SUMMARY

Poxvirus replication involves synthesis of double stranded RNA (dsRNA), which can trigger antiviral responses by inducing phosphorylation-mediated activation of protein kinase R (PKR) and stimulating 2’5’-oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS). PKR inactivates the translation initiation factor eIF2α via phosphorylation, while OAS induces the endonuclease RNase L to degrade RNA. We show that poxvirus decapping enzymes D9 and D10, which remove caps from mRNAs, inhibit these antiviral responses by preventing dsRNA accumulation. Catalytic site mutations of D9 and D10, but not of either enzyme alone, halt vaccinia virus late protein synthesis and inhibit virus replication. Infection with the D9-D10 mutant was accompanied by massive mRNA reduction, cleavage of ribosomal RNA and phosphorylation of PKR and eIF2α that correlated with a ~15-fold increase in dsRNA compared to wild-type virus. Additionally, mouse studies show extreme attenuation of the mutant virus. Thus, vaccinia virus decapping, in addition to targeting mRNAs for degradation, prevents dsRNA accumulation and anti-viral responses.

INTRODUCTION

Two remarkable and seemingly unrelated properties of poxviruses are the encoding of decapping enzymes that hydrolyze the 5’cap of mRNA (Parrish and Moss, 2007; Parrish et al., 2007) and the synthesis of viral complementary or double-stranded (ds) RNA (Boone et al., 1979; Colby and Duesberg, 1969) which is a potent inducer of innate antiviral response pathways (Silverman, 2007). Here we show that inactivation of the vaccinia virus (VACV) decapping enzymes leads to a huge increase in dsRNA with a devastating effect on viral protein synthesis and replication in infected cells and severe attenuation in mice.

Eukaryotic mRNAs typically possess a cap at the 5’ end (Furuichi et al., 1975; Wei et al., 1975) and poly(A) at the 3’ end (Edmonds et al., 1971), both of which are important for stability and translation. Enzymes with nudix hydrolase motifs that decap mRNA are present in yeast and mammalian cells and are thought to function in mRNA decay (Dunckley and Parker, 1999; Wang et al., 2002). mRNA decay begins with shortening of the poly(A) tail and proceeds in either the 5’ to 3’ or 3’ to 5’ direction (Garneau et al., 2007). In the 5’ to 3’ pathway, removal of the cap is followed by exoribonuclease Xrn1 digestion (Hsu and Stevens, 1993).

Poxviruses are double-stranded DNA viruses that replicate and transcribe their genomes and assemble infectious particles exclusively in the cytoplasm of cells (Moss, 2013). Like eukaryotes, poxviruses encode enzymes that cap and methylate the 5’ ends of mRNA (Barbosa and Moss, 1978; Martin et al., 1975; Wei and Moss, 1975) and add adenylate residues to the 3’ ends (Gershon et al., 1991; Moss et al., 1973) as well as enzymes with nudix hydrolase motifs that specifically degrade methylated cap structures on RNAs (Parrish and Moss, 2007; Parrish et al., 2007). In fact, VACV, the prototype poxvirus, encodes two decapping enzymes, D9 and D10, with 25% predicted amino acid identity. Homologs of D10 are conserved in all poxviruses and homologs of D9 are present in members of most vertebrate poxvirus genera (Upton et al., 2003) suggesting their importance. Gene expression is sequentially regulated during VACV infection (Baldick and Moss, 1993; Yang et al., 2010). Synthesis of the D9 decapping enzyme begins early in infection whereas D10 is only made following viral DNA replication together suggesting roles throughout the VACV cycle. Ribosome profiling indicated that D9 continues to be synthesized at late times (Z. Yang and B. Moss, unpublished). No evidence for interaction of D9 and D10 was obtained by affinity purification (Parrish and Moss, unpublished). Decapping enzymes may accelerate degradation of cellular mRNA to minimize the host response to virus infection and reduce competition with viral mRNAs for the translation machinery. Shortening the half-life of viral mRNAs might also sharpen the division between the early, intermediate and late phases of virus replication. Yet mutagenesis of D9 had no effect on VACV replication and mutagenesis of D10 had a modest effect on enhancing the stability of cellular and viral mRNA and reducing virulence in a mouse infection model (Liu et al., 2014; Parrish and Moss, 2006). Nevertheless, efforts to delete both D9 and D10 and propagate such mutants proved difficult suggesting that they have an essential but redundant function (Parrish and Moss, 2006).

We have now succeeded in constructing and isolating VACV with inactivating mutations in the catalytic sites of both D9 and D10. The double mutant, called vD9muD10mu, has a replication defect in customarily used human and monkey cell lines, which accounts for our initial inability to isolate the mutant. Synthesis of early mRNAs and proteins and genome replication occurred normally in non-permissive cells. However, subsequent to the onset of viral late transcription there was an abrupt decrease in the amount of late mRNAs and diminished late protein synthesis. These events were accompanied by cleavage of 28S and 18S rRNA, a signature of RNase L activation (Silverman et al., 1983), and phosphorylation of protein kinase R (PKR), eIF2α and IRF3. These findings suggested a role for double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), which activates innate antiviral pathways and leads to inhibition of protein synthesis (Perdiguero and Esteban, 2009; Silverman, 2007; Stark et al., 1998). Indeed, we found a large accumulation of dsRNA in cells infected with the double mutant. Since only the catalytic sites of D9 and D10 were inactivated, we concluded that an important role of decapping, in addition to enhancing decay of host and viral mRNAs, is to prevent double-stranded RNA from forming or to accelerate its degradation.

RESULTS

Host-Range Restriction of Catalytic Site Mutants

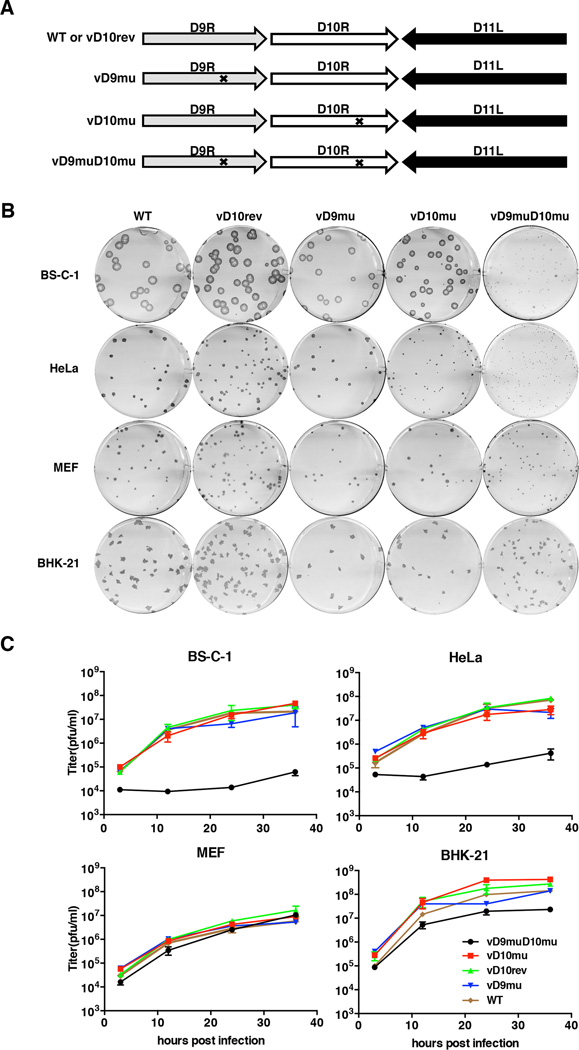

In previous studies we mutated the decapping enzymes of VACV individually and found only modest effects on virus replication (Liu et al., 2014; Parrish and Moss, 2006). The object of the present study was to determine the effects of inactivating both decapping enzymes in the same virus. Point mutations in the nudix hydrolase motifs of D9 and D10, which were previously shown to completely inactivate decapping activity in vitro (Parrish and Moss, 2007; Parrish et al., 2007), were made. The VACV mutant vD9mu with catalytic site mutations in D9 and the double mutant vD9muD10mu were constructed by homologous recombination for the present study (Figure 1A). The VACV mutant vD10mu, with catalytic site mutations in D10 and the revertant vD10rev control virus, which has wild type (WT) D9 and WT D10, were previously described (Liu et al., 2014). Initial studies indicated that each of the viruses including vD9muD10mu replicated in baby hamster kidney-21 (BHK-21) cells and therefore these cells were used to prepare stocks of mutant and WT viruses.

Figure 1. Host Restriction of Decapping Enzyme Mutants.

(A) Diagram of the D9R, D10R and adjacent D11L ORFs in VACV. Arrows indicate the direction of transcription. Xs within the ORFs represent the amino acid substitutions E129Q and E130Q for D9R and E144Q and E145Q for D10R. (B) Plaque formation. Viruses were grown in BHK-21 cells and purified by sucrose gradient sedimentation. BS-C-1, HeLa, MEF and BHK-21 cells were incubated with appropriate virus dilutions for 48 h and then stained with a polyclonal antibody to VACV followed by protein A conjugated to peroxidase and the substrate dianisidine. (C) One-step growth curves. BS-C-1, HeLa, MEF and BHK-21 cell monolayers in 12-well plates were incubated with 5 PFU/cell of the indicated virus and harvested at 3, 12, 24, and 36 h. Virus titers were determined by plaque assay in BHK-21 cells.

