Abstract

Objective

Although numerous cardiac abnormalities have been reported in HIV-infected children, precise estimates of the incidence of cardiac disease in these children are not well-known. The objective of this report is to describe the 2-year cumulative incidence of cardiac abnormalities in HIV-infected children.

Methodology: Design

Prospective cohort (Group I) and inception cohort (Group II) study design.

Setting

A volunteer sample from 10 university and public hospitals.

Participants

Group I consisted of 205 HIV vertically infected children enrolled at a median age of 22 months. This group was comprised of infants and children already known to be HIV-infected at the time of enrollment in the study. Most of the children were African-American or Hispanic and 89% had symptomatic HIV infection at enrollment. The second group included 611 neonates born to HIV-infected mothers, enrolled during fetal life or before 28 days of age (Group II). In contrast to the older Group I children, all the Group II children were enrolled before their HIV status was ascertained.

Interventions

According to the study protocol, children underwent a series of cardiac evaluations including two-dimensional echocardiogram and Doppler studies of cardiac function every 4 to 6 months. They also had a 12-or 15-lead surface electrocardiogram (ECG), 24-hour ambulatory ECG monitoring, and a chest radiograph every 12 months.

Outcome Measures

Main outcome measures were the cumulative incidence of an initial episode of left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, cardiac enlargement, and congestive heart failure (CHF). Because cardiac abnormalities tended to cluster in the same patients, we also determined the number of children who had cardiac impairment which we defined as having either left ventricular fractional shortening (LV FS) ≤25% after 6 months of age, CHF, or treatment with cardiac medications.

Results: Cardiac Abnormalities

In Group I children (older cohort), the prevalence of decreased LV function (FS ≤25%) was 5.7% and the 2-year cumulative incidence (excluding prevalent cases) was 15.3%. The prevalence of echocardiographic LV enlargement (LV end-diastolic dimension z score >2) at the time of the first echocardiogram was 8.3%. The cumulative incidence of LV enddiastolic enlargement was 11.7% after 2 years.

The cumulative incidence of CHF and/or the use of cardiac medications was 10.0% in Group I children. There were 14 prevalent cases of cardiac impairment (LV FS ≤25% after 6 months of age, CHF, or treatment with cardiac medications) in Group I. After excluding these prevalent cases, the 2-year cumulative incidence of cardiac impairment was 19.1% among Group I children and 80.9% remained free of cardiac impairment after 2 years of follow-up.

Within Group II (neonatal cohort), the 2-year cumulative incidence of decreased LV FS was 10.7% in the HIV-infected children compared with 3.1% in the HIV-uninfected children. LV dilatation was also more common in Group II infected versus uninfected children (8.7% vs 2.1%). The cumulative incidence of CHF and/or the use of cardiac medications was 8.8% in Group II infected versus 0.5% in uninfected subjects. The 1- and 2-year cumulative incidence rates of cardiac impairment for Group II infected children were 10.1% and 12.8%, respectively, with 87.2% free of cardiac impairment after the first 2 years of life.

Mortality

In the Group I cohort, the 2-year cumulative death rate from all causes was 16.9% [95% CI: 11.7%–22.1%]. The 1- and 2-year mortality rates after the diagnosis of CHF (Kaplan-Meier estimates) were 69% and 100%, respectively. In the Group II cohort, the 2-year cumulative death rate from all causes was 16.3% [95% CI: 8.8%–23.9%] in the HIV-infected children compared with no deaths among the 463 uninfected Group II children. Two of the 4 Group II children with CHF died during the 2-year observation period and 1 more died within 2 years of the diagnosis of CHF. The 2-year mortality rate after the diagnosis of CHF was 75%.

Conclusions

This study reports that in addition to subclinical cardiac abnormalities previously reported by the P2C2 Study Group, an important number of HIV-infected children develop clinical heart disease. Over a 2-year period, approximately 10% of HIV-infected children had CHF or were treated with cardiac medications. In addition, approximately 20% of HIV-infected children developed depressed LV function or LV dilatation and it is likely that these abnormalities are hallmarks of future clinically important cardiac dysfunction. Cardiac abnormalities were found in both the older (Group I) as well as the neonatal cohort (Group II) (whose HIV infection status was unknown before enrollment) thereby minimizing potential selection bias based on previously known heart disease.

Based on these findings, we recommend that clinicians need to maintain a high degree of suspicion for heart disease in HIV-infected children. All HIV-infected infants and children should have a thorough baseline cardiac evaluation. Patients who develop symptoms of heart or lung disease should undergo more detailed cardiac examinations including ECG and cardiac ultrasound.

The cardiac complications attributed to HIV infection vary, ranging from subclinical electrocardiographic (ECG) changes, to life-threatening cardiomyopathy, and sudden death.1–5 Autopsy studies have documented pathologic cardiac findings in some children with HIV infection.1,6,7 The virus itself has been detected in myocardial cells as well as pericardial fluid in HIV-infected children.3,8 Furthermore, 2 studies have suggested that cardiac disease may be an important prognostic indicator of the severity and the rate of progression of the overall HIV disease itself.2,9

Estimates of the incidence of cardiac disease in HIV-infected children vary widely depending on the methods of ascertainment. A review of HIV-infected children discharged from hospitals in New York State reported a frequency of heart disease of approximately 1%.10 Higher prevalence rates of heart disease, ranging from 14% to 45%, were reported by other investigators,9,11 but may be attributable to selective recruitment and detection bias.

The Pediatric Pulmonary and Cardiac Complications of Vertically Transmitted HIV Infection (P2C2 HIV) Study is a multicenter, National Institutes of Health-sponsored study to determine the incidence of heart and lung disease in children with vertically acquired HIV infection. We have reported that rates of congenital cardiovascular malformations in children exposed to maternal HIV infection are similar to normal populations undergoing similar screening.12 Recently we also reported results of studies indicating abnormalities in left ventricular (LV) function in an older subset of HIV-infected children followed in the P2C2 study (median age at first echocardiogram = 2.1 years).13 The present report carries our investigation further by prospectively observing a population of neonates at risk for vertical transmission of HIV. Inclusion of this second group adds new information concerning the incidence of heart disease in HIV-infected infants and avoids recruitment bias based on known disease that is present in the older cohort. Furthermore, this report expands our observations to include new information from echocardiograms, ECGs, and Holter recordings in both the neonatal cohorts as well as the previously mentioned older cohort.

