Abstract

US infant death rates for 1960 to 1980 declined most quickly in (1) 1970 to 1973 in states that legalized abortion in 1970, especially for infants in the lowest 3 income quintiles (annual percentage change = −11.6; 95% confidence interval = −18.7, −3.8), and (2) the mid-to-late 1960s, also in low-income quintiles, for both Black and White infants, albeit unrelated to abortion laws. These results imply that research is warranted on whether currently rising restrictions on abortions may be affecting infant mortality.

As restrictions increase on access to abortion in the United States,1,2 it is timely to revisit and build on previous research that examined whether US infant mortality rates were affected by 1960s and 1970s policies that expanded access to abortion.3–8 Consistent with a reproductive justice framework,9,10 we hypothesized that between 1960 and 1980, the steepest annual percentage declines in the infant death rate would occur among US states that legalized abortion in 1970, relative to states that decreased restrictions or kept abortion strictly illegal prior to national legalization of abortion in 1973,11 with the largest changes for infants born in low-income counties. A corollary was that state abortion law status would be less associated with mid- to late-1960s declines in infant mortality attributed by previous research6,12–19 to beneficial economic and social changes spurred by passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and by the War on Poverty,20,21 especially among low-income infants, both Black and White.

METHODS

We computed the infant death rate ([deaths < age 1 year]/[population < age 1 year] in the same calendar year)22 from 1960 to 196723 and 1968 to 198022 US national mortality data. We stratified the individual-level mortality records and census denominator data by age, gender, and race/ethnicity and aggregated them to the county level.

We classified states into 3 groups: (1) abortion legalized in 1970 (n = 4; Alaska, Hawaii, New York, Washington), (2) a model penal code enacted between 1967 and 1972 that, as stated at the time, reformed (i.e., made less stringent but did not repeal) the state’s abortion laws (n = 14; California, Colorado, New Mexico, Oregon, Maryland, Delaware, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Arkansas, Virginia, Kansas, Vermont, Florida), and (3) abortion kept illegal prior to Roe v Wade (the remaining 32 states plus the District of Columbia).3,4,8,11,24

Because the mortality data contained no socioeconomic information,18 we linked these data to county median family income obtained from US Census decennial 1960 to 1980 data (missingness < 1%), which we adjusted for inflation and regional cost of living.18,25 For Alaska, which has a small population and lacks county divisions, we analyzed data as 1 county.18 We used linear interpolation for intercensal years and then assigned counties to income quintiles, weighted by county population size, which varies greatly.18

The only racial/ethnic categories available were White and non-White for 1960 to 1967 and White, Black, and other for 1968 to 1980.18,22,23 For the 1960 to 1967 data, we followed standard practice by reclassifying non-White persons as Black.15 This approach is reasonable because in 1960, 92% of US non-White persons were Black, and the mortality rates of these 2 groups were almost identical.15 One state (New Jersey) did not identify race/ethnicity in 1962 and 1963, precluding use of its data for those 2 years (< 3% of the US population).23

We first computed and plotted the 3-year moving average of the infant death rates, stratified by state legal status and income quintile, for the total US, Black, and White population. We then analyzed time trends through joinpoint analyses,18,26,27 according to the annual count and corresponding denominator data. The joinpoint algorithm employs a grid search method to fit a segmented regression function and enables estimation of both the annual percentage change (APC) in rates and the inflection points where the slope of the APC significantly changes (P < .05).26,27

RESULTS

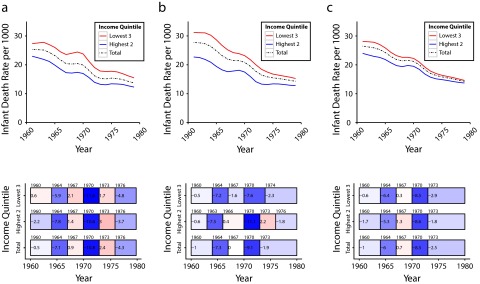

Figure 1 shows infant death rates for 1960 to 1980 for the total US population, overall and by county median family income quintile, in 3 sets of states, stratified by legal status of abortion. In all 3 sets of states, the fastest decline in rates, as measured by the APC, occurred between 1970 and 1973; these declines were evident in the bottom 3 and top 2 income quintiles, and the largest decline occurred in the lowest 3 income quintiles in the states that legalized abortion (APC = −11.6; 95% confidence interval [CI] = −18.7, −3.8; Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

