Abstract

Aims

Loss-of-function mutations in Calsequestrin 2 (CASQ2) are associated with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT). CPVT patients also exhibit bradycardia and atrial arrhythmias for which the underlying mechanism remains unknown. We aimed to study the sinoatrial node (SAN) dysfunction due to loss of CASQ2.

Methods and results

In vivo electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring, in vitro high-resolution optical mapping, confocal imaging of intracellular Ca2+ cycling, and 3D atrial immunohistology were performed in wild-type (WT) and Casq2 null (Casq2−/−) mice. Casq2−/− mice exhibited bradycardia, SAN conduction abnormalities, and beat-to-beat heart rate variability due to enhanced atrial ectopic activity both at baseline and with autonomic stimulation. Loss of CASQ2 increased fibrosis within the pacemaker complex, depressed primary SAN activity, and conduction, but enhanced atrial ectopic activity and atrial fibrillation (AF) associated with macro- and micro-reentry during autonomic stimulation. In SAN myocytes, CASQ2 deficiency induced perturbations in intracellular Ca2+ cycling, including abnormal Ca2+ release, periods of significantly elevated diastolic Ca2+ levels leading to pauses and unstable pacemaker rate. Importantly, Ca2+ cycling dysfunction occurred not only at the SAN cellular level but was also globally manifested as an increased delay between action potential (AP) and Ca2+ transient upstrokes throughout the atrial pacemaker complex.

Conclusions

Loss of CASQ2 causes abnormal sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release and selective interstitial fibrosis in the atrial pacemaker complex, which disrupt SAN pacemaking but enhance latent pacemaker activity, create conduction abnormalities and increase susceptibility to AF. These functional and extensive structural alterations could contribute to SAN dysfunction as well as AF in CPVT patients.

Keywords: Sinoatrial node, Calsequestrin 2, Optical mapping, Autonomic nervous system, Sinoatrial node dysfunction

Introduction

Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) is a malignant, inherited arrhythmic syndrome characterized by physical or emotional stress-induced bidirectional or polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in structurally normal hearts, with a high fatal event rate in untreated patients.1,2 Approximately 60% of CPVT patients have mutations in genes encoding either the cardiac Ca2+ release channel, the ryanodine receptor (RyR2), or the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+-binding protein, calsequestrin 2 (CASQ2).2–6 Interestingly, humans harbouring Casq2 loss-of-function mutations associated with CPVT in addition to triggered ventricular arrhythmias display a depressed sinus heart rate at rest,2,7,8 which is also observed in a Casq2−/− mouse model.9

Both experimental and numerical modelling studies have demonstrated that spontaneous beating of the sinoatrial node (SAN) is initiated, sustained, and regulated by a coupled system of the If-dependent voltage clock and intracellular Ca2+ clock driven by localized subsarcolemmal Ca2+ releases via ryanodine receptors in the SR which trigger INCX during late diastolic depolarization.10–13 However, surprisingly, despite the fact that Casq2 deletion enhances spontaneous Ca2+ release from the SR,14 Casq2−/− mice paradoxically exhibit sinus bradycardia9 rather than the expected increase in spontaneous SAN or atrial automaticity based on the Ca2+ clock theory.12

To identify the mechanism involved in the observed bradycardia, we developed an integrated approach combining high resolution optical mapping in parallel with 3D immunohistological reconstruction of mouse atrial pacemaker complex to define the structural and functional remodelling responsible for SAN dysfunction in the Casq2−/− mouse heart. This combination, along with isolated SAN cell studies, offers a powerful approach to unmask and resolve in precise detail, the dynamic activation patterns of the whole atrial pacemaker complex, and correlates it with structural alterations of pacemaker clusters.

Materials and methods

An expanded Materials and methods section is found in the Supplementary material online.

Mice

All procedures were carried out in compliance with the standards for the care and use of animal subjects as stated in the Guide of the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication No. 85–23, revised 1996). Protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Ohio State University. All animals used in this study received humane care in compliance with the National Institutes of Health's Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Data were obtained from 3 months and 12 months old wild-type (WT) and FVB/N Casq2 null (Casq2−/−) mice.9

Echocardiography and electrocardiogram recordings in vivo

Systolic and diastolic function were assessed by echocardiographic examination in lightly anaesthetized (1.5% isoflurane) mice using the Vevo 2100 echocardiograph system as previously described.14 A standard isoproterenol (Iso, 1.5 mg/kg i.p.) testing protocol was used to provoke heart rhythm abnormalities in lightly anaesthetized mice.15

Optical mapping of the isolated sinoatrial node and whole heart preparations

Optical mapping of electrical activity of the isolated mouse atrial preparation, which included the SAN, atrioventricular junction (AVJ), and both atria, was performed as previously described.16,17 Simultaneous voltage and calcium transient optical mapping of isolated Langendorff-perfused hearts from both WT (n = 6) and Casq2−/− mice (n = 6) was conducted as described previously.18

Intracellular confocal Ca2+ recordings

Intracellular Ca2+ recordings in isolated SAN cells14,17 were done under constant perfusion of Tyrode solution with and without 10 nM Iso treatment, RT.

Histology and immunofluorescence labelling

The preparations were stained with Masson trichrome (International Medical Equipment, San Marcos, CA, USA) and immunostained with Rb-Cx43 (1:400; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and Ms-HCN4 (1:400; Sigma) as previously described.19

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data are shown as mean ± SD. Analysis was done in SAS 9.2 (Cary, NC, USA) using a PROC FREQ procedure, Fisher's exact test, unpaired Student's t-test or repeat measurements ANOVA appropriately. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Sinus nodal bradycardia and profound beat-to-beat alterations in P-wave morphology in Casq2−/− mice

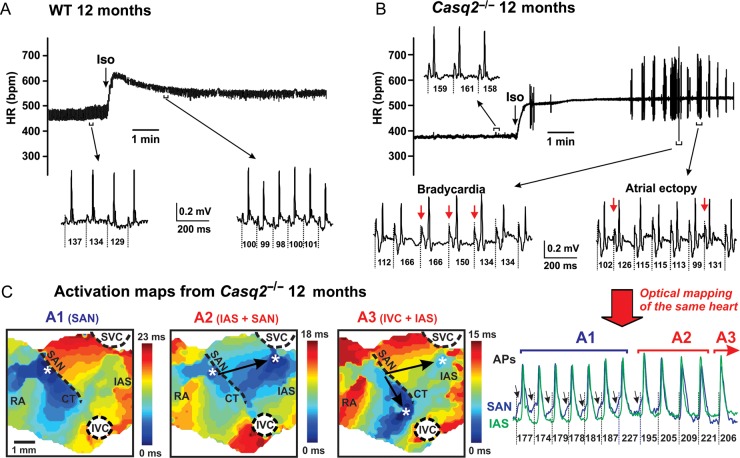

In contrast to WT (Figure 1A), Casq2−/− mice demonstrated a significantly slower heart rate both at baseline and during sympathetic stimulation (Figure 1B; Supplementary material online, Figure SIA). β-Adrenergic challenge with Iso triggered ventricular arrhythmias in anaesthetized Casq2−/− mice as reported earlier.9 In addition, we found frequent atrial arrhythmias including atrial ectopic activity and bradycardia during sympathetic stimulation (Supplementary material online, Figure S1C). Atrial ectopic activity was characterized by profound beat-to-beat alterations of ECG P-wave morphology and dramatically increased heart rate variation [cycle length (CL)] varied from 99 to 166 ms at the selected recording (Figure 1B; Supplementary material online, Figure S1B). Increasing age further slowed the heart rate and increased heart rhythm variation in Casq2−/− mice (Supplementary material online, Figure S1).