METHODS

Study Design

Children were enrolled at 5 centers: 1) Baylor College of Medicine/Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston, Texas; 2) Children’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts; 3) Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York; 4) Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center/Babies and Children’s Hospital, New York, New York; and 5) University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California. We prospectively studied 2 cohorts of HIV-infected children. The first group was comprised of infants and children already known to be HIV-infected at the time of enrollment in the study (Group I). The second group included infants born to HIV-infected mothers, enrolled during fetal life or before 28 days of age (Group II). The ultimate HIV status of the Group II infants was unknown at the time of enrollment. The study was approved by the institutional review board at each center and performed after informed consent was obtained. Details of the design of the study have been published.14

Older HIV-Infected Cohort (Group I)

This cohort of 205 children with vertically acquired HIV infection was enrolled between May 1990 and April 1993. The median age was 22 months (range, 0.1–14 years) at the time of enrollment. The HIV status of all Group I patients was known before enrollment in the study. HIV infection was documented in both the mother and child, with no history of sexual abuse or transfusion of blood products in the child.

Neonatal Cohort (Group II)

Group II also consisted of infants born to HIV-infected mothers; however, these subjects were enrolled during fetal life (n = 443) or before 28 days of age (n = 168). Furthermore, as opposed to the children in Group I, the ultimate HIV status of the Group II infants was unknown at the time of enrollment. This cohort entered the study between May 1990 and January 1994.

Documentation of HIV Status

In Group I children, HIV status was determined by the presence of a positive HIV antibody test and/or a positive HIV blood culture. In Group II, HIV infection was defined as 2 positive HIV blood cultures. Infants with 2 negative cultures, with 1 after 5 months of age, were classified as HIV uninfected. Further confirmation of HIV infection status was obtained by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and/or Western blot at a minimum age of 15 months. If mixed results were obtained, the child was classified as indeterminate, until the antibody test could be repeated at a later date. Infants who died or were lost to follow-up before HIV status could be determined remained classified as indeterminate.

Cardiac Studies

According to the study protocol, children underwent a series of cardiac evaluations including two-dimensional echocardiogram and Doppler studies of cardiac function every 4 to 6 months. They also had a 12- or 15-lead surface ECG, 24-hour ambulatory ECG monitoring, and a chest radiograph every 12 months.

Echocardiography

Two-dimensional echocardiograms were performed in a standardized way in 10 pediatric cardiology laboratories at the 5 clinical centers. Subxyphoid, apical, and parasternal views were used to define intracardiac anatomy and to obtain cardiac measurements and indices of cardiac function in a standardized manner. The m-mode strip charts were interpreted at Boston Children’s Hospital providing centralized digitization and measurement of LV size and function. Indices of contractility, LV mass and afterload were previously reported in Group I patients13 and detailed analysis of cardiac function in Group II patients is the focus of a future report.

Among the 600 live births in Group II, 568 had at least 1 echocardiogram. Forty-two of the Group II subjects had no postnatal echocardiogram, including 28 who were lost to follow-up, 8 who died and 6 HIV-uninfected children who were randomized off the study. We excluded LV dimension and function measurements of 109 echocardiograms from 72 children who had segmental LV wall abnormalities or abnormal ventricular septal motion that could possibly affect the LV function measurements. In addition we excluded function studies on 3 children with congenital heart abnormalities including a large atrial septal defect, total anomalous pulmonary venous drainage and 1 child with ventricular septal defect with pulmonary stenosis before surgical repair. Because of these exclusions, no LV function data were available for 3 children in Group I, 2 HIV-infected Group II children and 6 uninfected Group II children. LV measurements were converted to z scores based on a group of 285 normal infants and children analyzed at the Boston Children’s Hospital.13,15 Two specific cut-points were chosen to describe cardiac dysfunction. Children with left ventricular fractional shortening (LV FS) ≤25% were classified as having cardiac dysfunction and those with fractional shortening (FS) <19% were classified with moderate or severe dysfunction. The presence of a pericardial effusion was also documented by echocardiography. A small accumulation of pericardial fluid was defined as noncircumferential and <5 mm in size. Valvar regurgitation was considered to be present if a Doppler color-flow jet was >3 mm in diameter across the valve of interest.

Tachycardia was defined in two ways. ECG tachycardia was defined as a heart rate on surface ECG >98th percentile for age based on criteria published by Davignon and co-workers.16 Echo tachycardia was defined as a heart rate on two-dimensional echocardiogram with a z score >3.15 The ECG heart rates used to define tachycardia based on the 98th percentile from Davignon et al16 were uniformly higher than the heart rates with a z score >3 on echocardiography except for infants during the first month of life. Abnormal ambulatory ECG monitoring was defined as the presence of 1 or more of the following: second or third degree atrioventricular heart block, atrial flutter or fibrillation, or supraventricular or ventricular tachycardia. Chest radiographs were read at each clinical center by a pediatric radiologist specifying the presence or absence of cardiomegaly.17

Management of cardiac abnormalities was not directed by the study, and reflected the individual center’s usual standard of care. The presence of congestive heart failure (CHF) in the study was determined by a pediatric cardiologist at each center. A study protocol modification in March 1994 required that children undergo a standardized P2C2 study physical examination by a pediatric cardiologist if a significant abnormality was suggested by noninvasive testing or if clinically indicated. The diagnosis of CHF was not based on any single laboratory test, but rather, was based on the cardiologist’s assessment of the patient’s clinical and laboratory findings. Some children had echocardiographic abnormalities of LV size and function without a clinical diagnosis of CHF and were treated with cardiac medications. The use of digoxin, furosemide, captopril, enalapril, dobutamine, and nifedipine in the study patients was also tabulated. Because cardiac abnormalities tended to cluster in the same patients, we also determined the number of children who had cardiac impairment which we defined as having either LV FS ≤25%, after 6 months of age, CHF, or who received treatment with cardiac medications.

Quality Control of Clinical Testing

Echocardiograms, ECGs, ambulatory ECGs, chest radiographs, and physical examinations were performed at each of the clinical sites according to the protocol. Two site visits to each center were performed during the early part of the study to assure uniform testing and data collection procedures. Standardized data collection forms were completed with data entered on personal computers at each clinical site and transmitted via modem to the Clinical Coordinating Center at the Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, for analyses. The Clinical Coordinating Center examined data quality and searched for statistical outliers with such cases then returned to the original center for review.

