Abstract

Objectives. This study examined to what extent the higher mortality in the United States compared to many European countries is explained by larger social disparities within the United States. We estimated the expected US mortality if educational disparities in the United States were similar to those in 7 European countries.

Methods. Poisson models were used to quantify the association between education and mortality for men and women aged 30 to 74 years in the United States, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland for the period 1989 to 2003. US data came from the National Health Interview Survey linked to the National Death Index and the European data came from censuses linked to national mortality registries.

Results. If people in the United States had the same distribution of education as their European counterparts, the US mortality disadvantage would be larger. However, if educational disparities in mortality within the United States equaled those within Europe, mortality differences between the United States and Europe would be reduced by 20% to 100%.

Conclusions. Larger educational disparities in mortality in the United States than in Europe partly explain why US adults have higher mortality than their European counterparts. Policies to reduce mortality among the lower educated will be necessary to bridge the mortality gap between the United States and European countries.

The United States has lower life expectancy at birth than most Western European countries. In 2009, life expectancy in the United States was 76 years for men and 81 years for women, between 2 and 4 years less than in several European countries.1 The disadvantage is greater for women than for men and originated in the 1980s.2 The US health disadvantage is found not only for life expectancy, but also for self-reported health measures,3,4 biomarkers,3 and many specific causes of death5,6 across the entire life course.3–5,7

A recent report by the National Research Council suggests that smoking and obesity explain an important part of the US mortality disadvantage.2,8,9 However, an approach that solely emphasizes behavioral differences is impoverished by ignoring the role of socioeconomic and environmental determinants.10 A substantial body of research suggests that most behavioral risk factors are socially patterned; lower education or income are associated with a higher prevalence of smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, obesity, and poor dietary patterns.11–19 In addition, European countries and the United States differ in many aspects of the physical and social environment that can affect population health and that are in turn socially patterned within each country. For example, the socioeconomic distribution of access to healthy food differs between countries.20 Social environmental factors related to safety, violence, social connections, social participation, social cohesion, social capital, and collective efficacy have also been shown to influence health and in turn differ between countries and socioeconomic groups.21 Indeed, differences in mortality between the United States and Europe are larger among those with a lower educational level,6 suggesting that larger educational disparities in mortality, which partly coincide with differences in behavior, partly explain why Americans have higher mortality than Europeans.

The United States is characterized by relatively higher levels of income inequalities,22 residential and racial segregation,23–25 and financial barriers to health care access2,26 than any European country. Social protection policies and benefits are also less comprehensive in the United States than in Europe, including policies on early education and childcare programs,27 access to high-quality education,28 employment protection and support programs,29,30 and housing29,31 and income transfer programs.31,32 A plausible hypothesis is that the more unequal distribution of resources and less comprehensive policies contribute to the more unfavorable risk factor profile and poorer health of lower-educated Americans as compared with corresponding Europeans.4,33,34 A follow-up report by the National Research Council and the Institute of Medicine published in 2013 concluded that there is a lack of evidence on how these factors explain the US health disadvantage.21 The aim of this article is to assess to what extent larger educational disparities in mortality explain why Americans have higher mortality than Europeans.

METHODS

Data from 5 waves (1989–1993) of the US National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) were used.35 The NHIS is a survey of the noninstitutionalized population of the United States, with a 10-year mortality follow-up through linkage with the National Death Index. Our study focuses on ages 30 to 74 years. We excluded the population aged 75 years and older because previous evidence suggests that US mortality at these ages is similar or lower than that in other high-income countries.36,37 In addition, NHIS might underestimate mortality at older ages as a result of excluding the institutionalized population from their sample. Though rates of institutionalization are only around 1% at ages younger than 75 years, they are around 11% at older ages.38 Analyses by the National Center for Health Statistics have shown that NHIS survival rates closely resemble those of the general US population younger than 75 years.39 US data comprised 290 231 individuals aged 30 to 74 years at baseline and 28 935 deaths in the 10 years of mortality follow-up.

The European data came from the Eurothine project, in which census data from the early 1990s were linked to national mortality registries with a follow-up until the early 2000s for Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland.40 Data comprised entire national populations except data for France (which were based on a 1% representative sample of the French population excluding residents of overseas territories, members of the military, and students) and Switzerland (which excluded non-Swiss nationals). Table A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) shows details of the sample and follow-up in each country. Although most countries had a mortality follow-up of around 10 years, follow-up for Belgium and Denmark was 5 years. To account for differences in age at death because of these different lengths of follow-up, we included individuals aged 30 to 79 years at baseline for Belgium and Denmark, but ages 30 to 74 years for all other countries. Data included more than 20 million individuals and 1.6 million deaths.

