Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study was to evaluate gynecologic oncology provider (GOP) practices regarding weight loss (WL) counseling, and to assess their willingness to initiate weight loss interventions, specifically bariatric surgery (WLS).

Methods

Members of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology were invited to complete an online survey of 49 items assessing knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors related to WL counseling.

Results

A total of 454 participants initiated the survey, yielding a response rate of 30%. The majority of respondents (85%) were practicing GOP or fellows. A majority of responders reported that >50% of their patient population is clinically obese (BMI ≥ 30). Only 10% reported having any formal training in WL counseling, most often in medical school or residency. Providers who feel adequate about WL counseling were more likely to offer multiple WL options to their patients (p < .05). Over 90% of responders believe that WLS is an effective WL option and is more effective than self-directed diet and medical management of obesity. Providers who were more comfortable with WL counseling were significantly more likely to recommend WLS (p < .01). Approximately 75% of respondents expressed interest in clinical trials evaluating WLS in obese cancer survivors.

Conclusions

The present study suggests that GOP appreciate the importance of WL counseling, but often fail to provide it. Our results demonstrate the paucity of formal obesity training in oncology. Providers seem willing to recommend WLS as an option to their patients but also in clinical trials examining gynecologic cancer outcomes in women treated with BS.

Keywords: Obesity, Weight loss training, Weight loss surgery, Endometrial cancer

Introduction

Obesity and its consequences are some of the leading causes of mortality in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control recently reported a nationwide obesity rate of 35%, a number that is expected to grow to a staggering 51% by the year 2030 if current trends persist [1,2]. While cancer is also a leading cause of death in the US, screening and early detection programs combined with improved treatment modalities are creating a growing number of long-term cancer survivors. According to the American Cancer society, there are now more than 13.7 million cancer survivors in the United States and is projected to be nearly 18 million by 2022 [3]. Obese women are two to four times more likely than non-obese women to develop endometrial cancer, but also have a less aggressive histologic subtype and tend to be diagnosed with stage I disease [4,5]. Thus, the parallel increase in obesity and incidence of gynecologic cancer, specifically endometrial cancer, results in an increasing number of unhealthy patients who enter post-treatment surveillance every year.

Obesity has been associated with an increased risk of early mortality regardless of cancer status [7]. In breast cancer, obesity is correlated with higher breast cancer-related and all-cause mortality [6]. There have been similar findings in patients with early-stage endometrial cancer [5]. Data from the Cancer Prevention Study II, suggested that women with a BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 were six times more likely to die from endometrial cancer than those of a normal weight [7]. von Gruenigen et al. found that while obesity was not associated with increased recurrence risk, higher BMI was associated with higher all-cause mortality [9]. This is consistent with an analysis of SEER data suggesting that women with local, low-grade endometrial cancer who survived >5 years were more likely to die from cardiovascular disease than their cancer [8].

Oncologists might have the ability to affect obesity rates and thereby improve overall outcomes among cancer survivors. Following primary therapy, the surveillance period often lasts up to five years or longer from the end of therapy; during this time a patient will see their oncologist on average every 3–12 months. Our study was designed to evaluate what role oncologists play in obesity management of their patients, specifically assessing knowledge and beliefs about obesity, level of training in weight loss intervention, weight loss counseling behaviors, and willingness to prescribe weight loss strategies, including weight loss surgery (WLS).

Methods

Approval was obtained from the institutional review board at the Ohio State University Medical Center. An email invitation was sent to all active members of SGO followed by reminder emails two and four weeks later. The email message contained an explanation of the study purpose, instructions on how to complete it, and a statement of consent. Participation was voluntary and no incentive was offered.

A 49-question online survey was administered to all who consented. Items covered three primary domains: provider socio-demographics and practice descriptors, obesity management training, and weight loss intervention counseling behaviors. To provide a basis for comparison, items related to weight loss counseling were complemented with items related to smoking cessation counseling. The majority of the questions were presented in multiple-choice format with item-appropriate responses (e.g., categorical options for classification items; five-point Likert scales for items assessing subjective responses such as confidence in counseling and beliefs on obesity health effects.

