Abstract

The most recent work toward compiling a comprehensive database of adenosine-to-inosine RNA editing events suggests that the potential for RNA editing is much more pervasive than previously thought; indeed, it is manifest in more than 100 million potential editing events located primarily within Alu repeat elements of the human transcriptome. Pairs of inverted Alu repeats are found in a substantial number of human genes, and when transcribed, they form long double-stranded RNA structures that serve as optimal substrates for RNA editing enzymes. A small subset of edited Alu elements has been shown to exhibit diverse functional roles in the regulation of alternative splicing, miRNA repression and cis-regulation of distant RNA editing sites. The low level of editing for the remaining majority may be non-functional, yet their persistence in the primate genome provides enhanced genomic flexibility that may be required for adaptive evolution.

Keywords: RNA editing, Alu, ADAR, inosine

INTRODUCTION

Transposable repetitive elements make up approximately 42% of the human genome. The most common type of repetitive sequence is a class of highly-conserved small interspersed elements (SINES) known as Alu elements. These retrotransposable units are ~300 nucleotides in length, derived from 7SL RNA and make up more than 10% of the human genome. Alu sequences originated early in the evolution of primates, emerging around 65 million years ago [1]. They can be transcribed from an internal RNA polymerase III promoter or -- in cases where they are embedded into introns and 3’-untranslated regions of messenger RNAs (mRNAs) -- they also may be transcribed by RNA polymerase II [2]. Seventy-five percent of human genes contain Alu sequences, most frequently outside of protein coding regions [1]. Depending upon their location and content, Alu sequences may alter gene expression by introduction or modification of regulatory elements including promoters, polyadenylation signals, splice sites, transcriptional silencers/enhancers and translational regulators [3].

