Abstract

Purpose

About one in five men living with HIV in the USA passes through a correctional center annually. Jails and prisons are seen therefore as key intervention sites to promote HIV treatment as prevention. Almost no research, however, has examined inmates' perspectives on HIV treatment or their strategies for retaining access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) during incarceration. The purpose of this paper is to describe the results of an exploratory study examining men's perceptions of and experiences with HIV care and ART during incarceration.

Design/methodology/approach

Semi-structured, in-depth interviews were conducted with 42 HIV positive male and male-to-female transgendered persons recently released from male correctional centers in Illinois, USA.

Findings

Interpersonal violence, a lack of safety, and perceived threats to privacy were frequently cited barriers to one's willingness and ability to access and adhere to treatment. Over 60 percent of study participants reported missed doses or sustained treatment interruption (greater than two weeks) because of failure to disclose their HIV status, delayed prescribing, intermittent dosing and out-of-stock medications, confiscation of medications, and medication strikes.

Research limitations/implications

Substantial improvements in ART access and adherence are likely to follow organizational changes that make incarcerated men feel safer, facilitate HIV status disclosure, and better protect the confidentiality of inmates receiving ART.

Originality/value

This study identified novel causes of ART non-adherence among prisoners and provides first-hand information about how violence, stigma, and the pursuit of social support influence prisoner's decisions to disclose their HIV status or accept ART during incarceration.

Keywords: Prisoners, Stigma, Privacy, HIV/AIDS, Violence, Adherence, Antiretroviral therapy

Nearly 20 percent of men living with HIV in the USA pass through a correctional center (CC) annually (Spaulding et al., 2009). Jails and prisons are seen therefore as key intervention sites to diagnose, treat, and prevent future HIV transmission among criminal justice system (CJS) populations (Beckwith et al., 2010). CCs may, in some cases, provide structured settings that contribute to medication adherence and improved virological and immunological outcomes (Wohl et al., 2003; Springer et al., 2004, 2007). Many opportunities to diagnose HIV in CCs are still missed, however, due to lack of routine HIV screening (Duffus et al., 2009; Flanigan et al., 2010). In an effort to increase the number of HIV-infected persons in the USA benefitting from treatment, the National Institutes of Health has specifically funded a multi-site “Seek, Test, Treat, and Retain” research initiative which means to improve the identification of untreated cases of HIV infection in CJS populations and linkage and access to medical care for persons leaving jails and prisons (NIH, 2010).

Detecting and treating HIV in CCs remains complex and challenging. There is a lack of consensus about how to organize health services in CCs in a way that balances efficiency, safety, and privacy (Springer and Altice, 2005). Research is showing that HIV testing in CCs can be feasible and acceptable to inmates (Kacanek et al., 2007; Sagnelli et al., 2012). We know less, however, about why some HIV-infected men refuse HIV testing or how prisoners cope with an HIV diagnosis in jail/prison. There is also a lack of clear evidence about the best way to provide antiretroviral therapy (ART) to inmates (Springer and Altice, 2005; Roberson et al., 2009; Pontali, 2005), and adherence to ART frequently remains suboptimal despite tightly regulated administration of ART in custodial settings (Altice et al., 2001; Wohl et al., 2003). Most importantly, despite improving standards for correctional healthcare (Rold, 2008), prisoners too often view the provision of correctional health services as unjust, degrading, and dangerous (de Viggiani, 2007; Condon et al., 2007).

A shared set of cultural beliefs about the unwritten social rules in jails/prisons likely guide men's decisions to participate in HIV testing, to disclose their HIV status, or to request ART during incarceration (Culbert, 2011). Yet only a few qualitative studies have explored inmates' beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors related to taking ART inside a CC (Altice et al., 2001; Small et al., 2009; Esposito, 2012). These researchers have warned that violence, a lack of trust, and privacy concerns can impede health service utilization by HIV-infected prisoners. We still do not know, however, why some men refuse ART during incarceration or how men taking ART maintain their privacy in a closed environment. This is among the first studies conducted in the USA to explore how prisoners faced with a decision about whether or not to take ART view and respond to these constraints. To optimize HIV treatment during incarceration and improve adherence to ART after release, we urgently need to understand how HIV-infected inmates perceive and respond to health services.

The purpose of this study was to describe the perceived risks of accepting ART during incarceration and to examine the social context of HIV care in Illinois jails and prisons as it is experienced by inmates. Using data from semi-structured, in-depth interviews with recently released male (and male-to-female) participants (n=42), this study identified three interrelated themes including perceptions of violence; fear of stigma and alienation; and pursuing protection and social support from other inmates, that are directly relevant for understanding whether, how, and why HIV-infected men access HIV care and adhere to ART during incarceration. Jails and prisons perceived as unsafe are not conducive to the treatment of HIV because inmates often believe an HIV-positive status raises their chances of being subjected to violence. This more immediate concern overrides concern about HIV. The setting of this study was very specific (Chicago, Illinois, USA) and results cannot be generalized to other jail/prison settings, even in the USA. Nonetheless, these findings have important implications for delivering HIV care in jails/prisons, and readying these sites to promote HIV treatment as prevention. Incarcerated men have a lot to say about how to make health services in jails/prisons more accessible and acceptable. Given important new evidence about the impact of ART on preventing HIV transmission (Cohen et al., 2011), it is essential to make ART widely available to inmates by incorporating their perspectives into planning and organizing the provision of ART in jails/prisons. This study fills a significant gap in the scientific literature by describing what makes HIV care accessible and acceptable to HIV positive men who become incarcerated.

