Abstract

We have demonstrated that enteral glutamine provides protection to the post ischemic gut and that PPARγ plays a role in this protection. Using Cre/lox technology to generate an intestinal-epithelial cell (IEC) specific PPARγ null mouse model, we now investigated the contribution of IEC PPARγ to glutamine’s local and distant organ protective effects. These mice exhibited absence of expression of PPARγ in the intestine but normal PPARγ expression in other tissues. Following one hour of intestinal ischemia under isoflurane anesthesia, wild type and null mice received enteral glutamine (60 mM) or vehicle followed by 6 hours of reperfusion or 7 days in survival experiments and compared to shams. Small intestine. liver, and lungs were analyzed for injury and inflammatory parameters. Glutamine provided significant protection against gut injury and inflammation with similar protection in the lung and liver. Changes in systemic TNFα reflected those seen in the injured organs. Importantly, mice lacking IEC PPARγ had worsened injury and inflammation and glutamine lost its protective effects in the gut and lung. The survival benefit found in glutamine treated wild type mice was not observed in null mice. Using an IEC-targeted loss-of-function approach, these studies provide the first in vivo confirmation in native small intestine and lung that PPARγ is responsible for the protective effects of enteral glutamine in reducing intestinal and lung injury and inflammation and improving survival. These data suggest that early enteral glutamine may be a potential therapeutic modality to reduce shock-induced gut dysfunction and subsequent distant organ injury.

Keywords: intestinal-cell (IEC) specific PPARγ null mouse, cre/lox, neutrophil infiltration, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) remains the most common cause of death in severely injured patients in shock who do not die from early uncontrolled hemorrhage or brain injury.(1) The institution of early enteral nutrition decreases septic morbidity and therefore lessens the incidence of post-injury MODS.(2,3) However, standard practice is to begin enteral nutrition once resuscitation is complete, well after the localized (gut) and systemic production and release of multiple pro-inflammatory mediators has occurred. The separation of nutritional support from the provision of key nutrients such as glutamine has led to a further appreciation of the immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory benefits of isolated nutrients.(4) The mortality of MODs remains high, in part due to the lack of early therapeutic interventions to prevent shock-induced gut dysfunction.(5) The purpose of the current study was to determine if glutamine may represent such an intervention.

Glutamine is a conditionally essential amino acid after critical illness or injury.(6) We have been interested in glutamine’s gut protective effects and have shown that as a metabolizable nutrient, it can protect against gut injury and impaired absorption by supplying the post ischemic gut with needed ATP.(7) Additionally, these protective effects are mediated in vitro and in vivo by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ). (8-11) PPARγ is a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily of transcription factors and is highly expressed in adipocytes, intestinal epithelium, immune cells, skeletal muscle cells, and hepatocytes.(12) Its most important natural ligand is 15-deoxy PG J2 while the glitazones are well studied synthetic ligands that have been shown to reduce intestinal inflammation in models of colitis.(13)

In the current study we assessed the role of intestinal epithelial PPARγ in glutamine’s protection from intestinal ischemia/reperfusion-induced intestinal and distant organ (lung) injury. We generated conditional null mice with an intestinal epithelial cell specific deletion of PPARγ and tested the hypothesis that enteral glutamine protects the gut and mitigates distant organ (lung) injury via intestinal PPARγ.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All animal procedures performed were protocols approved by the University of Texas Houston Medical School Animal Welfare Committee. The experiments were conducted in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All animals were housed at constant room temperature with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle with access to food and water ad libitum. Male C57BL/6J mice, 8-10 weeks of age were used for all experiments.

Generation of intestinal-specific PPARγ deficient mice

Cre/lox technology was used to generate intestinal-specific PPARγ deficient mice as previously described. (14) Homozygous floxed PPARγ (f/f) mice with VFB background were generously provided by Dr. F Gonzalez (NIH). Floxed mice were bred with C57BL/6J for 7 generations to get PPARγ f/f mice with C57BL/6J background. The targeted allele, containing loxP sites flanking exon 2 of the PPARγ gene, was crossed into a transgenic mouse expressing Cre recombinase under control of the villin1 to yield mice with a targeted deletion of PPARγ in intestinal villi and crypt cells.

Quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from small and large bowel, heart, liver, lung and kidney using TRI reagent (Sigma, St. Louis). One ug of RNA was used to reverse cDNA using Bio-Rad iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) then 50ng of cDNA was used to perform quantitative real-time PCR to check PPARγ mRNA expressions using TaqMan® Gene Expression Assays with a PPARγ probe (Mm01184321, Applied Biosystems) as a target and an actin probe (Mm00607939_s1, Applied Biosystems) as the internal reference. The relative expression level of target genes was normalized to that of the internal reference gene and to a calibrator sample that was run on the same plate. The normalized relative expression levels were automatically calculated using commercial software (StepOne Software V2.1, Applied Biosystems).

