Abstract

We describe baseline incidence and risk-factors for new cancers in 4161 persons receiving autotransplants for multiple myeloma (MM) in the US during 1990- 2010. Observed incidence of invasive new cancers was compared with expected incidence relative to the US population. The cohort represented 13387 person years at-risk. 163 new cancers were observed for a crude incidence rate of 1.2 new cancers per 100 person-years and cumulative incidences of 2.6% (95% CI; 2.09-3.17), 4.2% (95% CI; 3.49-5.00) and 6.1% (95% CI; 5.08-7.24) at 3, 5 and 7 years. The incidence of new cancers in the autotransplant cohort was similar to age- race- and gender-adjusted comparison subjects with an observed/expected (O/E) ratio of 1.00 (99% CI; 0.81-1.22). However, acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and melanoma were observed at higher than expected rates with O/E ratios of 5.19 (99% CI; 1.67–12.04; P=0.0004), and 3.58 (99% CI, 1.82–6.29; P<0.0001). Obesity, older age and male gender were associated with increased risks of new cancers in multivariate analyses. This large dataset provides a baseline for comparison and defines the histologic type specific risk for new cancers in patients with MM receiving post autotransplant therapies such as maintenance.

Keywords: Myeloma, Second Cancer, Transplantation

Introduction

Survival of persons with multiple myeloma (MM) has improved substantially because of new therapies including autotransplants and novel drugs such as immune-modulating drugs and proteasome-inhibitors. Consequently, it is important to determine whether there is an increased risk of new cancers either because of the disease or its therapy. Several, but not all studies report an increased risk of new cancers including acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) in persons with myeloma whether or not they receive autologous transplants1-5.

Recent data from randomized trials of lenalidomide given post-autotransplant as maintenance therapy to prevent relapse indicate an increased risk of new cancers. Twenty six of 307 in one study and 18 of 231 subjects in a second developed new cancers with significant higher incidence in subjects randomized to lenalidomide compared with those receiving placebo6,7. A recent meta-analysis reported a higher risk for new hematologic cancers in persons receiving lenalidomide and melphalan8.

The purpose of our study was to determine the baseline incidence of new cancers after autologous transplants in persons with MM in the US and to compare this rate with those of a age, gender and race matched US population. We also wanted to identify factors associated with development of new cancers post-autotransplant using statistical models.

Methods

Subjects

Subjects receiving a first autotransplant within 18 months of diagnosis in the US for MM and reported to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) 1990- 2010 were included in the study. The CIBMTR is a voluntary group of more than 450 transplant centers worldwide that contribute data on allogeneic and autologous transplants to a statistical center at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee or the National Marrow Donor Program Coordinating Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Participating centers are required to register all transplants done consecutively and post-transplant outcomes including incidence of new cancer are collected in prospective fashion. Compliance of the participating centers is monitored by periodic on-site audits. Subjects are followed up longitudinally, with yearly data update. Computerized checks for errors, physicians' review of submitted data, and on-site audits of participating centers are used to ensure data quality. Observational studies conducted by the CIBMTR are performed with a waiver of informed consent and in compliance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations as determined by the institutional review board and the privacy officer of the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Definition of Outcomes

A new cancer was defined as a previously unidentified invasive cancer occurring post-transplant. Carcinomas in situ and other pre-cancerous abnormalities (e.g. squamous intraepithelial neoplasia) were excluded. Pathology reports were obtained and reviewed centrally to confirm the diagnosis. Transplant centers were contacted to resolve ambiguities. After confirmation, diagnoses of new cancers were coded by ICD-O-3 for comparison with the US National Cancer Institute's Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program SEER9. SEER consists of high-quality, population-based cancer registries that are supported and sponsored by the National Cancer Institute. The SEER Program is the authoritative source on invasive cancer incidence and survival in the US.

Statistical Analyses

Summary statistics were used to describe the cohort. For each transplant recipient, person-years at risk were calculated from date of transplant until the date of last contact, death or diagnosis of a new cancer, whichever occurred first. Time to diagnosis of new cancer from transplant was determined. Cumulative incidence of new cancers was computed at various time points by treating death as a competing risk. Recurrence or progression of MM was not considered a competing risk.

Age-, gender-, and race-specific cancer incidence rates derived from SEER for all cancers combined and for cancers at specific sites were applied to the appropriate person-years at-risk to compute the expected numbers of cancers. Observed/expected (O/E) ratios or standardized incidence ratios (SIRs) with 99% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated on the assumption that the observed number of cancers followed a Poisson distribution. Specific O/E ratios were not derived for non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSC) and for MDS because non-melanoma skin cancers are not collected by SEER and MDS was not reportable to SEER until 2001. Also there is ongoing concern that MDS may be under reported to SEER10. However the overall incidence estimates and multivariate analyses include all cancers confirmed in our study cohort.

Cox regression models were used to compare risks for various subgroups of transplant recipients and to identify risk factors for all new cancers and for AML and MDS (AML/MDS) separately. Variables analyzed in the Cox model were: age at transplant, gender, race, smoking history, Karnofsky performance score (KPS) at transplant, body mass index (BMI), number of lines and types of pretransplant therapy, pretransplant radiation, conditioning regimen, whether a second autotransplant was done, post-transplant maintenance therapy and the year of transplant.

In addition, a matched case–control analysis was done comparing autotransplant recipients who developed a new cancer (N=163) matched to a cohort of transplant recipients with similar follow-up who did not develop a new cancer. Controls were matched for gender, year of transplant (+/- 3 years of cases), age (+/-3 years) and follow-up interval (< 1 year, 1-2 years, 3-5 years). Controls were selected to ensure post-transplant follow-up time was similar and ≥time to development of new cancer in the cases with the new cancer. Seven hundred and seventy six controls were generated from the database for the 163 new cancer cases. Separate multivariate analyses were then done to identify variables associated with development of all new cancers and of AML/MDS. Variables analyzed by conditional logistic regression included KPS, BMI, smoking history, pretransplant therapy, radiation therapy pre-transplant and transplant conditioning regimen.

