Abstract

Objective

Characterizing burn sizes that are associated with an increased risk of mortality and morbidity is critical because it would allow identifying patients who might derive the greatest benefit from individualized, experimental, or innovative therapies. Although scores have been established to predict mortality, few data addressing other outcomes exist. The objective of this study was to determine burn sizes that are associated with increased mortality and morbidity after burn.

Design and Patients

Burn patients were prospectively enrolled as part of the multicenter prospective cohort study, Inflammation and the Host Response to Injury Glue Grant, with the following inclusion criteria: 0–99 years of age, admission within 96 hours after injury, and >20% total body surface area burns requiring at least one surgical intervention.

Setting

Six major burn centers in North America.

Measurements and Main Results

Burn size cutoff values were determined for mortality, burn wound infection (at least two infections), sepsis (as defined by ABA sepsis criteria), pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and multiple organ failure (DENVER2 score >3) for both children (<16 years) and adults (16–65 years). Five-hundred seventy-three patients were enrolled, of which 226 patients were children. Twenty-three patients were older than 65 years and were excluded from the cutoff analysis. In children, the cutoff burn size for mortality, sepsis, infection, and multiple organ failure was approximately 60% total body surface area burned. In adults, the cutoff for these outcomes was lower, at approximately 40% total body surface area burned.

Conclusions

In the modern burn care setting, adults with over 40% total body surface area burned and children with over 60% total body surface area burned are at high risk for morbidity and mortality, even in highly specialized centers.

Keywords: burns, survival, cutoff, morbidity, outcomes

INTRODUCTION

Burn injury isunique in thatinjury severity can be quantified, enabling the use of formulas to predict survival(1).Predicting survival is a key aspect guidingburn care choices(1-3).Baux’s score, which was established in the mid-20th century, has been used to determine burn outcomes. Later on, during 1980–1990, various formulas based on burn size were developed to guide clinical treatment decisions(2, 4-6).Ryan etal.(6)identified risks factors and developed a model for predicting poor outcomebased on a retrospective analysis of data from 1,665 burn patients treated between 1990 and 1996.Features of the injury, along with initial treatment and biochemical markers atadmission and during hospitalization, were included in this model.Recently, a review by Hussain and colleagues(1)revealed that, of all prediction models, only a few actually predict mortality reasonably well.

While predicting survival is important, a substantial difference exists between predicting mortality and the burn size predictive of morbidity(7).Cutoff values are burn sizes that, at admission,can discriminate whether a patient with a given burn size is at risk for significant complications(7). From a practical point of view, this burn size threshold should identify patients requiring specific interventions (e.g., early initiation of antibiotics, anabolic agents, or anti-catabolic agents; more aggressive surgery, or use of innovative therapies)(8).We have recently shown that,in a large pediatric cohort,the cutoff burn size linked to greater complications and death morbidity and mortality in a specialized burn center is approximately 60% total body surface area (TBSA) burned(7). This study was a single-center study and included only pediatric patients. Todate, there are significant gaps in our knowledge of predictors of adverse outcomes after massive burns. This prospective cohort study was undertakenin six major US burn centers to determine the burn sizeassociated with increased risks of morbidity and mortality.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

This study was part of the Inflammation and the Host Response to Injury Glue Grant and was approved by Institutional Review Boards of the participating institutions (University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX; Loyola University Medical College, Chicago, IL; University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, TX; University of Washington Seattle, Seattle, WA;Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA). Over an 8-year period, 573 patients meeting all inclusion criteria were prospectively enrolled. Inclusion criteria were as follows:age of 0–99years, admissionto a participating hospital no later than96 hours postburn, >20% TBSA burns with the need for at least one surgical intervention. All hospitals followedstandard operating procedures set forth by the burn patient-oriented research core(9, 10).Each subject or a family member provided written informed consent before study participation. Demographics, injury characteristics (date of burn and admission, burn size and depth, presence of inhalation injury), and outcomes (infection, complications, and death) were recorded throughout hospitalization.

Outcomes

The primary objective of the study was to identify the cutoff burn size for mortality. Secondary objectives included determining cutoff burn size for incidence of infections, sepsis, and multiple organ failure (MOF).Severity of disease was quantifiedusing the APACHE II score(11, 12) and the Denver 2 MOFscore(13, 14). We comparedthe incidence of nosocomial infections, burn wound infections, pneumonias, positive blood cultures, urinary infections, abdominal compartment syndrome, acute respiratory distress syndrome, cardiac arrests, atrial arrhythmias, and cerebral infarctions and determined the cutoff burn size. Mortalitywas recorded as incidence, primary cause, and place of death up to 365 days after burn.

