Abstract

Background

Exposure of Leishmania promastigotes to the temperature of their mammalian hosts results in the induction of a typical heat shock response. It has been suggested that heat shock proteins play an important role in parasite survival and differentiation.

Results

Here we report the studies on the expression of the heat shock protein 83 (HSP83) genes of Leishmania infantum. Confirming previous observations for other Leishmania species, we found that the L. infantum HSP83 transcripts also show a temperature-dependent accumulation that is controlled by a post-transcriptional mechanism involving sequences located in the 3'-untranslated region (3'-UTR). However, contrary to that described for L. amazonensis, the accumulation of the HSP83 transcripts in L. infantum is dependent on active protein synthesis. The translation of HSP83 transcripts is enhanced during heat shock and, as first described in L. amazonensis, we show that the 3'-UTR of the L. infantum HSP83 gene is essential for this translational control. Measurement of the steady-state levels of HSP83 transcripts along the promastigote-to-amastigote differentiation evidenced a specific profile of HSP83 RNAs: after an initial accumulation of HSP83 transcripts observed short after (2 h) incubation in the differentiation conditions, the amount of HSP83 RNA decreased to a steady-state level lower than in undifferentiated promastigotes. We show that this transient accumulation is linked to the presence of the 3'-UTR and flanking regions. Again, an 8-fold increase in translation of the HSP83 transcripts is observed short after the initiation of the axenic differentiation, but it is not sustained after 9 h.

Conclusions

This transient expression of HSP83 genes could be relevant for the differentiation of Leishmania, and the underlying regulatory mechanism may be part of the developmental program of this parasite.

Background

Leishmania parasites are dimorphic protozoa that pass through markedly different environments during their life cycle. The flagellated promastigote develops in the alimentary tract of the sandfly vector and is inoculated into a mammalian host during a blood meal. In the mammal, the parasite is phagocytosed by macrophages and switches to the amastigote form. After intracellular multiplication and cellular lysis, amastigotes enter other macrophages, spreading the infection. The molecular basis of the promastigote-to-amastigote transformation remains poorly understood although it is well established that several environmental factors such as pH and temperature trigger this cytodifferentiation process [1]. Indeed, a temperature upshift in vitro from 25° to 37°C, combined with acidification of the growth medium, is a sufficient stimulus to induce a promastigote-to-amastigote differentiation in several Leishmania spp. [2,3].

Early studies showed that exposure of Leishmania to temperatures typical of the mammalian host induces a stress response and synthesis of heat shock proteins (HSP), suggesting that HSP could be important players in the differentiation process [4]. Thereafter, genes coding for HSP have been cloned and extensively studied, mainly those coding for HSP70 and HSP83 [reviewed in [1]]. Given the conserved and universal nature of the heat shock response, heat shock genes provide a suitable model for studying the unusual features of gene expression in trypanosomes. In these early-branched eukaryotes, the RNA polymerase II transcription is not regulated and gene expression is exclusively controlled at the post-transcriptional level [5,6].

HSP70 and HSP83 genes are transcribed constitutively and their transcription is not induced by heat shock [7-9]. Instead, the HSP70 and HSP83 are synthesized at elevated rates during heat shock, indicating that the stress response in Leishmania is regulated exclusively at a post-transcriptional level [8]. Nevertheless, the induced synthesis of HSP70 and HSP83 does not increase significantly the steady-state levels of these proteins. This is probably due to the striking abundance of these proteins in unstressed Leishmania promastigotes: HSP70 and HSP83 make up to 2.1% and 2.8%, respectively, of the total protein [8]. The mechanisms regulating the HSP83 expression during heat shock in L. amazonensis has been examined in detail by Shapira and co-workers [7,10,11]. Transcripts for HSP83 accumulate upon temperature elevation by a post-transcriptional mechanism that induces variations in mRNA turn-over: the HSP83 transcript was rapidly degraded at normal temperatures, whereas heat shock leads to its stabilization. The fast decay of HSP83 mRNA at lower temperatures depended on active protein synthesis [7]. By transfection experiments with plasmid constructs, they found that the regulated decay of HSP83 mRNA is controlled by sequence or conformational elements present in both upstream and downstream untranslated regions (UTRs) [10]. Recently, they identified by deletion analysis a regulatory element located between positions 201 and 472 in the 3'-UTR of the HSP83 gene as responsible for the preferential translation of the HSP83 mRNA during heat shock [11].