Western Blot

Target tissues were homogenized and lysates were prepared with RIPA buffer (Sigma, Milwaukee, WI) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, Milwaukee, WI). The lysates were denatured, loaded on 4% to 12% linear gradient NuPAGE gel, and transferred to Immobilon PVDF blotting membrane (Millipore, Billerico, Massachusetts). The membranes were blocked for 1hour at room temperature Odyssey blocking buffer (Li-cor, cat:927-40000), incubated with rabbit anti-PPARγ antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling, cat:5468) overnight at 4°C, followed by washing and incubation with IRDye 800CW conjugated goat anti –rabbit IgG (1:5000, Li-cor, cat: 926-32211) for 1 hour at room temperature, then the membrane was washed and scanned with Odyssey CLx Infrared Imaging System (Li-cor, Lincoln, Nebraska).

Gut ischemia/reperfusion

Animals were anesthetized under inhalation of isoflurane. For gut ischemia/reperfusion (I/R), a midline laparotomy was performed and the superior mesenteric artery was clamped for 60 minutes. Reperfusion was established one hour later by removal of the clamp. Animals were sacrificed after six hours and the full thickness jejunum, liver, and lung harvested and bronchial alveolar fluid obtained. Sham animals underwent an identical procedure without superior mesenteric artery occlusion. Animals were randomly divided into 6 groups (8 animals/group): WT sham, KO sham, WT subjected to I/R + vehicle, KO subjected to I/R + vehicle, WT subjected to I/R plus glutamine, and KO subjected to I/R plus glutamine. For animals in the glutamine group, 60 mM glutamine was instilled into the intestine at the onset of reperfusion and compared to vehicle treated animals as we have described (11). For survival experiments, the superior mesenteric artery was occluded for 75 minutes then the animals were observed for 7 days (15-18 animals/group).(15)

Intestinal studies

To evaluate intestinal histopathology, 5-μm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For quantitative estimation of damage, sections were scored with a light microscope in a blinded manner. The morphological criteria were used as described by Chiu with a scoring range from 0 to 5, where 5 is the most severely injured. (16)

Neutrophil infiltration was assessed in intestinal sections by staining with Naphthol AS-D Chloroacetate Esterase Cytochemical Staining kit (Sigma Diagnostics, Milwaukee, WI), which identifies specific leukocyte esterases. To quantitate assessment of neutrophil infiltration into the intestinal mucosa, a total of 50 high-power fields (×400) under a light microscope were counted for positively stained cells in a blinded fashion.

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity was measured using the MPO Colorimetric Activity Assay Kit (BioVision Research Products, Mountain View, CA, USA). Activity was normalized according to milligrams of total protein in tissue lysates. Bio-Rad Protein Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc. Hercules, CA, USA) was used to determine protein concentration.

Apoptotic cells were stained in sections using an In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). The apoptotic index was calculated as a ratio of the positively stained cell number to the total cell number in each field. At least of 400 cells were counted.

Lung studies

Lungs were harvested and sections fixed with10% neutral buffered formaldehyde solution then embedded in paraffin and sectioned. At least two sections from each animal were stained with hematoxylin and eosin then scored using a 4-point scale for six separate criteria.(17) The overall lung injury score was calculated by averaging the six indices of injury.

Lung sections were stained using a Naphthol AS-D Chloroacetate Esterase Cytochemical Staining kit(Sigma Diagnostics, Milwaukee, WI), which identifies specific leukocyte esterases. Two random images were taken from each lung section with a light microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti, Melville, NY) at 200X and quantified using ImageJ software (NIH). The neutrophil infiltration is presented as the percentage of neutrophil positive staining area / total lung tissue area.

Infiltration of neutrophils was assessed by MPO immunofluorescence staining and MPO activity. For immunofluorescence, paraffin embedded tissue was cut into 5 μm-thick sections then incubated with MPO primary antibody (1:100 MPO mouse monoclonal antibody, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) followed by incubation with secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse, Alexa Fluor 568, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Two random images were taken from each lung section with a fluorescent microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti, Melville, NY) at 200X and quantified using ImageJ software (NIH). MPO activity was measured using a commercially available kit per manufacturer’s instructions (Enzo Life Sciences, ADI-907-029).

