Abstract

Skeletal muscle contractile performance is governed by the properties of its constituent fibers, which are, in turn, determined by the molecular interactions of the myofilament proteins. To define the molecular determinants of contractile function in humans, we measured myofilament mechanics during maximal Ca2+-activated and passive isometric conditions in single muscle fibers with homogenous (I and IIA) and mixed (I/IIA and IIA/X) myosin heavy chain (MHC) isoforms from healthy, young adult male (n = 5) and female (n = 7) volunteers. Fibers containing only MHC II isoforms (IIA and IIA/X) produced higher maximal Ca2+-activated forces over the range of cross-sectional areas (CSAs) examined than MHC I fibers, resulting in higher (24–42%) specific forces. The number and/or stiffness of the strongly bound myosin-actin cross bridges increased in the higher force-producing MHC II isoforms and, in all isoforms, better predicted force than CSA. In men and women, cross-bridge kinetics, in terms of myosin attachment time and rate of myosin force production, were independent of CSA, although women had faster (7–15%) kinetics. The relative proportion of cross bridges and/or their stiffness was reduced as fiber size increased, causing a decline in specific force. Results from our examination of molecular mechanisms across the range of physiological CSAs explain the variation in specific force among the different fiber types in human skeletal muscle, which may have relevance to understanding how various physiological and pathophysiological conditions modulate single-fiber and whole muscle contractility.

Keywords: muscle fiber, mechanical properties, cross bridge

physical performance is largely dependent on skeletal muscle power output (55), which is the product of the muscle's force and velocity. Force production and contractile velocity in single fibers, which scale to the tissue and whole body levels (56), are determined largely by the molecular-level interactions of the myofilament contractile proteins. Because of its impact on the ATPase kinetic and mechanical properties, the myosin heavy chain (MHC) protein plays a prominent role in setting single-fiber contractile properties. In adult human skeletal muscle fibers, the ATPase rate hierarchy of the MHC isoforms [I < IIA < IIX (22, 59, 62)] dictates the contraction velocity and power output of each isoform (2, 3, 22, 31). Expressed and purified myosin heads from human MHC isoforms show that velocity differences are due to alterations in the time myosin spends bound to actin, or myosin attachment time (ton), with contractile velocity increasing (I < IIA < IIX) as ton becomes shorter (I > IIA > IIX), primarily as a result of quicker release of ADP (1). Hybrid fibers, which contain a mixture of MHC isoforms (I/IIA, IIA/X, and I/IIA/X), tend to have contractile properties between the pure MHC isoforms (2, 3, 22, 31).

In humans, most skeletal muscles contain a mixture of fiber types: postural and endurance muscles contain more MHC I fibers, while muscles responsible for rapid, high-power, short-duration movements consist of more MHC IIA and IIX fibers. Notably, fiber type composition can be altered via activity level (11, 64) and disease (17, 32). Thus the fiber type composition of the whole muscle serves as a means of setting and adapting contractile performance (21, 64). In addition to the effects of fiber type admixture in determining the contractile character of skeletal muscle, there is substantial variability in function within individual muscle fiber types (18, 21). Understanding the molecular-level interactions, such as myosin-actin cross-bridge kinetics, of the MHC isoforms and their role in single-fiber performance will aid in determining their effect on whole muscle properties.

Although the effect of MHC isoforms on average single-fiber contractile velocity has been well defined, their influence on force production is ambiguous. Isometric specific force, or force per cross-sectional area (CSA), has been found to be higher in MHC IIA than I fibers (2, 8, 10, 11, 14, 26, 29, 50, 51, 70) or similar between the two isoforms (22, 23, 31, 59, 62). These studies present a single average isometric specific force value for the MHC isoforms; however, force generation may be altered with fiber size, as isometric specific force is generally thought to decrease as fibers become larger (13, 18). A hypothesis for the relationship between force production and fiber size is that radial diffusion of small molecules is slower than longitudinal diffusion (28), meaning that fibers with larger CSAs may accumulate more small molecules, such as ADP or phosphate (Pi), which, in turn, modulate cross-bridge mechanics and kinetics in ways that reduce isometric specific force production in larger fibers (13, 18, 60). Because of this possible size-dependent effect on cross-bridge mechanics and kinetics, evaluation of the underlying determinants of fiber specific force should consider the modulation of these factors throughout a range of CSAs. However, to our knowledge, myofilament mechanical properties, including specific steps of the cross-bridge cycle, have not been examined across a range of fiber sizes.

The aim of this study was to examine the role of myofilament mechanical properties, including myosin-actin cross-bridge kinetics, across a range of fiber CSAs in determining the single-fiber isometric specific force of the different MHC isoform-containing fibers found in human skeletal muscle. Skeletal muscle tissue was obtained from the vastus lateralis of 12 healthy, young (21- to 35-yr-old), sedentary individuals. Standardization of the muscle tissue biopsied and volunteer characteristics are important considerations, as single-fiber properties can be affected by the muscle type examined (37), as well as the activity level (6, 11, 12), age (11, 12, 14, 41), and health status (42, 66) of the volunteer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical approval.

Written informed consent was obtained from each volunteer prior to medical screening to rule out conditions that may have precluded their participation. The protocol was submitted to and approved by the Committees on Human Research at the University of Vermont.

Participants.

Twelve young (21- to 35-yr-old) participants (5 men and 7 women) were recruited for, enrolled in, and completed the study. Volunteers reported minimal habitual physical activity (they participated in no structured exercise program, and walking was their primary exercise), which was verified using accelerometry measurements. Volunteers had no symptoms or signs of heart disease, hypertension, or diabetes (fasting blood glucose >112 mg/dl); resting electrocardiogram, electrocardiogram response to an exercise stress test, thyroid function, and blood cell counts and blood biochemistry values were normal. Volunteers were excluded if they were currently participating in a weight-loss or exercise-training program or had participated in such a program in the past year, or if they had a history (within 1 yr) of smoking, unintentional weight loss of >2.5 kg during the last 3 mo, a body mass index (BMI) >30 kg/m2, or a hospitalization of >3 days in the past 5 yr. Participants taking oral corticosteroids or any medication that might influence skeletal muscle structure or function were excluded. Women taking oral contraceptives (n = 4) were included. Data on clinical characteristics, whole muscle function, and single-fiber protein content and function in MHC I and IIA fibers from these volunteers have been compared with data from older adults in a previous study for the purpose of interrogating age-related changes in cellular and molecular muscle function (5, 41).

Experimental protocol.

Eligibility was determined during screening visits, which included whole muscle strength testing, as well as resting and exercising electrocardiograms. At least 1 wk later, muscle tissue was obtained via percutaneous biopsy (Bergstrom needle, 5-mm outer diameter) of the vastus lateralis under lidocaine anesthesia, and body mass was measured (fasted) on a digital scale (ScaleTronix, Wheaton, IL).

Accelerometry.

Free-living physical activity energy expenditure was estimated using a single-plane (vertical) accelerometer (Caltrac, Muscle Dynamics Fitness Network, Torrance, CA). Each patient's age, weight, height, and sex were programmed into the accelerometer to allow calculation of caloric cost of physical activity. Volunteers were instructed to wear the accelerometer on their waistline during waking hours for as many days as possible over a 10-day period and to record the number of calories at the start and end of each day.

Solutions.

Dissection solution contained (in mM) 20 N,N-bis(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid, 5 EGTA, 5 MgATP, 1 free Mg2+, 1 dithiothreitol, and 0.25 Pi, with an ionic strength of 175 meq (pH 7.0). At pCa 8, skinning solution contained (in mM) 170 potassium propionate, 10 imidazole, 5 EGTA, 2.5 MgCl2, 2.5 ATP-Na2H2, 0.05 leupeptin, and 0.05 antipain (pH 7.0). Storage solution was identical to skinning solution, but with 1 mM sodium azide and without leupeptin and antipain. The remaining solutions, which were used for single-fiber mechanical measurements, contained 0.25 mM Pi for 15°C experiments and 5 mM Pi for 25°C experiments. Relaxing solution was identical to dissecting solution, with 15 mM creatine phosphate and 300 U/ml creatine phosphokinase. Preactivating solution was identical to relaxing solution, except at an EGTA concentration of 0.5 mM. Activating solution was the same as relaxing solution, except at pCa 4.5. All solutions used for mechanical experiments were adjusted to proper ionic strength (175 meq) using sodium methane sulfate. Solution calculations were performed using equations and stability constants described elsewhere (42).

Muscle tissue processing.

Approximately two-thirds of the biopsy material was placed immediately into cold (4°C) dissecting solution. Muscle fibers were dissected from this material into bundles and tied to glass rods at 4°C and then placed in skinning solution for 24 h at 4°C. After they were skinned, the fibers were placed in storage solution with increasing concentration of glycerol [10% (vol/vol) for 2 h, 25% (vol/vol) for 2 h, and 50% (vol/vol)] and then stored at −20°C until isolation of single fibers for mechanical measurements (within 4 wk). Remaining tissue was either frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C or prepared for electron microscopy or immunohistochemical assessment, the results of which are presented elsewhere (5).

Single-fiber mechanical measurements.

Segments (∼2.5–3.0 mm) of single fibers were isolated from muscle bundles, and their ends were fixed with glutaraldehyde, as described elsewhere (42). Aluminum T clips were placed on the fixed regions, and the fiber was mounted in relaxing solution onto hooks for top and side diameter measurements at three positions along the length of the fiber using a filar eyepiece micrometer (Lasico, Los Angeles, CA) and a right-angled, mirrored prism for calculation of average CSA. The fiber was then incubated in dissecting solution containing 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 for 30 min at 4°C to ensure adequate skinning of the sarcolemma and sarcoplasmic reticulum.

The experimental apparatus specifications (42) and details of mechanical assessment at 15°C and 0.25 mM Pi (42, 43) and 25°C and 5 mM Pi (42) are described elsewhere. Briefly, the T-clipped fiber ends were attached to a piezoelectric motor (Physik Instrumente, Auburn, MA) and a strain gauge (SensorNor, Horten, Norway) in relaxing solution at 15°C, and sarcomere length was set to 2.65 μm (IonOptix, Milton, MA). Isometric specific force was measured under maximal Ca2+-activated conditions (pCa 4.5) at 15°C and 0.25 mM Pi to correspond with previous studies in human skeletal muscle fibers [temperature range commonly 12–15°C (10, 11, 14, 29)]. In a subset of fibers, isometric specific force was measured and sinusoidal analysis at pCa 4.5 was subsequently performed at 25°C and 5 mM Pi, which corresponds with resting Pi levels in human skeletal muscle (52). At both temperatures, the fibers were transferred to preactivating solution for 30 s before activation to improve fiber stability by allowing for the rapid influx of Ca2+ into the fiber (31, 44). In a different set of fibers, isometric specific force and sinusoidal analysis at 25°C were measured at a sarcomere length of 2.65 μm using relaxing solution with 40 mM 2,3-butanedione monoxime (BDM), which places the myosin head in a weakly bound state (39) and, thus, provides a measure primarily of the properties of the underlying myofilament lattice. Small-amplitude sinusoidal length changes (0.05% for maximal Ca2+-activated and 0.25% for BDM) were applied to the fiber at 48–50 frequencies (0.25–200 Hz for maximal Ca2+-activated and 0.125–200 Hz for BDM) while the force response was measured. After mechanical measurements, single fibers were placed in gel loading buffer, heated for 2 min at 65°C, and stored at −80°C until determination of MHC isoform composition by SDS-PAGE, as described elsewhere (42). Pure (I and IIA) and mixed (I/IIA and IIA/X) MHC fiber types were compared, as the number of IIX and I/IIA/X fibers was insufficient to permit statistical analysis (<2% of all fibers combined).

