Abstract

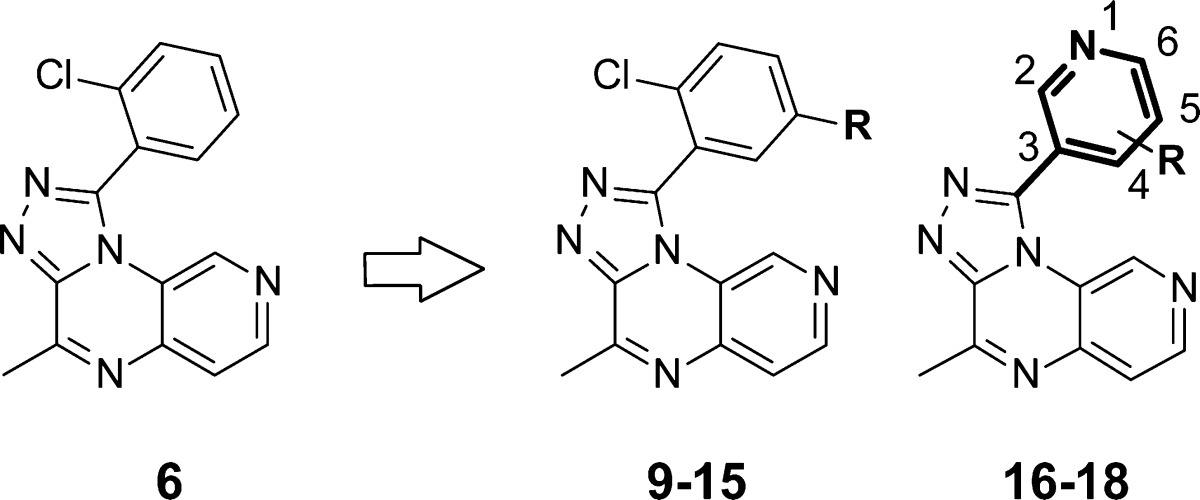

A novel series of pyrido[4,3-e][1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a]pyrazines is reported as potent PDE2/PDE10 inhibitors with drug-like properties. Selectivity for PDE2 was obtained by introducing a linear, lipophilic moiety on the meta-position of the phenyl ring pending from the triazole. The SAR and protein flexibility were explored with free energy perturbation calculations. Rat pharmacokinetic data and in vivo receptor occupancy data are given for two representative compounds 6 and 12.

Keywords: Pyrido[4,3-e][1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a]pyrazine; PDE2 inhibitor; phosphodiesterase 2 inhibitor; tricycle; selective

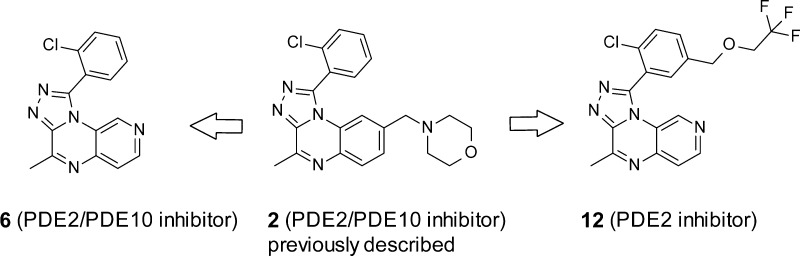

Phosphodiesterases (PDEs) control the degradation of second messengers cAMP and cGMP. Eleven PDE subfamilies with distinct tissue distribution and varying selectivity for cAMP and cGMP have been identified.1 PDE2 is a dual-substrate enzyme, stimulated by cGMP and degrading both cAMP and cGMP.2 It is the most abundant PDE subtype in the hippocampus, a brain structure playing an important role in cognitive processes.3 Cyclic nucleotides are key signaling molecules implicated in the regulation of neuronal plasticity and memory.4−6 PDE2 inhibition elevates levels of these molecules and could exert procognitive activity and restore hippocampal function, which are altered in disease states such as schizophrenia or Alzheimer’s disease.7 However, the lack of selective and brain penetrant PDE2 inhibitors has hampered validation of this hypothesis in animal models. We have previously reported the optimization of the poorly soluble HTS hit 1 into molecule 2 with combined PDE2/PDE10 activity (Scheme 1). This early lead 2 was valuable for studying CNS effects of PDE2/PDE10 inhibition in vivo.8 More recently, we have described optimization of 2 via structure-based drug design to 3, a selective and brain penetrant PDE2 inhibitor.9

