increased from 499 in 2006 to a peak of almost a million in 2011, there was a 25% decrease from 2011 to 2013.15 This might reflect ongoing fears among prescribers and patients regarding varenicline’s safety.

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the risk of neuropsychiatric adverse events and death in all published placebo controlled randomised controlled trials of varenicline. This review deals with some of the limitations of the previous studies and is the most comprehensive published review to date of the neuropsychiatric safety of varenicline.

Methods

Eligibility and literature search

We sought all placebo controlled randomised controlled trials of any duration in humans of varenicline at the maximum dose (1 mg twice daily) as described in the recommended standard titration regimen for varenicline (www.chantix.com). We included studies in smokers and non-smokers. We conducted searches of computer databases and online clinical trial registries (Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and clinicaltrials.gov). The search strategy is shown in appendix 1. The searches were performed from the inception of each of the databases to 9 May 2014. There were no language restrictions. We manually searched reference lists of relevant research articles and previous systematic reviews.10 16

Outcome measures

Our primary outcome measures were neuropsychiatric adverse events comprising suicide, attempted suicide, suicidal ideation, and depression. Secondary outcomes included other neuropsychiatric outcomes (abnormal dreams, aggression, anxiety, fatigue, insomnia, irritability, sleep disorders, somnolence) and death. We included all deaths, regardless of whether or not we believed they were related to drug treatment.

Data extraction and management

Two reviewers (KHT and DWK) independently screened the identified studies by title and abstract against the eligibility criteria. We then obtained full reports of studies for a second round of screening. We identified duplicate publications for exclusion by examining the study name, authors, study population, location, and the dates of duration of the study. A third reviewer (DG) reviewed all excluded studies and studies when there was disagreement regarding inclusion or exclusion.

KHT (all papers) and DG and RMM (papers equally shared) performed double data extraction to collect information on the study design (duration of treatment, description of allocation concealment, and blinding), study participants (inclusion and exclusion criteria, country, region, population studied, and baseline characteristics such as ethnicity, sex, smoking history), description of the intervention and placebo groups, primary and secondary outcomes, measures of efficacy of treatment, losses to follow-up, and study sponsor. KHT contacted authors of all studies to verify the accuracy of the extracted data.

Assessment of risk of bias

The Cochrane tool for assessing the risk of bias was used to assess whether there was high, low, or unclear risk of bias in the following domains: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias.17 KHT (all papers) and DG and RMM (papers equally shared) assessed the risk of bias. Discrepancies were resolved by referring to the original publications and discussion among all three reviewers. KHT also contacted study authors to obtain study protocols and additional information that might not have been published to aid with assessment of the risk of bias.

Statistical analysis

We described study characteristics according to sample size, characteristics of study participants, study duration, duration of treatment, and source of funding. For trials with more than two intervention groups, we extracted data for the maximum dose of varenicline (that is, 1 mg twice daily) and the placebo group. The “metan” command in Stata (version 13, StataCorp, USA) was used to conduct all of the meta-analyses.18 Because our outcomes of interest are rare, we followed recommendations of Bradburn and colleagues19 and used Peto odds ratios to compare the varenicline and placebo groups. We also undertook meta-analyses using Mantel-Haenszel risk differences. We report results including 95% confidence intervals and forest plots for both measures so that findings can be compared. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed with the I2 statistic.20

For sensitivity analyses, we used inverse variance methods under fixed and random effects models for the outcomes with the largest number of treatment events; random effects models can be problematic for meta-analyses of rare events.21 We report subgroup analyses for the primary outcomes by age (<40 v ≥40), sex (<50% male v ≥50% male), ethnicity (<50% white v ≥50% white), presence or absence of psychiatric illness, smoking status (smokers including smokeless tobacco users v majority non-smokers (>60% non-smokers)), and whether or not the study was sponsored by a pharmaceutical company. Studies were not categorised as sponsored by a pharmaceutical company if the drug was provided at no cost by the manufacturer and/or if the research was investigator initiated—that is, the drug and some funding was provided by the manufacturer although there was no other involvement in study conduct or publication and data were independently held by the researchers. Tests for subgroup differences were performed. Funnel plot asymmetry was assessed for two outcome—depression and insomnia—with Harbord’s modified test for small study effects with the “metafunnel” and “metabias” commands in Stata.22 23

Results

Study characteristics

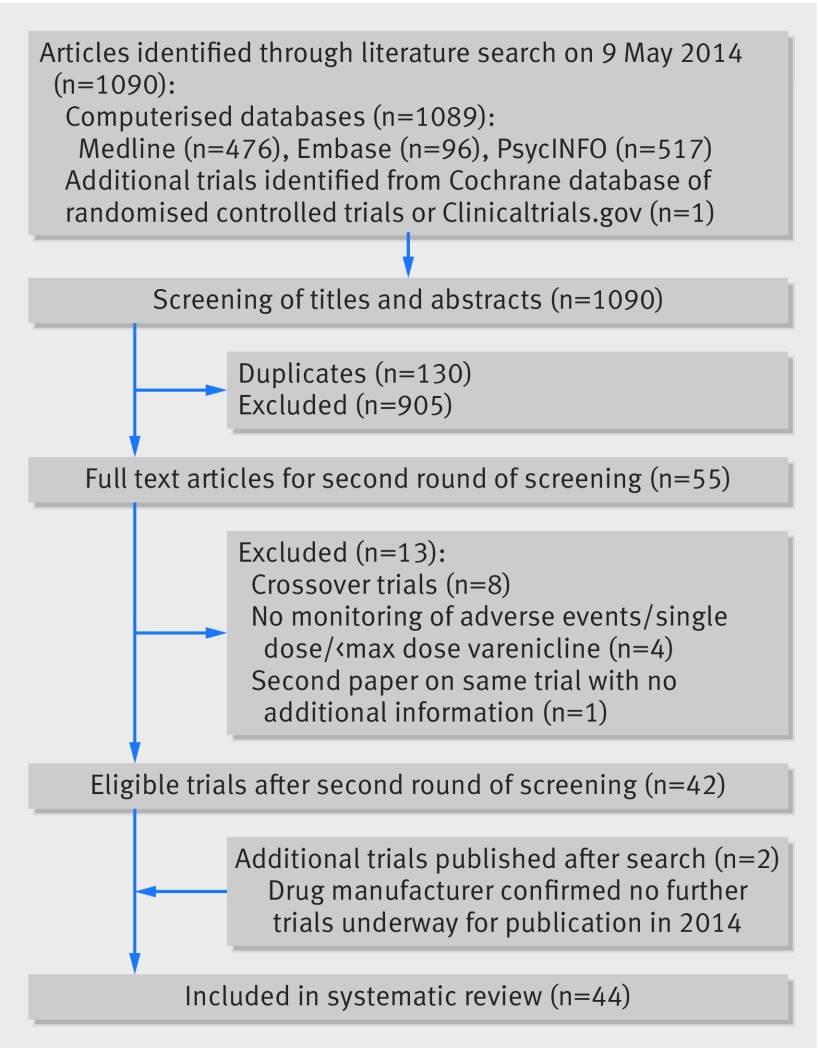

Figure 1 summarises the selection of studies. The search strategy identified 1089 studies from the computerised databases (476 from Medline, 517 from PsycINFO, and 96 from Embase). One additional trial was identified from CENTRAL and clinical.trials.gov. Out of the 1090 studies, 130 were duplicates and 905 were excluded based on screening of titles and abstracts; therefore 55 papers met the criteria for further screening. After the second round of screening, 42 trials were identified for further data extraction.24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 Two additional studies were identified when the search was repeated for the week beginning Monday 4 August 2014.66 67 Forty four studies were included in the systematic review. We received responses from study authors for 33 studies (75%).

