Abstract

The role of IL-1β and IL-18 during lung infection with the gram-negative bacterium Francisella tularensis LVS has not been characterized in detail. Here, using a mouse model of pneumonic tularemia, we show that both cytokines are protective, but through different mechanisms. Il-18-/- mice quickly succumb to the infection and showed higher bacterial burden in organs and lower level of IFNγ in BALF and serum compared to wild type C57BL/6J mice. Administration of IFNγ rescued the survival of Il-18-/- mice, suggesting that their decreased resistance to tularemia is due to inability to produce IFNγ. In contrast, mice lacking IL-1 receptor or IL-1β, but not IL-1α, appeared to control the infection in its early stages, but eventually succumbed. IFNγ administration had no effect on Il-1r1-/- mice survival. Rather, Il-1r1-/- mice were found to have significantly reduced titer of Ft LPS-specific IgM. The anti-Ft LPS IgM was generated in a IL-1β-, TLR2-, and ASC-dependent fashion, promoted bacteria agglutination and phagocytosis, and was protective in passive immunization experiments. B1a B cells produced the anti-Ft LPS IgM and these cells were significantly decreased in the spleen and peritoneal cavity of infected Il-1b-/- mice, compared to C57BL/6J mice. Collectively, our results show that IL-1β and IL-18 activate non-redundant protective responses against tularemia and identify an essential role for IL-1β in the rapid generation of pathogen-specific IgM by B1a B cells.

Author Summary

Francisella tularensis is a Gram-negative bacterium that infects macrophages and other cell types causing tularemia. F. tularensis is considered a potential bioterrorism agent and is a prime model intracellular bacterium to study the interaction of pathogens with the host immune system. The role of the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 during lung infection with F. tularensis has not been characterized in detail. Here, using a mouse model of pneumonic tularemia, we show that both cytokines are protective, but through different mechanisms. Mice deficient in IL-18 quickly succumbed to the infection but administration of IFNγ rescued their survival. In contrast, mice lacking IL-1β appeared to control the infection in its early stages, but eventually succumbed and were not rescued by administration of IFNγ. Rather, IL-1β-deficient mice had significantly reduced serum level of IgM antibodies specific for F. tularensis LPS. These antibodies were generated in a IL-1β-, TLR2-, and ASC-dependent fashion, promoted bacteria agglutination and phagocytosis, and were protective in passive immunization experiments. B1a B cells produced the anti-F. tularensis IgM and were significantly decreased in the spleen and peritoneal cavity of infected IL-1β-deficient mice. Collectively, our results show that IL-1β and IL-18 activate non-redundant protective responses against tularemia and identify an essential role for IL-1β in the rapid generation of pathogen-specific IgM by B1a B cells.

Introduction

Francisella tularensis (Ft) is a Gram-negative bacterium that infects macrophages and other cell types causing tularemia [1]. Ft is considered a potential bioterrorism agent and is used as a prime model intracellular bacterium to study the strategies adopted by microbes to evade and minimize innate immune detection.

Although the innate immune response to Ft infection has been examined in a great number of publications (reviewed in [2] [3]), much remains to be learned. Ft is known to evade various host defense mechanisms [4] and to produce an atypical LPS that does not stimulate TLR4 and does not possess proinflammatory activity [5] [6] [7,8] [9]. However, like others, we have shown that Ft stimulates a proinflammatory response primarily through TLR2 [10] [11] [12], which recognizes Ft lipoproteins [13]. The other innate immune pathway preferentially stimulated by Ft in mice is the inflammasome composed of AIM2-ASC-caspase-1 [14]. It is believed that genomic DNA released by lysing bacteria localized in the cytosol activates this inflammasome, leading to secretion of IL-1β and IL-18 and death of the infected cells by pyroptosis. This form of caspase-1-dependent cell death has been shown to effectively restrict intracellular replication of several bacteria, including Ft, by exposing them to extracellular microbicidal mechanisms [15]. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in human macrophages has also been reported [16]. Whether this inflammasome is also activated in mice is unclear.

IL-1β and IL-18 are powerful proinflammatory cytokines that have been shown to be protective in a large number of experimental infection models. Both cytokines signal through the MyD88 pathway but elicit varied responses in different cell types [17]. Despite intensive research on Ft, the role of IL-1β and IL-18 during lung infection with this bacterium has not been characterized in detail. A confounding factor that affects the tularemia research field is that the majority of the studies are performed using either of two Francisella subspecies, F. novicida or Ft live vaccine strain (LVS), which are pathogenic in mice, but not humans, and differentially engage innate immune responses [1] [18]. An additional strain, the virulent Ft type A SchuS4 strain, displays an exaggerated virulence in mice, which has severely limited its use for the genetic analysis of the host immune response to this infection. A further complication in the analysis, comparison, and interpretation of the studies on tularemia, is that different routes of infection (i.p., i.d., i.n.) are used, which determine the severity of disease, and the relative contribution to protection of various immune pathways [19] [20]. For our studies we decided to use LVS because of its potential use as prophylactic vaccine and we adopted the intranasal infection route because it is the most lethal and the most relevant to biodefense.

Early evidence that IL-1β and IL-18 played protective roles during infection with Francisella species was provided by studies of Denise Monack’s group that showed that intraperitoneal injection of neutralizing antibodies against IL-18 and IL-1β increased bacterial burdens in mice infected intradermaly with F. novicida [21]. The same group showed that mice deficient in both IL-1β /IL-18 are more susceptible than C57BL/6J mice, yet not as much as mice deficient in ASC or caspase-1, suggesting that other caspase-1-dependent pathways, most likely pyroptosis, significantly contributed to protection from infection [14]. Collazo et al. analyzed Il-1r1 -/- and Il-18 -/- mice infected intradermally with Ft LVS, but did not find significant differences in the survival of these mice, compared to C57BL/6J mice [22]. Collectively, these studies indicated that IL-1β and IL-18 may contribute to protection from tularemia but it remains unclear to what extent, through which mechanism, and under which conditions. Despite the uncertainties about the role of IL-1β and IL-18 during Ft infection, several groups, including ours, have shown that Ft mutants that hyper-activate the inflammasome leading to increased IL-1β and IL-18 secretion are attenuated in vivo [23] [24] [25] [26,27], suggesting that these cytokines in fact play a protective role in tularemia.

The studies described here analyzed for the first time the response of IL-1- or IL-18-deficient mice to intranasal infection with Ft LVS. Our results demonstrate that different protective mechanisms are activated by IL-18 and IL-1β and reveal a critical role for IL-1β in the production of anti-Ft LPS IgM by B1a B cells.

Results

Different susceptibility of Il-1r1 -/- and Il-18 -/- mice to Ft LVS lung infection