To relate sinusoidal analysis with specific steps in the cross-bridge cycle, the complex modulus (plotted as viscous vs. elastic modulus) at maximal Ca2+ activation was characterized by the following mathematical expression, as described in detail elsewhere (42): y(ω) = A(iω/α)k − Biω/(2πb + iω) + Ciω/(2πc + iω), where ω = 2πf (in s−1), A, B, and C are magnitudes (in kN/m2), 2πb and 2πc are characteristic rates (in s−1), i = −11/2, α = 1 s−1, and k is a unitless exponent. The A process (characterized by parameters A and k) describes a linear relationship between the viscous and elastic moduli that has no kinetic or enzymatic dependence (46, 48) and reflects the viscoelastic properties of the passive structural elements of the fiber across the oscillation frequency range. Under Ca2+-activated conditions, where myosin-actin cross bridges are formed, the A process represents the underlying stiffness of the lattice structure and the attached myosin heads in series (46). The parameter A indicates the magnitude of a viscoelastic modulus, and k describes the degree to which measured viscoelastic mechanics represent purely elastic (k = 0) vs. purely viscous (k = 1) mechanical responses. The B and C process magnitudes (B and C) are proportional to the number of myosin heads strongly bound to actin and the cross-bridge stiffness (27, 47). The frequency portion of the B process (2πb) has been interpreted as the apparent (observed) rate of myosin force production or, in other words, the rate of myosin transition between the weakly and strongly bound states (72). The reciprocal of the frequency portion of the C process, or (2πc)−1, represents the average myosin attachment time to actin, ton (47).

Statistics.

Values are means ± SE, and differences were considered significant at P ≤ 0.05, unless otherwise noted. An analysis of variance was used to evaluate differences between the variable means (e.g., isometric specific force) across different fiber types. As there are multiple observations of these variables within the same individual, a linear mixed model was used, including a random effect to account for clustering of observations within individuals, as previously described (6). If a fiber type effect was noted, post hoc contrasts were performed to identify pair-wise differences. Relationships between variables were determined using Pearson's correlation coefficients (r). An analysis of covariance was used to fit separate slopes and intercepts to variables plotted vs. CSA by using fiber type as the fixed factor and CSA as the covariate and examining pair-wise comparisons of slopes and intercepts between fiber types. If slopes were not significantly different, a model that fits a common slope with separate intercepts for each fiber type was used, which was considered significant at P ≤ 0.01 to be conservative, and only pair-wise comparisons of intercepts between fiber types were examined. y-Intercepts and slopes are used to statistically compare and characterize the regression lines, and these data should not be used to infer the characteristics of these relationships beyond the boundaries of our observations. In addition, to examine potential sex differences within each fiber type, an analysis of covariance was used to fit separate slopes and intercepts to variables plotted vs. CSA, with sex used as the fixed factor and CSA as the covariate. If slopes were not significantly different, a model that fits a common slope with separate intercepts for each sex was used, which was considered significant at P ≤ 0.01 to be conservative, and only comparisons of intercepts between the sexes were examined. Estimates of slopes and intercepts were also tested for significance from zero. For the elastic and viscous moduli data, a repeated-measures analysis was used, with frequency as a repeated measure and pair-wise comparisons performed between MHC I and IIA fiber types at each frequency. Differences between men and women were determined using two-sample Student's t-tests for clinical characteristics. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics (version 20.0, IBM, Armonk, NY) and SAS (version 9.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Participants.

Physical characteristics for the entire volunteer group and separated by sex are shown in Table 1. No differences were found, except for lower body mass in women than men. Daily physical activity level was measured by accelerometry over an average of 8.7 ± 0.4 (range 6–10) days.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and activity levels of young volunteers

| Average | Range | Male | Female | P Value for Sex Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 12 | 12 | 5 | 7 | |

| Age, yr | 24.2 ± 1.0 | 21.1–31.9 | 25.0 ± 1.4 | 23.6 ± 1.5 | 0.99 |

| Height, cm | 172 ± 3 | 158–186 | 181 ± 2 | 166 ± 3 | 0.12 |

| Body mass, kg | 65.9 ± 3.6 | 46.0–81.5 | 72.8 ± 3.0 | 60.9 ± 5.1 | 0.03* |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.1 ± 0.9 | 17.4–27.5 | 22.4 ± 1.4 | 21.9 ± 1.3 | 0.92 |

| Physical activity level, kcal/day | 421 ± 32 | 234–605 | 385 ± 55 | 448 ± 38 | 0.43 |

Values are means ± SE.

BMI, body mass index.

Statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Singe-fiber properties at 15°C and 0.25 mM Pi.

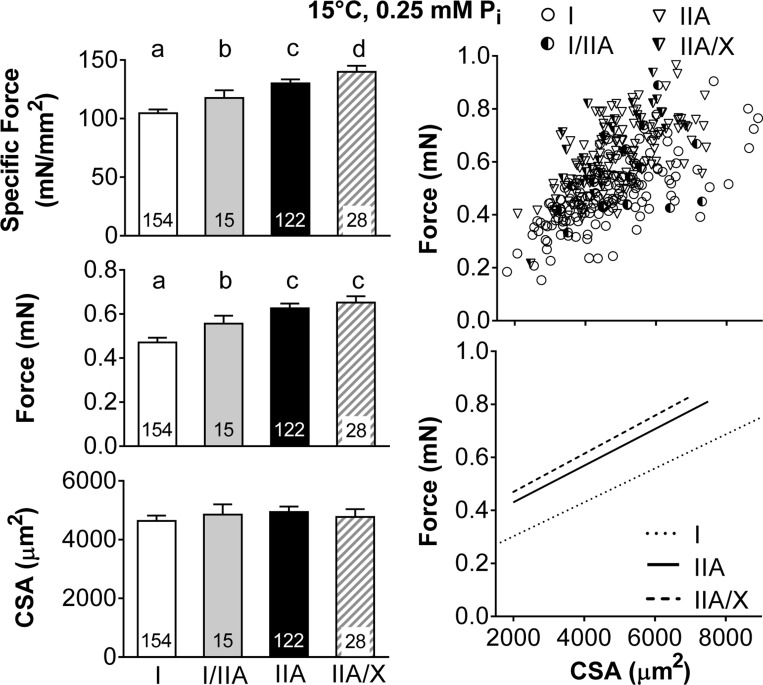

Average maximal Ca2+-activated isometric specific force (force/CSA) increased in MHC-expressing fibers in the order I < I/IIA < IIA < IIA/X due to greater force generation, as CSA was similar between fiber types (Fig. 1). These relationships were further examined by plotting the force vs. CSA for each individual fiber and performing a linear regression for each fiber type, except for MHC I/IIA fibers, as the number of fibers was inadequate to establish a reasonable fit. These plots show that, at similar CSA values, MHC I fibers generate less force than MHC IIA and IIA/X fibers (Fig. 1), as indicated by their significantly smaller (P < 0.01 for both) intercept (0.19 ± 0.02, 0.34 ± 0.02, and 0.37 ± 0.03 mN in I, IIA, and IIA/X, respectively), while they have a similar (P = 0.99) slope (62.6 ± 6.2, 62.8 ± 8.7, and 62.0 ± 21.0 mN/mm2 in I, IIA, and IIA/X, respectively). Thus, higher specific force in fibers expressing only MHC II isoforms (IIA and IIA/X) is related to an increased capacity for force production throughout the range of fiber CSAs examined.

Fig. 1.

Single skeletal muscle fiber maximum Ca2+-activated (pCa 4.5) specific force, force, and cross-sectional area (CSA) by fiber type at 15°C and 0.25 mM Pi. Left: average values, with number of fibers indicated at the base of each bar. Where fiber type effects were observed, different letters above bars identify pair-wise differences (P ≤ 0.05) between fiber types. Right: scatterplots, with each point representing an individual fiber. Lines indicate linear regressions for MHC I, IIA, and IIA/X fibers from raw data in scatterplots, with Pearson's correlation coefficients (r) = 0.705, 0.622, and 0.566, respectively, and all coefficients significant at P < 0.01. Number of fibers was inadequate to calculate linear regression of MHC I/IIA fiber force with CSA.

Singe-fiber properties at 25°C and 5 mM Pi.

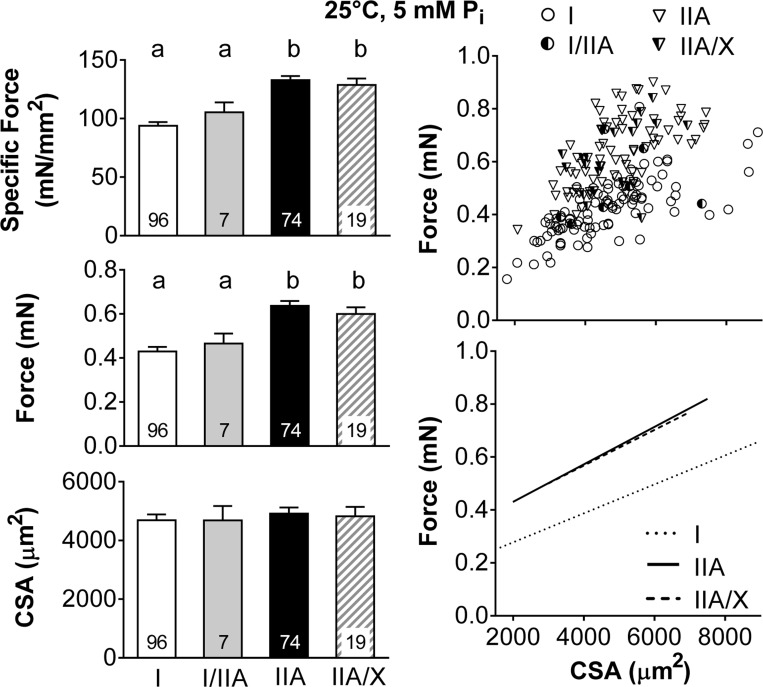

Average maximal Ca2+-activated isometric specific force was higher in fibers without MHC I (IIA and IIA/X) than fibers with MHC I (I and I/IIA), again due to increased force generation, as CSA was similar between fiber types (Fig. 2). These relationships were examined by plotting the force vs. CSA for each fiber type and performing a linear regression, except for MHC I/IIA fibers, as the number of these fibers was inadequate to establish a reasonable fit. MHC I fibers generate less force than MHC IIA and IIA/X fibers (Fig. 2) throughout the range of fiber sizes, as indicated by their significantly smaller (P < 0.01) intercept (0.14 ± 0.02, 0.34 ± 0.02, and 0.33 ± 0.03 mN in I, IIA, and IIA/X, respectively), while they have a similar (P = 0.40) slope (55.3 ± 6.6, 70.2 ± 9.3, and 68.5 ± 22.4 mN/mm2 in I, IIA, and IIA/X, respectively). Together with similar results at 15°C and 0.25 mM Pi, these differences further reinforce the notion that the reduced specific force in MHC I-containing fibers reflects fundamental differences in the myosin-actin cross-bridge interaction that lead to different intrinsic force-producing capacity between MHC I and II isoforms.