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS v19.0.0. Descriptive statistics are provided for sociodemographic and practice characteristics. Associations among variables were examined using Pearson and point-biserial correlations (two-tailed), one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA, for continuous-categorical combinations), and χ2 tests (categorical-categorical), as appropriate. Multivariate analyses (hierarchical multiple linear regression, HMLR) were used to examine variables associated with provider knowledge and beliefs related to WLS.

Results

Of the 1712 members invited, 454 (30%) participants consented to the online survey; of these, 369 (81%) completed it (i.e., provided response to at least 75% of the items). The membership of SGO includes oncologists as well as nurses, physician assistants, trainees, and other providers. There were insufficient numbers of non-physician providers to make meaningful comparisons across categories and thus data from non-physician providers and residents were excluded from the analyses (n = 42, 11%), yielding a final sample of N = 327.

See Table 1 for participant sociodemographic and practice characteristics. Over half (56%) were ≤44 years old and 55% have been in practice ≤10 years. There was a balanced distribution of participants from each of the listed demographic locales, practice locations, and distribution of patient interactions. Women with endometrial cancer comprised the majority of the reported patient interactions followed by patients with ovarian and cervical cancers. Patients with non-malignant conditions comprised 25–50% of a providers’ practice for roughly half of respondents. Regarding the prevalence of obesity among their patients, 58% of providers reported that at least half of their patient population was clinically obese (BMI ≥30). Only 11% of providers reported receiving formal obesity management training. Of those who had formal training, only approximately 25% (n = 10) stated that they received training during fellowship. The most commonly reported types of “formal training” were conference courses and self-directed readings1 (see Table 2). Having received formal training (no vs. yes) was significantly positively correlated with comfort in discussing weight loss (r = 0.11, p = 0.04); those who reported no training were significantly more concerned about insulting their patients.

Table 1.

Participant sociodemographic and practice characteristics.

| Provider characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 34 and younger | 62 | 19% |

| 35–44 | 122 | 37% |

| 45–54 | 76 | 23% |

| 55–64 | 47 | 15% |

| 65 and older | 20 | 6% |

| Profession/level of training | ||

| Gynecologic oncologist | 268 | 82% |

| Medical oncologist | 4 | 1% |

| Radiation oncologist | 4 | 1% |

| OB/GYN | 5 | 2% |

| Physician-fellow | 46 | 14% |

| Years in practice | ||

| 0–5 | 123 | 38% |

| 6–10 | 55 | 17% |

| 11–20 | 73 | 22% |

| >20 | 75 | 23% |

| Where do you practice? | ||

| Northeast | 80 | 25% |

| Midwest | 58 | 18% |

| Southeast | 74 | 23% |

| Southwest | 60 | 18% |

| West | 30 | 9% |

| Outside USA | 15 | 5% |

| Type of clinical practice | ||

| Academic medical center | 202 | 63% |

| Community teaching hospital | 63 | 20% |

| Community hospital | 21 | 6% |

| Private practice | 35 | 11% |

| Percent of obese patients | ||

| <10% | 4 | 1% |

| 10–25% | 30 | 9% |

| 26–50% | 100 | 31% |

| 51–75% | 157 | 49% |

| >75% | 31 | 10% |

Note: Totals do not always add to 327 because a small number of respondents did not complete individual items.

Table 2.

Types of formal training.

| Where did you receive formal training on obesity management and weight loss? | N = 35 |

|---|---|

| Conference lectures | 20 |

| Self-directed reading | 20 |

| Medical school | 15 |

| Residency didactics | 13 |

| Fellowship didactics | 10 |

| CME course | 2 |

Nearly all of the responders were in agreement that obesity increases a patient’s risk of developing diabetes, hypertension, endometrial cancer, and having a shorter life expectancy. While 84% of providers reported being adequately informed about obesity-related health risks, only 63% reported that they could adequately counsel a patient about weight loss. Correlational analyses indicate that increased knowledge of obesity’s health effects was significantly positively correlated with provider confidence about counseling patients (r = .43; p < .05) and discussing more options for weight loss (r = .14; p = .01).

