Summary

Genomic DNA replicates in a choreographed temporal order that impacts the distribution of mutations along the genome. We show here that DNA replication timing is shaped by genetic polymorphisms that act in cis upon megabase-scale DNA segments. In genome sequences from proliferating cells, read depth along chromosomes reflected DNA replication activity in those cells. We used this relationship to analyze variation in replication timing among 161 individuals sequenced by the 1000 Genomes Project. Genome-wide association of replication timing with genetic variation identified 16 loci at which inherited alleles associate with replication timing. We call these “replication timing quantitative trait loci” (rtQTLs). rtQTLs involved the differential use of replication origins, exhibited allele-specific effects on replication timing, and associated with gene expression variation at megabase scales. Our results show replication timing to be shaped by genetic polymorphism, and identify a means by which inherited polymorphism regulates the mutability of nearby sequences.

Introduction

Replication of eukaryotic genomes follows a strict temporal program, with each chromosome containing segments of characteristic early and late replication. This program is mediated by the locations and activation timing of replication origins along each chromosome (Rhind and Gilbert, 2013). Expressed genes tend to reside in early-replicating region of the genome (Rhind and Gilbert, 2013). Compared to early phases of replication, late phases of replication are faster, less structured (Koren and McCarroll, 2014), and more mutation-prone; late-replicating loci have elevated mutation rates in the human germ line (Stamatoyannopoulos et al., 2009), in somatic cells (Koren et al., 2012), and in cancer cells (Lawrence et al., 2013). Structural mutations and chromosome fragility are also more common in late-replicating genomic regions (Koren et al., 2012; Letessier et al., 2011). At the other extreme, chromosome fragility (and consequent mutations) are also increased at specific “early replicating fragile sites” (ERFSs), a subset of early replication origins at which interference between replication and transcription leads to double strand breaks (Barlow et al., 2013; Pederson and De, 2013; Drier et al., 2013). These aspects of genome replication are conserved all the way to prokaryotes, in which genes close to the replication origin have increased expression relative to genes close to the terminus (Slager et al., 2014; Rocha, 2008), essential genes tend to be co-oriented with the direction of replication fork progression (Rocha, 2008), and the rate of mutation gradually increases with distance from the origin (Sharp et al., 1989), although close proximity to the origin can lead to structural alterations under conditions of replication stress (Slager et al., 2014).

A genome's elaborate program of DNA replication is therefore strongly connected to genome function and evolution, and could in principle be an object of variation and selection itself. However, it is not known whether DNA replication timing varies among members of the same species, nor whether such variation is under genetic control. Previous studies have concluded that replication timing is globally similar among individuals of the same species (Ryba et al., 2010; Hiratani et al., 2008; Pope et al., 2011; Ryba et al., 2012; Mukhopadhyay et al., 2014). We hypothesized that this global similarity could still in principle coexist with inter-individual variation at many individual loci, and that such variation might be used to find genetic influences on replication timing.

Results

DNA replication timing varies among humans

DNA replication results in dynamic changes in the copy number of each genomic locus; the earlier a locus replicates, the greater its average copy number in replicating (S phase) cells. To profile these differences across the genome, we have previously isolated G1 and S phase cells using FACS (Figure 1A), sequenced the DNA from both cell cycle phases, and inferred replication timing from the long-range fluctuations in relative sequence abundance (the ratio of sequencing read depths from S- and G1-phase cells) along each chromosome (Figure 1B; Koren et al., 2012). To facilitate interpretation and comparison of replication profiles, we normalize replication timing to units of standard deviations (z-score units, with a genome-wide average of zero and standard deviation of one). Replication profiles provide information regarding the time of replication of each locus in the genome. They also provide the estimated locations of replication origins, which are inferred from peaks along the replication profiles, where replication is earlier than the replication of flanking sequences (Raghuraman et al., 2001; Hawkins et al., 2013); in mammalian genomes, replication peaks correspond to either single origins or clusters of closely-spaced replication origins. In previous analyses of replication timing in lymphoblastoid cell lines from six individuals, we compared the individual-averaged profiles to patterns of mutations and variation in the human genome (Koren et al., 2012), and compared the replication profiles of female active and inactive X chromosomes (Koren and McCarroll, 2014).

Figure 1. DNA replication timing varies among individuals at specific loci.

A. FACS-sorting cells by DNA content enables analysis of DNA copy number (by whole-genome sequencing) in G1 and S phase cells (adapted from Koren et al., 2012).

B. Analysis of the ratio of DNA copy number between S- and G1-phase cells along each chromosome allows the construction of replication timing profiles; early-replicating loci have a higher average copy number in S phase cells relative to late-replicating loci. Cells from different individuals show consistent replication timing programs across most of their genomes. In this and all subsequent figures, replication timing (and read depth) data are normalized to have a genome-wide mean of zero and standard deviation of one; the y-scale thus represents z-score units.

C. A genomic locus (gray shading) exhibits inter-individual variation in DNA replication timing, with only three of the six individuals exhibiting a replication origin peak structure at this locus. Black lines: smoothed replication profiles.

D. An overlay of replication profiles from two individuals reveals a locus with variation in origin activity.

E. The local distribution of replication timing measurements across many adjacent data windows allows statistical detection of replication timing variants. The example depicts the distributions in the genomic region shown in panel D.

F-G. Replication variants in which a replication origin (or origin cluster) is active in some individuals but inactive in others, as inferred from the presence or absence of a peak in the replication profiles.

H-I. Replication variants in which the average utilization or activation time of a replication origin varies among individuals, as inferred from differences in peak height.

We sought in the current work to better ascertain and understand inter-individual variation in DNA replication. The replication profiles of the six individuals closely matched one another across most of the genome (correlation coefficients r=0.91–0.97 among all comparisons; Figure 1B,C), consistent with earlier findings that profiles from different individuals are broadly similar at genomic scales (Ryba et al., 2010; Hiratani et al., 2008; Pope et al., 2011; Ryba et al., 2012; Mukhopadhyay et al., 2014). However, at scales of several hundred kilobases, we found that specific genomic loci exhibited clear differences in replication timing among the six individuals (Figure 1C). A systematic search for replication variation identified 221 replication-variant loci (Figure 1D-I; Supplementary Experimental Procedures), each of which spanned 0.2- 1.4 Mb (mean = 0.43 Mb). At most variant loci, individuals differed qualitatively in the usage of an origin (or origin cluster) (Figure 1C,D,F,G), as inferred from the presence of a peak in the replication profile; or quantitatively in the average utilization or activation time of a replication origin (Figure 1H,I), as inferred from variations in the height of a peak.

