Abstract

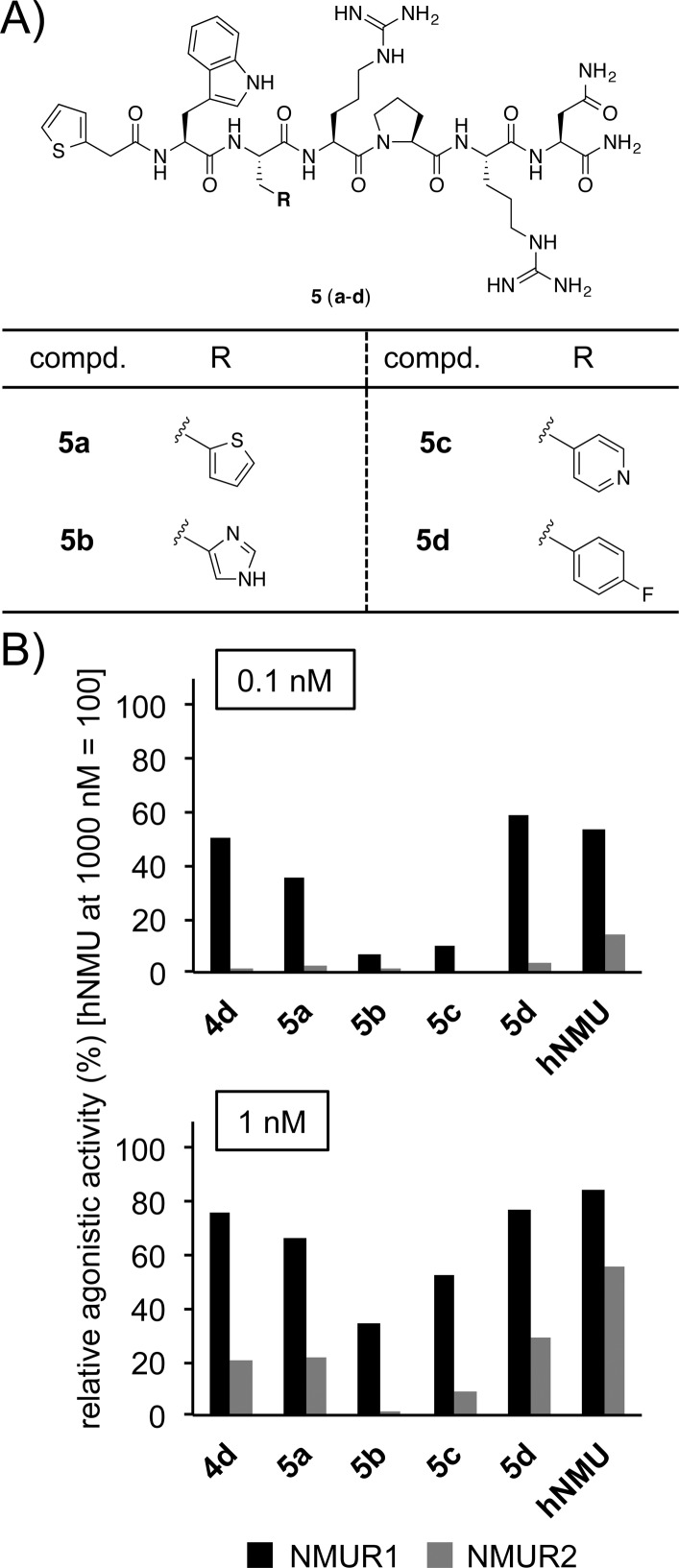

Neuromedin U (NMU) and S (NMS) display various physiological activities, including an anorexigenic effect, and share a common C-terminal heptapeptide-amide sequence that is necessary to activate two NMU receptors (NMUR1 and NMUR2). On the basis of this knowledge, we recently developed hexapeptide agonists 2 and 3, which are highly selective to human NMUR1 and NMUR2, respectively. However, the agonists are still less potent than the endogenous ligand, hNMU. Therefore, we performed an additional structure–activity relationship study, which led to the identification of the more potent hexapeptide 5d that exhibits similar NMUR1-agonistic activity as compared to hNMU. Additionally, we studied the stability of synthesized agonists, including 5d, in rat serum, and identified two major biodegradation sites: Phe2-Arg3 and Arg5-Asn6. The latter was more predominantly cleaved than the former. Moreover, substitution with 4-fluorophenylalanine, as in 5d, enhanced the metabolic stability at Phe2-Arg3. These results provide important information to guide the development of practical hNMU agonists.

