Abstract

There is a gender-related comorbidity of pain-related and inflammatory bowel diseases with psychiatric diseases. Since the impact of experimental gastrointestinal inflammation on the emotional-affective behaviour is little known, we examined whether experimental gastritis modifies anxiety, stress coping and circulating corticosterone in male and female Him:OF1 mice. Gastritis was induced by adding iodoacetamide (0.1 %) to the drinking water for at least 7 days. Inflammation was assessed by gastric histology and myeloperoxidase activity, circulating corticosterone determined by enzyme immunoassay, anxiety-related behaviour evaluated with the elevated plus maze and stress-induced hyperthermia tests, and depression-like behaviour estimated with the tail suspension test. Iodoacetamide-induced gastritis was associated with gastric mucosal surface damage and an increase in gastric myeloperoxidase activity, this increase being significantly larger in female mice than in male mice. The rectal temperature of male mice treated with iodoacetamide was enhanced, whereas that of female mice was diminished. The circulating levels of corticosterone were reduced by 65 % in female mice treated with iodoacetamide but did not significantly change in male mice. On the behavioural level, iodoacetamide treatment caused a decrease in nocturnal homecage activity, drinking and feeding. While depression-related behaviour remained unaltered following induction of gastritis, behavioural indices of anxiety were significantly enhanced in female but not male mice. There was no correlation between the oestrous cycle and anxiety as well as circulating corticosterone. Radiotracer experiments revealed that iodoacetamide did not readily enter the brain, the blood-brain ratio being 20:1. Collectively, these data show that iodoacetamide treatment causes gastritis in a gender-related manner, its severity being significantly greater in female than in male mice. The induction of gastritis in female mice is associated with a reduction of circulating corticosterone and an enforcement of behavioural indices of anxiety. Gastric inflammation thus has a distinct gender-dependent influence on emotional-affective behaviour and its neuroendocrine control.

Keywords: Iodoacetamide-induced gastritis, anxiety, elevated plus maze test, tail suspension test, myeloperoxidase activity, corticosterone

Population-based surveys show that a history of gastroenteritis as well as neurotic and psychiatric disorders are risk factors for developing pain-related (functional) bowel disorders such as functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome (Spiller, 2003). Accordingly, there is a considerable comorbidity of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and pain-related bowel disturbances with anxiety, depression, somatization and other psychiatric disorders ( Wilhelmsen et al., 1995; Mayer et al., 2001a; Whitehead et al., 2002; Dunlop et al., 2003; Pace et al., 2003; North et al., 2004; Mawdsley and Rampton, 2005). Pain-related bowel disorders are hypothesized to arise from a disturbance in the bidirectional interactions between the gut and the brain. On the one hand, sensitization of afferent pathways from the gut to the brain is thought to contribute to pain and hyperalgesia (Mayer and Collins, 2002; Mulak and Bonaz, 2004). On the other hand, psychic stress has a negative influence on IBD and can trigger or exacerbate symptoms of pain-related bowel disorders (Mayer et al., 2001b; Mittermaier et al., 2004; Murray et al., 2004; Taché and Perdue, 2004; Wong and Chang, 2004). Stress activates the emotional motor system which includes the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) as well as the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system, and these outputs are thought to disturb bowel function (Schwetz et al., 2003; Million and Taché, 2004).

This concept is supported by experimental findings that exposure to stress alters gut function and aggravates experimental colitis (Stam et al., 1997; Million et al., 1999; Taché and Perdue, 2004; Mayer and Collins, 2002; Milde et al., 2005; Reber et al., 2006). In addition, there is emerging evidence that pain-related (functional) bowel disorders and IBD share common mechanisms (Bradesi et al., 2003; Talley, 2006) and that anxiety and depression are factors relevant to both disease entities (Whitehead et al., 2002; Bradesi et al., 2003; Dunlop et al., 2003; Pace et al., 2003; Mittermaier et al., 2004; North et al., 2004; Mawdsley and Rampton, 2005; Talley, 2006). Thus, depression induced by neonatal maternal separation enhances the vulnerability of adult mice to intestinal inflammation (Varghese et al., 2006) and anxiety induced by intra-amygdaloid administration of corticosterone leads to mechanical hypersensitivity of the rat colon (Myers et al., 2005).

Since it has not yet been explored whether experimentally induced gastrointestinal inflammation leads to alterations of affective behaviour, the first and major aim of this study was to examine whether induction of gastritis in mice would increase anxiety- and/or depression-related behaviour. To induce gastritis, iodoacetamide was added to the drinking water at a concentration of 0.1 % for 7 days, which has previously been shown to elicit gastritis (Piqueras et al., 2003; Holzer et al., 2007) and induce gastric hypersensitivity to distension and acid exposure (Ozaki et al., 2002; Lamb et al., 2003). Since pain-related bowel disorders, particularly irritable bowel syndrome, have a considerably higher prevalence in women than in men (Strid et al., 2001; Chang and Heitkemper, 2002; Taché et al., 2005), the second aim was to test both male and female mice in order to reveal any gender difference in the possible impact of gastric inflammation on affective behaviour. The third aim was to assess whether anxiety-like behaviour and circulating corticosterone vary with the oestrous cycle. Anxiety-related behaviour was assessed with the elevated plus-maze test (EPMT; Pellow and File, 1986; Belzung and Griebel, 2001) and stress-induced hyperthermia test (SIHT; Zethof et al., 1994; Olivier et al., 2003) while depression-like behaviour was evaluated with the tail suspension test (TST; Steru et al., 1985; Liu and Gershenfeld, 2001; Cryan et al., 2005). Plasma levels of corticosterone were determined to obtain a measure of HPA axis activity.

The fourth aim was to characterize iodoacetamide-induced gastritis in terms of gastrointestinal mucosal damage, gastric myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity and diurnal homecage activity, drinking and feeding. The fifth and last aim was to address the question whether iodoacetamide may enter the brain to influence emotional behaviour by a central site of action.

METHODS

Experimental animals

This study was carried out with adult male and female mice of the outbred strain Him:OF1 (Division of Laboratory Animal Science and Genetics, Department of Biomedical Research, Medical University of Vienna, Himberg, Austria). At the time of the experiments they were 8-16 weeks old and weighed 25-35 g. The animals were housed in groups of 3-5 per cage under controlled temperature (22 ± 1 °C), relative air humidity (50 ± 15 %) and light conditions (lights on at 6:00 h, lights off at 18:00 h, maximal intensity 150 lux). All experiments were approved by an ethical committee at the Federal Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of the Republic of Austria and conducted according to the Directive of the European Communities Council of 24 November 1986 (86/609/EEC). The experiments were designed in such a way that the number of animals used and their suffering was minimized.

Experimental protocols

Six experimental studies were performed. Study 1 took 2 weeks to complete and was carried out with two groups of male and two groups of female mice, each group comprising 6-7 animals. In week 1 all mice drank normal tap water. In week 2, one group of male and one group of female mice continued to receive normal tap water, whereas the other two groups of animals received tap water containing 0.1 % (w/v) iodoacetamide (Sigma, Vienna, Austria) to induce gastritis. Since iodoacetamide is light-sensitive, the iodoacetamide-containing drinking water was made up fresh every day. At the end of week 2, i.e. at experimental day 15, trunk blood and gastric tissue were collected for the determination of circulating corticosterone and MPO activity in the gastric wall.

Study 2 took 18 days to complete and was performed with two groups of male and two groups of female mice, each group comprising 10-11 animals. As in study 1, all mice drank normal tap water during week 1. In week 2, one group of male and one group of female mice continued to receive normal tap water, whereas the other two animal groups received tap water containing 0.1 % iodoacetamide to induce gastritis. In week 3 a sequence of behavioural tests was carried out while the mice continued to drink either tap water (controls) or tap water containing iodoacetamide. On day 15 the animals were subjected to the EPMT, followed by the SIHT on day 16. On day 18 the TST was performed, 45 min after which trunk blood and gastric tissue were collected for the assay of circulating corticosterone and gastric MPO activity. The stress-induced hyperthermia was tested between 13:00 h and 13:30 h, the EPMT and TST were carried out between 10:00 h and 14:00 h, while blood plasma and gastric tissue were collected between 11:00 h and 14:00 h.

In addition, the fluid intake per cage (populated by 3 or 4 mice) was determined. To this end, the water bottles were refilled every day between 8:30 h and 9:00 h with 150 ml tap water with or without iodoacetamide, and the weight of the water bottles was recorded at the beginning and end of each 24 h period. The drinking volume was expressed as ml/g body weight which was determined on experimental days 1, 8 and 18 and used for calculation of the drinking volume (ml/g body weight) during experimental days 1-7, 8-14 and 15-18, respectively.

Study 3 was carried out to characterize diurnal homecage activity, drinking and feeding as well as body weight during treatment of female mice with iodoacetamide for 7 days. To this end, 6 female mice were placed singly in 6 cages of the LabMaster system (see below). After 1 week of adaptation in the cages during which the mice drank normal tap water, iodoacetamide (0.1 %) was added to the drinking water, and homecage activity, drinking and feeding recorded continuously for a second week. The body weight was determined once daily between 9:00 h and 9:30 h during which the content of the drinking bottles was renewed.

