Abstract

Angiotensin II activates cPLA2α and releases arachidonic acid from tissue phospholipids which mediate or modulate one or more cardiovascular effects of angiotensin II and has been implicated in hypertension. Since arachidonic acid release is the rate limiting step in eicosanoid production, cPLA2α might play a central role in the development of angiotensin II-induced hypertension. To test this hypothesis, we investigated the effect of angiotensin II infusion for 13 days by micro-osmotic pumps on systolic blood pressure and associated pathogenesis in wild type (cPLA2α+/+) and cPLA2α−/− mice. Angiotensin II-induced increase in systolic blood pressure in cPLA2α+/+ mice was abolished in cPLA2α−/− mice; increased systolic blood pressure was also abolished by the arachidonic acid metabolism inhibitor, 5,8,11,14-eicosatetraynoic acid in cPLA2α+/+ mice. Angiotensin II in cPLA2α+/+ mice increased cardiac cPLA2 activity and urinary eicosanoid excretion, decreased cardiac output, caused cardiovascular remodeling with endothelial dysfunction and increased vascular reactivity in cPLA2α+/+ mice; these changes were diminished in cPLA2α−/− mice. Angiotensin II also increased cardiac infiltration of F4/80+ macrophages and CD3+ T lymphocytes, cardiovascular oxidative stress, expression of endoplasmic reticulum stress markers p58IPK and CHOP in cPLA2α+/+ but not cPLA2α−/− mice. Angiotensin II increased cardiac activity of ERK1/2 and cSrc in cPLA2α+/+ but not cPLA2α−/− mice. These data suggest that angiotensin II-induced hypertension and associated cardiovascular pathophysiological changes are mediated by cPLA2α activation, most likely through the release of arachidonic acid and generation of eicosanoids with predominant pro-hypertensive effects and activation of one or more signaling molecules including ERK1/2 and cSrc.

Keywords: angiotensin II, cytosolic phospholipase A2α (cPLA2α), mice, cardiovascular function, fibrosis and hypertrophy, oxidative stress, inflammation

Introduction

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) is a major component of the mechanisms that regulate cardiovascular and renal homeostasis, and an increase in its activity leads to the development of hypertension.1 Angiotensin II (Ang II), the major bioactive peptide of the RAS, activates phospholipase A2α (PLA2α) and releases arachidonic acid (AA) from tissue phospholipids.2 AA is metabolized by cyclooxygenase (COX) into thromboxane A2 and prostaglandins (PG) E2, F2α, D2, and I2.3 Lipoxygenase (LO) converts AA into leukotrienes and 5-,12- and 15-hydroxyeicosatrienoic acids (HETEs).4 AA is also metabolized by CYP4A via its ω-hydroxylase activity into 20-HETE, and via its epoxygenase activity into epoxyeicosatrienoic acids.5,6 These eicosanoids exert pro- or anti-hypertensive effects. PGE2 via activation of EP2 and EP4 receptors,7,8 PGI2,3 and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids,5,6,9,10 contribute to anti-hypertensive mechanisms whereas PGE2 via activation of EP1 and EP3 receptors,8 and thromboxane A2,3 12- and 20-HETE6,10,11 by their vascular effects, contribute to pro-hypertensive mechanisms. AA metabolism has also been linked to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)10 that have in turn been implicated in the development of hypertension.11 The balance between pro- and anti-hypertensive eicosanoids, together with direct effects of various neurohumoral agents on the cardiovascular and renal systems, determines the level of blood pressure (BP). Whether AA metabolites generated via different pathways, following their release by activation of PLA2 by Ang II, contribute primarily to pro- or anti-hypertensive mechanisms, is not known.

At least 16 groups of mammalian PLA2 enzymes hydrolyze phospholipids to release fatty acids.12 However, cPLA2 selectively hydrolyzes AA containing phospholipids.12 cPLA2α has been implicated in a number of physiological and pathophysiological conditions13 including allergy,14 asthma,15 brain ischemia injury,16 collagen-induced arthritis17,18 and myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury19. Several BP regulating hormones, including Ang II, activate cPLA2 and release AA.20–23 Therefore the possibility arises that cPLA2α, which is highly selective in releasing AA, might function as the major center of convergence for the transduction of hormone signaling to eicosanoid production and regulation of BP.

PLA2 activity is increased in the renal medulla and cortex of stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats24 and a recent study showed the involvement of cPLA2α in L-NG-nitroarginine methyl ester, an inhibitor of NO synthesis-induced hypertension.25 However, the contribution of cPLA2α to other forms of hypertension and more importantly its significance in cardiovascular remodeling and dysfunction, oxidative stress, and inflammation in Ang II-induced hypertension and the underlying mechanism, is not known and is the major objective of this study. These results show that cPLA2α is crucial for the development of Ang II-induced hypertension and associated cardiovascular dysfunction, oxidative stress, inflammation and remodeling, most likely due to the effect of predominantly pro-hypertensive eicosanoids generated from AA released by this lipase.

Methods

The detailed experimental methods are described in the online-only Data Supplement at http://hyper.ahajournals.org.

Results

cPLA2α contributes to the development of Ang II-induced hypertension and activation of cardiac cPLA2 in mice

Ang II infusion over a period of 13 days, produced a consistent and reproducible increase in systolic BP (SBP), measured by the tail cuff (Figure 1A). Systolic (Figure 1B), diastolic (Figure 1C), and mean arterial BP (Figure 1D) measured by radio telemetry (Figure S1: tracing from all experiments), in cPLA2α+/+ but not cPLA2α−/− mice. Basal BP was not different between these two phenotypes. Tracings of the BP measured by radio telemetry for each individual cPLA2α+/+ and cPLA2α−/− mouse during Ang II infusion is shown in Figure S1–A1 and A-2. Heart rate during Ang II infusion as measured by radio telemetry was not altered in cPLA2α+/+ or cPLA2α−/− mice (Figure S1B). Power spectral analysis of BP and heart rate variability showed an increase in the ratio of low frequency: high frequency heart rate variability during Ang II infusion in cPLA2α+/+ mice indicating increased sympathetic outflow. This ratio was decreased in cPLA2α−/− mice (Figure S1C). Ang II also resulted in increased cPLA2 activity measured by its phosphorylation, but not its protein expression, in cardiac tissue of Ang II infused cPLA2α+/+ mice; the expression of cPLA2 protein was absent in cPLA2α−/− mice (Figure S1D).

