Abstract

High school teachers evaluate and offer guidance to students as they approach the transition to college based in part on their perceptions of the students' hard work and potential to succeed in college. Their perceptions may be especially crucial for immigrant and language-minority students navigating the U.S. educational system. Using the Educational Longitudinal Study of 2002 (ELS:2002), we consider how the intersection of nativity and language-minority status may (1) inform teachers' perceptions of students' effort and college potential, and (2) shape the link between teachers' perceptions and students' academic progress towards college (grades and likelihood of advancing to more demanding math courses). We find that teachers perceive immigrant language-minority students as hard workers, and that their grades reflect that perception. However, these same students are less likely than others to advance in math between the sophomore and junior years, a critical point for preparing for college. Language-minority students born in the U.S. are more likely to be negatively perceived. Yet, when their teachers see them as hard workers, they advance in math at the same rates as nonimmigrant native English speaking peers. Our results demonstrate the importance of considering both language-minority and immigrant status as social dimensions of students' background that moderate the way that high school teachers' perceptions shape students' preparation for college.

Keywords: Teachers' perceptions, immigrants, language-minority, American Dream, grades, college preparation

1. Introduction

Teachers' perceptions of their students' academic effort and potential are crucial for shaping students' academic outcomes. However, teachers' views of their students may be limited by their ability to understand who their students are and to connect with them. This process may be more complicated for the growing population of newcomers to U.S. schools. Many immigrant parents cite opportunities for their children in U.S. schools as a central part of their “American Dream,” but teachers may have less familiarity with students whose backgrounds are culturally or linguistically different (Hagelskamp et al., 2010; Portes and Rumbaut, 2001; Suárez-Orozco et al., 2008). If teachers' perceptions of whether students have what it takes to succeed in U.S. schools are influenced by their status as language-minority or as immigrants, then these students' opportunities may be different from those of their peers.1 As greater numbers of these students approach the critical moment of the transition to college, relational aspects of schooling between immigrant and language-minority students and influential others are increasingly relevant to conversations about postsecondary opportunity. This paper addresses when and how teachers may act as gatekeepers of the American Dream for immigrant and language-minority students by examining how teachers' perceptions of these students shape their grades and chances of course advancement compared with nonimmigrant native English speakers. By understanding how teachers' perceptions affect outcomes for immigrants and language- minority students, we further our understanding of how interpersonal classroom dynamics affect student outcomes for a rapidly growing segment of our population at an important milestone.

Although immigrant students often have more ambitious educational goals and greater optimism about their futures than their native-born peers, they experience mixed academic outcomes (Alba and Nee, 2003; Glick and White, 2004; Portes and Rumbaut, 2001; White and Glick, 2009; Zhou, 1997). The disjuncture between goals and outcomes for some language-minority and immigrant students reveals the challenges that schools face as they try to help these students translate their ambitions into academic success. Language-minority and immigrant status are two dimensions by which these students may be socially distinct from their classmates that teachers may implicitly or explicitly consider when thinking about students or advising them (Hachfeld et al., 2010). Teachers may reward students they view as promising and hardworking with higher grades and guidance toward demanding college-preparatory coursework (Kelly, 2008; Lleras, 2008; Muller et al., 1999; Rosenbaum, 2001). In turn, students may respond to positive perceptions with increased engagement and higher aspirations (Carbonaro, 2005; Jussim and Harber, 2005; Weinstein, 2002). As newcomers to the U.S., immigrant and language-minority students may be especially likely to rely on teachers' and other in-school authority figures' perceptions of them as they navigate the American educational system (Green et al., 2008; Kao and Tienda, 1995; Pong et al., 2005; Stanton-Salazar and Dornbusch, 1995; Suárez-Orozco et al., 2009; Valenzuela, 1999). Teachers' perceptions of immigrant and language-minority students may help explain why these students are less successful than others at transforming their high ambitions into high achievement.

With this study, we consider the intersection of language-minority and immigrant status and analyze how teachers' perceptions shape students' academic outcomes just before the transition to college. Students' academic opportunities and experiences as sophomores help define their ultimate level of college preparation by determining, for example, whether they will complete critical courses such as Algebra 2 (Schneider et al., 1998; Sutton et al., 2013). By contrasting different students' grades and likelihood of advancing to more demanding college preparatory coursework, we analyze how teachers' evaluations of whether or not students have what it takes to succeed in college correspond with students' accumulation of the credentials necessary to not only get through courses but also to get ahead and move on to college. Further, we consider not only how nativity and language-minority status inform teachers' perceptions of their students but also how the intersection of these social dimensions may shape processes that link teachers' perceptions to students' academic achievement. This approach pushes our analysis past identifying differences in the implications of perceptions between students based on their nativity and native language and toward understanding how and why these students' academic outcomes may be particularly shaped by teachers' views. In doing so, it informs perspectives on the role of teachers in the transition to college more broadly.

2. Background

Immigrants and language-minority students each comprise about one fifth of the U.S. student population, figures that are expected to increase in coming decades (Aud et al., 2010; Klein et al., 2004; Rong and Preissle, 2008). However, as Tillman and others have argued, exclusive focus on academic indicators such as attainment or achievement for immigrants “mask[s] important differences in the processes through which immigrant and nonimmigrant children navigate the educational system,” (Tillman et al., 2006, p. 130; Watkins and Melde, 2010). The same may be true of language-minority students, the majority of whom have immigrant parents (85%) and were born in the U.S. (63%) (Klein et al., 2004). Despite strong evidence that supportive teachers facilitate academic success for immigrant and language-minority students, there is mixed evidence about how teachers perceive them.

2.1 Teachers' Perceptions of Immigrant and Language-Minority Students

The existing research suggests that teachers perceive students from immigrant households as having positive attitudes toward school as well as more self discipline and respect for their teachers, compared with other students (Dabach, 2011; Matute-Bianchi, 1986). However, teachers expect these qualities to decline and they hold more pessimistic expectations for their educational attainment (Suárez-Orozco et al., 2008, p. 134). Further, teachers may view these newcomers as less academically capable since they are often placed into lower-level courses taught by less experienced teachers with lower expectations (Callahan, 2005; Kasinitz et al., 2008; Katz, 1999). In a mixed-methods study of immigrant students' incorporation into U.S. schools, Suárez-Orozco and others found that “96 percent reported that family members expected them to get high grades, whereas only 18 percent reported that people in school or at after-school sites held these expectations for them” (2008, p. 86). By contrast, although many of the children of immigrants in a recent study in New York City described prejudice and discrimination from teachers, some Asian immigrants described anxiety as a response to teachers' expectations that they conform to “model minority” stereotypes (Kasinitz et al., 2008, p.157-160). Overall, although immigrant students and their families seem to hold exceptionally high educational aspirations, their teachers express reservations and in some cases stereotypes about their potential to succeed academically.

Language-minority students face a distinct set of challenges in U.S. schools. While some scholars have argued that bilingualism contributes to academic success (Portes and Rumbaut, 2001), others argue that it may indicate real or perceived cultural and ideological differences and hinder students' ability to form strategic institutional ties with teachers (Stanton-Salazar and Dornbusch, 1995, p. 117). Rumberger and Larson note that “there is a widespread belief among educators, policymakers, and the public at large that English-language proficiency is the key to improving the educational success of immigrant and language-minority students” (1998, p. 68; see also Pavlenko, 2002). Often, rather than perceiving facility in another language as an asset, teachers frame it as an obstacle, particularly for nonimmigrant students (Valenzuela, 1999). Taken together, these patterns suggest tension between nativity and language status in how teachers evaluate and guide their students. In summary, the existing evidence indicates that teachers perceive immigrant students as hardworking but with modest long-term educational prospects, and teachers' perceptions of language-minority students have consistently been shown to be even more negative.

Immigrant families place tremendous faith in the capacity of U.S. schools to realize students' potential. Occupying a key role within these institutional settings, teachers have the potential to facilitate students' upward mobility or alternatively, to act as gatekeepers and reproduce inequality. Specifically, teachers' subjective views on whether or not their immigrant and language-minority students are “college material” may be one factor in how these students are evaluated and sorted into college preparatory coursework just prior to the transition to college. Our argument is twofold: First, language status and nativity intersect in ways that shape high school teachers' perceptions of the effort and college potential of their students. Second, we argue that teachers' perceptions are particularly relevant for the secondary school outcomes of these growing populations because of teachers' potentially pivotal roles as institutional actors shaping students' trajectories within schools.

