Abstract

Our previous study revealed that serum deprivation upregulated human alkaline ceramidase 2 (haCER2) activity and mRNA in HeLa cells, but the mechanism remains unknown. In the present study, serum deprivation also upregulated haCER2 activity in HepG2 human hepatoma cell line cells due to an increase in haCER2 mRNA, in which mRNA transcription, not mRNA stability, is involved. Furthermore, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/activator protein-1 (AP-1) signaling pathway is involved in haCER2 mRNA upregulation by serum deprivation, and this mechanism may explain why haCER2 is upregulated in human liver cancer. In conclusion, p38 MAPK, AP-1 or haCER2 may be used as targets in liver cancer therapy.

Keywords: serum deprivation, HepG2 cells, human alkaline ceramidase 2, gene regulation, activator protein-1, mitogen-activated protein kinases, p38

Introduction

Ceramide, sphingosine and shingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) are three major metabolites of the sphingolipid signaling pathway. In response to various stresses, ceramide has been shown to mediate differentiation, growth arrest and apoptosis (1–5); sphingosine acts similarly to ceramide (6), and S1P has the opposite effects (7). Therefore, the balance between the intracellular levels of ceramide/sphingosine and S1P may determine the fate of a cell (8). It is well known that ceramide can be metabolized by ceramidases to generate sphingosine, which in turn can be phosphorylated by sphingosine kinases to form S1P. In addition to sphingosine kinases, ceramidases may play a pivotal role in the regulation of the intracellular ratio between ceramide, sphingosine and S1P (6). Based on optimal pHs and structures, ceramidase are classified into acid, neutral and alkaline ceramidase. Thus far, three alkaline ceramidases, such as alkaline ceramidase 1, 2 and 3, have been identified in humans (9). Human alkaline ceramidase 2 (haCER2), cloned by us (7), regulates sphingosine and S1P by controlling ceramides hydrolysis. Different expression levels of haCER2 have opposite effects; high expression of haCER2 caused sphingosine-induced growth arrest and low expression of haCER2 promoted S1P-mediated cell proliferation (7). Thus, regulation of haCER2 may affect the fate of a cell by controlling the balance of ceramide/sphingosine and S1P. In our previous study, serum deprivation upregulated haCER2 mRNA and activity, but the mechanism remains unknown. In the present study, the HepG2 human hepatoma cell line was used as a cell model and it was found that p38/activator protein-1 (AP-1) signaling is involved in serum deprivation-induced haCER2 transcriptional activation and subsequently caused an increase in haCER2 enzymatic activity.

Materials and methods

Cells and materials

HepG2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (HyClone Corp., Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone Corp.), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere at 37˚C and 5% CO2.

o-Phthalaldehyde was from Fluka (Milwaukee, WI, USA). D-e-C24:1-ceramide and D-e-C17-sphingosine were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc., (Pelham, AL, USA). Actinomycin D and 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA; an activator of AP-1) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). PD-98059 [inhibitor of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway], SP-600125 [inhibitor of the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway], SB-203580 [inhibitor of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway] and Bay117085 [inhibitor of nuclear factor-κ B (NF-κ B) pathway] were from Calbiochem/EMD Biosciences, Inc., (San Diego, CA, USA). AP-1 and NF-κ B Cignal Reporter were purchased from Qiagen (Valencia, CA, USA). Renilla luciferase reporter plasmid pRL-TK and the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay system were from Promega Corp., (Madison, WI, USA). SR11302 (AP-1 specific inhibitor) were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO, USA). Human p38 small interfering RNA (siRNA) (sc-29433), p38 primers for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) (sc-29433-PR) and p38 antibody (sc-7972) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The RNeasy Mini kit was from Qiagen (Santa Clarita, CA, USA) and the iScript cDNA Synthesis kit was purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., (Hercules, CA, USA). Other unlisted chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co., LLC.