Fig 1 Flow chart showing selection of randomised controlled trials for inclusion in systematic review of varenicline

Table 1 and appendix 2 describe study characteristics. The trials included 11 146 participants (6015 patients were randomised to receive a maximum of varenicline 1 mg twice daily and 5131 patients received a placebo). Of these randomised patients, 10 998 were evaluable for adverse events (5931 in the varenicline group and 5067 in the placebo group). The duration of treatment ranged from one week to 52 weeks, while study duration ranged from eight days to 53 weeks. Eighteen trials (61.3% of all participants) included cigarette smokers from the general population with no history of psychiatric illnesses (table 2). In trials that included cigarette smokers (39 trials) participants smoked an average of 20 cigarettes a day for 26.6 years in the varenicline group and 20 cigarettes a day for 26.2 years in the placebo group. Loss to follow-up ranged from 0% to 60% in both groups (appendix 2). In 12 trials losses to follow-up were higher in the varenicline group than the placebo group, whereas in 17 trials losses to follow-up were higher in the placebo group than the varenicline group.

Table 1.

Characteristics of randomised controlled trials of varenicline 1mg twice daily included in systematic review

| Study | Duration (weeks) | Sample size | Mean age (years) | % Men | % White | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Treatment | Varenicline | Placebo | Varenicline | Placebo | Varenicline | Placebo | Varenicline | Placebo | |||||

| Anthenelli, 201324 | 52 | 12 | 256 | 269 | 45.4 | 47.1 | 37.9 | 36.8 | NA | NA | ||||

| Bolliger, 201125 | 24 | 12 | 394 | 199 | 43.1 | 43.9 | 57.7 | 65.7 | 30.3 | 31.3 | ||||

| Brandon, 201126 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 56 | 58 | 45.8 | 41.2 | 60.9 | 61.1 | 54.1 | 64.8 | ||||

| Burstein, 200627 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 8 | 8 | 68.1 | 67.9 | 75 | 50 | 50 | 37.5 | ||||

| Chengappa, 201466 | 24 | 12 | 31 | 29 | 45.7 | 46.2 | 29 | 34.5 | 64.5 | 72.4 | ||||

| Cinciripini, 201328 | 24 | 12 | 86 | 106 | 43.8 | 45.2 | 61.6 | 63.2 | 58.1 | 71.7 | ||||

| Ebbert, 201129 | 24 | 12 | 38 | 38 | 40.7 | 41 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||||

| Evins, 201430 | 64 | 40 | 40 | 47 | 51.4 | 45.7 | 60 | 66 | 75 | 72 | ||||

| Faessel, 200931 | 2.6 | 2 | 14 | 7 | 15.4 | 15.4 | 57.1 | 57.1 | 85.7 | 71.4 | ||||

| Fagerstrom, 201032 | 26 | 12 | 213 | 218 | 43.9 | 43.9 | 89 | 90 | 99 | 100 | ||||

| Fatemi, 201333 | 12 | 12 | 6 | 9 | 40.4 | 41.4 | 83.3 | 77.8 | 50 | 88.9 | ||||

| Garza, 201134 | 16 | 12 | 55 | 55 | 33.4 | 33.8 | 60 | 72.7 | 80 | 70.9 | ||||

| Gonzales, 200635 | 52 | 12 | 352 | 344 | 42.5 | 42.6 | 50 | 54.1 | 79.5 | 76.2 | ||||

| Gonzales, 201467 | 52 | 12 | 251 | 247 | 47.7 | 47.3 | 49.8 | 49.4 | 94.8 | 91.4 | ||||

| Hughes, 201136 | 24 | 8 | 107 | 111 | 44 | 41.2 | 60.5 | 57.2 | 91.4 | 91.9 | ||||

| Jorenby, 200637 | 52 | 12 | 344 | 341 | 44.6 | 42.3 | 55.2 | 58.1 | 85.5 | 85 | ||||

| Litten, 201338 | 16 | 13 | 97 | 101 | 46 | 45 | 73.2 | 68.3 | 61.9 | 70.3 | ||||

| McClure, 201339 | 5 | 5 | 54 | 50 | 45 | 43 | 40 | 59 | 32 | 36 | ||||

| McKee, 200940 | 1.1 | 1 | 10 | 10 | 34.2 | 35.3 | 80 | 80 | 40 | 90 | ||||

| Meszaros, 201341 | 12 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 42 | 44 | 80 | 60 | 40 | 60 | ||||

| Mitchell, 201242 | 16 | 12 | 33 | 31 | 29 | 25 | 55 | 65 | 73 | 64 | ||||

| Nakamura, 200743 | 52 | 12 | 156 | 154 | 40.1 | 39.9 | 79.2 | 76 | NA | NA | ||||

| Niaura, 200844 | 40 | 12 | 160 | 160 | 41.5 | 42.1 | 50.3 | 53.5 | 93 | 88.4 | ||||

| Nides, 200645 | 52 | 7 | 127 | 127 | 41.9 | 41.6 | 50.4 | 52 | 85.6 | 87.8 | ||||

| Oncken, 200646 | 52 | 12 | 259 | 129 | 42.2 | 43 | 48.5 | 51.9 | 80.8 | 72.1 | ||||

| Plebani, 201247 | 9 | 8 | 18 | 19 | NA | NA | 69.6 | 75 | 11 | 33 | ||||

| Plebani, 201348 | 13 | 12 | 19 | 21 | 44.8 | 48.1 | 78.9 | 90.5 | 42.1 | 71.4 | ||||

| Poling, 201049 | 12 | 11 | 13 | 18 | 36.5 | 34.4 | 84.6 | 77.8 | 46.2 | 72.2 | ||||

| Rennard, 201250 | 24 | 12 | 493 | 166 | 43.9 | 43.2 | 60 | 59.6 | 68 | 68.1 | ||||

| Rigotti, 201051 | 52 | 12 | 355 | 359 | 57 | 55.9 | 75.2 | 82.2 | 80.3 | 80.8 | ||||

| Shim, 201252 | 8 | 8 | 60 | 60 | 39.9 | 39.9 | 38 | 45 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Stein, 201353 | 24 | 24 | 137 | 45 | 39.2 | 40.6 | 46 | 62.2 | 82.5 | 75.6 | ||||

| Steinberg, 201154 | 24 | 12 | 40 | 39 | NA | NA | 60 | 59 | 77 | 67 | ||||

| Tashkin, 201155 | 52 | 12 | 250 | 254 | 57.2 | 57.1 | 62.5 | 62.2 | 81.9 | 84.1 | ||||

| Tonnesen, 201356 | 52 | 12 | 70 | 69 | 53.6 | 55.6 | 42.9 | 49.3 | NA | NA | ||||

| Tonstad, 200657 | 52 | 12 | 603 | 607 | 45.4 | 45.3 | 50.2 | 48.3 | 96.7 | 97 | ||||

| Tsai, 200758 | 24 | 12 | 126 | 124 | 39.7 | 40.9 | 84.9 | 92.7 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Wang, 200959 | 24 | 12 | 165 | 168 | 39 | 38.5 | 96.4 | 97 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Weiner, 201160 | 12 | 12 | 4 | 5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| Williams, 200761 | 53 | 52 | 251 | 126 | 48.2 | 46.6 | 50.6 | 48.4 | 86.9 | 92.1 | ||||

| Williams, 201262 | 26 | 12 | 84 | 43 | 40.2 | 43 | 77.4 | 76.7 | 59.5 | 58.1 | ||||

| Wong, 201263 | 52 | 12 | 151 | 135 | 51.9 | 53.3 | 55 | 50.4 | NA | NA | ||||

| Zesiewicz, 201264 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 47.4 | 53.8 | 44 | 67 | NA | NA | ||||

| Zhao, 201165 | 3.7 | 3 | 14 | 10 | 71 | 73 | 42.9 | 50 | 100 | 90 | ||||

NA=not applicable.

Table 2.