Figure 1.

Casq2−/− mice display sinus bradycardia and catecholaminergic atrial ectopy associated with multiple competing pacemakers located within the atrial pacemaker complex. (A and B) Heart rhythm (HR) changes recorded in 12-month wild-type and Casq2−/− mice during injection of isoproterenol (1.5 mg/kg i.p.). Representative electrocardiogram recordings obtained before and after injection of isoproterenol are shown. (C), When optically mapped, the same Casq2−/− mouse shown in (B) exhibited a similar heart rate variability which was associated with beat-to-beat competition of multiple atrial pacemakers. Optical action potentials (AP) were recorded from an isolated atria preparation from an inferior part of the sinoatrial node (blue) and inter-atrial septum (green) regions. Atrial activation contour maps reconstructed for A1-A3 activation patterns marked on panel optical action potentials. A site of the earliest atrial activation site is labelled by an asterisk. SVC and IVC, superior and inferior vena cava; RAA and LAA, right and left atrial appendages; RV and LV, right and left ventricles; CT, crista terminalis; IAS, inter-atrial septum; AVJ, atrioventricular junction.

Multiple competing pacemakers underlie the enhanced atrial ectopic activity in Casq2−/− mice

Similar to ECG abnormalities, Casq2−/− mice also displayed an increased atrial ectopy accompanied by beat-to-beat heart rate variation during optical mapping of isolated SAN preparations. Detailed optical mapping analyses of the atrial pacemaker complex revealed that the ectopic beats with intrinsically varying heart rates primarily arose from latent pacemaker sites (compare activation patterns A1, A2, and A3 in Figure 1C). In conjunction with primary SAN dysfunction, beat-to-beat competition between multiple ectopic pacemakers appears to underlie a significantly increased heart rate variation observed in ECG measurements from mice and in isolated SAN preparations (Supplementary material online, Figures S1and S2). Interestingly, when separated by an incision along the superior–inferior vena cava (SVC–IVC) axis in the 3-month Casq2−/− atrial preparation perfused under Iso, the ectopic pacemaker in inter-atrial septum (IAS) had a higher pacemaking rate (9.75 Hz) than SAN (9.3 Hz) (Supplementary material online, Figure S3), while an isolated SAN pacemaker in 3-month WT mice had a significantly higher intrinsic rate (9.9 Hz).

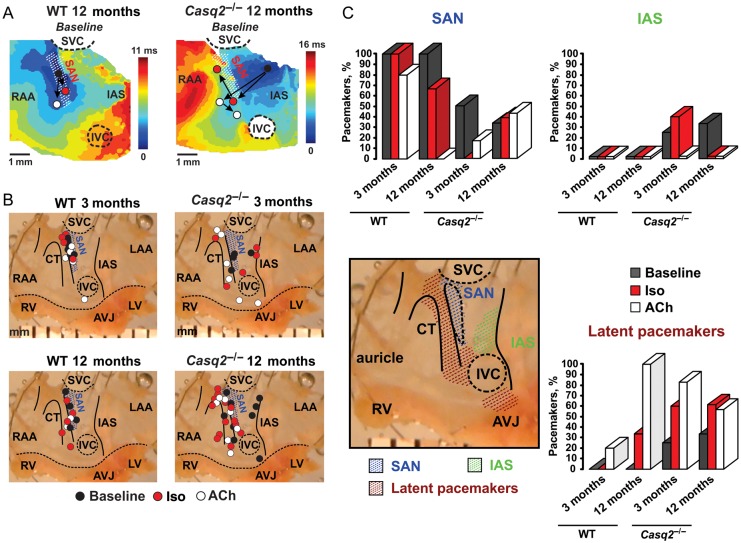

In WT mice, all leading pacemakers were stably localized within the anatomically defined SAN (Figure 2A, left panel). Iso shifted the leading pacemaker site superiorly within the SAN area, while acetylcholine (ACh) shifted the leading pacemaker either inferiorly within the SAN (preferentially) or abruptly towards the AVJ (Figure 2B–C).

Figure 2.

Calsequestrin 2 knockout leads to architectural remodelling of the atrial pacemaker complex. (A) Typical examples of atrial activation patterns reconstructed for the 12-mo wild-type (left panel) and Casq2−/− (right panel) mice at baseline. Location of leading pacemaker sites is shown at baseline (black circle) and during beta-adrenergic (red circle) and cholinergic (white circle) stimulations. White dotted line hatched area represents the sinoatrial node complex. (B) Effects of β-adrenergic (isoproterenol, red) and cholinergic (acetylcholine, white) stimulation on the leading pacemaker site location in 3 months and 12 months, wild-type (n = 5 and 4) and Casq2−/− (n = 4 and 9) mice. One photo of 12-month Casq2−/− atrial preparation was used for anatomical reference on all four panels. The location of the leading pacemaker is shown by circles. One mouse could have several sites of the leading pacemaker location because of the presence of multiple competing pacemakers. Blue dotted line hatched area represents the sinoatrial node complex. The maximum anatomical displacement of the leading pacemaker under either beta-adrenergic or cholinergic stimulation is shown. The dose-dependent shift of the leading pacemaker in wild-type mice is shown in Supplementary material online, Figures S4–S7. (C) Distribution (in % of total pacemakers registered in each mouse group) of leading pacemakers located in the sinoatrial node area (blue), inter-atrial septum (green), and throughout the latent pacemakers (brown) in different mouse groups at baseline (black) and under beta-adrenergic (isoproterenol, red) and cholinergic (acetylcholine, white) stimulation. Abbreviations are the same as those in Figure 1.

In Casq2−/− atrial preparations, under baseline conditions, a majority of leading pacemakers' sites (50 and 72% in 3-month and 12-month mice, respectively) were located outside the anatomically defined SAN area (Figure 2A–C). Out of these, pacemakers located in the IAS region were observed in 25% of 3 months and in 40% of 12 months Casq2−/− mice, but never in WT. Under β-adrenergic stimulation, Casq2−/− mice demonstrated a disorganized shift of the leading pacemaker farther towards either IAS or other latent atrial pacemakers (Figure 2B–C).

Together with enhanced ectopic activity, isolated Casq2−/− atrial preparations demonstrated a significantly slower heart rhythm during β-adrenergic (Figure 3A) and cholinergic (Figure 3B) stimulations similar to that observed in intact animals (Supplementary material online, Figure S1). Interestingly, Casq2−/− preparations exhibited a higher sensitivity to cholinergic stimulation compared with WT preparations (heart rhythm changes compared with control: 14 ± 7% vs. 32 ± 17% and 7 ± 5% vs. 17 ± 3% in 3-month and 12-month groups, respectively, P < 0.05; (Supplementary material online, Figure S8)). Ageing slowed baseline heart rhythm in WT and Casq2−/− mice and also significantly decreased the range of heart rhythm changes during autonomic stimulation (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Heart rhythm alterations during autonomic stimulation. (A), isoproterenol concentration-effect curve data obtained from 3-month (left) and 12-month (right) wild-type (n = 5 and 5) and Casq2−/− (n = 4 and 7) isolated sinoatrial node preparations. (B) Acetylcholine concentration-effect curve data obtained from 3-month (left) and 12-month (right) wild-type (n = 6 and 5) and Casq2−/− (n = 4 and 7) isolated sinoatrial node preparations. (C) Range for heart rhythm changes during autonomic stimulation. Left: Absolute values of heart rate at baseline and during isoproterenol or acetylcholine perfusion for all mouse groups studied. Right: A difference between the maximum heart rate measured during sympathetic stimulation and the minimum heart rate measured during parasympathetic stimulation in 3-month and 12-month wild-type and Casq2−/−- mice. *P < 0.05 vs. age-matched wild-type.