2.2 Teachers' Perceptions and the American Dream

Teachers evaluate their students along several dimensions, including their effort and potential, two central tenants of the American Dream of achieving success through hard work. A rich literature has documented how daily interactions solidify teachers' initial perceptions of their students, including whether a student has what it takes to succeed academically (Brophy, 1983; Rist, 1970). Teachers' perceptions reflect students' academic ability and behavior, and they also reflect social factors. Some social factors may be noncognitive skills; students' capacity to work hard, take on new challenges, persevere through setbacks, and to work well with their peers have all been shown to shape student outcomes (DiPrete and Jennings, 2012; Jussim and Harber, 2005; Lleras, 2008). In summarizing over three decades of research on teachers' expectations, Jussim and Harber (2005) conclude that teachers' perceptions are generally accurate, meaning that differences in teachers' perceptions based on students' background characteristics—such as race/ethnicity, class, and gender—correspond to measurable differences in students' academic motivation and achievement (Madon et al., 1998). From this perspective, teachers' perceptions are fundamentally meritocratic and reflect their students' capacity to work hard and to maximize their potential through schools.

However, substantial research on the role of teachers in the reproduction of inequality challenges this claim's accuracy, especially in cases where students and teachers are from different social backgrounds. Perceptions are inherently subjective and thus vulnerable to biases and prejudices. Various scholars have discussed how teachers' subjective interpretations arise. Some have emphasized cultural capital, arguing that students familiar with styles and dispositions preferred by teachers and other institutional agents will have better academic outcomes (Bourdieu, 1977; Downey and Pribesh, 2004; Gaddis, 2013). Other theoretical explanations for subjectivity in teachers' perceptions point to power differences between teachers and students, particularly students who are distant from teachers in terms of social status or background (McKown and Weinstein, 2008; Oates, 2003; Saft and Pianta, 2001; van den Bergh et al., 2010). These arguments primarily position teachers' perceptions as one potential mechanism of social reproduction embedded within schools.

Thus far, we have developed a rationale for examining differences in teachers' perceptions of whether or not immigrant and language-minority students have what it takes to get ahead. Further, a number of factors may influence how students' backgrounds contribute to teachers' perceptions of students' effort and college potential. Much of the literature on how students' backgrounds influence teachers' perceptions has focused on students who are members of ethnic or racial minorities or who come from families of low socioeconomic status (SES). Consequently, we know much less about teachers' roles in shaping the academic outcomes of newcomers with different linguistic backgrounds. In the next section, we describe why these perceptions may be especially consequential for these students.

2.3 Teachers' Perceptions and Students' Academic Outcomes

As students' pursue their educational goals, how their teachers perceive them may be especially crucial for shaping their academic outcomes just prior to the transition to college. Specifically, students' grades and advancement through college preparatory classes – as two distinct dimensions of high schoolers' preparation for college – may be particularly shaped by their teachers' perceptions. As indicators of course mastery, grades reflect teachers' evaluations of students' success in conforming to course expectations (Kelly, 2008; Stiggins and Conklin, 1992). On their own, however, high grades do not necessarily promote students on to more demanding courses.

Advancement from one math course level to the next typically indicates that students not only have succeeded at their current level, but also are prepared for and taking on the challenge of more demanding work as preparation for college (Carbonaro, 2005; Kelly, 2008; 2009). This is particularly true of high school math, which follows a sequence of increasingly demanding courses that typically begins with Algebra 1 and progresses through geometry to Algebra 2 and so on as students prepare for college (Bozick and Ingels, 2007; Riegle-Crumb, 2006; Stevenson et al., 1994). Where most students take four years of English, about half of students do not take four years of high school math. Although the share of high school students taking advanced math courses has increased over the past several decades, racial and ethnic disparities in advanced math course-taking persist: 55% of white students but only 48% of blacks and 37% of Latinos had taken advanced math by the conclusion of high school (Riegle-Crumb and Grodsky, 2010). Thus, math is stratified through course topic and level. By understanding how teachers' perceptions shape students' success in a course and chance of advancing, we further our understanding of relational aspects of student stratification at a key point just before the transition to college.

One mechanism by which teachers' perceptions shape students' outcomes is through teachers' capacity to reward students and push them onward to greater challenges. In general, teachers' perceptions of work habits, including effort, are associated with greater student mastery of course content and higher student grades (Farkas et al., 1990; Kelly, 2008). Teachers may also act as gatekeepers by directing the students that they perceive as hardworking or high-potential toward the demanding courses necessary for college preparation (Gaddis, 2013; Muller et al., 1999; Stanton-Salazar and Dornbusch, 1995). Because the social dynamics between teachers and students are integral to these gatekeeping mechanisms, immigrant and language-minority students may find themselves in a precarious position when it comes to teachers' perceptions. Advancing to more demanding coursework requires both the necessary academic skills and institutional savvy about educational opportunity structures that may be less accessible to immigrant and language-minority students. Because the parents of immigrant and language-minority students often lack first-hand knowledge about higher education in the United States, teachers are a potentially crucial source of information and advice about college prerequisites and application or enrollment processes. Indeed, the teacher's role as “cultural broker” and as an important source of institutional sponsorship and information is well established (Gibson et al., 2004; Kasinitz et al., 2008; Suárez-Orozco et al., 2008).

Teachers' perceptions not only shape how teachers evaluate and guide their students but may also shape the signals to students about their competence and potential (Good and Brophy, 2000; Trouilloud et al., 2006; Weinstein, 2002). Students respond to positive teacher perceptions with more motivation and engagement (Skinner and Belmont, 1993; Wentzel, 1997), which may improve their grades and lead them to enroll in more demanding courses. Also, students who infer that their teachers have positive views of their ability to work hard and succeed in college may be more likely to seek teachers' guidance about academic decisions, including decisions about coursework and college preparation (Stanton-Salazar et al., 2001). Immigrant and language-minority students may be even more sensitive to signals gleaned from their teachers' perceptions for their behaviors, attitudes, and subsequent academic success (Stanton-Salazar et al., 2001; Stanton-Salazar and Dornbusch, 1995). Previous scholars have emphasized that immigrant and language-minority students who enjoy supportive relationships with teachers report greater engagement, and those who sense low expectations or negativity from teachers may become disengaged (Kasinitz et al., 2008; Suárez-Orozco et al., 2008; Valenzuela, 1999). This evidence suggests that positive teachers' perceptions are more crucial for the college preparation of immigrant and language-minority students than their peers. That is, the estimated benefits of positive teacher perceptions may be greater for immigrant and language-minority students, who may be disadvantaged by lower expectations and in need of “cultural brokers” in a way that nonimmigrant native English speaking students typically are not.

3. Research Objectives

Our central research question is “How do teachers' perceptions of the effort and college potential of immigrant and language-minority students shape their grades and likelihood of advancing to more demanding math courses, compared with their nonimmigrant, native English speaking peers?” Therefore, our objective is twofold. First we describe teachers' perceptions of the effort and college potential of immigrant and language-minority students. Next, we examine whether teachers' perceptions mediate the relationship between immigrant and language-minority status and students' academic outcomes (grades and advancing in math). We then consider whether the relationship between teachers' perceptions and students' academic outcomes is different depending on students' immigrant and language-minority statuses. Throughout our analysis, we adopt an intersectional approach in examining the association between students' multidimensional language and nativity backgrounds, their teachers' perceptions, and their academic outcomes in preparation for college.

4. Data and Methods

4.1 Data

Much of what we know about how immigrant and language-minority students' academic outcomes are shaped by their teachers' perceptions comes from regional samples, in-depth qualitative work, and studies limited to immigrant-only samples, often from a small cluster of sending countries (Kasinitz et al., 2008; Katz, 1999; Portes and Rumbaut, 2001; Valdéz, 2001; Valenzuela, 1999). Our study, by contrast, uses data from the Educational Longitudinal Study of 2002 (ELS:2002), a nationally representative survey of more than 16,000 2002 10th graders enrolled at 750 public and private U.S. high schools, beginning in the spring of their sophomore year. Two follow-ups of survey data were collected in 2004 and 2006 and high school transcript data were collected in 2005. In this study, we make use of the base-year and first follow-up surveys as well as the transcript data. For several reasons, this dataset is well suited for evaluating differences in teachers' perceptions and students' academic outcomes for immigrant and language-minority students.