Nearly all (93%) providers reported that they make some effort to counsel patients about weight loss at least some of the time; however only half (51%) of providers reported “almost always” counseling overweight and obese patient about weight loss. This is in contrast to the 74% who “almost always” counsel a smoker about cessation. Furthermore, 50% stated that they provide smoking cessation counseling at every visit, only 28% reported they do the same for weight loss counseling. We used paired sample t-tests to examine these contrasts and found that providers were significantly more likely to offer smoking cessation counseling than weight loss counseling to those who needed it [t(322) = −5.86, p < 0.001]. Providers were also significantly more likely to be concerned about insulting patients by providing weight loss counseling (30%) versus smoking cessation counseling (17%) [t(323) = −10.05, p < 0.001]. Those who did provide weight loss counseling typically did so during follow-up visits.

Providers identified patients with endometrial cancer as the patient cohort to whom they believed they would be most likely to offer weight loss counseling. Even so, 32% stated they would offer weight loss regimens equally to patients with all types of cancer. While most reported some effort to counsel patients, only half reported recommending one or more specific weight loss interventions. Calculated provider BMI (from provider responses) and self-defined weight status (i.e. ‘obese’) were not significantly correlated with initiating discussions about weight loss. Among providers recommending specific weight loss interventions, self-directed diet (82%) and exercise (81%) were those most common interventions endorsed, followed by dietary programs such as Weight Watchers (73%), and program-guided exercise (e.g., personal trainer; 65%). Provider confidence in their ability to counsel patients about weight loss was significantly positively correlated with the number of weight loss interventions recommended to patients (r = .15, p = .01), as was treating a larger proportion of obese patients (r = .20, p < .05). Providers who routinely prescribe weight loss regimens for obese patients were significantly more likely to recommend a second option if the first failed (r = .33, p < .05).

Variables associated with recommendations for WLS

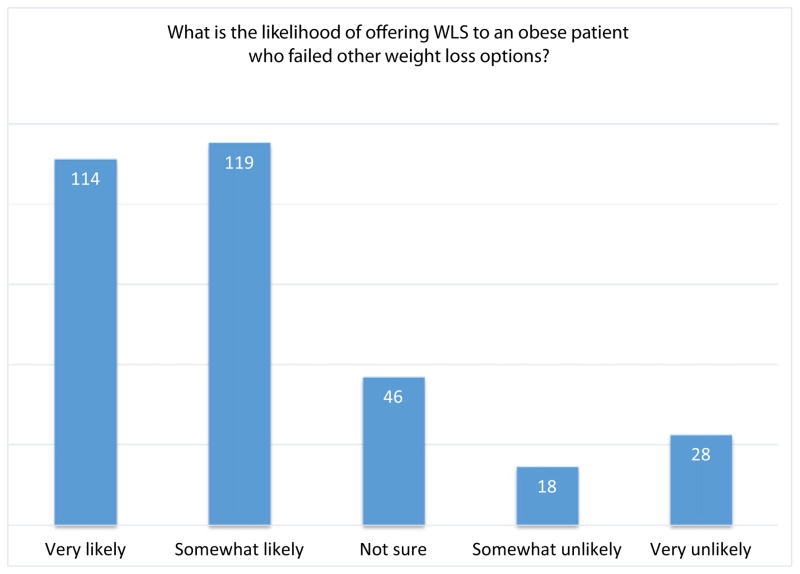

Correlations between provider characteristics and knowledge/beliefs about obesity and WLS as a specific recommendation are reported in Table 3. Almost all providers (98%) were familiar with at least one type of WLS and had treated at least one patient with a history of WLS. Approximately 90% of providers who treated patients with a history of WLS agreed that it is an effective weight loss intervention; however, less than half agreed that WLS was more effective than diet/exercise, medical weight management, or program driven exercise. Most (72%) stated they would be “somewhat” or “very” likely to recommend WLS to patients who had failed other weight loss attempts (Fig. 1). Age, years in practice, practice type, and provider BMI were not significantly associated with likelihood of offering WLS. Providers who routinely offer multiple weight loss options were significantly more likely to offer WLS (r = .12, p = .03). Receiving formal obesity management training was not significantly associated with the likelihood of offering WLS (p = .16). Providers were more likely to offer WLS to endometrial cancer survivors as compared to survivors of other gynecologic malignancies.