Fig. 2.

Single skeletal muscle fiber maximum Ca2+-activated (pCa 4.5) specific force, force, and CSA by fiber type at 25°C and 5 mM Pi. Left: average values, with number of fibers indicated at the base of each bar. Where fiber type effects were observed, different letters above bars identify pair-wise differences (P < 0.05) between fiber types. Right: scatterplots, with each point representing an individual fiber. Lines indicate linear regressions for MHC I, IIA, and IIA/X fibers, with r = 0.723, 0.617, and 0.527 and P < 0.01, P < 0.01, and P = 0.02, respectively. Number of fibers was inadequate to calculate linear regression of MHC I/IIA fiber force with CSA.

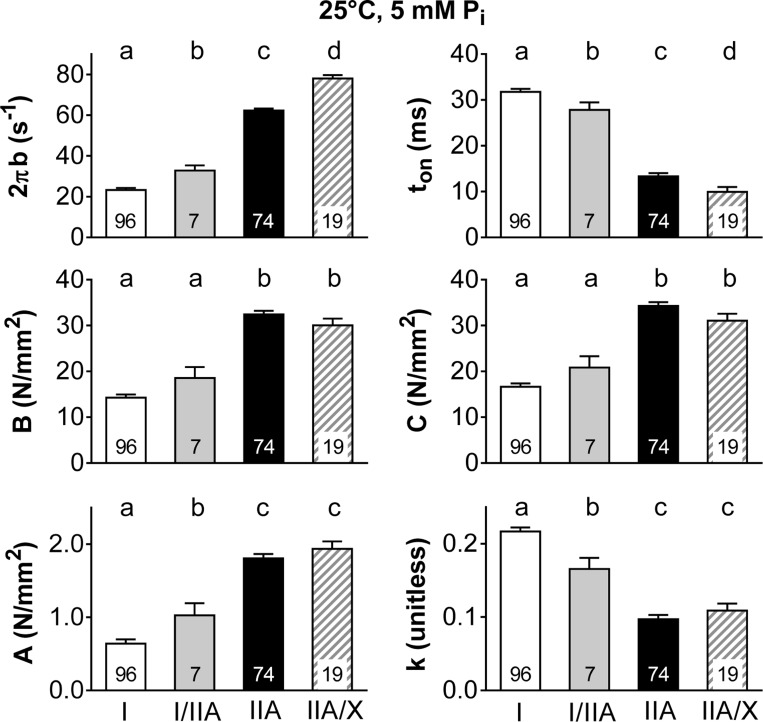

To evaluate the aspects of the myofilament mechanics that might explain differences in specific force between the various MHC-expressing fiber types, we evaluated the six model parameters estimated from sinusoidal analysis conducted during maximal Ca2+ activation (Fig. 3). The myosin-actin cross-bridge kinetics became faster in the order I < I/IIA < IIA < IIA/X, as shown by the increase in 2πb and shorter ton (Fig. 3). Parameters B and C were larger in fibers with only MHC II (IIA and IIA/X) than in fibers with MHC I (I and I/IIA; Fig. 3), indicating a greater number of strongly bound myosin heads and/or the cross-bridge stiffness, which may explain their higher isometric specific force and force generation (Fig. 2). The underlying stiffness of the lattice structure and the attached myosin heads in series increased in magnitude (larger A) and became more elastic (smaller k) as cross-bridge kinetics increased from MHC I to IIA, with MHC IIA and IIA/X producing similar values (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Sinusoidal analysis model parameters for maximum Ca2+-activated (pCa 4.5) fibers by fiber type at 25°C and 5 mM Pi. 2πb is the rate of myosin transition between the weakly and strongly bound states, and ton represents the average time myosin is attached to actin. Parameters B and C are proportional to the number of myosin heads strongly bound to actin and cross-bridge stiffness. A and k represent the viscoelastic magnitude and relationship between viscous and elastic modulus for the underlying stiffness of the lattice structure and the attached myosin heads in series. Average values are shown, with number of fibers indicated at the base of each bar. Where fiber type effects were observed, different letters above bars identify pair-wise differences (P < 0.05) between fiber types.

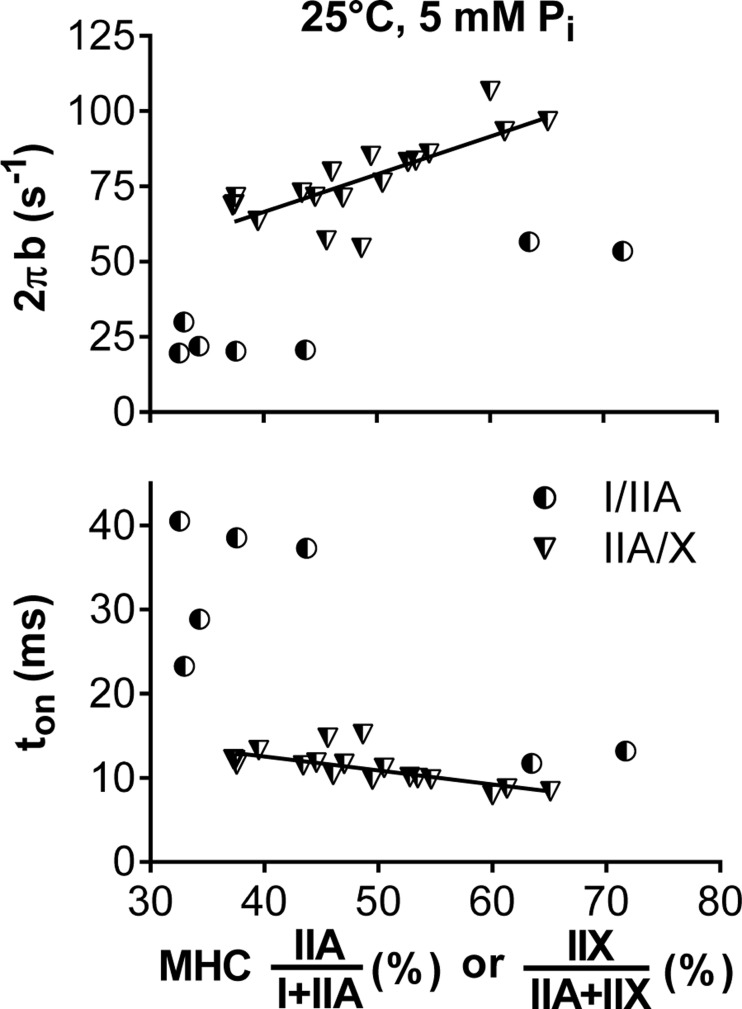

The role of the myosin isoform composition in dictating the mechanic/kinetic parameters is further highlighted by variance in their expression in hybrid fibers. In MHC IIA/X fibers, higher levels of the faster MHC IIX isoform linearly increased single-fiber myosin-actin cross-bridge kinetics, indicated by the faster 2πb and shorter ton (Fig. 4). Thus changes in these parameters are graded to the relative admixture of the expression of the two MHC isoforms within the same fiber. In MHC I/IIA fibers, higher levels of the faster MHC IIA isoform also increased cross-bridge kinetics (Fig. 4). However, the relationship was less well defined than in MHC IIA/X fibers, because few MHC I/IIA fibers were found to express proportionately similar isoforms. That is, only fibers expressing predominantly the MHC I (less than ∼30% MHC IIA) or IIA (<40% MHC I) isoform were found (i.e., there was a bimodal distribution).

Fig. 4.

Changes in myosin-actin cross-bridge kinetics with isoform concentration in MHC I/IIA and IIA/X fibers. Increasing values on the x-axis represent percentage of the faster MHC isoform (IIA for I/IIA and IIX for IIA/X fibers). Lines indicate linear regressions for 2πb (r = 0.769, P < 0.01) and ton (r = −0.689, P < 0.01) from MHC IIA/X fibers. Linear regressions were not determined from MHC I/IIA fibers, as percent MHC values were either high or low, with no clear relationship between them.