We focused on mortality patterns by educational level, a key indicator of socioeconomic status. Data on mortality by education were available for all countries included, but data on mortality by occupational class or income were not available in most countries. Educational attainment was measured by years of completed schooling in the United States and by the highest level of educational attainment in Europe. Data were harmonized so that educational levels in both the United States and the European countries approximately correspond with levels as defined in the International Standard Classification of Education41 (ISCED). Based on this classification, education was reclassified into 3 levels: lower secondary or less education (≤ 11 years of schooling in the United States, ISCED levels 0 to 2), upper secondary education (12–15 years of schooling in the United States, ISCED levels 3 and 4), and tertiary or higher education (≥ 16 years of schooling in the United States, ISCED levels 5 and 6). Distributions of education in our data matched those in data from the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis/Vienna Institute of Demography provided by the World Bank (Table B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

We consider all-cause mortality as well as mortality from cancer, cardiovascular disease, other diseases, and external causes. Table C (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) provides the International Classification of Disease, 10th Revision codes for each cause of death.

Mortality rates for each country were estimated by Poisson regression models and were directly standardized to the US 1995 intercensal population. Then absolute and relative differences in mortality between the United States and each European country were calculated from these age-standardized rates. Additionally, country-specific rate ratios indicating the age-adjusted risk of mortality associated with lower educational attainment were obtained.

Thereafter, we combined the estimates from the Poisson model with the observed distribution of educational level in each country to obtain the expected US mortality under 3 scenarios. In the first scenario, we estimated what the US mortality rate would be if the United States had the same educational distribution as each European country. The second scenario estimated what the US mortality would be if the mortality risk associated with lower educational attainment in the United States would be the same as in each European country. In the third scenario, we estimated what the US mortality would be if the United States had both the distribution of education and mortality risk associated with lower educational attainment as each European country.

Because the US mortality disadvantage is greater among women than among men,2 this article only presents results for women. The results for men can be found in the supplemental material (Part II, Tables D–F and Figure A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

RESULTS

US women had higher levels of educational attainment than women in most European countries (Table 1). The percentage of women with lower secondary education or less ranged from 20% in the United States to 36% in Norway and 40% to 67% in all other European countries. The percentage of women with tertiary or more education ranged from 7% in Switzerland to 20% in Finland, whereas the United States ranked second highest with 19% (together with Denmark and Sweden).

TABLE 1—

Educational Distribution, Mortality Rates, and Mortality Rate Ratios for Women by Country: United States and 7 European Countries, 1989–2003

| Education Levela | United States | Belgium | Denmark | Finland | France | Norway | Sweden | Switzerland |

| Percentage | ||||||||

| Low | 20 | 67 | 53 | 51 | 62 | 36 | 41 | 40 |

| Mid | 61 | 19 | 28 | 29 | 28 | 47 | 40 | 53 |

| High | 19 | 14 | 19 | 20 | 10 | 17 | 19 | 7 |

| Mortality rate per 100 000 person-yearsb (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Low | 1023 (988, 1059) | 801 (796, 806) | 1037 (1029, 1046) | 794 (788, 799) | 530 (515, 544) | 801 (794, 808) | 657 (653, 661) | 657 (652, 662) |

| Mid | 766 (745, 786) | 628 (615, 641) | 814 (800, 829) | 631 (621, 641) | 387 (362, 412) | 616 (609, 624) | 534 (529, 539) | 523 (518, 528) |

| High | 529 (495, 564) | 582 (567, 597) | 664 (646, 683) | 528 (516, 539) | 334 (293, 375) | 484 (471, 497) | 402 (395, 410) | 472 (457, 487) |

| Total | 806 (789, 823) | 766 (761, 770) | 960 (953, 966) | 733 (728, 737) | 490 (478, 502) | 695 (690, 700) | 587 (584, 590) | 589 (586, 593) |

| Rate ratio (95% CI) | ||||||||

| Low | 1.93 (1.80, 2.08) | 1.38 (1.34, 1.41) | 1.56 (1.52, 1.61) | 1.50 (1.47, 1.54) | 1.58 (1.40, 1.80) | 1.66 (1.61, 1.70) | 1.63 (1.60, 1.67) | 1.39 (1.35, 1.44) |

| Mid | 1.45 (1.35, 1.55) | 1.08 (1.04, 1.11) | 1.23 (1.19, 1.27) | 1.20 (1.17, 1.23) | 1.16 (1.01, 1.33) | 1.27 (1.24, 1.31) | 1.33 (1.30, 1.36) | 1.11 (1.07, 1.15) |

| High (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Note. CI = confidence interval.

Low represents lower secondary or less education, mid represents upper secondary education, high represents tertiary or more education.

Rates have been directly standardized toward the US 1995 intercensal population (in deaths per 100 000 person-years).

Table 1 shows that US women had higher total mortality than women in all European countries except Denmark. Mortality differences for the total population, however, concealed large variations by educational level. Among women with lower secondary or less education, mortality rates were higher in the United States than in any European country except Denmark, which had similar rates as the United States. By contrast, higher-educated women in the United States had similar rates of mortality as higher-educated women in several European countries. Correspondingly, rate ratios of mortality by educational level were larger in the United States than in most European countries (low educated women: rate ratio [RR] = 1.93; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.80, 2.08; and mid educated women: RR = 1.45; 95% CI = 1.35, 1.55). International differences in educational distribution, mortality rates, and mortality rate ratios were also present among men; they followed the same pattern, but differences in mortality were smaller and less consistent (Table D).

