Abstract

A 2-year-old female child was referred from a private hospital as a case of recurrent lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI). The chest X ray revealed a hypoplastic right lung and further workup led to the diagnosis of esophageal lung - a rare type of communicating bronchopulmonary foregut malformation. A right posterolateral thoracotomy was done, anamolous bronchial communication with esophagus disrupted, esophageal fistula repaired and the lung resected. Postoperatively, diet was allowed from day 7. The patient tolerated the diet well. Repeat dye study revealed no leak and subsequently the patient was discharged on day 10.

KEY WORDS: Communicating bronchopulmonary foregut malformations, esophageal lung, esophageal bronchus, hypoplastic lung, pulmonary sequestration

INTRODUCTION

Communicating bronchopulmonary foregut malformations (CBPFMs) are uncommon anomalies characterized by a patent congenital communication between a portion of respiratory tract on one side and the esophagus or stomach on the otherside. CBPFMs can also occur in combination with other congenital anomalies involving the pulmonary and systemic vascular systems, diaphragm, upper gastrointestinal tract, and ribs and vertebrae. Esophageal lung is an extremely rare type of bronchopulmonary foregut malformation where a main stem bronchus, usually the right, is abnormally connected to the esophagus instead of the trachea.

CASE REPORT

A 2-year-old female child was presented with recurrent lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) and episodes of choking following food intake since the child was 10 months old. The patient had a history of repeated hospitalization for fever with productive cough and respiratory distress. The baby was a full term normal delivery (FTND) with no developmental delay; however, the height and weight of the child were below normal. The right hemithorax was smaller with crowded ribs along with bilateral subcostal retractions and air entry was absent. On auscultation, the apex beat of heart was on the right side.

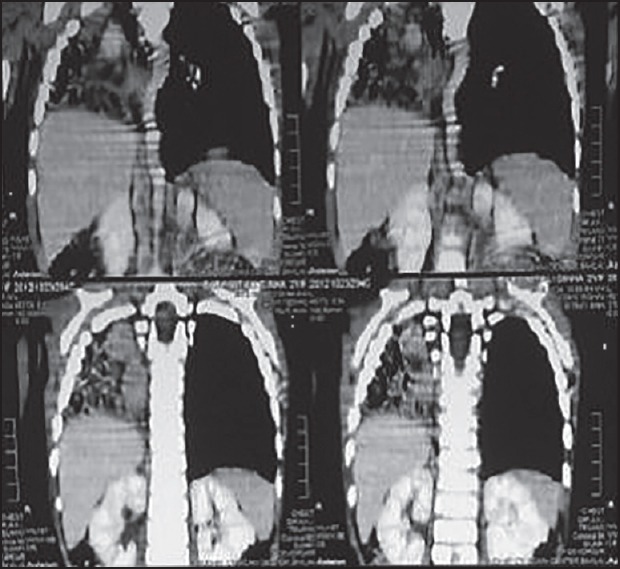

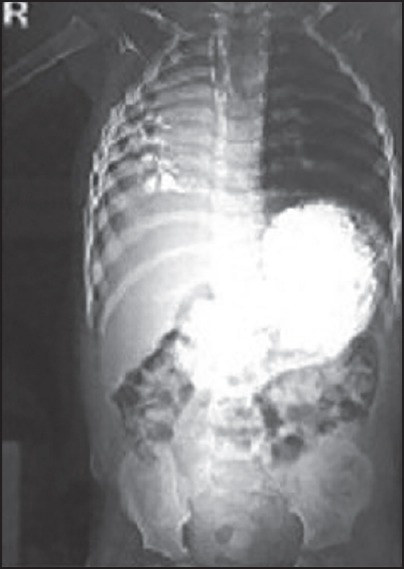

The shest X-ray showed hazy right hemithorax with mediastinal shift to the right side. Computed tomographic (CT) scan demonstrated right lung hypoplasia with total collapse [Figure 1]. A barium swallow study was done to rule out the possibility of a h-type tracheesophageal fistula (TEF). It revealed filling of right main bronchus directly from the esophagus [Figure 2]. A rigid bronchoscopy revealed a blind ended right bronchial stump and thus, a diagnosis of right esophageal lung was made.

Figure 1.

Pre operative CT thorax

Figure 2.

Dye study: Contrast in right lung

Exploration through a right posterolateral thoracotomy revealed a small right lung with liver like consistency and no aeration. Arterial supply was from the right pulmonary artery and was draining into the right pulmonary veins. Right main bronchus was of small caliber, not communicating with trachea and, instead, arose from the esophagus at a right angle. Right pneumonectomy with repair of esophagus at the site of bronchial communication was done.

The histopathology showed a hypoplastic lung with bronchus lined by respiratory epithelium. Postoperative course was uneventful and diet allowed from post operative day 2. The patient tolerated the diet well. A repeat dye study revealed no leak and subsequently the patient was discharged on post operative day 10.

