Abstract

Describing, evaluating, and conducting research on the questions raised by comparative effectiveness research and characterizing care delivery organizations of all kinds, from independent individual provider units to large integrated health systems, has become imperative. Recognizing this challenge, the Delivery Systems Committee, a subgroup of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Effective Health Care Stakeholders Group, which represents a wide diversity of perspectives on health care, created a draft framework with domains and elements that may be useful in characterizing various sizes and types of care delivery organizations and may contribute to key outcomes of interest. The framework may serve as the door to further studies in areas in which clear definitions and descriptions are lacking.

Recent and ongoing innovation in systems for the delivery and reimbursement of health care in the United States have broadened stakeholders’ need for standardized methods to describe, measure, compare, and evaluate delivery system changes. A common taxonomy of delivery system characteristics would allow for improved communication and transparency regarding these changes, potentially enhancing the quality of decisions and care for patients, providers, researchers, policymakers, payers, and other stakeholders.1–5 The comparative effectiveness of delivery system characteristics is ranked as a top priority by the Institute of Medicine, which has defined comparative effectiveness research (CER) as “the generation and synthesis of evidence that compares the benefits and harms of alternative methods to prevent, diagnose, treat, and monitor a clinical condition or to improve the delivery of care.”6(p203) Yet, there is no standard way to describe care delivery units or systems that encompasses their breadth, ranging from independent individual provider units to large integrated health systems.7 Thus, the absence of a common parlance for describing delivery systems hinders stakeholders from determining the generalizability of a study or an innovation introduced in 1 setting. The effectiveness of an intervention may be quite different depending on whether the setting is a large integrated care system or a small independent practice and whether providers are paid on production or salaried. We propose a preliminary framework for description of health care delivery systems that will allow health care stakeholders to better understand, evaluate, disseminate, and implement delivery system innovation in a more informed, transparent, and stakeholder-centered fashion and permit comparisons among them. Our objective is to present the domains and elements of the framework, the methods that were used to derive it, and examples of its potential application in diverse settings.

METHODS

Our proposal builds on previous taxonomic descriptions of the US health care system. In response to the increasing complexity and heterogeneity of health care delivery systems, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) funded development of a taxonomy of organizations, categorized by shared structural and strategic elements.8 The resulting taxonomy8 categorized 70% of health networks and 90% of health systems into clusters using 3 dimensions—differentiation, integration, and centralization—and applied the same dimensions to hospital services, physician arrangements, and provider-based insurance activities. In 2004, the taxonomy was updated to include a redefinition of centralization and updated descriptors of health care systems because of the continued evolution of organizations.9,10

In 2006, Luke11 noted that taxonomies derived from local systems were not appropriate for large multihospital systems and recommended that further taxonomic studies were needed. Subsequent taxonomic approaches broadened the role of a systems approach, giving primacy to the interrelationships, not to the elements of the system alone.12,13

The pieces (elements) of the framework we describe will certainly become further complex as organizations other than medical care groups (e.g., public health agencies) enter the arena of health care delivery. Rather than describe the lack of an element in a specific organization, one must consider the integration of other organizations bringing the missing elements with them. In parallel to the work of Bazzoli et al.10 and Luke,11 Mays et al.14 concurrently described methodology to classify and compare public health systems on the basis of elements of organization and defined 7 configurations with 3 tiers on the basis of their level of differentiation. Also paralleling Bazzoli et al.,10 Mays et al.14 found that public health systems were in a state of fluidity from 1998 to 2006.

Fragmentation

The escalating complexity and heterogeneity of health care delivery systems has led to increased fragmentation of how and where health care is delivered and has created new and often ill-defined relationships between fragments. The Commonwealth Fund Commission on a High Performance Health System has described traditional health care in the United States as a cottage industry wherein fragmentation occurs at the federal, state, and local levels.15 Fragmentation can contribute to unnecessary, redundant utilization and poorer quality of care.

Recognizing the challenges of a complex, dynamic, and often fragmented health care delivery system, the AHRQ’s Effective Health Care Stakeholders Group (SG) decided to draft an updated framework for describing health care delivery systems, with domains and elements that might be useful for characterizing various sizes and types of care delivery organizations.

The SG was a part of AHRQ’s Community Forum initiative, funded by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, to formally and broadly engage stakeholders and to enhance and expand public involvement in its entire Effective Health Care Program. Nomination of individuals for the SG occurred via a public process (a Federal Register notice) and was broadly inclusive. A committee composed of representatives from AHRQ reviewed all nominations and selected stakeholders to represent a diversity of perspectives, expertise, geographical locations, gender, and race/ethnicity. The group represented broad constituencies of stakeholders including patients, caregivers, and advocacy groups; clinicians and professional associations; hospital systems and medical clinic providers; government agencies; purchasers and payers; and health care industry representatives, policymakers, researchers, and research institutions.

The Delivery Systems Committee (DSC), a subgroup of the SG, consisted of 7 members including clinicians, policymakers, patient advocates, and researchers who were involved with a variety of care delivery organizations and represented diverse perspectives. The DSC convened to address a specific objective of interest to AHRQ: to develop guidance for AHRQ on how to approach CER on health delivery organizations and systems by developing a framework that could be used to characterize potentially important differences in structure and function. DSC discussions were facilitated by 2 members of the AHRQ Community Forum. All meetings were attended by at least 1 AHRQ staff member who provided feedback. The charges of both the SG and the DSC are detailed in the box below.

