Abstract

As part of continuing studies of the identification of gene organization and cloning of novel α-conotoxins, the first α4/4-conotoxin identified in a vermivorous Conus species, designated Qc1.2, was originally obtained by cDNA and genomic DNA cloning from Conus quercinus collected in the South China Sea. The predicted mature toxin of Qc1.2 contains 14 amino acid residues with two disulfide bonds (I-III, II-IV connectivity) in a native globular configuration. The mature peptide of Qc1.2 is supposed to contain an N-terminal post-translationally processed pyroglutamate residue and a free carboxyl C-terminus. This peptide was chemically synthesized and refolded for further characterization of its functional properties. The synthetic Qc1.2 has two interconvertible conformations in aqueous solution, which may be due to the cis-trans isomerization of the two successive Pro residues in its first Cys loop. Using the Xenopus oocyte heterologous expression system, Qc1.2 was shown to selectively inhibit both rat neuronal α3β2 and α3β4 subtypes of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors with low potency. A block of ∼63% and 37% of the ACh-evoked currents was observed, respectively, and the toxin dissociated rapidly from the receptors. Compared with other characterized α-conotoxin members, the unusual structural features in Qc1.2 that confer to its receptor recognition profile are addressed.

Keywords: nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtype, α4/4-conotoxin, post-translational modification, Xenopus oocyte

Introduction

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) are pentameric ligand-gated cationic channels that belong to the Cys-loop receptor superfamily which includes GABAA, glycine, and 5HT3 neurotransmitter receptors [1]. nAChRs are present at the neuromuscular junction to cause muscle contraction, in sympathetic and parasympathetic ganglia to mediate neurotransmission, and in the brain to modulate neurotransmitter release [1]. To date, they represent one of the most intensively investigated membrane proteins by biochemical, molecular biological, electrophysiological, and pharmacological approaches. Muscular nAChR in vertebrate is composed of four homologous subunits around the central ion-conducting channel in a heteropentameric structure, with either the embryonic subtype α1β1γδ or the adult α1β1ϵδ. As 11 nAChR subunits (α2-α7, α9, α10, β2-β4) have been cloned from neuronal and sensory mammalian tissues, the subunit assembly of different neuronal nAChRs largely determines distinct physiological and pharmacological properties of the channel [1].

nAChRs appear to be involved in attention, memory, learning, development, antinociception, nicotine addiction, neurological disorders such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's diseases, Tourette's syndrome, certain forms of epilepsy, and schizophrenia [2–4]. Thus, development of selective nAChR modulators is needed for discrimination between the combinatorial diversity of subtypes and medication.

The genus Conus is a group of venomous predatory snails inhabited in tropical water, which prey upon a broad diversity of organisms (five different phyla), including fish, other mollusks, and worms [5]. These hunting gastropods are evolutionarily the most successful marine invertebrates. The venom of each of the ∼700 species contains 50–200 bioactive small peptides that act at many ligand- and voltage-gated ion channels, receptors, and transporters, with most of which are disulfide-rich toxins (conotoxins) [6]. They could be classified into different superfamilies according to the highly conserved signal sequence in their precursors and further grouped into individual pharmacological families. α-conotoxins belong to the A-superfamily and are proven to be competitive antagonists of a plethora of nAChRs, which makes them valuable tools for elucidating different nAChRs and candidates for developing subtype specific drugs.

Based on the number of amino acid residues encompassed by the second and third cysteine residues and the third and fourth cysteine residues, α-conotoxins can be divided into several structural subfamilies, α3/5, α4/3, α4/4, α4/5, α4/6, and α4/7. The α3/5 subfamily mostly blocks the fetal muscular nAChRs, except for α-GI that inhibits the adult subtype, whereas the neuronally active α-conotoxins are typically from the α4/3, α4/6, and α4/7 subfamilies. However, two exceptions have been found in the most abundant α4/7 subfamily: EI which antagonizes the neuromuscular subtype [7]; SrIA and SrIB that potentiate the receptor activity [8]. Unlike other subfamilies, α4/4-conotoxins (Table 1) are active against a broad spectrum of nAChR subtypes: BuIA has been characterized as potent antagonists at neuronal α6/α3β2, α3β2, and α3β4 subtypes [5], whereas PIB is highly selective for muscle nAChRs indicated with IC50 values of 45 nM and 36 nM for fetal and adult subtypes, respectively [9]. Thus, it is tempting to further investigate this group of peptides with unusual structure and function.

