Abstract

Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) are persistent and bioaccumulative anthropogenic and natural chemicals that are broadly distributed in the marine environment. PBDEs are potentially toxic due to inhibition of various mammalian signaling pathways and enzymatic reactions. PBDE isoforms vary in toxicity in accordance with structural differences, primarily in the number and pattern of hydroxyl moieties afforded upon a conserved core structure. Over four decades of isolation and discovery-based efforts have established an impressive repertoire of natural PBDEs. Based on our recent reports describing the bacterial biosyntheses of PBDEs, we predicted the presence of additional classes of PBDEs to those previously identified from marine sources. Using mass spectrometry and NMR spectroscopy, we now establish the existence of new structural classes of PBDEs in marine sponges. Our findings expand the chemical space explored by naturally produced PBDEs, which may inform future environmental toxicology studies. Furthermore, we provide evidence for iodinated PBDEs and direct attention toward the contribution of promiscuous halogenating enzymes in further expanding the diversity of these polyhalogenated marine natural products.

INTRODUCTION

Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs, Figure 1a) represent a ubiquitous group of marine natural products. In addition to structurally similar anthropogenic flame retardant chemicals, naturally produced marine PBDEs have attracted intense scrutiny due to their toxic effects on mammalian hormone signaling pathways and the inhibition of essential enzymatic functions.1–5 PBDEs have been isolated from marine Eukarya,6–12 where they can constitute up to 10% of the total mass of marine invertebrates such as sponges.13 Together with structurally related polybrominated biphenyls, dibenzofurans and dibenzo-p-dioxins, production of PBDEs at lower trophic levels in the marine biota likely introduces these persistent molecules into the marine food chain,14–16 from where they enter our food supply,17,18 potentially leading to deleterious health effects in humans.

Figure 1.

Diversity of aryl biradical coupling outcomes. (a) Basic structure of PBDEs with nomenclature that is used in this report. Intermediates following radical initiation and rearrangement for (b) bromophenols and (c) bromocatechols. Bromine atoms are omitted in the intermediate structures for clarity. Possible regioisomeric outcomes for (d,e) bromophenol homocoupling, (f–h) bromophenol-bromocatechol heterocoupling, and (i,j) bromocatechol homocoupling. Note that methylation of phenoxyls further increases the structural diversity of marine PBDEs, but has been omitted here for clarity.

We recently described the genetic and chemical foundation for the biosyntheses of hydroxylated, dihydroxylated and trihydroxylated PBDEs (OH-BDEs, di-OH-BDEs, and tri-OH-BDEs, respectively) by marine bacteria.19,20 Consistent with the underlying biochemical logic for the oxidative coupling of aryl rings,21 our studies revealed that naturally produced OH-BDEs and di-OH-BDEs are assembled via the biradical homo- and heterocoupling of bromophenol and bromocatechol monomers mediated by cytochrome P450 enzymes. Recently, additional biotic22 and abiotic23 radical coupling processes have been reported for OH-BDE syntheses. Biradical coupling reactions often lead to the formation of multiple regioisomeric products due to the rearrangement of phenoxy radicals followed by coupling between different intermediates as shown in Figure 1b–j. Regioisomeric products were indeed observed during the course of our studies via in vitro enzymatic reactions,19,20 and can also be rationalized on the basis of structures of PBDEs that have been isolated from marine sources.6–13

It is becoming increasingly apparent that different PBDE regioisomers may contribute toward different mechanisms of toxicity.2,24,25 Prime illustrative examples in this regard are the para-hydroxylated-PBDEs (p-OH-BDEs, Figure 1e), distinguished from ortho-hydroxylated-PBDEs (o-OH-BDEs, Figure 1d). p-OH-BDEs, unlike o-OH-BDEs, are potent inhibitors of thyroid hormone signaling pathways as they structurally mimic the polyiodinated thyroid hormones.26,27 Dictated by biosynthetic logic, p-OH-BDEs and o-OH-BDEs should coexist in the marine metabolome. However, there exists only a solitary report describing the isolation of a p-OH-BDE from marine algae,10 whereas p-OH-BDEs have not been detected in the Indo-Pacific Dysidea sp. sponges that are otherwise prolific sources of o-OH-BDEs.6,7,9,11–13 Dichotomy in the detection of different classes of PBDEs is even starker for di-OH-BDEs. Dysidea-derived di-OH-BDEs are largely restricted to isomers with hydroxyls at the 6- and 2′-positions,9,24 (Figure 1f) with a solitary instance for both phenoxyls being localized on the same ring at the 5- and 6-positions (Figure 1g).28 Isomeric species corresponding to Figure 1h have yet to be described in the literature. Further, trihydroxylated PBDEs (tri-OH-BDEs) generated by the bromocatechol-bromocatechol coupling20 (Figure 1i–j) have completely evaded discovery.