Charges of the Stakeholder Group and the Delivery Systems Committee in Developing a Framework to Describe Health Care Delivery Organizations and Systems

| Stakeholder Group | Delivery Systems Committee |

| Provide guidance on program implementation, including | How to compare different ways of delivering care, including to subpopulations |

| 1. Quality improvement, | |

| 2. Opportunities to maximize impact and expand program reach, | |

| 3. Ensuring stakeholder interests are considered and included, and | |

| 4. Evaluating success | |

| Provide input on implementing Effective Health Care Program reports and findings in practice and policy settings. | What are the ingredients or elements needed for comparison of ways to deliver care? |

| Identify options and recommend solutions to issues identified by Effective Health Care Program staff. | Can those elements be examined across delivery organizations and systems to get a sense of what works best for patients? |

| Provide input on critical research information gaps for practice and policy, as well as research methods to address them. Specifically, | What components of delivery organizations and systems do researchers need to |

| 1. Information needs and types of products most useful to consumers, clinicians, and policymakers; | 1. Identify and elaborate, and |

| 2. Feedback on Effective Health Care Program reports, reviews, and summary guides; | 2. Relate to the patient-centered outcomes that are most important? |

| 3. Scientific methods and applications; and | |

| 4. Champion objectivity, accountability, and transparency in the Effective Health Care program. |

The DSC’s initial work focused on defining the basic unit of consideration: the health care organization or system. Common definitions for health care delivery systems generally refer to all the components providing health care in a country or locality. For example, the World Health Organization16 has defined a health system as all organizations, people and actions whose primary intent is to promote, restore or maintain health. The framework presented here is meant to be broadly descriptive. Toward that end, the DSC developed an elements framework with 28 key elements grouped by 6 domains that characterize organizations and delivery systems and may contribute to key outcomes of interest. The DSC tested the framework for face validity among SG stakeholders representing a broad variety of systems of care.

For the purposes of this article, we defined a health care delivery system as the organization of people, institutions, and resources to deliver health care services to meet the health needs of a target population, whether a single-provider practice or a large health care system.

Approach

For each step in the development of the framework, the DSC used 2 approaches: review of the literature and the Delphi method, including facilitated group discussions and iterative rounds of individual written feedback on successive drafts of the framework. Descriptions of conflict and resolution were recorded in detailed meeting notes and in framework drafts, preserving an audit trail.

Although the DSC (at face-to-face meetings) did prioritization exercises, substantial discussion occurred by e-mail and in conference calls, which resulted in additional edits and revisions to the framework. The richness of those discussions contributed significantly to the final product. Each step of the process involved all 3 methods: literature review, facilitated group discussions, and synthesis of individual written feedback.

Process

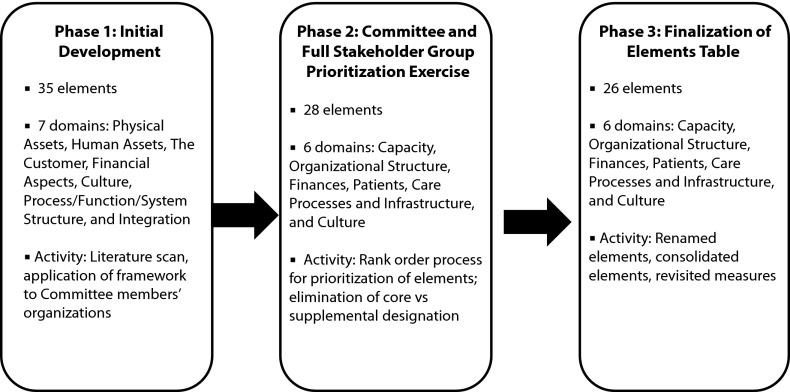

The DSC initially constructed a framework consisting of elements of health care organizations, focusing on outcomes of interest broadly defined as quality, cost, equity, and patient centeredness. Next, it identified several common medical conditions, for example, diabetes, as basic examples for developing the list of elements relevant to outcomes for the selected conditions. These elements were grouped into domains on the basis of commonalities, with the resulting framework initially consisting of 30 elements categorized according to 4 domains: structure, resources, culture, and function–process. A reiterative process initially resulted in 35 elements housed in 7 domains: physical assets, human assets, the customer, financial aspects, culture, process–function–system structure, and integration, with each element assigned to 1 domain only.

Each member applied the framework to the delivery system with which they were most familiar to test its goodness of fit. Comments from this validation exercise were used to further reorganize the framework into 26 elements in 6 domains: capacity, organizational structure, finances, patients, care processes and infrastructure, and culture. The model of these processes is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1—

Delivery systems methods flowchart of the creation of a draft framework to describe health care delivery organizations and systems.