Scheme 1. Optimization of HTS Hit 1 into Lead Compound 3.

Ten percent HPβCD, pH 2.

Twenty percent HPβCD, pH 3.6–3.8.

Percent metabolized after incubating 1 μM solution 15 min with rLM or hLM at 37 °C.

The poor solubility of 1 was addressed in 2 and 3 by substituting the benzo-fused ring of the triazoloquinoxaline core with basic aliphatic amines. While solubility was greatly increased in 2 and 3, both compounds had poor metabolic stability (Scheme 1). In parallel introduction of pyridyl-like nitrogens in the benzene ring of the quinoxaline moiety was explored, as these could increase solubility while maintaining high ligand efficiency (LE) and good overall physicochemical and ADME properties.

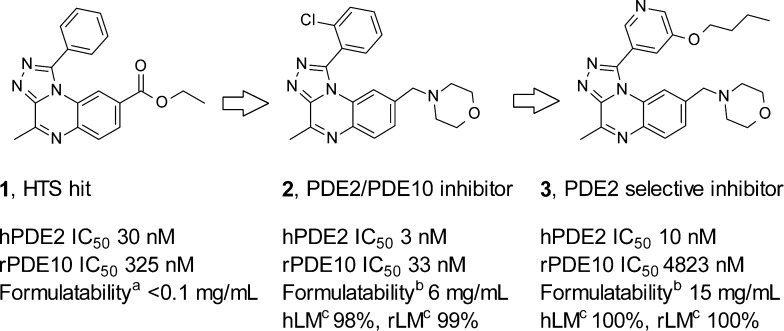

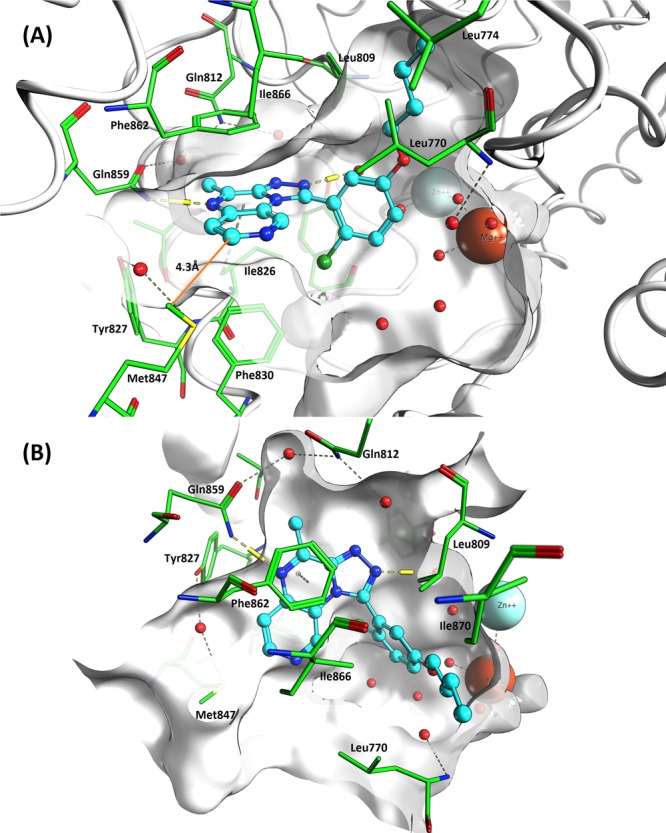

Prior to synthesis, the four possible isomers bearing a nitrogen atom in the quinoxaline benzene ring (5–8, Chart 1) were docked into the PDE2 protein using the SP mode of Glide10 with default protein preparation. A docking protocol with enhanced ligand sampling reproduced the crystal structure binding mode of four different PDE2–inhibitor complexes with good accuracy (see Supporting Information (SI)). Docking helped prioritize 5, 6, and 8, but 7 was not targeted as it presents an unfavorable interaction between the pyridyl nitrogen and Met847 in PDE2. The proximity of this atom to Met847 is revealed by the short 4.3 Å distance between the closest heavy atoms of 9 and Met847 (Figure 1, vide infra). For baseline comparison the [1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a]quinoxaline 4 was also synthesized.

Chart 1. Triazoloquinoxaline 4 and Aza-Analogues 5-8.

Figure 1.

Molecule 9 (cyan color) docked into PDE2A crystal structure solved with 3 (PDB 4D08). Viewed from the entrance to the active site (A) and top down (B). Important amino acids are highlighted in green, and catalytic Zn2+ and Mg2+ ions are shown, along with active site water molecules (red spheres). Distance between 9 and Met847 highlighted in orange.