In this work, we have carried out an analysis of the mechanisms of HSP83 gene expression in another Leishmania species, L. infantum. This species causes visceral leishmaniasis, a severe, often fatal, disease common in the Mediterranean basin and in Latin America [12]. We found that the L. infantum HSP83 mRNA accumulation and its enhanced translation during heat shock is driven by sequences located in the 3'-UTR, even though the translational efficiency is conditioned by the nature of the 5'-UTR. Noticeably, we found that the HSP83 mRNA abundance and the HSP83 translation rate show fluctuations along the promastigote-to-amastigote differentiation in L. infantum, reinforcing the postulated role for this protein in morphological differentiation of Leishmania [13].

Results and Discussion

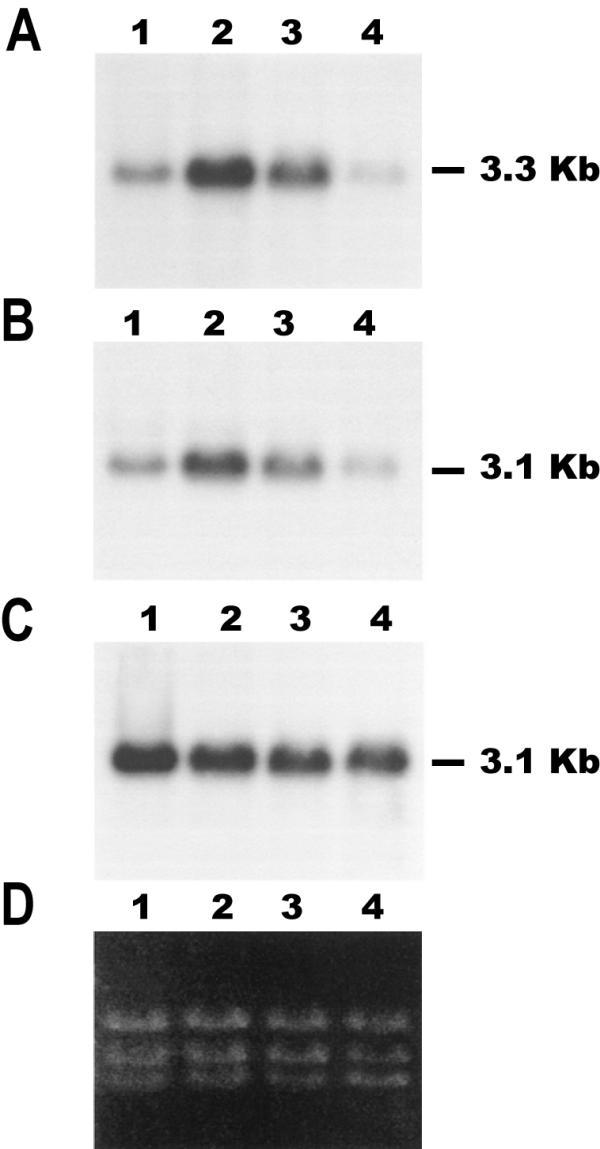

The HSP83 mRNAs of L. infantum are stabilized in response to a temperature increase

