Abstract

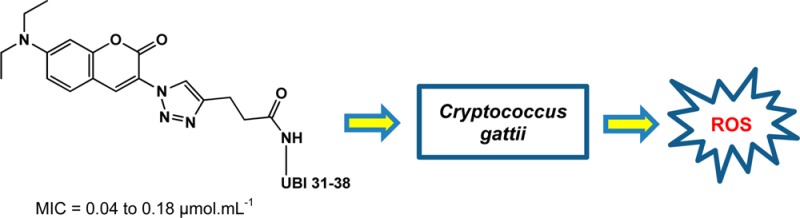

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are currently being investigated as potential sources of novel therapeutics against an increasing number of microorganisms resistant to conventional antibiotics. The conjugation of an AMP to other bioactive compounds is an interesting approach for the development of new derivatives with increased antimicrobial efficiency and broader spectra of action. In this work, the synthesis of a new peptide–coumarin conjugate via copper(I)-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition is described. The conjugate was assayed for in vitro cytotoxicity and displayed antifungal activity against Cryptococcus gattii and Cryptococcus neoformans. Additionally, the conjugate exhibited increased antifungal efficacy when compared with the individual peptide, coumarin, or triazole moieties. Treatment of C. gattii with the peptide–coumarin conjugate enhanced the production of reactive oxygen species, suggesting that the oxidative burst plays an important role in the mechanism of action of the conjugate.

Keywords: Antimicrobial peptide, copper(I)-catalyzed azide−alkyne cycloaddition, coumarin, cryptococcosis, reactive oxygen species

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are small molecular weight proteins with antimicrobial activity against bacteria, viruses, and fungi.1 AMPs are currently being investigated as potential sources of novel therapeutic antimicrobial agents because of their broad-spectrum activity and low susceptibility for developing resistance.2

Ubiquicidin (UBI) is an antimicrobial peptide, which was first isolated from murine macrophages and then found at low concentrations (as a first line of defense) inside human airway epithelial cells, activated macrophages, and in human colon mucosa. UBI is a cationic peptide consisting of 59 amino acid residues. It is not expected to be immunogenic to humans since it is of human origin.3 UBI 1–59 and some of its fragments have been shown to be microbicidal against a broad spectrum of pathogens. Of particular interest is the fragment UBI 31–38 (Figure 1), which is relatively small, easily synthesized, and exhibits antibacterial activity toward methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus.4

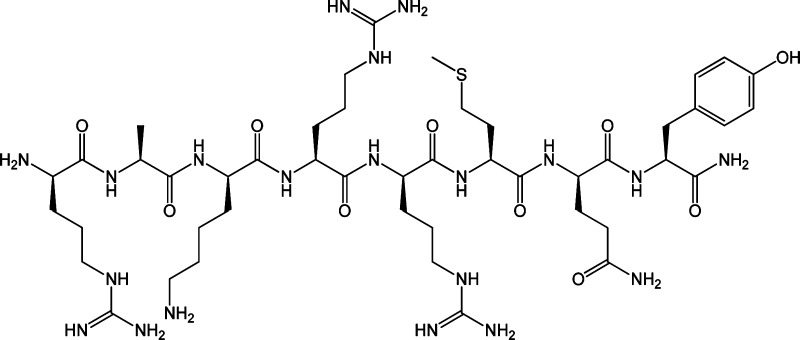

Figure 1.

Structure of UBI 31–38.