Table 1.

Physical-chemical characteristics and biological activities of α4/4-conotoxins identified from piscivorous (p) and vermivorous (v) Conus species

| Peptide | Sequence | Species | Prey | Selectivity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BuIA | GCCSTPPCAVLYC* | C. bullatus | p | α6/α3(β4/β2) | [5] |

| PIB | ZSOGCCWNPACVKNRC* | C. purpurascens | p | α1β1δ(γ/ϵ) | [9] |

| S1.1 | GCCRNPACESHRC* | C. striatus | p | N/A | [26] |

| Qc1.2 | ZCCANPPCKHVNCR | C. quercinus | v | α3β2, α3β4 | This work |

Conserved cysteine residues are highlighted in bold-face. For post-translational modifications: Z, pyroglutamic acid; O, hydroxyproline; N/A, not available. *amidated C-terminus.

We previously obtained the first α4/4-conotoxin from a worm-hunting species Conus quercinus, Qc1.2, by molecular cloning [10]. This toxin is predicted to have an N-terminal pyroglutamate and a free carboxyl C-terminus. In this work, we chemically and functionally characterize α4/4-Qc1.2 by total synthesis, in vitro refolding and electrophysiology recording. The result will improve the understanding of this relatively undercharacterized group of α-conotoxins and thus facilitate the rational design of more potent and selective drug molecules.

Materials and Methods

Materials

ZORBAX 300SB-C18 semi-preparative column was purchased from Agilent Technologies (Santa Clara, USA). PepMap-C18 analytical column is from LC Packings (Sunnyvale, USA). Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and acetonitrile (ACN) for HPLC were from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Other reagents were of analytical grade.

Peptide synthesis and folding

Linear peptide α-Qc1.2 (ZCCANPPCKHVNCR) was assembled on resin by solid-phase method, using Fmoc [N-(9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl)] chemistry and standard side-chain protection [11]. Peptide synthesis was performed on an ABI 433A peptide synthesizer (ABI, Foster City, USA) by GL Biochem (Shanghai) Ltd (Shanghai, China). Cys residues were protected with the stable S-acetamidomethyl on Cys2 and Cys8; Cys3 and Cys13 were protected as the acid-labile Cys (S-trityl). The peptide was removed from the resin by treatment with TFA/H2O/ethanedithiol/phenol/thioanisole, immediately precipitated and the solution was centrifuged to separate the pellet, which was washed several times with cold methyl-t-butyl ether. Side chains of non-Cys residues were de-protected during the cleavage. Pyroglutamate was not protected with Fmoc so that further de-protection was not necessary. The crude peptide was then purified by HPLC on a ZORBAX 300SB-C18 semi-preparative column (9.4 mm× 250 mm) and characterized by electrospray-mass spectrometry (ESI-MS). The product was lyophilized and dissolved in 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 8.7).

A two-step oxidation protocol was used to selectively fold the peptide to its natural global disulfide isomer as described previously [12]. Briefly, the disulfide bridge between Cys3 and Cys13 was closed by air oxidation. The linear peptide was stirred at 4°C and the monocyclic peptide was purified by reverse-phase HPLC on a semi-preparative C18 column. Simultaneous removal of the S-acetamidomethyl groups and formation of the disulfide bridge between Cys2 and Cys8 was carried out by iodine oxidation in 5 mM iodine in H2O/TFA/ACN (86:4:10 by volume). The solution was stirred at room temperature for 1 h and the reaction was quenched by the addition of 1% ascorbic acid. The predominant form of the bicyclic peptide was purified to homogeneity, using a reverse-phase semi-preparative C18 column. The final product was applied to a PepMap analytical C18 column (4.6 mm× 250 mm; flow rate = 0.5 ml/min) to verify its purity, using a 15–27% linear gradient of ACN in 0.1% TFA and water for 24 min. The mass of the folded peptide analyzed by ESI-MS was consistent with the predicated sequence (average mass: calculated 1551.8; observed 1552.0).