Figure 1. cPLA2α contributes to the development of Ang II-induced hypertension in mice.

cPLA2α +/+ and cPLA2α −/− mice were infused with either Ang II (700 ng/kg/min) or its vehicle (0.9% saline) with micro-osmotic pumps for 13 days, and SBP was measured by tail cuff (A) and radio telemetry (B). Diastolic (C) and mean arterial pressure (D) were also measured by telemetry *P< 0.05 cPLA2α+/+ vehicle vs. cPLA2α+/+Ang II, #P< 0.05 cPLA2α+/+Ang II vs. cPLA2α−/−Ang II (n = 4–6 for all experiments, and data are expressed as mean ± SEM, data was analyzed by RM two-way analysis of variance followed by Turkey’s multiple comparison tests)

Arachidonic acid metabolism mediates Ang II induced hypertension in cPLA2α+/+ mice

To elucidate the mechanism by which Ang II mediates hypertension in WT mice, another group of cPLA2α+/+ mice were infused with Ang II and concurrently injected with an inhibitor of AA metabolism, 5,8,11,14 eicosatetraynoic acid (ETYA), at a dose of 50 mg/kg, i.p. every third day. ETYA prevented Ang II induced increase in SBP in cPLA2α+/+ mice (Figure S2)

Ang II infusion resulted in a significant increase in excretion of PGE2 metabolites (PGEM: 13,14-dihydro-15-keto PGA2, 13,14-dihydro-15-keto PGE2) (Figure 2A), TXB2 (Figure 2B) and 20-HETE (Figure 2C), in cPLA2α+/+ but not cPLA2α−/− mice.

Figure 2. Increased arachidonic acid metabolism to pro-hypertensive eicosanoids mediates Ang II induced hypertension in cPLA2α+/+ mice.

Increase urinary excretion of PGE2 metabolites (A) TXB2 (B) and 20-HETE (C) was observed in cPLA2α +/+ but not in cPLA2α −/− mice infused with Ang II. *P< 0.05 cPLA2α+/+ vehicle vs. cPLA2α+/+Ang II, #P< 0.05 cPLA2α+/+Ang II vs. cPLA2α−/−Ang II, ϕ P< 0.05 cPLA2α+/+ vehicle vs. cPLA2α−/−vehicle (n = 4–6 for all experiments, and data are expressed as mean ± SEM)

cPLA2α gene disruption abolishes expression of cPLA2α but does not affect related phospholipases

The possibility arises that disrupting cPLA2α may alter the expression of other related phospholipases. Thus we performed q-RT PCR analysis for various phospholipases. mRNA expression of cPLA2α, but not other related enzymes, was absent in cardiac tissue of cPLA2α−/− mice (Figure S3A). Cardiac protein expression of phospholipase Cβ2, D1, D2 was neither affected by cPLA2α disruption or Ang II infusion in either of the treatment groups (Figure S3B)

cPLA2α gene disruption does not alter expression of Ang II type 1 and 2, Mas receptor, and angiotensin converting enzyme

To determine if decreased BP during Ang II-infusion in cPLA2α−/− mice results from alterations in expression of Ang II type 1 (AT1) and 2 (AT2), Ang (1–7) Mas receptor, or angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), we measured cardiac expression of these receptors and ACE. Expression of AT1, AT2, Mas receptor, and ACE were not altered in cardiac tissue of cPLA2α−/− mice (Figure S3C).

cPLA2α gene disruption prevents cardiac dysfunction and fibrosis associated with Ang II-induced hypertension in mice

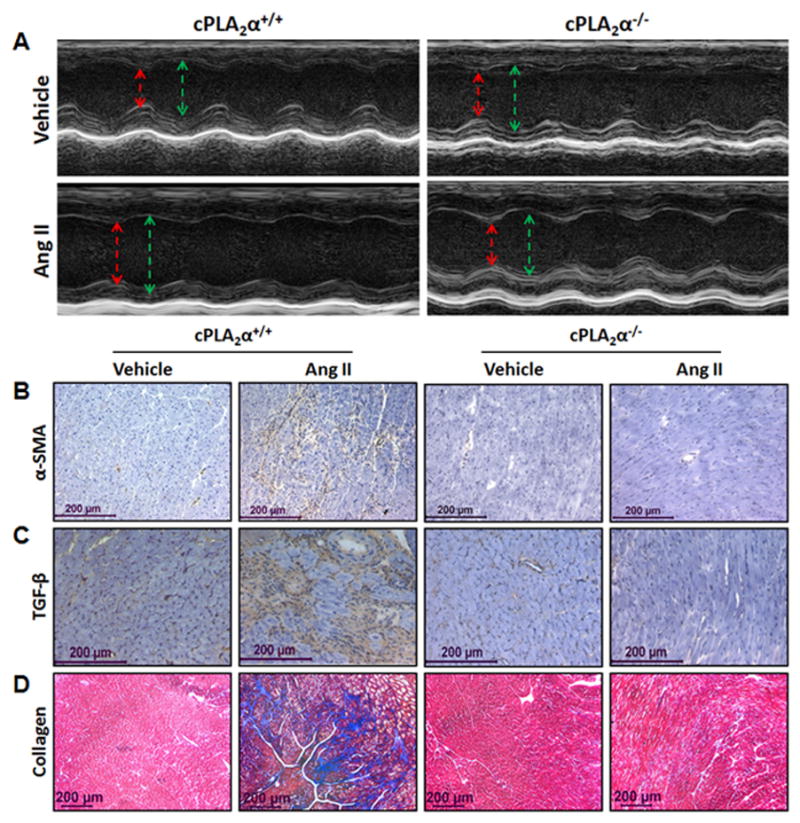

Cardiac functional and structural changes were measured by echocardiography on the 12th day of infusion of Ang II or its vehicle. M-mode images of the LV (Left Ventricle)in the parasternal long-axis view showed dilated cardiomyopathy as indicated by LV chamber enlargement and impaired contractility in Ang II-infused cPLA2α+/+ but not cPLA2α−/− mice (Figure 3A). Various parameters (Table 1), revealed cardiac dysfunction including an increase in LV mass in Ang II-infused cPLA2α+/+ but not cPLA2α−/− mice. Heart sections of Ang II-infused cPLA2α+/+ but not cPLA2α−/− mice showed fibrosis as indicated by positive staining of intracardiac α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (Figure 3B), transforming growth factor (TGF)-β (Figure 3C), and collagen (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. cPLA2α gene disruption attenuates cardiac dysfunction, hypertrophy and fibrosis associated with Ang II-induced hypertension in mice.

