Abstract

Objectives. We investigated the impact of reported racism on the mental health of African Americans at cross-sectional time points and longitudinally, over the course of 1 year.

Methods. The Black Linking Inequality, Feelings, and the Environment (LIFE) Study recruited Black residents (n = 144) from a probability sample of 2 predominantly Black New York City neighborhoods during December 2011 to June 2013. Respondents completed self-report surveys, including multiple measures of racism. We conducted assessments at baseline, 2-month follow-up, and 1-year follow-up. Weighted multivariate linear regression models assessed changes in racism and health over time.

Results. Cross-sectional results varied by time point and by outcome, with only some measures associated with distress, and effects were stronger for poor mental health days than for depression. Individuals who denied thinking about their race fared worst. Longitudinally, increasing frequencies of racism predicted worse mental health across all 3 outcomes.

Conclusions. These results support theories of racism as a health-defeating stressor and are among the few that show temporal associations with health.

Racism doggedly structures American social life and institutions. In February 2014—Black History Month—The New York Times reported and editorialized on several racial inequalities and racist events, including overly harsh and racially patterned disciplinary policies in schools; the impact of mass incarceration on disenfranchisement; racial gaps in access to conventional mortgages; the defacement of and hanging of a noose on a campus statue of James Meredith, the University of Mississippi’s first Black student; and the death of Jordan Davis, a Black youth shot by a White man enraged by his playing loud hip-hop (“thug music”).1–5

Most often, experiences with racism are not newsworthy, but quotidian; they are the product of a society for which racism is part and parcel of doing business.6 As a result, individuals who face racism must not only cope with the opportunity costs of racial exclusion but also manage emotional consequences and the awareness that it is likely to be an ongoing stressor.7 Whether as discrete instances of discriminatory exclusion from societal resources or as behaviors and social narratives that subjugate people of African ancestry, racism causes pain that many Black people would rather not acknowledge and to which many Whites remain inured.8 This pain is borne out in empirical research showing that racism negatively affects mental health.

A 2006 review of the literature on racism and health analyzed 62 studies and found negative associations with mental health outcomes to be the most consistent finding.9 Similarly, a meta-analysis published 3 years later identified 110 studies on discrimination and mental health, with outcomes including symptoms of depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, psychological distress, and several measures of general well-being.10 Discrimination was negatively (average zero-order correlation = −0.20) and equally associated across outcomes, with recent and chronic events having stronger effects than cumulative lifetime events. Although findings on mental health are often consistent, it is notable that they emanate from numerous and conceptually distinct measurements of exposure. The 2006 review found 152 different instruments employed.9 These measures assess interpersonal acts, daily hassles, more severe racist events, and nonspecific discrimination (unfair treatment), though the most common theoretical frame is often a stress-coping model.11

Research conducted subsequent to these reviews continues to show the psychological sequelae of racism. One study investigated whether the experience of racism relates most strongly to psychiatric disorders with symptom profiles analogous to responses to racism. Results supported this premise: discriminatory experiences predicted generalized anxiety disorder, with its symptoms of chronic anxiety, worry, and muscle tension.12 Other work has linked racism with symptoms of depression among Black men, and risk increased for men who experienced difficulty in and fears about expressing their feelings.13 Finally, in a sample of US-born Black participants, reports of high levels of discrimination were associated with increased psychological distress, particularly for those who accepted unfair treatment as a fact of life.14

Taken together, accumulated evidence is consistent on the negative mental health effects of racism, but because the majority of work is cross-sectional (76% in 1 review9), the ability to identify causes is reduced and researchers have called for longitudinal studies that better model directionality. One such study investigated everyday discrimination and symptoms of depression among a sample of Black women in Detroit. There, discrimination reported at baseline and change in discrimination over time predicted increases in depression over time.12

We conducted cross-sectional and longitudinal assessments of the mental health impact of experiences with racism. We used self-report of nonspecific psychological distress, symptoms of depression, and the number of days in poor mental health over the past month to examine whether racism reported at baseline was associated with concurrently reported mental health indicators and with indicators 1 year later and whether changes in experiences with racism over time were associated with changes in mental health indicators.

METHODS

The Black Linking Inequality, Feelings, and the Environment (LIFE) Study took place in 2 predominantly Black neighborhoods in New York City, the most populous city in the United States, with 8 175 133 residents. The residents of Brooklyn’s Bedford–Stuyvesant and Manhattan’s Central Harlem have moderate incomes: approximate median household incomes from the 2010 to 2012 American Community Survey 3-year estimates were $36 535 and $36 112, respectively.15 We collected data between December 2011 and June 2013.

Sample and Study Design

We recruited 144 participants at baseline from a probability sample of Black residents in the 2 neighborhoods. We screened randomly selected households to identify eligible adults, and if more than 1 household member was eligible, we randomly selected 1 person to complete the interview. Eligible adults were at least 18 years old, spoke English, self-identified as Black–African American, and had lived in the United States since at least 5 years of age. We excluded those who did not spend their formative years here because experiences with racism in the United States are often different for individuals who grew up elsewhere.14,16,17 Because other portions of the project involved blood draws to examine stress pathway biomarkers, exclusion criteria were surgery or blood transfusions in the past 6 months. Most noneligible households had no Black residents or had residents who could not speak English well enough to complete the survey. The sample was 52% female, with a mean age of 44.6 years.