In light of our biomimetic in vitro investigations,19,20 we anticipated a greater chemical space to be occupied by naturally produced PBDEs than what has been described in the literature to date, further enhancing the toxicity potential for these persistent and bioaccumulative molecules. We reasoned that the elusive structural classes of PBDEs might be present in amounts too low to be captured by traditional fractionation and isolation based natural product discovery workflows. Hence, analytical techniques with lesser detection limits for the analyses of marine invertebrate extracts were sought. Due to the combined advantage of structural information that can be gleaned via fragmentation of molecules,29 we chose to employ tandem mass spectrometry in combination with high pressure liquid chromatography (LC-MS/MS) for analysis of extracts of Indo-Pacific sponges Dysidea granulosa and Lamellodysidea herbacea (Figure 2). While identifying novel structural classes of PBDEs present in Dysidea sponges, our findings also lead to the proposal for structural diversification afforded upon PBDEs by substrate promiscuous halogenases present within the sponge proteome.

Figure 2.

Dysidea sp. as sources of PBDEs. UV-absorption profile for HPLC separation of extracts from (a) D. granulosa and (b) L. herbacea monitored at 214 nm. Insets show the morphology of the sponges used in this study. Also shown are chemical structures of the PBDEs 1–3, bromophenol 4, bromocatechol 5 and two possible structures (6–7) for the methoxylated bromocatechol detected in Dysidea sp. sponges.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sponges were collected by scuba and snorkel at various sites within the US Territory of Guam (Supporting Information (SI) Figure 1), and frozen at −20°C. Methods for preparation of MeOH extracts of the sponges, and nontargeted LC-MS/MS mining of these extracts is provided in the SI. No halogenated solvents were used for extractions in this study.

For preparative scale isolation of molecules, up to 20 g of sponges were lyophilized and extracted twice with MeOH. Organic layers were pooled and concentrated in vacuo. The extracts were analyzed by LC-MS/MS and crude fractionation was performed using preparative HPLC to isolate impure, but enriched fractions of target PBDEs. Further MS-guided purification was performed on semipreparative HPLC to yield pure PBDEs for structure elucidation via NMR. NMR experiments were performed using 1.7 mm spinner tubes containing samples dissolved in MeOH-d4 using a Bruker 600 MHz spectrometer.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Based on comparison of 1H NMR spectra of purified individual PBDEs to previous reports in the literature, the two major metabolites from D. granulosa were identified as 1 and 26,7 (Figure 2 and SI Figures 2–3), whereas 3 was identified as the major constituent of extracts derived from L. herbacea. Due to the presence of a methoxy group that can cause unpredictable shifts in the 1H and 13C spectra of PBDEs,6 complete 2D-NMR characterization of 3 was performed (SI Figures 4–9). Note that 1–2 and 3 correspond to the structure types shown in Figure 1d and Figure 1f, respectively. Additionally, using MS, we observed the bromophenol and bromocatechol monomers 4 and 5 in D. granulosa, along with a novel methoxylated bromocatechol in L. herbacea (SI Figure 10), the structure of which could not be resolved between 6 and 7 by MS.

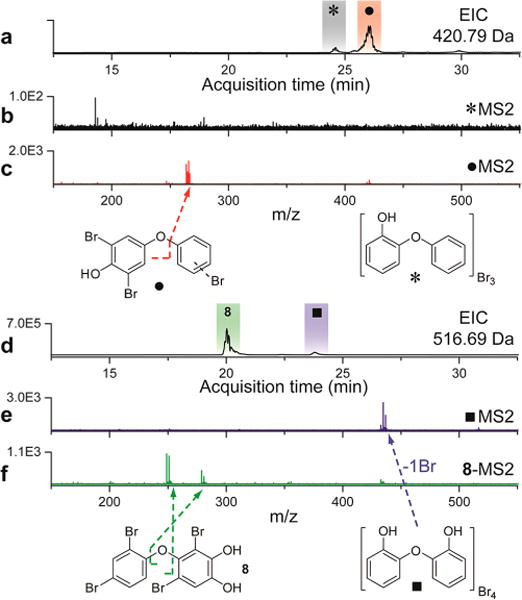

Having thus determined the identity of the major metabolites along with the presence of both bromophenol and bromocatechol monomeric building blocks, we next focused on investigating the relatively less abundant PBDEs present in the extracts using LC-MS/MS. An extracted ion chromatogram (EIC) for 420.79 Da, which corresponds to the dominant [M–H]1− ion for the molecular formula C12H7Br3O2, revealed two isomeric tribrominated OH-BDEs present in the extract of D. granulosa. While tribrominated OH-BDEs were unambiguously detected by MS, their relative lack of abundance in the sponge extracts made a UV-based detection and subsequent isolation for structure elucidation by NMR untenable. However, the two isomers demonstrated distinct MS/MS fragmentation patterns that led to structural assignments. One of the isomers (denoted by * in Figure 3) demonstrated no discernible MS2 product ions (Figure 3b), which is characteristic for o-OH-BDEs.19,30 The other isomer (denoted by • in Figure 3), demonstrated a major MS2 product ion corresponding to a dibromohydroquinone moiety (Figure 3c). Detection of brominated hydroquinone MS2 product ions is a distinct feature of p-OH-BDEs (Figure 3c).19,30 Hence, these LC-MS/MS results reveal for the first time that o-OH-BDEs and p-OH-BDEs do indeed coexist within Dysidea metabolomes. While the positioning of the bromine atoms cannot be discerned by MS/MS alone, a rational reduction in possibilities for • can be made, primarily for Ring A, where the two bromine atoms are positioned ortho- to the phenoxyl, consistent with the structures of other p-OH-BDEs that were enzymatically synthesized in vitro.19

Figure 3.

