Summary

Regulation of p53 by ubiquitination and deubiquitination is important for its functions. In this study, we demonstrate that USP24 deubiquitinates p53 in human cells. Functional USP24 is required for p53 stabilization and p53 destabilization in USP24 depleted cells can be corrected by the forced expression of USP24. We show that USP24 depletion renders cells resistant to apoptosis after UV irradiation, consistent with the requirement of USP24 for p53 stabilization and PUMA activation in vivo. Additionally, purified USP24 protein is able to cleave ubiquitinated p53 in vitro. Importantly, cells with USP24 depletion exhibited significantly elevated mutation rates at the endogenous HPRT locus, implying an important role for USP24 in maintaining genome stability. Our data reveal that the USP24 deubiquitinase regulates the DNA damage response by directly targeting the p53 tumor suppressor.

Introduction

The tumor suppressor p53 functions as a stress sensor to protect genome integrity and, reasonably, is mutated in more than half of human cancers (Lane and Levine, 2010; Vogelstein et al., 2000). p53 integrates multiple stress signals into a series of diverse antiproliferative responses, one of which is to activate apoptosis when cells are under stress. Indeed, the p53-PUMA (p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis) axis is a major regulator of DNA-damage-induced apoptosis (Danial and Korsmeyer, 2004; Jeffers et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2009). Disruption of p53 function process can promote tumor progression and chemoresistance (Muller and Vousden, 2013; Wade et al., 2013).

Posttranslational modifications are known to regulate p53 stability, activity and localization; in particular the ubiquitination and deubiquitination pathways have emerged as dynamic and coordinated processes regulating p53 functions. As a very short-lived protein in the cell, p53 is constantly degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Mdm2 acts as the major E3-ubiquitin ligase targeting p53 for degradation (Haupt et al., 1997; Honda et al., 1997; Kubbutat et al., 1997). p53 degradation is inhibited after cellular stress, allowing activated p53 to regulate a variety of cellular functions, including DNA repair, cell cycle progression and apoptosis (Lee and Gu, 2010; Marine and Lozano, 2010).

Ubiquitin-specific deubiquitinases (DUBs) play important roles in various cellular processes (Reyes-Turcu et al., 2009). Intriguingly, several DUBs have been identified to control p53 levels. HAUSP (USP7) was the first deubiquitinase identified to target p53 and Mdm2 for deubiquitination (Cummins and Vogelstein, 2004; Li et al., 2004). USP2a specifically deubiquitinates Mdm2 and MdmX (Allende-Vega et al., 2010; Stevenson et al., 2007). In contrast to HAUSP and USP2a, USP10 appears to specifically deubiquitinate p53 because knockdown of USP10 in HCT116 p53-/- cells does not cause Mdm2 reduction (Yuan et al., 2010). Importantly, USP10 can be phosphorylated by the ATM kinase, leading to its stabilization and nuclear translocation. Similarly, USP42 is a p53-specific deubiquitinase and plays a role in DNA damage-induced p53 stabilization (Hock et al., 2011). Taken together, the varying actions of these deubiquitinases allow for dynamic p53 regulation in a context-dependent manner.

USP24 is a 2620 amino acid ubiquitin-specific protease, containing several conserved domains, including a UBA domain (ubiquitin-associated domain), a UBL domain (ubiquitin-like domain), and a USP domain (ubiquitin-specific protease domain) (Komander et al., 2009). Our group previously reported that ubiquitinated DDB2 can be targeted by USP24 (Zhang et al., 2012), and in this study, we demonstrate that USP24 is a p53 deubiquitinase, required for p53 stabilization in unstressed cells, as well as for p53 stabilization and PUMA activation after DNA damage.

Results

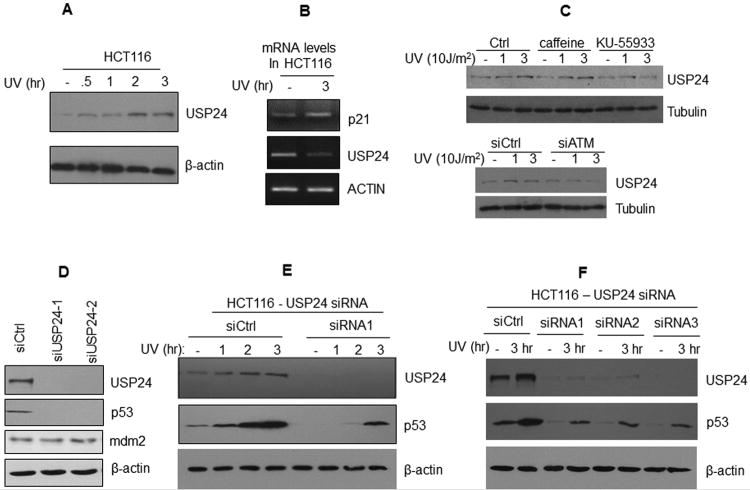

Up-regulation of the USP24 protein after DNA damage

In a yeast-two-hybrid screen, we identified that USP24 interacts with the UV damage binding protein DDB2, a subunit of the CUL4-DDB1DDB2 ubiquitin ligase (Zhang et al., 2012). Here we found that USP24 protein levels increased in HCT116 cells after UV-C irradiation (Figure 1A). This up-regulation of USP24 after UV irradiation was also observed in several other human cancer cell lines, including U2OS, 293T and MCF7 cell lines (Figure S1), suggesting that USP24 up-regulation is not cell line specific. Interestingly, transcription of USP24 was not induced after UV irradiation (Figure 1B), suggesting that unlike the p53 target p21, which is transcriptionally induced by UV (Figure 1B), USP24 up-regulation after UV irradiation occurs at a post-transcriptional level. Moreover, UV induced USP24 accumulation appears to be ATM-dependent; inhibition of ATM by either KU-55933 or a specific siRNA prevented USP24 accumulation after UV (Figure 1C). In contrast, inhibition of ATR by caffeine or siRNA did not noticeably affect USP24 accumulation (Figure 1C and S1D). Taken together, these data suggest that the ATM kinase-mediated phosphorylation of USP24 is involved in USP24 stabilization/up-regulation following UV irradiation. Incidentally, USP24 was identified as a potential ATM target in a large-scale proteomic analysis of protein phosphorylation (Matsuoka et al., 2007).