In study 4 we examined whether treatment of mice with iodoacetamide for 1 week causes gastrointestinal mucosal damage at the macroscopic and histological level. Two groups of 5 female mice were used in these experiments. As in study 1, all mice drank normal tap water during week 1. During week 2, one group of mice continued to receive normal tap water, whereas the other group received tap water containing 0.1 % iodoacetamide. The macroscopic and histological appearance of the gastric, jejunal and colonic mucosa was examined on day 15.

Study 5 was performed to assess whether the oestrous cycle affects anxiety and circulating corticosterone. For this purpose, a total of 30 female mice was used and divided into 6 groups of 5 mice, each group being housed in a single cage. After adaptation in the cages for 2 weeks, group 1 was subjected to the EPMT on day 1, and groups 2 - 6 tested on days 2 - 6, respectively. Upon completion of the EPMT a vaginal smear was taken and the oestrous cycle phase determined by light microscopy (Frick et al., 2000). After a pause of more than one week, the relationship between oestrous cycle and circulating corticosterone at baseline and following stress exposure was examined. Groups 1 and 2 were tested on day 12, groups 3 and 4 on day 13, and groups 5 and 6 on day 14. Following sampling of a vaginal smear, blood (0.1 - 0.2 ml) was collected through a small tail incision for determining basal corticosterone levels. Afterwards the mice were placed in a tube of 3 cm diameter and 11 cm length, either end of which had an opening of 0.5 cm diameter to permit exchange of air. After a period of 10 min restraint stress, the animals were returned to their home cage for a period of 35 min. At the end of this period, trunk blood (0.3 – 0.5 ml) was collected for determining the stress-induced rise of circulating corticosterone. All experiments of study 5 took place between 9:00 and 11:00 h.

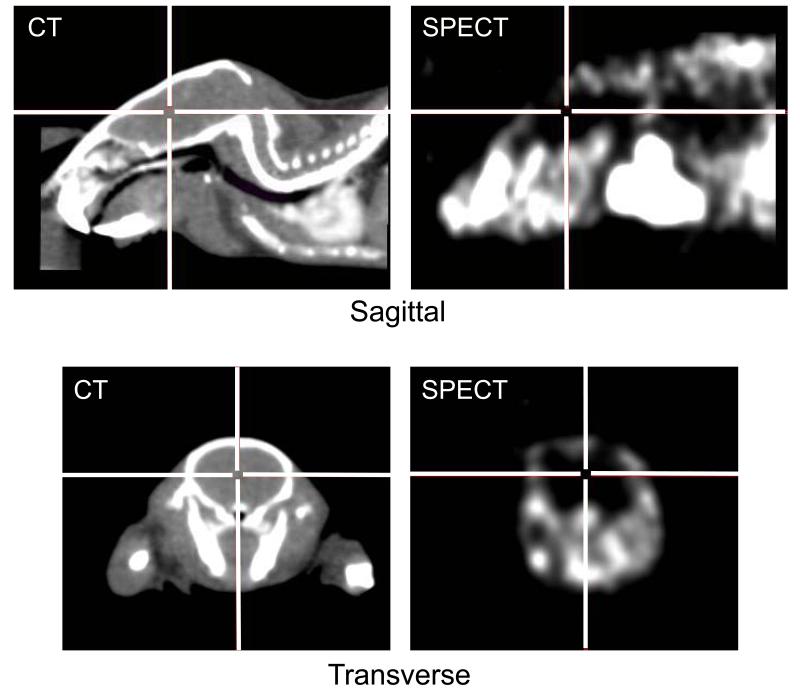

In study 6 the distribution of iodoacetamide labelled with 123I in the body of 2 mice was examined through single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and ex vivo measurement of radioactivity levels in the blood and brain.

Circulating corticosterone

In order to obtain trunk blood, the animals were deeply anaesthetized with pentobarbital (150 mg/kg intraperitoneally) and decapitated. Both trunk blood and tail blood were collected into vials coated with ethylenediamine tetraacetate (EDTA; Greiner, Kremsmünster, Austria) kept on ice. Following centrifugation for 20 min at 4 °C and 1200 × g, blood plasma was collected and stored at −20 °C until assay. The plasma levels of corticosterone were determined with an enzyme immunoassay kit (Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA). According to the manufacturer’s specifications, the sensitivity of the assay is 27 pg/ml, and the intra- and inter-assay coefficient of variation amounts to 7.7 and 9.7 %, respectively.

Myeloperoxidase activity

The enzyme activity of MPO (donor:H2O2 oxidoreductase, EC 1.11.1.7) was determined according to previously described spectrophotometric techniques (Suzuki et al., 1983; Krawisz et al., 1984; Graff et al., 1998). At autopsy, full-thickness pieces of the gastric corpus (120-160 mg) were excised, shock-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70 °C until assay. After homogenisation in potassium phosphate buffer (0.05 M) of pH 7.4 and centrifugation at 40,000 g at 4 °C for 20 min, the pellets were taken up in potassium phosphate buffer (0.05 M) of pH = 6.0 containing 3.72 g/l EDTA (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) and 5 g/l hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (Sigma, Vienna, Austria) which releases MPO from the primary granules of the neutrophils (Krawisz et al., 1984). The enzyme assay was based on the MPO-catalyzed oxidation of tetramethylbenzidine (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) in the presence of H2O2 (Suzuki et al., 1983). The absorbance of the samples was measured at 655 nm.

MPO activity was expressed relative to the MPO activity of human neutrophils. To this end, a sample of human neutrophils (5 million cells in 2 ml of 0.05 M potassium phosphate buffer of pH = 7.4) was extracted in an identical manner as the tissue samples and assayed as described above. A standard curve was constructed by measuring the absorbance of the reaction mixture with various dilutions of the neutrophil extract. Since the MPO activity in the gastric tissue samples was determined as an index of neutrophil infiltration, the MPO activity of the tissue extracts was expressed as human neutrophil equivalents/mg wet tissue.

Macroscopic and histological injury to the mucosa

The stomach, jejunum, ileum, proximal colon and distal colon were pinned flat on a silicon elastomer-coated plate and examined for macroscopically visible damage. Immediately afterwards, specimens of the gastric corpus, jejunum, ileum, proximal colon and distal colon were taken in a standardized manner from the same region in each animal and fixed in a medium containing 2 % paraformaldehyde, 2.5 % glutaraldehyde and 0.1 M cacodylate buffer of pH 7.4 and embedded in Technovit 7100 (Heraeus Kulzer, Wehrheim, Germany). Then 2.5 μm sections were cut, stained with a mixture of methylene blue - azure II and basic fuchsin (Holzer et al., 2007) and examined under a light microscope for the presence of structural damage in the mucosa.

Distribution of 123I-iodoacetamide in the mouse body

Mice were anaesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of tribromoethanol (AvertinR, Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany; 250 mg/kg). Five minutes after injection of 123I-iodoacetamide (approximately 37 MBq in 0.1 ml) into the tail vein, small animal SPECT images were acquired over a period of 30 min with a multipinhole collimator mounted on an Ecam SignatureR single head camera (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). Three-dimensional images were reconstructed with a dedicated multipinhole software (HiSPECTTM, Scivis, Göttingen, Germany). One hour post-injection the animals were decapitated, blood and the brain collected in vials and radioactivity measured with a gamma counter.

Determination of oestrous cycle phase

Vaginal smears were collected with cotton-tipped swabs and transferred to a drop of physiological saline (NaCl, 0.9 %) on glass slides. After staining with a drop of thionine acetate (0.5 %), the vaginal smears were examined under a light microscope. Four phases of the oestrous cycle (oestrus, metoestrus, dioestrus and prooestrus) were differentiated on the basis of the number and morphology of the cells in the vaginal fluid (Frick et al., 2000).

Behavioural tests

Prior to all behavioural tests, the mice were allowed to adapt to the test room (22 ± 1 °C, 50 ± 15 % relative air humidity, lights on at 6:00 h, lights off at 18:00 h, maximal light intensity 100 lux) for at least two days.

Elevated plus-maze test

The animals were placed in the centre of a maze with 4 arms arranged in the shape of a plus (Pellow and File, 1986; Belzung and Griebel, 2001). Specifically, the maze consisted of a central quadrangle (5 × 5 cm), two opposing open arms (30 cm long, 5 cm wide) and two opposing closed arms of the same size but equipped with 15 cm high walls at their sides and the far end. The device was made of opaque grey plastic and elevated 70 cm above the floor. The light intensity at the centre quadrangle was 70 lux, on the open arms 80 lux and in the closed arms 40 lux.

At the beginning of each trial, the animals were placed on the central quadrangle facing an open arm. The movements of the animals during a 5 min test period were tracked by a video camera positioned above the centre of the maze and recorded with the software VideoMot2 (TSE Systems, Bad Homburg, Germany). Post-test this software was used to evaluate the animal tracks and to determine the number of their entries into the open arms, the time spent on the open arms and the total distance travelled in the open and closed arms during the test session. Entry into an arm was defined as the instance when the mouse placed its four paws on that arm.

