Abstract

The Midhurst Macmillan Specialist Palliative Care Service (MMSPCS) is a UK, medical consultant-led, multidisciplinary team aiming to provide round-the-clock advice and care, including specialist interventions, in the home, community hospitals and care homes. Of 389 referrals in 2010/11, about 85% were for cancer, from a population of about 155 000. Using a mixed method approach, the evaluation comprised: a retrospective analysis of secondary-care use in the last year of life; financial evaluation of the MMSPCS using an Activity Based Costing approach; qualitative interviews with patients, carers, health and social care staff and MMSPCS staff and volunteers; a postal survey of General Practices; and a postal survey of bereaved caregivers using the MMSPCS. The mean cost is about 3000 GBP (3461 EUR) per patient with mean cost of interventions for cancer patients in the last year of life 1900 GBP (2192 EUR). Post-referral, overall costs to the system are similar for MMSPCS and hospice-led models; however, earlier referral avoided around 20% of total costs in the last year of life. Patients and carers reported positive experiences of support, linked to the flexible way the service worked. Seventy-one per cent of patients died at home. This model may have application elsewhere.

Keywords: specialist palliative care, end-of-life care, home care services, home death, preferred place of care/death, mixed methods evaluation.

Background

The Palliative Care Funding Review highlighted the need for access to good and consistent palliative care services in the UK. It drew attention to increasing complex needs of the older population and the variation in care provision (Department of Health 2011a). The benefits of specialist palliative care to patients and carers is reported in reviews of outcomes across a number of countries, and in a number of settings, with the strongest findings in home care settings (Finlay et al. 2002; Higginson et al. 2003). Commissioning care is crucial, and work is underway at pilot sites to collect data to inform decisions on a new funding system. Public policy, supported by studies of patients' preferences, promotes systems to facilitate terminal care at home or in the preferred place of care (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence 2004; Gomes et al. 2013).

Specialist palliative care developed principally in hospice and acute settings (Clark 2007) although in many countries it has reached out into the community in various forms, and the value of community-based services is increasingly recognised by clinicians, academics and policy-makers (Department of Health 2008; National EOL Framework Forum 2010; Shaw et al. 2010; Howell et al. 2011). It is commonly found that the majority of patients wish to die at home (e.g. Higginson & Sen-Gupta 2000; Brazil et al. 2005; Gomes et al. 2013) and community-based care, delivered in the patient's own home, is associated with higher home death rates than institutional care (Collis & Al-Qurainy 2013; Luckett et al. 2013). In the UK, research tends to show strong support from general practitioners (GPs) for community palliative care services (Lloyd-Williams et al. 2000; Shipman et al. 2008; Hughes et al. 2010). On the whole, evidence suggests that home-based specialist care has outcomes at least as positive as those of hospice or hospital-based care (Luckett et al. 2013) although variations in intervention designs, populations and definitions of what counts as ‘specialist palliative care’ make it hard to be conclusive. A systematic review by Candy et al. (2011), for instance, found ‘home hospice’ care reduced general health care usage and increased patient and family satisfaction with care. A Canadian study found home care, following a Shared Care model, was associated with positive effects on patient anxiety, symptom and emotional distress (Howell et al. 2011).

Alongside the positive features of community palliative care, the delivery of palliative care services in patients' own homes creates some important challenges. Community palliative care typically involves a wide range of both specialist and generalist services; co-ordinating them to ensure effective collaborative working can be difficult (Shipman et al. 2008; King et al. 2010; Gardiner et al. 2012). Professionals are not always confident of their ability to control symptoms associated with end of life in the community (Grande et al. 1997). They may also find the demands of providing care in the home distressing – especially with the complex situations they can face in relation to informal carers and family members (Brazil et al. 2010).

Home-based care can result in substantial emotional, social and physical demands on informal carers (Higginson et al. 1990; Payne et al. 1999; Collis & Al-Qurainy 2013). This may explain why, despite their overall preference for home care, informal carers may be more favourable towards an institutional setting for end of life than patients (Brazil et al. 2005; Gomes et al. 2013). Patients may fear being a ‘burden’ on family carers (Gott et al. 2004; McPherson et al. 2007) and may be uncomfortable about the presence of professionals in their home (Gott et al. 2004). A recent review found that the most substantial area of unmet need for both patients and informal carers was effective communication with health professionals (Ventura et al. 2013). The ability of patients and informal carers to draw on their own personal networks for support is likely to be a significant factor in how well they cope (Brown & Walter 2013).

The need for new models of specialist palliative care provision at home seems clear. We present a study of the Midhurst Macmillan Specialist Palliative Care Service, which provides specialised hands-on palliative care in a community setting in an area of South-East England, UK. This service is distinct in that it is medical consultant-led and aims to deliver interventions in the home setting that are usually considered to require hospital admission.

Development of the Midhurst Macmillan Specialist Palliative Care Service

The Midhurst Macmillan Specialist Palliative Care Service is a medical consultant-led multi-disciplinary team, re-configured as a community service following the closure of the King Edward VII Hospital, West Sussex, UK in 2006 and modelled on the Motala hospital-based home care programme in Sweden (Beck-Friis & Strang 1993). The Midhurst service is one of only two in the UK that involves a medical consultant-led multi-disciplinary team that aims to provide round-the-clock, ‘hands-on’ care and advice at home, in community hospitals and in nursing or residential homes. The range of palliative interventions includes intravenous infusions, paracentesis and intrathecal analgesia. The service aims were: to put in place a sustainable and affordable specialist palliative care service for the population within the Midhurst and surrounding areas; to reduce acute hospital interventions and inpatient hospice stays; to ensure that patient choice is maximised by providing as much treatment and support in the home/community setting as possible; to achieve close working between the National Health Service, voluntary, charitable and private sectors; and to increase compliance with National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines.

Methods

Macmillan Cancer Support commissioned studies of the Midhurst Macmillan Specialist Palliative Care Service for three overall purposes: to determine whether the service was meeting its original aims; to gather financial evidence for commissioning; and to assess the extent to which the service could serve as a model for palliative care elsewhere.