Figure 1. USP24, up-regulated after UV irradiation, is crucial for p53 stabilization.

(A) Western blots showing the up-regulation of USP24 by UV irradiation in HCT116 cells. Cells were mock treated (-) or treated by UV (254 nm, 20 J/m2). (B) UV irradiation does not induce USP24 transcriptionally. Total RNA was isolated from HCT116 cell mock treated (-) or 3 hr after UV treatment. Expression of ACTIN, USP24 and p21, inducible by UV and a well-known p53 target, was analyzed by RT-PCR. (C) Blocking ATM by the inhibitor KU-55933 or siRNA prevents USP24 up-regulation after UV irradiation. (D) USP24 depletion alters the basal levels of p53, but not those of Mdm2. USP24 was depleted in HCT116 cells using two siRNA constructs. Proteins indicated on the right were detected by Western blotting. (E) USP24 depletion also alters UV-induced p53 stabilization. HCT116 cells without (siCtrl) or with (siRNA1) USP24 depletion were mock treated (-) or treated by UV (254 nm, 20 J/m2). Time course samples (incubation time indicated on top of the blots) were collected for Western blotting with antibodies specific for USP24, p53 and β-actin (loading control). (F) Strong correlation between the cellular levels of USP24 and p53. Three siRNA constructs were used to deplete USP24 in HCT116 cells. Cells were UV treated as described in (A) and incubated for 3 hrs.

USP24 is crucial for p53 activation/stabilization upon DNA damage

p53 is maintained at low levels through ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. After genotoxic stress, p53 is released from Mdm2-mediated degradation and is rapidly stabilized and activated. Consequently, we asked whether USP24 was required for p53 stabilization and activation after DNA damage. The HCT116 cell line, in which p53 and its regulated cellular pathways perform normally, was used to investigate the effect of USP24 depletion on p53. We inspected the basal levels of p53 in the absence of exogenous DNA damage in USP24-depleted cells. As shown in Figure 1D, while endogenous p53 was readily detectable in HCT116 cells, p53 was barely detectable when USP24 was depleted by two independent siRNA constructs. Importantly, USP24 depletion did not affect the levels of Mdm2, the major E3 ligase targeting p53 for ubiquitination. These data show that USP24 is required for the basal levels of p53 expression. Upon UV irradiation, we found that p53 became stabilized and its levels increased rapidly (Figure 1E). However, the levels of p53 after UV irradiation decreased significantly when USP24 was depleted, suggesting that USP24 also plays a role in UV-induced p53 stabilization (Figure 1E). Of note, we tested three siRNAs targeting different positions of the USP24 transcript to deplete USP24 in HCT116 cells. While all three siRNAs led to efficient USP24 knockdown and p53 destabilization in response to UV treatment, the degree of p53 stabilization after UV irradiation was positively correlated with the remaining USP24 protein levels in the cell. For example, siRNA3 treated cells had the lowest levels of USP24 remaining and the lowest levels of p53 (Figure 1F). Combined, these results suggest that USP24 is required for p53 stabilization in human cells under both basal and UV conditions.

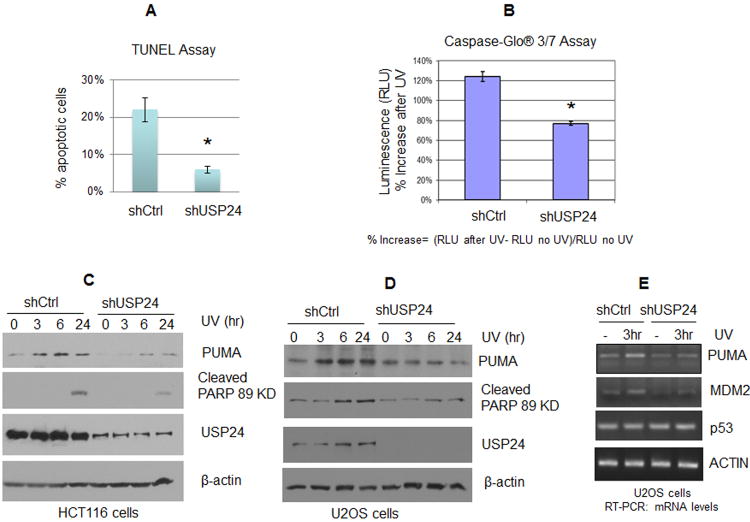

USP24 depletion inhibits apoptosis in response to UV damage

One of the most important p53 functions is to the activation of apoptosis upon DNA damage. Given that the results above suggest that USP24 is required for p53 stabilization/activation after UV damage, we therefore examined whether USP24 knockdown affects the apoptotic response to UV irradiation in HCT116 cells. We first used a TUNEL assay to detect endonucleolytic cleavage of chromatin DNA, a hallmark of apoptosis. Two stable USP24 depleted HCT116 cell lines using were created (Figure S2A). A fraction of HCT116 control cells underwent apoptosis 20 hrs after 20 J/m2 UV irradiation. In contrast, a significantly smaller amount of HCT116 cells showed such an apoptotic response when USP24 was depleted (Figure 2A and Figure S2B). These results indicate that USP24 promotes UV-induced apoptosis in HCT116 cells, consistent with the notion that p53-directed apoptosis is attenuated in USP24-depleted cells which lack robust p53 stabilization after UV treatment.

Figure 2. USP24 is required for PUMA activation and robust apoptotic response to UV irradiation.