Peptides open up new perspectives in drug design by providing an entire range of highly selective and nontoxic pharmaceuticals. With growing applications of their synthesis and bioactivity, considerable attention has been focused on the research of peptide-based derivatives.5

Coumarins form an important class of benzopyrones, which are found in nature. Many coumarins and their derivatives possess antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer properties.6 Research on coumarin compounds as antifungal agents has shown that structural modification of the coumarin skeleton (i.e., the benzene ring, lactone ring, or both) results in derivatives, which possess potent antifungal activity when compared to clinically used antifungal drugs.7 Therefore, numerous efforts have focused on the development of coumarins as potential drugs.8

The copper(I)-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) reaction has previously been employed as a means of orthogonal modification of peptides.9,10 CuAAC results in the formation of 1,4-disubstituted 1,2,3-triazoles, which are bioisosteres of the amide bond. This reaction may be used for the synthesis of peptidomimetics with improved medicinal chemistry properties and for the attachment of peptide molecules to other biologically active compounds.11

Cryptococcus neoformans and Cryptococcus gattii are the pathogenic yeasts of cryptococcosis. Immunocompromised patients are more frequently infected with C. neoformans, while C. gattii has emerged as an important cause of infection in healthy individuals. This disease involves pulmonary and cutaneous sites, but the most severe manifestation occurs in the central nervous system, causing severe meningoencephalitis. A small number of antimycotic drugs are available to treat this disease, with polyenes and azoles being the most commonly employed against cryptococcosis.12,13 However, nephrotoxicity has been described as a chronic adverse effect of amphotericin B,14 and a large number of fluconazole-resistant strains of C. gattii and C. neoformans have been reported.15,16

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) can damage DNA, RNA, proteins, and lipids, resulting in cell death when the level of ROS exceeds an organism’s detoxification and repair capabilities.17 For instance, some bactericidal antibiotics have been reported to kill bacteria by stimulating the generation of ROS.18 However, several intracellular mechanisms of action could be involved, and it is yet to be clarified which of these are responsible.19

Given the current difficulties in treating cryptococcosis and, furthermore, the antimicrobial properties shown by UBI 31–38 and many coumarins, we proposed the synthesis of the novel peptide-coumarin conjugate 4. The results of this work are reported herein.

The C-terminal amidated peptide UBI 31–38 (RAKRRMQY) was synthesized by stepwise solid phase peptide synthesis using the Fmoc strategy20 on a Rink amide resin. The alkyne-decorated peptidyl resin 1 was prepared by coupling 4-pentynoic acid to the peptide UBI 31–38 during the solid-phase synthesis. For the purpose of antimicrobial evaluation, compound 2 was obtained from cleavage of the alkyne-decorated peptidyl resin followed by HPLC purification.

