Abstract

Adult stem cells are essential for tissue homeostasis and wound repair. Their proliferative capacity must be tightly regulated to prevent the emergence of unwanted and potentially dangerous cells, such as cancer cells. We found that mice deficient for the proapoptotic Sept4/ARTS gene have elevated numbers of hair follicle stem cells (HFSCs) that are protected against apoptosis. Sept4/ARTS−/− mice display marked improvement in wound healing and regeneration of hair follicles. These phenotypes depend on HFSCs, as indicated by lineage tracing. Inactivation of XIAP, a direct target of ARTS, abrogated these phenotypes and impaired wound healing. Our results indicate that apoptosis plays an important role in regulating stem cell–dependent regeneration and suggest that this pathway may be a target for regenerative medicine.

The ability of stem cells (SCs) to self-renew and differentiate enables them to replace cells that die during tissue homeostasis or upon injury. Elevated SC numbers might be desirable, at least transiently, to enhance tissue repair (1, 2). However, a large SC pool may potentially increase the risk of cancer (3).

One major mechanism that eliminates undesired and dangerous cells is apoptosis (4). Relatively little is known about the role of apoptosis in controlling SC numbers and its possible effect on SC-dependent regeneration. Apoptosis is executed by caspases that are negatively regulated by IAPs (inhibitor of apoptosis proteins) (5, 6). The best-studied mammalian IAP is XIAP (7). In cells destined to die, IAPs are inactivated by specific antagonists (8, 9). One mammalian IAP antagonist is ARTS, a splice variant of the mammalian gene Septin4 (Sept4) (10, 11). Deletion of the Sept4/ARTS gene results in increased numbers of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and elevated XIAP levels. This causes increased apoptotic resistance and accelerated tumor development (12). Here, we report crucial roles of XIAP and Sept4/ARTS in regulating hair follicle stem cell (HFSC) apoptosis and show that apoptotic alterations have profound consequences for wound healing and regeneration.

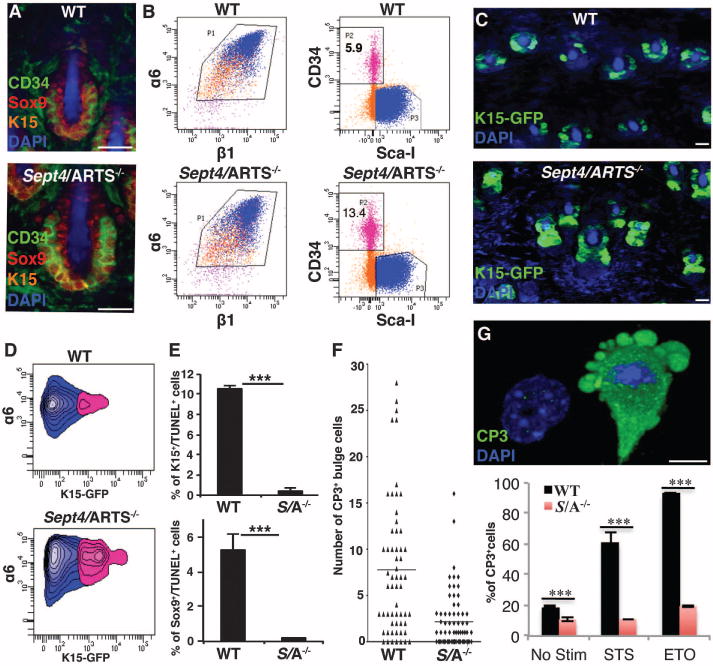

Hair follicles cycle between phases of growth (anagen), destruction (catagen), and rest (telogen). This process requires distinct populations of HFSCs that reside within the bulge (13–16). ARTS was the only Sept4 isoform detected in HFSCs (fig. S1, A to C). To investigate the consequences of ARTS deficiency, we examined bulge HFSCs with specific bulge markers (CD34 and K15) as well as Sox9, which, depending on the hair follicle phase, labels HFSCs and/or progeny. Although Sept4/ARTS−/− hair follicles had bulges with overall normal morphology, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) revealed that within the α6+β1+ population of skin epithelial progenitors there were more than twice as many CD34+ cells in Sept4/ARTS−/− as in the wild type (Fig. 1, A and B, and fig. S1D). Similarly, for the Tg(Krt1–15-EGFP)2Cot/J reporter mouse, which specifically marks K15+ bulge and hair germ cells (17), the numbers of K15-GFP+α6hi cells were elevated when backskin hair follicles lacked Sept4/ARTS (Fig. 1, C and D).

