Abstract

Objectives. We examined the potential for glycemic control monitoring and screening for diabetes in a dental setting among adults (n = 408) with or at risk for diabetes.

Methods. In 2013 and 2014, we performed hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) tests on dried blood samples of gingival crevicular blood and compared these with paired “gold-standard” HbA1c tests with dried finger-stick blood samples in New York City dental clinic patients. We examined differences in sociodemographics and diabetes-related risk and health care characteristics for 3 groups of at-risk patients.

Results. About half of the study sample had elevated HbA1c values in the combined prediabetes and diabetes ranges, with approximately one fourth of those in the diabetes range. With a correlation of 0.991 between gingival crevicular and finger-stick blood HbA1c, measures of concurrence between the tests were extremely high for both elevated HbA1c and diabetes-range HbA1c levels. Persons already diagnosed with diabetes and undiagnosed persons aged 45 years or older could especially benefit from HbA1c testing at dental visits.

Conclusions. Gingival crevicular blood collected at the dental visit can be used to screen for diabetes and monitor glycemic control for many at-risk patients.

Although diabetes has reached epidemic proportions in the United States,1 many diabetes complications could be mitigated by early detection coupled with lifestyle modification and therapeutic interventions to optimize glycemic control.2 Unfortunately, 8.1 million of the 29.1 million persons in the United States who have diabetes are undiagnosed,3 and among those diagnosed with diabetes, many are not likely to have received regular testing to monitor their glycemic control.4 An additional 86 million US adults have prediabetes, a condition that often progresses to diabetes, but only 11.1% of these persons have been told of their condition.3 Importantly, early identification and treatment of prediabetes can interrupt its progression.5,6 Thus, more opportunities are needed to screen for prediabetes and diabetes and to monitor glycemic control in those already diagnosed.

Because many persons in the United States visit a dental provider but not a primary care provider (PCP) each year,7 the dental visit may serve as an opportune site for diabetes screening and monitoring blood glucose.8–10 However, both dental patients and dental providers are accustomed to having dental providers only administer care in the mouth. In an earlier pilot study, we therefore investigated and demonstrated the acceptability and feasibility of using oral blood to screen for diabetes in persons with bleeding on dental probing.11,12 Many patients appreciated the use of oral blood for this screening, indicating that its collection felt like a routine dental cleaning, and most dental providers felt that the oral blood collection was fast and easy.12

In the current study, we refined our examination of the use of oral blood to screen for diabetes by implementing a laboratory-based approach to diabetes testing that enabled definitive and accurate analysis of all of the samples for which sufficient blood was collected. We included a large sample of patients (n = 408) at risk for diabetes or its complications who presented for regular dental visits at a dental college’s comprehensive care clinics. We analyzed the sociodemographic and diabetes risk–related characteristics of the sample, and compared the results of diabetes screening and glycemic control monitoring with dried blood samples of gingival crevicular blood (GCB) and gold-standard finger-stick blood (FSB) to determine the validity of using GCB for this purpose. This screening and monitoring was performed by testing the samples for hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), a test promoted by the American Diabetes Association for diabetes diagnostic purposes and glycemic control monitoring.2 By providing an average measure of glycemic control over a 3-month period, this test is especially advantageous because fasting is not needed for HbA1c assessment, and no acute perturbations (e.g., stress, diet, exercise) affect HbA1c.2 Finally, we examined the potential benefits of this approach to diabetes screening and glycemic control monitoring according to whether study participants had previous-year tests for blood glucose and previous-year visits to PCPs and dental providers.

METHODS

Study recruitment, participation, and data collection took place in the comprehensive care clinics at the New York University College of Dentistry from June 2013 to April 2014.

Study Participants

Persons were eligible for the research if they indicated that their gums bled on brushing or flossing and if they (1) were aged at least 18 years; (2) did not require antibiotics before dental treatment; (3) did not have a history of severe cardiovascular, hepatic, immunologic, renal, hematologic, or other organ impairment; and (4) had been told by a health care provider that they had diabetes (group 1) or they were at risk for diabetes according to American Diabetes Association criteria (groups 2 and 3).2 These criteria included (1) being aged at least 45 years (group 2) or (2) being aged between 18 and 44 years, having a body mass index (BMI; defined as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters [kg/m2]) of 25 kg/m2 or greater, and having at least 1 of the following additional diabetes risk factors: little or no exercise on a given day; first-degree relative (parent or sibling) with diabetes; Latino ethnicity; Black, Native American, or Pacific Islander race; or being a woman who gave birth to a baby weighing 9 pounds or more (group 3).