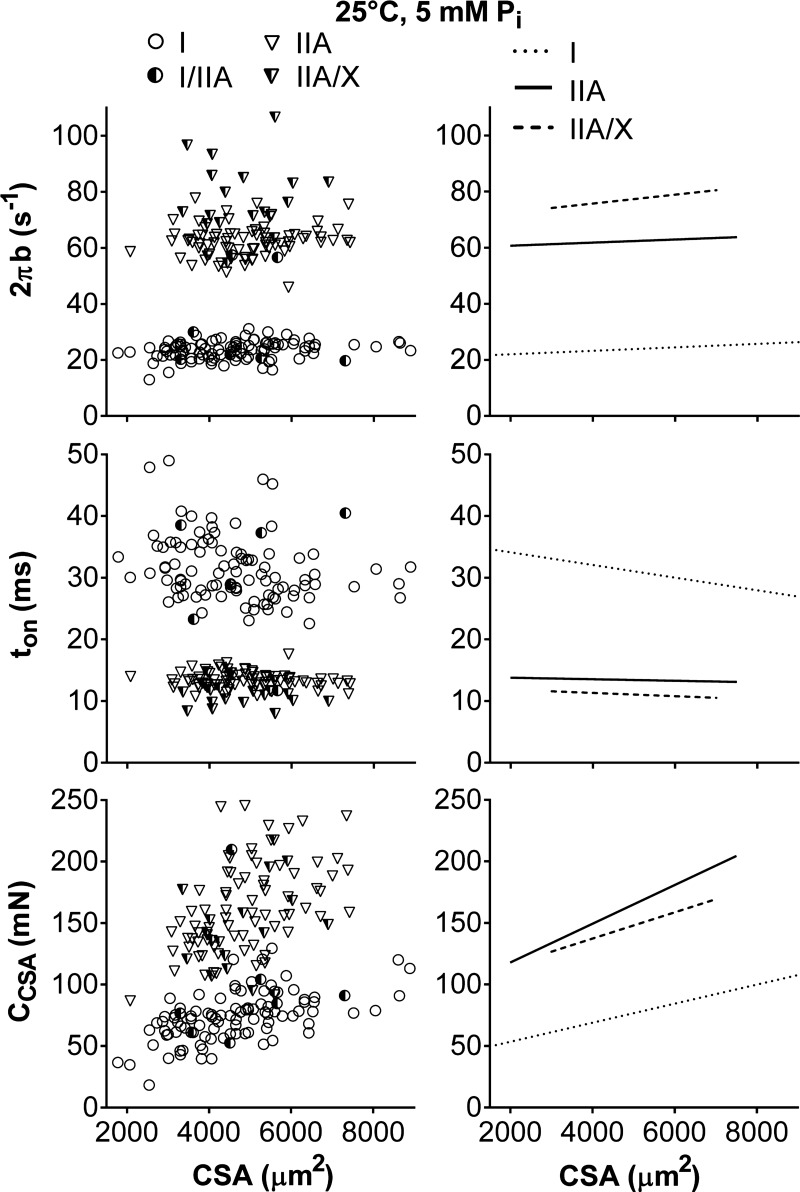

To understand how molecular mechanisms are altered by CSA to further clarify their role in the higher force production of fibers containing MHC II (IIA and IIA/X) than fibers containing MHC I (I and I/IIA; Fig. 2), we evaluated the relationships between the six curve-fit parameters and CSA for individual fibers. Myosin-actin cross-bridge kinetics (2πb and ton) were, for the most part, unchanged within a fiber type with CSA (Fig. 5), meaning their slopes were not different from zero (P = 0.14–0.34 for 2πb, P = 0.74–0.77 for ton), except for ton in MHC I fibers (−1.03 ± 0.27 × 10−3 ms/μm2, P < 0.01). Cross-bridge kinetics were distinct for each fiber type, as the intercepts for 2πb (20.6 ± 1.5, 59.1 ± 1.5, and 73.8 ± 2.1 s−1 in I, IIA, and IIA/X, respectively) and ton (34.6 ± 0.9, 16.8 ± 0.9, and 14.5 ± 1.3 ms in I, IIA, and IIA/X, respectively) were different (P < 0.01 for 2πb, P < 0.05 for ton) for each fiber type. Parameters historically normalized by dividing by CSA (A, B, and C) were not normalized (ACSA, BCSA, and CCSA) to remove potential colinearity between force production and these parameters [i.e., CSA is a well-known predictor of force production and could facilitate relationships between A, B, and C simply via colinearity (58)]. CCSA increased (P < 0.01) with CSA in MHC I and IIA fibers and showed a trend (P = 0.09) for increasing with CSA in MHC IIA/X fibers (Fig. 5). Intercepts of CCSA values were larger (P < 0.05) in MHC II- than MHC I-containing fibers (38 ± 9, 86 ± 13, and 95 ± 30 mN in I, IIA, and IIA/X, respectively), and MHC I and IIA fibers had different (P < 0.01) slopes (7.7 ± 1.8, 15.7 ± 2.5, and 10.7 ± 6.1 N/mm2 in I, IIA, and IIA/X, respectively). These results indicate that the number of strongly bound myosin heads and/or the cross-bridge stiffness increased with fiber size and was higher in MHC II-containing fibers at a given CSA, similar to force generation (Fig. 2). Parenthetically, as the B and C process magnitudes produce qualitatively near-identical results, we showed only the CCSA values.

Fig. 5.

Relationship between sinusoidal analysis model parameters (2πb, ton, and CCSA) and CSA for various fiber types at 25°C, pCa 4.5, and 5 mM Pi. Data points represent results from an individual fiber. Lines indicate linear regressions for MHC I, IIA, and IIA/X with Pearson's correlation coefficient and statistical significance. Myosin-actin cross-bridge kinetics (2πb and ton) did not change with CSA, as their slopes were not different from zero, except for ton in MHC I fibers (r = −0.284, P < 0.01). CCSA, proportional to the number of myosin heads strongly bound to actin and cross-bridge stiffness, increased with CSA (r = 0.560, 0.506, and 0.296; P < 0.01, P < 0.01, and P = 0.22 in I, IIA, and IIA/X, respectively). Number of fibers was inadequate to calculate linear regression of MHC I/IIA fibers with CSA.

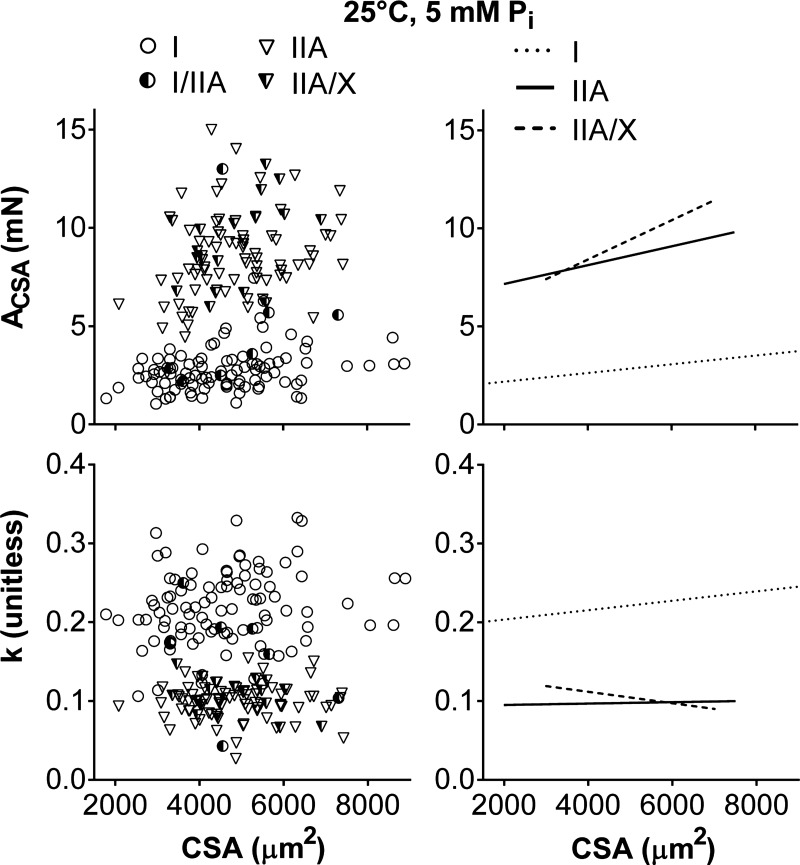

ACSA also increased (P ≤ 0.05 for MHC I, IIA, and IIA/X) with CSA (Fig. 6); however, Pearson's correlation coefficient was low (r = 0.262–0.292) for MHC I and IIA fibers, indicating a weak relationship compared with CCSA (r = 0.506–0.560). ACSA had similar (P = 0.10) slopes (0.22 ± 0.12, 0.48 ± 0.16, and 1.00 ± 0.39 N/mm2 in I, IIA, and IIA/X, respectively), and the intercepts were larger (P < 0.01 for both) in MHC II- than MHC I-containing fibers (1.2 ± 0.4, 6.9 ± 0.4, and 7.5 ± 0.6 mN in I, IIA, and IIA/X, respectively). k was unchanged in MHC II-containing fibers with CSA (Fig. 6), as their slopes were not different from zero (P = 0.43–0.82), but increased (P < 0.05) in MHC I fibers (5.9 ± 2.7 mm−2). k was lower in MHC II- than MHC I-containing fibers, as indicated by their smaller (P < 0.01 for both) intercepts (0.20 ± 0.01, 0.08 ± 0.01, and 0.09 ± 0.01 unitless in I, IIA, and IIA/X, respectively). ACSA and k results indicate that the magnitude of the underlying stiffness of the lattice structure and the attached myosin heads in series increased with CSA and was higher in MHC II-containing fibers, while the ratio of viscous to elastic properties remained relatively constant within a specific fiber type.

Fig. 6.

Relationship between sinusoidal analysis model parameters (ACSA and k) and CSA for various fiber types at 25°C, pCa 4.5, and 5 mM Pi. Data points represent results from an individual fiber. Lines indicate linear regressions for MHC I, IIA, and IIA/X, respectively. ACSA and k represent the viscoelastic magnitude and relationship between viscous and elastic modulus for the underlying stiffness of the lattice structure and the attached myosin heads in series. ACSA increased with CSA (r = 0.292, 0.262, and 0.450; P < 0.01, P = 0.02, and P = 0.05 in I, IIA, and IIA/X, respectively), but k had a slope different from zero only in MHC I fibers (r = 0.179, P = 0.08). Number of fibers was inadequate to calculate linear regression of MHC I/IIA fibers with CSA.

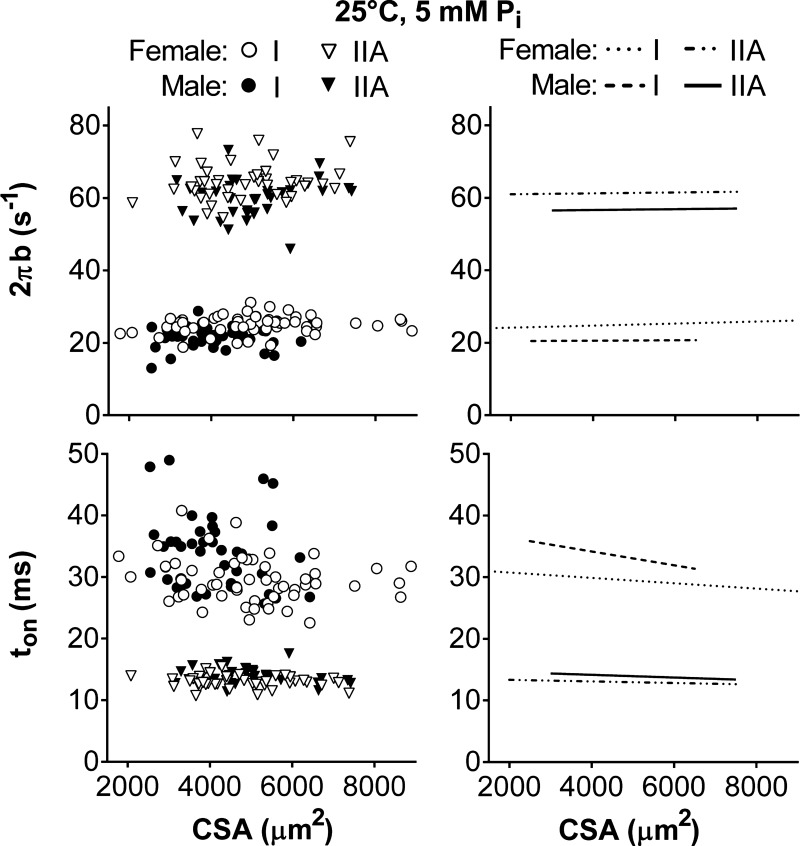

To understand if force generation and molecular mechanisms were different between the sexes, we examined the relationship between force and the six curve-fit parameters with CSA for men and women separately. These comparisons were performed in MHC I and IIA, but not MHC I/IIA and MHC IIA/X, fibers, as the number of measurements was not adequate to establish reasonable fits. Myosin-actin cross-bridge kinetics (2πb and ton) were the only variables affected by sex and were distinct within fiber types (Fig. 7), as male and female intercepts were different in MHC I and IIA fibers (P < 0.01 for all 4 comparisons). Women had faster cross-bridge kinetics, or higher 2πb (23.5 ± 0.6 and 20.5 ± 0.9 s−1 for women and men, respectively, in I; 60.8 ± 1.2 and 56.1 ± 2.8 s−1 for women and men, respectively, in IIA) and lower ton (32.5 ± 1.0 and 36.5 ± 1.6 s−1 for women and men, respectively, in I; 13.8 ± 0.3 and 14.8 ± 0.6 s−1 for women and men, respectively, in IIA), than men in both fiber types. After separation by sex, cross-bridge kinetics remained unchanged with CSA, meaning their slopes were not different from zero (P = 0.23–0.43 for 2πb, for P = 0.12–0.38 ton). These results indicate that the nonzero slope for ton in MHC I fibers (Fig. 5) was due to a difference between the sexes (Fig. 7). Overall, these differences in y-intercepts indicate that cross-bridge kinetics are constant across the range of fiber sizes examined but are simply higher for any given CSA in healthy, young women than men.

Fig. 7.

Relationship between cross-bridge kinetics (2πb and ton) and CSA for men and women in MHC I and IIA fibers at 25°C, pCa 4.5, and 5 mM Pi. Data points represent results from an individual fiber. Lines indicate linear regressions. Myosin-actin cross-bridge kinetics (2πb and ton) did not change with CSA, as their slopes were not different from zero.