Of the three isomers prepared, 5 (IC50 = 15 nM) and 6 (IC50 = 29 nM) showed comparable inhibitory potency for PDE2 to the carbon analogue 4 (IC50 = 14 nM), whereas isomer 8 was 13-fold less potent (IC50 = 190 nM).11 Formulatability of 5 (<0.5 mg/mL with 20% HPβCD at pH 2) was similar to that of the HTS hit 1; however, the regioisomeric 6 was significantly more soluble (>1 mM in buffer at pH 7.4 and 4 mg/mL with 20% HPβCD at pH 3.9), which can be attributed to the higher solvent exposure and hydrogen bonding capability of the pyridine-like nitrogen in 6. This is also reflected by their respective experimental pKa values (5, pKa = 1.0; 6, pKa = 2.7). Hence, 6 was selected for further optimization.

The in vitro selectivity data of 6 versus other PDE’s along with in vitro ADME and physicochemical data are summarized in Table 1. Molecule 6 inhibited PDE2 and PDE10, respectively, with an IC50 value of 29 and 480 nM. This is in line with the previously reported values for compound 2. In addition 6 did not show significant inhibition of a panel of CYP450 enzymes (CYP1A2, 2C9, 2D6, 2C19, and 3A4). The compound was also inactive up to a concentration of 125 μg/mL in a bacterial mutagenicity assay (AMESII). The in vitro metabolic stability of 6 was greatly improved both in human (hLM) and rat (rLM) liver microsomes when compared to 2.

Table 1. In Vitro PDE Selectivity Profile, in Vitro ADME, and Physicochemical Properties of 6.

| PDE

selectivity profile |

ADME

and physicochemical properties |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| subtype | IC50 (nM) | ||

| hPDE1A | >10000 | hLMa | 7 |

| hPDE2A | 29 | rLMa | 13 |

| hPDE3B | >10000 | kinetic solubility at pH 7.4 (μM)b |

>1000 |

| hPDE4D | 5890 | pKac | 2.7 |

| hPDE5A | >10000 | formulatability (mg/mL)d | 4 |

| hPDE6AB | >10000 | CYP450 (>50% inhibition @ 5 μM)e |

none |

| hPDE7A | >10000 | AMESIIf | negative |

| hPDE9A | >10000 | ||

| rPDE10A | 480 | ||

| hPDE11A | 6920 | ||

Percent metabolized after incubating 1 μM solution 15 min with rLM or hLM at 37 °C.

Compound concentration after 4 h incubation in buffer pH 7.4.

Determined by potentiometric titration (25 °C).

20% HPβCD at pH > 3.5.

Enzymatic inhibition of CYP1A2, 2C9, 2D6, 2C19, and 3A4.

Adaptation of the colorimetric AMESII Mutagenicity Assay kit from Xenometric. Compound concentration 125 μg/mL.