Stress-induced hyperthermia test

Measurement of the basal temperature in mice with a rectal probe represents a stressor that causes an increase in the temperature by about 1-1.5 °C within 15 min (Zethof et al., 1994; Olivier et al., 2003). In the current experiments, measurement of the basal temperature (T1) was followed by a second measurement of the temperature (T2) 13 min later. This time interval had been found in pilot experiments to best portray the maximal increase in temperature. Being determined with a digital thermometer (BAT-12, Physitemp Instruments, Clifton, New Jersey, USA) equipped with a rectal probe for mice, the stress-induced hyperthermia was calculated as the difference ΔT = T2-T1. The experiments were carried out between 13:00 h and 13:30 h at a light intensity of 100 lux because stress-induced hyperthermia depends both on the time of the day and the light conditions (Peloso et al., 2002).

Tail suspension test

Following exposure to the inescapable stress of being suspended by their tail, mice first struggle to escape but sooner or later attain a posture of immobility (Steru et al., 1985; Liu and Gershenfeld, 2001; Cryan et al., 2005). In the current experiments, mice were suspended by their tail with a 1.9 cm wide strapping tape (OmnitapeR, Paul Hartmann AG, Heidenheim, Germany) to the lever of a force displacement transducer (K30 type 351, Hugo Sachs Elektronik, Freiburg, Germany) which was connected to a bridge amplifier (type 301, Hugo Sachs Elektronik, Freiburg, Germany). The force displacement signals caused by the struggling animal were fed, via an A/D converter (PCIAD16LC; Kolter Electronic, Erftstadt, Germany), into a personal computer and recorded and evaluated with a custom-made software. The sampling frequency was 20 Hz. Each trial took 6 min and was carried out at a light intensity of 20 lux. The total duration of immobility was calculated as the time during which the force of the animals’s movements was below a preset threshold. This threshold was determined to be ± 5 % of the animal’s body weight, and immobility was assumed when at least 8 digits recorded in continuity (equivalent to a time of 0.4 s) were within this threshold range. The validity of the threshold parameters was proved by comparing the software output data with the duration of immobility recorded with a stop watch.

Diurnal homecage activity, drinking and feeding

The circadian pattern of homecage activity, drinking and feeding was recorded with a 6 cage LabMaster system (TSE Systems, Bad Homburg, Germany). Each cage was fitted with a highly sensitive feeding and drinking sensor and a photobeam-based activity monitoring system that recorded every ambulatory movement (Theander-Carrillo et al., 2006). Animal location in the horizontal plane was detected with infrared sensor pairs arranged in strips. The sensors for detection of movement operated efficiently in both light and dark phases. All parameters were measured continuously and simultaneously and analyzed with a custom-made software.

Statistics

Statistical evaluation of the results was performed on SPSS 11.5 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) with two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to identify gender differences, treatment effects and interactions between these factors. The homogeneity of variance was analyzed with the Levene test. Since there is evidence that visceral pain behaviour in rodents is subject to gender differences (Taché et al., 2005), planned comparisons (Kirk, 1995) regarding gender differences within treatments were made with Dunn’s (Bonferroni) comparison test. For post-hoc analysis of group differences the Tukey HSD (honestly significant difference) test was employed.

The direction and strength of the relationship between oestrous cycle phase and anxiety as well as circulating corticosterone were evaluated with Spearman’s rank correlation technique. Differences between two independent groups of data were analyzed with the two sample t test. The data obtained with the LabMaster system were evaluated on Sigmastat (Systat Inc., San Jose, California, USA) with ANOVA for repeated measures followed by the Holm-Sidak test. Probability values of P < 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant. All data are presented as means ± SEM, n referring to the number of mice in each group unless stated otherwise.

RESULTS

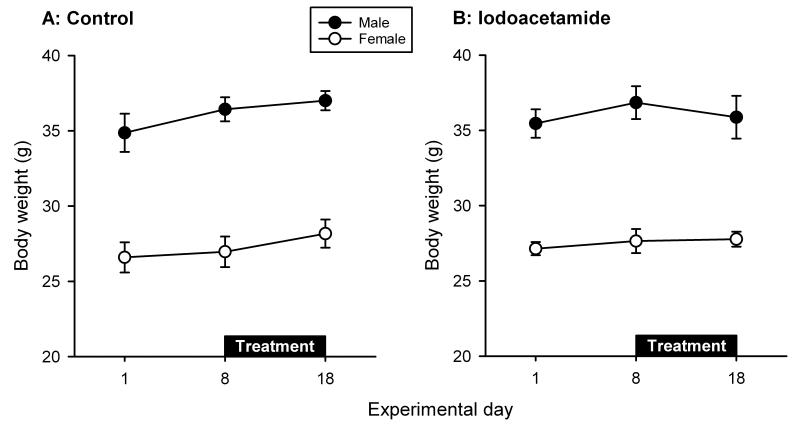

Effect of iodoacetamide treatment on body weight

Mice treated with oral iodoacetamide for 1 week appeared healthy and did not exhibit any overt sign of sickness. The body weight of male and female mice, determined per cage with 3 or 4 mice, differed throughout the experiment (Figure 1A,B). Animals that drank normal tap water during the whole experiment gained in body weight throughout the 18 day observation period independently of their gender (Figure 1A). Specifically, male mice gained 0.58 ± 0.43 g (n = 5) and female mice 1.20 ± 0.15 g (n = 3) during the period of 8 - 18 days. Female mice treated with iodoacetamide from day 8 onwards exhibited a very small increase in body weight between day 8 and 18 (0.12 ± 0.34 g, n = 3), whereas male mice exhibited a minor loss of body weight (-0.97 ± 0.61 g, n = 5) during that period (Figure 1B). Because body weight was determined per cage (n = 3 - 5) with 3 or 4 animals, the number of observations was too small for ANOVA.

Figure 1.

Body weight (g) of male and female mice, assessed on days 1, 8 and 18 during the course of the experiments. Control mice continued to drink normal tap water during the treatment period whereas the experimental group received tap water containing iodoacetamide (0.1 %). The values represent means ± SEM.

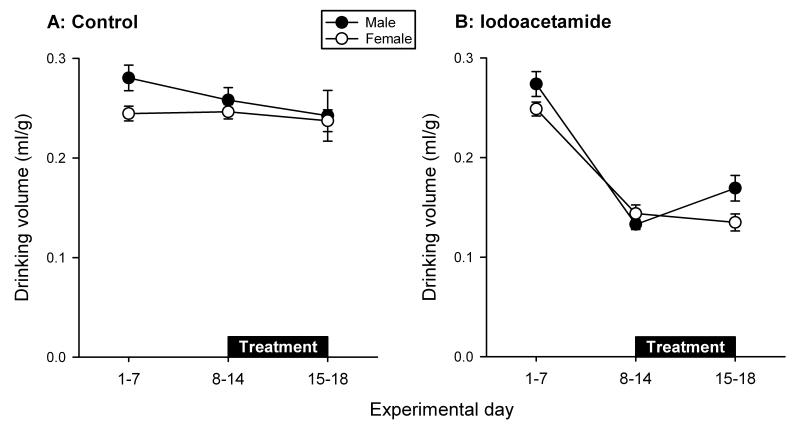

Effect of iodoacetamide treatment on drinking volume

During the first week of observation the daily fluid intake, calculated per cage with 3 or 4 mice and expressed as ml per g body weight, was nominally higher in male than in female control mice, but this gender difference was no longer evident during the second and third week of observation (Figure 2A). The drinking volume fell by some 50 % when male and female mice were forced to drink water containing iodoacetamide from day 8 onwards. This effect of iodoacetamide was sustained throughout the observation period up to day 18 although some tendency towards recovery was observed in male mice (Figure 2B). Because the drinking volume was determined per cage (n = 3 - 5) with 3 or 4 animals, these data could be subjected to descriptive statistics only.

Figure 2.

Daily water intake (ml/g body weight) of male and female mice, averaged for the experimental days 1-7, 8-14 and 15-18 during the course of the experiments. Control mice continued to drink normal tap water during the treatment period whereas the experimental group received tap water containing iodoacetamide (0.1 %). The values represent means ± SEM.