First, ELS:2002 is the most recent nationally representative study of U.S. high school students suitable for this analysis. In addition to the benefits of a large sample size for statistical analysis, ELS:2002 contains oversamples of Hispanics and Asians to facilitate more robust comparisons across groups of language-minority and immigrant students. Further, the scope of the ELS:2002 data collection and its longitudinal design offer rigorous controls to help account for important covariates to teachers' perceptions. These include students' prior academic experiences, math course-taking and grades, school quality indicators, and family background.

Last, the goal of this research is to understand how teachers' perceptions shape students' courses and grades. Since teachers' appraisals of students' effort and potential may vary from subject to subject for a variety of reasons, a desirable feature of ELS:2002 is that it allows researchers to understand teachers' perceptions of students within a specific course context (see Carbonaro, 2005). Math and English teachers were surveyed about each 10th grader as part of ELS:2002 base year survey. High school math course-taking and grades are well known predictors of college success, and they are highly stratified. In this tradition, we focus our analysis around math due to the sequential nature of math course-taking, the central role of math placement for high school course placements in other subjects, and the importance of math course-taking and success for college (Carbonaro, 2005; Gamoran and Mare, 1989; Riegle-Crumb, 2006).2 Additionally, math is a better subject than English for studying language minority status students because some of these students may be in specialized language courses; this is not so for math (Callahan et al., 2010). The subject-specific teacher reports include two aspects of teachers' perceptions – whether the student is (1) a hard worker and (2) is likely to complete college. Taken together, these indicate teachers' views about students' potential.

4.2 Dependent Variables

We focus on two dependent variables to measure academic outcomes: math GPA in 10th grade and whether or not the student advanced to the next level in math in 11th grade. These variables are both measured with information from transcripts that were collected as part of the first follow-up of ELS:2002. 10th grade math GPA ranges from 0.0 (an “F” grade) to 4.0 (an “A” grade). As Riegle-Crumb and Humphries (2012) note, if teachers grade students based in part on their perceptions of students, then our estimates of a potential link between teachers' perceptions and students' GPA is a conservative one.

Math course sequences during high school typically begin with Algebra 1 followed by geometry and Algebra 2 (Kelly, 2009; Riegle-Crumb, 2006; Stevenson et al., 1994). High school students who take advanced math courses, such as Algebra 2, trigonometry, precalculus, and calculus, are best prepared for college and are more likely to persist in college (Adelman, 1999; Gamoran and Hannigan, 2000). Additionally, these course levels may be considered in admissions decisions as an indicator of the student's willingness to work hard and take on new challenges. We code the Classification of Secondary School Course (CSSC) codes from the ELS:2002 high school transcripts to identify which math courses students took as sophomores and juniors. We create a dichotomous measure to identify whether students' junior year course was more advanced than their sophomore course (Bozick and Ingels, 2007; Frank et al., 2008).3 We expect that students perceived by their sophomore year math teachers to be hardworking and likely to complete college will earn higher math grades as sophomores and also will advance to more demanding math courses as juniors.

4.3 Independent variables

We consider nativity and language background together to be the background characteristics of interest for this study. Nativity was reported in the parental surveys collected in the base year of ELS:2002. We consider students born outside the U.S. and in Puerto Rico to be immigrant students. Language-minority status is a composite measure of whether the student was a non-native English speaker, meaning that the first language learned was a language other than English. We operationalize these two dimensions of students' background by combining them into a four-group typology of students: nonimmigrant native English speakers (83.0%); nonimmigrant language-minority students (7.8%); immigrant native English speakers (2.4%); and immigrant language-minority students (6.8%).4

We estimate the effect of math teachers' perceptions of students' academic effort and potential to complete college on students' GPA and course advancement in math. Perception of academic effort is a dichotomous measure from the base-year teacher surveys, which asked, “Does this student usually work hard for good grades in your class?” Teachers responded “yes,” “no,” or “I don't know.” Students whose teachers identified them as hardworking are coded as 1 on this variable and all others are coded as 0 (ref). Teachers also reported how far they expected their students to go in school. Teachers' perceptions of students' academic potential is measured as the math teachers' expectation of whether the student will complete college or obtain a graduate degree (yes=1; no=0, ref). These teachers not only view the student as having what it takes to complete high school and attend college, but they also expect him or her to earn a college degree.

4.4 Control Variables

Throughout the analysis, we make use of a set of control variables that might account for the variations across immigrant and language-minority groups, teachers' perceptions, and our academic outcome variables. We include dummy variables for self-reported race/ethnicity (ref: white) and sex (ref: male). Because teachers' perceptions may reflect not only students' nativity and immigrant status but also their race/ethnicity, we conducted sensitivity analyses in which we replicated our results with a subsample of whites and Latinos only and with whites and Asians only; those findings were consistent with those presented here. Also, because students from more affluent families and with highly educated parents are more likely to earn high grades and take college-preparatory math classes, we measure family background with four dummy variables for parents' educational attainment (ref: parent has a college degree) and the log of parents' income.

Next, we include a set of control variables relating to students' prior academic experiences. To the extent that teachers' perceptions are accurate reflections of students' abilities, students' demonstrated ability in earlier coursework should account for some of the association between teachers' perceptions and the grades that students earn and their likelihood of advancing to more demanding coursework. Therefore, we include dummy variables indicating grade 10 course placement in basic math, Algebra 1, geometry, or Algebra 2 or higher (ref: geometry) as well as an indicator of grade 9 GPA in math.5

We characterize the schools in the sample using a set of measures taken from the administrator surveys collected as part of ELS:2002. Because schools are highly stratified by students' social class and race/ethnicity, we include the percentage of students receiving free or reduced-price lunch, the percentage of minority students enrolled in the school, and the proportion of students whose parents have college degrees. These three measures help identify more privileged schools where teachers may have more favorable perceptions of their students and the students themselves are more likely to earn high grades and take demanding coursework to prepare for college.

4.5 Sample and Analytic Strategy

The base year ELS:2002 cohort includes 16,020 10th graders in 751 schools. Of these, 14,160 students had transcript data regarding 10th grade math classes which provide the information necessary for our dependent variables.6 Next, we retained only those students with available information for our key independent variables. Accordingly, 11,920 of the remaining students had reports of their language-minority status and nativity from parent surveys and of these, 10,120 students had math teachers who completed the teacher reports that included their perceptions of the student. Thus our final analytic sample included 10,120 students attending 711 schools. A weighted comparison of the final analytic sample and the subset of base year students with transcript data available showed that although students in the analysis were more likely to be nonimmigrants, native English speakers, white, with higher SES parents, doing better in school, and more likely to be expected to complete college, the magnitude of these differences was modest. Taken together, our analysis remains focused on high-potential students pursuing college preparation.

We used multiple imputation in SAS to produce five complete datasets and combined the results from each model estimated across the five datasets (Allison, 2002). Following the recommendations of Allison (2002), we used the dependent variables, GPA and advancing in math, to multiply impute independent variables, but did not impute those variables themselves. Therefore, our analysis excluded cases missing data on the dependent variable. Consequently, we based our estimated models of students' GPAs and advancement in math on final sample sizes of 8,840 and 10,120, respectively.7 We used transcript weights to approximate the characteristics for the entire 2002 tenth-grade cohort (Ingels et al., 2007).

Our analysis proceeds in three parts. First, we use our typology of nativity and language-minority status to describe teachers' perceptions of students' effort and potential. This involves a purely descriptive analysis of the bivariate associations between our four-group typology of nativity and language-minority status and teachers' perceptions, students' academic outcomes, and also the students' demographics, family background, previous academic experiences, and school characteristics. Next, our multivariate approach uses ordinary least squares to predict students' 10th grade GPA and logistic regression to predict students' likelihood of advancing to the next level math course. We test whether teachers' perceptions account for differences in student academic outcomes even net of a series of controls. Finally, we model interaction terms between students' immigrant and language-minority status and their teachers' perceptions. We use these interaction terms in conjunction with all other model predictors to identify whether the estimated returns to teachers' perceptions of hard work or college potential are similar or different across groups in terms of grades and advancement in math. All models used the cluster option in SAS to adjust the standard errors for the multistage sampling design in ELS:2002.

