Background: Dual oxidase (Duox)-Duox activator (DuoxA) complexes produce H2O2, not O2⨪, suggesting that specialized mechanisms convert O2⨪ to H2O2.

Results: In comparison with Duox2, Duox1 prevents O2⨪ leakage more stringently.

Conclusion: Duox A-loops function in reducing O2⨪ release by promoting the stabilization and maturation of Duox-DuoxA complexes.

Significance: The mechanism underlying H2O2 production by Duoxes has been clarified.

Keywords: Glycosylation, Hydrogen Peroxide, NADPH Oxidase, Superoxide Ion, Thyroid Hormone

Abstract

NADPH oxidase (Nox) family proteins produce superoxide (O2⨪) directly by transferring an electron to molecular oxygen. Dual oxidases (Duoxes) also produce an O2⨪ intermediate, although the final species secreted by mature Duoxes is H2O2, suggesting that intramolecular O2⨪ dismutation or other mechanisms contribute to H2O2 release. We explored the structural determinants affecting reactive oxygen species formation by Duox enzymes. Duox2 showed O2⨪ leakage when mismatched with Duox activator 1 (DuoxA1). Duox2 released O2⨪ even in correctly matched combinations, including Duox2 + DuoxA2 and Duox2 + N-terminally tagged DuoxA2 regardless of the type or number of tags. Conversely, Duox1 did not release O2⨪ in any combination. Chimeric Duox2 possessing the A-loop of Duox1 showed no O2⨪ leakage; chimeric Duox1 possessing the A-loop of Duox2 released O2⨪. Moreover, Duox2 proteins possessing the A-loops of Nox1 or Nox5 co-expressed with DuoxA2 showed enhanced O2⨪ release, and Duox1 proteins possessing the A-loops of Nox1 or Nox5 co-expressed with DuoxA1 acquired O2⨪ leakage. Although we identified Duox1 A-loop residues (His1071, His1072, and Gly1074) important for reducing O2⨪ release, mutations of these residues to those of Duox2 failed to convert Duox1 to an O2⨪-releasing enzyme. Using immunoprecipitation and endoglycosidase H sensitivity assays, we found that the A-loop of Duoxes binds to DuoxA N termini, creating more stable, mature Duox-DuoxA complexes. In conclusion, the A-loops of both Duoxes support H2O2 production through interaction with corresponding activators, but complex formation between the Duox1 A-loop and DuoxA1 results in tighter control of H2O2 release by the enzyme complex.

Introduction

Dual oxidases (Duoxes3; Duox1 and Duox2) are members of the NADPH oxidase (Nox) family proteins (Nox1–5 and Duoxes) that produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) (1–3). Duox1 (4) and Duox2 (5) are functional only in combination with maturation factors known as Duox activators (DuoxAs; DuoxA1 and DuoxA2) (6). Although DuoxAs were first described as factors required to permit Duoxes to exit the endoplasmic reticulum, it was later reported that Duox and DuoxA proteins form stable heterodimers and co-translocate to the plasma membrane (7). Both Duoxes were first characterized as thyroid oxidases supporting thyroid hormone biosynthesis, although Duox2 is the dominant form, with an expression level five times higher than that of Duox1 in thyroid tissue (8). Moreover, mutations or deficiencies in Duox2 or DuoxA2 have been reported to cause congenital hypothyroidism in mice (9, 10) and humans (8), whereas deficiency in Duox1 has no effect on thyroid hormone levels in Duox1 knock-out mice (11). Bi-allelic mutations in Duox2 reportedly cause transient congenital hypothyroidism, suggesting that some compensation occurs by Duox1 (12). More recently, a patient with transient congenital hypothyroidism was described; this patient was compound heterozygous for a large deletion comprising DUOX2, DUOXA2, and DUOXA1 and a nonfunctional missense mutation of DUOXA2 in the other allele, suggesting compensation by the remaining Duox1-DuoxA1 complex or by the mismatched Duox2-DuoxA1 complex (13).

In addition, Duox enzymes have been detected and believed to function on the epithelial cell surfaces of mucosal and exocrine tissues (2, 14–16), including the airways and gastrointestinal tract. In these tissues, Duoxes also function in host defense against a broad spectrum of pathogens (17–19). Nox family proteins produce the primary product superoxide (O2⨪) by directly transferring an electron to molecular oxygen (2, 20). Duoxes produce O2⨪ as an intermediate product (21), but the final product generated by mature Duoxes is H2O2, suggesting that intramolecular O2⨪ dismutation or other mechanisms contribute to H2O2 release (2). In tissues with high Duox expression, the enzymes accumulate on the apical plasma membrane, facilitating H2O2 release from epithelial cell surfaces to support the activities of extracellular hemoperoxidases (22).

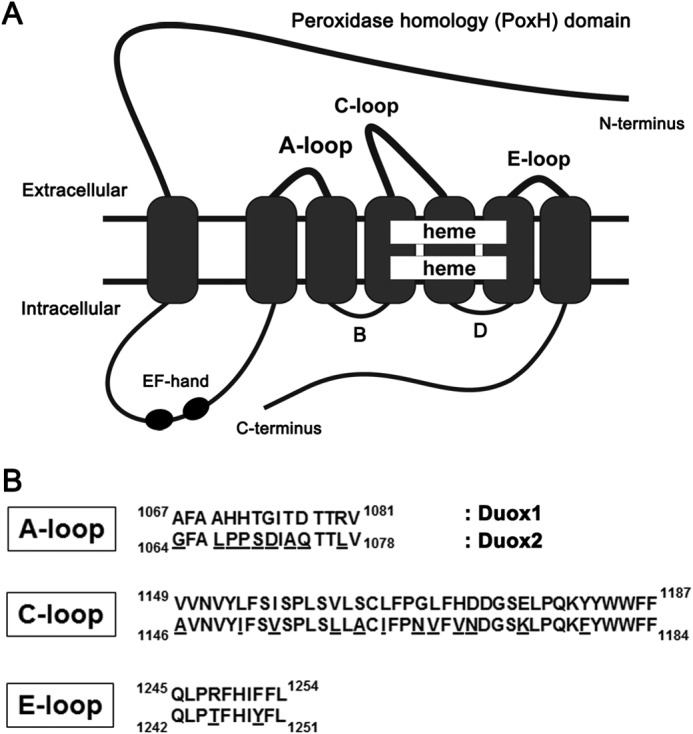

In contrast to Nox1–5, Duoxes have an extended N-terminal extracellular domain called the peroxidase homology (PoxH) domain, followed by an additional transmembrane (TM) segment and an intracellular loop containing two calcium-binding EF-hand motifs (4, 23) (Fig. 1A). Thus, Duoxes possess four extracellular regions: the PoxH domain (1–595 amino acids (aa) in human Duox2) and three loops (the A-loop, 1064–1078 aa; C-loop, 1146–1184 aa; E-loop, 1242–1251 aa in human Duox2) (Fig. 1A). The PoxH domain is a candidate for intramolecular O2⨪ dismutation, although the isolated PoxH domains of both Duoxes demonstrate no O2⨪ dismutation activity in vitro (24, 25). Thus, the mechanism underlying H2O2 production by Duoxes remains poorly understood.

FIGURE 1.

Sequence alignment of the three extracellular loops of Duox1 and Duox2. Schematic illustration of a Duox (A) and amino acid sequence alignment of the three extracellular loops (A, C, and E) of Duox1 and Duox2 (B) (4, 23). Superscript and subscript numbers represent amino acid sequence numbers. Underlined residues denote differences between Duox1 and Duox2.

A switch in ROS generation from H2O2 to O2⨪ occurs when Duox2 is mismatched with DuoxA1 (26). We reported that the mismatched combination of Duox2 + DuoxA1, but not that of Duox1 + DuoxA2, releases O2⨪ in addition to H2O2; we called this phenomenon O2⨪ leakage (7). In this study we examined why Duox2, but not Duox1, leaks O2⨪, in addition to exploring the structural features of Duox and DuoxA proteins involved in H2O2 release. We found that the A-loops of Duoxes, particularly Duox1, function in controlling O2⨪ release by contributing to the stabilization and maturation of Duox-DuoxA complexes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

A polyclonal antibody (pAb) against Duoxes, which preferentially detects Duox2 via the first intracellular loop (639–1039 aa of human Duox2) but also detects Duox1, was previously described (15). A pAb against DuoxA1, which recognizes the extracellular N terminus of DuoxA1, was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Unfortunately, no commercial Ab against DuoxA2 for immunoblotting or immunostaining is available. mAbs against HA(TANA2)-conjugated HRP, Alexa Fluor 488, and magnetic agarose were obtained from MBL International Corp. An mAb against FLAG(M2)-conjugated HRP was obtained from Sigma. Endoglycosidase H (Endo H) was obtained from New England Biolabs.

Cell Culture

HEK293 cells (ATCC) were maintained in Eagle's minimal essential medium (Wako Pure Chemical Industries) containing 10% FBS (Nichirei Biosciences), 100 μm nonessential aa (Wako Pure Chemical Industries), and antibiotics at 37 °C in 5% CO2.