The abilities of the mutant viruses to form plaques in African green monkey BS-C-1, human HeLa, mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) and hamster BHK-21 cells are shown in Figure 1B. WT, vD10rev and vD9mu formed plaques that were similar to each other in the four cell lines. Relative plaque sizes were BS-C-1>BHK-21>HeLa≈MEF. The vD10mu virus formed plaques slightly smaller than WT in HeLa cells. Although the sizes of the plaques formed by vD9muD10mu approached those of WT virus in BHK-21 and MEF cells, they were barely detectable in BS-C-1 and HeLa cells. Thus, vD9muD10mu exhibited a severe host range phenotype.

Since plaque formation depends on cell-to-cell spread as well as virus replication, we carried out one-step growth experiments to distinguish between these events. The yields of vD9mu and vD10mu were equivalent to that of WT and the vD10rev in BS-C-1, HeLa, BHK-21 and MEF cells. In contrast, the yields of vD9muD10mu were similar or only slightly lower than the others in BHK-21 and MEF cells but two to three logs lower in HeLa and BS-C-1 cells (Figure 1C). Thus, the data obtained from plaque formation and virus yields indicated that the double mutant had a severe replication defect in BS-C-1 and HeLa cells but not in BHK-21 or MEF cells. The host range restriction of vD9muD10mu extended to African green monkey VERO, human MRC-5, and human A549 cells, whereas moderate replication occurred in rabbit kidney-13 (RK-13) cells and chicken embryo fibroblasts (not shown).

The low replication of vD9muD10mu in non-permissive cells could be due to an inability to form virus particles or to the formation of virions that lack infectivity. To visualize viral structures, permissive BHK-21 and non-permissive BS-C-1 cells were infected with the panel of mutant and WT viruses and examined by transmission electron microscopy. The vD9mu, vD10mu, vD10rev and WT viruses produced immature and mature virions in both BHK-21 and BS-C-1 cells consistent with their abilities to replicate (data not shown). Although vD9muD10mu formed numerous immature and mature virions in permissive BHK-21 cells (Figure S1A), only cytoplasmic clearing, a sign of an incipient virus factory, was seen in non-permissive BS-C-1 cells (Figure S1B) indicating a total block in morphogenesis.

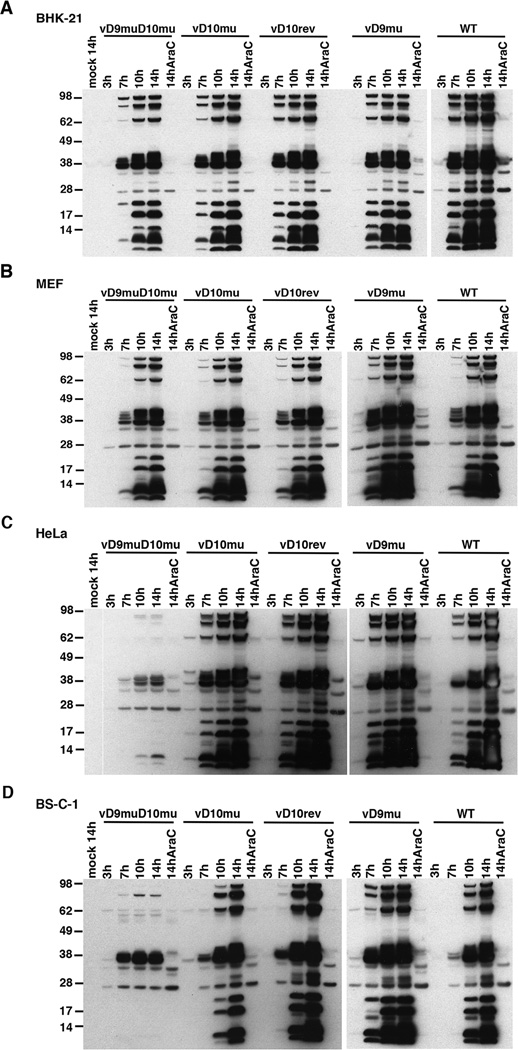

Viral Protein Synthesis

In cells infected with VACV, viral protein synthesis is regulated: early proteins are synthesized prior to viral DNA replication (and in the presence of a DNA replication inhibitor such as AraC) in relatively low amounts whereas the more abundant intermediate and late proteins are made exclusively post-replicatively. Viral proteins were analyzed to determine if impaired synthesis could account for the block in assembly of virions in cells infected with vD9muD10mu. BHK-21, MEF, HeLa and BS-C-1 cells were mock-infected or infected with the panel of mutant and WT viruses and lysates were prepared at 3, 7, 10 and 14 h. In parallel, cells were infected in the presence of AraC and harvested at 14 h. Viral proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with antibody produced by rabbits repeatedly immunized with purified infectious VACV. For WT VACV, vD10rev, vD9mu and vD10mu, the viral protein patterns were similar in each of the cell types (Figure 2, A–D). The major bands at 7 h and later times represent abundant post-replicative intermediate and late proteins. Several bands representing early proteins were seen in the 14 h AraC samples and faint corresponding bands were seen at 3 h in some blots (Figure 2, A–D). Protein patterns indistinguishable from those of the WT viruses were found in the blots of permissive BHK-21 and MEF cells infected with vD9muD10mu (Figure 2A, B). However, in non-permissive HeLa and BS-C-1 cells infected with vD9muD10mu, the major bands representing post-replicative proteins were faint or undetected with the exception of a ~38-kDa species (Figure 2C, D). By contrast, the early proteins made in BS-C-1 and HeLa cells infected with vD9muD10mu in the presence of AraC were similar to those made by the WT virus. Thus, vD9muD10mu exhibited reduced post-replicative protein synthesis in non-permissive BS-C-1 and HeLa cells.

Figure 2. Time-course of Viral Protein Synthesis Determined by Western Blotting.

(A) BHK-21, (B) MEF, (C) HeLa and (D) BS-C-1 cells were mock-infected or infected with 5 PFU/cell of purified vD9muD10mu, vD10mu, vD9mu and WT virus in the absence or presence of AraC and harvested at the indicated hours after infection. The lysates were analyzed by Western blotting using rabbit polyclonal antibody to VACV followed by secondary antibody conjugated to peroxidase. The mass in kDa and positions of marker proteins are indicated on the left.

A dynamic view of viral protein synthesis was obtained by pulse-labeling cells with [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine over the course of infection and analyzing the labeled proteins by autoradiography following SDS-PAGE. The gradual shut down of host protein synthesis facilitates the recognition of abundant viral proteins. BHK-21, MEF, HeLa and BS-C-1 cells were infected with the panel of WT and mutant viruses. In BHK-21 and MEF cells a distinct viral late pattern was achieved by 9 h after infection with all viruses including vD9muD10mu (Figure 3A, B). A prominent late pattern of viral protein synthesis occurred in HeLa and BS-C-1 cells infected with all viruses except vD9muD10mu, in which the late proteins appeared faint (Figure 3C, D). The Western blotting and pulse-labeling data indicated that post-replicative protein synthesis was severely impaired in HeLa and BS-C-1 cells infected with the double mutant.

Figure 3. Time Course of Protein Synthesis Determined by Pulse-Labeling with Radioactive Amino Acids.

(A) BHK-2, (B) MEF, (C) HeLa and (D) BS-C-1 cells were mock-infected or infected with 5 PFU/cell of purified vD9muD10mu, vD10mu, vD10rev, vD9mu or WT virus and pulse-labeled with [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine for 30 min at the indicated times. The cells were harvested and lysed after pulse-labeling, and the proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and exposed to a PhosphorImager for visualization of newly synthesized proteins. The mass in kDa and positions of marker proteins are indicated on the left.

Confocal microscopy was used to investigate the formation of cytoplasmic viral DNA factories and confirm viral early protein synthesis using specific antibodies. BS-C-1 cells were infected with vD10rev, vD10mu and vD9muD10mu and fixed at 12 h after infection. The cells were stained with MAbs to the proteins I3, E3 and A11 and with DAPI, which binds to DNA in the nucleus and cytoplasmic virus factories. I3 (Rochester and Traktman, 1998; Tseng et al., 1999) and E3 (Chang et al., 1992) are early proteins that bind single-stranded DNA and dsRNA, respectively. A11 is a late non-structural protein involved in viral membrane formation (Resch et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2011). Infected BS-C-1 cells stained for I3, A11 and DAPI are shown in Figure S2; staining of E3, A11 and DAPI are shown in Figure S3. DAPI-staining viral factories, which normally vary in number, shape, size and compactness, were present in cells infected with each of the viruses indicating that vD9muD10mu was not impaired in viral DNA synthesis. The three viral proteins were mainly associated with the factories. However, whereas the two early proteins I3 and E3 were labeled to similar extents in the cells infected with vD10rev, vD10mu and vD9muD10mu, there was less staining of the late A11 protein in cells infected with the latter mutant (Figure S2, S3). The A11 antibody staining intensity in cells infected with vD9muD10mu, determined by a tiling procedure involving more than 1,000 cells, was 59 to 60% of that in cells infected with vD10rev in two separate infections. The effect of the decapping enzyme mutations on A11 did not appear as severe as for the abundant late proteins analyzed by Western blotting and pulse-labeling.