This analysis indicated substantial replication timing variation among humans, but did not establish whether any aspect of this variation is under genetic control. Importantly, other factors could in principle influence the observed inter-individual variations in replication timing, including epigenetic influences or even the growth states of the cells at the time of DNA harvesting and the transformation of the cells with EBV. To identify those replication phenotypes that consistently associate with specific alleles, genetic mapping requires analysis of DNA replication timing in far more individuals. But studies of replication timing to date have involved small numbers of samples.

DNA replication activity is visible in whole-genome sequence data

Whole genome sequencing is increasingly used to study DNA sequence variation in large numbers of humans; some studies, such as the 1000 Genomes Project, use DNA samples extracted from cultured, proliferating cells (The 1000 Genome Project Consortium, 2012). We hypothesized that active DNA replication might be visible in such data: the presence of S-phase cells in such cultures could in principle cause long-range fluctuations in DNA copy number (measured by read depth) along each chromosome, with early-replicating loci contributing more DNA than late-replicating loci.

Array- and sequencing-based profiles of DNA copy number have long been known to contain megabase-scale “wave” patterns of copy number fluctuations that correlate with large-scale patterns of GC content along mammalian chromosomes (Marioni et al., 2007; Diskin et al., 2008; van de Wiel et al., 2009; Lepretre et al., 2010; van Heesch et al., 2013; Aird et al., 2011). The sources of these GC-wave effects have been assumed to be technical. However, although GC content influences the efficiency of PCR amplification, GC-wave effects are present at megabase rather than sub-kilobase (amplicon) scales. Notably, GC content and DNA replication timing are highly correlated at megabase scales (Rhind and Gilbert, 2013), and DNA copy number is typically measured in cell populations that are derived from asynchronous, proliferating cell cultures that contain many cells in S phase. In fact, a recent study (contemporaneous with this work) noted a visual resemblance and statistical correlation between a copy number profile (derived by array CGH) and DNA replication timing profiles (Manukjan et al., 2013).

We designed a series of tests of the hypothesis that variation in sequencing coverage along chromosomes arises from true heterogeneity in DNA copy number due to ongoing DNA replication. We first tested this hypothesis using whole-genome sequence data from Phase I of the 1000 Genomes Project (The 1000 Genome Project Consortium, 2012), which sequenced DNA from non-synchronized, proliferating LCL cultures. For each genome analyzed, we calculated read depth along each chromosome in sliding windows of 10 kb of uniquely alignable sequence, normalized for local GC content at amplicon (400 bp) scale (Handsaker et al., 2011; Supplementary Experimental Procedures). Strikingly, in most LCL-derived genome sequences, fluctuations in read depth along each chromosome matched the LCL replication timing profiles that we had obtained by directly comparing G1 to S phase cells (Figure 2A,B), suggesting that they reflect true differences in underlying DNA copy number arising from replicating cells. The presence of 5-20% of S phase cells within a cell culture was sufficient in order to yield significant signals of DNA replication timing (Supplementary Figure 1E and Supplementary Experimental Procedures).

Figure 2. DNA replication activity is visible in sequence data from the 1000 Genomes Project. See also Figures S1 and S2.

A. Long-range fluctuations in read depth along chromosomes follow the DNA replication profile in DNA derived from cultured cells but not in DNA derived from blood. Shown are smoothed, z-normalized read depth profiles of genomic DNA from four 1000 Genomes samples derived from LCLs (red) and one DNA sample derived from blood (grey), along with the LCL replication timing profile (blue).

B. Read depth is correlated with DNA replication timing to varying extents in different samples (as expected from samples with different proportions of cells in S phase), but is not correlated with GC content. Shown are partial correlations of (unsmoothed) read depth with replication timing (top) and with GC content (bottom), in each case controlling for the other variable (see Figure S1 for complete correlations and sample annotations). Each column corresponds to one of 946 individuals sequenced in the 1000 Genomes Project, sorted by their correlation between read depth and replication timing. Read depth in genomic DNA from blood samples did not correlate with replication timing.

C. DNA replication timing is the major influence on read depth variation among LCL samples, as determined by principal component analysis. Each circle represents one of 882 LCL samples; color indicates the correlation of read depth with replication timing.

D. The coefficients (chromosomal loadings) of the first principal component (in D) correspond to the DNA replication timing profile.

E. A biological signature of the unstructured, “random” replication of inactive X chromosomes from females (Koren and McCarroll, 2014) is apparent in read depth. Inter-individual correlations of read depth along the genome of 161 individuals (see text) are reduced on the X-chromosome when comparisons involve a female sample.

F. Sequencing of DNA from embryonic stem cells (ESCs) identifies ESC-specific replication timing profiles. Shown are read depth profiles of ESCs and LCLs derived from whole-genome sequencing, along with the corresponding S/G1 replication timing profiles . ESC replication timing data is from Ryba et al., 2013.

G. Read depth and replication timing closely track each other within a given cell type (ESC or LCL), and equally distinguish between cell types. Quantitative genome-wide comparison of read depth and replication profiles of ESCs and LCLs (two profiles of each are shown). LCL replication timing is from this study (profile 1) and Ryba et al., 2010 (profile 2). ESC replication timing data is from Ryba et al., 2010. RD: read depth; RT: replication timing.

To further test the hypothesis that active DNA replication causes long-range fluctuations in read depth, we utilized the fact that a subset of the 1000 Genomes Project samples were derived from blood instead of LCLs. Because circulating blood cells have generally exited the cell cycle, these samples do not contain cells in S phase and should not exhibit signatures of DNA replication timing. Consistent with this hypothesis, read depth in blood-derived DNA samples lacked the strong autocorrelative patterns along chromosomes that we observed in LCL-derived DNA, and was uncorrelated with profiles of replication timing (Figure 2A-B, Supplementary Figure S1, and Supplementary Experimental Procedures). In fact, we could distinguish blood-derived from LCL-derived DNA samples with 100% sensitivity and specificity, based solely on the relationship of their read depth profiles to our independent analyses of LCL replication timing (Figure 2A and Supplementary Figure S1).