Voltage clamp recording

Oocytes of Xenopus laevis frogs were prepared and injected with capped RNA to elicit expression of mouse fetal skeletal-muscle and various rat neuronal nAChR subtypes as described previously in detail [12–16].

All two-electrode voltage clamp recordings of Xenopus oocyte nAChR currents were conducted at room temperature on an OC-725C amplifier (Warner Instruments, Hamden, USA). Oocytes were placed in a 300 µl-volume Warner RC-3Z recording chamber attached with an OC-725 bath clamp. Glass microelectrodes with the resistance between 0.05 and 0.2 MΩ were filled with 3 M KCl. Oocytes were voltage clamped at a membrane potential of −60 mV and gravity-perfused with OR2 buffer at a rate of ∼5 ml/min by use of a Warner BPS-8 controller [17]. One micromolar atropine was added to OR2 buffer to block endogenous muscarinic AChRs for the recordings of all nAChRs, with the exception of α7 nAChR, which atropine antagonizes [18]. ACh-gated currents were elicited by a 5-s pulse of agonist solution applied at intervals of 2 min to obtain the baseline activity: 10 µM ACh for the muscle subtype and 100 µM ACh for the neuronal subtypes. To identify the effect of the peptide, a predetermined concentration of Qc1.2 was applied to an oocyte in the static bath for 10 min to reach equilibrium with a particular receptor subtype prior to restoration of OR2 perfusion and ACh pulse. The current signals were sampled and filtered at 500 and 200 Hz, respectively. The average peak amplitude of three control responses preceding exposure to toxin was used to normalize the amplitude of each test response to obtain ‘% response' and recovery from the toxin application. All data were represented as arithmetic mean ± SD from measurements of 3–5 oocytes for each subtype.

Results

Chemical synthesis of α-Qc1.2

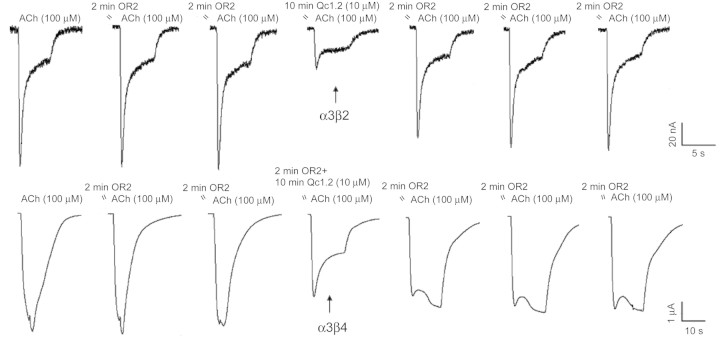

We previously utilized the highly conserved features of the α-conotoxin gene structure, i.e. the signal sequence, the intron immediately preceding the toxin sequence and the 3′-untranslated region, to design oligonucleotide primers for PCR amplification of the α-conotoxin coding region [10]. The analysis of the nucleic acid sequences derived from DNA clones from C. quercinus has revealed a novel α4/4-conotoxin Qc1.2, according to the nomenclature convention of conopeptides [19]. Similar to other known α-conotoxins, Qc1.2 is proteolytically processed from a 62-amino acid precursor to the mature moiety of 14 amino acids located at the C-terminus of the prepropeptide (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The cDNA sequence and predicted translation product of Qc1.2 The signal sequence and mature toxin are in shadow. The conserved Cys codons are in bold. The nucleotide sequence data is available in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under the accession numbers DQ311067 and AY580320 for Qc1.2.