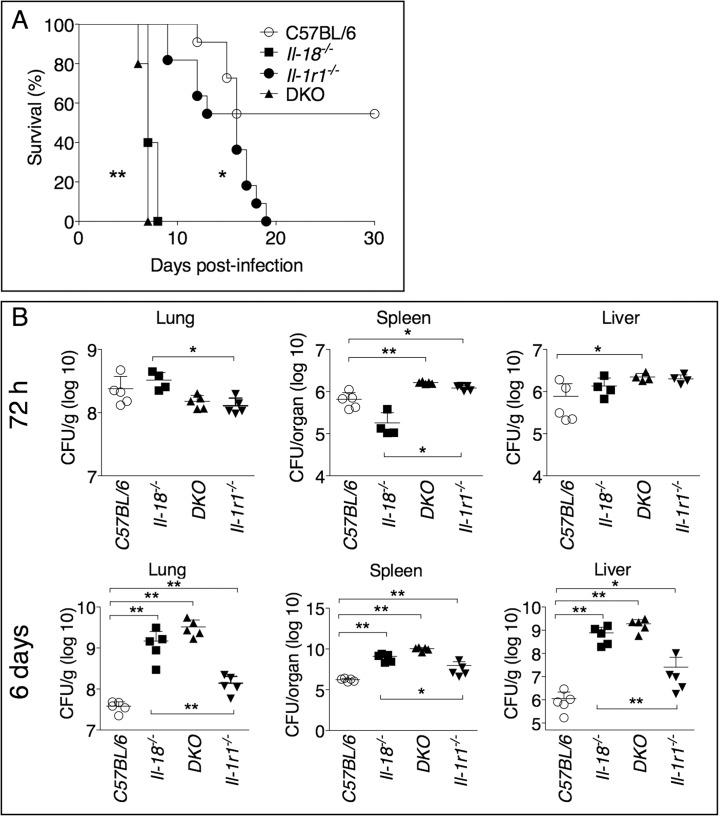

To increase our understanding of the role of IL-1 and IL-18 during lung infection with Ft LVS, we intranasally infected mice deficient in the IL-1 receptor, Il-1r1 -/-, or mice deficient in IL-18 and measured their survival. As shown in Fig. 1A, both mouse strains were significantly more susceptible than the wild type C57BL/6J mice. Mice deficient in both IL-1 receptor and IL-18 (DKO) were also more susceptible. Interestingly, the mean time to death of Il-18 -/- mice was much shorter than that of Il-1r1 -/- mice, an observation that may suggest either that IL-18 plays a more critical role than IL-1 in this model of infection, or that each cytokine may be required at a different time point during infection (see below). While the bacterial burden in organs 72 hours post infection were not consistently increased in the knock-out mouse strains compared to C57BL/6J mice, 6 days p.i. Il-18 -/- mice had significantly higher burdens than Il-1r1 -/- mice (Fig. 1B) confirming the relative contribution of each cytokine. Compared to other gram-negative bacterial infection models, infection and innate immune response occur with relatively slower kinetics during tularemia and this may explain why the differences in bacterial burdens become more evident at later time points.

Fig 1. IL-1RI and IL-18-deficient mice are more susceptible to lung infection with Ft LVS.

(A) C57BL/6J or Il-1r1 -/- mice (n = 11), or Il-18 -/- and Il-1r1 -/-/Il-18 -/- (DKO) mice (n = 5) were intranasally infected with 4x103 CFU Ft LVS and survival was monitored. (B) Mice infected as in A were euthanized 72 hours or 6 days p.i. and bacterial burden in organs was measured. One representative experiment of two is shown. Data are expressed as mean + S.D. *p<0.05, **p<0.01. (B) Mann-Whitney U test.

Role of IL-18 during lung infection with Ft LVS

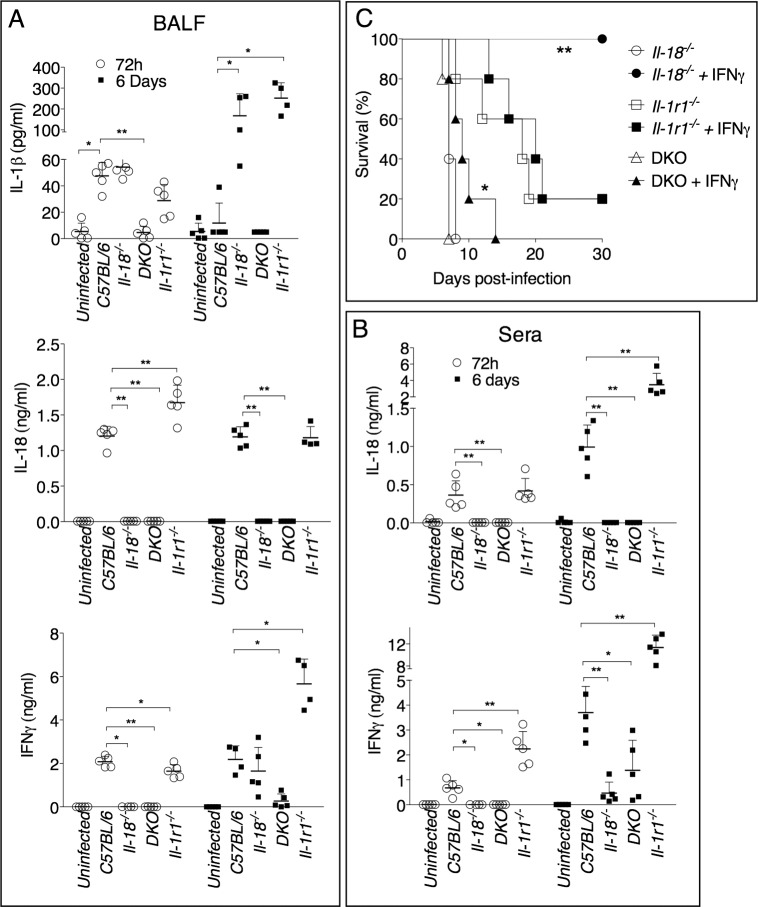

IL-1β and IL-18 levels were measured in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) or serum obtained from infected mice 72 hours or 6 days post-infection (Fig. 2A, B). IL-1β was not detectable in the sera of infected mice, but it was detected in higher amount at 72 hours than at 6 days p.i. in the BALF of C57BL/6J mice, a pattern that paralleled the reduction in bacterial burdens (see Fig. 1B). Production of IL-1β was drastically increased in Il-1r1 -/- and Il-18 -/- mice. Both IL-1 and IL-18 are known to induce Il-1b mRNA [28], which may explain why IL-1β level in BALF of DKO mice was severely reduced, compared to the other strains, despite high bacterial burden. IL-18 was detected in higher amounts in BALF, at 72 h, or in sera, at 6 days, in Il-1r1 -/- mice, compared to C57BL/6J mice. The levels IFNγ, a cytokine that is known to be protective during several bacterial infections, including tularemia [29] [30] [31] [32] [33], were reduced in Il-18 -/- mice, a finding consistent with the established function of IL-18 as an IFNγ-inducing cytokine [29], but were significantly increased in BALF or sera of Il-1r1 -/- mice, a likely reflection of the high level of IL-18 in these mice. Collectively, these results suggest that the reduced resistance of Il-18 -/- mice may be due to inability to produce sufficient IFNγ. This hypothesis was confirmed by the observation that administration of recombinant IFNβ to Il-18 -/- mice during the first 6 days of infection completely rescued their survival (Fig. 2C). In contrast, IFNγ administration did not affect the survival of Il-1r1 -/- mice, whose BALF already contained sustained level of IFNγ. These results show that distinct protective mechanisms are triggered by IL-18 and IL-1β during lung infection with Ft LVS. Interestingly, IFNγ administration to DKO mice significantly improved their survival but not to the extent of Il-1r1 -/- mice, suggesting that IL-18 may have other protective functions not strictly related to induction of IFNγ.

Fig 2. IFNγ administration rescues survival of Il-18 -/-, but not Il-1r1 -/-, mice intranasally infected with Ft LVS.

(A) Cytokine levels were measured 72 hours or 6 days p.i. in BALF (A) or serum (B) of mice intranasally infected with 4x103 CFU Ft LVS. (C) Mice (n = 5), of shown genotypes, were intranasally infected with 4x103 CFU Ft LVS and recombinant IFNγ (1 μg) was administered daily by i.p. injection for the first 6 days. Survival was monitored. One representative experiment of two is shown. Data are expressed as mean + S.D. *p<0.05, **p<0.01. Mann-Whitney U test.

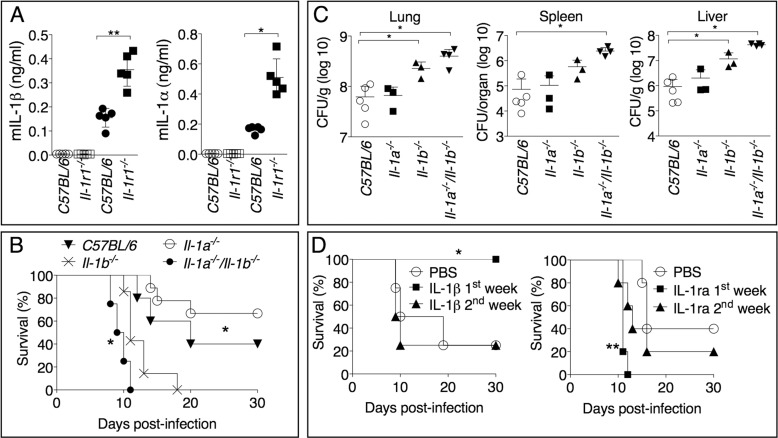

IL-1β, not IL-1α, mediates protection during Ft LVS infection and is important in the early phase of the infection

The IL-1RI mediates response to both IL-1α and IL-1β. Although both cytokines are produced during infection with Ft LVS (Fig. 3A), Il-1b -/-, but not Il-1a -/-, mice were found to be more susceptible than C57BL/6J mice to Ft LVS infection (Fig. 3B). In agreement with this result, bacteria burdens were significantly increased in organs of Il-1b -/-, but not Il-1a -/-, mice, compared to C57BL/6J mice (Fig. 3C), confirming the protective role of IL-1β. Interestingly, the combined absence of IL-1α and IL-1β appeared to result in a more drastic phenotype than the sole absence of IL-1β. Although the bacterial burden in organs was not significantly different between Il-1a -/-/Il-1b -/- and Il-1b -/- mice, absence of both cytokines significantly decreased mice survival compared to Il-1b -/- mice suggesting that, in absence of IL-1β, IL-1α may have a protective role. This effect is likely due to the fact that both cytokines are known to engage in compensatory mechanisms [34] [35] so that, in absence of IL-1β, the contribution of IL-1α, that is negligible in wild type mice, become somewhat more relevant.