MS/MS based differentiation between structural classes of PBDEs. (a) EIC for [M–H]1− 420.79 Da identifies two tribrominated OH-BDEs, of which the isomer denoted by * (b) does not display distinctive MS2 product ions, while the isomer denoted by ● (c) demonstrates a dibromohydroquinone MS2 product ion. These disparate MS/MS signatures led to the identification of structural differences between the two isomeric OH-BDEs. (d) EIC for [M–H]1− 516.69 Da identified two tetrabrominated di-OH-BDEs, of which the isomer denoted by ■ demonstrated (e) a major MS2 product ion corresponding to loss of one bromine atom. The other isomer demonstrates two major MS2 ions, (f) corresponding to dibromophenol and dibromotrihydroxybenzene moieties, that can be rationalized based on the final deduced structure of 8 (vide infra).

Regio-isomerism within naturally produced di-OH-BDEs is similarly revealed by an EIC for 516.69 Da (Figure 3d), which corresponds to the dominant [M–H]1− ion associated with the molecular formula C12H6Br4O3. The isomer denoted by ■ generates a single MS2 product ion corresponding to the loss of a bromine atom (Figure 3e), a characteristic feature for di-OH-BDEs that possess the two phenoxyls at the 2′ and 6 positions.31 The other tetrabrominated di-OH-BDE isomer (8) demonstrated two major MS2 product ions that could be annotated to dibromophenol and dibromotrihydroxyphenol (Figure 3f). The observation of a trihydroxyphenol MS2 product ion clearly showed that 8 differs in the nature of the ether linkage from ■, in that all three oxygen atoms could be localized to a single ring. Guided by MS, a preparative scale purification and comprehensive structural characterization of 8 was pursued (SI Figures 11–16). The 1H NMR spectrum of 8 demonstrated the presence of four aromatic protons, of which three could be placed on Ring A. Upon comparison of the 1H and 13C shifts to published values,6 Ring A was clearly assigned as the ubiquitous 2,4-dibromophenyl moiety, likely to be biosynthetically derived from the bromophenol monomer 4. Guided by the characteristic TFA adducts demonstrated by purified 8 in a LC-MS/MS experiment (SI Figures 17–19), we postulated that the two hydroxyls on Ring B should be arranged as a catechol, as also observed in the bromocatechol monomer 5. In addition to the two catechol hydroxyls, Ring B contains two bromine atoms and the oxygen atom that participates in formation of the ether linkage between Ring A and Ring B. This rationale is supported by the observation of the fourth aromatic proton as a singlet in the 1H NMR spectrum of 8. A heteronuclear multiple bond correlation (HMBC) experiment, together with the 13C NMR spectrum demonstrated that the singular proton on Ring B was involved in 2-bond and 3-bond HMBC correlations with the three aryl carbon atoms that bear the oxygen atoms, along with only one of the two aryl carbons bearing the bromine atoms. This finding excludes the possibility that 8 corresponds to the molecular species shown in Figure 1g. The only two possible arrangements of the B ring of 8 that are consistent with the above observations are shown in Figure 4 as i and ii. Furthermore, observation of the chemical shifts of 6′ proton of Ring A (1H δ = 6.4 ppm; 13C δ = 116.8 ppm) also leads to the inference that the 2-position of Ring B is brominated,6 a constraint that is satisfied by both i and ii.

Figure 4.

Structure elucidation of 8. (a) HMBC correlations observed for 8 which lead to the assignment of Ring A, with (b) two possible structures of Ring B that were differentiated by comparison to authentic synthetic standards 9 and 10.

In order to differentiate between the two possibilities for Ring B in compound 8, 9 and 10 were synthesized by N-bromosuccinimide catalyzed bromination of 4-methoxy-1,2-benzenediol to yield 4-bromo-5-methoxy-1,2-benzenediol (SI Figure 20), followed by a second bromination to yield a mixture of two isomeric products that were separated by HPLC. In addition to the 1H, 13C, and HMBC NMR experiments, the structures of the two isomers could be unequivocally differentiated on the basis of a key nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) correlation between the solitary aryl proton and the methoxy protons that was only observed for 10 (Figure 4 and SI Figures 21–34). 9 and 10 respectively serve as mimics for Ring B possibilities i and ii, with Ring A in i and ii substituted by a methyl group in 9 and 10, respectively. Upon comparison of the 13C NMR shifts and similarities in the HMBC spectra, it was abundantly clear that Ring B bears close resemblance to 9, thus leading to a complete structural assignment for 8. The structure of compound 8 can be rationalized on the basis of radical coupling between the bromophenol-bromocatechol monomers 4 and 5 detected in the same sponge, albeit now in a different aryl coupling conformation consistent with the molecular species shown in Figure 1h, as compared to previously described di-OH-BDE skeletons as shown in Figure 1f and 1g.