Methods

Study sites

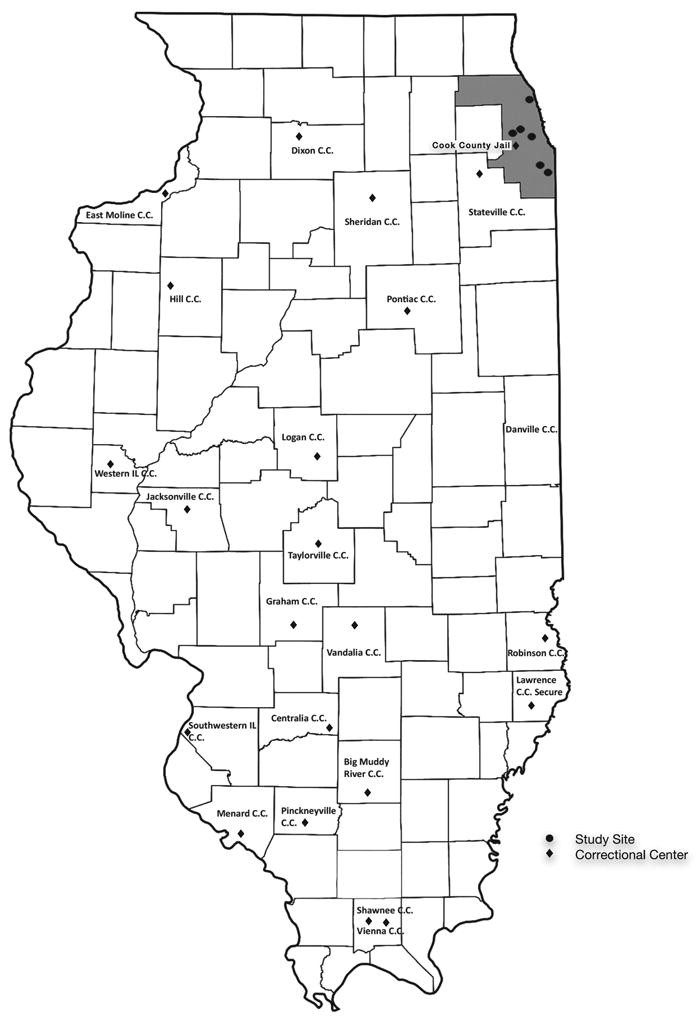

This study was conducted at six community HIV clinics located in medically underserved Chicago neighborhoods. Like other major cities in the USA, Chicago is disproportionately affected by HIV and incarceration. The HIV prevalence rate in Chicago (756.5/100,000) is about three times the national average (Chicago Department of Public Health, 2011). Almost 80 percent of the 20,391 people known to be living with HIV infection in Chicago are male. Each year, Chicago (Cook County) receives over half (54 percent) of all male prison parolees in the State of Illinois (Illinois Department of Corrections (IDOC), 2010). Most of these men return to Chicago community areas with elevated rates of HIV and other measures of social inequality (LaVigne and Mamalian, 2003; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study sites and correctional centers by Illinois county.

The sites chosen for this study included five clinics operated by the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC), HIV Community Clinic Network and located in the field stations of the Community Outreach Intervention Projects, and a Corrections Continuity Clinic operated by the Ruth M. Rothstein CORE Center that provides HIV primary care to adults leaving Cook County Jail, the largest jail in the USA, and the Illinois Department of Corrections. Most patients served through these clinics are economically disadvantaged and receive public funding to support their use of community health services. The study protocol was approved by Institutional Review Boards at UIC and the Cook County Bureau of Health Services.

The Department of Health and Human Services issued a Certificate of Confidentiality to protect the privacy of study participants.

Study design

This study used a qualitative approach that borrows heavily from theoretical and methodological traditions of ethnography. Ethnography is a holistic approach to studying human behavior premised on the idea that people create meaning through social interaction and that these shared meanings influence how we think and act (Handwerker, 2009). Rigor in ethnographic research is established through the researcher's proximity to the locations where social interaction occurs and framing questions in relation to observed activities (Spradley, 1979; Lofland et al., 2005). Direct observation of the everyday lives of inmates, however, is difficult (Rhodes, 2009; Wacquant, 2002). Researchers who study hidden populations have argued, therefore, that field research methods must necessarily be adapted to permit various levels of engagement with group members (Adler, 1990). In this study, field stations (Goldstein et al., 1990), provided stable, inconspicuous locations in the community where men leaving jail and prison often came to re-establish HIV care. The researcher adopted an overt role in these settings and made clear his research intentions. By spending time at these field stations, the researcher was able to mingle casually with potential participants, share information about the study, and gradually gain their trust and acceptance before beginning to interview participants.

Interviews and data analysis

The researcher conducted in-depth, face-to-face interviews with 42 participants over a sixmonth period. All interviews were conducted in private rooms in the field stations where participants received their usual care. By interviewing participants at community sites soon after release from jail/prison, the researcher avoided potential distortions wrought by the coercive, stressful environment of prisons while preserving as much as possible the ease of recall that is essential for reliable, descriptive reporting. The researcher used a semi-structured interview guide that was developed from prior fieldwork, a review of the existing literature, and through collaboration with an expert informant with extensive knowledge of the target populations. Interview questions focussed on diagnosis and disclosure, access to HIV care, and adherence to ART in jail/prison. Open-ended questions were included to elicit participant's perceptions about the desirability of ART in jails/prisons and factors that interfered with their willingness or ability to adhere to ART while in custody. Following Spradley (1979), the researcher attempted to build rapport quickly during interviews by conveying a supportive, non-judgmental attitude toward sensitive topics and adjusted lines of inquiry to pursue concerns expressed by participants.

Each participant completed at least one face-to-face, voice-recorded interview. After each interview, the researcher summarized important events, topics, and themes that emerged from the interview. All interviews were transcribed and coded by the researcher using a descriptive approach (Miles and Huberman, 1994). The researcher conducted an investigational analysis of sample characteristics, topics, and themes using the first 30 interviews. Based on this initial round of coding, the researcher sampled and interviewed an additional 12 subjects to achieve maximum variation and reach data saturation. The researcher then conducted follow-up interviews, some by phone, with 19 participants who did not completely address one or more topics covered by the interview guide during the first interview. Results are based on more than 33 hours of tape-recorded interviews, each interview averaging 42 minutes.

Study sample

Persons sampled for this study (n=42) include a cross-section of HIV-infected male and maleto-female transgendered persons leaving Illinois jails and prisons and returning to the Chicago metropolitan area. Persons were eligible to participate if they were 18 years of age or older, self-reported an HIV diagnosis, reported significant CJS involvement in the last three years, spoke English, and were willing to discuss their experiences with the researcher in a voice-recorded interview. In Illinois, as elsewhere in the USA, the overwhelming majority (93.9 percent) of prisoners is classified as male (IDOC, 2010). The researchers therefore chose to restrict this study to persons who reported recent incarceration in a male correctional facility. Participants were recruited through provider referral, word of mouth, and community outreach. The researcher sampled for maximum variation to include participants with diverse CJS and HIV treatment histories. Specifically, the researcher sampled for lifetime frequency and duration of incarceration, frequency of incarceration since diagnosis, types of correctional facilities (e.g. precincts, jails, and low- and high-security prisons), number of years living with HIV, and length of time on ART. To avoid over-representing men currently engaged in community HIV care, the researcher made additional efforts to include recently released men who had not yet demonstrated a willingness or ability to access community-based health services. The researcher interviewed every participant who expressed interest in the study, met inclusion criteria, and gave informed consent. The final sample was well within the recommended range for similar qualitative studies (Sandelowski, 1995). Participant characteristics are shown in Table I.