Assessment of palliative care services, particularly when offered in a community setting, needs to take account of the context in which health care providers are working and to include perspectives from those receiving the service as well as those delivering it. We used a mixed methods approach to evaluate the service not only in terms of costs associated with care and use of other services, but also in terms of the views and experiences of patients and family carers in receipt of the Midhurst service, and of bereaved caregivers whose relatives had received the service. Since General Practice is crucial in the provision of end-of-life care at home, we sought to assess the quality of General Practice palliative care provision in the three Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) in which the Midhurst service operates.

We addressed five major areas of enquiry:

a retrospective analysis of secondary care use in the last year of life;

a financial evaluation of the Midhurst Macmillan Specialist Palliative Care Service using an Activity Based Costing approach;

a postal survey of palliative care systems and support in General Practices in the three PCTS;

qualitative interviews with patients, informal caregivers, health and social care staff and the Midhurst service staff and volunteers; and

a postal survey of bereaved caregivers who had used the Midhurst Macmillan Specialist Palliative Care Service.

Patient level activity and cost analysis

The study of economic and clinical activity was based on a retrospective analysis of anonymised data and included all patients who died from cancer within the 12-month period between August 2008 and August 2009 within the West Sussex, Surrey and Hampshire PCT areas in the south-east of England. Patients' use of healthcare services for the last 12 months of life was contrasted across three study groups: patients using the Midhurst service, patients using local hospices and those not known to have used either. These were localised to patients registered with a GP practice within a radius of 20 miles of Midhurst or the local hospices included in the study. Initial analysis used techniques to organise activity data into patient-specific, chronological ‘pathways’ describing use of secondary care (InPatient; OutPatient; Accident and Emergency) and the cost to commissioners of this care. Multiple parameters were then computed from this data set, for example survival post-referral; location of death; ‘pathway’ costs, number of inpatient admissions, days spent in an inpatient setting; frequency of attendance at Accident and Emergency departments.

The data set was further structured by creating subgroups to allow analysis of referral patterns. Three subgroups were created based on the number of inpatient stays prior to the known date of referral to either the Midhurst service or a Hospice. Group one were those referred prior to an inpatient stay; group two, those referred after one stay; and group three those referred after two or more stays. These categories were developed as a proxy of how early a patient is identified as needing palliative or supportive care.

Activity Based Costing Analysis

Using the Midhurst Macmillan Specialist Palliative Care Service's electronic record of clinical and administrative activity (SNOMED), combined with detailed financial accounting information, an Activity Based Costing Analysis was developed. This analysis accounted for the variety of different clinical team members delivering similarly coded activities with each patient. The output was a detailed mapping of the cost, by team member, of every Midhurst service activity from point of referral to end of life, thereby accounting for the totality of spend. This framework was then used to compute the precise cost of care delivered by the Midhurst service team to each patient in the study in the last year of life. This approach could not be replicated for patients under hospice care, where an estimate for cost of care has been computed and validated.

Postal survey of GPs

A postal survey of GP practices was included to illuminate the context of care in which the Midhurst Macmillan Specialist Palliative Care Service operates. GPs are delivering palliative care in conjunction with the Midhurst service as well as referring patients to it. We used the General Practice End of Life Care Index (GP-EoLC-I): a postal questionnaire on supportive and palliative care developed for an earlier national study (Hughes et al. 2010). The questionnaire provides data on reported clinical practice, views on palliative care services, participation in national initiatives and organisation of palliative care from the perspective of GPs. From this a summary measure of reported compliance with national guidance on palliative care can be computed. Senior partners in all GP practices in West Sussex, Surrey and Hampshire PCTs (418 practices) were sent GP-EoLC-I questionnaires. The sample included GP practices that referred to the Midhurst service and all others in the three PCTs. The initial mailing was in October 2010. Freepost envelopes were provided, and a schedule of regular reminders was used: two reminders to the GP partner followed by subsequent reminders to the practice manager.

Questionnaire data were analysed using PAS software, and statistics were prepared based on the model developed in our earlier study (Hughes et al. 2010). Comparison was made between those practices which referred patients to the Midhurst service, and those elsewhere in the three PCTs.

We obtained permission from the local ethics committee and research governance offices of the three local PCTs for the evaluation of the clinical service. National Health Service staff, patients and carers, and others gave informed consent to participate in the study.

Qualitative interview-based study of professional, patient and carer experiences of the Midhurst service

We examined experiences from the perspectives of the Midhurst service staff and volunteers, patients and carers, and other professionals with whom the Midhurst service staff collaborated. Interviews incorporated the ‘Pictor’ technique, an interview tool developed within our team, which is particularly useful in exploring relationships (King et al. 2013).

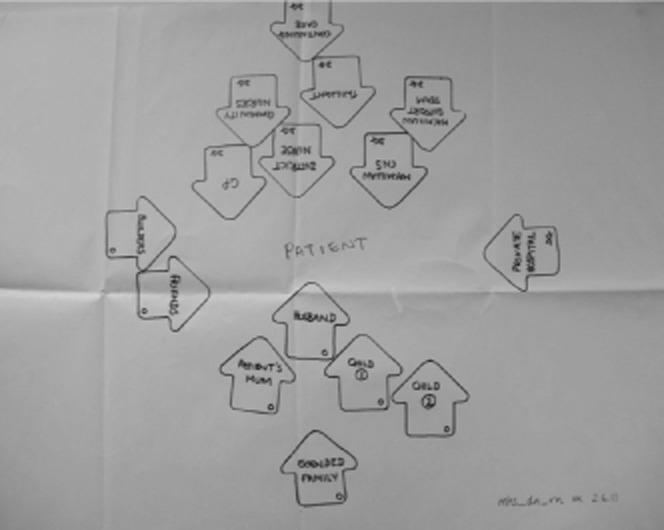

Pictor enables interviewees to represent individuals and/or agencies involved in care by arrow-shaped ‘post-it’ notes, which they configure on a large sheet of paper to describe their experience. The resulting chart forms a focus for exploration within the interview. An example of a Pictor chart is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

An example of a Pictor chart from an interview with a District Nurse.

Samples and recruitment

We recruited as many of the Midhurst service clinical team as possible, key managerial and administrative staff, and representatives of the main volunteer groups, through service management. We aimed to recruit patients currently receiving care from the Midhurst service and their main carer. Patients were excluded if the clinical team felt they would be too vulnerable to participate. Information packs were delivered by the clinical team, and replies came to them or directly to the researchers. Representatives of professions referred to in interviews were approached directly or recruited via their line managers.