Liver studies

Liver tissue was harvested and sections fixed with10% neutral buffered formaldehyde solution then embedded in paraffin and sectioned. At least two sections from each animal were stained with hematoxylin and eosin then scored on a scale from zero to three.(18)

Systemic parameters

Blood was obtained at the time of sacrifice and TNF-α was determined using the mouse tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFalpha) ELISA kit from MyBioSource (San Diego, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Three liver function assays were also performed, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALST) and alkaline phosphatase (alk phos) according to manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO)

Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as mean ±SEM. Data were analyzed by one way analysis of variance with Bonferroni correction. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Intestinal-specific PPARγ deficiency

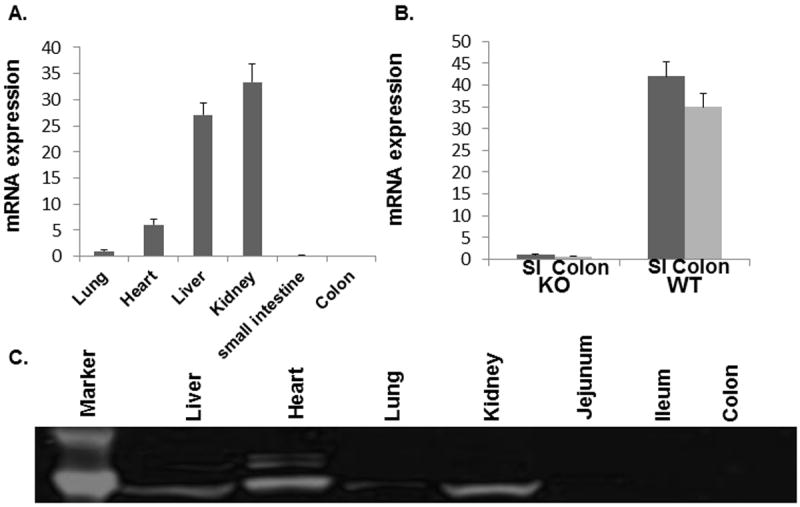

To investigate the contribution of IEC PPARγ to glutamine’s gut protective effects, conditional null mice with intestinal epithelial cell specific deletion of PPARγ was generated using a floxed PPAR allele and Cre recombinase under the control of the villin gene promoter. The intestinal specific deletion in PPARγ is shown in Figure 1. MRNA and protein expression is present in lung, heart, liver, and kidney, but is not detectable in the small or large intestine (Fig 1A and C). WT mice have approximately 40 fold more PPARγ mRNA expression in the small intestine compared to KO mice (Fig. 1B), which display normal growth and development.

Figure 1. Intestinal specific conditional PPARγ null mice.

Distribution of PPARγ among different organs by mRNA and protein is shown, with specificity of the deletion demonstrated. Homozygous floxed PPARγ (f/f) mice with VFB background were bred with C57BL/6J for 7 generations to get PPARγf/f mice with C57BL/6J background. The targeted allele, containing loxP sites flanking exon 2 of the PPARγ gene, was crossed into a transgenic mouse expressing Cre recombinase under control of the villin1 to yield mice with a targeted deletion of PPARγ in intestinal villi and crypt cells. (A). Tissue expression of PPARγ in intestinal specific conditional PPARγ null mice; (B). Comparison of PPARγ mRNA between KO and WT small and large intestines; and (C). Protein confirmation showing specificity of PPARγ deletion.

Luminal glutamine loses its gut protective effects in intestinal-specific PPARγ null mice

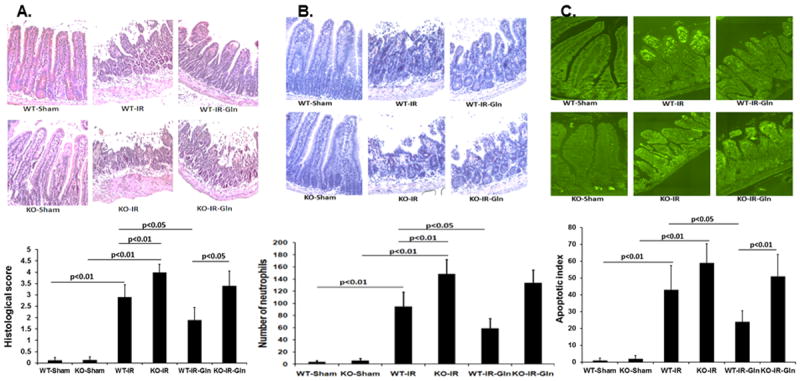

Intestinal morphology in sham null mice was similar to WT sham mice (0.12±0.13 vs 0.14±0.13) (Fig. 2A). Severe damage occurred after I/R in the WT intestine (2.90±0.55) which was significantly worsened in null mice (4.00±0.35). As expected, luminal glutamine protected against mucosal damage in the WT mice (1.90±0.54) but this effect was abolished in the intestine of null mice (3.40±0.65).

Figure 2. Effect of intestinal epithelial cell deletion of PPARγ on gut injury and inflammation.

Wild type and null mice underwent intestinal ischemia following by enteral glutamine or vehicle. After six hours intestine was harvested. Representative images and corresponding quantification of (A) mucosal histologic injury, (B) neutrophil infiltration, and (C) apoptotic index. Mean ± SEM, ANOVA with Bonferroni correction; n=8/group.