Table I. Descriptive statistics for recently incarcerated HIV-infected men.

| Measure | n | Mean (SD) | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 42 | 38.5 (10.7) | 19 | 55 |

| Years living with HIV | 10.6 (7.1) | 1 | 27 | |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 27.8 (8.7) | 0 | 47 | |

| Variable | n | % | ||

| Race | ||||

| African American | 37 | 88 | ||

| Caucasian | 2 | 4 | ||

| Hispanic | 1 | 2 | ||

| Biracial | 2 | 4 | ||

| Educationa | ||||

| <HS | 9 | 21 | ||

| HS | 16 | 37 | ||

| Some college | 10 | 24 | ||

| Gender/sexual orientation | ||||

| Straight | 26 | 62 | ||

| Gay | 8 | 19 | ||

| Bisexual | 4 | 10 | ||

| Transgender | 4 | 10 | ||

| AIDS diagnosisa | ||||

| Yes | 16 | 38 | ||

| No | 21 | 50 | ||

| Mode of infection | ||||

| MSM | 15 | 36 | ||

| Heterosexual | 21 | 50 | ||

| Injection drug use | 4 | 10 | ||

| Mother-to-child | 1 | 2 | ||

| Blood transfusion | 1 | 2 | ||

| History of gang affiliationa | ||||

| Yes | 13 | 31 | ||

| No | 23 | 54 | ||

| Diagnosed in a correctional facilityb | ||||

| Yes | 16 | 38 | ||

| No | 25 | 59 | ||

| Initiated antiretroviral therapy (ART) in jail or prisonb | ||||

| Yes | 18 | 43 | ||

| No | 23 | 55 | ||

Note: n=42.

Missing data: education (16 percent), AIDS (11 percent), gang affiliation (14 percent), missed doses (7 percent);

<2 percent data missing

Participants were between the ages of 19 and 55 years (mean=38 years). Most identified as black/African-American reflecting both the ethnicity of Illinois prison populations and the further concentration of African-American parolees into the medically underserved urban neighborhoods like those in which this study was conducted. About one in five participants never finished high school, while nearly a quarter completed at least some college. A third of participants reported a history of gang affiliation. Over 60 percent of participants identified their sexual orientation as “heterosexual” while 40 percent identified as “gay” or “bisexual.” Most participants identified their gender as male, while four identified as male-to-female transgendered or genderqueer. In this paper, participants are referred to as “men” because they were incarcerated in male correctional facilities. The sample included persons from each major transmission risk category. Participants had been living with HIV for ten years on average. The average age at diagnosis was 27.8 years. Participants estimated that they had spent between eight hours to 25 years of their life behind bars. About half of the participants had been incarcerated two to ten years and over a quarter spent more than ten years of their life behind bars. In total, 30 participants were released from jail/prison within the past year (range: two days to 2.5 years).

Results

HIV diagnosis behind bars

More than a third of participants (n=16) was first diagnosed with HIV in a CC. These participants felt they were thrown into an unbearable situation. They said they had stifled the impulse to grieve openly or cope with forceful emotions because they sensed they should do nothing to make themselves more vulnerable than they already were. Participants expressed anguish about being unable to share their pain with or receive comfort from close friends or family. “I hadn't cried when I found out. I wanted to be hugged when I found out. When I told my mom, I told my mom through the glass at (the jail).” Drug withdrawal and uncertainty about the disposition of their legal case often magnified participants' emotional suffering after an initial HIV diagnosis. Participants had dealt with these forceful emotions by withdrawing even further from inmate society or even contemplating suicide. “It just made me very depressed. I shut down. I didn't want to deal with it. At that time in my life I was like, ‘Well, fuck my life is over. I might as well just kill myself. I just wanted to die. If I figure out a way to kill myself, I'm gonna.’” Two participants reported attempting suicide after their diagnosis. “I had talked about killing myself. I remember I had went down to (prison) and I was locked up in segregation. I had tried to hang myself. If my cellie hadn't been there at the time I had tried to do it, it would have been over for me.” The perceived need to remain silent about their diagnosis and the inadequacy of posttest counseling had, according to these participants, directly jeopardized their health.

Participants diagnosed in a CC typically had spent the most time behind bars. Particularly for self-identified “straight” men, incarceration marked a turning point during which a global assessment of their life circumstances and shocking news about the health of their previous sexual partners led them to reconsider their HIV risk. “My ex-wife was coming to see me in the jail and I had noticed a knot on her neck. I asked her what the knot was. She went and got tested and told me that it was HIV. That made me go and get tested.” Another participant discussed the event that led to him to get tested. “The last time I was in (prison) I called home and my mom told me the girl I was seeing died. And I'm like, ‘Died?’ And she says, ‘Yeah. She had AIDS.’”

Men diagnosed in a CC said they had rarely participated in community HIV testing. Some said they had never been offered an HIV test before becoming incarcerated. Key institutional features including coercion and boredom led them to participate in HIV testing. “They tested me. I don't know if it was for HIV. It might have been. They get all the inmates to line up. ‘This is where you got to go. This is what you got to do today.’” Explaining why he chose to accept an HIV test in prison, a participant explained, “I was bored. And I wasn't getting no movement. So I'm gonna ask for an HIV test to get some movement.” Another said, “We was on lockdown. I was fixin' to get out of my cell.” Although incarceration had given them important new knowledge about their health status, it had not given them resources to live with that knowledge and consequently very few felt that it had prepared them to reenter society as a person living with HIV.

The choice to disclose

When faced with a protracted period of involuntary detention, persons living with HIV must decide whether to disclose or conceal their HIV diagnosis. Participants generally recognized that disclosure was a necessary first step to access ART. They disagreed, however, about the optimal circumstances for sharing that information. Some participants opted to declare their HIV health needs during intake while others waited to disclose until being transferred to a medical unit within the CC. Some men rejected the opportunity to disclose altogether, choosing instead to conceal their diagnosis from custodial staff and health service providers.

About half the men in the sample (n=20) disclosed their HIV status at intake. (Four participants were not included in this portion of the analysis because they had not been rearrested since being diagnosed with HIV.) Accessing ART was the main motivation for participants who disclosed. “I wanted my meds and I couldn't get them without letting them know.” Participants who were not taking ART prior to arrest were the least likely to disclose their HIV status at intake. Participants who disclosed said they had been able to share this information with a nurse, physician, phlebotomist, or correctional officer (CO) without compromising their confidentiality. “If you go in there and tell ‘em you have HIV, they keep it under the table, the staff. And they provide your medicine.” Another participant explained, “I told the doctor I'm HIV positive. So it's not like I went in there to hide my condition.” Nearly half of participants said that all they had to do to receive ART was disclose their HIV status.

Men who disclosed often felt, however, that staff viewed their disclosure as a bid for special consideration. Some participants said that they had to convince skeptical CO's that they were in fact HIV positive. “They wanted me to see a doctor in order to be given the medication because quote, unquote, so many people come in saying they have a medical condition of HIV or AIDS when they really don't, which they assume will help them get on disability. So I gave them the information to the (community) clinic I was actually going to.” Men agreed that remembering the names of the medications they were taking had helped them avoid delays in prescribing. “All you got to do is remember the medicine that you take. And I always try to remember. I always keep a paper in my pocket.”

