Abstract

Studies have linked the consumption of sugary drinks to weight gain, obesity, and type 2 diabetes. Since 2006, New York City has taken several actions to reduce consumption.

Nutrition standards limited sugary drinks served by city agencies. Mass media campaigns educated New Yorkers on the added sugars in sugary drinks and their health impact. Policy proposals included an excise tax, a restriction on use of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits, and a cap on sugary drink portion sizes in food service establishments.

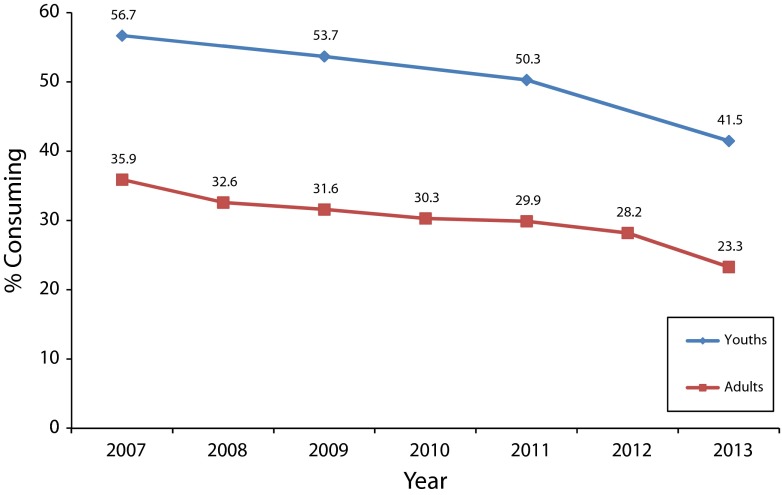

These initiatives were accompanied by a 35% decrease in the number of New York City adults consuming one or more sugary drinks a day and a 27% decrease in public high school students doing so from 2007 to 2013.

From 1977 to the early 2000s, Americans dramatically increased their consumption of sugary drinks, including carbonated beverages, fruit drinks, sports and energy drinks, and other drinks with added sugars.1 A nationally representative survey conducted in 2009 to 2010 found that sugary drinks contributed approximately 150 calories a day to the diet of both adults and youths, with some subgroups consuming far more; for example, adolescent boys consumed a mean of 278 calories per day, and men aged 20 to 39 years consumed a mean of 258 calories per day.2 Numerous studies have linked the intake of sugary drinks, the largest single source of added sugars in the diet, with weight gain, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and heart disease.3–8

Because of the health and economic toll of the obesity epidemic and the contribution of sugary drinks to poor health outcomes, many public health organizations support reducing the consumption of sugary drinks. We have described the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene’s (DOHMH’s) multipronged efforts to reduce sugary drink consumption from 2006 to 2013, which has included institutional changes, education via mass media, and regulatory and legislative policy proposals.

INSTITUTIONAL CHANGES

In 2008, by mayoral executive authority, nutrition standards were established for foods purchased and for meals and snacks served by city agencies and contracted service providers.9,10 In addition to meal nutrient standards, the standards required that beverages contain no more than 25 calories per eight ounces, with the exception of 100% fruit juice and milk. The standards apply to more than 260 million meals and snacks served annually in schools, senior centers, homeless shelters, public hospitals, correctional facilities, and other settings. In addition, standards for more than 3000 beverage vending machines located in city agencies were established, which required beverages with more than 25 calories per eight ounces to be in sizes of 12 ounces or less and to occupy no more than the two vending slots with the lowest selling potential.

To expand the reach of the standards, starting in 2010, DOHMH worked with more than 15, or about one third of private hospitals, to voluntarily implement nutrition standards for vending machines, patient meals, and cafeterias. Vending and patient meal standards were the same as those for city agencies. The cafeteria standard required that water be available at no charge, 75% of beverage options have less than 25 calories per eight ounces, and beverages with more than 25 calories per eight ounces be in sizes of 16 ounces or less.11

MASS MEDIA EDUCATIONAL CAMPAIGNS

In view of the success of hard-hitting mass media educational campaigns on reducing smoking, starting in 2009 DOHMH developed and aired campaigns to reduce sugary drink consumption in the New York City market. These campaigns, part of a series called “Pouring on the Pounds,” raised awareness of the added sugars in sugary drinks and their association with weight gain, obesity, and diabetes. One campaign demonstrated that the added sugars from consuming one sugary drink a day was equivalent to consuming 50 pounds of sugar over a year and incorporated graphic images of the health consequences, including diabetes and obesity. Another campaign informed New Yorkers how many miles they would have to walk to burn off the calories from various portions of sugary beverages and illustrated this distance on New York City maps.

In 2013, a campaign focused on sports and energy drinks because they are increasingly consumed.12 Overall, DOHMH has created seven campaigns since 2009, with television campaigns ranging from 600 to 1200 gross rating points, defined as the percentage of target market reached multiplied by frequency of exposure. This means that New Yorkers on average were exposed to the campaigns six to 12 times over a duration of usually three to four weeks. The information from these campaigns was presented to more than 300 community- and faith-based institutions, many of which adopted healthier policies, such as serving water instead of sugary drinks at meetings.