The echocardiographic reports of LV dimensions, LV FS, and heart rate in this report are based on measurements obtained at the central laboratory. Other cardiac findings, including echocardiographic reports of pericardial effusion and valve regurgitation, ECG heart rate for sinus tachycardia, and ambulatory ECG recordings for arrhythmia were determined at each individual site according to the protocol. A sample of chest radiographs was reviewed for quality assurance purposes by the Radiology Committee of the P2C2 study. The observed agreement between radiologists for the diagnosis of cardiac enlargement on chest radiograph was 90.5%.17

All study data were analyzed in a coded fashion to protect the identity of the patient. Because the HIV status of children under 5 months of age was usually unknown, studies before that age were usually blinded to the HIV status of the infant. There was no deliberate attempt to hide the child’s HIV status from the staff obtaining the studies. In contrast, the staff at the central lab was blinded to the HIV status of the child.

Statistical Analysis

The cumulative incidence of an initial episode of selected cardiac complications over the first 2 years of follow-up is presented for both the older HIV-infected cohort (Group I) and the neonatal cohort (Group II). The prevalence of complications at the time of the initial cardiac study among the Group I children is summarized using proportions. After excluding prevalent cases, the 1-and 2-year cumulative incidence of complications are obtained from Kaplan-Meier analyses. Similarly, the cumulative incidence rates for cardiac complications at 1 and 2 years of age are calculated for HIV-infected and uninfected infants from the neonatal cohort (Group II). Complication rates over time of the HIV-infected and uninfected children are compared with 2-sided logrank tests. Ninety-five percent CIs are provided for the 1- and 2-year incidence rates. Kaplan-Meier analyses were also used to estimate the 2-year cumulative death rate and the 1- and 2-year mortality rates after the diagnosis of CHF from each group. χ2 tests were used to compare the frequency of LV dysfunction (LV FS ≤25%) and LV end-diastolic dimension >2 SD between Group I survivors and nonsurvivors. All children remaining on study had completed 2 years of follow-up.

RESULTS

Demographics

Group I consisted of 205 HIV-infected children. Most of the children were African-American or Hispanic and 89% had symptomatic HIV infection at enrollment with immunosuppression (median CD4 cell count and z score = 690 cells/mm3 and −1.92). Of the 611 subjects enrolled in Group II, 600 were live born infants and 11 died in utero. Of the live born infants, 93 became HIV-infected, 463 remained uninfected, and 44 had indeterminate HIV status. There were no systematic differences in gender or race between the Group I and Group II cohorts (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Children in the Older HIV-Infected Cohort (Group I) and Neonatal Cohort (Group II)

| Variable | Older Cohort (Group I)

|

Neonatal Cohort (Group II)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-Infected (n = 205)

|

HIV-Uninfected (n = 463)

|

HIV-Infected (n = 93)

|

||||

| Frequency | % | Frequency | % | Frequency | % | |

| Race | ||||||

| Black non-Hispanic | 89 | 43.4 | 245 | 52.9 | 41 | 44.1 |

| Hispanic | 82 | 40.0 | 138 | 29.8 | 32 | 34.4 |

| White non-Hispanic | 28 | 13.7 | 54 | 11.7 | 15 | 16.1 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| American Indian | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Other | 5 | 2.4 | 25 | 5.4 | 5 | 5.4 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 94 | 45.9 | 249 | 53.8 | 44 | 47.3 |

| Female | 111 | 54.1 | 214 | 46.2 | 49 | 52.7 |

LV FS

In the Group I cohort the prevalence rate of LV dysfunction (FS ≤25%) at the time of the first echocardiogram in the study was 5.7% (Table 2). Excluding prevalent cases, the cumulative incidence of FS ≤25% was 8.4% at 1 year and increased to 15.3% after 2 years of follow-up (Table 2). The 2-year cumulative incidence of moderate-severe cardiac dysfunction (FS <19%) was 3.0%.

TABLE 2.

Kaplan-Meier Results for Cumulative Incidence (Percent) of the Older HIV-Infected Children (Group I) Who Have Had One or More Cardiac Complications at 1 and 2 Years After Enrollment

| Complication | Incidence

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevelance

|

1 Year

|

2 Years

|

||||||||

| Frequency | % | NR | NE | % | 95% CI | NR | NE | % | 95% CI | |

| ↓ FS (≤25%) | 11/193 | 5.7 | 144 | 14 | 8.4 | (4.2, 12.6) | 116 | 24 | 15.3 | (9.6, 21.0) |

| ↓ FS (<19%) | 3/193 | 1.6 | 158 | 4 | 2.3 | (0.1, 4.6) | 133 | 5 | 3.0 | (0.4, 5.6) |

| ↑ LV end-diastolic dimension (z score >2) | 16/192 | 8.3 | 141 | 12 | 7.4 | (3.4, 11.4) | 116 | 18 | 11.7 | (6.6, 16.7) |

| ↑ LV end-systolic dimension (z score >2) | 34/192 | 17.7 | 122 | 19 | 12.9 | (7.5, 18.4) | 92 | 34 | 24.3 | (17.1, 31.4) |

| Cardiomegaly (x-ray) | 28/201 | 13.9 | 133 | 17 | 10.8 | (6.0, 15.7) | 102 | 29 | 19.3 | (12.9, 25.6) |

| Pericardial effusion (≥5 mm maximal diameter) | 0/201 | 0.0 | 167 | 1 | 0.5 | (0.0, 1.6) | 139 | 2 | 1.2 | (0.0, 2.9) |

| Tachycardia (ECG) | 19/201 | 9.5 | 129 | 14 | 9.2 | (4.6, 13.8) | 109 | 22 | 15.1 | (9.3, 21.0) |

| ↑ Heart rate (echocardiogram) (z score >2) | 41/196 | 20.9 | 100 | 42 | 29.0 | (21.6, 36.4) | 67 | 66 | 46.8 | (38.5, 55.2) |

| ↑ Heart rate (echocardiogram) (z score >3) | 14/196 | 7.1 | 140 | 20 | 12.1 | (7.1, 17.1) | 112 | 36 | 22.5 | (16.0, 29.0) |

| Abnormal Holter monitor | 4/189 | 2.1 | 125 | 4 | 3.0 | (0.1, 5.8) | 103 | 5 | 3.8 | (0.5, 7.0) |

| Mitral valve regurgitation | 3/201 | 1.5 | 159 | 8 | 4.5 | (1.4, 7.5) | 130 | 10 | 5.7 | (2.3, 9.2) |

| Tricuspid valve regurgitation | 3/201 | 1.5 | 164 | 2 | 1.2 | (0.0, 2.7) | 133 | 8 | 5.1 | (1.7, 8.6) |

| Aortic valve regurgitation | 2/201 | 1.0 | 165 | 0 | 0.0 | – | 139 | 0 | 0.0 | – |

| Pulmonic valve regurgitation | 0/201 | 0 | 165 | 2 | 1.1 | (0.0, 2.7) | 136 | 6 | 3.8 | (0.8, 6.8) |

| CHF and/or cardiac medications | 9/201 | 4.5 | 160 | 10 | 5.6 | (2.2, 9.0) | 134 | 17 | 10.0 | (5.5, 14.5) |

| Cardiac impairment | 14/201 | 7.0 | 152 | 14 | 8.1 | (4.0, 12.2) | 118 | 31 | 19.1 | (13.0, 25.2) |

NR, number of children still being followed who have not had the complication.