LC-MS/MS analyses for the extract of L. herbacea revealed a PBDE (11) with an unexpected MS profile with a [M–H]1− dominant ion at 546.70 Da corresponding to the molecular formula C13H8Br4O4, a tetrabromotrihydroxylated PBDE in which one of the three phenoxyls are methylated (Figure 5). This observation is consistent with methoxylation being a dominant feature for PBDEs present in the extract of L. herbacea, as also exemplified by 3. A major dibromotrihydroxyphenyl MS2 product ion was observed for 11, identical to that previously found for 8. Together with the mass spectral demonstration of a TFA adduct for purified 11 (SI Figure 35), a structural homology to 8 was immediately apparent. A preparative scale purification and NMR characterization for 11 could be achieved (SI Figure 36–39). NMR experiments revealed the presence of three aromatic protons, of which two were positioned meta to each other on Ring A. Similarity of NMR chemical shifts to those for Ring B of 3 led to the assignment of Ring A for 11. Ring B of 11 possessed a single aromatic proton signal, which shows near identical 1H shifts and HMBC correlations to Ring B of 8, thus leading to a complete structural assignment for 11 as shown in Figure 5. This structure corresponds to the catechol-catechol coupled molecular species as shown in Figure 1j. Structure elucidation of 11 brings to fore the technical challenges associated with less abundant naturally produced PBDEs that is complicated by low H:C ratios associated with these molecules. As described above, these challenges can be offset by analyses of authentic synthetic standards of individual PBDE rings, and rationalization of core structures based on MS2 product ions. To the best of our knowledge, core structures for 8 and 11 are not represented among known PBDE structures.

Figure 5.

MS/MS profile of 11. EIC for [M–H]1− 546.70 Da identifies one major brominated molecule in the extract of L. herbacea. Only one major dibromotrihydroxybenzene MS2 product ion could be observed, analogous to that for 8 (Figure 3f), that can be rationalized on the basis of the deduced structure for 11 (vide infra).

Mining the L. herbacea and D. granulosa metabolomes using MS additionally revealed that the diversity in PBDE structures is generated not only during biosynthesis via differential biradical coupling, but also by postassembly halogenation by substrate promiscuous “off-pathway” chlorinases to generate a multitude of small abundance mixed polyhalogenated diphenyl ethers. For instance, proceeding from the most abundant PBDE congener present in the extracts of L. herbacea-3, (Figure 2b) we detected two isomers corresponding to the molecular formula C13H7Br4ClO3 (12) ([M–H]1− mass obs.: 560.6739 Da; mass calc.: 560.6744; Δ = 0.9 ppm) (Figure 6a–b and SI Figure 40). Note that 12 represents one chloronium addition afforded upon 3. Furthermore, the site for chlorination can be unequivocally localized to the Ring A of 3, as a characteristic MS2 product ion is detected for both isomers of 12 that is greater than the MS2 product ion for 3 by mass corresponding to a chlorine adduct (Figure 6c). Hence it can be reasoned that detection of two peaks in an EIC for 12 (Figure 6b) represents both possible products corresponding to the electrophilic chloronium addition occurring on Ring A of 3 at either the ortho- or para- positions relative to the phenoxyl. It should be noted that methylation of the phenoxyl on Ring B makes it less susceptible to electrophilic aromatic substitution, together with both the ortho- and para- positions on Ring B being already brominated.

Figure 6.

Off-pathway halogenation of PBDEs as revealed by MS. (a) Proposed sequence of chlorination and bromination steps that lead to the formation of two isomers each for 12, 13, and 15, and single products 14 and 16. The proposed structures of the mixed polyhalogenated diphenyl ethers, with additional halogenations upon 3 (vide infra) localized to Ring A are shown. (b) EICs showing two closely eluting isomeric products corresponding to the molecular formulas for 12, 13, and 15, but only single products for 14 and 16. These observations corroborate the scheme shown in Panel A. All EICs are generated within 10 ppm tolerance. (c) MS/MS profile of 3 demonstrates a single major MS2 product ion corresponding to dihydroxydibromobenzene, which can be rationalized to be derived from Ring A as shown. MS2 product ions observed for 12–16 can similarly be rationalized to be derived from their respective Ring As, but with additional halogen adducts as shown. Note that methoxylation of di-OH-BDEs dramatically alters their MS/MS profiles as compared to Figure 3e. The other MS2 ions observed in every MS/MS spectra correspond to the loss of the methyl group, along with a bromine atom from the respective parent molecule. MS1 profiles for 3 and 12–16 are shown in SI Figure 40.