Intestinal inflammation was first evaluated by specific leukocyte esterase staining (Fig. 2B). There were rare neutrophils detected in the sham WT (3.6±2.4) and KO (5.6±3.6) intestines. Following intestinal I/R, there was a significant increase in neutrophil infiltration in the KO intestine (148.4±23.9) compared to the WT (95.0±23.3). Luminal glutamine administration attenuated neutrophil infiltration in the WT (59.0±16.3) but not in the KO intestine (133.6±21.2). Consistent with neutrophil infiltration, MPO activity was higher in the KO intestine (87.0±12.5) than in the WT controls (63.1±7.5; p<0.01) and significantly lessened by glutamine in the WT (44.4±10.3) (p<0.05) but not in the KO intestine (75.8±16.5). MPO activity was minimal in both the WT (6.6±2.5) and KO (8.6±2.4) sham intestines.

Intestinal I/R leads to epithelial cell apoptosis (19) and PPARγ has been shown to possess anti-apoptotic properties.(20) We therefore examined the effect of PPARγ deficiency on intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis (Fig. 2C). There were very few apoptotic cells in both the WT and KO sham intestines (1.0±1.2 and 2.0±1.9, respectively). However, apoptosis was dramatically increased by I/R in the WT (40.6±11.6) and further increased in the KO intestine (59.0±11.4). Similar to histopathology and inflammation, glutamine treatment protected against cell apoptosis in the WT intestine (24.0±6.5), but this protective effect was lost in the KO intestine (51.0±12.9).

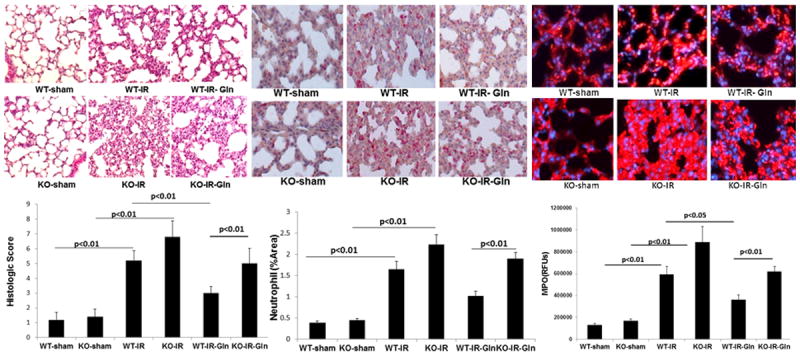

Luminal glutamine mitigates lung injury in wild type but not intestinal-specific PPARγ null mice

Lung histopathology was similar in WT and null mice (1.14±0.40 vs 1.28±0.42) but was increased by I/R in WT (5.0±0.48) and in null mice (7.0±0.75) (Fig. 3A). Luminal glutamine was protective in WT (3.14±0.34) but not null mice lungs (5.4±0.72).

Figure 3. Effect of intestinal epithelial cell deletion of PPARγ on lung injury and inflammation.

Wild type and null mice underwent intestinal ischemia following by enteral glutamine or vehicle. After six hours lung was harvested. Representative images and corresponding quantification of (A) histologic injury, (B) neutrophil infiltration, and (C) myeloperoxidase immunostaining. Mean ± SEM, ANOVA with Bonferroni correction; n=8/group.

Lung inflammation was evaluated by leukocyte esterase staining as well as by myeloperoxidase activity and immunostaining (Fig. 3). There was no difference in neutrophil staining between sham WT and null mice (0.38±0.03 vs 0.44±0.04%) (Fig. 3B). Intestinal I/R significantly increased neutrophil staining in WT mice lungs (1.6±0.20%) and in null mice (2.2±0.20%). Glutamine was protective in WT (1.0±0.1%) but not in null mice lungs (1.9±0.1%). MPO activity showed similar findings with no differences between shams (2.67±0.62 WT vs 3.07±0.49 ng/mg protein KO), an increase after I/R in WT (8.73±1.49ng/mg protein) and null mice lungs (9.76±1.24ng/mg protein). Again, no protection was seen by glutamine in null (9.06±0.96ng/mg) mice, only WT mice lungs (6.78±1.04ng/mg protein). MPO immunostaining is shown in Fig. 3C and findings were consistent with MPO activity.

