Abstract

Advances in stable isotope approaches, primarily the use of deuterium oxide (2H2O), allow for long-term measurements of protein synthesis, as well as the contribution of individual proteins to tissue measured protein synthesis rates. Here, we determined the influence of individual protein synthetic rates, individual protein content, and time of isotopic labeling on the measured synthesis rate of skeletal muscle proteins. To this end, we developed a mathematical model, applied the model to an established data set collected in vivo, and, to experimentally test the impact of different isotopic labeling periods, used 2H2O to measure protein synthesis in cultured myotubes over periods of 2, 4, and 7 days. We first demonstrated the influence of both relative protein content and individual protein synthesis rates on measured synthesis rates over time. When expanded to include 286 individual proteins, the model closely approximated protein synthetic rates measured in vivo. The model revealed a 29% difference in measured synthesis rates from the slowest period of measurement (20 min) to the longest period of measurement (6 wk). In support of these findings, culturing of C2C12 myotubes with isotopic labeling periods of 2, 4, or 7 days revealed up to a doubling of the measured synthesis rate in the shorter labeling period compared with the longer period of labeling. From our model, we conclude that a 4-wk period of labeling is ideal for considering all proteins in a mixed-tissue fraction, while minimizing the slowing effect of fully turned-over proteins. In addition, we advocate that careful consideration must be paid to the period of isotopic labeling when comparing mixed protein synthetic rates between studies.

Keywords: protein synthesis, deuterium oxide, modeling, stable isotope

skeletal muscle protein turnover is a highly regulated dynamic process. Maintaining protein homeostasis is essential for proper cellular function (1) and responding to various stresses, including exercise (21, 24), while dysregulation of protein turnover may contribute to the progression of various chronic diseases (1). The measurement of protein synthetic rates offers additional insights that are not necessarily afforded by examining cellular signaling or mRNA (15). However, it is essential that the method used for measuring protein synthesis is applied in an appropriate manner for the question being asked.

Much of the knowledge about the rates of skeletal muscle protein turnover was obtained by the use of stable or radioactive isotopic tracers. Through the 1980's and early 1990's, two methods utilizing stable amino acid isotopes, the flooding dose technique and the primed-continuous infusion technique were commonly used for the majority of studies investigating skeletal muscle protein synthesis. Because of discrepant results between these two methods, there was much discussion about which technique was the correct technique and why one was giving erroneous values (6, 20). The primary focus of these discussions was the measurement of the precursor enrichment. However, a tangential result of the debate was a reexamination of the assumptions and limitations inherent to these tracer techniques (6, 10, 20). One potential pitfall that has been recognized, but not often examined in detail, is that of the labeling time period (6, 7, 23).

Users of the flooding dose technique advocated for this method because of its relatively quick measurement compared with the 4- to 6-h primed continuous infusion, as well as the need for only a single biopsy of the tissue of interest. Indeed, because of this relative speed, a hybrid technique with decreased isotope concentration used as a flooding prime with the normal continuous infusion was recently proposed (8). The shortened measurement period has advantages in that it decreases subject burden and can capture relatively acute changes in protein synthesis. However, as discussed below, there are disadvantages to shortening the time period of the continuous infusion in that it perhaps biases synthetic outcomes of a tissue sample. This concern is apparent when considering tissue protein heterogeneity.

An assumption inherent to traditional protein synthetic measurements is that the protein pool is not heterogeneous, but rather homogeneous and constant over the experimental period (23). In studies of skeletal muscle protein synthesis, a muscle sample or biopsy is first homogenized to prepare the sample for measurement of a synthetic rate. An increasingly popular method is to fractionate the muscle biopsy into subcellular fractions, such as myofibrillar, cytoplasmic, and mitochondrial (4, 16, 17, 22, 26). Within a tissue homogenate or subcellular fraction, there are hundreds to thousands of individual proteins that all have individual synthesis rates. Therefore, the measured enrichment of a mixed protein sample is the weighted average of all of the individual proteins in that sample. At equal protein contents, a protein that turns over faster incorporates label faster than a protein with slower turnover, while at similar synthesis rates a more abundant protein incorporates more label than a less abundant protein. Therefore, regarding the length of time of measurement, as a labeling period decreases, there is a bias toward more rapidly turning over proteins or more abundant proteins since they will have increased label incorporation in a shorter period of time (23).

An alternative to the stable amino acid isotope method has been developed, in part, to circumvent issues related to precursor enrichment (2, 5). This alternative method uses a labeled precursor that has free access to all pools of the body, namely stable isotopically labeled water (2H2O). The 2H2O equilibrates throughout all tissues within 1 h and decays with a half-life of 1 wk (18). Therefore, it is easy to achieve constant body water enrichment over an extended period of time. By this approach, the true precursor enrichment is predicted from isotopic equilibration between the body water pool and a precursor amino acid that has been shown to be stable over the extended period of labeling (5, 7, 18, 21). Since this method maintains a steady enrichment over time, it is possible to make relatively long-term (compared with a flooding dose or primed-constant infusion) measurements of protein synthesis.