Importantly, correlations between read depth and replication timing remained strong after controlling for GC content, whereas correlations between read depth and GC content (at scales > 10 kb) were negligible after controlling for replication timing (Figures 2B and Supplementary Figure S1), suggesting that previously observed correlations of read depth with GC content (at 100 kb scales) are due to DNA replication timing. Furthermore, in a principal component analysis (Patterson et al., 2006) of read depth along each of the LCL genomes, the strongest principal component, explaining 40% of the variance, corresponded to our estimate of the S-phase replication content of each sample, and the chromosomal loadings of this component followed the replication timing profile (Figure 2C,D, and Supplementary Experimental Procedures).

The X chromosome provided an additional strong prediction of the hypothesis that read depth at a locus reflects the replication timing of that locus. We recently found that the inactive X chromosome in females undergoes a spatially unstructured, “random” form of replication (Koren and McCarroll, 2014). In light of that finding, the hypothesis that long-range fluctuations in read depth reflect active DNA replication predicts that inter-individual correlations in read depth along each chromosome would be weaker on the X chromosome in comparisons involving female genomes. The 1000 Genomes data abundantly confirmed this prediction (Figure 2E). This effect was not observed in blood samples (Supplementary Figure S2), and supports a biological, rather than technical influence on read depth, as technical influences do not discriminate between sexes or chromosomes.

A final strong test of the hypothesis that read depth reflects ongoing DNA replication was provided by a comparison of different cell types: LCLs and embryonic stem cells (ESCs). The DNA replication timing profiles of LCLs and ESCs differ across 20-30% of the genome (Ryba et al., 2010; Hansen et al., 2010). We sequenced genomic DNA from proliferating ESCs and found that read depth in ESCs matched profiles of replication timing in ESCs and LCLs wherever the profiles were similar between cell types, but matched the ESC profiles wherever ESCs and LCLs had different replication timing profiles (Figure 2F,G). Within a cell type, read depth and replication profiles were virtually indistinguishable, whereas many loci exhibited consistent differences between the two cell types that were visible in both whole-genome sequence and explicit replication profiles (Figure 2F,G).

DNA replication polymorphisms in a population cohort

The results described above established the existence of replication timing variation among humans, and demonstrate that read depth in whole-genome sequence data from proliferating cells reflects active DNA replication. These observations raise the intriguing possibility that one could use data from the 1000 Genomes Project to study variation in replication timing within populations and to learn whether it is under genetic control.

We searched for replication variants in the samples sequenced by the 1000 Genomes Project, focusing on 161 DNA samples that appeared to be derived from cultures containing the largest fraction (5-20%) of S-phase cells at the time they were harvested (based on the correlations of read depth fluctuations to replication timing; Supplementary Experimental Procedures, Supplementary Figure S1E and Supplementary Table S2). We excluded genomic regions with evidence of copy number variation (CNV), visible as large-magnitude, stepwise changes in copy number, and focused on the lower-amplitude, continuous fluctuations in copy number that reflect active DNA replication (Supplementary Experimental Procedures and Supplementary Figure S3).

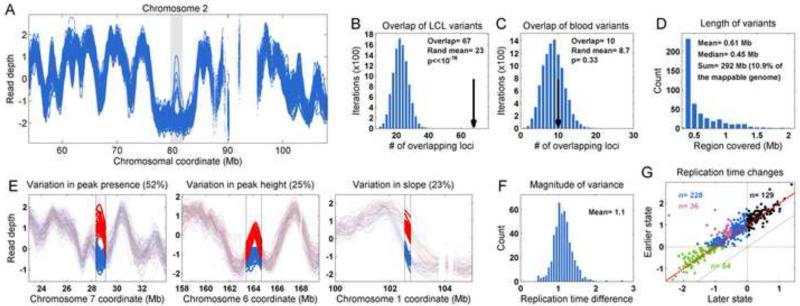

We identified 361 population variants in the read depth-derived DNA replication timing profiles (Supplementary Experimental Procedures). Replication variants identified from the 1000 Genomes data significantly (p < 10−16) overlapped the replication variants we had identified by direct replication profiling of six individuals (Figure 3A,B; as a negative control, loci with the strongest read depth variation across the 64 blood-derived DNA samples exhibited no significant overlap with the replication variants in the six individuals; Figure 3C). To obtain a final set of replication variants, we combined the variants derived from the six individuals with those ascertained from the 1000 Genomes Project individuals and re-evaluated the differences among all individuals specifically in these regions (Supplementary Experimental Procedures). This resulted in a total of 477 variants (Supplementary Table S3) that spanned 610 Kb on average, and cumulatively spanned 292 Mb (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. Variation in DNA replication timing is common in the human population. See also Figure S4.

A. Patterns of read-depth variation among 1000 Genomes individuals indicate the presence of a polymorphic replication origin (grey shaded area ). This is the same replication variant shown in Figure 1C as variable in replication timing in the six individuals.

B. Candidate replication variants identified in the population-based analysis of whole-genome sequence data from the 1000 Genome Project significantly overlap with replication variants identified from direct S/G1 replication profiling of six individuals. Black arrow: number of overlapping variants; blue bars: number of overlapping variants in 10,000 permutations of variant locations.

C. Loci with the greatest variation in read depth among blood-derived DNA samples from the 1000 Genomes Project did not significantly overlap with variants identified by replication profiling.

D. Replication variants collectively cover more than 10% of the mappable human genome. Shown is the length distribution of genomic regions affected by replication variants.

E. Forms of replication variation. The frequency of each variant type is indicated.

F. The size distribution of replication variants (average replication timing / read depth differences between the early and late replication state in each variant).

G. Comparison of the replication timing of the early and late states in each individual replication variant locus. Red line: replication difference of 1 std; black dots: shifts between early and earlier replication; blue dots: shifts between early and late replication (purple dots are loci that shift from under -0.5 to over 0.5, i.e. the most significant changes between early and late replication); green dots: shifts between late and later replication.

In over 50% of the variants, individuals differed by the presence or absence of a read depth peak, which we interpret as a gain or loss of the activity of a replication origin or origin cluster (Figure 3E). About 25% of replication variants involved quantitative variation in peak height, or the average utilization or activation timing of a replication origin. The remainder of the variants involved a shift of a replication slope region (transition region; Figure 3E), as could arise if a replication initiation zone was variable in length. Most replication variants were common, with each replication state at each locus shared among multiple individuals (Figure 3A,E and Supplementary Figure S4); this at least partially reflects our ascertainment approach, and does not preclude the possibility of a larger number of rare replication variants that were not detected.