haCER2 activity assays

haCER2 activity was determined by the release of sphingosine from ceramide as described previously (10). In brief, D-e-C24:1-ceramide was selected as a substrate dispersed into A buffer (pH 9.0), including 25 mmol/1 glycine-NaOH, 5 mmol/1 CaCl2 and 0.3% Triton X-100, by water bath sonication. The microsomes containing haCER2 from HepG2 cells were suspended in B buffer (pH 9.0), including 25 mmol/1 glycine-NaOH and 5 mmol/1 CaCl2. Incubation of the microsomes with ceramide substrate at 37˚C for 20 min initiated the enzymatic reactions, which were stopped by boiling the mixture. After Bligh-Dye extraction, sphingosine was assayed by high-performance liquid chromatography analysis with D-e-C17-sphingosine as an internal standard. HPLC was conducted using the Agilent 1050-HPLC model fitted with an eclipse XDB-C18 column (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). The solvent was methanol-potassium phosphate buffer (90:10 v/v) and the flow rate was 0.7 ml/min. A HP1046 fluorescence detector with an excitation at 345 nm and emission at 455 nm was used.

Reverse transcription-qPCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from HepG2 cells using the RNeasy Mini kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was reverse-transcribed into first-strand cDNA with the iScript cDNA Synthesis kit using 20 µ1 of the reaction mixture containing 1 µ1 iScript reverse transcriptase, 4 µ1 5X iScript reaction mixture and 0.5 µg total RNA. The complete reaction was cycled for 5 min at 25˚C, 30 min at 42˚C and 5 min at 85˚C using a PTC-200 DNA Engine (MJ Research Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) (11). cDNA was subjected to RT-qPCR analysis, which was performed on an iCycler system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). The initial PCR step was 3 min at 95˚C, followed by 40 cycles of a 10-sec melting at 95˚C and a 45-sec annealing/extension at 60˚C. The final step was 1-min incubation at 60˚C. All the reactions were performed in triplicate. Data are expressed as the mean normalized expression, which is directly proportional to the amount of haCER2 mRNA relative to the amount of β-actin mRNA. The primers used were forward, 5′-AGTGTCCTGTCTGCGGTTACG-3′; and reverse, 5′-TGTTGTTGATGGCAGGCTTGAC-3′ for haCER2; and forward, 5′CAATGTTCGGTGCAATTCAGAG-3′ and reverse, 5′-GGATCCCATTCCTACCACTGTG-3′ for β-actin (9).

mRNA stability analysis

HepG2 cells were plated in 12-well plates at a density of 0.4×106 cells/well overnight and treated with serum deprivation, followed by the addition of 10 µg/ml actinomycin D. HepG2 cells were harvested 2 h after the addition of actinomycin D and haCER2 mRNA was quantified using RT-qPCR as above.

Transfection and luciferase activity assay

HepG2 cells were transiently transfected with 1 µg AP-1 or NF-κ B Cignal Reporter for 24 h using FuGENE HD as the transfection reagent. The cells were cotransfected with the Renilla luciferase reporter plasmid pRL-TK (50 ng/106 cells) as an internal control. The cells were subsequently treated with serum deprivation for 8 h. Following the treatment, the cells were rinsed with cold PBS and lysed with the buffer from the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay system. Firefly and renilla luciferase levels were measured in a luminometer using the dual-luciferase reporter assay reagents according to the manufacturer's instructions. The firefly luciferase levels were normalized to the renilla luciferase levels.

Treatment of cells with the inhibitors of the signaling pathways

HepG2 cells were treated with serum deprivation in the absence or presence of 10 µM PD-98059, SP-600125, SB-203580 for 8 h. Following the treatment, haCER2 mRNA was quantified using qPCR.

Transfection of siRNA

In order to silence the p38 MAPK gene expression, the siRNA approach was used. The HepG2 cells were cultured for 24 h before the transfection was processed in 24-well plates with 40 nM siRNAs using Lipofectamine® 2000 (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA, USA). After a 24-h incubation with p38 siRNA or Con-siRNA, the HepG2 cells were cultured with or without serum deprivation for an additional 8 h and subsequently the cells were collected and haCER2 mRNA was quantified using RT-qPCR. p38 MAPK knockdown was confirmed by western blot analysis (12) and qPCR.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation, with a minimum of three independent experiments analyzed by Student's t-test or analysis of variance. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