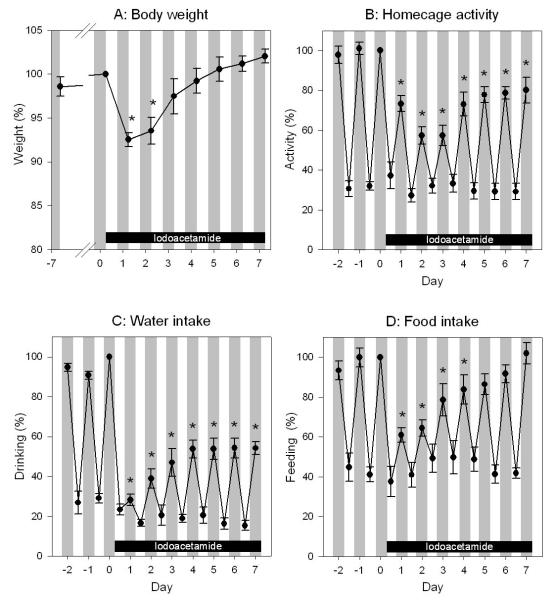

Effect of iodoacetamide on circadian homecage activity, drinking and feeding

Analysis of the circadian activity pattern revealed that iodoacetamide reduced drinking, feeding and homecage activity, these changes reaching statistical significance only during the dark phase (Figure 3B,C,D). While the decrease in nocturnal drinking and locomotor activity was maintained throughout the 7 day period of iodoacetamide treatment, nocturnal feeding returned to normal values from day 5 onwards. There was also an initial decrease in body weight, which reached statistical significance during days 1 and 2, while from day 3 onwards body weight returned to levels measured before iodoacetamide treatment (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Body weight (A) and circadian pattern of homecage activity (B), drinking (C) and feeding (D) before and during a one week period of iodoacetamide treatment (0.1 % added to the drinking water) on days 1 - 7. The white stripes depict the light phase, and the grey stripes the dark phase. The parameters are presented as a percentage of the values recorded on day 0 (A) or during the dark phase of day 0 (B,C,D). The values represent means ± SEM, n = 6. * P < 0.05 versus respective values recorded on day 0 (A) or during the dark phase of day 0 (B,C,D).

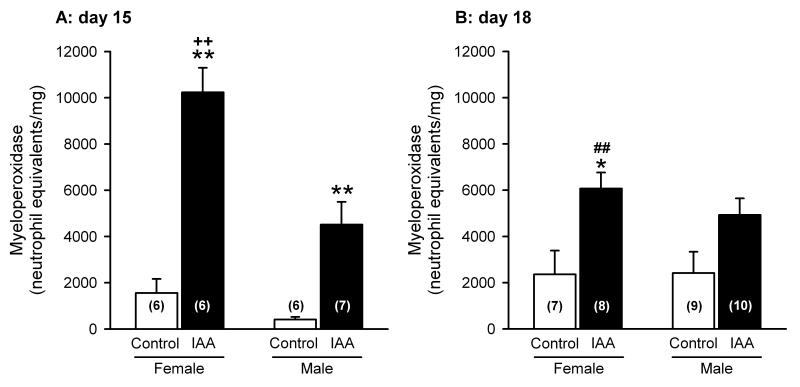

Effect of iodoacetamide treatment on gastric myeloperoxidase activity

MPO activity determined at day 15 was significantly elevated (ANOVA for factor treatment: F(2,21) = 62.25, P < 0.01) in iodoacatamide-treated mice as compared to control animals (Figure 4A). In addition, the iodoacetamide-induced increase in MPO activity was significantly greater in female than in male mice (ANOVA for factor gender: F(1,21) = 17.96, P < 0.01), whereas in mice drinking normal water the gastric MPO levels did not exhibit any significant gender difference (Figure 4A). The interaction between the factors treatment and gender was also significant (F(1,21) = 7.95, P = 0.01). The effect of iodoacetamide to enhance gastric MPO activity was still evident at day 18 when the behavioural tests had been completed (ANOVA for factor treatment: F(2,30) = 13.53, P < 0.01; Figure 4B). Furthermore, at this time point any gender difference had disappeared as the gastric MPO activity in iodoacetamide-treated female mice had become significantly lower (t(12) = 3.42) than at day 15 (Figure 4A,B). In contrast, gastric MPO activity in control animals was nominally higher at day 18 than at day 15, although this change was statistically not significant (Figure 4A,B).

Figure 4.

Myeloperoxidase activity in the gastric wall of control and iodoacetamide-treated mice of either gender, determined on day 15 and 18 in the course of the experiments. The animals drank either normal tap water (control) or tap water containing iodoacetamide (0.1 %) from experimental day 8 onwards. Myeloperoxidase activity was expressed as human neutrophil equivalents/mg wet tissue. The values represent means ± SEM, n as indicated in brackets. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 versus control mice of the same gender and analysis day; ++ P < 0.01 versus male iodoacetamide-treated mice analyzed on day 15; ## P < 0.01 versus female iodoacetamide-treated mice analyzed on day 15.

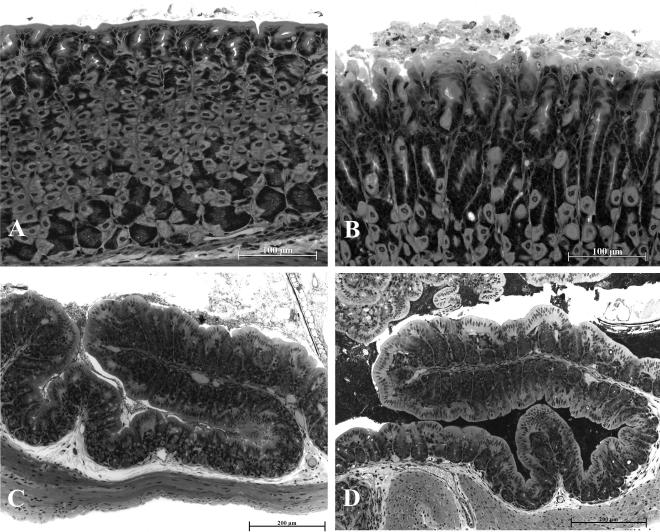

Effect of iodoacetamide on the macroscopic and histological appearance of the gastric and colonic mucosa

On macroscopic inspection, the gastric, jejunal and colonic mucosa did not differ between mice that had drunk normal tap water or water containing iodoacetamide for one week and appeared macroscopically normal (data not shown). Histological analysis revealed that all 5 stomachs taken from mice treated with iodoacetamide exhibited structural injury on the luminal side of the mucosa, whereas only 2 of 5 control stomachs displayed appreciable irregularities on the surface of the mucosa (Figure 5A,B). Characteristic of the gastric damage seen in iodoacetamide-treated mice was that the luminal side of the mucosa was covered by loose mucosal cells that were shed from the epithelium (Figure 5B). Qualitative scoring showed that this structural damage was in most cases confined to the luminal surface of the mucosa and only rarely occupied the outer 10 % of the mucosal depth. The histological appearance of the mucosa of the jejunum, ileum (data not shown), proximal colon (Figure 5C,D) and distal colon (data not shown) was essentially normal and did not differ between control and iodoacetamide-treated mice.

Figure 5.

Histological appearance of the gastric corpus mucosa taken from a control mouse (A) and a mouse treated with iodoacetamide (B; 0.1 % iodoacetamide in the drinking water for 1 week) and of the proximal colon taken from a control mouse (C) and a mouse treated with iodoacetamide (D). The photographs show that iodoacetamide caused superficial damage to the gastric mucosa (B) but did not injure the mucosa of the proximal colon (D), relative to the histological appearance of a control gastric (A) and colonic (C) mucosa.

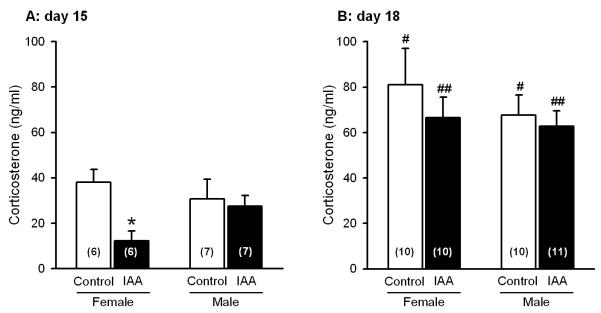

Effect of iodoacetamide treatment on circulating corticosterone

Treatment with iodoacetamide caused a significant reduction of the circulating corticosterone levels as measured on day 15 (ANOVA for factor treatment: F(1,22) = 5.38, P < 0.05). Planned comparison revealed that the plasma corticosterone concentration fell only in female (t(10) = 3.64), but not male iodoacetamide-treated mice, whereas the corticosterone levels in control animals exhibited no gender difference (Figure 6A). The plasma corticosterone levels were also measured on day 18, 45 min after exposure to the TST to evaluate the stress-coping behaviour of the animals. Analysis with the two sample t test showed that, at this time point, the circulating corticosterone levels in both male (control: t(15) = −2.87, iodoacetamide-treated: t(16) = −3.80) and female (control: t(11.03) = −2.53, iodoacetamide-treated: t(12.35) = −5.36) mice were higher than at day 15 but did not display any treatment or gender difference (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Corticosterone levels in blood plasma (ng/ml) of control and iodoacetamide-treated mice of either gender, determined on day 15 and 18 in the course of the experiments. The animals drank either normal tap water (control) or tap water containing iodoacetamide (0.1 %) from experimental day 8 onwards. On day 18, circulating corticosterone was assayed 45 min after the mice had been subjected to the TST. The values represent means ± SEM, n as indicated in brackets. * P < 0.05 versus control mice of the same gender and analysis day; # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01 versus mice of the same gender and treatment analyzed on day 15.

Distribution of iodoacetamide in the brain

Five minutes after intravenous injection of 123I-iodoacetamide to two anaesthetized mice, small animal SPECT images were acquired over a period of 30 min. As shown in Figure 7, no focal or generalized uptake of 123I-iodoacetamide into the brain could be visualized by SPECT (Figure 7). The radioactivity measured in the brain was in general lower than the background activity observed in the periphery. One hour post-injection, the levels of radioactivity per g blood and brain were determined and expressed as a percentage of the radioactivity administered to the animals. The radioactivity in the blood was found to be 19.1 and 21.0 times higher than that in the brain.