Educational Disparities and US–Europe Mortality Differences

The first columns in Table 2 show the observed mortality rates and differences in mortality between the United States and each European country. US women had between 40 (Belgium) and 316 (France) more deaths per 100 000 person-years than their European counterparts. Subsequent columns show the estimated US mortality rate and differences between the United States and each European country under 3 scenarios. If the United States had the same educational distribution as the European countries (scenario 1), the US mortality disadvantage would be even larger than observed. For example, if US women would have the same educational distribution as French women, the United States would have 457 more deaths per 100 000 person-years than their French counterparts. This finding reflects the fact that US women had higher levels of educational attainment than women in most European countries (Table 1). A similar result was found for men (Tables D and E).

TABLE 2—

Mortality Disadvantage for US Women: United States and 7 European Countries, 1989–2003

| Observed |

Scenario 1: Expected With European Educational Distributionc |

Scenario 2: Expected With European Relative Risks of Mortality by Educationd |

Scenario 3: Expected With European Educational Distributionc and European Relative Risks of Mortality by Educationd |

|||||

| Countries | Mortality Ratea (95% CI) | US Mortality Disadvantageb (95% CI) | US Mortality Ratea (95% CI)f | US Mortality Disadvantageb (95% CI)f | US Mortality Ratea (95% CI)f | US Mortality Disadvantageb (95% CI)f | US Mortality Ratea (95% CI)f | US Mortality Disadvantageb (95% CI)f |

| United States | 806 (789, 823) | |||||||

| Belgium | 766 (761, 770) | 40 (23, 58) | 940 (928, 952) | 174 (162, 187) | 618 (610, 626) | −148 (−157, −139) | 705 (696, 714) | −61 (−71, −51) |

| Denmark | 960 (953, 966) | −154 (−171, −136) | 890 (879, 901) | −70 (−83, −57) | 710 (701, 719) | −250 (−262, −239) | 780 (770, 790) | −180 (−192, −168) |

| Finland | 733 (728, 737) | 73 (56, 91) | 914 (902, 926) | 181 (169, 194) | 666 (657, 675) | −67 (−77, −57) | 738 (729, 748) | 5 (−5, 15) |

| Francee | 490 (478, 502) | 316 (299, 333) | 947 (935, 959) | 457 (440, 473) | 665 (656, 674) | 175 (160, 189) | 781 (771, 791) | 291 (176, 306) |

| Norway | 695 (690, 700) | 111 (93, 128) | 866 (855, 877) | 171 (159, 183) | 742 (733, 751) | 47 (37, 58) | 796 (786, 806) | 101 (90, 112) |

| Sweden | 587 (584, 590) | 219 (202, 236) | 879 (868, 891) | 291 (281, 304) | 762 (752, 772) | 175 (165, 185) | 818 (808, 829) | 231 (220, 242) |

| Switzerland | 589 (586, 593) | 217 (199, 234) | 884 (873, 895) | 295 (283, 307) | 637 (629, 645) | 48 (39, 57) | 683 (674, 692) | 94 (85, 103) |

Note. CI = confidence interval.

Rates have been directly standardized toward the US 1995 intercensal population (in deaths per 100 000 person-years).

The observed or expected US mortality disadvantage is the absolute difference between the US standardized mortality rate and that of each Western European country (in deaths per 100 000 person-years).

The impact of differences in educational distribution was assessed by estimating the US mortality disadvantage if the educational distribution in the United States was replaced by that in each Western European country.

The impact of differences in educational inequalities in mortality was assessed by estimating the US mortality disadvantage if the educational disparities in mortality in the United States were replaced by those in each Western European country.

For each country except France the all-cause mortality rate is the sum of the cause-specific mortality rates. Because cause-specific mortality data are not available for the French population, the all-cause mortality rate is included in this table.

The CIs calculated for the expected US mortality rates and disadvantages were based on a Monte Carlo simulation assuming a normal distribution with 10 000 samples.

If the United States had the same relative risk of mortality associated with lower educational attainment as European countries (scenario 2), the US mortality disadvantage would be smaller than observed (Table 2). For example, if US women would have the same risk associated with lower educational attainment as women in Switzerland, the difference in mortality between the United States and Switzerland would be 48 deaths per 100 000 person-years, a much smaller difference than the observed 217 deaths per 100 000 person-years. The mortality advantage of the United States over Danish women would increase substantially if the United States had the same educational disparities in mortality as Denmark.

The more favorable educational distribution of the US population only partly compensates for the larger inequalities in mortality: if the United States had the educational distribution and the educational inequalities in mortality of European countries (scenario 3), the US mortality disadvantage would be smaller, except in the comparison with Sweden (Table 2). For example, the difference in mortality among American and Swiss women would be 94 instead of 217 deaths per 100 000 person-years in this scenario.