Keywords: Agonist, biodegradation site, neuromedin U, neuromedin U receptor, peptide

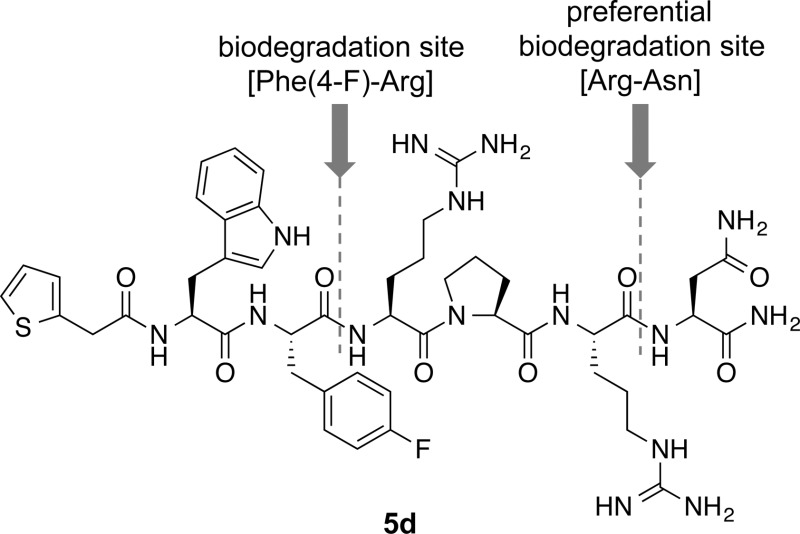

Neuromedin U (NMU)1 and S (NMS)2 exhibit various biological behaviors, including appetite suppression,3,4 reduction in body weight,5 regulation of energy homeostasis,6 increase in body temperature,5 and regulation of glucose homeostasis.7 Recently, two-types of neuromedin U receptors (NMUR1 and NMUR2) were shown to be involved in the anorexigenic activity of peripherally administrated human NMU (hNMU) conjugated with high molecular weight poly(ethylene)glycol (PEG) or human serum albumin (HSA).8,9 Accordingly, the pursuit of NMU-based drug development to treat obesity is considered promising. Mammalian NMU and NMS share the C-terminal heptapeptide-amide 1a (H-Phe0-Leu1-Phe2-Arg3-Pro4-Arg5-Asn6-NH2, Figure 1A), which activates both receptors.1,2 In 1995, Hashimoto et al. reported that N-terminal succinylated 1a, which was synthesized as an aminopeptidase-resistant derivative, showed potent contractile activity toward chicken crop smooth muscle expressing avian NMU receptors.10 Recently, we performed a structure–activity relationship (SAR) study of heptapeptide 1a to develop receptor-selective agonists using cultured cells expressing human NMU receptors. As shown in Figure 1A, the results indicated that (1) the α-amino group at the N-terminal Phe0 residue in 1a was not important for the agonistic activity because the N-terminal des-amino derivative, 1b, had similar activity to 1a; (2) N-terminal 3-pyridylpropionyl (1c) and 3-cyclohexylpropionyl (1d) structures were important for selective agonistic activities toward NMUR1 and NMUR2, respectively; (3) bulky aromatic amino acid residues, e.g., Trp and naphthylalanine (Nal), at residue 1 (Leu1) were important for both agonistic activity and selectivity toward NMUR1; (4) aliphatic amino acids, e.g., Leu, at residue 2 (Phe2), were important for both agonistic activity and selectivity toward NMUR2; and (5) α,β-diaminopropanoic acid (Dap) and α,γ-diaminobutyric acid (Dab) at residue 3 (Arg3) led to higher agonistic activity and selectivity toward NMUR2.11 Furthermore, the structure of the C-terminal three amino acid residues, e.g., Pro4, Arg5, and Asn6-amide, was critical for the activation of both NMUR1 and NMUR2.11 These results implied that the N-terminal structure could be modified to develop more potent and selective peptidomimetic agonists. Consequently, SAR studies based on the N-terminal structures of 1c and 1d successfully led to the discovery of hexapeptide derivatives 2 and 3 (Figure 1B), which selectively activate NMUR1 and NMUR2, respectively.11 Particularly, the agonistic activity of hexapeptide 3 was amazingly selective to NMUR2, with no NMUR1 activation detected below 10–6 M; however, the agonistic activity of hexapeptide 3 was 3-fold less active than hNMU. However, the NMUR1 selectivity and potency of hexapeptide derivative 2 still had room for improvement, with an NMUR1-agonistic activity of about 10-fold less than that of hNMU. Therefore, in the present study, in order to develop more potent agonists, we performed additional SAR work and found agonist 5d, with potent activity and similar NMUR1-agonistic activity to hNMU. Moreover, we performed stability studies in rat and human serum to assess the biodegradation of the synthesized agonists and found that they were cleaved at two positions: Phe2-Arg3 and Arg5-Asn6. The amide bond of the Arg5-Asn6 site was more preferentially cleaved. In addition, a substitution of Phe2 with the 4-fluorophenylalanine [Phe(4-F)2] in 5d enhanced metabolic stability at the Phe2-Arg3 site. These results will provide important information to guide the development of a more metabolically stable peptidic hNMU agonist.

Figure 1.

(A) Structures of human neuromedin U-derived peptides 1a–d and the SAR results from our previous study.11 Arrows indicate the structural entities required for potent biological activity of the derivatives. (B) Structures of the NMUR1-selective agonist 2 and the NMUR2-selective agonist 3.11

All peptide derivatives were synthesized by 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc)-based solid-phase peptide synthesis as reported previously.11 Constructed protected peptide resins were treated with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)-m-cresol-thioanisole-1,2-ethanedithiol (EDT) (4.0 mL, 40:1:1:1) for 150 min at room temperature, and the resultant crude peptides were purified by preparative reversed-phase (RP)-HPLC. All peptide derivatives were characterized by electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (ESI-TOF MS) and key peptides were analyzed by NMR (see the Supporting Information). Each peptide had a purity of >95% as assessed by RP-HPLC analysis at 220 or 230 nm and was solubilized as a 20 mM stock solution in DMSO for subsequent bioassays. The agonistic activities of peptide derivatives for human NMUR1 and NMUR2 stably expressed in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were evaluated by calcium mobilization assays (see the Supporting Information). The results for each peptide are presented as a relative value (%) compared to the activity of hNMU at a concentration of 1000 nM.