The full SG was subsequently asked to provide feedback regarding the domains, elements, and definitions and to prioritize the elements. Feedback from the SG included 2 primary recommendations. First, it was valuable to have the full set of elements available rather than to eliminate elements or designate a core set of measures. On the basis of this feedback, the DSC decided to allow future users of the framework to select elements relevant to their individual application of the framework. Second, the SG recommended including both examples of the application of each element and information about measurability of each element. The DSC responded to these suggestions by adding more information about measurability, including (1) whether the element is feasible to measure and, if so, providing examples of instruments or formats for this measurement and (2) whether the measure of the element involves description or increasing value (i.e., is more better?). The DSC decided to use both generic and specific instruments, when possible, for measurement of the elements, with the understanding that additional instruments may currently exist or be developed.

RESULTS

The elements of the framework were divided into 6 domains and their respective elements. Descriptions of the elements and potential examples of possible measures are presented in Table 1, and summarized here.

1. Capacity: the physical assets and their ownership, personnel, and organizational characteristics of a delivery system that determine the number of individuals and breadth of conditions for which the system can provide care. Elements include size, capital assets, and comprehensiveness of services.

2. Organizational structure: the components of an organization, both formal and informal, that describe functional operations in terms of hierarchy of authority and the flow of information, patients, and resources. Elements include organizational configuration; leadership, structure, and governance; research and innovation; and professional education.

3. Finances: mechanisms by which a health care delivery system is paid for its services and the financial arrangements and practices of the system and organizations within the system to allocate those funds, as well as the system’s financial status. Elements include payment received for services, provider payment systems, ownership, and financial solvency.

4. Patients: demographic characteristics, as well as wants, needs, and preferences of individuals and families of individuals who receive health care services from a health care delivery system. Elements include patient characteristics and geographic characteristics.

5. Care processes and infrastructure: the methods by which a health care delivery system provides health care services to its customers and patients as well as the degree of coordination of those methods. Elements include integration, standardization, performance measurement, public reporting, quality improvement, health information systems, patient care teams, clinical decision support, and care coordination.

6. Culture: The long-standing, largely implicit shared values, beliefs, and assumptions that influence behavior, attitudes, and meaning in an organization.21 Elements include patient centeredness, cultural competence, competition–collaboration continuum, community benefit, and innovation diffusion and working climate.

TABLE 1—

Description of Framework Domains and Elements, With Examples of Possible Measures

| Domain/Element | Description | Measures (Illustrative Examples) |

| I. Capacity (physical and human assets) | ||

| Size | The system’s productive capacity | Metrics of scale, such as number of clinicians, number of beds, number of outpatient encounters, number of patients served |

| Metrics of output, such as number of patient encounters in a time period | ||

| Capital assets | The property, facilities, physical plant and the property’s ownership, equipment, and other infrastructure used to provide and manage health care services | Number and type of facilities |

| Additional considerations that affect the assets, such as facility and equipment age, accessibility, cost, depreciation | ||

| Comprehensiveness of services | The scope and depth of services available in terms of setting, specialty, ancillary services, and acuity of care | Scope of settings in which care is provided, such as hospital, home, clinic, nursing home, rehabilitation facility, hospice |

| Scope and number of care providers, such as primary care, specialty, and subspecialty (e.g., medical, surgical, behavioral health, palliative care) | ||

| Scope and number of providers of ancillary services, categorized as diagnostic, therapeutic, and custodial (based on a standard list of ancillary services) | ||

| Scope of services provided, such as preventive, acute, chronic, long term, hospice, and rehabilitation | ||

| II. Organizational structure | ||

| Configuration | The arrangement of the functional units in the system in terms of workflow, hierarchy of authority, patterns of communication, and resource flows among them | Diagrams of nodes or functional units and directional lines serving as links between units for any type of interaction–resource flow, communication, or instruction |

| Social network analysis to calculate indices from a matrix of linkages among the units, such as the centrality of any node in the network, the centralization of the network, or the density of interactions | ||

| Leadership structure and governance | The level of formal decision-making authority for an office holder in terms of the scope of decisions that can be made independently and with concurrence of others | Formal organizational authority, measured by hierarchical level and the scope of decisions at that level |

| Power and influence, determined by the interdependencies between units for critical resources, such as the ratio of resources provided to the total, and the ratio of resources received to the total | ||

| Research and innovation | The extent to which participation in clinical and basic scientific research and health care innovation is a feature of the mission and activities of the organization | Ratio of research activity to clinical activity or total activity on a variety of dimensions |

| The number of innovative processes, diagnostic procedures, products, and technologies | ||

| Involvement in clinical trials | ||

| A centralized office for technology transfer or intellectual property | ||

| The extent to which scientific research, new therapies, and innovation are important parts of the mission and activities of the system and its units | ||

| Professional education | The extent to which professional education and training is a feature of the mission and activities of the organization | Ratio of educational activity to clinical activity or total activity |

| Number of health professional student or trainee positions maintained by the organization | ||

| The extent to which professional education is an important part of the mission and activities of the system and units within the system | ||

| III. Finances | ||

| Payment received for services | The categorical types of payment received, the approach to accountability for services provided, the proportion of each payment type, and the degree of financial risk held | Proportion of payments received for patient care that are fee for service, bundled payments, fully capitated, or partially capitated |