NE, number of children being followed at that time who have had the complication.

%, Percent of children who have had a complication on or before the specified time.

95% CI, 95% CI for the estimated percentage.

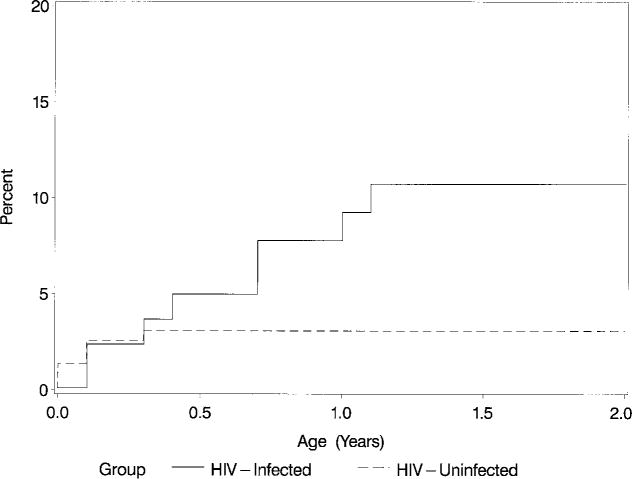

Within Group II, HIV-infected children had a cumulative incidence of LV dysfunction (FS ≤25%) of 10.7% at 2 years of age, significantly greater than the 3.1% cumulative incidence rate in the uninfected group (P = .01) (Table 3 and Fig 1). There was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of moderate-severe LV dysfunction (FS <19%) between HIV-infected and uninfected infants (1.4% and 0.2%), respectively.

TABLE 3.

Kaplan-Meier Results for Cumulative Incidence (Percent) of the Neonatal Cohort (Group II) Who Have Had One or More Cardiac Complications at 1 and 2 Years

| Complication | Age (Years) |

Incidence

|

P Value (From Log-Rank Test) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-Infected (n = 93)

|

HIV-Uninfected (n = 463)

|

|||||||||

| NR | NE | % | 95% CI | NR | NE | % | 95% CI | |||

| ↓ FS (≤25%) | 1 | 65 | 6 | 7.8 | (1.8, 13.8) | 269 | 13 | 3.1 | (1.4 4.7) | .01 |

| 2 | 57 | 8 | 10.7 | (3.7, 17.8) | 161 | 13 | 3.1 | (1.4, 4.7) | ||

| ↓ FS (<19%) | 1 | 69 | 1 | 1.4 | (0.0, 4.1) | 274 | 1 | 0.2 | (0.0, 0.6) | NS |

| 2 | 62 | 1 | 1.4 | (0.0, 4.1) | 165 | 1 | 0.2 | (0.0, 0.6) | ||

| ↑ LV end-diastolic dimension (z score >2) | 1 | 68 | 2 | 2.6 | (0.0, 6.1) | 270 | 8 | 2.1 | (0.6, 3.5) | .02 |

| 2 | 57 | 6 | 8.7 | (2.0, 15.4) | 162 | 8 | 2.1 | (0.6, 3.5) | ||

| ↑ LV end-systolic dimension (z score >2) | 1 | 56 | 20 | 24.5 | (15.1, 33.9) | 247 | 43 | 10.7 | (7.6, 13.7) | <.001 |

| 2 | 45 | 27 | 34.3 | (23.7, 44.9) | 144 | 46 | 12.1 | (8.7, 15.5) | ||

| Cardiomegaly (x-ray) | 1 | 68 | 11 | 13.8 | (6.2, 21.4) | 230 | 5 | 1.4 | (0.2, 2.7) | <.001 |

| 2 | 49 | 22 | 28.3 | (18.2, 38.3) | 26 | 11 | 6.9 | (2.1, 11.8) | ||

| Pericardial effusion (≥5 mm maximal diameter) | 1 | 76 | 1 | 1.3 | (0.0, 3.7) | 284 | 1 | 0.3 | (0.0, 0.9) | NS |

| 2 | 65 | 1 | 1.3 | (0.0, 3.7) | 178 | 2 | 0.9 | (0.0, 2.1) | ||

| Tachycardia (ECG) | 1 | 62 | 16 | 19.5 | (10.9, 28.0) | 226 | 41 | 12.3 | (8.7, 15.9) | NS |

| 2 | 48 | 22 | 27.7 | (17.8, 37.7) | 128 | 60 | 21.3 | (16.2, 26.3) | ||

| ↑ Heart rate (echocardiogram) (z score >2) | 1 | 50 | 31 | 37.0 | (26.6, 47.4) | 247 | 50 | 12.6 | (9.3, 15.9) | <.001 |

| 2 | 42 | 37 | 44.7 | (33.9, 55.5) | 140 | 66 | 20.1 | (15.5, 24.8) | ||

| ↑ Heart rate (echocardiogram) (z score >3) | 1 | 65 | 11 | 13.5 | (6.1, 21.0) | 273 | 11 | 2.7 | (1.1, 4.3) | <.001 |

| 2 | 53 | 17 | 22.0 | (12.7, 31.3) | 161 | 15 | 4.9 | (2.3, 7.5) | ||

| Abnormal Holter monitor | 1 | 60 | 2 | 2.5 | (0.0, 5.9) | 171 | 8 | 3.0 | (0.9, 5.1) | NS |

| 2 | 47 | 3 | 4.3 | (0.0, 9.1) | 92 | 9 | 3.7 | (1.2, 6.2) | ||

| Mitral valve regurgitation | 1 | 76 | 0 | 0.0 | – | 285 | 0 | 0.0 | – | NS |

| 2 | 65 | 0 | 0.0 | – | 180 | 0 | 0.0 | – | ||

| Tricuspid valve regurgitation | 1 | 76 | 0 | 0.0 | – | 282 | 4 | 1.1 | (0.0, 2.1) | NS |

| 2 | 64 | 1 | 1.5 | (0.0, 4.3) | 176 | 8 | 2.8 | (0.8, 4.8) | ||

| Aortic valve regurgitation | 1 | 76 | 0 | 0.0 | – | 283 | 4 | 1.1 | (0.0, 2.1) | NS |