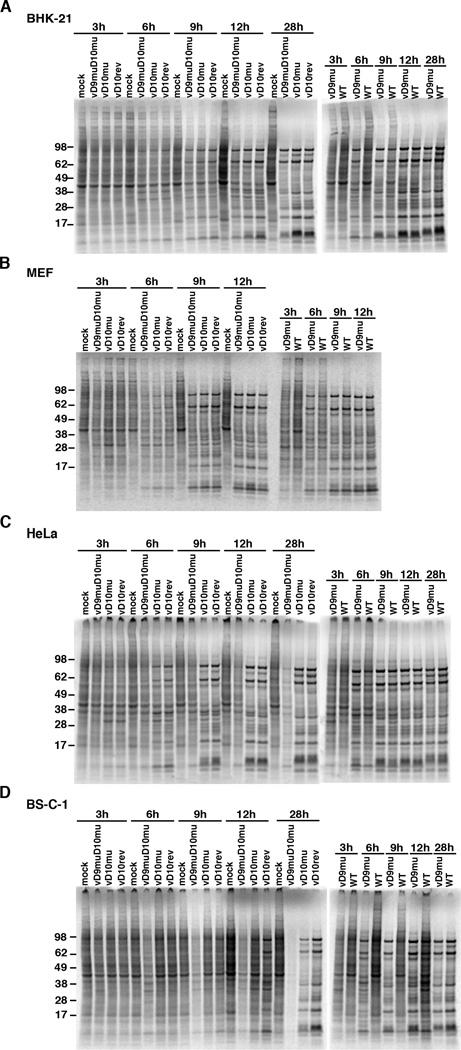

mRNA levels

Decreased viral protein synthesis could be due to a block in translation or reduced levels of mRNA or a combination of both. Previous studies showed that during a synchronous infection the steady state levels of early, intermediate and late VACV RNAs are determined by the onset of transcription as well as degradation (Baldick and Moss, 1993). Total RNA from infected non-permissive BS-C-1 and permissive BHK-21 cells was resolved by electrophoresis on glyoxal gels and analyzed by Northern blotting and autoradiography. DNA probes for the viral early transcript C11, the viral late transcript F17 and the cellular GAPDH RNA were prepared. The early C11 mRNA was detected at 3 h, peaked at 6 h and then gradually declined at 9 and 12 h in BHK-21 and BS-C-1 cells for all viruses (Figure 4A, Table S1). However, the decrease in C11 mRNA occurred more slowly in the cells infected with vD10mu and vD9muD10mu than with the WT-like vD10rev. A similar result with vD10mu and a D10 deletion mutant was reported previously and interpreted as RNA stabilization due to the absence of the D10 decapping enzyme (Liu et al., 2014; Parrish and Moss, 2006). In the presence of AraC, which prevents synthesis of the D10 decapping enzyme and other post-replicative proteins, there was little change in the amount of the C11 mRNA between 3 and 12 h (Figure 4A, Table S1).

Figure 4. Analysis of Viral and Cellular mRNAs and rRNAs.

BS-C-1 and BHK-21 cells were mock-infected or infected with 5 PFU/cell vD9muD10mu, vD10mu or vD10rev and the total RNAs were isolated at the indicated times and resolved on glyoxal gels. The RNAs were transferred to a nylon membrane, incubated with radioactive probes to the viral early C11 (A), the viral late F17 (B) and cellular GAPDH (C) mRNAs, and visualized with a PhosphorImager. In panel (D), glyoxal gels containing RNAs from BHK-21 and BS-C-1 cells that were mock-infected or infected in the absence or presence of AraC for the indicated times were stained with ethidium bromide. The RNAs were detected by fluorescence and reverse images are shown. The size in kb and positions of size markers are shown on the left. The major upper and lower bands represent the 28Sand 18S rRNAs, respectively.

Due to the requirement for viral DNA replication and intermediate gene expression, the late F17 mRNA was first detected in significant amounts at 6 h in BHK-21 and BS-C-1 cells and was not found in the presence of AraC (Fig. 4B, Table S1). The F17 mRNA increased from 6 to 12 h in BHK-21 and BS-C-1 cells that were infected with vD10rev and vD10mu. There was a higher amount of F17 mRNA in cells infected with vD10mu than vD10rev as previously reported (Liu et al., 2014). For vD9muD10mu, the pattern was very different in permissive BHK-21 cells compared to non-permissive BS-C-1 cells. In BHK-21 cells infected with vD9muD10mu, F17 mRNA increased between 6 and 12 h (Fig. 4B, Table S1). In BS-C-1 cells infected with vD9muD10mu, the amount of F17 mRNA was similar to that of vD10rev and vD10mu at 6 h indicating that late transcription was not impaired. However, the steady state amount of F17 mRNA sharply decreased at 9 and 12 h (Fig. 4B, Table S1) suggesting accelerated degradation.

Cellular mRNAs are degraded in cells infected with WT VACV (Rice and Roberts, 1983; Yang et al., 2010). At 3 and 6 h after infection with each of the viruses, the amount of GAPDH mRNA was similar to the steady state amount in mock-infected cells (Figure 4C, Table S1). However, at 9 and 12 h, there was an abrupt decline in the amounts of GAPDH mRNA, which was more severe in BS-C-1 cells than in BHK-21 cells. The decline occurred even with vD10rev and may be partially due to inhibition of cellular mRNA synthesis (Puckett and Moss, 1983).

Degradation of rRNA

Further analysis indicated that rRNA was degraded in BS-C-1 cells infected with vD9muD10mu. Ethidium bromide staining of the glyoxal gels used for Northern blotting demonstrated degradation of both the 28S and 18S rRNA subunits in non-permissive BS-C-1 cells that were infected with vD9muD10mu (Figure 4D). Degradation and specific cleavage products were detectable at 6 h and progressed over time. There was massive rRNA degradation at 9 h and 12 h (Figure 4D), correlating with the diminution of viral late mRNA at those times in BS-C-1 cells infected by vD9muD10mu. Slight rRNA degradation was also noted in BS-C-1 cells infected with vD10mu at late times but not with vD10rev (Figure 4D). In contrast, no rRNA degradation was detected in permissive BHK-21 cells infected with any of the viruses. Furthermore, rRNA degradation did not occur in BS-C-1 cells infected in the presence of AraC (Figure 4D), indicating that the trigger for rRNA degradation occurred post-replicatively. mRNA and rRNA degradation and the accumulation of rRNA cleavage products are signatures of the activation of RNase L, a single-strand specific endonuclease that is usually present in an inactive state (Silverman, 2007). RNase L is activated by 2’5’-oligoadenylates (2-5A) synthesized by 2’5’-oligoadenylate synthetase (OAS). OAS activity depends on interaction with dsRNA, which increases post-replicatively in cells infected with VACV as shown below.

An A549 human alveolar epithelial cell line stably transfected with shRNase L (S. Banerjee, A. Chakrabarti and R.H. Silverman, J. Virology, in press) was used to confirm that rRNA break-down was due to RNase L. The extent of RNase L knock-down is shown in Figure S4A. The shControl and shRNaseL cells were mock infected or infected with vD10rev, vD9muD10mu or an E3 deletion mutant (vΔE3L) for 14 h in the presence or absence of AraC. The vΔE3L was used a positive control since the mutant is susceptible to RNase L activation (Xiang et al., 2002). Cleavage of 28S and 18S RNA occurred in the A549 control cells infected with the three strains of VACV but was greatest in the vD9muD10mu and vΔE3L mutants (Figure S4B). However, much less rRNA degradation occurred in the shRNaseL A549 cells (Figure S4B), confirming that the virus-induced degradation was RNaseL mediated. Nevertheless, the knock-down of RNase L was insufficient to confer replication of either vD9muD10mu or vΔE3L (data not shown).

