Abstract

Collagenous gastritis is a rare disease characterized by the subepithelial deposition of collagen bands thicker than 10 μm and the infiltration of inflammatory mononuclear cells in the lamina propria. Collagenous colitis and collagenous sprue have similar histological characteristics to collagenous gastritis and are thought to be part of the same disease entity. However, while collagenous colitis has become more common in the field of gastroenterology, presenting with clinical symptoms of chronic diarrhea in older patients, collagenous gastritis is rare. Since the disease was first reported in 1989, only 60 cases have been documented in the English literature. No safe and effective treatments have been identified from randomized, controlled trials. Therefore, better understanding of the disease and the reporting of more cases will help to establish diagnostic criteria and to develop therapeutic strategies. Therefore, here we review the clinical characteristics, endoscopic and histological findings, treatment, and clinical outcomes from case reports and case series published to date, and provide a summary of the latest information on the disease. This information will contribute to improved knowledge of collagenous gastritis so physicians can recognize and correctly diagnose the disease, and will help to develop a standard therapeutic strategy for future clinical trials.

Keywords: Collagenous gastritis, Collagen deposition, Collagenous colitis, Nodularity

Core tip: The diagnosis of collagenous gastritis is based on the histological findings of collagen bands thicker than 10 μm in the subepithelial layer and infiltration of inflammatory mononuclear cells in the lamina propria. Similar histological changes are seen in the colon in collagenous colitis. While there are many cases of collagenous colitis published in the literature, there are only 60 reported cases of collagenous gastritis since the disease was first identified in 1989. The present review discusses the characteristics of this disease entity and summarizes the cases reported to date. Better knowledge and understanding of collagenous gastritis will help physicians to diagnose the disease, and the accumulation of future cases will help to develop a standard therapeutic strategy.

INTRODUCTION

Collagenous gastroenteritides include collagenous gastritis, collagenous sprue, and collagenous colitis. This disease entity is relatively uncommon and believed to be rare. The diseases are characterized by marked subepithelial collagen deposition accompanying with mucosal inflammatory infiltrate[1-5]. The exact etiology and pathogenesis of this inflammatory disorder remains unclear and clinical presentations are related to the region of the gastrointestinal tract involved. While collagenous colitis is the most frequently found in this disease category[5,6], collagenous gastritis and collagenous sprue involving the proximal side of the gastrointestinal tract is rarer. Recently, it is reported that the overall annual incidence of collagenous colitis ranges from 1.1 to 5.2 cases per 100000 population and it is a relatively frequent cause of chronic diarrhea in elderly patients[7]. For collagenous gastritis, Colleti reported first case of 15-year-old girl who presented with recurrent abdominal pain and gastrointestinal bleeding in 1989[8]. On endoscopy, nodular changes were seen in the stomach. Subepithelial collagen deposits and inflammatory infiltration of the lamina propria were observed on histological examination. Despite treatment with histamine H2-receptor antagonists, sucralfate, and furazolidone, no clinical or pathological improvement was achieved[8]. Since 1989, only 60 cases of collagenous gastritis have been reported in the English literature[2-4,8-40]. Because of the small number of cases, no standard therapy has been established based on randomized, controlled clinical trials. However, based on case reports, two phenotypes of the disease (pediatric and adult) have been defined[21]. The presenting symptoms of the pediatric type are mainly upper gastrointestinal, including abdominal pain and anemia secondary to the stomach-specific inflammation and collagen deposition[10,21]. In contrast, the adult type is characterized by the simultaneous occurrence of collagenous colitis, which may be related to autoimmune processes and celiac disease[21]. The endoscopic findings of mucosal nodularity and the histological findings of inflammatory infiltration with thick collagen deposits are common in both adult and pediatric disease. However, the areas of the gastrointestinal tract involved are different, raising the possibility of a different etiology[1,3]. Because the pathophysiology of collagenous gastritis remains uncertain, no effective therapeutic strategies have been developed. Better knowledge and understanding of the disease will help physicians make a correct diagnosis at an early stage, and may help to establish rational treatment options. In this paper, we review the clinical and pathological characteristics of the 60 cases[2-4,8-40] reported to date.

LITERATURE ANALYSIS

A literature search was conducted using PubMed and Ovid, with the term “collagenous gastritis.” The literatures written in English from relevant publications were selected. We summarized the available information on demographics, clinical symptoms, endoscopic and histological findings, treatment, and the clinical course.

CLINICAL CHARACTERS

Among the 60 reported cases of collagenous gastritis, there was a slight female predominance (35 females, 25 males). The ages ranged from 9 mo to 80 years[2-4,8-40].