(A) A TUNEL assay showing the effect of USP24 knockdown on UV induced apoptosis. HCT116 cells were stained using the TUNEL assay 24 hrs after mock treatment (No UV) or UV irradiation (20 J/m2). Quantitation of the TUNEL data is shown. (B) The effect of USP24 on caspase activation after UV irradiation. HCT116 cells with stable USP24 depletion and control cells were UV irradiated. After incubation for 24 hrs, all cells were collected for the analysis of caspase activation using a luminescent Caspase-Glo® 3/7 Assay. Statistical analysis was done on data from three independent experiments. The error bars represent the standard deviation of the measurements. Asterisks indicate a significant difference analyzed by an unpaired two-tailed t-test with a P-value <0.01, triplicate samples. (C, D) Depletion of USP24 led to attenuated PUMA activation and PARP cleavage in HCT116 and U2OS cells. Control cells and cells with stable USP24 depletion were UV irradiated (20 J/m2). Time course samples were collected for Western blotting. HCT116 cells (C) and U2OS cells (D) were examined. (E) UV induction of PUMA transcription is disrupted by USP24 depletion. U2OS control cells and cells with stable knockdown of USP24 expression were UV irradiated and incubated for 3 hrs. RNA was isolated, and PUMA mRNA expression was analyzed by RT-PCR.

Since caspases play a central role in the transduction of apoptotic signals (Jiang and Wang, 2004; Taylor et al., 2008), we next used a Caspase-Glo® 3/7 Assay to evaluate the effect of USP24 on caspase activation. As shown in Figure 2B, USP24 depletion led to significant inhibition of caspase activation after UV treatment. In agreement with the results obtained using the TUNEL assay, these data argue that USP24 is required for the apoptotic response to UV irradiation.

USP24 depletion inhibits PUMA activation and PARP cleavage in response to UV damage

The p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA) is a proapoptotic protein (Yu et al., 2001). Consistent with a role of USP24 in p53 stabilization and the activation of apoptosis, USP24 depletion reduced activation of PUMA considerably in HCT116 and U2OS cells, as shown at the protein levels (Figure 2C and 2D), as well as the mRNA levels (Figure 2E). Similar to PUMA, transcription of the MDM2 gene, another known p53 transcriptional target, was also induced by UV and affected by USP24 depletion (Figure 2E). However, we did not detect any significant effect of USP24 depletion on p53 transcription (Figure 2E). These data suggest that USP24 is required for UV induced apoptosis, at least in part, through regulation of p53 induction of proapoptotic genes, such as PUMA.

Since PARP is one of the main cleavage targets of activated caspase-3 in vivo, we next examined the effect of USP24 depletion on the effector caspase activation by monitoring PARP cleavage (Lazebnik et al., 1994). As expected, UV irradiation led to the production of the cleaved PARP in both U2OS and HCT116 cells (Figure 2C and 2D). However, the levels of cleaved PARP decreased considerably in USP24 depleted cells. These data suggest that USP24 is required for rapid caspase activation.

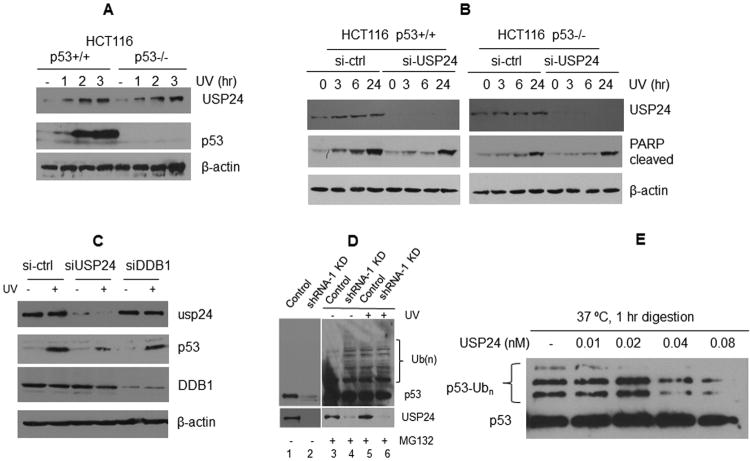

USP24 regulates the UV damage response via the p53 pathway

To examine whether USP24 regulates the apoptotic response to UV through the p53 pathway, we compared the effects of USP24 depletion on UV induced PARP cleavage in two isogenic cell lines: HCT116 p53+/+ and HCT116 p53-/-. Since p53 is a major transcription factor regulating downstream targets in the DNA damage response, it is important to note that USP24 is not a p53 target gene since USP24 up-regulation after UV exposure occurs regardless of the p53 availability (Figure 3A). In p53+/+ cells, cleaved PARP started to appear as early as three hours after UV irradiation and depletion of USP24 resulted in slow and reduced PARP cleavage (Figure 3B, right panel). By contrast, reduced levels of PARP cleavage were observed in p53-/- cells (Figure 3B, left panel). Importantly, USP24 depletion in p53-/- cells did not noticeably affect PARP cleavage (Figure 3B, left panel). Taken together, these data suggest that USP24 regulates apoptosis after UV irradiation by targeting p53.

Figure 3. Evidence that USP24 regulates UV-induced PARP cleavage through p53.

(A) Up-regulation of USP24 by UV is independent of p53. HCT116 (p53+/+) and isogenic HCT116 p53-/- cells were UV irradiated (20 J/m2). Time course samples were collected for Western blotting analysis using antibodies indicated. (B) p53 is required for USP24 to regulate PARP cleavage. HCT116 (p53+/+) and isogenic HCT116 p53-/- cells were treated with control siRNAs and USP24 siRNAs and UV irradiated (20 J/m2). Time course samples were collected for PARP analysis by Western blotting. (C) The effect of DDB1 depletion on p53 expression. Cells were depleted of either USP24 or DDB1, mocked treated (-) or treated with UV irradiation and incubated for 3 hrs. Western blotting was performed using antibodies indicated. (D) Evidence that USP24 targets ubiquitinated p53 in vivo. HCT116 cells with stable USP24 knockdown (shRNA-1 KD) and control cells were UV irradiated (20 J/m2) or mocked treated (-). Cells were then treated with 10 μM MG132 (+) or mock treated (-) and incubated for 4 hrs. Proteins indicated on the right were detected by Western blotting using p53 and USP24 antibodies. Protein ladders picked up by p53 antibodies match polyubiquitinated [Ub(n)] forms of p53. (E) USP24 cleaves ubiquitinated p53 in vitro. Ubiquitinated p53 was mixed with indicated amounts of purified USP24 for 1 hr. Reactions were stopped by the addition of SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Western blot was done using a p53 antibody.