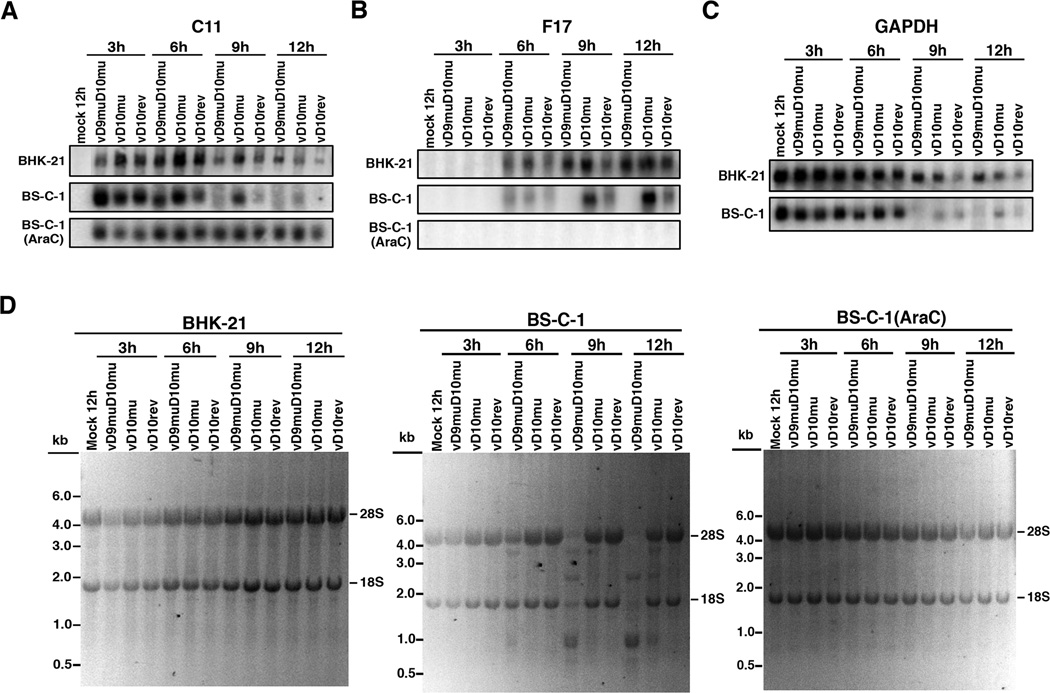

Accumulation of dsRNA

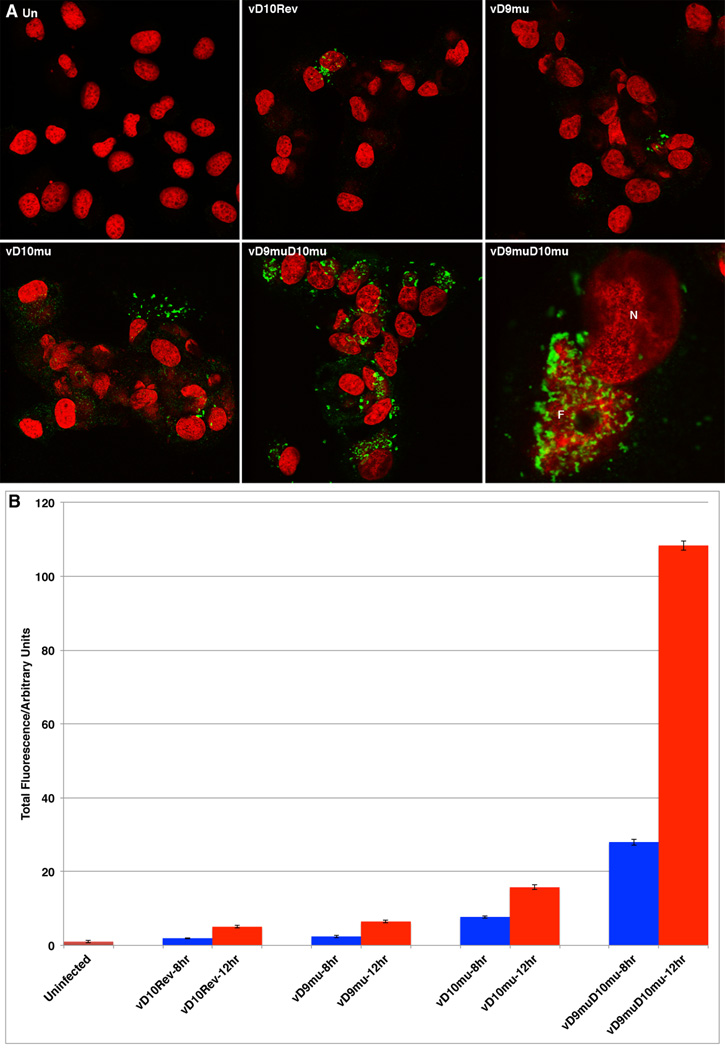

To determine whether the accumulation of dsRNA correlated with rRNA cleavage, we used the well-characterized J2 MAb that is specific for dsRNA of at least 40 bp (Bonin et al., 2000; Marshall et al., 2009; Schonborn et al., 1991; Targett-Adams et al., 2008) and has been reported to detect dsRNA in cells infected with VACV (Weber et al., 2006; Willis et al., 2011). BS-C-1 cells were infected with vD10rev, vD9mu, vD10mu and vD9muD10mu and fixed at 8 and 12 h after infection. The cells were stained with the dsRNA-specific J2 MAb; DAPI was used to visualize DNA in the nucleus and virus factories in the cytoplasm. Nearly all cells infected with vD9muD10mu exhibited bright dsRNA-staining at 12 h, which at higher magnification appeared to be associated with factories (Figure 5A). There were few bright dsRNA-staining cells infected with vD10mu, only occasional bright dsRNA-staining cells infected with vD9 or vD10rev and only dim staining of uninfected cells (Figure 5A). Co-staining with antibody to the viral A11 protein was used to verify the completeness of the infections with vD10rev, vD10mu and vD9muD10mu (not shown).

Figure 5. Confocal Microscopic Imaging of dsRNA.

BS-C-1 cells were infected with 5 PFU/cell of vD10rev, vD9mu, vD10mu or vD9muD10mu. At 8 and 12 h after infection, the cells were fixed and stained with the J2 mouse MAb specific for dsRNA followed by conjugated anti-mouse antibody and DAPI. (A) Representative images are shown. dsRNA: green; DNA: red. (B) Fluorescence intensity per cell was determined using Imaris imaging software. Cumulative intensity was calculated automatically for 50 tiles containing approximately 1,200 to 4,500 cells. After normalization for the number of cells in the different samples, the data were plotted as the average mean fluorescence intensity.

The relative amounts of dsRNA were calculated from the fluorescence intensity, which was determined using Imaris image processing software. The strongest signals were obtained from cells infected with vD9muD10mu and this increased from 8 to 12 h to a level of ~100-fold more than in uninfected cells, ~15-fold higher than in cells infected with vD10rev and ~7-fold higher than in cells infected with vD10mu (Figure 5B). Addition of the DNA replication inhibitor AraC, which blocks the formation of large amounts of complementary VACV RNA (Boone et al., 1979) and prevented the breakdown of rRNA in BS-C-1 cells infected with vD9muD10mu (Fig. 4D) also prevented the increase in dsRNA (Fig. S5). Thus, the degradation of mRNA and rRNA in cells infected with vD9muD10mu correlated with greatly increased dsRNA.