Trained Black interviewers conducted the surveys. The baseline assessment was a computer-assisted interview conducted in person. We followed participants for 2 additional visits: a 2-month follow up, which comprised a brief telephone interview, and a 1-year follow up, a second in-person computer-assisted interview that was somewhat shorter than at baseline.

Overall response rates to initial recruitment across the 2 neighborhoods were 30% to 35%, reflecting difficulty in making household contact for screening; rates for successfully interviewing people were about 60% once we established that a household had an eligible person. Completion rates for follow-up interviews were 71% to 75%, producing a final sample of 103 participants after 1 year. Comparison of baseline characteristics among individuals lost to follow-up showed that individuals who did not complete the follow-up were younger (mean age = 41.88 years; SD = 17.26 years) than those who did (mean age = 46.20 years; SD = 16.87 years), and were more likely to be men (58.5%) than women (41.5%). These differences were not statistically significant. We found no differences in baseline assessments of racism, health outcomes, or covariates.

Measures

Measures of sociodemographic data included age, gender, years of education, and financial strain. We assessed financial strain by asking participants how comfortably their household lived on the reported income; response choices were “always have enough money for the things you need,” “sometimes don’t have enough money,” and “often don’t have enough money.”

Because relationships between reports of racism and mental health outcomes have varied by the measure employed,12 we used several measures to capture different aspects of experiences with racism. First, we measured lifetime experiences with discriminatory treatment with the Experiences of Discrimination Scale,18 which asks about ever having experienced discrimination attributable to race or ethnicity in 9 domains, such as work, housing, and public settings. The scale yields a numerical count of reported domains as a continuous score.

Second, we assessed more chronic experiences with racism and unfair treatment, which include subordinating and devaluing treatment that may not constitute a discrete instance of discrimination. For this we used the the Daily Life Experiences (DLE) subscale of the Racism and Life Experiences Scales19 and the Everyday Discrimination Scale.20 The DLE explicitly inquires about race as the etiological basis, and the Everyday Discrimination Scale inquires only about unfair treatment. We did not use the 2-stage method,21 in which respondents attribute a given treatment to race and ethnicity or other factors (e.g., gender). Measures of both chronic and recent experiences yield mean scores, with higher scores indicating more frequent experiences with racism.

We also constructed a measure of response to race and racism from 2 of 3 items from the Reactions to Race Module in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.22 The first item, a 7-point Likert scale ranging from never to constantly, inquired about frequency of thinking about race. A second, dichotomous item assessed whether racist experiences caused emotional upset. We combined these 2 items to create a categorical assessment of the extent to which individuals thought about their race in general and experienced emotional upset in the past 30 days. Three categories defined whether respondents did not think about their race and did not experience emotional upset, thought about their race (with any frequency) but did not experience emotional upset, or thought about their race (with any frequency) and experienced emotional upset. We coded as missing the few individuals who reported that they did not think about their race and yet were upset by how they were treated (n = 7 at baseline, 3 at the 2-month follow-up, and 2 at the 1-year follow-up).

Mental health outcomes comprised nonspecific psychological distress measured with the K–6 Scale23; symptoms of depression, measured by the 12-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale24; and the number of days in poor mental health over the past month, from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. The 2-month follow up interview included only the DLE, with days in poor mental health as an outcome. The 1-year follow up was identical to baseline, with 1 exception: we did not readminister the Experiences of Discrimination Scale, which measures lifetime racism, and the other racism measures specified a time frame of the past year.