Using an identical approach, but now for addition of bromine atoms, we could also detect two isomers in an EIC corresponding to the molecular formula C13H7Br5O3 (13) ([M–H]1− mass obs.: 604.6228 Da; mass calc.: 604.6239; Δ = 1.8 ppm) which likely represents the two possible products corresponding to an additional bromination (in contrast to chlorination leading to 12) afforded upon Ring A of 3. As for 12, both isomers corresponding to 13 generate an identical MS2 product ion that is greater than the MS2 product ion for 3 by mass corresponding to bromine adduct afforded upon Ring A (Figure 6c).

As characterized by the MS2 product ions, it can be rationalized that further chlorination on Ring A of either isomer of 12 would generate a single product, 14 ([M–H]1− mass obs.: 594.6332 Da; mass calc.: 594.6355; Δ = 3.8 ppm), which is observed as one single peak in the EIC. However, bromination of the two isomers of 12 would generate two distinct isomeric products, 15 ([M–H]1− mass obs.: 638.5844 Da; mass calc.: 638.585; Δ = 1.0 ppm), that are detected as two distinct peaks in the EIC. Note that the two isomers corresponding to 15 can also be generated by chlorination of Ring A for the two isomers corresponding to 13. Analogous to the synthesis of 14, a second bromination event for either isomer for 13 would generate an identical hexabrominated product- 16 ([M–H]1− mass obs.: 682.5309 Da; mass calc.: 682.5344; Δ = 5.1 ppm). To the best of our knowledge, di-OH-BDEs with mixed halogenated patterns have not been previously reported in the literature. Thus, using MS, we now reveal the presence of novel di-OH-BDEs 12, 14 and 15. Note that due to their low abundance and close retention times, the presence of 12–16 could not be attributed to distinct peaks observed on a UV–vis absorbance chromatogram.

Devoid of precedent from PBDE isolation literature is the existence of iodinated PBDEs. Using MS as a natural product mining approach, we could detect iodinated derivatives of 3, analogous to, but in even lower abundance than 12–16. A single monoiodinated PBDE could be detected (17, Figure 7, [M–H]1− mass obs.: 652.6087 Da; mass calc.: 652.6101; Δ = 2.1 ppm) that demonstrates a characteristic MS2 product ion, which establishes that the iodine atom is localized on Ring A (SI Figure 41). Analogous to 15 and 14, derivatives of 3 bearing one additional bromine and one additional iodine atoms (18, [M–H]1− mass obs.: 732.5181 Da; mass calc.: 730.5206; Δ = 3.4 ppm), and two additional iodine atoms (19, [M–H]1− mass obs.: 778.5042 Da; mass calc.: 778.5067; Δ = 3.2 ppm) could also be detected (Figure 7). As before, MS2 product ions unambiguously positioned the additional bromine and iodine atoms on Ring A (SI Figure 41). Proceeding from the above logic, we could also detect a derivative of 3 that possesses one chlorine and one additional iodine atom on Ring A (20, [M–H]1− mass obs.: 686.5735 Da; mass calc.: 686.5711; Δ = 3.6 ppm) (Figure 7 and SI Figure 42), hence establishing the presence of a PBDE molecule bearing all three commonly occurring halogen atoms concomitantly.

Figure 7.

Postulated chemical structures for iodinated PBDEs 17–20. Based on MS, it cannot be determined if the iodine atom for 17 is positioned at either the 3′ or the 5′ position on Ring A. Also note that the 3′-I and 5′-Br atoms for 18, and 3′-Cl and 5′-I atoms for 20 can be interchanged to give identical MS1 and MS2 spectra.

An identical pattern of “off-pathway” chlorination and bromination could be observed for 1 (SI Figure 43), which is the dominant metabolite present in the extracts of D. granulosa. As 1, and derivatives thereof do not fragment under LC-MS/MS conditions used in this and prior studies,19,30 it cannot be unequivocally discerned whether additional halogenations for 1 are localized to a single ring or not. However, consistent with prior synthetic observations,32,33 biosynthetic logic dictates that these adducts would occur on Ring B of 1 due to the presence of an activating phenoxyl and both ortho- and para- positions being available for halogenation. Derivatives of 1 bearing one additional iodine atom ([M–H]1− mass obs.: 622.5978 Da; mass calc.: 622.5995; Δ = 2.7 ppm), and one additional bromine and one iodine atoms ([M–H]1− mass obs.: 700.5089 Da; mass calc.: 700.51; Δ = 1.5 ppm) could also be detected using their MS1 spectra. However, a derivative of 1 bearing two iodine atoms was not detected.