Study Procedures

Research assistants recruited New York University College of Dentistry patients when the patients were seated in the clinics’ waiting areas before their scheduled dental appointments, where they were screened for study eligibility. The research assistants oversaw the eligible participant’s completion of a 30-minute survey that assessed sociodemographic characteristics and health care utilization. With the patient seated in the dental chair for the dental procedure, the research assistants collected two 10-µm blood samples (FSB and GCB) with micropipettes. The 2 samples were placed on separate Whatman 903 filter papers (GE Healthcare, Bio-Sciences Corp, Westborough, MA), labeled with separate identification codes, and allowed to dry for 1 hour at room temperature. They were then separately sealed in plastic bags, stored at 4°C, and transported to the laboratory for HbA1c analysis. Only research team members knew the correspondence between FSB and GCB identification codes; the laboratory was masked to this information and analyzed the samples as unique specimens for HbA1c testing.

The laboratory used a high-performance liquid chromatography D-10 program (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc, Hercules, CA), which is traceable to the reference methods of both the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program and the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine, to analyze the blood samples for HbA1c.

Statistical Methods

We assessed the study sample in terms of its sociodemographic and diabetes-related risk characteristics according to the 3 diabetes-related risk groups described in the study’s eligibility criteria. We used χ2 analysis to determine statistically significant differences among these groups and between pairs of these groups.

We measured central tendency, dispersion, and correlation of FSB HbA1c and GCB HbA1c; regression of GCB HbA1c on FSB HbA1c; and the proportion of the sample’s out-of-range FSB HbA1c and GCB HbA1c values in the prediabetes and diabetes ranges. We used these data and analyses, as well as those from 2 Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (ROC) analyses, to determine GCB HbA1c values that could serve as criteria for positive diabetes screening and glycemic control monitoring results. These GCB HbA1c values correspond to elevated FSB HbA1c readings (i.e., in the prediabetes or diabetes ranges: ≥ 5.7%) and diabetes-range readings (i.e., ≥ 6.5%) We then assessed the concurrence of elevated HbA1c in FSB and GCB samples by using percent agreement and Cohen’s κ.13 We also examined the specificity and sensitivity of elevated GCB HbA1c readings relative to gold-standard FSB HbA1c levels. In addition, we evaluated the predictive power of both a positive GCB HbA1c test (≥ 5.7%) and a negative GCB HbA1c test (< 5.7%). We similarly examined concurrence of HbA1c in the diabetes range in FSB and GCB samples. We performed all statistical analyses with IBM PASW version 21 (IBM, Somers, NY).

To determine whether HbA1c testing at the dental visit could benefit persons with or at risk for diabetes, we report the proportion of persons diagnosed with diabetes and for whom glycemic control monitoring would be especially helpful. We also used χ2 analysis to determine the types of persons at risk for diabetes who could most benefit from diabetes screening based on whether they had previous-year testing for blood glucose and clinical visits to PCPs and dental providers within the previous year.

RESULTS

A total of 518 individuals volunteered to participate in the study, and 454 were eligible. Of these 454 individuals, we collected and measured an FSB sample for HbA1c from 441 participants. Paired HbA1c values from GCB were unavailable for 33 of these 441 participants: 17 were not collected because of insufficient bleeding on dental probing during the dental visit and 16 had insufficient oral blood collected on filter paper for laboratory analysis. Thus, there were 408 eligible individuals in the study sample, all of whom had paired HbA1c values from FSB and GCB specimens. On the basis of study eligibility criteria, we divided the study sample into 3 diabetes risk groups: group 1 with 67 persons; group 2 with 245 persons; and group 3 with 96 persons. It is notable that, like the persons in group 3, 54.7% of those in group 2 had a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or greater, as well as at least 1 additional diabetes risk factor.