haCER2 is upregulated by serum deprivation in HepG2 cells

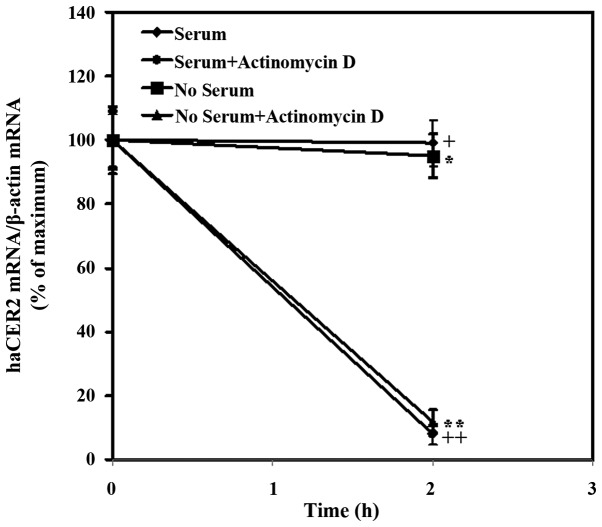

Our previous study revealed that haCER2 is upregulated by serum deprivation in HeLa cells; this prompted the investigation of whether the expression of the endogenous haCER2 was upregulated upon serum deprivation in HepG2 cells. In vitro activity assays showed that serum deprivation markedly increased alkaline ceramidase activity on D-e-C24:1-ceramide in a time-dependent manner, reaching a peak at 12 h (Fig. 1A). RT-qPCR analysis demonstrated that haCER2 mRNA was significantly upregulated in response to serum deprivation in a time-dependent manner and the increase plateaued at 8 h (Fig. 1B). These results indicate that serum deprivation upregulates haCER2 activity and mRNA. Comparing the kinetics of haCER2 activity and mRNA, it is indicated that the serum deprivation induced-haCER2 activity increase in HepG2 happens at mRNA level. Based on this kinetics study, haCER2 mRNA was measured at 8 h and haCER2 activity at 12 h in the subsequent studies.

Figure 1.

Human alkaline ceramidase 2 (haCER2) expression is upregulated by serum deprivation. HepG2 cells were grown to 80% confluence in serum-containing Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) prior to growth in the same medium or in serum-free DMEM. The cells were harvested at different time points following the medium change and subjected to (A) in vitro activity assays for haCER2 or total RNA was extracted from another portion of the above cells and subjected to (B) reverse transcription-quantitative PCR analysis. Data represent the mean value ± standard deviation of three independent experiments performed in duplicate. At the same time point, *,+P<0.05. MNE, mean normalized expression.

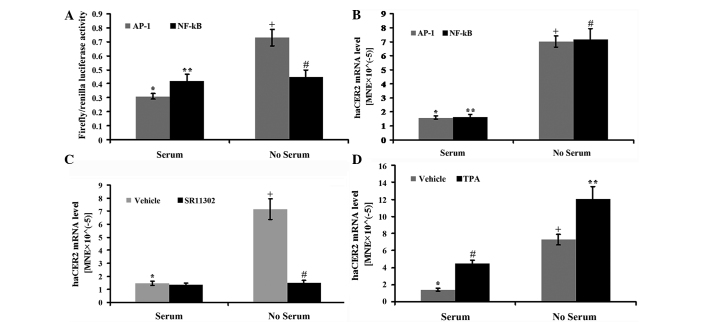

Transcription, but not mRNA stability, is involved in haCER2 upregulation in HepG2 cells by serum deprivation

The data above showed that haCER2 mRNA was upregulated by serum deprivation and it is well known that gene expression can be regulated at the transcriptional level or the post-transcriptional level. In the last years, it became evident that mRNA stability/turnover provides an important mechanism for post-transcriptional control of gene expression. Therefore, whether mRNA stability was involved in the regulation of haCER2 expression by serum deprivation was determined. In the present study, the inhibitory effect of actinomycin D, an inhibitor of transcription, on haCER2 transcription was confirmed by the finding that the treatment of cells with actinomycin D for 2 h reduced the haCER2 mRNA level by 92% in medium containing 10% FBS (Fig. 2). Furthermore, a result showed that in the presence of actinomycin D for 2 h, haCER2 mRNA level was observed to reduce by 88% in HepG2 cells treated with serum starvation (Fig. 2). Comparing the mRNA level in HepG2 cells exposure to actinomycin D for 2 h between serum starvation and 10% FBS treatment, it was indicated that serum deprivation-stimulated haCER2 upregulation was due to the transcriptional regulation and not mRNA stability.