Results

Subjects

There were 4161 MM subjects from 164 US transplant centers contributing 13387 person-years follow-up (median, 2.5 years, range, 0.3 months-16 years). Median post-transplant survival was 63 months (95% CI; 60-67 months), with 70% (95% CI; 68-72%), 52% (95% CI; 50-54%) and 29% (95% CI; 26-31%) of subjects alive at 3, 5 and 10 years. Subject-, disease- and treatment-related variables are summarized and described in Table 1. Median age at transplant was 57 years (22-80 years) with only 6% of subjects >70 years. High-dose melphalan as a single agent was the most common (81%) conditioning regimen. As expected for a cohort spanning 1990-2010, novel MM drugs were used pre-transplant in 69% of subjects including thalidomide in 34%, lenalidomide in 14% and bortezomib in 21%. Post-transplant maintenance therapy included thalidomide (15%), lenalidomide (11%), bortezomib (9%) and interferon (6%). Most subjects (59%) were transplanted within 6-12 months of diagnosis, 27% within 6 months and 14% between 12 and 18 months after diagnosis. Follow up completeness index11 for the study was more than 80%.

Table 1. Patient, Disease and Treatment Characteristics.

| Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Subject-related | |

| N subjects | 4161 |

| Number of centers | 164 |

| Age at transplant, median (range), years | 57 (22-80) |

| < 40 years | 163 (4) |

| 40-49 years | 731(18) |

| 50-59 years | 1611 (39) |

| 60-69 years | 1427(34) |

| ≥ 70 years | 229 (6) |

| Male | 2437 (59) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 3159 (76) |

| African-American | 691 (17) |

| Hispanic | 172 (4) |

| Othersa | 78 (2) |

| Missing | 61 (1) |

| Karnofsky score < 90 | 1530 (37) |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | |

| Underweight (<18.5) | 39 (1) |

| Normal weight (18.5-25) | 1045 (25) |

| Overweight (25-29.9) | 1607 (39) |

| Obesity (≥30) | 1449 (35) |

| Missing | 21 (<1) |

| History of smoking before transplant | 1821 (44) |

| Disease-related | |

| Stage III by Durie Salmon/International Stage | 2163 (52) |

| Immunochemical subtype of MM | |

| IgG | 2215 (53) |

| IgA | 803 (19) |

| Light chain | 730 (18) |

| Othersa | 51 (1) |

| Non-secretory | 177 (4) |

| Missing | 185 (4) |

| Albumin at diagnosis | |

| <3.5 g/dL | 1290 (31) |

| Creatinine at diagnosis >1.5 mg/dl | 959 (23) |

| Hemoglobin at diagnosis <10 g/dl | 2426 (58) |

| Treatment Characteristics | |

| Conditioning regimens | |

| Melphalan alone | 3388 (81) |

| Melphalan + TBI | 206 (5) |

| Melphalan + others (no TBI) | 245 (6) |

| Busulfan + Cyclophosphamide ± others | 231 (6) |

| Othersc | 91 (2) |

| Lines of chemotherapy pre transplant | |

| 1 | 2568 (62) |

| 2 | 1145 (28) |

| >2 | 419 (10) |

| Missing | 29(<1) |

| Pre-transplant radiation therapy | 1029 (26) |

| Chemotherapy prior to transplant | |

| Method I of description | |

| VAD/High dose steroids: Yes | 1684 (44) |

| Thalidomide: Yes | 1428(34) |

| Bortezomib: Yes | 880(21) |

| Lenalidomide: Yes | 565 (14) |

| Thalidomide + bortezomib: Yes | 321 (8) |

| Bortezomib + Lenalidomide: Yes | 393 (9) |

| Melphalan + Prednisone (MP): Yes | 266 (6) |

| Missing | 29 (<1) |

| Method II of description | |

| Thalidomide/lenalidomide + bortezomib | 619 (15) |

| Thalidomide/lenalidomide | 1288 (31) |

| Bortezomib | 261 (6) |

| VAD/high dose steroids | 1450 (35) |

| Melphalan + Prednisone (MP) | 127 (3) |

| Others | 387 (9) |

| Missing | 29 (<1) |

| Sensitive to pretransplant chemotherapy | 3425 (78) |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant, median (range), months | 7 (<1-18) |

| <6 months | 1123 (27) |

| 6-12 months | 2475 (59) |

| 12-18 months | 563 (14) |

| Transplant group | |

| Single autotransplant | 3196 (77) |

| ≥ 2 transplant, time interval between transplants <6 months | 615 (15) |

| ≥ 2 transplant, time interval between transplants ≥6 months | 350 (8) |

| Conditioning regimens | |

| Melphalan alone | 3388 (81) |

| Melphalan + TBI | 206 (5) |

| Melphalan + others (no TBI) | 245 (6) |

| Busulfan + cyclophosphamide ± others | 231 (6) |

| Othersc | 91 (2) |

| Year of transplant | |

| 1990-1995 | 132 (3) |

| 1996-1997 | 295 (7) |

| 1998-1999 | 367 (9) |

| 2000-2001 | 485 (12) |

| 2002-2003 | 438 (11) |

| 2004-2005 | 814 (20) |

| 2006-2007 | 651 (16) |

| 2008-2009 | 808 (19) |

| 2010 | 171 (4) |

| Planned maintenance therapy | |

| None | 2333 (56) |

| Thalidomide | 623 (15) |

| Bortezomib | 383 (9) |

| Lenalidomide | 450 (11) |

| Steroid | 180 (4) |

| Interferon | 234 (6) |

| Othersd | 160 (4) |

| Missing | 24 (<1) |

| Follow Up completeness Index @ 1 year & 5 years | 97% & 82% |

Abbreviations: VAD – Vincristine, Doxorubicin, Dexamethasone; SD – Stable Disease, TBI – Total body irradiation