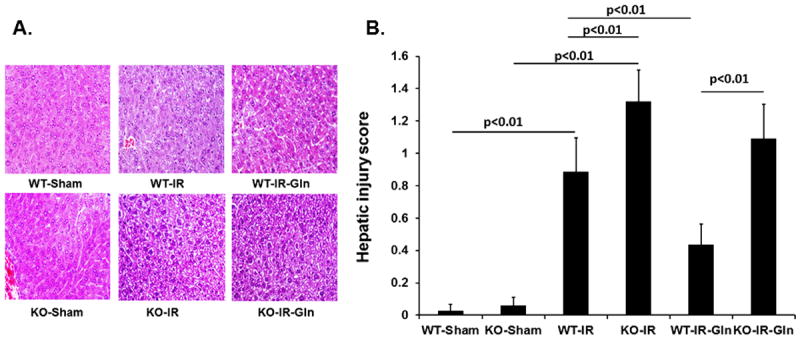

Liver histopathologic injury reduced by luminal glutamine in wild type but not intestinal-specific PPARγ null mice

Liver injury was assessed as the liver receives blood flow directly from the intestine. Although liver histopathology was the same magnitude as gut injury, the pattern of changes was similar. There were no differences between sham WT and null mice (0.03±0.02 vs 0.06±0.02) but there was a significant increase by I/R in WT mice (0.89±0.08) with a further increase in null mice (1.32±0.06) (Fig. 4). Luminal glutamine was protective in WT (0.43±0.06) but not in the null mice liver (1.09±0.09). Results of liver parameters are shown in Table 1. Although there was a increase in AST, ALT, and alkaline phosphatase in all groups compared to shams, there were not significant differences between I/R groups.

Figure 4. Effect of enteral glutamine on liver injury.

Wild type and null mice underwent intestinal ischemia following by enteral glutamine or vehicle. After six hours liver was harvested. Representative images (A) and corresponding quantification of (B) histologic injury. Mean ± SEM, ANOVA with Bonferroni correction; n=6/group.

Table 1.

Indices of liver function after gut I/IR and luminal glutamine

| Groups | AST (U/L) | ALT (U/L) | ALK Phos)(U/L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| WT sham | 28.5 ± 3.9 | 16.6 ± 2.6 | 62.8 ± 11.0 |

| KO sham | 31.5 ± 2.3 | 17.8 ± 2.2 | 73.9 ± 11.0 |

| WT IR | 94.9 ± 7.6* | 61.0 ± 8.4* | 184.5 ± 12.2* |

| KO IR | 102.2 ± 10.9* | 72.3 ± 7.9* | 196.0 ± 9.3* |

| WT IR gln | 71.1 ± 7.2* | 44.4 ± 7.9* | 137.4 ± 13.8* |

| KO IR gln | 88.3 ± 6.5* | 65.8 ± 4.8* | 176.1 ± 10.2* |

Data are shown as mean ± SEM, n=6/group, ANOVA with Bonferroni correction;

= p<0.01 vs sham WT and KO.

IR= ischemia/reperfusion, gln-glutamine; AST=aspartate aminotransferase; ALT=alanine aminotransferase; ALP phos=alkaline phosphatase

Changes in systemic TNFα reflect changes in injured organs

Systemic TNFα levels were measured, as this cytokine is known to be elevated in injured patients and after gut ischemia. Changes in TNFα levels were similar to those found in the gut, lung, and liver. Levels were similar between sham WT and KO mice (17.0±2.8 pg/ml) but dramatically increased after gut I/R in WT mice (526.0±30.3 pg/ml) with a further significant increase in KO mice (839.3±54.6). Luminal glutamine lessened TNFα in WT (203.5±12.9 pg/ml) but not KO mice (746.3±50.0 pg/ml)

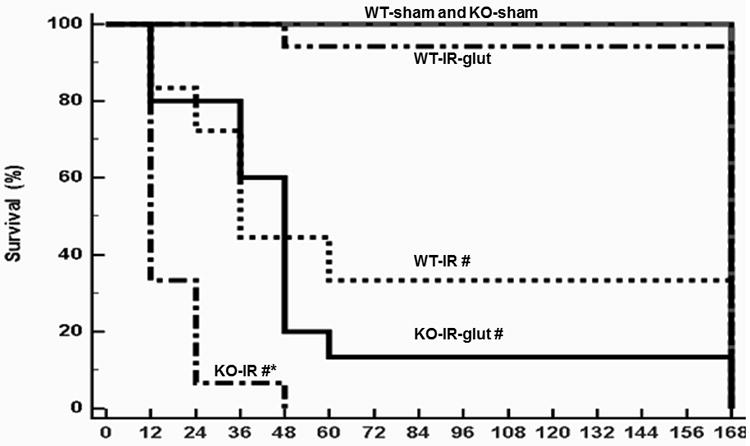

Intestinal specific PPARγ deficiency increases mortality in glutamine treated mice after gut I/R

All sham WT and PPARγ null mice survived (Fig. 5). Luminal glutamine significantly improved survival in WT mice after gut I/R. However, the improvements in survival seen after glutamine in WT mice were not observed in KO mice.

Figure 5. Effect of enteral glutamine on survival in wild type and intestinal specific conditional PPARγ KO mice.