Construction of Plasmids

We used human Duox2, DuoxA1(α),and DuoxA2 in pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen), which were previously described (7). Human Duox1 cDNA was a kind gift from Dr. Francoise Miot (Université Libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium) (4) and was transferred into pcDNA3.1. Duox1 and Duox2 with a 2×HA tag between Asn-23 and Pro-24 and between Asp-27 and Ala-28, respectively, in the first extracellular region were created in pcDNA3.1 by site-directed mutagenesis using a QuikChange Lightening Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies). The chimeric construct Duox(1PoxH-2), possessing the PoxH domain of Duox1 (1–592 aa) and the Nox-like portion of Duox2 (596–1548 aa), and the chimeric construct Duox(2PoxH-1), possessing the PoxH domain of Duox2 (1–594 aa) and the Nox-like portion of Duox1 (592–1551 aa), were created in pcDNA3.1 by PCR and restriction enzyme-based recombination. DuoxA1 and DuoxA2 in both p3×FLAG-CMV-10 (Sigma) and p3×FLAG-CMV-14 (Sigma-Aldrich) vectors were made using PCR and named 3N×FLAG-DuoxA1, 3N×FLAG-DuoxA2, DuoxA1–3C×FLAG, and DuoxA2–3C×FLAG. DuoxA2 with 2×FLAG and DuoxA2 with 1×FLAG at the N terminus were made by QuikChange using 3N×FLAG-DuoxA2 as a template. DuoxA2 with 2×HA at the N terminus was made by QuikChange using DuoxA2 as a template. DuoxA1 with 1×FLAG at the C terminus was made by QuikChange using DuoxA1–3C×FLAG as a template. The chimeric construct DuoxA(1-2), possessing the N-terminal extracellular region of DuoxA1 (1–19 aa) and DuoxA2 (20–320 aa), and the chimeric construct DuoxA(2-1), possessing the N-terminal extracellular region of DuoxA2 (1–19 aa) and DuoxA1 (20–343 aa), were created in pcDNA3.1 using PCR. N-terminal deletion (2–17 aa) mutants of DuoxA1 and DuoxA2 were generated using PCR and named DuoxA1(N-del) and DuoxA2(N-del). All other mutants/chimeric constructs of Duox and DuoxA, including Duox2→1(A:8aa), Duox2→1(C:10aa), Duox2→1(E:TY/RF), Duox1→2(A:8aa+L), Duox1→Nox1(A), Duox1→Nox5(A), Duox2→Nox1(A), Duox2→Nox5(A), DuoxA(1F-2), and DuoxA(2-1S-2), were made by QuikChange. These are named and described in Table 1 and are illustrated in Figs. 3A, 4A, 5A, 7A, 7C, and 8A. All plasmids were sequenced to confirm their identities.

TABLE 1.

Summary of the Duox and DuoxA expression constructs used

PoxH, peroxidase homology; F, first half; S, second half; N, N terminus; C, C terminus; A, A-loop; C, C-loop; E, E-loop; FLAG-tagged constructs are in p3×FLAG-CMV vector and all other constructs in pcDNA3.1.

| Name of protein | Structures of expressed protein |

|---|---|

| Duox | |

| Duox1 and Duox2 | Wild type Duox1 and Duox2 |

| 2×HA-Duox1 | 2 × HA tag between Asn-23 and Pro-24 of extracellular PoxH domain |

| 2×HA-Duox2 | 2 × HA tag between Asp-27 and Ala-28 of extracellular PoxH domain |

| Duox PoxH-domain chimera | |

| Duox(1PoxH-2) | Chimera of PoxH domain of Duox1 (1–592 aa) and Nox-like portion of Duox2 (596–1548 aa) |

| Duox(2PoxH-1) | Chimera of PH domain of Duox2 (1–594 aa) and Nox-like portion of Duox1 (592–1551 aa) |

| DuoxA | |

| DuoxA1 and DuoxA2 | Wild type DuoxA1 and DuoxA2 |

| 3NxFLAG-DuoxA1 | 3xFLAG tag at the extracellular N terminus |

| DuoxA1–3CxFLAG | 3xFLAG tag at the intracellular C terminus |

| DuoxA1–1CxFLAG | 1xFLAG tag at the extracellular C-terminus |

| DuoxA1(N-del) | The extracellular N terminus (2–17 aa) deletion |

| 3NxFLAG-DuoxA2 | 3xFLAG tag at the extracellular N terminus |

| 2NxFLAG-DuoxA2 | 2 × FLAG tag at the extracellular N terminus |

| 1NxFLAG-DuoxA2 | 1xFLAG tag at the extracellular N terminus |

| 2NxHA-DuoxA2 | 2 × HA tag at the extracellular N terminus |

| DuoxA2–3CxFLAG | 3xFLAG tag at the intracellular C terminus |

| DuoxA2(N-del) | The extracellular N terminus (2–17 aa) deletion |

| DuoxA N-terminal chimera | |

| DuoxA(1–2) | Chimera of extracellular N terminus of DuoxA1 (1–19 aa) and DuoxA2 (20–320 aa) |

| DuoxA(2–1) | Chimera of extracellular N terminus of DuoxA2 (1–19 aa) and DuoxA1 (20–343 aa) |

| DuoxA(1F-2) | Chimera of DuoxA1 (1–8 aa; first half of 19aa) and DuoxA2 (9–320 aa) |

| DuoxA(2–1S-2) | Chimera of DuoxA2 (1–11 aa), DuoxA1 (12–19 aa; second half of 19aa), and DuoxA2 (20–320 aa) |

| A-loop | |

| Duox2→1(A:5aa) | 5aa in A-loop of Duox2 is replaced by corresponding 5aa in A-loop of Duox1 |

| Duox2→1(A:8aa) | 8aa in A-loop of Duox2 is replaced by corresponding 8aa in A-loop of Duox1 |

| Duox1→2(A:F4aa) | 4aa (first half of 8aa) in A-loop of Duox1 is replaced by corresponding 4aa in A-loop of Duox2 |

| Duox1→2(A:S4aa) | 4aa (second half of 8aa) in A-loop of Duox1 is replaced by corresponding 4aa in A-loop of Duox2 |

| Duox1→2(A:8aa) | 8aa in A-loop of Duox1 replaced by corresponding 8aa in A-loop of Duox2 |

| Duox1→2(A:8aa+L) | 8aa + Arg in A-loop of Duox1 replaced by corresponding residues (8aa + Leu) in A-loop of Duox2 |

| Duox1→2(A:8aa+GL) | 8aa + Ala and Arg in A-loop of Duox1 replaced by corresponding residues (8aa + Gly and Leu) in A-loop of Duox2 |

| Duox1→2(A:8aa+L)+L/A | Duox1→2 (A:8aa + L) with reversed mutation (Duox2 to Duox1), Leu to Ala |

| Duox1→2(A:8aa+L)+PP/HH | Duox1→2 (A:8aa + L) with reversed mutation (Duox2 to Duox1), Pro-Pro to His-His |

| Duox1→2(A:8aa+L)+PP/HP | Duox1→2 (A:8aa + L) with reversed mutation (Duox2 to Duox1), Pro-Pro to His-Pro |

| Duox1→2(A:8aa+L)+PP/PH | Duox1→2 (A:8aa + L) with reversed mutation (Duox2 to Duox1), Pro-Pro to Pro-His |

| Duox1→2(A:8aa+L)+D/G | Duox1→2 (A:8aa + L) with reversed mutation (Duox2 to Duox1), Asp to Gly |

| Duox1→2(A:8aa+L)+A/T | Duox1→2 (A:8aa + L) with reversed mutation (Duox2 to Duox1), Ala to Thr |

| Duox1→2(A:8aa+L)+Q/D | Duox1→2 (A:8aa + L) with reversed mutation (Duox2 to Duox1), Gln to Asp |

| Duox1→2(A:PPD) | 3aa residues in A-loop of Duox1 are replaced by corresponding Pro,Pro and Asp residues in A-loop of Duox2 |

| Duox-Nox(A-loop) chimera | |

| Duox1→Nox1(A) | 7aa in A-loop of Duox1 replaced by corresponding residues in A-loop of Nox1 |

| Duox1→Nox5(A) | 7aa in A-loop of Duox1 replaced by corresponding residues in A-loop of Nox5 |

| Duox2→Nox1(A) | 7aa in A-loop of Duox2 replaced by corresponding residues in A-loop of Nox1 |

| Duox2→Nox5(A) | 7aa in A-loop of Duox2 replaced by corresponding residues in A-loop of Nox5 |

| C-loop | |

| Duox2→1(C:10aa) | 10aa (IVLAINVVNK) in C-loop of Duox2 replaced by corresponding 10 aa in C-loop of Duox1 (LIVSLGLHDE) |

| E-loop | |

| Duox2→1(E:TY/RF) | Thr and Tyr in E-loop of Duox2 replaced by corresponding Arg and Phe in E-loop of Duox1 |

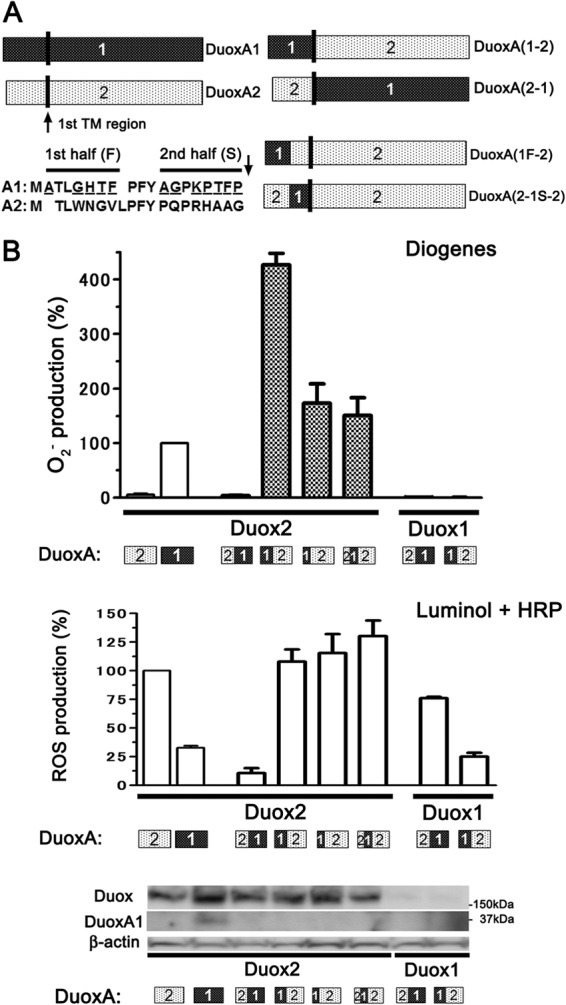

FIGURE 3.