DNA replication timing is influenced by cis-acting genetic variants

The availability of replication timing information for 161 individuals at hundreds of different sites made it possible to search for genetic influences on replication timing. We treated locus-specific replication timing as a quantitative trait (one for each replication variant locus), and analyzed the association of replication timing to sequence variation in the same individuals, using sequence variation data from the 1000 Genomes Project. To reduce the burden of multiple hypothesis testing, we also performed a cis-focused association test restricted to genetic variants near each replication variant region (Degner et al., 2012; Lappalainen et al., 2013; Kilpinen et al., 2013; McVicker et al., 2013; Kasowski et al., 2013; Supplementary Experimental Procedures).

We identified 20 replication variant loci with significant sequence associations in cis (nominal p = 10−5 to 10−13), of which eight were identified in the genome-wide scan and an additional twelve in the cis-localized scan (Figures 4,5, Supplementary Figure S5 and Table S4). As with other genetic traits studied for association with common variants, replication-timing phenotypes tended to associate to haplotypes of many variants in linkage disequilibrium (LD) with one another.

Figure 4. Replication timing quantitative trait loci (rtQTLs).

Genetic variants underlie differences in DNA replication timing among individuals. Shown are three examples of replication variants with significant genetic association (additional examples are in Figure 5 and Figure S5).

A. Variation in replication timing of a specific locus is strongly associated with SNPs that map within the locus itself. Shown are Manhattan plots of genome-wide association of genetic variants with replication timing. Red arrow: genomic location of the tested replication variant region. Black dashed line: genome-wide association significance threshold.

B. Detailed genetic associations in replication variant regions (dots; right axis) along with replication (read depth) profiles (left axis) for individuals with each of the three genotypes of the most strongly associated SNPs. Yellow dots denote rtQTL SNPs that were also eQTLs for a nearby gene.

C. Left panels: distribution of read depth for individuals with each of the genotypes of the SNP most strongly associated with each variant. Right panels: droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) analysis confirms that the allele associated with early replication is also over-represented in genomic DNA from heterozygous individuals, consistent with a cis-acting, allele-specific effect on DNA replication timing.

Figure 5. rtQTLs involve variable use of replication origins and exert long-range effects on replication timing. See also Figure S5.

rtQTLs involve associations with sets of markers in the immediate vicinity of replication origins, and affect the replication timing of megabases of surrounding DNA. Plots are as in Figure 4B. The lower graphs in each panel (bold black line) show that replication timing differences gradually decrease with distance from rtQTL loci. Supplementary Figure S5 shows a zoomed-in version of all association results, as well as an additional two rtQTL loci that were not clearly associated with replication origins .

To critically evaluate these associations, we used data from an additional 334 samples from the 1000 Genomes Project; these samples, which had weaker signatures of replication timing (r = 0.2 - 0.4), had not been included in the initial scan. At each of the 20 loci, we tested whether the “index SNP” (the most strongly associating SNP) from the initial analysis also associated with measurements of replication timing in the other samples. Despite the lower power to detect replication timing associations using these samples, sixteen of the associated loci were replicated with p values of between 10−24 and 0.05, all with the same direction of allelic influence as the original samples. The index SNPs at the remaining four loci were not significant in the replication analysis, reflecting an unknown combination of partial power and some false positives in the initial scan (Supplementary Figure S5).

We also searched for trans-associations (associations to variants outside the replication variant region); however, our sample set is composed of individuals from many different populations, making such an analysis vulnerable to artifacts of population structure. Indeed, the 17 identified putative trans-associations did not map to genes related to DNA replication or related pathways and were not considered further (see Supplementary Experimental Procedures).

We refer to genetic variants that associate with replication timing as replication timing quantitative trait loci (rtQTLs). The 20 rtQTL haplotypes consisted entirely of SNPs and short indels (rather than large structural polymorphisms), indicating that fine-scale sequence variation can be sufficient to affect DNA replication timing on megabase scales (we note that CNVs and other forms of variation could influence replication timing at loci not identified here). The implicated genetic variants were almost always located in the immediate vicinity of a replication timing peak (median distance = 52 Kb, p = 7.2×10−5; Figures 4B and 5), suggesting that rtQTLs typically affect DNA replication by affecting replication origins. The implicated rtQTL haplotypes were generally small (2-160 Kb, median = 20 Kb), yet the regions whose replication timing associated with these haplotypes were 4-600 times larger, encompassing 0.39-1.86 Mb (median = 0.66 Mb) of surrounding sequence (Figures 4 and 5).

Individuals heterozygous for rtQTL SNPs had replication timing phenotypes intermediate between those of homozygous individuals (Figure 4B-C). This could be due to having one earlier- and one later-replicating version of the locus on their two chromosomal copies, if rtQTLs are due to allele-specific, cis-acting influences of DNA sequence on replication timing, as opposed to trans-acting or non-genetic effects. Individuals heterozygous for rtQTL SNPs should therefore exhibit allelic asynchrony of replication at the rtQTL loci, and have more copies of the early-replicating allele than the late-replicating allele in their genomic DNA. To test this prediction, we used droplet digital PCR (Hindson et al., 2011) to measure the allelic content of the genomic DNA at four rtQTL loci each in LCL-derived DNA from 18-35 heterozygous individuals. At all four loci, the allele associated with earlier replication timing (at a population level) also exhibited greater abundance (p = 0.005 – 5.3×10−6) within genomic DNA from heterozygous individuals (Figure 4C), while control SNPs that were not in LD with the rtQTL SNPs were not significantly skewed (Supplementary Experimental Procedures). These results confirm our sequencing- and population-based inference and are consistent with a model in which genetic variation affects replication timing in an allele-specific, cis-acting manner.

DNA replication is associated with a long-range effect on gene expression levels

Replication origin activity is associated with open chromatin structure, and DNA replication timing is generally correlated with the levels of gene expression across a genome (Rhind and Gilbert, 2013). We therefore hypothesized that rtQTLs may operate by influencing chromatin states. We compared the locations of rtQTLs to the locations of enhancers, defined as DNA segments of ~500 bp containing combinations of histone modifications that promote expression of nearby genes (Ernst et al., 2011). We found a significant enrichment of rtQTLs within enhancer regions that were specifically active in LCLs (out of nine cell types examined; Supplementary Table S6); 11 of 20 rtQTL loci contained sequence variants within LCL enhancers, even though the latter cover less than 1% of the genome (enrichment χ2 p < 10−16). This relationship suggested that rtQTLs may affect DNA replication by promoting an open chromatin structure, prompting us to analyze more closely their relationship to gene expression.