Fig. 1. Sept4/ARTS−/− mice display HFSCs that are resistant to apoptosis.

(A) Dorsal whole mounts (DWMs) stained for CD34, K15, Sox9, and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) at P21. WT, wild type. (B) FACS analysis of dorsal skins assessing the percentage of bulge HFSCs within control (WT) and Sept4/ARTS−/− skins. Equivalent numbers of FACS-purified α6+β1+ progenitors were resorted for CD34+Sca1− (pink, α6+β1+CD34+SCa1−;blue, α6+β1+CD34−SCa+; orange, α6+β1+CD34−SCa1−). Data shown are from four mice combined and sorted together. Experiments were repeated four times independently (n ≥ 11, P < 0.001). (C) DWM images of control and Sept4/ARTS−/−:Tg(Krt1–15-EGFP)2Cot/J reporter skins. (D) FACS analyses of α6+K15+ cells from control and Sept4/ARTS−/−:Tg(Krt1–15-EGFP)2Cot/J reporter skins. (E) Quantifications of K15+TUNEL+ and Sox9+TUNEL+ cells during first catagen (P16). S/A−/− denotes Sept4/ARTS−/−. (F) Quantifications of CD34+CP3+ HFSCs in control and Sept4/ARTS−/− tailskin hair follicles. Horizontal line defines average. (G) Top: Z-stack of control cultured HFSCs undergoing apoptosis in vitro. Bottom: Percentage of sorted HFSCs (CD34+Sca1−) placed into culture that are CP3+ with and without staurosporine (STS) and etoposide (ETO) treatment. Scale bars, 100 μm (A), 20 μm (C), 10 μm (G). ***P < 0.001.

ARTS-dependent differences were even more striking in tailskin (fig. S2). At 8 weeks of age, Sept4/ARTS−/− tailskin hair follicles displayed an expanded epithelial strand populated by K15+ and Sox9+ cells (fig. S2). In normal backskin follicles, this strand forms during mid- to late catagen phase, when most matrix cells have died and only a small number of outer root sheath (ORS) cells remain (18). Because ARTS is a proapoptotic protein, the elongated epithelial strand suggested that more ORS cells survive catagen when ARTS is absent.

To test whether ARTS affects the survival of skin progenitors, we cultured CD34+Sca1− and CD34−Sca1+ keratinocytes from telogen-phase backskins and evaluated their colony-forming efficiency (≥4 cells per colony) and cell number. Sept4/ARTS−/− HFSCs generated ~2.5 times as many colonies as wild-type HFSCs (fig. S3A). Moreover, the number of cells within these colonies was significantly higher (fig. S3C). By contrast, epidermal keratinocytes were unaffected (fig. S3, B and D). We also examined the proliferation rates of HFSCs and of other skin cells, and found no effect of Sept4/ARTS (fig. S3, E to K). These findings suggest that loss of ARTS protects HFSCs against apoptosis.

In wild-type catagen follicles, a new bulge is formed from CD34+ HFSCs along the upper ORS, whereas surviving CD34− ORS cells form the new hair germ (18). Both wild-type and Sept4/ARTS−/− hair follicles formed new bulges (fig. S4, A and B). Apoptotic cells are rarely seen in telogen or anagen but are prevalent in catagen (19). Therefore, we surmised that the pronounced epithelial strand seen in Sept4/ARTS−/− hair follicles might reflect enhanced apoptotic resistance of HFSCs. To test this hypothesis, we examined apoptosis in the first catagen phase [postnatal day 16 (P16)] and found a striking decrease of cell death in Sept4/ARTS−/− mice (Fig. 1E and fig. S4, C and D). These results suggest that in Sept4/ARTS−/− mice, more ORS HFSCs are spared during catagen, thereby yielding a larger HFSC pool. Because there is only a single bulge at this stage, it also explains why the bulge region appeared larger in P21 Sept4/ARTS−/− hair follicles (Fig. 1A).