Fig 3. IL-1β, not IL-1α, is protective and acts in the early phase of Ft LVS intranasal infection.

(A) IL-1α or IL-1β levels were measured 72 hours p.i. in BALF of mice intranasally infected with 4x103 CFU Ft LVS (solid symbols) or mock infected (empty symbols). (B) Mice (n = 5), of shown genotypes, were intranasally infected with 4x103 CFU Ft LVS and survival was monitored. * C57BL/6J or Il-1a -/-/Il-1b -/- compared to Il-1b -/-. (C) Organ bacterial burdens were measured 6 days p.i. in the indicated mouse strains infected as in B. (D) Il-1b -/- mice intranasally infected with 4x103 CFU Ft LVS received daily intraperitoneal injections of recombinant IL-1β (1 μg). In a similar fashion, C57BL/6J mice were treated with IL-1ra (4 mg) and infected. One representative experiment of two is shown. Data are expressed as mean + S.D. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. Mann-Whitney U test.

As shown in Fig. 2A, production of IL-1β in C57BL/6J mice is higher at 72 h than at 6 days p.i., even though the morbidity and mortality caused by its absence becomes apparent several days later. To test the hypothesis that IL-1β is protective when produced in the early phase of the infection but not in the late phase, recombinant IL-1β was administered daily during the first week or the second week post infection to Il-1r1 -/- mice. As shown in Fig. 3D, exogenous IL-1β was found to be protective only when administered during the first six days post infection. Conversely, blockage of IL-1, through administration of the IL-1 receptor antagonist IL-1ra to C57BL/6J mice, was deleterious during the first week but not during the second week post infection.

IL-1β is required for production of protective IgM

Our results so far indicate that IL-1β is produced and exerts its protective effect in the early phase of the infection, but morbidity and mortality starts to become apparent in infected Il-1r1 -/- mice only in the second week post-infection when mice definitively loose the ability to contain the infection and bacteria burden dramatically increase. This is in clear contrast to Il-18 -/- mice that shows signs of morbidity and mortality in the early days of infection (Fig. 1A). These results, together with the observation that IFNγ administration failed to rescue Il-1r1 -/- mice (Fig. 2C), suggest that the innate immune response of Il-1r1 -/- mice is sufficient to effectively control the infection and protect the mice for several days. Rather, the eventual death of Il-1r1 -/- mice may be due to failure of immune responses that are dependent on the presence of IL-1β in the early phase of infection but are effectively deployed only in the second week of infection. These features are consistent with immune responses that bridge innate and adaptive immunity, such as the generation of IgM.

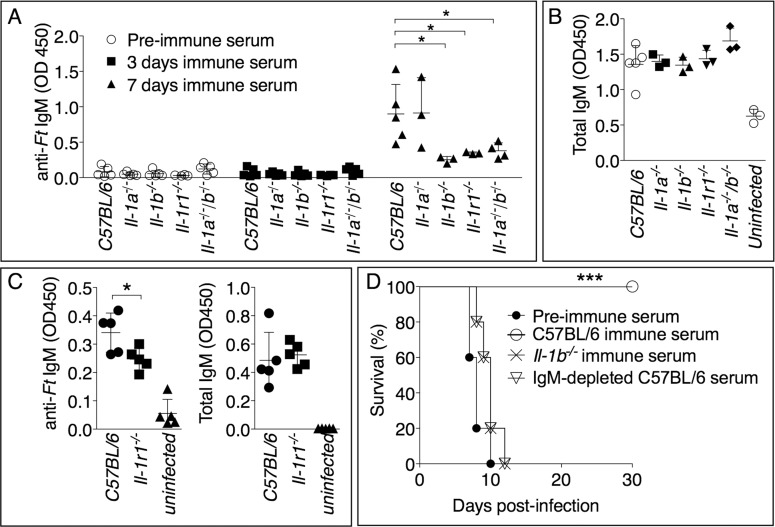

IgM is among the earliest immune effector mechanisms produced during infection and plays an important role during bacterial infections [36], including tularemia. As shown in Fig. 4A, Ft-specific IgM started to appear in the serum of infected mice 7 days post infection. Remarkably, the level of Ft-specific IgM was significantly reduced in Il-1b -/-, Il-1b -/--Il-1a -/-, or Il-1r1 -/- mice compared to C57BL/6J or Il-1a -/- mice, suggesting that the susceptibility of IL-1-deficient mice may be due to insufficient production of pathogen-specific IgM and demonstrating for the first time that IL-1β is required for optimal production of this antibody isotype. The total serum IgM levels were similar among the different mouse strains (Fig. 4B) whereas the titers of Ft-specific IgG in serum or IgA in BALF of infected mice were undistinguishable from those of non-infected mice. (S1 Fig.). Importantly, anti-Ft IgM was also present in the BALF of infected mice (Fig. 4C). Supporting the hypothesis that reduced titer of Ft-specific IgM is responsible for the susceptibility of Il-1r1 -/- mice, passive transfer of serum obtained from Ft LVS infected C57BL/6J mice seven days p.i. protected naïve C57BL/6J mice from infection with lethal doses of Ft LVS (Fig. 4D). Transfer of pre-immune serum did not confer protection, suggesting that innate antibodies were not mediating the observed protection. Remarkably, the serum obtained from Il-1b -/- mice was not protective, supporting the hypothesis that the observed protection was mainly mediated by Ft-specific IgM generated in an IL-1-dependent way. This was confirmed by the observation that serum of infected C57BL/6J mice depleted of IgM lost its protective activity. This result ruled out the possibility that other antimicrobial molecules produced during infection could play a role in the observed protection. Moreover, before passive transfer, sera were dialyzed using 100 kDa cut-off membranes to eliminate cytokines and other small inflammatory mediators.

Fig 4. Rapid generation of protective anti-Ft IgM is dependent on IL-1β.

Mice, of shown genotypes, were intranasally infected with Ft LVS 103 CFU and bled at 0, 3, or 7 days p.i. Ft-specific (A) or total IgM titers (B) were measured in serum or BALF (C). (D) C57BL/6J mice (n = 5) were injected intraperitoneally with 300 μl of preimmune serum, or the indicated immune sera. 24 hours later, mice were intranasally infected with 8x103 CFU Ft LVS and survival was monitored. One representative experiment of three (A, B) or two (C, D) is shown. Data are expressed as mean + S.D. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. Mann-Whitney U test.

Anti-Ft IgM generation is dependent on TLR2 and ASC

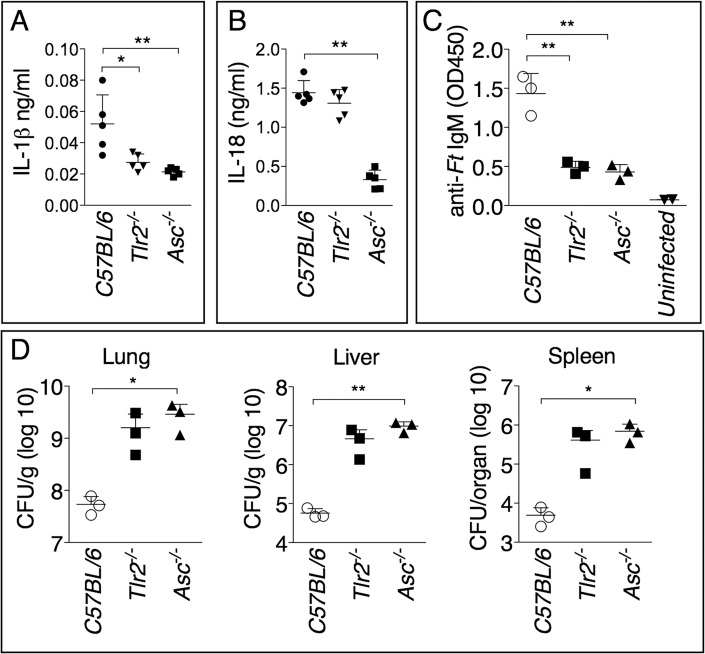

As shown in Fig. 5A, and in agreement with previous works [12,21], production of mature IL-1β in response to Ft LVS infection is dependent on TLR2 and the inflammasome adaptor ASC. Interestingly, production of IL-18 was dependent on ASC but not TLR2 (Fig. 5B). Differently from IL-1β, IL-18 is known to be constitutively expressed, which may relieve the necessity of TLR-mediated priming steps. Reinforcing the notion that IL-1β is required for the production of anti-Ft IgM, the level of this antibody was significantly decreased in the serum of infected Tlr2 -/- and Asc -/- mice (Fig. 5C). As previously shown [10] [11,21], these mice had increased bacterial burdens in the organs (Fig. 5D), another indication that anti-Ft IgM is protective.