Other race includes: Asian/Pacific islander (n=47), Native American (n=10), Middle Eastern White (n=7)

Other immunochemical type include: IgD (n=31), IgE (n=3), IgM (n=8)

Other conditioning regimens include: cyclophosphamide (n=12), cyclophosphamide+etopside (n=17), TBI (n=2), cyclophosphamide+taxol (n=1), cyclophosphamide+thiotepa(n=2), TBI+cyclophosphamide(n=29), TBI+Thiotepa (n=9), TBI+busulfan(n=3), TBI+etoposide(n=1), busulfan (n=5), busulfan+cytarabine+etoposide(n=1), busulfan+thiotepa (n=1), carboplatin+thiotepa (n=2).

Other maintenance therapy includes: rituxan (n=3), VP16 (n=2), IVIG (n=60), cyclophosphamide (N=26), doxil (n=2), biaxin (n=7), decadron (n=74), melphalan (n=18), taxol (n=13), cisp (n=10), etoposide (n=4), IL2 (n=26)

New cancers

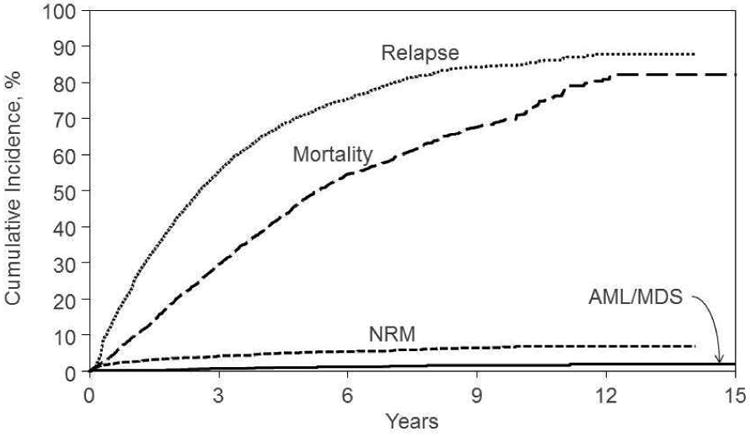

One hundred sixty three new cancers were reported in autotransplant recipients with a crude incidence rate of 1.2 (95% CI; 1.03-1.42) new cancers per 100 person-years follow-up. The observed/expected (O/E) ratio was 1.00 (99% CI, 0.81-1.22) as compared with the general population of the US (Table 2). There were 8 cases of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), 27 of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and 19 of melanoma observed during follow-up. Cumulative incidence of new cancers was 2.6% (95% CI, 2.09–3.17%) at 3 years and 5.09% (95% CI, 4.96– 7.23%) at 7 years [Figure 1, Table 3]. Cumulative incidence of AML/MDS was 0.5% (95% CI, 0.28–0.78%) at 3 years and 1.51% (95% CI, 0.97– 2.16%) at 7 years. Significantly increased O/E ratios were observed for AML and melanoma compared with the US population [Table 4]. Out of the 163 patients with new cancers, 101 relapsed with MM and 71 out of those 101 relapses had occurred prior to the diagnosis of new cancer. For the patients (N=71) who relapsed prior to the diagnosis of SPC, median months from relapse to new cancer was 20 months. For the remaining patients (N=92) had a new cancer diagnosis without evidence of myeloma relapse at that time. Similarly for AML/MDS, 21 had myeloma relapse with 17 of these relapses occurring prior to the diagnosis of AML/MDS. All cases of AML were observed >2 years post-transplant.

Table 2. Ratio of observed to expected cases (O/E) of risk of new invasive cancer according to interval post-transplant.

| Time since transplant | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

| < 1 year | 1-2 year | 3-5 year | |||||||

| N subjects | 4161 | 3464 | 2578 | ||||||

| Person-years in risk | 3849 | 3003 | 4608 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| New Cancer Site and ICD-O Code | O | O/E | 99% CI | O | O/E | 99% CI | O | O/E | 99% CI |

|

| |||||||||

| Nasopharynx C11 | 1 | 22.33 | 0.11-165.91 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-147.26 | 1 | 17.48 | 0.09-129.85 |

| Esophagus C15 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-10.43 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-12.49 | 2 | 2.85 | 0.15-13.20 |

| Colon C18 | 2 | 0.71 | 0.04-3.30 | 2 | 0.84 | 0.04-3.88 | 2 | 0.50 | 0.03-2.31 |

| Rectum C19.20 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-3.95 | 1 | 0.90 | 0.004-6.66 | 1 | 0.54 | 0.003-4.04 |

| Liver C22 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-11.34 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-13.75 | 2 | 3.18 | 0.16-14.75 |

| Pancreas C25 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-5.89 | 2 | 2.63 | 0.14-12.20 | 1 | 0.79 | 0.004-5.84 |

| Trachea, bronchus, lung C33 | 2 | 0.31 | 0.02-1.43 | 2 | 0.36 | 0.02-1.68 | 7 | 0.76 | 0.22-1.85 |

| Other thoracic organs C37 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-168.71 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-207.75 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-129.04 |

| Melanoma C43 | 4 | 2.81 | 0.47-8.84 | 8 | 6.91 | 2.22-16.04 | 3 | 1.61 | 0.18-5.88 |