| 2 | 64 | 1 | 1.5 | (0.0, 4.3) | 176 | 6 | 2.1 | (0.3, 3.9) | ||

| Pulmonic valve regurgitation | 1 | 75 | 1 | 1.3 | (0.0, 3.9) | 284 | 3 | 0.9 | (0.0, 1.9) | NS |

| 2 | 63 | 2 | 2.7 | (0.0, 6.4) | 180 | 3 | 0.9 | (0.0, 1.9) | ||

| CHF and/or cardiac medications | 1 | 69 | 6 | 7.4 | (1.7, 13.2) | 287 | 2 | 0.5 | (0.0, 1.2) | <.001 |

| 2 | 61 | 7 | 8.8 | (2.6, 15.0) | 185 | 2 | 0.5 | (0.0, 1.2) | ||

| Cardiac impairment | 1 | 67 | 8 | 10.1 | (3.5, 16.8) | 287 | 2 | 0.5 | (0.0, 1.2) | <.001 |

| 2 | 58 | 10 | 12.8 | (5.4, 20.3) | 185 | 2 | 0.5 | (0.0, 1.2) | ||

NR, number of children still being followed who have not had the complication.

NE, number of children being followed at that time who have had the complication.

%, Percent of children who have had a complication on or before the specified time.

95% CI, 95% CI for the estimated percentage.

Fig 1.

Kaplan-Meier cumulative incidence (%) of an initial episode of decreased LV FS (≤25%) in HIV-infected and noninfected children over the first 2 years of life (P = .01; log-rank test).

The 2-year cumulative incidence of LV FS ≤25% remained similar when children with abnormal segmental wall motion were included in the analyses; 15.6% in Group I and 10.6% in Group II infected children compared with 3.1% (unchanged) in Group II uninfected children (P = .01).

Cardiac Size

Increased cardiac size was assessed by two methods: 1) echocardiographic measurement of LV size, and 2) cardiac size on chest radiograph as read by a pediatric radiologist. In Group I, the prevalence of echocardiographic LV enlargement (LV end-diastolic dimension z score >2) at the time of the first echocardiogram was 8.3%. The cumulative incidence of LV end-diastolic enlargement was 11.7% after 2 years (Table 2). The prevalence of LV end-systolic enlargement (z score >2) was 17.7% and the 2-year cumulative incidence of LV end-systolic enlargement was 24.3%.

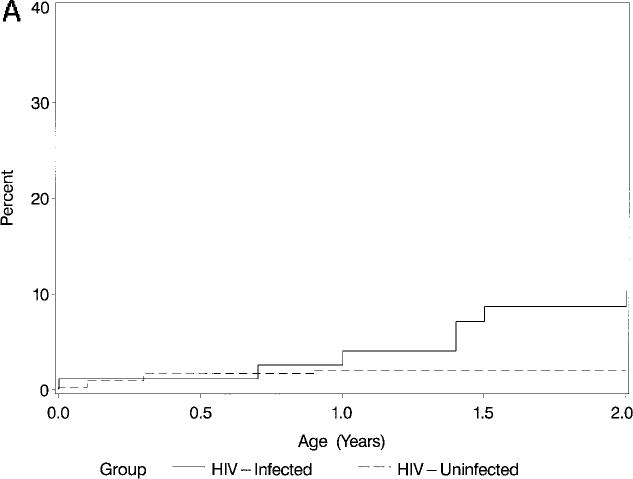

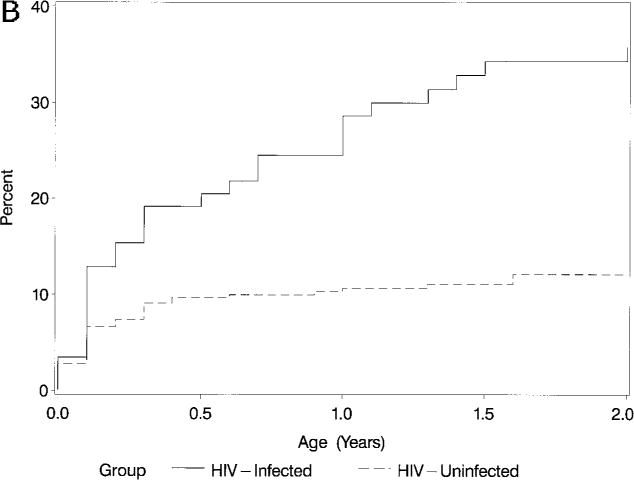

Within Group II, after 2 years of follow-up, the incidence of increased LV end-diastolic dimension (z score >2) was 8.7% in the infected infants versus 2.1% in the uninfected infants (P = .02; Table 3; Fig 2A). The 2-year cumulative incidence of LV endsystolic enlargement was also higher in infected children (34.3%) versus uninfected children (12.1%; P < .001; Table 3 and Fig 2B).

Fig 2A.

Kaplan-Meier cumulative incidence (%) of an initial episode of increased LV enddiastolic dimension (z score >2) in HIV-infected and noninfected children over the first 2 years of life (P = .02; log-rank test).

Fig 2B.

Kaplan-Meier cumulative incidence (%) of an initial episode of increased LV endsystolic dimension (z score >2) in HIV-infected and noninfected children over the first 2 years of life (P < .001; log-rank test).

The prevalence of cardiomegaly on chest radiographs at the time of enrollment in the Group I cohort was 13.9% and after 2 years of follow-up the cumulative incidence was 19.3% (Table 2). In Group II, the 2-year cumulative incidence of cardiomegaly on chest radiograph was 28.3% in the infected group, versus 6.9% in the uninfected group (P < .001; Table 3).

Pericardial Effusion

In the Group I cohort, the 2-year cumulative incidence of a small pericardial effusion (<5 mm maximal diameter) was 24.5%, but a larger effusion was observed in only 1.2%. In the Group II subjects, two-dimensional echocardiography identified a small accumulation of pericardial fluid in both HIV-infected (23.3%) as well as HIV-uninfected infants (26.3%) (data not shown). The 2-year cumulative incidence of a larger pericardial effusion (≥5 mm) was 1.3% in the Group II HIV-infected children versus 0.9% in the uninfected children (P = .61). There were no episodes of tamponade in either Group I or II.

Sinus Tachycardia

The incidence of elevated heart rates was assessed by two different methods, standard ECG and heart rate obtained during the echocardiogram. In Group I children, the prevalence of sinus tachycardia on ECG was 9.5% and the 2-year cumulative incidence was 15.1%. In Group II infants, the 2-year cumulative incidence of tachycardia on ECG was 27.7% in the HIV-infected group and 21.3% in the Group II uninfected children (P = .33).