Echocardiograms of the left ventricle in M mode, parasternal long-axis view (A), demonstrates increase in LVID in both systole (red) and diastole (green) suggesting dilated cardiomyopathy characterized by enlarged LV mass in Ang II-infused cPLA2α+/+ but not cPLA2α−/− mice. Various parameters of cardiac function were also measured (Table 1). Increased interstitial staining of α-SMA (B) and TGF-β (C) indicators of interstitial fibrosis and collagen accumulation (D) (intense blue staining) was observed in Ang II-infused cPLA2α+/+ but not cPLA2α−/− mice. (n=4–6 for each group; data are expressed as mean ± SEM)

Table 1.

Parameters of Cardiac Function

| cPLA2α+/+ | cPLA2α−/− | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Parameters | Vehicle | Ang II | Vehicle | Ang II |

| EF% | 63.94 ± 1.0 | 40.66 ± 3.2* | 63.47 ± 2.4 | 63.97 ± 1.3# |

| FS% | 34.19 ± 0.8 | 19.39 ± 1.9* | 33.77 ± 1.7 | 34.17 ± 0.9# |

| SV | 39.78 ± 1.2 | 23.48 ± 1.6* | 37.33 ± 2.8 | 36.60 ± 2.5# |

| CO | 16.35 ± 0.6 | 11.80 ± 1.1* | 15.11 ± 0.7 | 16.84 ± 2.5# |

| LV mass | 83.07 ± 7.3 | 146.66 ± 6.2* | 92.90 ± 2.9 | 107.56 ± 7.8*# |

| LVID-d | 3.61 ± 0.2 | 4.31 ± 0.05* | 3.60 ± 0.2 | 3.66 ± 0.1# |

| LVID-s | 2.33 ± 0.1 | 3.63 ± 0.1* | 2.33 ± 0.2 | 2.37 ± 0.1# |

| LVAW-s | 1.24 ± 0.1 | 1.44 ± 0.2 | 1.31 ± 0.1 | 1.55 ± 0.1 |

| LVAW-d | 1.10 ± 0.1 | 1.36 ± 0.1 | 0.97 ± 0.1 | 1.07 ± 0.1 |

| LVPW-s | 0.95 ± 0.1 | 1.15 ± 0.01 | 1.22 ± 0.2 | 1.56 ± 0.1 |

| LVPW-d | 0.68 ± 0.03 | 1.05 ± 0.04 | 0.85 ± 0.1 | 0.91 ± 0.04 |

| EDV | 62.36 ± 1.8 | 75.78 ± 1.9* | 57.63 ± 4.7 | 58.59 ± 4.3# |

| ESV | 21.39 ± 0.7 | 53.50 ± 3.5* | 22.38 ± 2.9 | 21.97 ± 2.5# |

| IVS-s | 1.48 ± 0.02 | 1.44 ± 0.01 | 1.21 ± 0.1 | 1.65 ± 0.1 |

| IVS-d | 0.98 ± 0.04 | 1.06 ± 0.02 | 0.86 ± 0.1 | 1.05 ± 0.1 |

EF, ejection fraction; FS, fractional shortening; SV, stroke volume (ul); CO, cardiac output (ml/min); LV mass, left ventricular mass (mgs); LVID, LV internal dimension (mm); LVAW, LV anterior wall (mm); LVPW, LV posterior wall (mm); EDV, end diastolic volume (ul); ESV, End systolic volume; IVS, Intraventricular septum (mm). s, d indicate systole or diastole. The parameters listed in the table were measured using M-mode and B-mode images in the short and parasternal long-axis views as described in the methods.

P< 0.05 cPLA2α+/+ vehicle vs. cPLA2α+/+Ang II,

P< 0.05 cPLA2α+/+Ang II vs. cPLA2α−/−Ang II (n=4–6 for each group; data are expressed as mean ± SEM).

cPLA2α gene disruption prevents cardiac inflammation

To determine the contribution of cPLA2α to inflammation associated with Ang II-induced hypertension, we examined the localization of F4/80+ macrophages, and CD3+ T-lymphocytes in cardiac tissue of cPLA2α +/+ and cPLA2α−/− mice. Ang II caused infiltration of F4/80+ macrophages (Figure S4A) and CD3+ T cells (Figure S4B) in the hearts of cPLA2α+/+ but not cPLA2α−/− mice.

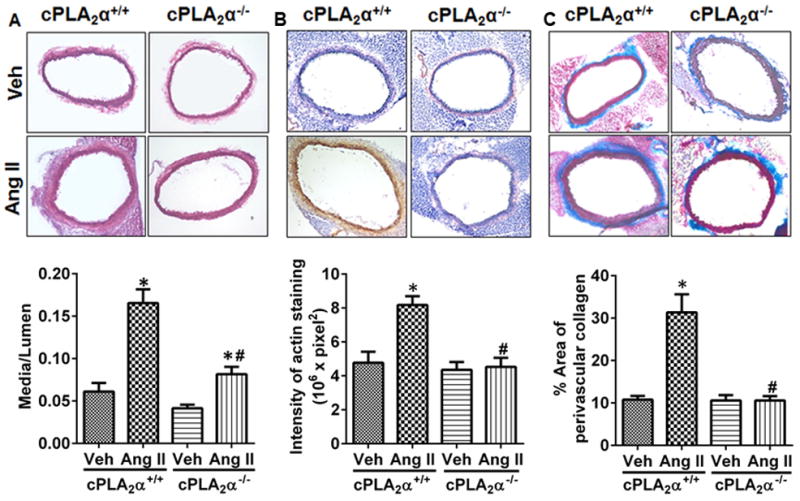

cPLA2α gene disruption protects against Ang II-induced vascular remodeling

To assess the effect of cPLA2α gene disruption on vascular remodeling associated with Ang II-induced hypertension, aortas were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and media:lumen ratio was calculated. The aortas were also stained for α-SMA and collagen. Ang II increased media:lumen ratio (Figure 4A), α-SMA (Figure 4B) positive stained cells and collagen accumulation (Figure 4C) in aortas of cPLA2α+/+ mice compared to cPLA2α−/− mice.

Figure 4. cPLA2α gene disruption protects against Ang II-induced vascular remodeling.