FIGURE 1—

US infant death rates by county income quintile for the total US population (3-y moving average) and joinpoint analysis of annual percentage change in rates, stratified by (a) abortion legalized in 1970, (b) abortion law reformed between 1967 and 1972, and (c) abortion kept illegal: 1960–1980.

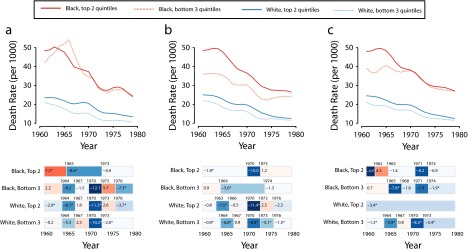

The only other period in which declines in the APC occurred in both income strata was in the mid-to-late 1960s; these declines were smaller and did not vary by state abortion law status (Figure 1; Table A) and were especially evident for Black and White infants in the lowest 3 income quintiles (Figure 2; Table B, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org).

FIGURE 2—

US infant death rates by county income quintile for the Black and White population (3-y moving average) and joinpoint analysis of annual percentage change in rates, stratified by (a) abortion legalized in 1970, (b) abortion law reformed between 1967 and 1972, and (c) abortion illegal: 1960–1980.

DISCUSSION

Our descriptive analysis newly extends and integrates previous strands of research that separately examined US trends in infant mortality rates in the 1960s and 1970s in relation to legalization of abortion,3–8 abolition of Jim Crow laws,12–14,19 and the War on Poverty.6,15,17,18

Presenting a reverse mirror to present-day rising restrictions on abortion rights,1,2 conjoined with rising economic inequality28,29 and voter intimidation,30,31 the results imply that research is warranted on how currently rising restrictions on abortions1,2 may be affecting US infant mortality rates and racial/ethnic and economic inequities in these rates.32–34

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (grant 5R21CA168470-02 to N. Krieger and 2P01CA134294-06 to X. Lin).

Note. The National Institutes of Health had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the article; and decision to submit the article for publication.

Human Participant Protection

Because our analyses are based solely on publicly available de-identified preexisting coded data aggregated to the US county level, our study was exempted from institutional review board review by the Harvard School of Public Health human subjects committee.

References

- 1.Dreweke J. US abortion rate continues to decline while debate over means to the end escalates. Guttmacher Policy Rev. 2014;17:2–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gee A. Anti-abortion laws gain more ground in the USA. Lancet. 2011;377(9782):1992–1993. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60848-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roemer R. Abortion law reform and repeal: legislative and judicial developments. Am J Public Health. 1971;61(3):500–509. doi: 10.2105/ajph.61.3.500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sklar J, Berkov B. Abortion, illegitimacy, and the American birth rate. Science. 1974;185(4155):909–915. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4155.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grossman M, Jacobwitz S. Variations in infant mortality rates among counties of the United States: the roles of public policies and programs. Demography. 1981;18(4):695–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller CA. Infant mortality in the US. Sci Am. 1985;253(1):31–37. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0785-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McFarlane DR, Meier KJ. The Politics of Fertility Control: Family Planning and Abortion Policies in the American States. New York, NY: Chatham House Publishers; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bitler M, Zavodny M. Did abortion legalization reduce the number of unwanted children? Evidence from adoptions. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2002;34(1):25–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silliman J, Fried MG, Ross L, Gutierrez ER. Undivided Rights: Women of Color Organize for Reproductive Justice. Cambridge, MA: South End Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sistersong: Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective. What is reproductive justice. Available at: http://www.sistersong.net/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=141&Itemid=81. Accessed August 31, 2014.