Disease severity scores

The APACHE II scoredata presented pertains to the APS (Acute Physiology Score) component of APACHE II, which assesses the degree of physiologic derangement within 24 hours post-injury. This score includes heart rate, respiratory rate, alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient, sodium, potassium, creatinine, white blood cell count, and Glasgow coma scale. The Baux score was calculated as the sum of age and TBSA burned. The Denver 2score reflects patient status duringthe first 24 hours and is the sum of the following:pulmonary score (ranging from 0–3, using PaO2/FiO2 cutoffs of 100, 175, 250), renal score (0–3, using creatinine cutoffs of 1.8, 2.5, 5.0 mg/dL), hepatic score (0–3, using bilirubin cutoffs of 2., 4.0, 8.0 mg/dL), and cardiac score (0–3, based on number and dosage of inotropes).

Infections(15)

Nosocomial infections weredefined according tocriteria set forth by the Inflammation and Host Response to Injury Glue Grant standard operating protocols met(16).Burn wound infection/contaminationwas defined as a burn wound culture resulting in at least 105 colony forming units (CFUs)/g of tissue.Pneumonia was diagnosed with criteria present within a 48-hour period(15, 16) as previously published(17, 18).

Bloodstream infections were defined positive according to the conditions as previously published(17, 18).Urinary tract infectionswere diagnosed when criteria were present as previously published(17, 18).Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) was diagnosed when all of the following(17, 18)were met within a 24-hour period: bilateral infiltrates (acute onset), PaO2/FiO2<200 regardless of Positive End Expiratory Pressure (PEEP), and no evidence of left atrial hypertension [Pulmonary Capillary Wedge Pressure (PCWP) <18 if measured] or no evidence of congestive heart failure.

Statistics

We separated the patients into 3 groups based on their age: 0-15, 16-65 and >65 and compared their baseline characteristics and outcomes

Data are presented as means and standard deviation and/or medians and interquartile ranges for continuous variables. Comparisons were performed using a t-tests, Wilcoxon rank sum tests, or ANOVA/Kruskall-Wallis tests, as appropriate. Categorical data, whichwere summarized by frequencies and percentages, were compared using the Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. We determined the TBSA burn cutoff point using various approachesfor comparison: Youden’s index that maximizes the distance to the line of equality that is equivalent to maximizing the sum of sensitivity and specificity, minimizing the distance from the ROC plot to the (0,1) point andsimultaneously maximizing sensitivity and specificity.P<0.05 was considered significant. Using the cutoff obtained from these analyses, we performed multiple logistic regression analysis foreach outcome dichotomizing TBSA at the cutoff point and adjusting for age, gender, inhalation injury and early Denver score dichotomize as greater than 2 versus 2 or less. For patients under 16 years of age, due to the low number of events for some outcome and to adhere by the rule of 5-6 events(19)per variable in the model, we restricted the analysis to MOF and at least 2 burn wound infections outcomes. Goodness-of-fit for the logistic regression analysis was assessed using Hosmer-Lemeshow test and linearity in age was inspected by graphs. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 and R version 2.15.1.

RESULTS

Demographics

Of the 573 patients enrolled in this study, 226 were pediatric(<16 years), 324were adults (16–65 years), and 23 patients were elderly(>65 years) (Table 1). Because of the low number of elderly patients, these patients were not included in the cutoff analysis; however,demographic and clinical outcome data for this population are presented in Tables 1 and 2.Burn size and incidence of inhalation injury were greatest in pediatric patients and lowest in elderly patients (p<0.05among groups for burn size, Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics for all patients, children (<16 years), adults (>16 and <65 years), and elderly (>65 years).

| Demographics | All patients n= 573 | Patients <16 years n= 226 | Patients 16-65 years n=324 | Patients >65 years n=23 | p-value comparing <16 vs. 16-65 | p-value comparing the 3 groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age years (Median) | 26 ± 21 (22) | 6 ± 5 (4) | 37 ± 14 (37) | 74 ± 6 (74) | <.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Gender M [n (%)] | 412 (72) | 150 (66) | 251 (77) | 11 (48) | 0.004 | 0.0006 |

| Burn Percent Total % (Median) | 48 ± 20 (45) | 58 ± 18 (56) | 42 ± 19 (37) | 37 ± 16 (33) | <.0001 | <0.0001 |

| 2nd-Degree TBSA % Median (IQR) | 14± 17 8 (0.3-22) | 15 ± 19 6 (0-25) | 14 ± 15 8 (1-21) | 15 ± 14 (10) 10 (2-28) | 0.19 | 0.2735 |