Fig 5. Generation of protective anti-Ft LPS IgM is dependent on TLR2 and inflammasome.

Cytokine levels were measured 6 days p.i. in BALF (A) or serum (B) of mice intranasally infected with 4x103 CFU Ft LVS. (C) Anti-Ft IgM were measured on day 7 p.i. in serum of mice infected as in A. (D) Organ bacterial burdens were measured 6 days p.i. in the indicated mouse strains infected as in A. Data are expressed as mean + S.D. *p<0.05, **p<0.01. Unpaired t-test.

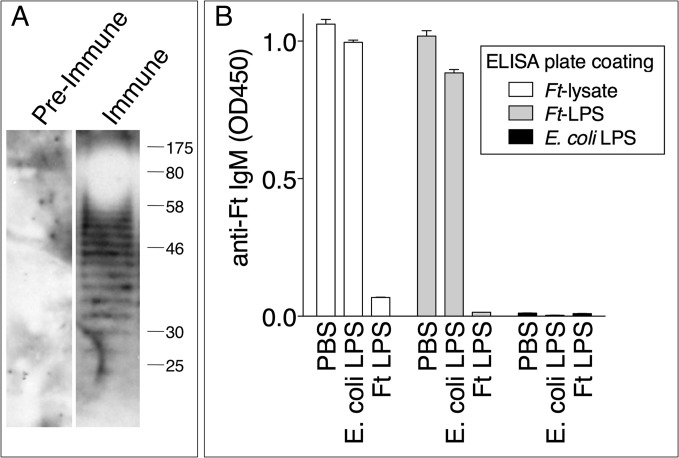

Protective IgM is specific for Ft LPS

Natural antibodies belonging to the IgM class are present in serum regardless of exposure to pathogens and tend to be poly-reactive and specific for T-independent antigens such as bacterial lipopolysaccharides [37]. As shown in Fig. 6A, pre-immune serum did not contain IgM reactive against a Ft LVS lysate. In contrast, the immune serum reacted with the Ft LVS lysate in a banding pattern characteristic of LPS. Competitive ELISA was used to show that the anti-Ft IgM was specifically directed against Ft LPS but did not react with E. coli LPS (Fig. 6B), reinforcing the notion that this is an Ft-specific response and that the measured anti-Ft LPS IgM is not part of the natural antibody repertoire.

Fig 6. Protective anti-Ft IgM are specific for Ft LPS.

(A) Preimmune serum or day 7 Ft-immune serum were used to probe Ft lysate by immunoblot. (B) Ft immune serum was incubated with PBS, E. coli LPS, or Ft LPS and then used in a competitive ELISA assay on plates coated with Ft lysate, Ft LPS, or E. coli LPS. One representative experiment of two is shown. Data are expressed as mean + S.D.

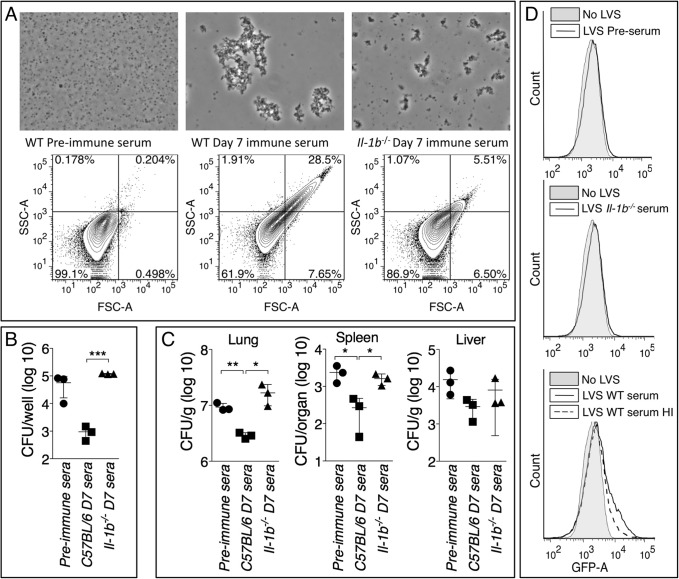

Anti-Ft IgM efficiently agglutinates Ft LVS and promotes phagocytosis

Complement fixation and agglutination are among the most effective antibacterial function of IgM. Ft LVS is known to be resistant to complement-mediated lysis [38] [39]. However, IgM-mediated C3 opsonization has been shown to enhance Ft LVS phagocytosis by PMN [40]. Day-7 immune serum from Ft LVS-infected C57BL/6 mice efficiently agglutinated Ft LVS in vitro, a phenomenon not observed with pre-immune serum and only partially with serum from infected Il-1b -/- mice (Fig. 7A). Pre-incubation of Ft LVS with immune serum significantly reduced infectivity and intracellular replication in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMM) (Fig. 7B) or in C57BL6/J mice (Fig. 7C). Pre-agglutinated bacteria were also phagocytosed more efficiently by bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDC) (Fig. 7D). When GFP-expressing Ft LVS was pre-incubated with pre-immune serum or serum from infected Il-1b -/- mice only 9.8% or 8.75% of BMDC phagocytosed bacteria and became GFP-positive, respectively. In contrast, agglutination of Ft LVS with serum from infected C57BL/6J mice dramatically increased phagocytosis of the bacteria (25.3% of cells were GFP-positive). Heat inactivation of this serum reduced the percentage of cells containing bacteria (16.5%) suggesting that the opsonic function of anti-Ft IgM is partially mediated by complement activation, a result consistent with the above-mentioned role of C3 in Ft LVS uptake. Pre-agglutination did not affect growth of bacteria in liquid cultures (S2 Fig.). Taken together, these results suggest that agglutination and C3-mediated opsonization are the main mechanisms responsible for the protective effect of anti-Ft IgM.

Fig 7. Anti-Ft IgM efficiently agglutinates Ft and promotes phagocytosis.

(A) Ft LVS agglutinated with the indicated sera was examined by microscopy or flow cytometry. (B) Agglutinated Ft LVS was used to infect BMM and intracellular bacteria replication was measured 18 hours later. (C) Agglutinated Ft LVS (6.5x103 CFU) was used to infect intranasally C57BL/6J mice and bacteria burdens were measured 48 hours later. (D) GFP-expressing Ft LVS was agglutinated with the indicated sera and used to infect BMDC. Bacteria uptake was measured by flow cytometry. HI, heat inactivated. Data are expressed as mean + S.D. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. Unpaired t-test.