To investigate functional properties of Qc1.2, the first α4/4-conotoxin identified from a vermivorous Conus species, the solid-phase synthesis strategy was undertaken. The N-terminal glutamine residue of this predicted 14-residue peptide is supposed to be post-translationally modified to pyroglutamate, as all glutamines at the termini of Conus peptides so far have been found as pyroglutamate after proteolysis, i.e. α4/4-PIB [9], µ-SmIIIA, SIIIA, and PIIIA [11]. It was assumed that the disulfide connectivity of α-Qc1.2 (Cys2 to Cys8 and Cys3 to Cys13) was the same as that of all previously characterized natural α-conotoxins. Orthogonal protection of Cys groups was used to direct disulfide bond formation in this globular configuration.

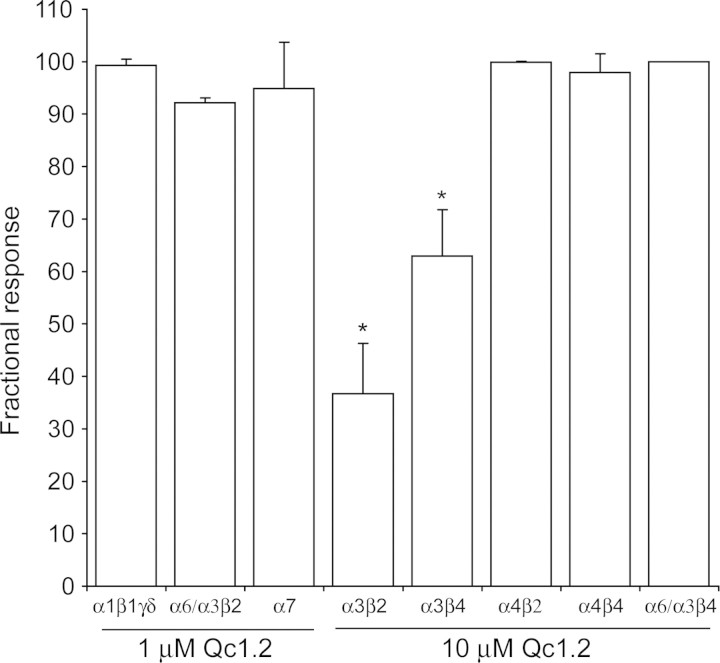

The final folded toxin was purified on semi-preparative HPLC and the elution profile displayed two peaks with the same molecular weight (Fig. 2). The minor peak could not be eliminated by optimizing the oxidation condition. Interestingly, re-load of either the major or the minor peak could also obtain both two peaks in the same ratio (data not shown), suggesting that each represents a distinct conformation in solution that could transit from each other.

Figure 2.

HPLC (A) and MS (B) analysis of the oxidative folding of Qc1.2 The major oxidation product, marked by the asterisk, was purified and used for further characterization. In (A), Qc1.2 was loaded onto a PepMap C18 analytical column in 90% buffer A and eluted with a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min using the following gradient: 0–5 min, 10–15% buffer B; 5–29 min, 15–27% buffer B; 29–31 min, 27–100% buffer B. Buffer A, 0.1% TFA; buffer B, 0.1% TFA in 100% ACN. Absorbance was measured at 214 nm. MS measurement of the purified peptide was performed by ESI-MS on a Q-trap mass spectrometer gave an average mass 1552.0 (calculated mass 1551.8).