| 3rd-Degree TBSA % (Median) | 34 ± 25 (31) | 43 ± 27 (44) | 29 ± 22 (25) | 22 ± 17 (18) | <.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Inhalation Injury [n (%)] | 264 (46) | 124 (55) | 132 (41) | 8 (35) | 0.0012 | 0.0028 |

| Burn Mechanism | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Flame n (%) | 460 (80) | 171 (76) | 270 (84) | 19 (83) | ||

| Flash n (%) | 26 (5) | 3 (1) | 22 (7) | 1 (4) | ||

| Scald n (%) | 66 (12) | 47 (21) | 16 (5) | 3 (13) | ||

| Other n (%) | 20 (4) | 5 (2) | 15 (4) | NA | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Caucasian n | 226 (39.5) | 28 (12.4) | 179 (55.4) | 19 (82.6) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic n | 246 (43.0) | 178 (78.8) | 68 (21.1) | 0(0) | ||

| African American n | 60 (10.5) | 11 (4.9) | 46 (14.2) | 3 (13.0) | ||

| Others n | 40 (7.0) | 9 (4.0) | 30 (9.3) | 1 (4.4) |

TBSA = total body surface area. Data presented as mean ± SD or percentages.

Table 2.

Clinical Outcome Parameters.

| Characteristics | All patients n=573 | Patients <16 years n=226 | Patients 16 - 65 years n=324 | Patients >65 years n=23 | p- value comparing <16 vs. 16-65 | p-value comparing the 3 groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baux score | 75 ± 23 | 63 ± 18 | 80 ± 21 | 112 ± 16 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Escharatomy n (%) | 136 (24) | 28 (12) | 104 (32) | 4 (17) | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Length of ICU Stay (days) | 34 ± 33 | 31 ± 25 | 36 ± 37 | 35 ± 34 | 0.84 | 0.98 |

| Median (IQR) | 25 (14-42) | 24 (15-37) | 26 (13-44) | 29 (13-52) | ||

| Length of ICU Stay (days)/ TBSA% | 0.72 ± 0.64 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.8 | 0.9 ± 0.7 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Median (IQR) | 0.56 (0.32-0.89) | 0.47 (0.30-0.63) | 0.7 (0.3-1.1) | 0.8 (0.4-1.4) | ||

| Number of ORs n | 5 ± 4 | 5 ± 4 | 5 ± 5 | 5 ± 5 | 0.83 | 0.84 |

| Median (IQR) | 4 (2-7) | 4 (2-6) | 4 (2-7) | 4 (2-5) | ||

| Denver 2 Score | 3 ± 3 | 3 ± 2 | 3 ± 3 | 4 ± 3 | 0.43 | 0.091 |

| Median (IQR) | 2 (0-4) | 2 (0-4) | 2 (0-4) | 3 (2-5) | ||

| APACHE II Score* | 18.5 ± 9.6 | 15 ± 9 | 20 ± 10 | 22 ± 8 | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| MOF n (%) | 155 (27) | 60 (27) | 86 (27) | 9 (39) | 1.00 | 0.41 |

| Ventilation n (%) | 438 (77) | 180 (80) | 241 (74) | 17 (77) | 0.15 | 0.36 |

| ARDS n (%) | 116 (20) | 9 (4) | 101 (31) | 6 (26) | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Cardiac events n (%) | 52 (9) | 8 (4) | 36 (11) | 8 (35) | 0.0013 | <.0001 |

| Abdominal Compartment Syndrome n (%) | 15 (3) | 5 (2) | 9 (3) | 1 (4) | 0.68 | 0.80 |

| VASC n (%) | 30 (5) | 7 (3) | 22 (6.8) | 1 (4) | 0.057 | 0.16 |

| Upper and lower GI bleeds n (%) | 12 (2) | 1 (0.4) | 10 (3) | 1 (4) | 0.032 | 0.030 |

| Shock n (%) | 17 (3) | 0 (0) | 17 (5) | 0 (0) | 0.0005 | 0.0012 |

| Burn wound infection (Y/N) n (%) | 400 (69.8) | 212 (93.8) | 177 (55) | 11 (47.8) | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| At least two burn wound infections n (%) | 337 (58.8) | 193 (85.4) | 136 (42) | 8 (34.8) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Nosocomial Infection | 402 (70) | 153 (67.7) | 230 (71) | 19 (83) | 0.41 | 0.29 |

| Pneumonia n (%) | 181 (32) | 21 (9) | 147 (45) | 13 (57) | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| Sepsis n (%) | 42 (7) | 5 (2) | 31 (10) | 6 (26) | 0.0006 | <.0001 |

| Mortality n (%) | 86 (15) | 18 (8) | 55 (17) | 13 (57) | 0.002 | <.0001 |

TBSA = total body surface area. MOF = multiple organ failure. Data presented as means ± SD or percentages.