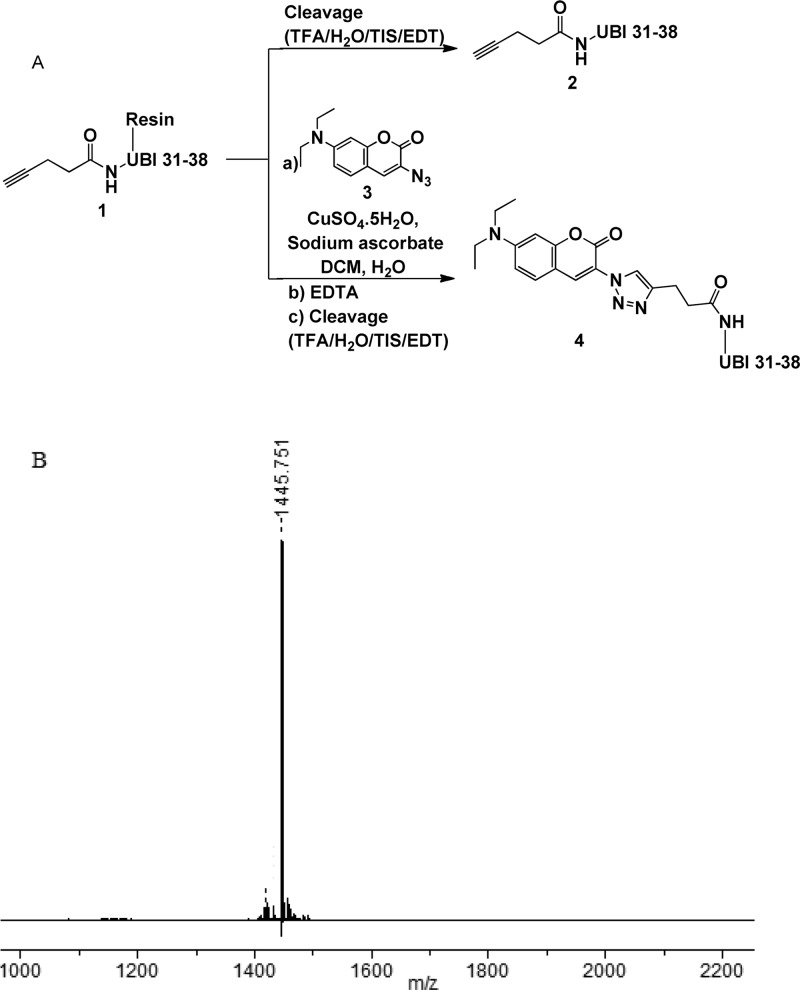

The peptide–coumarin conjugate 4 was synthesized via CuAAC,21 as represented in Figure 2A. The alkyne-decorated peptidyl resin 1 was directly employed in the CuAAC to avoid undesirable reactions involving the side chains of amino acid residues. The 3-azido-7-diethylaminocoumarin 3 was synthesized as previously reported.22 The first attempt to obtain 4 was unsuccessful; mass spectral data of the product revealed the presence of undesirable copper, possibly forming complexes with amino acids through chelation (data not shown). To overcome this problem, an additional step of resin washing with a solution of 50% EDTA and 25% NH4OH (1:1) was included in the workup procedure. After cleavage from the resin and purification by HPLC, the product was obtained with high purity, as illustrated by the mass spectrum shown in Figure 2B.

Figure 2.

(A) Synthesis of the alkyne-modified peptide 2 and the peptide–coumarin conjugate 4. Reagents and conditions: (a) 3.0 equiv of 3, 0.3 equiv of copper(II) sulfate, 0.6 equiv of sodium ascorbate, 1 mL of DCM, 1 mL of water, rt, 48 h; (b) washing step with 50% EDTA and 25% NH4OH (1:1); (c) cleavage with TFA/H2O/TIS/EDT 94.0/2.5/2.5/1.0, 240 rpm, rt, 3 h. (B) MS spectrum of 4 after HPLC purification (m/z calculated for MH+: 1445.77).

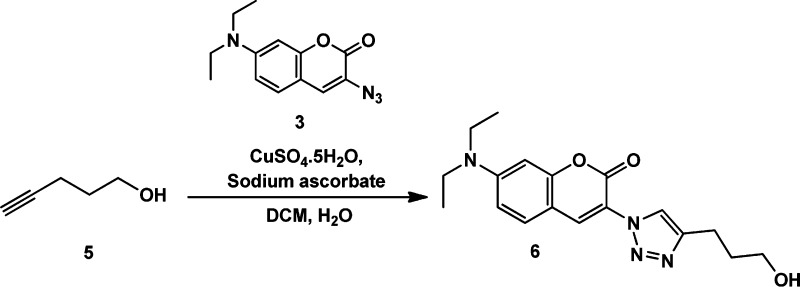

3-Azido-7-diethylaminocoumarin 3 was also conjugated to commercial 4-pentyn-1-ol via classic CuAAC21 reaction to yield the novel compound 6 (Figure 3). This coumarin-triazole hybrid was prepared in order to investigate the role of the triazole ring in the antimicrobial activity.

Figure 3.

Synthesis of the coumarin–triazole derivative 6. Reagents and conditions: 1.0 equiv of 3, 0.3 equiv of copper(II) sulfate, 0.6 equiv of sodium ascorbate, 1 mL of DCM, 1 mL of water, rt, overnight.