Recently, advancements in proteomics and stable isotope analyses have made it possible to measure the synthesis rates of individual proteins (11–13, 19, 24). Most of these methods have used 2H2O (12, 13, 19, 24). Besides the advantage of being able to detect the synthesis of individual proteins, published data using these methods allow one to determine the influence of the synthesis of individual proteins on tissue synthetic rates. The goal of the current project was to determine the influence of individual protein synthetic rates, individual protein content, and time of labeling on the measured skeletal muscle protein synthesis rate. We hypothesized that shorter experimental time, as used with the flooding dose technique and the primed-continuous infusion technique, biases measured protein synthesis rates to be representative of more rapidly synthesized or more abundant proteins. We further hypothesized that the extended period of labeling commonly used in studies with 2H2O more accurately captures the average synthesis rates of all proteins within a skeletal muscle tissue sample. To test these hypotheses, we developed a mathematical model, applied the model to an established data collected in vivo, and collected data in vitro to illustrate the importance of the period of isotopic labeling.

METHODS

Model.

The model was designed to illustrate the effect of both the synthesis rate and protein abundance as contributors to a pooled synthesis rate. Consider a tissue sample comprised of N protein types with respective equilibrium mass fractions F1, . . ., FN. If a tracer is added to the system, that tracer will enrich the newly synthesized protein. We developed a model based on three assumptions. First, we assumed that the tracer reaches an equilibrium enrichment in the body water pool quickly relative to the protein synthesis rate, so that all of the enriched protein is produced after a specific time of tracer introduction. Second, we assumed that all of the protein synthesized after the introduction of the tracer is enriched. The model does not assume that the system is at equilibrium at the time that the tracer is introduced; that is, the total mass of protein may change over time. Letting t = 0 be the time of tracer introduction and denoting by Mj(t), the mass of enriched protein j at time t, these assumptions mean that Mj(0) = 0 for all j = 1, . . ., N, and that the change in Mj(t) after time t = 0 is equal to the synthesis rate of protein j minus the degradation rate of protein j. The synthesis rate for the jth protein is a constant κj (with dimensions of mass per time), whereas the degradation rate djMj is proportional to Mj(t) (where the constant dj has dimensions of inverse time). That is,

| (1) |

The equilibrium value of Mj is that value for which dMj/dt = 0, namely = κj/dj. The fraction Pj(t) = gives the fraction of the equilibrium mass of protein j that is present as labeled protein at time t. Dividing both sides of Eq. 1 by we obtain the scaled equation

| (2) |

Defining a rescaled synthesis rate kj = (with dimensions of inverse time), Eq. 2 becomes

| (3) |

Note from Eq. 3 that the equilibrium value of Pj(t) is = 1; that is, at equilibrium, all of the protein of each type has been enriched. If we denote the total mass of the sample at equilibrium by then the equilibrium mass fractions are Fj = Fj = 1, and the total fraction of the equilibrium mass of protein that is present as enriched protein at time t is

| (4) |

The fractional synthesis rate (FSR) for the experiment is FSR(t) = P(t)/t.

The general solution to Eq. 3 is

| (5) |

The first model assumption implies that Pj(0) = 0, so that

| (6) |

Notice that, as t approaches infinity, Pj(t) approaches the equilibrium value 1. The total fraction of the equilibrium mass of protein present as enriched protein at time t is

| (7) |

Application to in vivo data.

To test the fidelity of the model, we used previously published data of the synthesis rates (supplemental data of Ref. 24) and protein content (supplemental data of Ref. 9) of individual proteins to see if the sum of the individual proteins approximates synthesis rates measured from a skeletal muscle homogenate. The studies selected used young, healthy male and female subjects (n = 8–11). From the two referenced papers, we were able to match synthesis rates and content for 285 proteins that represent a mass fraction of 0.706 (Supplemental Table S1; the online version of this article contains supplemental data). To account for the missing mass fraction we 1) added a 286th protein with a mass fraction of 0.294 with a synthesis rate equal to the average of synthesis rates of the other 285 proteins, and 2) normalized the mass fraction of the 285 proteins to 1.0. Since the results of these adjustments were similar, we used the 286th protein approach so that P(t) = FjPj(t).