| Provider payment systems | The categorical types of payment to individual providers for their services and the proportion of each payment type | Proportion of provider pay that comes from salary or base pay, productivity or relative value units, quality performance measures, patient satisfaction |

| Ownership | The corporate status and health care industry affiliation of the owner of the health care system | Government, for-profit, or nonprofit entity |

| Health plan, hospital, physician, or group of physicians or clinicians | ||

| Financial solvency | The extent to which the organization’s financial resources exceed the organization’s current liabilities and long-term expenses | Organization’s operating margin as a proportion of expenses and debt |

| Whether the organization operates at a surplus, break even, or a loss | ||

| IV. Patients | ||

| Patient characteristics | Proportion of patients with different characteristics, health conditions, and coverage types | Demographic indicators such as age, gender, race, ethnicity, education, and income |

| Proportion of patients with Medicare, Medicaid, commercial, and no insurance | ||

| Measure of diversity of system and patient population size | ||

| Measures of medical complexity, such as the Charlson Comorbidity Index or the Case Mix Index | ||

| Patient Activation Measure17 | ||

| Geographic characteristics | Geographic location as well as the type of community in which the health care delivery system functions and the size of the catchment area | Urban, suburban, rural, or frontier |

| Geolinked characteristics of the catchment area, such as population density and median household income | ||

| V. Care processes and infrastructure | ||

| Integration | The extent to which a network of organizations or units within 1 organization provides or arranges to provide a coordinated continuum of services to a population and is willing to be held clinically and fiscally accountable for the outcomes and health status of the population served | Functional Integration measure,18 which is a pilot measure of the 3 integration domains: structure, finance, and function |

| Standardization | The extent to which the health care delivery system reduces unnecessary variation while encouraging differences dictated by diversity among patients in their conditions and preferences | A preliminary measure, though difficult to operationalize, of the proportion of the medical care provided by the organization that is covered by protocols and guidelines |

| Performance measurement, public reporting, and quality improvement | The extent to which the organization conducts regular measurement of performance with public reporting, feedback, and a systematic process of improvement | Number of clinical performance measures assessed at least yearly |

| Proportion of those measures with results reported to the public and those providing measured care | ||

| Proportion of those measures with active action plans for improvement | ||

| Health information system | The extent to which clinical and administrative information is organized and available to those who need it in a timely way and the extent to which they have electronic support for those functions | Whether clinical information system is paper only, paper with some electronic ordering or data systems, electronic with separate order and data systems, or electronic that handles all functions |

| Patient care team | Extent to which patient care is delivered by clinicians and staff who regularly work together in an integrated way to serve patients and their families. | AHRQ TeamSTEPPS and Teamwork Attitudes Questionnaire19 |

| Clinical decision support | Extent to which clinical guideline-based reminders and decision aids are incorporated in the process of patient care | E-clinician surveys |

| Average number of reminders or suggestions provided automatically to clinicians during patient visits that are perceived by them as valuable | ||

| Ability of electronic medical record system to link from within the system to established clinical guidelines | ||

| Care coordination | The deliberate organization of patient care activities between ≥ 2 participants involved in a patient’s care to facilitate and maximize the appropriate delivery of health care services to achieve optimal patient experience and outcomes | Approximate number of personnel and clinicians whose job is primarily to coordinate services from different providers for patients |

| AHRQ’s Care Coordination Measures Atlas20 that includes measures of the patient and family perspective, health care professional perspective, and systems representatives perspective | ||

| National Quality Forum’s 24 preferred practices for care coordination20 | ||

| VI. Culture | ||

| Patient centeredness | The degree to which health care delivery is designed to serve the interests of patients (vs providers) | Coordination of care measures |

| Versions of the CAHPS patient experience surveys, especially PCMH | ||

| Shared decision-making | ||

| Various provider continuity measures | ||

| Cultural competence | Ability of systems to provide care to patients with diverse values, beliefs, and behaviors, including tailoring delivery to meet patients’ social, cultural, and linguistic needs | Availability of informational materials and translators |

| Whether cultural competence goals are identified in strategic plan | ||

| Whether there are strategies to recruit, retain, and promote a diverse leadership and staff | ||

| National Quality Forum’s 45 preferred practices for measuring and reporting cultural competency | ||

| Competition–collaboration continuum | Where the organization falls on a scale from competitive to collaborative in relation to other organizations in its locale | Number and scope of collaborative initiatives with competitors |

| Community benefit | Extent to which the organization is concerned about the health of the local community and takes advantage of community services for its patients through collaboration | Level of uncompensated care provided |

| Number and value of formal community partnerships | ||

| Existing mechanism to assess and prioritize local health care needs | ||

| Collaborations with local organizations and public health to improve community health | ||

| Financial contributions to local community organizations | ||

| Innovation diffusion | The degree to which the health care delivery organization or system is focused on creating and adopting new ways to provide care and accomplish its mission | Implementation of regular process improvement via quality improvement mechanisms such as plan–do–study–act |

| Working climate | The degree to which the organization’s employees perceive an environment of openness and fair process | Employee satisfaction survey |

| Proportion of employees who report feeling | ||

| informed about where their company is going | ||

| espected for their contributions at work | ||

| involved in making changes to improve care, service, and efficiency |

Note. AHRQ = Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; CAHPS = Consumer Assessment of Health Providers and Performance Systems; PCMH = Patient Centered Medical Home. A health care delivery system is an organization of people, institutions, and resources to deliver health care services to meet the health needs of a target population.