Summary of characteristics of patients enrolled in 44 randomised controlled trials of varenicline

| Characteristics of trial participants | No of trials |

|---|---|

| Smokers from general population | 18 |

| Smokers with psychiatric illness | 8 |

| Heavy drinking smokers/alcohol dependence | 4 |

| People dependent on cocaine or opioid dependent | 3 |

| Smokeless tobacco users | 2 |

| Smokers with mild to moderate COPD | 1 |

| Smokers with cardiovascular disease | 1 |

| Smokers about to undergo surgery | 1 |

| Patients with spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 | 1 |

| Adolescent smokers | 1 |

| Elderly non-smokers | 1 |

| Smokers in hospital | 1 |

| Smokers previously treated with varenicline | 1 |

| Ex-smokers on long term NRT | 1 |

COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NRT=nicotine replacement therapy.

Table 3 shows the assessment of risk of bias . We excluded five trials from the meta-analysis as the risk of bias was unclear in four or more of the six domains47 52 60 or because no data were reported in the published papers and the study authors did not respond to our requests for data.48 49 52 This resulted in exclusion of 114 patients (1.9%) from the varenicline group and 123 patients (2.4%) from the placebo group; 10 761 patients were included in the meta-analyses (5817 in the varenicline group and 4944 in the placebo group). In three trials39 41 42 there were high losses to follow-up, 53.7%, 60%, and 45.2%, respectively. These studies were assessed as low risk of bias because of incomplete outcome data and were not excluded. They were all small trials (combined total of n=92 in the varenicline group (1.6% of all people randomised to varenicline in our meta-analysis) and n=86 in the placebo group (1.7% of all people randomised to placebo)). In addition, only nine out of 178 patients (5.1%) were lost to follow-up because of adverse events, and these were mostly gastrointestinal in nature (such as nausea and vomiting).39 42 41

Table 3.

Risk of bias assessment for each trial of varenicline using Cochrane risk of assessment of bias tool

| Study | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment used | Blinding | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | Other bias | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants and personnel | Outcome assessment | ||||||

| Anthenelli 201324 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Bolliger 201125 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Brandon 201126 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Burstein 200627 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Chengappa 201466 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Cinciripini 201328 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Ebbert 201129 | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Evins 201430 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Faessel 200931 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Fagerstrom 201032 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Fatemi 201333 | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Garza 201134 | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Gonzales 206635 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Gonzales 201467 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Hughes 201136 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Jorenby 200637 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Litten 201338 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| McClure 201339 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| McKee 200940 | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low |

| Meszaros 201341 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Mitchell 201242 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Nakamura 200743 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Niaura 200844 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Nides 200645 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Oncken 200646 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Plebani 201247 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Plebani 201348 | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low |

| Poling 201049 | Low | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low |

| Rennard 201250 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Rigotti 201051 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Shim 201252 | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Stein 201353 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Steinberg 201154 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Tashkin 201155 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Tonnesen 201356 | Low | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Tonstad 200657 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Tsai 200758 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Wang 200959 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear |

| Weiner 201160 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Unclear |

| Williams 200761 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Williams 201262 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Wong 201263 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Zesiewicz 201264 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Zhao 201165 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear |

Risk of neuropsychiatric adverse events and death

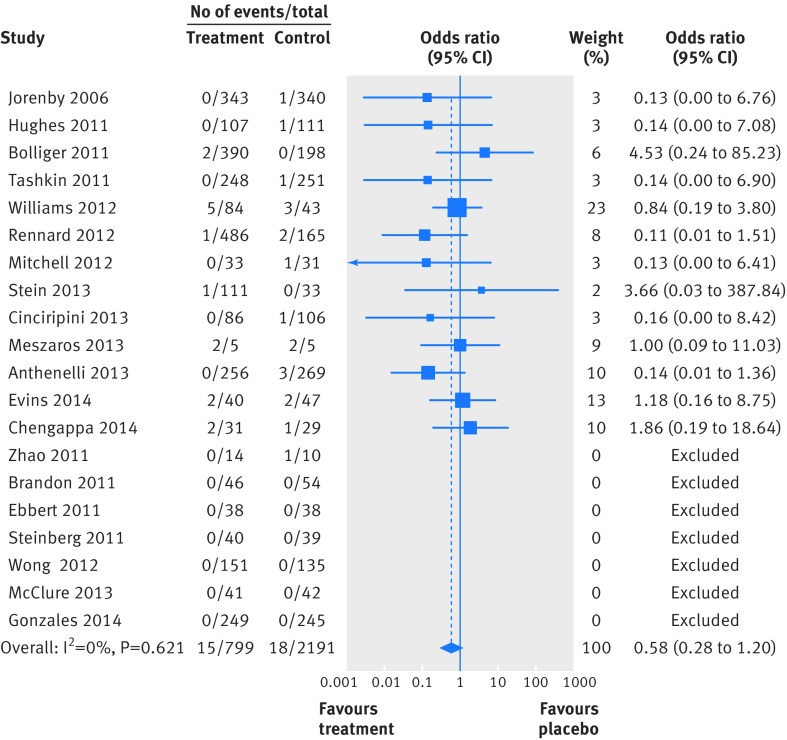

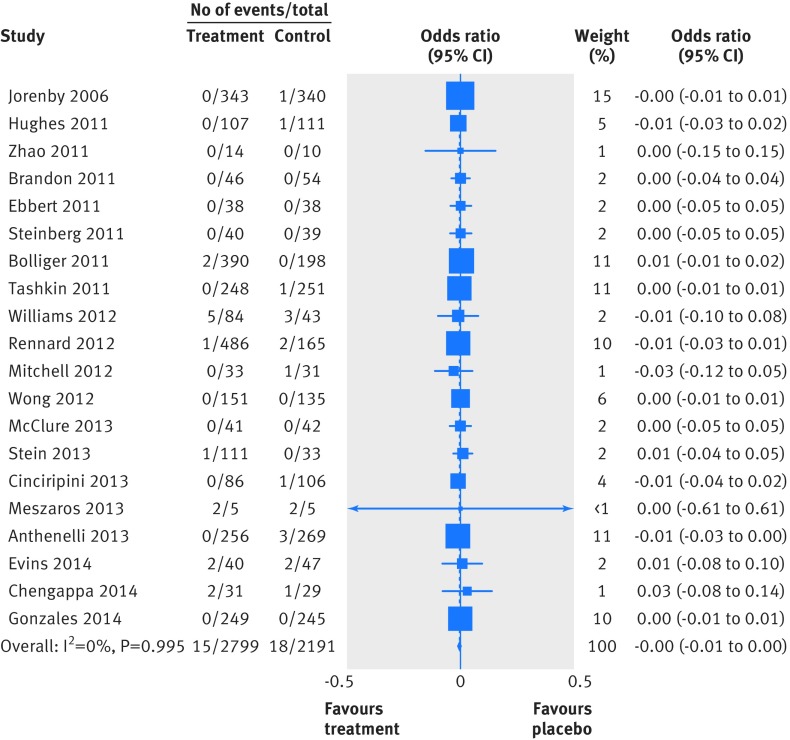

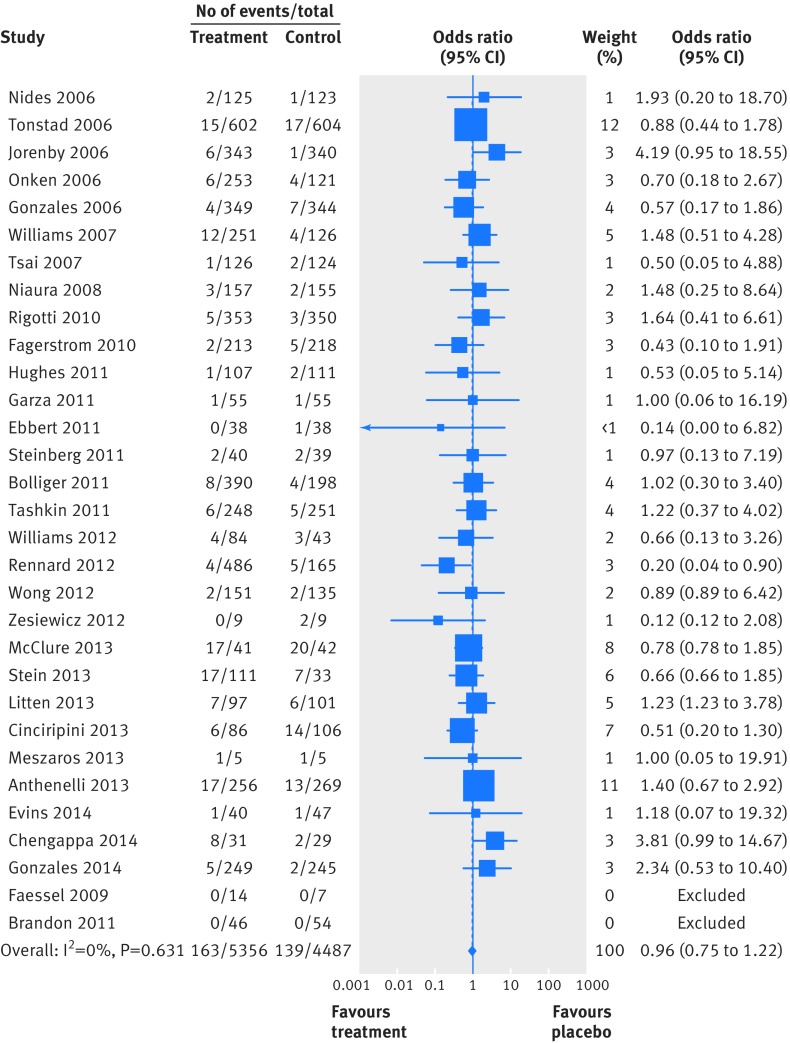

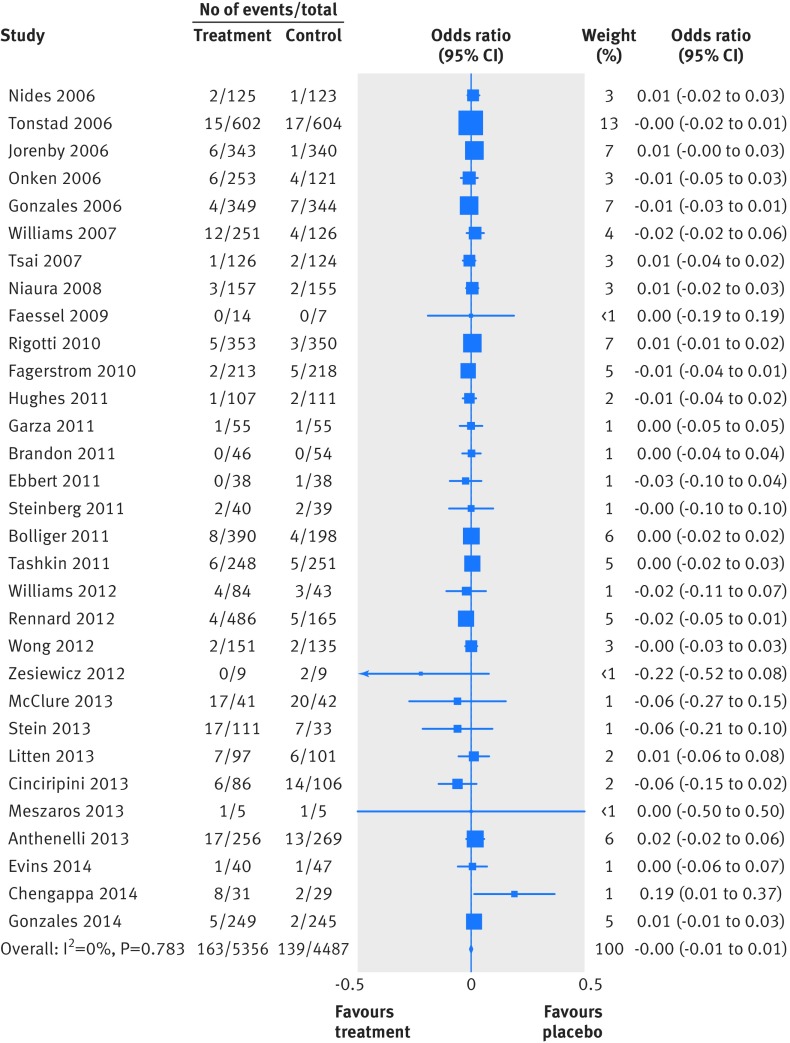

Two people died by suicide (both in the varenicline arms) and four attempted to do so (two in the varenicline arm and two in the placebo arm). Table 4 summarises the Peto odds ratios, risk differences, and 95% confidence interval for the primary and secondary outcomes. Because of the small numbers of events, we combined suicide and attempted suicide into a single outcome. Thirty one trials reported suicide and suicide attempt; the Peto odds ratio for varenicline versus placebo was 1.67 (95% confidence interval 0.33 to 8.57; P=0.54, I2=10.3%) and the risk difference was 0.0003 (−0.002 to 0.003; P=0.81, I2=0.0%). Twenty trials reported suicidal ideation (figs 2 and 3); the Peto odds ratio was 0.58 (0.28 to 1.20; P=0.14, I2=0.0%) and the risk difference was −0.003 (−0.009 to 0.002; P=0.24, I2=0.0%). Thirty one trials reported on depression (figs 4 and 5); the Peto odds ratio was 0.96 (0.75 to 1.22; P=0.74, I2=0.0%) and the risk difference was −0.001 (−0.01 to 0.01; P=0.74, I2=0.0%). Death was reported in 36 trials (total 13/5760 in the varenicline group and 11/4887 in the placebo group). The Peto odds ratio for death was 1.05 (0.47 to 2.38; P=0.9, I2=38.7%), and there was no evidence of an increased risk of death in the varenicline group compared with the placebo group (risk difference 0.0001, −0.003 to 0.003; P=0.94, I2=0.0%) (table 4). The forest plots for the secondary outcomes are shown in appendix 3.

Table 4.

Summary of Peto odds ratios, risk differences, and 95% confidence intervals for neuropsychiatric events in people treated with varenicline

| Neuropsychiatric adverse event | No of events/No treated | Odds ratio (95% CI), P value | Risk difference (95% CI), P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Varenicline group | Placebo group | |||

| Primary outcomes | ||||

| Depression | 163/5356 | 139/4487 | 0.96 (0.75 to 1.22), 0.74 | −0.001 (−0.01 to 0.01), 0.74 |

| Suicidal ideation | 15/2799 | 18/2191 | 0.58 (0.28 to 1.20), 0.14 | −0.003 (−0.009 to 0.002), 0.24 |

| Attempted suicide | 2/2184 | 2/1842 | 0.75 (0.10 to 5.65), 0.78 | −0.0003 (−0.005 to 0.004), 0.91 |

| Suicide and attempted suicide | 4/5352 | 2/4478 | 1.67 (0.33 to 8.57), 0.54 | 0.0003 (−0.002 to 0.003), 0.81 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| Abnormal dreams | 603/5606 | 224/4741 | 2.38 (2.05 to 2.77), <0.001 | 0.06 (0.05 to 0.07), <0.001 |

| Aggression | 39/4276 | 24/3524 | 0.91 (0.52 to 1.59), 0.75 | −0.001 (−0.005 to 0.004), 0.79 |

| Anxiety | 209/4999 | 226/4457 | 0.75 (0.61 to 0.93), 0.008 | −0.01 (−0.02 to -0.0003), 0.01 |

| Death | 13/5760 | 11/4887 | 1.05 (0.47 to 2.38), 0.9 | 0.0001 (−0.003 to 0.003), 0.94 |

| Fatigue | 283/5502 | 202/4701 | 1.28 (1.06 to 1.55), 0.01 | 0.01 (0.002 to 0.02), 0.01 |

| Insomnia | 679/5621 | 379/4762 | 1.56 (1.36 to 1.78), <0.001 | 0.04 (0.03 to 0.05), <0.001 |

| Irritability | 293/5406 | 266/4615 | 0.98 (0.81 to 1.17), 0.79 | −0.001 (−0.01 to 0.008), 0.79 |

| Sleep disorders | 211/5081 | 123/4284 | 1.63 (1.29 to 2.07), <0.001 | 0.02 (0.01 to 0.02), <0.001 |

| Somnolence | 139/5360 | 91/4542 | 1.23 (0.94 to 1.62), 0.13 | 0.005 (−0.001 to 0.01), 0.13 |