As shown in Table 1, 56.9% of study participants were female, and two thirds either had some college education (23.4%) or had completed technical school or college (43.1%). Overall, 55.9% were aged between 45 and 64 years, and 18.9% were aged at least 65 years. Their allocations to the diabetes risk groups were dependent, in part, on both age and BMI. Thus, there were statistically significant differences between the groups in terms of age (P < .001), including for all pairwise group comparisons (P < .001). There were also statistically significant differences among the groups in terms of BMI of 25 kg/m2 or greater (P < .001), with groups 1 and 2 each differing significantly from group 3 (P < .001). In all, 70% of the study sample had a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or greater. The majority (59.9%) had little or no daily exercise.

TABLE 1—

Sociodemographic and Diabetes-Related Risk Characteristics of a Sample of Dental Clinic Patients, by Diabetes Risk Groups: New York City, 2013–2014

| Characteristic | Group 1: Told Had Diabetes (n = 67), % | Group 2: Not Told Had Diabetes and Aged ≥ 45 Years (n = 245), % | Group 3: Othera (n = 96), % | Total (n = 408), % |

| Female | 50.7 | 58.0 | 58.3 | 56.9 |

| Age*** | ||||

| 18–44 y | 10.4 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 25.2 |

| 45–64 y | 65.7 | 75.1 | 0.0 | 55.9 |

| ≥ 65 y | 23.9 | 24.9 | 0.0 | 18.9 |

| Highest education | ||||

| ≤ high-school graduate | 37.9 | 31.7 | 34.7 | 33.4 |

| Some college | 24.2 | 20.8 | 29.5 | 23.4 |

| Technical school or college graduate | 37.9 | 47.5 | 35.8 | 43.1 |

| BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2*** | 68.7 | 58.4 | 100.0 | 70.0 |

| Little or no daily exercise | 61.2 | 58.8 | 61.5 | 59.9 |

| First-degree relative with diabetes** | 64.2 | 40.8 | 44.8 | 45.6 |

| Latino ethnicity*** | 29.9 | 24.7 | 46.9 | 30.8 |

| Black, Native American, or Pacific Islander race | 43.1 | 36.4 | 33.3 | 36.7 |

| Among women, had baby ≥ 9 pounds* | 17.6 | 4.9 | 10.7 | 8.2 |

Note. BMI = body mass index (defined as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters).

Not told he or she had diabetes, aged 18–44 y, BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, and ≥ 1 of the following additional diabetes risk factors: little or no exercise on a given day; first-degree relative (parent, sibling) with diabetes; Latino ethnicity; Black, Native American, or Pacific Islander race; woman who gave birth to a baby ≥ 9 pounds.

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

Although there were no statistically significant differences in the 3 study sample groups regarding increased diabetes risk because of race (36.7% were Black, Native American, or Pacific Islander), there were statistically significant differences regarding increased risk for participants because of Latino ethnicity (P < .001). Latinos constituted almost half (46.9%) of the persons in group 3, compared with 29.9% in group 1 (P = .029) and 24.7% in group 2 (P < .001). The groups also differed significantly regarding having a parent or sibling with diabetes (P = .003). Almost two thirds (64.2%) of persons in group 1 had a first-degree relative with diabetes, compared with 40.8% in group 2 (P < .001) and 44.8% in group 3 (P = .015). There were also statistically significant differences among the groups regarding women who had a baby weighing at least 9 pounds at birth (17.6%, 4.9%, and 10.7% in groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively; P = .038), with women in group 1 differing significantly from women in group 2 (P = .011).