The selected domains were chosen in an effort to cluster those elements that describe similar aspects of the delivery system. By its nature, an element may not fit perfectly within a domain or, conversely, may be related to aspects of multiple domains. Rather than repeat elements in multiple domains, committee members placed each element in the single domain that the majority felt best represented that element. Many of the elements are simply descriptive rather than normative, such as organizational size, configuration, or type of payments received. In other words, no or little inherent value is generally ascribed to having a large versus small staff, employment versus partnership model, or receiving payment on a fee-for-service versus capitation basis, for example. The descriptive nature of these elements is expected to result in relative ease of measurement and protection from manipulation.

However, some elements are inherently normative or value based, such as care coordination, patient centeredness, and cultural competence. In other words, it is inherently desirable for a health care delivery system to effectively coordinate care, be patient centered, and be sensitive to patients’ cultural background. These elements also tend to describe less tangible characteristics of the organization and are thus less easily measured and potentially more subjective and vulnerable to bias. Furthermore, they tend to describe characteristics that are more structural, cultural, or longitudinal. Nevertheless, the DSC decided to include these elements despite their acknowledged limitations because they represent important aspects of care delivery, with the expectation that objective measures may already be accessible or will evolve over time. One such example is organizational culture—a domain that is easier to describe than to measure. Yet, various instruments are already available, albeit with some limitations, as reviewed by Scott et al.22 and Zazzali et al.,23 who surveyed physician culture and found great variability within groups. Another less tangible element, but equally as essential, is care coordination. The Care Coordination Measures Atlas24 published by AHRQ introduces a framework for structure and processes that influence care coordination and can be used today.

Although many of the value-based measures are directional (i.e., “more is better”), improving 1 desirable attribute may come at the expense of another desirable attribute, such as financial solvency versus comprehensiveness of services and community benefit or standardization versus patient centeredness and research and innovation. The framework as a whole is meant to be used in such a way as to balance such competing values. Elements were chosen as aspects of health care delivery systems that, in the stakeholders’ opinion, were likely to contribute to a delivery organization’s ability to fulfill its mission. The DSC acknowledged that the elements do not necessarily capture every important aspect of a care delivery system but include enough to serve as a basis for a framework describing health care organizations. Conversely, not all elements are necessarily needed to describe a given organization. In addition, the DSC intentionally focused on elements and domains rather than specific measures or measurement systems; measures included in Table 1 serve only as examples.

DISCUSSION

In this article, we present a draft framework created for describing important differences in health care delivery organizations of all sizes and types, one that might facilitate understanding as we study and move from traditional models of care to a system-oriented approach while maintaining a patient-centered focus. In the process, the DSC considered the current status of the health care sector, medical practices in the United States, and current innovative models of care and the overall importance of patient centeredness, which traverses all of the domains.

Current Health Care Sector

The number of single-physician practices dropped from 69% in 2003 and 11% with 2 physicians to 33% in solo or 2-physician practices in 2008.25 In 2008, 92% were single specialty and 8% multispecialty; 15% were in practices of 3 to 5 physicians, and 19% were in groups of 6 to 50 physicians. Thirteen percent practiced in hospital settings, with 44% of hospital-based physicians working in office practices or clinics and the remainder split evenly between emergency rooms and hospital staff.26 Of the physicians, 3% worked in community health centers and 4% in group- or staff-model health maintenance organizations. From the aspect of specialties, 79% were in single-specialty practices, and only 21% were in multispecialty groups.27 Therefore, creating this framework only for large health care organizations would be myopic. The DSC’s intention has been to provide domains and elements that could also be applied to organizations of all sizes, from very large to very small, from single providers to groups of providers. Furthermore, this work was intended to bring an organized set of domains and elements that have been created by all stakeholders (i.e., providers, administrators, policymakers, and health care consumers) under the auspices of AHRQ. The inclusion of this diverse group of stakeholders is in accordance with the Institute of Medicine report, which emphasizes their inclusion in CER to ensure its relevance to health care delivery.6 Health care delivery systems also include those responsible for the public health.

The Commonwealth Fund Commission report15 has described the characteristics of high-performing systems, which include access to information, active management, interdependent accountability, patient access to care, and continuous innovation. The reader may find several of these attributes among the domains and elements we present that can serve researchers as a roadmap to add definitions and borders to their work. Consequently, the current fragmentation of care further highlights the need for the draft framework presented here. One of the key and controversial features of care delivery organizations, primarily large ones, is the extent to which the care they provide is integrated.28–30 This observation is especially true because many studies of care delivery redesign and quality have been conducted in large integrated organizations such as the Veteran’s Health Administration, Group Health, Kaiser Permanente, and Health Partners, among others. There are many definitions of integration, but we have chosen the one developed by Shortell et al.31 and Gillies et al.32 (see Table 1, Domain V). Using this definition, Solberg et al.18,33 demonstrated that, among 100 large medical groups nationally, there was a positive correlation between functional integration and the presence of practice systems that have been associated with higher quality of care and, yet, a lot of diversity existed in integration among these apparently similar organizations. Solberg et al.18 created a set of measures of functional, structural, and financial aspects of integration from the organizational point of view, whereas Singer et al.34 instead built measures from the patient’s perspective. In spite of these measures, no consensus has been reached on how best to measure integration.