DISCUSSION

Esophageal lung is an extremely rare type of bronchopulmonary foregut malformation where a main stem bronchus, usually the right, is abnormally connected to the esophagus instead of the trachea.[1]

Communicating bronchopulmonary foregut malformations (CBPFMs) are uncommon anomalies characterized by a patent congenital communication between a portion of respiratory tract on one side and the esophagus or stomach on the otherside.[2,3,4,5,6,7]

CBPFMs can also occur in combination with other congenital anomalies involving the pulmonary and systemic vascular systems, diaphragm, upper gastrointestinal tract, and ribs and vertebrae.[3,5]

Classification of CBPFMs into four groups based on anatomic features and the lung bud joining the esophagus.[6]

The first group comprises of an esophageal atresia, with the distal gastroesophageal tract originating from the trachea, a condition generally readily diagnosed in neonates.[5] One lung, lobe, or segment then arises from the distal esophagus. The three other groups encompass communicating malformations without esophageal atresia and with variable blood supply. Malformations in the second and the third groups are the most frequent, being reported in 33% and 46% of patients presenting with CBPFMs, respectively.[6]

In the second group, one whole lung originates from the esophagus and is generally termed an esophageal lung or accessory lung.[2] Ninety-five percent of esophageal lungs are right sided.[6] The ipsilateral main bronchus is absent, resulting in complete absence of ventilatory function of the involved lung that is hypoplastic and atelectated.

Malformations in the third group are characterized by a single lobe or segment arising from the esophagus or the stomach.[5] The bronchus originating from the gastrointestinal tract is classically called an “esophageal bronchus”.[7] Exceptional bilateral esophageal bronchi have also been reported.[2]

In the fourth group, there is a simple communication between a portion of the bronchial system and esophagus and a systemic vascular supply.[6]

Another classification of CBPFMs based on the morphology of the fistulous tract (neck, diverticulum, cyst) and the blood supply has also been proposed. The most common communications are between the mid or distal third of the esophagus and the right lower lobe (RLL) (43%), left lower lobe (LLL)(22%), or right main bronchus (RMB) (10%).

The clinical course of CBPFMs is generally insidious, including cough, recurrent pneumonia, and hemoptysis owing to chronic bronchopulmonary infection.[2,7]

Episodes of choking when swallowing liquids or the presence of food particles in sputum are suggestive and are reported in 65% of patients.[7] Nevertheless, the diagnosis is not made before adulthood in approximately 75% of cases.

Various hypotheses concerning the late diagnosis have been proposed, including a late onset or intermittence of symptoms or mild complaints leading to delayed investigation only after the development of complications. The late appearance of symptoms may result from the presence of a membrane or valve within the fistulous tract that subsequently ruptures or becomes incompetent.[4] The oblique upwards course of the fistula or the closure or contraction of the fistula occurs during swallowing.[4]

Diagnosis is usually made by barium esophagogaphy together with bronchial and esophageal endoscopy.[5]

In addition to the fistulous tract, CT may demonstrate bronchiectasis, rudimentary lung tissue, and zones of consolidation and fibrosis in the area “ventilated” by the anomalous bronchus and may also map vascular supply and drainage.[7]

Furthermore, three dimensional CT esophagography may help to reveal the communication and display complex anatomic features.

The differential diagnosis includes pulmonary sequestration, congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation (CCAM), and iatrogenic, inflammatory or neoplastic fistulas.[7] Treatment consists of either resection of the esophageal lung, or lobe, or anastomosis of the esophageal lung with the normal tracheobronchial tree when there is no severe bronchoparenchymal lesion and the vascular supply is normal.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sugandhi N, Sharma P, Agarwala S, Kabra SK, Gupta AK, Gupta DK. Esophageal lung: Presentation, management, and review of literature. J Paediatr Surg. 2011;46:1634–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerle RD, Jaretzki A, 3rd, Ashley CA, Berne AS. Congenital bronchopulmonary foregut malformation: Pulmonary sequestration communicating with the gastrointestinal tract. N Engl J Med. 1968;278:1413–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196806272782602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heithoff KB, Sane SM, Williams HJ, Jarvis CJ, Carter J, Kane P, et al. Bronchopulmonary foregut malformations: A unifying etiological concept. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1976;126:46–55. doi: 10.2214/ajr.126.1.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osinowo O, Harley HR, Janigan D. Congenital broncho-oesophageal fistula in the adult. Thorax. 1983;38:138–42. doi: 10.1136/thx.38.2.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leithiser RE, Jr, Capitanio MA, Macpherson RI, Wood BP. “Communicating” Bronchopulmonary Foregut Malformations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;146:227–31. doi: 10.2214/ajr.146.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Srikanth MS, Ford EG, Stanley P, Mahour GH. Communicating bronchopulmonary foregut malformations: Classification and embryogenesis. J Pediatr Surg. 1992;27:732–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(05)80103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verma A, Mohan S, Kathuria M, Baijal SS. Esophageal bronchus: Case report and review of the literature. Acta Radiol. 2008;49:138–41. doi: 10.1080/02841850701673391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]