Table 3.

Correlations between provider characteristics and knowledge/beliefs about obesity and WLS as a specific recommendation.

| What is the likelihood that you would offer WLS to a patient who has failed other methods of weight loss?

|

How likely would you be to enroll your patients in a clinical trial evaluating the role of WLS in gynecologic cancer patients?

|

|

|---|---|---|

| r (p-value) | r (p-value) | |

| Provider/practice characteristics | ||

| Percentage of patients with endometrial cancer | r = .11 (p = .06) | r = .07 (p = .19) |

| Percentage of patients clinically obese | r = .17 (p = .002)** | r = .16 (p = .003)** |

| Have you ever received or participated in formal training with regard to obesity management? | r = .08 (p = .16) | r = .03 (p = .66) |

| Frequency providing weight loss counseling to overweight patients | r = .20 (p < .001)*** | r = .09 (p = .09) |

| Discussion of multiple weight loss options | r = .12 (p = .03)* | r = .01 (p = .89) |

| Have you ever treated someone with WLS? | r = .09 (p = .09) | r = .15 (p = .006)** |

| If yes, how would you rate the level of successful weight loss for those patient(s)? | r = .13 (p = .02)* | r = .13 (p = .02)* |

| Provider self-ratings | ||

| How would you rate your knowledge on obesity and its health effects? | r = .23 (p < .001)*** | r = .12 (p = .03)* |

| How would you rate your ability to counsel a patient about losing weight? | r = .17 (p = .002)** | r = .10 (p = .07) |

| Knowledge/beliefs regarding obesity | ||

| Health risks associated with obesity | r = .11 (p = .06) | r = .16 (p = .003)** |

| Knowledge/beliefs regarding WLS | ||

| Familiarity with various types of WLS | r = .12 (p = .03)* | r = .01 (p = .90) |

| Perceived barriers to offering WLS | r = .01 (p = .86) | r = .02 (p = .73) |

| Effectiveness of WLS for weight loss | r = .28 (p < .001)*** | r = .28 (p < .000)*** |

| Effectiveness of WLS for improving health | r = .31 (p < .001)*** | r = .31 (p < .001)*** |

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

Correlation is significant at the 0.001 level (2-tailed).

Fig. 1.

Likelihood of offering WLS to an obese patient who failed other weight loss options.

When asked hypothetically if WLS were proven to reduce the risk of cancer recurrence or improve mortality, 90% were likely to offer it as a treatment option. Furthermore, providers reported being more likely to offer WLS if it was proven to reduce the risk of other co-morbid conditions. In fact, there was a significant correlation between offering WLS and how clinicians rated WLS effectiveness at improving health (r = .31, p < .001). Not surprisingly, 67% identified cost or insurance coverage as the leading barriers to WLS followed by maintenance of dietary restrictions/patient motivation. Almost 84% of those surveyed would consider enrolling obese cancer patients in a clinical trial to evaluate the role of WLS on morbidity and mortality rates. Those practitioners who perceived the health risks of obesity to be higher for patients were significantly more likely to be willing to offer WLS in a clinical trial (r = .16, p = .003); see (Table 2).

To examine which variables would remain significantly associated with WLS recommendations if provider characteristics and knowledge/beliefs about obesity and WLS were considered simultaneously, HMLR was used. Variables were entered into the HMLR models as follows: Step 1: provider/practice characteristics; Step 2: ratings of providers’ beliefs about their own knowledge and/or ability to counsel patients; Step 3: knowledge/beliefs regarding the risks associated with obesity; and Step 4: knowledge/beliefs regarding WLS and its effectiveness. Provider characteristics and knowledge/beliefs about obesity/WLS that were significantly correlated with likelihood of recommending WLS and enrolling patients in a clinical trial testing WLS were included in the multivariate analyses, i.e., empirical selection of predictors; thus, the first regression includes only three steps (provider/practice characteristics, beliefs about one’s own knowledge/ability; knowledge/beliefs re: WLS), while the second includes all four. Results of the regression analyses are included in Table 4. Both models were significant, accounting for 24% and 15% of the variance in likelihood of recommending WLS when other methods had failed and enrolling patients in a clinical trial, respectively. Beliefs about the effectiveness of WLS for weight loss and improving overall health were important, accounting for approximately 10% of the variance in both outcomes. Treating a larger proportion of obese patients, tendency to discuss multiple options for weight loss, and higher self-rated knowledge was also significantly associated with increased likelihood of recommending WLS following failure of other WL methods.2

Table 4.