| Other skin C44 | 4 | N/A | 4 | N/A | 5 | N/A | |||

| Soft tissue C47 | 1 | 4.86 | 0.02-1.89 | 1 | 5.91 | 0.03-43.92 | 1 | 3.63 | 0.02-26.95 |

| Breast C50 | 2 | 0.41 | 0.02-1.89 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-1.31 | 5 | 0.78 | 0.17-2.21 |

| Uterus C55 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-277.49 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-336.64 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-211.21 |

| Ovary C56 | 2 | 3.98 | 0.21-18.44 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-12.72 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-7.89 |

| Prostate C61 | 3 | 0.30 | 0.03-1.10 | 9 | 1.07 | 0.37-2.37 | 6 | 0.43 | 0.11-1.11 |

| Kidney C64 | 1 | 0.89 | 0.004-6.62 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-5.73 | 4 | 2.66 | 0.45-8.37 |

| Renal pelvis C65 | 1 | 17.53 | 0.09-130.25 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-108.42 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-63.46 |

| Ureter C66 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-152.01 | 1 | 33.15 | 0.17-246.27 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-102.03 |

| Bladder C67 | 1 | 0.55 | 0.002-4.05 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-3.38 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-1.99 |

| Nervous system C70.72 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-11.42 | 1 | 2.63 | 0.01-19.59 | 1 | 1.63 | 0.01-14.37 |

| Thyroid C73 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-12.44 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-56.12 | 1 | 1.93 | 0.01-14.37 |

| Hodgkin disease C81 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-44.13 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-56.12 | 2 | 13.51 | 0.70-62.66 |

| Non-Hodgkin disease C82 | 1 | 0.67 | 0.003-4.97 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-4.27 | 2 | 0.98 | 0.05-4.54 |

| Lymphoid leukemia CC91 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-13.23 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-15.76 | 2 | 3.57 | 0.18-16.57 |

| AML | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-13.49 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-16.02 | 4 | 7.23 | 1.22-22.77 |

| MDS | 3 | N/A | 5 | N/A | 12 | N/A | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Overall | 27 | 0.64 | 0.37-1.03 | 35 | 0.99 | 0.61-1.51 | 61 | 1.05 | 0.73-1.45 |

|

| |||||||||

| Overall (excluding ‘skin’) | 23 | 0.55 | 0.30-0.92 | 31 | 0.88 | 0.53-1.38 | 56 | 0.96 | 0.66-1.35 |

|

| |||||||||

| Time since transplant | |||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

| 6-10 | 11-20 | Overall | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Number of patients | 820 | 110 | 4161 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Person-year in risk | 1769 | 158 | 13387 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Secondary Cancer Site ICD –O code | O | O/E | 99% CI | O | O/E | 99% CI | O | O/E | 99% CI |

|

| |||||||||

| Nasopharynx | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-238.08 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-2510.28 | 2 | 12.32 | 0.64-57.12 |

| Esophagus C15 | 1 | 3.39 | 0.02-25.18 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-180.73 | 3 | 1.53 | 0.17-5.60 |

| Colon C18 | 2 | 1.14 | 0.06-5.30 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-29.09 | 8 | 0.72 | 0.23-1.67 |

| Rectum C19.20 | 1 | 1.28 | 0.01-9.54 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-69.02 | 3 | 0.58 | 0.07-2.13 |

| Liver C22 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-20.77 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-209.09 | 2 | 1.14 | 0.06-5.26 |

| Pancreas C25 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-9.67 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-92.40 | 3 | 0.85 | 0.10-3.10 |

| Trachea, bronchus, lung C33 | 3 | 0.75 | 0.08-2.74 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-12.86 | 14 | 0.55 | 0.24-1.05 |

| Other thoracic organs C37 | 1 | 60.43 | 0.30-449.08 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-3318.32 | 1 | 8.61 | 0.04-63.98 |

| Melanoma C43 | 3 | 3.80 | 0.43-13.91 | 1 | 14.12 | 0.07-104.93 | 19 | 3.58 | 1.82-6.29 |

| Other skin C44 | 5 | N/A | 0 | N/A | 18 | N/A | |||

| Soft tissue C47 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-45.52 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-470.11 | 3 | 3.85 | 0.43-14.10 |

| Beast C50 | 3 | 1.12 | 0.13-4.12 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-19.38 | 10 | 0.55 | 0.20-1.17 |

| Uterus C55 | 1 | 97.29 | 0.49-722.91 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-4826.66 | 1 | 14.03 | 0.07-104.22 |

| Ovary C56 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-18.65 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-175.24 | 2 | 1.05 | 0.05-4.87 |

| Prostate C61 | 2 | 0.34 | 0.02-1.56 | 2 | 3.34 | 0.17-15.50 | 22 | 0.56 | 0.30-0.95 |

| Kidney C64 | 3 | 4.81 | 0.54-17.61 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-87.15 | 8 | 4.24 | 0.61-4.39 |

| Renal pelvis C65 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-142.68 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-1429.66 | 1 | 1.34 | 0.02-34.27 |

| Ureter C66 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-225.73 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-2218.64 | 1 | 7.00 | 0.04-52.02 |

| Bladder C67 | 1 | 0.84 | 0.004-6.21 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-46.09 | 2 | 0.27 | 0.01-1.26 |

| Nervous system C70.72 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-20.61 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-216.10 | 2 | 1.15 | 0.06-5.33 |

| Thyroid C73 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-25.97 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-276.57 | 1 | 0.67 | 0.003-4.94 |

| Hodgkin disease C81 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-91.85 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-1008.68 | 2 | 4.70 | 0.24-21.80 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma C82 | 0 | 1.15 | 0.01-8.56 | 1 | 11.79 | 0.06-87.61 | 4 | 0.87 | 0.22-2.45 |

| Lymphoid leukemia C91 | 1 | 4.11 | 0.02-30.54 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00-224.75 | 3 | 1.92 | 0.22-7.02 |

| AML | 2 | 8.28 | 0.43-38.41 | 2 | 83.14 | 4.30-385.50 | 8 | 5.19 | 1.67-12.04 |

| MDS | 6 | N/A | 1 | N/A | 27 | N/A | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Overall | 34 | 1.38 | 0.84-2.11 | 6 | 2.50 | 0.62-6.29 | 163 | 1.00 | 0.81-1.22 |

|

| |||||||||

| Overall (excluding ‘skin’) | 29 | 1.18 | 0.69-1.87 | 6 | 2.49 | 0.62-6.31 | 145 | 0.89 | 0.71-1.10 |