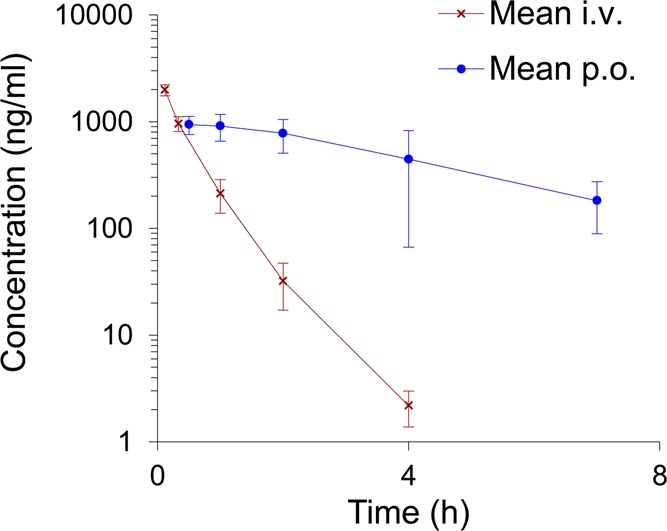

The PK properties of compound 6 were studied in rats after 2.5 mg/kg i.v. and 10 mg/kg p.o. administration (Table 2). After i.v. administration, a rapid clearance was observed (t1/2 = 0.47 h), which was not expected based on the in vitro metabolic stability in rLM (Table 1). Interestingly, 6 showed much slower clearance after p.o. administration (t1/2 = 2.36 h), resulting in good bioavailability and a maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) of 997 ng/mL.

Table 2. Pharmacokinetic Properties of 6 in Ratsa.

| mean i.v. | s.d. | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Co (ng/mL) | 3021 | ± | 388 |

| t1/2 (h) | 0.47 | ± | 0.08 |

| Vdz (L/kg) | 1.61 | ± | 0.55 |

| Vdss (L/kg) | 1.02 | ± | 0.10 |

| Cl (mL/min/kg) | 38.7 | ± | 6.5 |

| AUC0-inf (ng·h/mL) | 1042 | ± | 184 |

| mean p.o. | s.d. | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 997 | ± | 241 |

| tmax (h) | 1.17 | ± | 0.76 |

| t1/2 (h) | 2.36 | ± | 0.46 |

| AUC0-inf (ng·h/mL) | 4229 | ± | 1892 |

| bioavailability (%) | 100 |

Male Sprague–Dawley rat fed (n = 3 per time point); i.v., 2.5 mg/kg; p.o., 10 mg/kg.

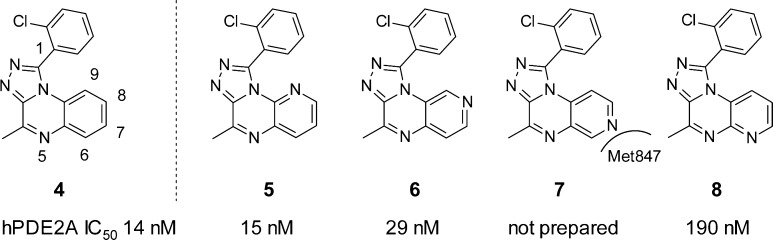

The good in vitro profile and acceptable PK properties of 6 prompted us to explore the possibility of increasing the selectivity of this chemical series versus PDE10. Introducing a lipophilic group to the meta-position of the phenyl on the triazole ring can induce an open Leu770 protein conformation allowing the ligand to access a hydrophobic roof pocket, increasing selectivity versus PDE10.9 Hence a focused set of analogues 9–18 bearing an additional substituent on the 2-chlorophenyl group in 6 was synthesized, and their in vitro potency and selectivity were determined (Table 3).