Multivariate analyses.

| Step and predictors | ΔR2 | β | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome: Likelihood of offering WLS to patient who has failed other methods of weight loss? | |||

| 1. Provider/practice characteristics | .10 | ||

| Percentage of patients obese | .12 | .02* | |

| Frequency providing WL counseling | .03 | .64 | |

| Discussion of various WL options | .22 | <.001*** | |

| 2. Provider self-ratings | .03 | ||

| Knowledge on obesity and its health effects | .17 | .01* | |

| Ability to counsel about losing weight | .02 | .75 | |

| 3. Knowledge/beliefs about WLS | .12 | ||

| Knowledge of various types of WLS | .06 | .25 | |

| Effectiveness of WLS for weight loss | .22 | <.001*** | |

| Effectiveness of WLS for improving health | .16 | .008** | |

| F(8,290) = 11.63, p < .001, total R2 = 0.24 | |||

| Outcome: How likely would you be to enroll patients in clinical trial evaluating WLS in gyn cancer? | |||

| 1. Provider/practice characteristics | .05 | ||

| Percentage of patients obese | .10 | .06 | |

| Previously treated WLS patient | .07 | .23 | |

| Discussion of various WL options | .08 | .16 | |

| 2. Provider self-ratings | <.01 | ||

| Knowledge on obesity and its health effects | .04 | .48 | |

| 3. Beliefs about obesity | .02 | ||

| Risks associated with obesity | .06 | .27 | |

| 4. Beliefs about WLS | .08 | ||

| Effectiveness of WLS for weight loss | .18 | .003** | |

| Effectiveness of WLS for improving health | .16 | .01* | |

| F(7,307) = 7.85, p < .001, total R2 = 0.15 | |||

Statistics by predictor are reported for the final HMLR model. Reported β is standardized.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Discussion

Recently, the American Heart Association released new guidelines in which they encourage providers to treat obesity as a chronic disease at each clinical encounter. While most would point to this as a referendum on primary care providers, gynecologic oncologists can look at innovative ways to strike this balance. The present study highlights the fact that providers understand the need for weight loss counseling and agree that obesity increases the risk for early death, diabetes, and hypertension. However, there appears to be a gap between knowledge about obesity and ability to counsel obese patients on weight loss. While an overwhelming majority agreed on the negative health effects of obesity, only about 60% felt adequately prepared to provide weight loss counseling and only 50% reported that they actually provide it. This gap between knowledge and practice is one that deserves attention. This study suggests that a possible explanation for this is the general lack of formal training, as demonstrated by the fact that only 10% of respondents reportedly had formal training in obesity management and 4% received it during fellowship. An important component of counseling is what options the provider feels comfortable offering to patients. In this study, most providers were willing to discuss self-directed diet and exercise with obese patients followed by medical weight management or other hospital based services.

We explored the practice of recommending WLS as an option. Providers were generally accepting of the idea of bariatric surgery in obese cancer survivors and more than 70% would offer this option if a patient failed other weight loss options. Further educating providers on the success rates of different weight loss strategies could help to change practice patterns. Our data suggests that a trial demonstrating a benefit of WLS to obese cancer survivors, in particular to endometrial cancer survivors, would perhaps change current practice models. Nonetheless, while referring a patient to a bariatric program does not commit a patient to surgery it does provide the opportunity for patients to discuss options with people more experienced with weight loss counseling and the detrimental effects of obesity on health outcomes. Education and access to information can perhaps be the most important thing providers do for their patients.