Effects of α-Qc1.2 on oocyte-expressed nAChR subtypes

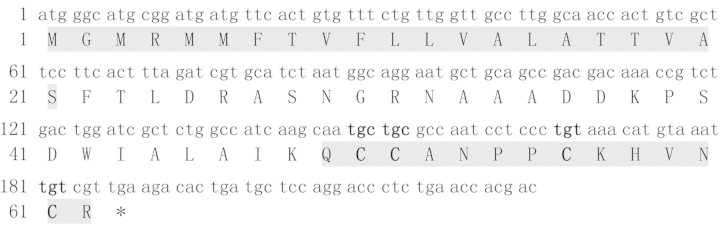

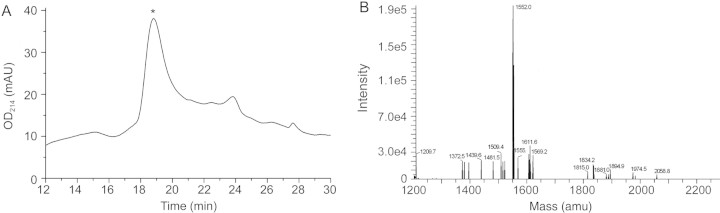

α-Qc1.2 was tested for effects on ACh-evoked currents in Xenopus oocytes expressing the mouse fetal skeletal-muscle and various rat neuronal nAChR subunit combinations (Fig. 3). To our surprise, the positively charged Qc1.2 weakly and reversibly inhibited recombinant α3β2 and α3β4 subunits, as it was previously demonstrated that α-conotoxins specific for neuronal subtypes of nAChRs are neutral or negatively charged, whereas α-conotoxins that target muscle receptors have a net positive charge (data not shown) [20]. Qc1.2 (1 µM) had little effect on the mouse fetal muscle (α1β1γδ), rat neuronal α7 and α6/α3β2 nAChR subtypes. At 10 µM, Qc1.2 blocked ∼63% of the ACh-elicited currents in α3β2 nAChR and ∼37% of the ACh-elicited current of α3β4 (Fig. 3), but exhibited no inhibition on other neuronal receptor subtypes tested (Fig. 4). The selectivity of Qc1.2 on α3β2 and α3β4 nAChRs over the α4β2 subtype (P < 0.01) indicated that the α3 nAChR subunit had an important influence on the effects of Qc1.2.

Figure 3.

Representative current traces for α-Qc1.2 at 10 µM on the rat α3β2 and α3β4 nAChRs, respectively Control traces are shown prior to the application of peptide. The arrow marks the first current trace elicited after a 10-min application of peptide. Subsequent current traces show peptide dissociation and washout.

Figure 4.

Qc1.2 is selective for rat neuronal α3β2 nAChR Each bar indicates the average percent response (±SD) after the application of 1 µM or 10 µM Qc1.2 to Xenopus oocytes expressing a variety of nAChRs. To determine the average percent response, the peptide was tested against each receptor subtype on 3–5 oocytes. In contrast to the low nanomolar affinity of other α-conotoxins for a certain nAChR subtype, Qc1.2 demonstrated more than 10 µM IC50 values for most of the receptors tested. *P < 0.01 vs. α4β2.

Discussion

Nowadays, the identification of novel conotoxin sequences largely depends on the PCR-based strategies, which include amplification of cDNAs from venom duct or genomic DNA from other cone snail tissues. Compared with conventional venom fractionation and function-based assay, the molecular biology approach advantages in not only economizing the required amounts of tissue but also detecting lowly expressed conopeptides [1]. Here, we describe the chemical synthesis and functional characterization of the first α4/4-conotoxin identified from a vermivorous Conus species, Qc1.2, obtained by molecular cloning.

Despite that the disulfide-constrained α-conotoxins are considered to have rigid structures, the folded toxin resides in two interconvertible conformations in solution that could result from the cis-trans isomerization of the two successive Pro residues in its first loop. Previous results suggested that some α3/5-conotoxins also exhibit asymmetric elution peaks on HPLC following oxidation, and have two conformations in aqueous condition [13,21–23], which differ in the second Cys loop and peptide termini region [23]. It would be difficult to determine which conformer is more favorable for peptide activity on nAChRs. Thus, only the major-eluting peak of the synthetic α-Qc1.2 was subjected to the subsequent functional experiment.