Analytic Plan

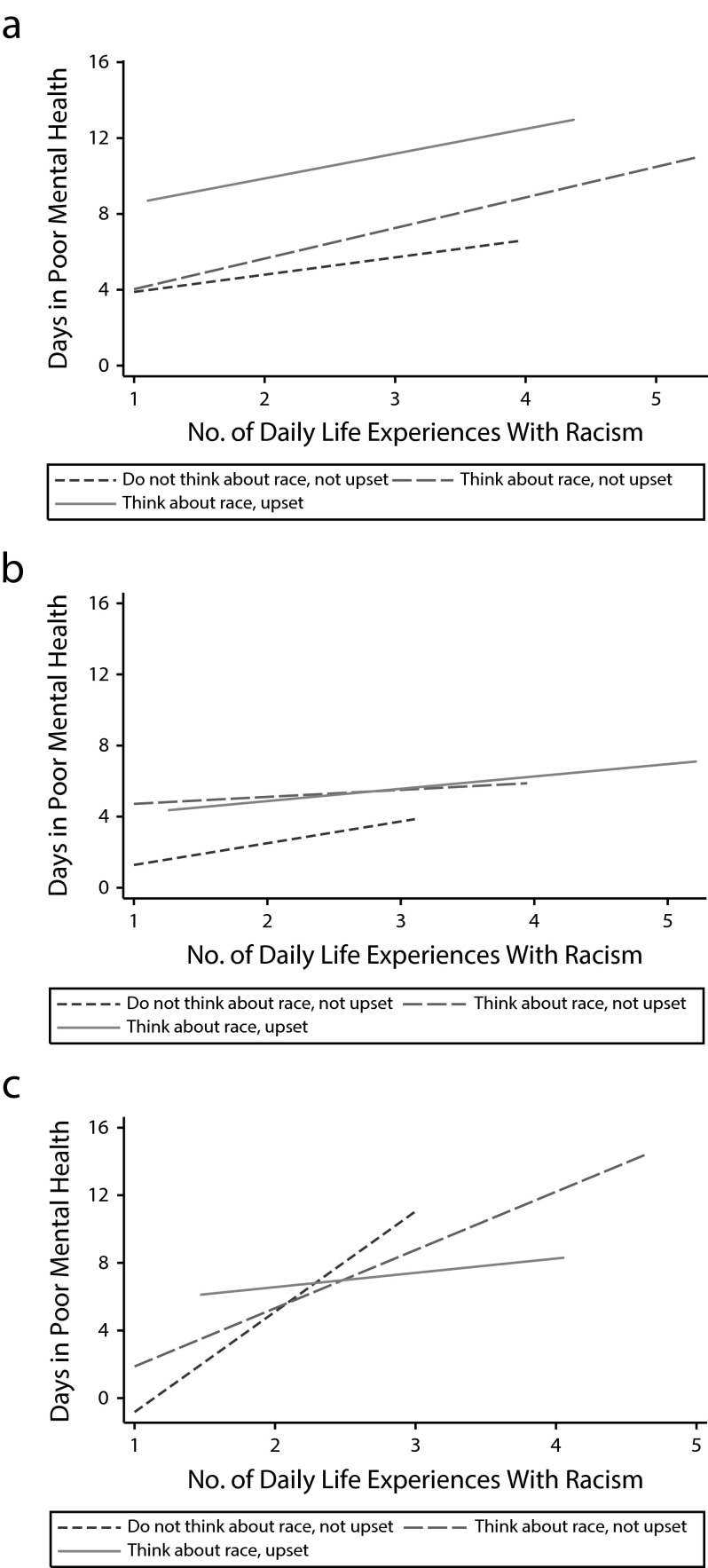

We weighted all analyses to account for nonresponse and poststratification adjustments for age and gender and the stratified sampling design by neighborhood. We conducted regression analyses for survey data with complex sampling designs with Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). We considered results significant at P < .05. We examined data both cross-sectionally at each time point and longitudinally. We fitted weighted linear regression models for complex survey data for continuous outcomes (psychological distress, depression, and days in poor mental health) at each time point, with adjustment for age, gender, education, neighborhood, and financial strain. Predictors of primary interest were everyday discrimination, daily life experiences with racism, and experiences of discrimination. We graphed the fitted regression lines between daily life experiences and poor mental health days, stratified by reactions to race, at each time point. We also examined whether racism reported at baseline predicted mental health outcomes at the 1-year follow-up.

We used weighted multivariate linear regression models with an autoregressive model of order 1 covariance structure to examine change in psychological distress, depression, and days in poor mental health between baseline and the 1-year follow-up with the same predictors as the cross-sectional models. An autoregressive correlation structure assumes observations are related to their own past values such that within an individual, 2 observations taken close in time tend to be more highly correlated than 2 observations taken far apart in time.

RESULTS

Tables 1 and 2 report descriptive statistics of predictors and outcomes at baseline. Socioeconomic characteristics were heterogeneous. Years of education ranged from 3 to 23, with a mean of 13.5 (SD = 2.95). Financial strain was evident for many, with only 29% reporting that they always had enough money for the things they needed.

TABLE 1—

Racism and Mental Health Outcomes at Baseline, by Gender and Socioeconomic Position: Black LIFE Study, New York City, 2011–2013

| Gender |

Financial Straina |

|||||

| Variable | Total Sample, Mean (SE) | Men, Mean (SE) | Women, Mean (SE) | Always Have Enough, Mean (SE) | Sometimes Don’t Have Enough, Mean (SE) | Often Don’t Have Enough, Mean (SE) |

| Experiences of discrimination | 4.04 (0.225) | 4.46 (0.317) | 3.66 (0.313) | 4.59 (0.455) | 3.37 (0.301) | 4.79 (0.459) |

| Everyday discrimination | 2.45 (0.069) | 2.48 (0.100) | 2.42 (0.094) | 2.47 (0.137) | 2.34 (0.091) | 2.64 (0.155) |

| Daily life experiences | 2.38 (0.071) | 2.45 (0.099) | 2.31 (0.102) | 2.43 (0.139) | 2.32 (0.105) | 2.43 (0.134) |

| Psychological distress | 7.69 (0.337) | 6.94 (0.494) | 8.36 (0.451) | 5.88 (0.588) | 8.24 (0.444) | 8.88 (0.803) |

| Depression | 21.04 (0.487) | 20.37 (0.632) | 21.66 (0.729) | 18.49 (0.799) | 21.08 (0.647) | 24.09 (1.040) |

| Days in poor mental health | 7.65 (0.856) | 6.84 (1.220) | 8.41 (1.200) | 4.83 (1.410) | 7.63 (1.210) | 11.88 (2.020) |

Note. LIFE = Linking Inequality, Feelings, and the Environment. Racism was measured with 3 scales: Experiences of Discrimination, Everyday Discrimination, and Daily Life Experiences. Mental health outcomes comprised psychological distress, symptoms of depression, and days in poor mental health.