Clinical symptoms included abdominal pain in 26 cases[3,4,8-10,12-15,17,18,20,26,30-33,38-40], anemia in 24[2,4,8,10,11,14,16,17,19,21,22,30,36,37,39,40], diarrhea in 18[13,17,21-29,35-37], nausea and vomiting in 7[3,15,17,31,32], body weight loss in 4[3,23,35], abdominal distention in 3[24,32,36], gastrointestinal bleeding in 3[8,17,36], and fatigue[4], retrosternal pain[11], dyspepsia[2], perforated ulcer[17], dysphagia[17], and constipation[38] in 1 case each. Lagorce-Pages et al[21] reported that clinical symptoms differ between pediatric and adult patients based on the severity of the disease and part of the gastrointestinal tract involved. Pediatric patients typically present in their early teens with anemia and abdominal pain related to involvement of the stomach[3,21,33,38]. The adult type is characterized by more diffuse involvement of the gastrointestinal tract and typically presents with a chronic watery diarrhea associated with collagenous colitis and collagenous sprue[36,37]. Adult collagenous gastritis is also associated with autoimmune diseases, such as Sjögren syndrome[36], lymphocytic gastritis, lymphocytic colitis, and ulcerative colitis[37]. Of the 11 patients who presented with abdominal pain and anemia, 8 were teenagers (72%)[4,8,10,14,17,30]. Of the 18 patients who presented with diarrhea, 15 were older than 20 years (83%)[17,21-27,35-37] (Table 1). Ten of the adult patients had collagenous duodenitis, which is extremely rare, and of these, 9 also had collagenous colitis[2,40]. Our literature search revealed no difference in the presence of Helicobacter pylori infection between pediatric (n = 6)[15,19,28,29] and adult patients (n = 4)[9,21,33]. The eradication of H. pylori did not produce any therapeutic benefit. The clinical characteristics of the 60 published cases supported the differences between pediatric-type and adult-type collagenous gastritis reported to date. In the pediatric form of the disease, inflammation is limited to the stomach and patients present with relatively severe upper gastrointestinal symptoms. The adult form of collagenous gastritis often involves other parts of the gastrointestinal tract, and might be the part the collagenous gastroenteritides disease entity. In adults, the presenting symptoms vary depending on the severity of the inflammation and the areas of the gastrointestinal tract involved.

Table 1.

Summary of 60 collagenous gastritis patients

| Ref. | Age (yr) | Gender |

Symptoms |

Endoscopic Findings |

H. pylori |

Collagen band (μm) |

Treatment | Follow-up biopsy duration (yr) | Histological changes | Clinical course | ||||||||

| Abdominal pain | Anemia | Diarrhea | Nausea, vomiting | Others | Nodularity | Erythema | Erosion, gastritis | Others | Stomach | Colon | ||||||||

| [10] | 7 | F | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | NA | Yes | None | Oral iron supplementation, Proton-pump inhibitor | 0.5 | Improvement of inflammation remaining of collagen band | Improve |

| [11] | 9 | F | - | + | - | - | Retrosternal pain | - | + | - | - | - | 13-96 | < 5 | Proton-pump inhibitor, Sucralfate, Steroid | 1.1 | No reduction | No change |

| [12] | 9 | F | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | 35 | None | Oral iron supplementation | 4 | Decrease of chronic gastritis, Unchanged collagen bands | Clinical remission |

| [13] | 9 | F | + | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | Yes | Yes | Oral iron supplementation | NA | NA | Improve |

| [14] | 9 | F | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | NA | NA | Yes | NA | Mesalazine | NA | Remain | |

| [15] | 12 | F | - | - | - | + | - | + | - | - | - | + | NA | None | Proton-pump inhibitor | 1 | Severe erosive gastritis | Remain |

| [15] | 12 | F | + | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | + | NA | None | Proton-pump inhibitor | 6 | Decrease of nodules | Improve |

| [15] | 12 | F | + | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | + | NA | NA | Proton-pump inhibitor | 0.17 | NA | Improve |

| [16] | 12 | F | - | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | Yes | None | Oral iron supplementation | NA | ||

| [17] | 13 | F | - | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | 76 | NA | None | NA | NA | NA |

| [18] | 14 | F | + | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | 75 | None | Proton-pump inhibitor, Sucralfate, H2-receptor antagonist | 12 | Gradual progression | Remain |

| [17] | 14 | F | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | 23 | NA | Proton-pump inhibitor | NA | NA | Remain |

| [8] | 15 | F | + | + | - | - | Gastrointestinal bleeding | + | - | - | - | - | 75 | None | H2-receptor antagonist, sucralfate, furazolidone | 2 | No reduction | NA |

| [19] | 15 | F | - | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | + | NA | NA | Proton-pump inhibitors, Oral iron supplementation, Steroid | 0.83 | NA | Clinical remission |