ICD-O refers to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology;

Specific O/E ratios for MDS and “other skin cancers” not calculated – see methods section.

Figure 1. Cumulative incidence of new cancers compared with incidence of myeloma relapse and risk of death.

Table 3. Cumulative incidence of new cancers.

| Using death as competing risk | ||

|---|---|---|

| N at risk | Probability (95% CI) | |

| Overall Secondary Cancer | ||

| @ 1 year | 3465 | 0.67 (0.44-0.95) |

| @ 3 year | 1808 | 2.60 (2.09-3.17) |

| @ 5 year | 823 | 4.21 (3.49-5.00) |

| @ 7 year | 384 | 6.11 (5.08-7.24) |

| @ 9 year | 179 | 7.48 (6.21-8.86) |

| MDS/AML | ||

| @ 1 year | 3465 | 0.07 (0.01-0.18) |

| @ 3 year | 1808 | 0.50 (0.28-0.78) |

| @ 5 year | 823 | 0.88 (0.56-1.27) |

| @ 7 year | 384 | 1.38 (0.89-1.98) |

| @ 9 year | 179 | 1.65 (1.06-2.37) |

Table 4. Observed/Expected ratios for selected new cancers.

| SECOND CANCERS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Person-Years at risk | 13387 | |||

| N | O/E Ratio | 99% CI | ||

| Trachea/Bronchus | 14 | 0.55 | 0.24 – 1.05 | |

| MDS | 27 | 85.52 | 48.48 - 138.97 | |

| AML | 8 | 5.19 | 1.67 - 12.04 | |

| Melanoma | 19 | 3.58 | 1.82 - 6.29 | |

| Breast | 10 | 0.55 | 0.20-1.17 | |

| Prostate | 22 | 0.56 | 0.30-0.95 | |

| Colon | 8 | 0.72 | 0.23-1.67 | |

Multivariate analyses

Risk factors for new cancer identified using Cox regression model included older age, obesity and male gender (Table 5). A higher risk of new cancer was observed in subjects aged 60-69 years compared with those <40 year old (hazard ratio [HR]=6.07 [95% CI, 1.48-24.78] ;P=0.012) and among those >70 years (HR=8.58; [95% CI,: 1.95-37.74], P=0.005). Obesity (BMI >30) was associated with higher risk of developing a new cancer (HR=1.93; 95% CI, 1.25-2.99; P=0.0030). Women had a significantly lower risk of new cancer as compared to men (HR=0.5; 95% CI, 0.35–0.71; P=0.001). Smoking, numbers of lines of prior therapy, radiation exposure for myeloma, melphalan dose (mg/m2), receiving a 2nd autotransplant and post-transplant use of thalidomide (15% of subjects) or lenalidomide (11% of subjects) were not significantly associated with the overall risk of developing a new cancer.

Table 5. Multivariate Analyses of Risk Factors for the development of Second Primary Malignancies among Autotransplant Recipients who developed a new cancer.

| Overall for Risk of developing any new cancer (n=4,129) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

| Female vs. male | 0.50 (0.35-0.71) | 0.0001 |

| Age group | Overall test P-value <0.0001 | |

| 40-49 vs. 18-39 | 1.62 (0.36-7.13) | 0.5240 |

| 50-59 vs. 18-39 | 3.03 (0.73-12.46) | 0.1240 |

| 60-69 vs. 18-39 | 6.07 (1.48-24.78) | 0.0120 |

| 70+ vs. 18-39 | 8.58 (1.95-37.74) | 0.0045 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | Overall test P-value =0.0048 | |

| Overweight vs. (underweight + normal) | 1.27 (0.81-1.98) | 0.2866 |

| Obesity | 1.93 (1.25-2.99) | 0.0030 |

| Risk of AML/MDS (n=3,977) | ||

| Parameter | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

| Age group | Overall test P-value = 0.0141 | |

| 50-59 vs. 40-49 | 3.76 (0.86-16.46) | 0.0785 |

| 60-69 vs. 40-49 | 3.95 (0.88-17.70) | 0.0730 |

| 70+ vs. 40-49 | 13.17 (2.52-68.86) | 0.0022 |

Multivariate analysis of AML/MDS was limited by the relatively small number of cases (N=33). After excluding subjects <40 years of age (only 1 case), multivariate analysis showed age >70 years was significantly associated with risk of AML/MDS (HR=13.17, 95% CI, 2.52-68.86, P=0.0022)

Case control analyses were done on age-, gender- and year of transplant-matched controls for the cases that reported a new cancer (Table 6) to analyze additional variables. BMI >30 remained significant in this analysis too with an odds ratio (OR) = 1.94 (95% CI, 1.15-3.26; P=0.005). Pre transplant therapies for MM, conditioning regimen (melphalan vs. other agents) and post-transplant maintenance were not significantly associated with increased risk of a new cancer; smoking history and receiving ≥2 lines of pretransplant therapy were of borderline significance.