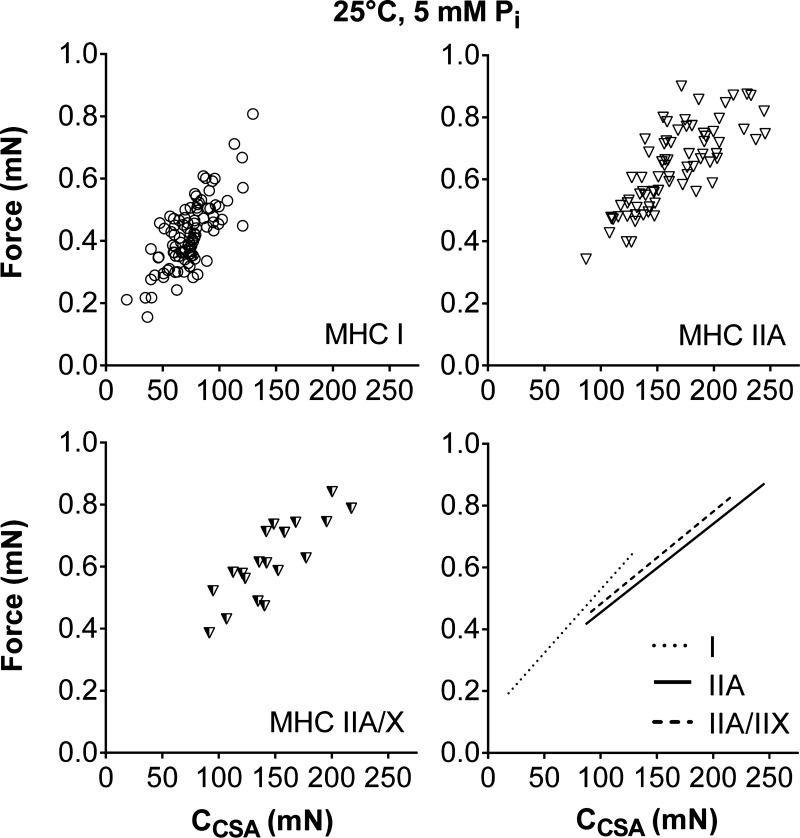

To examine whether the variance in force production is better described by fiber structure (CSA) or myofilament mechanics (2πb, ton, CCSA, ACSA, and k), we performed correlations between force and these parameters (Table 2). Cross-bridge kinetics (2πb and ton) and k were not related to force, while ACSA showed a relationship that improved as fiber cross-bridge kinetics increased (Table 2). Force was most highly correlated (r) with CCSA, with CCSA explaining (r2) 55, 61, and 68% of the force variability in MHC I, IIA, and IIA/X fibers, respectively, compared with CSA, which explained 52, 38, and 28%. Force increased (P < 0.01) with CCSA in MHC I, IIA, and IIA/X fibers (Fig. 8). MHC I fibers had a higher slope (P < 0.01) than MHC IIA fibers and showed a trend (P = 0.09) toward a higher slope than MHC IIA/X fibers (4.1 ± 0.4, 2.8 ± 0.3, and 3.0 ± 0.5 × 10−3 mN/mN in I, IIA, and IIA/X, respectively), while all fiber types had similar (P = 0.54) intercepts (0.12 ± 0.03, 0.17 ± 0.04, and 0.18 ± 0.08 mN in I, IIA, and IIA/X, respectively). These results show that force increased more for a change in CCSA in MHC I than IIA and IIA/X fibers. As CCSA and ACSA are both related to the cross-bridge stiffness and number, these results indicate that force is better predicted by cross-bridge characteristics than fiber CSA.

Table 2.

Pearson's correlation coefficients for force with CSA and with sinusoidal analysis model parameters, including cross-bridge kinetics

| MHC | CSA, μm2 | 2πb, s−1 | ton, ms | CCSA, N/mm2 | ACSA, N/mm2 | k |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 0.723*‡ | 0.041 | −0.086 | 0.742*‡ | 0.394‡ | 0.181 |

| IIA | 0.617‡ | −0.138 | 0.129 | 0.784*‡ | 0.545‡ | −0.043 |

| IIA/X | 0.527† | −0.183 | 0.072 | 0.827*‡ | 0.844*‡ | −0.241 |

Values were obtained at 25°C and 5 mM Pi.

CSA, cross-sectional area; MHC, myosin heavy chain.

r > 0.707 or r2 > 0.50, or >50% of force variation is explained by this variable.

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01.

Fig. 8.

Relationship between force and CCSA, which is proportional to the number of myosin heads strongly bound to actin and cross-bridge stiffness, at 25°C, pCa 4.5, and 5 mM Pi. CCSA explains more of the variance in the force data (55, 61, and 68% in I, IIA, and IIA/X, respectively) than CSA or the other sinusoidal analysis parameters (Table 2). Data points represent results from an individual fiber. Lines indicate linear regressions for MHC I, IIA, and IIA/X, with Pearson's correlation coefficient and statistical significance in Table 2.

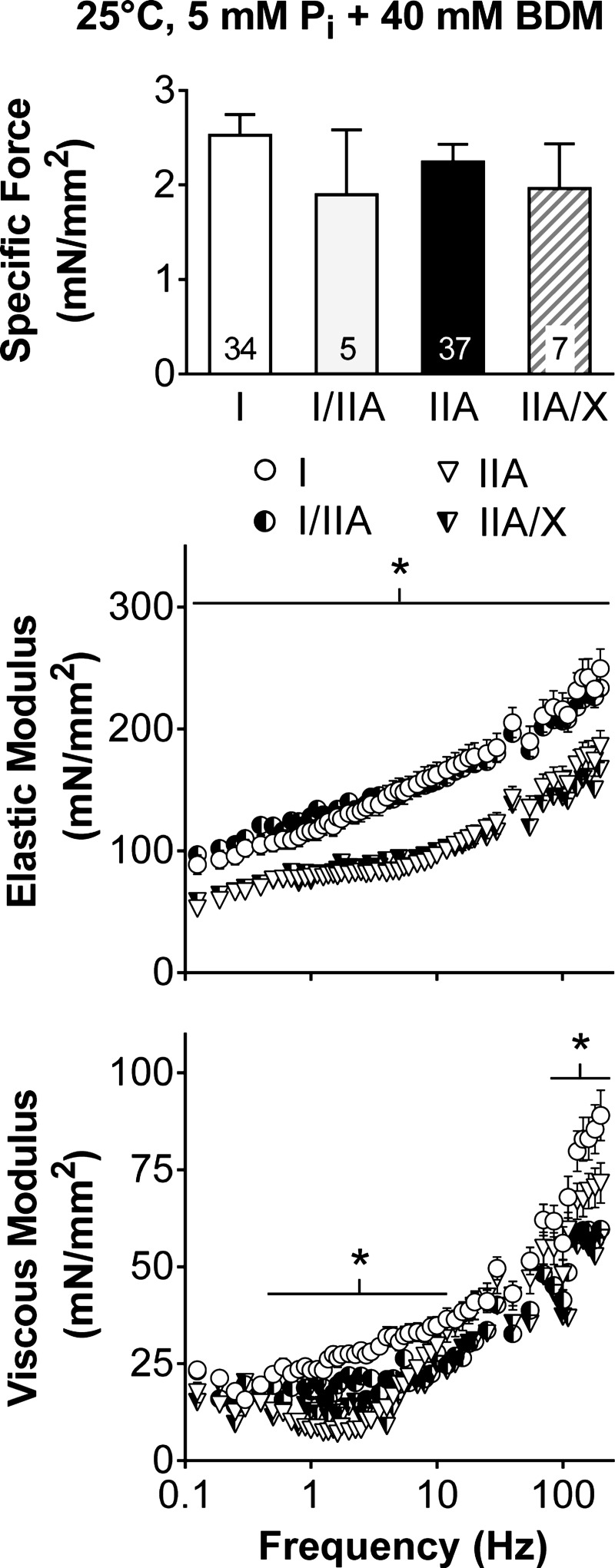

As the passive (i.e., at pCa 8) properties of the fibers are important in determining contractile performance (38, 65) and provide insight into changes in the underlying structure, we evaluated the different MHC isoforms by measuring isometric specific force and performing sinusoidal analysis in relaxing solution with BDM, which places the myosin head in a weakly bound state (39). Relaxed isometric specific force was similar across all fiber types (P = 0.58), while higher elastic (across the entire frequency range) and viscous (0.5–10 and 85–200 Hz) moduli were found in MHC I than IIA fibers (Fig. 9). The higher elastic modulus with the myosin heads in a weakly bound state in MHC I fibers suggests that the underlying structure is stiffer and would permit better force transmission of the myosin heads and, in turn, higher isometric specific forces, than in MHC IIA fibers. However, as MHC IIA fibers generate higher specific forces and forces at a given CSA (Fig. 2), the underlying myofilament stiffness does not explain the fiber type differences in isometric specific force.

Fig. 9.

Isometric specific force, as well as elastic and viscous modulus responses, under relaxed conditions (pCa 8) with 2,3-butanedione monoxime (BDM), which places myosin heads in a weakly bound state. Number of fibers is indicated at the base of each bar. *Significant difference (P < 0.05) between MHC I and IIA fibers, as the number of hybrid fiber types (I/IIA and IIA/X) was inadequate to include in the analysis.