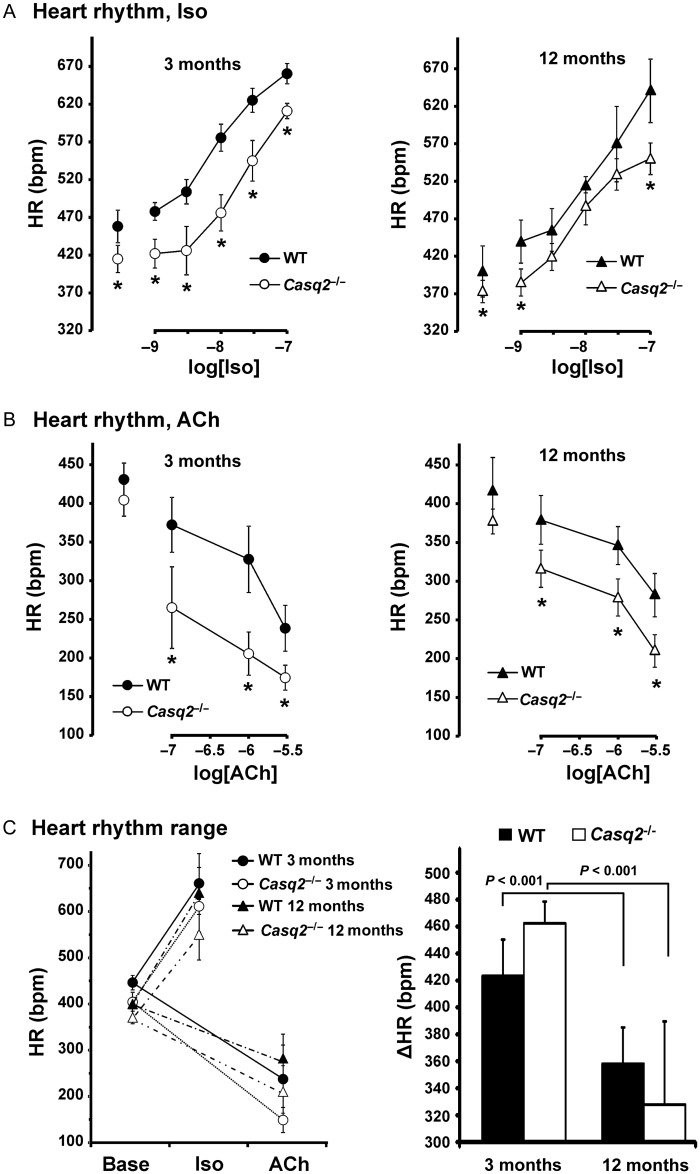

Casq2−/− atrial preparations reveal conduction slowing and prolonged sinoatrial node recovery times

During atrial pacing, conduction was slowed in the Casq2−/− RA free wall region and more pronounced within the region of extended SAN block zone associated with enhanced fibrosis (Figure 4A–B). The location of the first post-pacing atrial beat was markedly shifted inferiorly either to the IVC or to the AVJ in Casq2−/− mice compared with WT (Supplementary material online, Figure S9). Both 3-month and 12-month WT mice demonstrated a faster recovery of the SAN (SANRT) during both control and Iso perfusion, compared with age-matched Casq2−/− mice.

Figure 4.

Enhanced fibrosis, sinoatrial node conduction blocks and atrial enlargement in Casq2−/− hearts. (A) Representative examples of atrial activation during sinoatrial node recovery time measurements in 12-month wild-type (left) and 12-month Casq2−/− (right) mice at baseline. Activation maps were obtained at continuous pacing (S1S1= 100 ms) during SANRT measurements at baseline. Abbreviations are the same as those in Figure 1. (B) Average data for conduction velocity measured in Right atrial free wall (RA) and within the pacemaker complex at S1S1= 100 ms pacing in both 3-month and 12-month wild-type (n = 4 and 3) and Casq2−/− (n = 4 and 3) mice. (C) Histological analysis of the atrial pacemaker complex in wild-type and Casq2−/− mice is shown. Top panel: 3-month wild-type mouse demonstrates a typical sinoatrial node activation at control. Isoproterenol 30 nM shifted the site of the earliest activation (white asterisk) superiorly within the sinoatrial node area. Histological staining of the same sinoatrial node preparation shown in activation maps confirms location of the mouse sinoatrial node. Sections were cut through the sinoatrial node preparation parallel to the surface. An enlarged part of the stained preparation (marked by a red dotted rectangle on the activation map) demonstrates the compact part of the sinoatrial node separated from the atrial muscle on other side by connective tissue. Bottom panel: 12-month Casq2−/− heart demonstrates structural remodelling of the atrial pacemaker complex. A detailed histological reconstruction of the same 3-month wild-type sinoatrial node preparation is shown in Supplementary material online, Figures S10 and S11. (D) Average ratio of fibrotic tissue content to cardiac tissue measured in different areas in both 3-month and 12-month wild-type (n = 8 and 7) and Casq2−/− (n = 7 and 9) mouse hearts. (E) Atrial tissue area calculated for both right and left atria in both 3-month and 12-month wild-type (n = 8 and 5) and Casq2−/− (n = 4 and 7) mouse hearts.

Loss of calsequestrin 2 is accompanied by atrial hypertrophy and increased fibrosis throughout the pacemaker complex

Depression of the SAN conduction and pacemaking, as well as subsequent shift of the leading pacemaker towards the IAS, correlates with increased content of fibrotic tissue in Casq2−/− mice exclusively within the pacemaker complex (Figure 4C and D). An increase in left and right atrial size was observed in both 3-month and 12-month mice suggesting atrial hypertrophy in these animals (Figure 4D); however, while cardiac function was not affected in 3-month Casq2−/− (Supplementary material online, Table S1) a moderate cardiomyopathy was found in 12-month Casq2−/− hearts compared with age-matched WT mice. These data show that loss of CASQ2, in addition to inducing CPVT, could affect cardiac function and potentially lead to cardiomyopathy upon ageing.