| [17] | 15 | F | + | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | 69 | None | Steroid | 3.4 | Decrease of inflammation | Improve |

| [4] | 16 | F | + | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | NA | None | H2-receptor antagonist, Proton-pump inhibitor, Oral iron supplementation, | 6 | No reduction | Improvement of anemia |

| [20] | 20 | F | + | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | 30-70 | None | Proton-pump inhibitor | 2 | No change | NA |

| [21] | 22 | F | - | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | 40-45 | NA | None | NA | NA | NA |

| [40] | 22 | F | + | + | - | - | Gastrointestinal bleeding | + | - | + | Duodenitis | - | 60-100 | None | H2-receptor antagonist,Proton-pump inhibitor | 1 | No change | Improve |

| [22] | 25 | F | - | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | 24 | Yes | None | 0.25 | No change | NA |

| [23] | 25 | F | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | - | NA | NA | Yes | NA | None | NA | NA | NA |

| [23] | 25 | F | - | - | + | - | Body weight loss | - | - | - | NA | NA | Yes | Yes | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| [39] | 25 | F | + | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | NA | - | 17 | None | H2-receptor antagonist,Proton-pump inhibitor | 4 | No change | No change |

| [24] | 35 | F | - | - | + | - | Abdominal distention | + | - | - | - | - | 20-30 | None | Sulfasalazine | NA | NA | Remission of diarrhea |

| [4] | 39 | F | - | + | - | - | Fatigue | - | - | - | Normal | - | NA | Yes | Gluten-free diet | 4 | No reduction | Improve |

| [21] | 40 | F | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | - | Normal | - | 40-41 | None | Steroid, Sulfasalazine, Parenteral nutrition | 2 | Resolve of collagen band | NA |

| [21] | 52 | F | - | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | Normal | + | 15-20 | None | None | NA | NA | NA |

| [17] | 52 | F | + | - | + | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | 78 | None | Gluten-free diet | NA | NA | Improve |

| [25] | 57 | F | - | - | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | 20-40 | > 30 | Steroid | 1.5 | No change | Responded to steroid |

| [17] | 57 | F | + | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | 40 | NA | Gluten-free diet | NA | NA | Improve |

| [22] | 58 | F | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | 15.8 | None | Steroid | 1.5 | Improvement of inflammation remaining of collagen band | NA |

| [17] | 62 | F | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | 94 | NA | None | NA | NA | NA |

| [2] | 68 | F | - | + | - | - | Dyspepsia | + | - | - | - | - | None | None | Oral iron supplementation, Proton-pump inhibitor | 0.83 | Improvement of inflammation increase of collagen band | Partial relief |

| [26] | 74 | F | + | - | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | Yes | Yes | Proton-pump inhibitor | 0.08 | No change | Improve |

| [27] | 75 | F | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | - | Normal | NA | 30-60 | 10-30 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| [28] | 0.75 | M | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | + | - | + | 50 | 17 | Steroid, Total parenteral nutrition | 14 | Gradual progression | Improve with total parenteral nutrition |

| [29] | 2 | M | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | + | - | + | > 5 | NA | Proton-pump inhibitors, Mesalazine, Steroid, Bismuth subsalicylate | NA | NA | Improve |

| [30] | 9 | M | + | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | 30-150 | None | Oral iron supplementation | 2 | NA | NA |

| [21] | 11 | M | - | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | 50-69 | None | None | 8 | Moderate decrease | NA |

| [10] | 11 | M | + | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | NA | > 10 | NA | Proton-pump inhibitor, Oral iron supplementation | 5 | Improvement of inflammationresolve of collagen band | Improve |

| [13] | 15 | M | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | 30 | 30 | Proton-pump inhibitor, Steroid, Mesalazine | NA | NA | Clinical remission |

| [17] | 19 | M | + | + | - | - | Perforation of ulcer | + | - | - | - | - | 40 | NA | Sucralfate | 0.25 | Improvement of inflammationdecrease of collagen band | Improve |

| [38] | 19 | M | + | - | - | - | Constipation | + | - | - | - | NA | 15 | None | None | 0.5 | Progression | Improve |

| [31] | 20 | M | + | - | - | + | - | + | - | - | - | - | 15-43 | 20-30 | H2-receptor antagonist, Oral iron supplementation | 4 | Progression | No change |

| [32] | 25 | M | + | - | - | + | Abdominal distention | + | - | - | - | - | > 10 | None | Proton-pump inhibitor | NA | NA | Improve |

| [33] | 25 | M | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Normal | + | Yes | NA | None | NA | NA | NA |