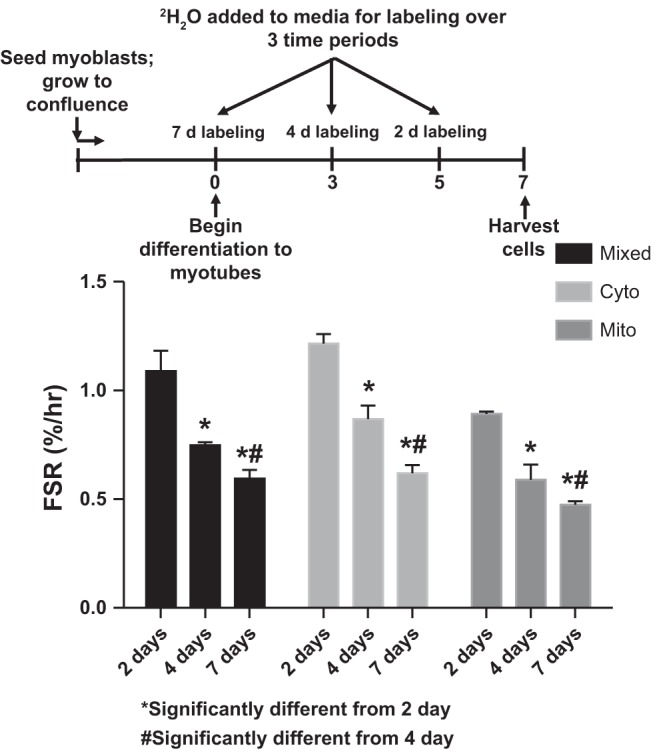

In vitro experiment.

C2C12 mouse myoblasts were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Cells were maintained in growth medium consisting of Dulbecco's modified eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Cells were grown to confluence in a 37°C, 5% CO2 humidified environment. Once cells reached confluence, growth medium was removed, and the cells were rinsed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline. Differentiation medium consisting of Dulbecco's modified eagle medium supplemented with 2% horse serum, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin was added to all cells. For the assessment of protein synthesis, sterile 2H2O was added to differentiation media to a 4% isotopic enrichment. This enriched medium was added to cells either at the onset of differentiation and maintained for the full 7-day differentiation (7 days of isotope exposure), on the 3rd day of differentiation (4 days of isotope exposure), or on the 5th day of differentiation (2 days of isotope exposure). All cells were harvested on day 7 of the experiment. Cells were rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline and scraped in 1 ml of lysis buffer (100 mM KCl, 40 mM Tris·HCl, 10 mM Tris base, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM ATP, pH = 7.5) with phosphatase and protease inhibitors (HALT, Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL).

Cell lysates were separated into three subcellular fractions (cytosolic, mitochondrial, and mixed) for the assessment of fraction-specific protein synthesis. Differential centrifugation was used to isolate these fractions, as previously described (3, 4, 17, 21, 24) with minor modifications. Mitochondria were isolated following a 30-min centrifugation at 10,000 g at 4°C. This pellet was washed in mitochondrial isolation buffer (100 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris·HCl, 10 mM Tris base, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.02 mM ATP, 1.5% wt/vol bovine serum albumin, pH 7.4) centrifuged for 10 min at 8,000 g and washed a second time followed by a 10-min centrifugation at 6,000 g. Proteins were solubilized from each subcellular fraction in 1 M NaOH for 15 min at 50°C, followed by a 24-h acid hydrolysis in 6 M HCl at 120°C.

Hydrolyzed samples were cation exchanged, dried under vacuum, and resuspended in 1 ml of molecular biology grade H2O. Five hundred microliters of these resuspensions were derivatized in 500 μl acetonitrile, 50 μl 1 M K2HPO4 (pH = 11), and 20 μl of pentafluorobenzyl bromide. Samples were then incubated at 100°C for 1 h and then extracted using ethyl acetate. The organic layer was removed and dried by N2, followed by vacuum centrifugation, and samples were reconstituted in 80 μl of ethyl acetate and placed into gas chromatograph vial inserts for analysis. The pentafluorobenzyl-N,N-di(pentafluorobenzyl) derivative of alanine was analyzed on an Agilent 7890A GC coupled to an Agilent 5975C MS, as previously described (3, 4, 17, 21, 24). The newly synthesized fraction (f) of proteins was calculated from the true precursor enrichment (p) using enriched cell culture media analyzed for 2H2O enrichment and adjusted using mass isotopomer distribution analysis. Protein synthesis was calculated as the ratio of deuterium-labeled to unlabeled alanine bound in proteins over the labeling period and expressed as FSR.

To determine deuterium incorporation into culture media, 125 μl of media were placed into the inner well of an o-ring screw on cap and heated overnight. Two microliters of 10 M NaOH and 20 μl of acetone were added to all samples and to 20 μl of 0–20% 2H2O standards and capped immediately. Samples were vortexed at low speed, left at room temperature overnight, and extracted in 200 μl of hexane. The organic layer was transferred through anhydrous Na2SO4 into GC vials and analyzed via electron ionization mode using a DB-17MS column.