All synthesized compounds were characterized and screened for their antifungal activities against a set of strains of C. gattii and C. neoformans. The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of UBI 31–38, the alkyne-decorated peptide 2, the 3-azido-7-diethylaminocoumarin 3, the peptide–coumarin conjugate 4, the coumarin–triazole 6, and fluconazole (FCZ) were determined by the antifungal microdilution susceptibility standard test proposed by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute M27-A3 method.23 The results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. MIC Values (μmol·mL–1) for the Synthesized Compounds against Strains of C. gattii and C. neoformans.

| MIC

for the compounds | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fungi | UBI 31–38 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | FCZ | |

| C. gattii strain | ICB 181 | >0.23 | >0.22 | >0.99 | 0.09 | >0.75 | 0.05 |

| L135/03 | >0.23 | >0.22 | >0.99 | 0.04 | >0.75 | 0.05 | |

| 196L/03 | >0.23 | >0.22 | >0.99 | 0.04 | >0.75 | 0.10 | |

| 547/OTT | >0.23 | >0.22 | >0.99 | 0.04 | >0.75 | 0.10 | |

| ATCC 32608 | >0.23 | >0.22 | >0.99 | 0.09 | >0.75 | 0.05 | |

| ATCC 24065 | >0.23 | >0.22 | >0.99 | 0.18 | >0.75 | 0.01 | |

| 1913ER | >0.23 | >0.22 | >0.99 | 0.18 | >0.75 | 0.05 | |

| L27/01 | >0.23 | >0.22 | >0.99 | 0.04 | >0.75 | 0.10 | |

| L28/02 | >0.23 | >0.22 | >0.99 | 0.09 | >0.75 | 0.10 | |

| LMM 818 | >0.23 | >0.22 | >0.99 | 0.18 | >0.75 | 0.10 | |

| L24/01 | >0.23 | >0.22 | >0.99 | 0.09 | >0.75 | 0.05 | |

| 23/10993 | >0.23 | >0.22 | >0.99 | 0.18 | >0.75 | 0.05 | |

| 29/10893 | >0.23 | >0.22 | >0.99 | 0.09 | >0.75 | 0.03 | |

| L27/01Fa | >0.23 | >0.22 | >0.99 | 0.09 | >0.75 | 0.42 | |

| C. neoformans strain | ATCC 96806 | >0.23 | >0.22 | >0.99 | 0.09 | >0.75 | 0.15 |

| ATCC 62066 | >0.23 | >0.22 | >0.99 | 0.09 | >0.75 | 0.03 | |

| ATCC 24067 | >0.23 | >0.22 | >0.99 | 0.09 | >0.75 | 0.02 | |

| ATCC 28957 | >0.23 | >0.22 | >0.99 | 0.09 | >0.75 | 0.003 | |

L27/01F is a fluconazole-resistant strain of C. gattii.24

From the results, it is clear that the peptide–coumarin conjugate 4 exhibited moderate to excellent antifungal activities against the tested strains and gave comparable MIC values (0.04–0.18 μmol·mL–1) to the standard drug FCZ (MIC = 0.003–0.15 μmol·mL–1). In addition, the conjugate 4 efficiently inhibited the growth of a fluconazole-resistant strain of C. gattii (L27/01F) at a concentration of 0.09 μmol·mL–1. UBI 31–38 and the derivatives 2, 3, and 6 showed low activities against the strains of C. gattii and C. neoformans, with MIC values of >0.23, >0.22, >0.99, and >0.75 μmol·mL–1, respectively.