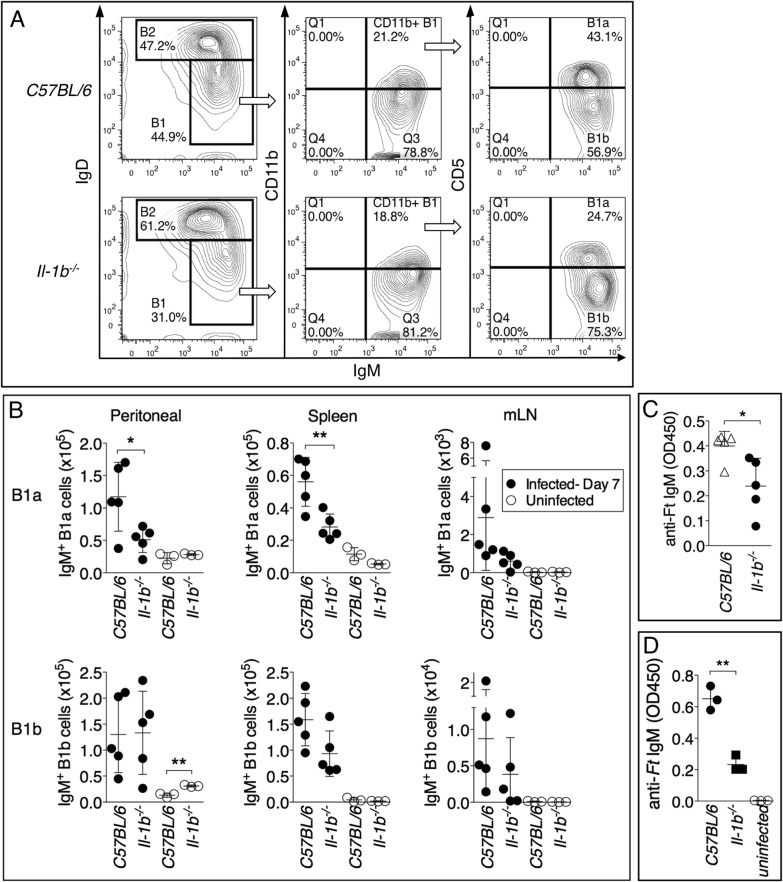

Role of B1a B cells in production of anti-Ft LPS IgM

Both B1 and B2 B cells subsets are known to contribute to rapid production of IgM during infection and to a different extent depending on the pathogen. B1 B cells and marginal zone B cells (MZ B cells) are a major source of natural antibodies and IgM specific for T-independent antigens such as LPS and self-antigens [41] [42]. Previous work has shown that immunization with purified Ft LPS caused expansion of B1a B cells [43]. Analysis of various B cells subsets in mice infected for 7 days with Ft LVS revealed that C57BL/6J and Il-1r1 -/- mice or Il-1b -/- mice (S3 Fig.) had a similar percentage and total number of B cells, MZ B cells, and follicular B cells in different anatomical locations. In contrast, B1a B cells, but not B1b B cells, were detected in lower proportions in the peritoneal cavity and spleen of Il-1b -/- mice, compared to C57BL/6J mice (Fig. 8B). B1a B cells were present in equal amount in uninfected C57BL/6J or Il-1b -/- mice suggesting that absence of IL-1β affects the infection-induced expansion of these cells, not their homeostasis. Spleen cells from infected C57BL/6J and Il-1b -/- mice were cultured for 18 hours in presence of PMA and anti-Ft IgM was measured in the cultured supernatants. As shown in Fig. 8C, cells derived from Il-1b -/- mice released significantly lower amount of anti-Ft IgM compared to C57BL/6J cells. Given that B1a cells were the only B cell subset differentially represented in the spleen of C57BL/6J and Il-1b -/- mice (Fig. 8B and S3 Fig.), these data suggests that the anti-Ft LPS IgM is produced by B1a B cells. To demonstrate this point conclusively, B1a B cells were purified by flow cytometry from the spleen of C57BL/6J or Il-1b -/- infected mice and cultivated for 24 hours. Anti-Ft LPS IgM were present in the conditioned supernatants of purified B1a B cell cultures (Fig. 8D) and, more importantly, in higher amount in C57BL/6J than in Il-1b -/- cells. Together with the in vivo results, these data demonstrate that B1a B cells are the source of the Ft-specific IgM and that expansion of these cells depends on IL-1β.

Fig 8. Reduced number of B1a B cells in Il-1b -/- mice infected with Ft LVS.

(A) Representative FACS profile and gating strategy to identify B1a and B1b B cells. (B) The number of B1a and B1b B cells was measured in peritoneal lavage, spleen, and mediastinal lymph nodes of indicated mouse strains intranasally infected with Ft LVS 103 CFU 6 days p.i. (C) Total spleen cells (5x106 cells/ml) or (D) purified B1a B cells (x106 cells/ml) from mice infected as in A were cultured for 24 hours. IgM was measured in culture supernatants. One representative experiment of three is shown. Data are expressed as mean + S.D. *p<0.05, **p<0.01. Unpaired t-test.

Discussion

A number of studies over the past few years have characterized the innate immune response against Ft LVS infection and in particular the protective role played by activation of the AIM2 inflammasome [3,44]. However, by comparison, the role of IL-1β and IL-18 in this infection has been somewhat neglected and remains unclear.

Our study is the first to show that during lung infection with Ft LVS, IL-1β and IL-18 are protective, but through different mechanisms. IL-18-deficient mice quickly succumbed to infection with high organ bacterial burdens and low levels of IFNγ, a cytokine that has been shown to be critical for protection from tularemia [30] [31] [32] [33]. Administration of IFNγ increased the survival of Il-18 -/- mice, suggesting that the lower resistance to tularemia is due to an inability to produce IFNγ. In contrast, IFNγ administration had no effect on Il-1r1 -/- mice survival. Thus, different mechanisms determine the increased susceptibility of Il-1r1 -/- and Il-18 -/- mice to tularemia. This conclusion was also supported by the observation that Il-1r1 -/- or Il-1b -/- mice appear to be able to control the infection, at least in its early stages, but eventually succumbed. This raised the possibility that responses at the boundary of innate and adaptive immunity were defective in absence of IL-1β. In fact, our results show that Il-1r1 -/- mice produced Ft LPS-specific IgM in a significantly reduced amount compared to C57BL/6J mice. Passive immunization experiments showed that anti-Ft IgM were protective, suggesting that the higher susceptibility of IL-1-deficient mice is partly due to reduced production of anti-Ft-LPS IgM.

The antibody response to Ft infection has been characterized in detail in mice and humans and is mainly directed against LPS and composed of IgM and IgG [45]. Several studies have previously shown that Ft LVS infection, or immunization with Ft LPS, result in a protective humoral response that can be passively transferred [46] [47] [48] [49]. In all these studies, the passive immunization relied on immune sera obtained several weeks post infection/immunization, implying a role for Ft-specific IgG, rather than IgM. One study in fact showed that in order to be protective, serum should be collected at least 15 days p.i. [46]. In that study mice were infected intradermaly as opposed to the intranasal route we used. One novelty of our study is that it shows that during intranasal infection with Ft LVS the protective humoral response is deployed more rapidly than previously thought and that IgM is a critical component of this response. The fact that Ft LVS has been shown to have a significant extracellular phase in infected mice [50] explains why the humoral response can be so effective against infection with this facultative intracellular bacterium. Importantly, our results show that anti-Ft IgM is present in the BALF of infected mice suggesting a role for this Ig isotype at mucosal surfaces. It is likely that infection-induced tissue damage and vascular leakage are responsible for IgM spillage into alveolar spaces.

It is increasingly recognized that IgM plays a protective role during infections, yet the mechanisms of protection have not been consistently defined. IgM efficiently fixes complement and promotes bacteria agglutination and phagocytosis. Although, Ft is resistant to complement-mediated lysis [39] [51], it has been demonstrated that IgM-mediated C3 deposition enhances Ft LVS phagocytosis by neutrophils [40]. Our results support the conclusion that the protection conferred by passive transfer of anti-Ft IgM is mediated by enhanced agglutination/opsonization.

Although it is widely accepted that IgM represents an important first line of defense against infection [36], the pathways leading to production of these antibodies during infection and many aspects of their biology remain unclear. Different B cell subsets, including marginal zone (MZ) B cells and B1 B cells, have been shown to be the main source of the IgM rapidly generated against T-independent antigens during viral or bacterial infections [52]. Studies have indicated that among B1 B cells, the B1a subset is primarily responsible for production of natural IgM while B1b B cells produce pathogen-specific immune IgM [53,54]. However, recent studies have challenged this simplistic classification by showing pathogen-specific antibody production by B1a B cells [43].