Figure 7.

Distribution of 123-I-iodoacetamide in the mouse head as visualized by multipinhole SPECT (transverse and sagittal views). The level of radioactivity in the SPECT images is proportional to the black – white gradation (black: low radioactivity, white: high radioactivity). For anatomical orientation, computer tomography (CT) images taken from another mouse are shown in the same way as the SPECT images. The crossing lines mark identical brain positions in the CT and SPECT images. From the SPECT images it can be seen that no significant focal or diffuse uptake of radioactivity was noted in the brain, whereas activity was detected in the soft tissue and bone. SPECT analysis of a second mouse gave similar results.

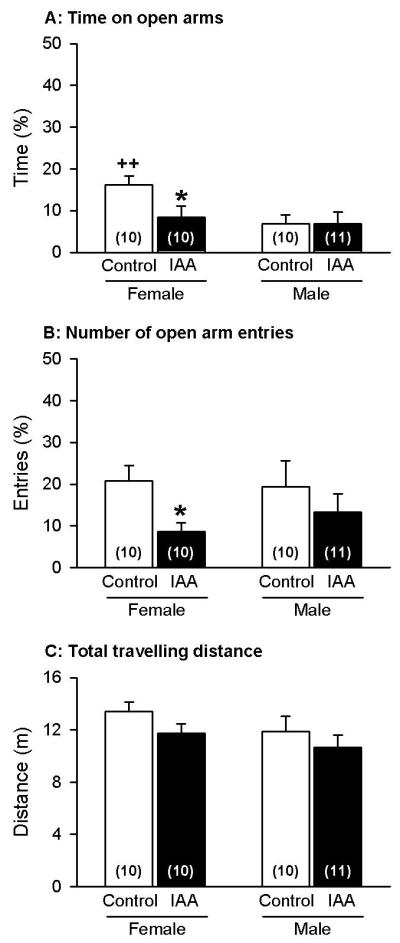

Effect of iodoacetamide treatment on anxiety-related behaviour

The anxiety-related behaviour was assessed with the EPMT and SIHT. In the EPMT, the number of entries into the open arms and the time spent on the open arms were taken as indices of anxiety. These parameters were expressed as a percentage of the total entries into and the total time spent on any arm during the 5 min test session. Planned comparison revealed that, in particular, female control mice spent significantly more time (t(18) = −3.13) on the open arms than male control mice (Figure 8A). Furthermore, it was found that iodoacetamide treatment significantly reduced the time that female mice spent on the open arms (t(18) = 2.26) but had no effect on male mice (Figure 8A). As a result, following iodoacetamide treatment male and female mice no longer differed in the duration of open arm exploration. Further analysis of the anxiety-related behaviour on the EPMT demonstrated that iodoacetamide treatment reduced the number of entries into the open arms (ANOVA for factor treatment: F(1,37) = 4.34, P < 0.05). In the post-hoc analysis it was found that the number of open arm entries was significantly decreased only in female, but not male iodoacetamide-treated mice (t(18) = 2.89), while male and female control mice did not differ in this parameter (Figure 8B).

Figure 8.

Behaviour of control and iodoacetamide-treated mice of either gender in the EPMT, performed on day 15 in the course of the experiments. The animals drank either normal tap water (control) or tap water containing iodoacetamide (0.1 %) from experimental day 8 onwards. The graphs show the time spent on the open arms (A), the number of their entries into the open arms (B), and the total distance travelled in the open and closed arms during the 5 min test session. The values represent means ± SEM, n as indicated in brackets. * P < 0.05 versus control mice of the same gender; ++ P < 0.01 versus male control mice.

In order to obtain a measure of overall locomotor activity, the total distance travelled in the open and closed arms during the 5 min test session was calculated. Female control mice travelled a nominally longer distance than male control mice, and iodoacetamide treatment led to a nominal reduction of the total travelling distance in male and female mice (Figure 8C), but neither difference reached statistical significance.

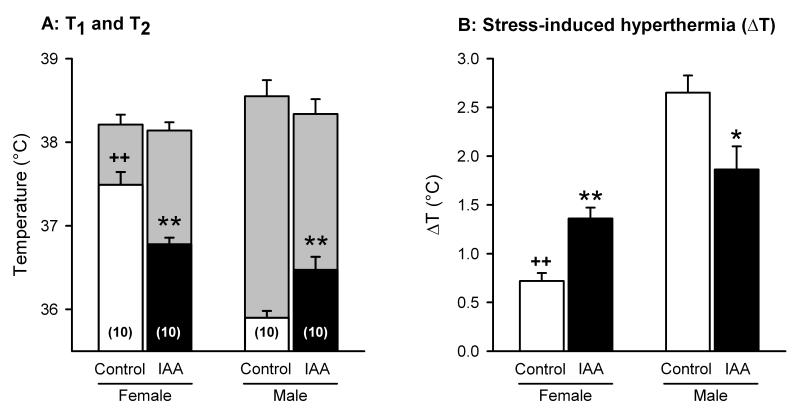

ANOVA of the basal rectal temperature (T1) measured in the SIHT showed that this parameter was gender-dependent (F(1,37) = 56.72, P < 0.01) and that there was an interaction between gender and iodoacetamide treatment (F(1,37) = 25.93, P < 0.01). In the post-hoc-analysis, T1 in male control mice turned out to be significantly lower than in female control mice (Tukey HSD test: P < 0.01; Figure 9A). Following iodoacetamide treatment, T1 significantly decreased in female mice (Tukey HSD test: P < 0.01) and significantly increased in male mice (Tukey HSD test: P < 0.01; Figure 9A). As a consequence, T1 of iodoacetamide-treated mice was no longer subject to any gender difference.

Figure 9.

Behaviour of control and iodoacetamide-treated mice of either gender in the SIHT, performed on day 16 in the course of the experiments. The animals drank either normal tap water (control) or tap water containing iodoacetamide (0.1 %) from experimental day 8 onwards. On the experimental day the rectal temperature was measured twice at an interval of 13 min. In panel A, the lower part of the columns depicts the rectal temperature recorded at the first measurement (T1), and the upper part of the columns shows the rectal temperature recorded at the second measurement (T2). In panel B, the stress-induced hyperthermia (ΔT = T2 - T1) is shown. The values represent means ± SEM, n as indicated in brackets. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 versus control mice of the same gender; ++ P < 0.01 versus male control mice.

Stress-induced hyperthermia was determined by a second measurement of rectal temperature (T2) 13 min after recording of T1 and expressed as the difference ΔT = T2 - T1. At this second measurement, the rectal temperature (T2) did not exhibit any gender- and treatment-related differences (Figure 9A). ANOVA of ΔT (Figure 9B) revealed that this parameter was gender-dependent (F(1,37) = 52.44, P < 0.01) and that there was an interaction between gender and iodoacetamide treatment (F(1,37) = 18.01, P < 0.01). ΔT was significantly larger in male control mice than in female control mice (Tukey HSD test: P < 0.01; Figure 9B). Iodoacetamide treatment enhanced ΔT in female mice (Tukey HSD test: P < 0.01) and reduced it in male mice (Tukey HSD test: P < 0.05) so that ΔT no longer differed between male and female animals (Figure 9B).

Relationship between oestrous cycle, anxiety-related behaviour and corticosterone levels

Pilot experiments involving 30 female mice housed in groups of 3 revealed that the oestrous cycle was largely synchronized among the 10 cages under study. Thus, 24 of the 30 mice were found to be in the oestrus stage on a given day. In the proper experiments, another cohort of 30 female mice was divided into 6 groups of 5 mice each, each group being tested on the EPMT on 6 consecutive days. Due to irregularities in cycling, 16 mice were found to be in the oestrus phase, while 8, 4 and 4 mice were in the metoestrus, prooestrus and dioestrus phase, respectively, at the time of testing. Because of this imbalance in the distribution of the different oestrous cycle phases, the data obtained in the met-, pro- and dioestrus stages were pooled in a common group termed nonoestrus phase. There was no significant correlation between the time spent on the open arms and the oestrus and nonoestrus phase (Table 1).

Table 1.

Lack of correlation between oestrus phase and anxiety as well as circulating corticosterone at baseline and following restraint stress

| Parameter under study | Oestrus | Nonoestrus | Correlation coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time spent on open arms (EPMT) | 9.0 ± 2.1 % (16) | 10.5 ± 2.8 % (14) | −0.0540 |

| Circulating corticosterone at baseline | 50.3 ± 10.4 ng/ml (12) | 45.2 ± 7.5 ng/ml (18) | 0.0765 |

| Circulating corticosterone after restraint stress | 97.5 ± 17.4 ng/ml (12) | 102.4 ± 16.1 ng/ml (18) | 0.0118 |

Thirty female mice were distributed to 6 groups of 5 mice each. Groupwise testing of the animals on the EPMT and collecting blood before and after stress on consecutive days allowed for analysis of the relationship between oestrus phase and anxiety as well as circulating corticosterone. There was no significant correlation of the time spent on the open arms in the EPMT (expressed as a percentage of the total time spent on any arm during the 5 min test session) and the circulating corticosterone levels (measured before and 45 min after the onset of a 10 min exposure to restraint stress) with the oestrous cycle. The nonoestrus stage comprises the met-, pro- and dioestrus phases. The values represent means ± SEM, n as indicated in brackets.

