Abstract

After Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (RYGB), patients report consuming fewer fatty and dessert-like foods, and rats display blunted sugar and fat preferences. Here we used a progressive ratio task (PR) in our rat model to explicitly test whether RYGB decreases the willingness of rats to work for very small amounts of preferred sugar- and/or fat-containing fluids. In each of two studies, two groups of rats - one maintained on a high-fat diet (HFD) and standard chow (CHOW) and one given CHOW alone - were trained while water-deprived to work for water or either Ensure or 1.0 M sucrose on increasingly difficult operant schedules. When tested before surgery while nondeprived, HFD rats had lower PR breakpoints (number of operant responses in the last reinforced ratio) for sucrose, but not for Ensure, than CHOW rats. After surgery, at no time did rats given RYGB show lower breakpoints than SHAM rats for Ensure, sucrose, or when 5% Intralipid served postoperatively as the reinforcer. Nevertheless, RYGB rats showed blunted preferences for these caloric fluids versus water in 2-bottle preference tests. Importantly, although the Intralipid and sucrose preferences of RYGB rats decreased further over time, subsequent breakpoints for them were not significantly impacted. Collectively, these data suggest that the observed lower preferences for normally palatable fluids after RYGB in rats may reflect a learned adjustment to altered postingestive feedback rather than a dampening of the reinforcing taste characteristics of such stimuli as measured by the PR task in which postingestive stimulation is negligible.

Keywords: motivation, reward, bariatric surgery, operant behavior, progressive ratio

1. INTRODUCTION

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (RYGB) is an effective and long-lasting way to reduce body mass in obese patients [see 1–3]. One means by which weight loss is achieved following this surgery is through a substantial reduction in energy intake [e.g., 4–8]. It has been suggested that food intake is not only globally reduced in terms of mass and/or volume, but also that certain foods high in fat and/or sugar are selected less often [e.g., 4, 6, 9, 10] and that the overall average caloric density of the diet that patients select is decreased after RYGB [8]. While the majority of these findings have been derived through the use of self-report measures, which have limitations in their objectivity and accuracy and may result in variability [e.g., 11–15; see also 16], these inferences are supported by data gathered from a rat model of RYGB that closely resembles the operation performed in humans [e.g., 17]. Compared to sham-operated animals, RYGB rats display lower intakes of and preferences for high-energy diets [9, 18–21], sucrose [22], the soybean oil emulsion Intralipid [9], and the complete-nutrition supplement Ensure [18, 19, 23] when investigated in long-term tests.

The shifts in preference away from sweet fat-containing foods and fluids in humans and rats after RYGB may be the result of effects on factors that promote feeding and its continuation (e.g., taste, hunger) and/or factors that stop feeding and prevent its initiation [e.g., postingestive consequences, satiation, malaise; c.f., 24]. One way to experimentally distinguish between these various contributions is through the use of the progressive ratio (PR) task, which has proven utility in the assessment of taste reward while minimizing satiation as it is a task sensitive to manipulations that impinge on reinforcer value, such as food-deprivation and stimulus concentration [e.g., 25]. In the PR task, the animal is required to perform an operant behavior (e.g., lever pressing, licking, etc.) under a schedule in which the workload increases after the delivery of each reinforcer. On a linear PR schedule, the number of responses required for access to a single reinforcer increases a set amount on each successive trial; for example, on a PR10 schedule, the first reinforcer 'costs' 10 operant responses, the next requires 20, the next 30, and so on. The PR task evaluates nearly pure appetitive behavior, which consist of responses during periods when the animal is not in contact with the stimulus (i.e., reinforcer). Because the workload escalates quickly, access to the reinforcer is limited and caloric ingestion is severely restricted. Consequently, postingestive stimulation is negligible and the behavior is driven primarily by the unconditioned orosensory properties (e.g., taste) of the reinforcer in the context of the current physiological state of the animal. The number of operant responses generated in the final reinforced trial is referred to as the breakpoint and is considered an indication of the amount of work that the subject was prepared to exert for the reinforcer. Therefore, the breakpoint serves as a proxy of the value of the reinforcer.

Using the PR task, Miras et al [26] showed that RYGB patients had lower breakpoints (clicks on a computer mouse) when a small chocolate candy served as the reinforcer compared with their preoperative performance. Normal-weight controls assessed at comparable time points had stable breakpoints, and, while they did not differ from RYGB patients that were morbidly obese presurgically, they did postsurgically. The breakpoint for vegetables in patients before and after RYGB was unchanged suggesting that, in humans, RYGB blunts the willingness to work for a sweet and fatty snack food, but not for vegetables.

Here we sought to study the effect of RYGB in rats on the reinforcement value of palatable fluid stimuli by using a lick operant [e.g., 27–31]. The rat model has some complementary advantages for studying the effects of RYGB on food-related motivation as observed clinically as rats are unencumbered by cognitive and social demands and are not subject to nutritional counseling. Moreover, rat models are amenable to the application of controlled and invasive manipulations in attempts to experimentally unravel the potential mechanisms underlying RYGB-induced behavioral effects.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. General Methods

2.1.1. Animal Subjects

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River) served as subjects in both studies. All rats were housed individually in polycarbonate cages lined with wood chip bedding (unless otherwise noted) in a vivarium room in which temperature, humidity, and light (12:12-hour light:dark cycle, lights on at 7:00 AM) were controlled automatically. The rats were provided with a maintenance diet of standard laboratory chow pellets (CHOW; PMI 5001;Table 1) held in two identical stainless steel hanging food hoppers or with CHOW in one hopper and high-fat diet pellets (HFD; Research Diets D12492; Table 1) in the other. This HFD contains slightly less sugars proportionally than CHOW, but does contain significant amounts of maltodextrin. All rats had ad libitum access to their respective maintenance diets and deionized water unless otherwise noted. All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Florida State University.

Table 1.

Nutritional information about the foods and fluid stimuli used.

| Nutritional Stimulus | Caloric Density |

% Calories from Fat |

% Calories from Sugar1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chow | 3.36 kcal /g | 14% | 7% |

| High-fat diet | 5.24 kcal/g | 60% | 7% |

| Milk-chocolate Ensure Plus | 1.48 kcal/ml | 28% | 25% |

| 5% Intralipid | 0.5 kcal/ml | 100% | 0% |

| 1.0 M sucrose | 1.19 kcal/ml | 0% | 100% |

Only mono- and disachharides and does not include maltodextrin and more complex carbohydrates.

2.1.2. Test Stimuli

Reverse-osmosis deionized water; the complete-nutrition shake, milk-chocolate flavored Ensure Plus (Abbot Laboratories); the soybean oil emulsion, Intralipid (Sigma-Aldrich; 5–10%); and/or sucrose solution (Avantor Performance Materials; 0.1–1.0 M) were presented to the rats at room temperature during the behavioral tasks detailed below (see Table 1 for nutritional information).

2.1.3 Progressive Ratio Behavioral Task

Training and testing of the rats took place in an apparatus known as a Davis rig [Davis MS-160, DiLog Instruments; see 32]. At the center of the front wall of the animal holding chamber of the apparatus is a slot that serves as an access port through which the rat can lick a stainless steel drinking spout. The spouts (and bottles to which they are attached) are positioned in a rack that, under computer control, moves horizontally such that different spouts can be positioned one at a time behind the access port. When the rack moves, a stainless steel shutter closes behind the access port, preventing the rat from licking. Each lick taken while the shutter is open is registered by a contact circuit and the data are saved to a computer for future analysis. While in the Davis rig, the rats did not have access to their maintenance diet(s) and were delivered fluid based on the protocols described below.

Initially, the rats were trained while ~23-h water-deprived to lick water from a drinking spout while the shutter remained open. On subsequent sessions access to the drinking spout was interrupted by the closing of the shutter. Then the rats were trained to work for fluid access across sessions that required increasingly effortful operant workloads (Tables 2 and 3). Pre- and postsurgical tests consisted of performance for a fluid on a linear progressive ratio (PR) 10 and/or PR3 while the rats were nondeprived or ~23-h food-deprived. The operant behavior required consisted of a lick on a dry spout. Once the criterion number of licks on the dry spout was met, the shutter closed, the rack positioned a spout containing fluid behind the access slot, and the shutter opened. Rats were then allowed a 10-s access period during which they could lick the fluid up to 15 times (~75 µl). The session ended when a rat stopped emitting operant behavior for 3 min or the session length exceeded 1 h. During all operant schedules, the first trial required only 1 operant lick so as to provide the rats with a ‘refresher’ trial.

Table 2.

Training and operant testing procedures on fixed ratio (FR) and progressive ratio (PR) schedules of reinforcement and preference testing procedures in Experiment 1 for rats prior to and after either Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (RYGB) or sham operations (SHAM).

| Phase | Stimulus | State | Access Schedule | # of Sessions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operant Training | Water | Water-deprived | Ad libitum | 8 |

| FR10 | 3 | |||

| PR3 | 3–5 | |||

| PR10 | 3–5 | |||

| Ensure | PR10 | 3 | ||

| Operant Testing | Ensure | Nondeprived | PR10 | 3 |

| Surgery (RYGB or SHAM, performed across 2 weeks; rats given at least 17 days to recover) | ||||

| Operant Testing | Ensure | Nondeprived | PR10 | 3 |

| 2-Bottle Testing | Ensure | Nondeprived | Ad libitum | 4 |

| Operant Testing | 5% Intralipid | Nondeprived | PR10 | 3 |

| PR3 | 3 | |||

| 2-Bottle Testing | 5% Intralipid | Nondeprived | Ad libitum | 4 |

| Operant Testing | 5% Intralipid | Nondeprived | PR3 | 3 |

Table 3.