Here we show that the reduced serum titer of Ft LPS-specific IgM in IL-1-deficient mice correlated with a significant reduction in the percentage of B1a B cells in the spleen and peritoneal cavity in these mice. Purification of B1a B cells from infected mice confirmed that these cells are responsible for production of the protective anti-Ft LPS IgM. This conclusion is in agreement with the work of Cole et al. [43] that elegantly showed that vaccination of mice with purified Ft LPS rapidly elicits expansion of a rare population of B1a B cells as well as production of anti-Ft LPS protective antibodies. In a follow-up study [55], the same authors showed that the protection conferred by Ft LPS immunization required antibody production and macrophages activation. It should be noted that neither study showed whether the protective anti-Ft LPS antibodies were IgM and whether transfer of sera containing them was sufficient for protection, as demonstrated in our experiments. Our study complements that of Cole et al. [43] by showing that expansion of B1a B cells and the production of anti-Ft LPS antibodies occurs during a natural infection with Ft LVS, as opposed to the artificial setting of vaccination. In their study [43], Cole et al. concluded that generation of the anti-Ft LPS antibodies was independent of innate immunity because this response was observed in TLR4- or TLR2-deficient mice. Interestingly, despite similar titers of anti-Ft LPS antibodies in C57BL/6J and Tlr2 -/- mice, immunization with Ft LPS was not protective in Tlr2 -/- mice. Of note, Ft LPS does not activate TLR4 or TLR2 [5] [6] [7]. On the other hand, Ft LVS has been shown to activate TLR2 [10] [12] and, consistent with this, our results show that production of anti-Ft LPS IgM, as well as IL-1β, depends on TLR2 and the inflammasome adaptor ASC. Thus, it appears that generation of anti-Ft LPS antibodies can proceed in absence of TLR stimulation in the Ft LPS vaccination setting. However, during infection with Ft LVS, activation of TLR2 and the inflammasome significantly boosts this response in an IL-1β-dependent fashion. The disparities between vaccination and natural infection are likely due to the fact that vaccination with purified LPS delivers a signal sufficiently strong to activate B1a B cells even in absence of TLR engagement and cytokine production. In contrast, in the natural infection setting “free LPS” may be present in much lower amount and, under these circumstances, the adjuvant effect of IL-1β becomes essential for efficient expansion of B1a B cells. Interestingly, it has been reported that mice deficient in Bruton’s tyrosine kinase, which lack B1a B cells, were more susceptible to lung infection with the Ft virulent strain SchuS4 due to an increase in macrophages and NK/NKT cells [56].

The role of IL-1 for antibody production has been extensively analyzed in conventional B cells, and seems to vary according to the experimental setting [57]. In contrast, whether IL-1 regulates the development of B1 B cells and production of IgM by this cell type has not been investigated. Decreased IgM production in Il-1r1 -/- mice has been reported, although the involvement of B1 B cells subsets was not examined in that study [58]. Our study reveals that rapid production of anti-Ft LPS IgM by B1a B cells depends on IL-1β and suggests, for the first time, a role for IL-1β in the development of B1a B cells during a bacterial infection. Several questions are prompted by our study: Is IL-1β action on B1a B cells direct or mediated by other factors/cells that may regulate migration and activation of these cells? Is the requirement for IL-1β absolute or limited to an enhancing role for a timely production of IgM by B1a B cells? Although the B1a cell population was the only one quantitatively altered in absence of IL-1β, is production of IgM by B1b or MZ B cells regulated by IL-1β in other settings? The IL-1 family member IL-33 has been shown to be required for B1 B cells development [59]. Interestingly, IL-1RAcP, the signaling subunit shared by IL-1 receptor and ST2, the IL-33 receptor, was differentially expressed by B1a and B1b subsets. Whether IL-1RI is differentially expressed in B cell subsets remains to be determined. Future studies should examine the role of IL-1β in B1 B cells activation and IgM production during different bacterial and viral infections

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All the animal experiments described in the present study were conducted in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. All animal studies were conducted under protocols approved by the Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) (protocol # B12-07). All efforts were made to minimize suffering and ensure the highest ethical and humane standards.

Mice

C57BL/6, Tlr2 -/-, Il-1r1 -/-, Il-18 -/- were purchased from Jackson lab and bred in our facility. Il-18 -/--Il-1r1 -/- double deficient mice (DKO) were obtained by crossing the parental single knockout mice. Asc -/- mice were obtained from V. Dixit (Genentech). Il-1a -/- and Il-1a -/-/Il-1b -/- were from I. Iwakura, Il-1b -/- from D. Chaplin. All mouse strains were on C57BL/6 genetic background and were bred under specific pathogen-free conditions in our facility. Age-(8–12 weeks old) and sex-matched animals were used in all experiments. Generally, experimental groups were composed of at least 5 mice. All the animal experiments described in the present study were conducted in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. All animal studies were conducted under protocols approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science.

Bacteria, mice infection and treatments

For all experiments the Francisella tularensis LVS was used. GFP-expressing Ft LVS was provided by Mark Miller (UTHSC). Bacteria were grown in MH broth (Muller Hinton supplemented with 0.1% glucose, 0.1% cysteine, 0.25% ferric pyrophosphate, and 2.5% calf serum) to mid-logarithmic phase, their titer was determined by plating serial dilutions on complete MH agar, and stocks were maintained frozen at −80°C. No loss in viability was observed over prolonged storage. For infections, frozen stocks were diluted in sterile PBS to the desired titer. Aliquots were plated on complete MH agar to confirm actual cfu. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane using a Surgivet apparatus and 50 ml of bacteria suspension were applied to the nare. In some experiments, mice were injected i.p. daily with recombinant mouse IL-1β (1 μg) or IFNγ (1 μg). IL-1ra (Biovitrum) was administered by alternating s.c. and i.p. injections every 12 hours (60 mg/kg body weight).

Determination of bacteria growth in tissue culture and organs

Organs aseptically collected were weighted and homogenized in 1 ml PBS containing 0.5% saponin and 3% BSA. Serial dilutions were plated on complete MH agar plates.

BALF collection and cytokine measurements

BALF were collected from euthanized mice by intratracheal injection and aspiration of 1 ml PBS. Cytokine levels in BALF or serum were measured by ELISA using the following paired antibodies kits: mIL-1α, mIL-1β, mIFNγ (eBioscience), mIL-18 (MBL Nagoya, Japan).

Determination of antibody titers and competitive ELISA

Blood was collected aseptically from the submandibular vein. Ft LPS-specific immunoglobulin levels in sera or BALF were measured by ELISA. Serial dilutions of sera were plated in 96 wells plates coated with Ft LVS lysate (10 μg/ml). HRP-conjugated rat anti-mouse IgM or IgG (Southern Biotech Associates, Birmingham, AL) was added followed by TMB substrate and measurement of absorbance at 450 nm. For competitive ELISA (Fig. 6B) plates were coated with Ft LVS lysate (10 μg/ml), purified Ft LVS LPS (10 μg/ml), or E. coli LPS (0111:B4, 10 μg/ml). Immune serum was preincubated with PBS, E. coli LPS or Ft LVS LPS (1 μg) for 30 minutes before dilution and addition to coated plates.

Western blot

Ft LVS lysate (50 μg) was separated by 12% PAGE electrophoresis, transferred to PVDF membranes, and probed with pre-immune or immune serum (1:300 dilution) followed by anti-mouse IgM-HRP (Upstate Biotechnologies) and developed by ECL Femto (Pierce).

Passive immunization

Preimmune serum or sera from different mouse strains infected for 7 days were dialyzed against PBS (100 kDa mw cut-off) and 300 μl were intraperitoneally administered to mice 18 hours before infection. To deplete IgM, serum was incubated 1 hours at 4°C with anti-mouse IgM agarose (Sigma).

Bacteria agglutination, infectivity, and phagocytosis

Ft LVS was grown O/N in complete MH broth. 10 μl of bacterial culture were incubated with 10 μl of serum for 10 minutes at RT. Agglutination was confirmed by microscopy and flow cytometry. To measure infectivity of agglutinated Ft LVS in vitro, BMM were infected with bacteria preincubated with different sera at a MOI 500 and infection allowed to proceed for 2 hours. Cells were then washed 3 times with PBS and cultured for additional 18 hours in DMEM-10% FCS containing gentamicin and kanamycin (400 μg/ml). Media were aspirated and cells lysed in PBS containing 0.5% saponin and 3% BSA. Serial dilutions were plated on complete MH agar. To measure phagocytosis, BMDC were incubated for 4 hours with GFP-expressing Ft LVS agglutinated with different sera. Some sera were heat inactivated at 56 C for 30 minutes. Gentamicin and kanamycin (400 μg/ml) were then added to the medium for 4 more hours to kill extracellular bacteria and cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. The percentage of GFP positive cells (those that phagocytosed Ft LVS) was calculated by Overton subtraction.