5. Findings

5.1 Teachers' Perceptions of Immigrant and Language-Minority Students

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics for students by their immigrant and language-minority statuses. The top of the table shows that on average, teachers most often report that immigrants who are native English speakers are hardworking and likely to complete college. They most often negatively perceive nonimmigrant language-minority students. Comparing the two remaining groups of students, teachers more often see immigrant language-minority students as hardworking, but they favor nonimmigrant native English speakers for college completion. Thus, while immigrant students enjoy their teachers' positive perceptions of effort, on average teachers perceive native English speakers as more likely to have college potential.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

| Nonimmigrant native English speaker | Nonimmigrant language-minority | Immigrant native English speakers | Immigrant language-minority | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Math Teachers' Perceptions | ||||||||

| Works hard for good grades (0-1) | 0.682 | (0.475) | 0.634 | (0.438) | 0.721 | (0.387) | 0.688 | (0.407) |

| Expects to complete college (0-1)a, d, f | 0.522 | (0.510) | 0.420 | (0.448) | 0.610 | (0.419) | 0.472 | (0.438) |

| Student Academic Outcomes | ||||||||

| 10th grade math GPA (0-4) a, d | 2.071 | (1.101) | 1.846 | (1.017) | 2.203 | (0.933) | 1.950 | (1.000) |

| Advances in math in grade 11 (0-1) a, c | 0.679 | (0.477) | 0.604 | (0.445) | 0.648 | (0.412) | 0.586 | (0.432) |

| Student Demographics | ||||||||

| Female (0-1) | 0.500 | (0.511) | 0.489 | (0.455) | 0.451 | (0.429) | 0.545 | (0.437) |

| Race/ethnicity (0-1) | ||||||||

| White a, b, c, d, f | 0.738 | (0.449) | 0.131 | (0.308) | 0.368 | (0.416) | 0.124 | (0.289) |

| Black a, c, d, f | 0.128 | (0.341) | 0.073 | (0.238) | 0.184 | (0.334) | 0.033 | (0.156) |

| Latino/a a, b, c, d, f | 0.075 | (0.269) | 0.579 | (0.449) | 0.143 | (0.302) | 0.604 | (0.429) |

| Asian a, b, c, e | 0.011 | (0.106) | 0.169 | (0.341) | 0.201 | (0.346) | 0.224 | (0.366) |

| Other race b, c, d, e, f | 0.048 | (0.218) | 0.047 | (0.193) | 0.103 | (0.262) | 0.015 | (0.107) |

| Family Background | ||||||||

| Parents' educational attainment (0-1) | ||||||||

| High school or less a, c, d, f | 0.224 | (0.426) | 0.430 | (0.451) | 0.152 | (0.310) | 0.446 | (0.436) |

| Some college a, c | 0.372 | (0.494) | 0.276 | (0.407) | 0.295 | (0.393) | 0.262 | (0.385) |

| College degree a, c, d, f | 0.234 | (0.432) | 0.179 | (0.349) | 0.290 | (0.391) | 0.152 | (0.315) |

| Graduate degree a, b, d, f | 0.170 | (0.384) | 0.115 | (0.290) | 0.263 | (0.380) | 0.141 | (0.305) |

| Parents' income (log) a, c, d, e, f | 10.777 | (1.125) | 10.299 | (1.041) | 10.736 | (0.947) | 9.999 | (1.400) |

| Academic Experiences | ||||||||

| Grade 10 math course placement (0-1) | ||||||||

| Enrolled in basic math a, d | 0.079 | (0.275) | 0.117 | (0.293) | 0.050 | (0.188) | 0.083 | (0.242) |

| Enrolled in Algebra 1 a, c | 0.177 | (0.390) | 0.239 | (0.388) | 0.194 | (0.341) | 0.271 | (0.390) |

| Enrolled in geometry c | 0.453 | (0.508) | 0.414 | (0.448) | 0.380 | (0.418) | 0.382 | (0.390) |

| Enrolled in Algebra 2 a, d, f | 0.291 | (0.464) | 0.229 | (0.383) | 0.376 | (0.418) | 0.264 | (0.390) |

| 9th grade math GPA (0-4) a, d | 2.183 | (1.070) | 2.001 | (0.965) | 2.312 | (0.981) | 2.059 | (0.390) |

| School Characteristics | ||||||||

| Students receiving free lunch (0-1) a, c, d, f | 0.220 | (0.213) | 0.355 | (0.256) | 0.227 | (0.192) | 0.354 | (0.232) |

| Minority enrollment (0-1) a, b, c, d, f | 0.260 | (0.267) | 0.544 | (0.281) | 0.341 | (0.249) | 0.559 | (0.253) |

| Parents with a college degree (0-1) a, c, d, f | 0.231 | (0.143) | 0.197 | (0.143) | 0.237 | (0.118) | 0.195 | (0.141) |

|

| ||||||||

| Unweighted N- Total | 8400 | 790 | 240 | 690 | ||||

| Unweighted N - Works hard for good grade: | 5,760 | 510 | 170 | 500 | ||||

| Unweighted N - Expects to complete college | 4,630 | 400 | 150 | 390 | ||||

Superscript letters denote significant differences between group means at the p < 0.05 level as follows: (1) nonimmigrant native English speakers differ from

nonimmigrant language-minority students

immigrant native English speakers, and

immigrant language-minority students;

(2) nonimmigrant language-minority students differ from

immigrant native English speakers, and

immigrant language-minority students;

(3) and immigrant native English speakers differ from

immigrant language-minority students.

Moving down the table to the outcome variables, differences in the average GPAs across the four nativity and language-minority groups are largely consistent with differences in teachers' perceptions that the student will complete college. On average, native English speaking immigrants earn the highest GPAs, and nonimmigrant language-minority students earn the lowest. However, despite teachers' greater perceptions of effort and potential among immigrants, nonimmigrant native English speakers are the most likely to advance compared to their immigrant counterparts. For most students, advancing in math means that they enroll in Algebra 2 in 11th grade, since geometry is the modal category across all groups for 10th grade math course-taking (bottom of Table 1).

5.2 Teachers' Perceptions and Students' Math GPA and Likelihood of Advancing in Math

Turning now to our multivariate analysis, models 1 through 3 on the left side of Table 2 show the OLS results predicting students' GPAs in sophomore year math. Model 1 includes dummy variables for our four groups of students based on the intersecting dimensions of nativity and language-minority status (ref: nonimmigrant native English speakers) as well as students' sex and race/ethnicity. The next model adds teachers' perceptions to show that students whose teachers see them as hardworking and those whose teachers see them as headed for college earn GPAs more than 1.5 full letter grades higher than those who do not (b = 0.861, b = 0.788, respectively). Additionally, note that there are no differences in math GPA for students based on their nativity and language-minority status once teachers' perceptions are included in the model. Model 3 examines whether other factors – family background, academic experiences, and school characteristics – account for the association between teachers' perceptions and students' end-of-year GPA in 10th grade. Even with these factors controlled, teachers' perceptions strongly predict math GPA: students perceived as hardworking and expected to complete college have GPAs that are an estimated 0.683 and 0.490 letter grades higher than their peers, respectively. In sum, teachers' perceptions predict students' GPAs in the expected direction and explain the GPA gap between nonimmigrant native English speakers and immigrant native English speakers.