RNA editing

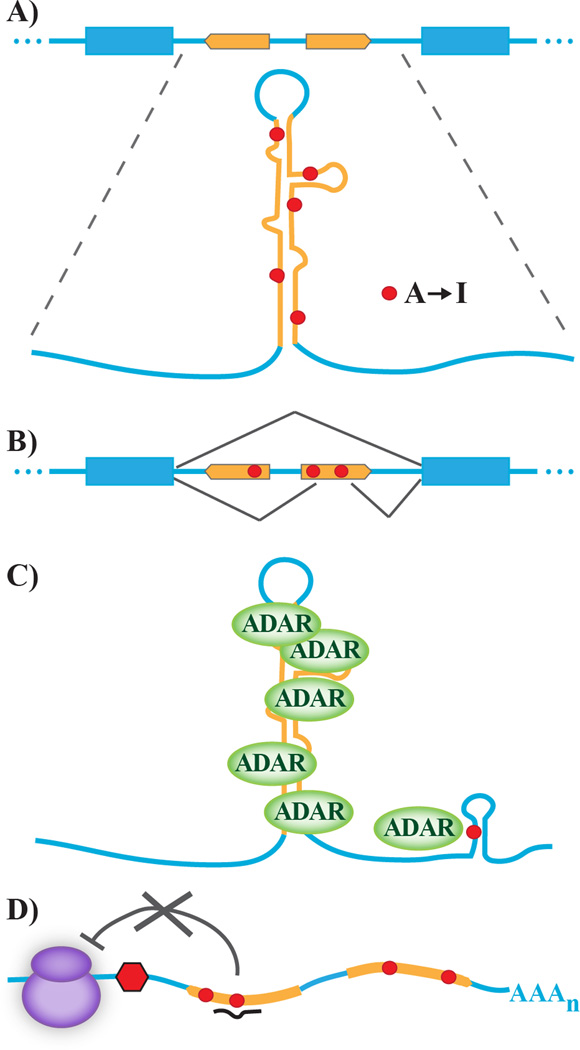

Pairs of Alu elements often integrate into one gene in opposing orientations. Intramolecular base pairing between the transcribed inverted repeats can result in the formation of an extended RNA duplex that can serve as a binding site for a large family of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)-binding proteins including adenosine deaminases acting on RNA (ADARs) Figure 1A) [4]. There are two highly conserved, catalytically active ADARs in mammals, ADAR1 and ADAR2 [5]. ADARs catalyze the site-selective hydrolytic deamination of adenosine nucleosides within dsRNA substrates, converting genomically-encoded adenosine residues to inosine (A-to-I). Since inosine has similar base pairing properties to guanosine, inosine is recognized as guanosine by the cellular translation machinery, hence altering amino acid coding potential [4]. For example, editing of transcripts encoding the GluR-2 subunit of the AMPA-subtype of glutamate receptor changes a genomically-encoded glutamine (CAG) to an arginine (CIG) codon [6]. This editing event modulates the electrophysiological and ion-permeation properties of the channel; it occurs in nearly all GluR-2 mRNAs, and is essential for viability in mice [4]. A-to-I editing often occurs in clusters within a given transcript, as exemplified by transcripts encoding the 2C-subtype of serotonin receptor (5HT2C), where up to five adenosines can be modified by A-to-I editing to alter the identity of three amino acids within the second intracellular loop of this G-protein coupled receptor. Editing generates up to 32 mRNA isoforms that can be translated to produce 24 receptor proteins that differ in their extent of G-protein coupling efficacy and constitutive activity. Dysregulation of 5HT2C editing has been implicated in a number of mood disorders including anxiety, suicide and depression [4].

Figure 1.

Functional roles of A-to-I editing in Alu elements. A: Alu inverted repeat elements (gold) are often present in non-coding regions, such as introns. Intramolecular base paring between Alu repeats results in long stretches of double stranded RNA that are subject to multiple ADAR-catalyzed A-to-I editing events (red dots) throughout its length. B: Exonization model of Alu editing. A-to-I editing may facilitate conversion of non-canonical splice site to an optimal splice signal (the illustrated model suggests conversion from AA to AI to generate a canonical 3’-splice site), thereby allowing alternative splicing of edited transcripts. C: ADAR recruitment model of Alu editing. Extended RNA duplex structures formed by intramolecular base pairing of inverted repeat sequences allow extensive recruitment of ADAR proteins to the Alu-containing transcript, enhancing A-to-I editing at proximal regions that contain non-optimal RNA editing sites. D: Derepression model of Alu editing. RNA editing within the seed region of miRNA binding sites may disrupt small RNA binding in 3’-UTR regions, thereby inhibiting miRNA-mediated repression of translation.

RNA editing alters RNA processing events

In addition to non-synonymous amino acid changes, ADAR-catalyzed RNA editing has the potential to alter signals required for RNA processing events. For example, ADAR2 can modulate its own expression by editing its pre-mRNA to generate an alternative 3’-splice site (AI) that produces a mature mRNA with an altered translation frame and premature stop codon [7]. Alu sequences often contain cryptic splice signals that, with subtle alteration, have the ability to become alternative splicing signals. In fact, it is estimated that ~5% of alternative exons in the human transcriptome result from the presence of Alu sequences [1]. In some cases, RNA editing can facilitate the exonization of Alu elements [8]. Human nuclear prolamin A recognition factor (NARF) contains inverted Alu elements within its pre-mRNA, following exon 7. Inclusion of an alternative exon 8, containing an Alu sequence, requires the presence of a more distal Alu element in the opposite orientation (Figure 1B) [9]. Multiple sites within this alternative exon are subject to highly-efficient RNA editing events, leading to the recoding of a premature stop (UAG) to tryptophan (UIG) codon and the alteration of a non-canonical 3’-splice junction (AA) to a functional splice site (AI), thereby allowing the inclusion of a 46 amino acid primate-specific exon [9,10].