Table 6. Matched Cohort Analysis: Multivariate Odds ratio of developing new cancer comparing those who developed a new cancer vs. matched cohort of autotransplant recipients who did not.

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Variable | N | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P |

|

| |||||

| KPS: 90-100 vs 0-80% | 456/280 | 1.37 (0.93-2.03) | 0.11 | ---- | >0.10 |

|

| |||||

| BMI: | |||||

| Normal | 172 | 1.00 | 0.004b | 1.00 | 0.020b |

| Overweight | 340 | 1.02 (0.63-1.66) | 0.94 | 1.22 (0.73-2.06) | 0.519 |

| Obesity | 254 | 1.85 (1.14-2.98) | 0.012 | 1.94 (1.15-3.26) | 0.005 |

|

| |||||

| Smoker: Yes vs No | 374/385 | 1.59 (1.10-2.29) | 0.013 | 1.45 (0.99-2.12) | 0.055 |

|

| |||||

| Lines of pre transplant therapy: >1 vs 1 | 284/485 | 1.20 (0.93-1.55) | 0.165 | 1.32 (0.99-1.74) | 0.053 |

|

| |||||

| Radiation: Yes vs No | 208/561 | 1.07 (0.72-1.59) | 0.739 | --- | >0.10 |

|

| |||||

| Thalidomide: Yes vs No | 230/539 | 0.74 (0.48-1.14) | 0.174 | --- | >0.10 |

|

| |||||

| Bortezomib: Yes vs No | 108/661 | 0.94 (0.48-1.82) | 0.845 | --- | >0.10 |

|

| |||||

| Lenalidomide: Yes vs No | 53/716 | 0.99 (0.47-2.11) | 0.985 | --- | >0.10 |

|

| |||||

| VAD: Yes vs No | 369/400 | 1.34 (0.89-2.01) | 0.158 | --- | >0.10 |

|

| |||||

| MP: Yes vs No | 71/698 | 0.66 (0.33-1.32) | 0.237 | --- | >0.10 |

|

| |||||

| Any Drug: Yes vs No | 672/97 | 0.68 (0.41-1.11) | 0.119 | --- | >0.10 |

|

| |||||

| Conditioning Regimen: | |||||

| Melphalan alone | 623 | 1.00 | 0.596c | --- | >0.10 |

| TBI used | 37 | 1.75 (0.74-4.14) | 0.205 | ||

| BU+CY | 44 | 0.93 (0.41-2.09) | 0.86 | ||

| Others | 72 | 0.96 (0.50-1.85) | 0.9079 | ||

Thalidomide and Lenalidomide were not included in the model for fitting “Any Drug” effect.

2d.f. test

3 d.f. test

Discussion

This is the largest analysis of new cancers in autotransplant recipients for MM in terms of the numbers of new cancers analyzed and the person years of follow up (Table 7). The site specific ICD-O coded data in Table 2 describes risk for each cancer. The overall risk of developing an invasive cancer after autologous transplantation for MM was similar to that expected among persons of similar age, gender and race in the general US population. The incidence rate consistent is with other reports from autotransplant studies in MM 6,12. In contrast to the overall new cancer risk, a clear increase in risk of myeloid malignancies (AML/MDS) and melanoma was detected. A prospective study by the Intergroup Francophone du Myeloma (IFM) randomizing subjects to lenalidomide or placebo post-transplant reported a virtually identical second cancer risk of 1.2 per 100 person-years in their placebo group (n=307)6.

Table 7. Comparison with new cancers reported from other major transplant studies.

| Current (CIBMTR) | CALGB1001046 | IFM7 | Usmani et al12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects (N) | 4161 | 231 | 307 | 1148 |

| Years included | 1990- 2010 | 2005 - 2009 | 2006-2008 | 1998-2007 |

| Person-Years at risk | 13387 | NR | NR | 6397 |

| Median age | 57 | 59 | 55 | NR |

| Median Follow Up | 48 mo | 34 mo | 30 mo | NR |

| New cancer cases | 163 | 24 | 32 | 73 |

| Cumulative incidence % | 4.21% at 5 yrs 5.09% at 7 yrs |

8% Lenalidomide 3% No maintenance |

5.5% Lenalidomide 1% No maintenance |

6.4% |

| New cancer/100 person years | 1.2 | NR | 3.1 LEN 1.2 No LEN |

1.14 |

| AML/MDS | 35 | 7 | 5 | 31 |

| Melanoma | 19 | 1 | 0 | NR |

There are several limitations to prior estimates of incidence and pathogenesis of new cancers in MM including small numbers of subjects, inadequate follow-up and imperfect ascertainment of new cancers13. Studies reporting few new cancers cannot adequately analyze risk- factors due to the low numbers of events of interest. Our cohort was composed of uniformly treated persons with MM in the US all of whom received an upfront autotransplant. The data span 2 decades during which time survival improved dramatically. Ascertainment and reporting of new cancers in our cohort was performed by the transplant centers with all reported new cancers confirmed by central review of pathology reports. Because we had many new cancers we were able to perform additional analyses in order to identify risk factors. Nevertheless, the retrospective nature of the study leads to the possibility of underreporting of second cancers in this study.

MM in persons not receiving an autotransplant is reported to be associated with an increased risk of synchronous and metachronous new cancers. This is also so in untreated persons and in persons with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS). A population-based study from the Swedish Cancer Registry reported an increased risk of skin, central nervous system, non-thyroid endocrine neoplasms and hematologic cancers, especially AML, in those with MM14. In another study a 2.4-fold increased risk of MDS was reported in persons with MGUS who had not received anti myeloma therapy.15. An inherent risk of MDS in MM patients has been proposed based on multi parameter flow studies of bone marrow samples taken prior to therapy16. These data suggest an inherent risk of developing AML/MDS independent of therapy.