Figure 2.

mRNA stability is not involved in serum deprivation-stimulated human alkaline ceramidase 2 (haCER2) upregulation. HepG2 cells were treated with serum deprivation for 6 h, followed by the addition of 10 µg/ml actinomycin D. The cells were harvested 2 h after the addition of actinomycin D and haCER2 mRNA was quantified using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. The data presented (means ± standard deviation) were from 1 of 2 experiments with similar results.+,++,*,**P<0.05.

AP-1 signaling is involved in haCER2 upregulation in HepG2 cells by serum deprivation

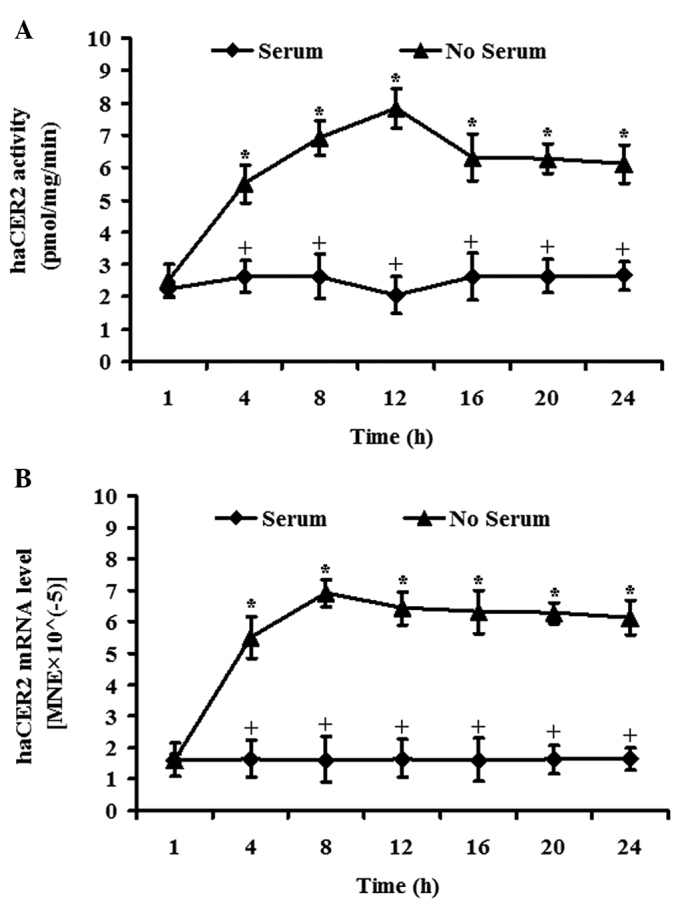

A previous study revealed that transcriptional factor AP-1 signaling regulated human neutral ceramidase gene transcription and the degree of decrease in ceramide mass was significantly greater compared to the reduction of human neutral ceramidase transcription, raising the possibility that AP-1 may regulate other ceramide metabolizing enzymes, including haCER2 (13). Therefore, in the present study, whether AP-1 regulated serum deprivation-induced haCER2 upregulation or not was investigated. In the first experiment, HepG2 cells were transfected with the luciferase reporter vectors constructed with either AP-1 or NF-κ B-binding element in the promoter. The results showed that serum deprivation stimulated AP-1 but not NF-κ B activity at 12 h (Fig. 3A). Consistent with the above results, haCER2 mRNA could be upregulated by serum deprivation in HepG2 cells transfected with AP-1 or NF-κ B (Fig. 3B). In addition, the AP-1 specific inhibitor SR11302 (14, 15) completely blocked the serum deprivation-induced haCER2 mRNA upregulation (Fig. 3C), and TPA, as an activator of AP-1 (16), has an additive effect on serum deprivation-induced haCER2 mRNA upregulation (Fig. 3D). Notably, in 10% FBS medium, TPA also stimulates haCER2 mRNA expression (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Activator protein-1 (AP-1) signaling is involved in human alkaline ceramidase 2 (haCER2) upregulation in HepG2 cells by serum deprivation. HepG2 cells were transfected with the DNA vectors constructed with AP-1 or the nuclear factor-κ B (NF-κ B)-binding element in the presence of FuGENE HD as a transfection reagent for 24 h. After the transfection, the cells were treated with serum deprivation for 8 h (for haCER2 mRNA) or 12 h (for luciferase activity) and collected for further analysis. (A) The AP-1 or NF-κ B activity was presented as the ratio