Table 3. In Vitro PDE2 and PDE10 Inhibition and Metabolic Stability Data for Compounds 6 and 9–18.

| R | hPDE2 IC50 (nM)a | rPDE10 IC50 (nM)a | rLMb | hLMb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | H | 29 | 480 | 13 | 7 |

| 9 | On-Bu | 6 | 5500 | 98 | 34 |

| 10 | O(CH2)2OMe | 95 | 9120 | 18 | 5 |

| 11 | CH2On-Pr | 21 | 3890 | 98 | 78 |

| 12 | CH2OCH2CF3 | 3 | 2450 | 77 | 12 |

| 13 | CH2Oi-Pr | 10 | 6030 | 98 | 57 |

| 14 | morpholine | 310 | >10000 | 53 | 14 |

| 15 | OCF3 | 150 | 8910 | 11 | 3 |

| 16 | 5-Cl | 5750 | n.m. | n.m. | n.m. |

| 17 | 4-Me | 2450 | n.m. | n.m. | n.m. |

| 18 | 5-On-Bu | 54 | 3800 | 46 | 6 |

Average value of at least two independent experiments.

Percent metabolized after incubating 1 μM solution 15 min with rLM or hLM at 37 °C.

Analogues having a meta-substituted phenyl (9–15) or pyridyl (18) on the pyrido[4,3-e][1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a]pyrazine core displayed increased PDE2 selectivity versus PDE10. For instance, introduction of a n-butoxy group as in 9 resulted in a very potent PDE2 inhibitor with 917-fold selectivity over PDE10. Docking of 9 in the active site of PDE2 (Figure 1) confirmed a similar binding mode as seen in the X-ray structure of 3 (PDB 4D08)9 and also that of a similar tricyclic molecule binding to PDE10 (PDB 3SNI).12 The molecule sits in the hydrophobic clamp between Phe862 and Phe830 and forms the typical H-bond interaction with conserved Gln859. As seen in the previously reported series,9 the triazolo ring forms two water mediated H-bonds to Tyr655 and Gln812. The n-butoxy group binds in the lipophilic pocket formed by hydrophobic residues Leu770, Leu809, Ile866, and Ile870. The close proximity of Met847 to the ligand at the site entrance can be seen.

The binding mode of 9 helps to rationalize the observed SAR. The PDE2 activity of 2-methoxyethoxy derivative 10 is 16-fold lower than for 9, suggesting that polar moieties in the chain are not preferred in the lipophilic roof pocket. The morpholine in 14 is also detrimental for activity likely due to the polarity and suboptimal steric fit. Shifting the ether to the benzylic position as in 11–13 is allowed, with 12 being the most potent selective PDE2 inhibitor identified in this exploration (PDE2 IC50 = 3 nM, PDE10 IC50 = 2450 nM). Interestingly, the trifluoromethyl group in 15 results in a 5-fold decrease in potency (IC50 = 150 nM) when compared to 6, which may be due to an orthogonal orientation of this group. Pyridyls with small substituents, 16 and 17, were significantly lower in activity. Combination of the n-butoxy group in 9 with the distal pyridyl reduced PDE2 activity: molecule 18 was 9-fold less potent than 9. Of note is that, similar to 6, analogues 9–18 displayed high selectivity over other tested PDEs (see SI).

This exploration and our previous work9 reveal an interesting SAR originating from the phenyl/pyridyl group, its substitution, orientation, and ability to access the Leu770 lipophilic roof pocket. Induced binding and dynamic effects are not easily studied with conventional docking approaches. Therefore, to investigate these effects more sophisticated modeling based on FEP+ free energy calculations were employed (see SI for details and ΔG0 values).13,14 Seven compounds (6, 9, 10, 12, 15, 16, and 17) were studied covering a range of activity and substitution patterns while having sufficient similarity to permit reliable structural perturbations between pairs of molecules. The computational results had good agreement with experimental values (R2 = 0.79, mean unsigned error 0.54 kcal/mol) suggesting the approach captures the molecular details of the ligand enzyme interactions.