We attempted to parse variables that might identify providers who were more likely to offer WLS to obese patients. As noted previously in Table 2, we found significant associations between knowledge on obesity and beliefs about the effectiveness of WLS and the willingness to offer surgical options to obese patients. Surprisingly however, we did not find a statistical relationship between a provider having received formal training and an increased likelihood of offering WLS. This may have been because of the overall low numbers of individuals stating they had received formal training. In addition to this we must remember that despite personal convictions, providers must consider many factors when deciding whether to recommend WLS. Various confounders including disease status, medical comorbidities, and patient motivation become greater factors in making these decisions. From our data we performed a multivariate analysis of variables that affect whether a provider would offer WLS to a patient (Table 4). A providers’ personal beliefs about the effectiveness of WLS for sustained weight loss were a strong independent predictor of offering WLS.

Several limitations merit discussion. Surveys are inherently subject to selection bias, as those who choose to participate may have a greater interest in the subject presented. The response rate for our survey was 30%, which is consistent with web-based survey research. The majority of our responders are from the eastern United States (Northeast, Midwest, and Southern regions), full-time gynecologic oncologists, and early career professionals. The demographics of the present sample are comparable to that of the SGO membership; we found equivalent distribution of age, years in practice, and practice type. Regarding survey participation, a majority of the members who replied to the 2010 survey, fell into similar geographic distributions and practice descriptors [23]. Given the discrepancy between obesity rates in the Midwest/South and the Western United States, it may be argued that our results are difficult to generalize to all providers of gynecologic oncology care; however, there is no question that obesity is becoming an increasingly more prevalent condition in women with gynecologic malignancies.

The structure of our study was designed to build upon a previous report by researchers at Johns Hopkins. The study presented by Jernigan et al. was a survey project that highlighted providers’ desire to initiate the weight loss discussion and educate patients about obesity-related health effects despite a general low degree of training in obesity management [10]. Our study sampled a larger number of providers, and looked in greater detail at the content of counseling as well as how training impacts the quantity and quality of that counseling. In addition, our study focused on interest in offering WLS as a means to improve overall morbidity/mortality for our patients.

We found that a minority of providers received formal training. Our results show that only about 60% of providers felt adequate in their counseling. The ABOG educational objectives state that fellows should be competent in not only the effective treatment of health problems, but also the promotion of health. Following a review of the literature and the results of this study, we have concluded that even a relatively small amount of training can impact the ability to counsel patients effectively. In the study by Wadden et al. published in the New England Journal of Medicine, researchers evaluated the effectiveness of intra-office weight loss counseling with primary care providers. The providers in the study were given between 6 and 8 h of formal training. While their results did not show a statistical advantage to weight loss without the help of diet medication, they found that up to 20% of obese patients could see a loss of 5% body weight simply by providing this enhanced counseling [11]. We propose an education program to be incorporated into fellowship training. This could entail standard didactic lectures from registered dieticians on the basics of a healthy diet or simple weight loss goals provided by certified weight loss counselors. In addition, academic centers affiliated with a bariatric center could be a setting for further weight loss training for a fellow. Short rotations with specialized counselors aimed at the many components to weight loss could also be an avenue for developing training in obesity management. Finally, we would like to give a special mention to the new ‘Obesity Tool Kit’ recently published by the SGO (www.sgo.org/obesity). This may provide a foundation for improving obesity knowledge and weight loss counseling among providers at all stages of their careers.

Providers who responded were most in favor of providing weight loss counseling to obese endometrial cancer patients. While we did not specifically address how a patient’s baseline disease stage might affect their counseling, we found that most providers initiated discussions in the ‘follow up’ period. Given these two findings, we are assuming that low-stage endometrial cancer patients are highest priority. One consideration that must be addressed is how our system of managed care may make weight surveillance a difficult task for the oncologist. Early stage, low risk obese endometrial cancer patients may not require long term follow-up with an oncologist for surveillance. This puts the onus on initiating the counseling sooner, coordinating continued counseling with a primary OB/GYN, and perhaps referral to weight loss specialists if readily available. Furthermore, these potential changes to the healthcare delivery system make the argument even stronger that a small amount of training is required to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of weight loss counseling among gynecologic oncology providers.