of firefly luciferase vs. renilla luciferase activity (*,+P<0.05;**,#P>0.05) and (B) haCER2 mRNA was quantified using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR), (*,+P<0.05;**,#P<0.05). HepG2 cells were treated with (C) 1 µM SR11302 (*,+P<0.05;+,#P<0.05) or (D) 10 ng/ml 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) (*,+P<0.05;#,**P<0.05;*,#P<0.05;+,**P<0.05) in serum deprived medium or 10% fetal bovine serum medium for 8 h and haCER2 mRNA was measured by RT-qPCR. MNE, mean normalized expression.

p38 MAPK is involved in haCER2 upregulation in HepG2 cells by serum deprivation

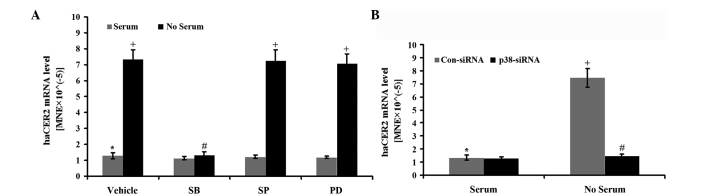

AP-1 transcriptional activity can be regulated by MAPK, including ERK, JNK and p38 MAPK signal transduction pathways (17). Thus, which one was involved in haCER2 upregulation by serum deprivation in HepG2 cells was determined. In the study, HepG2 cells were treated with serum deprivation in the presence of the pharmacological inhibitors of the MAPK pathways. The results showed that haCER2 upregulation by serum deprivation were inhibited by SB-203580, an inhibitor for the p38 MAPK pathway, but not by SP-600125 (an inhibitor for JNK) and PD-98059 (an inhibitor for ERK) (Fig. 4A). Consistent with this result, downregulation of p38 by specific siRNA completely inhibited haCER2 upregulation by serum deprivation (Fig. 4B). p38 MAPK knockdown was confirmed by western blot analysis and qPCR (data not shown). These data indicate that the p38 MAPK pathway is involved in haCER2 upregulation by serum deprivation.

Figure 4.

p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) may regulate human alkaline ceramidase 2 (haCER2) upregulation in HepG2 cells by serum deprivation. (A) HepG2 cells were treated with or without serum deprivation in the absence or presence of 10 µM SB-203580 (SB), an inhibitor for the p38 MAPK pathway; 10 µM SP-600125 (SP), an inhibitor for the JNK pathway; or 10 µM PD-98059 (PD), an inhibitor for the ERK pathway for 8 h. Subsequently the cells were collected and haCER2 mRNA was measured by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). (B) HepG2 cells were transfected with 40 nM p38 or scrambled small interfering RNA (Con-siRNA) for 24 h. The transfected cells were subsequently treated with serum deprivation for 8 h and collected for haCER2 mRNA measurement by RT-qPCR.*,+P<0.05;+,#P<0.05. MNE, mean normalized expression; JNK, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase.