Roughly 40 percent of participants said that they had deliberately withheld their diagnosis from health service providers at some point during incarceration. About two-thirds of these men (n=12) were taking ART prior to their most recent arrest and non-disclosure was one of two leading causes of treatment interruption. Some waited days or weeks before sharing their diagnosis with a CO or health service provider. Others chose not to disclose their diagnosis at all. Among men who had initially concealed their diagnosis, nearly half (n=8) said they eventually disclosed their HIV status to a health service provider. Some of these men disclosed only after they were transferred to an infirmary or special housing unit. Some waited to disclose until their case was adjudicated and it became clear that they were going to prison. “I just told ‘em, ‘No’, because I didn't think I would be there that long to be processed and sent to another jail.” Others disclosed indirectly by requesting an HIV test. Some men opened up only after developing rapport with a particular health provider:

And I went in there (jail) and I didn't feel comfortable with the (psychologist) so I didn't say nothing. But I got to know the nurse a little better because she would come down the tier. And then finally I said, “I think I'm HIV positive.” And she said, “Well, why didn't you tell us when you first got here?” ‘Cause I was actually there for almost a month before I told anybody.

Other participants waited to disclose until their health deteriorated. “I got sick about that time. I had lost a lot of weight. My mouth […] even my tonsils turned snow white. I went and looked in the mirror. I was having bad reactions. So I went over to the doctor and that's when I told him about my HIV.” Another participant explained, “I didn't inform them about my health problems or nothing. I was in perfect health until ‘99, until my neck swelled up. I sat in the hospital about a week until the swelling went down. They gave me (ART).” In order to disclose, men said they had to overcome grave denial. “I was ashamed. I didn't want to accept it. I always kept it to myself. But I knew my body was deteriorating. I called the paramedics and told them I was dying. That's when I started to care for myself. I wanted to live.”

Even when participants wanted to disclose their HIV status, violence and procedures for controlling violence, however, frequently interfered with them doing so:

I was denied (medical evaluation) because the inmates started a fight in the bullpen. So the police officers were trying to keep everything under control. But they didn't care about anything else […] about the fact that I had an asthma condition or that I was really trying to speak to one of the physicians there so that I could tell him I was trying to take my (HIV medicine).

Violence contributed indirectly to non-disclosure by making men feel threatened. One participant explained why he did not disclose his HIV status at intake. “You had one CO. A fight broke out. She said, ‘Oh, I don't do fights. I'll just call it in.’ So she called it in on her radio. And then when we go out to the rec yard, you see people fighting. It's kinda rough. So I didn't feel comfortable talking to nobody there.” Violence also conditioned participants to feel that HIV care was a low priority for prison staff. “It (HIV care) didn't come across to me as that urgent. Because in jail people fight all the time. That comes across to them as being more urgent than someone with cold of flu symptoms.”

A few men (n=5) resisted disclosing altogether. These men were usually incarcerated for shorter periods of time but some were incarcerated as long as two years. These participants expressed concerns that they might be segregated if they disclosed. “I don't want to be isolated in no room over here […] with all these people in the infirmary that got HIV or AIDS.” Others kept their HIV status a secret because they feared the wrong kind of attention. “In the county (jail) I was thirty days, and I was trying to be as isolated as possible.” Explaining why some HIV-infected men hide their HIV diagnosis during intake, one participant summarized a sentiment held by many participants:

So many times when people are incarcerated they don't want to divulge that information. They don't want to disclose that information because of the way information travels through that system. Because of the stigma that still lingers over HIV, they don't want to readily disclose that information, especially in that kind of setting – the incarceration setting.

Gay and transgender participants especially felt that having their HIV diagnosis revealed to other inmates represented a kind of social death. “That's how they feel gay is, like you're dead, you're dying.” Widespread discrimination against homosexuals and inmates living with HIV meant that some participants resisted disclosing and refused ART in order to pursue mutual support, protection, and intimacy with other inmates:

When I go in there, I avoid the health issues with them because it's not enough confidentiality. You want to be accepted. You want to have people to associate with when you're in jail. So you tend not to tell anybody, especially if you look healthy. They don't assume anything. That's the way you leave it. You just leave it that way.

The perception of widespread HIV stigma and homophobia also raised concerns for heterosexual men that they would be exposed to abuses reserved for homosexuals if they disclosed their HIV status. Participants attached special importance to their relationships with other inmates because these were viewed as a primary source of protection and a way to reduce anxiety in an inherently hostile and stressful environment:

It means you're on your own. No protection. You just fucked. You get into a fight, you out there by yourself. Nobody to come aid you […] It's not only about losing protection, it's about losing friends and muthafuckas that have been behind you since day one. They won't fuck with you after they find out you got AIDS.

For about a third of participants, gangs provided a source of security as well as social contact and continuity with life outside of prison. The decision to forfeit these protective relationships in order to access HIV care was seen as very risky.

Accessing HIV care

Participants identified numerous institutional barriers to getting medical attention in CCs (see Table II).

Table II. Institutional barriers to continuity of ART.

| Variable |

|---|

| Overcrowding |

| Violence and violence control measures (e.g. strip searches, lockdowns) |

| Physical isolation (solitary confinement) |

| CO apathy or unwillingness |

| Sick call system |

| Fees for health services |

| Mode for administering medication (pill line vs self-administered) |

| Compulsory treatment |

| Prescribing delays |

| Intermittent dosing |

| Out-of-stock medications |

| Confiscation of medication |

| Medication theft |

The most common obstructions were physical isolation, interpersonal violence, actions for controlling violence, CO apathy or unwillingness, and fees for health services. Participants agreed that CO's had significantly mediated their access to health services. Participants described some CO's as helpful, supportive, and caring, and others as inept and abusive. One participant talked about his frustrated attempts to get medical attention after he developed symptoms of meningitis:

I was sick. And I would tell the officer to tell the nurse. See you have to go through the officer to get any kind of medical treatment. Some officers will say, “You faking it. You not sick.” But my cellie, he knew I was sick ‘cause I wasn't eating and I wasn't coming out. I was just constantly in bed. And for them to really get me some medical attention, I literally passed out in the day room.

Minimal interaction with CO's and limited means of communication added to men's sense of vulnerability. “Now at night made me nervous, ‘cause all you got is your intercom button. But see, they can't hear the intercom button on the outside. Your intercom button only goes to the front desk that's outside the pod. If they're in another pod, they won't hear it ‘til they do their round. It makes you nervous when you can't get proper assistance if you need it.” To safeguard access to health services, participants felt they needed to carefully manage relations with CO's. Said one participant, “You got to bug 'em. The doctor told me to bug 'em. But you don't want to take it too far, ’cause They'll beat your ass.” Strategies for getting medical attention included utilizing the CO chain of command, cultivating personal connections with CO's, calling them by name, and being careful not to provoke CO's with repeated requests for care (see Table III).