The results for scenario 2 suggest that larger educational disparities in mortality within the United States explained more than 100% of the mortality disadvantage with Belgian and Finnish women. They explained 78% ([217 – 48]/217) of the US mortality disadvantage with Swiss women, and 58%, 45%, and 20% of that with Norwegian, French, and Swedish women, respectively. For men, similar results were found (Table E).

Cause-Specific Results

The difference in mortality between the United States and each European country is disaggregated by broad causes of death in Table 3. For each cause of death, the first column shows the observed difference, which indicates that US women had a mortality disadvantage compared with most European countries for cancer, cardiovascular disease, and other diseases, but not for external causes. The next column shows the estimated difference if the United States had the same educational disparities in cause-specific mortality as the corresponding European country (scenario 2). Under this scenario, all cause-specific US mortality disadvantages would be reduced or even reversed, indicating that the mortality disadvantage is partly or wholly explained by larger educational disparities in mortality in the United States. For example, comparing the United States and Belgium, the US mortality disadvantage for cancer would be reversed from 27 to −16, for cardiovascular disease from 9 to −60, and for other diseases from 19 to −47. For external causes the US mortality advantage would increase from −15 to −25 per 100 000 person-years (negative values indicate higher mortality in Europe than in the United States).

TABLE 3—

Mortality Disadvantage for US Women by Cause of Death (Scenario 2): United States and 7 European Countries, 1989–2003

| All-Cause Mortality |

Cancer Mortality |

Mortality From Cardiovascular Disease |

Mortality From Other Diseases |

Mortality From External Causes |

||||||

| Countries | Observed US Mortality Disadvantagea (95% CI) | Expected US Mortality Disadvantageb (95% CI) | Observed US Mortality Disadvantagea (95% CI) | Expected US Mortality Disadvantageb (95% CI) | Observed US Mortality Disadvantagea (95% CI) | Expected US Mortality Disadvantageb (95% CI) | Observed US Mortality Disadvantagea (95% CI) | Expected US Mortality Disadvantageb (95% CI) | Observed US Mortality Disadvantagea (95% CI) | Expected US Mortality Disadvantageb (95% CI) |

| Belgium | 40 (23, 58) | −148 (−157, −139) | 27 (18, 37) | −16 (−37, 4) | 9 (0, 17) | −60 (−86, −34) | 19 (11, 28) | −47 (−69, −26) | −15 (−17, −12) | −25 (−29, −20) |

| Denmark | −154 (−171, −136) | −250 (−262, −239) | −79 (−88, −70) | −104 (−126, −81) | 8 (−1, 17) | −21 (−52, 11) | −67 (−75, −58) | −101 (−127, −75) | −16 (−18, −13) | −25 (−29, −20) |

| Finland | 73 (56, 91) | −67 (−77, −57) | 55 (45, 64) | 13 (−8, 33) | −23 (−32, −14) | −65 (−94, −35) | 64 (55, 72) | 12 (−12, 35) | −22 (−25, −19) | −26 (−32, −21) |

| Francec | 316 (299, 333) | 175 (160, 189) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Norway | 111 (93, 128) | 47 (37, 58) | 14 (4, 23) | −10 (−33, 12) | 33 (24, 42) | 25 (−8, 59) | 64 (56, 73) | 41 (14, 68) | 0 (−3, 2) | −9 (−14, −4) |

| Sweden | 219 (202, 236) | 175 (165, 185) | 44 (34, 53) | 27 (4, 50) | 73 (64, 81) | 68 (34, 102) | 106 (97, 114) | 89 (60, 117) | −3 (−5, 0) | −9 (−14, −3) |

| Switzerland | 217 (199, 234) | 48 (39, 57) | 48 (39, 58) | 10 (−11, 31) | 93 (84, 101) | 44 (15, 72) | 81 (73, 90) | 9 (−12, 30) | −5 (−8, −2) | −15 (−19, −10) |

Note. CI = confidence interval; NA = not available.

The US mortality disadvantage is the absolute difference between the US standardized mortality rate and that of each Western European country (in deaths per 100 000 person-years).

The impact of differences in educational inequalities in mortality was assessed by estimating the US mortality disadvantage (expected) in a scenario in which the educational disparities in mortality in the US were replaced by those in each Western European country.

Cause-specific mortality data are not available for the French population.

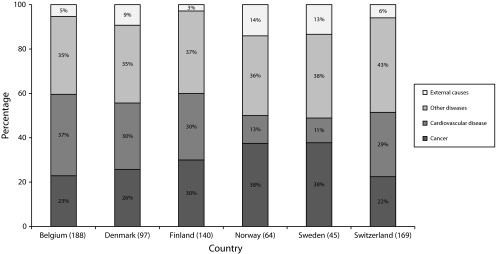

Figure 1 shows the contribution of causes of death to the change in US all-cause mortality disadvantage that would occur if the United States would have the same relative risks of cause-specific mortality associated with lower educational attainment as the European countries. As we have seen, and again taking cancer and Belgium as an example, this scenario would reverse the observed US disadvantage from 27 into an advantage of 16. In Figure 1, this change of 43 is expressed as a percentage of the change in US all-cause mortality disadvantage. Because the latter was 188 deaths per 100 000 person-years (a disadvantage of 40 would become an advantage of 148; Table 2), cancer accounted for 23% (43/188) of the change in all-cause mortality. Cardiovascular disease in the case of Belgium, cancer in the case of Norway and Sweden, and other diseases in the case of Finland and Switzerland made the largest contributions. In the case of Denmark, where this scenario increased the US all-cause mortality advantage, other diseases made the largest contribution as well. Corresponding results for men can be found in Table F and Figure A.