There is no clear consensus on what provider bears the responsibility of weight loss counseling for cancer survivors—the oncologist, the PCP, etc. Previous research has highlighted the fact that patients and physicians have a different perspective on who should take the most active role in survivorship care. Patients in general feel that their oncologist should take an active role, and oncologists generally felt that health maintenance was the job of primary care providers [12]. Our study highlights the fact that providers believe that their contribution to weight loss is important, but that they often fail to initiate the discussion. Since oncologists are sometimes viewed as the “primary care providers” during cancer survivorship, their hesitancy about initiating the discussion may be reflected in the fact that cancer survivors have worse outcomes from co-morbid conditions than those without cancer [13]. This is an unfortunate surprise given the long follow-up and access to care afforded these individuals during their cancer surveillance. Obesity could and perhaps should be the area where gynecologic oncologists focus their efforts for change.

It is estimated that up to 70% of endometrial cancer survivors are obese and that they are more likely to die from cardiovascular disease [8]. Providers of gynecologic oncology care therefore may have a unique opportunity to make a significant survival impact for these patients by initiating the weight loss discussion and perhaps collaborating with primary care physicians and even bariatric specialists. In order to achieve this, weight loss management must be an important aspect of follow-up care for women with gynecologic malignancies. Nearly all of the respondents in our study stated that they make an effort to discuss weight loss; however, less than half make a recommendation for weight loss plans. Interestingly, the most common recommendations for weight loss were self-directed diet and exercise despite evidence suggesting it to be less effective than other modalities such as program-directed weight loss or bariatric surgery [14–16]. Previous research by von Gruenigen et al. has shown that sustained weight loss through exercise and a healthy diet is possible in the endometrial cancer population [17]. Unfortunately this amount of coordination is often difficult to attain outside of a clinical trial and thus less likely to be successful for the general population.

To answer this dilemma, we explored the knowledge and willingness of providers toward providing bariatric surgery as a mode of weight loss in obese patients. There is increasing evidence that surgical weight loss is not only more effective at sustaining weight loss than diet and exercise alone, but may also reduce the risk of diabetes, cardiovascular events, and mortality [18–20]. We found that gynecologic oncology care providers are familiar with the various types of bariatric surgery as well as the health benefits of this approach. Most of our providers reported having treated a patient following surgical weight loss, and the vast majority said it had a positive impact on their patients’ lives. Over 70% of providers asked stated that they would consider offering surgical weight loss as an option to obese patients who failed other methods. We also noted a significant relationship between comfort level with discussing weight loss and offering bariatric surgery to patients. In most cases providers feel that the barrier of cost and access would impact a patient’s ability to seek bariatric surgery. The cost of a procedure often is weighted against the potential benefit long-term. A study comparing the cost effectiveness of laparoscopic gastric bypass and gastric banding to non-operative weight loss showed that both options were cost effective in morbidly obese patients [21]. To date there have been no trials looking at how surgical weight loss might impact morbidly obese cancer survivors. Our group has recently reported on a cost-effectiveness analysis on bariatric surgery for Type I endometrial cancer survivors which showed an advantage toward WLS on overall mortality [22]. We feel that further studies evaluating this option may be warranted given the positive response to this survey as well as the growing body of literature proving it to be a superior form of weight loss and a potential mode of decreasing the impact of co-morbid conditions.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Providers understand the importance of weight loss, but often fail to provide it.

Bariatric surgery is favored among providers as an option for obese cancer survivors.

A formal training program in obesity training for fellows is proposed.

Footnotes

Previous presentation: Poster presentation at the 19th Annual Society of Gynecologic Oncology Winter Meeting, February 19–21, Breckenridge, CO.

Self-directed learning was a broad answer that we provided in the survey to encompass these extra educational materials such as CME reading topics or other reading materials not provided to them by external sources.