Table 2. OLS and logistic regression models predicting student academic outcomes.

| 10th grade math GPA | Advances in math in 11th grade | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| b | S.E. | b | S.E. | b | S.E. | b | S.E. | b | S.E. | b | S.E. | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Student demographics | ||||||||||||

| Nonimmigrant language-minority | -0.049 | (0.065) | 0.017 | (0.051) | 0.044 | (0.048) | -0.266 | (0.122) * | -0.223 | (0.120) | -0.200 | (0.126) |

| Immigrant native English speaker | 0.204 | (0.100) * | 0.070 | (0.081) | 0.012 | (0.074) | -0.128 | (0.179) | -0.275 | (0.195) | -0.283 | (0.202) |

| Immigrant language-minority | 0.006 | (0.075) | 0.011 | (0.060) | 0.076 | (0.055) | -0.381 | (0.119) ** | -0.411 | (0.123) *** | -0.357 | (0.126) ** |

| Female | 0.251 | (0.027) *** | 0.049 | (0.023) * | 0.021 | (0.020) | 0.203 | (0.052) *** | 0.033 | (0.057) | -0.021 | (0.060) |

| Black | -0.759 | (0.045) *** | -0.487 | (0.039) *** | -0.176 | (0.037) *** | -0.228 | (0.094) * | 0.055 | (0.096) | 0.098 | (0.107) |

| Latino/a | -0.483 | (0.052) *** | -0.306 | (0.043) *** | -0.098 | (0.040) * | -0.217 | (0.096) * | -0.020 | (0.099) | -0.033 | (0.116) |

| Asian | 0.198 | (0.072) ** | 0.025 | (0.058) | 0.035 | (0.049) | 0.241 | (0.151) | 0.088 | (0.167) | 0.127 | (0.167) |

| Other race | -0.287 | (0.068) *** | -0.160 | (0.054) ** | -0.051 | (0.053) | -0.300 | (0.123) * | -0.182 | (0.126) | -0.172 | (0.132) |

| Teachers' perceptions | ||||||||||||

| Student is hardworking | 0.861 | (0.028) *** | 0.683 | (0.026) *** | 0.583 | (0.066) *** | 0.607 | (0.071) ** | ||||

| Student will complete college | 0.788 | (0.027) *** | 0.490 | (0.029) *** | 0.997 | (0.074) *** | 0.966 | (0.082) ** | ||||

| Family background | ||||||||||||

| Parent has a high school degree or less | -0.098 | (0.030) ** | -0.417 | (0.094) *** | ||||||||

| Parent has some college | -0.054 | (0.027) * | -0.209 | (0.086) * | ||||||||

| Parent has a postgraduate degree | 0.052 | (0.030) | -0.100 | (0.101) | ||||||||

| Parents' income (log) | 0.030 | (0.011) ** | 0.065 | (0.025) ** | ||||||||

| Academic experiences | ||||||||||||

| Enrolled in basic math | 0.239 | (0.053) *** | -0.958 | (0.133) *** | ||||||||

| Enrolled in Algebra 1 | -0.041 | (0.034) | -0.538 | (0.099) *** | ||||||||

| Enrolled in Algebra 2 | 0.109 | (0.027) *** | -1.754 | (0.109) *** | ||||||||

| 9th grade math GPA | 0.363 | (0.014) *** | 0.320 | (0.036) *** | ||||||||

| School characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Students receiving free lunch (0-1) | 0.147 | (0.068) * | -0.252 | (0.232) | ||||||||

| Minority enrollment (0-1) | -0.265 | (0.060) *** | 0.349 | (0.197) | ||||||||

| Parents with a college degree (0-1) | -0.048 | (0.102) | 0.417 | (0.305) | ||||||||

| Intercept | 2.089 | (0.027) *** | 1.143 | (0.029) *** | 0.288 | (0.129) * | 0.709 | (0.052) *** | -0.104 | (0.061) | -0.641 | (0.315) * |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Unweighted N | 8840 | 8840 | 8840 | 10120 | 10120 | 10120 | ||||||

| R-square | 0.08 | 0.44 | 0.55 | |||||||||

| -2 Log Likelihood | 12767 | 11885 | 10876 | |||||||||

p < 0.001,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.05 (two tailed tests)

Reference groups: nonimmigrant native English speaker, male, white, parent has a college degree, enrolled in geometry.

Models 4 through 6 on the right side of Table 2 replicate the same analytic strategy in a series of logistic regression models predicting students' likelihood of advancing in math in the 11th grade. These findings are somewhat different from our estimates of math GPA. The baseline model (model 4) shows that net of gender and race/ethnicity, language-minority students (both nonimmigrants and immigrants) are less likely than native English speakers to advance in math. In model 5, we see that students whose teachers have positive perceptions of their effort and potential are more likely to advance to a more demanding math class. These perceptions explain the lower likelihood of advancing in math among nonimmigrant language-minority students. Teachers' perceptions of students' effort and potential remain predictive of advancing in model 6, where we include controls for family background, academic experiences, and school characteristics. In addition, net of all controls, immigrant language-minority students have a 30% lower likelihood of advancing to demanding coursework compared with nonimmigrant native English speakers, even when their teachers' perceptions are taken into account.8 In sum, teachers' perceptions do not completely explain why immigrant and language-minority students are less likely to advance to more demanding coursework in their junior year.

5.3 Students' Nativity and Language-Minority Status and the Returns to Teachers' Perceptions

Table 3 adds a series of interaction terms to examine whether the estimated effect of teachers' perceptions of hard work and college potential varies according to immigrant and language-status group. The first two models build on model 3 in Table 2 and include the interactions of teachers' perceptions of hard work and college potential with students' nativity and language-minority status to predict GPA. The second two models introduce these interaction terms to model 6 in Table 2 to predict advancement in math. None of the interaction effects reach statistical significance in models 1 and 2, meaning that teachers' perceptions have consistent associations with math GPA across all groups. Similarly, non-significant interaction effects in model 4 suggest that a teachers' perceptions that the student will complete college offers the same return across groups of students in terms of their likelihood of advancing in math. In model 3, however, we see that the increase in probability of advancing in math associated with perceived hard work varies according to students' nativity and language-minority status.

Table 3. Interaction effects of teachers' perceptions and nativity and language minority status on students' academic outcomes.

| 10th grade math GPA | Advances in math in 11th grade | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| b | S.E. | b | S.E. | b | S.E. | b | S.E. | |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Student demographics | ||||||||

| Nonimmigrant language-minority | 0.005 | (0.068) | 0.013 | (0.058) | -0.521 | (0.178) ** | -0.279 | (0.141) * |

| Immigrant native English speaker | 0.029 | (0.112) | 0.108 | (0.109) | 0.331 | (0.355) | -0.171 | (0.324) |

| Immigrant language-minority | 0.110 | (0.093) | 0.056 | (0.084) | -0.313 | (0.243) | -0.341 | (0.175) |

| Female | 0.021 | (0.020) | 0.020 | (0.020) | -0.020 | (0.060) | -0.022 | (0.060) |

| Black | -0.176 | (0.037) *** | -0.177 | (0.037) *** | 0.100 | (0.107) | 0.098 | (0.107) |

| Latino/a | -0.099 | (0.040) * | -0.097 | (0.041) * | -0.034 | (0.116) | -0.036 | (0.118) |

| Asian | 0.034 | (0.049) | 0.024 | (0.050) | 0.099 | (0.168) | 0.100 | (0.170) |

| Other race | -0.051 | (0.054) | -0.052 | (0.053) | -0.185 | (0.132) | -0.174 | (0.132) |

| Teachers' perceptions | ||||||||

| Student is hardworking | 0.681 | (0.029) *** | 0.683 | (0.026) *** | 0.584 | (0.077) *** | 0.607 | (0.071) *** |

| Student will complete college | 0.489 | (0.029) *** | 0.485 | (0.029) *** | 0.968 | (0.082) *** | 0.955 | (0.086) *** |

| Family background | ||||||||

| Parent has a high school degree or less | -0.098 | (0.030) ** | -0.097 | (0.030) ** | -0.421 | (0.094) *** | -0.417 | (0.094) *** |

| Parent has some college | -0.054 | (0.027) * | -0.054 | (0.027) * | -0.210 | (0.086) * | -0.210 | (0.086) * |

| Parent has a postgraduate degree | 0.052 | (0.030) | 0.052 | (0.030) | -0.096 | (0.101) | -0.099 | (0.101) |

| Parents' income (log) | 0.030 | (0.011) ** | 0.031 | (0.011) ** | 0.064 | (0.025) ** | 0.065 | (0.025) ** |