Training and operant testing procedures on fixed ratio (FR) and progressive ratio (PR) schedules of reinforcement and preference testing procedures in Experiment 2 for rats prior to and after either Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (RYGB) or sham operations (SHAM).

| Phase | Stimulus | State | Access Schedule | # of Sessions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operant Training | Water | Water-deprived | Ad libitum | 5 |

| FR3 | 3 | |||

| FR10 | 4 | |||

| PR3 | 3–5 | |||

| PR10 | 4 | |||

| 0.1 M Sucrose | PR10 | 2 | ||

| 0.3 M Sucrose | Nondeprived | PR10 | 1 | |

| 1.0 M Sucrose | Alternating Food- deprived / Nondeprived |

PR10 | 2 each | |

| Operant Testing | 1.0 M Sucrose | Nondeprived | PR10 | 3 |

| Surgery (RYGB or SHAM, performed across 9 days; rats given at least 21 days to recover) | ||||

| Operant Testing | 1.0 M Sucrose | Nondeprived | PR10 | 6 |

| 2-Bottle Testing | 1.0 M Sucrose | Nondeprived | Ad libitum | 4 |

| Operant Testing | 1.0 M Sucrose | Nondeprived | PR10 | 3 |

| Operant Testing | 1.0 M Sucrose | Food-deprived | PR10 | 2 |

2.1.4. Intake Measures

The rats were presented for 96 h with one of the fluids tested during the PR task and water in 250-ml glass bottles equipped with metal drinking spouts that were placed side-by-side on the stainless steel wire top of their home cage. Every 24 h, intake was measured, the bottles were removed, rinsed with deionized water, refilled with their respective fluids, and their positions switched to balance for side preferences.

2.1.5. Surgery and Recovery Procedures

On the evening prior to surgery, the rats were moved to a clean polycarbonate cage equipped with a raised stainless steel mesh floor and lined with an absorbable thin cardboard pad to prevent ingestion of wood chip bedding, which could lead to esophageal congestion and subsequent leakage of the gastrojejunostomy. At the same time, on the evening prior to surgery, the food hoppers were removed from the cages to ensure that the rats had a relatively empty gut for surgery, but the rats were left with ~10 g of CHOW to minimize postsurgical gorging. Deionized water remained available ad libitum.

Surgery was conducted under isoflurane anesthesia (2–5% delivered in 1 L/min O2) and aseptic conditions similar to that previously described [e.g., 17, 33]. For RYGB surgery, the small intestine was transected ~15 cm from the pylorus and the ends tied off with 5–0 PDSII suture (Ethicon), creating two stumps. To create the biliopancreatic limb, a small incision was made in the proximal stump, and, with the use of 7–0 PDSII suture (Ethicon), a side-to-side anastomosis was created with a similarly sized incision made in a portion of the small intestine positioned ~25 cm oral of the cecum (jejunojejunostomy). Next, the stomach was transected close to the esophageal junction, preserving no more than 3 mm of stomach; the remaining stomach was closed with 5–0 PDSII sutures. To create the alimentary limb, a small incision was made in the distal stump of the originally transected portion of jejunum, and an end-to-side anastomosis with the stomach wall was created using 7–0 PDSII suture (gastrojejunostomy). For the sham operation (SHAM), stitches were made at the site of the intestinal transection and jejuno-jejunostomy and along the front wall of the stomach. After either surgery, the abdominal muscle wall was closed in one layer with PDSII 5–0 suture, and the skin was closed with Vicryl 4–0 suture (Ethicon).

Each rat was injected prophylactically with the antibiotic Baytril (Bayer; 2.5 mg/kg sc) and the analgesic carprofen (Rimadyl, Pfizer; 5mg/kg sc) and with sterile saline (0.9%; 7–10 ml sc). When each rat recovered from anesthesia and was returned to its home cage, deionized water was provided ad libitum, but moist supplemental diets (described in each methods section, below) were provided instead of their regular maintenance diet(s) for at least two days. For three days following surgery, each animal received Baytril and carprofen (as above) in the late afternoon.

2.2. Experiment 1 – Ensure and Intralipid breakpoint and preference after RYGB or SHAM in CHOW and HFD-fed rats tested while nondeprived

2.2.1. Animal Subjects

The two groups of 20 rats used in this study were received 2 weeks apart. The first set was ~2 months of age upon receipt (average body weight on arrival = 262 g) and comprised the CHOW group (provided with chow only), and the second set was ~1.5 months of age (average body weight on arrival = 225 g) and comprised the HFD group (provided with HFD in addition to chow). The groups were received at different times and ages in an attempt to minimize absolute body weight differences at the time of surgery despite the different feeding regimens. For a total of 10 weeks, all of these rats were injected once weekly with an ivermectin suspension (Ivomec, Merial; 1% further diluted in propylene glycol and injected at 600 µg/kg, sc) as part of a treatment regimen for pinworms in the facility; this started during the 2nd week of training but ended prior to presurgical testing. It is important to stress that the ivermectin was not orally consumed and that both RYGB and SHAM groups were treated similarly. There were no ostensible detrimental effects of this treatment that we could discern.

2.2.2. Progressive Ratio Behavioral Task and Intake Measures

Ensure served as the reinforcer in the final training sessions, during presurgical nondeprived testing, and during postsurgical nondeprived testing (Table 2). Three days after the completion of postsurgical PR10 Ensure testing, the rats were presented for 96 h with Ensure and water in their home cages. Three days after that, the rats were tested while nondeprived first on a PR10, and then on a PR3 schedule of reinforcement, but this time 5% Intralipid served as the reinforcer. Two days after PR3 Intralipid testing, the rats were presented for 96 h with Intralipid and water in their home cages. Four days after 2-bottle testing, PR3 testing with Intralipid was repeated.

2.2.3. Surgery and Recovery Procedures

All surgeries were performed by one surgeon (C.C.) when the rats were, on average, 19 weeks old. No sooner than 1 h after recovery from anesthesia, the rats were presented with wet mash, which is a thin mixture of powdered CHOW and deionized water (~1:4), and were maintained on this for two days following surgery. On the third postsurgical day, the respective maintenance diets of the rats were returned. Of the 40 rats, 25 underwent RYGB surgery and 14 underwent SHAM surgery. One rat in the CHOW group displayed labored and rapid wet breathing prior to any operative manipulations, making surgery impossible, and so it was excluded from the study. After RYGB, 10 rats were terminated from the study due to postsurgical complications. Other common issues seen soon after RYGB surgery, such as loose or bloody stool or diarrhea, drooling, fever, and mild dehydration, were successfully treated with sc injections of saline, access to wet mash, and analgesics as needed and were completely resolved prior to the start of postsurgical testing. No rats died after SHAM surgery, but loose stool was occasionally observed, and a total of four rats unexpectedly displayed body weight loss and fever. All but one of these rats recovered with normal postsurgical maintenance (e.g., 3-day antibiotic and analgesic treatment and provision of wet mash) and administration of sc saline; one rat required an additional day of antibiotic and analgesic treatment. All rats were healthy during all phases of postsurgical testing. The final group sizes were CHOW-RYGB = 6, CHOW-SHAM = 6, HFD-RYGB = 9, and HFD-SHAM = 8.

2.3. Experiment 2 – Sucrose breakpoint and preference after RYGB or SHAM in CHOW-fed rats tested while nondeprived or food-deprived

2.3.1. Animal Subjects

Similar to Experiment 1, two cohorts of twenty rats were received 2 weeks apart. The rats that arrived earlier were ~2.5 months old (average body weight on arrival = 328 g) and were provided with CHOW only. The second cohort of rats were ~3 months of age (average body weight on arrival = 320 g) and given HFD and CHOW. During presurgical training, two rats were treated daily with carprofen (5mg/kg sc) for tissue inflammation associated with forepaw barbering, but this behavior was resolved and treatment discontinued prior to presurgical testing.

2.3.2. Progressive Ratio Behavioral Task and Intake Measures

Sucrose served as the reinforcer in the final training sessions (0.1–1.0 M) and during presurgical nondeprived testing (1.0 M; see Table 3). Sucrose (1.0 M) also was used during postsurgical nondeprived testing before and after the 2-bottle preference test and during food-deprived testing, but only in CHOW-fed rats, as the presurgical PR10 breakpoints of HFD rats were too low to merit further study (median of 10). Nine days after the completion of postsurgical PR10 nondeprived sucrose testing, the rats were presented for 96 h with 1.0 M sucrose and water in their home cages. One RYGB rat began drooling during the first block of intake testing, and so sucrose presentation and data collection were delayed a day for that individual subject. Thus, two to three days after 2-bottle testing, the rats were retested on a PR10 schedule for sucrose while nondeprived. Food-deprived PR10 testing with sucrose began 8 days after that, and three recovery days were scheduled between each of the tests due to difficulties previously observed when food-depriving RYGB rats [33].