The still elusive PBDE biosynthetic pathway present in Dysidea sponges likely possesses an “on-pathway” dedicated phenol brominase leading to the formation of bromophenols and bromocatechols that are subsequently coupled to generate PBDEs. As a physiological phenol brominase would be incapable of catalyzing chlorination of 1 and 3,34 it is likely that the sponge proteome bears additional broadly substrate promiscuous chlorinases that lead to “off-pathway” chlorination of major PBDE metabolites present within the sponge. The marine metabolome is exceptionally rich in chlorinated natural products, and substrate promiscuous marine chlorinases have been biochemically characterized that chlorinate model substrates such as monochlorodimedone, together with alkyl halides and terpenoids, among other reactions.35–37 While a chlorinase in theory could brominate and iodinate as well, the contribution of additional nonphysiological substrate promiscuous brominases and iodinases in the biosyntheses of brominated and iodinated derivates of 1 and 3 cannot be discounted. It is unlikely that PBDE modifying halogenases are dedicated enzymes present within PBDE biosynthetic gene loci. This assertion is supported by the observation that as compared to 3, 12–20 are far less abundant within the sponge extract, thus implying a biosynthetic disconnect in their production. The relative decrease in abundance of iodinated derivatives of 3, as compared to chlorinated and brominated derivates can be rationalized on the basis of higher concentrations of chloride and bromide in seawater as compared to iodide. Perhaps, this difference can also be attributed to chlorinases and brominases being pervasive in the marine proteome, which also manifests itself as an abundance of chlorinated and brominated natural products present in the marine metabolome, as compared to iodinated molecules.38

The new structural classes of PBDEs described in this study, together with the chlorinated and iodinated derivatives expands the possible bioactivity profile of sponge derived PBDEs. While the disruption of thyroid hormone signaling activity of p-OH-BDEs has been described in literature previously,26,27 it should be noted that our previous20 and current results now direct attention to the ubiquity of bromocatechol derived di- and tri-OH-BDEs as marine derived natural products that coinhabit the chemical space occupied by OH-BDEs. Catechol is widely recognized as a privileged bioactivity conferring synthon. The presence of the catechol moiety ranges from the catecholamine class of human hormones and neurotransmitters, to some of the most abundant and bioactive plant flavanoids present in the human diet,39 and even within microbes, where the catecholate siderophores are used to chelate ferric ions.40 It can be speculated that bromocatechols, and di- and tri-OH-BDEs will explore new and varied targets within mammalian systems to exert their, as yet unexplored mechanisms of bioactivity, and possibly toxicity as well. Furthermore, halogenation has been established to be a bioactivity conferring modification routinely afforded upon natural products.41 While chlorinated and iodinated PBDE derivatives are not routinely included in studies assessing the toxicity of PBDEs, our findings establish that parent OH- and di-OH-BDEs can be converted to mixed halogenated congeners, which owing to their increasing hydrophobicity and membrane permeability42 may be even more bioactive than their parent congeners. Recent reports43,44 establishing their presence in dolphin blubber lend further support for including mixed polyhalogenated diphenyl ethers in future toxicology investigations.

Studies aiming to inventory the polyhalogenated pollutants in complex environmental matrices in a nontargeted fashion have relied on using gas chromatography coupled mass spectrometry (GC-MS) as the analytical method of choice.45 This reliance on GC-MS is in part borne out of the availability of spectral libraries that aid in identification of molecules of interest. Our approach now offers LC-MS/MS as a complementary nontargeted analytical approach that is particularly useful in the detection of naturally produced PBDEs that are hydroxylated and may require additional chemical derivitization to be amenable for GC-MS. Furthermore, as efforts toward detecting PBDEs transition away from marine mammal blubber as the traditional analyte of choice15,33,43,44 to other biologically relevant matrices such as blood, serum, and breast milk from nursing mothers, we expect that LC-MS/MS will prove to be a widely applicable technique for detection of polar PBDE congeners present in these aqueous analytes. In conclusion, our findings expand the chemical space explored by PBDEs and set the stage for dedicated studies that will aim to tease apart the different mechanisms of toxicity associated with different structural classes of PBDEs that are represented in the natural metabolome.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank our UCSD colleague B. M. Duggan for assistance with NMR data acquisition and analysis, and SMS intern Lindsay Spiers for assistance with collecting sponge samples. Funding was generously provided by the NIH (P01-ES021921) and NSF (OCE-1313747) through the Oceans and Human Health program, NIH instrumentation grant S10-RR031562, and the Helen Hay Whitney Foundation via a postdoctoral fellowship to V.A. V.J.P. acknowledges partial support from the NIH (R01-CA172310) for sample collection.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Additional methods and figures are provided as Supporting Information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org. Mass spectrometry data reported in this study has been made freely available on the Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GnPS) database at http://gnps.ucsd.edu.