Respondents were asked whether they had enough for the things they needed.

TABLE 2—

Experiences of Discrimination Scale: Black LIFE Study, New York City, 2011–2013

| Yes, % | No, % | % of Sample | |

| Domains | |||

| At school | 39.86 | 60.14 | |

| Getting hired or getting a job | 57.45 | 42.55 | |

| At work | 50.35 | 49.65 | |

| Getting housing | 26.57 | 73.43 | |

| Getting medical care | 14.79 | 85.21 | |

| Getting service in a store or a restaurant | 68.75 | 31.25 | |

| Getting credit, bank loans, or a mortgage | 29.71 | 70.29 | |

| On the street or in a public setting | 63.19 | 36.81 | |

| From the police or in the courts | 56.64 | 43.36 | |

| Total count of experiences of discrimination | |||

| 0 | 10.45 | ||

| 1 | 8.96 | ||

| 2 | 13.43 | ||

| 3 | 11.94 | ||

| 4 | 8.96 | ||

| 5 | 17.16 | ||

| 6 | 10.45 | ||

| 7 | 8.21 | ||

| 8 | 3.73 | ||

| 9 | 6.72 |

Note. LIFE = Linking Inequality, Feelings, and the Environment. Respondents were asked whether they had experienced discrimination in 9 different domains. Percentages of affirmative and negative responses to each are listed, as well as the total number of domains reported by the sample.

Reports of racism were moderate. Mean scores of everyday discrimination were 2.45 of a possible maximum of 4 and 2.38 of a possible 6 for daily life experiences; mean counts of experiences of discrimination were 4.04 of a possible 9 (Table 1). Men scored higher than women (4.46 vs 3.66; not statistically significant) on the Experiences of Discrimination Scale; differences were minimal on the other measures. Tallies of experiences of discrimination scores showed that the 2 most frequent settings were in stores (69%) and public places (63%). Other high-frequency incidents occurred during interactions with police (57%), hiring (57%), and work (50%; Table 2). Most individuals—slightly more than 50% at each time point—reported thinking about their race but not experiencing emotional upset about how they were treated.

Over time, mean racism scores decreased on both scales, although DLE reports showed greater fluctuation. Distress, depression, and days in poor mental health also differed by gender and over time. Psychological distress declined for both men and women, but women had higher mean scores overall. For depressive symptoms, men’s scores, which were lower than women’s, declined slightly; women’s remained flat.

Mental health outcomes correlated at baseline and the 1-year follow-up, and these bivariate associations strengthened over time. Psychological distress correlated with poor mental health days (baseline, r = 0.397; 1-year follow-up, r = 0.412) and with depression (baseline, r = 0.520; 1-year follow-up, r = 0.667). Depression and poor mental health days correlated as well (baseline, r = 0.525; 1-year follow-up, r = 0.470).

Cross-Sectional Results

At baseline, after adjustment for covariates, neither everyday discrimination nor daily life experiences were significantly associated with psychological distress, but experiences with discrimination were positively associated (b = 0.28; SE = 0.13; P = .03; Table 3). No racism measures were associated with either depression symptoms or days in poor mental health, but some approached statistical significance. Greater financial strain was associated with poorer health for all 3 outcomes. At the 2-month follow-up, neither daily life experiences nor financial strain was associated with the sole outcome at that assessment, poor mental health days.

TABLE 3—

Cross-Sectional Associations Between Racism and Mental Health Outcomes: Black LIFE Study, New York City, 2011–2013

| Variable | Psychological Distress, b (95% CI) | Depression, b (95% CI) | Days in Poor Mental Health, b (95% CI) |

| Everyday discrimination, baseline | |||

| Everyday discrimination | 0.55 (−0.16, 1.26) | 0.05 (−0.04, 0.13) | 1.76 (−0.10, 3.63) |

| Age | −0.06 (−0.10, −0.03) | 0.00 (−0.01, 0.00) | −0.05 (−0.15, 0.05) |

| Gender | 1.14 (−0.02, 2.29) | 0.12 (−0.03, 0.26) | 2.13 (−1.09, 5.35) |

| Education, y | 0.11 (−0.12, 0.33) | −0.01 (−0.04, 0.03) | −0.04 (−0.57, 0.49) |

| Neighborhood | 1.23 (−0.02, 2.48) | 0.07 (−0.10, 0.23) | −0.20 (−3.98, 3.57) |

| Financial straina | |||

| Always have enough (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Sometimes do not have enough | 2.35 (0.92, 3.79) | 0.25 (0.07, 0.43) | 3.66 (−0.27, 7.58) |

| Often do not have enough | 2.38 (0.67, 4.09) | 0.33 (0.12, 0.53) | 5.34 (0.62, 10.06) |