FIGURE 1—

Contribution of specific causes of death to the change in US mortality (dis)advantage for women: United States and 7 European Countries, 1989–2003.

Note. Numbers in parentheses indicate absolute change in all-cause mortality.

DISCUSSION

US women had higher mortality than women in all European countries included except Denmark. If American women had the same distribution of education as Europeans, differences in total mortality between the United States and Europe would be even larger, reflecting the fact that Americans had higher levels of educational attainment than Europeans. By contrast, if educational disparities in mortality within the United States were similar to those within European countries, mortality differences between the United States and European countries would be reduced by between 20% and 100%. This reflects the fact that the United States had larger educational disparities in mortality than European countries. A similar pattern was found for men. Although US men did not have the highest mortality, if educational disparities in mortality within the United States were similar to those within European countries, US mortality estimates would decrease. Larger educational disparities in mortality from cancer, cardiovascular disease, and other diseases all contributed substantially to the US mortality disadvantage.

Limitations

Cross-national differences in methods of data collection, baseline periods, follow-up periods, and population covered might have affected our mortality estimates. A key concern is that data for the United States excluded the institutionalized population (e.g., people living in nursing homes), while data for the European countries generally included the total population. Because institutionalized populations are less healthy than those living in the community, our estimates are likely to underestimate mortality differences between the United States and European countries. In sensitivity analyses, we tested the impact of this by restricting participants to ages 30 to 64 years, among whom institutionalization rates are relatively low. Results on the relative contribution of disparities to total mortality differences between countries were largely unchanged (results available upon request). Thus, although NHIS underestimates mortality for the United States by excluding the institutionalized population,39 this does not seem to bias estimates on the contribution of national disparities to cross-national mortality differences.

US men and women had higher levels of education than their European counterparts, which is supported by other sources, such as data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.42,43 In this study education in the United States was measured based on years of schooling, while in Europe it was based on ISCED highest educational attainment levels. Furthermore, educational systems, practices, curricula, and other aspects of education differ among countries.43,44 We therefore cannot exclude that part of the variation in educational disparities in mortality observed in our study is spurious, but differences between the United States and European countries (Table 1) appear too large to be only a result of differences in educational classification or educational systems.

A recent study by Ho45 and a related National Research Council report21 show that mortality from external causes among those younger than 50 years is higher in the United States than in European countries, except for Finnish men. In our data, mortality from external causes was in general lower in the United States than in Europe. This is partly attributed to the fact that our data cover a different and older age range than that covered by Ho.45 In addition, part of the difference might be attributed to the exclusion of the institutionalized population in the US NHIS (e.g., incarcerated individuals). We may therefore have somewhat underestimated the role of mortality from external causes in explaining US–Europe differences in all-cause mortality.

We did not consider race in our analyses because data for Europe did not include information on this variable. In the United States, large racial differences in mortality have been documented.46–50 In sensitivity analyses, we calculated the US mortality disadvantage under the 3 scenarios for US Whites and Blacks separately (Tables G–L). These results show that our general conclusion holds for both racial groups: educational disparities in mortality contribute substantially to the US mortality disadvantage for both US Blacks and Whites.

Interpretation

Previous reports suggest that smoking, obesity, and other proximal risk factors partly explain the US health disadvantage.2,8,9,21,51 Our results do not necessarily contradict those findings, because larger educational inequalities in mortality might also be attributed to larger inequalities in smoking, obesity, and similar downstream risk factors.2 Nevertheless, our results suggest that larger educational inequalities in mortality in the United States make a much more important contribution to the US mortality disadvantage than was previously known. While it is true that the US mortality disadvantage applies to all educational groups (Table 1), disparities are larger among those with lower educational attainment. This suggests that the exceptionally high mortality among least educated Americans to an important extent drives the US mortality disadvantage.

Possible explanations for larger educational inequalities in mortality in the United States than in Europe include larger inequalities in material circumstances (e.g., income), psychosocial stress, health behaviors (e.g., smoking), and access to high-quality medical care. Not only are income inequalities as such larger in the United States,52–54 but income differences between educational groups are also larger in the United States than in many European countries. The rate of return to schooling, that is the percentage change in wages because of an additional year of schooling, is larger in the United States than in Western Europe.55

Lower educational attainment is associated with higher levels of psychosocial stress,56,57 but whether this association is stronger in the United States than in Europe is unknown. One possible source of psychosocial stress could be work–family strain, that is the combination of job demand, job control, and social support, both from formal and informal sources. From 1950 onwards, female labor force participation has increased dramatically in both the United States and Western Europe, but this increase was largest for US women.58 Marriage rates differ across countries,59 as well as the level of formal and informal support available for working parents.60–62 High labor force participation, high fertility, low marriage rates, and the relative lack of proximity to extended family in the United States might partly contribute to the poorer health of US women as compared with their counterparts in European countries such as Sweden and Norway, where family support policies and systems are well established and widely available to women from all socioeconomic groups.