The same result was found when, after a pause of more than one week, the relationship between oestrous cycle phase and circulating corticosterone at baseline and following stress exposure was examined. After measuring baseline levels of corticosterone, the animals were subjected to restraint stress for 10 min, and corticosterone levels were measured 45 min after the onset of restraint stress. As shown in Table 1, there was no significant correlation of the oestrus and nonoestrus phase with baseline as well as stress-induced corticosterone levels (Table 1).

Effect of iodoacetamide treatment on stress-coping behaviour in the tail suspension test

The time of immobility during a 6 min test period was assessed as a measure of depression-like behaviour and expressed as a percentage of the test duration. Male and female control mice did not differ in the relative time of immobility, and this parameter was not altered by iodoacetamide treatment (Table 2).

Table 2.

Time of immobility in control and iodoacetamide-treated mice of either gender subjected to the TST

| Gender | Treatment | Time of immobility (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Female | Control | 29.2 ± 2.5 (7) |

| Female | Iodoacetamide | 24.0 ± 4.6 (10) |

| Male | Control | 27.2 ± 5.3 (10) |

| Male | Iodoacetamide | 27.0 ± 4.1 (11) |

The animals drank either normal tap water (control) or tap water containing iodoacetamide (0.1 %) from experimental day 8 onwards; they were subjected to the TST on day 18 in the course of the experiments. In this test, the time of immobility was assessed during a 6 min observation period and expressed as a percentage of the total test duration. The values represent means ± SEM, n as indicated in brackets. There was no significant gender and treatment effect. The number of animals in the female control group was only 7, because 3 female control mice escaped from the force displacement transducer during the test procedure.

DISCUSSION

In view of the emerging evidence that anxiety and depression are factors relevant to both IBD and pain-related bowel disorders (Mayer and Collins, 2002; Whitehead et al., 2002; Spiller, 2003; Mawdsley and Rampton, 2005; Talley, 2006) the overall aim of the present study was to test for a possible relationship between gastric inflammation and anxiety- and depression-related behaviour in mice. While it has previously been shown that experimentally induced depression- and anxiety-like phenotypes enhance the vulnerability to intestinal inflammation (Varghese et al., 2006) and lead to colonic hypersensitivity (Bradesi et al., 2005; Myers et al., 2005), it has not yet been explored whether gastrointestinal inflammation has an impact on affective behaviour. The results of the current study show that experimentally induced gastritis causes behavioural alterations indicative of enhanced anxiety but does not change stress-coping and depression-related behaviour.

The behavioural reactions to experimental gastritis were studied here for two reasons. Firstly, there is clinical evidence for a comorbidity of functional dyspepsia with anxiety. Experimentally induced anxiety in human volunteers decreases gastric compliance and lowers the intragastric volume that induces discomfort (Geeraerts et al., 2005). Both types of alterations are also found in patients with functional dyspepsia (Tack et al., 2004), in which both anxiolytic and antidepressant treatment has a beneficial effect (Hojo et al., 2005). Secondly, iodoacetamide-induced gastritis in rats is associated with hypersensitivity to both mechanical and chemical noxious stimulation of the stomach. As a result, iodoacetamide-induced gastritis has been proposed to represent an experimental model of dyspepsia (Ozaki et al., 2002; Lamb et al., 2003).

Iodoacetamide was added to the drinking water at a concentration of 0.1 % for 7 days, which has been shown to elicit murine gastritis (Piqueras et al., 2003) as confirmed by a significant increase in MPO activity in the gastric wall. This parameter reflects inflammation-associated infiltration of neutrophils and monocytes into the tissue (Suzuki et al., 1983; Krawisz et al., 1984; Graff et al., 1998) and is consistent with the iodoacetamide-induced infiltration of inflammatory cells and histological indices of inflammation in the gastric mucosa and submucosa (Piqueras et al., 2003; Takeeda et al., 2004). Although immune cells could be seen in the mucosa and submucosa of iodoacetamide-pretreated Swiss CD-1 mice (Piqueras et al., 2003), the rise of MPO activity which iodoacetamide treatment caused in the stomach of Him:OF1 mice was apparently too moderate to be seen as an appreciable accumulation of immune cells by routine histology. The effect of iodoacetamide to cause mild injury to the gastric surface epithelium (Holzer et al., 2007) was confirmed in the present study which, in addition, revealed that the adverse effect of iodoacetamide was confined to the stomach but did not involve the mucosa of the small and large intestine.

A potential drawback of the iodoacetamide gastritis model is the significant reduction of water intake that occurs if iodoacetamide is added to the drinking water, which along with a reduction of body weight has been noted previously (Ozaki et al., 2002; Piqueras et al., 2003; Holzer et al., 2007). Analysis of the circadian activity patterns revealed that iodoacetamide reduced drinking and feeding only during the dark phase to a significant extent. This observation suggests that the reduction of water intake is not primarily taste-related but, together with the decrease in feeding and locomotor activity, reflects a behavioural consequence of gastritis. We base this argument on the premise that a reduction of locomotor activity, feeding and drinking is a characteristic of sickness behaviour (Goehler et al., 2000; Konsman et al., 2002). Since water intake, expressed as ml per g body weight, was practically identical in either gender, the dosing of iodoacetamide per g body weight must have been similar in male and female mice. Thus, differences in iodoacetamide intake cannot account for the gender-related alterations in MPO, corticosterone and anxiety scores measured after a 7 day period of iodoacetamide treatment.

Since pain-related bowel disorders have a higher prevalence in women than in men (Strid et al., 2001; Chang and Heitkemper, 2002; Taché et al., 2005), we used both male and female mice to test for gender differences in the possible impact of gastric inflammation on affective behaviour. Indeed, gender-dependent differences in the severity of iodoacetamide-induced gastritis and its effect on circulating corticosterone, body temperature and anxiety were observed. Although the oestrous cycle of the female mice in these experiments was not determined, it is unlikely that our data were significantly influenced by this factor, because the results obtained from male and female mice did not differ in the coefficient of variation. This inference was confirmed by the observation that the anxiety-related behaviour on the EPMT and the levels of circulating corticosterone at baseline and following restraint stress did not differ between mice in the oestrus stage and those in the nonoestrus stage. We conclude, therefore, that the gastritis-associated changes in these parameters among female mice do not reflect fluctuations of female sex steroids during the oestrous cycle. Whether long-term effects of oestrogen determine the gender-related effects of iodoacetamide-induced gastritis remains to be investigated.

Treatment of mice with iodoacetamide for one week enhanced gastric MPO activity, the increase in female mice being significantly larger than that in male mice. It appears, therefore, that female mice are more vulnerable to iodoacetamide-evoked gastritis than male mice. This gender difference disappeared after the mice had been subjected to behavioural testing over the next 4 days, as gastric MPO activity in iodoacetamide-treated female mice fell to that seen in male iodoacetamide-treated mice. Whether this anti-inflammatory effect is related to the behavioural test procedure or reflects habituation to the exaggerated inflammatory reaction in female mice cannot be deduced from the present results. In contrast, the behavioural test procedure which is inherently stressful caused a non-significant rise of gastric MPO activity in the control mice, which is reminiscent of the ability of stress to adversely affect gastrointestinal mucosal function in normal rodents (Taché and Perdue, 2004).

Female mice with iodoacetamide-induced gastritis exhibited enhanced anxiety-related behaviour as assessed in the EPMT (Pellow and File, 1986; Belzung and Griebel, 2001). Iodoacetamide treatment reduced both the number of entries into the open arms and the time spent on the open arms in female, but not male mice. Although it could be argued that iodoacetamide treatment failed to reduce the time that male mice moved on the open arms, because male control mice spent significantly less time on the open arms than female control mice, this argument is not applicable to the number of open arm entries in which male and female control mice did not significantly differ. In addition, iodoacetamide treatment failed to significantly attenuate the overall locomotor activity of male and female mice in the EPMT, which is in keeping with the finding that homecage activity did not change during the light phase. We conclude, therefore, that experimental gastritis has an anxiogenic effect in female, but not male, mice and relate this gender difference to the severity of gastritis which was greater in female than in male animals.