Locations of ectopic beats coincide with atrial pacemaker clusters in Casq2−/− atria

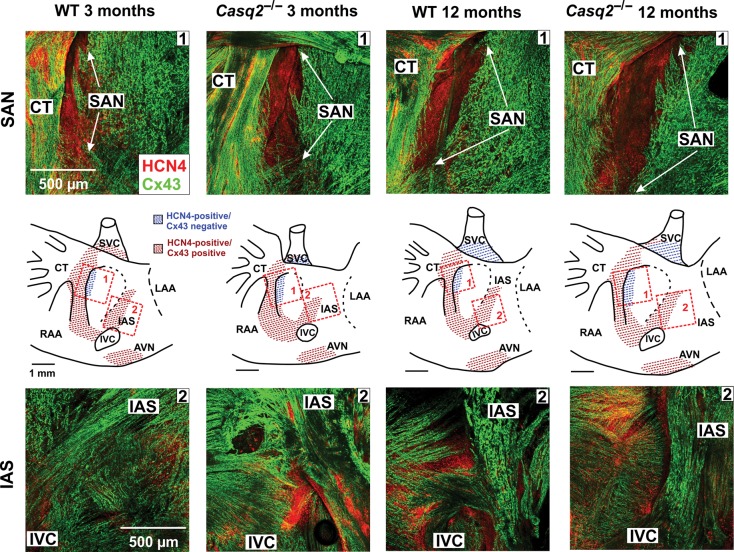

Figure 5 demonstrates the primary pacemaker, SAN, exclusively shown as HCN4-positive and Cx43-negative area (marked by arrows) as well as the latent pacemaker region in IAS characterized by both HCN4- and Cx43-positive staining. However, latent pacemaker areas do not represent co-localization of the two proteins, but indicate distinct regions of HCN4 positivity overlaid by a layer of Cx43 positivity unlike the SAN region that is devoid of an overlay of Cx43 immunostaining. Importantly, all leading pacemaker sites observed during mapping studies (Figure 2) correspond to these HCN4-positive pacemaker regions. Detailed mosaic reconstructions of the entire atrial preparation are shown in Supplementary material online, Figures S12 and S13.

Figure 5.

3-D reconstruction of the atrial pacemaker complex used for immunofluorescent labelling of connexin 43 (Cx43, green) and HCN4 (red) are shown. The enlarged images demonstrate superimposition of Z-stacks (averaged through 30–50 scanned layers; 50–200 µm thickness) of the sinoatrial node and inter-atrial septum regions. The schematic outlines of the mouse sinoatrial node preparation with areas selected for immonostaining are shown for each mouse. Abbreviations are the same as those in Figure 1.

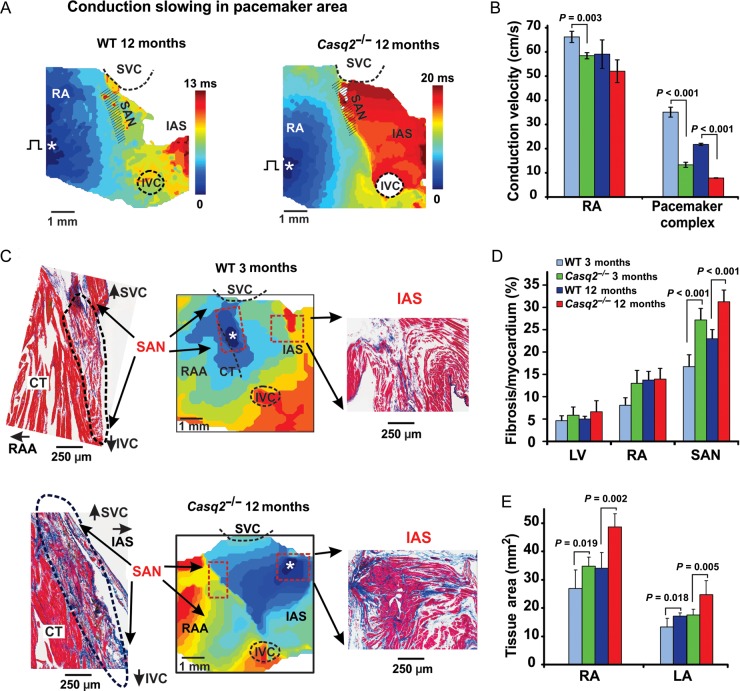

Increased sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release and abnormal pauses interrupt spontaneous activity in isolated Casq2−/− sinoatrial node cells

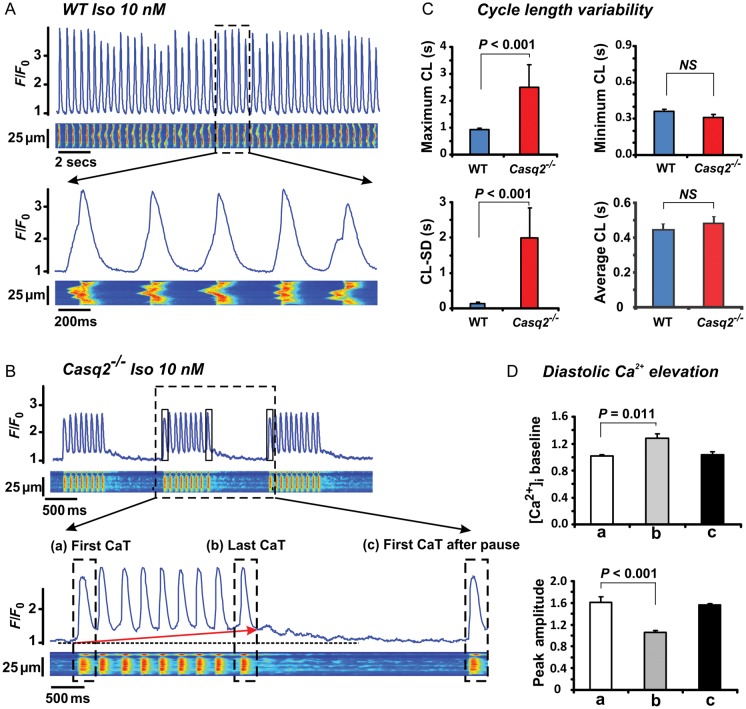

In order to investigate the mechanisms responsible for SAN dysfunctions at the cellular level, confocal Ca2+ imaging was done in isolated SAN cells from Casq2−/− and WT mice (Figure 6A and B). The SAN cells used for the study were spindle-shaped and showed the characteristic HCN4 positive and Cx43 negative staining patterns (Supplementary material online, Figure S14). Although average CL and minimal CL did not significantly differ from those of aged-matched WT SAN myocytes, maximum CLs as well as CL variability in the Casq2−/− cells were significantly increased both with (Supplementary material online, Figure S15) and without Iso treatment (Figure 6C). At the same time, Iso significantly decreased the amplitude while increasing the 80% decay time of Ca2+ transient in Casq2−/− myocytes (Supplementary material online, Figure S16).

Figure 6.

Intracellular confocal Ca2+ imaging during 10 nM isoproterenol treatment in sinoatrial node myocytes isolated from 3-month wild-type and Casq2−/− hearts. (A) Ca2+ transient (CaT) recordings obtained from wild-type and (B) Casq2−/− sinoatrial node cells in the presence of isoproterenol. Below the recordings, enlarged segments are shown. During isoproterenol challenge, spontaneous activity in Casq2−/− sinoatrial node myocytes was interrupted by pauses preceded by a significant increase in the baseline values. (C) Summary data for cycle length variability (CLmax – CLmin) (shown as standard deviation, CL-SD). (D) Summary data of changes in baseline diastolic Ca2+ values and peak amplitude of (a) the first transient, (b) the last transient (during the short periods of increased baseline) and (c) the first transient after a pause.

Notably, most Casq2−/− SAN pacemaker cells showed pauses in spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations (defined as absence of spontaneous Ca2+ transients/beat for greater than average CLs) interspersed between the periods of spontaneous activity (Figure 6B, Iso panel). These pauses were evident at baseline [in Casq2−/−: 4/11 cells (36%) vs. WT: 0/11 cells (P= 0.09)]; however, Iso markedly increased pause incidence [in Casq2−/−: 9/11 cells (74%) vs. WT: 0/11 cells (P= 0.0002)]. Interestingly, the pauses were invariably preceded by progressive elevation of baseline diastolic Ca2+ and simultaneous decrease in amplitude of Ca2+ transients. Rhythmic Ca2+ oscillations resumed only when the baseline Ca2+ returned back to its original level (Figure 6D). The increased baseline Ca2+ that precedes the pauses in Casq2−/− SAN cells is likely caused by enhanced diastolic SR Ca2+ release in these cells. Consistent with this possibility, the frequency of sparks and their duration were significantly increased in Casq2−/− cells (Supplementary material online, Figure S17A). Additionally, the incidence of propagating Ca2+ waves increased in Casq2−/− cells compared with WT in the presence of Iso (Supplementary material online, Figure S15B).