In contrast to backskin, tailskin had CP3+ (cleaved caspase3+) cells in the bulge of what appeared to be late catagen-phase wild-type hair follicles (Fig. 1F and fig. S4E). Furthermore, these CD34+K15+ bulge cells displayed membrane blebbing, nuclear condensation, and TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end labeling), indicating that they were bona fide apoptotic cells (fig. S4E). This suggests that HFSC apoptosis can occur within the bulge of tailskin hair follicles.

Next, we examined whether deletion of Sept4/ARTS protects HFSCs from staurosporine-and etoposide-induced apoptosis in vitro. Relative to wild-type HFSCs, Sept4/ARTS−/− HFSCs displayed a marked decrease in apoptotic markers (Fig. 1G). Because Sept4/ARTS−/− HFSCs are resistant to apoptosis, we examined whether they have greater capacity to cope with stress by culturing HFSCs without sustaining feeder cells. In contrast to wild-type HFSCs, Sept4/ARTS−/− HFSCs exhibited an increase in cell number, reaching confluence under conditions that severely hindered the growth of control cells (fig. S5). Collectively, these results reveal an important physiological function of Sept4/ARTS for HFSC apoptosis in response to stress.

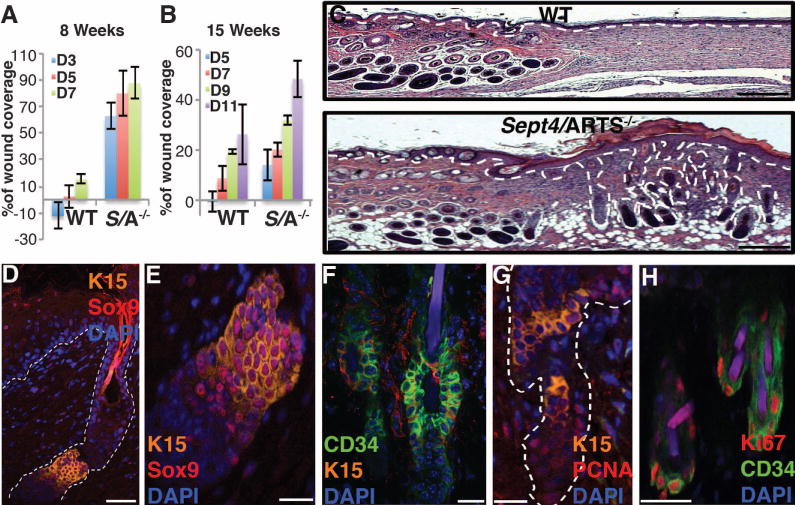

HFSCs do not contribute to normal epidermal homeostasis. However, in response to wounding, they participate in repopulating the epidermis (20, 21). Because Sept4/ARTS−/− HFSCs are protected against cell death, we investigated whether they have enhanced capacity for tissue repair. Full-thickness excision wounds (1 cm2) were generated on the dorsal skins of 8- and 15-week-old mice and monitored for wound coverage. In 8-week-old Sept4/ARTS−/− mice, the wound size was reduced by 80% after only 5 days, whereas in wild-type mice the wound size was reduced by only 10% (Fig. 2A and fig. S6A). Accelerated healing was seen at all time points. In 15-week-old mice, healing was generally slower, but again Sept4/ARTS−/− mice were more efficient in wound repair (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2. Loss of Sept4/ARTS function accelerates wound healing and improves skin regeneration.

(A and B) Reepithelialization dynamics of skins at different times PWI. Excision wounds (1 cm2) were inflicted on dorsal skin of 8-week-old [(A), n = 12] or 15-week-old mice [(B), n = 8]. Percentage of wound coverage was calculated versus original wound size. D denotes day PWI. (C) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of full-thickness excision wounds of 8-week-old mice, 18 days PWI. Hair follicle formation within the wound bed is observed in Sept4/ARTS−/− mice. (D to F) HFSC niches within regenerated hair follicles are positive for CD34, K15, and Sox9. (D) Regenerated hair follicle displays a HFSC niche positive for K15 and Sox9. (E) Zoom-in of the HFSC niche in (D). (F) Regenerated hair follicle niche is positive for CD34. (G and H) Immunofluorescence for PCNA (G) and Ki67 (H), indicating proliferative activity within the regenerated hair follicle niche of Sept4/ARTS−/− mice. Scale bars, 500 μm (C), 50 μm (D), 20 μm [(E), (F), and (G)], 10 μm (H).