In Group I children, the prevalence of an elevated heart rate on echocardiogram (z score >3) was 7.1%. The 2-year cumulative incidence of an elevated heart rate on the echocardiogram (z score >3) was 22.5%. In Group II children, elevated heart rates (z score >3) were observed in 22.0% of infected children versus 4.9% in the uninfected children (P < .001). There was no significant difference in the incidence of arrhythmias observed on ambulatory ECG monitoring between the Group II infected and uninfected children.

Valve Regurgitation

In Group I the 2-year cumulative incidence of Doppler evidence of mitral valve regurgitation was 5.7% and 5.1% for tricuspid regurgitation. Valvar regurgitation was rare in Group II children and no significant differences in the incidence of mitral, tricuspid, pulmonary, or aortic valve regurgitation were observed between the infected and uninfected groups (Table 3). No patient had known endocarditis during the 2-year follow-up period.

CHF

In Group I, 2 children had CHF on enrollment in the study and 8 others developed CHF during the 2-year observation period and, as we previously reported, the 2-year cumulative incidence of CHF was 4.7%.13 The median age at diagnosis of CHF was 22 months (range, 8 to 128 months). An additional 18 children received cardiac medications for a diagnosis of cardiomyopathy (n = 9), LV dysfunction (n = 7) or hypertension (n = 2), without having a specific diagnosis of CHF. The 2-year cumulative incidence of CHF and/or treatment with cardiac medications was 10% (Table 2).

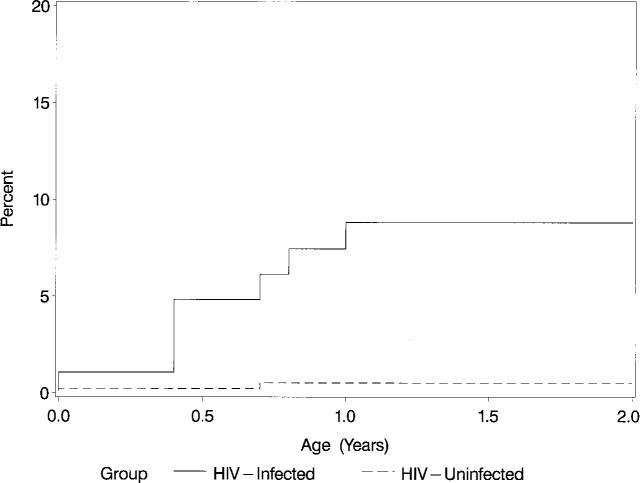

In the Group II infected infants, 4 cases of CHF occurred and the 2-year cumulative incidence was 5.1%. Three additional HIV-infected Group II patients received cardiac medications without a specific diagnosis of CHF, including cardiomyopathy (n = 1), LV dysfunction (n = 1), and hypertension (n = 1). Two HIV-negative infants received cardiac medications, 1 for treatment of a ventricular septal defect and 1 for depressed LV FS (Fig 3).

Fig 3.

Kaplan-Meier cumulative incidence (%) of an initial episode of CHF and/or use of cardiac medications in HIV-infected and noninfected children over the first 2 years of life (P < .001; log-rank test).

Cardiac Impairment, Mortality, and Cardiac Abnormalities

We calculated the cumulative incidence of cardiac impairment defined as either LV FS ≤25% after 6 months of age, CHF, or being listed as receiving cardiac medications. There were 14 prevalent cases of cardiac impairment in Group I, of whom 6 (42.9%) had decreased LV function (FS ≤25%) plus CHF and/or had been prescribed cardiac medications. After excluding these prevalent cases, the 2-year cumulative incidence of cardiac impairment was 19.1% among Group I children and 80.9% remained free of cardiac impairment after 2 years of follow-up. The 1-and 2-year cumulative incidence of cardiac impairment for Group II infected children was 10.1% and 12.8%, respectively, with 87.2% free of cardiac impairment during the first 2 years of life.

In the Group I cohort, the 2-year cumulative death rate from all causes was 16.9% [95% CI: 11.7%–22.1%]. Of the 10 Group I children with CHF, 8 died during the 2-year observation period and 2 others died within 2 years of the diagnosis of CHF. The 1- and 2-year mortality rates after the diagnosis of CHF (Kaplan-Meier estimates) were 69% and 100%, respectively. Cardiomyopathy was the underlying or contributing cause of death in 8 children. When the 31 Group I children who died in the 2-year observation period were compared with those who survived, the frequency of ever having LV dysfunction (LV FS ≤25%) was 51.6% (16/31) in those who died, compared with 11.1% (18/162) in the survivors (χ2; P < .001). Similarly, the frequency of ever having LV end-diastolic dimension >2 SD was 40.0% among those who died and 11.7% among survivors of the 2-year period (P < .001).

In the Group II cohort, the 2-year cumulative death rate from all causes was 16.3% [95% CI: 8.8%–23.9%] in the HIV-infected children compared with no deaths among the 463 uninfected Group II children. Two of the 4 Group II children with CHF died during the 2-year observation period and 1 more died within 2 years of the diagnosis of CHF. The 2-year mortality rate after the diagnosis of CHF was 75%. Cardiomyopathy was a contributing cause of death in 1 child.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that both clinical and subclinical cardiac abnormalities are common in children with HIV infection. During a 2-year observation period, echocardiographic evidence of depressed LV FS was observed in 15.1% of the older HIV-infected cohort (Group I) and 10.2% of the HIV-infected neonatal cohort (Group II). Decreased function and cardiac abnormalities were more common in HIV-infected children compared with a group of uninfected children born to HIV-infected mothers. These abnormalities assume clinical importance as evidenced by the fact that the proportion of children with CHF or receiving treatment with cardiac medications was significantly higher in the HIV-infected compared with the HIV uninfected group. In addition, children who died had more cardiac abnormalities than those who survived the 2-year period of observation.

We have recently reported that the mean LV FS z score in the older HIV Group I cohort was −0.90 and decreased to −1.32 after 2 years suggesting that subclinical abnormalities of LV function were common in older HIV-infected children.13 The current report extends those observations regarding depressed LV function and cardiac dilatation to include a newborn cohort, as well as additional data on older children with HIV infection. Our previous report described statistical evidence of cardiac dysfunction in the older HIV-infected Group I children in terms of abnormal z scores for LV function. We reported that, as a group, their average FS was below normal, (z score −0.90) suggesting that cardiac dysfunction is common.13 In this report we describe the incidence of a clinically defined endpoint for low LV FS (LV FS ≤25%) a value that has been associated with clinical symptoms of CHF in HIV-infected children.18 An LV FS of 25% would correspond to a z score of −5.3 and −4.3 for 1- and 5-year-old children, respectively. A total of 10% to 15% of our HIV-infected children had LV FS below this clinical cutpoint. This new report suggests that not only is the average LV FS lower than normal in HIV-infected children as previously reported,13 but that approximately 10% to 15% of children also have evidence of cardiac dysfunction that is associated with clinical heart failure.