The HSP83 gene cluster in L. infantum is constituted by seven copies tandemly organized [16]. In order to analyze the expression of this gene cluster, RNA was extracted from promastigotes at mid-logarithmic phase of growth at 26°C, exposed 2 h at either 37°C, 39°C, or 41°C, and assayed by Northern blot using a probe derived from the L. infantum HSP83 gene (Fig. 1A). A transcript of 3.3-kb in size was present in promastigotes at 26°C, and exposure to mammalian temperatures (37°C) led to induction (three- to four-fold) in the steady-state level of these transcripts. Incubation of promastigotes at 39°C induced only a slight increase (1.7-fold) in the steady-state level of HSP83 transcripts. However, incubation of promastigotes at 41°C led to a 2.6-fold decrease in the steady-state level of HSP83 transcripts. Thus, the maximal accumulation of HSP83 transcripts was attained at 37°C, the temperature that promastigote encounters when infects a mammal. For comparison, the hybridization of the well-characterized HSP70 type-I and type-II transcripts was analyzed (Fig. 1B and 1C). While the abundance of the HSP70 type-I mRNAs increased by heat shock, the HSP70 type-II transcripts remained unaffected [9]. Maximal accumulation of HSP70 type-I mRNAs was attained at 37°C as well (Fig. 1). The drop of mRNA abundance for both HSP83 and HSP70 type-I mRNAs observed at 41°C seems to be specific since this treatment did not affect the levels of HSP70 type-II mRNAs. Also, Brandau et al. [8] reported that incubation of L. major promastigotes at 40°C leads to a decrease in the level of HSP83 mRNAs whereas the HSP70 remains unaffected.

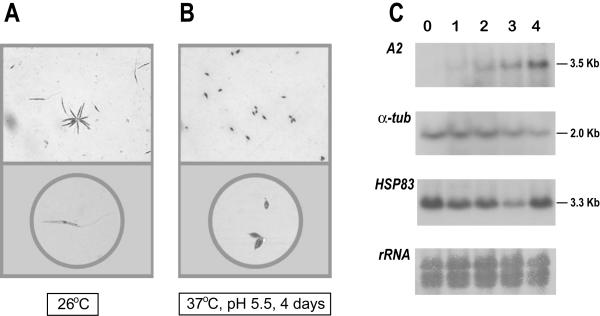

Figure 1.

Temperature-dependent accumulation of transcripts for HSP83 and HSP70. RNA samples were prepared from promastigotes grown at 26°C (lanes 1) or incubated for 2 h at 37°C (lanes 2), 39°C (lanes 3), or 41°C (lanes 4), and analyzed by Northern blotting. Northern blots were hybridized with the L. infantum HSP83 3'-UTR (panel A). The same blot was stripped and rehybridized with probes for the L. infantum HSP70 3'-UTR-I (panel B) and the L. infantum HSP70 3'-UTR-II (panel C) [9]. Panel D shows an ethidium bromide staining of the RNA samples loaded on agarose gel prior to transfer.