Statistical analyses.

In vitro protein synthesis data were analyzed using a two-way (fraction by time) analysis of variance (GraphPad Prism V6.0). Individual differences were determined by Tukey's multiple comparison tests, and significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Modeling.

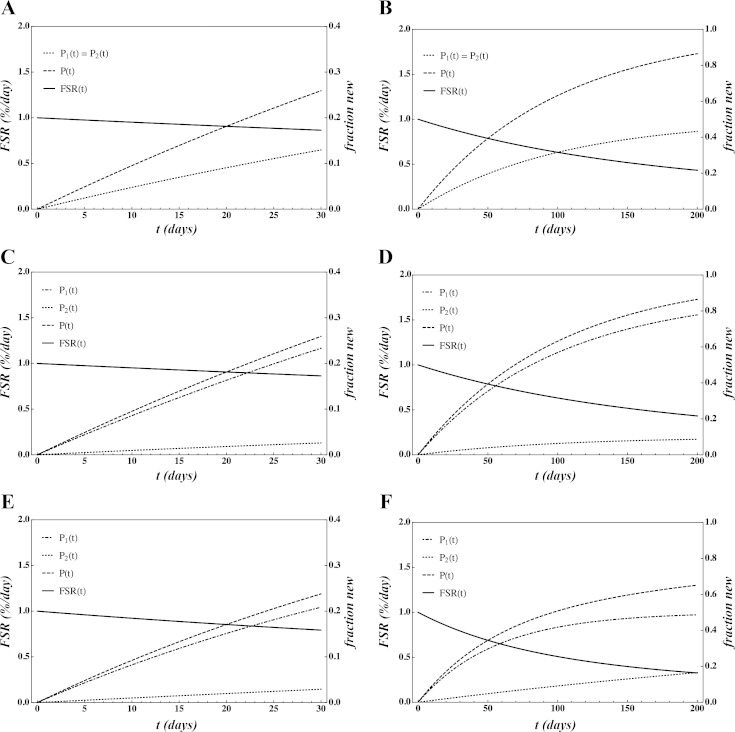

To illustrate the impact of kinetic rates kj and equilibrium mass fractions of a mixed protein sample, we first consider the simple case in which there are exactly two protein types in the sample (N = 2). In Fig. 1 we plot P1(t), P2(t), the total enriched protein P(t) = F1P1(t) + F2P2(t), and the FSR F(t) = P(t)/t. First we consider the case in which the synthesis rates of the two proteins are equal, k1 = k2 = 0.01 (fraction/day), and protein content is equal, F1 = F2 = 0.5 (Fig. 1, A and B), demonstrating equal contribution of both proteins. We then considered the effect of protein content alone in that k1 = k2 = 0.01 (fraction/day), but F1 = 0.9 > F2 = 0.1 (Fig. 1, C and D). In this case, P1 dominates the contribution to overall fraction new initially and throughout the labeling period. Next we consider the effect of synthesis rate alone in which k1 = 0.018 > k2 = 0.002 (fraction/day), and F1 = F2 = 0.5 (Fig. 1, E and F). It is apparent that, in this condition, when protein content is equal, the protein with a higher synthesis rate largely determines overall fraction new and consequently FSR.

Fig. 1.

A simplified two-protein model is presented. To accentuate the effect of time and time to approach 100% new, each condition has a time scale of 30 (A, C, and E) and 200 days (B, D, and F). Presented are conditions where synthetic rates of the two proteins are equal, k1 = k2 = 0.01 (fraction/day) and protein content is equal, F1 = F2 = 0.5 (A and B); synthetic rates are equal, k1 = k2 = 0.01 (fraction/day), but protein contents differ F1 = 0.9 > F2 = 0.1 (C and D); and synthetic rates differ k1 = 0.018 > k2 = 0.002 (fraction/day), but protein contents are equal F1 = F2 = 0.5 (E and F). Dash-dotted line, P1(t); dotted line, P2(t); dashed line, P(t) = F1P1(t) + F2P2(t); solid line, fraction synthesis rate (FSR), F(t) = P(t)/t (%/day). See text for definition of equation terms.