Recent estimates of the incidence of heart disease based on hospital diagnostic codes suggest that 1.2% of HIV-infected children have either cardiomegaly, cor pulmonale, cardiomyopathy, myocarditis or arrhythmia, and 0.8% have CHF.10 Our prospective study describes higher 2-year cumulative incidence rates of cardiac dysfunction that are similar to retrospective findings of others. However, strict comparisons between reports are difficult because of the varying definitions of cardiomyopathy, cardiomegaly, and heart failure used by various investigators. Domanski et al11 reported a cardiomyopathy, (defined as a FS <25%), in 14% of older HIV-infected children and Luginbuhl et al2 described chronic CHF in 10% and transient CHF in an additional 10% of HIV-infected children. Relying solely on hospital coding and clinical summaries may underreport mild cases or those children with an occult cardiomyopathy. Our incidence rates are based on prospective follow-up of well-defined cohorts of children, with uniform testing methods and are likely to give more reliable estimates of the incidence of cardiac disease than retrospective studies.

Small accumulations of pericardial fluid were common in both cohorts. These small effusions (<5 mm in size) appear clinically insignificant and likely represent variants of normal findings. The presence of larger effusions was <2% in this study. Although tamponade has been described in children with HIV infection,3,19 it did not occur during the 2-year follow-up in our study.

Elevated heart rates were observed in both groups of infected children. At the time of echocardiography, the Group II infected infants had a statistically significant greater incidence of faster heart rates than the uninfected children. On ECG, although the trend was similar, the differences were not statistically significant. This may be in part attributable to the different criteria for elevated heart rate, especially in the first month of life.

Our study demonstrates that cardiac abnormalities may be an important marker for death in HIV-infected children, and confirms a previously noted association.2,9 The prognostic value of cardiac abnormalities is not always clear, however. In 1 adult study, several HIV-infected patients had reversible echocardiographic abnormalities.20 In our study, not all the children with cardiac dysfunction died during the 2 years of observation and several succumbed to noncardiac causes. Nevertheless, the onset of cardiac abnormalities identifies individuals in need of closer observation.

The cause of the cardiac changes in HIV is unknown and is likely to be multifactorial. Cardiac dysfunction may be directly attributable to HIV, a complication of a secondary viral or bacterial infection, or related to treatment with antiretroviral agents.21 Zidovudine may be cardiotoxic,21 and Domanski et al11 showed that the odds of developing a cardiomyopathy were increased in children receiving zidovudine. In contrast, Lipshultz et al22 found no change in cardiac contractility comparing zidovudine and non-zidovudine treated children. Further analyses to identify the relationship between zidovudine and cardiac disease in the P2C2 study cohorts are currently in progress.

Our study, with its systematic assessments of cardiac status with ECGs and echocardiograms, was unlikely to miss evidence of significant chronic heart disease. Although the study design encouraged cardiac testing for children with intercurrent illness, there may have been incomplete testing of children with an acute illness or just before death. Several children died in hospice care or in circumstances that precluded additional cardiac testing and our study may have underestimated the overall incidence of cardiac conditions. Diagnosis of CHF may be difficult in children with HIV infection because of other diseases that can also cause tachycardia, tachypnea, and hepatomegaly. A clinical diagnosis of CHF depends on the judgment and interpretation of the caregiver. Therefore, assignment of this diagnosis may have not been uniform.

CONCLUSION

In summary, this study reports that in addition to subclinical cardiac abnormalities previously reported,13 a significant number of HIV-infected children develop clinical heart disease. Over a 2-year period, approximately 10% of HIV-infected children had CHF or were treated with cardiac medications. In addition, approximately 20% of HIV-infected children developed depressed LV function or LV dilatation, and it is likely that these abnormalities are hallmarks of future clinically important cardiac dysfunction. Cardiac abnormalities were found in both the older (Group I) as well as the neonatal cohort (Group II); (whose HIV infection status was unknown before enrollment) thereby minimizing potential selection bias based on previously known heart disease. Based on these findings, we recommend that clinicians need to maintain a high degree of suspicion for heart disease in HIV-infected children. All HIV-infected infants and children should have a thorough baseline cardiac evaluation. Patients who develop symptoms of heart or lung disease should undergo more detailed cardiac examinations including ECG and cardiac ultrasound.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Contracts NO1-HR-96037, NO1-HR-96038, NO1-HR-96039, NO1-HR-96040, NO1-HR- 96041, NO1-HR-96042, and NO1-HR-96043; and in part by the National Institutes of Health Grants RR-00865, RR-00188, RR-02172, RR-00533, RR-00071, RR-00645, RR-00685, and RR-00043.

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of the many nursing, medical, and clerical personnel who participated in making this project possible. In addition, we would like to thank the patients and their families for participating in the study.

ABBREVIATIONS

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- ECG

electrocardiogram

- P2C2

Pediatric Pulmonary and Cardiac Complications of Vertically Transmitted HIV Infection Study

- LV

left ventricular

- LV FS

left ventricular fractional shortening

- CHF

congestive heart failure

APPENDIX

A partial listing of participants in the P2C2 HIV Study is listed below. For a full list, see reference 14. The superior letter a indicates that this person is a Principal Investigator.