2.3.3. Surgery and Recovery Procedures

Surgeries on all of the CHOW-fed rats were performed by one surgeon (C.M.M.) when the rats were, on average, 22 weeks old. No sooner than 1 h after recovery from anesthesia, the rats were presented with small amounts (~5–10g) of wet mash and a customized gel diet composed of whey powder (Jarrow formulas, unflavored; 26 g), corn starch (Clabber Girl; 133 g), corn oil (Winn-Dixie; 9 g), baby vitamins (Enfamil; 2 ml), gelatin (Knox; 32 g), and deionized water (~1000 ml). This gel diet was used in addition to wet mash in an attempt to minimize anastomosis breakages that led to RYGB mortality seen in Exp. 1. The rats were maintained on these diets for 7 days following surgery, after which CHOW was returned to the rats. Of the 20 CHOW rats, 12 underwent RYGB surgery and 8 underwent SHAM surgery. After RYGB, two rats were terminated from the study due to postsurgical complications. One other RYGB rat had a small amount of diarrhea that resolved after standard access to supplemental diets and analgesic treatment well prior to the start of postsurgical measures. No complications after SHAM surgery were seen. The final group sizes were CHOW-RYGB = 10 and CHOW-SHAM = 8.

2.4. Exp. 1 and 2 Data Analysis

The median PR breakpoints of the testing periods were used for analysis; nonparametric statistics were performed due to the fact that, by their nature, breakpoints are not distributed continuously. Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to assess: 1) presurgical differences in breakpoints between CHOW and HFD-fed rats and 2) postsurgical differences in breakpoints between surgical groups (RYGB vs. SHAM, in each diet or deprivation condition, when applicable). Friedman tests were used to assess: 1) pre-to-postsurgical changes in the breakpoints of the rats that completed both pre- and postsurgical testing phases, 2) breakpoints during testing prior to and following 2-bottle preference testing, and 3) breakpoints during testing while nondeprived and while food-deprived.

Preference scores for the nutritive stimuli during postsurgical 2-bottle testing were defined as the volume of Ensure, Intralipid, or sucrose ingested divided by the total fluid intake (stimulus + water). Preferences during two consecutive 24-h periods were averaged into a 48-h block to control for side biases. Differences in preference between the surgical groups (and diet groups, when applicable) across the two 48-h blocks were assessed via ANOVA. Changes in preference across testing blocks were assessed via paired t-tests within each group.

The percent change in body weight after surgery was assessed as the difference between the body weight of each rat measured on each day after surgery and that taken on the day prior to surgery divided by the latter value.

In all statistical comparisons, significance was defined as p ≤ 0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Experiment 1 – Ensure and Intralipid after RYGB or SHAM in CHOW and HFD-fed rats tested while nondeprived

3.1.1. Body Weight

By the start of postsurgical testing at least 17 days after surgery, RYGB rats had lost, on average, 13.5% body weight, and SHAM rats had gained, on average, 2.1% (the average body weights of each group were: CHOW-RYGB = 465 g; CHOW-SHAM = 569 g; HFD-RYGB = 565 g; HFD-SHAM = 657 g). There was no difference in the progression of percent body weight change from surgery as a result of maintenance diet (F(1,25)=0.113, p=0.740; all diet interactions p<0.15).

3.1.2. Progressive Ratio Breakpoint

3.1.2.1. Presurgical

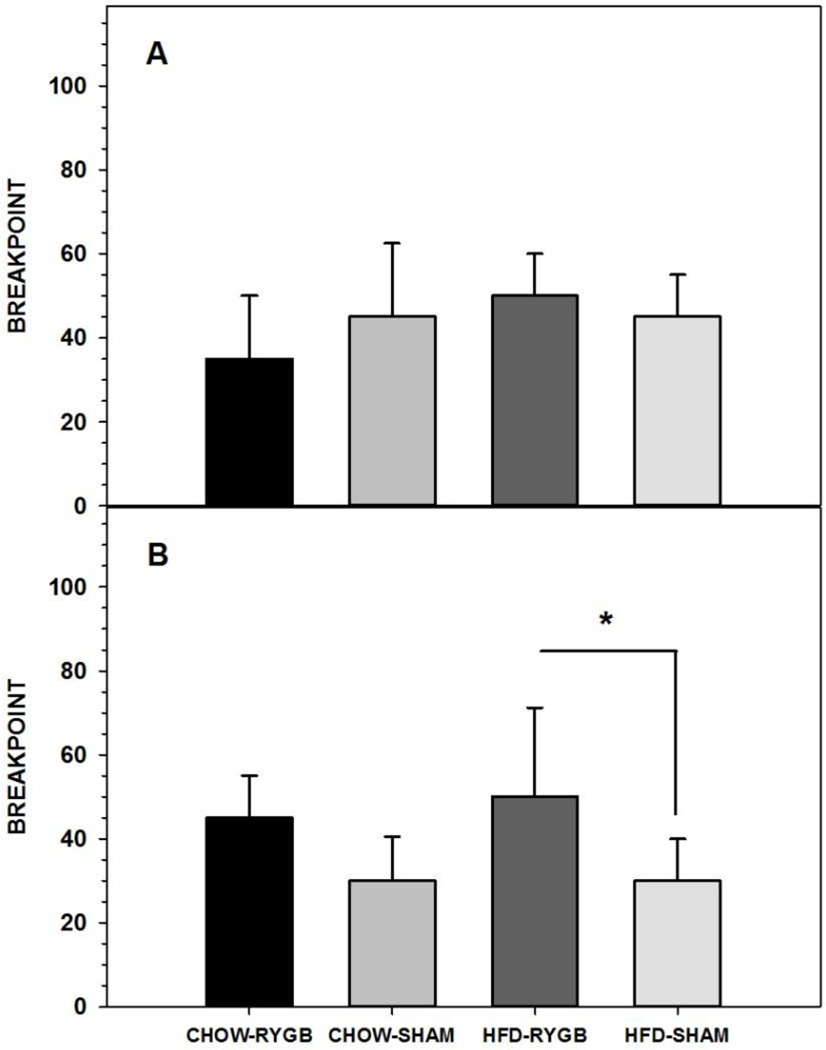

No differences were observed in breakpoint for Ensure when CHOW-fed (n=12) and HFD-fed (n=17) rats were tested nondeprived on a PR10 (Figure 1A, Table 4).

Figure 1.

Three-day median ± semi-interquartile range breakpoint of rats fed either a high-fat diet and standard laboratory chow (HFD) or standard laboratory chow alone (CHOW) before surgery (A) or after being given either Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (RYGB) or a sham operation (SHAM) (B) when performing for Ensure on a progressive ratio (PR) schedule. Rats that were given the HFD choice and that received RYGB had higher breakpoints than did HFD-SHAM rats. At no time did breakpoints differ based on maintenance diet. * represents p<0.05.

Table 4.

Nonparametric statistics comparing median 3-day breakpoints (BP) during operant testing on various progressive ratio (PR) schedules where milk-chocolate Ensure Plus (ENS) or 5% Intralipid (IL) served as the reinforcer between nondeprived rats given Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sham operations (RYGB vs. SHAM) and/or maintained on high-fat diet and standard chow or chow alone (HFD vs. CHOW).

| COMPARISON | GROUPS | TEST | STATISTIC |

|---|---|---|---|

| ENS PR10 BP - Presurgical | CHOW vs. HFD (across planned surgery groups) | Kruskal Wallis | H(1)=1.021, p=0.312 |

| CHOW-SHAM vs. HFD-SHAM | Kruskal Wallis | H(1)=0.017, p=0.896 | |

| ENS PR10 BP - Postsurgical | CHOW-RYGB vs CHOW-SHAM | Kruskal Wallis | H(1)=1.682, p=0.195 |

| HFD-RYGB vs. HFD-SHAM | Kruskal Wallis |

H(1)=4.658, p=0.031 RYGB > SHAM |

|

| CHOW-SHAM vs. HFD-SHAM | Kruskal Wallis | H(1)=0.073, p=0.788 | |

| CHOW -RYGB vs. HFD-RYGB | Kruskal Wallis | H(1)=0.445, p=0.505 | |

| ENS PR10 BP – Pre- to Postsurgical |

CHOW-RYGB | Friedman | χ2 (1)=2.667, p=0.102 |

| CHOW-SHAM | Friedman |

χ2(1)=4.000, p=0.046 PRE > POST |

|

| HFD-RYGB | Friedman | χ2(1)=0.500, p=0.480 | |

| HFD-SHAM | Friedman |

χ2(1)=6.000, p=0.014 PRE > POST |

|

| IL PR10 BP – Postsurgical | CHOW-RYGB vs CHOW-SHAM | Kruskal Wallis | H(1)=0.007, p=0.932 |

| HFD-RYGB vs. HFD-SHAM | Kruskal Wallis | H(1)= 1.743, p=0.187 | |

| CHOW-SHAM vs. HFD-SHAM | Kruskal Wallis | H(1)=0.073, p=0.788 | |

| CHOW -RYGB vs. HFD-RYGB | Kruskal Wallis | H(1)=0.178, p=0.673 | |

| IL PR3 BP – Postsurgical, prior to 2-bottle preference test |

CHOW-RYGB vs CHOW-SHAM | Kruskal Wallis | H(1)=0.554, p=0.457 |

| HFD-RYGB vs. HFD-SHAM | Kruskal Wallis |

H(1)=6.065, p=0.014 RYGB > SHAM |

|

| CHOW-SHAM vs. HFD-SHAM | Kruskal Wallis | H(1)=0.609, p=0.435 | |

| CHOW -RYGB vs. HFD-RYGB | Kruskal Wallis | H(1)=1.559, p=0.212 | |

| IL PR3 BP – Postsurgical, after 2-bottle preference test |

CHOW-RYGB vs CHOW-SHAM | Kruskal Wallis | H(1)=1.283, p=0.257 |

| HFD-RYGB vs. HFD-SHAM | Kruskal Wallis | H( 1)= 1.000, p=0.317 | |

| CHOW-SHAM vs. HFD-SHAM | Kruskal Wallis | H(1)=1.810, p=0.179 | |

| CHOW -RYGB vs. HFD-RYGB | Kruskal Wallis | H(1)=1.016, p=0.313 | |

| IL PR3 BP – Pre- to Post-2-bottle preference test |

CHOW-RYGB | Friedman | χ2(1)=1.000, p=0.317 |

| CHOW-SHAM | Friedman | χ2(1)=1.000, p=0.317 | |

| HFD-RYGB | Friedman | χ2(1)=3.571, p=0.059 | |

| HFD-SHAM | Friedman | χ2(1)=0.500, p=0.480 |

3.1.2.2. Postsurgical

3.1.2.2.1. Ensure

In contrast to our hypothesis, there was no decrease in breakpoint after RYGB in either diet group. In fact, HFD-fed RYGB rats displayed a significantly higher breakpoint for Ensure following RYGB than HFD-fed rats receiving sham surgery (Figure 1B, Table 4). It should be noted, though, that this difference may have primarily been driven by a decrease in the breakpoint of SHAM rats seen after compared with before surgery (Table 4), whereas the breakpoint of neither RYGB group changed across testing periods (Table 4). Similar to the presurgical comparison, the Ensure breakpoint of CHOW-SHAM and HFD-SHAM rats did not significantly differ postsurgically, nor did that of CHOW- and HFD-fed RYGB (Table 4).