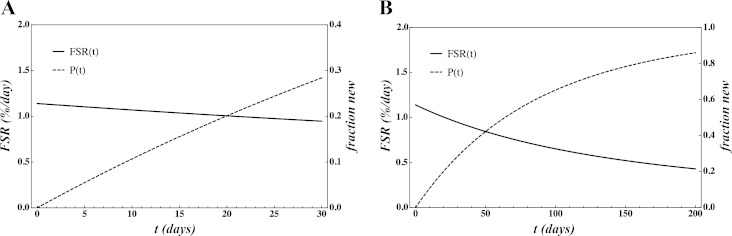

We then expanded our model to include published synthesis rates, and contents of 285 proteins and an averaged 286th protein are plugged into the model (Fig. 2). Of note is that, over time, the rate of protein synthesis (FSR) decreases so that, at time infinity, the line approaches zero. From this line we highlighted commonly used measurement periods of 20 min (0.0125 days), 4 h (0.25 days), 1 day, 1 wk, 2 wk, 4 wk, and 6 wk (Table 1). The values at these time points indicate up to 29.1% difference in measured rates from longest to shortest labeling period.

Fig. 2.

Fraction new P(t) = FjPj(t) and FSR F(t) = P(t)/t over time determined using published values of relative protein content and synthetic rates for 286 proteins. We present a time scale of 30 days (A) and 200 days (B) to accentuate the effect of time and time to approach 100% new. Lines are as defined in Fig. 1 legend.

Table 1.

FSR presented as %/day, %/h, and %different from 6-wk measurement as determined from the modeling of 286 proteins in Fig. 2

| FSR, %/day | FSR, %/h | %Increase over 6-wk value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 min (0.014 day) | 1.1399 | 0.0475 | 29.1 |

| 4 h (0.25 day) | 1.1382 | 0.0474 | 28.8 |

| 24 h (1 day) | 1.1326 | 0.0472 | 28.2 |

| 1 wk (7 days) | 1.0900 | 0.0454 | 23.4 |

| 2 wk (14 days) | 1.0432 | 0.0435 | 18.2 |

| 4 wk (28 days) | 0.9582 | 0.0399 | 8.4 |

| 6 wk (42 days) | 0.8833 | 0.0368 | 0 |

FSR, fractional synthesis rate.

In vitro measurement of protein synthesis.

In the three protein fractions (mixed, cytosolic, and mitochondrial) when the period of isotopic labeling was shorter, the FSR was greater (Fig. 3). The shortest labeling period (2 days) resulted in an FSR that was nearly double those at 4 or 7 days of labeling.

Fig. 3.

Protein synthetic rates of three different protein fractions in C2C12 myotubes over three different labeling periods. As the period of labeling decreases, the measured synthesis rates increase. Cyto, cytosolic; Mito, mitochondrial. Values are means ± SE; n = 3 plates/condition. Significantly different from *2-day measurement and #4-day measurement: P < 0.05.

Effect of change of total protein mass.

We have defined the fractions Pj(t), P(t), and FSR(t) in terms of mass of enriched protein relative to equilibrium masses so that the model is independent of change in total mass after the introduction of tracer to the system (time t = 0). If there is no change in the total mass of protein j after the introduction of tracer (that is, the system is at equilibrium at the start of the experiment), then Pj(t) is the fraction of protein j in the system at time t that is enriched, and P(t) is the total fraction of the protein in the system at time t that is enriched. In this case, P(t) would be determined experimentally by determining the total fraction of protein present that is enriched. If, however, the system is not at equilibrium at the time that tracer is introduced, then the total mass of protein potentially changes after the introduction of tracer, and more care must be taken to calculate Pj(t) and P(t) from experimental measurements. To illustrate the effect of a change in total protein mass, let Nj(t) denote the mass of unenriched protein j at time t, and consider the following experimental measurements. At time t = 0 (the time at which the tracer is introduced to the system), the total mass of protein j is measured. This is Nj(0), since Mj(0) = 0. At a later time te > 0, the masses Mj(te) enriched protein j, and Nj(te) of unenriched protein j are measured.

To calculate FSR, recall the model assumption that, after the introduction of tracer, all protein that is synthesized is enriched, so the change in the mass of unenriched protein is also a result of degradation. That is, dNj/dt = −djNj, so that Nj(t) = Nj(0). If Nj(0) ≠ 0, this yields that

| (8) |

Secondly, we calculate from the differential Eq. 1, the initial condition Mj(0) = 0, and the definition = κj/dj that

| (9) |

Experimental values of Nj(0), Nj(te), and Mj(te) thus allow for the calculation of through Eqs. 8 and 9. If the model assumptions hold, then the calculation (Eq. 9) is independent of the time te at which the measurements are made. The experimentally determined value of Pj(te) is then given by Pj(te) = The experimental value of P(te) is the sum P(te) = Pj(te) and FSR(te) = P(te)/t.

In an experiment, it may be that only the total mass of enriched protein M(te) = Mj(te) and the total mass of unenriched protein N(te) = Nj(te) are determined at some time te. In this case, one may approximate FSR(te) by effectively assuming that there is only one protein type, so that the total mass of enriched protein is M(t) = M1(t), the total mass of unenriched protein is N(t) = N1(t), and similarly P(t) = P1(t).