| Academic experiences | ||||||||

| Enrolled in basic math | 0.239 | (0.053) *** | 0.240 | (0.053) *** | -0.959 | (0.134) *** | -0.956 | (0.134) *** |

| Enrolled in Algebra 1 | -0.040 | (0.034) | -0.042 | (0.034) | -0.534 | (0.099) *** | -0.539 | (0.099) *** |

| Enrolled in Algebra 2 | 0.109 | (0.027) *** | 0.109 | (0.027) *** | -1.752 | (0.109) *** | -1.754 | (0.110) *** |

| 9th grade math GPA | 0.364 | (0.013) *** | 0.363 | (0.014) *** | 0.323 | (0.036) *** | 0.321 | (0.036) *** |

| School characteristics | ||||||||

| Students receiving free lunch (0-1) | 0.148 | (0.069) * | 0.147 | (0.068) * | -0.242 | (0.232) | -0.251 | (0.232) |

| Minority enrollment (0-1) | -0.265 | (0.060) *** | -0.266 | (0.060) *** | 0.346 | (0.198) | 0.346 | (0.197) |

| Parents with a college degree (0-1) | -0.048 | (0.101) | -0.047 | (0.102) | 0.417 | (0.305) | 0.421 | (0.304) |

| Interactions | ||||||||

| Hardworking * Nonimmigrant language-minority | 0.062 | (0.089) | 0.557 | (0.222) * | ||||

| Hardworking * Immigrant native English-speaker | -0.023 | (0.141) | -0.885 | (0.408) * | ||||

| Hardworking * Immigrant language-minority | -0.047 | (0.105) | -0.055 | (0.276) | ||||

| Will complete college * Nonimmigrant language-minority | 0.076 | (0.082) | 0.256 | (0.253) | ||||

| Will complete college * Immigrant native English speaker | -0.151 | (0.143) | -0.192 | (0.409) | ||||

| Will complete college * Immigrant language-minority | 0.047 | (0.106) | -0.019 | (0.250) | ||||

| Intercept | 0.289 | (0.129) * | 0.290 | (0.129) * | -0.625 | (0.315) * | -0.636 | (0.315) * |

|

| ||||||||

| Unweighted N | 8840 | 8840 | 10120 | 10120 | ||||

| R-square | 0.55 | 0.55 | ||||||

| -2 Log Likelihood | 10861 | 10874 | ||||||

p < 0.001,

p < 0.01,

p < 0.05 (two tailed tests)

Reference groups: nonimmigrant native English speaker, male, white, parent has a college degree, enrolled in geometry.

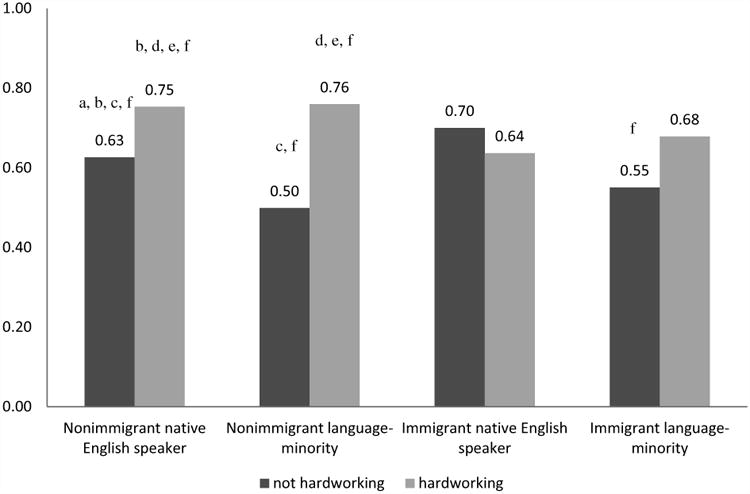

To illustrate what the interaction terms suggest in terms of the returns to positive teacher perceptions, Figure 1 graphs the predicted probabilities of advancing in math for each group based on the parameters estimated in model 3 for a student who is otherwise average. Overall, the returns to teachers' perceptions across groups are positive. To interpret the returns to positive teacher perceptions of effort for the reference group, we compare the two bars of each nativity and language-minority status group to each other, beginning on the far left. Students whose teachers identify them as hard workers have a higher probability of advancing to a more demanding math class in 11th grade (0.75) than those who teachers do not think they work hard (0.63). Turning to the second two bars, teachers' perceptions of effort mitigate the lower predicted probability of advancing for nonimmigrant language-minority students. That is, if teachers see nonimmigrant language-minority students as working hard, their probability of advancing is (0.76), which is equivalent to the probability of advancing among nonimmigrant native English speaking who are also perceived as hardworking (0.75). By contrast, native English speaking immigrants' likelihood of advancing is not statistically different based on teachers' perceptions of hard work (fifth and sixth bar from the left). Thus, hardworking or not, immigrant native English speakers are no more or less likely to advance than non-hardworking nonimmigrant native English speakers (leftmost bar). Finally, the rightmost bar shows that hardworking immigrant language-minority students are less likely to advance than similarly hardworking nonimmigrant native English speakers (0.68 and 0.75, respectively).

Figure 1. Predicted probability that a student advances in math in 11th grade by nativity, language-minority status, and teachers' perception of hard work.

Letters denote statistically significant differences at the p < 0.05 level between bar and bars to the right: (a) hardworking nonimmigrant native English speakers, (b) not hardworking nonimmigrant language-minority students, (c) hardworking nonimmigrant language-minority students, (d) hardworking immigrant native English speakers, (e) not hardworking immigrant language-minority students, and (f) hardworking immigrant language-minority students.

6. Discussion and Conclusion

Immigrant families place tremendous faith in schools as avenues for pursuing their American Dreams. Despite the pro-school attitudes of immigrant families, we find that teachers' perceive that immigrant and language-minority students are as hardworking as non-immigrant native English speakers, but also that teachers perceive non-native English speakers as less likely to complete college than their peers. Further, these perceptions are important in shaping students' preparation for college but they do not necessarily help children of immigrants to navigate an increasingly complex educational system en route to a critical stage – the transition to college – where things like acquiring the required credits are crucial. Specifically, immigrant and language-minority students are equitably rewarded with high grades based on their teachers' perceptions of them, but gaps in advancing in math based on teachers' perceptions and differential returns to students' hard work suggest that high schools are failing to foster success for some of the best and brightest children of immigrants. Interestingly, much of the conversation regarding opportunities for children of immigrants has focused on legislating greater opportunity for the Dreamers, a highly select group. Although this is an important conversation, our work sheds light on an unexplored factor in a much larger and growing group of students' access to higher education. Taken together, our contribution underscores the importance of relational aspects of high schools, where opportunities to prepare for college are stratified.

One important question underlying this work is the role of teachers within schools for immigrant and language-minority students. Teachers may potentially be supportive mentors who offer valuable institutional expertise or gatekeepers who respond to stereotyped ideas about their students and maintain inequality. We found evidence for both. Our analysis of the returns to teachers' perceptions across groups demonstrated how positive teacher perceptions shape students' preparation for college. Students whose teachers expect them to complete college and who see them as hardworking earn higher GPAs in their courses regardless of their immigrant and language-minority status. Additionally, students who are perceived as hardworking and likely to compete college are more likely to advance to the more demanding math classes required for college preparation. Yet, differences in teacher perceptions do not fully account for differences in rates of advancing in math for all groups. Specifically, language-minority immigrants are less likely to advance in math compared with nonimmigrant native English speakers even when their teachers view them as hardworking and likely to complete college. Nevertheless, these patterns suggest that teachers' perceptions may institutionally support and sponsor students perceived as having what it takes to be college material towards attaining the GPAs and coursework required for college admissions.