USP24 does not affect the levels of Mdm2 and DDB1

We also analyzed the decay of p53 and Mdm2 in cells with normal or reduced levels of USP24 using a cycloheximide treatment to inhibit new protein synthesis (Figure S3A). p53 is a short-lived protein but readily detectable in cells with normal levels of USP24. However, p53 became barely detectable in USP24 depleted cells (Figure S3A). In contrast to the effect of USP24 on p53, it appears that USP24 depletion did not noticeably affect the Mdm2 stability (Figure S3A). The DDB1-Cul4A E3 ligase has also been shown to specifically target p53 for ubiquitination (Banks et al., 2006). However, under our experimental conditions, DDB1 knockdown did not lead to p53 stabilization and USP24 depletion did not affect the levels of DDB1 (Figure 3C). These results suggest that, instead of targeting p53 through DDB1 and Mdm2, USP24 may stabilize p53 by targeting p53 directly for deubiquitination.

USP24 deubiquitinates p53 in vivo and in vitro

MG132 treatment, which blocks proteasomal degradation, allowed the detection of polyubiquitinated forms of p53. In the absence of MG132 treatment, USP24 depletion reduced the steady state levels of p53 (Figure 3D, lane 1 vs 2). USP24 knockdown led to the appearance of new forms of polyubiquitinated p53 in the presence of MG132 (Figure 3D, lane 3 vs 4 and Figure S3B). Surprisingly, these polyubiquitinated forms of p53 also appeared after UV irradiation when cells were treated with MG132 (Figure 3D, lane 5), indicating that a p53 ubiquitin ligase may be stabilized and activated after combined UV and MG132 treatment. Under these conditions, USP24 knockdown did not significantly alter the banding patterns of polyubiquitinated p53 (Figure 3D, lane 5 vs 6 and Figure S3B). In addition, USP24 could be co-immunoprecipitated with p53 in vivo (Figure S3C). These findings strongly suggest that USP24 directly targets ubiquitinated p53 and removes the ubiquitin moiety, thereby preventing p53 degradation.

In order to examine the deubiquitinating activity of USP24 toward p53 in a purified system, we generated ubiquitinated forms of p53 and mixed them with highly purified USP24 protein (Figure S3D). We found that purified USP24 was able to cleave and remove the ubiquitin moiety from p53 (Figure 3E). This effect was dose-dependent, as increasing amounts of USP24 resulted in decreased amounts of ubiquitinated forms of p53. Incubation for 4 hrs also improved the release of ubiquitin from modified p53 (Figure S3E). These findings show that USP24 can deubiquitinate p53 in vitro.

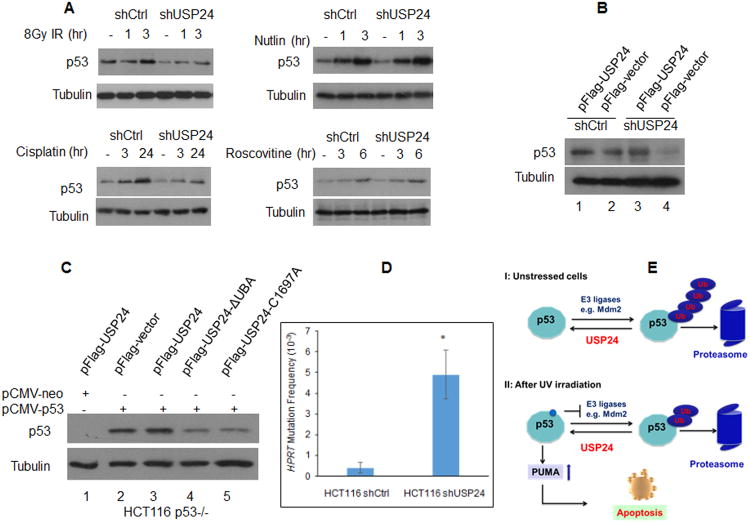

Evidence that USP24 targets p53 to protect genome stability

We found that USP24 was also required for p53 stabilization after cells were treated cell with two additional DNA damage agents, ionizing radiation (IR) and cisplatin (Figure 4A). In contrast, p53 stabilization was not noticeably affected when cells were treated with nutlin and roscovitine (Figure 4A). We note that nutlin blocks p53-Mdm2 interactions and roscovitine down-regulates MDM2 expression without affecting p53 binding to Mdm2. Presumably, treatment by nutlin and roscovitine led to p53 stabilization by blocking p53 ubiquitination, which may change the dynamics of ubiquitin cleavage by USP24 and attenuate the effect of USP24 depletion on p53 levels.

Figure 4. USP24 contributes to p53 stabilization and protects genome stability.

(A) The effect of USP24 depletion on p53 stabilization under various stress conditions. (B) Overexpression of USP24 in USP24 depleted cells re-stabilized p53. USP24 was depleted in HCT116 cells by a 3′-UTR targeting shRNA. Cells were transfected with the plasmid vector or a cDNA encoding USP24. 48 hrs after transfection, endogenous p53 was detected by Western blot. (C) Expression of wild-type USP24, not USP24 mutants, is required for p53 stabilization. Wild-type and mutant forms of USP24 were co-expressed with p53 in HCT116 p53-/- cells. 48 hrs after transfection, p53 was detected by Western blot. (D) USP24 depletion led to hypermutation at the HPRT locus. HPRT mutation frequencies for HCT116 shCtrl and shUSP24 cell lines. Data represent means ±S.D. from three triplicate plates, and ** indicates p <.002 (t test). (E) A model depicting the role of USP24 in p53 stabilization. USP24 is required for p53 stabilization under both stressed and unstressed conditions by deubiquitinating p53.