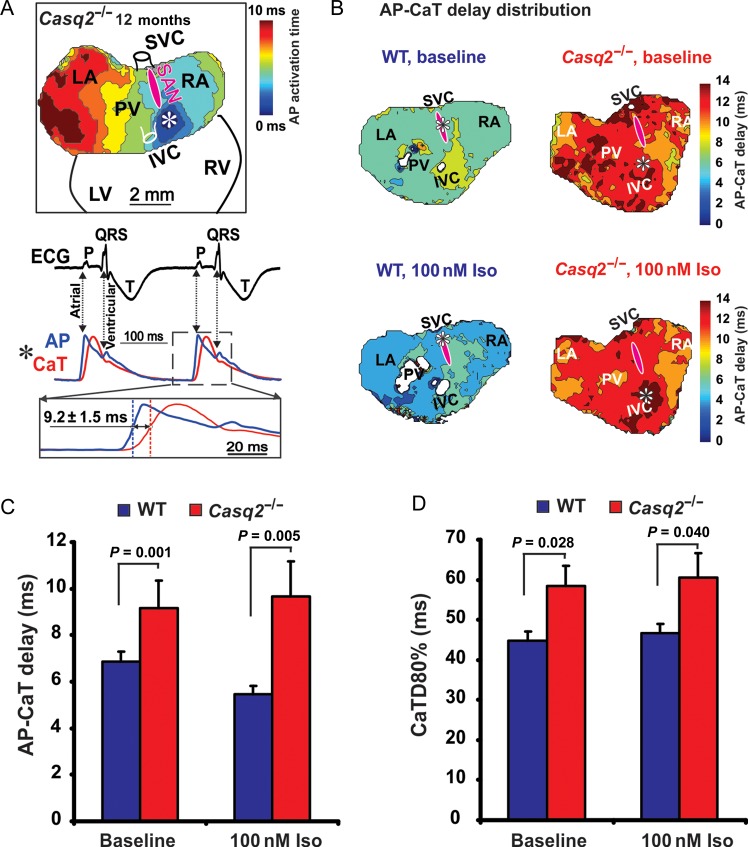

Calsequestrin 2 deficiency increases delay between the upstrokes of the action potential and SR Ca2+ transient in whole hearts

Simultaneous voltage/Ca2+ optical mapping during spontaneous rhythm using isolated Langendorff-perfused hearts revealed that the delay between the upstroke of the action potential (AP) and the rise of calcium transient as well as the duration of the calcium transient (CaTD80%) were significantly increased in the Casq2−/− mice at baseline as well as with Iso compared to WT (Figure 7A–D).

Figure 7.

Simultaneous mapping of Optical action potential (AP) and Ca2+ transient (CaT) in intact Casq2−/− hearts during spontaneous rhythm. (A) A representative example of AP-CaT optical mapping from 12-month Casq2−/− Langendorff-perfused heart. The earliest activation site is shown by asterisk and is located outside the sinoatrial node (pink oval). Below the atrial activation map, electrocardiogram with simultaneous AP and CaT recordings from the site of ectopic beat (asterisk) are shown. Below, close-up view of superimposed upstrokes with illustrations of AP-CaT delay is shown. (B) Colour contour maps for AP-CaT upstroke delay distribution in wild-type and Casq2−/− atria at baseline and during 100nM isoproterenol perfusion. The earliest activation sites are shown by asterisks. The same colour time scale was used for all hearts to demonstrate a difference between them. Abbreviations are the same as those in Figure 1. (C) Average data for AP-CaT delay measured in wild-type (n = 6) and Casq2−/− (n = 6) hearts. (D) Average data for CaT duration at 80% of decay (CaTD80%) measured at baseline and during perfusion with 100nM isoproterenol in wild-type (n = 6) and Casq2−/− (n = 6) hearts.

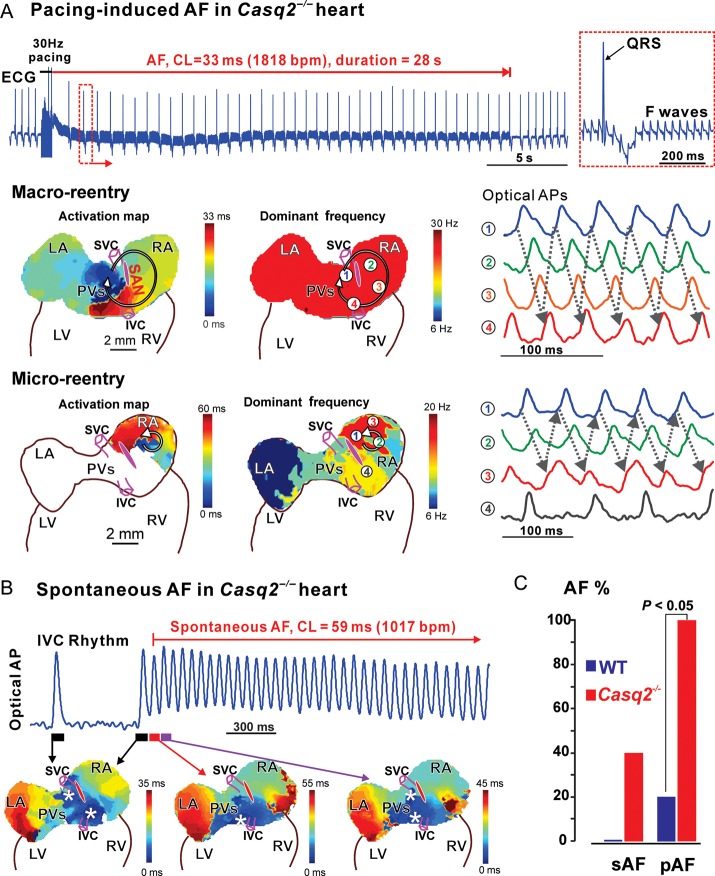

Loss of Calsequestrin 2 increases susceptibility to atrial fibrillation

Additionally, susceptibility to atrial fibrillation (AF) was tested in 10 whole heart experiments. Episodes of spontaneous- and rapid pacing-induced AF occurred only in the presence of 100 nM Iso + 3 µM ACh (Figure 8) when atrial repolarization was significantly shortened (AP duration at 80% of repolarization (APD80) at 10 Hz pacing, baseline vs. Iso + ACh: 40±7 ms vs. 26 ± 5 ms in control, P < 0.01; 51 ± 7 ms vs. 34 ± 8 ms in Casq2−/−, P < 0.05). Enhanced atrial latent pacemaker automaticity and conduction block led to spontaneous AF in 2/5 Casq2−/− mice (Figure 8B), following ACh treatment, which slowed down heart rate profoundly to 106 ± 14 bpm (n = 2) vs. 194 ± 71 bpm (n = 3, non-spontaneous AF). Rapid pacing-induced unidirectional conduction blocks in the SAN pacemaker complex/crista terminalis (CT) (Supplementary material online, Figure S18) and thus, provoked reentrant AF (see ECG in Figure 8A) in all 5/5 Casq2−/− mice (vs. 1/5 in WT). AF lasted significantly longer in the Casq2−/− mice compared with WT [31±17 s (n = 5) vs. 7 s (n = 1), averaged value from three longest AF per each heart). Reentry around the SAN pacemaker complex was the main AF mechanism (Figure 8B–C) in three Casq2−/− mice. In two Casq2−/− mice, AF was maintained by micro-reentries (1–2 mm in diameter) in right atria (Figure 8A).