| [17] | 34 | M | + | + | - | - | Gastrointestinal bleeding | + | - | - | - | - | 78 | NA | None | 9.9 | Gradual progression | NA |

| [33] | 35 | M | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | 50 | None | None | 14 | Increase | Increase |

| [21] | 36 | M | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | - | - | - | NA | - | 15-20 | NA | None | NA | NA | NA |

| [35] | 37 | M | - | - | + | - | Body weight loss | + | - | - | - | - | 120 | None | Steroid, Azathioprine, Parenteral nutrition | 1.67 | No change | Improve |

| [36] | 42 | M | - | + | + | - | Abdominal distention, Rectal bleeding | - | + | - | - | NA | 26-10 | None | Gluten-free diet | 0.25 | No change | Improve |

| [9] | 47 | M | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Normal | + | 70 | None | Proton-pump inhibitor | NA | NA | Improve |

| [17] | 56 | M | - | - | - | + | - | + | - | - | - | - | 87 | None | Steroid, Gluten-free diet | NA | NA | Improve |

| [3] | 56 | M | + | - | - | + | Body weight loss | - | - | + | - | NA | Yes | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| [37] | 57 | M | - | + | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | NA | 13-45 | None | Steroid, Mesalazine | NA | NA | Improve |

| [17] | 59 | M | - | - | - | - | Dysphagia | - | - | - | Normal | - | 54 | NA | None | NA | NA | NA |

| [17] | 68 | M | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | 20 | NA | Steroid, Gluten-free diet | 0.75 | Gradual progression | Remain |

| [23] | 72 | M | - | - | + | - | Body weight loss | - | - | - | NA | NA | Yes | Yes | Steroid | NA | NA | Improve |

| [21] | 77 | M | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | - | + | 20-28 | NA | None | NA | NA | NA |

| [17] | 80 | M | - | + | + | - | - | + | - | - | - | - | 47 | None | Steroid | NA | NA | NA |

NA: Not available.

ENDOSCOPIC FINDINGS

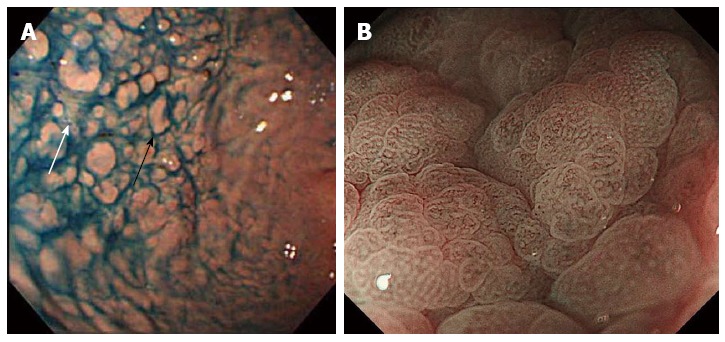

Nodularity of the gastric corpus is the characteristic endoscopic finding in collagenous gastritis. However, it is not seen in all cases. Our literature review found that 32 of the 60 patients showed endoscopic nodularity, with no difference in frequency between pediatric (n = 17)[4,8,10,13,15-19,21,29,30,38] and adult (n = 16)[2,17,20-22,24,31,32,34,35,39,40] cases (Table 1). The other endoscopic findings included mucosal erythema, erosions, and exudates. Normal gastric mucosa was found in 7 patients. The mucosal nodules were irregular in size and were located diffusely throughout the gastric body and antrum. The size and number depended on the severity of the inflammation (Figure 1A)[34]. Interestingly, in collagenous gastritis, it is not the mucosal thickening that causes the typical nodular appearance, but the depressed mucosa surrounding the nodules. This suggests that uneven inflammation causes glandular atrophy and collagen deposition in the depressed mucosa. Therefore, the nodular lesions show fewer inflammatory infiltrates and atrophic changes. In contrast, collagenous colitis shows a relatively even distribution of inflammation and atrophic changes, resulting in the homogeneous mucosal changes seen on the endoscopy of the colon. These findings have been supported by the recent results of narrow band imaging (NBI) studies and histological analysis. Kobayashi et al[41] used NBI with magnifying colonoscopy to examine the gastric mucosa in collagenous gastritis patients. The mucosal surface of the nodular lesions showed no marked changes and no abnormal capillary vessels were observed. However, as expected, the depressed mucosa surrounding these nodules showed an amorphous or absent surface structure and abnormal capillary vessels, including blind endings and irregular caliber changes (Figure 1B). This indicates that the depressed mucosal pattern is the result of inflammation with atrophic changes and collagen deposition, whereas the nodular lesions are the remaining undamaged mucosa[34].

Figure 1.