Author Contributions

V.A., V.J.P. and B.S.M. conceived the study, V.A., J.L., I.R., M.B., and L.I.A. performed experiments. J.S.B. and V.J.P. identified and collected sponge specimens, V.A. and B.S.M. analyzed data and compiled the manuscript with input from all authors.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Wiseman SB, Wan Y, Chang H, Zhang X, Hecker M, Jones PD, Giesy JP. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers and their hydroxylated/methoxylated analogs: Environmental sources, metabolic relationships, and relative toxicities. Mar Pollut Bull. 2011;63(5–12):179–88. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Segraves EN, Shah RR, Segraves NL, Johnson TA, Whitman S, Sui JK, Kenyon VA, Cichewicz RH, Crews P, Holman TR. Probing the activity differences of simple and complex brominated aryl compounds against 15-soybean, 15-human, and 12-human lipoxygenase. J Med Chem. 2004;47(16):4060–5. doi: 10.1021/jm049872s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canton RF, Scholten DE, Marsh G, de Jong PC, van den Berg M. Inhibition of human placental aromatase activity by hydroxylated polybrominated diphenyl ethers (OH-PBDEs) Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;227(1):68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de la Fuente JA, Manzanaro S, Martin MJ, de Quesada TG, Reymundo I, Luengo SM, Gago F. Synthesis, activity, and molecular modeling studies of novel human aldose reductase inhibitors based on a marine natural product. J Med Chem. 2003;46(24):5208–21. doi: 10.1021/jm030957n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Legradi J, Dahlberg AK, Cenijn P, Marsh G, Asplund L, Bergman A, Legler J. Disruption of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) by hydroxylated polybrominated diphenyl ethers (OH-PBDEs) present in the marine environment. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48(24):14703–11. doi: 10.1021/es5039744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calcul L, Chow R, Oliver AG, Tenney K, White KN, Wood AW, Fiorilla C, Crews P. NMR strategy for unraveling structures of bioactive sponge-derived oxy-polyhalogenated diphenyl ethers. J Nat Prod. 2009;72(3):443–9. doi: 10.1021/np800737z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carte B, Faulkner DJ. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers from Dysidea herbacea, Dysidea chlorea and Phyllospongia foliascens. Tetrahedron. 1981;37(13):2335–2339. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuniyoshi M, Yamada K, Higa T. A biologically-active diphenyl ether from the green-alga Cladophora fascicularis. Experientia. 1985;41(4):523–524. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanif N, Tanaka J, Setiawan A, Trianto A, de Voogd NJ, Murni A, Tanaka C, Higa T. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers from the Indonesian sponge Lamellodysidea herbacea. J Nat Prod. 2007;70(3):432–5. doi: 10.1021/np0605081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitamura M, Koyama T, Nakano Y, Uemura D. Corallinafuran and Corallinaether, novel toxic compounds from crustose Coralline red algae. Chem Lett. 2005;34(9):1272–1273. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu X, Schmitz FJ, Govindan M, Abbas SA, Hanson KM, Horton PA, Crews P, Laney M, Schatzman RC. Enzyme inhibitors: New and known polybrominated phenols and diphenyl ethers from four Indo-Pacific Dysidea sponges. J Nat Prod. 1995;58(9):1384–91. doi: 10.1021/np50123a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Becerro MA, Paul VJ. Effects of depth and light on secondary metabolites and cyanobacterial symbionts of the sponge Dysidea granulosa. Mar Ecol: Prog Ser. 2004;280:115–128. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Unson MD, Holland ND, Faulkner DJ. A brominated secondary metabolite synthesized by the cyanobacterial symbiont of a marine sponge and accumulation of the crystalline metabolite in the sponge tissue. Mar Biol. 1994;119(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vetter W, Stoll E, Garson MJ, Fahey SJ, Gaus C, Muller JF. Sponge halogenated natural products found at parts-per-million levels in marine mammals. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2002;21(10):2014–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teuten EL, Xu L, Reddy CM. Two abundant bioaccumulated halogenated compounds are natural products. Science. 2005;307(5711):917–20. doi: 10.1126/science.1106882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haraguchi K, Kato Y, Ohta C, Koga N, Endo T. Marine sponge: A potential source for methoxylated polybrominated diphenyl ethers in the Asia-Pacific food web. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59(24):13102–9. doi: 10.1021/jf203458r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang HS, Du J, Ho KL, Leung HM, Lam MH, Giesy JP, Wong CK, Wong MH. Exposure of Hong Kong residents to PBDEs and their structural analogues through market fish consumption. J Hazard Mater. 2011;192(1):374–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zota AR, Park JS, Wang Y, Petreas M, Zoeller RT, Woodruff TJ. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers, hydroxylated polybrominated diphenyl ethers, and measures of thyroid function in second trimester pregnant women in California. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45(18):7896–905. doi: 10.1021/es200422b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agarwal V, El Gamal AA, Yamanaka K, Poth D, Kersten RD, Schorn M, Allen EE, Moore BS. Biosynthesis of polybrominated aromatic organic compounds by marine bacteria. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10(8):640–7. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agarwal V, Moore BS. Enzymatic synthesis of polybrominated dioxins from the marine environment. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9(9):1980–4. doi: 10.1021/cb5004338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aldemir H, Richarz R, Gulder TA. The biocatalytic repertoire of natural biaryl formation. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53(32):8286–93. doi: 10.1002/anie.201401075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin K, Gan J, Liu W. Production of hydroxylated polybrominated diphenyl ethers from bromophenols by bromoperoxidase-catalyzed dimerization. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48(20):11977–83. doi: 10.1021/es502854e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin K, Yan C, Gan J. Production of hydroxylated polybrominated diphenyl ethers (OH-PBDEs) from bromophenols by manganese dioxide. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48(1):263–71. doi: 10.1021/es403583b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu H, Namikoshi M, Meguro S, Nagai H, Kobayashi H, Yao X. Isolation and characterization of polybrominated diphenyl ethers as inhibitors of microtubule assembly from the marine sponge Phyllospongia dendyi collected at Palau. J Nat Prod. 2004;67(3):472–4. doi: 10.1021/np0304621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dingemans MM, van den Berg M, Westerink RH. Neurotoxicity of brominated flame retardants: (In) direct effects of parent and hydroxylated polybrominated diphenyl ethers on the (developing) nervous system. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(7):900–7. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li F, Xie Q, Li X, Li N, Chi P, Chen J, Wang Z, Hao C. Hormone activity of hydroxylated polybrominated diphenyl ethers on human thyroid receptor-beta: In vitro and in silico investigations. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(5):602–6. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ucan-Marin F, Arukwe A, Mortensen AS, Gabrielsen GW, Letcher RJ. Recombinant albumin and transthyretin transport proteins from two gull species and human: Chlorinated and brominated contaminant binding and thyroid hormones. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44(1):497–504. doi: 10.1021/es902691u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang H, Skildum A, Stromquist E, Rose-Hellekant T, Chang LC. Bioactive polybrominated diphenyl ethers from the marine sponge Dysidea sp. J Nat Prod. 2008;71(2):262–4. doi: 10.1021/np070244y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bouslimani A, Sanchez LM, Garg N, Dorrestein PC. Mass spectrometry of natural products: Current, emerging and future technologies. Nat Prod Rep. 2014;31(6):718–29. doi: 10.1039/c4np00044g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mas S, Jauregui O, Rubio F, de Juan A, Tauler R, Lacorte S. Comprehensive liquid chromatography-ion-spray tandem mass spectrometry method for the identification and quantification of eight hydroxylated brominated diphenyl ethers in environmental matrices. J Mass Spectrom. 2007;42(7):890–9. doi: 10.1002/jms.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kato Y, Okada S, Atobe K, Endo T, Haraguchi K. Selective determination of mono- and dihydroxylated analogs of polybrominated diphenyl ethers in marine sponges by liquid-chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2012;404(1):197–206. doi: 10.1007/s00216-012-6132-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marsh G, Stenutz R, Bergman A. Synthesis of hydroxylated and methoxylated polybrominated diphenyl ethers – Natural products and potential polybrominated diphenyl ether metabolites. Eur J Org Chem. 2003;14:2566–2576. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marsh G, Athanasiadou M, Athanassiadis I, Bergman A, Endo T, Haraguchi K. Identification, quantification, and synthesis of a novel dimethoxylated polybrominated biphenyl in marine mammals caught off the coast of Japan. Environ Sci Technol. 2005;39(22):8684–90. doi: 10.1021/es051153v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blasiak LC, Drennan CL. Structural perspective on enzymatic halogenation. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42(1):147–55. doi: 10.1021/ar800088r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winter JM, Moore BS. Exploring the chemistry and biology of vanadium-dependent haloperoxidases. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(28):18577–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.001602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Butler A, Carter-Franklin JN. The role of vanadium bromoperoxidase in the biosynthesis of halogenated marine natural products. Nat Prod Rep. 2004;21(1):180–8. doi: 10.1039/b302337k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carter-Franklin JN, Butler A. Vanadium bromoperoxidase-catalyzed biosynthesis of halogenated marine natural products. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126(46):15060–15066. doi: 10.1021/ja047925p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gribble GW. The diversity of naturally produced organohalogens. Chemosphere. 2003;52(2):289–97. doi: 10.1016/S0045-6535(03)00207-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Erlund I. Review of the flavonoids quercetin, hesperetin naringenin. Dietary sources, bioactivities, and epidemiology. Nutr Res (NY) 2004;24(10):851–874. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hider RC, Kong XL. Chemistry and biology of siderophores. Nat Prod Rep. 2010;27(5):637–657. doi: 10.1039/b906679a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neumann CS, Fujimori DG, Walsh CT. Halogenation strategies in natural product biosynthesis. Chem Biol. 2008;15(2):99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gerebtzoff G, Li-Blatter X, Fischer H, Frentzel A, Seelig A. Halogenation of drugs enhances membrane binding and permeation. Chembiochem. 2004;5(5):676–684. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shaul N, Dodder NG, Aluwihare LI, Mackintosh S, Maruya KA, Chivers S, Danil K, Weller D, Hoh E. Nontargeted biomonitoring of halogenated organic compounds in two ecotypes of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) from the Southern California Bight. Environ Sci Technol. 2014 doi: 10.1021/es505156q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoh E, Dodder NG, Lehotay SJ, Pangallo KC, Reddy CM, Maruya KA. Nontargeted comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography/time-of-flight mass spectrometry method and software for inventorying persistent and bioaccumulative contaminants in marine environments. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46(15):8001–8. doi: 10.1021/es301139q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang D, Li QX. Application of mass spectrometry in the analysis of polybrominated diphenyl ethers. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2010;29(5):737–75. doi: 10.1002/mas.20263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.