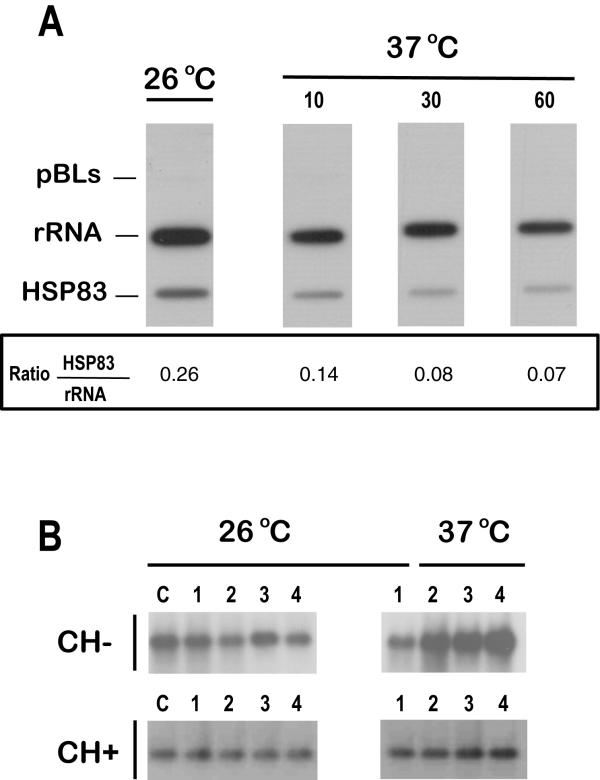

To assess whether the temperature-dependent accumulation of HSP83 mRNA was due to a mechanism involving either transcriptional control or post-transcriptional regulation, we performed run on assays (Fig. 2A). The experiments showed that the temperature treatment did not induce an increase in the transcription rate of the HSP83 gene cluster in L. infantum. This result is in agreement with a previous study by Brandau et al. [8] showing that transcription of HSP83 genes in L. major and L. donovani is not induced during a heat shock. A decrease in the rate of transcription of HSP83 genes relative to that of rRNA genes in parasites incubated at 37°C was observed (Fig. 2A); further studies will be needed to ascertain whether or not this decrease in transcriptional activity induced by temperature is specific for HSP83 genes. The increase in the HSP83 mRNA abundance and the lack of transcriptional regulation are in agreement with the results obtained in L. amazonensis [7]. However, in that work, it was suggested that the level of HSP83 mRNA could be controlled by a labile nuclease, which was active mainly at 26°C. Thus, the heat shock would lead to the stabilization of HSP83 transcripts by inhibition of that nuclease. We wanted to analyze whether a similar mechanism was responsible for HSP83 mRNA stabilization in L. infantum during heat shock. For this purpose, promastigotes were grown in the presence or absence of cycloheximide A (a drug that blocks protein synthesis by inhibiting translational elongation; 5 μg ml-1) and parasite cultures were incubated at either 26°C or 37°C for 1, 2 and 4 h (Fig. 2B). Remarkably, the addition of cycloheximide to parasites growing at 26°C did not result in an increase of the HSP83 mRNAs, contrary to that described for L. amazonensis HSP83 transcripts [7]. Instead, the presence of cycloheximide in promastigote cultures growing at 37°C abolished the temperature-dependent accumulation of the HSP83 transcripts (Fig. 2B). Similar results were obtained when the protein synthesis inhibitors puromycin or anisomycin were assayed (data not shown). Thus, it can be concluded that the observed stabilization at 37°C of HSP83 transcripts in L. infantum depends on on-going protein synthesis. Interestingly, a similar mechanism has been found to be responsible of the accumulation of the L. infantum HSP70 type-I mRNAs [9].

Figure 2.

The regulation of the HSP83 gene expression occurs at the post-transcriptional level. (A) Promastigotes of L. infantum were grown at 26°C, and parallel cultures were incubated at 37°C during 10, 30, and 60 min. Run-on transcripts, labeled with [32P]UTP, were hybridized to slot blots containing 5 μg of linearized plasmid DNAs. The following plasmids were used: pBLs, pBluescript; rRNA, pRIB (plasmid containing a 590-bp fragment of the L. infantum 24Sα rDNA gene [9]); HSP83, pE2 (plasmid containing a fragment of the 3'-UTR of L. infantum HSP83 gene). The values of the hybridization intensity were measured by densitometric analysis of the autoradiographs, and the ratio HSP83/rRNA is shown. Data represent the average of two separate experiments. (B) RNA samples were prepared from promastigotes cultures grown at either 26°C or 37°C for 0 h (lanes 1), 1 h (lanes 2), 2 h (lanes 3) and 4 h (lanes 4) in the presence (CH+) or absence (CH-) of cycloheximide. The drug was added 1 h prior to start the temperature treatment. Lanes C contain RNA samples prepared from parasite cultures before starting the drug treatment. The Northern blots were hybridized with a specific probe for the L. infantum HSP83 3'-UTR.

The 3'-UTR of the L. infantum HSP83 gene confers stability to a reporter transcript in response to a temperature increase

Most of the regulatory elements that control gene expression in Leishmania and other kinetoplastids have been located at the UTRs of the mRNAs, more frequently at the 3'-UTRs [17,21-24]. The boundaries of the 5'- and 3'-UTR of the HSP83 mRNA were defined by an RT-PCR approach (see Materials and methods for details). The trans-splicing acceptor site was located 290 nucleotides upstream from the beginning of the HSP83 ORF, and the polyadenylation site of the 3'-UTR was determined to be at nucleotide 896 from the stop codon (GenBank™/EBI Data Bank accession number X87770).