Notably, the peptide–coumarin conjugate 4 exhibited better antifungal activities than its precursors 2 and 3, as well as the peptide UBI 31–38, indicating that the association between the peptide and coumarin using a triazole linker is beneficial to antimicrobial efficacy. Some authors have also reported that a coumarin backbone in combination with various nitrogen-containing heterocycles (e.g., azetidine, thiazolidine, thiazole, etc.) significantly increased the antimicrobial efficacy and broadened the antimicrobial spectrum of activity of these compounds.8

Although triazole drugs are extensively used as antifungal agents in clinics,25 the combination of the triazole moiety with other pharmacophores is being investigated in order to develop new types of antifungal drugs, which might exert new mechanisms of action and be effective against multidrug-resistant fungi.26 In the current work, the importance of the peptide in maintaining the antifungal activity of the conjugate 4 has been demonstrated. The absence of UBI 31–38 from the triazole derivative (compound 6) resulted in a dramatic decrease in inhibition of the growth of the tested strains (MIC >0.75 μmol·mL–1) compared to 4, suggesting that the peptide, coumarin, and triazole moieties have a synergistic effect.

The cytotoxicity of the peptide–coumarin conjugate 4 was assessed in a noncancerous human cell line (lung fibroblast CCD-Lu ATCC CCL-210) using the methylthiazoltetrazolium (MTT) assay. Briefly, cells were exposed to the conjugate 4 at concentrations ranging from 0.02 to 0.21 μmol·mL–1, and cell survival was determined. The results demonstrated that 4 was nontoxic (cell viability > 95%) up to a concentration of 0.21 μg·mL–1, which is greater than the highest MIC value obtained for this compound, indicating a moderate to high selectivity index for anticryptococcal activity over cytotoxicity.

Since most of the AMPs are cationic and amphiphilic, the mode of action of these molecules is thought to involve the initial electrostatic interaction with a negatively charged surface of microorganisms, followed by insertion into the lipid bilayer by means of hydrophobic interactions. As a consequence, transient permeability of membranes and leakage of cellular constituents may occur, leading to cell lysis.1 Preferential binding of AMPs to pathogens over mammalian cells may be explained by the segregation of lipids with negatively charged headgroups into the inner leaflet of the membranes in mammalian cells.27 Additionally, some studies have demonstrated that the presence of cholesterol in eukaryotic membranes reduces AMP binding and suppresses the disruption of lipid bilayer structure by AMPs.28,29

AMPs with antifungal activities can bind to fungal-specific negatively charged constituents of the cell wall, such as mannoproteins or interact with specific receptors on the plasma membrane.30 In the case of C. gattii and C. neoformans, which are known to produce a polysaccharide capsule,31,32 we hypothesized that a specific interaction of the AMP with this negatively charged component and/or cellular membrane may take place. Although membrane permeabilization by AMPs is an essential step in the killing of fungi, certain antifungal peptides exert their antimicrobial action through formation of reactive oxygen species.33−37 Oxidative burst also plays a crucial role in the antifungal activity of some drugs, such as itraconazole and amphotericin B against C. gattii.38 On the basis of these reports, the production of endogenous ROS in the fungus C. gattii induced by the peptide–coumarin conjugate 4 and by the coumarin–triazole derivative 6 was investigated using fluorometric assays.38 The measured fluorescence intensity was directly proportional to the accumulation of ROS.