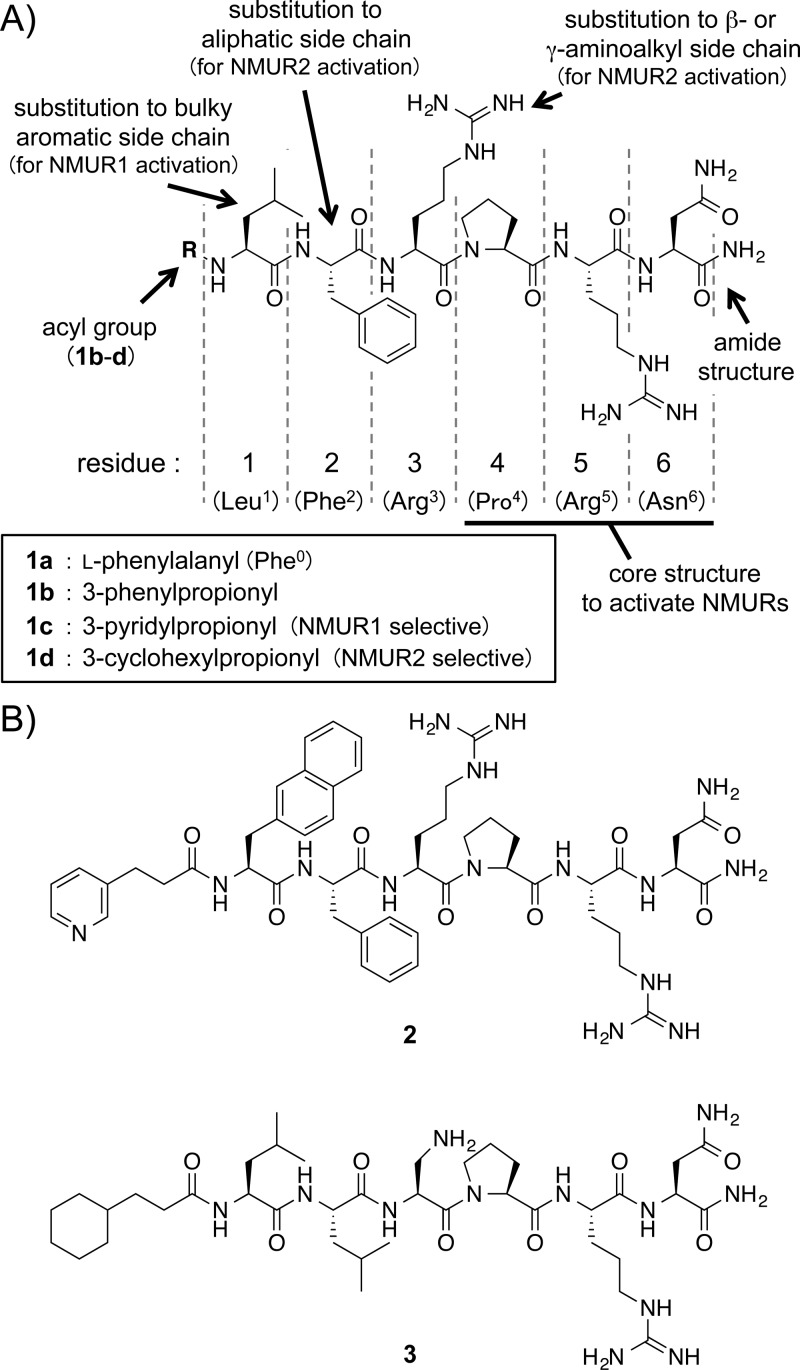

In the present study, to decrease the interexperimental deviation in the screening of potent agonists toward human NMUR1 and NMUR2, we adopted a system in which these receptors were stably expressed in CHO cells. In our previous study employing a transient receptor expression system, one of the potent derivatives, 4a (Figure 2A, derivative 7a in ref (11)), which was derivatized from 1c by substituting the Leu1 residue with a Phe, displayed higher selectivity to NMUR1.11 This result was reproduced in the stable receptor expression system (Figure 2B). Hence, we focused on derivative 4a and began by modifying its N-terminal 3-pyridylpropionyl group. When we introduced 3-(2-thienyl)propionyl and 2-thienylacetyl groups (Figure 2A), the corresponding derivatives, 4b and 4c, respectively, exhibited more potent agonistic activities toward NMUR1 and NMUR2 as compared to 4a (Figure 2B). However, the derivatives with other acyl groups, such as 3-phenylpropionyl (S1a), phenylacetyl (S1b), and acetyl (S1c), showed decreased activities (Figure S1, Supporting Information). These results suggested that the N-terminal thiophene ring played an important role for the activation of human NMU receptors. Therefore, we chose derivative 4c with a lower molecular weight for further modifications.