O2⨪ leakage from Duox2 paired with DuoxAs with the N-terminal extracellular region of DuoxA1. A, illustration showing DuoxA1, DuoxA2, and four chimeric DuoxA proteins: DuoxA(1-2), DuoxA(2-1), DuoxA(1F-2), and DuoxA(2-1S-2). B, various Duox and DuoxA pairs were transfected into HEK293 cells. O2⨪, and reactive oxygen species were measured by chemiluminescence assay using Diogenes and luminol + HRP, respectively. Duox2 + DuoxAs with the N-terminal extracellular region of DuoxA1 show O2⨪ production in the following order: DuoxA(1-2) > DuoxA(1F-2) = DuoxA(2-1S-2). Immunoblotting detected the expression of Duoxes and DuoxAs. A pAb against Duoxes preferentially reacts with Duox2 via its first intracellular loop but also faintly detects Duox1 (the last two lanes). A pAb for DuoxA1, which reacts with its extracellular N terminus, only detects wild-type DuoxA1.

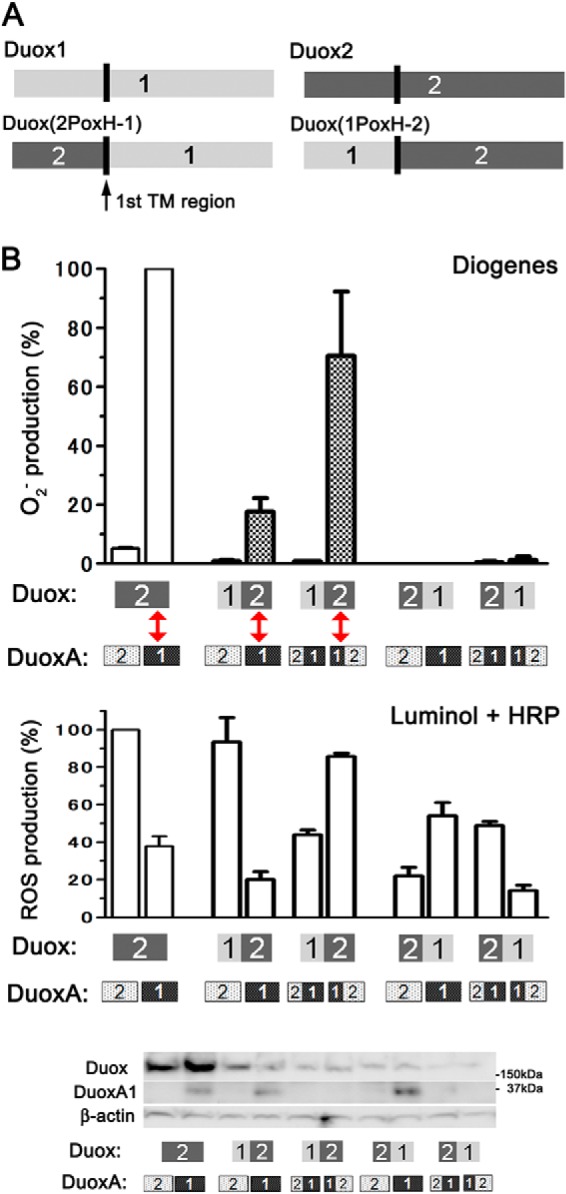

FIGURE 4.

O2⨪ leakage from pairs of Duoxes with the Nox-like portion of Duox2 and DuoxAs with the N-terminal extracellular region of DuoxA1. A, illustration showing Duox1, Duox2, and two chimeric Duox proteins: Duox(1PoxH-2) and Duox(2PoxH-1). B, various Duox and DuoxA pairs were transfected into HEK293 cells. O2⨪ and total reactive oxygen species were measured by chemiluminescence assay using Diogenes and luminol + HRP, respectively. Pairs (red arrows) with the Duox2 portion after the first transmembrane segment (termed the Nox-like portion) + DuoxA with the N-terminal extracellular region of DuoxA1 show O2⨪ production. Immunoblotting detects the expression levels of various Duox and DuoxA pairs. A pAb against Duoxes faintly detected Duox2 chimeras in the two right-hand lanes. A pAb for DuoxA1 detects only wild-type DuoxA1.

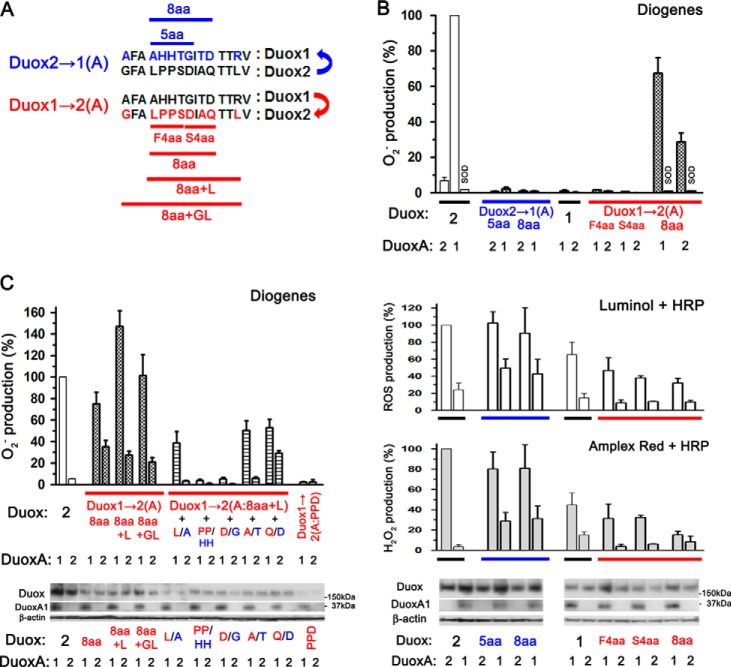

FIGURE 5.

The A-loop of Duox is associated with O2⨪ leakage. A, alignment of the A-loops of Duox1 and Duox2. The upper (blue) and lower (red) illustrations indicate the changes in aa sequence (number and residue) of the A-loop from Duox2 to Duox1 (Duox2→1(A)) and those from Duox1 to Duox2 (Duox1→2(A)), respectively. B, various pairs, including Duox2→1(A:5aa) or Duox2→1(A:8aa) + DuoxA, Duox1→2(A:F4aa), Duox1→2(A:S4aa), or Duox1→2(A:8aa) + DuoxA, were transfected into HEK293 cells. O2⨪, reactive oxygen species, and H2O2 were measured by chemiluminescence assay using Diogenes, luminol + HRP, and Amplex Red + HRP, respectively. Neither Duox2→1(A:5aa) nor Duox2→1(A:8aa) shows significant O2⨪ production. In contrast, Duox1→2(A:8aa), but not Duox1→2(A:F4aa) or Duox1→2(A:S4aa), gained the ability to produce O2⨪, which is abolished by the addition of superoxide dismutase. Immunoblotting detects comparable expression levels of various Duox and DuoxA pairs. C, various pairs of Duox1→2(A) + DuoxA were transfected into HEK293 cells. O2⨪ was measured by chemiluminescence assay using Diogenes. Duox1→(A:8aa+L) + DuoxA1 shows the highest O2⨪ production. PP/HH or D/G mutations abolish O2⨪ production by Duox1→2(A:8aa+L). Duox1→2(A:PPD) + DuoxA shows no ability to produce O2⨪. Immunoblotting detects expression levels of various Duox and DuoxA pairs.

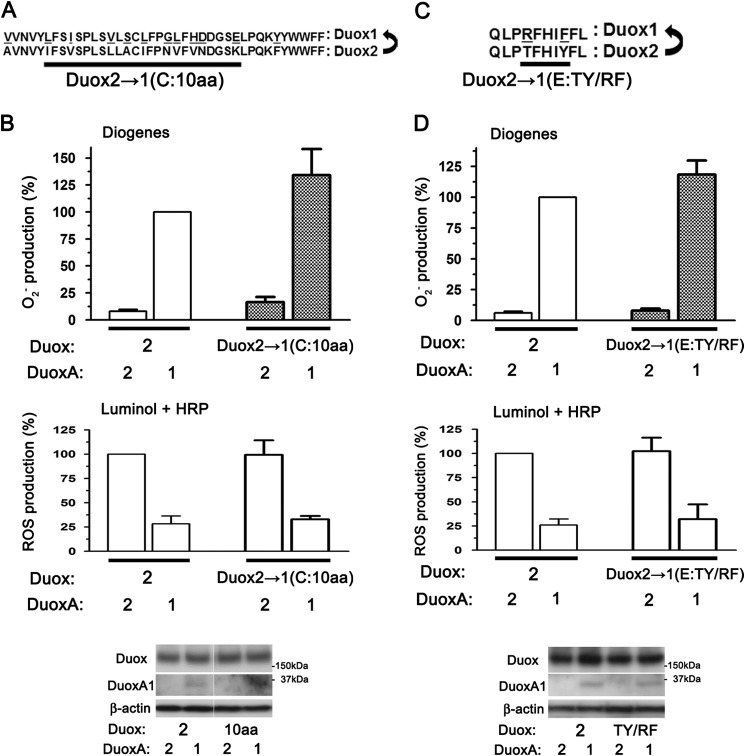

FIGURE 7.