NEXT-GENERATION SEQUENCING AND THE EXPANSION OF THE ALU EDITOME

The process of identifying A-to-I editing events has undergone rapid evolution since the serendipitous identification of editing sites in mRNAs for the GluR-2 subunit and the 5HT2C receptor. In the 1990s and early 2000s, the limited availability of genomic sequence information slowed the identification of additional editing sites using bioinformatic strategies in which such editing sites were identified using expressed sequence tags (ESTs) and potential discrepancies with genomic DNA sequences [11]. The error-prone nature of these studies was improved upon by the use of comparative genomics to distinguish editing sites from single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), mutations and sequencing errors [11,12]. The throughput of candidate-based approaches, including gene capture and biochemical methods to modify and identify inosines, was bolstered by the increasing availability of next-generation sequencing data [12,13]. In the last few years, many studies have emerged that attempt to identify bona fide targets of RNA editing by comparing the RNA and DNA sequences from single individuals using publically available RNA-seq data [11,14–17]. Unfortunately, these studies are error-prone, largely because of sequencing errors, the large number of unmapped SNPs, and the difficulty of accurately mapping short reads to the genome [11,14–17]. Still other studies dispensed with the need to match RNA/cDNA sequences to the genome, and utilized cross-species and/or cross-individual comparisons for filtering purposes [18–20]. While each individual approach mapped a relatively unique subset of RNA editing targets, the combination of these efforts revealed a set of common characteristics regarding A-to-I conversion. For example, while ADAR-mediated editing is dependent upon a duplex RNA structure rather than a specific sequence motif, an under- and over-representation of guanosine moieties was observed immediately upstream and downstream from the edited nucleoside(s), respectively. Furthermore, editing sites were commonly observed in clusters within a given transcript, and the overwhelming majority of these editing sites occurred within Alu repetitive elements. Even so, the output of each transcriptome-wide analysis varied significantly between studies, with minimal overlap [21], thereby producing an ever-expanding collection of putative editing sites.

By 2013, more than 1.4 million RNA editing sites had been identified computationally [11], yet several lines of evidence suggested that this was still a gross underestimation of the total A-to-I editing events within the human transcriptome. The lack of overlap in identified editing sites between multiple studies suggested that the population of novel sites had not been saturated, and that biases in experimental approaches may have led to unique subpopulations of edited RNAs being overlooked [21]. One such subpopulation of overlooked transcripts included RNAs that are modified at multiple sites (hyper-edited) within a single duplex region of the RNA target. These transcripts were most likely missed because most genome mapping strategies cannot effectively align the parental DNA sequence when the sequence of the cDNA has been altered extensively by A-to-I conversion within individual RNA transcripts. One recent study sought to specifically identify hyper-edited substrates in the human genome by simply replacing the As with Gs in the genome and realigning ESTs [22]. This approach identified more than 15,000 editing sites within 760 hyper-edited ESTs, the vast majority of which were found to occur within Alu elements, suggesting that the editing of Alu sequences is much more prevalent that previously appreciated.

Revisiting the Alu editome

The pervasiveness of A-to-I editing sites within Alu sequences was best illustrated recently in a study by Bazak and colleagues [21], where over 100 million adenosines -- representing nearly every adenosine within transcribed inverted repeat Alu elements -- were found to be subject to some level of RNA editing. To arrive at this estimate, RNA-seq data was initially assessed for the presence of transcribed Alu sequences, in which nearly 80% of the Alu elements within the human genome were found to be expressed; this estimate may still be an underrepresentation, because of unmappable, hyper-edited substrates. To identify potential RNA editing sites within Alu elements, transcribed sequences were examined for discrepancies with a reference genome. Since RNA editing within Alu elements commonly affects editing at neighboring adenosines, additional filters were applied that identify several mismatches clustered within a stretch of RNA [15,16]. More than 1.5 million A-to-G (or T-to-C) mismatches met experimental criteria, and further confirmed that the overwhelming majority of Alu editing occurs in non-coding regions, namely introns [4,11].

While previous studies indicated that editing events resulting in non-synonymous amino acid changes are enriched in neuronal transcripts [4], modification of human Alu sequences did not show such a preference [21]. This property may be unique to humans, however, because other studies have observed the same lack of tissue-specific enrichment for editing sites identified from humans, but re-establish the brain preference when comparing conserved editing events between humans and other primates [19]. This potential lack of tissue-specific editing in humans may result from the promiscuous activity of ADAR enzymes that occurs at a low-cost to fitness and thus lacks negative evolutionary selection. Alternatively, the editing of Alu sequences could provide an undefined evolutionary advantage to humans, resulting in constitutive modification in all tissues. Of course, these models do not account for potential tissue-specific hyper-editing that may render a portion of Alu-containing RNAs unmappable using conventional data-mining paradigms.