Figure 8.

Increased susceptibility to atrial flutter/fibrillation (AF) in Casq2−/− hearts. (A) Rapid-pacing induced atrial fibrillation in Casq2−/− hearts under isoproterenol and acetylcholine treatment. The pseudo-electrocardiogram showed that rapid pacing at 30 Hz induced atrial fibrillation which lasted for 28 s. The regular fibrillatory (F) waves indicating atrial flutter is zoomed in on the right. Both macro- and micro-reentry were drivers for the atrial fibrillation in Casq2−/− hearts. The reentrant circuits are shown in the activation maps on the left; maps in the middle show the dominant frequency (or the reciprocal of the averaged CL) at various locations. During macro-reentry, dominant frequency was uniform. In contrast, during micro-reentry, dominant frequency was locally higher in the micro-reentry circuit area. On the right are the sample optical action potentials, whose locations were marked by numbers in the frequency maps. Abbreviations are the same as those in Figure 1. (B) Spontaneous atrial fibrillation occurred under isoproterenol and acetylcholine treatment. As shown in optical action potentials and activation maps, the heart was under slow stable inferior vena cava rhythm, and then one of the inferior vena cava beats triggered a rapid burst of atrial activity. Representative optical action potential trace from the inferior vena cava region is shown. (C) Percentage of animals with atrial fibrillation inducibility in the control and Casq2−/− groups (sAF—spontaneous AF; pAF—pacing-induced AF).

Discussion

Calsequestrin 2 is essential for normal sinoatrial node function and structural integrity

Bradycardia is observed in CPVT patients emphasizing SAN dysfunction as a primary manifestation of familial CPVT caused by either Casq2 or RyR2 mutations, which can also explain the increased incidence of atrial arrhythmias associated with CPVT.5,6,8 In the present study, we show for the first time that CASQ2 plays an important role in heart rate regulation and alterations in the protein's expression can cause SAN dysfunction and bradycardia.

Importantly, we report the presence of enhanced degenerative fibrosis exclusively within the atrial pacemaker complex in 3-month Casq2−/− mice (Figure 4). Our novel data suggest that the enhanced fibrotic remodelling within the SAN could be involved in human CPVT hearts as well, which may not be apparent from whole heart functional tests. Interestingly, although whole heart function is not altered at 3 months of age, older Casq2−/− mice show a trend towards decreased cardiac function (Supplementary material online, Table S1). Based on the role of CASQ2 as a Ca2+ buffering protein and regulator of RyR2 channel activity, it is possible that structural remodelling, including fibrosis of the SAN complex in CASQ2-deficient hearts, could be attributable to abnormal Ca2+ handling in the pacemaker cells.17 Isolated Casq2−/− SAN cells indeed showed abnormalities in several Ca2+ cycling parameters, including increases in Ca2+ spark and wave frequencies, decreased Ca2+ transient amplitude, and slowed clearance of diastolic Ca2+ (Figure 6). Enhanced diastolic Ca2+ could directly lead to increased fibrosis within the SAN complex as well as in the latent pacemaker areas by favouring downstream activation of apoptosis due to cytosolic Ca2+ overload. In fact, a previous study suggests that chronic Ca2+ leak from the SR can directly stimulate cell damage and fibrogenesis.20 Increased intracellular [Ca2+] could also stimulate activation of the multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II, which in turn promotes myocardial dysfunction and heart failure,21 SAN cell apoptosis, increased fibrosis, and alternating brady/tachy arrhythmias.17 Thus, we propose that the selective degenerative fibrosis of the SAN pacemaker complex in Casq2−/− mice (Figure 4) could partially be due to increased diastolic Ca2+ leak observed in the pacemaker cells (Figure 6). Additionally, ventricular tachyarrhythmias (CPVT) in this model by themselves could induce remodelling leading to decrease in cardiac function. We suggest that ageing human CPVT hearts could also be subject to structural remodelling, and that progressive fibrogenesis within the atrial pacemaker complex should be considered as a possible factor in CPVT aetiology.

Loss of Calsequestrin 2 leads to multiple competing pacemaker clusters due to abnormal Ca2+ leak and fibrosis in the sinoatrial node complex

The SAN pacemaker complex is a heterogeneous structure, consisting of multiple compartments with naturally occurring fibrosis which provides insulation from the atrial myocardium22–24 and maintains a delicate balance between depolarized cells (source) and the resting tissue ahead (sink).25 Sinoatrial node structural remodelling (fibrosis) creates a source–sink mismatch, which could underlie abnormal impulse propagation within the SAN. Enhanced fibrosis observed in both 3-month and 12-month Casq2−/− mice, can suppress pacemaker activity within the SAN and also provide effective insulation around the latent pacemakers, thereby creating new functional pacemaker clusters (IAS region) (Figures 1, 2, 4, and 5; Supplementary material online, Figure S3). During autonomic stimulation, these regions could become more active and compete with the compromised leading pacemaker, thereby causing the observed beat-to-beat variations in optical APs and heart rate (Figure 2). We also suggest that the SAN and latent atrial pacemaker cells are differently regulated by the Ca2+ clock and hence changes in intracellular Ca2+ cycling due to loss of CASQ2 would affect these cells differently. This could be another reason why SAN activity is depressed while latent pacemakers are unmasked and compete with the SAN.

Loss of Calsequestrin 2 is associated with increased incidence of reentrant atrial fibrillation

We found that autonomic stimulation could promote spontaneous AF registered in isolated 12-month Casq2−/− hearts. While reentry has not been previously demonstrated in the CPVT model, it has been recently suggested as a plausible mechanism26 based on the finding that atrial conduction is significantly slowed in a RyR2-p2328s gain-of-function mutation mouse model.27,28 Similarly, we observed a significant conduction slowing and unidirectional conduction blocks in the Casq2−/− preparations during atrial pacing, occurring primarily in the SAN pacemaker complex region, which was also characterized by increased fibrosis (Figure 4). This conduction block area plays a critical role in the initiation and maintenance of AF since macro-reentry primarily circulated around the SAN pacemaker complex and micro-reentry bordered the same area with increased fibrosis (Figure 8A and Supplementary material online, Figure S18), similar to the formation of micro-reentry observed in the canine SAN.29 We also found atrial enlargement (hypertrophy) in this CPVT model, which can predispose the heart to AF.30 It should be noted that only a simultaneous treatment with ACh and Iso allowed AF induction, similar to our previous findings in the canine heart in vivo31 and in vitro.32 Spontaneous AFs (Figure 8B) arose primarily due to competition of multiple pacemakers (foci) and were maintained as focal arrhythmias. However, due to limited number of observations (two hearts out of five tested), further studies are required to determine whether these focal arrhythmias are due to abnormal automaticity, triggered arrhythmias, or ‘hidden’ micro-reentrant circuits.33

Loss of Calsequestrin 2 depresses sinoatrial node activity through altered sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ cycling

An important feature of Casq2−/− SAN cells was the presence of pronounced pauses between runs of spontaneous Ca2+ transients: periods of rapid Ca2+ oscillations from an elevated baseline Ca2+ were followed by periods of quiescence during which the elevated baseline returned to the normal level. These alterations in normal rhythmic activity in Casq2−/− SAN cells were paralleled by increased diastolic Ca2+ release in the form of Ca2+ sparks (Figure 6). Inhibition of pacemaker activity in SAN associated with pauses in Ca2+ transients was shown in a mutant mouse model of RyR2 (R4496C) dysfunction by Neco et al.6 Our and Neco et al.'s6 findings suggest that unstable SAN rhythm, in the context of CPVT pathology, arises primarily at the level of Ca2+-dependent alteration in rhythmic activity of individual SAN cells.