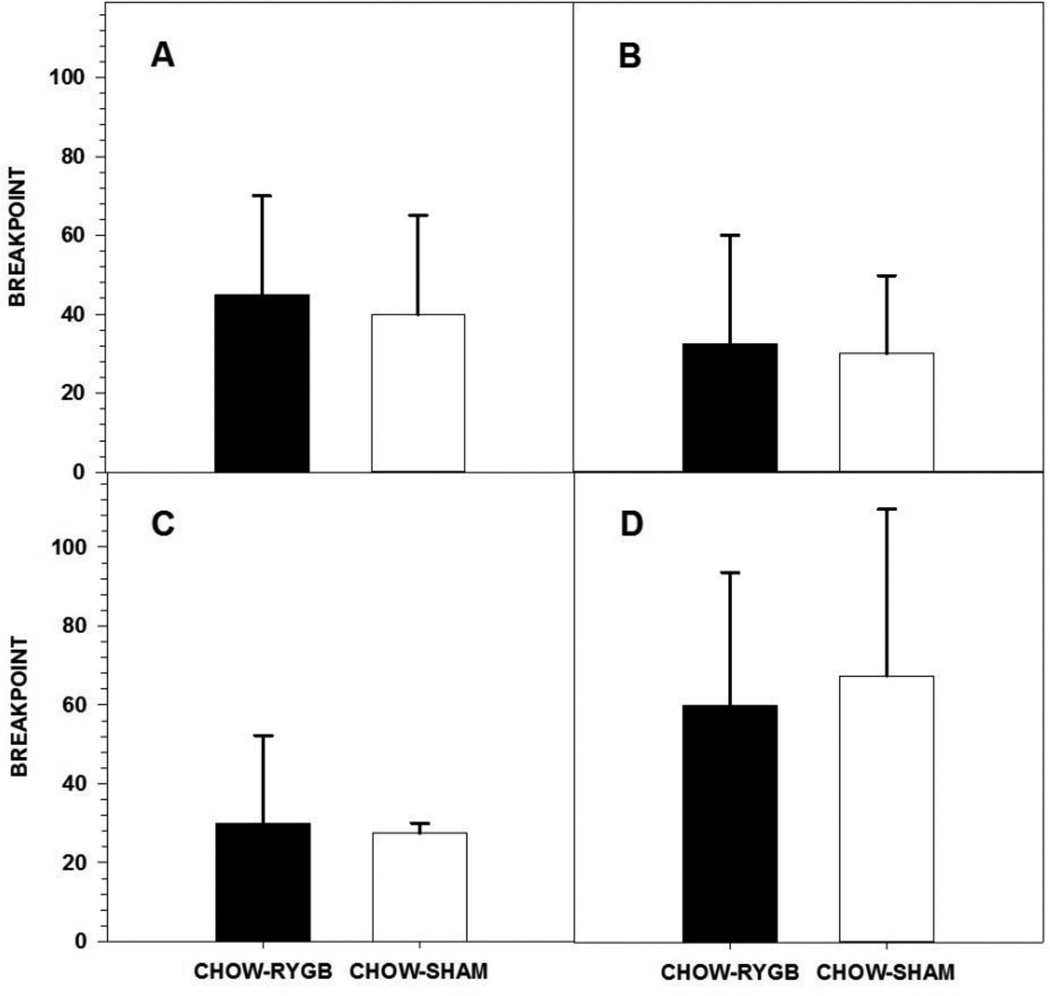

3.1.2.2.2. Intralipid

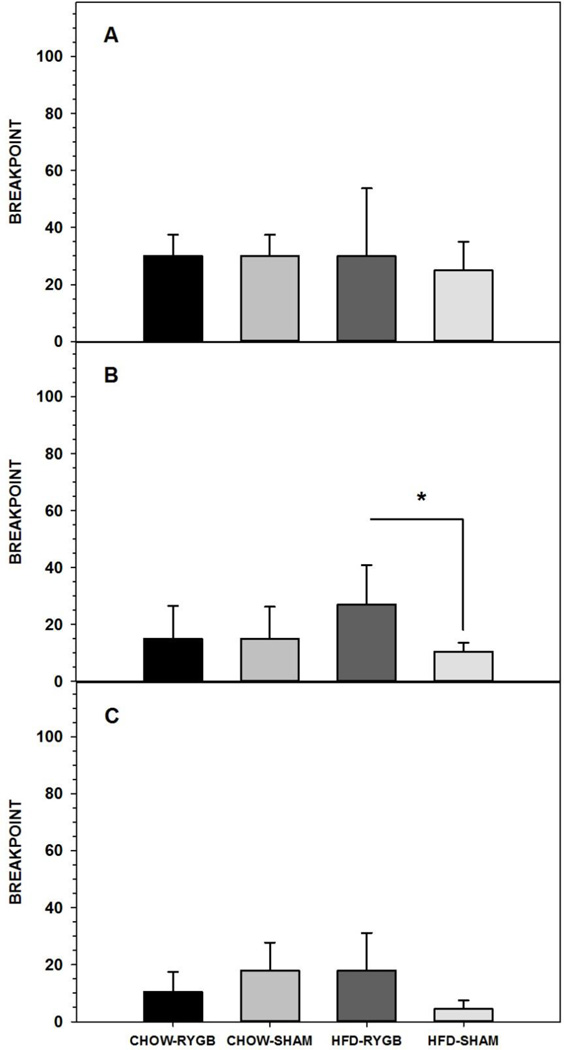

When the reinforcer in the PR10 task was switched from Ensure to IL, RYGB rats in both diet groups showed breakpoints similar to SHAM rats (Figure 2A, Table 4). When the ratio requirement was lowered to a PR3 schedule, HFD-RYGB rats had higher breakpoints than did HFD-SHAM rats (Figure 2B, Table 4). Following the IL vs. water 2-bottle preference test, the difference in breakpoint between surgical groups in the HFD-fed rats had a similar trend but was no longer significant (Figure 2C, Table 4). Maintenance diet did not influence breakpoint for IL as CHOW-SHAM rats and HFD-SHAM rats displayed a similar breakpoint on PR10 and PR3 for IL both before and after the 2-bottle preference test, as did HFD-RYGB and CHOW-RYGB rats (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Three-day median ± semi-interquartile range breakpoint of rats fed either a high-fat diet and standard laboratory chow (HFD) or standard laboratory chow alone (CHOW) and after being given either Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (RYGB) or a sham operation (SHAM) when performing for 5% Intralipid (IL) on a progressive ratio (PR) 10 (A) or 3 schedule either before (B) or after (C) a 96-h 2-bottle preference test (IL vs. water). Rats that were given the HFD choice and that received RYGB had higher breakpoints than did HFD-SHAM rats but only during PR3 testing prior to the 2-bottle preference test. At no time did breakpoints differ based on maintenance diet. * represents p<0.05.