Less controversial than integration is the importance of team care as an essential component of better quality, although whether it also decreases costs is less clear. For example, the collaborative care model for major depression has clearly been demonstrated to produce higher quality, although it takes 3 to 4 years to have any impact on costs.35–38 This model is based not only on having a care manager in the primary care practice but also on regular consultation visits by a psychiatrist. The development of effective team care for quality improvement in chronic illness has been explored by Shortell et al.39 and suggests the importance of patient satisfaction. Similarly, the chronic care model by Wagner et al.40 presents the importance of patient engagement as part of the team for chronic care, such as in diabetes. Team care is also a key feature of many of the elements of the medical home. Hence, it seems an important component of this framework (see Table 1, Domain V).41–43

Innovative Care Models

In light of the creation of innovative care systems, the DSC believed that it was important to make this framework capable of describing the key features of organizations of all sizes so that organizational structure and function can more consistently be incorporated into research design, publication, and policy decisions. In addition, the DSC’s intent has been to help compare health care organizations across different settings and provide a framework that will facilitate CER of care delivery functions and outcomes. There is no better example of distinct and different settings than the current care delivery reform emphasis on the medical home and accountable care organizations, encompassing both large and small care organizations.42 Much of the research on these and other care redesign topics is being conducted among clinics of varying size and ownership, often members of practice-based research networks.44 The Kaiser Permanente system, as compared with independent traditional practices, offers a model of a physician organization that has adopted value- and quality-oriented, system-level care tools to deliver more effective care.45 To understand whether the results apply to any particular practice, it is essential to understand whether the clinics involved are similar or, if they are not, to decide whether the differences affect generalizability.

Role of Public Health in Comparative Effectiveness Research

Health issues that have the greatest impact at the population health level and how to compare them should also be part of CER. Teutsch and Fielding46 argued that comparative effective assessments of public health interventions can positively influence health at all levels—that is, the individual and the population as a whole—and that studies should also focus on the development of research methodology applied to public health. However, most of the current published CER work has centered on the comparison of 2 or more interventions focused on or targeted to disease management or therapies. Other studies, however, must explore the relevance of this work to public health efforts so that interventions can and should be studied not only within systems of care but at the population level. Certainly, the application of CER methodology to public health will present challenges because, for example, randomization as in controlled clinical trials may not always be possible. However, these challenges may lead to more innovative statistical techniques, such as propensity matching.

The taxonomy presented here could be adapted to public health approaches—some of which are easier to identify than others. For example, the patient domain may be translated to the community of patients or population at large with a certain disease entity. The organizational structure domain, as another example, could apply to public health services available or desirable to improve a specific aspect of populations.

Dubois and Graff47 recognized these difficulties and the magnitude and variety of tasks that are presented when considering CER at the public health level. They offered a framework, complementary to the taxonomy presented here, for prioritization of CER efforts with a series of elements. Among these elements are the involvement of multiple stakeholders and the dissemination of the process. In parallel with their framework, the domains of DSC’s framework were constructed by multiple stakeholders who included representatives of patient groups. Correspondingly, this article, and a detailed report to AHRQ, represent its dissemination. Future involvement by public health researchers, particularly in these early stages of CER development and application, will enrich this work by adapting and adding methodology to the domains presented here.

As such, this work has focused on CER priorities in the United States, which, according to the Congressional bill that introduced CER, states that findings should not be “construed as mandates, guidelines, or recommendations for payment, coverage, or treatment . . . for any public or private payer.”48 By contrast, the Commonwealth Fund has reviewed the use of CER in 4 countries—Australia, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom—in which the research is driven by demand for information by those making health care policy and practice decisions.49 Thus, involvement by multiple stakeholders, including policymakers, should occur earlier, rather than later, after a CER plan is developed. Whether driven by the public need for policy and allocation of resources or by the need to improve quality of care for patients directly, the framework presented here is broad enough to be applicable to either process.

Patient Centeredness

In 2001, the Institute of Medicine4 observed that health care has traditionally been provider and payment centered and that a shift in paradigm was critical to the survival of the US health care system. That change was a shift in paradigm to one that was patient centered. Accordingly, the DSC considered patient centeredness to be a critical component of current care that should thus be given special attention. Patient centeredness, when describing health systems, reflects an undergirding and dominant value of attending to patient needs and preferences in planning and delivering care.50 The emphasis on quality of care has resulted in a strong focus on patient centeredness and is driving the efforts at defining the construct and measuring its antecedents and outcomes.46 Furthermore, the awareness of health disparities based on race/ethnicity, gender, age, and other factors has increased, centering on the individual patient and family members, their satisfaction, and health care processes and outcomes. AHRQ, in addition to many quality-oriented organizations and regulatory agencies, has supported and disseminated patient-centeredness research findings and tools based on the research. So far, consensus is lacking for standard measurement models or operational definitions, but considerable research and dissemination are evident in the quality literature.51 Saha et al. present the 7 primary dimensions of patient-centered care as originally defined by the Picker Commonwealth program: respect for patients’ values; preferences and expressed needs; coordination and integration of care; information, communication, and education; physical comfort; emotional support and alleviation of fear and anxiety; involvement of family and friends; and transition and continuity.50 Currently, the tools most frequently used to measure patient centeredness are patient satisfaction surveys, such as the Press-Ganey Medical Practice Survey and the Consumer Assessment of Health Providers and Performance Systems for hospitals, and adaptations for other health care settings such as long-term care facilities (https://www.cahps.ahrq.gov).52 The work of identifying patient centeredness or need thereof by patient advisory teams and peer patient coaches has led to reform in several innovative systems and in health policy.53 Hence, patient centeredness, as a value, can be assessed in each of the elements spelled out in this article and should remain in the background of any work using this framework.