We further propose that the observed pauses in between rhythmic Ca2+ transients in Casq2−/− SAN cells are caused by excessive diastolic SR Ca2+ release in turn resulting in (i) inhibition of the SAN upstroke ICa,L current from partially inactivated L-type Ca2+ channels, and/or (ii) decrease in the SR Ca2+ content below a threshold level required for the generation of spontaneous SR Ca2+ releases. Earlier studies using caffeine and high extracellular Ca2+ have demonstrated that these two potential mechanisms can induce irregular pauses during spontaneous activity in SAN cells.34 Furthermore, we cannot exclude the role of ionic currents, such as INCX, If34 and IK currents since APD80% was prolonged in Casq2−/− mice which could additionally contribute to the observed pauses.

Additionally, we found that the Ca2+ cycling dysfunction occurs not only at the SAN cell level but is globally manifested throughout the atrial pacemaker complex as a delay between the upstroke of AP-Ca2+ transient (Figure 7). Despite the complex nature of voltage- and Ca2+-driven mechanisms, our data strongly suggest that SR Ca2+ cycling could be the primary defect in causing the slowed and increasingly variable heart rates in CPVT patients. Interestingly, Faggioni et al. recently demonstrated that ectopic beats occur more frequently in the Casq2−/− ventricle when the basal heart rate is relatively slow, and that these ventricular arrhythmias disappear when the basal rate is increased by artificial pacing or by administration of atropine.35 Thus, we hypothesize that the inadequately slow heart rate, especially during adrenergic stress, is unable to effectively suppress triggered activity, leading to ventricular arrhythmias as well as structural and functional remodelling.

Limitations

There are several limitations to our study: First, we did not quantify the contribution of the pacemaker If current, as well as other pacemaker ion currents (including INCX) contributing to the ‘membrane clock,’ which could be altered in Casq2−/− mice. Based on the hypothesis that SAN automaticity is mutually regulated by the surface membrane voltage clock and intracellular calcium clock,12,13 we predict parallel alterations in the ion currents in response to the altered Ca2+ cycling in this model. Furthermore, protein expression of Ca2+ cycling and membrane ion channels should be quantified to support functional alterations. Results from our integrated approach imply that such functional (ion current measurements) and molecular (protein expression) assays should be done in a compartment-specific manner (e.g. superior and inferior SAN, IVC, septum) to determine the bases of the functional differences that we found in these compartments due to the loss of CASQ2.

Future directions

We suggest that the SAN myocytes could be more susceptible to Ca2+ overload-driven cell death than the latent atrial pacemakers, thereby leading to the specific increase in fibrosis within the SAN. As such, restoration of adequate heart rhythm strategies targeted to eliminate degenerative fibrosis and to improve SAN function could potentially offer better prevention from fatal arrhythmias, such as CPVT and AF. Fixing the RyR2-mediated Ca2+ leak could be a therapeutic strategy not only to prevent triggered pro-arrhythmic activity but also to treat fibrosis, a prominent factor in AF induction and maintenance. Our future studies will have to focus on determining the mechanisms involved in fibrotic remodelling, which could be a critical factor in the progression of CPVT.

Conclusion

Loss of CASQ2 causes abnormal SR Ca2+ release and selective interstitial fibrosis in the atrial pacemaker complex, which disrupts SAN pacemaking and enhances atrial ectopy. These functional and structural alterations could form a substrate for the observed tachy-brady arrhythmias in CPVT patients. Our data clearly indicate that RyR2-mediated Ca2+ leak causes not only ventricular arrhythmias but also atrial brady- and tachyarrhythmias in CPVT and potentially in AF patients, by more than one mechanism.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal online.

Funding

This work was primarily supported by Dorothy M. Davis Heart and Lung Research Institute startup funding and NIH R01HL115580 (to V.V.F.), and in part by the NIH (HL074045 and HL063043 to S.G.), (HL084583, HL083422 to P.J.M.), (HL080551 to M.P.) (HL88635 to B.C.K.); by the AHA Established Investigator Award (to P.J.M.) and by the AHA Post-doctoral fellowship (to A.K.).

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr Hsiang-Ting Ho for generous assistance with data analyses and Mr Jedidiah Snyder for helping with isolation of SAN myocytes.