Mice were treated with enteral glutamine or vehicle after 75 minutes of intestinal ischemia and survival was determined for seven days. Data were analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method, n=15-18/group. #p<0.05 vs. WT-sham, KO-sham, and WT-IR-Gln; ‡p<0.5 vs WT-IR.

DISCUSSION

We used an intestinal epithelial cell (IEC)-targeted loss-of-function approach to determine the role of IEC PPARγ in both gut and lung protection by luminal glutamine in the post ischemic gut. We demonstrated that glutamine provided significant protection against gut injury and inflammation with similar protection in the lung. Importantly, in mice lacking IEC PPARγ glutamine lost its protective effects. Additionally, the survival benefit found in the glutamine treated wild type mice were not observed in null mice.

The importance of IEC PPARγ in colonic epithelium has been shown in rodent studies of experimental inflammatory bowel disease. (21,22) Mice with a targeted deletion of PPARγ in IEC had worsened parameters of colonic disease such as inflammatory lesions and diarrhea. To our knowledge, the current study is the first to examine IEC PPARγ in the small bowel and the first to demonstrate an increase in mortality with loss of IEC PPARγ after injury. We chose to examine the small bowel, and the jejunum in particular, as this is the site of glutamine absorption. Mice lacking IEC PPARγ were generated by crossing the transgenic mouse expressing Cre recombinase under control of the villin1. Because villin 1 is found in epithelial cells of the large and small intestine (23), these mice lack PPARγ throughout the intestine. We have not investigated other areas of the bowel in our model.

We became interested in the protective role of PPARγ in the intestine after we demonstrated in vivo that enteral glutamine increased PPARγ DNA binding activity and was associated with a decrease in mucosal injury and inflammation.(11) In vitro there was a time and concentration-dependent increase in PPARγ transcriptional activity, but not mRNA or protein, by glutamine.(24) We hypothesized that glutamine functioned through competition for the PPARγ ligand binding site. However, our data demonstrated that glutamine, via degradation to glutamate, activated PPARγ via the endogenous PPARγ intestinal epithelial ligands, 15-S-hydroxyl-eicosatetraenoic acid (15-S-HETE) and dehydrogenated 13-hydroxyoctaolecadienoic acid (13-OXO-ODE).

Levy et al have shown that shock, trauma, or sepsis-induced gut injury causes the gut to become a cytokine-generating organ, with toxic gut-derived factors found in the mesenteric lymph that result in distant organ (lung) injury and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS).(25) As the lung is the first organ to receive mesenteric lymph and MODS remains the most common cause of late deaths in severely injured patients in shock (26), we examined the ability of luminal glutamine to protect against local and distant organ (lung) injury in an established rodent model of MODS.(27) Indeed, gut derived protection by glutamine was similarly demonstrated in the lung. The finding that glutamine lost its protective effects in the lung when intestinal PPARγ was lacking, highlights the important role of the intestinal epithelium in MODS. The rather modest changes by glutamine in the liver underscores the important role of the mesenteric lymph.

The early administration of enteral glutamine to patients in shock is feasible, as we have shown in a prospective randomized pilot study of severely injured patients.(28) In fact, glutamine administered during active shock resuscitation after injury was safe and well tolerated. Wischmeyer et al recently published a meta-analysis of 26 randomized controlled studies of intravenous supplementation and also demonstrated benefit. There was a significant decrease in in-hospital mortality and hospital length of stay and a trend towards a reduction in overall mortality, infectious complications, and ICU length of stay.(29) However, a prospective randomized trial by Heyland et al in patients with established MODS, parenteral and enteral glutamine supplementation resulted in a nonsignificant trend towards increased mortality.(30) The reasons for this rather surprising finding are unclear. Unlike in the current laboratory study or in our clinical study in trauma patients, Heyland et al administered glutamine only after the development of MODS and by both the enteral and parenteral routes, thus generating high systemic levels of glutamine. Additionally, many of these patients had underlying renal dysfunction and high serum glutamine levels even prior to supplementation.(31) Though only speculative, correcting low serum levels of glutamine may be maladaptive or glutamine toxicity may have resulted from already high levels of endogenous glutamine.(32) Additionally, prior clinical studies which showed benefit, as well as the current study, all used L-glutamine. In the REDOX trial, glutamine was delivered as alanyl-glutamine. Even though alanyl-glutamine is safe when added to total parenteral nutrition, the dose used in REDOX was high and the alanine contribution may have been detrimental or may have masked the benefit by glutamine. We have shown in our rodent I/R model that there was a significant difference in gut parameters of injury and function between enteral alanine and enteral glutamine, with only glutamine demonstrating protection.(7,9) Although both alanine and glutamine are absorbed across the gut epithelium by sodium-mediated secondary active transport, only glutamine is metabolized by the gut and can maintain energy supplies to the hypoperfused gut.(7) Administering only enteral glutamine and doing so prior to the development of distant organ injury is supported in a more recent article by Heyland et al, and is most applicable to trauma and burn patients.(33) Additionally, enteral supplementation alone does not usually increase systemic levels of glutamine.(34,35) Our findings suggest that the early use of enteral glutamine prior to distant organ injury is safe and may mitigate the development of distant organ failure.