Increasing age, male gender and obesity were associated with an increased risk of new cancers. Increasing age and male sex were also associated with SPM development in the IFM study6. In de novo AML the age-adjusted incidence is approximately 1.5 fold higher in males than females17,18. Males also have an increased risk of developing AML/MDS after exposure to ionizing radiation or nuclear weapons19.

Increasing body mass has been associated with an increased risk of several non-hematological cancers, i.e., esophageal, pancreas, colorectal, breast, endometrial, kidney, thyroid, and gall bladder cancers20. We found that a BMI >30 was an independent risk-factor for new cancers even in an age and sex matched case control analysis. In patients undergoing autotransplant for MM, there is no overall effect of BMI on survival, progression or non-relapse mortality21. Body mass is one of the factors that influences chemotherapy dosing. High dose pretransplant conditioning therapy (such as high-dose melphalan), is calculated based on weight or body surface area (BSA). Consequently, hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPC) in persons with a higher BMI may be exposed to more melphalan (on a dose per HPC basis) than those in persons with a lower BMI. In this case, it may not be possible to distinguish biologic mechanisms increasing cancer risk associated with obesity per se from those of melphalan exposure. the Although the mechanism by which obesity increases the risk of new cancers is unclear, it is important as an area of possible intervention and patient selection for post-transplant therapies such as lenalidomide which increase the risk.

Although smoking and radiation are strong carcinogens they were not associated with new cancer risk in our study22. This may relate to small sample size of smokers and the overall low incidence of smoking related cancers in the cohort. Exposure to alkylating drugs during induction therapy increases risk of new cancers in persons with MM especially the risk of AML/MDS1,2,4,23. We found no relationship between drugs used pretransplant and new cancer risk. However it must be noted that our cohort received transplant early in the course of disease with limited duration of pre-transplant therapy.

An increased risk of AML/MDS is reported in persons with MM in population-based non-transplant settings 5,13,14,23. Because MDS was not reportable to SEER and other cancer registries until 2001 and because of current concern about under-reporting 10 we did not calculate the O/E ratio specific for MDS in our study. The relatively few cases and limited data on pretransplant cytogenetics also limits our analyses of MDS. Age was the only significant risk-factor associated with AML/MDS similar to that reported for de novo AML. Interestingly, some studies report synchronous AML/MDS and MM at diagnosis. Moreover, biologic features of MDS have been described in pre-therapy bone marrow specimens using sensitive techniques16,24,25.

Immune suppression in other settings, example post kidney and heart transplant has been shown to correlate with an increased risk of developing AML26. Amongst kidney transplant recipients, the standardized incidence ratio for developing AML was 1.90 (95% confidence interval, 1.4– 2.4; O/E=54/29; P<0.001) while amongst heart transplant recipients it was 5.10 (3.4–7.1; O/E=31/6; P<0.001). In contrast to other post-transplant cancers, the increased risk of AML in heart transplant recipients did not begin until 3–4 years after transplant, indicating perhaps the risk is increased when immunosuppression is intense and prolonged. Notably the patients in our study were autologous transplant recipients and not subject to further post-transplant immune suppression.

The increased incidence of melanoma post-autotransplant could reflect a true increase or surveillance bias. A similar increase is reported in other transplant settings and in persons with immune suppression.27 An increased melanoma risk (standardized incidence ratio [SIR] = 1.36) among MM patients in the SEER registry is reported28. This underscores the importance of dermatologic surveillance in the post-transplant setting.

The survivorship of patients with multiple myeloma has been increasing in the era of autotransplant and new anti-myeloma therapies, and such patients can be expected to develop second cancers in higher numbers. A recent SEER based analysis suggested that the risks of solid tumor cancers among MM patients tend to rise slowly during follow up but show little overall difference in risk relative to the general population (SIR = 1.02 at ≥ 60 months)28. In contrast, SIRs associated with AML are markedly elevated at 24-59 months (SIR = 9.28) and at ≥ 60 months (SIR = 10.77). We also found a continued risk of new cancers over several years (Figure 1). Recent studies indicating a higher risk of new cancers in persons receiving lenalidomide had a median follow up of 30-34 months6,7. Consequently, a true picture of long term risk may not have emerged in these studies and thus longer follow up of subjects is essential. Our data show the risk of myeloma relapse is significantly higher than the risk of new cancers (Figure 1) and that the overall new cancer risk is similar to that of the general population.

In conclusion, our data indicate no significant increase in overall risk of new cancers in persons with MM receiving autotransplants compared with a matched US population. However, some cancers such as AML and melanoma are significantly increased in autotransplant recipients compared with a similar US population. Factors associated with an increased risk are older age, male gender and obesity. The biological bases of these associations are unknown. The risk of MM progression and death from MM continues to exceed the risk of new cancer.

We analyzed incidence of new cancers in 4161 myeloma autotransplant recipients.

The incidence rate of new cancers was 1.2 per 100 person-years.

Overall incidence was similar to an age, sex and race adjusted US population.

Acute myeloid leukemia and melanoma were observed at higher than expected rates.

Obesity, age and male sex were associated with new cancer in multivariate models.