By 18 days post–wound infliction (PWI), 1-cm2 wounds of 8-week-old wild-type and Sept4/ARTS−/− mice had healed. Histological analyses revealed that in contrast to wild-type mice, high numbers of hair follicles were seen in the wound beds of Sept4/ARTS−/− skins, which sometimes appeared hyperplastic but otherwise appeared relatively normal (Fig. 2, C to H). Long after wild-type HFSCs had returned to quiescence, some Sept4/ARTS−/− HFSCs were still proliferative, as indicated by PCNA (proliferating cell nuclear antigen) and Ki67 staining (Fig. 2, G and H, and fig. S6B). Together, these results suggest that the enhanced survival of HFSCs in Sept4/ARTS−/− mice is responsible for accelerated repair and hair follicle regeneration in response to injury.

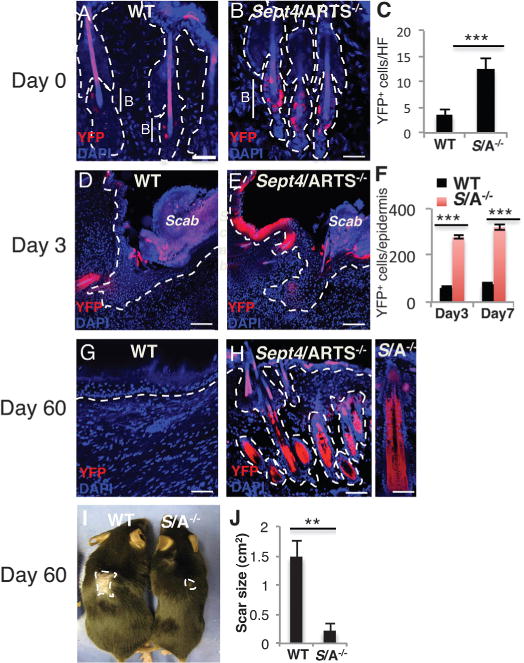

To examine the contribution of HFSCs to accelerated wound healing in Sept4/ARTS−/− mice, we used Tg(Krt1–15-cre/PGR)22Cot; Rosa26-YFP reporter mice. When induced by RU486, this reporter specifically activates Cre in HFSCs, and thereafter they and their progeny are marked by yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) (22). Sept4/ARTS−/− follicles displayed about 3.5 times as many YFP-marked HFSCs at t = 0 (Fig. 3, A to C, and fig. S7, A and B). By t = 3 days and t = 7 days after wounding, 4 to 5 times as many YFP+ cells were present in the upper hair follicles and epidermis of Sept4/ARTS−/− skin (Fig. 3, D to F, and fig. S7, C and D). Enhanced repair was also observed when Sept4/ARTS−/− mice were lineage-marked and wounded during the protracted second telogen (fig. S7, E to G). Moreover, in contrast to wild-type regeneration, Sept4/ARTS−/− HFSC progeny remained in the skin epidermis at 2 months PWI, and the scars of Sept/ARTS−/− were significantly smaller (Fig. 3, G to J). Taken together, these results suggest that apoptosis-impaired Sept4/ARTS−/− HFSCs are functional and robustly contribute to healing and hair follicle regeneration.

Fig. 3. Sept4/ARTS−/− HFSCs are responsible for enhanced tissue re-generation.

(A to H) Reporter expression was induced from P20 to P25 [(A) to (F)] or from P45 to P50 [(G) and (H)], and wounding was executed at P26 or P56, respectively (see fig. S7). Skins were analyzed at t = 0, 3, 7, 18, and 60 days PWI. WT [(A), (D), (G)] and Sept4/ARTS−/− [(B), (E), (H)] lineage tracings are shown at t = 0, 3, and 60 days. (H), right panel: Close-up of hair follicle at 60 days PWI. Dashed line indicates dermis-epidermis border; B denotes bulge. Scale bars, 50 μm [(A), (B), (G)], 100 μm [(D), (E), (H)]. (C) Quantifications of YFP+ cells in hair follicles of WT and Sept4/ARTS−/− mice (t = 0). (F) Quantification of YFP+ cells in hair follicles and epidermis of WT and Sept4/ARTS−/− mice (t = 3 and 7 days). (I and J) Scar size of WT and Sept4/ARTS−/− mice at 60 days PWI (2 cm2) (n = 3); photograph (I) and quantification (J) are shown. Dashed line indicates scar border. **P < 0.002, ***P < 0.001.