To examine if USP24 re-expression in USP24 depleted cells can stabilize p53, we created USP24 depleted cells using an shRNA construct targeting the USP24 3′-UTR and introduced a Flag-USP24 cDNA into cells by transfection. As expected, USP24 depletion destabilized p53 in HCT116 cells (Figure 4B, lane 2 vs 4). Importantly, re-expression of USP24 indeed led to p53 stabilization (Figure 4B, lane 3 vs 4). The stabilizing effect of USP24 on p53 was more apparent when p53 and USP24 were co-expressed in HCT116 p53-/- cells (Figure 4C). While wild-type USP24 stabilized p53, overexpression of a USP24 mutant without the intact ubiquitin association domain (ΔUBA) or a mutant with a crucial cysteine changed to alanine led to p53 destabilization (compare lane 4 vs 2 and lane 5 vs 2). These results establish that USP24 enzyme is required for p53 stabilization. Consistent with this notion, HCT116 cells with USP24 depletion exhibited significantly elevated mutation rates at the endogenous hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT) gene, implying an important role for USP24 in maintaining genome stability (Figure 4D).

Cellular localization of USP24

Since the cellular localizations of DUBs can provide important insight into their roles in p53 regulation, we examined the cellular localization of endogenous USP24 using immunofluorescence staining and a cell fractionation assay. It is clear that USP24 is predominantly localized in the nucleus in HCT116 cells, with a small fraction of USP24 detected in the cytoplasm (Figure S4A and S4B). We note that the pattern of USP24 distribution in the cytoplasm and nucleus appears very similar to that of p53. Importantly, UV treatment did not result in a detectable change in USP24 localization (Figure S4B).

We previously reported that USP24 interacts with DDB2 and USP24 depletion destabilizes DDB2 in 293T cells (Zhang et al., 2012). Consistent with these observations, HCT116 cells with stable USP24 depletion (Figure S4C) contained reduced levels of DDB2 (Figure S4D, - UV lanes). However, UV-induced DDB2 degradation, believed to be important for UV lesion repair in chromatin, was not affected by USP24 depletion (Figure S4D). Since DDB2 is involved in CPD lesion repair in chromatin and cells with inactive DDB2 have deficient CPD repair (Ghodke et al., 2014), we examined the effect of USP24 on the repair of CPD lesions. As shown in Figure S4E, the efficiency of CPD removal was not noticeably affected by USP24 depletion. Presumably, our inability to detect an effect of USP24 depletion on CPD repair is due to the residual levels of DDB2 in USP24 depleted cells (Figure S4D).

Discussion

In this study, we have identified USP24 as a p53 deubiquitinase. Our data show that USP24 deubiquitinates p53 in vivo and in vitro, leading to p53 stabilization and activation. Depletion of USP24 significantly attenuates p53-dependent apoptosis induced by DNA damage. In cells without p53, the effect of USP24 depletion on apoptosis is barely detectable. Importantly, USP24 depletion exhibited significantly elevated mutation rates at the HPRT locus, implying an important role for USP24 in maintaining genome stability. Our findings show that USP24 is a p53 regulator and possibly providing an alternative way to inactive p53 in cancer.

Several DUBs regulate p53 levels in the cell

p53 is a central integrator of a plethora of signals and assimilates these signals to execute its tumor suppressor function. It is well documented that ubiquitination plays a major part in p53 regulation (Lee and Gu, 2010). p53 is targeted by many ubiquitin ligases, with Mdm2 playing a major role both in controlling basal levels of p53 in normal unstressed cells, and in response to stress conditions. Other E3 ubiquitin ligases identified to date include COP1, Pirh2, ARF-BP1, MSL2 and Parc (Brooks and Gu, 2006). As stated earlier, several p53 deubiquitinating enzymes have been identified. Deubiquitinating enzymes that cleave ubiquitin chains play roles in controlling the extent of ubiquitination of p53 and its subsequent degradation. These DUBs can target p53 directly or indirectly by regulating the E3 ligase Mdm2.

Underscoring the dynamic and reversible nature of protein ubiquitination, it appears that the specificity and regulatory potential of DUBs are as complex as targeted protein ubiquitination by E3 ubiquitin ligases. Using a ubiquitin chain restriction analysis, a recent report shows that many DUBs are ubiquitin chain linkage specific (Mevissen et al., 2013). The p53-targeting E3 ligases can direct different forms of p53 ubiquitination. Several E3 ligases, including Mdm2, can mediate K48-linked polyubiquitination of p53 and target p53 for degradation. Other types of ubiquitination, including mono- or K63-linked polyubiquitinations, can lead to nuclear export and cytosolic localization. Ubiquitination can also disrupt p53 from binding to target gene recognition sequences in the nucleus, resulting in apoptosis or cell cycle arrest (Lee and Gu, 2010). We speculate that the identified p53 targeting DUBs process ubiquitinated p53 depending on p53 cellular localization and its ubiquitin chain linkage.

Deubiquitinating enzymes involved in the DNA damage response

Several DUBs have been shown to regulate the DNA damage response. For example, the stability of a DNA damage check point protein, CHK2, is regulated by USP28 (Bohgaki et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2006). USP7 targets Claspin, another damage response mediator protein, to prevent its degradation (Faustrup et al., 2009). Our study shows that USP24 co-immunoprecipitates with p53 and depletion of USP24 affects p53 stability, but not the Mdm2 stability. Unlike other p53-targeting DUBs, USP24 is a stress-induced protein. USP24 protein levels were increased after UV, IR, and cisplatin treatment (Figure 4A).