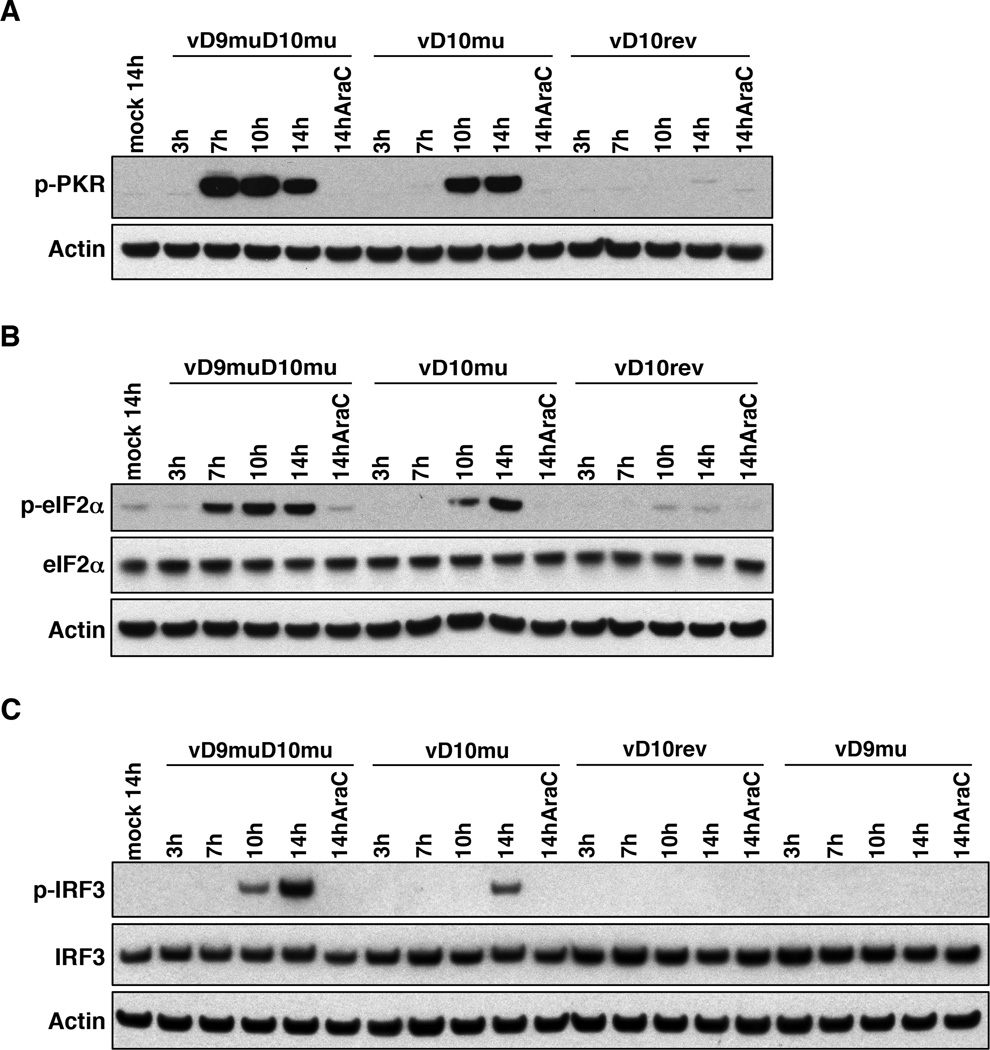

Phosphorylation of PKR, eIF2α and IRF3

In addition to activating OAS and RNase L, dsRNA induces the phosphorylation of PKR, which phosphorylates the translation initiation factor eIF2α (DeWitte-Orr and Mossman, 2010). BS-C-1 cells infected with vD9muD10mu induced strong phosphorylation of PKR and eIF2α by 7 h, whereas phosphorylation of these proteins occurred later following vD10mu infection and was minimal with vD10rev (Figure 6A, B). Moreover, phosphorylation of PKR and eIF2α was almost completely prevented by AraC (Fig. 6A, B). Similarly, IRF3 was phosphorylated by 10 h in BS-C-1 cells infected with vD9muD10mu, whereas phosphorylation occurred later and to a lesser extent following infection with vD10mu and was undetectable with vD10rev or vD9mu (Figure 6C). AraC also prevented phosphorylation of IRF3 (Figure 6C).

Figure 6. Phosphorylation of PKR, eIF2a and IRF3.

BS-C-1 cells were mock-infected or infected with vD10rev, vD10mu, vD9mu and vD9muD10mu in the absence or presence of AraC. At indicated hours the cells were lysed and the lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with rabbit MAbs to phosphorylated PKR (p-PKR), eIF2α, phosphorylated eIF2α (p-eIF2α), IRF3, phosphorylated IRF3 (p-IRF3) and rabbit polyclonal antibody to actin followed by secondary antibody conjugated to peroxidase.

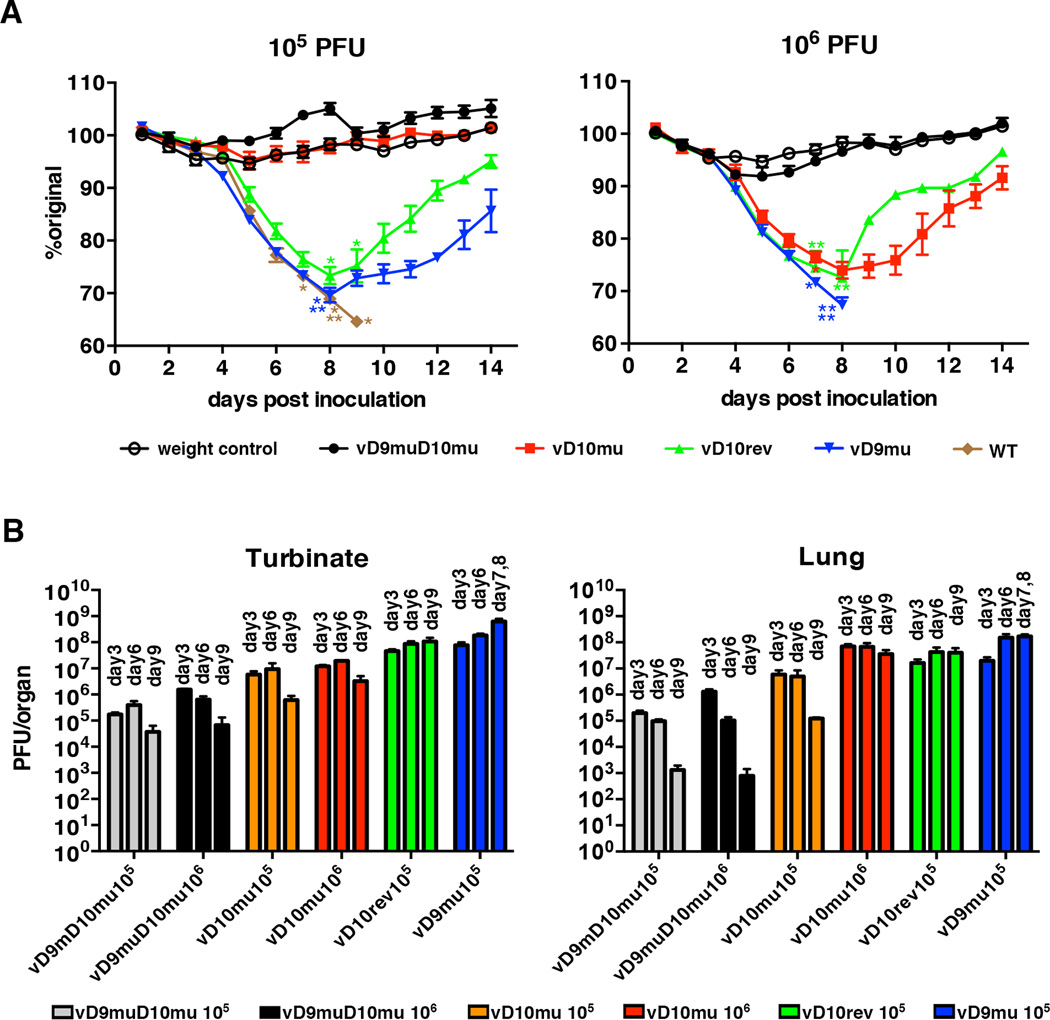

Attenuation of the vD9muD10mu in Mice

We previously reported that vD10mu was modestly attenuated in mice, even though it replicated well in MEFs (Liu et al., 2014). It was therefore of interest to determine the degree of attenuation of vD9muD10mu, which also replicated in MEFs. The Western Reserve (WR) strain of VACV, used as the parent virus to construct the decapping mutants, is highly pathogenic for BALB/c mice inoculated by the intranasal route (Law et al., 2005; Williamson et al., 1990). Virus spread with the highest titers in the nasal turbinates and lungs accompanies weight loss; the LD50 is approximately 5×104 PFU for the WR strain. In the present study, 6-weeks old BALB/c mice were infected intranasally with several doses of WT, vD10rev, vD9mu, vD10mu and vD9muD10mu. The mice were inspected for signs of morbidity and weighed daily. According to NIH protocols, mice that lose 30% of their weight must be euthanized. At the 105 PFU challenge dose, severe weight loss and deaths occurred with the WT, vD10rev, vD9mu but not with vD10mu or vD9muD10mu (Figure 7A, left panel). At the 106 PFU dose, the mice infected with vD10mu also showed severe weight loss and one death, whereas still no weight loss or death occurred with vD9muD10mu (Figure 7A, right panel) indicating extreme attenuation.

Figure 7. Effect of D9 and D10 Mutations on Virulence in Mice.

(A) Weight loss. BALB/c mice in groups of 5 were infected intranasally with 105 or 106 PFU of WT VACV, vD10rev, vD10mu, vD9mu or vD9muD10mu. The mice were weighed daily and euthanized if their weight dropped by 30%. Asterisks indicate day of death or euthanasia of individual mice. Bars indicate standard error of the mean (SEM). (B) Organ titers. BALB/c mice in groups of 4 were infected intransally with 105 or 106 PFU of vD10mu or vD9muD10mu or 105 PFU vD10rev or vD9mu. On the days indicated, the turbinates and lungs of individual mice were homogenized and the virus titers determined by plaque assay on BHK-21 cells. Bars indicate SEM.

To further investigate the attenuation of vD9muD10mu, the amounts of virus in nasal turbinates and lungs at days 3, 6 and 9 were determined following challenge with non-lethal doses of vD9muD10mu, vD10mu, vD9mu and vD10rev (Figure 7B). At both105 and 106 PFU challenge doses of vD9muD10mu, the virus titers in the nasal turbinates and lungs were significantly less than that obtained after infection with 105 PFU of vD10rev and vD9mu (p≤ 0.0007, Mann-Whitney test on combined titers for days 3, 6 and 9). In addition, there was significantly less virus in the turbinates and lungs of mice infected with 105 PFU of vD9muD10mu compared to 105 PFU of vD10mu (p<0.005) and 106 PFU of vD9muD10mu compared to 106 PFU of vD10mu (p≤0.0003). Very little vD9muD10mu was recovered from the other organs (spleen, liver and ovaries) at either challenge dose of vD9muD10mu (not shown).