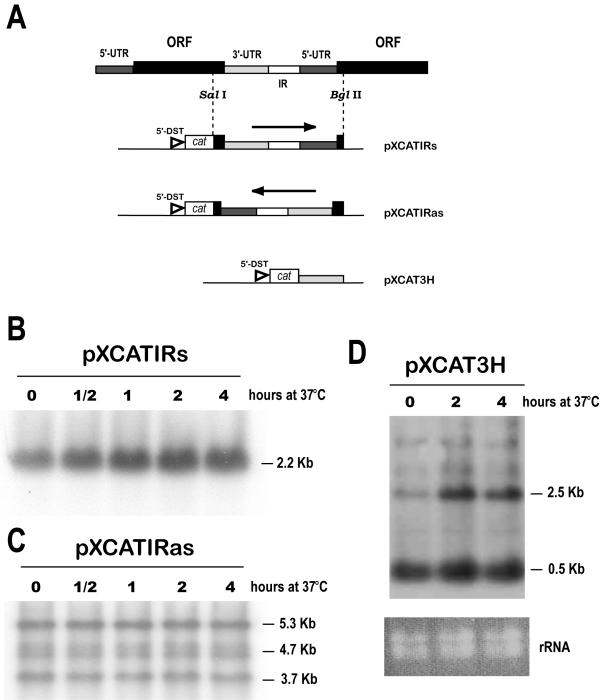

First, different pieces of sequence downstream the HSP83 ORF were appended to the cat reporter gene and cloned in a plasmid expression vector for Leishmania (for a scheme, see Fig. 3A). The abundance of cat RNA in stably-transfected promastigote lines cultured at 37°C was compared to the abundance in the same line cultured at 26°C (Fig. 3). When the complete 3'-UTR+IR+5'-UTR fragment was inserted downstream from the cat gene (construct pXCATIRs), it was found a temperature-dependent accumulation of the single cat transcript (Fig. 3B). However, this regulation was not observed when this region was inserted in the antisense orientation (construct pXCATIRas) with respect to cat ORF (Fig. 3C). To address the question whether the temperature-dependent accumulation of cat-3'UTR (HSP83) chimeric transcripts may be a result of an improved 3'-processing during heat shock or a specific stabilization of 3'-UTR (HSP83)-containing transcripts during heat shock, we made a new construct in which it was precisely cloned the 3'-UTR of L. infantum HSP83 gene (plasmid pXCAT3H; Fig. 3A). The Northern blot analysis of RNA from promastigotes transfected with pXCAT3H showed that several different sized cat transcripts are present (Fig. 3D). Remarkably, those transcripts containing the HSP83 3'-UTR, although polyadenylated within sequences derived from the pXCAT vector, maintained a heat-dependent accumulation. In contrast, a prominent 0.5-kb RNA species, whose molecular size indicates that it should be 3'-processed in a nucleotide position close to the cat ORF, did not accumulate during heat shock. It is predicted that the cat transcripts, derived from all the constructs shown in figure 3A, would start with the 5' terminus of the DST RNA (a sequence borne by pX-derivate plasmids that contains the mini-exon addition site [25]). In conclusion, these results indicate that the HSP83 3'-UTR seems to be responsible for the HSP83 mRNA accumulation during heat-shock. Furthermore, these results indicate that the accumulation of HSP83 transcripts does not seem to be a consequence of an improved 3'-end processing of the pre-RNAs during heat shock but a direct stabilization of HSP83 transcripts.

Figure 3.

Role of the 3'-UTR of the HSP83 gene in the temperature-dependent accumulation of transcripts. (A) Schematic representation of a portion of the L. infantum HSP83 gene cluster, showing the two most 5' genes of the cluster. The SalI+BglII genomic fragment was cloned in both orientations into pXcat plasmid to yield constructs pXCATIRs (sense) and pXCATIRas (antisense). Construct pXCAT3H was obtained by insertion of the 3'-UTR of HSP83 gene downstream of the cat ORF (see Materials and methods for cloning details). The position of the L. major DST sequence (5'-DST) [25], providing the miniexon addition site for the cat transcripts, is shown. Both pXCATIRs-transfected (panel B) and pXCATIRas-transfected (panel C) promastigotes were incubated either at 26°C or 37°C for 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, and 4 h; afterwards, RNA was extracted and used to prepare Northern blots that were hybridized with a cat probe. (D) RNA was extracted from pXCAT3H-transfected promastigotes after incubation at 37°C for various time points (0, 2, and 4 h). The Northern blot was hybridized with the cat probe. At the bottom, panel rRNA shows an ethidium bromide staining of the RNA samples loaded on the agarose gel.