Endoscopic findings of collagenous gastritis. A: Nodular lesions (black arrow) in the greater curvature of the gastric body. Depressive mucosal lesions are seen in between nodular lesions (white arrow)[34]; B: Magnifying endoscopic image with narrow band imaging. Amorphous or absent surface pit pattern and abnormal capillary vessel patterns are seen in the depressed mucosal area[41].

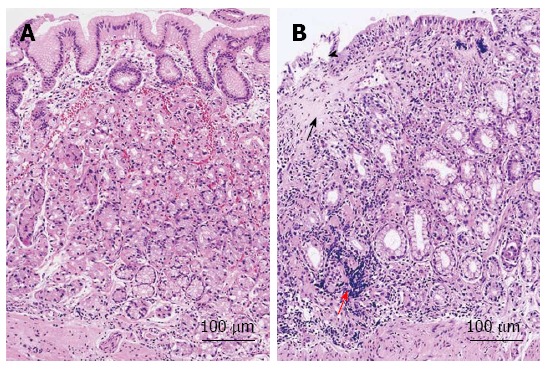

PATHOLOGICAL FINDINGS

The pathological findings of collagenous gastritis are characterized by the infiltration of chronic inflammatory cells in the subepithelial layer, especially in the lamina propria, and the deposition of collagen bands thicker than 10 μm[13,37]. The inflammatory cells include lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils. Inflammation causes atrophic changes in the mucosal glands and leads to the depressed mucosal pattern found on endoscopy (Figure 2A)[34]. The pathological changes are less marked in the nodular mucosal lesions (Figure 2B)[34]. Therefore, a heterogeneous inflammatory pattern causes the nodular lesions in the stomach. These pathological findings suggest that several mucosal biopsies are needed for correct diagnosis, and careful mapping is required for the follow-up of mucosal inflammation and the thickness of collagen deposits. Our review found that most of the cases with information on the thickness of collagen deposits had bands thicker than 10 μm, with a range between 10 and 100 μm[11,20,30,40]. This supports the evidence for the heterogeneity of collagen deposition. The thickness of the collagen deposits may increase with disease duration; however, it may also be influenced by the location of the biopsy rather than the severity of the disease[16,17,19,21,37]. Total of 11[4,11,13,22,23,25-28] patients showed collagen deposition in colon and 7 (63%)[4,22,23,25-27] were older than 20 years old. These adult patients with coexisting collagenous colitis, showed diffuse and continuous collagen deposits in the colon but heterogeneous changes in the stomach[4]. This finding supports the hypothesis that the adult type of collagenous gastritis is part of the collagenous gastroenteritides, which tend to present with more severe symptoms related to involvement of the colon[4]. In addition, as 4 patients among 11 who showed collagenous colitis were young patients (36%)[11,13,28], it is suggested that the disease type might not only be related to the age, but the etiology reflecting the tract involved.

Figure 2.

Histological findings of collagenous gastritis. A: Nodular mucosal lesion did not show marked inflammatory infiltration and collagen deposition; B: Depressive mucosal lesion showed a thick collagen deposition (black arrow) and inflammatory infiltrates (red arrow). The glandular atrophy and epithelial damage is marked (black arrowhead)[34].

Collagen deposition can be clearly visualized with Masson Trichrome staining. Collagen samples have been typed in a few patients[4,18,20,21,25], with types III and VI identified. Some samples were positive for tenascin, a marker of cell proliferation and migration[4,42]. Type III collagen is released from subepithelial fibroblasts to repair damage caused by inflammation. Therefore, the collagen synthesis in collagenous gastritis is not a primary pathology but a reparative response[4]. The study focusing on the collagen tissue type may contribute to clarify the etiology and help to differentially diagnose adult and pediatric types. The pathological findings reported in the published cases support the evidence that the endoscopic finding of nodularity is the result of heterogeneous inflammation and the destruction of mucosal glands and the surrounding mucosa (Table 2). However, the reason for the uneven inflammation in the stomach, in contrast to the relatively homogeneous inflammation in the colon, remains unclear.

Table 2.

Difference of mucosal pattern

| Nodular mucosa | Depressive mucosa |

| No significant inflammation | Infiltration of inflammatory cells |

| Irregular distribution | Atrophic glands |

| Irregular size | Collagen band |

| Normal mucosal surface pattern | Amorphous or absent surface structure Abnormal capillary vessels |

THERAPY

Because of the small number of patients and the unknown etiology, there is no established standard therapy for collagenous gastritis. Anti-secretary agents including proton-pump inhibitors[2,4,9-11,13,15,17-20,26,29,32,39,40], and H2-receptor antagonists[4,8,18,39,40], steroids[11,13,17,19,21-23,25,28,29,35,37], iron supplementation[2,4,10,12,13,16,19,30], and hypoallergenic diets[4,17,36] have been tried with limited success (Table 1). Other treatment modalities, such as sucralfate[8,11,17,18], mesalazine[13,14,29,37], bismuth subsalicylate[29], furazolidone[8], sulfasalazine[21,24], azathioprine[35], and parenteral nutrition[21,28,35] have also been tested. A few patients have shown improvement of the clinical symptoms but no randomized, controlled trials have been performed. Further cases are needed to establish a standard therapeutic strategy. However, potential therapeutic approaches are complicated by the possibility that the pediatric and adult forms of the disease may have different etiologies. Furthermore, it remains unclear whether the pediatric type transforms to the adult type over time.