The C- and E-loop of Duox are not associated with O2⨪ leakage. A, alignment of the C-loops of Duox1 and Duox2 and illustrations of chimeric Duox2 mutants indicating the residue and number of amino acids changes in the C-loop from Duox2 to Duox1 (Duox2→1(C)). B, Duox2→1(C:10aa) and DuoxA pairs were transfected into HEK293 cells. O2⨪ and ROS were measured by chemiluminescence assays using Diogenes and luminol + HRP, respectively. The Duox2→1(C:10aa) + DuoxA pairs show no decreased O2⨪ production. Immunoblotting (from the same membrane and image) detects comparable expression levels of various Duox and DuoxA pairs. C, alignment of the E-loops of Duox1 and Duox2 and illustrations of chimeric Duox2 mutants indicating the residues change in the E-loops from Duox2 to Duox1 (Duox2→1(E)). D, Duox2→1(E:TY/RF) and DuoxAs pairs were transfected into HEK293 cells. O2⨪ and ROS were measured by chemiluminescence assay using Diogenes and luminol + HRP, respectively. The Duox2→1(E:TY/RF) + DuoxA pairs show no decreased O2⨪ production. Immunoblotting detects comparable expression levels of various Duox and DuoxA pairs.

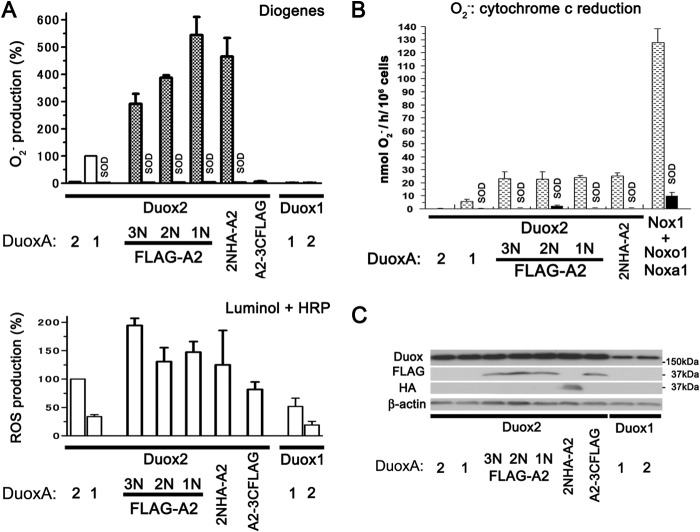

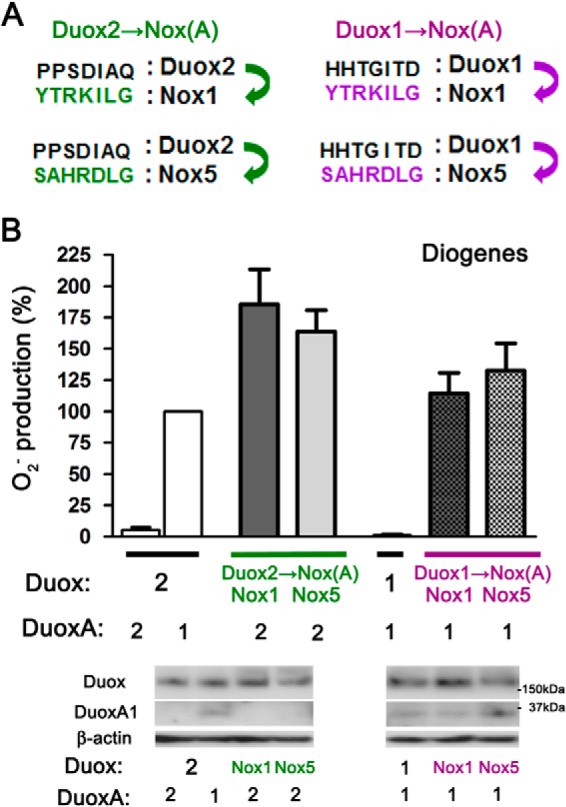

FIGURE 8.

The A-loops of both Duox1 and Duox2 prevent O2⨪ leakage. The illustrations indicate changes in the core aa sequences of the A-loops (7 aa) from Duoxes to Nox (1 or 5). Green and purple colors indicate the changes from Duox2 to Nox1 or Nox5 (Duox2→Nox(A)) and those from Duox1 to Nox1 or Nox5 (Duox1→Nox(A)), respectively. Various pairs were transfected into HEK293 cells. O2⨪ was measured by a chemiluminescence assay using Diogenes. Immunoblotting detects comparable expression levels of various Duox and DuoxA pairs.

In Vitro Binding (Pulldown) Assays

Forward and reverse oligonucleotides for DuoxA N terminus (1–20 aa for DuoxA1 or 1–19 aa for DuoxA2) were annealed and cloned into the BamHI and EcoRI sites of pGEX-6P-1. Purified GST and GST-tagged DuoxA N-terminal proteins (DuoxA1(N), GST-MATLGHTFPFYAGPKPTFP; DuoxA2(N), GST-MTLWNGVLPFYPQPRHAAG) were obtained as described previously (27). Biotin-labeled Duox A-loop peptides (Duox1(Aloop), biotin-AAHHTGITDTTRV; Duox2(Aloop), biotin-ALPPSDIAQTTLV) were synthesized by MBL International. GST-tagged DuoxA(N) was mixed with biotin-labeled Duox(Aloop) in 300 μl of binding buffer (500 nm each) (27). After rotation for 2 h at 4 °C, 40 μl of streptavidin-coupled magnetic beads (Dynabeads M-280 Streptavidin; Invitrogen) were added to the solution, and the mixture was agitated for 90 min at 4 °C. The precipitates were washed 3 times using a magnetic rack, and then the material absorbed to the beads was eluted in Laemmli sample buffer; the magnetic beads were then removed using a magnetic rack. The eluents were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting using a polyclonal antibody against GST (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Bound antibodies were detected with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody using the ECL detection system (GE Healthcare).

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

Various pairs of 2×HA-Duox and FLAG-tagged DuoxA constructs were co-transfected into HEK293 cells plated on 10-cm dishes using FuGENE 6 (Promega). Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were lysed in 250 μl of lysis buffer with a protease inhibitor mixture (27) by sonication. Total cell lysates were centrifuged at 800 × g for 5 min at 4 °C, and the supernatants were incubated with 10 μl of magnetic agarose-conjugated HA mAb for 2 h at 4 °C. The precipitates were washed 3 times, and aliquots of the precipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting using an HRP-conjugated FLAG mAb and detected using the ECL detection system.

N-Deglycosylation Analysis

The deglycosylation assay was performed as previously described (7). Briefly, various pairs of 2×HA-Duox and DuoxA constructs were co-transfected into HEK293 cells plated in 10-cm dishes using FuGENE 6. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were lysed in 250 μl of lysis buffer with a protease inhibitor mixture. After centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, equal amounts of proteins were treated with 100 units/50 μl of Endo H for 30 min at 37 °C or left untreated and separated by SDS-PAGE. Immunoblotting was performed using an HRP-conjugated HA mAb.

Confocal Fluorescence Imaging Studies

A total of 2.5 × 105 HEK293 cells were seeded in 35-mm glass-bottomed dishes (MatTek Corp.) 48 h before transfection and transfected using FuGENE 6. Thirty-two hours after transfection, the cells were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m PBS (pH 7.4) without permeabilization and stained using an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated HA mAb (1:500) at room temperature for 2 h for visualization by confocal laser scanning fluorescence microscopy (LSM700; Carl Zeiss AG). All imaging experiments were performed in triplicate and were repeated in at least three independent transfection experiments (n ≥ 9).

ROS Production Assay

HEK293 cells were seeded in 6-well dishes at 2.5 × 105 cells/well 48 h before transfection. HEK293 cells were transfected using FuGENE 6 in complexes with various combinations of plasmids. The cells were fed 6 h post-transfection with complete medium and harvested using 0.02% EDTA solution (Nacalai Tesque). Thirty-two hours after transfection, 2 × 105 cells in Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS(−); Wako Pure Chemical Industries) were used for ROS assays with 0.2 μm ionomycin (Sigma) + 2 mm Ca2+. Chemiluminescence methods were used in the presence of luminol + HRP (Sigma) for gross ROS detection (H2O2, O2⨪, and other non-identified ROS), superoxide dismutase-inhibitable Diogenes reagent (National Diagnostics) for O2⨪ detection, or Amplex Red (Invitrogen) + HRP for H2O2 detection for 10 min using a luminometer (Mithras LB940; Berthold Detection Systems GmbH) (28) as previously described (7, 29). O2⨪ production from 5 × 105 cells in 100 μl of HBSS(−) stimulated by 0.2 μm ionomycin + 2 mm Ca2+ was also measured based on the assay of cytochrome c (100 μm, Sigma) reduction with a molar extinction coefficient of 21 mm−1 cm−1 at 550 nm using a monochrometer (Multiskan GO; Thermo Fisher Scientific) as previously described (7, 30). O2⨪ production was inhibited by the addition of 10 units/ml superoxide dismutase (Sigma) in the assay solution. Comparable expression of proteins was confirmed by immunoblotting using total lysates from the same number of cells. Mean oxidase activities were calculated from at least three independent transfection experiments.