Sequences within the 3'-UTR of HSP83 are required for enhanced translation at elevated temperatures

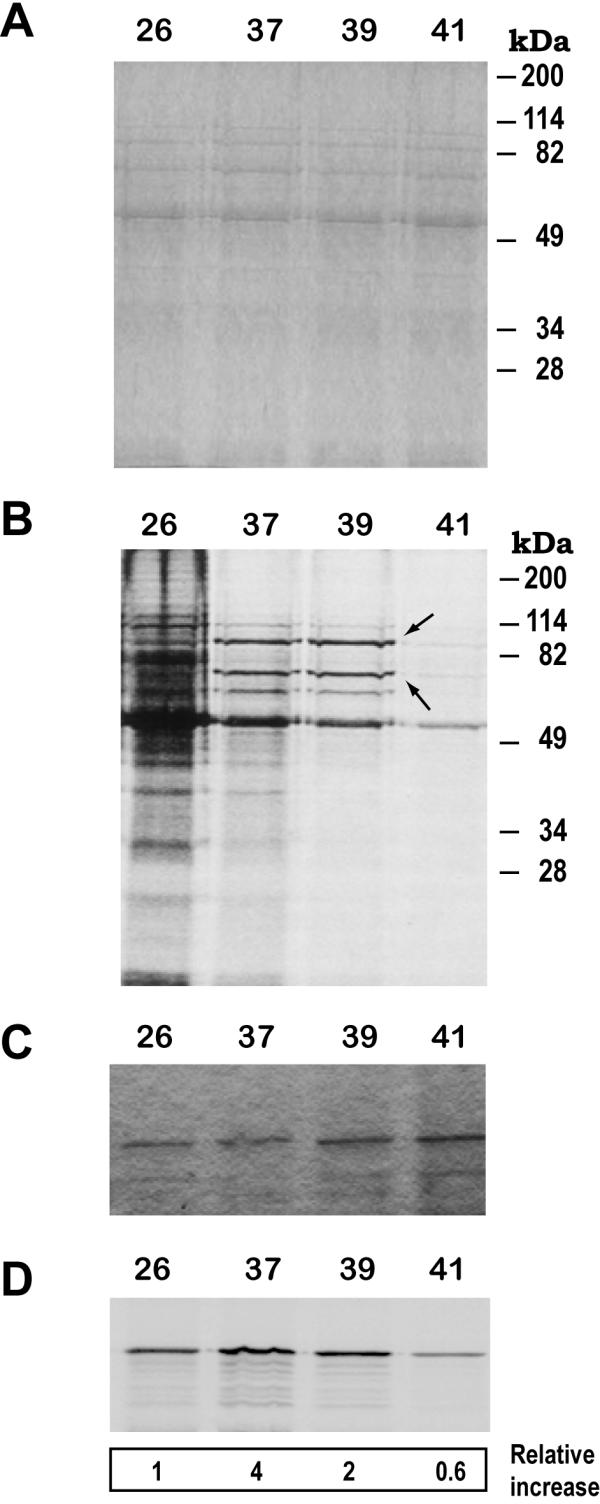

Leishmania promastigotes increase the synthesis of proteins HSP83 and HSP70 upon a temperature upshift [4,8]. However, this induction does not lead to a significant increase in the whole amount of these proteins [8]. Labeling experiments with L. infantum promastigotes showed an enhanced translation at 37°C and 39°C, but not at 41°C (Fig. 4), of two HSPs (putatively HSP83 and HSP70), whereas a general downshift of translation was seen in the total protein pattern. To ascertain whether the 90-kDa species corresponds to the HSP83, we performed a combination of metabolic labeling and immunoprecipitacion (Fig. 4C and 4D). After exposure of the immunoprecipitated band and densitometric analysis, it was found that heat stress at 37°C results in a 4-fold increase in the HSP83 synthesis relative to the amount detected at 26°C. Also, a 2-fold increase was observed in promastigotes incubated at 39°C, but increase was not observed at 41°C. It is noticeable the parallelism existing in the HSP83 mRNA accumulation at elevated temperatures (Fig. 1) and the enhanced translation of HSP83 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