FOLLOW UP

The course and prognosis of collagenous gastritis remain unclear. The case reports include 30 patients who had undergone follow-up (Table 1). The median follow-up period was 2 years (0.08-14) and the clinical course and the response to therapy was evaluated. Kamimura et al[34] reported that in a patient followed for 14 years, the nodular appearance on endoscopy became more conspicuous and extended throughout the stomach. Histology showed that the thickness of collagen deposits increased over the 14 years. As discussed above, the heterogeneity of inflammation affects the thickness of the collagen deposits. Therefore, it is difficult to conclude that the collagen bands did become thicker. However, Billiemaz et al[28] reported similar endoscopic and histological findings of gradual disease progression during long-term follow-up. Conversely, Winslow et al[18] found no changes in the nodular appearance on endoscopy during the 12 year follow-up of one patient. Over the same 12 year period, biopsies showed patchy, chronic active gastritis with gradual progression in disease severity, although the collagen deposits did not appear to become more diffusely distributed or thicker over time. Lagorce-Pages et al[21] reported on 2 patients who showed complete absence of collagen deposits (40-year-old female) or a moderate decrease (11-year-old male) in the thickness of subepithelial collagen deposits on biopsy obtained 2 and 8 years after the initial diagnosis, respectively. The patient who recovered had been treated with steroid, salazopyrin, and parenteral alimentation. Hijaz et al[10] also reported on a patient who showed improvement of inflammation and an absence of collagen deposits 5 years after the initial diagnosis. This patient was treated with oral iron supplementation and proton-pump inhibitors[10]. Leung et al[17] reported a case of a 19-year-old male who showed improvement of inflammation and a decrease in the thickness of collagen deposits 3 mo after treatment with sucralfate[17]. On the other hand, Vakiani et al[22] and Rustagi et al[2] reported on patients who showed improvement of inflammation but unchanged or thicker collagen deposits after treatment with steroids and budesonide for 1.5 years, and oral iron supplementation and a proton-pump inhibitor for 0.83 years. These reports suggest that the inflammation can be managed by treatment. However, in most cases, the collagen deposits remain unchanged or become thicker as a result of continued inflammation. There was no evidence of the transformation of the pediatric-type disease to adult-type among the case reports.

DISCUSSION

Collagenous gastritis is a rare clinicopathological entity with only 60 cases reported to date[2-4,8-40] (Table 1). Although a primary vascular abnormality causing increased vascular permeability and collagen deposition has been proposed, the etiology of the disease is poorly understood[10]. The symptoms vary depending on the area of gastrointestinal tract involved, and in young patients, abdominal pain and anemia occur secondary to stomach-specific infiltration. Multiple areas are involved in adult patients, who often show chronic diarrhea because of coexisting collagenous colitis[3,5,6,21]. Characteristic differences are summarized in Table 3 and our review supports this hypothesis. Of the 11 patients who presented with abdominal pain and anemia, 8 were teenagers (72%)[4,8,10,14,17,30]. Conversely, of the 18 patients who presented with diarrhea, 83% (15 patients) were adults[17,21-27,35-37]. This suggests that adult-type collagenous gastritis is part of the collagenous gastroenteritides disease entity. The endoscopic findings include relative nodular changes in the mucosa, due to the chronic inflammatory infiltration, mucosal atrophy, and the deposition of bands of collagen. Compared with the diffuse and continuous deposition seen in collagenous colitis, the changes in collagenous gastritis are heterogeneous. The reason for this heterogeneity remains unclear, but it might be related to the etiology of gastritis. In addition, as 4 among 11 patients who had collagenous colitis were young patients[11,13,28], it is suggested that the disease type might not only be related to the age, but the etiology reflecting the tract involved.

Table 3.