3.1.3. Preference

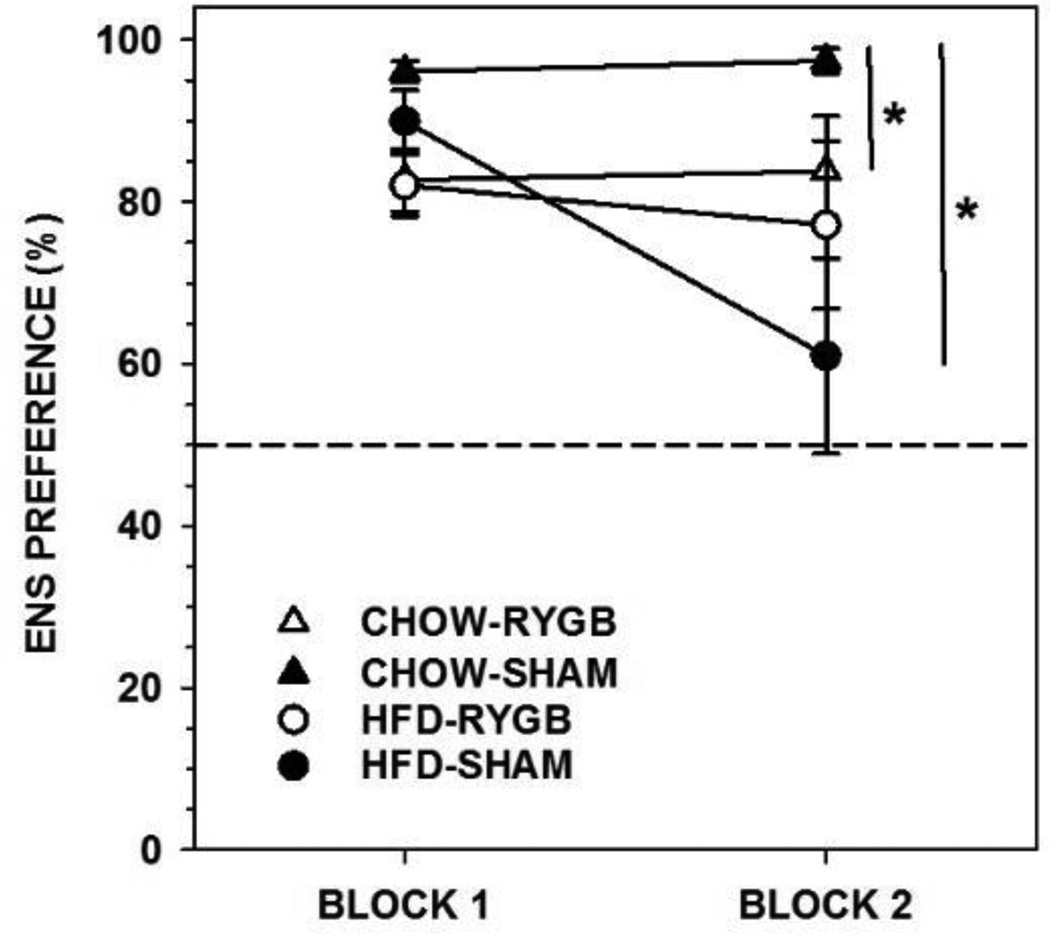

3.1.3.1. Ensure

Rats fed CHOW and given RYGB drank less Ensure (on average 44 and 45 ml per 24 h during each block, respectively) than did CHOW-SHAM (on average 88 and 98 ml) rats, as well as displaying less preference for Ensure (Figure 3, Table 5). However, both groups showed, on average, at least an 80% preference for Ensure over water. The intakes of HFD-fed rats did not differ as a function of RYGB (on average 41 and 37 ml) or SHAM (on average 59 and 40 ml) surgery, nor did Ensure preference (Figure 3, Table 5). CHOW-SHAM rats showed higher Ensure preference in the 2-bottle test than did HFD-SHAM rats (Figure 3; F(1,12)=6.222, p=0.028).

Figure 3.

Mean ± standard error percent preference for Ensure (ENS) during a 96-h 2-bottle preference test (ENS vs. water, divided in to two 48-h blocks) of rats fed either a high-fat diet and standard laboratory chow (HFD) or standard laboratory chow alone (CHOW) and given either Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (RYGB) or a sham operation (SHAM). Rats that received RYGB and were fed CHOW alone showed lower ENS preferences relative to CHOW-SHAM rats, but still maintained preferences greater than 50%. Further, the preference of both RYGB groups remained stable across blocks. Rats fed CHOW and given SHAM showed higher overall preferences of ENS than HFD-SHAM, but there was no such difference between CHOW-RYGB and HFD-RYGB rats. * represents p<0.05.

Table 5.

Parametric statistics comparing the percent preference for milk-chocolate Ensure Plus and 5% Intralipid during 96-h 2-bottle preference testing (taste stimulus vs. water; analyzed in two 48-h blocks) between nondeprived rats given Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sham operations (RYGB vs. SHAM) and maintained on either high-fat diet and CHOW (HFD) or CHOW alone.

| TEST | COMPARISON / GROUP |

ENSURE PREFERENCE | INTRALIPID PREFERENCE |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-way ANOVA | Diet | F(1,25)=6.272, p=0.019 | F(1,25)=1.827, p=0.189 |

| Surgery | F(1,25)=0.171, p=0.683 | F(1,25)=9.657, p=0.005 | |

| Diet × Surgery | F(1,25)=3.285, p=0.082 | F(1,25)=1.047, p=0.316 | |

| Block (condition) | F(1,25)=3.566, p=0.071 | F(1,25)=17.533, p<0.001 | |

| Block × Diet | F(1,25)=5.073, p=0.033 | F(1,25)=0.187, p=0.669 | |

| Block × Surgery | F(1,25)=1.779, p=0.194 | F(1,25)=4.807, p=0.038 | |

| Block × Diet × Surgery | F(1,25)=1.930, p=0.177 | F(1,25)=0.994, p=0.328 | |

| 2-way ANOVA - CHOW | Surgery | F(1,10)=7.458, p=0.021 | F(1,10)=11.088, p=0.008 |

| Block (condition) | F(1,10)=0.161, p=0.697 | F(1,10)=7.366, p=0.022 | |

| Block × Surgery | F(1,10)=0.004, p=0.952 | F(1,10)=3.511, p=0.090 | |

| 2-way ANOVA - HFD | Surgery | F(1,15)=0.799, p=0.385 | F(1,15)=2.132, p=0.165 |

| Block (condition) | F(1,15)=7.219, p=0.017 | F(1,15)=10.098, p=0.006 | |

| Block × Surgery | F(1,15)=3.122, p=0.098 | F(1,15)=1.024, p=0.328 | |

| Paired t-test - Blocks / Condition |

CHOW-RYGB | t(5)=−0.172, p=0.870 |

t(5)=2.595, p=0.049 BLOCK 1 > BLOCK 2 |

| CHOW-SHAM | t(5)=−1.434, p=0.211 | t(5)=0.898, p=0.410 | |

| HFD-RYGB | t(8)=1.122, p=0.294 |

t(8)=2.917, p=0.019 BLOCK 1 > BLOCK 2 |

|

| HFD-SHAM | t(7)=2.324, p=0.053 | t(7)=1.577, p=0.159 |

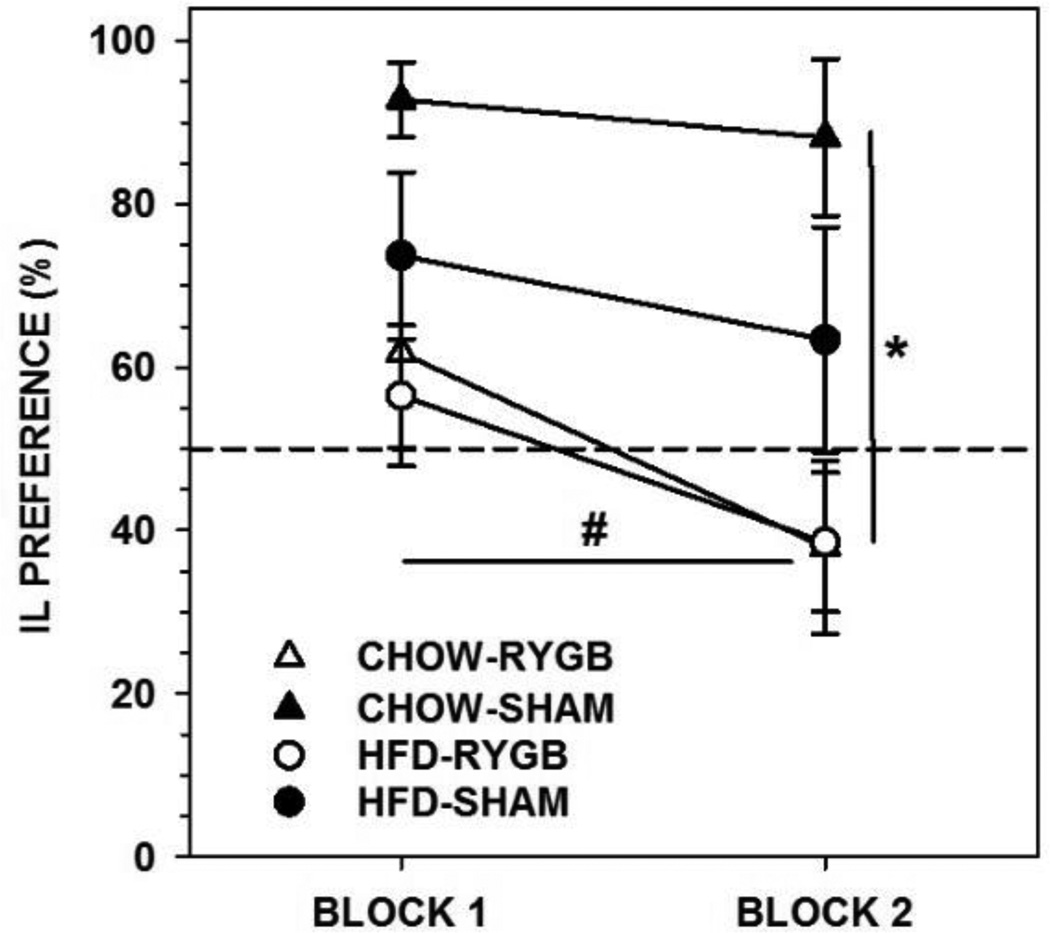

3.1.3.2. Intralipid

Overall, the RYGB rats displayed less preference for IL over water compared to SHAM rats (Figure 4, Table 5; CHOW-RYGB drank 22 and 12 ml, CHOW-SHAM drank 82 and 67 ml, HFD-RYGB drank 20 and 11 ml, and HFD-SHAM drank 35 and 33 ml per 24 h during each block, respectively). Importantly, the IL preference of RYGB rats in both diet groups significantly decreased across testing blocks while that of the SHAM groups remained stable (Figure 4, Table 5). Similar IL preferences were seen between CHOW-SHAM and HFD-SHAM rats (Figure 4; F(1,12)=2.363, p=0.150).