| Daily life experiences, baseline | |||

| Daily life experiences | 0.60 (−0.16, 1.35) | 0.10 (−0.01, 0.20) | 2.08 (−0.11, 4.25) |

| Age | −0.06 (−0.10, −0.02) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.01) | −0.03 (−0.13, 0.07) |

| Gender | 1.15 (−0.10, 2.32) | 0.13 (−0.02, 0.27) | 2.25 (−1.06, 5.56) |

| Education, y | 0.10 (−0.12, 0.31) | −0.01 (−0.05, 0.02) | −0.09 (−0.61, 0.43) |

| Neighborhood | 1.24 (0.02, 2.45) | 0.05 (−0.11, 0.21) | −0.23 (−3.91, 3.45) |

| Financial straina | |||

| Always have enough (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Sometimes do not have enough | 2.30 (0.91, 3.69) | 0.24 (0.05, 0.42) | 3.44 (−0.44, 7.31) |

| Often do not have enough | 2.43 (0.75, 4.11) | 0.32 (0.12, 0.53) | 5.49 (0.73, 10.24) |

| Experiences of discrimination, baseline | |||

| Experiences of discrimination | 0.28 (0.03, 0.54) | 0.02 (−0.01, 0.05) | 0.63 (−0.11, 1.38) |

| Age | −0.08 (−0.12, −0.03) | 0.00 (−0.01, 0.00) | −0.07 (−0.18, 0.04) |

| Gender | 1.45 (0.25, 2.66) | 0.12 (−0.04, 0.29) | 2.79 (−0.78, 6.35) |

| Education, y | 0.07 (−0.17, 0.31) | −0.01 (−0.05, 0.03) | −0.21 (−0.86, 0.43) |

| Neighborhood | 1.12 (−0.09, 2.42) | 0.05 (−0.12, 0.23) | 0.34 (−3.56, 4.23) |

| Financial straina | |||

| Always have enough (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Sometimes do not have enough | 2.46 (0.10, 3.92) | 0.24 (0.05, 0.43) | 3.05 (−1.05, 7.15) |

| Often do not have enough | 2.26 (0.45, 4.07) | 0.34 (0.09, 0.58) | 5.13 (−0.55, 10.82) |

| Daily life experiences, 2-mo follow-up | |||

| Daily life experiences | 0.78 (−1.14, 2.71) | ||

| Age | −0.01 (−0.1094, 0.08) | ||

| Gender | 0.43 (−2.53, 3.39) | ||

| Education, y | −0.17 (−0.65, 0.30) | ||

| Neighborhood | 0.92 (−1.90, 3.73) | ||

| Financial straina | |||

| Always have enough (Ref) | 1.00 | ||

| Sometimes do not have enough | −0.69 (−4.02, 2.64) | ||

| Often do not have enough | 2.37 (−1.90, 6.64) | ||

| Everyday discrimination, 1-y follow-up | |||

| Everyday discrimination | 0.05 (−1.47, 1.57) | 0.02 (−0.12, 0.16) | 3.70 (0.58, 6.81) |

| Age | 0.04 (−0.10, 0.02) | 0.00 (−0.01, 0.01) | −0.03 (−0.12, 0.047) |

| Gender | 0.73 (−1.23, 2.70) | 0.12 (−0.09, 0.33) | 0.84 (−2.50, 4.18) |

| Education, y | 0.15 (−0.19, 0.43) | 0.00 (−0.05, 0.04) | −0.07 (−0.73, 0.60) |

| Neighborhood | −0.83 (−2.77, 1.11) | −0.06 (−0.28, 0.16) | 1.19 (−1.95, 4.33) |

| Financial straina | |||

| Always have enough (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Sometimes do not have enough | 1.63 (−0.60, 3.86) | 0.20 (−0.03, 0.42) | 1.56 (−1.93, 5.05) |

| Often do not have enough | 3.92 (1.18, 6.65) | 0.37 (0.10, 0.64) | 6.563 (0.30, 12.83) |

| Daily life experiences, 1-y follow-up | |||

| Daily life experiences | 0.91 (−0.59, 2.40) | 0.16 (0.02, 0.29) | 2.93 (0.47, 5.39) |

| Age | −0.03 (−0.09, 0.024) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.01) | −0.03 (−0.12, 0.06) |

| Gender | 0.62 (−1.35, 2.59) | 0.10 (−0.10, 0.31) | 0.76 (−2.67, 4.19) |

| Education, y | 0.09 (−0.22, 0.40) | −0.01 (−0.05, 0.03) | −0.23 (−0.87, 0.416) |

| Neighborhood | −0.77 (−2.67, 1.13) | −0.05 (−0.26, 0.16) | 1.54 (−1.68, 4.76) |

| Financial straina | |||

| Always have enough (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Sometimes do not have enough | 1.57 (−0.75, 3.88) | 0.19 (−0.05, 0.42) | 1.19 (−2.38, 4.76) |

| Often do not have enough | 3.56 (0.67, 6.45) | 0.31 (0.032, 0.58) | 6.18 (−0.08, 12.45) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; LIFE = Linking Inequality, Feelings, and the Environment.