The VACV antibody titers, determined on pooled sera from surviving mice at 3 weeks after intranasal infection (Figure S6A), correlated directly with the extent of virus spread (Figure 7B). The antibody titers of mice were 105 PFU vD9muD10mu < 106 PFU vD9muD10mu < 105 PFU vD10mu < 106 PFU vD10mu = 105 PFU vD10rev. Nevertheless, the immune responses of even the highly attenuated vD9muD10mu virus were sufficient to protect mice against a lethal challenge with pathogenic VACV (Figure S6B).

DISCUSSION

dsRNA has been considered to be the most important viral pathogen-associated molecular pattern (DeWitte-Orr and Mossman, 2010; Silverman, 2007). Nevertheless, dsRNA is produced during replication of most RNA and DNA viruses. For dsDNA viruses, complementary RNA can arise by convergent transcription from opposite DNA strands and in the case of VACV is exacerbated by inefficient transcription termination at post-replicative times. Approximately 15% of the polyadenylated RNA synthesized at intermediate and late times of VACV replication can anneal to form long intermolecular duplexes with single-stranded tails, whereas very little complementary RNA is made at early times or when AraC inhibits viral DNA replication (Boone et al., 1979). Hybridization studies indicated that the complementary sequence mapped to numerous genes along the genome (Boone et al., 1979), which was confirmed recently by RNA-seq (Yang et al. 2010). Some of the complementary RNA made at late times appears to exist in a double-stranded form when isolated directly from cells omitting phenol extraction (Colby and Duesberg, 1969). Cytoplasmic sensors of dsRNA include PKR, OAS, RIG-1, MDA5, NALP3 and more may await discovery (DeWitte-Orr and Mossman, 2010). Activation of these sensors generally leads to suppression of virus replication: PKR inhibits translation by phosphorylation of the translation initiation factor eIF2α and has additional antiviral activities; OAS synthesizes 2-5A oligonucleotides that activate RNase L, which cleaves single stranded RNAs including mRNA and rRNA; RIG-1 and MDA5 recruit IPS-1 resulting in phosphorylation of IRF3 and induction of interferon and NALP-3 inducing inflammasome formation. Here we provide evidence that an important biological role of the VACV decapping enzymes is to prevent accumulation of dsRNA and the subsequent activation of antiviral responses.

RNA-seq studies demonstrated accelerated decay of thousands of host mRNAs including those involved in innate immune responses by 4 h after infection with VACV, suggesting that the decapping enzymes may contribute to protection against host antiviral responses (Yang et al. 2010). By accelerating decay of viral mRNAs, the decapping enzymes may also sharpen the transition between early, intermediate and late stages of infection. To further investigate the roles of the VACV decapping enzymes, we made point mutations that were previously shown to specifically and completely inactivate catalytic activity of both D9 and D10 in vitro (Parrish and Moss, 2007; Parrish et al., 2007) without perturbing neighboring genes. Inactivation of the D9 decapping enzyme had no effect on virus replication and mutation of D10 had only a modest deleterious effect, whereas mutation of both drastically reduced replication in monkey and human cells and caused extreme attenuation in a murine respiratory infection model. The severe phenotype resulting from inactivation of both decapping enzymes indicated that they compensate for each other, consistent with their similar decapping activities in vitro (Parrish and Moss, 2006, 2007). Since inactivation of D10 alone increased mRNA stability (Liu et al., 2014), we had anticipated that inactivation of both decapping enzymes would increase stability even more. However, because our mutant still contains the E3 dsRNA binding protein, we did not anticipate that increased late complementary RNA would trigger a potent dsRNA response. Therefore, it was surprising to find drastic inhibition of protein synthesis and virtually complete loss of mRNA and intact rRNA in cells infected with the double mutant. Further studies revealed that this phenotype correlated with a huge increase in dsRNA, activation of RNase L and phosphorylation of PKR, eIF2α and IRF3. Very little dsRNA was present in BS-C-1 cells infected with WT revertant virus or the D9 mutant consistent with the absence of PKR phosphorylation and rRNA degradation. More dsRNA accumulated in cells infected with the D10 mutant, but this was still much less than with the double mutant, and PKR phosphorylation was delayed and only slight degradation of rRNA was noted. The dsRNA evidently formed from viral RNA since: (i) dsRNA was not reliably detected in uninfected cells; (ii) dsRNA increased from 8 to 12 h after infection with vD9muD10mu, which correlated with the time of synthesis of complementary viral mRNA during infection with VACV (Boone et al., 1979); (iii) AraC, which prevents synthesis of post-replicative viral complementary RNAs, prevented accumulation of dsRNA and rRNA breakdown mediated by RNase L activation; (iv) dsRNA localized to virus factories, the site of viral intermediate and late transcription. Increased 2-5A, the product of OAS, was previously shown to increase during WT VACV infection but rRNA cleavage was delayed (Rice et al., 1984); the kinetics of formation and inhibition by AraC led those authors to suggest that dsRNA derived from late complementary sequences was responsible. Activation of the RNase L pathway was previously described for a VACV temperature-sensitive A18 DNA helicase mutant, which was attributed to increased dsRNA resulting from failure to control the length of late transcripts (Bayliss and Condit, 1993; Bayliss and Condit, 1995; Simpson and Condit, 1994, 1995). Some increased dsRNA has also been reported for a K1L deletion mutant, although the mechanism remains to be determined (Willis et al., 2011).

RNAs decapped by D9 and D10 have 5’ monophosphate ends making them susceptible to 5’ exonuclease digestion (Parrish and Moss, 2007; Parrish et al., 2007). Although VACV does not appear to encode a RNA 5’ exonuclease, a human genome-wide siRNA screen indicated the importance of Xrn1, the major cytoplasmic RNA 5’ exonuclease, for VACV replication and spread (Sivan et al., 2013). Moreover, in the accompanying report Burgess and Mohr (Burgess and Mohr, 2015) confirm the inhibition of VACV replication by Xrn1 knock-down and further demonstrate the accumulation of dsRNA and phosphorylation of PKR and eIF2α. Thus it is likely that D9 and D10 act coordinately with Xrn1 to mediate mRNA decay and prevent accumulation of dsRNA. However, whether these activities reduce the annealing of complementary RNA or degrade dsRNA remains to be determined. With regard to the latter, there is evidence that Xrn1 associates with other proteins including a helicase that could help unwind dsRNA and allow degradation (Jones et al., 2012). Xrn1 also associates with the cytoplasmic DCP1/DCP2 decapping complex but evidently the host enzymes are unable to compensate for loss of D9 and D10 during VACV infection.

Poxviruses encode several early proteins that prevent the cell from recognizing or responding to dsRNA. The E3 protein encoded by VACV binds and sequesters dsRNA (Chang and Jacobs, 1993; Chang et al., 1992) and the K3 protein inhibits eIF2α phosphorylation by PKR (Carroll et al., 1993; Davies et al., 1992). The K1 protein has recently been reported to reduce the amount of dsRNA (Willis et al., 2011). We demonstrated that E3 was expressed in cells infected with vD9muD10mu but apparently the protein was overwhelmed by the huge amounts of dsRNA that accumulated in the absence of the viral decapping enzymes. Although the mechanism by which binding of E3 to dsRNA prevents activation of the innate immune pathways is not known, stoichiometric amounts are presumably needed. Therefore, the phenotype of vD9muD10mu might be reversed by greatly overexpressing E3 before dsRNA accumulates. We have moderately overexpressed E3 by transfection but only a slight increase in viral protein synthesis and plaque size was observed (RL, unpublished). Further efforts will be made to more highly overexpress E3.

It makes sense that the host range restriction of the VACV decapping mutant is similar to that previously described for a deletion mutant of the E3 dsRNA binding protein i.e. chick embryo fibroblasts, rabbit kidney-13 and hamster BHK-21 cells are permissive and African green monkey cells and human HeLa cells are non-permissive (Beattie et al., 1996; Langland and Jacobs, 2002; Xiang et al., 2002). In future experiments, we will address the question of how certain cells can support replication of the VACV double decapping enzyme mutant without causing degradation of RNA or inhibition of viral protein synthesis. Susceptibility may be related to the endogenous levels of dsRNA sensors, since activation of antiviral pathways depends on their levels in addition to dsRNA. For example, cells with lower levels of OAS are more resistant to dsRNA (Stark et al., 1979; Zhao et al., 2013). On the other hand, mouse macrophages have high levels of OAS (Zhao et al., 2013) and this may contribute to the severe attenuation of vD9muD10mu seen after intranasal infection of mice compared to MEFs. In addition, since OAS and PKR are interferon inducible, interferons could also contribute to attenuation in mice, while the replication of vD9muD10mu was not impaired in MEF cells. We plan to further study the relationship between specific dsRNA sensors and host restriction of vD9muD10mu in cells and animals.