Enhanced sequence coverage increases sensitivity and accuracy of editing detection

Bazak and colleagues [21], like other investigators [16], noted that inadequate sequence coverage may account for some of the lack of overlap in identified editing targets across multiple studies. To address this issue, they developed their own ultra-deep sequencing protocol and noted that at least 1000× coverage was required to saturate the number of A-G mismatches detected in Alu regions, far exceeding the read depth provided by typical transcriptome-wide RNA-seq data. Since the extent of editing for most of the newly identified editing sites was <1%, this enhanced sequence depth was critical for detection of novel editing targets [21]. Thus, in addition to hyper-edited RNA species, low-level editing targets are underrepresented and require greater sequencing coverage than provided by most currently available transcriptome profiles. As the level of coverage increases, so does the likelihood of sequencing errors, suggesting that low-level editing could represent A-to-G sequencing errors. Interestingly, non-AG sequence discrepancies reached saturation well below 1000× read coverage [21], thus increased depth of sequencing increases both sensitivity and accuracy of editing detection. Current sequencing technologies have the ability to detect sequence alterations, such as RNA editing events, that occur at extremely low levels [23]. While the rarest of these events could be functionally important, they most likely represent enhanced detection of normal biological noise due to widespread expression and low-level imprecision in the activity of ADAR enzymes.

The human editome includes more than 100 million adenosine residues

Nearly 65% of Alu elements in the human genome were defined as editable by Bazak and colleagues [21]. An editable Alu element was one in which an opposing Alu sequence was located within 3500 bp for efficient duplex formation [24] and each repeat maintained a sufficiently conserved Alu consensus. About 25% of editable Alu elements were shown to contain potential edited nucleosides using existing RNA-seq data; however, based upon the hypothesis that all editable Alu sequences are modified by A-to-I conversion but remain unreported due to inadequate sequencing, a sample of 80 Alu elements was further analyzed by ultra-deep sequencing, revealing that 100% of these expressed Alu sequences contain A-to-I modifications. Surprisingly, all of the adenosines in both strands of the Alu repeats seemed to have editing potential. This observation suggested that each adenosine in an editable Alu element may serve as a substrate for ADAR-mediated A-to-I conversion, adding up to 105.7 Mbp or 1.5% of the entire human genome. This is a strikingly large number of potential editing sites! Although the editing level at most sites was low (median = 0.475%), it amounts to a much greater population of edited RNA targets than previously thought. Even so, this is still likely to be an underestimate, as it excludes potential editing events within Alu inverted repeats that did not meet the criteria for sequence conservation, Alu proximity, or those that might be edited duplex formation in trans [25].

The mouse genome contains a comparable number of inverted repeat elements to the human genome and also encodes highly conserved ADAR enzymes, yet it has been predicted that mice exhibit an editing abundance at least ten-fold less than that observed in humans. This observation is due, almost exclusively, to the divergence of mouse repeat elements during evolution. In humans, the prominent repeat content is represented by evolutionarily recent Alu sequences that show significantly more sequence similarity [26]. The greater number of mouse generations that have occurred during evolution, as compared to the number of primate generations, has presumably increased the divergence of repeat elements, thereby decreasing their ability to effectively base pair and serve as substrates for A-to-I modification. We predict that over time, non-functional Alu repeats in the primate genome also will show an enhanced sequence diversity and lose their ability to effectively form the dsRNA regions critical for ADAR recognition.

IS THERE A PURPOSE FOR PERVASIVE ALU EDITING?

Initial studies of RNA editing successfully identified functionally relevant ADAR editing sites by focusing upon those sites that are phylogenetically conserved. This approach identified sequences with relatively high editing rates and supported the idea that editing commonly maintains sequences of more ancient genomes [18,27]. Alu editing, on the other hand, lacks conservation between even closely related primate species [17] and the extent of editing at most edited adenosines within Alu elements occurs at extremely low levels. Together, these observation suggest that the majority of Alu editing is functionally irrelevant, as it simply reflects the extensive occurrence of Alu repeat elements in the primate genome combined with near-ubiquitous ADAR expression.