40 missing values.

An analysis of clinical data revealed that elderly and adult patients had a significantly greater Baux score than pediatric patients,an expected outcome since these calculations include age as a factor. Pediatric patients had significantly fewer ICU days per percent burn than adult or elderly patients (Table 2). Denver 2 scores did not differamong groups, while APACHE II scores were highest in elderly patients and lowest in pediatric patients (Table 2). As expected, cardiac events were most frequent in elderly patients followed by adults, while vascular events and abdominal compartment syndrome didnot differamong groups (Table 2). The incidence of ventilation was similar among groups, while adults had the greatest incidence of ARDS (Table 2).

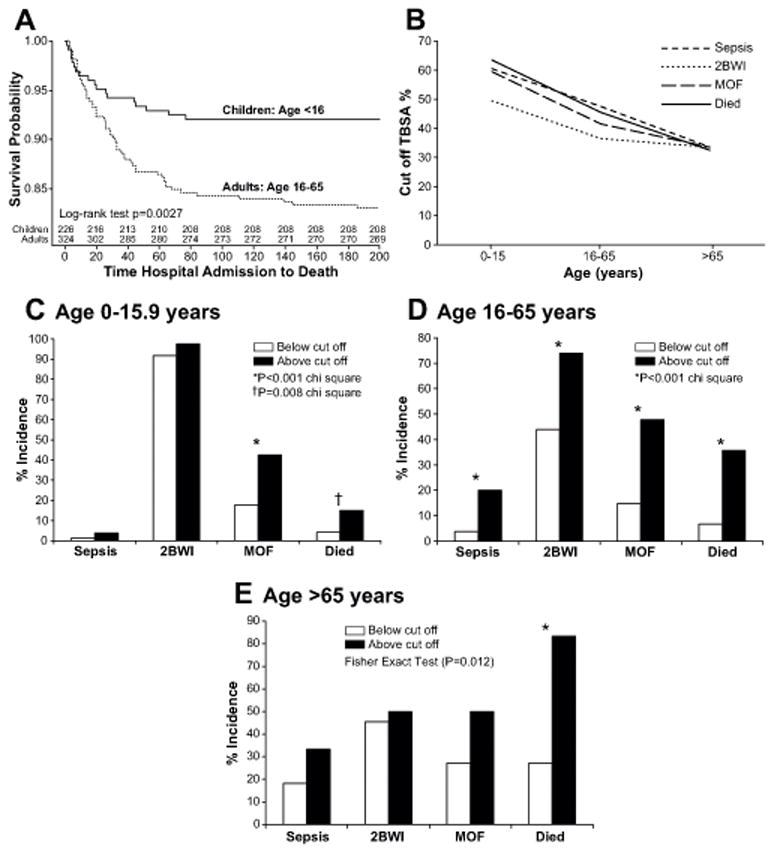

Pediatric patients had a significantly greater incidence of burn wound infections/contaminationsthan adult and elderly patients, but a significantly lower incidence of pneumonia and sepsis (Table 2). On the other hand, the incidence of nosocomial infections was comparable among groups. Mortality was highest in elderlypatients and lowest in pediatric patients (Table 2 and Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) Kaplan Meier survival curve in pediatric and adult patients.Survival probability was greatest in pediatric patients and progressively worse inadult and elderly patients.*Significant difference between pediatric and adult patients p<0.05. (B-E)Cutoff values for sepsis, burn wound infections, MOF and mortality, according to age. (B) The cutoffs for sepsis, burn wound infections, MOF and mortality are greatest in pediatric patientsand then decrease to about 40% TBSA burned in adults and 30% TBSA burned for elderly. (C-E) Incidence of patients with burns below or above the cutoff in the different age groups. *Significant difference between groups, p<0.05.

Cut-off burn size analysis

The cutoff burn sizes that discriminatebetween those who will or will not experience any given adverse outcomeare provided in Tables 3 (pediatric patients) and 4 (adult patients). Youden’s index likely yields the most relevant cutoffs as it maximizes the overall discriminative power of the TBSA burn for the different outcomes.In pediatric patients,the burn cutoffs were as follows: 60% (TBSA burned) for MOF,55% for the presence of at least two burn wound infections/contaminations, 85% for sepsis, 55% for mortality,60% for ARDS, and65% for pneumonia (Table 3).There were very few events for mortality, sepsis, and ARDS. Therefore, the cutoff points for these outcomes may have some variation.

Table 3.