Compounds 9 and 12 were correctly predicted to be the most potent inhibitors with approximately equivalent predicted binding free energies. Compounds 16 and 17 were also predicted to be nearly equipotent but with the least favorable binding free energies. These two compounds were more mobile during the simulations, indicating a less tight fit into the binding site. Compounds 10 and 15 were predicted to have nearly equipotent binding free energies and were correctly ranked with intermediate level of potency. Hence, the more hydrophilic linear side chain in the 5-position of 10 as well as the smaller trifluoromethoxy group of 15 produce weaker inhibitors compared to the more lipophilic chain of, e.g., 9. The binding free energy for 6 deviated most from experiment being underpredicted by ca. 2 kcal/mol. This is understandable as the unsubstituted 2-chlorophenyl binds optimally to a different PDE2 protein conformation compared to that used to start this set of FEP calculations (see SI for further discussion). Molecular dynamics (MD) calculations also shed further light on the conformational flexibility of Leu770 depending on the bound ligand structure. We found that on a simulation time scale of 30 ns, ligands with a large, linear side chain in the phenyl ring 5-position induce a more open form of the lipophilic roof pocket, while for ligands with no 5-substituent the crucial Leu770 dihedral angle exhibits higher flexibility (see SI for details). Given these promising results we are further studying the FEP+ approach for the design of PDE2 inhibitors.

Unfortunately, the most potent compounds 9, 12, and 13 were metabolically unstable when tested in vitro against hLM and mainly rLM. An improvement in rat metabolic stability profile was obtained for pyridyl analogue 18. Prediction of human CYP3A4, 2D6, and 2C9 related metabolism using StarDrop 515 and analysis of physicochemical properties as well as structural elements associated with metabolism revealed a nice correlation between predicted compound site liabilities and in vitro metabolism with hLM. Especially aliphatic chains pending from the distal phenyl (Table 3, R-group) were predicted to introduce metabolic liabilities, with alkoxymethylene groups correctly being predicted inferior to alkoxy groups (see SI for a comparison between 6, 9, 13, and 18). The fact that increasing polarity (as in 18) or fluorination of the side chain (as in 12 and 15) effectively improves hLM metabolism in vitro supports these predictions.

Compounds 6, 9–12, and 18 were assessed for their potential to cross the blood–brain barrier in rats after 10 mg/kg s.c. administration. All tested compounds showed good formulatability with 10 to 20% HPβCD at pH > 3.5. Brain exposure for 9–12 and 18 was lower compared to 6; nevertheless, the brain concentration for these compounds after 1 h administration was in the range of 370–895 ng/g with high brain free fractions and brain/plasma ratios (Table 4).

Table 4. Total Brain Level Comparison between 6, 9–12, and 18a,b.

| cmpd | 6 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fu, brain (rat)c | >0.30 | 0.026 | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.10 | >0.30 |

| brain 1 h (ng/g) | 2730 | 807 | 801 | 895 | 370 | 789 |

| B/P 1 h | 0.65 | 0.69 | 0.44 | 0.98 | 1.1 | 0.61 |

Male Sprague–Dawley rat fed (n = 2 per time point) 10 mg/kg s.c.

Compounds were formulated with 20% HPβCD at pH 3.5–4.

Estimated unbound drug fraction to rat brain homogenates after 5 h incubation at 37 °C using a Rapid Equilibrium Dialysis device.