Alu elements can serve as cis-active editing enhancers

Editing of Alu elements within transcripts encoding NARF allows the inclusion of a primate-specific Alu-exon through the creation of both a functional 3'-splice junction (AI) and alteration of splicing enhancers within the exon. While the functional importance of this alternative splicing event has not been determined, there is an interdependence between editing sites in the NARF intron and the alternative exon that presumably results from their inclusion in a shared secondary structure to recruit ADAR proteins (Figure 1B) [9]. However, an additional role for Alu duplexes is illustrated in transcripts where distinct editing sites on the same transcript -- but not contained within the same region of dsRNA -- show a dependent relationship (Figure 1C). Transcripts encoding the α3-subunit of the gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor (GABRA3), a DNA repair enzyme (NEIL1), glioma-associated oncogene homolog 1 (Gli1) and zinc finger protein 14 (ZFP14) each contain an exonic editing site that depends upon an extended RNA duplex located elsewhere in the pre-mRNA for efficient editing. In the case of NEIL1, Gli1 and ZFP14, this cis–active editing enhancer is an RNA duplex formed by a pair of inverted Alu repeat elements in which additional RNA editing events also may occur [28]. Computational scanning of the human transcriptome has revealed that Alu sequences serving as such intramolecular editing enhancers may be a widely utilized feature that facilitates editing efficiency at sites contained within non-optimal secondary structures [16,28]. These editing enhancers can serve as recruiting elements for ADAR proteins, thereby increasing the local concentration of ADAR activity and increasing the likelihood of editing elsewhere in the transcript.

Can Alu editing regulate translation?

Messenger RNAs with hyper-edited regions within the 3’-UTR, formed by Alu inverted repeats, have been shown to be selectively retained within the nucleus and thereby translationally repressed [29]. However, recent studies have indicated that edited transcripts are not only exported to the cytoplasm, but also present on polysomes [29,30]. Moreover, high-throughput analyses of nuclear and cytoplasmic RNA populations show no evidence for editing-dependent subcellular localization [27]. Alu inverted repeats within the 3’-UTR serve as a binding site for a number of RNA binding proteins, including ADARs, p53NRB and Stau1. While p53NRB promotes nuclear retention and association with nuclear paraspeckles, Stau1 promotes nuclear export and translation [31]. These factors compete for binding to dsRNA regions in regulating export and translation of transcripts, but it is increasingly clear that such regulation may overlap with, but is not dependent upon, RNA editing [31].

Translational repression via the microRNA (miRNA) pathway relies upon complementary base pairing predominantly between the seed region at the 5’-end of the miRNA and a miRNA response element generally located within the 3’-UTR of the mRNA. While Alu elements have been shown to contain potential targets for highly conserved miRNAs [32,33], recent studies have suggested that miRNA targets within Alu sequences are significantly less effective at repressing gene expression than mRNAs that have the same miRNA targets outside Alu elements [34]. Several cellular mechanisms have been proposed to explain how potential miRNA sites within Alus are prevented from being recognized effectively by the miRNA machinery. Although untested, the hypothesis that miRNA:mRNA complementarity in Alu duplexes can be disrupted by RNA editing represents an interesting model by which A-to-I conversion might serve to dynamically modulate miRNA-mediated translational repression (Figure 1D).

Will evolution guide Alu editing?

To our knowledge, most cases of previously identified Alu editing have not been shown to influence gene expression or organismal fitness. The overwhelming number of Alu repeats in the primate genome result in numerous transcripts with inverted Alu elements that are readily bound by ADAR enzymes and promiscuously edited in a manner lacking obvious tissue-specificity or site-selectivity. Editing within these Alu sequences, most often occurring at low-levels in non-coding regions, leaves a majority of transcripts and encoded protein products unaffected. This situation offers no immediate selective disadvantage and thereby would permit continued wide-spread occurrence of this RNA modification. Such an evolutionarily neutral phenomenon also lacks an obvious selective advantage, thus allowing evolutionary divergence of Alu sequences and an ensuing loss of A-to-I conversion within Alu-dependent inverted repeats. While evolutionary pressure(s) could select for site-specific modifications within Alu elements, modulating the ratio of edited/non-edited transcripts represents an additional cellular strategy for adaptive evolution.