In conclusion, we used an intestinal epithelial cell (IEC)-targeted loss-of-function approach to determine the role of IEC PPARγ in gut, liver, and lung protection by luminal glutamine in the post ischemic gut. We demonstrated that glutamine provided significant protection against both local (gut) and distant (lung) injury and inflammation, with a lesser degree of protection in the liver. Mice lacking IEC PPARγ not only demonstrated worsened gut, lung, and liver injury and inflammation but the survival advantage of glutamine was not observed in null mice. These studies demonstrate for the first time that intestinal epithelial cell PPARγ plays a critical role in enteral glutamine’s protection to the post ischemic gut. Additionally, this study supports further investigation of glutamine and other PPARγ agonists targeting the gut.

Acknowledgments

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant (RO1 GM077282)

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial, or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

References

- 1.Pfeifer R, Tarkin IS, Rocos B, Pape HC. Patterns of mortality and causes of death in polytrauma patients- has anything changed? Injury. 2009;40(9):907–911. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marik PE, Zaloga P. Early enteral nutrition in acutely ill patients: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2002;29:2264–2270. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200112000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore FA, Feliciano DV, Andrassy RJ, McArdle AH, Booth FV, Morgenstein-Wagner TB, Kellum JM, Jr, Welling RE, Moore EE. Early enteral feeding, compared with parenteral, reduces postoperative septic complications - the results of a meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 1992;216:172–183. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199208000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santora R, Kozar RA. Molecular Mechanisms of Pharmaconutrients. J Surg Res. 2010;161(2):288–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rupani B, Caputo FJ, Watkins AC, Vega D, Magnotti LJ, Lu Q, Xu da Z, Deitch EA. Relationship between disruption of the unstirred mucus layer and intestinal restitution in loss of gut barrier function after trauma hemorrhagic shock. Surgery. 2007;141(4):481–9. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wischmeyer PE. Glutamine: mode of action in critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(9 Suppl):S541–4. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000278064.32780.D3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kozar RA, Schultz SG, Hassoun HT, DeSoignie R, Weisbrodt NW, Haber MH, Moore FA. The type of sodium-coupled solute modulates small bowel mucosal injury, transport function and ATP after Ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(3):810–6. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ban K, Kozar RA. Enteral glutamine: A novel mediator of PPARγ in the postischemic gut. J Leuk Biol. 2008;84(3):595–599. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1107764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kozar RA, Schultz SG, Bick RJ, Poindexter BJ, DeSoignie R, Moore FA. Enteral glutamine but not alanine maintains small bowel barrier function after ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Shock. 2004;21(5):433–7. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200405000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kozar RA, Verner-Cole E, Schultz SG, Sato N, Bick RJ, Desoignie R, Poindexter BJ, Moore FA. The immune-enhancing enteral agents arginine and glutamine differentially modulate gut barrier function following mesenteric ischemia/reperfusion. J Trauma. 2004;57(6):1150–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000151273.01810.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sato N, Moore FA, Smith MA, Zou L, Olufemi-Moore S, Schultz SG, Kozar RA. Differential induction of PPAR-gamma by luminal glutamine and iNOS by luminal arginine in the rodent postischemic small bowel. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290(4):G616–23. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00248.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Escher P, Braissant O, Basu-Modak S, Michalik L, Wahli W, Desvergne B. Rat PPARs: Quantitative analysis in adult rat tissues and regulation in fasting and refeeding. Endocrinology. 2001;142(10):4195–202. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.10.8458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Celinski K, Dworzanski T, Fornal R, Korolczuk A, Madro A, Brzozowski T, Slomka M. Comparison of anti-inflammatory properties of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists rosiglitazone and troglitazone in prophylactic treatment of experimental colitis. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2013;64(5):587–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guri AJ, Mohapatra SK, Horne WT, 2nd, Hontecillas R, Bassaganya-Riera J. The role of T cell PPAR γ in mice with experimental inflammatory bowel disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-10-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ban K, Peng Z, Kozar RA. Inhibition of ERK1/2 worsens intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e76790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiu CJ, McArdle AH, Brown R, Scott HJ, Gurd FN. Intestinal mucosal lesion in low-flow states: I. A morphological, hemodynamic, and metabolic reappraisal. Arch Surg. 1970;101(4):478–83. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1970.01340280030009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee CC, Lee RP, Subeq YM, Lee CJ, Chen TM, Hsu BG. Fluvastatin attenuates severe hemorrhagic shock-induced organ damage in rats. Resuscitation. 2009;80(3):372–8. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Camargo CA, Jr, Madden JF, Gao W, Selvan RS, Clavien PA. Interleukin-6 protects liver against warm ischemia/reperfusion injury and promotes hepatocyte proliferation in the rodent. Hepatology. 1997;26(6):1513–20. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Paola R, Impellizzeri D, Torre A, Mazzon E, Cappellani A, Faggio C, Esposito E, Trischitta F, Cuzzocrea S. Effects of palmitoylethanolamide on intestinal injury and inflammation caused by ischemia-reperfusion in mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;91(6):911–20. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0911485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fong WH, Tsai HD, Chen YC, Wu JS, Lin TN. Anti-apoptotic actions of PPAR-gamma against ischemic stroke. Mol Neurobiol. 2010;41(2-3):180–6. doi: 10.1007/s12035-010-8103-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adachi M, Kurotani R, Morimura K, Shah Y, Sanford M, Madison BB, Gumucio DL, Marin HE, Peters JM, Young HA, Gonzalez FJ. Peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ in colonic epithelial cells protects against experimental inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2006;55:1104–13. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.081745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohapatra SK, Guri AJ, Climent M, Vives C, Carbo A, Horne WT, Hontecillas R, Bassaganya-Riera J. Immunoregulatory actions of epithelial cell PPARγ at the colonic mucosa of mice with experimental inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(4):e10215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uelmann F, Chamaillard M, El-Marjou F, Simon A, Netter J, Vignjevic D, Nichols BL, Quezada-Calvillo R, Grandjean T, Louvard D, Revenu C, Robine S. Enterocyte loss of polarity and gut wound healing rely upon the F-actin-severing function of villin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(15):E1380–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218446110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ban K, Sprunt JM, Martin S, Yang P, Kozar RA. Glutamine activates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in intestinal epithelial cells via 15-S-HETE and 13-OXO-ODE: A novel mechanism. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;301(3):G547–54. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00174.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levy G, Fishman JE, Xu D, Chandler BT, Feketova E, Dong W, Qin Y, Alli V, Ulloa L, Deitch EA. Parasympathetic stimulation via the vagus nerve prevents systemic organ dysfunction by abrogating gut injury and lymph toxicity in trauma and hemorrhagic shock. Shock. 2013;39(1):39–44. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31827b450d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Magnotti LJ, Upperman JS, Xu DZ, Lu Q, Deitch EA. Gut-derived mesenteric lymph not portal blood increases endothelial cell permeability and promotes lung injury after hemorrhagic shock. Ann Surg. 1998 Oct;228(4):518–27. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199810000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poggetti RS, Moore FA, Moore EE, Koeike K, Banerjee A. Simultaneous liver and lung injury following gut ischemia is mediated by xanthine oxidase. J Trauma. 1992;32(6):723–7. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199206000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McQuigan M, Kozar RA, Moore FA. Enteral glutamine during active shock resuscitation is safe and enhances tolerance. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2008;32(1):28–35. doi: 10.1177/014860710803200128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wischmeyer PE, Dhaliwal R, McCall M, Ziegler TR, Heyland DK. Parenteral glutamine supplementation in critical illness: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2014 Apr 18;18(2):R76. doi: 10.1186/cc13836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heyland DK, Muscedere J, Wischmeyer PE, Cook D, Jones G, Albert M, Elke G, Berger MM, Day AG Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. A randomized trial of glutamine and antioxidants in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(16):1489–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1212722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heyland DK, Elke G, Cook D, Berger MM, Wischmeyer PE, Albert M, Muscedere J, Jones G, Day AG on behalf of the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. Glutamine and Antioxidants in the Critically Ill Patient: A Post Hoc Analysis of a Large-Scale Randomized Trial. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014 May 5; doi: 10.1177/0148607114529994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van den Berghe G. Low glutamine levels during critical illness- adaptive or maladaptive? N Engl J Med. 2013;368(16):1549–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1302301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heyland DK, Dhaliwal R. Role of glutamine supplementation in critical illness given the results of the REDOX study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2013;37(4):442–3. doi: 10.1177/0148607113488421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garrel D, Patenaude J, Nedelec B, Samson L, Dorais J, Champoux J, D’Elia M, Bernier J. Decreased mortality and infectious morbidity in adult burn patients given enteral glutamine supplements: A prospective, controlled, randomized clinical trial. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:2444–2449. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000084848.63691.1E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou Y, Jiang ZM, Sun YH, Wang XR, Ma EL, Wilmore D. The effect of supplemental enteral glutamine on plasma levels, gut function, and outcome in severe burns: a randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2003;27:241–245. doi: 10.1177/0148607103027004241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]