A street intercept survey of 1200 New Yorkers evaluated one of the campaign advertisements in 2011. Three fourths of respondents recalled seeing the campaigns, and about half of those who recalled seeing them said that they had reduced their consumption of sugary drinks.13 To date, the “Pouring on the Pounds” series has generated millions of audience impressions, more than 300 earned media placements, and more than 50 000 likes on Facebook. More than 30 municipalities around the country have adapted the campaigns for their own use.

REGULATORY POLICY CHANGES

Through the city’s board of health, a regulatory body whose authority includes the control of chronic diseases and supervision and regulation of food service establishments, policies have been developed to decrease the consumption of sugary drinks in childcare facilities, children’s camps, and food service establishments.

The New York City Board of Health passed nutritional standards for early childcare centers in 200614 and children’s camps in 2012.15 Regulations for both require that water be easily accessible at all times and 100% juice be in portions of 6 ounces or less, and prohibit beverages with added sweeteners.

In 2008, the board of health passed a regulation requiring New York City food service establishments with more than 15 locations nationwide to post calorie counts on menus and menu boards for all products, including beverages.16 A DOHMH study found that fewer beverages were purchased among those who reported seeing and using calorie information than among those who did not.17 The regulation was the first of its kind in the country, and since then, similar laws have been passed in at least 19 other jurisdictions. In 2010, Congress passed a similar requirement via the Affordable Care Act; final regulations from the Food and Drug Administration go into effect in 2015.18

The portion cap rule, introduced to the board of health in 2012, addressed the excessive portion sizes of sugary drinks in food service establishments.19 On the basis of studies that show larger portion sizes lead to increased consumption,20–22 the rule set a 16-ounce limit on the size of containers used for sugary drinks in food service establishments, including restaurants, mobile food vendors, and concession stands. Although the board of health passed the rule, its authority to do so was challenged in court, and the rule was overturned. Although the policy was not implemented, its introduction generated unprecedented media coverage and mention from public figures, thus increasing awareness nationwide of the link between sugary drinks and obesity.

OTHER POLICY PROPOSALS

In 2009 and 2010, the New York State governor’s budget included proposals to tax sugary drinks. The first year the proposal was for an 18% sales tax and the second year for a 1 cent per ounce excise tax, which would have had a similar effect on retail prices and was estimated to reduce consumption by 10%.23 The second-year proposal was supported by more than 60 health organizations but was met with a surge of lobbying by industry, which spent $9 million in the first four months of 2010 alone.24 The state budget was ultimately passed without the tax. Other jurisdictions have subsequently proposed similar sugary drink excise taxes; Mexico successfully passed a one peso per ounce tax on sugary drinks in 2013, and Berkeley, California, passed a one penny per ounce tax in 2014. News reports suggest that because of the tax, sales of sugary drinks have declined in Mexico.

In 2010, New York City and the State of New York requested permission from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) for a two-year demonstration project to remove sugary drinks from the list of allowable purchases through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.25 Whereas sugary drinks are no longer allowed in the USDA’s Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children, the National School Lunch Program, and the School Breakfast Program, an estimated $2.1 billion dollars’ worth of sugary drinks are purchased annually through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.26 The USDA rejected the proposal, citing the concern that the project was too complex in scope, among other reasons. Since 2010, other jurisdictions have considered similar proposals, and Congress has proposed amendments to the Farm Bill that would require the USDA to consider such waiver requests, although none of these attempts have come to fruition. Both the tax proposals and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program waiver proposals, like the portion cap proposal, received much media attention that reinforced the message that sugary drink consumption has adverse health effects.

TRENDS IN CONSUMPTION

In an annual random-digit-dial health survey of 9000 New Yorkers, DOHMH measured sugary drink consumption among adults by assessing carbonated and noncarbonated sugary drink consumption.27 The survey questions asked, “How often do you drink sugar-sweetened soda?” and

How often do you drink other sweetened drinks like sweetened iced tea, sports drinks, fruit punch, or other fruit-flavored drinks? (Do not include diet soda, sugar-free drinks, or 100% juice).

A biannual school-based self-administered survey assessed overall sugary drink consumption among youths by assessing carbonated and noncarbonated sugary drink consumption.28 The question about carbonated beverages asked,

During the past seven days, how many times did you drink a can, bottle, or glass of soda or pop, such as Coke, Pepsi, or Sprite? (Do not count diet soda or diet pop).

The question about noncarbonated sugary drink consumption asked,

During the past seven days, how many times did you drink other sweetened drinks such as sports drinks, fruit punch, other fruit-flavored drinks, or chocolate or other flavored milk? (Do not count diet or sugar-free drinks).

In 2013, the question changed to

During the past seven days, how many times did you drink other sugar-sweetened drinks such as sports drinks, energy drinks, fruit punch, or sugar-sweetened teas? (Do not count diet or sugar-free drinks).