To explore in more detail the relationship between DNA replication timing and gene expression levels at regions implicated by rtQTLs, we utilized a recent RNA-seq analysis of gene expression in 462 LCL samples from the 1000 Genomes Project (Lappalainen et al., 2013). We first compared the locations of expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) identified in the RNA-seq study with the locations of rtQTLs. At 9 of the 20 rtQTL loci, the implicated SNPs overlapped cis- eQTLs (Figures 4B and 5, and Supplementary Figure S5), even though eQTLs comprised <0.02% of the genome (enrichment χ2 p < 10−16). Moreover, in eight of those nine cases, the rtQTL alleles that associated with early replication were also the alleles associated with elevated expression levels. This observation provides independent confirmation that our rtQTL findings, which were made entirely from genomic DNA (without any analysis of RNA), relate to functional aspects of genome biology. Furthermore, the tendency of expressed genes to be in early-replicating regions of the genome may reflect shared genetic influences, e.g., influences of genetic variation on open chromatin.

An important distinction between eQTLs and rtQTLs is that most eQTLs directly affect the expression of genes in their immediate vicinity (median distance of 20 Kb between SNPs and gene promoter, for the eQTLs overlapping rtQTLs), whereas the rtQTLs associate with the replication timing of megabases of surrounding DNA (median = 660 Kb). The order-of-magnitude difference in the scale of the effects of rtQTLs and eQTLs provided a unique opportunity to address a longstanding question – can DNA replication timing itself influence gene expression levels in proliferating cells? We addressed this question by testing for elevated expression of genes across the entire, megabase-scale regions affected by rtQTLs. Focusing on 53 individuals for which both gene expression and replication timing data were available, we compared inter-individual variations in replication timing to inter-individual variation in gene expression levels in each of the 20 regions implicated by rtQTLs. At each locus, we considered both an aggregate measure of gene expression (across all genes in the replication-affected region) (Supplementary Figure S6) as well as the relationship to each individual gene (Figure 6). Individuals with earlier replication of a locus strongly tended to also have higher expression levels of genes throughout the locus (Supplementary Figure S6), including modest but consistent relationships to expression variation for almost every individual gene (Figure 6). Strikingly, early replication timing consistently correlated with greater gene expression up to distances of ~500 Kb, an order of magnitude larger than the typical range of eQTLs, or of the nine eQTLs that overlapped with rtQTLs (Figure 6). These results suggest that replication timing can regulate gene expression levels in proliferating cells, and that such effects can be exerted over long genomic distances.

Figure 6. Replication timing associates with gene expression levels. See also Figures S6 and S7.

Individuals whose genomes exhibit earlier replication at a replication variant locus also tend to exhibit higher average expression of genes across the entire zone of replication.

A. Correlations between expression levels and replication timing, for the subset of rtQTL loci affecting the replication timing of expressed genes (16 of the 20 rtQTL loci), across 53 individuals, for each gene within the rtQTL-implicated replication variant regions. Dashed black lines: replication variant region borders; red lines: rtQTL association region.

B. The correlation between replication timing and gene expression decreases as a function of gene distance from the rtQTL SNPs.

C. The distribution of correlations between replication timing and gene expression across individuals, for all replication variants that contained expressed genes.

The relationships of early replication to elevated levels of gene expression across individuals also extended to the remainder of the 477 replication timing variants (for which rtQTLs have not currently been identified) (Figure 6C), and replication variant sites were significantly enriched for eQTLs compared to random genomic sites (Supplementary Figure 7).

Finally, we note that despite the links between DNA replication timing and gene expression, three rtQTL loci were almost completely devoid of transcription (Figure 6A). Thus, while replication timing and gene expression may share some regulatory influences (such as open chromatin), each process appears to be independently controlled. In particular, transcription is not required for the establishment of rtQTLs.

An rtQTL links early origin activity to JAK2 mutations that lead to myeloproliferative neoplasms

An intriguing implication of rtQTLs is that inherited alleles could modify mutation rates in their genomic vicinity by affecting the replication timing of nearby DNA. A medically important example of polymorphism-associated mutation rates involves the JAK2 (Janus Kinase 2) locus. JAK2 is strongly expressed in blood cells including hematopoietic stem cells, B lymphocytes and LCLs; because JAK2 transduces growth signals, activating JAK2 mutations (e.g. JAK2V617F) that arise in individual cells cause clonal expansions that result in myeloproliferative neoplasms and can transform into hematological malignancies. These activating JAK2 mutations have been shown to arise more frequently in carriers of a “predisposing haplotype” defined by specific alleles at genetic markers across JAK2 (Olcaydu et al., 2009; Jones et al., 2009; Kilpivaara et al., 2009), and to arise in cis with respect to this haplotype (i.e. on the same chromosomal copy; Olcaydu et al., 2009; Jones et al., 2009; Kilpivaara et al., 2009). The mechanism underlying this relationship is unknown. JAK2 has also been identified as an early replicating fragile site (ERFS) in B lymphocytes (Barlow et al., 2013). ERFSs are genomic loci at which early origin activation can lead to double strand breaks, particularly in the presence of nearby transcription, with consequently elevated mutation rates at distances of up to hundreds of kilobases from the break site (Barlow et al., 2013; Pederson and De, 2013; Drier et al., 2013; Jones et al., 2013; Deem et al., 2011; Wang and Vasquez, 2004).

We evaluated the possibility that replication timing variation could explain the mutability of the JAK2 haplotype, and specifically that the mutation-predisposing haplotype is an rtQTL. We found a replication variant near JAK2, which was just below the significance threshold of our genome-wide screen for replication variants. Replication at JAK2 involved an unusually early replicating origin (i.e. a high peak on the replication profile; Figure 7), consistent with the identification of the same locus as an ERFS (Barlow et al., 2013). We also found that the direction of replication fork progression is opposite the direction of JAK2 transcription (Figure 7), consistent with a model in which chromosome fragility is enhanced by head-on collisions between the replication and transcription machinery. Most importantly, the inherited JAK2 alleles that predispose to JAK2 mutations all associated strongly (p < 4.5 × 10−4) with earlier or more efficient activation of the origin (i.e. a higher replication peak; Figure 7), and were among the peak SNPs for the rtQTL (Figure 7). Taken together, these data are consistent with a model in which chromosome fragility, enhanced by interference between the replication and transcription machinery, underlies the mutations in JAK2 , and does so more frequently in individuals in whom replication activity from the origin is earlier and/or more efficient.