CONCLUSIONS

The most recent work toward developing a comprehensive database of ADAR-catalyzed A-to-I editing events predicted over 100,000,000 sites within Alu elements of the human transcriptome [21]. We anticipate that the vast majority of these identified Alu editing sites are functionally irrelevant due to the primate-specific nature of these modifications, lack of conservation between closely-related primate species and the low-level of editing observed at most sites [17,21]. Such widespread editing of Alu sequences simply reflects the extensive insertion of inverted Alu repeat sequences in the human genome, the broad expression and promiscuous activity of ADAR proteins, as well as the heightened sensitivity of ultra-high-throughput sequencing strategies that allows quantification of base alterations near the level of biological noise. While examples of functionally significant Alu-editing events have been identified, the vast majority of these modifications offer no obvious selective advantage, yet they still may provide a mechanism for enhancing genetic plasticity for adaptive evolution.

Defining the functional role(s) of individual or combinations of editing sites within Alu elements represents a considerable challenge, particularly given the recent expansion of the Alu editome [21]. Historically, investigators have examined the functional relevance of specific A-to-I editing events by manipulating editing at desired sites and measuring cellular or physiological consequences using biological models ranging from heterologous expression systems to genetically-modified mice. However, manipulating such wide-spread editing is an arduous task since selecting sites or regions upon which to focus seems arbitrary given the wide field of sites from which to choose. Perhaps a better strategy might involve the identification of specific cell subpopulations or disease states where altered or dysregulated patterns of Alu modification may serve as a starting point to define functional role(s) for Alu editing in future studies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health through the Vanderbilt University Silvio O. Conte Center for Neuroscience Research [Grant P50 MH096972] and the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health [Grant R21 MH77942].