Limitations

The DSC understands that there are limitations to this framework and other aspects that are outside the scope of this article. For example, we have not discussed organizational boundaries, which are defined as the characteristics of participation in an organization that determine whether a person is within the organization and subject to the influence of its rules, processes, and culture. Yet, boundaries may be important to organizations reaching their mission. The committee also understands that some domains, for example, culture, have elements that are not easily or objectively measurable and serve as an illustration of the difficulty inherent in creating a classification of human designs for organizations to implement evidence-based decisions about their management. Indeed, the human element raises uncertainty, as defined by the larger SG.

Summary

This framework presentation recognizes the continuous evolution of health care systems, particularly in light of the need for CER. To compare health care organizations in 1 or many aspects, there is a need for a foundation of commonality in language for areas that are well defined and further work for those that are not. The framework can be used to characterize potentially important differences in structure and function of health care delivery organizations and systems. To that end, researchers could use the framework to clearly describe the delivery setting for a study, facilitating understanding of whether the results are applicable in specific settings and situations.

The DSC members understand that this work is preliminary but believe that it is a step in the right direction because there is currently considerable organizational diversity and complexity in health care. Future reports may continue to develop and elaborate on the domains captured here, whether 1 at a time or in groups. This framework of 26 elements in 6 domains may allow for more understandable studies and descriptions of delivery system changes to improve the health of people in the United States. We have reflected on the domains and elements presented here and fully recognize the need for further work in many areas. However, there are others in which definitions were readily available and agreed upon. It is in these areas of agreement that work can be initiated today.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Christine Chang, MD, MPH, of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), and Jill Yegian, PhD, and Diane Martinez, MPH, of the American Institute for Research for their guidance and support during meetings, conference calls, and e-mails. We also appreciate AHRQ’s role in convening the Stakeholders Group and the Delivery Systems Committee. We also thank Ms. Patricia Peralta for her review and editing.

References

- 1.Conway PH, Clancy C. Transformation of health care at the front line. JAMA. 2009;301(7):763–765. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Averill RF, Goldfield NI, Vertrees JC, McCullough EC, Fuller RL, Eisenhandler J. Achieving cost control, care coordination, and quality improvement through incremental payment system reform. J Ambul Care Manage. 2010;33(1):2–23. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e3181c9f437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grundy P, Hagan KR, Hansen JC, Grumbach K. The multi-stakeholder movement for primary care renewal and reform. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(5):791–798. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nolan T Institute for Healthcare Improvement Board of Directors. US Health Care Reform by Region. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sox HC, Greenfield S. Comparative effectiveness research: a report from the Institute of Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(3):203–205. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-3-200908040-00125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olsen L, Grossman C, McGinnis JM. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. Learning What Works: Infrastructure Required for Comparative Effectiveness Research: Workshop Summary. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bazzoli GJ, Shortell SM, Dubbs N, Chan C, Kralovec P. A taxonomy of health networks and systems: bringing order out of chaos. Health Serv Res. 1999;33(6):1683–1717. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dubbs NL, Bazzoli GJ, Shortell SM, Kralovec PD. Reexamining organizational configurations: an update, validation, and expansion of the taxonomy of health networks and systems. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(1):207–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00222.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bazzoli GJ, Shortell SM, Dubbs NL. Rejoinder to taxonomy of health networks and systems: a reassessment. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(3 pt 1):629–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00525.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luke RD. Taxonomy of health networks and systems: a reassessment. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(3 pt 1):618–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00524.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donabedian A. Quality assurance: corporate responsibility for multihospital systems. QRB Qual Rev Bull. 1986;12(1):3–7. doi: 10.1016/s0097-5990(16)30004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donabedian D. What students should know about the health and welfare systems. Nurs Outlook. 1980;28(2):122–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mays GP, Scutchfield FD, Bhandari MW, Smith SA. Understanding the organization of public health delivery systems: an empirical typology. Milbank Q. 2010;88(1):81–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00590.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shih A, Davis K, Schoenbaum S . Organizing the US Health Care Delivery System for High Performance. New York, NY: Commonwealth Fund; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2000—Health Systems: Improving Performance. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(4 pt 1):1005–1026. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Solberg LI, Asche SE, Shortell SM et al. Is integration in large medical groups associated with quality? Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(6):e34–e41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. AHRQ TeamSTEPPS and Teamwork Attitudes Questionnaire. AHRQ, editor. 2014. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/teamstepps/instructor/index.html. Accessed April 22, 2014.