Figure 7. An rtQTL at the JAK2 locus.

A common allele at a SNP downstream of JAK2, previously associated with increased JAK2 mutation rates, is also associated with very early replication (higher peak) of an adjacent origin in an early replicating fragile site (ERFS) region. JAK2 (dashed vertical lines) is transcribed towards the inferred replication origin (the peak). The heights of the black points show the level of association of SNPs to the replication timing of this locus, on the scale shown on the right. Diagram on the bottom depicts the location and transcriptional orientation of JAK2 compared to the direction of replication fork progression from the nearby origin.

Discussion

How eukaryotic genomes specify the timing of replication origin activation is a longstanding mystery. We show here that locus-specific replication timing varies among humans and is influenced by inherited genetic polymorphism. Replication variants involve alterations in the replication timing of large (200 kb - 2 Mb) chromosomal regions. Most if not all of these variants relate to differences in replication origin (or origin cluster) activity, as inferred from replication timing peak structures. We discovered SNP haplotypes that associate with DNA replication timing, which we call replication timing QTLs (rtQTLs). The genetic variation implicated at rtQTLs tends to be at or very close to the inferred replication origin. Given the overlap between rtQTLs and enhancers in the same cell type, rtQTLs may affect DNA replication by promoting an open chromatin structure that is permissible for origin firing. Alternatively, some rtQTLs may alter the DNA sequences bound by factors that promote origin firing. Understanding the mode of action of rtQTLs will illuminate the complex process of replication timing control.

To study DNA replication timing, we made use of genome sequence data from the 1000 Genomes Project, which was designed primarily as a study of genome sequence variation (and not a functional study of DNA replication). As a result, the discovery power in the current study was limited by the low read depth (3-5x), the relatively small number of individuals analyzed, and the lack of any deliberate enrichment for S-phase cells. Consequently, we have likely found only the rtQTLs with the strongest effect on replication timing and that arise from common alleles. Replication timing is likely shaped by multiple genetic and epigenetic factors, and will require more powerful analyses to identify the full sets of underlying factors at each locus. We expect that subsequent work will identify far more rtQTLs, in LCLs and other cell types. Identification of a larger number of rtQTLs will facilitate the analysis of their common features and their molecular mode of action, and pave the way for an understanding of the regulation of replication origin activity. Furthermore, identification of the causal variants that control replication origin activity will make it possible to manipulate replication timing experimentally, providing new ways of investigating the causes and consequences of DNA replication timing.

An intriguing implication of our results relates to the relationship between DNA replication timing and the generation of mutations. DNA replication timing is associated with mutation rate variation across the genome in two important ways. First, late-replicating DNA is generally more prone to mutation than early-replicating DNA. Late replication is also associated with increased levels of DNA breakage at common fragile sites (CFSs; Letessier et al., 2011); notably in this regard, the replication variants we identified overlap 19 CFSs, including FRA3B, the most common fragile site in lymphocytes. Second, elevated mutation rates also occur in regions with high transcriptional activity in the vicinity of early replicating origins due to collisions between the replication and transcription machineries, which lead to chromosome fragility, double strand breaks, ssDNA formation and error-prone DNA synthesis (Barlow et al., 2013; Pederson and De, 2013; Drier et al., 2013; Jones et al. 2013; Deem et al., 2011; Wang and Vasquez, 2004). Genetic variants that affect DNA replication timing therefore have the potential to affect mutation rates in their vicinity. Such an effect would have important implications for evolution and for disease. First, rtQTL alleles conferring regional late replication or early origin activity in the vicinity of active genes could function as cis-acting mutators that co-segregate, via genetic linkage, with the mutations they induce, providing a mechanism for evolutionary optimization of local mutation rates in sexual species (Martincorena and Luscombe, 2012). Second, rtQTLs may serve as common, inherited genetic polymorphisms that affect the probability of somatic mutation at specific loci. Diseases with high heritability are often assumed to be distinct from diseases of somatic mutation. Our results suggest, however, that inherited polymorphism can consign a genomic region to late replication or create early replicating fragile sites in a particular tissue, thereby increasing the likelihood that it will acquire somatic mutations in that tissue. At the JAK2 kinase locus, for example, the same SNP haplotype is associated with both early origin activation and elevated mutation rates that can lead to myeloproliferative neoplasms. Altered replication timing in a relevant cell population could thus be a means by which inherited variation influences somatic mutation rates and consequentially, disease and cancer susceptibility.

The presence of a substantial subpopulation of S-phase cells in expanding cell cultures appears to endow whole-genome sequences derived from such samples with information about ongoing DNA replication activity. The influence of DNA replication is directly related to the proportion of cells that are in S phase, which for cultured cells depends on their growth phase: exponentially growing cultures will contain the largest fraction of replicating cells, while quiescent cultures will tend to contain mostly cells in G1 phase. Replication timing could influence any measurement of DNA content (array- or sequencing-based) that has been made from proliferating cells, e.g., studies of copy number variation and chromatin states. Copy number detection in single cells, for example during preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD), is also more prone to false CNV detection when a cell is in S phase (Dimitriadou et al., 2014). Replication timing will need to be carefully considered as a potential confounding variable in genomic studies. On the other hand, the sequencing of genomic DNA derived from proliferating cells could become a routine way of studying replication dynamics. This approach will enable the study of DNA replication dynamics in a wide range of experimental conditions, cell types, and species, in a technically straightforward way.