Discussion

haCER2 plays an important role in cellular responses by regulating the hydrolysis of ceramides in cells (18). High and low ectopic expression of haCER2 leads to different cell fates through changing the ratio of ceramide/sphingosine and S1P (7). Therefore, the regulation of haCER2 expression by physiological or pathological stimuli is extremely important, but little is known regarding it. In the present study, firstly, serum deprivation was found to cause haCER2 activation in HepG2 cells in a time-dependent manner, which is in agreement with our previous finding conducted in HeLa cells (7). Comparing the kinetics of haCER2 activity and mRNA expression, it is indicated that haCER2 activity elevation was caused by increasing haCER2 mRNA. The level of an mRNA within a cell depends on its rate of synthesis and rate of decay (19). mRNA stability assay showed that actinomycin D, an inhibitor of transcription, completely inhibited the haCER2 mRNA increase caused by serum deprivation. Taking the above results together, it was indicated that serum deprivation-stimulated haCER2 mRNA elevation was due to the transcriptional regulation.

In response to a plethora of physiological and pathological stimuli, numerous gene regulation is mediated by AP-1 (20). A previous study suggested that human neutral ceramidase gene transcription is regulated by AP-1 signaling, it also raised the possibility that other ceramidases may be regulated by AP-1 as the degree of decrease in ceramide mass was significantly greater than the reduction of human neutral ceramidase transcription (13). Therefore, whether haCER2 gene transcription by serum deprivation is regulated by AP-1 signaling pathway was investigated. The results showed that serum deprivation stimulated AP-1 luciferase activity, whereas NF-κ B activity was not stimulated by serum deprivation. Notably, SR11302 (a specific inhibitor of AP-1) blocked serum deprivation-induced haCER2 mRNA increase, whereas TPA (an activator of AP-1) additively increased haCER2 mRNA with serum deprivation. All these data confirmed that transcription factor AP-1 is involved in haCER2 gene transcription by serum deprivation.

Three different types of MAPKs, including ERK, JNK and p38, contribute to the induction of AP-1 activity in response to a diverse array of extracellular stimuli (21). In the present study, the pharmacological inhibitors experiment revealed that SB-203580 blocked haCER2 transcription induced by serum deprivation, whereas SP-600125 and PD-98059 could not. These indicated that the p38 MAPK, and not JNK and ERK, pathway is involved in serum deprivation-induced haCER2 transcription. The involvement of the p38 MAPK pathway in haCER2 transcription mediated by serum starvation was further confirmed by p38-specific siRNA downregulation.

Notably, AP-1 is composed of the Jun protein family (c-Jun, Jun B and Jun-D) and the Fos protein family (such as c-Fos, FosB, Fra-1 and Fra-2) (20), and the present study does not identify which subunit(s) of AP-1 play a pivotal role in haCER2 transcription mediated by serum starvation and this is an area for future investigation.

A low-nutrient environment is commonly found in the central region of solid tumor, such as liver cancer (22, 23). Serum starvation mimics the tumor growth environment in vivo (24). In HepG2 cells, serum deprivation upregulated haCER2 expression in which the p38 MAPK/AP-1 signaling pathway is involved, and this mechanism may explain why haCER2 is upregulated in solid liver cancer (7, 25).

The regulation of mRNA stability is an important factor in modulating gene expression, and the p38 MAPK pathway has been indicated in the regulation of the mRNA half-lives of a number of genes (26). Based on the aforementioned studies, we hypothesized that mRNA stability may be involved in serum starvation-induced haCER2 mRNA increase, but mRNA decay experiments exclude this possibility and future research is required to explore this reason.

In conclusion, the present study conducted in the human HepG2 hepatoma cell line indicates that serum deprivation affects the p38 MAPK signaling pathway leading transcription factor AP-1 activation and subsequently regulates haCER2 mRNA expression. This mechanism may interpret why haCER2 is upregulated in liver cancer.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81360309), ‘Sphingolipids and Related Diseases’ Program for Innovative Research Team of Guilin Medical University, and Hundred Talents Program of Universities and Colleges Directly under the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region.