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as the means ± S.E. of mean. For comparisons of more than two groups, one-way analysis of variance was performed. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc.); p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

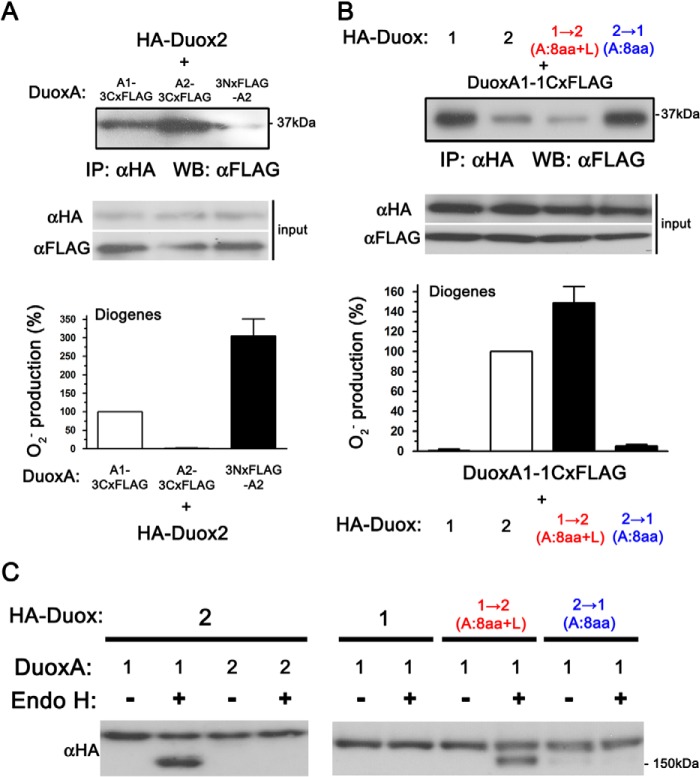

Tags at the N terminus of DuoxA2 Enhance O2⨪ Leakage from Matched Duox2-DuoxA2 Complexes

We previously demonstrated that co-expression of the mismatched Duox2 and DuoxA1, but not of Duox1 and DuoxA2, causes O2⨪ leakage into the extracellular milieu (7). In this study we found that co-expression of matched Duox2 and DuoxA2, but not of Duox1 and DuoxA1, caused a small amount of O2⨪ release (5.4 ± 0.6%) detected by Diogenes; this is consistent with the result of a previous report (31). To elucidate why only Duox2- and not Duox1-based combinations cause extracellular O2⨪ release, we created a series of N-terminally FLAG-tagged DuoxA1 and DuoxA2 constructs (Table 1). Interestingly, although C-terminally 3×FLAG-tagged DuoxA2 co-expressed with Duox2 did not enhance O2⨪ release, N-terminally tagged DuoxA2 dramatically enhanced the amount of O2⨪ release regardless of the number or type of epitope tags (Fig. 2A; 3N×FLAG, 291.2 ± 36.5%; 2N×FLAG, 387.4 ± 9.1%; 1N×FLAG, 543.9 ± 66.9%; 2N×HA, 465.4 ± 67.8%). Duox1 exhibited no O2⨪ leakage when co-expressed in any combination regardless of whether DuoxA was untagged, N-terminally 3×FLAG-tagged, or C-terminally 3×FLAG-tagged (Fig. 2A; data not shown). O2⨪ release by Duox2 with DuoxA1 or various types of N-terminally tagged DuoxA2 was confirmed by examining the effect of superoxide dismutase and/or through cytochrome c reduction assays (Fig. 2, A and B). The luminol + HRP assays were used to detect gross ROS production (H2O2, O2⨪, and other non-identified ROS) and to measure the ROS production capabilities in each Duox-DuoxA pair. Immunoblotting was performed to confirm comparable expression of constructs used (Fig. 2C). The results of these assays suggested that altered interactions between Duox2 and the N-terminal regions of its maturation factor, DuoxA2, cause increased O2⨪ leakage from this enzyme complex; the same was not observed in case of Duox1.

FIGURE 2.

O2⨪ leakage from Duox2 paired with N-terminally tagged DuoxA2. A, Various Duox and DuoxA pairs were transfected into HEK293 cells. O2⨪ and reactive oxygen species were measured by chemiluminescence assay using Diogenes and luminol + HRP, respectively. Duox2 + various types of N-terminally, but not C-terminally, tagged DuoxA2, show enhanced O2⨪ production. The superoxide dismutase (SOD) treatment was performed to validate the O2⨪ production for those samples where marked O2⨪ production was observed. B, various Duox and DuoxA pairs were transfected into HEK293 cells, and O2⨪ was measured by cytochrome c reduction assay. NADPH oxidase 1-based O2⨪ production was used as a positive control. All the samples were subjected to the superoxide dismutase treatment, except for Duox2-DuoxA2. C, immunoblotting detects expression levels of Duox2 and Duox1 in various pairs as well as the expression of FLAG- and HA-tagged DuoxAs.

The N-terminal Extracellular Region of DuoxA1 Plays a Pivotal Role in O2⨪ Release

DuoxA proteins have four TM segments, and their N-terminal regions are positioned on the extracytoplasmic membrane surface (6). When transported to the plasma membrane in complexes with Duoxes, the N termini of DuoxA proteins are detectable on the cell surface (7). To confirm the importance of the N-terminal extracellular regions of DuoxAs for O2⨪ leakage, we made two chimeric mutants of DuoxA1 and DuoxA2: DuoxA(1-2), in which the N-terminal extracellular region of DuoxA2 was substituted with that of DuoxA1, and DuoxA(2-1), in which the N-terminal extracellular region of DuoxA1 was substituted with that of DuoxA2 (Fig. 3A). When co-expressed with DuoxA(2-1), Duox2 exhibited no O2⨪ release (Fig. 3B); in contrast, when co-expressed with DuoxA(1-2), Duox2 showed markedly enhanced O2⨪ release (Fig. 3B). To define the specific aa sequence in the N-terminal extracellular region of DuoxA(1-2) that influences O2⨪ release, we made two additional chimeric mutants of DuoxA(1-2): DuoxA(1F-2), in which only the first half of the N-terminal extracellular region of DuoxA2 was substituted with that of DuoxA1, and DuoxA(2-1S-2), in which only the second half of the N-terminal extracellular region of DuoxA2 was substituted with that of DuoxA1 (Fig. 3A). O2⨪ release from Duox2 with DuoxA(1F-2) or DuoxA(2-1S-2) was similar, at about one-third that from Duox2 + DuoxA(1-2) (Fig. 3B). Duox1 with DuoxA(2-1) or DuoxA(1-2) showed no O2⨪ release (Fig. 3B). Comparable expression of constructs was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 3B). DuoxA1 pAb detected only WT DuoxA1 and not DuoxA1 chimeras. These results suggest that the entire N-terminal, extracellular region of DuoxA1 has a strong influence on O2⨪ release when expressed in combination with Duox2.

The Extracellular Region(s) after the First TM Segment of Duox2 Is Key to O2⨪ Release

To explore the regions of Duox involved in O2⨪ release, we made two chimeric Duox mutants: Duox(2PoxH-1), in which PoxH domain of Duox1 was substituted with that of Duox2, and Duox(1PoxH-2), in which the PoxH domain of Duox2 was substituted with that of Duox1 (Fig. 4A). Three combinations, Duox2-DuoxA1, Duox(1PoxH-2)-DuoxA1, and Duox(1PoxH-2)-DuoxA(1-2) (highlighted by two-way red arrows in Fig. 4B), showed O2⨪ release. All these combinations contained the common Duox2 portion starting with the first TM segment and the N-terminal extracellular region of DuoxA1. Comparable expression of constructs was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that the extracellular region(s) after the first TM segment of Duox2 and the N-terminal extracellular region of DuoxA1 affect O2⨪ leakage.

The A-loops of Duoxes, but Not the C- or E-loops, Affect O2⨪ Release

To identify the extracellular region after the first TM segment of Duox2 involved in O2⨪ release in cooperation with the N-terminal extracellular region of DuoxA1, we focused on three extracellular regions of Duoxes, A-, C-, and E-loop (Fig. 1A). Because Duoxes, like all Nox enzymes, donate electrons to molecular oxygen in the extracytoplasmic compartment, we did not examine the roles of the intracellular EF-hand motifs or the B- or D-loops in O2⨪ release. These loops were defined in reference to previous papers (4, 23) and using websites that predict the secondary structures of membrane proteins (SOSUI WWW Server; TMHMM Server). We hypothesized that if a particular extracellular loop of Duox2 was involved in O2⨪ release, then chimeric mutants in which this loop of Duox2 is replaced with that of Duox1 would exhibit reduced O2⨪ leakage. To explore this hypothesis, we first made two chimeric mutants of Duox2 possessing the A-loop sequences of Duox1: Duox2→1(A:5aa) and Duox2→1(A:8aa) (Fig. 5A). O2⨪ release by Duox2→1(A:5aa)-DuoxA1 and Duox2→1(A:8aa)-DuoxA1 was dramatically reduced relative to the Duox2-DuoxA1 complex (2.27 ± 0.81% and 0.83 ± 0.38%, respectively; Fig. 5B). To confirm these results, we made three reverted chimeric mutants of Duox1 possessing some A-loop sequence from Duox2: Duox1→2(A:F4aa), Duox1→2(A:S4aa), and Duox1→2(A:8aa) (Fig. 5A). Although Duox1→2(A:F4aa) and Duox1→2(A:S4aa) showed no O2⨪ release, Duox1→2(A:8aa) co-expressed with DuoxA1 did show O2⨪ release (67.4 ± 8.9%) but to a lesser extent than that by Duox2-DuoxA1 (Fig. 5B). Duox1→2(A:8aa) maintained capabilities to secret H2O2, which were detected by Amplex Red + HRP, as in the case of Duox1 and Duox2 (Fig. 5B). We then made two additional Duox1 mutants: Duox1→2(A:8aa+L) and Duox1→2(A:8aa+GL) (Table 1). In Duox1→2(A:8aa+GL), the entire A-loop aa sequence of Duox1 was replaced with that of Duox2. O2⨪ release from Duox1→2(A:8aa+L)-DuoxA1 (146.9 ± 16.7%) and Duox1→2(A:8aa+GL)-DuoxA1 (101.4 ± 19.3%) matched that from Duox2-DuoxA1 (Fig. 5C); therefore, Duox1→2(A:8aa+L) was used for further studies.