Figure 4.

Mean ± standard error percent preference for 5% Intralipid (IL) during a 96-h 2-bottle preference test (IL vs. water, divided in to two 48-h blocks) of rats fed either a high-fat diet and standard laboratory chow (HFD) or standard laboratory chow alone (CHOW) and given either Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (RYGB) or a sham operation (SHAM). Rats that received RYGB and were fed CHOW alone showed lower IL preferences relative to CHOW-SHAM rats (* represents p<0.05). Importantly, the preference of both RYGB groups decreased across blocks whereas the preferences of the SHAM groups remained stable (# represents p<0.05). There were no differences on IL preferences as a function of diet groups within surgery groups.

3.2. Experiment 2 – Sucrose and Intralipid after RYGB or SHAM in CHOW-fed rats tested while nondeprived or food-deprived

3.2.1. Body Weight

By the start of postsurgical testing at least 21 days after surgery, CHOW-RYGB rats had lost, on average, 3.1% body weight, and CHOW-SHAM rats had gained, on average, 5.2% (average body weights: CHOW-RYGB = 579 g; CHOW-SHAM = 582 g).

3.2.2. Progressive Ratio Breakpoint

3.2.2.1. Presurgical

Rats fed CHOW (n=20) had higher median breakpoints than rats fed HFD (n=20) when tested nondeprived on a PR10 schedule prior to any surgical manipulations (CHOW = 40 ± 20; HFD = 10 ± 9.5; Table 6). Since the breakpoints of HFD-fed rats were so low, these rats were removed from the study and underwent no surgical manipulations.

Table 6.

Nonparametric statistics comparing median 3-day breakpoints (BP) during operant testing on various progressive ratio (PR) schedules where 1.0 M sucrose (SUC) served as the reinforcer between nondeprived rats given Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sham operations (RYGB vs. SHAM) and/or maintained on high-fat diet and standard chow or chow alone (HFD vs. CHOW).

| COMPARISON | GROUPS | TEST | STATISTIC |

|---|---|---|---|

| SUC PR10 BP – Presurgical Nondeprived |

CHOW-RYGB vs. CHOW-SHAM | Kruskal Wallis | H(1)=0.018, p=0.893 |

| CHOW vs. HFD | Kruskal Wallis |

H(1)=5.35, p=0.021 CHOW > HFD |

|

| SUC PR10 BP – Postsurgical Nondeprived |

CHOW-RYGB vs CHOW-SHAM | Kruskal Wallis | H(1)=0.647, p=0.421 |

| SUC PR10 BP – Pre- to Postsurgical Nondeprived |

CHOW-RYGB | Friedman | χ2(1)=1.6, p=0.206 |

| CHOW-SHAM | Friedman | χ2(1)=1.286, p=0.257 | |

| SUC PR10 BP – Postsurgical nondeprived, after 2-bottle preference test |

CHOW-RYGB vs CHOW-SHAM | Kruskal Wallis | H(1)=0.345, p=0.557 |

| SUC PR10 BP – Pre- to Post-2-bottle preference test, nondeprived |

CHOW-RYGB | Friedman | χ2(1)=3.571, p=0.059 |

| CHOW-SHAM | Friedman | χ2(1)=3.571, p=0.059 | |

| SUC PR10 BP – Postsurgical food-deprived |

CHOW-RYGB vs CHOW-SHAM | Kruskal Wallis | H(1)=0.008, p=0.929 |

| SUC PR10 BP – Post-2-bottle preference test nondeprived vs. food- deprived |

CHOW-RYGB | Friedman |

χ2(1)=6.00, p=0.011 FD > ND |

| CHOW-SHAM | Friedman |

χ2(1)=8.000, p=0.005 FD > ND |

3.2.2.2. Postsurgical

There was no difference in breakpoint between CHOW rats that received RYGB or SHAM while tested nondeprived pre- or postsurgically or either before or after 2-bottle testing (Figure 5; Table 6). The breakpoints before versus after surgery did not differ in either the SHAM or RYGB groups (p>0.2). Likewise, there was no difference between the surgical groups when the rats were tested while food-deprived (Figure 5D, Table 6), but, overall, food-deprivation increased breakpoints in both surgical groups when compared to nondeprived testing after the 2-bottle preference test (p<0.015).

Figure 5.

Two to three-day median ± semi-interquartile range breakpoint of rats fed standard laboratory chow (CHOW) when performing for 1.0 M sucrose (SUC) on a progressive ratio (PR) schedule prior to (A) or after either Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) or sham (SHAM) surgery (B). At no time did breakpoint differ between surgical groups. When the rats were tested while food-deprived (D), their breakpoints were greater than when they were tested nondeprived (C).

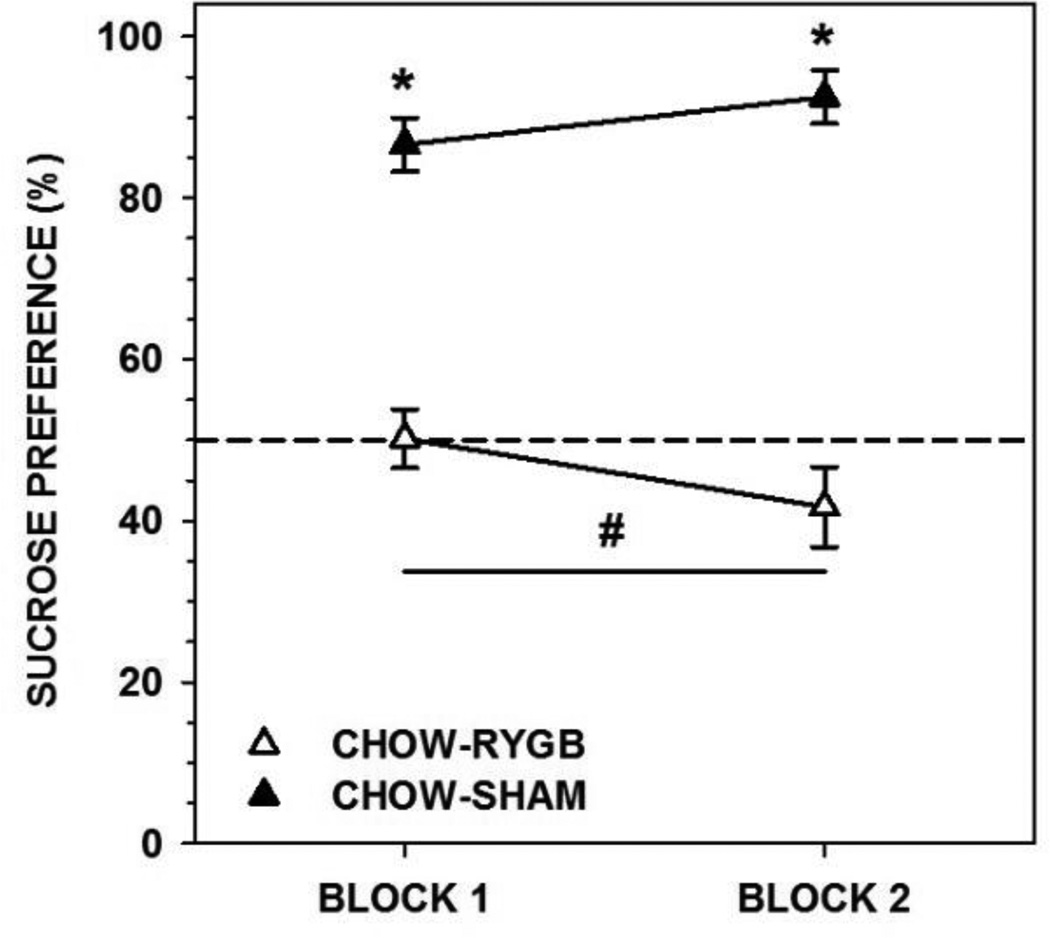

3.2.3. Preference

Rats fed CHOW and given RYGB drank less sucrose (on average 27 and 23 ml per 24 h during each block, respectively) than did CHOW-SHAM rats (on average 50 and 57 ml), as well as displaying less preference for sucrose (Figure 6, Table 7); indeed, the majority of RYGB rats displayed indifference. Further, the intakes of the RYGB, but not SHAM rats decreased across the 48-h blocks (Table 7).

Figure 6.

Mean ± standard error percent preference for 1.0 M sucrose (SUC) during a 96-h 2-bottle preference test (SUC vs. water, divided in to two 48-h blocks) of rats fed standard laboratory chow and given either Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (RYGB) or a sham operation (SHAM). Rats that received RYGB showed lower SUC preferences relative to SHAM rats on both blocks of testing (* represents p<0.05). Importantly, the preference of both RYGB groups decreased across blocks whereas the preferences of the SHAM groups remained stable (# represents p<0.05).

Table 7.

Parametric statistics comparing the percent preference for 1.0 M sucrose during 96-h 2-bottle preference testing (sucrose vs. water; analyzed in two 48-h blocks) between nondeprived rats given Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or sham operations (RYGB vs. SHAM) and maintained on chow.

| TEST | COMPARISON / GROUP |

SUCROSE PREFERENCE |

|---|---|---|

| 2-way ANOVA - CHOW | Surgery | F(1,16)=61.709, p<0.001 |

| Block (condition) | F(1,16)=0.365, p=0.554 | |

| Block × Surgery | F(1,16)=10.818, p=0.005 | |

| Paired t-test - Blocks / Condition |

CHOW-RYGB |

t(9)=3.568, p=0.006 BLOCK 1 > BLOCK 2 |

| CHOW-SHAM | t(7)=−1.509, p=0.175 |

4. DISCUSSION

In this series of studies, we have shown that the amount of work in which rats engage to receive caloric sugar- and/or fat-containing fluids does not decrease following RYGB surgery. In fact, under some conditions, rats worked even harder for Ensure and IL after RYGB compared with sham-operated rats. These results suggest that RYGB does not dampen the willingness of the animals to work for the fluids tested. By virtue of the small volumes of each “reward” (~75 µl), the progressive ratio task minimizes postingestive consequences – positive or negative – and, thus, the rats in these studies were presumably responding on the basis of the positive orosensory properties of the stimuli serving as reinforcers.