Fig 2 Forest plot of risk of suicidal ideation events (Peto odds ratio) associated with varenicline use in 20 placebo controlled randomised trials

Fig 3 Forest plot of risk of suicidal ideation events (Mantel-Haenszel risk difference) associated with varenicline use in 20 placebo controlled randomised trials

Fig 4 Forest plot of risk of depression events (Peto odds ratio) associated with varenicline use in 31 placebo controlled randomised trials

Fig 5 Forest plot of risk of depression events (Mantel-Haenszel risk difference) associated with varenicline use in 31 placebo controlled randomised trials

We found no evidence of an increased risk of irritability (odds ratio 0.98, 05% confidence interval 0.81 to 1.17; P=0.79, I2=0.0%), aggression (0.91, 0.52 to 1.59; P=0.75, I2=20.8%), or somnolence (1.23, 0.94 to 1.62; P=0.13, I2=10.4%) as the confidence intervals included the null value of 1. Varenicline was associated with an increased risk of sleep disorders (1.63, 1.29 to 2.07; P<0.001, I2=0.0%), insomnia (1.56, 1.36 to 1.78; P<0.001, I2=0.0%), abnormal dreams (2.38, 2.05 to 2.77; P<0.001, I2=22.3%), and fatigue (1.28, 1.06 to 1.55; P=0.01, I2=6.3%), with some evidence of a reduced risk of anxiety (0.75, 0.61 to 0.93; P=0.008, I2=5.7%). Consistent findings were observed for the risk differences (table 4).

Sensitivity analyses

There were minimal differences in the effect measures and 95% confidence intervals with Peto, fixed effects, and random effects odds ratios (table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of Peto, fixed effects, and random effects odds ratios (OR) for insomnia, sleep disorders, and abnormal dreams in people treated with varenicline

| Neuropsychiatric adverse event | No of events/No treated | Odds ratio (95% CI)* | Test for heterogeneity (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Varenicline group | Placebo group | |||

| Insomnia | ||||

| Peto OR | 679/5621 | 379/4762 | 1.56 (1.36 to 1.78), | 0 |

| Fixed effects OR | 679/5621 | 379/4762 | 1.56 (1.35 to 1.79) | 0 |

| Random effects OR | 679/5621 | 379/4762 | 1.56 (1.35 to 1.79) | 0 |

| Sleep disorders | ||||

| Peto OR | 211/5081 | 123/4284 | 1.63 (1.29 to 2.07) | 0 |

| Fixed effects OR | 211/5081 | 123/4284 | 1.57 (1.22 to 2.03) | 0 |

| Random effects OR | 211/5081 | 123/4284 | 1.57 (1.22 to 2.03) | 0 |

| Abnormal dreams | ||||

| Peto OR | 603/5606 | 224/4741 | 2.38 (2.05 to 2.77) | 22.3 |

| Fixed effects OR | 603/5606 | 224/4741 | 2.37 (1.99 to 2.82) | 31.6 |

| Random effects OR | 603/5606 | 224/4741 | 2.36 (1.87 to 2.98) | 31.6 |

*All P<0.001.

Subgroup analyses

The subgroup analyses are shown in appendix 4 for the primary outcomes of depression and suicidal ideation. Subgroup tests showed no evidence of a variation in the side effects of depression and suicidal ideation by age group (P=0.391 and P=0.933, respectively, for interaction), percentage of men in the study (P=0.418 and P=0.925), percentage of white people in the study (P=0.685 and P=0.254), presence or absence of psychiatric illness (P=0.126 and P=0.304), smoking status (P=0.906 for depression but not calculated for suicidal ideation as there were no reports of suicidal ideation in studies that included non-smokers), and whether the trial was industry sponsored or not (P=0.386 and P=0.380). The effect estimates (odds ratio) for the trials in which all participants had psychiatric illnesses compared with those where none of the participants had psychiatric illness were 1.49 (95% confidence interval 0.84 to 2.65) versus 0.91 (0.69 to 1.21) for depression and 0.79 (0.32 to 1.93) versus 0.34 (0.09 to 1.29) for suicidal ideation.

Small study effects

The funnel plots for depression and insomnia are shown in appendix 5. The P values for funnel plot asymmetry were 0.53 for depression and 0.93 for insomnia (that is, there was no evidence against the null hypothesis of no small study effects).

Discussion

This meta-analysis of 39 randomised controlled trials, involving 5817 patients prescribed varenicline 1 mg twice daily and 4944 patients prescribed placebo, found no increased risk of suicide or attempted suicide, suicidal ideation, depression, or death in individuals treated with varenicline. Almost half of the trial participants were chronic heavy smokers (that is, they had smoked on average 20 cigarettes a day for 26 years). Five separate trials (including 1281 participants randomised to varenicline and 1143 to placebo) reported a suicide and/or suicide attempt (see appendix 3); one reported suicide only, three reported attempted suicide only, and one reported both suicide and attempted suicide. Two suicides and two attempts occurred in the varenicline group of the trials (0.08%) and two attempts occurred in the placebo group (0.05%). Use of the maximum dose of varenicline (1 mg twice daily) was associated with a 28% increased risk of fatigue, a 56% increased risk of insomnia, a 63% increased risk of sleep disorders, and more than twice the risk of abnormal dreams. There was evidence of a 25% reduction in the risk of anxiety. When we used risk differences, for every 1000 patients there were an additional 10 cases of fatigue, 40 cases of insomnia, 20 cases of sleep disorders, and 60 cases of abnormal dreams in those prescribed varenicline compared with placebo. Similarly, there were 10 fewer episodes of anxiety per 1000 participants in the varenicline group compared with the placebo group (risk difference −0.01, 95% confidence interval −0.02 to −0.0003). There was no evidence of a variation in depression and suicidal ideation by age, sex, ethnicity, presence or absence of psychiatric illness, or type of study sponsor.

Comparison with other studies

A recent study by Kishi and Iwata examined the effects of varenicline for smoking cessation in people with schizophrenia in a meta-analysis of seven randomised controlled trials.68 With the exception of the study by Hong and colleagues,69 we included all their randomised controlled trials in the current analysis. Similar to our findings, Kishi and Iwata found no significant differences in depression and suicidal ideation between the varenicline and placebo groups. They reported, however, that varenicline use was associated with a lower risk of abnormal dreams/nightmares than placebo (relative risk 0.47, 95% confidence interval 0.22 to 0.99; P=0.05).68 This discrepancy with our findings could be explained by the small sample size of their study (288 from four randomised controlled trials versus 10 347 from 35 randomised controlled trials in our analysis).

Gibbons and Mann used pooled data from 17 randomised controlled trials sponsored by Pfizer to examine neuropsychiatric adverse events associated with varenicline.10 Our study included industry and non-industry sponsored trials and more than twice the number of trials that they included. Their findings of no increased risk of suicidal events, depression, and agitation are consistent with our study. Although the authors did not include references to the published literature for their included studies (which made cross referencing difficult), it is likely that we included most of their studies in our analysis.