Figure 2.

(A) Structures of 4a–f. The asterisk indicates that 4a was previously reported.11 (B) Effect of substitutions at the N-terminus (residue 0) and residue 1 on the agonistic activity in CHO cells toward stably expressed human NMUR1 (black bar) and NMUR2 (gray bar) as determined by the calcium mobilization assay. Peptide concentrations, 1 and 10 nM; positive control, hNMU (activity at 1000 nM = 100%).

Next, we focused on residue 1 (Phe) of a 4a-type agonist. In the previous study, introducing the bulky aromatic 2-naphtylalanine (2-Nal) at residue 1 of derivative 2 improved both agonistic activity and selectivity toward NMUR1 as compared to derivative 1c (Figure 1A), which had Leu at that position.11 To further increase the agonistic activity, we synthesized three 4c derivatives, 4d through 4f, bearing Trp (4d), 1-Nal (4e), and 2-Nal (4f) with a side chain similar or identical to residue 1 in derivative 2 (Figure 2A). As shown in Figure 2B, the Trp-bearing derivative, 4d, exhibited the highest agonistic activities to both receptors among this series of derivatives, including the original hexapeptide lead, 1b, and the NMUR1-selective agonist, 2. In particular, the agonistic activity of 4d to NMUR1 was very similar to that of hNMU.