Our data indicate that USP24 regulates the stability of p53 protein under unstressed conditions as well as following DNA damage (Figure 4E). In unstressed cells, E3 ligases, such as Mdm2, constantly target p53 for ubiquitination and degradation. After UV irradiation, posttranslational medications of p53, including phosphorylation, prevent p53 ubiquitination, thereby stabilizing and up-regulating p53. Our data also suggest that USP24 regulates p53 stabilization by directly deubiquitinating p53. These data are consistent with our observation that USP24 depletion did not noticeably affect p53 stabilization after treatment with nutlin and roscovitine (Figure 4A), two chemicals that block p53 ubiquitination by targeting Mdm2. However, it is unclear why UV irradiation did not significantly change the banding patterns of p53 ubiquitination when cells were simultaneously treated with MG132 (Figure 3D and Figure S3B) since p53 ubiquitination is expected to decrease after UV irradiation. Since the DDB1-Cul4 E3 ligase has been suggested to contribute to p53 ubiquitination after UV irradiation (Banks et al., 2006), it is likely that combined treatment by MG132 and UV may stabilize/or activate a p53 E3 ligase such as the DDB1-Cul4 complex, leading to p53 ubiquitination under these conditions.

The involvement of different DUBs and E3 ligases in regulating p53 functions highlights the importance of p53 in the maintenance of genomic stability. USP10, USP7, USP24, USP29, USP2a and USP42 represent an array of DUBs that the cell can call upon to regulate and maintain p53 levels. Under different situations, these DUBs may be differentially activated to regulate p53 function. Additionally, our findings predict an alternative pathway to inactivate/or attenuate the tumor suppressor activity of p53. Indeed, a scan of the COSMIC somatic mutation database shows that USP24 is frequently mutated in various human cancers (Table S1), consistent with our findings that depletion of USP24 leads to higher mutation rates in human cells (Figure 4D and Figure S4).

Experimental Procedures

Cell culture and antibodies

HCT116, U2OS, MCF7, and 293T cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Antibodies used in the study are commercially available.

RNA interference

USP24 siRNA oligonucleotides and nonspecific siRNA control were obtained from Sigma in a purified and annealed duplex form. siRNA transfections were performed with RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. To create USP24 stable knockdown cell line using shRNA, MISSION shRNA Lentiviral Particles were used.

RNA analysis by RT-PCR

HCT116 cells were irradiated with UV or mock treated. Total RNA extraction and polymerase chain reaction with reverse transcription (RT– PCR) analysis was performed as described previously (Gong et al., 2008).

In vitro deubiquitination assay

The USP24 purified protein was purchased from Origene and its purity was examined by SDS-PAGE. The ubiquitinated p53 was generated using p53 ubiquitination kit from Boston Biochem (Cat. #: K-200B). The ubiquitinated p53 was then incubated with various amounts of USP24 in a deubiquitination buffer.

Apoptosis Assay

Three methods were used to evaluate apoptosis in this study. A TUNEL assay, PARP cleavage and a Caspase-Glo 3/7 assay kit (Promega) were used to assess UV induced apoptosis.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Up-regulation of the USP24 deubiquitinase by UV irradiation in various cell lines, related to Figure 1. Western blots showing up-regulation of USP24 by UV irradiation in U2OS (A), 293T (B) and MCF7 (C) cells. Cells were mock treated (-) or treated by UV (254 nm, 20 J/m2). Time course samples (incubation time indicated on top of the blots) were collected for Western blotting with antibodies specific for USP24 and actin (loading control). (D) siRNA-mediated ATR depletion did not noticeably affect USP24 accumulation after UV irradiation.

Figure S2. USP24 is required for robust apoptotic response to UV irradiation, related to Figure 2. (A) Stable knockdown of USP24 expression. Two shRNA constructs were used to create two stable USP24 depleted cell lines. (B) A TUNEL assay showing the effect of USP24 knockdown on UV induced apoptosis. Cells were stained using the TUNEL assay 24 hrs after mock treatment (No UV) or UV irradiation (20 J/m2).

Figure S3. The effect of USP24 depletion on the cellular levels of p53, Mdm2 and DDB1, related to Figure 3. (A) The effect of USP24 depletion on the stability of p53 and Mdm2. HCT116 cells transfected with USP24 or control siRNAs were treated with cycloheximide to inhibit protein synthesis, time course samples were collected to follow the decay of p53 and Mdm2 by Western blotting. (B) Evidence that USP24 targets ubiquitinated p53 in vivo. Left panel: USP24 knockdown alters the pattern of p53 ubiquitination in the presence of MG132. Right panel: The effect of USP24 knockdown on p53 ubiquitination after UV irradiation in the presence of MG132. HCT116 cells with stable USP24 depletion (shRNA-1 KD) and control cells were UV irradiated (20 J/m2) or mocked treated (-). Cells were then treated with 10 μM MG132 (+) immediately or mock treated (-) and incubated for 4 hrs. Proteins indicated on the right were detected by Western blotting using p53 and USP24 antibodies. Protein ladders picked up by a p53 antibody match polyubiquitinated [Ub(n)] forms of p53. (C) Co-immunoprecipitation of USP24 and p53. HCT116 cell lysates were used for immunoprecipitation using a p53 antibody. IgG was used as control. (D) Purified USP24 protein with ∼290 Kda MW. (E) USP24 cleaves ubiquitinated p53 in vitro. Ubiquitinated p53 was mixed with indicated amounts of purified USP24 and incubated for 3 hrs. Reactions were stopped by the addition of SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Western blot was done using a p53 antibody. Ubiquitinated forms of p53 are indicated.