Differences of adult and pediatric type of collagenous gastritis

| Pediatric type | Adult type | |

| Etiology | Unknown | Systematic disease, Autoimmune disease, drug induced |

| Gastrointestinal tract involved | Stomach | Stomach, colon, duodenum |

| Symptoms | Abdominal pain, anemia | Diarrhea |

| Endoscopy | Heterogeneous, Nodular pattern, | Homogeneous |

| Histology | Heterogeneous inflammatory infiltration, collagen band | Homogeneous inflammation |

Compared with collagenous gastritis, more patients are diagnosed with collagenous colitis. In these patients, adult-type collagenous gastritis may coexist. Therefore, upper endoscopy is recommended. In addition, multiple mucosal biopsies are needed because of the heterogeneous inflammatory pattern. Some areas of the stomach may show normal mucosa and our review identified 7 patients with endoscopically normal mucosa. Currently, transition from pediatric-type to adult-type disease is thought to be rare. However, more cases are needed to better understand this disease entity and to establish a standard therapeutic strategy.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest: The authors declare that they do not have a current financial arrangement or affiliation with any organisation that may have a direct interest in their work.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: October 11, 2014

First decision: October 28, 2014

Article in press: December 17, 2014

P- Reviewer: Kato J, Souza JLS S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

References

- 1.Nielsen OH, Riis LB, Danese S, Bojesen RD, Soendergaard C. Proximal collagenous gastroenteritides: clinical management. A systematic review. Ann Med. 2014;46:311–317. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2014.899102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rustagi T, Rai M, Scholes JV. Collagenous gastroduodenitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:794–799. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31820c6018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gopal P, McKenna BJ. The collagenous gastroenteritides: similarities and differences. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:1485–1489. doi: 10.5858/2010-0295-CR.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brain O, Rajaguru C, Warren B, Booth J, Travis S. Collagenous gastritis: reports and systematic review. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:1419–1424. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32832770fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freeman HJ. Complications of collagenous colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1643–1645. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Camarero C, Leon F, Colino E, Redondo C, Alonso M, Gonzalez C, Roy G. Collagenous colitis in children: clinicopathologic, microbiologic, and immunologic features. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37:508–513. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200310000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams JJ, Beck PL, Andrews CN, Hogan DB, Storr MA. Microscopic colitis -- a common cause of diarrhoea in older adults. Age Ageing. 2010;39:162–168. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afp243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colletti RB, Trainer TD. Collagenous gastritis. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:1552–1555. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)90403-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Kandari A, Al-Alardati H, Sayadi H, Al-Judaibi B, Mawardi M. An unusual case of collagenous gastritis in a middle- aged woman with systemic lupus erythromatosis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:278. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-8-278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hijaz NM, Septer SS, Degaetano J, Attard TM. Clinical outcome of pediatric collagenous gastritis: case series and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1478–1484. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i9.1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Côté JF, Hankard GF, Faure C, Mougenot JF, Holvoet L, Cézard JP, Navarro J, Peuchmaur M. Collagenous gastritis revealed by severe anemia in a child. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:883–886. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90461-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ravikumara M, Ramani P, Spray CH. Collagenous gastritis: a case report and review. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:769–773. doi: 10.1007/s00431-007-0450-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suskind D, Wahbeh G, Murray K, Christie D, Kapur RP. Collagenous gastritis, a new spectrum of disease in pediatric patients: two case reports. Cases J. 2009;2:7511. doi: 10.4076/1757-1626-2-7511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Camarero Salces C, Enes Romero P, Redondo C, Rizo Pascual JM, Roy Ariño G. Collagenous colitis and collagenous gastritis in a 9 year old girl: a case report and review of the literature. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2011;74:468–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kori M, Cohen S, Levine A, Givony S, Sokolovskaia-Ziv N, Melzer E, Granot E. Collagenous gastritis: a rare cause of abdominal pain and iron-deficiency anemia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:603–606. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31803cd545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson C, Thompson K, Hunter C. Nodular collagenous gastritis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49:157. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181ab6a43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leung ST, Chandan VS, Murray JA, Wu TT. Collagenous gastritis: histopathologic features and association with other gastrointestinal diseases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:788–798. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318196a67f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winslow JL, Trainer TD, Colletti RB. Collagenous gastritis: a long-term follow-up with the development of endocrine cell hyperplasia, intestinal metaplasia, and epithelial changes indeterminate for dysplasia. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001;116:753–758. doi: 10.1309/3WM2-THU3-3Q2A-DP47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dray X, Reignier S, Vahedi K, Lavergne-Slove A, Marteau P. Collagenous gastritis. Endoscopy. 