Cut-off calculations in patients under 16 years.

| Outcome | Method | Results percent burn | Events |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | Youden’s index | 54 | 18 |

| Mortality | Distance from the ROC curve to (0,1) | 77 | |

| Mortality | Maximum specificity and sensitivity | 64 | |

| MOF | Youden’s index | 58 | 60 |

| MOF | Distance from the ROC curve to (0,1) | 58 | |

| MOF | Maximum specificity and sensitivity | 60 | |

| ARDS | Youden’s index | 57 | 9 |

| ARDS | Distance from the ROC curve to (0,1) | 66 | |

| ARDS | Maximum specificity and sensitivity | 65 | |

| At least 2 Burn Wound Infections | Youden’s index | 54 | 193 |

| At least 2 Burn Wound Infections | Distance from the ROC curve to (0,1) | 54 | |

| At least 2 Burn Wound Infections | Maximum specificity and sensitivity | 51 | |

| Sepsis | Youden’s index | 85 | 5 |

| Sepsis | Distance from the ROC curve to (0,1) | 85 | |

| Sepsis | Maximum specificity and sensitivity | 62 | |

| Pneumonia | Youden’s index | 64 | 21 |

| Pneumonia | Distance from the ROC curve to (0,1) | 64 | |

| Pneumonia | Maximum specificity and sensitivity | 65 |

MOF = multiple organ failure; ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; ROC = receiver operating characteristic.

For adult patients, the cutoff burn size for MOF was around 50% TBSA burned (Table 4). The cutoff for at least two burn wound infections/contaminations was around 45% TBSA, while the cutoff for sepsis was also around 50% TBSA burned. Mortality had a cutoff of approximately 54% TBSA burned.For pneumonia and ARDS, the cutoff was about 35% TBSA burned. These results indicate that the burn size associated with an increased risk for severe morbidity is approximately 40–50% TBSA burned. In fact, when these cutoffs were added to various models, we found that they were significantly associated with their respective outcomes (data not shown). Looking at our cutoff from a different angle, Figure 1 B-E depicts the incidence of patients with burns below or above the cutoff in the different age groups.

Table 4.

Cutoff calculations in patients between 16 and 65 years.

| Outcome | Method | Results percent burn | Events |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | Youden’s index | 44 | 55 |

| Mortality | Distance from the ROC curve to (0,1) | 44 | |

| Mortality | Maximum specificity and sensitivity | 46 | |

| MOF | Youden’s index | 4.8 | 86 |

| MOF | Distance from the ROC curve to (0,1) | 4.8 | |

| MOF | Maximum specificity and sensitivity | 43 | |

| ARDS | Youden’s index | 35 | 101 |

| ARDS | Distance from the ROC curve to (0,1) | 39 | |

| ARDS | Maximum specificity and sensitivity | 40 | |

| At least 2 Burn Wound Infections | Youden’s index | 43 | 136 |

| At least 2 Burn Wound Infections | Distance from the ROC curve to (0,1) | 43 | |

| At least 2 Burn Wound Infections | Maximum specificity and sensitivity | 3.9 | |

| Sepsis | Youden’s index | 48 | 31 |

| Sepsis | Distance from the ROC curve to (0,1) | 48 | |

| Sepsis | Maximum specificity and sensitivity | 48 | |

| Pneumonia | Youden’s index | 35 | 147 |

| Pneumonia | Distance from the ROC curve to (0,1) | 35 | |

| Pneumonia | Maximum specificity and sensitivity | 38 |

MOF = multiple organ failure; ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; ROC = receiver operating characteristic.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to determine cutoff burn sizes linkedto severe adverse outcomes(sepsis, infection, MOF, and mortality) in burn patients in a multicenter setting. Predictors of survivalwere not analyzed, as this was done in various previous trials.The strength of this work is that it was carried out bysix state-of-the-art burn centers following the same treatment protocols. Therefore,these findingsmay be applicable to other burn centers in North America or even globally. Another major strength is the validity of the burn size assessment and that all of the collected data were validated.We found that pediatric patients had the best survival, with survival being progressively worse inadult and elderly patients. This is not surprising and confirms various previous outcome trials(6). The majority of elderly patients die within the 60–70 days after burn. Because such a low number of elderly patients were enrolled in this trial,they were excluded from the in-depth analysis. However, we can assume that the elderly have a much lower cutoff value for major complications and mortality than adults.