We were able to recruit all available Midhurst service staff, and there was a high level of patient and carer willingness to participate. Community staff were selected from the area covered by the Midhurst service. Acute hospital staff proved the most difficult to recruit.

Thirty interviews were carried out with Midhurst service staff and volunteers. Roles were as follows: service managers (2); Clinical Nurse Specialists (6); Community Support Team (9); consultants (2); counsellor (1); occupational therapist (1); physiotherapist (1); Citizens' Advice Bureau financial adviser (1); secretary (1); volunteer co-ordinator (1); volunteer drivers (2); volunteer bereavement counsellors (2); and volunteer complementary therapist (1).

Twenty-one interviews were carried out with patients (11) and carers (10). These included nine patient/carer dyads.

Eighteen interviews were carried out with external staff. Roles were as follows: District Nurses (5); GPs (3); secondary care clinical nurse specialists (1); community hospital nurses (2); nursing home staff (2); private agency care workers (2); hospice services (2); and social worker (1).

Interview procedure

Midhurst service staff members and other health professionals were invited to describe their role and career history. We then explained the Pictor technique to them and invited them to select a case on which to base their chart. We talked through the case, with reference to the chart, probing for more detail as appropriate. We asked Midhurst service staff about their expectations for the future development of the service.

We asked patients and carers about their family situation, and the course of the illness, and explored their involvement with the Midhurst service. Next we asked them to create a Pictor chart depicting ‘their’ case. The charts were used to discuss the network of professional and lay people that they drew on for support, and the place of the Midhurst service team within this.

Analysis

All interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed using the template analysis style of thematic analysis (King et al. 2013). Our final coding template encompassed three main themes: How the Midhurst service works with external services; How the Midhurst service works with patients and carers; and Looking forwards. We also identified one integrative theme: What makes the Midhurst service special?

A retrospective postal questionnaire survey of bereaved caregivers

We further examined the experiences of those receiving the Midhurst service by carrying out a postal survey of bereaved carers whose relative had been referred to the Midhurst service, in order to widen the range of perspectives from patients and family members/carers receiving the service. We used VOICES (Views Of Informal Carers – Evaluation of Services), a self-complete postal questionnaire that includes sections on home, care-home, hospital and hospice, and has been widely used and found acceptable to respondents (Addington-Hall et al. 1998; Ingleton et al. 2004). VOICES provides data about patient experiences and care in the last 3 months of life as reported by their bereaved caregivers. It includes items on access to care; information giving; symptom control and quality of care across a range of settings. As there are further items on care in the last 3 days; choice and place of death; information and support for family/informal carers, and care in bereavement, VOICES also provides information on the support received by carers.

There were 280 deaths in the year from June 2010 to May 2011, and 252 carers of patients were contacted by letter by the Midhurst service between 3 and 5 months after bereavement. Those willing to receive the questionnaire replied directly to the research team. The questionnaire was then mailed out, with a covering letter including details of bereavement support contacts. A single reminder letter was sent to non-responders. The Midhurst service excluded any carer whose circumstances made contact inappropriate.

VOICES generates both quantitative survey data and qualitative comments. Descriptive statistics were prepared on the former, using PAS software version 19. The latter were subject to thematic analysis.

Results

The findings arising from the various elements of the evaluation are described below.

Economic analysis

The Midhurst Macmillan Specialist Palliative Care Service receives referrals for patients served by 19 general practices, with an estimated population of 155 000.

The study cohort was constructed from patients who died during the study period (August 2008–August 2009, with cancer as known cause of death, who could be matched to both the Public Health Mortality File and the Commissioning Data Set. This resulted in a 201-patient cohort for Midhurst, and 770 patients in the Hospice group.

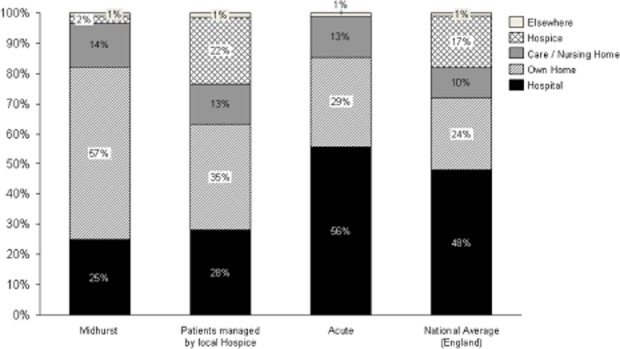

Place of death

Of the Midhurst service study group 71% of patients were facilitated to die at home or in a care home. This is very similar to the out-of-hospital deaths for the Hospice study group (70% – see Fig. 2). A relevant nationwide estimate for out of hospital deaths in England is 52% (National End of Life Care Intelligence Network 2010).

Figure 2.

Location of death for each of the care models.

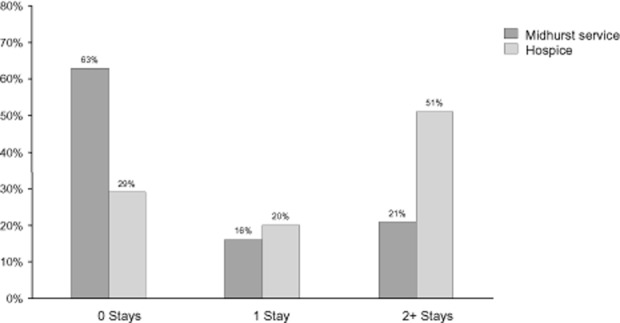

Referral patterns

The proportions of the study groups by referral subgroup are presented in Figure 3. The majority of patients are referred to the Midhurst service prior to an inpatient stay (63%), whereas referrals to Hospices were typically made after the 2nd or further inpatient stays (51%). The detailed results of clinical and activity and cost are presented for both Midhurst-referred and Hospice-referred patients. No evidence of patient selection for referral was found. The population under the care of the Midhurst service represents essentially the total population of patients receiving community-based palliative care for the patch.

Figure 3.

Distribution of patients by referral timing – number of inpatient stays prior to referral.

Referral subgroup ‘Before’: Patients referred prior to an inpatient stay had a median post-referral survival of 10.4–10.6 weeks. Those patients using Midhurst spent substantially less time in hospital (3.3 vs. 10.9 days) and had fewer attendances at hospital Accident and Emergency Departments (0.4 vs. 0.6). Outpatient attendances were, however, higher for the Midhurst service group (9.4 vs. 4.2).