In 2013, 23.3% of adult New Yorkers reported drinking one or more sugary drinks per day, compared with 35.9% in 2007, a decrease of 12.6 percentage points, which means a 35.0% reduction in New Yorkers consuming one or more sugary drinks daily (P < .001; Figure 1). The proportion of New York City public high school students who reported drinking one or more sugary drinks per day decreased from 56.7% in 2007 to 41.5% in 2013, a decrease of 15.2 percentage points, which is a 27.0% reduction (P < .001). Soda consumption, specifically, decreased from 23.5% to 15.7% among public high school students, a decrease of 7.8 percentage points, which is a 33.0% reduction in youths consuming one or more sugary drinks daily (P < .001; data not shown).

FIGURE 1—

Adult and youth sugary drink consumption: New York City, 2007–2013.

CONCLUSIONS

Over the past seven years, New York City has implemented interventions to reduce sugary drink consumption, including educational campaigns and organizational food policies, and has attempted many others. Although, the decline in consumption is an observational result and cannot be directly attributed to efforts, these efforts have increased public awareness of the health risks of sugary drinks and have started a national conversation on strategies to reduce consumption of them.

Acknowledgements

We thank Lynn Silver for her review of the article and her leadership in many of the initiatives described. We thank Deborah Deitcher for editorial assistance.

References

- 1.Nielsen SJ, Popkin BM. Changes in beverage intake between 1977 and 2001. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(3):205–210. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kit BK, Fakhouri TH, Park S, Nielsen SJ, Ogden CL. Trends in sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among youth and adults in the United States: 1999–2010. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(1):180–188. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.057943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malik VS, Pan A, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(4):1084–1102. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.058362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malik VS, Schulze MB, Hu FB. Intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(2):274–288. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.1.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mozaffarian D, Hao T, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Hu FB. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(25):2392–2404. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Despres J-P, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation. 2010;121(11):1356–1364. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.876185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulze MB, Manson JE, Ludwig DS et al. Sugar-sweetened beverages, weight gain, and incidence of type 2 diabetes in young and middle-aged women. JAMA. 2004;292(8):927–934. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ebbeling CB, Feldman HA, Chornitz VR et al. A randomized trial of sugar-sweetened beverages and adolescent body weight. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(15):1407–1416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lederer A, Curtis CJ, Silver LD, Angell SY. Toward a healthier city: nutrition standards for New York City government. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(4):423–428. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. New York City agency food standards. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/living/agency-food-standards.shtml. Accessed January 20, 2014.

- 11.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Healthy hospital food initiative. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/living/cardio-hospital-food-initiative.shtml. Accessed March 16, 2014.

- 12.Han E, Powell LM. Consumption patterns of sugar sweetened beverages in the United States. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(1):43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Van Wye G, Wallace C, Kilgore EA, et al. NYC CPPW-Obesity Media. Paper presented at the American Public Health Association Annual Meeting; October 29 to November 2, 2011; Washington, DC.

- 14.Nonas C, Silver LD, Kettel Khan L, Leviton L. Rationale for New York City’s regulations on nutrition, physical activity, and screen time in early child care centers. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E182. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Board of Health. Notice of adoption of an amendment to article 48 of the New York City Health Code. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/notice/2012/notice-adoption-amend-article48.pdf. Accessed January 20, 2014.

- 16.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Board of Health. Notice of adoption of an amendment to article 81 of the New York City Health Code. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/public/notice-adoption-hc-art81-50.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2014.

- 17.Dumanovsky T, Huang CY, Nonas CA, Matte TD, Bassett MT, Silver LD. Changes in energy content of lunchtime purchases from fast food restaurants after introduction of calorie labeling: cross sectional customer surveys. BMJ. 2011;343:d4464. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Labeling F. Nutrition labeling of standard menu items in restaurants and similar retail food establishments; proposed rule. Federal Register. 2011;76(66):19191–19236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Board of Health. Notice of adoption of an amendment (§81.53) to Article 81 of the New York City Health Code. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/notice/2012/notice-adoption-amend-article81.pdf. Accessed January 20, 2014.

- 20.Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Meengs JS. Larger portion sizes lead to a sustained increase in energy intake over 2 days. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:543–549. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ledikwe JH, Ello-Martin JA, Rolls BJ. Portion sizes and the obesity epidemic. J Nutr. 2005;135(4):905–909. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.4.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flood JE, Roe LS, Rolls BJ. The effect of increased beverage portion size on energy intake at a meal. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106(12):1984–1990. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brownell KD, Farley TA, Willett WC et al. The public health and economic benefits of taxing sugar-sweetened beverages. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1599–1605. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr0905723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hartocollis A. Failure of state soda tax plan reflects power of an antitax message. New York Times. July 3, 2010:A14.

- 25.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Removing SNAP subsidy for sugar-sweetened beverages: how New York City’s proposed demonstration project would work, and why the city is proposing it. 2010. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/cdp/cdp-snap-faq.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2014.

- 26.Andreyeva T, Luedicke J, Henderson KE, Tripp AS. Grocery store beverage choices by participants in federal food assistance and nutrition programs. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(4):411–418. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Community Health Survey, 2007–2013. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/data/survey.shtml. Accessed November 23, 2014.

- 28.New York City Departments of Health and Mental Hygiene and Education. New York City Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 2007–2013. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/data/youth-risk-behavior.shtml. Accessed November 23, 2014.