Figure S4. USP24, localized primarily in the nucleus, plays a role in the maintenance of genomic stability, related to Figure 4. (A) Immunofluorescence staining of USP24 in the cell. HCT116 cells with or without UV treatment were stained with DAPI and an antibody against USP24. (B) Similar cellular localization of USP24 and p53. A cell fractionation assay was used to examine USP24 and p53 cellular localization. The cytoplasmic fraction (C) and nuclear fraction (N) were shown. (C) Reduced levels of DDB2 in UPS24 depleted HCT116 cells. USP24 depleted cells and control cells were UV irradiated (20 J/m2) or mocked treated (-). Time course samples were collected for Western blot analysis. (D) HCT116 cells with stable USP24 knockdown. (E) Stable USP24 depletion has no detectable effect on CPD repair. Cells were UV irradiated (20 J/m2) or mocked treated (No UV). Cells were incubated to allow repair of UV damage. Total genomic DNA was purified and slot blots were used to quantify the remaining amount of the UV-induced CPDs (cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers). (F and G) USP24 depletion led to hypermutation at the HPRT locus after UV irradiation. HCT116 shCtrl and shUSP24 cells were treated with either 25 J/m2 or 40 J/m2 UV-C irradiation. Cells were incubated for two day to recover. HPRT mutation frequencies were examined. Data represent means ±S.D. from three triplicate plates, and ** indicates p <0.05 (t test).

Table S1. USP24 is frequently mutated in human cancers*, consistent with data in Figure 4 showing that USP24 plays a role in the maintenance of genomic stability.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH R01 ES017784 and a summer undergraduate research supplement ES017784–3S1 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allende-Vega N, Sparks A, Lane DP, Saville MK. MdmX is a substrate for the deubiquitinating enzyme USP2a. Oncogene. 2010;29:432–441. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks D, Wu M, Higa LA, Gavrilova N, Quan J, Ye T, Kobayashi R, Sun H, Zhang H. L2DTL/CDT2 and PCNA interact with p53 and regulate p53 polyubiquitination and protein stability through MDM2 and CUL4A/DDB1 complexes. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1719–1729. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.15.3150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohgaki M, Hakem A, Halaby MJ, Bohgaki T, Li Q, Bissey PA, Shloush J, Kislinger T, Sanchez O, Sheng Y, et al. The E3 ligase PIRH2 polyubiquitylates CHK2 and regulates its turnover. Cell death and differentiation. 2013;20:812–822. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks CL, Gu W. p53 ubiquitination: Mdm2 and beyond. Mol Cell. 2006;21:307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins JM, Vogelstein B. HAUSP is required for p53 destabilization. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:689–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danial NN, Korsmeyer SJ. Cell death: critical control points. Cell. 2004;116:205–219. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faustrup H, Bekker-Jensen S, Bartek J, Lukas J, Mailand N. USP7 counteracts SCFbetaTrCP- but not APCCdh1-mediated proteolysis of Claspin. J Cell Biol. 2009;184:13–19. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200807137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghodke H, Wang H, Hsieh CL, Woldemeskel S, Watkins SC, Rapic-Otrin V, Van Houten B. Single-molecule analysis reveals human UV-damaged DNA-binding protein (UV-DDB) dimerizes on DNA via multiple kinetic intermediates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E1862–1871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323856111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong F, Fahy D, Liu H, Wang W, Smerdon MJ. Role of the mammalian SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex in the cellular response to UV damage. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:1067–1074. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.8.5647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haupt Y, Maya R, Kazaz A, Oren M. Mdm2 promotes the rapid degradation of p53. Nature. 1997;387:296–299. doi: 10.1038/387296a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hock AK, Vigneron AM, Carter S, Ludwig RL, Vousden KH. Regulation of p53 stability and function by the deubiquitinating enzyme USP42. EMBO J. 2011;30:4921–4930. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda R, Tanaka H, Yasuda H. Oncoprotein MDM2 is a ubiquitin ligase E3 for tumor suppressor p53. FEBS letters. 1997;420:25–27. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffers JR, Parganas E, Lee Y, Yang C, Wang J, Brennan J, MacLean KH, Han J, Chittenden T, Ihle JN, et al. Puma is an essential mediator of p53-dependent and -independent apoptotic pathways. Cancer cell. 2003;4:321–328. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00244-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Wang X. Cytochrome C-mediated apoptosis. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:87–106. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Tu HC, Ren D, Takeuchi O, Jeffers JR, Zambetti GP, Hsieh JJ, Cheng EH. Stepwise activation of BAX and BAK by tBID, BIM, and PUMA initiates mitochondrial apoptosis. Molecular cell. 2009;36:487–499. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komander D, Clague MJ, Urbe S. Breaking the chains: structure and function of the deubiquitinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:550–563. doi: 10.1038/nrm2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubbutat MH, Jones SN, Vousden KH. Regulation of p53 stability by Mdm2. Nature. 1997;387:299–303. doi: 10.1038/387299a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane D, Levine A. p53 Research: the past thirty years and the next thirty years. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a000893. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazebnik YA, Kaufmann SH, Desnoyers S, Poirier GG, Earnshaw WC. Cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase by a proteinase with properties like ICE. Nature. 1994;371:346–347. doi: 10.1038/371346a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JT, Gu W. The multiple levels of regulation by p53 ubiquitination. Cell death and differentiation. 2010;17:86–92. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Brooks CL, Kon N, Gu W. A dynamic role of HAUSP in the p53-Mdm2 pathway. Mol Cell. 2004;13:879–886. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00157-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marine JC, Lozano G. Mdm2-mediated ubiquitylation: p53 and beyond. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:93–102. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka S, Ballif BA, Smogorzewska A, McDonald ER, 3rd, Hurov KE, Luo J, Bakalarski CE, Zhao Z, Solimini N, Lerenthal Y, et al. ATM and ATR substrate analysis reveals extensive protein networks responsive to DNA damage. Science. 2007;316:1160–1166. doi: 10.1126/science.1140321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mevissen TE, Hospenthal MK, Geurink PP, Elliott PR, Akutsu M, Arnaudo N, Ekkebus R, Kulathu Y, Wauer T, El Oualid F, et al. OTU deubiquitinases reveal mechanisms of linkage specificity and enable ubiquitin chain restriction analysis. Cell. 2013;154:169–184. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller PA, Vousden KH. p53 mutations in cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:2–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Turcu FE, Ventii KH, Wilkinson KD. Regulation and cellular roles of ubiquitin-specific deubiquitinating enzymes. Annual review of biochemistry. 2009;78:363–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.082307.091526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson LF, Sparks A, Allende-Vega N, Xirodimas DP, Lane DP, Saville MK. The deubiquitinating enzyme USP2a regulates the p53 pathway by targeting Mdm2. EMBO J. 2007;26:976–986. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RC, Cullen SP, Martin SJ. Apoptosis: controlled demolition at the cellular level. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:231–241. doi: 10.1038/nrm2312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelstein B, Lane D, Levine AJ. Surfing the p53 network. Nature. 2000;408:307–310. doi: 10.1038/35042675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade M, Li YC, Wahl GM. MDM2, MDMX and p53 in oncogenesis and cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:83–96. doi: 10.1038/nrc3430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Zhang L, Hwang PM, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. PUMA induces the rapid apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells. Mol Cell. 2001;7:673–682. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J, Luo K, Zhang L, Cheville JC, Lou Z. USP10 regulates p53 localization and stability by deubiquitinating p53. Cell. 2010;140:384–396. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Zaugg K, Mak TW, Elledge SJ. A role for the deubiquitinating enzyme USP28 in control of the DNA-damage response. Cell. 2006;126:529–542. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Lubin A, Chen H, Sun Z, Gong F. The deubiquitinating protein USP24 interacts with DDB2 and regulates DDB2 stability. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:4378–4384. doi: 10.4161/cc.22688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Up-regulation of the USP24 deubiquitinase by UV irradiation in various cell lines, related to Figure 1. Western blots showing up-regulation of USP24 by UV irradiation in U2OS (A), 293T (B) and MCF7 (C) cells. Cells were mock treated (-) or treated by UV (254 nm, 20 J/m2). Time course samples (incubation time indicated on top of the blots) were collected for Western blotting with antibodies specific for USP24 and actin (loading control). (D) siRNA-mediated ATR depletion did not noticeably affect USP24 accumulation after UV irradiation.