Table III. Individual strategies for accessing ART after arrest.

| Strategy |

|---|

| Disclose HIV status (immediate vs delayed) |

| Request an HIV test |

| Sign up for sick call |

| Manage relations with CO's |

| Enlist family members |

| Refuse medication (medication strike) |

| Fake mental illness |

| Avoid conflict with other inmates |

| Hide medication from cellmates |

Men believed that CO's were unlikely to respond to HIV as an urgent medical problem and said that disclosing their HIV diagnosis did not automatically qualify them for timely medical attention. Because of this perception, some men felt that they had to threaten legal action, claim a more serious diagnosis, fake mental illness, or refuse HIV medication in order to get medical attention. Participants who had been especially concerned about promptly accessing ARTafter arrest said they had disclosed other medical conditions to get transferred to an infirmary – a key access point for utilizing health services and a place generally perceived as safer, cleaner, and more conducive to disclosure and treatment. One participant explained why he disclosed a potentially life-threatening coagulopathy in order to access the infirmary:

If I had told them I was HIV positive, they would have put me out in population, in a regular prison ward. But they say a blood clot is more serious than HIV. If I get bruised or injured, I might bleed to death. And then it'd be on their hands. The only reason I got medicine was because I was in the infirmary. And by me being in the infirmary, they had to give me my medication. So that's what kept me safe really. Because population in the (jail), you had to fight just about every day or get everything taken away from you. And by me not being in a gang, by me not being in no organization, I would have been getting jumped on, fighting every day. And if I would have been getting into a fight, a major fight, I would have got cut, it would have been hard for me to stop bleeding. That's why they put me in the infirmary. But other than that […] just being HIV positive, they would have put me in population. They really don't care about people with HIV. They say you just another human being. Go out there and do what you need to do.

Other participants said they faked or exaggerated symptoms of mental illness to get more timely HIV care after their attempts to access ART by disclosing their HIV status had failed:

So the fifth day came and I asked for my medication. They said, “Well, you don't have any medication. The doctor hasn't issued it yet.” They said, “We don't have nothing with your name on it.” I said, “Okay, I'm gonna commit suicide.” They said, “Are you sure?” I said, “I'm bipolar, I'm seeing dead people anyway.” I said, “They're telling me to hang myself.” So they started watching me. They took me to the psych ward. They asked me if I was on medication. I said I was on Lithium. So when they took my labs they said, “you're not on Lithium. Why did you say you were on lithium?” I said, “Because I tried to explain it to them in receiving but wasn't nobody listening to me.” So I said, “If I have to play another game to get my medication that is what I'm gonna do. Each time I come into jail and you people don't give me my (HIV) medication, y'all gonna have me on a mental ward until you take my lab work and see what medicine is in my body.”

While CO's may have viewed their claims of mental illness as chicanery, these men were strategically using the means at their disposal in their fight for survival.

Other strategic attempts to get medical attention involved taking calculated health risks. Two participants said they had gone on a medication strike in order to get the care they felt they needed. One participant talked about his decision to refuse ART:

Being in prison, they don't want to change your medication. If you go to ‘em and tell ‘em “Look, I'm having a problem with this medication. All these pills is stressing me out, giving me nausea and diarrhea.” They act like they don't want to change it. You have to go through a lot to get it changed. It got so bad that I just stopped taking my medication. And my t-cell count dropped all the way to 31. And my viral load was up real high. And they started telling me I got to take my medication. And I got to the point, I said, “I can't take my medication.” And they said, “If we change you to [another medication], will you take it?” I said, “Yeah, that's what I want.” And so they said, “Okay, we gonna give you [another medication].” And they changed it. That was the only way they changed it.

Another participant said he refused ART in order to get medical attention:

I wasn't getting medical attention for my assault so I went on a medication strike. And I told them, “I'm not taking no medication. I'm not eating until I get medical attention. And they said, ‘Why?’” And I told them why. And they went and documented it down in my file. Because they was failing to document my complaints. They did not want to document them down.

When men felt their treatment choices and calls for justice were devalued or ignored, they perceived their own ill health as a potential liability for the institution that was charged with caring for them. In some cases, these men believed they could wager their health to achieve the kinds of interactions with health service providers that were likely to lead to the medical attention they felt they needed.

Initiating and adhering to ART

Nearly half of participants (n=18) initiated ART in a CC, and most (n=34) took ART during their last incarceration. Almost all men who requested ART during their last incarceration said they eventually received treatment. Many participants (n=27), however, reported missing doses or sustained treatment interruptions lasting weeks or months due to delayed prescribing, out-of-stock medications, and intermittent dosing. “I think I had to wait a whole month. Because they kept telling me pharmacy didn't get it yet.” Another participant stated, “If they bring you medicine, They'll bring it to you one day, then miss three days, then bring it, then miss some days, and then bring it. They bring it off and on.” Participants said mass punishments also interfered with inmates receiving ART. “Sometimes they had statewide lockdowns when you didn't get your medication sufficient, because they have to bring medicine to you. And you got 2,600 people. And you got some nurses passing out meds. Come on, you know it's gonna be some screw up.”

Disciplinary actions including segregation, medication confiscation, and compulsory treatment figured pointedly in men's descriptions of taking ART in a CC. Extreme physical isolation impinged on participants' readiness to accept ART:

Division 10 is strictly behind doors. So you're only out for three hours a day. And that wasn't what I signed up for. I was getting so depressed that […] that was one reason why I didn't take my medication too. Because I was behind that door. I was like, “Man, forget it. I ain't fixin' to take the medicine. I ain't fixin' to do nothing.

Some however, felt that being segregated from other inmates had given them more privacy to take ART. A few men reported missing doses for several days because a CO had confiscated ART prescribed by a CC physician. These men felt CO's had showed deliberate indifference to their medical needs by ignoring crucial information that could have prevented treatment interruption. “The federal marshals brought me to the jail. I was like, ‘Those are my meds, man. I gotta have ‘em. Y'all see my file.’ There go my paperwork, my log. I had my own medical file, the one I sent them. I always carry it with me. They was like, ‘We don't care. You got to see the doctor.’” A few participants felt that they had no choice about taking ART, saying that they feared additional sanctions if they failed to show up when medications were dispensed. “If you got med's and the nurse come and you're not in the med line you get an 8-hour lockdown. You have to stay in your cell for 8 hours, which is actually one day.” Others saw compulsory treatment as a reasonable way for the institution to ensure access. “And you can actually go to segregation for not taking it (ART). That was like a good thing, I guess.” For that reason, these men came to see ART as part of the coercive apparatus of a CC.

participants' beliefs about the quality and availability of health services in CCs factored significantly into their decisions to take ART. Some voiced a concern that initiating ART would expose them to the hazards of substandard care. “They really don't care what type of medicine they give you. They don't care. If they gave you the wrong medicine and you died in your cell, they don't care.” Other participants valued the opportunity for closer contact with health service providers and saw initiating ART as a way to improve access to health services. “I said, ‘I'll start treatment’, ‘cause in (jail) it was hard to see a nurse. So if a nurse bring your medication, I could always tell her my medical problems when she come up.”