Acknowledgments

The CIBMTR is supported by Public Health Service Grant/Cooperative Agreement U24-CA076518 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); a Grant/Cooperative Agreement 5U10HL069294 from NHLBI and NCI; a contract HHSH250201200016C with Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA/DHHS); two Grants N00014-12-1-0142 and N00014-13-1-0039 from the Office of Naval Research; and grants from Actinium Pharmaceuticals; Allos Therapeutics, Inc.; Amgen, Inc.; Anonymous donation to the Medical College of Wisconsin; Ariad; Be the Match Foundation; Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association; Celgene Corporation; Chimerix, Inc.; Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; Fresenius-Biotech North America, Inc.; Gamida Cell Teva Joint Venture Ltd.; Genentech, Inc.; Gentium SpA; Genzyme Corporation; GlaxoSmithKline; Health Research, Inc. Roswell Park Cancer Institute; HistoGenetics, Inc.; Incyte Corporation; Jeff Gordon Children's Foundation; Kiadis Pharma; The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society; Medac GmbH; The Medical College of Wisconsin; Merck & Co, Inc.; Millennium: The Takeda Oncology Co.; Milliman USA, Inc.; Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.; National Marrow Donor Program; Onyx Pharmaceuticals; Optum Healthcare Solutions, Inc.; Osiris Therapeutics, Inc.; Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.; Perkin Elmer, Inc.; Remedy Informatics; Sanofi US; Seattle Genetics; Sigma-Tau Pharmaceuticals; Soligenix, Inc.; St. Baldrick's Foundation; StemCyte, A Global Cord Blood Therapeutics Co.; Stemsoft Software, Inc.; Swedish Orphan Biovitrum; Tarix Pharmaceuticals; TerumoBCT; Teva Neuroscience, Inc.; THERAKOS, Inc.; University of Minnesota; University of Utah; and Wellpoint, Inc. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) or any other agency of the U.S. Government. Additional support for this study was provided by Celgene Corporation.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-Interest Statement: The authors have no conflicts to disclose

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bergsagel DE, et al. The chemotherapy on plasma-cell myeloma and the incidence of acute leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1979;301:743–748. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197910043011402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Govindarajan R, et al. Preceding standard therapy is the likely cause of MDS after autotransplants for multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 1996;95:349–353. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.d01-1891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landgren O, Mailankody S. Update on second primary malignancies in multiple myeloma: a focused review. Leukemia. 2014 doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mailankody S, et al. Risk of acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes after multiple myeloma and its precursor disease (MGUS) Blood. 2011;118:4086–4092. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-355743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sevilla J, et al. Secondary acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplasia after autologous peripheral blood progenitor cell transplantation. Ann Hematol. 2002;81:11–15. doi: 10.1007/s00277-001-0400-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Attal M, et al. Lenalidomide maintenance after stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1782–1791. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1114138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCarthy PL, et al. Lenalidomide after stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1770–1781. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1114083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palumbo A, et al. Second primary malignancies with lenalidomide therapy for newly diagnosed myeloma: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:333–342. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70609-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hankey BF, Ries LA, Edwards BK. The surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program: a national resource. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 1999;8:1117–1121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma X, Does M, Raza A, Mayne ST. Myelodysplastic syndromes: incidence and survival in the United States. Cancer. 2007;109:1536–1542. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark TG, Altman DG, De Stavola BL. Quantification of the completeness of follow-up. Lancet. 2002;359:1309–1310. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08272-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Usmani SZ, et al. Second malignancies in total therapy 2 and 3 for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: influence of thalidomide and lenalidomide during maintenance. Blood. 2012;120:1597–1600. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-421883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas A, et al. Second malignancies after multiple myeloma: from 1960s to 2010s. Blood. 2012;119:2731–2737. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-381426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong C, Hemminki K. Second primary neoplasms among 53 159 haematolymphoproliferative malignancy patients in Sweden, 1958-1996: a search for common mechanisms. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:997–1005. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6691998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roeker LE, et al. Risk of acute leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes in patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS): a population-based study of 17 315 patients. Leukemia. 2013;27:1391–1393. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matarraz S, et al. Myelodysplasia-associated immunophenotypic alterations of bone marrow cells in myeloma: are they present at diagnosis or are they induced by lenalidomide? Haematologica. 2012;97:1608–1611. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.064121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.SEER Cancer Statistics Factsheets: Leukemia. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/leuks.html. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cartwright RA, Gurney KA, Moorman AV. Sex ratios and the risks of haematological malignancies. Br J Haematol. 2002;118:1071–1077. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsu WL, et al. The incidence of leukemia, lymphoma and multiple myeloma among atomic bomb survivors: 1950-2001. Radiation research. 2013;179:361–382. doi: 10.1667/RR2892.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Renehan AG, Tyson M, Egger M, Heller RF, Zwahlen M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet. 2008;371:569–578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60269-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vogl DT, et al. Effect of obesity on outcomes after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2011;17:1765–1774. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berrington de Gonzalez A, et al. Proportion of second cancers attributable to radiotherapy treatment in adults: a cohort study in the US SEER cancer registries. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:353–360. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70061-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Group, F. L. Acute leukaemia and other secondary neoplasms in patients treated with conventional chemotherapy for multiple myeloma: a Finnish Leukaemia Group study. European journal of haematology. 2000;65:123–127. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2000.90218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hasskarl J, et al. Association of multiple myeloma with different neoplasms: systematic analysis in consecutive patients with myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2011;52:247–259. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2010.529207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korde N, et al. Early Myelodysplastic Changes Present in Substantial Proportion of Monoclonal Gammopathy of Unknown Significance (MGUS) and Smoldering Multiple Myeloma (SMM) Patients. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2012;120:1805-. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gale RP, Opelz G. Commentary: does immune suppression increase risk of developing acute myeloid leukemia? Leukemia. 2012;26:422–423. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jensen P, et al. Skin cancer in kidney and heart transplant recipients and different long-term immunosuppressive therapy regimens. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1999;40:177–186. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70185-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Razavi P, et al. Patterns of second primary malignancy risk in multiple myeloma patients before and after the introduction of novel therapeutics. Blood cancer journal. 2013;3:e121. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2013.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]