Referral subgroup ‘1 stay’: Post-referral survival for this population was identical for the two settings (6.7 weeks). Similar patterns of reduced inpatient activity were observed (days in inpatient setting 7.0 vs. 10.3). Attendances at hospital Accident and Emergency Departments were equivalent (0.5 vs. 0.4). Outpatient use was found again to be higher for the Midhurst patients (4.8 vs. 3.4), though less marked.

Referral subgroup ‘2+ stays’: Post-referral survival differed numerically, but not statistically significantly between the two settings (10.4 vs. 5.6 weeks). For this subgroup we observed an increased number of days in an inpatient setting for the Midhurst patients (13.3 vs. 9.1). When length of survival was included the same ratio of 1:9 was computed for both groups (i.e. 1 day in hospital for every 10 days of survival). Use of hospital Accident and Emergency Departments was similar for the two study groups, and substantially less than for the population not referred for palliative care (0.4 vs. 0.4 vs. 0.9). Outpatient use was numerically lower for the Midhurst service patients (3.3 vs. 3.6).

Pathway cost analysis

Activity-based costing for the Midhurst service revealed a mean per-patient service cost of between 1655 GBP (1910 EUR) and 1888 GBP (2179 EUR) depending on the Referral subgroup (see Table 1). Using secondary sources (Marie Curie 2008), we estimated the per-patient cost for Hospices to be in the order of 3941 GBP (4549 EUR). This estimate was reviewed by the participating Hospices. Pre-referral costs increase substantially from 2500 GBP (2888 EUR) to 9400 GBP (10 863 EUR) across the three subgroups, as a function of referral timing. For the Hospice patients, post-referral system costs are lower than for the Midhurst service patients: Hospices substitute for more post-referral activity. The longer survival of the Midhurst service patients in the 2+ stay group may be driving the higher observed costs.

Table 1.

Mean cost of care per patient in the last year of life (k GBP) by service model and referral subgroup

| ‘Before’ |

‘After 1 stay’ |

‘After 2+ stays’ |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Midhurst service | Hospices | Midhurst service | Hospices | Midhurst service | Hospices | |

| Pre | 2.8 | 2.5 | 5.2 | 4.6 | 8.8 | 9.4 |

| Post | 4.7 | 3.5 | 3.4 | 2.3 | 5.4 | 2.7 |

| Service | 1.9 | 3.9 | 1.7 | 3.9 | 1.9 | 3.9 |

| Total | 9.4 | 10.1 | 10.2 | 10.9 | 16.0 | 16.0 |

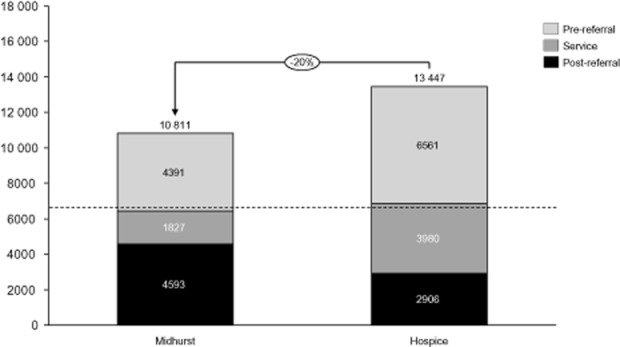

Economic gains

Total costs in the last year of life were substantially lower when referral was made either before, or after only the first, inpatient stay (9400 GBP/10 863 EUR vs. 1600 GBP/10 863 EUR). This is regardless of whether the referral was made to the Midhurst service or to a Hospice. Referral patterns do, however, differ markedly: the majority of the Midhurst service referrals being made before an inpatient stay (see Fig. 3). Based on these characteristics of the Midhurst service, the overall financial impact for the health economy is reduced by 20% due to the avoidance of pre-referral costs (see Fig. 4). Restated: the total healthcare system costs would be 24% greater if referrals to the Midhurst service resembled those being made to Hospice-led care. While each patient referred to the Midhurst service may incur cost to the commissioners of 1900 GBP (2192 EUR), the prevention of costs of secondary care activity is of the order of 6000 GBP (6924 EUR) per patient.

Figure 4.

Simulated total system costs of Midhurst and hospice-led care for a cohort of 1000 patients based on estimated pre-referral, post-referral and service costs.

Findings from the Primary Care Survey

Two hundred and thirty-two (55.5%) General Practices returned completed questionnaires. Nineteen were practices which referred patients to the Midhurst Macmillan Specialist Palliative Care Service (who were to be found in all three PCTs), and 213 were practices which did not. When a range of quality indicators derived from the survey questionnaire were analysed, the GP palliative care provision in the practices referring to the Midhurst Macmillan Specialist Palliative Care Service provided a picture of care commensurate with provision throughout the three PCTs.

Professional, patient and carer experiences of the Midhurst Macmillan Specialist Palliative Care Service

Key findings from qualitative interviews are summarised here.

How the Midhurst service works with external services

Collaborative working was described as being essential to the Midhurst Macmillan Specialist Palliative Care Service approach; the nature of the collaboration varies between and within cases, their role being more prominent in complex cases. Midhurst staff are very aware of the danger of ‘stepping on the toes’ of other professionals, but both they and the other professionals described such difficulties as declining as the service became better known, and reported very good working relationships in most cases. The patch-based organisation of Clinical Nurse Specialists helped these senior nurses get to know and establish good working relationships. Patients and carers generally appeared to regard their professional attendants as working together.

Examples from the interviews:

For instance I've just had a patient who's post chemo, she has to have an injection called GCSF which boosts her white blood cell count, so she has to have five of those, one a day, so I've managed to do two of those and the District Nurses handled the other three. (Midhurst Clinical Nurse Specialist)

It's the liaison that is absolutely, really strong, so strong, really helpful. (Patient)

How the Midhurst service works with patients and carers

The Midhurst service's team commitment to holistic approach to care, which takes account of the family and wider social context, was frequently confirmed in patient and carer interviews. For example, one patient said:

Medicine is worried about the tumour, that's what they're interested in … I think [names Midhurst service staff member] comes into it because I think she looks after our sort of total being.