Figure S2. USP24 is required for robust apoptotic response to UV irradiation, related to Figure 2. (A) Stable knockdown of USP24 expression. Two shRNA constructs were used to create two stable USP24 depleted cell lines. (B) A TUNEL assay showing the effect of USP24 knockdown on UV induced apoptosis. Cells were stained using the TUNEL assay 24 hrs after mock treatment (No UV) or UV irradiation (20 J/m2).

Figure S3. The effect of USP24 depletion on the cellular levels of p53, Mdm2 and DDB1, related to Figure 3. (A) The effect of USP24 depletion on the stability of p53 and Mdm2. HCT116 cells transfected with USP24 or control siRNAs were treated with cycloheximide to inhibit protein synthesis, time course samples were collected to follow the decay of p53 and Mdm2 by Western blotting. (B) Evidence that USP24 targets ubiquitinated p53 in vivo. Left panel: USP24 knockdown alters the pattern of p53 ubiquitination in the presence of MG132. Right panel: The effect of USP24 knockdown on p53 ubiquitination after UV irradiation in the presence of MG132. HCT116 cells with stable USP24 depletion (shRNA-1 KD) and control cells were UV irradiated (20 J/m2) or mocked treated (-). Cells were then treated with 10 μM MG132 (+) immediately or mock treated (-) and incubated for 4 hrs. Proteins indicated on the right were detected by Western blotting using p53 and USP24 antibodies. Protein ladders picked up by a p53 antibody match polyubiquitinated [Ub(n)] forms of p53. (C) Co-immunoprecipitation of USP24 and p53. HCT116 cell lysates were used for immunoprecipitation using a p53 antibody. IgG was used as control. (D) Purified USP24 protein with ∼290 Kda MW. (E) USP24 cleaves ubiquitinated p53 in vitro. Ubiquitinated p53 was mixed with indicated amounts of purified USP24 and incubated for 3 hrs. Reactions were stopped by the addition of SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Western blot was done using a p53 antibody. Ubiquitinated forms of p53 are indicated.

Figure S4. USP24, localized primarily in the nucleus, plays a role in the maintenance of genomic stability, related to Figure 4. (A) Immunofluorescence staining of USP24 in the cell. HCT116 cells with or without UV treatment were stained with DAPI and an antibody against USP24. (B) Similar cellular localization of USP24 and p53. A cell fractionation assay was used to examine USP24 and p53 cellular localization. The cytoplasmic fraction (C) and nuclear fraction (N) were shown. (C) Reduced levels of DDB2 in UPS24 depleted HCT116 cells. USP24 depleted cells and control cells were UV irradiated (20 J/m2) or mocked treated (-). Time course samples were collected for Western blot analysis. (D) HCT116 cells with stable USP24 knockdown. (E) Stable USP24 depletion has no detectable effect on CPD repair. Cells were UV irradiated (20 J/m2) or mocked treated (No UV). Cells were incubated to allow repair of UV damage. Total genomic DNA was purified and slot blots were used to quantify the remaining amount of the UV-induced CPDs (cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers). (F and G) USP24 depletion led to hypermutation at the HPRT locus after UV irradiation. HCT116 shCtrl and shUSP24 cells were treated with either 25 J/m2 or 40 J/m2 UV-C irradiation. Cells were incubated for two day to recover. HPRT mutation frequencies were examined. Data represent means ±S.D. from three triplicate plates, and ** indicates p <0.05 (t test).

Table S1. USP24 is frequently mutated in human cancers*, consistent with data in Figure 4 showing that USP24 plays a role in the maintenance of genomic stability.