Health behaviors vary across educational groups63–65 and these variations might be larger in the United States than in Western Europe. Comparative studies are lacking, but in view of the fact that the smoking epidemic started earlier and reached a higher peak in the United States particularly among women, larger inequalities in smoking in the United States offer a potential explanation for larger educational disparities in mortality in the United States.12,63,66 In addition, obesity prevalence is higher, and educational disparities in obesity might be larger in the United States than in Europe.33,34A recent report reviewed evidence of differences in medical care and public health systems and concluded that medical care is not systematically of worse quality in the United States than in European countries.21,67,68 In addition, US survival rates for several chronic conditions contributing to the US health disadvantage, such as heart disease, ischemic stroke, and cancer, are better in the United States than in other high-income countries, suggesting that on average care for these conditions might not be worse in the United States than in European countries.21,67,69,70 However, inequalities in health care utilization might well be larger in the United States than in Europe,57,71 which might then still contribute to larger inequalities in mortality in the United States.70,72 A larger proportion of the lower-educated lack health insurance in the United States than in European countries, where health insurance coverage is more universal. Nevertheless, most of the differences in health between socioeconomic groups are likely because of factors outside the influence of medical care (e.g., poor health behaviors and material circumstances).73

Consistent with findings from previous studies, differences in mortality rates between the United States and several European countries were smaller and less consistent for men than for women.74 This finding has been attributed to gender differences in smoking patterns across countries and their lag effect on mortality.63,74 In the decades preceding our mortality observations smoking prevalence was similar in the United States and in several European countries among men, but higher in the United States than in most European countries among women. This might have contributed to a larger US mortality disadvantage among women. Other explanations have pointed to a possible role of weaker social protection policies to combine work and family responsibilities in the United States than in Europe, which if causally related to mortality, would affect women more than men.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, our study is the first to show that larger educational disparities in mortality in the United States make a substantial contribution to the gap in mortality between the United States and European countries. Despite similar or higher levels of educational attainment in the United States than in Europe in the cohorts examined, the mortality risk associated with lower educational attainment is larger in the United States than in most European countries, a pattern that contributes substantially to the US mortality disadvantage. These findings emphasize the potential benefit of policies to tackle health disparities in the United States. Although more evidence is required, the larger educational inequalities in mortality in the United States than in many European countries suggest that policies (within and outside the health sector) that address this inequality and the health of the most disadvantaged groups might contribute to improve overall population health in the United States.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Ageing (NIA; grant R01AG040248). Mauricio Avendano was additionally supported by the European Research Council (grant 263684), NIA (grant R01AG037398), and the McArthur Foundation Research Network on Ageing. The analysis reported in this article was based on data collected in the Eurothine study, financially supported by the Health and Consumer Protection Directorate (DG SANCO) of the European Commission (contract number 2003125).

We thank Members of the Eurothine consortium: Anita Lange (Statistics Denmark, Denmark) and Bjorn Heine Strand (Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Norway).

Note. The funding sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the article; and decision to submit the article for publication.

Human Participant Protection

Human participant protection was not required because only secondary, de-identified data were used.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global health observatory data repository. Global Health Observatory Data Repository. Available at: http://apps.who.int/ghodata/?vid=710. Accessed August 1, 2012.