To examine which aa residues in the A-loop of Duox1 are critical for the reduction of O2⨪ release, we made various mutants in which one or two aa residues in the A-loop of Duox1→2(A:8aa+L) were reverted to those of Duox1. Changing Pro1068-Pro1069 into His-His (PP/HH) and Asp1071 into Gly (D/G) almost completely abolished O2⨪ release (ROS production detected by luminol + HRP was 57.4 ± 8.3% and 54.9 ± 6.9%, respectively). In contrast, changing Leu1067 into Ala (L/A), Ala1073 into Thr (A/T), and Gln1074 into Asp (Q/D) caused moderate effects. Replacement of either Pro residue with His was sufficient to abolish O2⨪ release by Duox1→2(A:8aa+L); this was confirmed using PP/HP and PP/PH mutations in Duox1→2(A:8aa+L) (data not shown). In addition, although the expression levels of Duox1→2(A:PPD), in which three critical residues (HH+G) in the A-loop of Duox1 were exchanged for those of Duox2, were apparently low (ROS production detected by luminol + HRP was 36.8 ± 10.8%), it showed no O2⨪ release (Fig. 5C). Taken together, these results suggest that these specific residues alone do not account for the function of the Duox A-loop in preventing O2⨪ release. Comparable expression of constructs was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 5, B and C).

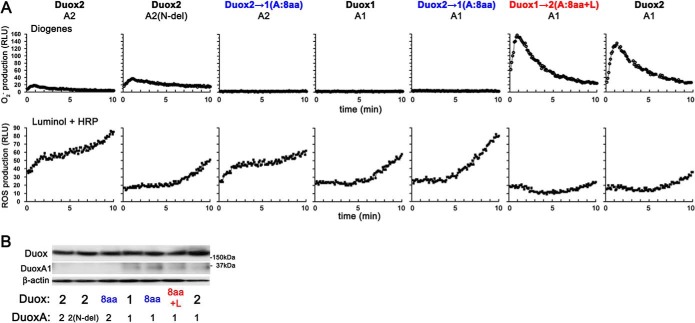

Next, we examined the kinetics of O2⨪ and ROS production (detected by Diogenes and luminol + HRP, respectively) from various Duox + DuoxA pairs: Duox2-DuoxA2, Duox2-DuoxA2(N-del), Duox2→1(A:8aa)-DuoxA2, Duox1-DuoxA1, Duox2→1(A:8aa)-DuoxA1, Duox1→2(A:8aa+L)-DuoxA1, and Duox2-DuoxA1. Duox1→2(A:8aa+L)-DuoxA1 and Duox2-DuoxA1 showed very similar kinetic curves in terms of both O2⨪ and ROS production (Fig. 6A). Duox2→1(A:8aa)-DuoxA1 showed a kinetic curve of ROS production similar to that of Duox1-DuoxA1 (Fig. 6A). Duox2-DuoxA2(N-del) showed an increase in O2⨪ release and a decrease in ROS production compared with Duox2-DuoxA2 (Fig. 6A). Duox2→1(A:8aa+L)-DuoxA2 did not show any O2⨪ release (Fig. 6A). In the Duox1-DuoxA1(N-del) pair, ROS production was severely impaired (<10% that of Duox1-DuoxA1), and no apparent plasma membrane targeting/localization of Duox1 or O2⨪ release was observed (data not shown). Comparable expression of constructs was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 6B).

FIGURE 6.

Kinetics of O2⨪ and ROS production. A, various pairs, including HA-Duox2-DuoxA2, HA-Duox2-DuoxA2(N-del), HA-Duox2→1(A:8aa)-DuoxA2, HA-Duox1-DuoxA1, HA-Duox2→1(A:8aa)-DuoxA1, HA-Duox1→2(A:8aa+L)-DuoxA1, and HA-Duox2-DuoxA1, were transfected into HEK293 cells. Representative (n ≥ 3) kinetics of O2⨪ and reactive oxygen species production measured by chemiluminescence assay using Diogenes and luminol + HRP, respectively, are shown. B, immunoblotting detects comparable expression levels of various Duox and DuoxA pairs.

Finally, we assessed the involvement of the C- and E-loops in O2⨪ release using chimeric mutants in which their sequences in Duox2 were replaced with those of Duox1 (Fig. 7, A and C). O2⨪ release was not reduced in either the C-loop mutant, Duox2→1(C:10aa), or the E-loop mutant, Duox2→1(E:TY/RF) (Fig. 7, B and D). Comparable expression of constructs was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 7, B and D). Taken together, we conclude that the A-loop, but not the C- or E-loop, of Duox2 is involved in O2⨪ release.

The A-loops of Both Duox1 and Duox2 Function in Reducing O2⨪ Leakage

To further investigate the mechanism underlying the reduction of O2⨪ release by the Duox A-loop, we made chimeric Duox proteins possessing the A-loops of Nox1 or Nox5 (23, 32) (Fig. 8A). Duox2 possessing the A-loop of Nox1 or Nox5 showed markedly enhanced O2⨪ release in matched combination with DuoxA2 in comparison with the native Duox2-DuoxA2 complex (Fig. 8B), suggesting that the A-loop of Duox2 also functions in the reduction of O2⨪ release. Furthermore, Duox1 possessing the A-loop of Nox1 or Nox5 exhibited O2⨪ release even when matched with DuoxA1 (Fig. 8B). Comparable expression of constructs was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 8B). Taken together, these observations imply that the A-loops of both Duox1 and Duox2 function in reducing O2⨪ release, although it appears that the A-loop of Duox1 is more effective in reducing O2⨪ release.

Stable and Mature Duox-DuoxA Complex Formation Is Required for H2O2 Production

To examine the hypothesis that the A-loops of Duoxes have the intrinsic ability to convert O2⨪ to H2O2, we synthesized oligopeptides of the A-loops of Duox1 and Duox2. We performed the following experiments: 1) adding A-loop peptides into xanthine oxidase reactions generating O2⨪ to detect its conversion and 2) adding A-loop peptides into Diogenes-based O2⨪ assays in heterologous Duox-reconstituted cell systems. However, these experiments failed to reduce O2⨪ production (data not shown), suggesting that the A-loops of Duoxes have no O2⨪ dismutation activity.

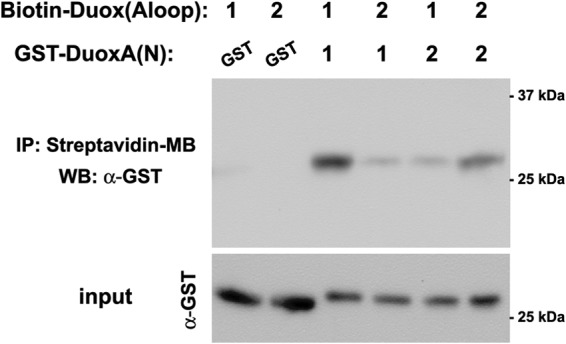

Next, we investigated possible direct interaction between the biotin-labeled A-loop peptides of Duoxes and the GST-tagged N-terminal extracellular sequences of the DuoxAs by pulldown assays using streptavidin-conjugated magnetic beads. We detected the strongest interaction between Duox1(Aloop) and DuoxA1(N) among Duox1(Aloop)-DuoxA1(N), Duox2(Aloop)-DuoxA2(N), Duox1(Aloop)-DuoxA2(N), and Duox2(Aloop)-DuoxA1(N) pairs (Fig. 9).

FIGURE 9.

Direct binding of the Duox A-loop to the DuoxA N terminus. Purified GST-tagged DuoxA N terminus was mixed with synthesized biotin-labeled Duox A-loop in binding buffer. IP, immunoprecipitation. Then, streptavidin-coupled magnetic beads were added 2 h later. The material absorbed to the beads was eluted in Laemmli sample buffer. The eluents were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting (WB) using a polyclonal antibody against GST. The strongest interaction was observed between Duox1(Aloop) and DuoxA1(N) relative to Duox2(Aloop) + DuoxA2(N), Duox1(Aloop) + DuoxA2(N), and Duox2(Aloop) + DuoxA1(N) (n ≥ 3).