By contrast, our examination of differences in the returns to positive teacher perceptions within nativity and language minority status groups sheds light on how teachers' perceptions may reproduce inequality through gatekeeping. In particular, teachers' perceptions of hard work help nearly all students to get ahead and on to more demanding math classes. Despite being generally perceived as hardworking and likely to complete college, teachers' perceptions of hard work have a negligible return in terms of advancing in math for immigrant native English speakers. On the other hand, the returns to being perceived as hardworking are highest for nonimmigrant language-minority students. These students are the least likely to advance when their teachers view them as not working hard. On a positive note, when teachers do identify students from this group as hard workers, they stand to attain parity with nonimmigrant native English speakers in terms of advancing in math. These findings are consistent with Hao and Pong's argument that second-generation immigrants are the most poised for success in U.S. schools due to the potent combination of immigrant optimism and greater access to positive relationships at school (2008). However, we expand on these findings in two ways. First, our results highlight the salience of language-minority status above and beyond generational status. Second, we demonstrate how in their dual-capacity as mentors and gatekeepers, teachers' perceptions of students' hard work and potential shape whether immigrant and language-minority students will merely get by or get ahead while in high school.

Why then might teachers' perceptions shape student outcomes differently depending on students' language-minority status and nativity? We speculate that the gatekeeping and signaling dynamics between teachers and their students from immigrant and language-minority backgrounds do not contribute to student success in the same way as they do for others. For example, if students are less familiar with U.S. schools, they may need not just positive perceptions, but also more active endorsement or guidance from math teachers if they are to advance. Alternatively, if social differences between teachers and language-minority or immigrant students limit the extent to which students feel supported by teachers, students may be less likely to seek guidance from teachers in their course-taking decisions (Stanton-Salazar et al., 2001). While distinguishing between all of these potential pathways is beyond the scope of our paper, our contribution illustrates the importance of these processes at a critical stage in students' college preparation. We call for further research to deepen our understanding of the causes and consequences of differences in teachers' perceptions on these micro- and interactional-levels across subjects.

One additional question that our analysis does not answer is whether the link between teachers' perceptions of whether students are college material and students' preparation for college is distinct for students who learned English and another language concurrently as children. Some scholars have argued that bilingualism is an important asset for students (Kao and Tienda, 1995; Portes and Rumbaut, 2001) while others have identified bilingualism as a potential obstacle to success in U.S. schools (Rumberger and Larson, 1998; Valenzuela, 1999). However, ELS:2002 only indicates whether English was the first language that the student learned. Thus, our study cannot speculate about whether the experiences of dual-language learners are different from those of other language-minority students. However, we tested whether our findings for language-minority students could be explained by the students' English proficiency, standardized-test scores in reading, or ESL placement and found that these measures did not alter our findings.

The power of our findings is underscored by the fact that our study observes these processes near the end of high school at a point when it is likely that teachers' subjective evaluations of students have been shaping students' academic outcomes for many years. Additionally, immigrant and language-minority students are more likely to drop out during high school (Klein et al., 2004; Suárez-Orozco et al., 2009), suggesting that the students remaining in our sample may be more resilient and attached to schooling than their former classmates who dropped out or ceased math course-taking earlier on. Both of these aspects of our study are substantively important and also suggest that our results are actually a conservative estimate of these dynamics. However, further scholarship is needed to understand how teachers' perceptions of immigrant and language-minority students arise and to identify the processes by which teachers' perceptions shape student academic outcomes earlier in the educational process.

As increasing numbers of immigrant and language-minority students approach the transition to college, it is crucial to understand how their teachers understand them and shape their capacity to attend college and reach their American Dreams. Our study demonstrates how teachers' perceptions of students' social backgrounds shape their academic outcomes in ways that produce winners and losers at a decisive phase of students' educational trajectories. As sophomores, students take cues from their school experiences as they make or fail to make plans for postsecondary education. Their ability to transition to college will depend not only on their grades and other measures of achievement, but also on whether they had opportunities in high school to learn college-preparatory math. Thus, our study speaks to the question of whether students will merely get through their math classes by earning grades that indicate sufficient course mastery or will alternatively continue on to the demanding math classes that will allow them to get ahead in their pursuit of their American Dreams.

Highlights.

Teachers' views of immigrants and language minorities shape academic success.

Teachers' perceptions of effort and potential link to GPA and advancing in math.

Language-minority immigrants take less math, regardless of how teachers view them.

Language-minority US born students who work hard advance on par with peers.

Teachers' perceptions shape getting through vs. getting ahead in high school math.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Russell Sage Foundation (RSF Project # 88-06-12, Chandra Muller, PI, and Rebecca Callahan, Co-PI) and a grant from the National Science Foundation (DUE-0757018, Chandra Muller, PI, Catherine Riegle-Crumb, Co-PI, and R. Kelly Raley, Co-PI.) This research was also supported by grant 5 R24 HD042849, Population Research Center, awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Health and Child Development. This research has received support from the grant 5 T32 HD007081, Training Program in Population Studies, awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Health and Child Development. Opinions reflect those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the granting agencies.

The authors would like to thank Rebecca Callahan, Chelsea Moore, Catherine Riegle-Crumb, Keith Robinson, as well as other members of the Education and Transition to Adulthood Group (ETAG) at the University of Texas at Austin for their thoughtful comments on earlier drafts.

Footnotes

We define language -minority students as those who first learned a language other than English, regardless of their English proficiency, placement in English as a second language (ESL) courses, or designation as an English Language Learner (ELL) or as Limited English Proficient by their schools (LEP) (Callahan et al., 2010).

We replicated our models to the extent possible by using English teachers' reports of student effort and potential to predict 10th grade English GPA; the findings were consistent with the math-based results reported here.

Students who took math as sophomores but not as juniors or whose junior year course was not more advanced in the math course-taking sequence are the reference category (not advancing) for this measure.

Because ELS:2002 measured students' first languages, it is impossible to know whether a student learned English concurrently with another language. Additionally, although immigrant students in our study are by definition first-generation immigrants, there is some heterogeneity among U.S.-born language-minority students as to their generational status. 75% are second generation, meaning that at least one of their parents was born in another country. Sensitivity analyses were conducted replicating our analyses with generation and language-minority status as the dimensions of students' social backgrounds modeled. The results were consistent with those reported here.

In a separate analysis, we included the students' standardized math and reading assessments and an indicator for ESL placement and found results consistent with those shown here.

In compliance with NCES restricted-use data requirements, we round all figures to the nearest 10 when reporting frequencies.

In analyses not shown here, we replicated all models using the subgroup of students from the analytical sample with non-missing information on both outcome variables (n=8,840). These findings were consistent with those presented here.

Likelihood calculated by exponentiating the log odds of advancing for immigrant language-minority students in Table 2, model 6.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Works Cited

- Adelman C. Answers in the Tool Box: Academic Intensity, Attendance Patterns, and Bachelor's Degree Attainment. Office of Educational Research and Improvement, U.S. Department of Education; Washington, DC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Alba R, Nee V. Remaking the American Mainstream: Assimilation and Contemporary Immigration. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Missing Data. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Aud S, Hussar W, Planty M, Snyder T, Bianco K, Fox M, Frohlich L, Kemp J, Drake L. The Condition of Education 2010. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Services, National Center for Education Statistics (NCES 2010-028); Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. Cultural Reproduction and Social Reproduction. In: Karabel Jerome, Haley AH., editors. Power and Ideology in Education. Oxford; New York: 1977. pp. 487–511. [Google Scholar]

- Bozick R, Ingels SJ. Mathematics Coursetaking and Achievement at the End of High School: Evidence from the Education Longitudinal Study of 2002 (ELS:2002) U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Services, National Center for Education Statistics (NCES 2008-319); Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Brophy JE. Research on the self-fulfilling prophecy and teacher expectations. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1983;75:631–661. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan RM. Tracking and high school English learners: limiting opportunity to learn. American Educational Research Journal. 2005;42:305–328. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan RM, Wilkinson L, Muller C. Academic achievement and course taking among language minority youth in U.S. schools: effects of ESL placement. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. 2010;32:84–117. doi: 10.3102/0162373709359805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonaro W. Tracking, students' effort, and academic achievement. Sociology of Education. 2005;78:27–49. [Google Scholar]

- Dabach DB. Teachers as agents of reception: an analysis of teacher preference for immigrant-origin second language learners. The New Educator. 2011;7:66–86. [Google Scholar]

- DiPrete TA, Jennings JL. Social and behavioral skills and the gender gap in early educational achievement. Social Science Research. 2012;41:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey DB, Pribesh S. When race matters: teachers' evaluations of students' classroom behavior. Sociology of Education. 2004;77:267–282. [Google Scholar]