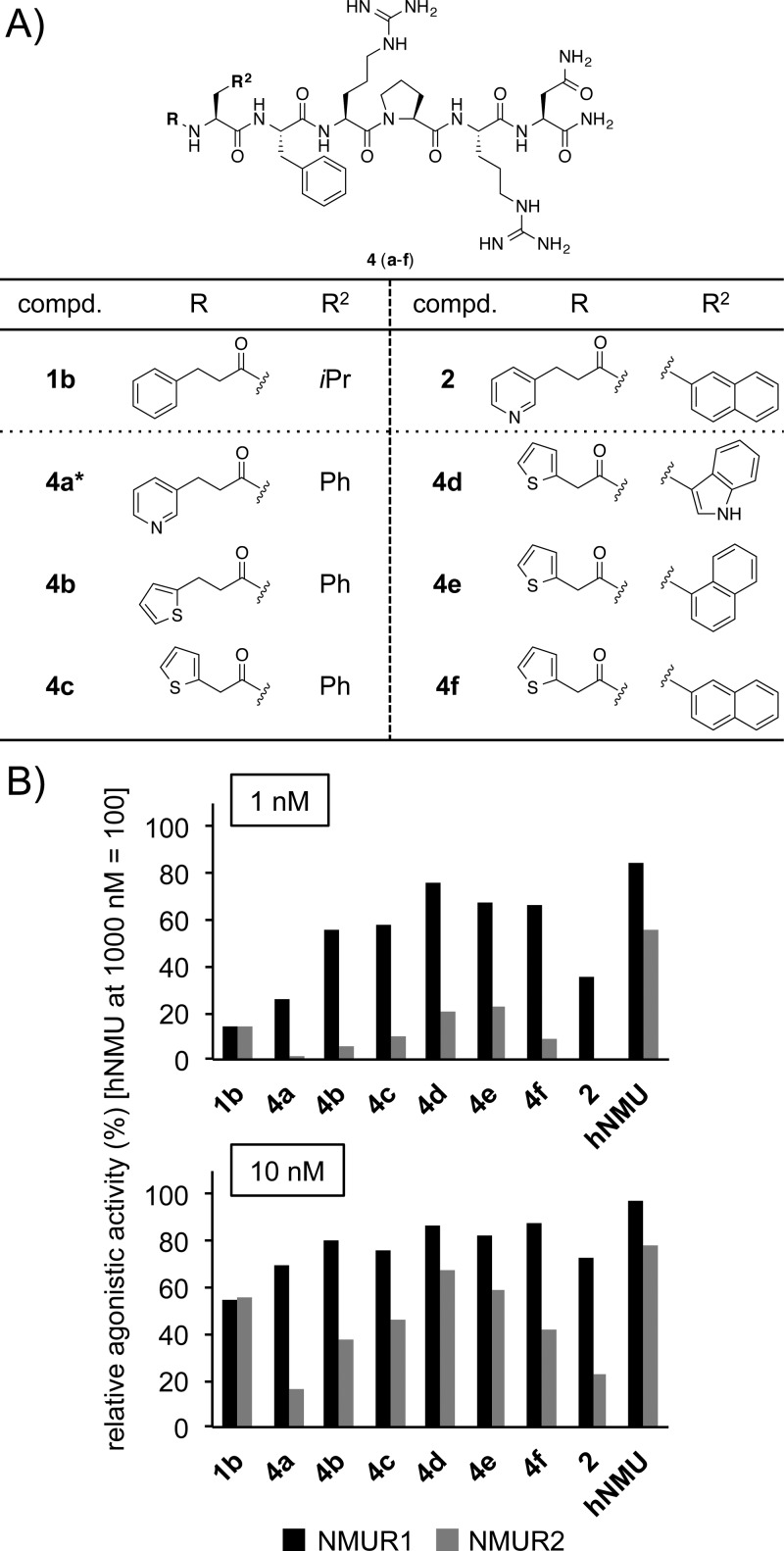

Next, we modified residue 2 (Phe2) based on the structure of derivative 4d. Kurosawa et al. reported that substituting Phe with Tyr typically increased the contractile activity of avian smooth muscle.12 However, in our previous evaluation of human NMU receptors, substitution with three kinds of aromatic amino acids, including Tyr, phenylglycine, and homoPhe, at residue 2 decreased the agonistic activity.11 Moreover, substitution with cyclohexylalanine (an aliphatic amino acid) increased selectivity for NMUR2 rather than NMUR1.11 Therefore, derivatives 5a–d, bearing a series of β-aromatic amino acids at residue 2, i.e., 2-thienylalanine (5a), His (5b), 4-pyridylalanine (5c), and Phe(4-F) (5d), were synthesized (Figure 3A). The agonistic activity of derivative 5a toward NMUR1 slightly decreased by comparison with 4d, whereas its activity toward NMUR2 was nearly maintained (Figure 3B). Derivatives 5b and 5c, bearing nitrogen-heteroaromatic amino acids at residue 2, showed lower agonistic activities toward both receptors as compared to 4d (Figure 3B). Interestingly, introduction of a fluorine atom (5d) to the 4-position of Phe2 in 4d slightly increased the agonistic activities toward NMUR1 and NMUR2. Specifically, the activity toward NMUR1 was slightly higher as compared to hNMU at 0.1 nM (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

