Abstract

The α-carbonic anhydrases (CAs, EC 4.2.1.1) show catalytic versatility acting as esterases with carboxylic, sulfonic, and phosphate esters. Here we prove by kinetic, spectroscopic, and MS studies that they also possess thioesterase activity with a dithiocarbamate ester as a substrate (PhSO2NHCSSMe). Its CA-mediated hydrolysis leads to benzenesulfonamide, methyl mercaptan, and COS. The CA thioesterase activity may be useful for designing prodrug enzyme inhibitors, whereas some CA isoforms may use this activity for modulating physiologic/pathologic processes, which are possibly amenable to drug discovery of agents with multiple mechanisms of action.

Keywords: Carbonic anhydrase, thioesterase, inhibitors, prodrugs

The carbonic anhydrases are metalloenzymes, which catalyze the interconversion between CO2 and bicarbonate, being involved in a multitude of physiologic and pathologic processes.1−6 Many enzymes belonging to the six genetic families known so far (the α-, β-, γ-, δ-, ζ-, and η-classes) are in fact drug targets, with some of their inhibitors in clinical use for decades.1−3,7−9

In addition to the physiologic reaction, the α-CAs, which are found in many organisms, from bacteria to humans,1−4 also show catalytic versatility, acting as esterases with carboxylic, sulfonic, and phosphate esters,10−14 as well as hydration properties toward substrates that are structurally similar to CO2, such as COS, CS2, cyanamide, and aldehydes.15−18 It is not known whether other such catalyzed reactions, apart CO2 hydration, have some physiologic relevance.

It is interesting to note that at this moment the possible thioesterase activity of the CAs has not been investigated, although considering the similar mechanism of reaction for the hydrolysis of carboxylic and thiocarboxylic esters, such an activity may be expected. Indeed, recently we have discovered that coumarins are a new class of CA inhibitors (CAIs).19−21 Their mechanism of inhibition is distinct of that of all classes of CAIs investigated earlier, as they are first hydrolyzed (at the lactone ring) to 2-hydroxy-cinnamic acids, through the esterase activity of the enzyme. The phenolic carboxylic acid formed in this way then binds at the entrance of the active site cavity.19 Such a type of inhibition was then observed also for monocyclic lactones as well as for the thiocoumarins and thiolactones.20,21 On the basis of such data we had the suspicion that CAs may also possess thioesterase activity. Here we demonstrate this new catalytic activity of the α-CAs by using as model enzyme of the bovine (b) and human (h) red cell CA (bCA, hCA II) as well as the Co(II)-substituted derivative, bCo(II)CA, which has an electronic spectrum highly sensitive to the environment around the Co(II) ion.22

The compound we used to demonstrate the esterase activity was the methyl phenylsulfonylcarbamodithioate (1), prepared as described in the Supporting Information (see also Scheme 1). The inhibition of the hCA II with compound 1 is shown in Figure 1, with benzenesulfonamide 3 as standard inhibitor.23−25

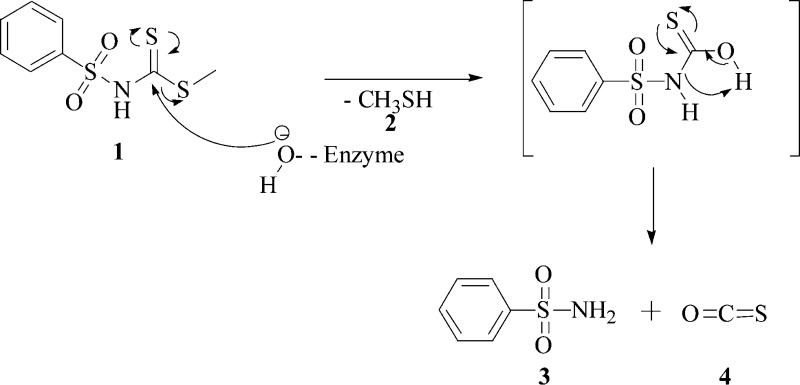

Scheme 1. Suggested Mechanism for Thioesterase Activity of hCA II on Dithiocarbamate Ester 1.