Men expressed a fundamental concern that initiating ART could make them more vulnerable in an environment they saw as inherently hostile. Some were apprehensive about starting ART because they believed that HIV medicine could reduce their mental alertness, making them less vigilant and more open to exploitation:

you're in there with murderers, killers, and rapists. There's so many people in different frames of mind. And I was like, I don't know if I want to be on this medication. Does it make you drowsy or sleepy? Or where you're not focused on your environment? And was skeptical what it does. Does it make you sleep? I really didn't want to sleep. I mean, you're around people who don't care about hurting you. They might come in your cell and do something to you while you're asleep because your door is open.

Participants believed initiating ART could result in loss of confidentiality. They said that in many CCs ARTwas dispensed with little regard for privacy. “Everybody knew what medicine (the nurse) was giving you anyway. There was no privacy to that at all. She was doing it right in front of everybody.” Participants said special medication packaging made ARTan open secret. “People know you have HIV because they give you medicine in a brown paper bag.” Men sometimes felt dehumanized by the way that ART was distributed. “Got my meds like you would feed a dog. You know? Just, ‘Here!’ ‘Here they are!’ No interaction with the doctor about the medication. None of that.” Another participant stated, “I saw them take the meds and just throw them. See when you at the county jail, they figure you ain't even human. They feel like you ain't a man or nothing, so they don't treat you that way.” Participants worried that taking ART in a CC might result not only in a loss of privacy but might expose them to further harassment by CO's. One transgendered participant describes her release from prison. “Officers was standing around me, and they pick up my meds. ‘What's this for? Is this for HIV? If this is for HIV, we're gonna have to hold you here and see if you had sex with anybody else.’” The perceived loss of dignity involved in taking ART was a major reason that some men did not disclose their HIV status or stopped taking ART.

Evading cellmates or “cellies” and hiding medication from them were primary concerns for men who were taking ART in a CC. “The medication was kind of hard for me to take because I was sharing a cell no bigger than this room with someone. You constantly have someone in your business trying to figure out what it is you're taking and why you're taking it.” At least one participant stopped taking ARTaltogether for fear that his cellie would find out he was HIV positive:

I ended up getting placed in a cell with this one person. I got scared. I didn't want to take my medicine. I came off my [medication] for almost two and half months. I was shit-scared as to being off the medicine. I was shit-scared of being in a cell with this person. I was just scared of being back in population.

To protect their privacy while taking ART, participants said they concealed medication from cellies and tried to mask medication side effects:

I would take my pillbox and put my doses in this little envelope. I would take the envelope and stick it under my pillow so that when I would wake up in the middle of the night, knowing he was asleep […] I would take it right out, pop my pills, drink my water and hide the rest of ‘em. But that's what I mean by “shell game”. More or less just hiding them […] hiding what was going on with me.

Participants said they hid ART also because they believed other inmates might steal their medication in order to sell it, “They fucking be trying to sell your medication,” or use it recreationally. “I've seen a guy. He was on meds. His cellie went into the cell and wanted to get high. He took the man's last dose. They'll steal any medicine. They'll take the medicine and mix it with hooch just to make the hooch stronger. That's how they roll.” Men found it hard to conceal the large quantities of medicine they were taking in their cell. One participant said he sought out a work detail within the prison that gave him more discreet access to the prison dispensary:

I could pick up my med's whenever I wanted. I didn't have to stand in line to do it. So basically I had more privacy than other people. I would sneak them back to the dorm when they (other inmates) were out in the yard. Then I'd go put it in my box. When I was ready to take it, I would take it out like an hour before when I seen it was a good advantage. And I kept it all together instead of having to go through each jar. That way nobody heard me rattling the things, wondering why I'm taking so much med's.

Adaptations giving some men more discrete access to ART ultimately evolved in response to common perceptions about the accepted social rules in CCs.

Discussion

Understanding HIV care delivery from the inmates' point of view

In this study, participants' decisions to disclose their HIV status or initiate ART while incarcerated were strongly influenced by social conditions not specifically related to their perceptions of health services but tied more to their perceptions of violence, safety, and privacy (see Table IV).

Table IV. Social conditions that influence readiness to accept ART in jail/prison.

| Condition |

|---|

| Interpersonal violence |

| Lack of safety |

| Social stigma |

| Threats to privacy |

| Perceived inadequacy of jail/prison health services |

| Desire for social support from other inmates |

| Desire to avoid additional control and punishment |

Participants perceived violence as endemic to many CCs. “I didn't think I would make it back home. They started hiding weapons all over the place. People getting stabbed…getting cut up. This is what we are seeing and hearing every day.” Mere survival, in this context, was viewed as an accomplishment. Physical and sexual violence were meted out through a system of institutionalized antipathy toward homosexuals and inmates living with HIV. “When you're in jail and you're positive, you're pretty much treated as a second class citizen.” Because they viewed violence and stigma as relentless threats, men tried to shield themselves by nurturing amicable and mutually fulfilling relationships with other inmates:

In prison everybody's so-called “hard-core”. But there's always someone looking for someone to keep ‘em so they can do time together. Not as in a relationship way but in an understanding way. Because you get close to somebody. You guys share food together. You find somebody you can relate to.

Perceptions of violence, fear of stigma and alienation, and wanting to achieve protection, mutual support and intimacy from other inmates often superseded concerns about accessing HIV care or adhering to ART and therefore, interfered with the detection and treatment of HIV. The desire for mutually supportive relationships was so strong that some participants resisted disclosing and refused ART in order to pursue emotional and sexual intimacy with other inmates.

Jails and prisons were integral for entering into HIV care for participants in this sample. More than a third were diagnosed in a CC and almost half started ART for the first time in jail or prison. Health services in CCs were seen paradoxically by many men as more accessible than health services in the community, “It's more complicated out here (in the community) than it is in there (in prison)” and impressions of health service providers in jails/prisons were often very favorable. Those who were diagnosed in the community but had delayed entry into care believed that incarceration had catalyzed their engagement with HIV care. “I believe too that me going to jail was a way to get introduced back into being healthy and checking up on myself.” These findings provide further evidence that for many CJS involved men, CCs offer the only starting place for HIV care (Braithwaite and Arriola, 2003).

This study suggests that receiving an HIV diagnosis in jail/prison is an especially stressful event that intensifies other constant stressors including concerns about personal safety and the adequacy of health services. This finding is consistent with other research on perceptions of quality of life among HIV-infected prisoners showing that detainees experience HIV-related illness during incarceration as a “double burden” (Esposito, 2012), that contributes to a sense of isolation and fatalism. Post-test counseling and HIV peer support were felt to be largely unavailable to participants in this study and could provide an important alternative to the prevailing culture of shame and secrecy. Interventions that focus on the social and emotional needs of men who are leaving jail/prison are likely to strengthen men's commitment to HIV treatment and perhaps contribute to reducing recidivism. Interventions designed and led by peer health educators could weaken the hold that certain meanings exercise on men's choices and strengthen the affirmative impetus conveyed by others. Participants who did utilize these services say that they benefitted. Failing to deliver the right mental health interventions at the right time could create long-term consequences including ineffective coping, HIV denial, and future risk-taking (Scheyett et al., 2010).