To illustrate the effect of a change in total mass during the course of an experiment, consider the following measurements: M(0) = M1(0) = 0, N(0) = N1(0) = 0.609 μg, M(4) = M1(4) = 0.73043 μg, and N(4) = N1(4) = 0.222 μg. Note that, in this case, between times t = 0 and t = 4, the total mass of protein in the system has increased by 0.344 μg. From Eq. 8, we calculate that d1 = 0.252. Using that result and Eq. 9, we calculate that M* = = 1.151, so that P(4) = M(4)/M* = 0.635, and FSR(4) = P(4)/4 = 0.159 fraction new per day, or 0.663%/h. As a comparison, we compare the number 0.159 with the value for the FSR that would result from a more straightforward calculation using the fraction of protein present as time t = 4 that is enriched. The result is 1/4 M(4)/M(4) + N(4) = 0.192 fraction new/day or 0.800%/h. The difference between 0.663%/h and 0.800%/h as approximations of the FSR is a consequence of the growth in the total protein content of the system during the course of the experiment. Although only the 0.6625%/h value is calculated consistently with our definition of the FSR in that it makes use of the equilibrium protein mass rather than the current (and potentially changing) protein mass, it too is an approximation, if there are more than one protein type. As we demonstrate in Fig. 2, nonequal synthesis rates for proteins of different types can have a significant impact on the actual value of the FSR.

DISCUSSION

Increasingly 2H2O has been used to measure muscle protein synthesis to circumvent some of the issues associated with the more traditional approaches of labeled amino acid infusion. An issue recognized in the past (6, 7, 23), but not recently addressed in the context of more long-term measurement approaches, is the influence of time of labeling itself on tissue measured synthesis rates. Using a modeling approach and an in vitro experiment, we show the influence of individual protein synthesis rates, protein content, and period of labeling on overall skeletal muscle protein synthesis rates. From these data, we recommend longer periods of labeling, up to 4 wk, to minimize the dominance of rapidly synthesized proteins and those with large content on measured tissue skeletal muscle protein synthetic rates in humans.

Model.

Our first goal was to demonstrate the independent contributions of synthesis rate and protein content of an individual protein to overall synthesis rates in a simplified two-protein model. From this modeling exercise, it is clear that protein content and synthesis rates are equally important in determining mixed protein synthesis rates. In addition, it is clear that those proteins with high content or fast synthesis rates can dominate the overall fraction new in early time periods. From Supplemental Table S1, examples of proteins with high content are myoglobin, creatine kinase, and myosin light chain, whereas examples of rapidly synthesized proteins are apolipoprotein A-1, heat shock protein 90, and vimentin.

In addition to standard proteomic techniques that can determine relative protein content, new techniques using a combined stable isotope and proteomic approach (termed dynamic proteomics or kinetic proteomics) allow the assessment of individual protein synthesis rates (11–13, 19, 24). We took advantage of published values in skeletal muscle of relative protein contents (9) and individual protein synthesis rates (24) in skeletal muscle to see if the same approach used in our simplified two-protein model would predict tissue measured synthesis rates. We had 285 proteins that matched in both data sets, and these 285 proteins summed to a mass fraction of 0.706. We then added an average synthesis value for the remainder of the 0.294 mass fraction. From these data, we had a very close match to tissue measured protein synthetic rates using 2H2O over 4 wk (24) and 6 wk (21). Depending on experimental treatment and protein fraction, our laboratory's previously published synthesis rates ranging from 0.727–1.277%/day (24) and 1.206%/h (21) match well with the predicted 0.9582 (Table 1). Of note, in experiments that have used labeling periods of < 8 days, values for skeletal muscle protein synthesis are slightly higher (≈1.2–2.0%) (25), again supporting that time period of labeling is important. However, the use of a bolus dose of 2H2O vs. continuous provision of 2H2O may also be a factor in the slightly different values.

These data also allowed us to estimate how the sum changes of protein content and synthesis rates can influence overall measured tissue protein synthesis rates over time. From the model, there is a 29.1% difference between a 20-min measurement and 6-wk measurement. It is important to realize that the model does not change the synthesis rate of any individual protein over time, and the decrease in time is the result of the increasing contribution of more slowly synthesized proteins. It appears that the differences from a 20-min measurement and 24-h measurement are relatively minor. However, the commonly used 2- and 4-wk measurements are 10–20% different than the 4-h measurement and more closely approximate the 6-wk measurement.

In vitro data.