Experimental Procedures

Cells and Viruses

BS-C-1, HeLa, RK-13 and BHK-21 cells were grown in minimum essential medium with Earle’s balanced Salts supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 units penicillin and 100 µg streptomycin per ml (Quality Biological, Inc.) and containing 8% fetal bovine serum (FBS)(Sigma-Aldrich). C57BL/6 MEFs (ATCC SCRC-1008) were grown in Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium (Quality Biological, Inc.) supplemented with 4 mM L-glutamine, 20% FBS, 100 units penicillin and 100 µg streptomycin per ml.

Construction of Recombinant Viruses

VACV recombinants were derived from the WR strain of VACV (ATCC VR-1354). vD10mu, with catalytic site mutations E144Q and E145Q and the wild type vD10rev viruses were described (Liu et al., 2014). The D9 mutant vD9mu was constructed by replacing the EGFP ORF in vΔD9 (Parrish and Moss, 2006) with a D9R ORF containing the catalytic site mutations E129Q and E130Q. The vD9muD10mu double mutant was generated in two steps: homologous recombination was used to replace the D9 ORF of vD10mu with the EGFP ORF; second the EGFP ORF was replaced by the D9 ORF with active site mutations E129Q and E130Q. Plaques were picked under a fluorescent microscope and clonally purified. The modified regions of the recombinant viruses were PCR amplified and sequenced.

Virus Purification

Recombinant viruses, grown in BHK-21 cells, were purified by centrifugation through a 36% sucrose cushion followed by centrifugation through a 24%-40% sucrose gradient as described (Liu et al., 2014). BHK-21 cells were used for plaque assay to determine infectivity.

Western Blotting

Western blotting was carried out by electrophoresis on 4–12% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gels (Life Technologies) and transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane with an iBlot system (Life Technologies). The membrane was blocked in 5% non-fat milk in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) with 0.05% tween-20 (PBST) for 1 h, washed with PBST, and incubated with the primary antibody in PBST containing 5% non-fat milk for 1 h. The membrane was washed with PBST, and incubated with the secondary antibody conjugated by horseradish peroxidase in PBST with 5% non-fat milk for 1 h. After washing the membrane, the amount of protein bound by the secondary antibody was visualized by SuperSignal West Femto substrates (Thermo Scientific). Antibodies are described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures. In Figure 6C, cells were lysed with buffer containing phosphatase inhibitors as follow: 1 mM sodium orthovanadate (Fisher), 2 mM sodium pyrophosphate (Sigma-Aldrich), 50 mM glycerol-2-phosphate disodium (Sigma-Aldrich), and 50 mM sodium fluoride (Sigma-Aldrich).

Pulse-Labeling Proteins

Cells on 12-well plates were infected with 5 PFU/cell of VACV. After 1.5 h, the cells were washed and incubated with fresh medium. At intervals, the medium was replaced with methionine- and cysteine-free RPMI 1640 (Sigma-Aldrich) containing 2.5% dialyzed FBS (Hyclone); after 30 min the medium was replaced with fresh methionine-and cysteine-free RPMI 1640 containing 100 µCi/ml of [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine (Perkin Elmer) for 30 min. Cells were harvested, washed, lysed in buffer containing 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 10 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 0.5% NP-40, and 1 X EDTA-free protease inhibitors (Roche), in the presence of 1,000 gel units of micrococcal nuclease (New England Biolabs) at room temperature for 15 min. Lithium dodecyl sulfate sample and reducing buffers (1 X NuPAGE; Life Technologies) were added to the lysates, followed by heating at 70°C for 15 min. Proteins were resolved on 4–12% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gels (Life Technologies), dried on Whatmann paper, and exposed to a PhosphorImager screen and visualized by a Molecular Dynamics Typhoon 9410 Molecular Imager (GE Amersham).

Analysis of RNA by Northern Blotting

Total RNA was isolated using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen), resolved by electrophoresis on a glyoxal gel (Life Technologies) and electrophoretically transferred to a nylon membrane (Liu et al., 2014). DNA probes labeled with [α-32P]dCTP (Perkin Elmer) were made with a Decaprime II random priming kit (Life Technologies) using a 300–400 nucleotide PCR fragment amplified from the gene of interest. The probed membrane was exposed to a PhosphorImager screen as above. Quantitation was performed with GelEval 1.35 (FrogDance software; http://www.frogdance.dundee.ac.uk).

Analysis of dsRNA by Confocal Microscopy

BS-C-1 cells were mock-infected or infected with 5 PFU/cell of virus for 8 and 12 h, after which the cells were fixed and stained essentially as described above. The J2 MAb (SCICONS, Szirak, Hungary) was diluted 1:100 and incubated with the cells overnight. After washing, secondary anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 was applied at a 1:100 dilution for 6 h. Nuclei were stained with DAPI as above. Confocal images were collected using a Leica DMI6000 confocal microscope enabled with 40× oil immersion objective NA 1.32. Images were acquired using constant laser intensity for Argon Laser and 488 nm wave length for Alexa 488 excitation and photons were collected using constant photomultiplier electronic gain between the samples to quantify the differences in absolute intensity levels. Images were collected and processed using Imaris 7.1 (Bitplane AG, Zurich, Switzerland) and Adobe Photoshop CS3 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA) to adjust brightness. For quantification, images were collected using an automated tiling method to obtain an unbiased data pool from 50 to 100 tiles. Acquired images were further analyzed using Imaris image processing software to calculate the absolute total intensity per cell. Cumulative intensities were plotted as average mean intensity normalized to the uninfected sample.

Determination of Virulence in Mice

Animal study protocols were approved by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Animal Care and Use Committee. The virulence of recombinant viruses was determined following intranasal inoculation by comparing the weight loss and viral titers in the organs as previously described (Liu et al., 2014). Mice were euthanized when they lost 30% of their original weight. Mann-Whitney test was employed to determine significance of differences in virus titers of lungs and turbinates. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism version 6.00 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Catherine Cotter, Wei Xao and Andrea Weisberg in the Laboratory of Viral Diseases for help with cell cultures, determination of antibody titers and transmission electron microscopy, respectively; Sundar Ganesan in the Biological Imaging Section for quantification of fluorescence microscopy; and members of the Comparative Medicine Branch for maintaining and weighing mice. David Evans provided the MAb to I3 and Robert Silverman generously provided shRNase L A543 cells prior to publication. During the course of this study, Hannah Burgess and Ian Mohr kindly shared with us their data on the effects of Xrn1 on vaccinia virus infection. The research was supported by the Division of Intramural Research, NIAID, NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

SL organized and carried out the majority of experiments and contributed to the preparation of the manuscript; GCK made the confocal images and quantified proteins and dsRNA; RL organized and performed experiments; LSW helped with the mouse studies; BM designed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript.

References

- Baldick CJ, Jr, Moss B. Characterization and temporal regulation of mRNAs encoded by vaccinia virus intermediate stage genes. J Virol. 1993;67:3515–3527. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3515-3527.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa E, Moss B. mRNA (nucleoside-2'-)-methyltransferase from vaccinia virus. Purification and physical properties. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:7692–7697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss CD, Condit RC. Temperature-sensitive mutants in the vaccinia virus A18R gene increases double-stranded RNA synthesis as a result of aberrant viral transcription. Virology. 1993;194:254–262. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss CD, Condit RC. The vaccinia virus A18R gene product is a DNA-dependent ATPase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1550–1556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beattie E, Kauffman EB, Martinez H, Perkus ME, Jacobs BL, Paoletti E, Tartaglia J. Host-range restriction of vaccinia virus E3L-specific deletion mutants. Virus Genes. 1996;12:89–94. doi: 10.1007/BF00370005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonin M, Oberstrass J, Lukacs N, Ewert K, Oesterschulze E, Kassing R, Nellen W. Determination of preferential binding sites for anti-dsRNA antibodies on double-stranded RNA by scanning force microscopy. RNA. 2000;6:563–570. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200992318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone RF, Parr RP, Moss B. Intermolecular duplexes formed from polyadenylated vaccinia virus RNA. J Virol. 1979;30:365–374. doi: 10.1128/jvi.30.1.365-374.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess H, Mohr I. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Carroll K, Elroy-Stein O, Moss B, Jagus R. Recombinant vaccinia virus K3L gene product prevents activation of double-stranded RNA-dependent, initiation factor 2 alpha-specific protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:12837–12842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H-W, Jacobs BL. Identification of a conserved motif that is necessary for binding of the vaccinia virus E3L gene products to double-stranded RNA. Virology. 1993;194:537–547. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HW, Watson JC, Jacobs BL. The E3L gene of vaccinia virus encodes an inhibitor of the interferon-induced, double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4825–4829. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.4825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby C, Duesberg PH. Double-stranded RNA in vaccinia virus infected cells. Nature. 1969;222:940–944. doi: 10.1038/222940a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies MV, Elroy-Stein O, Jagus R, Moss B, Kaufman RJ. The vaccinia virus K3L gene product potentiates translation by inhibiting double-stranded-RNA-activated protein kinase and phosphorylation of the alpha subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2. J Virol. 1992;66:1943–1950. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.1943-1950.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWitte-Orr SJ, Mossman KL. dsRNA and the innate antiviral immune response. Future Virol. 2010;5:325–341. [Google Scholar]