The translation of HSP83 is enhanced in L. infantum promastigotes by incubation at 37°C and 39°C. L. infantum promastigotes were grown at either 26°C, 37°C, 39°C, or 41°C for 2 h in the presence of [35S]methionine/cysteine. Protein samples corresponding to 106 cells were separated over 10% SDS-PAGE and the gel was stained with Coomassie blue (panel A) and, subsequently, the labeled protein bands were revealed by autoradiography (panel B). On panel B, the position of putative HSP83 and HSP70 bands is indicated by arrows. In parallel, lysates from [35S]-labeled promastigotes incubated at the different temperatures were used to immunoprecipitate the HSP83 with specific antibodies. Immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE (panel C). After drying, the autoradiography of the gel was obtained (panel D). The ratio (expressed as relative increase) between incorporation of [35S] and the intensity of the protein band (stained by Coomassie blue) was determined. The data are averages of three independent experiments.

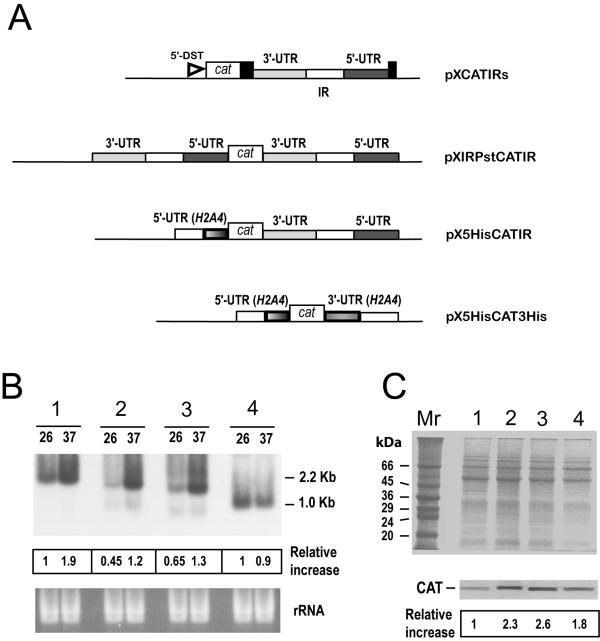

To examine the role of the HSP83 3'-UTR in the translational control, we prepared a set of chimeric cat constructs in order to transfect L. infantum promastigotes and to analyze de novo CAT synthesis. In addition to construct pXCATIRs (Fig. 5A), that contains the 3'-UTR and downstream sequences of the HSP83 gene (in this construct, the miniexon addition site is provided by the L. major 5'-DST sequence present in the pX63NEO derivatives [18,25]), we made a new construct in which the complete 3'-UTR+IR+5'-UTR was inserted both upstream and downstream from the cat ORF (plasmid pXIRPstCATIR; Fig. 5A), to provide both the HSP83 5'- and 3'-UTRs to the cat mRNA. The rationale for this construct was the hypothesis suggested by Shapira and co-workers in a recent work describing the regulation of HSP83 in L. amazonensis [11]; they indicate that the 5'-UTR alone cannot induce translation during heat shock, but it has a minor contribution when combined with the HSP83 3'-UTR. As controls, we made a construct in which the cat ORF was flanked by the 5'-UTR of the L. infantum H2A4 gene and the 3'-UTR and downstream sequences of the HSP83 gene (plasmid pX5HisCATIR; Fig. 5A), and the construct pX5HisCAT3His (cat ORF flanked by 5'-UTR and 3'-UTR from the LiH2A4 gene; Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