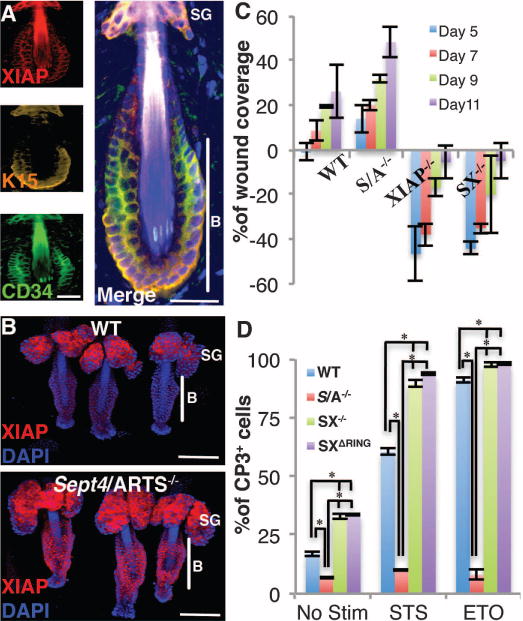

XIAP is a direct downstream target for the proapoptotic activity of ARTS (11, 12, 23, 24). XIAP−/− mice are viable and do not display overt phenotypes (7, 25). However, microarray and chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing analyses indicate that XIAP is expressed throughout skin epithelium, including the bulge (26). Because ARTS can promote ubiquitination and degradation of XIAP (27, 28), we compared XIAP protein levels in wild-type and Sept4/ARTS−/− HFSCs. In wild-type mice, anti-XIAP immunolabeling was detected in bulge HFSCs, sebaceous glands, and dermal papillae (Fig. 4, A and B, and fig. S8). Most notable, however, was the striking increase of XIAP in tailskin Sept4/ARTS−/− HFSCs (Fig. 4B and fig. S9A).

Fig. 4. XIAP is required for proper wound healing.

(A) Immunofluorescence indicates that XIAP protein is present in dorsal telogen bulge (P20) hair follicles. (B) Immunofluorescence indicates increased XIAP in Sept4/ARTS−/− tailskin hair follicles. B denotes bulge; SG, sebaceous gland. (C) Wound coverage dynamics in WT, S/A−/−, XIAP−/−, and SX−/− mice at various times PWI, as described in Fig. 3A (n = 8). (D) Quantifications of WT, S/A−/−, SX−/−, and SXΔRing CD34+CP3+ HFSCs. Scale bars, 20 μm (A), 100 μm (B). P < 0.001.

To determine the biological role of elevated XIAP in Sept4/ARTS−/− hair follicles, we generated double knockout Sept4/ARTS−/−;XIAP−/− (SX−/−) animals and examined them for wound repair and hair follicle regeneration. Intriguingly, loss of XIAP function abolished the enhanced reepithelialization of Sept4/ARTS−/− mice. In addition, wound repair in SX−/− mutants was markedly delayed relative to the wild type (Fig. 4C). XIAP−/− single mutants were severely compromised in wound repair (Fig. 4C and fig. S9B). Taken together, these results demonstrate a critical physiological role of XIAP in wound healing. Moreover, because ARTS was unable to stimulate healing in the absence of XIAP, this suggests that XIAP is a major target for the proapoptotic activity of ARTS in this system (11, 12).