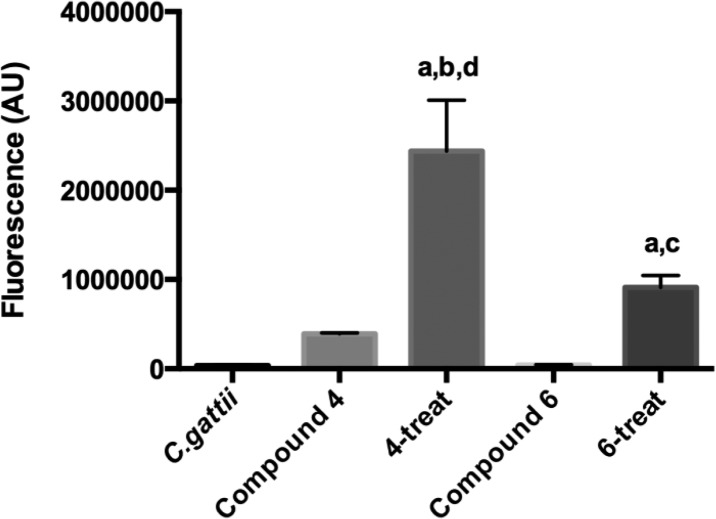

ROS levels were measured in C. gattii cells from the strain ATCC 32608 (control group) and also in the peptide–conjugate 4 and the coumarin–triazole derivative 6, in order to obtain baseline levels. Subsequently, the intracellular ROS production after treatment of C. gattii with the MIC values of the compounds 4 and 6 was also measured. The results are shown in Figure 4 and expressed in arbitrary units (AU) of fluorescence.

Figure 4.

Amounts of ROS detected in C. gattii cells (ATCC 32608), compound 4, C. gattii cells treated with 4 (4-treat), compound 6, and C. gattii cells treated with 6 (6-treat). “a” indicates a statistically significant difference between the group and C. gattii. “b” indicates a statistically significant difference between compound 4-treated cells and compound 4. “c” indicates a statistically significant difference between compound 6-treated cells and compound 6. “d” indicates a statistically significant difference between the two treatments (compound 4- and 6-treatment). Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism version 6. The statistical comparisons were performed using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test at a global significance of 95%. The Bonferroni significance correction was adopted for pairwise comparisons.

The treatment of C. gattii with the compounds 4 and 6 increased the ROS levels compared with the control group or individual compounds. The highest ROS level was reached for the peptide–coumarin conjugate 4, which exhibited the strongest antifungal activity among the synthesized compounds. Although the compound 4 has been shown to be able to produce ROS alone, maybe as a result of an autocatalytic process, the amount of ROS measured in this case was significantly lower than that observed in compound 4-treated cells. These results suggest that, for the compounds 4 and 6, a correlation between the induction of ROS production and antifungal activity is present.

A valuable synthetic strategy for the N-terminal modification of the peptide UBI 31–38 through CuAAC is presented in this work. The peptide–coumarin conjugate 4 was successfully prepared by coupling the fully protected alkyne-decorated peptidyl resin 1 to the 3-azido-7-diethylaminocoumarin 3. The novel conjugate 4 exhibited antimicrobial activity against C. gattii and C. neoformans, including a fluconazole-resistant strain of C. gattii, at a concentration range of 0.04 to 0.18 μmol·mL–1. In addition, results of a cytotoxicity assay demonstrated that the conjugate 4 was nontoxic up to a concentration of 0.21 μg·mL–1, indicating a moderate to high selectivity index for anticryptococcal activity over cytotoxicity. UBI 31–38, 3-azido-7-diethylaminocoumarin 3, and the coumarin–triazole derivative 6 administered individually exhibited lower activities against the assayed strains, suggesting that the antifungal activity of 4 may be due to different properties of this compound, which act synergistically. Electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions of the peptide moiety with the polysaccharide capsule and cellular membrane of the fungi, as well as the induction of endogenous ROS production, may have important roles in the antifungal activity of 4. Further studies to elucidate the detailed mechanism of action of the conjugate 4 against C. gattii and C. neoformans are underway. These will hopefully contribute to the design and development of new antifungal agents.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- AMP

antimicrobial peptide

- AU

arbitrary units

- CuAAC

copper(I)-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition

- DCM

dichloromethane

- EDT

1,2-ethanedithiol

- EDTA

ethylene-diaminetetraacetic acid

- equiv

equivalent

- FCZ

fluconazole

- Fmoc

N-9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- MIC

minimum inhibitory concentration

- MS

mass spectrum

- MTT

methylthiazoltetrazolium

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- rpm

rotations per minute

- rt

room temperature

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- TIS

triisopropylsilane

- UBI

ubiquicidin

Supporting Information Available

Chemicals, general experimental methods, procedures for synthesis, inoculum preparation, determination of MIC, cytotoxicity assay, measurement of ROS, and spectral data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors.