The gender-related increase in anxiety due to gastritis went in parallel with a decrease in the basal levels of circulating corticosterone, which is likely to reflect reduced activity in the HPA axis (Engelmann et al., 2004). The observation that the iodoacetamide-induced fall in circulating corticosterone was seen only under basal conditions, but not after exposure to the stressful TST, argues against a downregulation of the HPA axis. Since repeated stress is known to increase trait anxiety (Chotiwat and Harris, 2006), prolonged gastritis could be viewed as an internal stressor that enhances anxiety-like behaviour and causes habituation of the HPA axis (Armario et al., 2004) in a gender-dependent manner. Since iodoacetamide does not enter the brain to any appreciable degree, as visualized by SPECT, we conclude that the effects of iodoacetamide on trait anxiety and HPA axis activity are brought about by a peripheral site of action, most likely as a consequence of low-grade gastritis. Gastritis may be signalled to the brain via hypersensitivity of afferent nerve pathways (Lamb et al., 2003; Holzer et al., 2007) or via endocrine routes involving proinflammatory cytokines (Turnbull and Rivier, 1999). It can at present not be ruled out that disturbances in fluid, electrolyte and hormonal homeostasis, resulting from decreased intake of water and food, may also contribute to the iodoacetamide-induced alterations of brain functions.

Our finding of reduced corticosterone levels in female mice suffering from low-grade gastritis is in line with a report that basal cortisol levels in the saliva of patients with functional dyspepsia or irritable bowel syndrome are lower than in healthy controls (Bohmelt et al., 2005). In addition, our experimental approach takes account of the emerging association of functional gastrointestinal disorders with low-grade inflammation, increased anxiety and female gender (Wilhelmsen et al., 1995; Mayer et al., 2001a; Strid et al., 2001; Chang and Heitkemper, 2002; Whitehead et al., 2002; Dunlop et al., 2003; Tornblom et al., 2005; Talley, 2006). The ability of iodoacetamide to induce gastric hyperalgesia (Lamb et al., 2003; Holzer et al., 2007) and to cause low-grade gastric inflammation, enhance trait anxiety and lower circulating corticosterone levels in a gender-related manner (this study) reproduces several aspects of pain-related bowel disorders with a remarkable degree of face validity.

Relative to the EPMT, the SIHT has the advantage of assessing anxiety phenotypes in a locomotion-independent manner (Zethof et al., 1994; Olivier et al., 2003). In the present study, however, this test was complicated by gender-dependent differences in the baseline rectal temperature (T1) and treatment-induced changes of T1. While T1 in male control mice was significantly lower than that of female control mice, iodoacetamide treatment decreased T1 in female mice and increased it in male mice so that T1 was no longer different between the two genders. The effect of iodoacetamide-induced gastritis on body temperature points to complex thermoregulatory changes associated with gastrointestinal pathology. Stress-induced hyperthermia (ΔT) is thought to be a homeostatic reaction that involves the central as well as sympathetic nervous system (Oka et al., 2001; Liu et al., 2003; DiMicco et al., 2006). In the present study it was found that iodoacetamide treatment enhanced ΔT in female and reduced it in male mice, relative to ΔT seen in control animals. We think, however, that this observation cannot be interpreted as evidence for gastritis-induced anxiety in female mice, because both T1 and ΔT were subject to complex gender-and treatment-related differences and T2 was independent of gender and treatment. Thus, ΔT in female control mice may have been cut short by a ceiling effect, given that T1 was highest in these animals. As a result, we propose that the SIHT can be used to assess anxiety only if T1 is not affected by gender and experimental manipulation.

Depression-like behaviour was evaluated with the TST which measures the stress-coping ability of the animals (Steru et al., 1985; Liu and Gershenfeld, 2001; Cryan et al., 2005). As iodoacetamide treatment failed to alter the relative time of immobility in this test in both male and female mice (Table 2), we conclude that experimental gastritis does not induce behavioural changes indicative of depression. This inference is backed by the observation that the TST-evoked elevation of circulating corticosterone was similar in control and iodoacetamide-treated animals. It is known that, after exposure of mice to a stressful situation, circulating corticosterone rises to a maximum within 10-20 min and subsequently wanes off due to corticosterone-mediated feedback inhibition of the release of corticotropin-releasing factor and adrenocorticotrophic hormone (Müller et al., 2003; Oshima et al., 2003). In view of these dynamics of the HPA axis we infer that stress-induced activation and feedback inhibition of the HPA axis was not altered by iodoacetamide treatment, whereas depression is known to be associated with elevated levels of circulating corticosterone, or cortisol in humans, due to impaired feedback inhibition of the HPA axis (Holsboer, 2000; Cryan and Mombereau, 2004).

In summary, we have shown that iodoacetamide treatment induces gastritis in a gender-related manner, its severity being significantly greater in female than in male mice. The induction of exaggerated gastritis in female mice is associated with a reduction of circulating corticosterone and body temperature and an enforcement of behavioural indices of anxiety. Gastric inflammation thus has a gender-dependent influence on emotional-affective behaviour and its neuroendocrine regulation. In a wider perspective, our findings suggest that not only stress and psychiatric disorders can give rise to functional disturbances of the gut but that gastrointestinal pathology also can impact on the central nervous system to affect mood and its neuroendocrine control.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by the Zukunftsfonds Steiermark (grant 262), the Austrian Scientific Research Funds (FWF grant L25-B05) and a scholarship grant of the Interdisciplinary Centre for Clinical Research at the University of Würzburg (MCK). The authors thank Dr. Michael Trappitsch (Graz) for his invaluable help in the development of the TST software and Dr. Adelheid Kresse (Graz) for her advice on the analysis of the oestrous cycle. The support by the director and staff of the Center for Medical Research (ZMF I) of the Medical University of Graz is also greatly appreciated.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- EDTA

ethylenediamine tetraacetate

- EPMT

elevated plus maze test

- HPA axis

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- SIHT

stress-induced hyperthermia test

- TST

tail suspension test

REFERENCES

- Armario A, Valles A, Dal-Zotto S, Marquez C, Belda X. A single exposure to severe stressors causes long-term desensitisation of the physiological response to the homotypic stressor. Stress. 2004;7:157–172. doi: 10.1080/10253890400010721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belzung C, Griebel G. Measuring normal and pathological anxiety-like behaviour in mice: a review. Behav Brain Res. 2001;125:141–149. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohmelt AH, Nater UM, Franke S, Hellhammer DH, Ehlert U. Basal and stimulated hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders and healthy controls. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:288–294. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000157064.72831.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradesi S, McRoberts JA, Anton PA, Mayer EA. Inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome: separate or unified? Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2003;9:336–342. doi: 10.1097/00001574-200307000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradesi S, Schwetz I, Ennes HS, Lamy CM, Ohning G, Fanselow M, Pothoulakis C, McRoberts JA, Mayer EA. Repeated exposure to water avoidance stress in rats: a new model for sustained visceral hyperalgesia. Am J Physiol. 2005;289:G42–G53. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00500.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Heitkemper MM. Gender differences in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1686–1701. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chotiwat C, Harris RB. Increased anxiety-like behavior during the post-stress period in mice exposed to repeated restraint stress. Horm Behav. 2006;50:489–495. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryan JF, Mombereau C. In search of a depressed mouse: utility of models for studying depression-related behavior in genetically modified mice. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:326–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryan JF, Mombereau C, Vassout A. The tail suspension test as a model for assessing antidepressant activity: review of pharmacological and genetic studies in mice. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:571–625. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMicco JA, Sarkar S, Zaretskaia MV, Zaretsky DV. Stress-induced cardiac stimulation and fever: common hypothalamic origins and brainstem mechanisms. Auton Neurosci. 2006;126-127:106–119. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop SP, Jenkins D, Neal KR, Spiller RC. Relative importance of enterochromaffin cell hyperplasia, anxiety, and depression in postinfectious IBS. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1651–1659. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelmann M, Landgraf R, Wotjak CT. The hypothalamic-neurohypophysial system regulates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis under stress: an old concept revisited. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2004;25:132–149. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick KM, Burlingame LA, Arters JA, Berger-Sweeney J. Reference memory, anxiety and estrous cyclicity in C57BL/6NIA mice are affected by age and sex. Neuroscience. 2000;95:293–307. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00418-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geeraerts B, Vendenberghe J, van Oudenhove L, Gregory LJ, Aziz Q, Dupont P, Demyttenaere K, Janssens J, Tack J. Influence of experimentally induced anxiety on gastric sensorimotor function in humans. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1437–1444. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goehler LE, Gaykema RPA, Hansen MK, Anderson K, Maier SF, Watkins LR. Vagal immune-to-brain communication: a visceral chemosensory pathway. Auton Neurosci Basic Clin. 2000;85:49–59. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(00)00219-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff G, Gamache DA, Brady MT, Spellman JM, Yanni JM. Improved myeloperoxidase assay for quantitation of neutrophil influx in a rat model of endotoxin-induced uveitis. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 1998;39:169–178. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8719(98)00023-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hojo M, Miwa H, Yokoyama T, Ohkusa T, Nagahara A, Kawabe M, Asaoka D, Izumi Y, Sato N. Treatment of functional dyspepsia with antianxiety or antidepressive agents: systematic review. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:1036–1042. doi: 10.1007/s00535-005-1687-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holsboer F. The corticosteroid receptor hypothesis of depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23:477–501. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzer P, Wultsch T, Edelsbrunner M, Mitrovic M, Shahbazian A, Painsipp E, Bock E, Pabst MA. Increase in gastric acid-induced afferent input to the brainstem in mice with gastritis. Neuroscience. 2007;145:1108–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk RE. Experimental Design. Procedures for the Behavioral Sciences. Third edition Brooks/Cole; Pacific Grove, California: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Konsman JP, Parnet P, Dantzer R. Cytokine-induced sickness behaviour: mechanisms and implications. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:154–159. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)02088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawisz JE, Sharon P, Stenson WF. Quantitative assay for acute intestinal inflammation based on myeloperoxidase activity. Assessment of inflammation in rat and hamster models. Gastroenterology. 1984;87:1344–1350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb K, Kang YM, Gebhart GF, Bielefeldt K. Gastric inflammation triggers hypersensitivity to acid in awake rats. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1410–1418. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Gershenfeld HK. Genetic differences in the tail-suspension test and its relationship to imipramine response among 11 inbred strains of mice. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49:575–581. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Peprah D, Gershenfeld HK. Tail-suspension induced hyperthermia: a new measure of stress reactivity. J Psychiatr Res. 2003;37:249–259. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(03)00004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawdsley JE, Rampton DS. Psychological stress in IBD: new insights into pathogenic and therapeutic implications. Gut. 2005;54:1481–1491. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.064261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer EA, Collins SM. Evolving pathophysiologic models of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:2032–2048. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer EA, Craske M, Naliboff BD. Depression, anxiety, and the gastrointestinal system. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001a;62(Suppl 8):28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer EA, Naliboff BD, Chang L, Coutinho SV. Stress and the gastrointestinal tract. V. Stress and irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Physiol. 2001b;280:G519–G524. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.4.G519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milde AM, Arslan G, Overmier JB, Berstad A, Murison R. An acute stressor enhances sensitivity to a chemical irritant and increases 51CrEDTA permeability of the colon in adult rats. Integr Physiol Behav Sci. 2005;40:35–44. doi: 10.1007/BF02734187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Million M, Taché Y. Stress and the gut: peripheral influences. In: Spiller R, Grundy D, editors. Pathophyssiology of the Enteric Nervous System: A Basis for Understanding Functional Diseases. Blackwell; Oxford: 2004. pp. 90–101. [Google Scholar]