Observation and interviews both pointed to the Midhurst service's flexible and holistic care. This appears to be a factor allowing GPs and hospital consultants to refer patients early in their illness and has avoided stigmatising the service as principally concerned with the dying. The range of clinical interventions – some preventing the need for travel or admission to hospital or hospice – appear to promote confidence in home care as disease progresses. Patients and carers were very positive about the supportive and personal nature of the care, identifying staff as playing a key role in enabling them to cope with their difficult circumstances. Interviews with the Midhurst service team, showed a commitment to their seeing involvement with patients and carers as an opportunity for learning and development.

Examples from the interviews:

I think people have a sort of view that palliative care is something that is sort of end stage, and that's certainly not the case, we support them all the way along. (Midhurst Community Support Team)

[My wife] trusts her too and I think that's important because if things did decide to go wrong I would like to feel like [my wife] had got somebody that she knew quite well and that she could talk to and if the worse came to the worse you know, she'd be there afterwards as well. (Patient)

He [patient] did as much for our service as we did for him, we cut our teeth on him in lots of ways … and the girl that had platelets, I mean we hadn't, they had done one, a couple of lots of platelets, but never to that extent, and the fact that we could actually do, manage things and there was a lot of learning and helping the staff through learning, yeah. (Midhurst staff member)

Looking forwards

There was a strong consensus among team members and patients and carers that there was no need for radical change, but rather for extending the service.

I think they should double the service […] it should be more widely [available] – it seems like quite a small organisation, the Midhurst service, it's not really enough. (Patient)

The most commonly mentioned specific areas were the wish to offer a full out-of-hours service, and to be able to take over continuing care services. Access to, and continuity of, continuing care services emerged as an important issue across all participant groups, including patients and carers.

For example:

I wish we could keep the patients … when we first go in like at a crisis and help out, you know, with personal care and things like that, and then they're assessed that it's more longer term perhaps and they go to continuing health care or something like that. I wish that, you know, we could keep them, but I don't think we could because we cover three areas. (Midhurst Community Support Team)

Despite anxiety about the future in the light of announcement of significant reforms to the UK National Health Service (NHS), there was a feeling that the service was well-placed to succeed in the future, given its good links with local GPs and ability to address key policy priorities in end-of-life care (Department of Health 2008, 2009).

Integrative theme: what makes the Midhurst service ‘special'?

Throughout the interviews a perception was evident that the Midhurst service was ‘special’. In part this related to the range of support the service could offer from both professionals and volunteers. As important, though, were the ethos and dynamics of the team. Members emphasised the non-hierarchical and flexible working relationships, with tasks being performed by the nearest competent professional and by those familiar to the patient, and the willingness to learn from each other. Medical staff were available for complex consultations at patients' homes. Volunteers fulfilled many important roles and were well employed within the service. None of these characteristics is unique, but members felt that this combination was distinctive to the Midhurst service team. The team's ability to function in this way was facilitated by effective local clinical management and minimal interference in the day-to-day running of the service from higher managerial levels in the National Health Service.

Examples from the interviews:

I was having to go down to Portsmouth to get these [blood transfusions] done, and I looked around to see if there was any method of doing this … and so I met [Midhurst consultant] and he said ‘why don't you get the Macmillan Nurse’, and that's how I got involved with them, and from then on they did it. (Patient)

I don't feel there's any hierarchy as such, which I mean that in a positive way, you know: the Consultants, the CNSs [Clinical Nurse Specialists], the Clinical Support Team, we all try and work as one, and there's no fear of asking questions if you don't know anything. (Midhurst Community Support Team)

Finding from the VOICES survey

One hundred and two (40.5%) bereaved caregivers of patients who had been referred to the Macmillan Midhurst Specialist Palliative Care Service returned completed postal questionnaires. Almost all (100/102) respondents reported that their relative had spent time at home in their last 3 months. Sixty-seven per cent of people were cared for at home (57%) or in a care home (10%) for their last 3 days of life.

Bereaved carer satisfaction with services at home

The great majority (74%) of caregivers reported that they received care from two or more nursing services: the Midhurst Macmillan service and District Nurses being the most common combination (51%). Seventeen per cent named the Midhurst service only, 6% another nursing service only, and 3%, surprisingly, reported no nursing care received.

A substantial majority (83%) of respondents to the VOICES survey reported services at home to be excellent or good. Seven per cent said it was fairly good, and 5% that it was poor (5% other replies). Positive experiences predominated in the comments on care quality. A majority (78%) reported that they received as much support as they wanted. Twelve per cent reported some support but not as much as they wanted; 6% not enough support but had not asked; and 2% not enough support although they had tried (2% other replies/missing).

Almost half (49%) of respondents reported the caring experience as rewarding, with 7% saying it was a burden, and 28% that it was equally balanced (14% other replies/missing). Forty-three per cent of respondents had given up or reduced their work in order to look after their relative, underlining the importance of informal caregivers in care at home. This factor was further emphasised in a question on personal care, where 23% reported that their relative did not need this kind of care (some of the qualitative comments indicate that this was because family members were providing the care). In the final 3 months 24% reported that personal care needs were never or only sometimes met, whereas in the last 3 days of life, 6% reported that there was not enough help to meet personal needs. Confidence of informal carers in looking after their relative was varied: 32% felt very confident; 46% fairly confident; and 15% not confident (7% other replies/missing).

A majority (75%) reported GP care to be excellent (58%) or good (17%), with 14% describing it as fair, and 9% as poor (2% other replies). GPs were reported as very understanding by 73% of respondents, as fairly understanding by 15% and not very understanding by 9% (3% other replies/missing).

Place of death

Sixty-seven per cent died at home (58%) or in a care home (9%). A substantial majority (86%) of respondents felt that their relative had died in the right place: for deaths at home/care home, 66 of 67 respondents said this (one was unsure). Bereavement care (in which the Midhurst service was prominent) was reported to have been taken up by 47% of respondents and found helpful by 90%. Twenty per cent of those who had not received such care felt they would have wanted it.

Bad experiences

Despite an overall positive response to VOICES; reports of bad experiences illustrate failures of service for some of those cared for at home. Twenty-two per cent of bereaved carers reported that there were ways in which health and social services could have helped to make the last 3 months of life easier for their relative. Not receiving services or late referral to services was one important issue along with inadequate GP cover and poor continuity, particularly with out-of-hours services. Across all these settings, the issue of personal needs not being met could indicate a deficiency in the resource available for basic nursing care.