The authors wish to thank CAPES, CNPq, and Fapemig for financial support. We further thank Pró-Reitoria de Pesquisa (UFMG) for the financial aid to publish the results.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Izadpanah A.; Gallo R. L. Antimicrobial peptides. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2005, 52 (3), 381–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo M.-D.; Won H.-S.; Kim J.-H.; Mishig-Ochir T.; Lee B.-J. Antimicrobial peptides for therapeutic applications: a review. Molecules 2012, 17 (10), 12276–12286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiemstra P. S.; van den Barselaar M. T.; Roest M.; Nibbering P. H.; van Furth R. Ubiquicidin, a novel murine microbicidal protein present in the cytosolic fraction of macrophages. J. Leukocyte Biol. 1999, 66 (3), 423–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer C.; Bogaards S. J. P.; Wulferink M.; Velders M. P.; Welling M. M. Synthetic peptides derived from human antimicrobial peptide ubiquicidin accumulate at sites of infections and eradicate (multi-drug resistant) Staphylococcus aureus in mice. Peptides 2006, 27 (11), 2585–2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suhas R.; Chandrashekar S.; Gowda D. C. Synthesis of uriedo and thiouriedo derivatives of peptide conjugated heterocycles - A new class of promising antimicrobials. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 48, 179–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rifai A. a. A.; Ayoub M. T.; Shakya A. K.; Abu Safieh K. A.; Mubarak M. S. Synthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of some new coumarin derivatives. Med. Chem. Res. 2012, 21 (4), 468–476. [Google Scholar]