We then focused on the interaction between full-length Duoxes and DuoxAs at the cellular level because our previous paper established that Duox maturation, reflected in N-glycosyl modifications and stable interactions with DuoxAs, affects the type of ROS produced in that fully processed and stable complexes do not leak O2⨪ (7). The relationship between O2⨪ release and Duox binding to DuoxAs was examined by immunoprecipitation assays using lysates from HEK293 cells transfected with various Duox and DuoxA combinations. The order of the strength of Duox2 binding to FLAG-tagged DuoxAs was 3N×FLAG-DuoxA2 < DuoxA1–3C×FLAG < DuoxA2–3C×FLAG (Fig. 10A). This order inversely correlated with the amount of O2⨪ release by the Duox2 complex: 3N×FLAG-DuoxA2 > DuoxA1–3C×FLAG > DuoxA2–3C×FLAG (Fig. 10A). The order of the strength of DuoxA1 binding to HA-tagged Duoxes was HA-Duox1→2(A:8aa+L) < HA-Duox2 < HA-Duox1 = HA-Duox2→1(A:8aa) (Fig. 10B). This order also inversely correlated with the amount of O2⨪ release: HA-Duox1→2(A:8aa+ L) > HA-Duox2 > HA-Duox1 = HA-Duox2→1(A:8aa) (Fig. 10B), suggesting that stable interactions between Duoxes and DuoxAs prevent O2⨪ release. Comparable plasma membrane targeting/localization of these seven pairs was statistically confirmed by the nonpermeable immunostaining of HA-tagged Duoxes using an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated HA mAb (data not shown).

FIGURE 10.

The A-loop of Duox is associated with binding to DuoxA, O2⨪ leakage, and Endo H-resistant N-glycosyl modification. A and B, HA-tagged Duox2 + various types of FLAG-tagged DuoxA (A) or various types of HA-Duox + DuoxA1–1C×FLAG (B) were transfected into HEK293 cell. Forty-eight hours after transfection lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) by a magnetic agarose-conjugated HA mAb followed by immunoblotting (WB) using an HRP-conjugated FLAG mAb. Representative data (n ≥ 3) show good correlation between a weak interaction between Duox and DuoxA and high O2⨪ production. C, various HA-tagged Duox and DuoxA pairs were transfected into HEK293 cell. Forty-eight hours after transfection lysates were treated with Endo H, and immunoblotting was performed using an HRP-conjugated HA mAb. Representative data (n ≥ 3) show the presence of Endo H-sensitive bands in O2⨪ producing pairs (HA-Duox2 + DuoxA1 and HA-Duox1→2(A:8aa+L) + DuoxA1).

To explore the relationship between Duox maturation (Golgi apparatus-based glycosyl modifications) and O2⨪ release, Endo H treatments were performed. Duox2-DuoxA1 complexes that showed O2⨪ release was sensitive to Endo H treatment (Fig. 10C, left). Interestingly, although the Duox1→2(A:8aa+L)-DuoxA1 complex showed glycosyl modifications of Duox1→2(A:8aa+L) similar to that of Duox1 in the Duox1-DuoxA1 complex, the Duox1→2(A:8aa+L)-DuoxA1 complex that exhibited O2⨪ release was also susceptible to Endo H treatment (Fig. 10C, right). Conversely, Duox2→1(A:8aa)-DuoxA1, which produced H2O2 but no O2⨪, was resistant to Endo H treatment (Fig. 10C, right). Taken together, these results suggest that the A-loop of Duox1 functions to promote the formation of stable and mature Duox1-DuoxA1 complexes, preventing O2⨪ release.

DISCUSSION

Duox enzymes serve as dedicated H2O2 generators at the plasma membrane, where they support the activities of extracellular hemoperoxidases (22). We (7) and another group (26) previously reported a switch in the type of ROS released, from H2O2 to O2⨪, with co-expression of the mismatched Duox2 and DuoxA1 pair, but not with Duox1 and DuoxA2 (7). These findings suggest that DuoxA proteins contribute to Duox maturation and subcellular targeting; they also function as a part of the ROS-generating complex. Subsequently, Hoste et al. (31) showed that the N terminus of DuoxA2 acts as an important determinant of the type of ROS produced by Duox2 by comparing native DuoxA2 with N-terminally truncated and chimeric versions of DuoxA2 and DuoxA1. Consistent with our results, they showed that 1) the addition of tags of various types and lengths to the N-terminal of DuoxA2 increased the amount of O2⨪ leakage by Duox2 (rhodopsin (19 aa) and FLAG (8 aa) tags (31); FLAG (22 aa in 3N×FLAG, 15 aa in 2N×FLAG, and 8 aa in 1N×FLAG), and 2N×HA (20 aa) tags (this study)) and 2) a small amount of O2⨪ is released by the native Duox2-DuoxA2 complex but not by the Duox1-DuoxA1 or Duox1-DuoxA2 complexes (31).

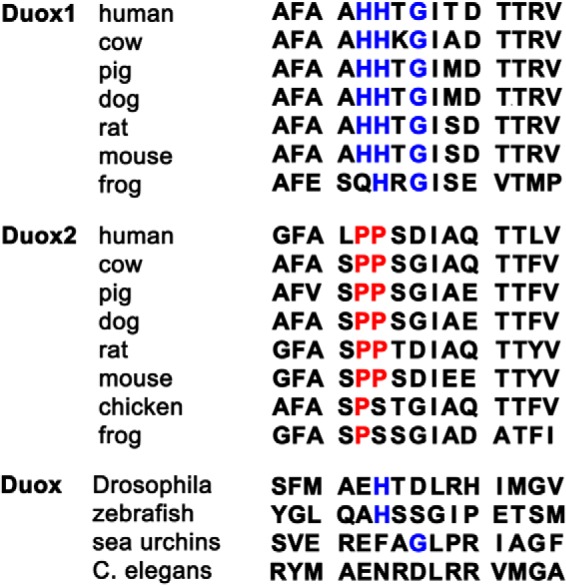

In this study we expanded upon these observations on ROS generation by Duoxes by identifying novel structural determinants within the Nox-like extracellular portion of Duoxes, termed the A-loop, that appears to function in preventing O2⨪ leakage by supporting the stabilization and maturation of the Duox-DuoxA complex. Although the A-loop of Duox1 is more effective at preventing O2⨪ leakage than that of Duox2, the A-loops of both the Duox isozymes function in preventing O2⨪ release (Fig. 8). A recent study (33) showed that Nox4 has a unique extracellular E-loop, longer than that in other Nox family proteins, which was proposed to hinder O2⨪ release and facilitate its conversion to H2O2. Interestingly, this study highlighted the importance of His222 of Nox4, proposing that this conserved residue serves as a source of protons for O2⨪ dismutation. However, we found that neither the E-loop nor the C-loop aa sequences of either Duox influenced O2⨪ release by Duox-DuoxA complexes. The PoxH domain of Duoxes is a candidate for intramolecular O2⨪ dismutation, although the isolated domains of both Duox isozymes did not demonstrate superoxide dismutase or peroxidase activity in vitro (24, 25). In this study we observed reduced O2⨪ release by Duox(1PoxH-2)-DuoxA1 than by Duox2-DuoxA1 (Fig. 4), suggesting that the PoxH domain of Duox1 could reduce O2⨪ leakage by supporting its conversion to H2O2. Three residues in the A-loop of Duox1 (HH and G) critical for the reduction of O2⨪ leakage are highly conserved in Duox1 in many species (Fig. 11), and the corresponding PP residues in the A-loop of Duox2 are also well conserved in many species. The A-loop sequences of human Duox1 and Duox2 have different predicted secondary structures as analyzed by several structural modeling algorithms (cfPred: Chou-Fasman Protein Secondary Structure Predictor), suggesting that the A-loops of Duox1 and Duox2 interact differently with other structures involved in the conversion of O2⨪ to H2O2 (i.e. the DuoxA N termini or Duox PoxH domains). These structural differences may explain the observed differences in O2⨪ leakage, complex stability, and maturation. The A-loops of Nox1 and Nox5, which produce O2⨪, also lack HH residues and are even more divergent, consistent with their effects in inducing or enhancing O2⨪ release by chimeric Duox1 or Duox2 proteins, respectively (Fig. 8). Moreover, the compound heterozygous mutation of Duox2(L1067S) in the A-loop combined with other Duox2 mutations was identified in patients with transient congenital hypothyroidism (12), further supporting the importance of the A-loop structure to Duox function.

FIGURE 11.

Alignment of the A-loops of Duox in many species. Chicken, Drosophila, zebrafish, sea urchins, and Caenorhabditis elegans each have only one Duox. Blue letters in Duox1 and Duox and red letters in Duox2 indicate highly conserved residues between species.

We found direct binding of the A-loops of Duoxes to the N termini of DuoxAs in vitro (Fig. 9). In addition, the strength of the interaction between the Duox and DuoxA pairs at the cellular level inversely correlated with the amount of O2⨪ released-weaker interactions correlated with greater O2⨪ leakage (Fig. 10, A and B). Furthermore, the A-loop of Duox1 induced complete Endo H-resistant glycosyl modifications of Duoxes (Fig. 10C). To determine whether glycosyl modifications of Duoxes affect ROS production and O2⨪ leakage, we created glycosylation-defective mutants of untagged and HA-tagged human Duox1 and Duox2 in which all five putative glycosylation sites (4) (Asn-94, -342, -354, -461, and -534 in Duox1; Asn-100, -348, -382, -455, and -537 in Duox2) were replaced by Gln. In Duox-reconstituted HEK293 cell systems, these mutants showed severely impaired glycosylation (almost no band shift in Duoxes upon immunoblotting), plasma membrane targeting/localization of the Duox-DuoxA complex, and ROS production or O2⨪ leakage detected by luminol + HRP or Diogenes (data not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that 1) binding of the A-loop of Duox1 to the N terminus of DuoxA1 contributes to the enhanced interaction between Duox1 and DuoxA1 observed at the cellular level, thereby inducing more stable, mature Duox-DuoxA complexes than those involving Duox2, and 2) glycosyl modifications of Duoxes are essential for the targeting/localization of the Duox-DuoxA complex to the plasma membrane, increasing the stability of the Duox-DuoxA complex and developing capabilities for ROS production (including O2⨪ leakage) on the plasma membrane. The formation of more stable Duox-DuoxA heterodimers or structural changes associated with maturation, which are probably acquired at the final destination, the apical cell surface, may create an environment that more efficiently supports ROS conversion and prevents O2⨪ leakage.