Concurrence of Hemoglobin A1c Values in Paired Blood Samples

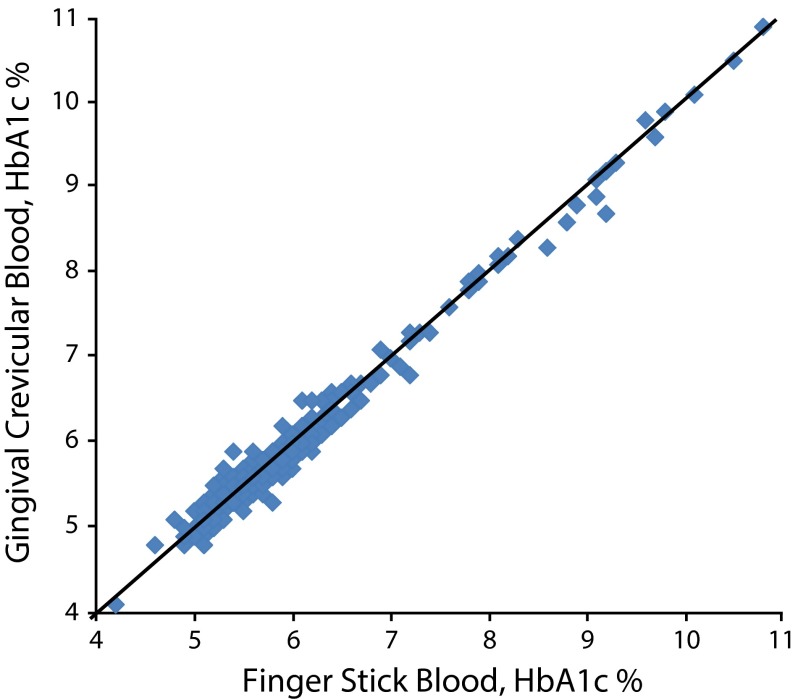

As shown in Figure 1, HbA1c values assessed with FSB and GCB were nearly identical, with a correlation of 0.991. Finger-stick blood HbA1c ranged from 4.2% to 10.8% and GCB HbA1c ranged from 4.1% to 10.9%. Each of the 2 HbA1c measures had a mean of 5.9%, a median of 5.7%, a standard deviation of 0.93, and a standard error of the mean of 0.046. A regression analysis in which GCB HbA1c was regressed on FSB HbA1c yielded

FIGURE 1—

Paired hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) finger stick blood and gingival crevicular blood values in a sample of dental clinic patients: New York City, 2013–2014.

Note. The diagonal line represents equal paired hemoglobin A1c finger stick blood and gingival crevicular blood values.

(1) GCB HbA1c = 0.060 + 0.987 * FSB HbA1c.

We determined that 5.7% and 6.5% were GCB HbA1c values that could serve as criteria for elevated and diabetes-range HbA1c results corresponding to elevated and diabetes-range FSB HbA1c readings, respectively. This determination was made because (1) the means, medians, standard deviations, and standard errors of the means were identical for the study sample’s FSB HbA1c and GCB HbA1c values; (2) the correlation of the 2 HbA1c values was 0.991; (3) the regression of GCB HbA1c on FSB HbA1c had an intercept close to 0 and a slope of almost 1; and (4) in 2 ROC analyses, the sum of (1-sensitivity)2 plus (1-specificity)2 for the GCB HbA1c value of 5.7% as a criterion for elevated HbA1c and 6.5% as a criterion for diabetes-range HbA1c were each close to 0 (0.010 and 0.004, respectively). In the ROC analysis for elevated HbA1c, the area under the ROC curve was 0.976, and in the analysis for diabetes-range HbA1c, the area under the ROC curve was 0.998.

Concurrence of Out-of-Range Hemoglobin A1c Values in Paired Blood Samples

We measured the concurrence of HbA1c values in the FSB and GCB samples for both elevated HbA1c levels and for HbA1c levels in the diabetes range. As shown in Table 2, 53.2% of the study sample had FSB HbA1c values in the prediabetes or diabetes (elevated) ranges, including 13.0% in the diabetes range. When we measured HbA1c with GCB, 51.5% had elevated HbA1c values, including 13.7% in the diabetes range.

TABLE 2—

Concurrence of Elevated and Diabetes-Range Hemoglobin A1c Values From Finger Stick and Gingival Crevicular Blood Testing of a Sample of Dental Clinic Patients: New York City, 2013–2014

| Out-of-Range Values | Out-of-Range Values Based on Finger Stick Blood, % | Out-of-Range Values Based on Oral Blood, % | Percent Agreement | κ | Specificity | Predictive Power of Negative Oral Test | Predictive Power of Positive Oral Test | Sensitivity |

| Prediabetes or diabetes range (HbA1c ≥ 5.7%) | 53.2 | 51.5 | 92.9 | 0.858 | 94.2 | 90.9 | 94.8 | 91.7 |

| Diabetes range (HbA1c ≥ 6.5%) | 13.0 | 13.7 | 97.8 | 0.905 | 98.3 | 99.1 | 89.3 | 94.3 |

Note. HbA1c = hemoglobin A1c.