Figure 1.

Inhibition constant (Ki) change for methyl phenylsulfonylcarbamodithioate 1 versus time, incubated with hCA II for 1–18 h(s), blue; Ki change for 1 versus time in HEPES buffer (without enzyme), red. *Errors in the range of ±10 of the reported values, from three different stopped-flow assays.

A stopped-flow assay with CO2 as substrate has been employed to measure the inhibitory power of compounds 1 and 3.23 As seen from Figure 1, the dithiocarbamate ester 1 showed a time-dependent inhibition constant (Ki) against hCA II, which steeply varied with the time of incubation between the enzyme and compound 1. The Ki continued to decrease until an incubation period of 12 h was reached, suggesting that the compound undergoes a transformation in the presence of enzyme. It should be noted that compound 1 incubated in the same conditions with the buffer but without enzyme showed the same inhibition constant over time, suggesting that the hydrolytic process is indeed mediated by CA and not by other nucleophiles present in the buffer (Figure 1).

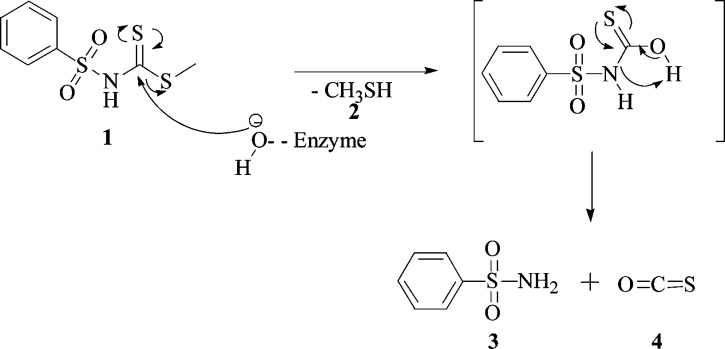

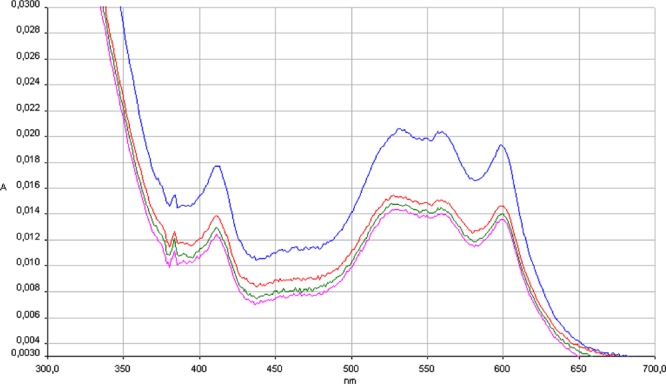

Figures 2 and 3 show the electronic spectra of bCo(II)CA complexed with benzenesulfonamide 3 (Figure 2) and compound 1 (Figure 3) versus time, respectively. We have chosen the dithiocarbamate ester 1 in order to eventually generate a primary aromatic sulfonamide by hydrolysis to its thioester moiety. It may be seen that the bCo(II)CAII has a typical electronic spectrum, with maxima at 520 and 560 nm, and the sulfonamide 3 adduct of the Co(II)-substituted enzyme is immediately formed, having again quite characteristic features and absorption maxima at 518 and 574 nm (Figure 2).17 These spectra are typical of Co(II) in tetrahedral geometry, as the water coordinated to the metal ion was substituted by the sulfonamidate anion of the inhibitor.22 It should be also noted that the spectrum of the Co(II)-substituted enzyme with the dithiocarbamate ester 1 is initially very similar to the spectra of pure bCo(II)CA shown in Figure 2. No initial changes of the spectrum are seen when 1 is added to the Co(II)-substituted enzyme (data not shown), but the spectra typical of an adduct of bCo(II)CA with a sulfonamide appear after 8 h of incubation of the enzyme and the thioester (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

bCo(II)CA (6 μM) in HEPES buffer (blue); bCo(II)CA with benzenesulfonamide 3 (1:2) (red); after 10 min (green); after 15 min (pink). Twenty nanomolar HEPES (pH 7.5) as buffer, and 20 mM Na2SO4 (for maintaining constant ionic strength) used in all experiments.