(A) Structures of 5a–d. (B) Effect of substitutions at residue 2 on the agonistic activity in CHO cells toward stably expressed human NMUR1 (black bar) and NMUR2 (gray bar) as determined by the calcium mobilization assay. Peptide concentrations, 0.1 and 1 nM; positive control, hNMU (activity at 1000 nM = 100%).

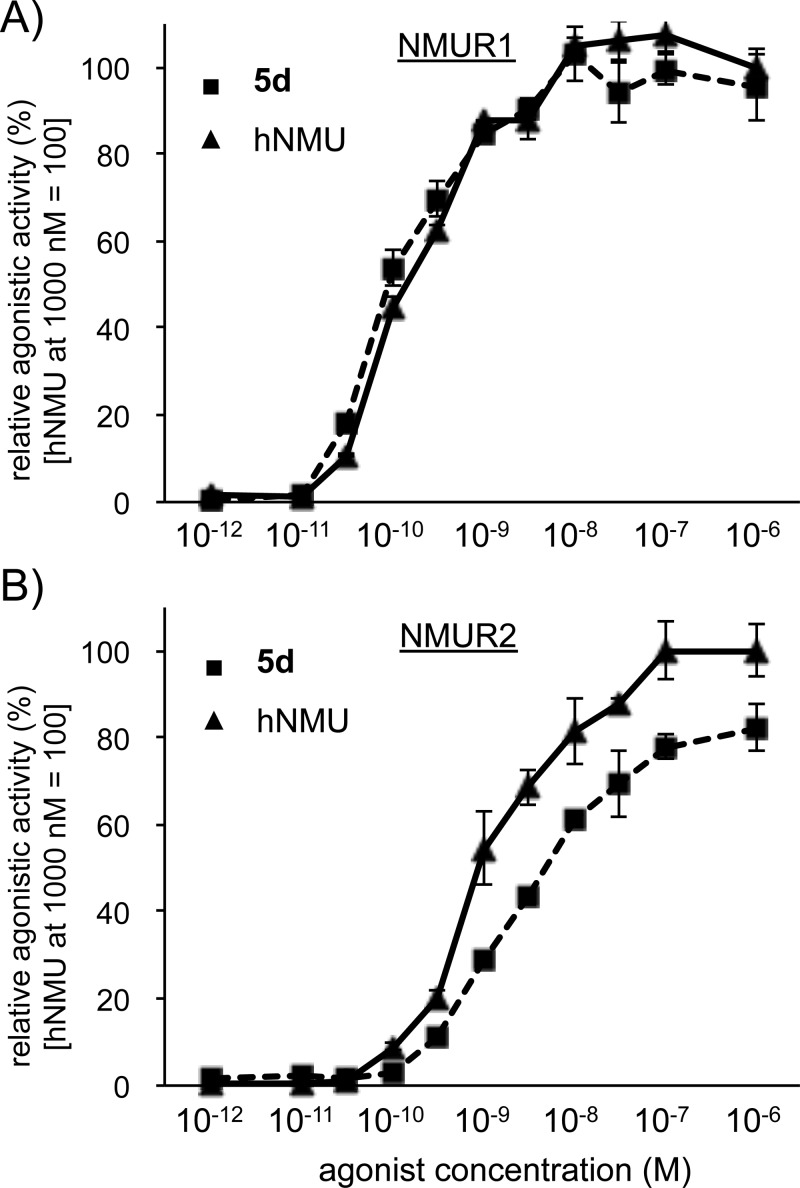

Then, to precisely compare the agonistic activities of derivative 5d and hNMU, we evaluated their dose-dependencies and calculated EC50 values and intrinsic activities (i.a.) toward both human NMU receptors (Figure 4). The EC50 values of derivative 5d toward NMUR1 and NMUR2 were 0.083 ± 0.01 nM (i.a. = 95%) and 2.6 ± 0.3 nM (i.a. = 82%), respectively. This represented a ∼1.7-fold increase and a ∼2.8-fold decrease in potency as compared to hNMU, which gave values of 0.14 ± 0.02 and 0.92 ± 0.2 nM, respectively. These results indicated that derivative 5d was the most potent hexapeptide agonist to activate human NMUR1 to date. In addition, the observed relatively potent agonistic activity of hexapeptide 5d to NMUR2 would also be an important feature for the development of practical antiobesity drugs, which may require the engagement of both human NMU receptors to induce full anorexigenic activity from a peripheral administration of PEG- or HSA-conjugated hNMU.8,9

Figure 4.