In our PR10 task, the median breakpoint of nondeprived rats for Ensure, Intralipid, and sucrose was around 40, meaning that, on average, rats were required to lick a dry spout 101 times to receive less than 0.4 ml (e.g., 0.6 kcal of Ensure). This level of work is similar to breakpoints we have previously reported in nondeprived rats working on a PR3 for 1.0 M sucrose despite a different apparatus and training paradigm [28]. This cumulative amount of work and breakpoint also falls in the middle of previously reported values produced by nondeprived rats, with some higher [e.g., 34] and some lower [e.g., 27, 35], though it should be noted that methodological differences including, rat strain, sex, and reinforcer concentration and volume make direct quantitative comparisons difficult. In Experiment 2, we validated our PR task by showing that the breakpoint could be increased (i.e., from approximately 35 to 60) by conditions classically considered motivators of appetitive behavior – e.g., food-deprivation. While higher breakpoints and/or mean cumulative responses have been observed in other studies [e.g., 31, 36, 37] the ones reported in the present study are still consistent with other reports [e.g., 30, 38]. While it was somewhat surprising that breakpoints for Ensure decreased from presurgical to postsurgical conditions in the SHAM rats from both diet groups, this could potentially be attributed to the long span of time between test phases (at least 3 weeks) and that postsurgical testing was not immediately preceded by training.

That rats given RYGB did not work less for palatable fluids was a somewhat unexpected result since human patients work less for a fatty and sugary snack following RYGB [26]. We had hypothesized that the decreased PR breakpoint seen in humans would be recapitulated in a rat model, but many differences between the studies could underlie the disparity in results. The most obvious is the species difference, especially considering that human RYGB patients are very motivated to lose weight and are counseled that they should avoid eating candy. In contrast, rats are unencumbered by these social and cognitive demands and are likely behaving purely based on the subjective value of the reinforcers. The time of testing relative to surgery may also be critical; the patients were tested in the steepest weight loss phase 8 weeks after surgery while the rats display a negative energy balance at ~2 weeks and were tested in the weight stable phase at least ~2.5–3 weeks after surgery. Other procedural differences include the reinforcer itself; in the human study a solid candy was used rather than the liquids obtained by the rats in the present study. Importantly, the candy had a higher caloric density and proportionally greater fat and sugar compositions than any of the tastants used here (M&M Crispy = 4.92 kcal/g; 45% calories from fat, 44% from sugar).

That in some cases here RYGB in rats increased appetitive responsiveness to caloric fluids was not completely unexpected. We had shown previously that in a brief-access taste test CHOW-fed rats given RYGB initiated 2–3 times as many trials across concentrations of sucrose compared with that taken by sham-operated rats, even when the rats were in a nondeprived state (33). This result implies that RYGB in CHOW-fed rats increased the drive to initiate licking on a spout that delivers sucrose, but we did not see that in the present report when using the PR task to test the willingness of rats to work for 1.0 M sucrose. The PR task is a much purer assessment of appetitive behavior because it quantifies responses when the animal is not in contact with the reinforcer while at the same time minimizing stimulus exposure and intake, which in turn, limits postingestive stimulation. The rats in the brief-access task across all trials in the session received, on average, a total of 13 ml of sucrose solution amounting to ~6 kcal, whereas the nondeprived rats in this study, at most, consumed less than 1 ml of 1.0 M sucrose, amounting to 5-fold fewer calories. Regardless, the rats in the present study responded to sucrose in the 2-bottle test in a manner similar to that previously seen [e.g., 22].

In a different assessment of appetitive behavior, HFD-fed rats given RYGB using a different surgical model displayed faster completion speeds than sham-operated HFD-fed rats in a runway task, at least at the beginning of training [20]. Interestingly, Shin et al. [20] reported that during the initial postsurgical training sessions, both HFD-fed RYGB-operated rats and CHOW-fed controls had similar completion speeds that were higher than HFD-fed sham-operated rats. However, by the tenth postsurgical training session, the completion speed of the three groups was equally high. Using the PR task in Exp. 1, we did not find performance differences between HFD-SHAM and CHOW-SHAM rats, nor did we find differences between HFD-RYGB or CHOW-RYGB, suggesting that the diet on which the rats are maintained may have little influence on PR performance, at least for these stimuli. Interestingly, when 1.0 M sucrose served as the reinforcer, HFD-fed rats in either surgical condition responded much less avidly than CHOW-fed rats, suggesting that sucrose alone is not as motivating after chronic consumption of a high-fat diet, a finding consistent with some [e.g., 39, 40] but not all [e.g., 41–43] reports in the literature. While the fat content of the diet may serve as the important factor, it should be noted that this HFD contains a higher proportion of maltodextrin than CHOW, despite having less simple sugars. It is also worth noting that rats that have received vertical sleeve gastrectomy, a different form of bariatric surgery, do not display postsurgical differences from sham-operated controls in the breakpoint for oil or sucrose reinforcers while tested either nondeprived or in a food-deprived state [44]. Collectively, the increase in brief-access trial taking, faster runway completion speeds, and, at times, higher breakpoints in the present PR task by rats after RYGB suggests that the drive to approach and begin to ingest small amounts of palatable foods and fluids is not blunted by RYGB.

The findings that RYGB does not dampen the willingness of rats to work for sweet and/or fat-containing fluids seem at odds with RYGB patients who report less overall desire to consume foods and beverages that contain a large proportion of their calories from fat. However, although after RYGB rats do not show blunted drive for palatable liquids in short-term tests, in the current study we showed that, in most situations, RYGB rats displayed lower preferences for Ensure, IL, and sucrose compared to SHAM rats in long-term tests. This is similar to the findings reported by others [18, 19, 22, 23] in which rats given RYGB drank less of and showed blunted preferences for sucrose or Ensure, respectively, compared to sham-operated rats. These results suggest that preferences for proportionally higher sugar- and fat-containing fluids are diminished following RYGB, but that these preference shifts manifest only after some threshold experience with the postingestive effects of the nutritive stimuli.

Importantly, though, despite blunted preferences for Ensure, IL, HFD, and sucrose, most of the RYGB rats still consumed at least some of the palatable calorie sources. This is similar to a previous report showing that an oral gavage of 1 ml of corn oil is sufficient to reduce intake of a saccharin solution with which the corn oil was paired [9]. In that study, although the corn oil gavage did decrease acceptability of the saccharin solution in RYGB but not SHAM rats, it was not nearly as effective as injection of LiCl, one of the standard malaise-inducing unconditioned stimuli used in taste aversion studies. Instead, gavage-fed RYGB rats still consumed some saccharin (~4 ml, ~40% of fluid intake), albeit less than SHAM controls or their saline-gavaged counterparts (~10 ml, 90% of fluid intake). These results are in line with our conclusion that RYGB does not cause animals to completely reject fat (or normally preferred flavors paired with fat), but rather leads to a limitation of the intake of certain foods after experience. Thus, it appears that the ingestion of large amounts of these calorie sources after RYGB does not result in aversion and total avoidance of these food and fluids. Rather, rats appear to limit their intake of fat and sugar, but continue to ingest them.

Further, while the IL and sucrose preferences of RYGB rats decreased across testing blocks, this did not affect breakpoints in subsequent testing. This suggests that changes in intake of a sweet or fatty fluid require some duration of exposure, and that changes in food selection after RYGB represent learned adjustments in the intake of certain food items rather than an immediate alteration of their orosensory-based properties and thus reinforcement value. Of course, these are not necessarily mutually exclusive mechanisms. For example, Bueter et al. [22] has shown that taste sensitivity for perithreshold sucrose solutions increases in humans after RYGB, but this did not coincide with a change in ratings of ideal sweetness.

Overall, in the current study, we have provided evidence that RYGB in rats does not reduce PR performance for the reinforcing characteristics of small volumes of palatable sugar and/or fat-containing liquid stimuli. Indeed, in some cases, rats after RYGB might find these fluids more reinforcing compared to SHAM rats. Despite this lack of blunted motivation as measured by the PR task, RYGB rats typically display lower preferences for fat and sugar solutions in long-term tests, and under some conditions, their preference decreases further with increased exposure, but, importantly, they continue to ingest nontrivial amounts of these stimuli. Thus, on the whole, it is difficult to argue that rats form conditioned taste aversions to fat and sugar stimuli after RYGB in which the palatability and incentive salience of these stimuli has decreased. One possibility is that there is a selective decrease over time in the satiation threshold for simple sugars and fats. Alternatively, these results implicate a process more akin to conditioned avoidance in which, after RYGB, rats will limit their intake of sugary or fatty fluids, potentially to the minimize potential negative visceral consequences of their ingestion [see 45, 46], but will not shun them completely and are still motivated to work for access to them in small quantities.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) decreases intake of calorically dense food by rats.

Control rats show greater preferences for sweet and/or fatty fluids than RYGB rats.

After RYGB, rats do not work less than controls for sugary and/or fatty fluids.