NATIONAL HEART, LUNG AND BLOOD INSTITUTE

Hannah Peavy, MD, (Project Officer), Anthony Kalica, PhD, Elaine Sloand, MD, George Sopko, MD, MPH, Margaret Wu, PhD CHAIRMAN OF THE STEERING COMMITTEE: Robert Mellins, MD

CLINICAL CENTERS

Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

William Shearer, MD, PhD,a Nancy Ayres, MD, J. Timothy Bricker, MD, Arthur Garson, MD, Debra Kearney, MD, Achi Ludomirsky, MD, Linda Davis, RN, BSN, Paula Feinman, Mary Beth Mauer, RN, BSN, Debra Mooneyham, RN, Teresa Tonsberg, RN

The Children’s Hospital, Boston/Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

Steven Lipshultz, MD,a Steven Colan, MD, Lisa Hornberger, MD, Antonio Perez-Atayde, MD, Stephen Sanders, MD, Marcy Schwartz, MD, Helen Donovan, Janice Hunter, MS, RN, Karen Lewis, RN, Ellen McAuliffe, BSN, Patricia Ray, BS, Sonia Sharma, BS

Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY

Meyer Kattan, MD,a Wyman Lai, MD, Samuel Ritter, MD, Debbie Benes, MS, RN, Diane Carp, MSN, RN, Donna Lewis, Sue Mone, MS, Mary Ann Worth, RN

Presbyterian Hospital in the City of New York/Columbia University, New York, NY

Robert Mellins, MD,a Fred Brierman, MD,a (through 5/91), Thomas Starc, MD, Walter Berdon, MD, Anthony Brown, Margaret Challenger, Kim Geromanos, MS, RN

UCLA School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA

Samuel Kaplan, MD,a Y. Al-Khatib, MD, Robin Doroshow, MD, Arno Hohn, MD, Joephine Isabel-Jones, MD, Barry Marcus, MD, Roberta Williams, MD, Helene Cohen, PNP, RN, Lynn Fukushima, MSN, RN, Audrey Gardner, BS, Sharon Golden, RDMS, Lucy Kunzman, RN, MS, CPNP, Karen Simandle, RDMS, Ah-Lin Wong, RDMS, Toni Ziolkowski, RN, MSN

CLINICAL COORDINATING CENTER

The Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, OH

Michael Kutner, PhD,a Mark Schluchter, PhD (through 4/98), Johanna Goldfarb, MD, Douglas Moodie, MD, Cindy Chen, MS, Kirk Easley, MS, Scott Husak, BS, Victoria Konig, ART, Paul Sartori, BS, Lori Schnur, BS, Amrik Shah, ScD, Sharayu Shanbhag, BSc, Susan Sunkle, BA, CCRA

POLICY, DATA AND SAFETY MONITORING BOARD

Henrique Rigatto, MD, (Chairman), Edward B. Clark, MD, Robert B. Cotton, MD, Vijay V. Joshi, MD, Paul S. Levy, ScD, Norman S. Talner, MD, Patricia Taylor, PhD, Robert Tepper, MD, PhD, Janet Wittes, PhD, Robert H. Yolken, MD, Peter E. Vink, MD

Footnotes

This study was presented in part at the Society for Pediatric Research, May 10, 1995; San Diego, CA.

Principal Investigator.

References

- 1.Lipshultz SE, Chanock S, Sanders SP, Colan SD, Perez-Atayde A, McIntosh K. Cardiac manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus infection in infants and children. Am J Cardiol. 1989;63:1489–1497. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luginbuhl LM, Orav EJ, McIntosh K, Lipshultz SE. Cardiac morbidity and related mortality in children with HIV infection. JAMA. 1993;269:2869–2875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kovacs A, Hinton DR, Wright D, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of the heart in three infants with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and sudden death. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15:819–824. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199609000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steinherz LJ, Brochstein JA, Robins J. Cardiac involvement in congenital acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Dis Child. 1986;140:1241–1244. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1986.02140260043022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart JM, Kaul A, Gromisch DS, Reyes E, Woolf PK, Gewitz MH. Symptomatic cardiac dysfunction in children with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Am Heart J. 1989;117:140–144. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(89)90668-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bharati S, Joshi VV, Connor EM, Oleske JM, Lev M. Conduction system in children with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Chest. 1989;96:406–413. doi: 10.1378/chest.96.2.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Voyter TM, Joshi VV. Cardiac pathology of pediatric HIV infection. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 1997;7:7–18. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lipshultz SE, Fox CH, Perez-Atayde AR, et al. Identification of human immunodeficiency virus-1 RNA and DNA in the heart of a child with cardiovascular abnormalities and congenital acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 1990;66:246–250. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90603-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grenier MA, Karr SS, Rakusan TA, Martin GR. Cardiac disease in children with HIV: relationship of cardiac disease to HIV symptomatology. Pediatric AIDS and HIV Infection: Fetus to Adolescent. 1994;5:174–179. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turner BJ, Denison M, Eppes SC, Houchens R, Fanning T, Markson LE. Survival experience of 789 children with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1993;12:310–320. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199304000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Domanski MJ, Sloas MM, Follmann DA, et al. Effect of zidovudine and didanosine treatment on heart function in children infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J Pediatr. 1995;127:137–146. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(95)70275-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lai WW, Lipshultz SE, Easley KA, et al. Prevalence of congenital cardiovascular malformations in children of human immunodeficiency virus-infected women. The prospective P2C2 HIV multicenter study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:1749–1755. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00449-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lipshultz SE, Easley KA, Orav EJ, et al. Left ventricular structure and function in children infected with human immunodeficiency virus. The prospective P2C2 HIV multicenter study. Circulation. 1998;97:1246–1256. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.13.1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The P2C2 HIV Study Group. The pediatric pulmonary and cardiovascular complications of vertically transmitted human immunodeficiency virus (P2C2 HIV) infection study: design and methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1285–1294. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00230-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colan SD, Parness IA, Spevak PJ, Sanders SP. Developmental modulation of myocardial mechanics: age-and-growth-related alterations in afterload and contractility. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;19:619–629. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80282-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davignon A, Rautaharju P, Boisselle E, Soumis F, Megelas M, Choquette A. Normal ECG standards for infants and children. Pediatr Cardiol. 1979;1:123–131. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cleveland RB, Schluchter M, Wood BP, et al. Chest radiographic data acquisition and quality assurance in multicenter studies. Pediatr Radiol. 1997;27:880–887. doi: 10.1007/s002470050262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lipshultz SE, Orav EJ, Sanders SP, McIntosh K, Colan SD. Limitations of fractional shortening as an index of contractility in pediatric patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J Pediatr. 1994;125:563–570. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(94)70008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mast HL, Haller JO, Schiller MS, Anderson VM. Pericardial effusion and its relationship to cardiac disease in children with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Pediatr Radiol. 1992;22:548–551. doi: 10.1007/BF02013013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blanchard DG, Hagenhoff C, Chow LC, McCann HA, Dittrich HC. Reversibility of cardiac abnormalities in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected individuals: a serial echocardiographic study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:1270–1276. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80134-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herskowitz A, Willoughby SB, Baughman KL, Schulman SP, Bartlett JD. Cardiomyopathy associated with antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection: a report of six cases. Ann Intern Med. 1992;16:311–313. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-4-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lipshultz SE, Orav EJ, Sanders SP, Hale AR, McIntosh K, Colan SD. Cardiac structure and function in children with human immunodeficiency virus infection treated with zidovudine. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1260–1265. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199210293271802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]