For persons already aware of their status, accessing HIV care during incarceration is a conscious choice. Failure to disclose was the second leading cause of treatment interruptions caused by incarceration for men in this sample. This is perhaps the first study to examine qualitatively the reasons why some HIV-infected men conceal their HIV status when they become incarcerated. An inmate who conceals his HIV diagnosis or refuses ART is portrayed anecdotally as passive, noncompliant, attempting to manipulate the system for short-term gain, or worse a person with intractable, criminal character defects. In contrast, this study shows that some men are making calculated and rational choices about their health and attempting to minimize their risk exposure in an environment they perceive as potentially very dangerous. Inmates emerge as active and discerning consumers of health services, balancing their HIV treatment needs with safety and privacy concerns while maximizing opportunities for therapeutic contact with health service providers. The seemingly counter-productive strategies that men use to overcome perceived obstacles to HIV care, including exaggeration and deception, suggest that there is a suboptimal match between men's alleged health needs and the way these institutions as a whole are set up to fulfill these needs. Establishing trust with a health service provider was a necessary step for some men before they felt comfortable disclosing their HIV status or seeking HIV care. This suggests the need for more routine, confidential contact with health service providers, thereby creating opportunities to establish and build rapport. Others disclosed only after their health sharply declined, demonstrating further the need for routine HIV testing in jails/prisons.

Participants in this study said that intense physical isolation, interpersonal violence, lack of privacy, and inefficient medical care were barriers to HIV care in a CC. Some inmates believed HIV care was given low priority and felt that disclosing their HIV status might not necessarily improve their access to HIV care. Violence interfered with inmates' use of health services, especially for men who perceived themselves to be socially disadvantaged. Although men agreed that gang membership carried an additional set of risks and risk protections, the study found no evidence that gang membership interferes with access or adherence to ART. In a few instances, gang membership even seemed to provide a measure of security and privacy for self-administered ART.

Prisoners' acceptance of and adherence to ART sometimes depend on their beliefs about HIV medications and their willingness to continue ART when they experience side effects (Altice et al., 2001). This study adds new complexity to these predictors of adherence. Participants felt that certain medication side effects could render them more vulnerable to attack or compromise their social status. This study also identified novel causes of ART non-adherence that stemmed from inmate struggles for autonomy including medication confiscation and medication strikes. This study shows that inmates are weighing the potential risks and benefits of becoming a patient when they make decisions about whether or not to request ART. Depending on guards for ART creates another potential layer of social control. Being a patient inside jail or prison, however, may confer advantages like access to infirmaries where there is greater safety and access to life-saving medications is more reliable.

Participants in this study reported many of the same institutional barriers to adherence reported in similar studies (Pontali, 2005) including delayed prescribing, medications out-of-stock, and intermittent dosing during lockdowns. Fewer than half of participants estimated their adherence to be >90 percent during their most recent incarceration. This finding is consistent with other research showing that adherence to ART (both directly observed- and self-administered therapy) is frequently suboptimal and many prisoners have adherence rates lower than those required to provide lasting viral suppression (Wohl et al., 2003). Roberson et al., (2009) showed that incarcerated HIV-infected women saw advantages to directly observed therapy (DOT) but said DOT raised concerns about confidentiality and stigma, while self-administered therapy (SAT) provided a measure of self-determination. Participants in this study expressed preference for SAT and reported loss of confidentiality with DOT.

Being in HIV care is often associated with reductions in sexual risk behaviors among HIVinfected adults (Metsch et al., 2008). This is among the many reasons why we should provide HIV care to incarcerated men in ways that reward their participation and create opportunities for them to confidently manage their illness. In particular, we should make every reasonable effort to ensure prompt access, adequate privacy, and personalized medication administration for inmates who ask for ART and are good candidates for ART. When ART or medical care is delayed or withheld, some men will perceive this as an additional control, meaning that they may use health services in ways that are inefficient or even risk their health because to them these seem like sensible alternatives.

Conclusion

Steps to reduce violence and promote safety in jails/prisons are absolutely necessary to expand access to ART in these settings. This study showed that violence, stigma, and the pursuit of social support frequently interfere with access and adherence to ART. Men said that wanting to access ART was a strong motivator for them to disclose their HIV status after arrest. Those who judged the immediate setting as unsafe or lacking adequate privacy measures, however, sometimes withheld their diagnosis or refused ART because they believed that taking ART would raise their risk of being subjected to violence. These participants tried to protect themselves against perceived dangers by hiding their diagnosis and blending in as much as possible. Substantial improvements in ART access and adherence are likely to follow organizational changes that make incarcerated people feel safer, facilitate HIV status disclosure, and better protect the confidentiality of inmates receiving ART. Each part of a CC should be configured to make inmates feel safe, to facilitate disclosure, and to maximize opportunities for treatment. For inmates to choose ART, healthy choices also should appear to be reasonable choices.

This study points to a genuine opportunity for intervention. Given that prisoners respond rationally to the risks they encounter while incarcerated, and that we have only incomplete and anecdotal knowledge of the behaviors of incarcerated HIV positive men, understanding prisoners' perceptions opens a door to designing environments that take advantage of the coherence and potential predictability of their behaviors. The systematic study of what have so far appeared to be shortsighted or self-defeating behaviors may reveal patterns that will enable us to create more effective interventions that will ultimately help contain the spread of HIV both inside and outside the criminal justice system.

Acknowledgments

This publication resulted from research supported in part by the Chicago Developmental Center for AIDS Research, an NIH funded program (P30 AI 082151) that is supported by the following NIH Institutes and Centers: NIAID, NCI, NIMH, NIDA, NICHD, NHLBI, NCCAM. Additional support was provided through a research award from Sigma Theta Tau Nursing Honor Society.