In this study, the pediatric subgroup was dominated by Hispanics and the adult subgroup by Caucasians. This is due to the fact thatthe majority of pediatric patients were enrolled by the Galveston Shriners Hospital and the majority of these patients are from central and south America. Whether ethnicity affects the cutoff value is not entirely clear, but none of the children had preexisting medical conditions or metabolic alterations, which are prevalent in the Hispanic population. Although a small percentage of these children were obese, as detailed in an earlier publication(17), obesity-related complications were not manifested at the time of injury. Interestingly, differences existedamong groups in gender, burn size, and incidence of inhalation injury. Pediatric patients had the largest burn size and highest incidence of inhalation injury compared to adult and elderly patients.However, because we analyzed the cutoff burn sizes within groups,we did not adjust for injury severity. Pediatric patients had the lower Baux score, shortest length of ICU stay, and lowest APACHE II score. This was expected given that age is factored into some of these equations(1, 3, 11, 12). Pediatric patients also exhibited thequickest wound healing, as reflected by shorter ICU stays. Children stayed in the ICU an average of 0.5 daysper percent burn, which is remarkably short. In contrast, adults stayed 1 day per percent burn. It is worth noting thatlength of stay used to be almost 2 days per percent burn(20), indicating that the implementation of protocolized care hasshortened hospitalization.

Here, MOF was present in 27% of pediatric and adult patients, but in 40% of elderly patients. One may speculate that children recover from MOF better than adults, as death was more than double in adults (8% in pediatric vs.17% of adult patients). These findings are in agreement with a recent single center trial showing the outcomes are dependent on the number of organs failing and which organ is failing(21).Even more fascinating, however,is that almost all pediatric patients had burn wound infections/contaminations (94% of the patients), while only 55% of adults had burn wound infections/contaminations (Table 2). This difference could be true or it could bea reflection of the differences in standard of care at the pediatric hospital compared to the adult burn units. Burn wounds on the pediatric patients are routinely biopsied 3 times per week and during operations. Standard of care in the adult burn units, however, tends to include biopsying during operations at the discretion of the treating physician. Higher incidence of burn wound infections/contaminations in the pediatric patients may be a factor of where the patients are from. While many of the children are from rural Mexico, frequently living in substandard conditions, the adults are mainly from urban areas of the US. In addition, only 2% of pediatric patients had signs of sepsis while 10% of adults had sepsis. These data suggest that pediatric burn patients are better able to contain infections and/or contaminations, while burn wound infections in adult patients lead to systemic sepsis. This is most likely due to the differences in the immune system(22), which plays a central role in controlling infections and preventing escalation to sepsis. Pediatric patients likely have a better immune system than adults and the elderly, the latter of which had the highest incidence of sepsis (26%). Lower sepsis in pediatric patients may also be attributable to differences in the inflammatory response after burn. Finnerty et al.(9)have shown that the inflammatory response differs between adult and pediatric burn patients, with the latter havinglessinflammatory stress. This suggeststhat hyper-inflammation leads to a higher incidence of sepsis.

As already mentioned, cutoff analysis was not performed for elderly patients due to the small sample size, which would notallow for a valid statistical analysis. Nevertheless, analysis of pediatric and adult burn patients revealed that pediatric patients had the highest cutoff burn size values: 60% TBSA burned for mortality, 60% TBSA burned for MOF, 50% TBSA burned for burn wound infections, and around 70–80% TBSA burned for sepsis.Supporting our findings is a recent study showing that 60% TBSA burned is a crucial burn size in pediatric patients leading to greater complications and mortality. Furthermore, we found that adult burn patients had a cutoff burn size of 44% for mortality, 46% for MOF, 42% for burn wound infections, and 49% for sepsis. Taken together, these results indicate that,in adult burn patients, 40-45% TBSA burns represent a crucial cutoff value for substantially increased risk of developing adverse outcomes.

One must keep in mind that all these cutoffs are calculated in high-volume burn specialty centers. Therefore, the cutoff burn size would most likely be even lower for low-volume, non-specialized burn units or centers. Additionally, this study was not meant to create dichotomy, meaning that burn patients with smaller burn do not die. Burn patients, adults and children, even with smaller burns also have a risk of morbidities and mortality. The cutoffs in this study indicate the burn size in high volume centers that is associated with increased risk of morbidity and death. Thirdly, this paper cannot be used as a bench mark in terms of legal aspects or quality improvement initiative for the same reasons that are aforementioned. Fourth, we are not saying that only burn over the cutoff should be treated in specialized centers. Burn patients have very well-established admission criteria set by the American Burn Association and American College of Surgeons. These criteria are the main criteria for admissions to burn centers. The data presented within the paper are by no means meant to be burn sizes serving as admissions indications. Lastly, this is a prospectively collected database of over 500 patients as part of a multi-center trial. There are databases that have substantially more patients and could be used for burn size cutoffs in terms of acute outcomes (NTRACS) or long-term outcomes (NIDRR). These databases have a lot more patients and therefore a lot more power than this study.Another limitation of this study (that might in fact be advantageous) isthat enrollment was biased toward survivors(10).That is, predicted fatal outcome on admission was anexclusion criterion, setting a true cutoff because all enrolled patients were expected to survive as predicted by the treating physician. Another limitation is the potential generalizability of our findings, given the evidence-based nature of the care provided and the degree of standardization across centers. Treatment protocols were developed for this study, and therefore, care of burn patients in the multicenter setup was similar.