Ratings of WL success for patients undergoing WLS were significantly correlated with likelihood of recommending WLS as an additional WL strategy and likelihood of enrolling a patient in a clinical trial of WLS in the bivariate analyses (see Table 2). Inclusion of this variable in the regression models would exclude the 7% of providers who had not treated patient who had undergone WLS. That said, we did run the regression models including this variable; perceptions of success of WLS did not account for additional variance in either of WLS outcomes or otherwise change the pattern of results and so it was excluded from the primary regression analyses.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors of this study have no conflicts to disclose related to this study.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. NCHS data brief. 82. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. Prevalence of obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finkelstein Eric A, Khavjou Olga A, Hope Thompson, Trogdon Justin G, Liping Pan, Bettylou Sherry, et al. Obesity and severe obesity forecasts through 2030. Am J Prev Med0749-3797 June. 2012;42(6):563–70. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figs. 2013. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith RA, von Eschenbach AC, Wender R, Levin B, Byers T, Rothenberger D, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of cancer: update of early detection guidelines for prostate, colorectal, and endometrial cancers. Also: update 2001—testing for early lung cancer detection CA. Cancer J Clin. 2001;51:38–75. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.51.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Everett E, Tamini H, Geer B, Swisher E, Paley P, Mandel L, et al. The effect of body mass index on clinical/pathologic features, surgical morbidity, and outcome in patients with endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90:150–7. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00232-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Protani M, Coory M, Martin JH. Effect of obesity on survival of women with breast cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat Oct. 2010;123(3):627–35. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0990-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1625–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ward KK, Shah NR, Saenz CC, McHale MT, Alvarez EA, Plaxe SC. Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death among endometrial cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;126:176–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.von Gruenigen VE, Tian C, Frasure H, Waggoner S, Keys H, Barakat RR. Treatment effects, disease recurrence, and survival in obese women with early endometrial carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer. 2006;107(12):2786–91. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jernigan AM, Tergas AI, Satin AJ, Fader AN. Obesity management in gynecologic cancer survivors: provider practices and attitudes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208:408, e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wadden TA, Volger S, Sarwer D, Vetter ML, Tsai AG, Berkowitz RI, et al. A two-year randomized trial of obesity treatment in primary care practice. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1969–79. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheung WY, Neville BA, Cameron DB, Cook EF, Earle CC. Comparisons of patient and physician expectations for cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2489–95. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.3232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snyder CF, Frick KD, Herbert RJ, Blackford AL, Neville BA, Wolff AC, et al. Quality of care of comorbid conditions during the transition to survivorship: differences between cancer survivors and noncancer controls. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(9):1140–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rock CL, Flatt SW, Sherwood NE, Karanja N, Pakiz B, Thompson CA. Effect of a free prepared meal and incentivized weight loss program on weight loss and weight loss maintenance in obese and overweight women, a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304(16):1803–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gloy VL, Briel M, Bhatt DL, Kashyap SR, Mingrone G, Bucher HC, et al. Bariatric surgery versus non-surgical treatment for obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMJ. 2013;347:f5934. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sjöström L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, Torgerson J, Bouchard C, Carlsson B, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2683–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Von Gruenigen V, Frasure H, Kavanagh MB, Janata J, Waggoner S, Rose P, et al. Survivors of uterine cancer empowered by exercise and healthy diet (SUCCEED): a randomized controlled trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125:699–704. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlsson L, Peltonen M, Ahlin S, Anveden A, Bouchard C, Carlsson B, et al. Bariatric surgery and the prevention of type 2 diabetes in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:695–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sjöström L, Peltonen M, Jacobson P, Sjöström CD, Karson K, Wedel H, et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term cardiovascular events. JAMA. 2012;307:56–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sjöström L, Narbro K, Sjöström CD, Karason K, Larsson B, Wedel H, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salem L, Devlin A, Sullivan S, Flum D. Cost-effectiveness analysis of laparoscopic gastric bypass, adjustable gastric banding, and nonoperative weight loss interventions. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neff R, Cohn DE, Chino J, O’Malley DM, Havrilesky LJ. Bariatric surgery of a means to decrease mortality in women with type I endometrial cancer—an intriguing option in a population at risk for dying of complications of metabolic syndrome. Abstract, Presented at 2014 Society of Gynecologic Oncology Annual Meeting; Tampa, FL. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Society of Gynecologic Oncologists. Gynecologic oncology: the state of the subspecialty. 2010. pp. 19–31. [Google Scholar]