In vitro agonistic activity in CHO cells of hexapeptide derivative 5d toward stably expressed human NMUR1 (A) and NMUR2 (B) as determined by the calcium mobilization assay. Peptide concentrations, 10–12–10–6 M; reference compound, hNMU. Data were determined in triplicate.

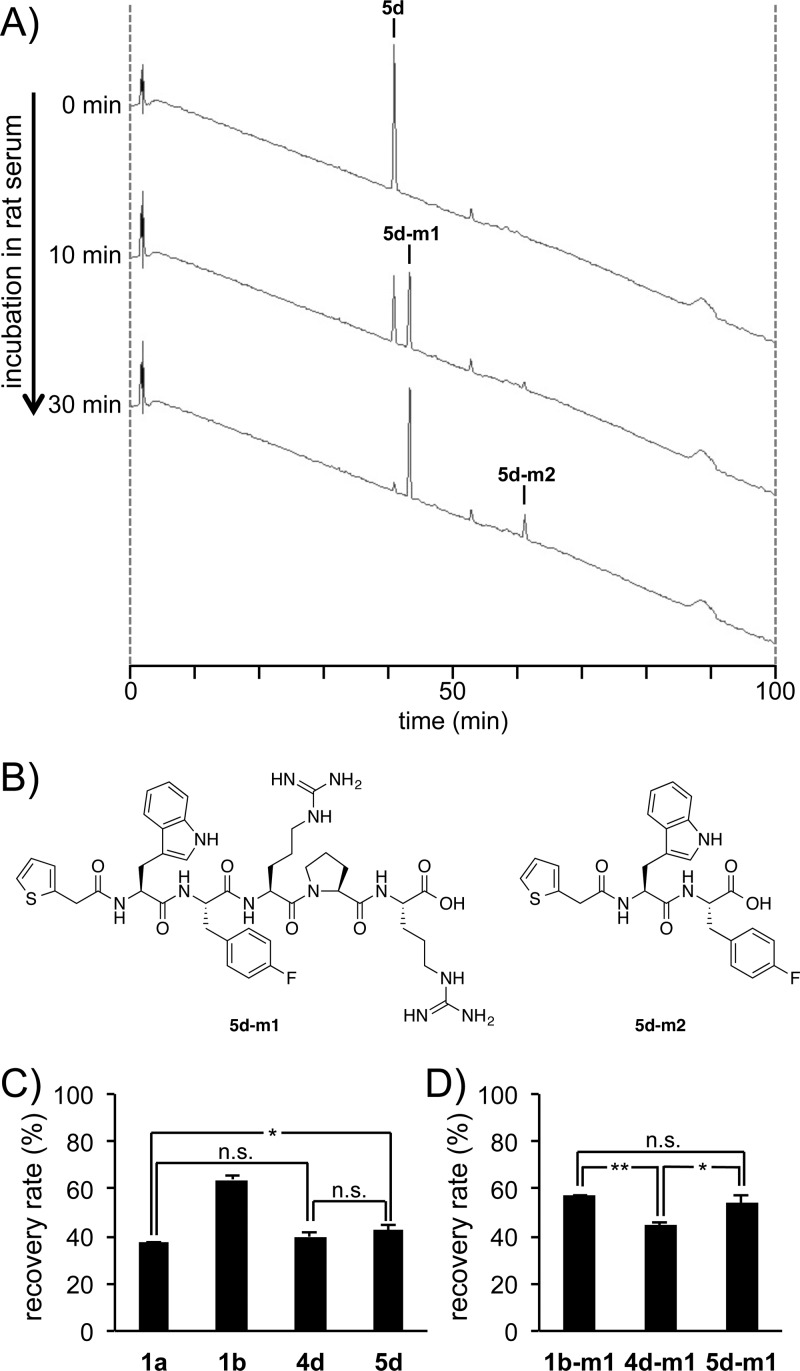

Next, we examined the in vitro stability of derivative 5d in rat serum to understand its metabolic degradation profile. As comparators, we also examined the derivatives 1a, 1b, and 4d. These peptides were incubated in 25% rat serum at 37 °C,13,14 and metabolites at different time points were identified by RP-HPLC after extraction with a Sep-Pak C18 Plus cartridge (see the Supporting Information). RP-HPLC chromatograms showing a representative 5d stability time course are shown in Figure 5A. After 10 min, a new peak appeared at a retention time of 43.7 min (5d-m1); after 30 min, another new peak, with a retention time of 61.2 min, was observed (5d-m2). We successfully determined the structures of these two metabolites by mass spectrometric analysis [5d-m1m/z 903.4091 (M + H)+ (calcd for C43H56FN12O7S 903.4099); and 5d-m2m/z 494.1552 (M + H)+ (calcd for C26H25FN3O4S 494.1550); Figure 5B]. The results suggested that in rat serum the amide bond of derivative 5d seemed to be preferentially cleaved at the C-terminal Arg5-Asn6 site and subsequently at the Phe2-Arg3 site. A similar metabolic profile was observed for derivatives 1b and 4d (Figure S2, Supporting Information). Their respective metabolites were 1b-m1 (3-phenylpropionyl-Leu1-Phe2-Arg3-Pro4-Arg5-OH), 1b-m2 (3-phenylpropionyl-Leu1-Phe2-OH), 4d-m1 (2-thienylacetyl-Trp1-Phe2-Arg3-Pro4-Arg5-OH), and 4d-m2 (2-thienylacetyl-Trp1-Phe2-OH) (Figure S2, Supporting Information). No metabolites of 1a were detected probably due to sequential degradation from the N-terminal-free amino acid residue by aminopeptidase. Additionally, we noted that a cleavage at the C-terminal Arg-Asn site was observed in hNMU under the same conditions (data not shown). Moreover, we examined the stability of derivative 5d in human serum and observed a similar degradation pattern as that shown in rat serum (Figure S3, Supporting Information).

Figure 5.

(A) Analytical RP-HPLC chromatograms showing the time-dependent metabolic degradation of 5d in 25% rat serum. An aliquot of each sample extracted by Sep-Pak C18 Plus cartridges was analyzed using a C18 reverse-phase column detected by UV at 220 nm. (B) The structures of the two major metabolites, 5d-m1 and 5d-m2. (C) Recovery rates of intact peptides 1a, 1b, 4d, and 5d after incubation for 10 min in 25% rat serum. (D) Recovery rates of intact peptides, 1b-m1, 4d-m1, and 5d-m1 after incubation for 60 min in 25% rat serum. Data were determined in triplicate. n.s., not significant; *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.005.

To better understand the metabolism, the recovery rates (%) of intact peptide derivatives 1a, 1b, 4d, and 5d at 10 min were determined (Figure 5C). At first, the N-terminal des-amino hexapeptide derivative, 1b, which was designed to resist aminopeptidase degradation,11 showed improved serum stability (64.0 ± 1.5% recovery) as compared to the free N-terminal heptapeptide derivative, 1a (37.0 ± 0.7% recovery). Contrary to our expectations, however, the recovery rate of the N-terminal acylated derivative, 4d, like 1b, was low (39.8 ± 2.1%) and similar to that of heptapeptide 1a. However, the recovery rate of 5d was slightly better (42.7 ± 1.9%) as compared to 1a. These results suggested that the effect of the fluorine atom toward the metabolic stabilization of 4d was not observed due to probable rapid degradation at the Arg5-Asn6 site.

Thus, to investigate the effect of the Phe(4-F)2-Arg3 bond on metabolic stability, three metabolites, 1b-m1, 4d-m1, and 5d-m1, which did not include the metabolically unstable Arg5-Asn6 bond, were chemically synthesized and evaluated. As shown in Figure 5D, the recovery rate of 5d-m1 at 60 min (54.0 ± 2.9%) was significantly improved as compared to 4d-m1 (44.7 ± 0.6%) and was similar to 1b-m1 (56.9 ± 0.4%). These results suggested that (1) the cleavage rate of the Phe2-Arg3 bond was slower than that of the Arg5-Asn6 bond; (2) substitution with Phe(4-F) at residue 2 in 4d enhanced the stability of the original Phe2-Arg3 bond; and (3) the structural changes in the three N-terminal moieties (acyl group, residues 1 and 2) from 1b to 5d promoted the cleavage rate of the Arg5-Asn6 bond because 5d was more rapidly degraded than 1b in spite of similar recovery rates between 1b-m1 and 5d-m1.

In conclusion, this study clarified that (1) the novel hexapeptide derivative, 5d (designated CPN-170; CPN, C-terminal core peptide derivative of neuromedin U) displayed potent agonistic activity toward human NMU receptors, especially NMUR1; (2) our hexapeptide derivatives were hydrolyzed at two major cleavage sites (the Arg5-Asn6 and Phe2-Arg3 bonds) in rat serum; (3) the Arg5-Asn6 bond was preferentially cleaved as compared to the Phe2-Arg3 bond; (4) introduction of a fluorine atom at the 4-position of Phe in 4d significantly stabilized the Phe2-Arg3 bond; and (5) N-terminal structural modifications at the acyl group, residues 1 and 2 influenced not only the agonistic activity but also the metabolic stability of both cleavage sites. In practical terms, stabilization of the Arg5-Asn6 bond will be necessary to exert a long-lasting anorexigenic effect in vivo. Furthermore, to achieve innovative translational research based on NMUR1, the discovery of more potent and selective agonists beyond derivative 2 will be expected from future SAR studies based on hexapeptide derivative 5d.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- α-MEM