Figure 3.

bCo(II)CA (6 μM, blue line), in HEPES; bCo(II)CA with methyl phenylsulfonylcarbamodithioate 1 (1:2) (red); after 8 h (green); after 16 h (pink). In all experiments, 20 nM HEPES (pH 7.5) as buffer and 20 mM Na2SO4 were used.

The final evidence that the thioester 1 is hydrolyzed to benzenesulfonamide 3 and COS came from the mass spectra (MS) experiments shown in Figure 4. After incubation of compound 1 with hCA II for 16 h, the characteristic peak of COS was observed at 63.9, together with the benzenesulfonamide peak at 156 m/z (Figure 4). The peak of unreacted 1 was also observed at 246 m/z.

Figure 4.

Mass spectra (MS) analyses of methyl phenylsulfonylcarbamodithioate 1 (0.1 mM) incubated with hCA II (0.1 μM) for 16 h. (A) Negative ESI fragmentation of compound 1 to give phenylsulfonamide 3. (B) In positive ESI mode, COS+ is detected.

The proposed mechanism for the thioesterase activity of CA is shown in Scheme 1. The nucleophilic attack of the hydroxide ion bound to the Zn(II) (or Co(II) ions) from the enzyme active site to the C=S carbon atom of the thioester functionality gives a tetrahedral intermediate (not shown), which loses methyl mercaptan 2 and leads to the formation of a presumably unstable monothiocarbamic acid intermediate, which collapses to benzenesulfonamide 3 and COS 4.

It is worth mentioning that due to the particular substrate chosen, which by hydrolysis leads to benzenesulfonamide, the thioesterase activity of the enzyme is strongly inhibited by one of the reaction products, i.e., the primary sulfonamide. The reason why we chose this particular thioester was dictated by the fact that we wanted to use kinetics, electronic spectroscopy, and MS for demonstrating this new enzymatic activity of the CAs. Indeed, the spectra of the Co(II)-substituted CA with sulfonamides are highly characteristic, proving clearly the interaction between the inhibitor and the metal ion from the enzyme active site. In addition, the high resolution MS allowed us to evidence the formed products in the hydrolysis of thioester 1 mediated by CA, which prompted us to propose the reaction mechanism of the thioesterase reaction.

Thioesterases are abundant enzymes in all life kingdoms, being involved in crucial physiologic processes. There are 27 different clans of such enzymes, which hydrolyze the thioester bond between a carbonyl moiety and a sulfur atom.26 For 15 out of 27 such groups, the substrates are thioesters of coenzyme A (CoA), whereas two contain acyl carrier proteins (ACP), four have glutathione or its derivatives as substrates, one has ubiquitin, and two such enzyme families possess other diverse substrates.26,27 One important aspect of this enzyme superfamily is that they are not metalloenzymes except for one family, the hydroxyglutathione hydrolases (glyoxalases II), which are zinc enzymes with a metallo-β-lactamase fold.26 Indeed, in all other thioesterase clans known to date the thioester hydrolysis is achieved by a catalytic dyad/triad normally comprising a nucleophilic amino acid–histidine–acidic amino acid sequence. Some of the most common catalytic residues known are Asp-Gln-Thr; Cys-His-Asn, Asn-Arg; Ser-His-Asp, etc.26 In all cases in which the catalytic mechanism has been investigated, the nucleophile from the catalytic triad/dyad attacks the thioester bond, with formation in some cases of acyl-enzyme intermediates, whereas the remaining amino acids from the triad stabilize the collapsing tetrahedral intermediate.26 Hydroxyglutathione hydrolase has two Zn(II) ions at the active site coordinated by seven His and Asp residues and a bridging water molecule, which presumably acts as nucleophile in the thioesterase reaction. Thus, the CAs for which we have proved such an activity here are the only other thioesterases acting by means of a metal hydroxide mechanism, but in contrast to hydroxyglutathione hydrolase, they do not use dinuclear metal centers. Our main conclusion is thus that we prove that CAs belonging to the α-class possess significant thioesterase activity and act by a new mechanism of thioester hydrolysis compared to all other clans of thioesterases known so far. The metal hydroxide from the CA active site is the strong nucleophile able to attack the thiocarbonyl carbon atom, leading to the hydrolysis of the thioester functionality. It is unclear at this moment whether this new catalytic activity of the CAs may have physiologic significance, but considering the very high number of biologically crucial thioesters (e.g., the CoA esters, ACP esters, glutathione derivatives, etc.), this may not be excluded. In fact, very recently it has been reported that human fatty acid synthase possesses a thioesterase domain that can be targeted by small molecule inhibitors leading to relevant antitumor effects.27 As many α-CA isoforms are present in tumors,28−30 we cannot exclude that, in addition to their pH regulating effects, some CAs may use their thioesterase activity for modulating physiologic/pathologic processes, which might be amenable to drug discovery of antitumor agents with multiple mechanisms of action.30