The C-terminus of Qc1.2 is supposed in this work to be the Arg residue with free carboxyl group, since this Arg residue is not preceded by Gly, which is believed to be the cleavage signal and amidation donor. However, the cleavage of the single basic residue at the most C-terminus has also been found in several cases [24]. The identification of natural Qc1.2 toxin would be needed to clarify this point.

To date, only four α-conotoxins with the unusual 4/4 disulfide scaffold have been identified (Table 1). Except for Qc1.2, the other three members are all from fish-eating species, with two of which have been characterized [5,9]. The functional determination of α4/4-Qc1.2 indicated that it is an inhibitor of neuronal α3β2 and α3β4 nAChRs, like α4/4-BuIA. Because of the similarity in the receptor recognition profile, Qc1.2 may also have a ‘pseudo ω-shaped' molecular topology and a two-turn helix motif revealed in the high-resolution three-dimensional structure of BuIA [25], of which the second helical turn portion might be critical for binding to the α3 subunit of nAChRs. However, in contrast to the strong antagonistic activity of BuIA, Qc1.2 only exhibited weak inhibitory action at α3β2 and α3β4 subtypes. Qc1.2 may act synergistically with other functionally related groups of peptides to block neurotransmission for prey capture, predator defense, and competitor deterrence.

Because the inhibitory activity found in functional assays of Qc1.2 is at rat α3β2 and α3β4 nAChRs, these receptors probably resemble a preferential target for both prey capture of worm and defense against a diversity of invertebrate and vertebrate predators. However, as it could be the case that one toxin is more effective at a particular predatory or defense target than another [1], the affinity and receptor subtype selectivity of Qc1.2 might vary widely among different species such as molluscan, Torpedo, avian, or human nAChRs.

In conclusion, we described the physical-chemical and functional characterization of α4/4-conotoxin Qc1.2, a selective antagonist of mammalian neuronal α3β2 and α3β4 nAChR subtypes with low potency. This toxin molecule has a unique primary sequence with unusual post-translational modification profile and has two interconvertible conformations in solution that could result from the cis-trans isomerization of the two successive Pro residues in its first cysteine loop. Qc1.2 is the first bioactive peptide component investigated in C. quercinus, which opens up a possibility to detect more novel ligands for nAChRs from this unique Conus species inhabited in the South China Sea. Our study will provide the basis for future exploration on the structure-function relationship and acting mechanism of Qc1.2.

Funding

This work was supported by the grants from National Basic Research Program of China (2004CB719904), the Chinese Academy of Sciences for Key Topics in Innovation Engineering (KSCX2-YW-R-104), the Program for Young Excellent Talents in Tongji University (2006KJ063), and Dawn Program of Shanghai Education Commission (06SG26).