Discussion

This study represents a comprehensive evaluation of the Midhurst Macmillan Specialist Palliative Care Service. Overall in a number of key areas it seems clear that the Midhurst service has achieved its aims in line with current policy and with patient and professional wishes on place of care and death. The figure of 71% of patients dying at home is very much higher than that seen elsewhere. The quality of care is good, as reported by patients and their current informal caregivers, as well as bereaved caregivers. Interviews using the Pictor technique revealed strong team functioning and effective collaborative working with other services. Patients using this service made less use of hospital inpatient services, and had fewer attendances at Accident and Emergency departments.

The positive findings from the Midhurst study raise the question of whether services in other areas could be configured in a similar way and produce similar outcomes. Gomes et al. (2009) have drawn attention not only to the differences between care models, expectations and funding in different parts of the world, but also to the need for more research into costs and outcomes. Costs of services in end-of-life care are complex to assess. In particular the contributions made by different services to deliver care to individual patients is not currently recorded, and this is the subject of a data gathering exercise in the UK, in the Palliative Care Funding Review Pilots (Department of Health 2011a,b). These caveats reinforce the need for caution in interpreting our findings.

Evidence from a comparable well-established service in Cumbria, UK (Hospice at Home West Cumbria 2007) suggests that this model is capable of serving a greater proportion of patients with a diagnosis other than cancer. This would depend on referrals of patients with chronic conditions and the Midhurst service finding ways to substitute for hospital inpatient or outpatient or day-care. Published work indicates that the future need for end-of-life care can only increase (Gomes & Higginson 2008).

Two significant limitations can be identified in the financial data collected on the service. First, we were not able to collect data on the extent of the involvement of primary care services, and hence this element could not be costed accurately. Second, we were not able to obtain detailed data on costs of care in the hospices surrounding the Midhurst service areas but made use of nationally available data on hospice costs (Marie Curie 2008) which may not reflect actual costs in the area of the evaluation. Regarding the interview data, we have limited material from the acute sector, and this may have altered the picture of the service that we obtained. Additionally, the qualitative interviews may have suffered from selection bias, with the possibility that those with favourable experiences were more likely to participate. Note, though, that selection bias was not an issue with the respondents from the Midhurst staff, as all members of staff available at the time were interviewed.

Nevertheless, some comments can be made on the financial findings in the Midhurst Macmillan Specialist Palliative Care Service. For individual patients in the Midhurst service study, the overall cost to the health economy is similar for a patient referred either to the Midhurst service or to a hospice-model of care. Meaningful economic savings in the order of 20% could be made, however, through earlier access to community-based specialist palliative care, which may be facilitated via a Midhurst-type model.

The issue of patients' preferred place of care and death has been the subject of much discussion, with home reported as the preference of the majority (Higginson & Sen-Gupta 2000; Office for National Statistics 2011). However, changes in preference over time have been reported by some (Munday et al. 2009), and Thomas et al. (2013) found a stronger than expected preference for hospice care in their study. Gomes and Higginson (2006) report ‘living with relatives’ and ‘having extended family support’ as two of six factors strongly associated with home death for cancer patients: neither of these are factors which services can supply. Geographical differences in the UK have been highlighted in the Grim Reaper's Roadmap, (Shaw et al. 2008); and proximity to facilities has been reported as related to dying in those facilities (Gatrell et al. 2003).

Jünger et al. (2007) explored multiprofessional working and palliative care, and reported the emphasis given to close communication between team members in producing co-operative working. The flexibility of roles of the team members is reported as a key aspect of the Midhurst Macmillan Specialist Palliative Care Service by patients, carers and staff themselves. Qualitative explorations of the experiences of patients and their caregivers suggest that carers particularly value accessibility and support that enables them to provide care at home (Grande et al. 2004), while patients give greater emphasis to psychosocial aspects such as communication and kindness (Grande et al. 1996). Our data indicate that all these are present in the Midhurst Macmillan Specialist Palliative Care Service.

From our data we identified a number of factors that we believe have an impact on the success of the service. These are: the breadth of services that are delivered at home; role flexibility; and early referral. The breadth of services and the earlier referral provide the opportunity to develop a relationship of trust between the patient, carers, family members and the team. The Midhurst service's openness to accepting patients receiving ongoing treatment (chemotherapy or radiotherapy) allows early referral: consequently there are higher numbers of outpatient attendances than are seen in hospice patients. Relationships with other services were found to be sound, functional and supportive, and this was recognised by patients. The model of early referral to palliative care alongside oncological treatment has been the subject of a clinical trial indicating favourable outcomes in terms of quality of life and survival (Temel et al. 2010).

It might be argued that there are factors that are particular to the Midhurst area that favour the delivery of a high-quality service at home. However, we did not find that GP Practices reports of their palliative care provision differed between practices in the Midhurst area and those elsewhere in the three local PCTs. However, when we compared the current reports from Practices in West Sussex, Hampshire and Surrey PCT with those in our earlier national survey (Hughes et al. 2010), these PCTs appeared to be more advanced in their participation in national initiatives when compared with the rest of England, and also scored significantly higher in quality indicators of palliative care provision, suggesting the possibility of above average support for community palliative care.

Midhurst is not untypical of other UK areas in terms of funding, care environment and patient groups, although the distance to inpatient palliative care facilities from the Midhurst areas may favour the choice of care at home, since proximity to facilities has been reported as related to dying in those facilities (Gatrell et al. 2003), and one feature of the Midhurst area is the replacement of a previous inpatient facility by the current service. In the current study we were not able to explore factors such as ‘living with relatives’ and ‘having extended family support’, as reported by Gomes and Higginson (2006), but did not encounter evidence to suggest the Midhurst area was unusual in this respect.

The study has not led us to conclude that the characteristics of patients using the Midhurst service are the result of referrer-level selectivity. Interviews with referrers suggest that the Midhurst service is the service they refer to systematically for patients in their practice area. The Midhurst service has good access to a volunteer workforce, but so does the service in Cumbria, an area in North-West England where social deprivation is a significant feature (Hospice at Home West Cumbria 2007). Responses from the bereaved carer survey sound a note of caution by emphasising that the role of informal carers continues to be central to care of patients at home.