RYGB in rats does not decrease the reinforcing properties of sugar or fat taste.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH R21-DC012751 to ACS. ClR is supported by Science Foundation Ireland ref 12/YI/B2480.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Portions of these data were presented at the April 2014 meeting of the Association for Chemoreception Sciences and will appear in abstract form in Chemical Senses.

REFERENCES

- 1.O’Brien PE. Bariatric surgery: mechanisms, indications and outcomes. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25(8):1358–1365. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sjöström L, Narbro K, Sjöström CD, Karason K, Larsson B, Wedel H, Lystig T, Sullivan M, Bouchard C, Carlsson B, Bengtsson C, Dahlgren S, Gummesson A, Jacobson P, Karlsson J, Lindroos AK, Lönroth H, Näslund I, Olbers T, Stenlöf K, Torgerson J, Agren G, Carlsson LM Swedish Obese Subjects Study. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(8):741–752. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tadross JA, le Roux CW. The mechanisms of weight loss after bariatric surgery. Int J Obes. 2009;33(S1):S28–S32. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brolin RE, Robertson LB, Kenler HA, Cody RP. Weight loss and dietary intake after vertical banded gastroplasty and roux-en-y gastric bypass. An Surg. 1994;220(6):782–790. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199412000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown EK, Settle EA, Van Rij AM. Food intake patterns of gastric bypass patients. J Am Diet Assoc. 1982;80(5):437–443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kenler HA, Brolin RE, Cody RP. Changes in eating behavior after horizontal gastroplasty and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;52(1):87–92. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/52.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kruseman M, Leimgruber A, Zumbach F, Golay A. Dietary, weight, and psychological changes among patients with obesity, 8 years after gastric bypass. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(4):527–534. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laurenius A, Larsson I, Melanson KJ, Lindroos AK, Lonrth H, Bosaeus I, Olbers T. Decreased energy density and changes in food selection following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67(2):168–173. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2012.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.le Roux CW, Bueter M, Theis N, Werling M, Ashradian H, Lowenstein C, Athanasiou T, Bloom SR, Spector AC, Olbers T, Lutz TA. Gastric bypass reduces fat intake and preference. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;301(4):R1057–R1066. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00139.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugerman HJ, Starkey JV, Birkenhauser R. A randomized prospective trial of gastric bypass versus vertical banded gastroplasty for morbid obesity and their effects on sweets versus non-sweets eaters. Ann Surg. 1987;205(6):613–622. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198706000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schoeller DA. Limitations in the assessment of dietary energy intake by self-report. Metabolism. 1995;44:18–22. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(95)90204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hills RJ, Davies PS. The validity of self-reported energy intake as determined using the doubly labeled water technique. Br J Nutr. 2001;85:415–430. doi: 10.1079/bjn2000281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trabulsi J, Schoeller DA. Evaluation of dietary assessment instruments against doubly labeled water, a biomarker of habitual energy intake. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;281 doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.281.5.E891. E891-E8911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schoeller DA. Validation of habitual energy intake. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:883–888. doi: 10.1079/PHN2002378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Livingstone MB, Black AE. Markers of the validity of reported energy intake. J Nutr. 2003;133(Suppl 3):895–920. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.3.895S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathes CM, Spector AC. Food selection and taste changes in humans after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a direct-measures approach. Physiol Behav. 2012;107(4):476–483. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bueter M, Abegg K, Seyfried F, Lutz TA, le Roux CW. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in rats. J Vis Exp. 2012;64:e3940. doi: 10.3791/3940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seyfried F, Miras AD, Bueter M, Prechtl CG, Spector AC, le Roux CW. Effects of preoperative exposure to a high-fat versus a low-fat diet on ingestive behavior after gastric bypass surgery in rats. Surg Endos. 2013;27(11):4192–4201. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3020-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng H, Shin AC, Lenard NR, Townsend RL, Patterson LM, Sigalet DL, Berthoud HR. Meal patterns, satiety, and food choice in a rat model of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;297(5):R1273–R1282. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00343.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin AC, Zheng H, Pistell PJ, Berthoud HR. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery changes food reward in rats. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011;35(5):642–651. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saeidi N, Nestoridi E, Kucharczyk J, Uygun MK, Yarmush ML, Stylopoulos N. Sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass exhibit differential effects on food preferences, nutrient absorbtion and energy expenditure in rats. Int J Obes. 2012;36(11):1396–1402. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bueter M, Miras AD, Chichger H, Fenske W, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR, Unwin RJ, Lutz TA, Spector AC, le Roux CW. Alterations of sucrose preference after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Physiol Behav. 2011;104(5):709–721. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chelikani PK, Shah IH, Taqi E, Sigalet DL, Koopmans HH. Comparison of the effects of Rpoux-en-Y gastric bypass and ileal transposition surgeries on food intake, body weight, and circulating peptide YY concentrations in rats. Obes Surg. 2010;20(9):1281–1288. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith GP. The direct and indirect controls of meal size. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1996;20(1):41–46. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(95)00038-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hodos W. Progressive ratio as a measure of reward strength. Science. 1961;134(3483):943–944. doi: 10.1126/science.134.3483.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miras AD, Jackson RN, Jackson SN, Goldstone AP, Olbers T, Hackenberg T, Spector AC, le Roux CW. Gastric bypass surgery for obesity decreases the reward value of a sweet-fat stimulus as assessed in a progressive ratio task. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96(3):467–473. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.036921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hajnal A, Acharya NK, Grigson PS, Cosava M, Twining RC. Obese OLETF rats exhibit increased operant performance for palatable sucrose solutions and differential sensitivity to D2 receptor antagonism. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R1846–R1854. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00461.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathes CM, Gregson JR, Spector AC. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor paroxetine decreases breakpoint of rats engaging in a progressive ratio licking task for sucrose and quinine solutions. Chem Sens. 2013;38(3):211–220. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjs096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGregor IS, Saharov T, Hunt GE, Topple AN. Beer consumption in rats: the influence of ethanol content, food deprivation, and cocaine. Alcohol. 1999;17:47–56. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(98)00033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reilly S. Reinforcement value of gustatory stimuli determined by progressive ratio performance. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1999;63(2):301–311. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sclafani A, Ackroff K. Reinforcement value of sucrose measures by progressive ratio operant licking in the rat. Physiol Behav. 2002;79:663–670. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith JC. The history of the “Davis Rig”. Appetite. 2001;36(1):93–98. doi: 10.1006/appe.2000.0372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mathes CM, Bueter M, Smith KR, Lutz TA, le Roux CW, Spector AC. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in rats increases sucrose taste-related motivated behavior independent of pharmacological GLP-1 receptor modulation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;302(6):R751–R767. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00214.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lacy RT, Hord LL, Morgan AJ, Harrod SB. Intravenous gestational nicotine exposure results in increased motivation for sucrose reward in adult rat offspring. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;124(3):299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kosten TA. Pharmacologically targeting the P2rx4 gene on maintenance and reinstatement of alcohol self-administration in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;98(4):533–538. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olarte-Sanchez CM, Valencia-Torres L, Cassaday HJ, Bradshaw CM, Szabadi E. Effects of SKF-83566 and haloperidol on performance on progressive ratio schedules maintained by sucrose and corn oil reinforcement: quantitative analysis using a new model derived from the Mathematical Principles of Reinforcement (MPR) Psychopharmacology. 2013;230(4):617–630. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3189-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liang NC, Freet CS, Grigson PS, Norgran R. Pontine and thalamic influences on fluid rewards: I. Operant responding for sucrose and corn oil. Physiol Behav. 2012;105(2):576–588. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brianna Sheppard A, Gross SC, Pavelka SA, Hall MJ, Palmatier MI. Caffeine increases the motivation to obtain non-drug reinforcers in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;124(3):216–222. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davis JF, Tracy AL, Schurdak JD, Tschop MH, Lipton JW, Clegg DJ, Benoit SC. Exposure to elevated levels of dietary fat attenuates psychostimulant reward and mesolimbic dopamine turnover in the rat. Behav Neurosci. 2008;122(6):1257–1263. doi: 10.1037/a0013111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Finger BC, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Diet-induced obesity blunts the behavioural effects of ghrelin: studies in a mouse progressive ratio task. Psychopharmacol. 2012;220(1):173–181. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2468-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Figlewicz DP, Bennett JL, Naleid AM, Davis C, Grimm JW. Intraventricular insulin and leptin decrease sucrose self-administration in rats. Physiol Behav. 2006;89(4):611–616. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.la Fluer SE, Vanderschuren LJ, Luijendijk MC, Kloeze BM, Tiesjema B, Adan RA. A reciprocal interaction between food-motivated behavior and diet-induced obesity. Int J Obes. 2007;31(8):1286–1294. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Figlewicz DP, Jay JL, Acheson MA, Magrisso IJ, West CH, Zayosh A, Benoit SC, Davis JF. Moderate high fat diet increases sucrose self-administration in young rats. Appetite. 2013;61(1):19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson-Perez HE, Chambers AP, Sandoval DA, Stefater MA, Woods SC, Benoit SC, Seeley RJ. The effect of vertical sleeve gastrectomy on food choice in rats. Int J Obes. 2013;37(2):288–295. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pelchat ML, Grill HJ, Rozin P, Jacobs J. Quality of acquired responses to tates by Rattus norvegicus dependes on type of associated discomfort. J Comp Psychol. 1983;97:140–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parker LA. Taste avoidance and taste aversion: evidence for two different processes. Learn Behav. 2003;31:165–172. doi: 10.3758/bf03195979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]