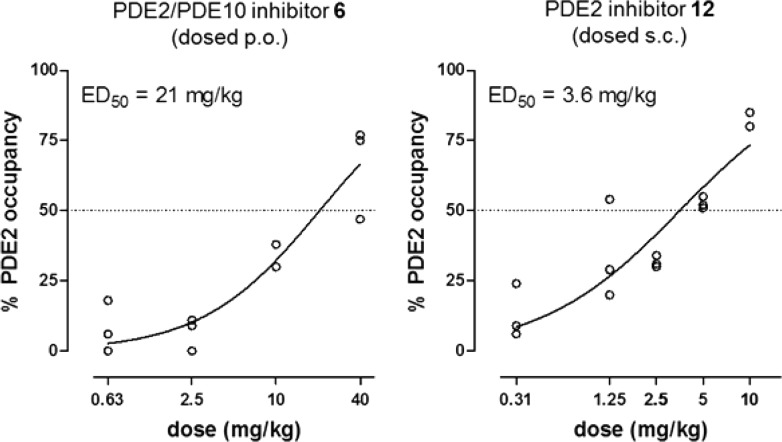

Target engagement of pyrido[4,3-e][1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a]pyrazines 6, 12, and 18 was evaluated in an in vivo occupancy study in rats using tritiated 3 as radioactive tracer (10 μCi i.v.). In this experiment, MP-10 (2.5 mg/kg s.c.),16 a potent and selective PDE10 inhibitor was predosed since it was found to greatly increase the signal-to-noise ratio of the tracer. This can be explained by the fact that PDE10 inhibition increases intracellular cGMP, which is known to activate PDE2 through its GAF domain.17 Using this protocol we could demonstrate that the PDE2/PDE10 inhibitor 6 occupies PDE2 with an ED50 of 21 mg/kg (Figure 2) after p.o. administration. For the highly selective PDE2 inhibitor 12 no occupancy was seen up to 10 mg/kg after p.o. dosing, most probably due to poor oral bioavailability. However, when 12 was dosed s.c., high PDE2 occupancy was observed, with an ED50 of 3.6 mg/kg. Interestingly compound 18, despite its good potency and brain exposure, gave a poor occupancy of 23% at the highest tested dose of 10 mg/kg s.c. (see SI).

Figure 2.

In vivo dose/PDE2 occupancy graphs for compounds 6 and 12 (rats, n = 3/dose).

In summary we have described the design, synthesis, and pharmacological characterization of a novel series of selective and brain penetrant PDE2 inhibitors. Also, we have shown a promising application of free energy perturbation and molecular dynamics calculations to predict the SAR of the Leu770 lipophilic roof pocket. Two representative compounds from this chemical class have been evaluated in vivo. Compared to our previous reports these molecules offer an alternative tricyclic scaffold with improved metabolic stability in some cases permitting target engagement by oral administration. More specifically, compound 6, which is orally bioavailable, occupied PDE2 with an ED50 of 21 mg/kg, a significant improvement over previously reported compound 2. In addition the highly selective PDE2 inhibitor 12 showed high occupancy after s.c. administration with an ED50 of 3.6 mg/kg. These compounds contribute valuable probes to further study the role of PDE2 and PDE10 in vivo across a variety of CNS disorders.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ilse Lenaerts for performing the occupancy experiments. We also thank Geert Pille for measuring the pKa of 5 and 6. Finally, we thank Dr. Gerhard Gross for performing and interpreting the StarDrop metabolic site predictions.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AUC0-inf

area under the curve until infinite time

- Co

zero concentration

- B/P

brain-to-plasma ratio

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- cGMP

cyclic guanosine monophosphate

- Cl

clearance

- FEP

free energy perturbation

- HPβCD

(2-hydroxypropyl)-beta-cyclodextrin [128446-35-5]

- hLM

human liver microsomes

- i.v.

intravenous

- n.m.

not measured

- PDE

phosphodiesterase

- p.o.

per os (oral)

- s.c.

subcutaneous

- s.d.