Another meta-analysis examined the long term efficacy and safety of varenicline in trials with a minimum follow-up period of 12 months.70 A meta-analysis of the main psychiatric related adverse effects (which combined depressed mood, other mood disorders, bipolar disorder, delirium, suicidal and self injurious behaviours, adjustment disorders, and abnormal thinking into a single outcome) did not show a “significant increase of psychiatric side effects for varenicline compared with placebo.”70 This meta-analysis, however, included only three trials, and the combined psychiatric outcome was non-specific. The authors reported an increased risk of insomnia (relative risk 1.65, 95% confidence interval 1.29 to 2.11), abnormal dreams (2.78, 2.07 to 3.73), and sleep disturbance (2.09, 1.62 to 2.69) but no increased risk of irritability (1.14, 0.75 to 1.73), which is consistent with our findings.70

A previous Cochrane review examined the efficacy and tolerability of nicotine receptor partial agonists including varenicline.16 Trials were excluded if participants used smokeless tobacco or if there was less than six months of follow-up. In addition to the efficacy outcomes, meta-analyses were performed for the most commonly reported adverse events: nausea, insomnia, abnormal dreams, and headache. Findings were consistent with our study for insomnia (relative risk 1.62, 95% confidence interval 1.40 to 1.88) and abnormal dreams (2.91, 2.34 to 3.62).16 The Cochrane review did not report any treatment emergent deaths. Although we used a broader definition of deaths in our analysis by including all deaths irrespective of whether or not we thought they were related to treatment, we did not find an increased risk of death in the varenicline group.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive published systematic review (and meta-analysis) of neuropsychiatric effects associated with use of varenicline. Compared with the previous Cochrane review,16 our analysis included 16 additional trials for the meta-analysis of the risk of insomnia events and 23 additional trials for the pooled analysis of abnormal dreams.

The choice of summary statistics for meta-analyses of rare events caused controversy (about whether the Peto odds ratio should be reported instead of risk differences) when it led to conflicting findings from two systematic reviews examining the risk of cardiovascular side effects associated with varenicline use.71 72 We present results using both measures: a relative measure (Peto odds ratio and sensitivity analyses with fixed and random effects odds ratios) as well as an absolute measure (risk difference). Findings were consistent for all examined outcomes.

Many study authors did not specify the actual dates that adverse events were reported so we included all reported events; this decision would have increased the likelihood of obtaining reports of rare adverse events. We contacted authors for all of our included trials to check the data extracted on adverse events and for study protocols and other information to adequately assess the risk of bias in the studies. We had a high response rate (75%).

There are some limitations. Firstly, in this analysis we used study level data instead of individual level data so we were unable to determine whether differences in the adverse events were because of greater quit rates in the varenicline group relative to placebo. Secondly, because of the small number of suicides and attempted suicide reported (n=6), we cannot rule out major beneficial or adverse effects of varenicline for this outcome (Peto odds ratio 1.67, 95% confidence interval 0.33 to 8.57). Thirdly, there was potential for heterogeneity in the reporting of adverse events. Authors used a range of methods to record adverse events including self report, open ended questions, structured questionnaires, side effect checklists, and case reports coded to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA, www.meddra.org). All of the industry sponsored trials coded adverse events using MedDRA. Fourthly, we excluded two studies69 73 from the review as the maximum dose of varenicline used in these studies was only 1 mg once a day—that is, half of the recommended maximum dose. Hong and colleagues examined varenicline treatment in 20 smokers and 15 non-smokers with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and found no evidence that varenicline worsened psychiatric symptoms in these patients.69 Mocking and colleagues studied the effects of varenicline on emotional and cognitive processing in 21 healthy adult non-smokers and concluded that it did not cause problems in emotional processing or impulsivity, providing less support for a possible depressogenic effect of varenicline.73 Furthermore, a secondary analysis, which included all doses of varenicline in the original trials and these two excluded randomised controlled trials, produced similar findings to our main analysis (see appendix 6).

We tried to minimise reporting bias by including all events (such as deaths) reported regardless of whether or not we considered them to be related to treatment. It is still possible, however, that reporting bias could have occurred as for certain trials, where the corresponding authors did not respond to our requests for additional information, we could not determine whether a lack of reporting of deaths in the published paper was synonymous with no deaths. It was difficult to interpret the funnel plots to assess whether publication bias might be present as most trials were efficacy trials and were not performed solely to determine the incidence of psychiatric adverse events.

Additionally, smoking cessation has been shown to have a positive impact on mental health outcomes with a reduction in depression and anxiety compared with those who continue to smoke.74 Patients prescribed varenicline were reported to have an approximately threefold increased chance of quitting smoking compared with those given placebo (odds ratio 2.88, 95% confidence interval 2.40 to 3.47)4; this could explain the reduction in anxiety observed in this meta-analysis.

Lastly, half of the trials were sponsored by Pfizer, the manufacturers of varenicline. Although previous research with nicotine replacement therapy has shown that industry sponsored trials were more likely than other trials to report outcomes that were favourable to the study sponsor,14 we did not find any evidence for differences in depression and suicidal ideation for industry versus non industry sponsored trials (P=0.386 and P=0.380, respectively, for interaction). In addition, all of the industry sponsored trials were assessed overall as having a low risk of bias.

Conclusions and clinical implications

Based on this comprehensive systematic review of published randomised controlled trials, there is no evidence of an increased risk of depression, suicidal behaviour (that is, suicide or attempted suicide, suicidal ideation), and death from any cause associated with treatment with varenicline. Varenicline users, however, have an increased risk of abnormal dreams, insomnia, and sleep disturbances, which are consistent with findings from other studies and previously documented commonly reported side effects of varenicline (www.chantix.com). We reported our findings using two summary statistics (a relative measure and an absolute measure) and observed consistency with both methods. This meta-analysis adds to previous research (observational and experimental) that found no evidence for increased suicidal behaviour or depression with varenicline, the most effective drug for smoking cessation.4 The dangers of smoking are well documented, and the health benefits of stopping smoking are well known. Our analysis suggests that the benefits of varenicline for smoking cessation outweigh the as yet unproved risks of suicidal behaviour. In the UK, varenicline is recommended alongside bupropion and nicotine replacement therapy as first line treatment for smoking cessation.75 Therefore, the reduction in varenicline prescribing in the UK should be as much a cause for concern to clinicians, regulatory agencies, and policy makers as the unfounded fears regarding varenicline’s association with suicidal behaviour.

What is already known on this topic

Varenicline is a commonly prescribed and effective drug for smoking cessation. The Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have issued safety warnings regarding suicidal thoughts and depression associated with the use of varenicline, based on reports from spontaneous reporting systems

Evidence from previous observational cohort studies and a meta-analysis of 17 trials sponsored by Pfizer have found no evidence of an association with suicide, non-fatal self harm, or depression

Concerns have been raised about the validity of these findings as observational studies are prone to confounding and industry sponsored trials are more likely than other trials to report outcomes that are favourable to the study sponsor

What this paper adds

Our meta-analysis of all published randomised controlled trials is the most comprehensive meta-analysis of neuropsychiatric adverse events associated with varenicline use to date, and reports effects using two summary statistics, a relative measure (Peto odds ratio) and an absolute measure (risk difference)

There was no evidence of an increased risk of suicide or attempted suicide, suicidal ideation, depression, or death in varenicline users compared with placebo users

Varenicline was associated with an increased risk of sleep disorders, insomnia, and abnormal dreams, side effects that are already well recognised and included in patient information leaflets for varenicline

We are grateful to the corresponding authors of the trials and Cristina Russ of Pfizer (for the Pfizer sponsored trials) for their support with providing access to the data on psychiatric adverse events and death used in this study.