Overall there do not appear to be special features of the Midhurst area that are particularly advantageous to the service. It seems reasonable to ascribe the favourable outcomes to the Midhurst Macmillan Specialist Palliative Care Service itself, and particularly to its configuration, raising the question of whether services in other areas could be configured in a similar way and produce similar outcomes. Our suggestion is that it is likely that the Midhurst model could be established in other areas. However, to achieve this we would draw attention to the particular features of the service which our study has identified as having an impact on the success of the service in delivering good-quality palliative care at home, and enabling a high proportion of patients to die at home. These features are the breadth of services that are delivered at home; role flexibility; and early referral. In the Midhurst service the effective local clinical management, with minimal intervention from higher managerial levels was key to the way the team worked. Developing these would be a prerequisite for expanding or establishing services, as well as attending to the context in which a service is operating.

Conclusions

This study found that 71% of patients cared for by the Midhurst Macmillan Specialist Palliative Care Service had died at home. The mean cost is about 3000 GBP (3461 EUR) per patient. The study quantified the cost of care in the last year of life for patients with cancer accessing community-based specialist palliative care. Specifically for the Midhurst service this was estimated at around 1900 GBP per patient (2192 EUR). The major source of cost variation occurred pre-referral, with incremental cost of around 6000 GBP (6924 EUR) associated with later referral.

Evidence from bereaved carers suggests that they receive good or excellent support from the Midhurst service. Reports by patients, carers and bereaved carers point to satisfaction with the Midhurst service when it has played a major role in end-of-life care. However, some carers reported the problem of the period of hands-on care for some patients being short, with care switched to Continuing Health Care at a late stage. This suggests that Midhurst-style services should include sufficient care assistants to cover the whole course of a patient's terminal illness.

The Midhurst service was not reliant on high-quality primary care, but complementary to other services, operating at a secondary care level and filling gaps in existing community service provision. Further, it is likely that flexibility of the individuals concerned within the Midhurst team was crucial, and necessary for the model to work. Given the likely increased demand for specialist palliative care, the Midhurst Macmillan Specialist Palliative Care Service model may represent an efficient way of expanding capacity without incurring significant capital costs.

Our study suggests several priorities for further research into specialist palliative care in the community. Closer examination of the factors enabling relatively early referral to community-based services would be valuable, given that this appears to be an important contributor to the success of the Midhurst service. Longitudinal research following patients and carers from referral to the service up to death would deepen our understanding of how they and their carers relate to services and draw on personal and professional networks for support. Finally, research into the economics of such services would be strengthened by the ability to capture accurate and service-specific primary care and hospice service use data.

Acknowledgments

We extend our thanks to all patients, carers, professionals and volunteers who provided data for the study. Our thanks also go to Mrs Deirdre Revill and Mrs Jacquie Gath, of the North Trent Cancer Network Consumer Research Panel, who provided advice throughout the study, and to Macmillan Cancer Support who funded the study. At the time of the study and reporting, Ashley Woolmore was a partner at Monitor Group, France; Jane Melvin and Alison Bravington were Senior Research Fellow and Research Assistant respectively in the Centre for Applied Psychological Research, University of Huddersfield; and Philippa Hughes and Michelle Winslow were Research Fellow and Research Associate respectively in the Academic Unit of Supportive Care, Department of Oncology, University of Sheffield.

References

- Addington-Hall J, Walker L, Jones C, Karlsen S. McCarthy M. A randomised controlled trial of postal versus interview administration of a questionnaire. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1998;52:802–807. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.12.802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck-Friis B. Strang P. The organization of hospital-based home care for terminally ill cancer patients: the Motala model. Palliative Medicine. 1993;7:93–100. doi: 10.1177/026921639300700202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazil K, Howell D, Bedard M, Krueger P. Heidbrecht C. Preferences for place of care and place of death among informal caregivers of the terminally ill. Palliative Medicine. 2005;9:492–499. doi: 10.1191/0269216305pm1050oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazil K, Kassalainen S, Ploeg J. Marshall D. Moral distress experienced by health care professionals who provide home-based palliative care. Social Science and Medicine (1982) 2010;71:1687–1691. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown L. Walter T. Towards a social model of end-of-life care. British Journal of Social Work. 2013 & doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bct087. [Google Scholar]

- Candy B, Holman A, Leurent B, Davis S. Jones L. Hospice care delivered at home, in nursing homes and in dedicated hospice facilities: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2011;48:121–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark D. From margins to centre: a review of the history of palliative care in cancer. The Lancet Oncology. 2007;8:430–438. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collis E. Al-Qurainy R. Care of the dying patient in the community. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 2013;347:f4085. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. 2008. End of Life Care Strategy promoting high quality care for all adults at the end of life. London, UK, Department of Health: July 2008. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_086277.

- Department of Health. 2009. End of Life Care Strategy: First Annual Report. London, UK, Department of Health. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/dh_10244.pdf.

- Department of Health. 2011a. Funding the right care and support for everyonePalliative Care Funding Review. London. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/215107/dh_133105.pdf.

- Department of Health. 2011b. Briefing NotesPalliative Care Funding Pilots (2012–14). Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/palliative-care-funding-pilots-2012-14.