Sections of aortas were stained and quantified for media:lumen ratio (A) α-smooth muscle actin (B), and collagen accumulation (C). *P< 0.05 vehicle vs. Ang II, #P< 0.05 cPLA2α+/+Ang II vs. cPLA2α−/−Ang II. (n=3–5 for each group; data are expressed as mean ± SEM)

cPLA2α gene disruption prevents increased vascular reactivity and endothelial dysfunction in Ang II-induced hypertension

Ang II-induced hypertension was associated with increased response of aortas to phenylephrine (PE) (Figure S5A) and endothelin-1 (ET-1) (Figure S5B) in cPLA2α+/+ mice; these increases were abrogated in cPLA2α−/− mice. Ang II-infusion caused endothelial dysfunction, as indicated by diminished dilation to acetylcholine (ACh) in aortas preconstricted with PE in cPLA2α+/+ but not cPLA2α−/− mice (Figure S5C). Endothelial-independent relaxation of aorta to sodium nitroprusside (SNP) was not altered (Figure S5D).

cPLA2α gene disruption protects against Ang II-induced cardiovascular oxidative stress

Oxidative stress has been implicated in various models of hypertension including Ang-II11,26, and Ang II-induced activation of cardiac nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase depends on PLA2 activity in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) in vitro. Therefore, we investigated whether cPLA2 gene disruption prevents Ang II-induced oxidative stress in heart and aorta. NADPH oxidase activity, measured by lucigenin-based luminescence assay, was increased in the hearts of Ang II-infused cPLA2α+/+ but not cPLA2α−/− mice (Figure S6A). Infusion of Ang II increased cardiac (Figure S6B,C) and aortic (Figure S6D,E) ROS production in cPLA2α+/+ but not in cPLA2α−/− mice measured by fluorescence of 2-hydroxyethidium generated after exposure of cardiac tissue and aorta to dihydroethidium.

cPLA2α gene disruption prevents endoplasmic reticulum stress in Ang II-induced hypertension

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress has been implicated in Ang II-induced hypertension.27 To determine if Ang II-infusion promotes ER stress in the heart and if it is dependent on cPLA2α, we measured mRNA expression of ER stress biomarkers p58IPK, GRP78, XBP and CHOP (GADD153). Ang II infusion increased cardiac mRNA expression of p58IPK that is induced in the early adaptive phase of the unfolded protein response, and CHOP (GADD153), a chronic ER stress marker28 in cPLA2α+/+ but not in cPLA2α−/− mice (Figure S7).

cPLA2α gene disruption prevents Ang II-induced phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase and cSrc

It is well established that, in VSMC, Ang II increases the production of ROS, and activity of one or more signaling molecules including extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK1/2) and cSrc that contributes to hypertrophy.29 ERK1/2 also promotes phosphorylation of cPLA2.30 Ang II-infusion increased ERK1/2 (Figure S8A) and cSrc (Figure S8B) activity as measured by phosphorylation of these kinases in the heart tissue of cPLA2α+/+ but not in cPLA2α−/− mice.

Discussion

The novel finding of this study is the demonstration that cPLA2α is crucial for the development of Ang II-induced hypertension and associated cardiovascular dysfunction and hypertrophy, cardiac fibrosis, inflammation, oxidative stress, and activation of ERK1/2 and cSrc in mice. This conclusion is based on our finding that infusion of Ang II increased SBP, measured by tail cuff as well as radio telemetry, in cPLA2α+/+ mice that was minimized by cPLA2α gene disruption. The selectivity of this effect of cPLA2α gene disruption in our mice was indicated by loss of cardiac expression of its mRNA but not that of other related Phospholipase enzymes. The protein expression of PLA2 but not PLCβ2, PLD1, or PLD2 was also absent in cPLA2α−/− mice. Since cPLA2α selectively catalyzes release of AA from tissue lipids12 and Ang II is known to activate cPLA2 to release AA, cPLA2 appears to mediate the hypertensive effect of Ang II via AA release. Supporting this view was our finding that cPLA2 activity, as indicated by its phosphorylation, was increased in the heart of cPLA2α+/+ but not cPLA2α−/− mice. The induction of eicosanoid production by lipopolysaccharide and calcium ionophore A23187 in peritoneal macrophages and furosemide-induced PGE2 excretion was also abolished in cPLA2α−/− mice.16,31,32. In the present study, Ang II infusion increased the urinary output of PGEM, TXB2, 20-HETEs in cPLA2α+/+ but not cPLA2α−/− mice. Moreover, administration of inhibitor of AA metabolism, ETYA, blocked Ang II-induced increase in SBP in cPLA2α+/+ mice. Therefore, it appears that metabolites of AA with pro-hypertensive effects contribute to the development of hypertension caused by Ang II in these mice. Since cPLA2α gene disruption or ETYA did not alter basal BP, it appears that cPLA2α activation and release of AA and its metabolites are not required to maintain basal BP.

The increase in BP produced by Ang II in cPLA2α+/+ mice that was associated with cardiac dysfunction as indicated by decreased ejection fraction, fractional shortening, cardiac output and increased end diastolic volume and end systolic volume, cardiac hypertrophy as shown by increased LV mass, were minimized in cPLA2α−/− mice, suggesting an essential role of cPLA2α+/+ in cardiac dysfunction and hypertrophy. Moreover, in the present study, cardiac fibrosis and inflammation as indicated by increased intracardiac staining of α-SMA myofibroblasts, TGF-β, as well as by increased infiltration of F4/80+ and CD3+ cells in Ang II-infused cPLA2α+/+ mice were prevented in cPLA2α−/− mice. These findings suggest that AA metabolites with pro-hypertensive effects also mediate cardiac fibrosis and inflammation associated with Ang II-induced hypertension. cPLA2α was also found to be critical for increased vascular remodeling and reactivity associated with Ang II-induced hypertension characterized by an increase in various parameters such as media:lumen ratio, α-SMA, deposition of collagen, as well as by increased contractile response of aorta to PE and ET-1 in cPLA2α+/+ but not cPLA2α−/− mice. Although the effect of Ang II on cardiovascular remodeling has been shown to be independent of an increase in BP,33–36 we cannot exclude the possibility that the protection against Ang II-induced cardiovascular remodeling in cPLA2α−/− mice could also be due to decreased BP. The precise mechanism by which increase in BP causes cardiovascular remodeling is not known. Since stretch can increase cPLA2 activity and eicosanoid production,37 it raises the possibility that the increased stretch associated with hypertension might also result in cPLA2α activation and generation of eicosanoids that contribute to Ang II-induced cardiovascular remodeling. Ang II-induced hypertension is also known to be associated with endothelial dysfunction.26 Our finding that Ang II-induced endothelial dysfunction, as indicated by diminished relaxation of aorta to ACh but not to SNP, an agent that acts directly on VSMCs, occurs selectively in cPLA2α+/+ but not cPLA2α−/− mice, suggests that cPLA2α is essential for endothelial dysfunction associated with Ang II-induced hypertension. Moreover, endothelial dysfunction in larger vessels is dependent on NO.38 Hypertension caused by the inhibitor of NO synthesis, L-NG-nitroarginine methyl ester (LNAME), which has been attributed to increased activity of RAS and sympathetic nervous systems,39,40 is also associated with endothelial dysfunction in the aorta. Both hypertension and endothelial dysfunction are prevented in cPLA2α−/− mice.25