To experimentally test how differences in the isotopic labeling period can affect changes in measured synthesis rates, we used 2H2O to measure mixed protein synthesis in C2C12 murine skeletal muscle myotubes over periods of 2, 4, and 7 days. As predicted, the measured synthesis rates of all protein fractions were faster when measured at 2 days compared with 4 or 7 days, and at 4 days compared with 7 days. Differences in synthesis rates between the labeling periods were upwards of double for the shorter period of measurement compared with the longer period of measurement, although this varied by cell fraction. In the absence of synthesis rates of individual proteins, we cannot rule out that the presence of proteins that were 100% new contributed to the observed decrease in synthesis rates at the later time points. However, by labeling over a period of days, rather than weeks, we aimed to minimize the contribution of fully turned-over proteins to overall synthesis rates. Therefore, careful consideration must be made for controlling the period of labeling. Furthermore, as far as we are aware, these are the first data using 2H2O-enriched media for the measurement of synthesis rates in a skeletal muscle cell line. From these data, we see highly accelerated protein synthetic rates in vitro (upwards of 1%/h) compared with in vivo (≈0.05%/h).

Practical recommendations.

How then do we make a practical recommendation from these data? The logical conclusion is to maximize the duration of labeling period (within practical limits) while minimizing the number of individual proteins that are 100% new. The recommendation to use the longest labeling period possible is to account for the increasing contribution of lesser abundant proteins and proteins with slower synthesis rates. The cap on the labeling period is to avoid the gradual accumulation of individual protein types that are fully new, since these will contribute to an overall slowing of measured mixed protein synthesis rate. The fastest protein in Supplemental Table S1, apolipoprotein A-I (accession no. P02647) has a synthesis rate of 0.1553%/h, which means it is 100% new in ∼27 days. Therefore, in vivo, we recommend labeling periods for skeletal muscle of 4 wk. By measuring over 4 wk, slower and lower content proteins are accounted for, while the slowing effect of fully turned-over proteins are minimized.

Conclusion and perspective.

We have advocated the use of 2H2O for the measurement of protein synthesis (14, 15), primarily because of the great advantage of making measurements during free-living conditions that incorporate all physiological stimuli. An additional advantage verified by the model and experiments presented here is that the prolonged period of labeling allows consideration of the increasing contribution of all proteins, including those with less abundance and slower turnover, to the measured mixed protein synthetic rate. It is not our purpose to discount methods that use shorter labeling periods, as these still can be advantageous in experimental designs where acute measurements are warranted. However, we are strongly in favor of prolonged periods of measurement when drawing conclusions about the overall effects of a treatment or intervention. From the data presented here, we recommend a 4-wk period of measurement to assess in vivo skeletal muscle mixed protein synthetic rates in human subjects.