- 2.Crimmins EM, Preston SH, Cohen B. International differences in mortality at older ages: Dimensions and sources. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. Panel on Understanding Divergent Trends in Longevity in High-Income Countries, National Research Council. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinson ML, Teitler JO, Reichman NE. Health across the life span in the United States and England. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(8):858–865. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banks J, Marmot M, Oldfield Z, Smith J. Disease and disadvantage in the United States and in England. JAMA. 2006;295(17):2037–2045. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nolte E, McKee CM. In amenable mortality—deaths avoidable through health care—progress in the US lags that of three European countries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(9):2114–2122. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Avendano M, Kok R, Glymour M . Do Americans have higher mortality than Europeans at all levels of the education distribution? A comparison of the United States and 14 European countries. In: Crimmins EM, Preston SH, Cohen B, editors. International differences in mortality at older ages: Dimensions and sources. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. pp. 313–332. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avendano M, Kawachi I. Invited commentary: the search for explanations of the American health disadvantage relative to the English. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(8):866–869. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Preston SH, Glei DA, Wilmoth JR. A new method for estimating smoking-attributable mortality in high-income countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(2):430–438. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Preston SH, Stokes A. Contribution of obesity to international differences in life expectancy. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(11):2137–2143. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bayer R, Fairchild AL, Hopper K, Nathanson CA. Confronting the sorry state of US health. Science. 2013;341(6149):962–963. doi: 10.1126/science.1241249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huisman M, Kunst AE, Mackenbach JP. Educational inequalities in smoking among men and women aged 16 years and older in 11 European countries. Tob Control. 2005;14(2):106–113. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.008573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavelaars AEJM, Kunst AE, Geurts JJM et al. Educational differences in smoking: international comparison. BMJ. 2000;320(7242):1102–1107. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7242.1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lantz PM, House JS, Lepkowski JM, Williams DR, Mero RP, Chen J. Socioeconomic factors, health behaviors, and mortality: results from a nationally representative prospective study of US adults. JAMA. 1998;279(21):1703–1708. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graham H, Hunt S. Women’s smoking and measures of women’s socio-economic status in the United Kingdom. Health Promot Int. 1994;9(2):81–88. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winkleby MA, Fortmann SP, Barrett DC. Social class disparities in risk factors for disease: eight-year prevalence patterns by level of education. Prev Med. 1990;19(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(90)90001-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galobardes B, Morabia A, Bernstein MS. Diet and socioeconomic position: does the use of different indicators matter? Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30(2):334–340. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.2.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith GD, Brunner E. Socio-economic differentials in health: the role of nutrition. Proc Nutr Soc. 1997;56(1A):75–90. doi: 10.1079/pns19970011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giskes K, Avendano M, Brug J, Kunst AE. A systematic review of studies on socioeconomic inequalities in dietary intakes associated with weight gain and overweight/obesity conducted among European adults. Obes Rev. 2010;11(6):413–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giskes K, van Lenthe F, Avendano-Pabon M, Brug J. A systematic review of environmental factors and obesogenic dietary intakes among adults: are we getting closer to understanding obesogenic environments? Obes Rev. 2011;12(5):e95–e106. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Black C, Moon G, Baird J. Dietary inequalities: what is the evidence for the effect of the neighbourhood food environment? Health Place. 2014;27(0):229–242. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woolf SH, Aron L. US Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013. Panel on Understanding Cross-National Health Differences Among High-Income Countries, National Research Council, Institute of Medicine. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Country note: United States. Growing Unequal?: Income Distribution and Poverty in OECD Countries. Paris, France: The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(5):404–416. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.5.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iceland J, Weinberg DH, Steinmetz E. Racial and Ethnic Residential Segregation in the United States 1980-2000. Washington, DC: Bureau of Census; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Denton NA, Massey DS. Residential segregation of Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians by socioeconomic status and generation. Soc Sci Q. 1988;69(4):797–817. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams PF, Dey AN, Vickerie JL. Summary health statistics for the US population: National Health Interview Survey, 2005. Vital Health Stat. 2007;10(233) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Education at a glance 2012: OECD indicators. Paris, France: The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Strong performers and successful reformers in education lessons from PISA for the United States. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Benefits and Wages: Statistics. 2012. Available at: http://www.oecd.org/els/socialpoliciesanddata/49971171.xlsx. Accessed August 1, 2012.

- 30.The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD indicators of employment protection. Available at: http://www.oecd.org/employment/protection. Accessed April 1, 2013.

- 31.The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Taxes and benefits. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 32.The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD.stat. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Avendano M, Glymour MM, Banks J, Mackenbach JP. Health disadvantage in US adults aged 50 to 74 years: a comparison of the health of rich and poor Americans with that of Europeans. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(3):540–548. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.139469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silventoinen K, Sans S, Tolonen H et al. Trends in obesity and energy supply in the WHO MONICA project. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28(5):710–718. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Minnesota Population Center and State Health Access Data Assistance Center. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota; 2012. Integrated Health Interview Series: version 5.0. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manton KG, Vaupel JW. Survival after the age of 80 in the United States, Sweden, France, England, and Japan. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(18):1232–1235. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511023331824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ho JY, Preston SH. US mortality in an international context: age variations. Popul Dev Rev. 2010;36(4):749–773. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2010.00356.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.US Bureau of the Census. General population characteristics. US 1990 Census of Population. 1992:CP-1–1. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ingram DD, Lochner KA, Cox CS. Mortality experience of the 1986-2000 National Health Interview Survey linked mortality files participants. Vital Health Stat. 2008;2(147) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mackenbach JP, Stirbu I, Roskam AR et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in health in 22 European countries. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(23):2468–2481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0707519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. UNESCO. International standard classification of education: ISCED 1997. International standard classification of education: ISCED 1997. Available at: http://www.unesco.org/education/information/nfsunesco/doc/isced_1997.htm. Accessed July 1, 2013.