- Finlay IG, Higginson IJ, Goodwin DM, Cook AM, Edwards AGK, Hood K, Douglas H-R. Normand CE. Palliative care in hospital, hospice, at home: results from a systematic review. Annals of Oncology. 2002;13(Suppl. 4):257–264. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf668. &. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner C, Gott M. Ingleton C. Factors supporting good partnership working between generalist and specialist palliative care services: a systematic review. The British Journal of General Practice. 2012;62:e353-62. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X641474. &. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X641474.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatrell AC, Harman JC, Francis BJ, Thomas C, Morris SM. McIllmurray M. Place of death: analysis of cancer deaths in part of North West England. Journal of Public Health Medicine. 2003;25:53–58. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdg011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes B. Higginson IJ. Factors influencing death at home in terminally ill patients with cancer: systematic review. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 2006;332:515–521. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38740.614954.55. 332& [erratum; 2006;; 1012]2006. doi: 10.1136/BMJ38740.614954.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes B. Higginson IJ. Where people die (1974–2030): past trends, future projections and implications for care. Palliative Medicine. 2008;22:33–41. doi: 10.1177/0269216307084606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes B, Harding R, Foley KM. Higginson IJ. Optimal approaches to the health economics of palliative care: report of an international think tank. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2009;38:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes B, Calanzani N, Gysels M, Hall S. Higginson IJ. Heterogeneity and changes in preferences for dying at home: a systematic review. BMC Palliative Care. 2013;12:7. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-12-7. &. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-12-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gott M, Seymour J, Bellamy G, Clark D. Ahmedzai S. Older people's views about home as a place of care at the end of life. Palliative Medicine. 2004;18:460–467. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm889oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grande GE, Todd CJ, Barclay SIG. Doyle JH. What terminally ill patients value in the support provided by GPs, district nurses and Macmillan nurses. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 1996;2:138–143. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.1996.2.3.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grande GE, Barclay SIG. Todd CJ. Difficulty of symptom control and general practitioners' knowledge of patients' symptoms. Palliative Medicine. 1997;11:399–406. doi: 10.1177/026921639701100511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grande GE, Farquhar M, Barclay SIG. Todd CJ. Valued aspects of primary palliative care: content analysis of bereaved carers' descriptions. British Journal of General Practice. 2004;54:772–778. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higginson IJ. Sen-Gupta GJA. Place of care in advanced cancer: a qualitative systematic literature review of patient preferences. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2000;3:287–300. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2000.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higginson IJ, Wade A. McCarthy M. Palliative care: views of patients and their families. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 1990;301:277–281. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6746.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higginson IJ, Finlay IG, Goodwin DM, Hood K, Edwards AK, Cook AL, Douglas H-R. Normand CE. Is there evidence that palliative care teams alter end-of-life experiences of patients and their caregivers? Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2003;25:150–168. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00599-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hospice at Home West Cumbria. 2007. Annual Report: 2006/2007 Hospice at Home West Cumbria. Available at: http://www.hospiceathomewestcumbria.org.uk/

- Howell D, Marshall D, Brazil K, Taniguchi A, Howard M, Foster G. Thabane L. A shared care model pilot for palliative home care in a rural area: impact on symptoms, distress, and place of death. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2011;42:60–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes PM, Bath PA, Ahmed N. Noble B. What progress has been made towards implementing national guidance on end of life care? A national survey of UK general practices. Palliative Medicine. 2010;24:68–78. doi: 10.1177/0269216309346591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingleton C, Morgan J, Hughes P, Noble B, Evans A. Clark D. Carer satisfaction with end-of-life care in Powys, Wales: a cross-sectional survey. Health and Social Care in the Community. 2004;12:43–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jünger S, Pestinger M, Elsner F, Krumm N. Radbruch L. Criteria for successful multiprofessional cooperation in palliative care teams. Palliative Medicine. 2007;21:347–354. doi: 10.1177/0269216307078505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King N, Melvin J, Ashby J. Firth J. Community palliative care: role perception. British Journal of Community Nursing. 2010;15:91–98. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2010.15.2.46399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King N, Bravington A, Brooks J, Hardy B, Melvin J. Wilde D. The Pictor Technique: a method for exploring the experience of collaborative working. Qualitative Health Research. 2013;23:1138–1152. doi: 10.1177/1049732313495326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Williams M, Wilkinson C. Lloyd-Williams F. General Practitioners in North Wales: current experiences of palliative care. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2000;9:138–143. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2354.2000.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckett T, Davidson PM, Lam L, Phillips J, Currow DC. Agar M. Do community specialist palliative care services that provide home nursing increase rates of home death for people with life-limiting illnesses? A systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2013;45:279–297. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marie Curie. 2008. A Descriptive Analysis of the Impact and Costs of the Marie Curie Delivering Choice Programme in Lincolnshire. King's Fund 2008. Available at: http://www.mariecurie.org.uk/Documents/HEALTHCARE-PROFESSIONALS/Improving_choice1.pdf.

- McPherson CJ, Wilson KG. Murray MA. Feeling like a burden: exploring the perspectives of patients at the end of life. Social Science and Medicine (1982) 2007;64:417–427. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munday D, Petrova M. Dale J. Exploring preferences for place of death with terminally ill patients: qualitative study of experiences of general practitioners and community nurses in England. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 2009;338b:2391. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2391. &. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National End of Life Care Intelligence Network. 2010. August ( Variations in Place of Death in England. Inequalities or appropriate consequences of age, gender and cause of death? Available at: http://www.endoflifecare-intelligence.org.uk/resources/publications.aspx.

- National EOL Framework Forum. 2010. Canberra, Australia: Palliative Care AustraliaHealth system reform and care at the end of life: a guidance document.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. 2004. March 2004, London, UKImproving Supportive and Palliative Care for Adults with Cancer.

- Office for National Statistics. 2011. National Bereavement Survey (VOICES). Available at: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/subnational-health1/national-bereavement-survey–voices-/2011/stb-statistical-bulletin.html.

- Payne S, Smith P. Dean S. Identifying the concerns of informal carers in palliative care. Palliative Medicine. 1999;13:37–44. doi: 10.1191/026921699673763725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw KL, Clifford C, Thomas K. Meehan H. Improving end-of-life care: a critical review of the Gold Standards Framework in primary care. Palliative Medicine. 2010;24:317–329. doi: 10.1177/0269216310362005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw M, Thomas B, Smith GD. Dorling D. The Grim Reaper's Road Map: An Atlas of Mortality in Britain. Bristol, UK: The Policy Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Shipman C, Gysels M, White P, Worth A, Murray SA, Barclay S, Forrest S, Shepherd J, Dale J, Dewar S, Peters M, White S, Richardson A, Lorenz K, Koffman J. Higginson IJ. Improving generalist end of life care: national consultation with practitioners, commissioners, academics, and service user groups. British Medical Journal. 2008;337:a1720. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzilansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, Dahlin CM, Blinderman CD, Jacobson J, Pirl WF, Billings JA. Lynch TJ. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C, Morris SM. Clark D. Place of death; preferences among cancer patients and their carers. Social Science and Medicine (1982) 2004;58:2431–2444. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura AD, Burney S, Brooker J, Fletcher J. Ricciardelli L. Home-based palliative care: a systematic literature review of the self-reported unmet needs of patients and carers. Palliative Medicine. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0269216313511141. & doi: 10.1177/0269216313511141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]