In summary, the current findingsconfirmthe greatermortality and complicationsexpected withincreasing burn size, with a significant discrimination being noted at around 60% TBSA burned for pediatric patients and around 40% TBSA burned for adult burn patients. Elderly patients had the lowest survival cutoff at around 30% TBSA, but the results from this trial are non-conclusive because of low patient numbers. These results are important, as theyindicate a threshold for post-burn morbidity and mortality in the modern burn care setting to be approximately 60% TBSA burned in pediatric patients and 40% TBSA burned for adult patients. These findings show that patients with burns at or above these cutoff values are at high risk for substantial complications and death, even in highly specialized centers; keeping in mind that the risk for morbidity and mortality increases in a linear fashion meaning the larger the burn the higher the risk. These thresholds should raise awareness about the profound risks for postburn morbidity and mortalityand should be used to identify patients that would benefit from individualized treatments or even experimental interventions.

To put our findings into context, we showed that the crucial threshold for postburn morbidity and mortality in the modern burn care setting to be approximately 60% TBSA burned in pediatric patients and 40% TBSA burned for adult patients. These findings show that patients with burns at or above these cutoff values are at high risk for substantial complications and death, even in highly specialized centers. These thresholds should raise awareness about the profound risks for postburn morbidity and mortality and should be used to identify patients that would benefit from individualized treatments or even experimental interventions.

Acknowledgments

The magnitude of the clinical data reported here required the efforts of many individuals at participating institutions. In particular, we wish to acknowledge the supportive research environment created and sustained by the participants in the Glue Grant Program: Henry V. Baker, Ph.D., Ulysses G.J. Balis, M.D., Paul E. Bankey, M.D., Ph.D., Timothy R. Billiar, M.D., Bernard H. Brownstein, Ph.D., Steven E. Calvano, Ph.D., David G. Camp II, Ph.D., Irshad H. Chaudry, Ph.D., J. Perren Cobb, M.D., Joseph Cuschieri, M.D., Ronald W. Davis, Ph.D., Asit K. De, Ph.D., Bradley Freeman, M.D., Brian G. Harbrecht, M.D., Douglas L. Hayden, M.A., Laura Hennessy, R.N., Jeffrey L. Johnson, M.D., James A. Lederer, Ph.D., Stephen F. Lowry, M.D., Ronald V. Maier, M.D., John A. Mannick, M.D., Philip H. Mason, Ph.D., Grace P. McDonald-Smith, M.Ed., Carol L. Miller-Graziano, Ph.D., Michael N. Mindrinos, Ph.D., Joseph P. Minei, M.D., Lyle L. Moldawer, Ph.D., Ernest E. Moore, M.D., Grant E. O’Keefe, M.D., M.P.H., Daniel G. Remick, M.D., Laurence G. Rahme, Ph.D., David A. Schoenfeld, Ph.D., Michael B. Shapiro, M.D., Richard D. Smith, Ph.D., John D. Storey, Ph.D., Robert Tibshirani, Ph.D., Mehmet Toner, Ph.D., H. Shaw Warren, M.D., Michael A. West, M.D., PhD., Rebbecca P. Wilson, B.A., and Wenzhong Xiao, Ph.D.

Source of Funding: This study was supported by a Large-Scale Collaborative Research Grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (U54 GM62119) awarded to Ronald G. Tompkins at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA and by research grants awarded to David N. Herndon at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P50 GM060338, R01 GM056687, T32 GM0008256) and Shriners Hospitals for Children (71008, 84080) as well as to Marc G. Jeschke by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01 GM087285), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (#123336), and CFI Leader’s Opportunity Fund (Project #25407). CCF is an Institute for Translational Sciences Career Development Scholar supported, in part, by KL2RR029875 and UL1RR029876. This study was conducted with the support of the Institute for Translational Science at the University of Texas Medical Branch, supported in part by a Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1TR000071) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science, National Institutes of Health.