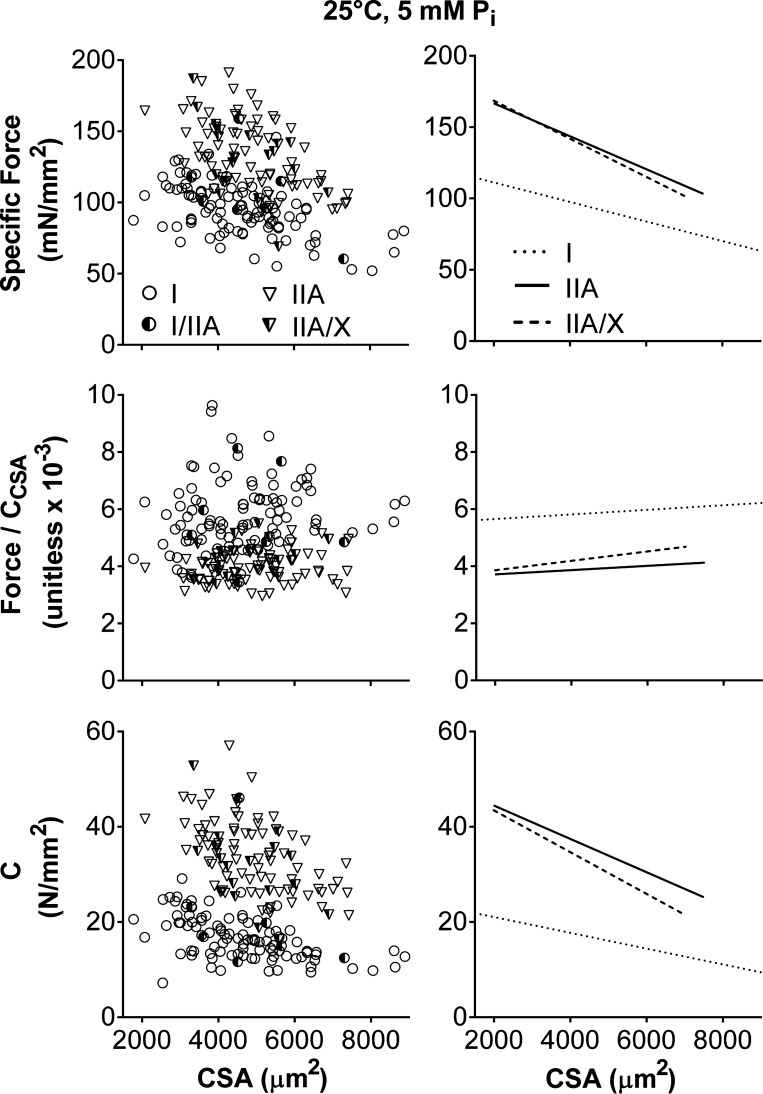

Specific force decreased as fiber size increased (P < 0.01; Fig. 10), in agreement with previous studies (13, 18). MHC I fibers had a lower intercept (P < 0.01) than MHC IIA and IIA/X fibers (125 ± 6, 190 ± 10, and 195 ± 22 mN/mm2 in I, IIA, and IIA/X, respectively). MHC I fibers had a less steep slope (P < 0.05) than MHC IIA fibers and a slope similar (P = 0.15) to MHC IIA/X fibers (−6.8 ± 1.3, −11.5 ± 1.9, and −13.4 ± 4.5 N in I, IIA, and IIA/X, respectively). As force was best predicted by CCSA (Table 2), force was divided by CCSA, basically normalizing force to the number and stiffness of the strongly bound myosin heads, and plotted vs. CSA (Fig. 10). Force/CCSA in all fiber types was unchanged with CSA, as the slopes were not different from zero (P = 0.27–0.51), showing that force is related to the number and/or stiffness of the cross bridges independent of CSA. Force/CCSA was higher (P < 0.01) in MHC I than IIA fibers, while force/CCSA in MHC IIA/X fibers was similar to that in MHC I and IIA fibers (5.5 ± 0.4, 3.6 ± 0.5, and 3.5 ± 1.2 × 10−3 unitless in I, IIA, and IIA/X, respectively). C, or the number and stiffness of the cross bridges per CSA, decreased (P < 0.01) with CSA in all fiber types (Fig. 10), indicating that the number and/or stiffness of the strongly bound myosin heads per area is not independent of fiber size. In other words, the relative proportion of strongly bound myosin heads and/or their stiffness decreases as fiber size increases. C had larger intercepts (P < 0.01) and steeper slopes in MHC II (P < 0.01 for IIA, P < 0.05 for IIA/X) than MHC I fibers (24 ± 2, 52 ± 3, and 52 ± 6 N/mm2 in I, IIA, and IIA/X, respectively; −1.7 ± 0.4, −3.5 ± 0.5, and −4.4 ± 1.3 kN/mm4 in I, IIA, and IIA/X, respectively). C explained (r2) 41, 64, and 73% of the isometric specific force variability, while CSA explained only 28, 28 and 25%, in MHC I, IIA, and IIA/X fibers, respectively. Thus force may depend more on the number and/or stiffness of strongly bound cross bridges in MHC II- than MHC I-expressing fibers.

Fig. 10.

Relationship of isometric specific force, force/CCSA, and C to CSA for various fiber types at 25°C, pCa 4.5, and 5 mM Pi. Each data point represents an individual fiber. Lines indicate linear regressions for MHC I, IIA, and IIA/X, respectively, with Pearson's correlation coefficient and statistical significance. Isometric specific force (r = −0.527, −0.533, and −0.501; P < 0.01, P < 0.01, and P = 0.03 in I, IIA, and IIA/X, respectively) and C (r = −0.521, −0.541, and −0.513; P < 0.01, P < 0.01, and P = 0.03) decreased with CSA. Force/CCSA did not change with CSA, as their slopes were not different from zero. Number of fibers was inadequate to calculate linear regression of MHC I/IIA fibers with CSA.

DISCUSSION

This study examined myofilament mechanics, including myosin-actin cross-bridge kinetics, during maximal Ca2+-activated and passive isometric conditions in single human skeletal muscle fibers with various MHC isoform compositions. A novelty of this work is the examination of effects of fiber size on molecular mechanisms by analysis of the results across the range of physiological fiber CSAs. Fibers with faster cross-bridge kinetics, specifically those containing only MHC II isoforms (IIA and IIA/X), produced greater maximal Ca2+-activated isometric specific force (force/CSA) than those containing the slower MHC I isoforms (MHC I and I/IIA). The larger force-generating capacity in fibers containing only MHC II isoforms was due to an increase in the number and/or stiffness of the strongly bound cross bridges (CCSA). Force was better predicted using CCSA than CSA, indicating that force variation within fiber types is better explained by variation in this cross-bridge mechanical property than fiber size. The relative proportion of formed cross bridges and/or their stiffness was reduced with fiber size, causing isometric specific force to decline as CSA increased. The specific force decrease with fiber size was not driven by a change in myosin-actin cross-bridge kinetics, as these remained unchanged with CSA in MHC I and IIA fibers from men and women, although women had faster kinetics (higher 2πb and shorter ton). Thus, in addition to defining various cross-bridge kinetic parameters, our results provide a novel molecular mechanism to explain variation in specific force among the different fiber types in human skeletal muscle that may have relevance to understanding how various physiological and pathophysiological conditions modulate single-fiber and, in turn, whole muscle contractility.

MHC isoform.

Numerous human skeletal muscle studies have examined the effects of MHC isoform on force generation using isometric specific force, usually comparing MHC I and IIA fibers. We have summarized these studies, including the current work, and organized them by increasing number of MHC I and IIA fibers measured per experimental group in Table 3. In general, the conclusion from studies with fewer volunteers (<5) and fibers (<80) is that MHC I and IIA specific forces are similar (18, 22, 23, 31, 59, 62), while studies with a larger number of volunteers (>5) and fibers (>80) suggest that specific forces are higher in MHC IIA than I fibers (2, 8, 10, 11, 14, 26, 29, 50, 51, 70), arguing that studies failing to detect differences in specific force between fiber types may have been underpowered. Our study is among the largest, in terms of number of fibers examined and volunteers recruited, and shows greater force production in fibers containing only MHC II isoforms (IIA and IIA/X) than in those containing MHC I isoforms (I and I/IIA) under both experimental conditions [15°C and 0.25 mM Pi (Fig. 1) and 25°C and 5 mM Pi (Fig. 2)]. Overall, the evidence indicates that MHC IIA fibers are capable of generating more force than MHC I fibers.

Table 3.

Studies examining isometric specific force differences between MHC isoforms in human skeletal muscle

|

n |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Experimental Group | Age, yr | M | F | Temp, °C | MHC I + IIA Fibers | MHC I < IIA Specific Force |

| Linari et al. (36) | 20–40 | 5 | 12 | 27* | + | ||

| Harridge et al. (21) | Sol | 30 ± 2 | 7 | 12 | 18 | − | |

| TB | 16 | + | |||||

| VL | 34 | − | |||||

| Bottinelli et al. (3) | na | na | 12 | 35 | + | ||

| Hilber and Galler (23) | na | 1 | 22–24 | 36 | − | ||

| Steinen et al. (59) | 36–55 | 3 | 20 | 40 | − | ||

| Larsson and Moss (31) | 27–38 | 1 | 3 | 15 | 46 | − | |

| He et al. (22) | 30–50 | 2 | 12 | 46 | − | ||

| Szentesi et al. (62) | 24–46 | 2 | 20 | 46 | − | ||

| Gilliver et al. (18) | 18–25 | 18 | 15 | 79 | − | ||

| Hvid et al. (26) | Young | 24 ± 1 | 9 | 22 | 88 | + | |

| Older | 67 ± 2 | 8 | 79 | + | |||

| Bottinelli et al. (2) | 30–50 | 6 | 12 | 96 | + | ||

| Choi and Widrick (8) | 25 ± 2 | 5 | 5 | 15 | 108 | + | |

| Paoli et al. (51) | 25 ± 5 | 9 | 9 | 12 | 143 | + | |

| Widrick et al. (70) | PreRT | 27 ± 2 | 6 | 15 | 148 | + | |

| Pansarasa et al. (50) | PreRT | 25 ± 6 | 5 | 12 | 153 | + | |

| PostRT | 133 | + | |||||

| D'Antona et al. (11) | Young | 30 ± 1 | 7 | 12 | 218 | + | |

| Older | 73 ± 1 | 7 | 192 | + | |||

| D'Antona et al. (10) | Control | 30 ± 5 | 5 | 12 | 165 | + | |

| RT | 27 ± 1 | 5 | 227 | + | |||

| Present study | 15°C | 24 ± 1 | 5 | 7 | 15 | 276 | + |

| 25°C | 25 | 170 | + | ||||

| Frontera et al. (14) | Young | 37 ± 1 | 7 | 15 | 183 | + | |

| Older | 74 ± 2 | 12 | 303 | + | |||

| Older | 72 ± 1 | 12 | 296 | − | |||

| Krivickas et al. (29) | 23–83 | 58 | 61 | 15 | 2,398 | + | |

Values are means ± SE and ranges. Studies are organized by increasing number of MHC I and IIA fibers measured in a group.

n, Number of human volunteers; M, male; F, female; na, not available; RT, resistance training; Sol, soleus; TB, triceps brachii; VL, vastus lateralis. +, MHC I < IIA specific force; −, MHC I = IIA specific force.

MHC IIA fibers include IIA/X fibers.

Our findings identify two potential mechanisms to explain greater force production in fibers containing only MHC II isoforms than in those containing MHC I isoforms, more specifically, an increase in 1) number and/or 2) stiffness of strongly bound cross bridges in MHC II-expressing fibers. Although using our current measurements we are unable to differentiate between these two mechanisms, previous studies by other researchers indicate that either or both of these mechanisms may apply. Studies performed in single human skeletal muscle fibers suggest an increase in cross-bridge number, due to a higher duty ratio, and an additional, but arguably smaller, increase in the force-generating capacity of individual myosin heads, especially under isometric conditions (36). Myosin extracted directly onto coverslips from short single human skeletal fiber segments (single-fiber myosin in vitro motility assay) shows an increase in ensemble force-generating capacity in MHC II (IIA, IIA/X, and IIX) compared with MHC I fibers (35), indicating that the myosin molecules are at least partially, if not completely, responsible for the improved force generation. However, as there are no actin regulatory proteins in these experiments and myofilaments are removed from the normal three-dimensional structure of the myofilament lattice, these measurements may not describe the behavior of myosin in single fibers. Single-fiber (4) and single-molecule (7) measurements suggest that the increased force production with faster MHC isoforms is at least in part due to higher cross-bridge stiffness. These studies compared isoforms from different species: MHC I from human soleus with MHC IIX from rabbit psoas (4) and MHC I from rat soleus with MHC IIB from mouse gastrocnemius (7). As contractile properties of isolated myosin behaves differently across these species between corresponding MHC isoforms (53), the variation in stiffness could potentially be due to species differences, and not the MHC isoform. In within-species (rabbits) comparisons, single-molecule measurements indicate that MHC I from soleus (4) is less stiff than MHC IIX from psoas (33). In contrast, studies comparing smooth (turkey gizzard) and skeletal (chicken pectoralis) isoforms (20) and α and β cardiac (rabbit and rat) isoforms (49, 61) show no differences in unitary force, suggesting that the force-generating capacities of individual myosin molecules are similar. Collectively, these results suggest that variation in the mechanical properties of different myosin isoforms is the most likely explanation for increased force production in MHC II fibers, although whether this is due to an increase in cross-bridge number and/or stiffness remains unclear. Notably, our results indicate that MHC II-expressing fibers are more dependent on these cross-bridge properties than MHC I fibers, as CCSA and C explain more of the variation in force and specific force, respectively, in MHC II fibers (55 and 41% in I, 61 and 64% in IIA, and 68 and 73% in IIA/X).