- Farkas G, Grobe RP, Sheehan D, Shuan Y. Cultural resources and school success: gender, ethnicity, and poverty groups within an urban school district. American Sociological Review. 1990;55:127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Frank KA, Muller C, Schiller KS, Riegle-Crumb C, Mueller AS, Crosnoe R, Pearson J. The social dynamics of mathematics coursetaking in high school. American Journal of Sociology. 2008;113:1645–1696. doi: 10.1086/587153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaddis SM. The influence of habitus in the relationship between cultural capital and academic achievement. Social Science Research. 2013;42:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamoran A, Hannigan EC. Algebra for everyone? Benefits of college-preparatory mathematics for students with diverse abilities in early secondary school. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. 2000;22:241–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gamoran A, Mare RD. Secondary school tracking and educational inequality: compensation, reinforcement, or neutrality? American Journal of Sociology. 1989;94:1146–1183. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson G, Gándara P, Koyama JP, editors. School Connections: Immigrant Mexican Youth, Peers, and School Achievement. Teachers College Press; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Glick JE, White MJ. Post-secondary school participation of immigrant and native youth: the role of familial resources and educational expectations. Social Science Research. 2004;33:272–299. [Google Scholar]

- Good TL, Brophy JE. Looking in Classrooms. 8th. Longman; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Green G, Rhodes J, Heitler Hirsch A, Suárez-Orozco C, Camic PM. Supportive adult relationships and the academic engagement of Latin American immigrant youth. Journal of School Psychology. 2008;46:393–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hachfeld A, Anders Y, Schroeder S, Stanat P, Kunter M. Does immigration background matter? How teachers' predictions of students' performance relate to student background. International Journal of Educational Research. 2010;49:78–91. [Google Scholar]

- Hao L, Pong S. The role of school in the upward mobility of disadvantaged immigrants' children. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2008;620:62–89. doi: 10.1177/0002716208322582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagelskamp C, Suárez-Orozco C, Hughes D. Migrating to opportunities: how family migration motivations shape academic trajectories among newcomer immigrant youth. Journal of Social Issues. 2010;66:717–739. [Google Scholar]

- Ingels SJ, Pratt DJ, Wilson D, Burns LJ, Currivan D, Rogers JE, Hubbard-Bednasz S. Education Longitudinal Study of 2002: Base-Year to Second Follow-up Data File Documentation. US Department of Education, Institute of Education Services, National Center for Education Statistics (NCES 2008-347); Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jussim L, Harber KD. Teacher expectations and self-fulfilling prophecies: knowns and unknowns, resolved and unresolved controversies. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2005;9:131–155. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0902_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao G, Tienda M. Optimism and achievement: the educational performance of immigrant youth. Social Science Quarterly. 1995;76:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kasinitz P, Mollenkopf JH, Waters MC, Holdaway J. Inheriting the City: The Children of Immigrants Come of Age. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Katz SR. Teaching in tensions: Latino immigrant youth, their teachers, and the structures of schooling. Teachers College Record. 1999;100:809–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly S. What types of students' effort are rewarded with high marks? Sociology of Education. 2008;81:32–52. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly S. The black-white gap in mathematics course taking. Sociology of Education. 2009;82:47–69. [Google Scholar]

- Klein S, Bugarin R, Beltranena R, McArthur E. Language Minorities and Their Educational and Labor Market Indicators—Recent Trends. US Department of Education, Institute of Education Services, National Center for Education Statistics (NCES 2004–009); Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lleras C. Do skills and behaviors in high school matter? The contribution of noncognitive factors in explaining differences in educational attainment and earnings. Social Science Research. 2008;37:888–902. [Google Scholar]

- Madon S, Jussim L, Keiper S, Eccles J, Smith A, Palumbo P. The accuracy and power of sex, social class, and ethnic stereotypes: a naturalistic study in person perception. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1998;24:1304–1318. [Google Scholar]

- Matute-Bianchi ME. Ethnic identities and patterns of school success and failure among Mexican-descent and Japanese-American students in a California high school: an ethnographic analysis. American Journal of Education. 1986;95:233–255. [Google Scholar]

- McKown C, Weinstein RS. Teacher expectations, classroom context, and the achievement gap. Journal of School Psychology. 2008;46:235–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller C, Katz SR, Dance LJ. Investing in teaching and learning. Urban Education. 1999;34:292–337. [Google Scholar]

- Oates GLStC. Teacher-student racial congruence, teacher perceptions, and test performance. Social Science Quarterly. 2003;84:508–525. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlenko A. “We have room for but one language here”: language and national identity in the U.S. at the turn of the 20th century. Multilingua. 2002;21:163–196. [Google Scholar]

- Pong S, Hao L, Gardner E. The roles of parenting styles and social capital in the school performance of immigrant Asian and Hispanic adolescents. Social Science Quarterly. 2005;86:928–950. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Rumbaut R. Legacies: The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation. University of California Press; Berkeley, CA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Riegle-Crumb C. The path through math: course sequences and academic performance at the intersection of race-ethnicity and gender. American Journal of Education. 2006;113:101–122. doi: 10.1086/506495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riegle-Crumb C, Grodsky E. Racial-ethnic differences at the intersection of math course-taking and achievement. Sociology of Education. 2010;83:248–270. [Google Scholar]

- Riegle-Crumb C, Humphries M. Exploring bias in math teachers' perceptions of students' ability by gender and race/ethnicity. Gender & Society. 2012;26:290–322. doi: 10.1177/0891243211434614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rist R. Student social class and teacher expectations: the self-fulfilling prophecy in ghetto education. Harvard Educational Review. 1970;40:411–451. [Google Scholar]

- Rong XL, Preissle J. Educating Immigrant Students in the 21st Century: What Educators Need to Know. Corwin; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum J. Beyond College for All: Career Paths for the Forgotten Half. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rumberger RW, Larson KA. Toward explaining differences in educational achievement among Mexican American language-minority students. Sociology of Education. 1998;71:68–92. [Google Scholar]

- Saft EW, Pianta RC. Teachers' perceptions of their relationships with students: effects of child age, gender, and ethnicity of teachers and children. School Psychology Quarterly. 2001;16:125–141. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider B, Swanson CB, Reigle Crumb C. Opportunities for learning: course sequences and positional advantages. Social Psychology of Education. 1998;2:25–53. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EA, Belmont MJ. Motivation in the classroom: reciprocal effects of teacher behavior and student engagement across the school year. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1993;85:571–581. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton-Salazar RD, Chávez LF, Tai RH. The help-seeking orientations of Latino and non-Latino urban high school students: a critical-sociological investigation. Social Psychology of Education. 2001;5:49–82. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton-Salazar RD, Dornbusch SM. Social capital and the reproduction of inequality: information networks among Mexican-origin high school students. Sociology of Education. 1995;68:116–135. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson DL, Schiller KS, Schneider B. Sequences of Opportunities for Learning. Sociology of Education. 1994;67:184–198. [Google Scholar]

- Stiggins RJ, Conklin NF. Teachers' Hands: Investigating the Practices of Classroom Assessment. State University of New York Press; Albany, NY: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozco C, Pimentel A, Martin M. The significance of relationships: academic engagement and achievement among newcomer immigrant youth. Teachers College Record. 2009;111:712–749. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozco C, Suárez-Orozco M, Todorova I. Learning a New Land: Immigrant Students in American Society. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton A, Muller C, Langenkamp AG. High school transfer students and the transition to college: timing and the structure of the school year. Sociology of Education. 2013:63–82. doi: 10.1177/0038040712452889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillman KH, Guo G, Harris KM. Grade retention among immigrant children. Social Science Research. 2006;35:129–156. [Google Scholar]

- Trouilloud D, Sarrazin P, Bressoux P, Bois J. Relation between teachers' early expectations and students' later perceived competence in physical education classes: autonomy-supportive climate as a moderator. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2006;98:75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Valdéz G. Learning and Not Learning English: Latino Students in American Schools. Teachers College Press; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela A. Subtractive Schooling: U S -Mexican Youth and the Politics of Caring. State University of New York Press; Albany, NY: 1999. [Google Scholar]