- 20.National Quality Forum. Preferred Practices and Performance Measures for Measuring and Reporting Care Coordination: A Consensus Report. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morgan G. Images of Organization. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott T, Mannion R, Davies H, Marshall M. The quantitative measurement of organizational culture in health care: a review of the available instruments. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(3):923–945. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zazzali JL, Alexander JA, Shortell SM, Burns LR. Organizational culture and physician satisfaction with dimensions of group practice. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(3 pt 1):1150–1176. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00648.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDonald KM, Schultz E, Albin L . Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010. Care Coordination Atlas Version 3 (Prepared by Stanford University under subcontract to Battelle on Contract No. 290-04-0020). AHRQ Publication No.11-0023-EF. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boukus E, Cassil A, O'Malley AS. A snapshot of U.S. physicians: key findings from the 2008 Health Tracking Physician Survey. Data Bull (Cent Stud Health Syst Change ) 2009:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hing E, Burt CW. Office-based medical practices: methods and estimates from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Adv Data. 2007;383:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kane CK. The Practice Arrangements of Patient Care Physicians 2007-2008. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Budetti PP, Shortell SM, Waters TM et al. Physician and health system integration. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21(1):203–210. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.1.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shields MC, Sacks LB, Patel PH. Clinical integration provides the key to quality improvement: structure for change. Am J Med Qual. 2008;23(3):161–164. doi: 10.1177/1062860608315797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Enthoven AC, Tollen LA. Competition in health care: it takes systems to pursue quality and efficiency. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;(suppl web exclusives) doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w5.420. W5-420–W5-4233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shortell SM, Bazzoli GJ, Dubbs NL, Kralovec P. Classifying health networks and systems: managerial and policy implications. Health Care Manage Rev. 2000;25(4):9–17. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200010000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gillies RR, Shortell SM, Anderson DA, Mitchell JB, Morgan KL. Conceptualizing and measuring integration: findings from the health systems integration study. Hosp Health Serv Adm. 1993;38(4):467–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Solberg LI, Asche SE, Pawlson LG, Scholle SH, Shih SC. Practice systems are associated with high-quality care for diabetes. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(2):85–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singer SJ, Burgers J, Friedberg M, Rosenthal MB, Leape L, Schneider E. Defining and measuring integrated patient care: promoting the next frontier in health care delivery. Med Care Res Rev. 2011;68(1):112–127. doi: 10.1177/1077558710371485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Unutzer J, Katon WJ, Fan MY et al. Long-term cost effects of collaborative care for late-life depression. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(2):95–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(21):2314–2321. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.21.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams JW, Jr, Gerrity M, Holsinger T, Dobscha S, Gaynes B, Dietrich A. Systematic review of multifaceted interventions to improve depression care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29(2):91–116. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shortell SM, Marsteller JA, Lin M et al. The role of perceived team effectiveness in improving chronic illness care. Med Care. 2004;42(11):1040–1048. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200411000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20(6):64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002;288(14):1775–1779. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosser WW, Colwill JM, Kasperski J, Wilson L. Progress of Ontario’s Family Health Team model: a patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(2):165–171. doi: 10.1370/afm.1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schoen C, Osborn R, Squires D, Doty M, Pierson R, Applebaum S. New 2011 survey of patients with complex care needs in eleven countries finds that care is often poorly coordinated. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(12):2437–2448. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tierney WM, Oppenheimer CC, Hudson BL et al. A national survey of primary care practice-based research networks. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(3):242–250. doi: 10.1370/afm.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rittenhouse DR, Grumbach K, O’Neil EH, Dower C, Bindman A. Physician organization and care management in California: from cottage to Kaiser. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23(6):51–62. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.6.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Teutsch SM, Fielding JE. Applying comparative effectiveness research to public and population health initiatives. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(2):349–355. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dubois RW, Graff JS. Setting priorities for comparative effectiveness research: from assessing public health benefits to being open with the public. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(12):2235–2242. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. United States Code, 2009 Edition Title 42. The Public Health and Welfare Chapter 6A. Public Health Service Subchapter VII. 2009. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Part B–Health Care Improvement Research Sec. 299b-8. Federal Coordinating Council for Comparative Effectiveness Research From the US Government Printing Office.

- 49.Chalkidou K, Walley T. Using comparative effectiveness research to inform policy and practice in the UK HHS: past, present and future. Pharmacoeconomics. 2010;28(10):799–811. doi: 10.2165/11535260-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saha S, Beach MC, Cooper LA. Patient centeredness, cultural competence and healthcare quality. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(11):1275–1285. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31505-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aragon SJ, McGuinn L, Bavin SA, Gesell SB. Does pediatric patient-centeredness affect family trust? J Healthc Qual. 2010;32(3):23–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2010.00092.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. AHRQ. Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems. 2014. Available at: https://www.cahps.ahrq.gov. Accessed April 22, 2014.

- 53.Sodomka P. Engaging patients and families: a high leverage tool for health care leaders. Hosp Health Netw. 2006:28–29. [Google Scholar]