Footnotes

About the author: At the time of the study, Dr Gabriel J. Culbert was a PhD Candidate at the College of Nursing, University of Illinois at Chicago. He is currently a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Yale University School of Medicine. Dr Gabriel J. Culbert can be contacted at: gabriel.culbert@gmail.com

References

- Adler P. Ethnographic research on hidden populations: penetrating the drug world. In: Lambert EY, editor. The Collection and Interpretation of Data from Hidden Populations. NIDA Research Monograph 98 DHHS; Rockville, MD: 1990. pp. 96–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altice F, Mostashari F, Friedland GH. Trust and the acceptance of and adherence to antiretorviral therapy. JAIDS. 2001;28(No. 1):47–58. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200109010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckwith CG, Zaller ND, Fu JJ, Montague BT, Rich JD. Opportunities to diagnose, treat, and prevent HIV in the criminal justice system. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(No. S1):S49–S55. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f9c0f7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite RL, Arriola KRJ. Male prisoners and HIV prevention: a call for action ignored. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:759–63. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chicago Department of Public Health. STI/HIV Surveillance Report. Division of STI/HIV; Chicago, IL: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, Hakim JG, Kumwenda J, Grinsztejn B, Pilotto JHS, Godbole SV, Mehendale S, Chariyalertsak S, Santos BR, Mayer KH, Hoffman IF, Eshleman SH, Piwowar-Manning E, Wang L, Makhema J, Mills LA, de Bruyn G, Sanne I, Eron J, Gallant J, Havlir D, Swindells S, Ribaudo H, Elharrar V, Burns D, Taha TE, Nielsen-Saines K, Celentano D, Essex M, Fleming TR. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. The N Engl J Med. 2011;365(No. 6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condon L, Hek G, Harris F, Powell J, Kemple T, Price S. User's views of prison health services: a qualitative study. J Adv Nurs. 2007;58(No. 3):216–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culbert G. Understanding the health needs of incarcerated men living with HIV/AIDS: a primary health care approach. Journal of the American Psych Nurses Assoc. 2011;17(No. 2):158–70. doi: 10.1177/1078390311401617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Viggiani N. Unhealthy prisons: exploring structural determinants of prison health. Sociol Health Illn. 2007;29(No. 1):115–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.00474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffus WA, Youmans E, Stephens T, Gibson JJ, Albrecht H, Potter RH. Missed opportunities for early HIV diagnosis in correctional facilities. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(No. 12):1025–32. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito M. ‘Double burden’: a qualitative study of HIV positive prisoners in Italy. Int J Prison Health. 2012;8(No. 1):35–44. doi: 10.1108/17449201211268273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanigan T, Zaller N, Beckwith CG, Bazerman LB, Rana A, Gardner A, Wohl D, Altice FL. Testing for HIV, sexually transmitted infections, and viral hepatitis in jails: still a missed opportunity for public health and HIV prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(No. S1):S78–S83. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fbc94f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein PJ, Spuny BJ, Miller T, Bellucci P. Ethnographic field stations. In: Lambert EY, editor. The Collection and Interpretation of Data from Hidden Populations. NIDA Research Monograph 98 DHHS; Rockville, MD: 1990. pp. 80–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handwerker EP. The Origin of Cultures: How Individual Choices Make Cultures Change. Left Coast Press; Walnut Creek, CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Illinois Department of Corrections (IDOC) [accessed August 11, 2013];Annual report FY2010 Springfield, IL. 2010 available at: www2.illinois.gov/idoc/reportsandstatistics/Pages/AnnualReports.aspx.

- Kacanek D, Eldridge GD, Nealey-Moore J, MacGowan RJ, Binson D, Flanigan TP, Fitzgerald CC, Sosman JM the Project Start Study Group. Young incarcerated men's perceptions of and experiences with HIV testing. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(No. 7):1209–15. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.085886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVigne NG, Mamalian CA. A Portrait of Prisoner Reentry in Illinois. The Urban Institute Justice Policy Center; Washington, DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lofland J, Snow DA, Anderson L, Lofland LH. Analyzing Social Settings: A Guide to Qualitative Observation and Analysis. 4th. Wadsworth Publishing; Florence, KY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Metsch LR, Pereyra M, Messinger S, Strathdee SA, Anderson-Mahoney P, Rudy E, Marks G, Gardner L Antiretroviral Treatment and Access Study (ARTAS) Study Group. HIV transmission risk behaviors among HIV-infected persons who are successfully linked to care. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(No. 4):577–84. doi: 10.1086/590153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis. 2nd. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- NIH. Unprecedented effort to seek, test, and treat inmates with HIV. [accessed August 11, 2013];NIH News. 2010 available at: www.nih.gov/news/health/sep2010/nida-23.htm.

- Pontali E. Antiretroviral treatment in correctional facilities. HIV Clin Trials. 2005;6(No. 1):25–37. doi: 10.1310/GTQM-QRM1-FDW8-Y2FT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rold WJ. Thirty years after Estelle v. Gamble: a legal retrospective. J Correct Health Care. 2008;14(No. 1):11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes LA. Ethnography in sites of total confinement. Anthropology News. 2009;50(No. 1):6. [Google Scholar]

- Roberson DW, White BL, Fogel CI. Factors influencing adherence to antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected female inmates. Journal of the Assoc of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2009;20(No. 1):50–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagnelli E, Starnini G, Sagnelli C, Monarca R, Zumbo G, Pontali E, Gabbuti A, Carbonara S, Iardino R, Armignacco O, Babudieri S Simspe Group. Blood born viral infections, sexually transmitted diseases and latent tuberculosis in Italian prisons: a preliminary report of a large multicenter study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16(No. 15):2142–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Sample size in qualitative research. Res Nurs Health. 1995;18(No. 2):179–83. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheyett A, Parker S, Golin C, White B, Davis CP, Wohl D. HIV-infected prison inmates: depression and implications for release back to communities. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(No. 2):300–7. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9443-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small W, Wood E, Betteridge G, Montaner J, Kerr T. The impact of incarceration upon adherence to HIV treatment among HIV-positive injection drug users: a qualitative study. AIDS Care. 2009;21(No. 6):708–14. doi: 10.1080/09540120802511869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spaulding AC, Seals RM, Page MJ, Brzozowski AK, Rhodes W, Hammett TM. HIV/AIDS among inmates and releasees from US correctional facilities, 2006: declining share of epidemic but persistent public health opportunity. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(No. 11):1–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradley JP. The Ethnographic Interview. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Publishers Inc.; Philadelphia, PA: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Springer SA, Altice FL. Managing HIV/AIDS in correctional settings. Currr HIV AIDS Rep. 2005;2(No. 4):165–70. doi: 10.1007/s11904-005-0011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer SA, Pesanti E, Hodges J, Macura T, Doros G, Altice FL. Effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected prisoners: reincarceration and the lack of sustained benefit after release into the community. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(No. 12):1754–60. doi: 10.1086/421392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer SA, Friedland GH, Doros G, Pesanti E, Altice FL. Antiretroviral treatment regimen outcomes among HIV-infected prisoners. HIV Clin Trials. 2007;8(No. 4):205–12. doi: 10.1310/hct0804-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacquant L. The curious eclipse of prison ethnography in the age of mass incarceration. Ethnography. 2002;3(No. 4):371–97. [Google Scholar]

- Wohl DA, Stephenson BL, Golin CE, Kiziah CN, Rosen D, Ngo B, Liu H, Kaplan AH. Adherence to directly observed antiretroviral therapy among human immunodeficiency virus-infected prison inmates. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(No. 12):1572–6. doi: 10.1086/375076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]