- Dunckley T, Parker R. The DCP2 protein is required for mRNA decapping in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and contains a functional MutT motif. Embo J. 1999;18:5411–5422. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.19.5411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds M, Vaughan MH, Jr, Nakazato H. Polyadenylic acid sequences in the heterogeneous nuclear RNA and rapidly-labeled polyribosomal RNA of HeLa cells: possible evidence for a precursor relationship. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1971;68:1336–1340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.6.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuichi Y, Morgan M, Shatkin AJ, Jelinek W, Salditt-Georgieff M, Darnell JE. Methylated, blocked 5 termini in HeLa cell mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:1904–1908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.5.1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garneau NL, Wilusz J, Wilusz CJ. The highways and byways of mRNA decay. Nature reviews. 2007;8:113–126. doi: 10.1038/nrm2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershon PD, Ahn BY, Garfield M, Moss B. Poly(A) polymerase and a dissociable polyadenylation stimulatory factor encoded by vaccinia virus. Cell. 1991;66:1269–1278. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu CL, Stevens A. Yeast cells lacking 5'-->3' exoribonuclease 1 contain mRNA species that are poly(A) deficient and partially lack the 5' cap structure. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4826–4835. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.8.4826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CI, Zabolotskaya MV, Newbury SF. The 5' --> 3' exoribonuclease XRN1/Pacman and its functions in cellular processes and development. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2012;3:455–468. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langland JO, Jacobs BL. The role of the PKR-inhibitory genes, E3L and K3L, in determining vaccinia virus host range. Virology. 2002;299:133–141. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law M, Putz MM, Smith GL. An investigation of the therapeutic value of vaccinia-immune IgG in a mouse pneumonia model. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:991–1000. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80660-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SW, Wyatt LS, Orandle MS, Minai M, Moss B. The D10 decapping enzyme of vaccinia virus contributes to decay of cellular and viral mRNAs and to virulence in mice. J Virol. 2014;88:202–211. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02426-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall EE, Bierle CJ, Brune W, Geballe AP. Essential role for either TRS1 or IRS1 in human cytomegalovirus replication. J Virol. 2009;83:4112–41120. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02489-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin SA, Paoletti E, Moss B. Purification of mRNA guanylyltransferase and mRNA (guanine 7-)methyltransferase from vaccinia virus. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:9322–9329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss B. Poxviridae. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields Virology. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013. pp. 2129–2159. [Google Scholar]

- Moss B, Rosenblum EN, Paoletti E. Polyadenylate polymerase from vaccinia virions. Nature (New Biol) 1973;245:59–63. doi: 10.1038/newbio245059a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish S, Moss B. Characterization of a vaccinia virus mutant with a deletion of the D10R gene encoding a putative negative regulator of gene expression. J Virol. 2006;80:553–561. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.2.553-561.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish S, Moss B. Characterization of a second vaccinia virus mRNA-decapping enzyme conserved in poxviruses. J Virol. 2007;81:12973–12978. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01668-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish S, Resch W, Moss B. Vaccinia virus D10 protein has mRNA decapping activity, providing a mechanism for control of host and viral gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:2139–2144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611685104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdiguero B, Esteban M. The interferon system and vaccinia virus evasion mechanisms. J Interferon and Cytokine Res. 2009;29:581–598. doi: 10.1089/jir.2009.0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puckett C, Moss B. Selective transcription of vaccinia virus genes in template dependent soluble extracts of infected cells. Cell. 1983;35:441–448. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resch W, Weisberg AS, Moss B. Vaccinia virus nonstructural protein encoded by the A11R gene is required for formation of the virion membrane. J Virol. 2005;79:6598–6609. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.11.6598-6609.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice AP, Roberts BE. Vaccinia virus induces cellular mRNA degradation. J Virol. 1983;47:529–539. doi: 10.1128/jvi.47.3.529-539.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice AP, Roberts WK, Kerr IM. 2-5A accumulates to high levels in interferon-treated, vaccinia virus-infected cells in the absence of any inhibition of virus replication. J Virol. 1984;50:220–228. doi: 10.1128/jvi.50.1.220-228.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochester SC, Traktman P. Characterization of the single-stranded DNA binding protein encoded by the vaccinia virus I3 gene. J Virol. 1998;72:2917–2926. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2917-2926.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schonborn J, Oberstrass J, Breyel E, Tittgen J, Schumacher J, Lukacs N. Monoclonal antibodies to double-stranded RNA as probes of RNA structure in crude nucleic acid extracts. Nucl Acids Res. 1991;19:2993–3000. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.11.2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman RH. Viral encounters with 2 ',5 '-oligoadenylate synthetase and RNase L during the interferon antiviral response. J Virol. 2007;81:12720–12729. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01471-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman RH, Skehel JJ, James TC, Wreschner DH, Kerr IM. rRNA cleavage as an index of ppp(A2'p)nA activity in interferon-treated encephalomyocarditis virus-infected cells. J Virol. 1983;46:1051–1055. doi: 10.1128/jvi.46.3.1051-1055.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DA, Condit RC. The vaccinia virus A18R protein plays a role in viral transcription during both the early and late phase of infection. J Virol. 1994;68:3642–3649. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.3642-3649.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DA, Condit RC. Vaccinia virus gene A18R encodes an essential DNA helicase. J Virol. 1995;69:6131–6139. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6131-6139.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivan G, Martin SE, Myers TG, Buehler E, Szymczyk KH, Ormanoglu P, Moss B. Human genome-wide RNAi screen reveals a role for nuclear pore proteins in poxvirus morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:3519–3524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300708110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark GR, Dower WJ, Schimke RT, Brown RE, Kerr IM. 2-5A synthetase: assay, distribution and variation with growth or hormone status. Nature. 1979;278:471–473. doi: 10.1038/278471a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark GR, Kerr IM, Williams BR, Silverman RH, Schreiber RD. How cells respond to interferons. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:227–264. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Targett-Adams P, Boulant S, McLauchlan J. Visualization of double-stranded RNA in cells supporting hepatitis C virus RNA replication. J Virol. 2008;82:2182–2195. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01565-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng M, Palaniyar N, Zhang WD, Evans DH. DNA binding and aggregation properties of the vaccinia virus I3L gene product. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21637–21644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton C, Slack S, Hunter AL, Ehlers A, Roper RL. Poxvirus orthologous clusters: toward defining the minimum essential poxvirus genome. J Virol. 2003;77:7590–7600. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.13.7590-7600.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Jiao X, Carr-Schmid A, Kiledjian M. The hDcp2 protein is a mammalian mRNA decapping enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12663–12668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192445599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber F, Wagner V, Rasmussen SB, Hartmann R, Paludan SR. Double-stranded RNA is produced by positive-strand RNA viruses and DNA viruses but not in detectable amounts by negative-strand RNA viruses. J Virol. 2006;80:5059–5064. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.10.5059-5064.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei CM, Gershowitz A, Moss B. Methylated nucleotides block 5' terminus of HeLa cell messenger RNA. Cell. 1975;4:379–386. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(75)90158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei CM, Moss B. Methylated nucleotides block 5'-terminus of vaccinia virus mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:318–322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.1.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson JD, Reith RW, Jeffrey LJ, Arrand JR, Mackett M. Biological characterization of recombinant vaccinia viruses in mice infected by the respiratory route. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:2761–2767. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-11-2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis KL, Langland JO, Shisler JL. Viral double-stranded RNAs from vaccinia virus early or intermediate gene transcripts possess PKR activating function, resulting in NF-kappa B activation, when the K1 protein Is absent or mutated. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:7765–7778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.194704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y, Condit RC, Vijaysri S, Jacobs B, Williams BRG, Silverman RH. Blockade of interferon induction and action by the E3L double-stranded RNA binding proteins of vaccinia virus. Journal of Virology. 2002;76:5251–5259. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.10.5251-5259.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Bruno DP, Martens CA, Porcella SF, Moss B. Simultaneous high-resolution analysis of vaccinia virus and host cell transcriptomes by deep RNA sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:11513–11518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006594107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Reynolds SE, Martens CA, Bruno DP, Porcella SF, Moss B. Expression profiling of the intermediate and late stages of poxvirus replication. J Virol. 2011;85:9899–9908. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05446-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Birdwell LD, Wu A, Elliott R, Rose KM, Phillips JM, Li Y, Grinspan J, Silverman RH, Weiss SR. Cell-type-specific activation of the oligoadenylate synthetase-RNase L pathway by a murine coronavirus. J Virol. 2013;87:8408–8418. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00769-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.