Contributors: KHT, DG and RMM conceived the study. KHT conducted the literature search. KHT and DWK screened the abstracts with assistance from DG. KHT, DG and RMM were responsible for data extraction and the risk of bias assessment. KHT did the statistical analysis with support from JPH. KHT wrote the paper with contributions from all authors. All authors have approved the final draft of the manuscript. KHT is study guarantor, had full access to all of the data (including statistical reports and tables) and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: KHT is currently funded by a clinical lectureship from the National Institute for Health Research. Part of this work was undertaken while KHT was on a National Institute for Health Research doctoral research fellowship (DRF-2010-03-138). DWK is funded by a Wellcome Trust four year studentship (WT099874MA). DG is an NIHR senior investigator. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research, or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: RMM had specified relationship with the MHRA in the past (was a member of the MHRA’s Independent Scientific Advisory Committee for CPRD research and received expenses and a small fee for meeting attendance and preparation for meetings). DG had specified relationship with the MHRA in the past (was a member of the MHRA’s Pharmacovigilance Expert Advisory Group and received travel expenses and a small fee for meeting attendance and preparation for meetings).

Ethics approval: Not required.

Data sharing: No additional data are available.

Transparency declaration: KHT affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Cite this as: BMJ 2015;350:h1109

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Appendix 1: Search strategy to identify relevant articles in Medline

Appendix 2: Further characteristics of included randomised controlled trials

Appendix 3: Forest plots for secondary outcomes

Appendix 4: Subgroup analyses

Appendix 5: Funnel plots

Appendix 6: Summary of Peto odds ratios, risk differences, and 95% confidence intervals for neuropsychiatric events

References

- 1.Peto R, Darby S, Deo H, Silcocks P, Whitley E, Doll R. Smoking, smoking cessation, and lung cancer in the UK since 1950: combination of national statistics with two case-control studies. BMJ 2000;321:323-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jha P, Peto R. Global effects of smoking, of quitting, and of taxing tobacco. N Engl J Med 2014;370:60-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allender S, Balakrishnan R, Scarborough P, Webster P, Rayner M. The burden of smoking-related ill health in the UK. Tob Control 2009;18:262-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cahill K, Stevens S, Perera R, Lancaster T. Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation: an overview and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;5:CD009329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Varenicline: adverse psychiatric reactions, including depression. Drug Safety Update 2008;2:2-3. [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Food and Drug Administration. Information for healthcare professionals: varenicline (marketed as Chantix) and bupropion (marketed as Zyban, Wellbutrin and generics). FDA Drug Safety Newsletter, 2009.

- 7.Gunnell D, Irvine D, Wise L, Davies C, Martin RM. Varenicline and suicidal behaviour: a cohort study based on data from the General Practice Research Database. BMJ 2009;339;b3805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Meyer TE, Taylor LG, Xie S, Graham DJ, Mosholder AD, Williams JR, et al. Neuropsychiatric events in varenicline and nicotine replacement patch users in the Military Health System. Addiction 2013;108:203-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas KH, Martin RM, Davies N, Metcalfe C, Windmeijer F, Gunnell D. Smoking cessation treatment and the risk of depression, suicide and self-harm in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink: prospective cohort study BMJ 2013;347:f5704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gibbons RD, Mann JJ. Varenicline, smoking cessation, and neuropsychiatric adverse events. Am J Psychiatry 2013;170:1460-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker AM. Confounding by indication. Epidemiology 1996;7:335-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller M, Hemenway D, Bell NS, Yore MM, Amoroso PJ. Cigarette smoking and suicide: a prospective study of 300,000 male active-duty Army soldiers. Am J Epidemiol 2000;151:1060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller M, Hemenway D, Rimm E. Cigarettes and suicide: a prospective study of 50,000 men. Am J Public Health 2000;90:768-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Etter JF, Burri M, Stapleton J. The impact of pharmaceutical company funding on results of randomized trials of nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. Addiction 2007;102:815-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prescribing and Primary Care team Health and Social Care Information Centre. Prescription cost analysis, England, 2013. Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2014.

- 16.Cahill K, Stead LF, Lancaster T. Nicotine receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;4:CD006103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JPT, Altman DG. Assessing risk of bias in included studies. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. John Wiley, 2008:187-241.

- 18.Harris R, Bradburn M, Deeks J, Harbord R, Altman D, Sterne J. metan: fixed- and random-effects meta-analysis. Stata J 2008;8:3-28. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bradburn MJ, Deeks JJ, Berlin JA, Russell Localio A. Much ado about nothing: a comparison of the performance of meta-analytical methods with rare events. Stat Med 2007;26:53-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Special topics in statistics. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. John Wiley, 2008:481-529.