Supporting Information Available

Synthesis and NMR/MS spectra of compound 1 and the experimental details for the kinetic, spectroscopic, and MS experiments. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

This research was financed by the EU FP7Marie Curie ITN project Dynano. We are grateful to Dr. Riccardo Romoli for his technical support with mass spectrometric experiments.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Supuran C. T. Carbonic anhydrases: novel therapeutic applications for inhibitors and activators. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2008, 7, 168–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alterio V.; Di Fiore A.; D’Ambrosio K.; Supuran C. T.; De Simone G. Multiple binding modes of inhibitors to carbonic anhydrases: how to design specific drugs targeting 15 different isoforms?. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 4421–4468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal M.; Boone C. D.; Kondeti B.; McKenna R. Structural annotation of human carbonic anhydrases. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2013, 28, 267–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supuran C. T. Structure-based drug discovery of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2012, 27, 759–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supuran C. T. Carbonic anhydrases: from biomedical applications of the inhibitors and activators to biotechnological use for CO2 capture. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2013, 28, 229–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neri D.; Supuran C. T. Interfering with pH regulation in tumours as a therapeutic strategy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2011, 10, 767–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Simone G.; Supuran C. T. (In)organic anions as carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2012, 111, 117–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harju A. K.; Bootorabi F.; Kuuslahti M.; Supuran C. T.; Parkkila S. Carbonic anhydrase III: a neglected isozyme is stepping into the limelight. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2013, 28, 231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alp C.; Maresca A.; Alp N. A.; Gültekin M. S.; Ekinci D.; Scozzafava A.; Supuran C. T. Secondary/tertiary benzenesulfonamides with inhibitory action against the cytosolic human carbonic anhydrase isoforms I and II. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2013, 28, 294–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocker Y.; Stone J. T. The catalytic versatility of erythrocyte carbonic anhydrase. The enzyme-catalyzed hydrolysis of para-nitrophenyl acetate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87, 5497–5498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çavdar H.; Ekinci D.; Talaz O.; Saraçoğlu N.; Şentürk M.; Supuran C. T. α-Carbonic anhydrases are sulfatases with cyclic diol monosulfate esters. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2012, 27, 148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazancıoğlu E. A.; Güney M.; Şentürk M.; Supuran C. T. Simple methanesulfonates are hydrolyzed by the sulfatase carbonic anhydrase activity. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2012, 27, 880–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti A.; Supuran C. T. Paraoxon, 4-nitrophenyl phosphate and acetate are substrates of α- but not of β-, γ- and ζ-carbonic anhydrases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 6208–6212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti A.; Scozzafava A.; Parkkila S.; Puccetti L.; De Simone G.; Supuran C. T. Investigations of the esterase, phosphatase, and sulfatase activities of the cytosolic mammalian carbonic anhydrase isoforms I, II, and XIII with 4-nitrophenyl esters as substrates. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 2267–2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeulders M. J.; Barends T. R.; Pol A.; Scherer A.; Zandvoort M. H.; Udvarhelyi A.; Khadem A. F.; Menzel A.; Hermans J.; Shoeman R. L.; Wessels H. J.; van den Heuvel L. P.; Russ L.; Schlichting I.; Jetten M. S.; Op den Camp H. J. Evolution of a new enzyme for carbon disulphide conversion by an acidothermophilic archaeon. Nature 2011, 478, 412–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa T.; Noguchi K.; Saito M.; Nagahata Y.; Kato H.; Ohtaki A.; Nakayama H.; Dohmae N.; Matsushita Y.; Odaka M.; Yohda M.; Nyunoya H.; Katayama H. Carbonyl sulfide hydrolase from Thiobacillus thioparus strain THI115 is one of the β-carbonic anhydrase family enzymes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 3818–3825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briganti F.; Mangani S.; Scozzafava A.; Vernaglione G.; Supuran C. T. Carbonic anhydrase catalyzes cyanamide hydration to urea: is it mimicking the physiological reaction?. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 1999, 4, 528–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocker Y.; Meany J. E. The catalytic versatility of carbonic anhydrase fro erythrocytes. The enzymatic catalyzed hydration of acetaldehyde. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87, 1809–1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maresca A.; Temperini C.; Vu H.; Pham N. B.; Poulsen S. A.; Scozzafava A.; Quinn R. J.; Supuran C. T. Non-zinc mediated inhibition of carbonic anhydrases: coumarins are a new class of suicide inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 3057–3062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maresca A.; Temperini C.; Pochet L.; Masereel B.; Scozzafava A.; Supuran C. T. Deciphering the mechanism of carbonic anhydrase inhibition with coumarins and thiocoumarins. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 335–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carta F.; Maresca A.; Scozzafava A.; Supuran C. T. Novel coumarins and 2-thioxo-coumarins as inhibitors of the tumor-associated carbonic anhydrases IX and XII. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 2266–2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertini I.; Luchinat C.; Scozzafava A. Interaction of cobalt-bovine carbonic anhydrase with the acetate ion. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1976, 452, 239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalifah R. J. The carbon dioxide hydration activity of carbonic anhydrase. J. Biol. Chem. 1971, 246, 2561–2573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briganti F.; Pierattelli R.; Scozzafava A.; Supuran C. T. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Part 37. Novel classes of isozyme I and II inhibitors and their mechanism of action. Kinetic and spectroscopic investigations on native and cobalt-substituted enzymes. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 1996, 31, 1001–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Abbate F.; Winum J. Y.; Potter B. V.; Casini A.; Montero J. L.; Scozzafava A.; Supuran C. T. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: X ray crystallographic structure of the adduct of human isozyme II with a EMATE, a dual inhibitor of carbonic anhydrases and steroid sulfatase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004, 14, 231–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantu D. C.; Chen Y.; Reilly P. J. Thioesterases: A new prespective based on their primary and tertiary structures. Protein Sci. 2010, 19, 1281–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fako V.; Wu X.; Pflug B.; Liu J. Y.; Zhang J. T. Repositioning proton pump inhibitors as anti-cancer drugs by targeting the thioesterase domain of human fatty acid synthase. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 10.1021/jm501543u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebbesen P.; Pettersen E. O.; Gorr T. A.; Jobst G.; Williams K.; Kienninger J.; Wenger R. H.; Pastorekova S.; Dubois L.; Lambin P.; Wouters B. G.; Supuran C. T.; Poellinger L.; Ratcliffe P.; Kanopka A.; Görlach A.; Gasmann M.; Harris A. L.; Maxwell P.; Scozzafava A. Taking advantage of tumor cell adaptations to hypoxia for developing new tumor markers and treatment strategies. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2009, 24 (S1), 1–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gieling R. G.; Parker C. A.; De Costa L. A.; Robertson N.; Harris A. L.; Stratford I. J.; Williams K. J. Inhibition of carbonic anhydrase activity modifies the toxicity of doxorubicin and melphalan in tumour cells in vitro. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2013, 28, 360–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Simone G.; Alterio V.; Supuran C. T. Exploiting the hydrophobic and hydrophilic binding sites for designing carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery 2013, 8, 793–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.