REFERENCES

- 1.Ule J. Alu elements: at the crossroads between disease and evolution. Biochemical Society transactions. 2013;41:1532–1535. doi: 10.1042/BST20130157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ade C, Roy-Engel AM, Deininger PL. Alu elements: an intrinsic source of human genome instability. Current opinion in virology. 2013;3:639–645. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmitz J. SINEs as driving forces in genome evolution. Genome dynamics. 2012;7:92–107. doi: 10.1159/000337117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pullirsch D, Jantsch MF. Proteome diversification by adenosine to inosine RNA editing. RNA biology. 2010;7:205–212. doi: 10.4161/rna.7.2.11286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wahlstedt H, Ohman M. Site-selective versus promiscuous A-to-I editing. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews RNA. 2011;2:761–771. doi: 10.1002/wrna.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slotkin W, Nishikura K. Adenosine-to-inosine RNA editing and human disease. Genome medicine. 2013;5:105. doi: 10.1186/gm508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng Y, Sansam CL, Singh M, Emeson RB. Altered RNA editing in mice lacking ADAR2 autoregulation. Molecular and cellular biology. 2006;26:480–488. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.2.480-488.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandal AK, Pandey R, Jha V, Mukerji M. Transcriptome-wide expansion of non-coding regulatory switches: evidence from co-occurrence of Alu exonization, antisense and editing. Nucleic acids research. 2013;41:2121–2137. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lev-Maor G, Sorek R, Levanon EY, Paz N, et al. RNA-editing-mediated exon evolution. Genome biology. 2007;8:R29. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-2-r29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moller-Krull M, Zemann A, Roos C, Brosius J, et al. Beyond DNA: RNA editing and steps toward Alu exonization in primates. Journal of molecular biology. 2008;382:601–609. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li JB, Church GM. Deciphering the functions and regulation of brain-enriched A-to-I RNA editing. Nature neuroscience. 2013;16:1518–1522. doi: 10.1038/nn.3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisenberg E, Li JB, Levanon EY. Sequence based identification of RNA editing sites. RNA biology. 2010;7:248–252. doi: 10.4161/rna.7.2.11565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakurai M, Ueda H, Yano T, Okada S, et al. A biochemical landscape of A-to-I RNA editing in the human brain transcriptome. Genome research. 2014;24:522–534. doi: 10.1101/gr.162537.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu H, Urban DJ, Blashka J, McPheeters MT, et al. Quantitative analysis of focused a-to-I RNA editing sites by ultra-high-throughput sequencing in psychiatric disorders. PloS one. 2012;7:e43227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peng Z, Cheng Y, Tan BC, Kang L, et al. Comprehensive analysis of RNA-Seq data reveals extensive RNA editing in a human transcriptome. Nature biotechnology. 2012;30:253–260. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramaswami G, Lin W, Piskol R, Tan MH, et al. Accurate identification of human Alu and non-Alu RNA editing sites. Nature methods. 2012;9:579–581. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bahn JH, Lee JH, Li G, Greer C, et al. Accurate identification of A-to-I RNA editing in human by transcriptome sequencing. Genome research. 2012;22:142–150. doi: 10.1101/gr.124107.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinto Y, Cohen HY, Levanon EY. Mammalian conserved ADAR targets comprise only a small fragment of the human editosome. Genome biology. 2014;15:R5. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-1-r5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramaswami G, Zhang R, Piskol R, Keegan LP, et al. Identifying RNA editing sites using RNA sequencing data alone. Nature methods. 2013;10:128–132. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu S, Xiang JF, Chen T, Chen LL, et al. Prediction of constitutive A-to-I editing sites from human transcriptomes in the absence of genomic sequences. BMC genomics. 2013;14:206. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bazak L, Haviv A, Barak M, Jacob-Hirsch J, et al. A-to-I RNA editing occurs at over a hundred million genomic sites, located in a majority of human genes. Genome research. 2014;24:365–376. doi: 10.1101/gr.164749.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carmi S, Borukhov I, Levanon EY. Identification of widespread ultra-edited human RNAs. PLoS genetics. 2011;7:e1002317. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robertson M. The evolution of gene regulation, the RNA universe, and the vexed questions of artefact and noise. BMC biology. 2010;8:97. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Athanasiadis A, Rich A, Maas S. Widespread A-to-I RNA editing of Alu-containing mRNAs in the human transcriptome. PLoS biology. 2004;2:e391. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saccomanno L, Bass BL. A minor fraction of basic fibroblast growth factor mRNA is deaminated in Xenopus stage VI and matured oocytes. Rna. 1999;5:39–48. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299981335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neeman Y, Levanon EY, Jantsch MF, Eisenberg E. RNA editing level in the mouse is determined by the genomic repeat repertoire. Rna. 2006;12:1802–1809. doi: 10.1261/rna.165106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen L. Characterization and comparison of human nuclear and cytosolic editomes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:E2741–E2747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218884110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daniel C, Silberberg G, Behm M, Ohman M. Alu elements shape the primate transcriptome by cis-regulation of RNA editing. Genome biology. 2014;15:R28. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-2-r28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen LL, Carmichael GG. Nuclear Editing of mRNA 3'-UTRs. Current topics in microbiology and immunology. 2012;353:111–121. doi: 10.1007/82_2011_149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Capshew CR, Dusenbury KL, Hundley HA. Inverted Alu dsRNA structures do not affect localization but can alter translation efficiency of human mRNAs independent of RNA editing. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40:8637–8645. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elbarbary RA, Li W, Tian B, Maquat LE. STAU1 binding 3' UTR IRAlus complements nuclear retention to protect cells from PKR-mediated translational shutdown. Genes & development. 2013;27:1495–1510. doi: 10.1101/gad.220962.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lehnert S, Van Loo P, Thilakarathne PJ, Marynen P, et al. Evidence for co-evolution between human microRNAs and Alu-repeats. PloS one. 2009;4:e4456. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smalheiser NR, Torvik VI. Alu elements within human mRNAs are probable microRNA targets. Trends in genetics : TIG. 2006;22:532–536. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoffman Y, Dahary D, Bublik DR, Oren M, et al. The majority of endogenous microRNA targets within Alu elements avoid the microRNA machinery. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:894–902. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]