Alfa Modified Eagle Minimum Essential Medium

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- CPN

C-terminal core peptide derivative of neuromedin U

- Dab

α,γ-diaminobutyric acid

- Dap

α,β-diaminopropanoic acid

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DIPCI

diisopropylcarbodiimide

- DMF

dimethylformamide

- EDT

1,2-ethanedithiol

- ESI

electrospray ionization

- FCS

fetal calf serum

- Fmoc

9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl

- HBSS

Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid

- HOBt

1-hydroxybenzotriazole

- HSA

human serum albumin

- i.a.

intrinsic activity

- Nal

naphtylalanine

- NMS

neuromedin S

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- NMU

neuromedin U

- NMUR1

neuromedin U receptor type 1

- NMUR2

neuromedin U receptor type 2

- Phe(4-F)

4-fluorophenylalanine

- RP-HPLC

reversed phase high-performance liquid chromatography

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- TMS

tetramethylsilane

- TOF MS

time-of-flight mass spectrometry

Supporting Information Available

Materials, experimental procedure, analytical data for all peptide derivatives, analytical HPLC chromatograms, NMR spectra, and Figures S1–S3. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

This research was supported in part by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Sciences (JSPS) KAKENHI, including Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) 23390029 (to Y.H.) and 25293188 (to M.M.).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Minamino N.; Kangawa K.; Matsuo H. Neuromedin U-8 and U-25: Novel uterus stimulating and hypertensive peptides identified in porcine spinal cord. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1985, 130, 1078–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori K.; Miyazato M.; Ida T.; Murakami N.; Serino R.; Ueta Y.; Kojima M.; Kangawa K. Identification of neuromedin S and its possible role in the mammalian circadian oscillator system. EMBO J. 2005, 24, 325–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima M.; Haruno R.; Nakazato M.; Date Y.; Murakami N.; Hanada R.; Matsuo H.; Kangawa K. Purification and identification of neuromedin U as an endogenous ligand for an orphan receptor GPR66 (FM3). Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 276, 435–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ida T.; Mori K.; Miyazato M.; Egi Y.; Abe S.; Nakahara K.; Nishihara M.; Kangawa K.; Murakami N. Neuromedin S is a novel anorexigenic hormone. Endocrinology 2005, 146, 4217–4223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazato M.; Hanada R.; Murakami N.; Date Y.; Mondal M. S.; Kojima M.; Yoshimatsu H.; Kangawa K.; Matsukura S. Central effects of neuromedin U in the regulation of energy homeostasis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000, 277, 191–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanada T.; Date Y.; Shimbara T.; Sakihara S.; Murakami N.; Hayashi Y.; Kanai Y.; Suda T.; Kangawa K.; Nakazato M. Central actions of neuromedin U via corticotropin-releasing hormone. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 311, 954–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peier A. M.; Desai K.; Hubert J.; Du X.; Yang L.; Qian Y.; Kosinski J. R.; Metzger J. M.; Pocai A.; Nawrocki A. R.; Langdon R. B.; Marsh D. J. Effect of peripherally administrated neuromedin U on energy and glucose homeostatis. Endocrinology 2011, 152, 2644–2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingallinella P.; Peier A. M.; Pocai A.; Marco A. D.; Desai K.; Zytko K.; Qian Y.; Du X.; Cellucci A.; Monteagudo E.; Laufer R.; Bianchi E.; Marsh D. J.; Pessi A. PEGylation of neuromedin U yields a promising candidate for the treatment of obesity and diabetes. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 4751–4759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuner P.; Peier A. M.; Talamo F.; Ingallinella P.; Lahm A.; Barbato G.; Marco A. D.; Desai K.; Zytko K.; Qian Y.; Du X.; Ricci D.; Monteagudo E.; Laufer R.; Pocai A.; Bianchi E.; Marsh D. J.; Pessi A. Development of a neuromedin U-human serum albumin conjugate as a long-acting candidate for the treatment of obesity and diabetes. Comparison with the PEGylated peptide. J. Pept. Sci. 2013, 20, 7–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto T.; Kurosawa K.; Sakura N. Structure-activity relationships of neuromedin U. II. High potent analogs substituted or modified at the N-terminus of neuromedin U-8. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1995, 43, 1154–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama K.; Mori K.; Taketa K.; Taguchi A.; Yakushiji F.; Minamino N.; Miyazato M.; Kangawa K.; Hayashi Y. Discovery of selective hexapeptide agonists to human neuromedin U receptors types 1 and 2. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 6583–6593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosawa K.; Sakura N.; Hashimoto T. Structure-activity relationships of neuromedin U. III. Contribution of two phenylalanine residues in dog neuromedin U-8 to the contractile activity. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1996, 44, 1880–1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen L. T.; Chau J. K.; Perry N. A.; de Boer L.; Zaat S. A. J.; Vogel H. J. Serum stabilities of short tryptophan- and arginine-rich antimicrobial peptide analogs. PLoS One 2010, 5, e12684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell M. F.; Stewart T.; Otvos L. Jr.; Urge L.; Gaeta F. C. A.; Sette A.; Arrhenius T.; Thomson D.; Soda K.; Colon S. M. Peptide stability in drug development. II. Effect of single amino acid substitution and glycosylation on peptide reactivity in human serum. Pharm. Res. 1993, 10, 1268–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.