CSA.

Cross-bridge kinetics increased as myosin attachment time (ton) became shorter and the rate of myosin force production (2πb) became faster in the order I < I/IIA < IIA < IIA/X (Fig. 3). These results were expected on the basis of ATPase (1) and stretch activation (23, 24) studies in human skeletal muscle and experiments using similar techniques in animal skeletal muscle fibers (16, 69) but represent the first measurements in human tissue from a homogenous group of healthy young volunteers under isometric conditions that permit the calculation of cross-bridge kinetic parameters to identify specific steps in the cross-bridge cycle. Cross-bridge kinetics (2πb and ton) remained consistent in MHC I and IIA fibers across the range of CSAs when the sexes were examined separately, with women having faster kinetics than men (Fig. 7). When the sexes were examined together, the only exception was that ton decreased with increasing CSA in MHC I fibers (Fig. 5), most likely due to faster kinetics (7–15%) and larger CSA values (5,001 ± 213 vs. 4,114 ± 161 μm2, P < 0.05) in women than men. This effect of sex agrees with our recent work showing sex differences in cross-bridge kinetics with age (41) and muscle disuse (6). As cross-bridge kinetics influence single-fiber contractile properties, the specific force and/or velocity differences between young (71) and older (30, 67, 71) men and women may be driven by this sex-dependent variation in myosin-actin interactions, as we previously characterized with disuse (6). Notably, the maintenance of cross-bridge performance across various muscle sizes shows that molecular-level interactions are not affected by a change in the amount of circumferential contractile material, at least within the range of CSAs examined (1,780–8,900 μm2), which provides a reasonably broad survey of the physiological range of CSAs observed in humans (34, 54).

Previous studies have proposed that the decrease in isometric specific force with increasing fiber size is due to altered cross-bridge kinetics, as radial diffusion may become more limiting in larger fibers, leading to an accumulation of molecules (13, 18, 60), such as ADP or Pi. In this study, isometric force did indeed decline in larger fibers, but without a change in cross-bridge kinetics, indicating that another mechanism must be responsible. As the number and stiffness of the strongly bound cross bridges (CCSA) better predicted force generation than CSA, force was normalized to CCSA (force/CCSA) and was found to remain constant across the various fiber sizes (Fig. 10). This indicates that these properties of the strongly bound cross bridges dictate force production regardless of fiber size, which agrees with models showing that force generation is dependent on the number of strongly bound myosin heads, their stiffness, and their step size (25, 40, 47, 63). However, as fibers become larger, the relative proportion of myosin heads strongly bound and/or their stiffness decreases compared with smaller fibers, as shown by the decline in C with CSA (Fig. 10), which would decrease the force generated per fiber size (i.e., specific force). A potential mechanism to explain this finding is a greater Ca2+ gradient in large fibers, leading to fewer strongly bound cross bridges in their core than in small fibers. As Ca2+ concentration may not alter the cross-bridge kinetics measured in this study (19), this mechanism could be consistent with our findings of similar kinetics across the CSA range. Experimental and modeling results indicate that physiological levels of Ca2+ are equilibrated throughout a small (50- to 60-μm-diameter) skinned fiber in ∼15–20 s (45, 68). This Ca2+ equilibration time can be drastically reduced to ∼0.15 s in small fibers by reducing the amount of Ca2+ buffer (EGTA) in the fiber immediately before Ca2+ activation (45), as in our present experiments, in which we allowed the fiber to bathe for 30 s in 0.5 mM EGTA before activation. On the basis of these findings, we conservatively hypothesize that Ca2+ is quickly (<1–5 s) distributed within all our fibers, provided EGTA is significantly reduced by our preactivation bathing. According to the measured radial coefficient of EGTA in relaxed fibers [D = 460 μm2/s (45)] and the diffusion equation [x = (2 × D × t)1/2], the mean distance that EGTA will have diffused (x) in 30 s of bathing time (t) is 166 μm, which is three times greater than our largest fiber radius of 53 μm, indicating that our use of a low-EGTA bath significantly reduces the EGTA concentration within the fiber. Another approach is to use equations that model diffusion in a cylinder to show that >95% of the solute (Mt/M∞, i.e., the fraction of the diffusing substance that has entered the cylinder) will be removed from a large fiber (radius = a = 53 μm) in 30 s (t), assuming that the bathing solution is initially solute-free (Fig. 5.7 in Ref. 9), which is reasonable, considering the order-of-magnitude difference in EGTA concentrations between preactivating (0.5 mM) and activating (5 mM) solutions. These studies and calculations indicate that the decreased isometric specific force in larger fibers is likely not due to a Ca2+ gradient along the radial axis of the fiber. Another potential mechanism to explain this finding is that fiber swelling after skinning is greater in larger fibers, causing fewer cross bridges to form; however, our preliminary work shows slightly more swelling of small than large human skeletal muscle fibers (Miller et al., unpublished results). Moreover, the decrease in isometric specific force with fiber CSA remains even after skinned fibers are returned to in vivo size via osmotic compression with dextran T500 (Miller et al., unpublished results). These results indicate the reduced specific force with fiber size is not an artifact of fiber swelling and, thus, suggest that this mechanism likely occurs in vivo as well. The reason for the specific force reduction with fiber size is unknown, but it could be explained by decreases in myosin concentration and/or thick or thin filament stiffness with fiber size. If specific force is similarly altered in fibers as they undergo changes in CSA, it may represent a mechanism whereby muscle fiber force production is modulated through development or growth of muscle fibers or during muscle atrophy.

Passive properties.

The passive properties of the different fiber types provide insight into potential differences between weakly bound cross bridges and the underlying fiber structure. MHC I and IIA fibers had similar passive specific forces, but MHC I fibers were stiffer than MHC IIA fibers. As MHC I and IIA fibers have similar myosin concentrations (11, 43), the increase in passive stiffness could be due to stiffer MHC I weakly bound cross bridges. More likely, the increase in stiffness represents the isoform differences observed within (e.g., Z-line and M-band proteins, titin) and between (e.g., plectin) the myofibrils (57). Although titin plays an important role in determining passive properties, its importance has been related to muscle function (65), rather than specific MHC isoforms (15), in human skeletal muscle. Thus the higher elastic modulus in MHC I fibers indicates stiffer protein(s) within and/or between the myofibrils, which could potentially lead to better force transmission. A higher force transmission could be responsible for a greater force production per strongly bound cross bridge in MHC I fibers, as suggested by higher force/CCSA in MHC I than IIA fibers (Fig. 10). Despite the better force transmission, MHC I fibers produce less force than MHC IIA fibers (see above). Together, our findings show potentially important MHC isoform differences in passive properties, especially as these characteristics are relevant in determining active contractile performance (65).

Summary.