When we considered agreement between FSB HbA1c and GCB HbA1c for elevated values in either prediabetes or diabetes ranges, the percent agreement was 92.9, remaining high at 85.8 when corrected for chance agreement as measured by κ. Only 11 individuals had a normal FSB HbA1c reading but an elevated GCB HbA1c reading, and 18 had an elevated FSB HbA1c reading but a normal GCB HbA1c reading. Although differences in these 29 individuals’ FSB and GCB sample level readings were small (mean = −0.03; SD = 0.23), a person whose HbA1c level was close to 5.7% could have 1 sample’s HbA1c level in the normal range (< 5.7%) and the other sample’s level in the elevated range (≥ 5.7%). Other measures of concurrence included (1) specificity of the GCB HbA1c of 94.2 and the predictive power of a negative GCB HbA1c test (< 5.7%) of 90.9; and (2) sensitivity of the GCB HbA1c of 91.7 and the predictive power of a positive HbA1c test (≥ 5.7%) of 94.8.

We also considered agreement between FSB HbA1c and GCB HbA1c for values in the diabetes range (Table 2). The percent agreement was 97.8 and the κ statistic was 0.905. Only 6 individuals had a FSB HbA1c reading in the prediabetes range but a diabetes-range GCB HbA1c reading, and 3 had a diabetes-range FSB HbA1c reading but a GCB HbA1c reading in the prediabetes range. Differences in these 9 individuals’ FSB and GCB sample level readings had a mean of 0.10 (SD = 0.24). Other measures of concurrence included (1) specificity of the GCB HbA1c of 98.3 and the predictive power of a negative GCB HbA1c test (< 6.5%) of 99.1; and (2) sensitivity of the GCB HbA1c of 94.3 and the predictive power of a positive HbA1c test (≥ 6.5%) of 89.3.

Potential Beneficiaries of Hemoglobin A1c Testing at Dental Visits

Although all adults with diabetes can potentially benefit from additional opportunities for glycemic control monitoring, these opportunities are especially advantageous for those with elevated HbA1c levels. As shown in Table 3, 92.5% of group 1 participants had GCB HbA1c readings of 5.7% of greater. Hemoglobin A1c monitoring at the dental visit may be particularly helpful for the 71.6% of persons in group 1 who visited dental providers on a yearly or more frequent basis, especially because almost all of these individuals (93.8%) had elevated GCB HbA1c readings. Such opportunities may also be of great benefit to the 12.3% of persons in group 1 who did not visit (or did not have) a PCP in the previous year. All of these individuals had elevated GCB HbA1c values. Whether they saw a PCP in the previous year, 9.4% of group 1 participants noted that their glucose test was conducted more than 1 year ago and all had elevated GCB HbA1c values. As shown in Table 3, results for persons in group 1 with elevated FSB HbA1c readings were very similar.

TABLE 3—

At-Risk Adults Who Could Especially Benefit From Glycemic Control Monitoring and Diabetes Screening at Dental Visits: New York City, 2013–2014

| Variables | Group 1: Told Had Diabetes (n = 67), % | Group 2: Not Told Had Diabetes and Aged ≥ 45 Years (n = 245), % | Group 3: Othera (n = 96), % | P Comparing Group 2 and Group 3 |

| GCB HbA1c ≥ 5.7% | 92.5 | 51.4 | 22.9 | <.001 |

| FSB HbA1c ≥ 5.7% | 89.6 | 54.7 | 24.0 | <.001 |

| Have regular visits with dental provider | 71.6 | 61.7 | 54.2 | .206 |

| GCB HbA1c ≥ 5.7% | 93.8 | 50.7 | 17.3 | <.001 |

| FSB HbA1c ≥ 5.7% | 91.7 | 52.0 | 17.3 | <.001 |

| Did not see primary care provider in past y | 12.3 | 20.2 | 33.3 | .012 |

| GCB HbA1c ≥ 5.7% | 100.0 | 51.1 | 25.8 | .026 |

| FSB HbA1c ≥ 5.7% | 87.5 | 55.3 | 29.0 | .022 |

| Never tested or tested > 1 y ago for blood glucose | 9.4 | 42.2 | 70.1 | <.001 |

| GCB HbA1c ≥ 5.7% | 100.0 | 51.6 | 16.4 | <.001 |

| FSB HbA1c ≥ 5.7% | 100.0 | 53.7 | 18.0 | <.001 |

Note. BMI = body mass index (defined as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters); FSB = finger-stick blood; GCB = gingival crevicular blood; HbA1c = hemoglobin A1c.