The mechanism by which cPLA2α gene disruption protects against Ang II-induced hypertension and cardiovascular remodeling, inflammation, increased vascular reactivity, and endothelial dysfunction could be due to alterations in expression of Ang II, Ang (1–7) receptors, and ACE enzyme. However, this possibility appears to be unlikely because the expression levels of AT1, AT2, Mas receptor and ACE enzyme examined in the heart were not different in cPLA2α−/− compared to cPLA2α+/+ mice. Oxidative stress and activation of immune system have been implicated in various models of hypertension including Ang II-induced hypertension.41,42 In the present study, Ang II-induced hypertension was associated with increased oxidative stress, as shown by increased cardiac NADPH oxidase activity and ROS production in the heart and aorta, and cardiac infiltration of F4/80+ macrophages and CD3+ T lymphocytes in cPLA2α+/+ mice. These changes were prevented in cPLA2α−/− mice, suggesting that increased oxidative stress and inflammation in Ang II-induced hypertension are dependent on cPLA2α. Supporting this view, it has been shown that Ang II increases NADPH oxidase activity by activating cPLA2 and release of AA in VSMCs.43,44 cPLA2α generated AA has also been implicated in NADPH oxidase activation in human monocytes and myeloid cell line PLB-985.45,46 AA metabolites generated by COX, PGE2 via its actions on EP1 and EP3 receptors47,48 and TXA249 contributes to Ang II-induced hypertension. AA metabolites formed by 12/15 lipoxygenase9,50 and by CYP450 4A (20-HETE),51,52 also contribute to Ang II-induced hypertension. Therefore, protection against Ang II-induced hypertension and associated cardiovascular pathogenesis in cPLA2α−/− mice is most likely due to lack of AA release and generation of one or more metabolites that mediate hypertensive effects of Ang II. Supporting this conclusion was our finding that Ang II infusion increased the urinary excretion of PGEM, TXB2, 20-HETE in cPLA2α+/+ but not cPLA2α−/− mice.

The site of pro-hypertensive eicosanoids generated by cPLA2α that participate in Ang II-induced hypertension is not known. Since cPLA2α is ubiquitously distributed in various tissues and eicosanoids generated from AA act locally, it is possible that eicosanoids generated at the site of action of Ang II including the cardiovascular, renal, brain and immune cells, could contribute to Ang II-induced hypertension. Recently, it has been shown that Ang II by stimulating expression of (pro)renin receptor in the rat renal medulla through COX2-generated PGE2, via stimulation of EP4 receptors increases renin release that partly contributes to Ang II-induced hypertension.53 Also mice lacking macrophage 12/15 LO have been shown to be resistant to L-NAME or deoxycorticosterone-salt induced hypertension.54 Ang II is known to cause hypertension by increasing oxidative stress in subfornical organ (SFO) of circumventricular organs and via its projections to paraventricular nucleus and from there to the brain stem, finally resulting in increased sympathetic activity.55 cPLA2α is also present in the brain13,16 and intracerebroventricular administration of PGE2 increases sympathetic nervous activity, vasopressin release and BP.56 The demonstration that the effect of Ang II in increasing BP is mediated by activation of the EP1 receptor by PGE2, formed by COX-1 and not COX-2 in SFO, most likely by release of AA, suggests involvement of cPLA2.57 Therefore, it is possible that Ang II-induced hypertension in our study could be mediated by activation of cPLA2α in the SFO as well as in the cardiovascular and renal systems. Moreover, it has been reported that Ang II-salt hypertension, which is associated with increased sympathetic activity and increased plasma levels of norepinephrine, are minimized by inhibitor of COX-1, SC560 but not nemsulide, an inhibitor of COX 2 suggesting that COX-1 derived prostanoids by activating sympathetic nervous system, increase BP.58 In contrast, COX2 inhibitors rofecoxib and nimesulide have been shown to attenuate Ang II-induced oxidative stress, hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy in rats.59 The reason for the discrepancy between the two studies is unknown. Ang II is known to cause modulation of sympathetic outflow as determined by power spectral analysis of BP and heart rate variability 60. Our demonstration that the ratio of low frequency: high frequency heart rate variability as determined by power spectral analysis that was increased in cPLA2α+/+ mice, was reduced in cPLA2α−/− mice, suggests that AA metabolites also contributes to modulation of sympathetic outflow by Ang II.

The oxidative stress produced by Ang II in SFO is mediated by ER stress, and inhibitors of ER stress minimize Ang II-induced hypertension.27 Activation of cPLA2 is associated with increased ER stress.61 Inhibitors of ER stress reduce BP in spontaneously hypertensive rats and the effect of endothelial-derived contractile factors, by suppressing H2O2 production and expression of COX-1, ERK1/2 and cPLA2 phosphorylation.62 However, our demonstration that cPLA2α gene disruption prevented the cardiac expression of ER stress markers p58IPK and CHOP suggests that Ang II also increases ER stress in the heart, but cPLA2α acts upstream of ER stress and NADPH oxidase activity, most likely by generating AA/metabolites. The effect of vasoactive agents, including Ang II, to promote influx of calcium and translocation of cPLA2α to the nuclear envelope/ER,63 the site of AA metabolizing enzymes (COX, LO, and CYP P450),64–66 raises the possibility that cPLA2α via AA release and its metabolism by these enzymes might regulate generation of ER stress and ROS production. In support of this view, 12/15-LO has been implicated in ER stress in adipocytes, pancreatic islets, and rat liver.65

The increased ROS generated by Ang II promotes cardiovascular remodeling by activating one or more signaling molecules.29 Our finding that Ang II-induced hypertension was associated with increased cardiac ERK1/2 and cSrc activity in cPLA2α+/+ but not in cPLA2α−/− mice suggests that these signaling molecules are most likely activated by oxidative stress produced by cPLA2α-generated AA metabolites, thus contributing to cardiovascular remodeling.