Flow cytometry

Cells obtained from BALF, peritoneal lavage, spleen, or mediastinal lymph nodes were resuspended in FACS buffer (1% BSA, 0.05% NaN3 in PBS) containing anti-CD16/CD32 (clone 2.4G2) and counted. For analysis cells were incubated for 30’ on ice with the following antibody cocktails: for myeloid cells, CD11b-PECy7, Ly6G-PE, F4/80-APC, CD11c-FITC and NKp46-BV421; for GC B cells, B220-PercpCy5.5, CD4-APC, FAS-PE and GL-7-FITC; for marginal zone (MZ) and Follicular B cells, CD19-BV421, CD23-PECy7 and CD21-APC; for B1 cells, CD19-BV421, IgM-PECy7, IgD-APC, CD11b-AF700 and CD5-PE; for TFH cells, CXCR5-biotin followed by streptavidin-APC, CD4-PercpCy5.5, BTLA-PE and PD1-FITC.

GC B cells are defined as CD4- B220+ cells expressing both FAS and GL-7; TFH cells are CD4+ CXCR5+ BTLA+ [60]; Fol B cells are defined as CD19+ CD23+ CD21-/intermediate; MZ B cells are the CD19+ CD21+ CD23-/low cells [61]. B cells (CD19+) were gated on lymphocyte gate followed by singlet gate (FSC-A vs FSC/H) and identified as B2 or B1 cells according to the surface expression of IgD or IgM, respectively. B1 B cells subsets are defined as described in [54] [61] as CD19+ IgMhigh IgD-/low. B1 B cells were selected and gated for the expression of CD11b and CD5. B1a cells are defined as CD5+, B1b cells as CD5-. FMO or isotype controls were used to set the gate. Data were acquired with a BD LSR II flow-cytometer (BD biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo 7.6.5 software (Treestar Inc).

B1a B cell sorting and purification

B1a B cells were purified from the spleen of mice infected for 7 days with Ft LVS according to [56]. Single cell suspensions of splenic cells were enriched by negative selection for B cells using the B cell isolation kit (StemCell). The CD19+/CD5+ B1 a B cells were sorted with a BD FACSAria II u flow cytometer. B1a B cells were resuspended in DMEM-10% FCS at a density of 1.5 x106 and cultured in 96 well plate for 24 hours.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean + S.D. Survival curves were compared using the log rank Kaplan-Meier test. Mann-Whitney U test or unpaired t-test were used for analysis of the rest of data as specified in figure legends. Significance was set at p<0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism 5.0.

Supporting Information

Ft-specific IgG in serum or IgA in BALF of mice intranasally infected with Ft LVS 103 CFU were measured on day 7 p.i.

(JPG)

Ft LVS agglutinated with the indicated sera were grown in complete MH broth and absorbance was measured at indicated time points.

(JPG)

Leukocyte populations were measured in BALF, spleen, and mediastinal lymph nodes of Il-1r1 -/- (A-C) or Il-1b -/- (D, E) mice intranasally infected with Ft LVS 103 CFU 6 days p.i. One representative experiment of three is shown. Data are expressed as mean + S.D. *p<0.05, **p<0.01. Unpaired t-test.