- Peng X.-M.; Damu G. L. V.; Zhou C.-H. Current developments of coumarin compounds in medicinal chemistry. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19 (21), 3884–3930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y.; Zhou C.-H. Synthesis and evaluation of a class of new coumarin triazole derivatives as potential antimicrobial agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21 (3), 956–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagasia R.; Holub J. M.; Bollinger M.; Kirshenbaum K.; Finn M. G. Peptide cyclization and cyclodimerization by Cu-I-mediated azide-alkyne cycloaddition. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74 (8), 2964–2974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuaad A. A. H. A.; Azmi F.; Skwarczynski M.; Toth I. Peptide conjugation via CuAAC ‘click’ chemistry. Molecules 2013, 18 (11), 13148–13174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angell Y. L.; Burgess K. Peptidomimetics via copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloadditions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36 (10), 1674–1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chayakulkeeree M.; Perfect J. R. Cryptococcosis. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 2006, 20 (3), 507–+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullo F. P.; Rossi S. A.; Sardi J. D. O.; Teodoro V. L. I.; Mendes-Giannini M. J. S.; Fusco-Almeida A. M. Cryptococcosis: epidemiology, fungal resistance, and new alternatives for treatment. Eur. J. Clini. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013, 32 (11), 1377–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laniado-Laborin R.; Noemi Cabrales-Vargas M. Amphotericin B: side effects and toxicity. Revista Iberoamericana De Micologia 2009, 26 (4), 223–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma A.; Kwon-Chung K. J. Heteroresistance of Cryptococcus gattii to fluconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54 (6), 2303–2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazumi T.; Pfaller M. A.; Messer S. A.; Houston A. K.; Boyken L.; Hollis R. J.; Furuta I.; Jones R. N. Characterization of heteroresistance to fluconazole among clinical isolates of Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41 (1), 267–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brynildsen M. P.; Winkler J. A.; Spina C. S.; MacDonald I. C.; Collins J. J. Potentiating antibacterial activity by predictably enhancing endogenous microbial ROS production. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31 (2), 160–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohanski M. A.; Dwyer D. J.; Hayete B.; Lawrence C. A.; Collins J. J. A common mechanism of cellular death induced by bactericidal antibiotics. Cell 2007, 130 (5), 797–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright G. D.; Hung D. T.; Helmann J. D. How antibiotics kill bacteria: new models needed?. Nat. Med. 2013, 19 (5), 544–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan W.; White P.. Fmoc Solid Phase Peptide Synthesis: A Practical Approach; Oxford University Press: New York, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rostovtsev V. V.; Green L. G.; Fokin V. V.; Sharpless K. B. A stepwise Huisgen cycloaddition process: Copper(I)-catalyzed regioselective ″ligation″ of azides and terminal alkynes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41 (14), 2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumar K.; Xie F.; Cash B. M.; Long S.; Barnhill H. N.; Wang Q. A fluorogenic 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction of 3-azidocoumarins and acetylenes. Org. Lett. 2004, 6 (24), 4603–4606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLSI. Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts. M27-A3, 3rd ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Santos J.; Holanda R.; Frases S.; Bravim M.; Araujo G.; Santos P.; Costa M.; Ribeiro M.; Ferreira G.; Baltazar L.; Miranda A.; Oliveira D.; Santos C.; Fontes A.; Gouveia L.; Resende-Stoianoff M.; Abrahão J.; Teixeira A.; Paixão T.; Souza D.; Santos D. Fluconazole alters the polysaccharide capsule of Cryptococcus gattii and leads to distinct behaviors in murine cryptococcosis. PLoS One 2014, 9, e112669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lass-Floerl C. Triazole antifungal agents in invasive fungal infections: A comparative review. Drugs 2011, 71 (18), 2405–2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C. H.; Wang Y. Recent Researches in Triazole Compounds as Medicinal Drugs. Curr. Med. Chem. 2012, 19 (2), 239–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zasloff M. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature 2002, 415 (6870), 389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glukhov E.; Stark M.; Burrows L. L.; Deber C. M. Basis for selectivity of cationic antimicrobial peptides for bacterial versus mammalian membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280 (40), 33960–33967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki K.; Sugishita K.; Fujii N.; Miyajima K. Molecular-basis for membrane selectivity of an antimicrobial peptide, Magainin-2. Biochemistry 1995, 34 (10), 3423–3429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupetti A.; Welling M. M.; Pauwels E. K. J.; Nibbering P. H. Detection of fungal infections using radiolabeled antifungal agents. Current Drug Targets 2005, 6 (8), 945–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester S. J.; Malik R.; Bartlett K. H.; Duncan C. G. Cryptococcosis: update and emergence of Cryptococcus gattii. Veterinary Clin. Pathol. 2011, 40 (1), 4–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose I.; Reese A. J.; Ory J. J.; Janbon G.; Doering T. L. A yeast under cover: the capsule of Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryotic Cell 2003, 2 (4), 655–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupetti A.; Paulusma-Annema A.; Senesi S.; Campa M.; van Dissel J. T.; Nibbering P. H. Internal Thiols and reactive oxygen species in candidacidal activity exerted by an N-terminal peptide of human lactoferrin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46 (6), 1634–1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho J.; Lee D. G. The antimicrobial peptide arenicin-1 promotes generation of reactive oxygen species and induction of apoptosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1810 (12), 1246–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C.; Lee D. G. Melittin induces apoptotic features in Candida albicans. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 394 (1), 170–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh K.; Dowd S. Histatins: antimicrobial peptides with therapeutic potential. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2004, 56 (3), 285–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang B.; Hwang J.-S.; Lee J.; Kim J.-K.; Kim S. R.; Kim Y.; Lee D. G. Induction of yeast apoptosis by an antimicrobial peptide, Papiliocin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 408 (1), 89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira G. F.; Baltazar L. d. M.; Alves Santos J. R.; Monteiro A. S.; de Oliveira Fraga L. A.; Resende-Stoianoff M. A.; Santos D. A. The role of oxidative and nitrosative bursts caused by azoles and amphotericin B against the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus gattii. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2013, 68 (8), 1801–1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.