In conclusion, the present study provides the first evidence that the selective release of AA by cPLA2α is crucial for the development of Ang II-induced hypertension and associated cardiovascular pathophysiological changes including cardiovascular remodeling, increased vascular reactivity, endothelial dysfunction, and cardiac inflammation. These effects are most likely mediated by oxidative11,26,29 and ER stress27,62 generated by AA metabolism65 and predominantly by pro-hypertensive eicosanoids resulting in activation of one or more signaling molecules including ERK1/2 and cSrc. However, studies using tissue specific knockout of cPLA2α and AA metabolizing enzymes would allow further assessment of their relative contribution in various tissues to Ang II- and other models of hypertension and associated pathogenesis.

Perspectives

The present study, using cPLA2α+/+ and cPLA2α−/− mice, demonstrates that cPLA2α selectively promotes release of AA from tissue phospholipids, a process that is critical for the development of Ang II-induced hypertension and associated cardiovascular remodeling and dysfunction, ER and oxidative stress, and inflammation. Moreover, our study suggests that cPLA2α might function as the major center of convergence for the transduction of hormone signaling and that endogenously released AA results in the production of eicosanoids that predominantly favor pro-hypertensive mechanisms including oxidative and ER stress and inflammation. Therefore, the development of water-soluble selective inhibitors of cPLA2α activity would allow assessing further, its contribution in cardiovascular and renal dysfunction in hypertension and its associated pathogenesis and treatment.

Novelty and Significance.

What is New?

Evidence that cPLA2α is essential for the development of Ang II-induced hypertension and associated cardiovascular remodeling, cardiac and endothelial dysfunction, and increased vascular reactivity.

Cardiac oxidative and ER stress and inflammation associated with Ang II-induced hypertension also depends on cPLA2α.

Ang II-induced cardiac dysfunction, remodeling, and inflammation that depend on cPLA2α are most likely mediated by ERK1/2 and cSrc.

What is Relevant?

Our study provides novel information on the mechanism of Ang II-induced hypertension and associated cardiovascular pathophysiological changes, whereby cPLA2α-generated AA and its metabolism to eicosanoids with pro-hypertensive effects is crucial for Ang II-induced hypertension.

These findings suggest that development of agents that selectively inhibit cPLA2α activity could be useful in treating hypertension and its pathogenesis.

Summary.