Respondents were asked whether they had enough for the things they needed.

At the 1-year follow-up, the effects of racism and mental health varied both by the explanatory measure and outcome. Racism was not associated with psychological distress. Daily life experiences (b = 0.16; SE = 0.07; P = .02), but not everyday discrimination, were positively related to depression symptoms. Finally, both measures were associated with poor mental health days. Each unit increase on the DLE scale was associated with 2.93 additional days in poor mental health and each unit increase in the everyday discrimination scale with 3.70 additional days in poor mental health. These associations emerged after we controlled for all covariates, including financial strain, which showed a strong effect on poor mental health days. R2 averaged 0.25 and 0.23 for models of distress at baseline and the 1-year follow-up, respectively, 0.13 and 0.16 for depression, and 0.09 and 0.21 for days in poor mental health.

We graphed the association between daily life experiences and poor mental health days for respondents in each category of reactions to race, at each time point (Figure 1). At baseline, all 3 groups evinced a positive association between daily life experiences and poor mental health, at similar slopes. But those who denied thinking about their race or being emotionally upset by racist treatment reported the fewest poor mental health days and the lowest frequencies of racism. At the 2-month follow-up, effects flattened, and individuals who did not think about their race differed from the other 2 groups, again reporting the lowest levels of racism but bearing the greatest impact of racism on mental health. This stronger relationship persisted at the 1-year follow-up and indeed grew more pronounced.

FIGURE 1—

Associations between racism and days in poor mental health by reactions to race at (a) baseline, (b) 2-month follow up, and (c) 1-year follow-up: Black LIFE Study, New York City, 2011–2013.

Note. LIFE = Linking, Inequality, Feelings, and the Environment.

Longitudinal Results

We first examined whether racism reported at baseline affected mental health outcomes at the 1-year follow-up. We observed no effects for distress or depression. For mental health days, DLE showed a negative outcome: a 1-unit change at baseline was associated with 2 additional days of poor mental health (b = 2.10; SE = 0.91).

We next examined whether change in racism over the 2 time points (days in poor mental health over 3 time points) was associated with a change in health outcomes. The estimates in Table 4 model the impact of changes in everyday discrimination and daily life experiences on distress, symptoms of depression, and poor mental health days. For both measures of racism, we observed a statistically significant positive relationship for all outcomes, indicating that an increase in discrimination over time was associated with an increase in the respective health outcome. For example, each unit change in everyday discrimination over the year produced an increase of 1.3 on the measure of distress; results were similar for the DLE scale. However, racism’s impact on symptoms of depression was weaker. Finally, estimates of the longitudinal effect of racism on days spent in poor mental health showed that each unit increase in everyday discrimination produced 3.2 more days and each unit increase in DLE scores produced 2.2 more days of poor mental health.

TABLE 4—

Longitudinal Associations Between Racism and Mental Health Outcomes: Black LIFE Study, New York City, 2011–2013

| Variable | Change in Psychological Distress, b (95% CI) | Change in Depression, b (95% CI) | Change in Days in Poor Mental Health, b (95% CI) |

| Everyday discrimination | |||

| Change | 1.29 (0.65, 1.94) | 0.09 (0.02, 0.16) | 3.16 (1.64, 4.68) |

| Age | −0.04 (−0.09, 0.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.01) | −0.03 (−0.11, 0.05) |

| Gender | 1.12 (−0.33, 2.56) | 0.14 (−0.02, 0.30) | 2.52 (−0.51, 5.56) |

| Years of education | 0.13 (−0.14, 0.40) | 0.00 (−0.05, 0.04) | −0.17 (−0.65, 0.31) |

| Neighborhood | −0.01 (−1.55, 1.53) | 0.01 (−0.16, 0.18) | −0.08 (−3.02, 2.86) |

| Financial straina | |||

| Always have enough (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Sometimes do not have enough | 1.61 (0.04, 3.18) | 0.17 (0.02, 0.31) | 2.48 (0.04, 4.93) |

| Often do not have enough | 2.82 (0.85, 4.79) | 0.30 (0.10, 0.49) | 5.68 (2.44, 8.92) |

| Daily life experiences | |||

| Change | 1.26 (0.40, 2.12) | 0.15 (0.07, 0.24) | 2.21 (0.58, 3.83) |

| Age | −0.04 (−0.08, 0.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.07) | −0.03 (−0.11, 0.06) |

| Gender | 1.11 (−0.25, 2.48) | 0.14 (−0.021, 0.295) | 2.65 (−0.35, 5.65) |

| Years of education | 0.08 (−0.14, 0.31) | −0.01 (−0.05, 0.02) | −0.26 (−0.69, 0.18) |

| Neighborhood | 0.03 (−1.43, 1.48) | 0.01 (−0.15, 0.17) | 0.05 (−2.88, 2.99) |

| Financial straina | |||

| Always have enough (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Sometimes do not have enough | 1.58 (−0.09, 3.25) | 0.14 (−0.01, 0.29) | 2.10 (−0.29, 4.49) |

| Often do not have enough | 3.11 (1.03, 5.18) | 0.25 (0.04, 0.45) | 5.63 (2.16, 9.10) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; LIFE = Linking Inequality, Feelings, and the Environment.