- 22.Sterne JAC, Harbord RM. Funnel plots in meta-analysis. Stata J 2004;4:127-41. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harbord RM, Harris RJ, Sterne JAC. Updated tests for small-study effects in meta-analyses. Stata J 2009;9:197-210. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anthenelli RM, Morris C, Ramey TS, Dubrava SJ, Tsilkos K, Russ C, et al. Effects of varenicline on smoking cessation in adults with stably treated current or past major depression: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2013;159:390-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bolliger CT, Issa JS, Posadas-Valay R, Safwat T, Abreu P, Correia EA, et al. Effects of varenicline in adult smokers: a multinational, 24-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin Ther 2011;33:465-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brandon TH, Drobes DJ, Unrod M, Heckman BW, Oliver JA, Roetzheim RC, et al. Varenicline effects on craving, cue reactivity, and smoking reward. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;218:391-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burstein AH, Fullerton T, Clark DJ, Faessel HM. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability after single and multiple oral doses of varenicline in elderly smokers. J Clin Pharmacol 2006;46:1234-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cinciripini PM, Robinson JD, Karam-Hage M, Minnix JA, Lam C, Versace F, et al. Effects of varenicline and bupropion sustained-release use plus intensive smoking cessation counseling on prolonged abstinence from smoking and on depression, negative affect, and other symptoms of nicotine withdrawal. JAMA Psychiatry 2013;70:522-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ebbert JO, Croghan IT, Severson HH, Schroeder DR, Hays JT. A pilot study of the efficacy of varenicline for the treatment of smokeless tobacco users in Midwestern United States. Nicotine Tob Res 2011;13:820-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evins AE, Cather C, Pratt SA, Pachas GN, Hoeppner SS, Goff DC, et al. Maintenance treatment with varenicline for smoking cessation in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;311:145-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Faessel H, Ravva P, Williams K. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of varenicline in healthy adolescent smokers: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Clin Ther 2009;31:177-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fagerstrom K, Gilljam H, Metcalfe M, Tonstad S, Messig M. Stopping smokeless tobacco with varenicline: randomised double blind placebo controlled trial. BMJ 2010;341:c6549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fatemi SH, Yousefi MK, Kneeland RE, Liesch SB, Folsom TD, Thuras PD. Antismoking and potential antipsychotic effects of varenicline in subjects with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder: a double-blind placebo and bupropion-controlled study. Schizophr Res 2013;146:376-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garza D, Murphy M, Tseng LJ, Riordan HJ, Chatterjee A. A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled pilot study of neuropsychiatric adverse events in abstinent smokers treated with varenicline or placebo. Biol Psychiatry 2011;69:1075-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gonzales D, Rennard SI, Nides M, Oncken C, Azoulay S, Billing CB, et al. Varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2006;296:47-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hughes JR, Rennard SI, Fingar JR, Talbot SK, Callas PW, Fagerstrom KO. Efficacy of varenicline to prompt quit attempts in smokers not currently trying to quit: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Nicotine Tob Res 2011;13:955-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jorenby DE, Hays JT, Rigotti NA, Azoulay S, Watsky EJ, Williams KE, et al. Efficacy of varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs placebo or sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2006;296:56-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Litten RZ, Ryan ML, Fertig JB, Falk DE, Johnson B, Dunn KE, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial assessing the efficacy of varenicline tartrate for alcohol dependence. J Addict Med 2013;7:277-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McClure EA, Vandrey RG, Johnson MW, Stitzer ML. Effects of varenicline on abstinence and smoking reward following a programmed lapse. Nicotine Tob Res 2013;15:139-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McKee SA, Harrison EL, O’Malley SS, Krishnan-Sarin S, Shi J, Tetrault JM, et al. Varenicline reduces alcohol self-administration in heavy-drinking smokers. Biol Psychiatry 2009;66:185-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meszaros ZS, Abdul-Malak Y, Dimmock JA, Wang D, Ajagbe TO, Batki SL. Varenicline treatment of concurrent alcohol and nicotine dependence in schizophrenia: a randomized, placebo-controlled pilot trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2013;33:243-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mitchell JM, Teague CH, Kayser AS, Bartlett SE, Fields HL. Varenicline decreases alcohol consumption in heavy-drinking smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;223:299-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakamura M, Oshima A, Fujimoto Y, Maruyama N, Ishibashi T, Reeves KR. Efficacy and tolerability of varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, in a 12-week, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose-response study with 40-week follow-up for smoking cessation in Japanese smokers. Clin Ther 2007;29:1040-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Niaura R, Hays JT, Jorenby DE, Leone FT, Pappas JE, Reeves KR, et al. The efficacy and safety of varenicline for smoking cessation using a flexible dosing strategy in adult smokers: a randomized controlled trial. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:1931-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nides M, Oncken C, Gonzales D, Rennard S, Watsky EJ, Anziano R, et al. Smoking cessation with varenicline, a selective alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist: results from a 7-week, randomized, placebo- and bupropion-controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1561-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oncken C, Gonzales D, Nides M, Rennard S, Watsky E, Billing CB, et al. Efficacy and safety of the novel selective nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, varenicline, for smoking cessation. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1571-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Plebani JG, Lynch KG, Yu Q, Pettinati HM, O’Brien CP, Kampman KM. Results of an initial clinical trial of varenicline for the treatment of cocaine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 2012;121:163-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Plebani JG, Lynch KG, Rennert L, Pettinati HM, O’Brien CP, Kampman KM. Results from a pilot clinical trial of varenicline for the treatment of alcohol dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;133:754-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poling J, Rounsaville B, Gonsai K, Severino K, Sofuoglu M. The safety and efficacy of varenicline in cocaine using smokers maintained on methadone: a pilot study. Am J Addict 2010;19:401-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rennard S, Hughes J, Cinciripini PM, Kralikova E, Raupach T, Arteaga C, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of varenicline for smoking cessation allowing flexible quit dates. Nicotine Tob Res 2012;14:343-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rigotti NA, Pipe AL, Benowitz NL, Arteaga C, Garza D, Tonstad S. Efficacy and safety of varenicline for smoking cessation in patients with cardiovascular disease: a randomized trial. Circulation 2010;121:221-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shim JC, Jung DU, Jung SS, Seo YS, Cho DM, Lee JH, et al. Adjunctive varenicline treatment with antipsychotic medications for cognitive impairments in people with schizophrenia: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 2012;37:660-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stein MD, Caviness CM, Kurth ME, Audet D, Olson J, Anderson BJ. Varenicline for smoking cessation among methadone-maintained smokers: a randomized clinical trial. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;133:486-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Steinberg MB, Randall J, Greenhaus S, Schmelzer AC, Richardson DL, Carson JL. Tobacco dependence treatment for hospitalized smokers: a randomized, controlled, pilot trial using varenicline. Addic Behav 2011;36:1127-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tashkin DP, Rennard S, Hays JT, Ma W, Lawrence D, Lee TC. Effects of varenicline on smoking cessation in patients with mild to moderate COPD: a randomized controlled trial. Chest 2011;139:591-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tonnesen P, Mikkelsen K. Varenicline to stop long-term nicotine replacement use: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Nicotine Tob Res 2013;15:419-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tonstad S, Tonnesen P, Hajek P, Williams KE, Billing CB, Reeves KR, et al. Effect of maintenance therapy with varenicline on smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2006;296:64-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsai ST, Cho HJ, Cheng HS, Kim CH, Hsueh KC, Billing CB, Jr., et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of varenicline, a selective alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, as a new therapy for smoking cessation in Asian smokers. Clin Ther 2007;29:1027-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang C, Xiao D, Chan KPW, Pothirat C, Garza D, Davies S. Varenicline for smoking cessation: A placebo-controlled, randomized study. Respirology 2009;14:384-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weiner E, Buchholz A, Coffay A, Liu F, McMahon RP, Buchanan RW, et al. Varenicline for smoking cessation in people with schizophrenia: a double blind randomized pilot study. Schizophr Res 2011;129:94-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Williams K, Reeves K, Billing C, Pennington A, Gong J. A double-blind study evaluating the long-term safety of varenicline for smoking cessation. Curr Med Res Opin 2007;23:793-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Williams JM, Anthenelli RM, Morris CD, Treadow J, Thompson JR, Yunis C, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating the safety and efficacy of varenicline for smoking cessation in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2012;73:654-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wong J, Abrishami A, Yang Y, Zaki A, Friedman Z, Selby P, et al. A perioperative smoking cessation intervention with varenicline: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Anesthesiology 2012;117:755-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zesiewicz TA, Greenstein PE, Sullivan KL, Wecker L, Miller A, Jahan I, et al. A randomized trial of varenicline (Chantix) for the treatment of spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. Neurology 2012;78:545-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhao Q, Schwam E, Fullerton T, O’Gorman M, Burstein AH. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability following multiple oral doses of varenicline under various titration schedules in elderly nonsmokers. J Clin Pharmacol 2011;51:492-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chengappa KN, Perkins KA, Brar JS, Schlicht PJ, Turkin SR, Hetrick ML, et al. Varenicline for smoking cessation in bipolar disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry 2014;75:765-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gonzales D, Hajek P, Pliamm L, Nackaerts K, Tseng LJ, McRae TD, et al. Retreatment with varenicline for smoking cessation in smokers who have previously taken varenicline: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2014;96:390-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kishi T, Iwata N. Varenicline for smoking cessation in people with schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2014. Oct 5 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Hong LE, Thaker GK, McMahon RP, Summerfelt A, Rachbeisel J, Fuller RL, et al. Effects of moderate-dose treatment with varenicline on neurobiological and cognitive biomarkers in smokers and nonsmokers with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011;68:1195-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang Y, Li W, Yang L, Jiang Y, Wu Y. Long-term efficacy and safety of varenicline for smoking cessation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Public Health 2012;20:355-65. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Singh S, Loke YK, Spangler JG, Furberg CD. Risk of serious adverse cardiovascular events associated with varenicline: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2011;183:1359-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Prochaska JJ, Hilton JF. Risk of cardiovascular serious adverse events associated with varenicline use for tobacco cessation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2012;344:e2856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mocking RJ, Patrick Pflanz C, Pringle A, Parsons E, McTavish SF, Cowen PJ, et al. Effects of short-term varenicline administration on emotional and cognitive processing in healthy, non-smoking adults: a randomized, double-blind, study. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013;38:476-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Taylor G, McNeill A, Girling A, Farley A, Lindson-Hawley N, Aveyard P. Change in mental health after smoking cessation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2014;348:g1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Smoking cessation services in primary care, pharmacies, local authorities and workplaces, particularly for manual working groups, pregnant women and hard to reach communities. NICE public health guidance 10. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2008.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1: Search strategy to identify relevant articles in Medline

Appendix 2: Further characteristics of included randomised controlled trials

Appendix 3: Forest plots for secondary outcomes

Appendix 4: Subgroup analyses

Appendix 5: Funnel plots

Appendix 6: Summary of Peto odds ratios, risk differences, and 95% confidence intervals for neuropsychiatric events