Not told he or she had diabetes, aged 18–44 y, BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, and had ≥ 1 of the following additional diabetes risk factors: little or no exercise on a given day; first-degree relative (parent, sibling) with diabetes; Latino ethnicity; Black, Native American, or Pacific Islander race; woman who gave birth to a baby ≥ 9 pounds.

All at-risk persons who were never told they had diabetes can potentially benefit from additional opportunities for diabetes screening, but these opportunities may be more advantageous for one group of at-risk persons compared with another. As shown in Table 3, participants in group 2 (at risk because they were ≥ 45 years) might especially reap great benefit from diabetes screening at dental visits. They were significantly more likely than those in group 3 (at risk because they were aged 18–44 years, had a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, and had ≥ 1 additional diabetes risk factor) to have elevated GCB HbA1c readings (51.4% vs 22.9%; P < .001). This may especially be the case because, in addition to older age being a major risk factor for diabetes,2 the majority of persons in group 2 also had a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or greater and had at least 1 additional diabetes risk factor possessed by persons in group 3. Significantly higher GCB HbA1c readings for subgroups of persons in group 2 compared with group 3 were also the case for those who had regular visits with a dental provider (50.7% vs 17.3%; P < .001), those who did not see a PCP in the previous year (51.1% vs 25.8%; P = .026), and those who were never tested or were tested more than 1 year ago for blood glucose (51.6% vs 16.4%; P < .001). As shown in Table 3, results for persons in groups 2 and 3 with elevated FSB HbA1c readings were very similar.

DISCUSSION

Approximately 46% of all US adults have prediabetes or diabetes.3 Whether measured by using GCB or FSB, about half of our at-risk sample of adults appearing for dental care (51.5% vs 53.2%, respectively) had HbA1c values in prediabetes or diabetes ranges. In addition, 12.3% of all US adults have diabetes3; of our study sample, 13.7% had GCB HbA1c readings in the diabetes range and 13.0% had FSB HbA1c readings in this range. We acknowledge that there were some differences in classification according to prediabetes and diabetes-range HbA1c results with use of FSB and GCB. However, percent agreement, κ, sensitivity, specificity, and the predictive powers of both positive and negative tests of GCB HbA1c relative to FSB HbA1c were extremely high for both elevated HbA1c and HbA1c levels in the diabetes range. Lack of concurrence between FSB HbA1c and GCB HbA1c regarding elevated and diabetes-range HbA1c values was the case for only 29 and 9 of 408 individuals, respectively. This supports the value of diabetes screening and glycemic control monitoring with the approach we employed.

Among persons who had been told that they had diabetes, three quarters had regular visits with dental providers at which time their HbA1c could have been measured. Although only a small proportion of those with a previous diabetes diagnosis did not see a PCP or have a blood glucose test in the previous year, all of these individuals had elevated readings on the GCB HbA1c test, and all but 1 of these individuals had an elevated FSB HbA1c reading. Therefore, patients may benefit from additional glycemic control monitoring in the dental settings that they already use. For those who have a PCP but had not visited that provider in the previous year, the dental provider might encourage such a visit. For those without a regular PCP, the dental provider might emphasize the importance of identifying a PCP and make a referral, when appropriate.

Our findings indicate that at-risk adults aged at least 45 years who had never been told that they had diabetes could especially benefit from HbA1c testing at dental visits. Close to two thirds saw a dental provider on a regular basis, and about half of these persons had elevated HbA1c. Similarly, 1 in 5 did not see a PCP in the previous year, and about half of these individuals had HbA1c levels in the prediabetes or diabetes ranges. In addition, 2 in 5 did not have a blood glucose test in the past 12 months, and about half had elevated HbA1c readings. Many persons aged at least 45 years with elevated HbA1c levels have never been told that they have prediabetes or diabetes, and may remain unaware of their diabetes risk. Therefore, screening for prediabetes and diabetes at alternate sites, such as at the dental visits that patients already attend, offers a key window of opportunity for health assessment and monitoring.