To investigate whether XIAP participates in wound healing by suppressing apoptosis, we analyzed the cell death sensitivity of CD34+ HFSCs from SX−/− mutants. In contrast to Sept4/ARTS−/− (CD34+) HFSCs, SX−/− HFSCs exhibited significantly increased apoptosis (Fig. 4D and fig. S10). XIAP directly inhibits caspases and contains a RING domain required for E3 ligase activity (29). To address its importance for SC apoptosis, we analyzed XIAPΔRING mice, in which the XIAP RING domain was deleted (7). CD34+ SCs from Sept4/ARTS−/−;XIAPΔRING (SXΔRING) and SX−/− mice had virtually identical phenotypes (Fig. 4D). Finally, inactivation of XIAP also impaired the growth of CD34+ HFSCs in vitro (fig. S10). Together, these results show that XIAP is a physiological downstream target for the proapoptotic and regenerative activity of Sept4/ARTS in skin, and that XIAP RING function is required for the antiapoptotic activity of XIAP in HFSCs.

Our findings reveal the importance of apoptosis in regulating hair follicle homeostasis and wound repair, and the nonredundant functions of ARTS and XIAP in this process. At the surface, our results may appear at odds with a previously reported role of apoptosis in promoting skin wound healing, which was ascribed to mitogenic signaling by apoptotic cells (30). However, depending on the point of interference in the apoptotic pathway, the outcome for mitogenic signaling can vary considerably (31). Furthermore, our studies suggest that ARTS and XIAP function specifically in regulating apoptosis of progenitors in the hair follicle, but not in more differentiated skin cells. Therefore, targeting these genes is very different from a general inhibition of effector caspases in differentiated skin cells. Our results suggest that targeting apoptotic pathways in HFSCs may have therapeutic benefits to promote wound healing and regeneration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We apologize to colleagues whose contributions we could not adequately cite because of space constraints. We thank B. Keyes, Y. C. Hsu, N. Stokes, and I. Shachrai for discussion, advice, and technical assistance; S. Mazel, X. Li, S. Semova, and S. Tadesse for FACS sorting; the Comparative Biology Center (AAALAC-accredited) for health care to our mice; and members of the Steller lab. H.S. and E.F. are Investigators of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Supported by NIH grants RO1GM60124 (H.S.) and R01-AR050452 (E.F.). The Sept4/ARTS and XIAP mouse mutant strains used in this study are available from the Rockefeller University to academic groups through a materials transfer agreement and to for-profit groups through a license.

Footnotes

References and Notes

- 1.Weissman IL. Science. 2000;287:1442–1446. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rafii S, Lyden D. Nat Med. 2003;9:702–712. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsu YC, Fuchs E. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:103–114. doi: 10.1038/nrm3272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuchs Y, Steller H. Cell. 2011;147:742–758. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gyrd-Hansen M, Meier P. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:561–574. doi: 10.1038/nrc2889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuranaga E, Miura M. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schile AJ, García-Fernández M, Steller H. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2256–2266. doi: 10.1101/gad.1663108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kornbluth S, White K. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:1779–1787. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergmann A, Yang AY, Srivastava M. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:717–724. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larisch S, et al. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:915–921. doi: 10.1038/35046566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gottfried Y, Rotem A, Lotan R, Steller H, Larisch S. EMBO J. 2004;23:1627–1635. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.García-Fernández M, et al. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2282–2293. doi: 10.1101/gad.1970110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuchs E. Nature. 2007;445:834–842. doi: 10.1038/nature05659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrison SJ, Spradling AC. Cell. 2008;132:598–611. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jahoda CA, Christiano AM. Cell. 2011;146:678–681. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woo WM, Oro AE. Cell. 2011;146:334. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris RJ, et al. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:411–417. doi: 10.1038/nbt950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsu YC, Pasolli HA, Fuchs E. Cell. 2011;144:92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Müller-Röver S, et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:3–15. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ito M, et al. Nat Med. 2005;11:1351–1354. doi: 10.1038/nm1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brownell I, Guevara E, Bai CB, Loomis CA, Joyner AL. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:552–565. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ito M, et al. Nature. 2007;447:316–320. doi: 10.1038/nature05766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reed JC. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:17–22. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LaCasse EC, et al. Oncogene. 2008;27:6252–6275. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harlin H, Reffey SB, Duckett CS, Lindsten T, Thompson CB. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:3604–3608. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.10.3604-3608.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lien WH, et al. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:219–232. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garrison JB, et al. Mol Cell. 2011;41:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edison N, et al. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:356–368. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fulda S, Vucic D. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:109–124. doi: 10.1038/nrd3627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li F, et al. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra13. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bergmann A, Steller H. Sci Signal. 2010;3:re8. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3145re8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.