- 11.Gordon L. The Moral Property of Women: A History of Birth Control Politics in America. 3rd ed. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chay KY, Greenstone M. The convergence in Black-White infant mortality rates during the 1960’s. Am Econ Rev. 2000;90(2):326–332. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Almond DV, Chay KY, Greenstone M. Civil rights, the war on poverty, and Black-White convergence in infant mortality in the rural South and Mississippi. MIT economics working paper 07-04. 2006. Available at: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=961021. Accessed August 31, 2014.

- 14.Almond D, Chay KY. The long-run and intergenerational impact of poor infant health: evidence from cohorts born during the Civil Rights era. Working paper. 2008. Available at: http://users.nber.org/∼almond/chay_npc_paper.pdf. Accessed August 31, 2014.

- 15.Kitagawa EM, Hauser PM. Differential Mortality in the United States: A Study in Socioeconomic Epidemiology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis K, Schoen C. Health and the War on Poverty: A Ten-Year Appraisal. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh GK, Kogan MD. Persistent socioeconomic disparities in infant, neonatal, and postneonatal mortality rates in the United States, 1969–2001. Pediatrics. 2007;119(4):e928–e939. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krieger N, Rehkopf DH, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Marcelli E, Kennedy M. The fall and rise of inequities in US premature mortality: 1960–2002. PLoS Med. 2008;5(2):e46. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krieger N, Chen JT, Coull B, Waterman PD, Beckfield J. The unique impact of abolition of Jim Crow laws on reducing inequities in infant death rates and implications for choice of comparison groups in analyzing societal determinants of health. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(12):2234–2244. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fairclough A. Better Day Coming: Blacks and Equality, 1890–2000. New York, NY: Viking; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Connor A. Poverty Knowledge: Social Science, Social Policy, and the Poor in Twentieth-Century U.S. History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Center for Health Statistics. Compressed mortality file: years 1968–1978 with ICD-8 codes, 1979–1988 with ICD-9 codes and 1999–2010 with ICD-10 codes. Available at: http://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/help/cmf.html. Accessed August 31, 2014.

- 23.National Office of Vital Statistics. Documentation of the Detail Mortality Tape File (1959–1961, 1962–1967) Washington, DC: Public Health Service; 1969. Available at: http://www.nber.org/mortality/1965/mor59_67.pdf. Accessed August 31, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merz JF, Klerman JA, Jackson CA. A Chronicle of Abortion Legality, Medicaid Funding, and Parental Involvement Laws, 1967–1994. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 1996. DRU-1415-NIA/NICHD. Available at: http://www.rand.org/pubs/drafts/DRU1415.html. Accessed August 31, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.US Dept of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer price indexes. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/cpi/home.htm. Accessed August 31, 2014.

- 26. Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates [published correction appears in Stat Med. 2001;20(4):655]. Stat Med. 2000;19(3):335–351. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.National Cancer Institute. Joinpoint regression program version 4.1.0. 2014. Available at: http://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint. Accessed July 7, 2014.

- 28.Sommeiller E, Price M. The Increasingly Unequal States of America: Income Inequality by State, 1917 to 2011. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute; 2014. Available at: http://www.epi.org/publication/unequal-states. Accessed August 31, 2014.

- 29. Piketty T. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Goldhammer A, trans. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2014.

- 30. Project Vote. Legislative brief: 2010 issues in election administration. Voter intimidation and caging. Available at: http://projectvote.org/images/publications/2010%20Issues%20in%20Election%20Administration/2010%20Legislative%20Brief%20-%20Voter%20Intimidation%20and%20Caging.pdf. Accessed August 31, 2014.

- 31.Our Work is Not Done: A Report by the National Commission on Voting Rights. Washington, DC: Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law; 2014. Available at: http://votingrightstoday.org/ncvr/resources/discriminationreport. Accessed August 31, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Christopher G, Simpson P. Improving birth outcomes requires closing the racial gap. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(suppl 1):S10–S12. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.David RJ, Collins JW. Layers of inequality: power, policy, and health. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(suppl 1):S8–S10. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gruskin S. Safeguarding abortion: a matter of reproductive rights. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(1):4. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]