Experimental Procedures

Replication variants were discovered in replication timing data of six individuals4 by pairwise comparisons of consecutive 200Kb windows along the genome, selection of windows with a p value <10−10 (t-test), and consolidation of significant windows within 200Kb of other significant windows into discrete variant loci. Read depth measurements in 10Kb windows from samples from the 1000 Genomes Project (The 1000 Genome Project Consortium, 2012; Handsaker et al., 2011) were compared to replication timing profiles; for the 161 samples with a genome-wide correlation of >0.4 between read depth and replication timing, replication variants were identified as above and the two lists of replication variants were consolidated into a total of 477 replication variant loci. At each locus, quantitative measurements of replication timing were derived from the 1000 Genomes data across the 161 individuals, and were correlated with the genotypes (from the 1000 Genomes Project) of these same individuals. One thousand permutations of sample genotypes were performed in order to obtain an empirical significance threshold for associations with genetic variants. We performed a genome wide association test with over 7.5 million genetic variants with an allele frequency >0.05 in the tested individuals; as well as a cis-focused association test with genetic variants only within each replication variant locus. rtQTLs were validated using droplet digital PCR (Hindson et al., 2011) with allele-specific probes. Expression data and eQTLs were from Lappalainen et al., 2013. See Extended Experimental Procedures for further details.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

- Replication timing, a driver of locus-specific mutation rates, varies among humans

- Whole genome sequence data can be used to study DNA replication activity

- Replication timing associates with common polymorphisms near replication origins

- Replication timing QTLs have megabase-scale effects on replication and transcription