standard deviation

- rLM

rat liver microsomes

- t1/2

half-life

- tmax

time at maximum concentration

- Vdss

steady-state volume of distribution

- Vdz

apparent volume of distribution

Supporting Information Available

Computational docking, FEP and Molecular Dynamics calculation protocols, protocols for measuring inhibition of PDEs in vitro, selectivity data for 9–15 and 18, in vivo occupancy protocols and occupancy data for 18, CYP3A4 metabolism predictions for 6, 9, 13, and 18, and the experimental details of the synthesis of key intermediates and compounds 6 and 9–18. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Francis S. H.; Blount M. A.; Corbin J. D. Mammalian cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: molecular mechanisms and physiological functions. Physiol. Rev. 2011, 91, 651–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosman G. J.; Martins T. J.; Sonnenburg W. K.; Beavo J. A.; Ferguson K.; Loughney K. Isolation and characterization of human cDNAs encoding a cGMP-stimulated 3′,5′-cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase. Gene 1997, 191, 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakics V.; Karran E. H.; Boess F. G. Quantitative comparison of phosphodiesterase mRNA distribution in human brain and peripheral tissues. Neuropharmacology 2010, 59, 367–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez L.; Breitenbucher J. G. PDE2 inhibition: potential for the treatment of cognitive disorders. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 6522–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt C. J. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors as potential cognition enhancing agents. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2010, 10, 222–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson T. M.; Sher E. The role of phosphodiesterases in hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Neuropharmacology 2013, 74, 86–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurice D. H.; Ke H.; Ahmad F.; Wang Y.; Chung J.; Manganiello V. C. Advances in targeting cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2014, 13, 290–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrés J.-I.; Buijnsters P.; De Angelis M.; Langlois X.; Rombouts F.; Trabanco A. A.; Vanhoof G. Discovery of a new series of [1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalines as dual phosphodiesterase 2/phosphodiesterase 10 (PDE2/PDE10) inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 785–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buijnsters P.; Andrés J.-I.; De Angelis M.; Langlois X.; Rombouts F.; Sanderson W.; Tresadern G.; Ritchie A.; Trabanco A.; Vanhoof G.; Van Roosbroeck Y. Structure-based design of a potent, selective, and brain penetrating PDE2 inhibitor with demonstrated target engagement. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 1049–1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesner R. A.; Banks J. L.; Murphy R. B.; Halgren T. A.; Klicic J. J.; Mainz D. T.; Repasky M. P.; Knoll E. H.; Shelley M.; Perry J. K.; Shaw D. E.; Francis P.; Shenkin P. S. Glide: A new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 1. Method and assessment of docking accuracy. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 1739–1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Synthetic protocols are provided as SI. Compounds 6 and 7 have been previously reported in:Joergensen M.; Bruun A. T.; Rasmussen L. K.. Preparation of pyridine compounds useful for treating neurological and psychiatric disorders. PCT Int. Appl., WO 2013034761 A1, 2013.

- Malamas M. S.; Ni Y.; Erdei J.; Stange H.; Schindler R.; Lankau H.-J.; Grunwald C.; Fan K. Y.; Parris K.; Langen B.; Egerland U.; Hage T.; Marquis K. L.; Grauer S.; Brennan J.; Navarra R.; Graf R.; Harrison B. L.; Robichaud A.; Kronbach T.; Pangalos M. N.; Hoefgen N.; Brandon N. J. Highly potent, selective, and orally active phosphodiesterase 10A inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 7621–7638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen W. L. Efficient drug lead discovery and optimization. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 724–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chodera J. D.; Mobley D. L.; Shirts M. R.; Dixon R. W.; Branson K.; Pande V. S. Alchemical free energy methods for drug discovery: Progress and challenges. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2011, 21, 150–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StarDrop Optibrium, Ltd.: Cambridge, U.K.; http://www.optibrium.com (accessed Dec 19, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Verhoest P. R.; Chapin D. S.; Corman M.; Fonseca K.; Harms J. F.; Hou X.; Marr E. S.; Menniti F. S.; Nelson F.; O’Connor R.; Pandit J.; Proulx-Lafrance C.; Schmidt A. W.; Schmidt C. J.; Suiciak J. A.; Liras S. Discovery of a novel class of phosphodiesterase 10A inhibitors and identification of clinical candidate 2-[4-(1-methyl-4-pyridin-4-yl-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)-phenoxymethyl]-quinoline (PF-2545920) for the treatment of schizophrenia. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 5188–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoraghi R.; Corbin J. D.; Francis S. H. Properties and functions of GAF domains in cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases and other proteins. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004, 65, 267–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.