Respondents were asked whether they had enough for the things they needed.

DISCUSSION

We investigated the cross-sectional and longitudinal effects of racism on psychological distress, symptoms of depression, and days in poor mental health. Overall levels of reported racism were moderate but were still deleterious to mental health. The frequencies we observed were greater than were found in other studies that used the same measures.13,14 Concordant with results from a sample of US-born Black respondents in Boston,14 top settings for experiencing discrimination in the Black Life Study were public places and stores, but the percentages in our study were higher. For example, 42% of Boston respondents and 63% of our participants faced racism in public settings. Cross-sectional results varied by time point and by outcome: our respondents' experiences with discrimination were associated with distress, as in other studies,14 but other measures showed no relationship, and effects were stronger for poor mental health days than for depression. Longitudinally, increasing frequencies of racism predicted worse mental health across all 3 outcomes.

Also of note was effect moderation by reaction to race. Ours was one of the few studies analyzing how racism interacts with racial centrality to affect depression, particularly in a longitudinal context. We might expect that individuals who do not think about their race would experience minimal decrements in mental health. In fact, despite reporting less racism and fewer days of poor mental health, these individuals had more acute negative health effects than those who acknowledged thinking about their race with any degree of frequency. These findings evoke earlier reports suggesting that denying racism negatively affected hypertension.25 Other work has shown that Black people who accept unfair treatment as a fact of life have greater distress than those who take action and talk about it.14 In our sample, it appeared that actively processing the reality of race blunted the blow to mental health, in agreement with other studies. For example, individuals for whom racial identity is central to self-concept experience less negative impact from discrimination on psychological distress.26 This may be because these individuals are better equipped to mobilize coping responses to racism and to distinguish between actions directed at their racial group and at themselves.7

For most respondents, processing the reality of race was a necessity of negotiating life in New York City. They acknowledged incidents across several domains, including interactions with the police (57%). This likely reflects in part the New York Police Department’s stop-and-frisk policies, which produced 685 724 stops in 2011, of which 53% involved Black persons27; the policy was ruled unconstitutional in a federal lawsuit.28 Several respondents commented on the use of race as a marker for suspicion and wrongdoing: “The police always stop me for no reason at all.” “Being stopped by cops. Stopped and frisked because you were Black. For no other reason.” Thus, although the Everyday Discrimination Scale classifies being stopped by the police as a major event, in New York City, this is often a day-to-day occurrence, particularly for men and adolescent boys.

Strengths and Limitations

We assessed experiences with racism from multiple vantage points, including chronic recent and lifetime exposure, enabling a more comprehensive analysis. Existing instruments vary in content and explicitness of attribution to race. Scales without explicitly racial language require respondents to make difficult distinctions to sort out the source of discriminatory actions and may affect whether it is reported.11 Indeed, 2-stage scales without racial attributions garner the highest amount of endorsement. For discrimination specific to race and ethnicity, 1-stage items garner higher endorsement than 2-stage (e.g., 83% vs 53% among Black people).21 Two of the 3 measures we employed specifically addressed racial discrimination; the Everyday Discrimination Scale did not. However, because the measure was administered among scales that employed racial terminology, it is logical to assume that respondents continued to use that frame. Caution is necessary when comparing our reported prevalence to responses derived from scales that assess generic unfair treatment or use 2-stage questions.

By contrast with much of the literature, we conducted longitudinal analyses, and the impact was clear. Although reported racism at baseline did not predict outcomes 1 year later, changes in racism over time predicted changes in health outcomes, commensurate with other work and with estimates of similar magnitude.12 In other words, increasing racism was associated with worsening mental health. For example, regression coefficients indicated that racism was associated with 3 to 4 additional days in poor mental health. These results provide some evidence for causal explanations of the negative health impact of racism.

Although longitudinal analyses have more power than cross-sectional studies, the overall sample size and the sample size at each time point (some participants were lost between baseline and the 1-year follow-up) may have limited power to test hypotheses. As with all self-report methods, we cannot rule out the possibility that an unmeasured underlying factor shaped both reports of racism and mental health. However, as noted elsewhere,14 the heterogeneous effects we observed partly dispel the notion of an underlying propensity to endorse negative events.

Generalizability must be interpreted with caution. Relatively low response rates temper ability to generalize to target New York City neighborhoods. Because we drew our sample from 2 of the largest Black neighborhoods in the country’s largest city, which has a large proportion of Black residents, it is unclear to what extent these findings may generalize to other urban or nonurban settings.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that cross-sectional studies may paint an incomplete picture of racism’s health consequences. Failure to detect an association between racism and mental health at a discrete time may not reflect a null effect, because repercussions may emerge or strengthen at a different point in respondents’ lives. Indeed, our models of poor mental health showed a doubling in the proportion of explained variance over time. More research is needed to identify the processes underlying the heterogeneity in and strengthening of associations. For example, individual circumstances or differing social milieus may potentiate sensitivity to racism. The trial of George Zimmerman, the man who shot and killed Trayvon Martin, an unarmed Black youth, took place during our data collection (and concluded after the study ended).29 The significant impact this case had for many Black people may have shaped health responses to individual encounters with racism.