Several limitations to the study are acknowledged. The sample was nonrandom, composed of persons who were at risk for diabetes and its complications, self-selected to participate in the study, and whose gums bled on probing. Although bleeding on probing is widespread among all American adults (approximately half of US adults have periodontal disease and an additional proportion has gingivitis,14 most of whom bleed on probing), and bleeding on probing is especially common among persons with prediabetes and diabetes,15,16 some patients do not bleed on gentle dental probing. For such patients, HbA1c testing could still be performed at dental visits by using blood collected from the finger.12 In addition, although HbA1c values were obtained through laboratory testing, another study limitation involves the use of other data in the analyses that were provided through participant self-report, some of which may have been subject to social desirability or inaccurate recall.

Despite these limitations, our study has considerable public health significance because we identify the value and importance of capitalizing on an opportunity at the dental visit (1) to screen at-risk, but as yet undiagnosed, patients for diabetes (especially those aged ≥ 45 years) and (2) to monitor glycemic control in those already diagnosed so as to enable them to maintain their health to the greatest extent possible.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (grant 1R15DE023201). Portions of the salaries of S. M. Strauss., M. T. Rosedale, N. Kaur, C. M. Juterbock, M. S. Wolff, and D. Malaspina were covered by this grant.

We wish to thank the many nursing students, dentists, dental hygienists, and dental and dental hygiene students who assisted with subject recruitment, blood sample collection, and survey collection support. We also thank the study participants, whose willingness to respond to our questions and allow the collection of finger stick and oral blood samples enabled us to perform the research.

Human Participant Protection

The study was approved by the institutional review board at the New York University School of Medicine.

References

- 1.Diabetes report card 2012. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. US Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/pdf/diabetesreportcard.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2014. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(suppl 1):S14–S80. doi: 10.2337/dc14-S014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Diabetes Association. Fast facts. Data and statistics about diabetes. Available at: http://professional.diabetes.org/admin/UserFiles/0%20-%20Sean/14_fast_facts_june2014_final3.pdf. Accessed September 15, 2014.

- 4.Krishna S, Gillespie KN, McBride TM. Diabetes burden and access to preventive care in the rural United States. J Rural Health. 2010;26(1):3–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2009.00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gillies CL, Abrams KR, Lambert PC et al. Pharmacological and lifestyle interventions to prevent or delay type 2 diabetes in people with impaired glucose tolerance: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007;334(7588):299. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39063.689375.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strauss SM, Alfano MC, Shelley D, Fulmer T. Identifying unaddressed systemic health conditions at dental visits: patients who visited dental practices but not general health care providers in 2008. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(2):253–255. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lalla E, Kunzel C, Burkett S, Cheng B, Lamster IB. Identification of unrecognized diabetes and pre-diabetes in a dental setting. J Dent Res. 2011;90(7):855–860. doi: 10.1177/0022034511407069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barasch A, Gilbert GH, Spurlock N et al. Random plasma glucose values measured in community dental practices: findings from the Dental Practice-Based Research Network. Clin Oral Investig. 2013;17(5):1383–1388. doi: 10.1007/s00784-012-0825-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engström S, Berne C, Gahnberg L, Svärdsudd K. Effectiveness of screening for diabetes mellitus in dental health care. Diabet Med. 2013;30(2):239–245. doi: 10.1111/dme.12009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strauss SM, Tuthill J, Singh G et al. A novel intra-oral diabetes screening approach in periodontal patients: results of a pilot study. J Periodontol. 2012;83(6):699–706. doi: 10.1902/jop.2011.110386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosedale MT, Strauss SM. Diabetes screening at the periodontal visit: patient and provider experiences with two screening approaches. Int J Dent Hyg. 2012;10(4):250–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2011.00542.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L et al. Prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: 2009 and 2010. J Dent Res. 2012;91(10):914–920. doi: 10.1177/0022034512457373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Javed F, Al-Askar M, Al-Rasheed A, Babay N, Al-Hezaimi K. Comparison of self-perceived oral health, periodontal inflammatory conditions and socioeconomic status in individuals with and without prediabetes. Am J Med Sci. 2012;344(2):100–104. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31823650a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campus G, Salem A, Uzzau S, Baldoni E, Tonolo G. Diabetes and periodontal disease: a case–control study. J Periodontol. 2005;76(3):418–425. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.3.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]