GRANTS

This project was supported by National Institute on Aging Grant R01-AG-042569.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: B.F.M., P.D.S., and K.L.H. conception and design of research; B.F.M., C.A.W., F.F.P., P.D.S., and K.L.H. analyzed data; B.F.M., C.A.W., and K.L.H. interpreted results of experiments; B.F.M., P.D.S., and K.L.H. prepared figures; B.F.M. drafted manuscript; B.F.M., C.A.W., P.D.S., and K.L.H. edited and revised manuscript; B.F.M., C.A.W., F.F.P., P.D.S., and K.L.H. approved final version of manuscript; C.A.W., F.F.P., and P.D.S. performed experiments.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Balch WE, Morimoto RI, Dillin A, Kelly JW. Adapting proteostasis for disease intervention. Science 319: 916–919, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Busch R, Kim YK, Neese RA, Schade-Serin V, Collins M, Awada M, Gardner JL, Beysen C, Marino ME, Misell LM, Hellerstein MK. Measurement of protein turnover rates by heavy water labeling of nonessential amino acids. Biochim Biophys Acta 1760: 730–744, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drake JC, Bruns DR, Peelor FF, Biela LM, Miller RA, Hamilton KL, Miller BF. Long-lived crowded-litter mice have an age-dependent increase in protein synthesis to DNA synthesis ratio and mTORC1 substrate phosphorylation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 307: E813–E821, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drake JC, Peelor FF, Biela LM, Watkins MK, Miller RA, Hamilton KL, Miller BF. Assessment of mitochondrial biogenesis and mTORC1 signaling during chronic rapamycin feeding in male and female mice. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 68: 1493–1501, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dufner DA, Bederman IR, Brunengraber DZ, Rachdaoui N, Ismail-Beigi F, Siegfried BA, Kimball SR, Previs SF. Using 2H2O to study the influence of feeding on protein synthesis: effect of isotope equilibration in vivo vs. in cell culture. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 288: E1277–E1283, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garlick PJ, McNurlan MA, Essén P, Wernerman J. Measurement of tissue protein synthesis rates in vivo: a critical analysis of contrasting methods. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 266: E287–E297, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gasier HG, Fluckey JD, Previs SF. The application of 2H2O to measure skeletal muscle protein synthesis. Nutr Metab (Lond) 7: 31, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holm L, Reitelseder S, Dideriksen K, Nielsen RH, Bülow J, Kjaer M. The single-biopsy approach in determining protein synthesis in human slow-turning-over tissue: use of flood-primed, continuous infusion of amino acid tracers. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 306: E1330–E1339, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hwang H, Bowen BP, Lefort N, Flynn CR, De Filippis EA, Roberts C, Smoke CC, Meyer C, Højlund K, Yi Z, Mandarino LJ. Proteomics analysis of human skeletal muscle reveals novel abnormalities in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 59: 33–42, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jahoor F, Zhang XJ, Baba H, Sakurai Y, Wolfe RR. Comparison of constant infusion and flooding dose techniques to measure muscle protein synthesis rate in dogs. J Nutr 122: 878–887, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaleel A, Short KR, Asmann YW, Klaus KA, Morse DM, Ford GC, Nair KS. In vivo measurement of synthesis rate of individual skeletal muscle mitochondrial proteins. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 295: E1255–E1268, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasumov T, Dabkowski ER, Shekar KC, Li L, Ribeiro RF, Walsh K, Previs SF, Sadygov RG, Willard B, Stanley WC. Assessment of cardiac proteome dynamics with heavy water: slower protein synthesis rates in interfibrillar than subsarcolemmal mitochondria. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 304: H1201–H1214, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lam MPY, Wang D, Lau E, Liem DA, Kim AK, Ng DCM, Liang X, Bleakley BJ, Liu C, Tabaraki JD, Cadeiras M, Wang Y, Deng MC, Ping P. Protein kinetic signatures of the remodeling heart following isoproterenol stimulation. J Clin Invest 124: 1734–1744, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller BF, Drake JC, Naylor B, Price JC, Hamilton KL. The measurement of protein synthesis for assessing proteostasis in studies of slowed aging. Ageing Res Rev 18: 106–111, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller BF, Hamilton KL. A perspective on the determination of mitochondrial biogenesis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 302: E496–E499, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller BF, Olesen JL, Hansen M, Døssing S, Crameri RM, Welling RJ, Langberg H, Flyvbjerg A, Kjaer M, Babraj JA, Smith K, Rennie MJ. Coordinated collagen and muscle protein synthesis in human patella tendon and quadriceps muscle after exercise. J Physiol 567: 1021–1033, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller BF, Robinson MM, Bruss MD, Hellerstein M, Hamilton KL. A comprehensive assessment of mitochondrial protein synthesis and cellular proliferation with age and caloric restriction. Aging Cell 11: 150–161, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neese RA, Misell LM, Turner S, Chu A, Kim J, Cesar D, Hoh R, Antelo F, Strawford A, McCune JM, Christiansen M, Hellerstein MK. Measurement in vivo of proliferation rates of slow turnover cells by 2H2O labeling of the deoxyribose moiety of DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99: 15345–15350, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Price JC, Holmes WE, Li KW, Floreani NA, Neese RA, Turner SM, Hellerstein MK. Measurement of human plasma proteome dynamics with 2H2O and liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem 420: 73–83, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rennie MJ, Smith K, Watt PW. Measurement of human tissue protein synthesis: an optimal approach. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 266: E298–E307, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson MM, Turner SM, Hellerstein MK, Hamilton KL, Miller BF. Long-term synthesis rates of skeletal muscle DNA and protein are higher during aerobic training in older humans than in sedentary young subjects but are not altered by protein supplementation. FASEB J 25: 3240–3249, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rooyackers OE, Adey DB, Ades PA, Nair KS. Effect of age on in vivo rates of mitochondrial protein synthesis in human skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93: 15364–15369, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samarel AM. In vivo measurements of protein turnover during muscle growth and atrophy. FASEB J 5: 2020–2028, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scalzo RL, Peltonen GL, Binns SE, Shankaran M, Giordano GR, Hartley DA, Klochak AL, Lonac MC, Paris HLR, Szallar SE, Wood LM, Peelor FF, Holmes WE, Hellerstein MK, Bell C, Hamilton KL, Miller BF. Greater muscle protein synthesis and mitochondrial biogenesis in males compared with females during sprint interval training. FASEB J 28: 2705–2714, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilkinson DJ, Franchi MV, Brook MS, Narici MV, Williams JP, Mitchell WK, Szewczyk NJ, Greenhaff PL, Atherton PJ, Smith K. A validation of the application of D2O stable isotope tracer techniques for monitoring day-to-day changes in muscle protein subfraction synthesis in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 306: E571–E579, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilkinson SB, Phillips SM, Atherton PJ, Patel R, Yarasheski KE, Tarnopolsky MA, Rennie MJ. Differential effects of resistance and endurance exercise in the fed state on signalling molecule phosphorylation and protein synthesis in human muscle. J Physiol 586: 3701–3717, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.