2007;39 Suppl 1:E292–E293. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kajino Y, Kushima R, Koyama S, Fujiyama Y, Okabe H. Collagenous gastritis in a young Japanese woman. Pathol Int. 2003;53:174–178. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2003.01451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lagorce-Pages C, Fabiani B, Bouvier R, Scoazec JY, Durand L, Flejou JF. Collagenous gastritis: a report of six cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1174–1179. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200109000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vakiani E, Arguelles-Grande C, Mansukhani MM, Lewis SK, Rotterdam H, Green PH, Bhagat G. Collagenous sprue is not always associated with dismal outcomes: a clinicopathological study of 19 patients. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:12–26. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maguire AA, Greenson JK, Lauwers GY, Ginsburg RE, Williams GT, Brown IS, Riddell RH, O’Donoghue D, Sheahan KD. Collagenous sprue: a clinicopathologic study of 12 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1440–1449. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181ae2545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Groisman GM, Meyers S, Harpaz N. Collagenous gastritis associated with lymphocytic colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1996;22:134–137. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199603000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castellano VM, Muñoz MT, Colina F, Nevado M, Casis B, Solís-Herruzo JA. Collagenous gastrobulbitis and collagenous colitis. Case report and review of the literature. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:632–638. doi: 10.1080/003655299750026128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freeman HJ. Topographic mapping of collagenous gastritis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15:475–478. doi: 10.1155/2001/243198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stolte M, Ritter M, Borchard F, Koch-Scherrer G. Collagenous gastroduodenitis on collagenous colitis. Endoscopy. 1990;22:186–187. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1012837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Billiémaz K, Robles-Medranda C, Le Gall C, Gay C, Mory O, Clémenson A, Bouvier R, Teyssier G, Lachaux A. A first report of collagenous gastritis, sprue, and colitis in a 9-month-old infant: 14 years of clinical, endoscopic, and histologic follow-up. Endoscopy. 2009;41 Suppl 2:E233–E234. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1077440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leiby A, Khan S, Corao D. Clinical challenges and images in GI. Collagenous gastroduodenocolitis. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:17, 327. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park S, Kim DH, Choe YH, Suh YL. Collagenous gastritis in a Korean child: a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2005;20:146–149. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2005.20.1.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pulimood AB, Ramakrishna BS, Mathan MM. Collagenous gastritis and collagenous colitis: a report with sequential histological and ultrastructural findings. Gut. 1999;44:881–885. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.6.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jin X, Koike T, Chiba T, Kondo Y, Ara N, Uno K, Asano N, Iijima K, Imatani A, Watanabe M, et al. Collagenous gastritis. Dig Endosc. 2013;25:547–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2012.01391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jain R, Chetty R. Collagenous gastritis. Int J Surg Pathol. 2010;18:534–536. doi: 10.1177/1066896908329588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kamimura K, Kobayashi M, Narisawa R, Watanabe H, Sato Y, Honma T, Sekine A, Aoyagi Y. Collagenous gastritis: endoscopic and pathologic evaluation of the nodularity of gastric mucosa. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:995–1000. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9278-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang HL, Shah AG, Yerian LM, Cohen RD, Hart J. Collagenous gastritis: an unusual association with profound weight loss. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:229–232. doi: 10.5858/2004-128-229-CGAUAW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stancu M, De Petris G, Palumbo TP, Lev R. Collagenous gastritis associated with lymphocytic gastritis and celiac disease. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:1579–1584. doi: 10.5858/2001-125-1579-CGAWLG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vesoulis Z, Lozanski G, Ravichandran P, Esber E. Collagenous gastritis: a case report, morphologic evaluation, and review. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:591–596. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mandaliya R, DiMarino AJ, Abraham S, Burkart A, Cohene S. Collagenous gastritis a rare disorder in search of a disease. GR. 2013;6:139–144. doi: 10.4021/gr564w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanabe J, Yasumaru M, Tsujimoto M, Iijima H, Hiyama S, Nishio A, Sasayama Y, Kawai N, Oshita M, Abe T, et al. A case of collagenous gastritis resembling nodular gastritis in endoscopic appearance. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2013;6:442–446. doi: 10.1007/s12328-013-0431-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soeda A, Mamiya T, Hiroshima Y, Sugiyama H, Shidara S, Dai Y, Nakahara A, Ikezawa K. Collagenous gastroduodenitis coexisting repeated Dieulafoy ulcer: A case report and review of collagenous gastritis and gastroduodenitis without colonic involvement. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2014:In press. doi: 10.1007/s12328-014-0526-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kobayashi M, Sato Y, Kamimura K, Narisawa R, Sekine A, Aoyagi Y, Ajioka Y, Watanabe H. Collagenous gastritis, a counterpart of collagenous colitis: Reveiew of Japanese case reports. Stomach and Intestine (Tokyo) 2009;44:2019–2028. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arnason T, Brown IS, Goldsmith JD, Anderson W, O’Brien BH, Wilson C, Winter H, Lauwers GY. Collagenous gastritis: a morphologic and immunohistochemical study of 40 patients. Mod Pathol. 2014:Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2014.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]