Acknowledgments

We thank Vanessa Van Doren for technical assistance, and David Altshuler, Chris Patil, Giulio Genovese, Sam Rose and Itamar Simon for discussions and comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute (R01 HG 006855, to SAM), the Integra-Life Seventh Framework Programme (grant # 315997, to RK), the Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and the Harvard Stem Cell Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aird D, Ross MG, Chen WS, Danielsson M, Fennell T, Russ C, Jaffe DB, Nusbaum C, Gnirke A. Analyzing and minimizing PCR amplification bias in Illumina sequencing libraries. Genome Biology. 2011;12:R18. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-2-r18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow JH, Faryabi RB, Callen E, Wong N, Malhowski A, Chen HT, Gutierrez-Cruz G, Sun H-W, McKinnon P, Wright G, Casellas R, Robbiani DF, Staudt L, Fernandez-Capetillo O, Nussenzweig A. Identification of Early Replicating Fragile Sites that Contribute to Genome Instability. Cell. 2013;152:620–632. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deem A, Keszthelyi A, Blackgrove T, Vayl A, Coffey B, Mathur R, Chabes A, Malkova A. Break-Induced Replication Is Highly Inaccurate. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1000594 EP. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degner JF, Pai AA, Pique-Regi R, Veyrieras J-B, Gaffney DJ, Pickrell JK, De Leon S, Michelini K, Lewellen N, Crawford GE, Stephens M, Gilad Y, Pritchard JK. DNaseI sensitivity QTLs are a major determinant of human expression variation. Nature. 2012;482:390–394. doi: 10.1038/nature10808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitriadou E, Van der Aa N, Cheng J, Voet T, Vermeesch JR. Single cell segmental aneuploidy detection is compromised by S phase. Mol Cytogenet. 2014;7:46. doi: 10.1186/1755-8166-7-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diskin SJ, Li M, Hou C, Yang S, Glessner J, Hakonarson H, Bucan M, Maris JM, Wang K. Adjustment of genomic waves in signal intensities from whole-genome SNP genotyping platforms. Nucleic Acids Research. 2008;36:e126. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drier Y, Lawrence MS, Carter SL, Stewart C, Gabriel SB, Lander ES, Meyerson M, Beroukhim R, Getz G. Somatic rearrangements across cancer reveal classes of samples with distinct patterns of DNA breakage and rearrangement-induced hypermutability. Genome Research. 2013;23:228–235. doi: 10.1101/gr.141382.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst J, Kheradpour P, Mikkelsen TS, Shoresh N, Ward LD, Epstein CB, Zhang X, Wang L, Issner R, Coyne M, Ku M, Durham T, Kellis M, Bernstein BE. Mapping and analysis of chromatin state dynamics in nine human cell types. Nature. 2011;473:43–49. doi: 10.1038/nature09906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handsaker RE, Korn JM, Nemesh J, McCarroll SA. Discovery and genotyping of genome structural polymorphism by sequencing on a population scale. Nature Genetics. 2011;43:269–276. doi: 10.1038/ng.768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen RS, Thomas S, Sandstrom R, Canfield TK, Thurman RE, Weaver M, Dorschner MO, Gartler SM, Stamatoyannopoulos JA. Sequencing newly replicated DNA reveals widespread plasticity in human replication timing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:139–144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912402107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins M, Retkute R, Muller CA, Saner N, Tanaka TU, de Moura APS, Nieduszynski CA. High-Resolution Replication Profiles Define the Stochastic Nature of Genome Replication Initiation and Termination. Cell Reports. 2013;5:1132–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindson BJ, Ness KD, Masquelier DA, Belgrader P, Heredia NJ, Makarewicz AJ, Bright IJ, et al. High-throughput droplet digital PCR system for absolute quantitation of DNA copy number. Anal Chem. 2011;83:8604–8610. doi: 10.1021/ac202028g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiratani I, Ryba T, Itoh M, Yokochi T, Schwaiger M, Chang C-W, Lyou Y, Townes TM, Schubeler D, Gilbert DM. Global Reorganization of Replication Domains During Embryonic Stem Cell Differentiation. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e245 EP. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AV, Chase A, Silver RT, Oscier D, Zoi K, Wang YL, Cario H, Pahl HL, Collins A, Reiter A, Grand F, Cross NCP. JAK2 haplotype is a major risk factor for the development of myeloproliferative neoplasms. Nature Genetics. 2009;41:446–449. doi: 10.1038/ng.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RM, Mortusewicz O, Afzal I, Lorvellec M, Garcia P, Helleday T, Petermann E. Increased replication initiation and conflicts with transcription underlie Cyclin E-induced replication stress. Oncogene. 2013;32:3744–3753. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasowski M, Kyriazopoulou-Panagiotopoulou S, Grubert F, Zaugg JB, Kundaje A, Liu Y, Boyle AP, Zhang QC, Zakharia F, Spacek DV, Li J, Xie D, Olarerin-George A, Steinmetz LM, Hogenesch JB, Kellis M, Batzoglou S, Snyder M. Extensive Variation in Chromatin States Across Humans. Science. 2013;342:750–752. doi: 10.1126/science.1242510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpinen H, Waszak SM, Gschwind AR, Raghav SK, Witwicki RM, Orioli A, Migliavacca E, et al. Coordinated Effects of Sequence Variation on DNA Binding, Chromatin Structure, and Transcription. Science. 2013;342:744–747. doi: 10.1126/science.1242463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpivaara O, Mukherjee S, Schram AM, Wadleigh M, Mullally A, Ebert BL, Bass A, Marubayashi S, Heguy A, Garcia-Manero G, Kantarjian H, Offit K, Stone RM, Gilliland DG, Klein RJ, Levine RL. A germline JAK2 SNP is associated with predisposition to the development of JAK2V617F-positive myeloproliferative neoplasms. Nature Genetics. 2009;41:455–459. doi: 10.1038/ng.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren A, Polak P, Nemesh J, Michaelson JJ, Sebat J, Sunyaev SR, McCarroll SA. Differential Relationship of DNA Replication Timing to Different Forms of Human Mutation and Variation. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2012;91:1033–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren A, McCarroll SA. Random replication of the inactive X chromosome. Genome Research. 2014;24(1):64–69. doi: 10.1101/gr.161828.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lappalainen T, Sammeth M, Friedlander MR, t Hoen PAC, Monlong J, Rivas MA, Gonzalez-Porta M, et al. Transcriptome and genome sequencing uncovers functional variation in humans. Nature. 2013;501:506–511. doi: 10.1038/nature12531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Polak P, Kryukov GV, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko A, Carter SL, et al. Mutational heterogeneity in cancer and the search for new cancer-associated genes. Nature. 2013;499:214–218. doi: 10.1038/nature12213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepretre F, Villenet C, Quief S, Nibourel O, Jacquemin C, Troussard X, Jardin F, Gibson F, Kerckaert JP, Roumier C, Figeac M. Waved aCGH: to smooth or not to smooth. Nucleic Acids Research. 2010;38:e94. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letessier A, Millot GA, Koundrioukoff S, Lachages A-M, Vogt N, Hansen RS, Malfoy B, Brison O, Debatisse M. Cell-type-specific replication initiation programs set fragility of the FRA3B fragile site. Nature. 2011;470:120–123. doi: 10.1038/nature09745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manukjan G, Tauscher M, Steinemann D. Replication timing influences DNA copy number determination by array-CGH. Biotechniques. 2013;55:231–232. doi: 10.2144/000114097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marioni JC, Thorne NP, Valsesia A, Fitzgerald T, Redon R, Fiegler H, Andrews TD, Stranger BE, Lynch AG, Dermitzakis ET, Carter NP, Tavare S, Hurles ME. Breaking the waves: improved detection of copy number variation from microarray-based comparative genomic hybridization. Genome Biology. 2007;8:R228. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-10-r228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martincorena I, Luscombe NM. Non-random mutation: the evolution of targeted hypermutation and hypomutation. Bioessays. 2012;35:123–130. doi: 10.1002/bies.201200150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVicker G, van de Geijn B, Degner JF, Cain CE, Banovich NE, Raj A, Lewellen N, Myrthil M, Gilad Y, Pritchard JK. Identification of Genetic Variants That Affect Histone Modifications in Human Cells. Science. 2013;342:747–749. doi: 10.1126/science.1242429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay R, Lajugie J, Fourel N, Selzer A, Schizas M, Bartholdy B, Mar J, Lin CM, Martin MM, Ryan M, Aladjem MI, Bouhassira EE. Allele-Specific Genome-wide Profiling in Human Primary Erythroblasts Reveal Replication Program Organization. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004319 EP. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olcaydu D, Harutyunyan A, Jager R, Berg T, Gisslinger B, Pabinger I, Gisslinger H, Kralovics R. A common JAK2 haplotype confers susceptibility to myeloproliferative neoplasms. Nature Genetics. 2009;41:450–454. doi: 10.1038/ng.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson N, Price AL, Reich D. Population structure and eigenanalysis. PLoS Genetics. 2006;2:e190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen BS, De S. Loss of heterozygosity preferentially occurs in early replicating regions in cancer genomes. Nucleic Acids Research. 2013;41:7615–7624. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope BD, Tsumagari K, Battaglia D, Ryba T, Hiratani I, Ehrlich M, Gilbert DM. DNA Replication Timing Is Maintained Genome-Wide in Primary Human Myoblasts Independent of D4Z4 Contraction in FSH Muscular Dystrophy. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e27413 EP. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghuraman MK, Winzeler EA, Collingwood D, Hunt S, Wodicka L, Conway A, Lockhart DJ, Davis RW, Brewer BJ, Fangman WL. Replication Dynamics of the Yeast Genome. Science. 2001;294:115–121. doi: 10.1126/science.294.5540.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhind N, Gilbert DM. DNA Replication Timing. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2013;3(7):1–26. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a010132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha EP. The organization of the bacterial genome. Annu Rev Genet. 2008;42:211–233. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryba T, Hiratani I, Lu J, Itoh M, Kulik M, Zhang J, Schulz TC, Robins AJ, Dalton S, Gilbert DM. Evolutionarily conserved replication timing profiles predict long-range chromatin interactions and distinguish closely related cell types. Genome Research. 2010;20:761–770. doi: 10.1101/gr.099655.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryba T, Battaglia D, Chang BH, Shirley JW, Buckley Q, Pope BD, Devidas M, Druker BJ, Gilbert DM. Abnormal developmental control of replication-timing domains in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Genome Res. 2012;22:1833–1844. doi: 10.1101/gr.138511.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp PM, Shields DC, Wolfe KH, Li WH. Chromosomal location and evolutionary rate variation in enterobacterial genes. Science. 1989;246:808–810. doi: 10.1126/science.2683084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slager J, Kjos M, Attaiech L, Veening J-W. Antibiotic-Induced Replication Stress Triggers Bacterial Competence by Increasing Gene Dosage near the Origin. Cell. 2014;157(2):395–406. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Adzhubei I, Thurman RE, Kryukov GV, Mirkin SM, Sunyaev SR. Human mutation rate associated with DNA replication timing. Nature Genetics. 2009;41:393–395. doi: 10.1038/ng.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The 1000 Genome Project Consortium An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012;491:56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Wiel MA, Brosens R, Eilers PHC, Kumps C, Meijer GA, Menten Br, Sistermans E, Speleman F, Timmerman ME, Ylstra B. Smoothing waves in array CGH tumor profiles. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1099–1104. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Heesch S, Mokry M, Boskova V, Junker W, Mehon R, Toonen P, de Bruijn E, Shull JD, Aitman TJ, Cuppen E, Guryev V. Systematic biases in DNA copy number originate from isolation procedures. Genome Biology. 2013;14:R33. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Vasquez KM. Naturally occurring H-DNA-forming sequences are mutagenic in mammalian cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:13448–13453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405116101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.