In conclusion, in this study we demonstrated that the A-loop of Duoxes is an important structural determinant that interacts with the N termini of DuoxAs and facilitates the conversion of O2⨪ to H2O2, likely through mechanisms promoting the stabilization and maturation of Duox-DuoxA complexes. Further studies are required to unveil the detailed mechanisms underlying the intramolecular conversion of O2⨪ to H2O2 by the Duox-DuoxA complex.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the Intramural Research Program of the NIAID, National Institutes of Health. This work was also supported in part by a grant-in-aid for Scientific Research (C) of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan, by a grant “Japan-Hungary Research Cooperative Program” from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, by the Uehara Memorial Foundation, and by the Hyogo Science and Technology Association.

- Duox

- Dual oxidase

- Nox

- NADPH oxidase

- DuoxA

- Duox activator

- O2⨪

- superoxide

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- PoxH

- peroxidase homology

- Endo H

- endoglycosidase H

- TM

- transmembrane

- pAb

- polyclonal antibody

- HBSS

- Hank's balanced Salt Solution

- aa

- amino acids.

REFERENCES

- 1. Quinn M. T., Ammons M. C., Deleo F. R. (2006) The expanding role of NADPH oxidases in health and disease: no longer just agents of death and destruction. Clin. Sci. 111, 1–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Leto T. L., Morand S., Hurt D., Ueyama T. (2009) Targeting and regulation of reactive oxygen species generation by Nox family NADPH oxidases. Antioxid. Redox. Signal 11, 2607–2619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Matsushima S., Tsutsui H., Sadoshima J. (2014) Physiological and pathological functions of NADPH oxidases during myocardial ischemia-reperfusion. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 24, 202–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. De Deken X., Wang D., Many M. C., Costagliola S., Libert F., Vassart G., Dumont J. E., Miot F. (2000) Cloning of two human thyroid cDNAs encoding new members of the NADPH oxidase family. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 23227–23233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dupuy C., Ohayon R., Valent A., Noël-Hudson M. S., Dème D., Virion A. (1999) Purification of a novel flavoprotein involved in the thyroid NADPH oxidase. Cloning of the porcine and human cdnas. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 37265–37269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grasberger H., Refetoff S. (2006) Identification of the maturation factor for dual oxidase. Evolution of an eukaryotic operon equivalent. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 18269–18272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Morand S., Ueyama T., Tsujibe S., Saito N., Korzeniowska A., Leto T. L. (2009) Duox maturation factors form cell surface complexes with Duox affecting the specificity of reactive oxygen species generation. FASEB J. 23, 1205–1218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moreno J. C., Pauws E., van Kampen A. H., Jedlicková M., de Vijlder J. J., Ris-Stalpers C. (2001) Cloning of tissue-specific genes using serial analysis of gene expression and a novel computational substraction approach. Genomics 75, 70–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Johnson K. R., Marden C. C., Ward-Bailey P., Gagnon L. H., Bronson R. T., Donahue L. R. (2007) Congenital hypothyroidism, dwarfism, and hearing impairment caused by a missense mutation in the mouse dual oxidase 2 gene, Duox2. Mol. Endocrinol. 21, 1593–1602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grasberger H., De Deken X., Mayo O. B., Raad H., Weiss M., Liao X. H., Refetoff S. (2012) Mice deficient in dual oxidase maturation factors are severely hypothyroid. Mol. Endocrinol. 26, 481–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Donkó A., Ruisanchez E., Orient A., Enyedi B., Kapui R., Péterfi Z., de Deken X., Benyó Z., Geiszt M. (2010) Urothelial cells produce hydrogen peroxide through the activation of Duox1. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 49, 2040–2048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maruo Y., Takahashi H., Soeda I., Nishikura N., Matsui K., Ota Y., Mimura Y., Mori A., Sato H., Takeuchi Y. (2008) Transient congenital hypothyroidism caused by biallelic mutations of the dual oxidase 2 gene in Japanese patients detected by a neonatal screening program. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 93, 4261–4267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hulur I., Hermanns P., Nestoris C., Heger S., Refetoff S., Pohlenz J., Grasberger H. (2011) A single copy of the recently identified dual oxidase maturation factor (DUOXA) 1 gene produces only mild transient hypothyroidism in a patient with a novel biallelic DUOXA2 mutation and monoallelic DUOXA1 deletion. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 96, E841–E845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Geiszt M., Witta J., Baffi J., Lekstrom K., Leto T. L. (2003) Dual oxidases represent novel hydrogen peroxide sources supporting mucosal surface host defense. FASEB J. 17, 1502–1504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. El Hassani R. A., Benfares N., Caillou B., Talbot M., Sabourin J. C., Belotte V., Morand S., Gnidehou S., Agnandji D., Ohayon R., Kaniewski J., Noël-Hudson M. S., Bidart J. M., Schlumberger M., Virion A., Dupuy C. (2005) Dual oxidase2 is expressed all along the digestive tract. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 288, G933–G942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. van der Vliet A. (2011) Nox enzymes in allergic airway inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1810, 1035–1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ha E. M., Oh C. T., Bae Y. S., Lee W. J. (2005) A direct role for dual oxidase in Drosophila gut immunity. Science 310, 847–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moskwa P., Lorentzen D., Excoffon K. J., Zabner J., McCray P. B., Jr., Nauseef W. M., Dupuy C., Bánfi B. (2007) A novel host defense system of airways is defective in cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 175, 174–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grasberger H., El-Zaatari M., Dang D. T., Merchant J. L. (2013) Dual oxidases control release of hydrogen peroxide by the gastric epithelium to prevent helicobacter felis infection and inflammation in mice. Gastroenterology 145, 1045–1054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sumimoto H. (2008) Structure, regulation and evolution of Nox-family NADPH oxidases that produce reactive oxygen species. FEBS J. 275, 3249–3277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ameziane-El-Hassani R., Morand S., Boucher J. L., Frapart Y. M., Apostolou D., Agnandji D., Gnidehou S., Ohayon R., Noël-Hudson M. S., Francon J., Lalaoui K., Virion A., Dupuy C. (2005) Dual oxidase-2 has an intrinsic Ca2+-dependent H2O2-generating activity. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 30046–30054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. De Deken X., Corvilain B., Dumont J. E., Miot F. (2014) Roles of DUOX-mediated hydrogen peroxide in metabolism, host defense, and signaling. Antioxid. Redox. Signal 20, 2776–2793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kawahara T., Quinn M. T., Lambeth J. D. (2007) Molecular evolution of the reactive oxygen-generating NADPH oxidase (Nox/Duox) family of enzymes. BMC Evol. Biol. 7, 109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Meitzler J. L., Ortiz de Montellano P. R. (2009) Caenorhabditis elegans and human dual oxidase 1 (DUOX1) “peroxidase” domains: insights into heme binding and catalytic activity. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 18634–18643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Meitzler J. L., Ortiz de Montellano P. R. (2011) Structural stability and heme binding potential of the truncated human dual oxidase 2 (DUOX2) peroxidase domain. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 512, 197–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zamproni I., Grasberger H., Cortinovis F., Vigone M. C., Chiumello G., Mora S., Onigata K., Fugazzola L., Refetoff S., Persani L., Weber G. (2008) Biallelic inactivation of the dual oxidase maturation factor 2 (DUOXA2) gene as a novel cause of congenital hypothyroidism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 93, 605–610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ueyama T., Tatsuno T., Kawasaki T., Tsujibe S., Shirai Y., Sumimoto H., Leto T. L., Saito N. (2007) A regulated adaptor function of p40phox: distinct p67phox membrane targeting by p40phox and by p47phox. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 441–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nauseef W. M. (2014) Detection of superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide production by cellular NADPH oxidases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1840, 757–767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ueyama T., Son J., Kobayashi T., Hamada T., Nakamura T., Sakaguchi H., Shirafuji T., Saito N. (2013) Negative charges in the flexible N-terminal domain of rho GDP-dissociation inhibitors (RhoGDIs) regulate the targeting of the RhoGDI-Rac1 complex to membranes. J. Immunol. 191, 2560–2569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pick E. (2014) Cell-free NADPH oxidase activation assays: “in vitro veritas.” Methods Mol. Biol. 1124, 339–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hoste C., Dumont J. E., Miot F., De Deken X. (2012) The type of DUOX-dependent ROS production is dictated by defined sequences in DUOXA. Exp. Cell Res. 318, 2353–2364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cheng G., Cao Z., Xu X., van Meir E. G., Lambeth J. D. (2001) Homologs of gp91phox: cloning and tissue expression of Nox3, Nox4, and Nox5. Gene 269, 131–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Takac I., Schröder K., Zhang L., Lardy B., Anilkumar N., Lambeth J. D., Shah A. M., Morel F., Brandes R. P. (2011) The E-loop is involved in hydrogen peroxide formation by the NADPH oxidase Nox4. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 13304–13313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]