Copyright form disclosures: The authors’ institutions received grant support from the National Institutes of Health (U54 GM062119, P50 GM060338, R01 GM056687, T32 GM008256, R01 GM087285, UL1TR000071), Institute for Translational Science at the Univ. of TX Medical Branch ((NIH funds) KL2RR029875, UL1RR029876), Shriners Hospitals for Children (71008, 84080), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (123336), and CFI Leader’s Opportunity Fund (Project #25407); received support for article research from the NIH (This study was supported by a Large-Scale Collaborative Research Grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (U54 GM62119) awarded to Ronald G. Tompkins at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA and by research grants awarded to David N. Herndon at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P50 GM060338, R01 GM056687, T32 GM0008256) and Shriners Hospitals for Children (71008, 84080) as well as to Marc G. Jeschke by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01 GM087285), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (#123336), and CFI Leader’s Opportunity Fund (Project #25407). CCF is an Institute for Translational Sciences Career Development Scholar supported, in part, by KL2RR029875 and UL1RR029876. This study was conducted with the support of the Institute for Translational Science at the University of Texas Medical Branch, supported in part by a Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1TR000071) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science, National Institutes of Health).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest Authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Hussain A, Choukairi F, Dunn K. Predicting survival in thermal injury: A systematic review of methodology of composite prediction models. Burns. 2013 Feb 2; doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2012.12.010. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bull JP, Squire JR. A study of mortality in a burns unit: standards for the evaluation of alternative methods of treatment. Ann Surg. 1949;130:160–173. doi: 10.1097/00000658-194908000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts G, Lloyd M, Parker M, et al. The Baux score is dead. Long live the Baux score: a 27-year retrospective cohort study of mortality at a regional burns service. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:251–256. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31824052bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choiniere M, Dumont M, Papillon J, et al. Prediction of death in patients with burns. Lancet. 1999;353:2211–2212. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02401-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Germann G, Barthold U, Lefering R, et al. The impact of risk factors and pre-existing conditions on the mortality of burn patients and the precision of predictive admission-scoring systems. Burns. 1997;23:195–203. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(96)00112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryan CM, Schoenfeld DA, Thorpe WP, et al. Objective estimates of the probability of death from burn injuries. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:362–366. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802053380604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kraft R, Herndon DN, Al-Mousawi AM, et al. Burn size and survival probability in paediatric patients in modern burn care: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet. 2012;379:1013–1021. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61345-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeschke MG, Chinkes DL, Finnerty CC, et al. Pathophysiologic response to severe burn injury. Ann Surg. 2008;248:387–401. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181856241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finnerty CC, Jeschke MG, Herndon DN, et al. Temporal cytokine profiles in severely burned patients: a comparison of adults and children. Mol Med. 2008;14:553–560. doi: 10.2119/2007-00132.Finnerty. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein MB, Silver G, Gamelli RL, et al. Inflammation and the host response to injury: an overview of the multicenter study of the genomic and proteomic response to burn injury. J Burn Care Res. 2006;27:448–451. doi: 10.1097/01.BCR.0000227477.33877.E6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, et al. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osler T, Glance LG, Hosmer DW. Simplified estimates of the probability of death after burn injuries: extending and updating the baux score. J Trauma. 2010;68:690–697. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181c453b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore FA, Sauaia A, Moore EE, et al. Postinjury multiple organ failure: a bimodal phenomenon. J Trauma. 1996;40:501–512. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199604000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sauaia A, Moore FA, Moore EE, et al. Early risk factors for postinjury multiple organ failure. World J Surg. 1996;20:392–400. doi: 10.1007/s002689900062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenhalgh DG, Saffle JR, Holmes JH., 4th American Burn Association consensus conference to define sepsis and infection in burns. J Burn Care Res. 2007;28:776–790. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181599bc9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klein MB, Hayden D, Elson C, et al. The association between fluid administration and outcome following major burn: a multicenter study. Ann Surg. 2007;245:622–628. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000252572.50684.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeschke MG, Finnerty CC, Emdad F, et al. Mild obesity is protective after severe burn injury. Ann Surg. 2013;258:1119–1129. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182984d19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finnerty CC, Jeschke MG, Qian WJ, et al. Determination of burn patient outcome by large-scale quantitative discovery proteomics. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:1421–1434. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827c072e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vittinghoff E, McCulloch CE. Relaxing the rule of ten events per variable in logistic and Cox regression. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:710–718. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thombs BD, Singh VA, Halonen J, et al. The effects of preexisting medical comorbidities on mortality and length of hospital stay in acute burn injury: evidence from a national sample of 31,338 adult patients. Ann Surg. 2007;245:629–634. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000250422.36168.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kraft R, Herndon DN, Finnerty CC, et al. Occurrence of multiorgan dysfunction in pediatric burn patients: incidence and clinical outcome. Ann Surg. 2014;259:381–387. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31828c4d04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiu F, Jeschke MG. Perturbed mononuclear phagocyte system in severely burned and septic patients. Shock. 2013;40:81–88. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318299f774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]