The present study demonstrates that cPLA2α gene disruption and AA metabolism inhibitor ETYA minimize Ang II-induced hypertension. Ang II-induced increase in SBP that was associated with increased urinary excretion of eicosanoids, cardiac dysfunction studied by echocardiography, cardiovascular remodeling, increased vascular reactivity, and endothelial dysfunction in cPLA2α+/+ mice was markedly reduced in cPLA2α−/− mice. Infusion of Ang II also increased cardiac infiltration of inflammatory cells, NADPH oxidase activity, and cardiovascular oxidative stress and expression of ER stress markers in cPLA2α+/+ but not cPLA2α−/− mice. Ang II increased cardiac ERK1/2 and cSrc activity in cPLA2α+/+ but not cPLA2α−/− mice. We conclude that cPLA2α is critical for Ang II-induced hypertension and associated cardiovascular dysfunction, remodeling, oxidative stress, and inflammation, most likely via AA release and generation of eicosanoids with pro-hypertensive effects and activation of ERK1/2 and cSrc.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. David Armbruster for editorial assistance.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant R01-HL-19134–39 (K.U.M). The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest/Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Kobori H, Nangaku M, Navar LG, Nishiyama A. The intrarenal renin-angiotensin system: from physiology to the pathobiology of hypertension and kidney disease. Pharmacol Rev. 2007;59:251–287. doi: 10.1124/pr.59.3.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rao GN, Lassegue B, Alexander RW, Griendling KK. Angiotensin II stimulates phosphorylation of high-molecular-mass cytosolic phospholipase A2 in vascular smoothmuscle cells. Biochem J. 1994;299:197–201. doi: 10.1042/bj2990197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGiff JC. Prostaglandins, prostacyclin, and thromboxanes. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1981;21:479–509. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.21.040181.002403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuhn H, Chaitidis P, Roffeis J, Walther M. Arachidonic Acid metabolites in the cardiovascular system: the role of lipoxygenase isoforms in atherogenesis with particular emphasis on vascular remodeling. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2007;50:609–620. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e318159f177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imig JD, Hammock BD. Soluble epoxide hydrolase as a therapeutic target for cardiovascular diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:794–805. doi: 10.1038/nrd2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roman RJ. P-450 metabolites of arachidonic acid in the control of cardiovascular function. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:131–185. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00021.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Audoly LP, Tilley SL, Goulet J, Key M, Nguyen M, Stock JL, McNeish JD, Koller BH, Coffman TM. Identification of specific EP receptors responsible for the hemodynamic effects of PGE2. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:H924–930. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.3.H924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Guan Y, Schneider A, Brandon S, Breyer RM, Breyer MD. Characterization of murine vasopressor and vasodepressor prostaglandin E(2) receptors. Hypertension. 2000;35:1129–1134. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.5.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nasjletti A. Arthur C. Corcoran Memorial Lecture. The role of eicosanoids in angiotensin-dependent hypertension. Hypertension. 1998;31:194–200. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.1.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith RL, Weidemann MJ. Reactive oxygen production associated with arachidonic acid metabolism by peritoneal macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1980;97:973–980. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(80)91472-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Touyz RM. Reactive oxygen species, vascular oxidative stress, and redox signaling in hypertension: what is the clinical significance? Hypertension. 2004;44:248–252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000138070.47616.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burke JE, Dennis EA. Phospholipase A2 structure/function, mechanism, and signaling. J Lipid Res. 2009;50 (Suppl):S237–242. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800033-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Linkous A, Yazlovitskaya E. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 as a mediator of disease pathogenesis. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12:1369–1377. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uozumi N, Kume K, Nagase T, Nakatani N, Ishii S, Tashiro F, Komagata Y, Maki K, Ikuta K, Ouchi Y, Miyazaki J-i, Shimizu T. Role of cytosolic phospholipase A2 in allergic response and parturition. Nature. 1997;390:618–622. doi: 10.1038/37622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hewson CA, Patel S, Calzetta L, Campwala H, Havard S, Luscombe E, Clarke PA, Peachell PT, Matera MG, Cazzola M, Page C, Abraham WM, Williams CM, Clark JD, Liu WL, Clarke NP, Yeadon M. Preclinical evaluation of an inhibitor of cytosolic phospholipase A2alpha for the treatment of asthma. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;340:656–665. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.186379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonventre JV, Huang Z, Taheri MR, O’Leary E, Li E, Moskowitz MA, Sapirstein A. Reduced fertility and postischaemic brain injury in mice deficient in cytosolic phospholipase A2. Nature. 1997;390:622–625. doi: 10.1038/37635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raichel L, Berger S, Hadad N, Kachko L, Karter M, Szaingurten-Solodkin I, Williams RO, Feldmann M, Levy R. Reduction of cPLA2alpha overexpression: an efficient anti-inflammatory therapy for collagen-induced arthritis. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:2905–2915. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hegen M, Sun L, Uozumi N, Kume K, Goad ME, Nickerson-Nutter CL, Shimizu T, Clark JD. Cytosolic Phospholipase A2α–deficient Mice Are Resistant to Collageninduced Arthritis. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1297–1302. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saito Y, Watanabe K, Fujioka D, Nakamura T, Obata JE, Kawabata K, Watanabe Y, Mishina H, Tamaru S, Kita Y, Shimizu T, Kugiyama K. Disruption of group IVA cytosolic phospholipase A(2) attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury partly through inhibition of TNF-alpha-mediated pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:16. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00955.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonventre JV, Swidler M. Calcium dependency of prostaglandin E2 production in rat glomerular mesangial cells. Evidence that protein kinase C modulates the Ca2+-dependent activation of phospholipase A2. J Clin Invest. 1988;82:168–176. doi: 10.1172/JCI113566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muthalif MM, Benter IF, Uddin MR, Harper JL, Malik KU. Signal Transduction Mechanisms Involved in Angiotensin-(1–7)-Stimulated Arachidonic Acid Release and Prostanoid Synthesis in Rabbit Aortic Smooth Muscle Cells. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1998;284:388–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trevisi L, Bova S, Cargnelli G, Ceolotto G, Luciani S. Endothelin-1-induced arachidonic acid release by cytosolic phospholipase A2 activation in rat vascular smooth muscle via extracellular signal-regulated kinases pathway. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;64:425–431. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muthalif MM, Benter IF, Uddin MR, Malik KU. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIalpha mediates activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase and cytosolic phospholipase A2 in norepinephrine-induced arachidonic acid release in rabbit aortic smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:30149–30157. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.30149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawaguchi H, Saito H, Yasuda H. Renal prostaglandins and phospholipase A2 in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Hypertens. 1987;5:299–304. doi: 10.1097/00004872-198706000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanaka K, Yamamoto Y, Ogino K, Tsujimoto S, Saito M, Uozumi N, Shimizu T, Hisatome I. Cytosolic phospholipase A2alpha contributes to blood pressure increases and endothelial dysfunction under chronic NO inhibition. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:1133–1138. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.218370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rajagopalan S, Kurz S, Munzel T, Tarpey M, Freeman BA, Griendling KK, Harrison DG. Angiotensin II-mediated hypertension in the rat increases vascular superoxide production via membrane NADH/NADPH oxidase activation. Contribution to alterations of vasomotor tone. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1916–1923. doi: 10.1172/JCI118623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Young CN, Cao X, Guruju MR, Pierce JP, Morgan DA, Wang G, Iadecola C, Mark AL, Davisson RL. ER stress in the brain subfornical organ mediates angiotensin-dependent hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3960–3964. doi: 10.1172/JCI64583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schroder M, Kaufman RJ. The mammalian unfolded protein response. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005;74:739–789. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mehta PK, Griendling KK. Angiotensin II cell signaling: physiological and pathological effects in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C82–97. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00287.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leslie CC. Properties and regulation of cytosolic phospholipase A2. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16709–16712. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.27.16709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sapirstein A, Bonventre JV. Specific physiological roles of cytosolic phospholipase A(2) as defined by gene knockouts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1488:139–148. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Downey P, Sapirstein A, O’Leary E, Sun TX, Brown D, Bonventre JV. Renal concentrating defect in mice lacking group IV cytosolic phospholipase A(2) Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;280:F607–618. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.280.4.F607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Griffin SA, Brown WC, MacPherson F, McGrath JC, Wilson VG, Korsgaard N, Mulvany MJ, Lever AF. Angiotensin II causes vascular hypertrophy in part by a non-pressor mechanism. Hypertension. 1991;17:626–635. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.17.5.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Su EJ, Lombardi DM, Siegal J, Schwartz SM. Angiotensin II induces vascular smooth muscle cell replication independent of blood pressure. Hypertension. 1998;31:1331–1337. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.6.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mervaala E, Muller DN, Schmidt F, Park JK, Gross V, Bader M, Breu V, Ganten D, Haller H, Luft FC. Blood pressure-independent effects in rats with human renin and angiotensinogen genes. Hypertension. 2000;35:587–594. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.2.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Letavernier E, Perez J, Bellocq A, Mesnard L, de Castro Keller A, Haymann JP, Baud L. Targeting the calpain/calpastatin system as a new strategy to prevent cardiovascular remodeling in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Circ Res. 2008;102:720–728. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.160077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alexander LD, Alagarsamy S, Douglas JG. Cyclic stretch-induced cPLA2 mediates ERK 1/2 signaling in rabbit proximal tubule cells. Kidney Int. 2004;65:551–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sarr M, Chataigneau M, Martins S, Schott C, El Bedoui J, Oak MH, Muller B, Chataigneau T, Schini-Kerth VB. Red wine polyphenols prevent angiotensin II-induced hypertension and endothelial dysfunction in rats: role of NADPH oxidase. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;71:794–802. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zanchi A, Schaad NC, Osterheld MC, Grouzmann E, Nussberger J, Brunner HR, Waeber B. Effects of chronic NO synthase inhibition in rats on renin-angiotensin system and sympathetic nervous system. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:H2267–2273. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.6.H2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sander M, Victor RG. Neural mechanisms in nitric-oxide-deficient hypertension. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 1999;8:61–73. doi: 10.1097/00041552-199901000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guzik TJ, Hoch NE, Brown KA, McCann LA, Rahman A, Dikalov S, Goronzy J, Weyand C, Harrison DG. Role of the T cell in the genesis of angiotensin II induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2449–2460. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barhoumi T, Kasal DA, Li MW, Shbat L, Laurant P, Neves MF, Paradis P, Schiffrin EL. T regulatory lymphocytes prevent angiotensin II-induced hypertension and vascular injury. Hypertension. 2011;57:469–476. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.162941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zafari AM, Ushio-Fukai M, Minieri CA, Akers M, Lassegue B, Griendling KK. Arachidonic acid metabolites mediate angiotensin II-induced NADH/NADPH oxidase activity and hypertrophy in vascular smooth muscle cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 1999;1:167–179. doi: 10.1089/ars.1999.1.2-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yaghini FA, Song CY, Lavrentyev EN, Ghafoor HUB, Fang XR, Estes AM, Campbell WB, Malik KU. Angiotensin II–Induced Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Migration and Growth Are Mediated by Cytochrome P450 1B1–Dependent Superoxide Generation. Hypertension. 2010;55:1461–1467. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.150029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao X, Bey EA, Wientjes FB, Cathcart MK. Cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) regulation of human monocyte NADPH oxidase activity. cPLA2 affects translocation but not phosphorylation of p67(phox) and p47(phox) J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25385–25392. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203630200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pessach I, Leto TL, Malech HL, Levy R. Essential requirement of cytosolic phospholipase A(2) for stimulation of NADPH oxidase-associated diaphorase activity in granulocyte-like cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33495–33503. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011417200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guan Y, Zhang Y, Wu J, Qi Z, Yang G, Dou D, Gao Y, Chen L, Zhang X, Davis LS, Wei M, Fan X, Carmosino M, Hao C, Imig JD, Breyer RM, Breyer MD. Antihypertensive effects of selective prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype 1 targeting. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2496–2505. doi: 10.1172/JCI29838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen L, Miao Y, Zhang Y, Dou D, Liu L, Tian X, Yang G, Pu D, Zhang X, Kang J, Gao Y, Wang S, Breyer MD, Wang N, Zhu Y, Huang Y, Breyer RM, Guan Y. Inactivation of the E-prostanoid 3 receptor attenuates the angiotensin II pressor response via decreasing arterial contractility. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:3024–3032. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.254052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mistry M, Nasjletti A. Role of pressor prostanoids in rats with angiotensin II-salt-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 1988;11:758–762. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.11.6.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anning PB, Coles B, Bermudez-Fajardo A, Martin PE, Levison BS, Hazen SL, Funk CD, Kuhn H, O’Donnell VB. Elevated endothelial nitric oxide bioactivity and resistance to angiotensin-dependent hypertension in 12/15-lipoxygenase knockout mice. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:653–662. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62287-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muthalif MM, Benter IF, Khandekar Z, Gaber L, Estes A, Malik S, Parmentier JH, Manne V, Malik KU. Contribution of Ras GTPase/MAP kinase and cytochrome P450 metabolites to deoxycorticosterone-salt-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2000;35:457–463. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.1.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu CC, Gupta T, Garcia V, Ding Y, Schwartzman ML. 20-HETE and blood pressure regulation: clinical implications. Cardiol Rev. 2014;22:1–12. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e3182961659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang F, Lu X, Peng K, Du Y, Zhou SF, Zhang A, Yang T. Prostaglandin E-Prostanoid4 Receptor Mediates Angiotensin II-Induced (Pro)Renin Receptor Expression in the Rat Renal Medulla. Hypertension. 2014;64:369–377. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kriska T, Cepura C, Magier D, Siangjong L, Gauthier KM, Campbell WB. Mice lacking macrophage 12/15-lipoxygenase are resistant to experimental hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H2428–2438. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01120.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Davisson RL. Physiological genomic analysis of the brain renin-angiotensin system. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;285:R498–511. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00190.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Okuno T, Lindheimer MD, Oparil S. Central effects of prostaglandin E2 on blood pressure and plasma renin activity in rats. Role of the sympathoadrenal system and vasopressin. Hypertension. 1982;4:809–816. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.4.6.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cao X, Peterson JR, Wang G, Anrather J, Young CN, Guruju MR, Burmeister MA, Iadecola C, Davisson RL. Angiotensin II-dependent hypertension requires cyclooxygenase 1-derived prostaglandin E2 and EP1 receptor signaling in the subfornical organ of the brain. Hypertension. 2012;59:869–876. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.182071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Asirvatham-Jeyaraj N, King AJ, Northcott CA, Madan S, Fink GD. Cyclooxygenase-1 inhibition attenuates angiotensin II-salt hypertension and neurogenic pressor activity in the rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;305:H1462–1470. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00245.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu R, Laplante MA, de Champlain J. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors attenuate angiotensin II-induced oxidative stress, hypertension, and cardiac hypertrophy in rats. Hypertension. 2005;45:1139–1144. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000164572.92049.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jun JY, Zubcevic J, Qi Y, Afzal A, Carvajal JM, Thinschmidt JS, Grant MB, Mocco J, Raizada MK. Brain-mediated dysregulation of the bone marrow activity in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2012;60:1316–1323. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.199547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ren G, Takano T, Papillon J, Cybulsky AV. Cytosolic phospholipase A(2)-alpha enhances induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;4:468–481. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Spitler KM, Matsumoto T, Webb RC. Suppression of endoplasmic reticulum stress improves endothelium-dependent contractile responses in aorta of the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;305:H344–353. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00952.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Freeman EJ, Ruehr ML, Dorman RV. ANG II-induced translocation of cytosolic PLA2 to the nucleus in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C282–288. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.1.C282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rollins TE, Smith WL. Subcellular localization of prostaglandin-forming cyclooxygenase in Swiss mouse 3T3 fibroblasts by electron microscopic immunocytochemistry. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:4872–4875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cole BK, Kuhn NS, Green-Mitchell SM, Leone KA, Raab RM, Nadler JL, Chakrabarti SK. 12/15-Lipoxygenase signaling in the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;302:E654–665. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00373.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Seliskar M, Rozman D. Mammalian cytochromes P450--importance of tissue specificity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1770:458–466. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]