References

- 1.Spiegel S, Merrill AH., Jr Sphingolipid metabolism and cell growth regulation. FASEB J. 1996;10:1388–1397. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.12.8903509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merrill AH, Jr, Schmelz EM, Wang E, et al. Importance of sphingolipids and inhibitors of sphingolipid metabolism as components of animal diets. J Nutr. 1997;127(Suppl 5):S830–S833. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.5.830S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hannun YA, Obeid LM. The Ceramide-centric universe of lipid-mediated cell regulation: stress encounters of the lipid kind. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:25847–25850. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R200008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levade T, Malagarie-Cazenave S, Gouaze V, et al. Ceramide in apoptosis: a revisited role. Neurochem Res. 2002;27:601–607. doi: 10.1023/A:1020215815013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kolesnick R, Fuks Z. Radiation and ceramide-induced apoptosis. Oncogene. 2003;22:5897–5906. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuvillier O. Sphingosine in apoptosis signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1585:153–162. doi: 10.1016/S1388-1981(02)00336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu R, Jin J, Hu W, et al. Golgi alkaline ceramidase regulates cell proliferation and survival by controlling levels of sphingosine and S1P. FASEB J. 2006;20:1813–1825. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5689com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuvillier O, Pirianov G, Kleuser B, et al. Suppression of ceramide-mediated programmed cell death by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Nature. 1996;381:800–803. doi: 10.1038/381800a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu R, Sun W, Jin J, Obeid LM, Mao C. Role A of alkaline ceramidases in the generation of sphingosine and its phosphate in erythrocytes. FASEB J. 2010;24:2507–2515. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-153635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun W, Hu W, Xu R, et al. Alkaline ceramidase 2 regulates beta1 integrin maturation and cell adhesion. FASEB J. 2009;23:656–666. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-115634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin J, Zhang X, Lu Z, et al. Acid sphingomyelinase plays a key role in palmitic acid-amplified inflammatory signaling triggered by lipopolysaccharide at low concentrations in macrophages. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;305:E853–E867. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00251.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu Q, Lin L, Cheng Q, et al. The role of acid sphingomyelinase and caspase 5 in hypoxia-induced HuR cleavage and subsequent apoptosis in hepatocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1821:1453–1461. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Neill SM, Houck KL, Yun JK, Fox TE, Kester M. AP-1 binding transcriptionally regulates human neutral ceramidase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;511:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang C, Ma WY, Dawson MI, Rincon M, Flavell RA, Dong Z. Blocking activator protein-1 activity, but not activating retinoic acid response element, is required for the antitumor promotion effect of retinoic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5826–5830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.11.5826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li JJ, Westergaard C, Ghosh P, Colburn NH. Inhibitors of both nuclear factor-kappa B and activator protein-1 activation block the neoplastic transformation response. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3569–3576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisch TM, Prywes R, Roeder RG. An AP1-binding site in the c-fos gene can mediate induction by epidermal growth factor and 12-O-tetradecanoyl phorbol-13-acetate. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:1327–1331. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.3.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitmarsh AJ, Davis RJ. Transcription factor AP-1 regulation by mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways. J Mol Med (Berl) 1996;74:589–607. doi: 10.1007/s001090050063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun W, Jin J, Xu R, et al. Substrate specificity, membrane topology, and activity regulation of human alkaline ceramidase 2 (ACER2) J Biol Chem. 2010;285:8995–9007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.069203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bellofatto V, Wilusz J. Transcription and mRNA stability: parental guidance suggested. Cell. 2011;147:1438–1439. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hess J, Angel P, Schorpp-Kistner M. AP-1 subunits: quarrel and harmony among siblings. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5965–5973. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karin M. The regulation of AP-1 activity by mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16483–16486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.28.16483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harrington EA, Fanidi A, Evan GI. Oncogenes and cell death. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1994;4:120–129. doi: 10.1016/0959-437X(94)90100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dang CV, Semenza GL. Oncogenic alterations of metabolism. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:68–72. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(98)01344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiong Y, Fang JH, Yun JP, et al. Effects of micro RNA-29 on apoptosis, tumorigenicity, and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2010;51:836–845. doi: 10.1002/hep.23380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graveel CR, Jatkoe T, Madore SJ, Holt AL, Farnham PJ. Expression profiling and identification of novel genes in hepatocellular carcinomas. Oncogene. 2001;20:2704–2712. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frevel MA, Bakheet T, Silva AM, Hissong JG, Khabar KS, Williams BR. p 38 Mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent and -independent signaling of mRNA stability of AU-rich element-containing transcripts. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:425–436. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.2.425-436.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]