- Million M, Tache Y, Anton P. Susceptibility of Lewis and Fischer rats to stress-induced worsening of TNB-colitis: protective role of brain CRF. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G1027–G1036. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.4.G1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittermaier C, Dejaco C, Waldhoer T, Oefferlbauer-Ernst A, Miehsler W, Beier M, Tillinger W, Gangl A, Moser G. Impact of depressive mood on relapse in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective 18-month follow-up study. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:79–84. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000106907.24881.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulak A, Bonaz B. Irritable bowel syndrome: a model of the brain-gut interactions. Med Sci Monit. 2004;10:RA55–RA62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller MB, Zimmermann S, Sillaber I, Hagemeyer TP, Deussing JM, Timpl P, Kormann MS, Droste SK, Kuhn R, Reul JM, Holsboer F, Wurst W. Limbic corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 1 mediates anxiety-related behavior and hormonal adaptation to stress. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1100–1107. doi: 10.1038/nn1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CDR, Flynn J, Ratcliffe L, Jacyna MR, Kamm MA, Emmanuel AV. Effect of acute physical and psychological stress on gut autonomic innervation in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1695–1703. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers DA, Gibson M, Schulkin J, Greenwood Van-Meerveld B. Corticosterone implants to the amygdala and type 1 CRH receptor regulation: effects on behavior and colonic sensitivity. Behav Brain Res. 2005;161:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North CS, Downs D, Clouse RE, Alrakawi A, Dokucu M, Cox J, Spitznagel EL, Alpers DH. The presentation of irritable bowel syndrome in the context of somatization disorder. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:878–795. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00350-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka T, Oka K, Hori T. Mechanisms and mediators of psychological stress-induced rise in core temperature. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:476–486. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200105000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivier B, Zethof T, Pattij T, van Boogaert M, van Oorschot R, Leahy C, Oosting R, Bouwknecht A, Veening J, van der Gugten J, Groenink L. Stress-induced hyperthermia and anxiety: pharmacological validation. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;463:117–132. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01326-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima A, Flachskamm C, Reul JM, Holsboer F, Linthorst AC. Altered serotonergic neurotransmission but normal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis activity in mice chronically treated with the corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor type 1 antagonist NBI 30775. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:2148–2159. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki N, Bielefeldt K, Sengupta JN, Gebhart GF. Models of gastric hyperalgesia in the rat. Am J Physiol. 2002;283:G666–G676. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00001.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace F, Molteni P, Bollani S, Sarzi-Puttini P, Stockbrugger R, Porro GB, Drossman DA. Inflammatory bowel disease versus irritable bowel syndrome: a hospital-based, case-control study of disease impact on quality of life. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:1031–1038. doi: 10.1080/00365520310004524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellow S, File SE. Anxiolytic and anxiogenic drug effects on exploratory activity in an elevated plus-maze: a novel test of anxiety in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1986;24:525–529. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(86)90552-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peloso E, Wachulec M, Satinoff E. Stress-induced hyperthermia depends on both time of day and light condition. J Biol Rhythms. 2002;17:164–170. doi: 10.1177/074873002129002456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piqueras L, Corpa JM, Martinez J, Martinez V. Gastric hypersecretion associated to iodoacetamide-induced mild gastritis in mice. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 2003;367:140–150. doi: 10.1007/s00210-002-0670-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reber SO, Obermeier F, Straub HR, Falk W, Neumann ID. Chronic intermittent psychosocial stress (social defeat/overcrowding) in mice increases the severity of an acute DSS-induced colitis and impairs regeneration. Endocrinology. 2006;147:4968–4976. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwetz I, Bradesi S, Mayer EA. Current insights into the pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2003;2003(5):331–336. doi: 10.1007/s11894-003-0071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller RC. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1662–1671. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stam R, Akkermans LM, Wiegant VM. Trauma and the gut: interactions between stressful experience and intestinal function. Gut. 1997;40:704–709. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.6.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steru L, Chermat R, Thierry B, Simon P. The tail suspension test: a new method for screening antidepressants in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1985;85:367–370. doi: 10.1007/BF00428203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strid H, Norstrom M, Sjoberg J, Simren M, Svedlund J, Abrahamsson H, Bjornsson ES. Impact of sex and psychological factors on the water loading test in functional dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:725–730. doi: 10.1080/003655201300191987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Ota H, Sasagawa S, Sakatani T, Fujikura T. Assay method for myeloperoxidase in human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Anal Biochem. 1983;132:345–352. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeeda M, Hayashi Y, Yamato M, Murakami M, Takeuchi K. Roles of endogenous prostaglandins and cyclooxygenase isoenzymes in mucosal defense of inflamed rat stomach. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2004;55:193–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taché Y, Million M, Nelson AG, Lamy C, Wang L. Role of corticotropin-releasing factor pathways in stress-related alterations of colonic motor function and viscerosensibility in female rodents. Gend Med. 2005;2:146–154. doi: 10.1016/s1550-8579(05)80043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taché Y, Perdue MH. Role of peripheral CRF signalling pathways in stress-related alterations of gut motility and mucosal function. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16(Suppl 1):137–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-3150.2004.00490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tack J, Bisschops R, Sarnelli G. Pathophysiology and treatment of functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1239–1255. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley NJ. A unifying hypothesis for the functional gastrointestinal disorders: really multiple diseases or one irritable gut? Rev Gastroenterol Disord. 2006;6:72–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theander-Carrillo C, Wiedmer P, Cettour-Rose P, Nogueiras R, Perez-Tilve D, Pfluger P, Castaneda TR, Muzzin P, Schürmann A, Szanto I, Tschöp MH, Rohner-Jeanrenaud F. Ghrelin action in the brain controls adipocyte metabolism. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1983–1993. doi: 10.1172/JCI25811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tornblom H, Abrahamsson H, Barbara G, Hellstrom PM, Lindberg G, Nyhlin H, Ohlsson B, Simren M, Sjolund K, Sjovall H, Schmidt PT, Ohman L, Swedish Motility Group Inflammation as a cause of functional bowel disorders. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:1140–1148. doi: 10.1080/00365520510023657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull AV, Rivier CL. Regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis by cytokines: actions and mechanisms of action. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:1–71. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varghese AK, Verdu EF, Bercik P, Khan WI, Blennerhassett PA, Szechtman H, Collins SM. Antidepressants attenuate increased susceptibility to colitis in a murine model of depression. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1743–1753. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead WE, Palsson O, Jones KR. Systematic review of the comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other disorders: what are the causes and implications? Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1140–1156. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmsen I, Haug TT, Ursin H, Berstad A. Discriminant analysis of factors distinguishing patients with functional dyspepsia from patients with duodenal ulcer. Significance of somatization. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:1105–1111. doi: 10.1007/BF02064207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong HY, Chang L. Stress and the gut: central influences. In: Spiller R, Grundy D, editors. Pathophyssiology of the Enteric Nervous System: A Basis for Understanding Functional Diseases. Blackwell; Oxford: 2004. pp. 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Zethof TJ, Van der Heyden JA, Tolboom JT, Olivier B. Stress-induced hyperthermia in mice: a methodological study. Physiol Behav. 1994;55:109–115. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]