References

- 1.Priori SG, Napolitano C, Memmi M, Colombi B, Drago F, Gasparini M, DeSimone L, Coltorti F, Bloise R, Keegan R, Cruz Filho FE, Vignati G, Benatar A, DeLogu A. Clinical and molecular characterization of patients with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2002;106:69–74. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000020013.73106.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lahat H, Pras E, Olender T, Avidan N, Ben-Asher E, Man O, Levy-Nissenbaum E, Khoury A, Lorber A, Goldman B, Lancet D, Eldar M. A missense mutation in a highly conserved region of Casq2 is associated with autosomal recessive catecholamine-induced polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in bedouin families from israel. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:1378–1384. doi: 10.1086/324565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Priori SG, Napolitano C, Tiso N, Memmi M, Vignati G, Bloise R, Sorrentino V, Danieli GA. Mutations in the cardiac ryanodine receptor gene (hRyR2) underlie catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2001;103:196–200. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faggioni M, Knollmann BC. Calsequestrin 2 and arrhythmias. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H1250–H1260. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00779.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhuiyan ZA, van den Berg MP, van Tintelen JP, Bink-Boelkens MT, Wiesfeld AC, Alders M, Postma AV, van Langen I, Mannens MM, Wilde AA. Expanding spectrum of human RyR2-related disease: New electrocardiographic, structural, and genetic features. Circulation. 2007;116:1569–1576. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.711606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neco P, Torrente AG, Mesirca P, Zorio E, Liu N, Priori SG, Napolitano C, Richard S, Benitah JP, Mangoni ME, Gomez AM. Paradoxical effect of increased diastolic Ca2+ release and decreased sinoatrial node activity in a mouse model of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2012;126:392–401. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.075382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Postma AV, Denjoy I, Hoorntje TM, Lupoglazoff JM, Da Costa A, Sebillon P, Mannens MM, Wilde AA, Guicheney P. Absence of calsequestrin 2 causes severe forms of catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circ Res. 2002;91:e21–e26. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000038886.18992.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sumitomo N, Sakurada H, Taniguchi K, Matsumura M, Abe O, Miyashita M, Kanamaru H, Karasawa K, Ayusawa M, Fukamizu S, Nagaoka I, Horie M, Harada K, Hiraoka M. Association of atrial arrhythmia and sinus node dysfunction in patients with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circ J. 2007;71:1606–1609. doi: 10.1253/circj.71.1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knollmann BC, Chopra N, Hlaing T, Akin B, Yang T, Ettensohn K, Knollmann BE, Horton KD, Weissman NJ, Holinstat I, Zhang W, Roden DM, Jones LR, Franzini-Armstrong C, Pfeifer K. Casq2 deletion causes sarcoplasmic reticulum volume increase, premature Ca2+ release, and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2510–2520. doi: 10.1172/JCI29128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bogdanov KY, Vinogradova TM, Lakatta EG. Sinoatrial nodal cell ryanodine receptor and Na+-Ca2+ exchanger: Molecular partners in pacemaker regulation. Circ Res. 2001;88:1254–1258. doi: 10.1161/hh1201.092095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verkerk AO, Wilders R, van Borren MM, Peters RJ, Broekhuis E, Lam K, Coronel R, de Bakker JM, Tan HL. Pacemaker current If in the human sinoatrial node. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2472–2478. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lakatta EG, DiFrancesco D. What keeps us ticking: A funny current, a calcium clock, or both? J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;47:157–170. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lakatta EG, Maltsev VA, Vinogradova TM. A coupled system of intracellular Ca2+ clocks and surface membrane voltage clocks controls the timekeeping mechanism of the heart's pacemaker. Circ Res. 2010;106:659–673. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.206078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalyanasundaram A, Lacombe VA, Belevych AE, Brunello L, Carnes CA, Janssen PM, Knollmann BC, Periasamy M, Gyorke S. Up-regulation of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ uptake leads to cardiac hypertrophy, contractile dysfunction and early mortality in mice deficient in Casq2. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;98:297–306. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalyanasundaram A, Viatchenko-Karpinski S, Belevych AE, Lacombe VA, Hwang HS, Knollmann BC, Gyorke S, Periasamy M. Functional consequences of stably expressing a mutant calsequestrin (Casq2d307h) in the Casq2 null background. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H253–H261. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00578.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glukhov AV, Fedorov VV, Anderson ME, Mohler PJ, Efimov IR. Functional anatomy of the murine sinus node: high-resolution optical mapping of ankyrin-b heterozygous mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299:H482–H491. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00756.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swaminathan PD, Purohit A, Soni S, Voigt N, Singh MV, Glukhov AV, Gao Z, He BJ, Luczak ED, Joiner ML, Kutschke W, Yang J, Donahue JK, Weiss RM, Grumbach IM, Ogawa M, Chen PS, Efimov I, Dobrev D, Mohler PJ, Hund TJ, Anderson ME. Oxidized CaMKII causes cardiac sinus node dysfunction in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3277–3288. doi: 10.1172/JCI57833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glukhov AV, Flagg TP, Fedorov VV, Efimov IR, Nichols CG. Differential KATP channel pharmacology in intact mouse heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rysevaite K, Saburkina I, Pauziene N, Vaitkevicius R, Noujaim SF, Jalife J, Pauza DH. Immunohistochemical characterization of the intrinsic cardiac neural plexus in whole-mount mouse heart preparations. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:731–738. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fauconnier J, Meli AC, Thireau J, Roberge S, Shan J, Sassi Y, Reiken SR, Rauzier JM, Marchand A, Chauvier D, Cassan C, Crozier C, Bideaux P, Lompre AM, Jacotot E, Marks AR, Lacampagne A. Ryanodine receptor leak mediated by caspase-8 activation leads to left ventricular injury after myocardial ischemia-reperfusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:13258–13263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100286108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erickson JR, Joiner ML, Guan X, Kutschke W, Yang J, Oddis CV, Bartlett RK, Lowe JS, O'Donnell SE, Aykin-Burns N, Zimmerman MC, Zimmerman K, Ham AJ, Weiss RM, Spitz DR, Shea MA, Colbran RJ, Mohler PJ, Anderson ME. A dynamic pathway for calcium-independent activation of CaMKII by methionine oxidation. Cell. 2008;133:462–474. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fedorov VV, Glukhov AV, Chang R, Kostecki G, Aferol H, Hucker WJ, Wuskell JP, Loew LM, Schuessler RB, Moazami N, Efimov IR. Optical mapping of the isolated coronary-perfused human sinus node. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1386–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fedorov VV, Glukhov AV, Chang R. Conduction barriers and pathways of the sinoatrial pacemaker complex: their role in normal rhythm and atrial arrhythmias. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H1773–H1783. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00892.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chandler NJ, Greener ID, Tellez JO, Inada S, Musa H, Molenaar P, Difrancesco D, Baruscotti M, Longhi R, Anderson RH, Billeter R, Sharma V, Sigg DC, Boyett MR, Dobrzynski H. Molecular architecture of the human sinus node: Insights into the function of the cardiac pacemaker. Circulation. 2009;119:1562–1575. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.804369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joyner RW, van Capelle FJ. Propagation through electrically coupled cells. How a small SA node drives a large atrium. Biophys J. 1986;50:1157–1164. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(86)83559-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heijman J, Wehrens XH, Dobrev D. Atrial arrhythmogenesis in catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia—is there a mechanistic link between sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leak and re-entry? Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2013;207:208–211. doi: 10.1111/apha.12038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.King JH, Wickramarachchi C, Kua K, Du Y, Jeevaratnam K, Matthews HR, Grace AA, Huang CL, Fraser JA. Loss of Nav1.5 expression and function in murine atria containing the RyR2-p2328s gain-of-function mutation. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;99:751–759. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.King JH, Zhang Y, Lei M, Grace AA, Huang CL, Fraser JA. Atrial arrhythmia, triggering events and conduction abnormalities in isolated murine RyR2-p2328s hearts. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2013;207:308–323. doi: 10.1111/apha.12006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glukhov AV, Hage LT, Hansen BJ, Pedraza-Toscano A, Vargas-Pinto P, Hamlin RL, Weiss R, Carnes CA, Billman GE, Fedorov VV. Sinoatrial node reentry in a canine chronic left ventricular infarct model: The role of intranodal fibrosis and heterogeneity of refractoriness. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6:984–994. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.113.000404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Byrd GD, Prasad SM, Ripplinger CM, Cassilly TR, Schuessler RB, Boineau JP, Damiano RJ., Jr Importance of geometry and refractory period in sustaining atrial fibrillation: Testing the critical mass hypothesis. Circulation. 2005;112:I7–13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.526210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharifov OF, Fedorov VV, Beloshapko GG, Glukhov AV, Yushmanova AV, Rosenshtraukh LV. Roles of adrenergic and cholinergic stimulation in spontaneous atrial fibrillation in dogs. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:483–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fedorov VV, Chang R, Glukhov AV, Kostecki G, Janks D, Schuessler RB, Efimov IR. Complex interactions between the sinoatrial node and atrium during reentrant arrhythmias in the canine heart. Circulation. 2010;122:782–789. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.935288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lou Q, Glukhov AV, Hansen B, Hage L, Vargas-Pinto P, Billman GE, Carnes CA, Fedorov VV. Tachy-brady arrhythmias: the critical role of adenosine-induced sinoatrial conduction block in post-tachycardia pauses. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Satoh H. Caffeine depression of spontaneous activity in rabbit sino-atrial node cells. Gen pharmacol. 1993;24:555–563. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(93)90212-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faggioni M, Hwang HS, van der Werf C, Nederend I, Kannankeril PJ, Wilde AA, Knollmann BC. Accelerated sinus rhythm prevents catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in mice and in patients. Circ Res. 2013;112:689–697. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.300076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]