(JPG)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to V. Dixit, Genentech, for Asc -/- mice, to I. Iwakura for Il-1a -/- and Il-1a -/-/Il-1b -/- mice, to D. Chaplin for Il-1b -/- mice, to Alice Gilman-Sachs for reading the manuscript, and to Robert Dickinson for help with flow cytometry.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI081861 (FR). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. McLendon MK, Apicella MA, Allen LA (2006) Francisella tularensis: taxonomy, genetics, and Immunopathogenesis of a potential agent of biowarfare. Annu Rev Microbiol 60: 167–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Steiner DJ, Furuya Y, Metzger DW (2014) Host-pathogen interactions and immune evasion strategies in Francisella tularensis pathogenicity. Infect Drug Resist 7: 239–251. 10.2147/IDR.S53700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Elkins KL, Cowley SC, Bosio CM (2007) Innate and adaptive immunity to Francisella. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1105: 284–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jones CL, Napier BA, Sampson TR, Llewellyn AC, Schroeder MR, et al. (2012) Subversion of host recognition and defense systems by Francisella spp. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 76: 383–404. 10.1128/MMBR.05027-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cole LE, Elkins KL, Michalek SM, Qureshi N, Eaton LJ, et al. (2006) Immunologic consequences of Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain infection: role of the innate immune response in infection and immunity. J Immunol 176: 6888–6899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hajjar AM, Harvey MD, Shaffer SA, Goodlett DR, Sjostedt A, et al. (2006) Lack of in vitro and in vivo recognition of Francisella tularensis subspecies lipopolysaccharide by Toll-like receptors. Infect Immun 74: 6730–6738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barker JH, Weiss J, Apicella MA, Nauseef WM (2006) Basis for the failure of Francisella tularensis lipopolysaccharide to prime human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Infect Immun 74: 3277–3284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ancuta P, Pedron T, Girard R, Sandstrom G, Chaby R (1996) Inability of the Francisella tularensis lipopolysaccharide to mimic or to antagonize the induction of cell activation by endotoxins. Infect Immun 64: 2041–2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dreisbach VC, Cowley S, Elkins KL (2000) Purified lipopolysaccharide from Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain (LVS) induces protective immunity against LVS infection that requires B cells and gamma interferon. Infect Immun 68: 1988–1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Katz J, Zhang P, Martin M, Vogel SN, Michalek SM (2006) Toll-like receptor 2 is required for inflammatory responses to Francisella tularensis LVS. Infect Immun 74: 2809–2816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Malik M, Bakshi CS, Sahay B, Shah A, Lotz SA, et al. (2006) Toll-like receptor 2 is required for control of pulmonary infection with Francisella tularensis. Infect Immun 74: 3657–3662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li H, Nookala S, Bina XR, Bina JE, Re F (2006) Innate immune response to Francisella tularensis is mediated by TLR2 and caspase-1 activation. J Leukoc Biol 80: 766–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thakran S, Li H, Lavine CL, Miller MA, Bina JE, et al. (2008) Identification of Francisella tularensis lipoproteins that stimulate the toll-like receptor (TLR) 2/TLR1 heterodimer. J Biol Chem 283: 3751–3760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Henry T, Monack DM (2007) Activation of the inflammasome upon Francisella tularensis infection: interplay of innate immune pathways and virulence factors. Cell Microbiol 9: 2543–2551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cunha LD, Zamboni DS (2013) Subversion of inflammasome activation and pyroptosis by pathogenic bacteria. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 3: 76 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Atianand MK, Duffy EB, Shah A, Kar S, Malik M, et al. (2011) Francisella tularensis reveals a disparity between human and mouse NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J Biol Chem 286: 39033–39042. 10.1074/jbc.M111.244079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dinarello CA (2009) Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin-1 family. Annu Rev Immunol 27: 519–550. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kingry LC, Petersen JM (2014) Comparative review of Francisella tularensis and Francisella novicida. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 4: 35 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fortier AH, Slayter MV, Ziemba R, Meltzer MS, Nacy CA (1991) Live vaccine strain of Francisella tularensis: infection and immunity in mice. Infect Immun 59: 2922–2928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Elkins KL, Winegar RK, Nacy CA, Fortier AH (1992) Introduction of Francisella tularensis at skin sites induces resistance to infection and generation of protective immunity. Microb Pathog 13: 417–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mariathasan S, Weiss DS, Dixit VM, Monack DM (2005) Innate immunity against Francisella tularensis is dependent on the ASC/caspase-1 axis. J Exp Med 202: 1043–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Collazo CM, Sher A, Meierovics AI, Elkins KL (2006) Myeloid differentiation factor-88 (MyD88) is essential for control of primary in vivo Francisella tularensis LVS infection, but not for control of intra-macrophage bacterial replication. Microbes Infect 8: 779–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Huang MT, Mortensen BL, Taxman DJ, Craven RR, Taft-Benz S, et al. (2010) Deletion of ripA alleviates suppression of the inflammasome and MAPK by Francisella tularensis. J Immunol 185: 5476–5485. 10.4049/jimmunol.1002154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ulland TK, Buchan BW, Ketterer MR, Fernandes-Alnemri T, Meyerholz DK, et al. (2010) Cutting edge: mutation of Francisella tularensis mviN leads to increased macrophage absent in melanoma 2 inflammasome activation and a loss of virulence. J Immunol 185: 2670–2674. 10.4049/jimmunol.1001610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jayakar HR, Parvathareddy J, Fitzpatrick EA, Bina XR, Bina JE, et al. (2011) A galU mutant of Francisella tularensis is attenuated for virulence in a murine pulmonary model of tularemia. BMC Microbiol 11: 179 10.1186/1471-2180-11-179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Peng K, Broz P, Jones J, Joubert LM, Monack D (2011) Elevated AIM2-mediated pyroptosis triggered by hypercytotoxic Francisella mutant strains is attributed to increased intracellular bacteriolysis. Cell Microbiol 13: 1586–1600. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01643.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ulland TK, Janowski AM, Buchan BW, Faron M, Cassel SL, et al. (2013) Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain folate metabolism and pseudouridine synthase gene mutants modulate macrophage caspase-1 activation. Infect Immun 81: 201–208. 10.1128/IAI.00991-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Puren AJ, Fantuzzi G, Gu Y, Su MS, Dinarello CA (1998) Interleukin-18 (IFNgamma-inducing factor) induces IL-8 and IL-1beta via TNFalpha production from non-CD14+ human blood mononuclear cells. J Clin Invest 101: 711–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Okamura H, Tsutsi H, Komatsu T, Yutsudo M, Hakura A, et al. (1995) Cloning of a new cytokine that induces IFN-gamma production by T cells. Nature 378: 88–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Anthony LS, Ghadirian E, Nestel FP, Kongshavn PA (1989) The requirement for gamma interferon in resistance of mice to experimental tularemia. Microb Pathog 7: 421–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Anthony LS, Morrissey PJ, Nano FE (1992) Growth inhibition of Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain by IFN-gamma-activated macrophages is mediated by reactive nitrogen intermediates derived from L-arginine metabolism. J Immunol 148: 1829–1834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chen W, KuoLee R, Shen H, Conlan JW (2004) Susceptibility of immunodeficient mice to aerosol and systemic infection with virulent strains of Francisella tularensis. Microb Pathog 36: 311–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Duckett NS, Olmos S, Durrant DM, Metzger DW (2005) Intranasal interleukin-12 treatment for protection against respiratory infection with the Francisella tularensis live vaccine strain. Infect Immun 73: 2306–2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Horai R, Asano M, Sudo K, Kanuka H, Suzuki M, et al. (1998) Production of mice deficient in genes for interleukin (IL)-1alpha, IL-1beta, IL-1alpha/beta, and IL-1 receptor antagonist shows that IL-1beta is crucial in turpentine-induced fever development and glucocorticoid secretion. J Exp Med 187: 1463–1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Oguri S, Motegi K, Iwakura Y, Endo Y (2002) Primary role of interleukin-1 alpha and interleukin-1 beta in lipopolysaccharide-induced hypoglycemia in mice. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 9: 1307–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Racine R, Winslow GM (2009) IgM in microbial infections: taken for granted? Immunol Lett 125: 79–85. 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ehrenstein MR, Notley CA (2010) The importance of natural IgM: scavenger, protector and regulator. Nat Rev Immunol 10: 778–786. 10.1038/nri2849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sorokin VM, Pavlovich NV, Prozorova LA (1996) Francisella tularensis resistance to bactericidal action of normal human serum. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 13: 249–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ben Nasr A, Klimpel GR (2008) Subversion of complement activation at the bacterial surface promotes serum resistance and opsonophagocytosis of Francisella tularensis. J Leukoc Biol 84: 77–85. 10.1189/jlb.0807526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schwartz JT, Barker JH, Long ME, Kaufman J, McCracken J, et al. (2012) Natural IgM mediates complement-dependent uptake of Francisella tularensis by human neutrophils via complement receptors 1 and 3 in nonimmune serum. J Immunol 189: 3064–3077. 10.4049/jimmunol.1200816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Baumgarth N (2011) The double life of a B-1 cell: self-reactivity selects for protective effector functions. Nat Rev Immunol 11: 34–46. 10.1038/nri2901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cerutti A, Cols M, Puga I (2013) Marginal zone B cells: virtues of innate-like antibody-producing lymphocytes. Nat Rev Immunol 13: 118–132. 10.1038/nri3383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cole LE, Yang Y, Elkins KL, Fernandez ET, Qureshi N, et al. (2009) Antigen-specific B-1a antibodies induced by Francisella tularensis LPS provide long-term protection against F. tularensis LVS challenge. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 4343–4348. 10.1073/pnas.0813411106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Broz P, Monack DM (2011) Molecular mechanisms of inflammasome activation during microbial infections. Immunol Rev 243: 174–190. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01041.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cowley SC, Elkins KL (2011) Immunity to Francisella. Front Microbiol 2: 26 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rhinehart-Jones TR, Fortier AH, Elkins KL (1994) Transfer of immunity against lethal murine Francisella infection by specific antibody depends on host gamma interferon and T cells. Infect Immun 62: 3129–3137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fulop M, Mastroeni P, Green M, Titball RW (2001) Role of antibody to lipopolysaccharide in protection against low- and high-virulence strains of Francisella tularensis. Vaccine 19: 4465–4472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kirimanjeswara GS, Golden JM, Bakshi CS, Metzger DW (2007) Prophylactic and therapeutic use of antibodies for protection against respiratory infection with Francisella tularensis. J Immunol 179: 532–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lavine CL, Clinton SR, Angelova-Fischer I, Marion TN, Bina XR, et al. (2007) Immunization with heat-killed Francisella tularensis LVS elicits protective antibody-mediated immunity. Eur J Immunol 37: 3007–3020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Forestal CA, Malik M, Catlett SV, Savitt AG, Benach JL, et al. (2007) Francisella tularensis has a significant extracellular phase in infected mice. J Infect Dis 196: 134–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Clay CD, Soni S, Gunn JS, Schlesinger LS (2008) Evasion of complement-mediated lysis and complement C3 deposition are regulated by Francisella tularensis lipopolysaccharide O antigen. J Immunol 181: 5568–5578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Martin F, Oliver AM, Kearney JF (2001) Marginal zone and B1 B cells unite in the early response against T-independent blood-borne particulate antigens. Immunity 14: 617–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Alugupalli KR, Gerstein RM, Chen J, Szomolanyi-Tsuda E, Woodland RT, et al. (2003) The resolution of relapsing fever borreliosis requires IgM and is concurrent with expansion of B1b lymphocytes. J Immunol 170: 3819–3827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Haas KM, Poe JC, Steeber DA, Tedder TF (2005) B-1a and B-1b cells exhibit distinct developmental requirements and have unique functional roles in innate and adaptive immunity to S. pneumoniae. Immunity 23: 7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cole LE, Mann BJ, Shirey KA, Richard K, Yang Y, et al. (2011) Role of TLR signaling in Francisella tularensis-LPS-induced, antibody-mediated protection against Francisella tularensis challenge. J Leukoc Biol 90: 787–797. 10.1189/jlb.0111014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Crane DD, Griffin AJ, Wehrly TD, Bosio CM (2013) B1a cells enhance susceptibility to infection with virulent Francisella tularensis via modulation of NK/NKT cell responses. J Immunol 190: 2756–2766. 10.4049/jimmunol.1202697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nakae S, Asano M, Horai R, Iwakura Y (2001) Interleukin-1 beta, but not interleukin-1 alpha, is required for T-cell-dependent antibody production. Immunology 104: 402–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Schmitz N, Kurrer M, Bachmann MF, Kopf M (2005) Interleukin-1 is responsible for acute lung immunopathology but increases survival of respiratory influenza virus infection. J Virol 79: 6441–6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Komai-Koma M, Gilchrist DS, McKenzie AN, Goodyear CS, Xu D, et al. (2011) IL-33 activates B1 cells and exacerbates contact sensitivity. J Immunol 186: 2584–2591. 10.4049/jimmunol.1002103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Nurieva RI, Chung Y, Martinez GJ, Yang XO, Tanaka S, et al. (2009) Bcl6 mediates the development of T follicular helper cells. Science 325: 1001–1005. 10.1126/science.1176676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Malkiel S, Kuhlow CJ, Mena P, Benach JL (2009) The loss and gain of marginal zone and peritoneal B cells is different in response to relapsing fever and Lyme disease Borrelia. J Immunol 182: 498–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Ft-specific IgG in serum or IgA in BALF of mice intranasally infected with Ft LVS 103 CFU were measured on day 7 p.i.

(JPG)

Ft LVS agglutinated with the indicated sera were grown in complete MH broth and absorbance was measured at indicated time points.

(JPG)

Leukocyte populations were measured in BALF, spleen, and mediastinal lymph nodes of Il-1r1 -/- (A-C) or Il-1b -/- (D, E) mice intranasally infected with Ft LVS 103 CFU 6 days p.i. One representative experiment of three is shown. Data are expressed as mean + S.D. *p<0.05, **p<0.01. Unpaired t-test.

(JPG)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.