- 42.Lutz W, Goujon A, KC S, Sanderson W. Reconstruction of populations by age, sex and level of educational attainment for 120 countries for 1970-2000. Vienna Yearb Popul Res. 2007;5:193–235. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Education at a glance 1998. Paris, France: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Allmendinger J. Educational systems and labor market outcomes. Eur Sociol Rev. 1989;5(3):231–250. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ho JY. Mortality under age 50 accounts for much of the fact that US life expectancy lags that of other high-income countries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(3):459–467. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harper S, Lynch J, Burris S, Davey Smith G. Trends in the black-white life expectancy gap in the United States, 1983-2003. JAMA. 2007;297(11):1224–1232. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.11.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adler NE, Rehkopf DH. US disparities in health: Descriptions, causes and mechanisms. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:235–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Howard G, Anderson RT, Russell G, Howard VJ, Burke GL. Race, socioeconomic status and cause-specific mortality. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10(4):214–223. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Geronimus AT, Bound J, Waidmann TA, Hillemeier MM, Burns PB. Excess mortality among Blacks and Whites in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(21):1552–1558. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199611213352102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sorlie PD, Backlund E, Keller JB. US mortality by economic, demographic, and social characteristics: The National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Am J Public Health. 1995;85(7):949–956. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.7.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crimmins EM, Preston SH, Cohen B. Explaining Divergent Levels of Longevity in High-Income Countries. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. Panel on Understanding Divergent Trends in Longevity in High-Income Countries. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alesina A, Angeletos G. Fairness and redistribution. Am Econ Rev. 2005;95(4):960–980. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Atkinson A. Income distribution in Europe and the United States. Oxf Rev Econ Pol. 1996;12(1):15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gottschalk P, Smeeding TM. Cross-national comparisons of earnings and income inequality. J Econ Lit. 1997;35(2):633–687. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trostel P, Walker I, Woolley P. Estimates of the economic return to schooling for 28 countries. Labour Econ. 2002;9(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Adler NE, Boyce T, Chesney MA et al. Socioeconomic status and health: The challenge of the gradient. Am Psychol. 1994;49(1):15–24. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.49.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baum A, Garofalo JP, Yali AM. Socioeconomic status and chronic stress: Does stress account for SES effects on health? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;896(1):131–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alesina AF, Glaeser EL, Sacerdote B. Work and leisure in the US and Europe: why so different? In: Gertler M, Rogoff K, editors. NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2005. Vol 20. MIT Press; 2006. pp. 1–100. [Google Scholar]

- 59. United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World marriage data 2008. World Marriage Data 2008. Available at: http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/WMD2008/WP_WMD_2008/Data.html. Accessed December 1, 2012.

- 60.Gauthier AH. Comparative family policy database, version 3 [computer file]. Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute and Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (distributors) Available at: http://www.demogr.mpg.de. Accessed December 1, 2012.

- 61.Tanaka S. Parental leave and child health across OECD countries. Econ J. 2005;115(501):F7–F28. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ruhm CJ, Teague JL. Parental leave policies in Europe and North America. NBER. 1995 Working Paper No. 5065. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pampel F. Divergent patterns of smoking across high-income nations. In: Crimmins E, Preston S, Cohen B, editors. International Differences in Mortality at Older Ages: Dimensions and Sources. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. pp. 132–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pampel FC. Diffusion, cohort change, and social patterns of smoking. Soc Sci Res. 2005;34(1):117–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.French DJ, Jang S, Tait RJ, Anstey KJ. Cross-national gender differences in the socioeconomic factors associated with smoking in Australia, the United States of America and South Korea. Int J Public Health. 2013;58(3):345–353. doi: 10.1007/s00038-012-0430-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhu BP, Giovino GA, Mowery PD, Eriksen MP. The relationship between cigarette smoking and education revisited: Implications for categorizing persons’ educational status. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(11):1582–1589. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.11.1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Preston SH, Ho JY. Low life expectancy in the United Sates: is the health care system at fault? In: Crimmins E, Preston S, Cohen B, editors. International Differences in Mortality at Older Ages: Dimensions and Sources. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. pp. 259–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wolf-Maier K, Cooper RS, Kramer H et al. Hypertension treatment and control in five European countries, Canada, and the United States. Hypertension. 2004;43(1):10–17. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000103630.72812.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Coleman MP, Quaresma M, Berrino F et al. Cancer survival in five continents: a worldwide population-based study (CONCORD) Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(8):730–756. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70179-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gatta G, Capocaccia R, Coleman MP et al. Toward a comparison of survival in American and European cancer patients. Cancer. 2000;89(4):893–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Van Doorslaer E, Masseria C, Koolman X for the OECD Health Equity Research Group. Inequalities in access to medical care by income in developed countries. CMAJ. 2006;174(2):177–183. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sant M, Allemani C, Berrino F et al. Breast carcinoma survival in Europe and the United States. Cancer. 2004;100(4):715–722. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Marmot M, Allen J, Bell R, Bloomer E, Goldblatt P. WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. Lancet. 2012;380(9846):1011–1029. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Preston SH, Glei DA, Wilmoth JR. Contribution of smoking to international differences in life expectancy. In: Crimmins EM, Preston SH, Cohen B, editors. International Differences in Mortality at Older Ages: Dimensions and Sources. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. pp. 105–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]