Myosin-actin cross-bridge kinetics did not change with fiber size but were generally faster in women than men. However, isometric specific force declined as fiber size increased due to a reduction in relative cross-bridge number or stiffness regardless of sex. For single-fiber studies, a fiber size difference over time or between two groups could lead to the fibers having different specific forces. Thus, reporting force-CSA curves could provide important information for understanding how various physiological or pathological conditions/stimuli impact skeletal muscle strength. In agreement with other studies (4, 7, 35, 36), our results show that human skeletal muscle fibers containing only MHC II isoforms (IIA and IIA/X) produce larger forces and isometric specific forces than those containing the MHC I isoforms, due to strongly bound cross bridges increasing in number and/or increasing in stiffness. Collectively, our study reveals novel molecular-level performance differences between fibers of various sizes and with different myosin isoforms that impact single-fiber force generation and may lead to alterations in whole muscle performance.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Institute on Aging Grants AG-031303 and AG-033547, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-59408, and National Institutes of Health Division of Research Resources Grant RR-000109.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.S.M., P.A.A., and M.J.T. developed the concept and designed the research; M.S.M. and N.G.B. performed the experiments; M.S.M., N.G.B., and B.M.P. analyzed the data; M.S.M., N.G.B., B.M.P., and M.J.T. interpreted the results of the experiments; M.S.M. and N.G.B. prepared the figures; M.S.M. drafted the manuscript; M.S.M., N.G.B., P.A.A., B.M.P., and M.J.T. edited and revised the manuscript; M.S.M., N.G.B., P.A.A., B.M.P., and M.J.T. approved the final version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the volunteers who dedicated their valuable time to these studies and Alan Howard for statistical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bloemink MJ, Deacon JC, Resnicow DI, Leinwand LA, Geeves MA. The superfast human extraocular myosin is kinetically distinct from the fast skeletal IIa, IIb, and IId isoforms. J Biol Chem 288: 27469–27479, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bottinelli R, Canepari M, Pellegrino MA, Reggiani C. Force-velocity properties of human skeletal muscle fibres: myosin heavy chain isoform and temperature dependence. J Physiol 495: 573–586, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bottinelli R, Pellegrino MA, Canepari M, Rossi R, Reggiani C. Specific contributions of various muscle fibre types to human muscle performance: an in vitro study. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 9: 87–95, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenner B, Hahn N, Hanke E, Matinmehr F, Scholz T, Steffen W, Kraft T. Mechanical and kinetic properties of β-cardiac/slow skeletal muscle myosin. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 33: 403–417, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Callahan DM, Bedrin NG, Subramanian M, Berking J, Ades PA, Toth MJ, Miller MS. Age-related structural alterations in human skeletal muscle fibers and mitochondria are sex specific: relationship to single-fiber function. J Appl Physiol 116: 1582–1592, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callahan DM, Miller MS, Sweeny AP, Tourville TW, Slauterbeck JR, Savage PD, Maugan DW, Ades PA, Beynnon BD, Toth MJ. Muscle disuse alters skeletal muscle contractile function at the molecular and cellular levels in older adult humans in a sex-specific manner. J Physiol 592: 4555–4573, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Capitanio M, Canepari M, Cacciafesta P, Lombardi V, Cicchi R, Maffei M, Pavone FS, Bottinelli R. Two independent mechanical events in the interaction cycle of skeletal muscle myosin with actin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 87–92, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi SJ, Widrick JJ. Calcium-activated force of human muscle fibers following a standardized eccentric contraction. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 299: C1409–C1417, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crank J. The Mathematics of Diffusion. Oxford, UK: Clarendon, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 10.D'Antona G, Lanfranconi F, Pellegrino MA, Brocca L, Adami R, Rossi R, Moro G, Miotti D, Canepari M, Bottinelli R. Skeletal muscle hypertrophy and structure and function of skeletal muscle fibres in male body builders. J Physiol 570: 611–627, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Antona G, Pellegrino MA, Adami R, Rossi R, Carlizzi CN, Canepari M, Saltin B, Bottinelli R. The effect of ageing and immobilization on structure and function of human skeletal muscle fibres. J Physiol 552: 499–511, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D'Antona G, Pellegrino MA, Carlizzi CN, Bottinelli R. Deterioration of contractile properties of muscle fibres in elderly subjects is modulated by the level of physical activity. Eur J Appl Physiol 100: 603–611, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elzinga G, Stienen GJ, Wilson MG. Isometric force production before and after chemical skinning in isolated muscle fibres of the frog Rana temporaria. J Physiol 410: 171–185, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frontera WR, Suh D, Krivickas LS, Hughes VA, Goldstein R, Roubenoff R. Skeletal muscle fiber quality in older men and women. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 279: C611–C618, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fry AC, Staron RS, James CB, Hikida RS, Hagerman FC. Differential titin isoform expression in human skeletal muscle. Acta Physiol Scand 161: 473–479, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galler S, Wang BG, Kawai M. Elementary steps of the cross-bridge cycle in fast-twitch fiber types from rabbit skeletal muscles. Biophys J 89: 3248–3260, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garner DJ, Widrick JJ. Cross-bridge mechanisms of muscle weakness in multiple sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 27: 456–464, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilliver SF, Degens H, Rittweger J, Sargeant AJ, Jones DA. Variation in the determinants of power of chemically skinned human muscle fibres. Exp Physiol 94: 1070–1078, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gordon AM, Homsher E, Regnier M. Regulation of contraction in striated muscle. Physiol Rev 80: 853–924, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guilford WH, Dupuis DE, Kennedy G, Wu J, Patlak JB, Warshaw DM. Smooth muscle and skeletal muscle myosins produce similar unitary forces and displacements in the laser trap. Biophys J 72: 1006–1021, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harridge SD, Bottinelli R, Canepari M, Pellegrino MA, Reggiani C, Esbjornsson M, Saltin B. Whole-muscle and single-fibre contractile properties and myosin heavy chain isoforms in humans. Pflügers Arch 432: 913–920, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He ZH, Bottinelli R, Pellegrino MA, Ferenczi MA, Reggiani C. ATP consumption and efficiency of human single muscle fibers with different myosin isoform composition. Biophys J 79: 945–961, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hilber K, Galler S. Mechanical properties and myosin heavy chain isoform composition of skinned skeletal muscle fibres from a human biopsy sample. Pflügers Arch 434: 551–558, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hilber K, Galler S, Gohlsch B, Pette D. Kinetic properties of myosin heavy chain isoforms in single fibers from human skeletal muscle. FEBS Lett 455: 267–270, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huxley AF. Muscle structure and theories of contraction. Prog Biophys Biophys Chem 7: 255–318, 1957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hvid LG, Ortenblad N, Aagaard P, Kjaer M, Suetta C. Effects of ageing on single muscle fibre contractile function following short-term immobilisation. J Physiol 589: 4745–4757, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawai M, Saeki Y, Zhao Y. Crossbridge scheme and the kinetic constants of elementary steps deduced from chemically skinned papillary and trabecular muscles of the ferret. Circ Res 73: 35–50, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kinsey ST, Locke BR, Dillaman RM. Molecules in motion: influences of diffusion on metabolic structure and function in skeletal muscle. J Exp Biol 214: 263–274, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krivickas LS, Dorer DJ, Ochala J, Frontera WR. Relationship between force and size in human single muscle fibres. Exp Physiol 96: 539–547, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krivickas LS, Suh D, Wilkins J, Hughes VA, Roubenoff R, Frontera WR. Age- and gender-related differences in maximum shortening velocity of skeletal muscle fibers. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 80: 447–455, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larsson L, Moss RL. Maximum velocity of shortening in relation to myosin isoform composition in single fibres from human skeletal muscles. J Physiol 472: 595–614, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levine S, Kaiser L, Leferovich J, Tikunov B. Cellular adaptations in the diaphragm in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 337: 1799–1806, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewalle A, Steffen W, Stevenson O, Ouyang Z, Sleep J. Single-molecule measurement of the stiffness of the rigor myosin head. Biophys J 94: 2160–2169, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lexell J, Taylor CC. Variability in muscle fibre areas in whole human quadriceps muscle. How much and why? Acta Physiol Scand 136: 561–568, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li M, Larsson L. Force-generating capacity of human myosin isoforms extracted from single muscle fibre segments. J Physiol 588: 5105–5114, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Linari M, Bottinelli R, Pellegrino MA, Reconditi M, Reggiani C, Lombardi V. The mechanism of the force response to stretch in human skinned muscle fibres with different myosin isoforms. J Physiol 554: 335–352, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luden N, Minchev K, Hayes E, Louis E, Trappe T, Trappe S. Human vastus lateralis and soleus muscles display divergent cellular contractile properties. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R1593–R1598, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mateja RD, Greaser ML, de Tombe PP. Impact of titin isoform on length dependent activation and cross-bridge cycling kinetics in rat skeletal muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta 1833: 804–811, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McKillop DF, Fortune NS, Ranatunga KW, Geeves MA. The influence of 2,3-butanedione 2-monoxime (BDM) on the interaction between actin and myosin in solution and in skinned muscle fibres. J Muscle Res Cell Motil 15: 309–318, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mijailovich SM, Fredberg JJ, Butler JP. On the theory of muscle contraction: filament extensibility and the development of isometric force and stiffness. Biophys J 71: 1475–1484, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller MS, Bedrin NG, Callahan DM, Previs MJ, Jennings ME 2nd Ades PA, Maughan DW, Palmer BM, Toth MJ. Age-related slowing of myosin actin cross-bridge kinetics is sex specific and predicts decrements in whole skeletal muscle performance in humans. J Appl Physiol 115: 1004–1014, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller MS, VanBuren P, LeWinter MM, Braddock JM, Ades PA, Maughan DW, Palmer BM, Toth MJ. Chronic heart failure decreases cross-bridge kinetics in single skeletal muscle fibres from humans. J Physiol 588: 4039–4053, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller MS, VanBuren P, LeWinter MM, Lecker SH, Selby DE, Palmer BM, Maughan DW, Ades PA, Toth MJ. Mechanisms underlying skeletal muscle weakness in human heart failure: alterations in single fiber myosin protein content and function. Circ Heart Fail 2: 700–706, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moisescu DG. Kinetics of reaction in calcium-activated skinned muscle fibres. Nature 262: 610–613, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moisescu DG, Thieleczek R. Calcium and strontium concentration changes within skinned muscle preparations following a change in the external bathing solution. J Physiol 275: 241–262, 1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mulieri LA, Barnes W, Leavitt BJ, Ittleman FP, LeWinter MM, Alpert NR, Maughan DW. Alterations of myocardial dynamic stiffness implicating abnormal crossbridge function in human mitral regurgitation heart failure. Circ Res 90: 66–72, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Palmer BM, Suzuki T, Wang Y, Barnes WD, Miller MS, Maughan DW. Two-state model of acto-myosin attachment-detachment predicts C-process of sinusoidal analysis. Biophys J 93: 760–769, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Palmer BM, Tanner BC, Toth MJ, Miller MS. An inverse power-law distribution of molecular bond lifetimes predicts fractional derivative viscoelasticity in biological tissue. Biophys J 104: 2540–2552, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palmiter KA, Tyska MJ, Dupuis DE, Alpert NR, Warshaw DM. Kinetic differences at the single molecule level account for the functional diversity of rabbit cardiac myosin isoforms. J Physiol 519: 669–678, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pansarasa O, Rinaldi C, Parente V, Miotti D, Capodaglio P, Bottinelli R. Resistance training of long duration modulates force and unloaded shortening velocity of single muscle fibres of young women. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 19: e290–e300, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paoli A, Pacelli QF, Cancellara P, Toniolo L, Moro T, Canato M, Miotti D, Reggiani C. Myosin isoforms and contractile properties of single fibers of human latissimus dorsi muscle. BioMed Res Int 2013: 249398, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pathare N, Walter GA, Stevens JE, Yang Z, Okerke E, Gibbs JD, Esterhai JL, Scarborough MT, Gibbs CP, Sweeney HL, Vandenborne K. Changes in inorganic phosphate and force production in human skeletal muscle after cast immobilization. J Appl Physiol 98: 307–314, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pellegrino MA, Canepari M, Rossi R, D'Antona G, Reggiani C, Bottinelli R. Orthologous myosin isoforms and scaling of shortening velocity with body size in mouse, rat, rabbit and human muscles. J Physiol 546: 677–689, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pernus F, Erzen I. Fibre size, atrophy, and hypertrophy factors in vastus lateralis muscle from 18- to 29-year-old men. J Neurol Sci 121: 194–202, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reid KF, Fielding RA. Skeletal muscle power: a critical determinant of physical functioning in older adults. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 40: 4–12, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rome LC, Funke RP, Alexander RM, Lutz G, Aldridge H, Scott F, Freadman M. Why animals have different muscle fibre types. Nature 335: 824–827, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schiaffino S, Reggiani C. Fiber types in mammalian skeletal muscles. Physiol Rev 91: 1447–1531, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Slinker BK, Glantz SA. Multiple regression for physiological data analysis: the problem of multicollinearity. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 249: R1–R12, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stienen GJ, Kiers JL, Bottinelli R, Reggiani C. Myofibrillar ATPase activity in skinned human skeletal muscle fibres: fibre type and temperature dependence. J Physiol 493: 299–307, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stienen GJ, Roosemalen MC, Wilson MG, Elzinga G. Depression of force by phosphate in skinned skeletal muscle fibers of the frog. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 259: C349–C357, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sugiura S, Kobayakawa N, Fujita H, Yamashita H, Momomura S, Chaen S, Omata M, Sugi H. Comparison of unitary displacements and forces between 2 cardiac myosin isoforms by the optical trap technique: molecular basis for cardiac adaptation. Circ Res 82: 1029–1034, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Szentesi P, Zaremba R, van Mechelen W, Stienen GJ. ATP utilization for calcium uptake and force production in different types of human skeletal muscle fibres. J Physiol 531: 393–403, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tanner BC, Daniel TL, Regnier M. Sarcomere lattice geometry influences cooperative myosin binding in muscle. PLoS Comput Biol 3: e115, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thorstensson A, Larsson L, Tesch P, Karlsson J. Muscle strength and fiber composition in athletes and sedentary men. Med Sci Sports 9: 26–30, 1977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tirrell TF, Cook MS, Carr JA, Lin E, Ward SR, Lieber RL. Human skeletal muscle biochemical diversity. J Exp Biol 215: 2551–2559, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Toth MJ, Miller MS, Callahan DM, Sweeny AP, Nunez I, Grunberg SM, Der-Torossian H, Couch ME, Dittus K. Molecular mechanisms underlying skeletal muscle weakness in human cancer: reduced myosin-actin cross-bridge formation and kinetics. J Appl Physiol 114: 858–868, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Trappe S, Gallagher P, Harber M, Carrithers J, Fluckey J, Trappe T. Single muscle fibre contractile properties in young and old men and women. J Physiol 552: 47–58, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Uttenweiler D, Weber C, Fink RH. Mathematical modeling and fluorescence imaging to study the Ca2+ turnover in skinned muscle fibers. Biophys J 74: 1640–1653, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang G, Kawai M. Force generation and phosphate release steps in skinned rabbit soleus slow-twitch muscle fibers. Biophys J 73: 878–894, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Widrick JJ, Stelzer JE, Shoepe TC, Garner DP. Functional properties of human muscle fibers after short-term resistance exercise training. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 283: R408–R416, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yu F, Hedstrom M, Cristea A, Dalen N, Larsson L. Effects of ageing and gender on contractile properties in human skeletal muscle and single fibres. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 190: 229–241, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhao Y, Kawai M. The effect of the lattice spacing change on cross-bridge kinetics in chemically skinned rabbit psoas muscle fibers. II. Elementary steps affected by the spacing change. Biophys J 64: 197–210, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]