Future studies should examine large-scale interventions implemented at the level of neighborhoods30 and cities to redress the health detriments of racism. Study respondents’ accounts of racism as occurring in public spaces—restaurants, stores, workplaces, and other settings—call attention to the need for cities to turn greater attention to the contexts that enable and perpetuate racial inequality. Such efforts would constitute not only social justice, but also, because of the impact on mental health, important health policy.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a Director’s New Innovator Award from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (DP2 OD006513).

We thank the Center for Survey Research at the University of Massachusetts; Michael Elliott, University of Michigan; and Community Board 3 in Brooklyn for their collaboration, consulting, and assistance. We also thank the individuals who made this research possible: the respondents who participated in the project and members of the Black LIFE Study research team.

Note. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Office of the Director or the National Institutes of Health.

Human Participant Protection

This project received approval from the Rutgers University institutional review board.

References

- 1.Alvarez L. Jury reaches partial verdict in Florida killing over loud music. New York Times. February 15, 2014:A20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.6 Million Americans without a voice. New York Times. February 11, 2014:A26. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ross RK, Zimmerman KH. Real discipline in school. New York Times. February 16, 2014:A19. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prevost L. Race gap on conventional loans. New York Times. January 30, 2014:RE8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blinder A. Ole Miss students may face charges in racist episode. New York Times. February 21, 2014:A13. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delgado R, Stefancic J. Critical Race Theory: An Introduction. New York, NY: New York University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brondolo E, Brady ver Halen N, Pencille M, Beatty D, Contrada RJ. Coping with racism: a selective review of the literature and a theoretical and methodological critique. J Behav Med. 2009;32(1):64–88. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9193-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper B. The vile pain of racial taunts: Marcus Smart, DMX and White supremacy’s sick power. 2014. Available at: http://www.salon.com/2014/02/11/the_vile_pain_of_racial_taunts_marcus_smart_dmx_and_white_supremacys_sick_power. Accessed October 2, 2014.

- 9.Paradies Y. A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(4):888–901. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pascoe EA, Smart Richman L. Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(4):531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bastos JL, Celeste RK, Faerstein E, Barros AJD. Racial discrimination and health: a systematic review of scales with a focus on their psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(7):1091–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schulz AJ, Gravlee CC, Williams DR, Israel BA, Mentz G, Rowe Z. Discrimination, symptoms of depression, and self-rated health among African American women in Detroit: results from a longitudinal analysis. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(7):1265–1270. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammond WP. Taking it like a man: masculine role norms as moderators of the racial discrimination-depressive symptoms association among African American men. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(suppl 2):S232–S241. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krieger N, Kosheleva A, Waterman PD, Chen JT, Koenen K. Racial discrimination, psychological distress, and self-rated health among US-born and foreign-born Black Americans. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(9):1704–1713. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.New York City Dept of City Planning. Population: American Community Survey. 2014. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/dcp/pdf/census/puma_econ_10to12_acs.pdf. Accessed October 12, 2014.

- 16.Dominguez TP, Dunkel-Schetter C, Glynn LM, Hobel C, Sandman CA. Racial differences in birth outcomes: the role of general, pregnancy, and racism stress. Health Psychol. 2008;27(2):194–203. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soto JA, Dawson-Andoh NA, BeLue R. The relationship between perceived discrimination and generalized anxiety disorder among African Americans, Afro Caribbeans, and non-Hispanic Whites. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25(2):258–265. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of discrimination: validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(7):1576–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrell SP. 6th Biennial Conference on Community Research and Action, Society for Community Research and Action. Columbia, SC: 1997. Development and initial validation of scales to measure racism-related stress. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: socio-economic status, stress, and discrimination. J Health Psychol. 1997;2(3):335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shariff-Marco S, Breen N, Landrine H et al. Measuring everyday racial/ethnic discrimination in health surveys. Du Bois Rev. 2011;8(1):159–177. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X11000129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Reactions to race module, 2011 BRFSS questionnaire. 2011. Available at: http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/BRFSSQuest/index.asp. Accessed October 12, 2014.

- 23.Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ et al. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184–189. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krieger N, Sidney S. Racial discrimination and blood pressure: the CARDIA Study of young Black and White adults. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(10):1370–1378. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.10.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sellers RM, Caldwell CH, Schmeelk-Cone KH, Zimmerman MA. Racial identity, racial discrimination, perceived stress, and psychological distress among African American young adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44(3):302–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stop-and-Frisk Activity in 2011. New York Civil Liberties Union; 2012.

- 28.Floyd v City of New York. No. 08 Civ. 1034 (SAS) F.Supp.2d, 2013 WL 4046209 (S.D.N.Y. filed. Aug. 12, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alvarez L, Buckley C. Zimmerman is acquitted in Trayvon Martin killing. New York Times. July 13, 2013:A1. [Google Scholar]

- 30.J Urban Health. 2014;91(5):851–872. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9873-8. Kwate NOA. “Racism Still Exists”: a public health intervention using racism “countermarketing” outdoor advertising in a Black neighborhood. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]