References

- 1.Nicke A, Wonnacott S, Lewis RJ. α-conotoxins as tools for the elucidation of structure and function of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:2305–2319. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones S, Sudweeks S, Yakel JL. Nicotinic receptors in the brain: correlating physiology with function. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:555–561. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01471-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindstrom J. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in health and disease. Mol Neurobiol. 1997;15:193–222. doi: 10.1007/BF02740634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lloyd GK, Williams M. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as novel drug targets. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;292:461–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azam L, Dowell C, Watkins M, Stitzel JA, Olivera BM, McIntosh JM. α-conotoxin BuIA, a novel peptide from Conus bullatus, distinguishes among neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:80–87. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406281200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craik DJ, Adams DJ. Chemical modification of conotoxins to improve stability and activity. ACS Chem Biol. 2007;2:457–468. doi: 10.1021/cb700091j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinez JS, Olivera BM, Gray WR, Craig AG, Groebe DR, Abramson SN, McIntosh JM. α-Conotoxin EI, a new nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist with novel selectivity. Biochemistry. 1995;34:14519–14526. doi: 10.1021/bi00044a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.López-Vera E, Aguilar MB, Schiavon E, Marinzi C, Ortiz E, Restano Cassulini R, Batista CV, et al. Novel α-conotoxins from Conus spurius and the α-conotoxin EI share high-affinity potentiation and low-affinity inhibition of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. FEBS J. 2007;274:3972–3985. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.López-Vera E, Jacobsen RB, Ellison M, Olivera BM, Teichert RW. A novel α-conotoxin (α-PIB) isolated from C. purpurascens is selective for skeletal muscle nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Toxicon. 2007;49:1193–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan DD, Han YH, Wang CG, Chi CW. From the identification of gene organization of α-conotoxins to the cloning of novel toxins. Toxicon. 2007;49:1135–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shon KJ, Olivera BM, Watkins M, Jacobsen RB, Gray WR, Floresca CZ, Cruz LJ, et al. μ-Conotoxin PIIIA, a new peptide for discriminating among tetrodotoxin-sensitive Na channel subtypes. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4473–4481. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-12-04473.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peng C, Han Y, Sanders T, Chew G, Liu J, Hawrot E, Chi C, et al. α4/7-conotoxin Lp1.1 is a novel antagonist of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Peptides. 2008;29:1700–1707. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu L, Chew G, Hawrot E, Chi C, Wang C. Two potent α3/5 conotoxins from piscivorous Conus achatinus. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin. 2007;39:438–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2007.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenthal JA, Levandoski MM, Chang B, Potts JF, Shi QL, Hawrot E. The functional role of positively charged amino acid side chains in α-bungarotoxin revealed by site-directed mutagenesis of a His-tagged recombinant α-bungarotoxin. Biochemistry. 1999;38:7847–7855. doi: 10.1021/bi990045g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levandoski MM, Lin Y, Moise L, McLaughlin JT, Cooper E, Hawrot E. Chimeric analysis of a neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor reveals amino acids conferring sensitivity to α-bungarotoxin. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26113–26119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nutt LK, Margolis SS, Jensen M, Herman CE, Dunphy WG, Rathmell JC, Kornbluth S. Metabolic regulation of oocyte cell death through the CaMKII-mediated phosphorylation of caspase-2. Cell. 2005;123:89–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanders T, Hawrot E. A novel pharmatope tag inserted into the β4 subunit confers allosteric modulation to neuronal nicotinic receptors. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51460–51465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409533200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerzanich V, Anand R, Lindstrom J. Homomers of α8 and α7 subunits of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors exhibit similar channel but contrasting binding site properties. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:212–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loughnan ML, Alewood PF. Physico-chemical characterization and synthesis of neuronally active α-conotoxins. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:2294–2304. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang TS, Radić Z, Talley TT, Jois SD, Taylor P, Kini RM. Protein folding determinants: structural features determining alternative disulfide pairing in α- and χ/λ-conotoxins. Biochemistry. 2007;46:3338–3355. doi: 10.1021/bi061969o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Favreau P, Krimm I, Le Gall F, Bobenrieth MJ, Lamthanh H, Bouet F, Servent D, et al. Biochemical characterization and nuclear magnetic resonance structure of novel α-conotoxins isolated from the venom of Conus consors. Biochemistry. 1999;38:6317–6326. doi: 10.1021/bi982817z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gray WR, Rivier JE, Galyean R, Cruz LJ, Olivera BM, Conotoxin MI. Disulfide bonding and conformational states. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:12247–12251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maslennikov IV, Sobol AG, Gladky KV, Lugovskoy AA, Ostrovsky AG, Tsetlin VI, Ivanov VT, et al. Two distinct structures of α-conotoxin GI in aqueous solution. Eur J Biochem. 1998;254:238–247. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2540238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang CG, Cai Z, Lu W, Wu J, Xu Y, Shi Y, Chi CW. A novel short-chain peptide BmKX from the Chinese scorpion Buthus martensi karsch, sequencing, gene cloning and structure determination. Toxicon. 2005;45:309–319. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chi SW, Kim DH, Olivera BM, McIntosh JM, Han KH. NMR structure determination of α-conotoxin BuIA, a novel neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist with an unusual 4/4 disulfide scaffold. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;349:1228–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]