Analysis of the expression of cat transcripts and CAT protein in the different transfected Leishmania cell lines. (A) Schematic maps of the constructs. The CAT coding gene (open box) was cloned between different 5'-UTRs and 3'-UTRs. Where not indicated, the UTRs are derived from L. infantum HSP83 genes. Along with the UTRs, the corresponding IRs (open rectangles) were also included. The position of the L. major DST sequence (5'-DST) in construct pXCATIRs is indicated. (B) RNA samples from promastigotes transfected with pXCATIRs (1), pXIRPstCATIR (2), pX5HisCATIR (3), or pX5HisCAT3His (4), incubated for 2 h either at 26°C (lanes 26) or at 37°C (lanes 37), were assayed by Northern analysis using a cat probe. The bottom panel shows an ethidium bromide staining of the RNA samples loaded on the gel prior to transfer. The intensities of the hybridization bands were evaluated by densitometric analysis and expressed as a relative increase (giving an arbitrary value of 1 to the intensity found in lane 26 of pXCATIRs-sample). (C) SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining of protein extracts (4 × 106 cells per lane) from different promastigote lines grown at 26°C. The stable transfections used are: pXCATIRs (lane 1), pXIRPstCATIR (lane 2), pX5HisCATIR (lane 3), and pX5HisCAT3His (lane 4). The bottom panel shows a Western blot analysis; proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and incubated with an anti-CAT antibody (dilution 1:1000). The intensity of the bands was quantified by densitometric scanning and the normalized relative signals (relative increase) are shown. Data represent mean values from two independent experiments.

First, we determined the relative content of both cat transcripts and CAT protein in the promastigote cultures transfected with pXCATIRs, pXIRPstCATIR, pX5HisCATIR, and pX5HisCAT3His (Fig. 5B and 5C, respectively). As expected, the level of cat transcripts increased after heat treatment in promastigotes transfected with constructs containing the HSP83 3'-UTR (pXCATIRs, pXIRPstCATIR and pX5HisCATIR), but increase was not observed in promastigotes transfected with the construct pX5HisCAT3His, containing the H2A4 3'-UTR. Remarkably, it was observed that pXCATIRs-transfected promastigotes, accumulating more cat transcripts than pXIRPstCATIR- or pX5HisCATIR-transfected promastigotes, expressed a 2- to 3-fold lower amount of CAT protein than those transfected with either pXIRPstCATIR or pX5HisCATIR (Fig. 5B). Therefore, these results indicate that cat transcripts derived from pXCATIRs construct are poorly translated relative to cat transcripts expressed by the other constructs. It is conceivable that the different translational efficiencies are linked to differences in the 5'-UTRs.

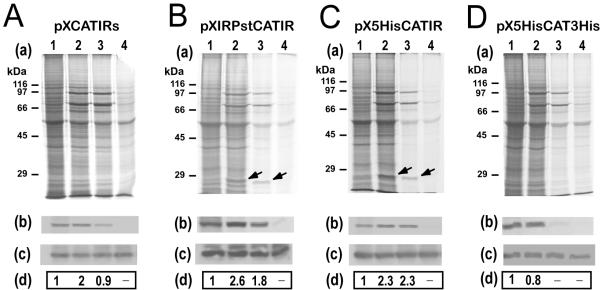

Labeling experiments with promastigotes transfected with pXIRPstCATIR or with pX5HisCATIR showed a temperature-dependent, enhanced translation of the putative CAT protein at 37°C or 39°C (Fig. 6B and 6C, respectively). This band was not evident in the de novo protein synthesis pattern of promastigote cultures transfected either with pXCATIRs or with pX5HisCAT3His (Fig. 6A and 6D, respectively). However, when immunoprecitation of the CAT protein was performed, the results indicated that this protein has an enhanced translation at 37°C in promastigotes transfected with pXCATIRs as well (Fig. 6A). The immunoprecipitation assays on pX5HisCAT3His-transfected promastigote lysates indicated that the synthesis of CAT does not increase in this cell line by heat incubation (Fig. 6D). Altogether, these data indicate that the sole presence of the HSP83 3'-UTR in transcripts is enough to confer enhanced translation at heat shock temperatures. Another interesting finding was that the HSP83 3'-UTR-containing transcripts are also translated at 39°C (Fig. 6A,6B,6C) as occurs with endogenous HSP83 transcripts (Fig. 4D). This feature was not observed in pX5HisCAT3His-transfected promastigotes (Fig. 6D).

Figure 6.

The HSP83 3'-UTR is essential for enhanced translation during heat shock. L. infantum promastigotes transfected with constructs pXCATIRs (A), pXIRPstCATIR (B), pX5HisCATIR (C), or pX5HisCAT3His (D) were metabolically labeled for 2 h at 26°C (lanes 1), 37°C (lanes 2), 39°C (lanes 3), or 41°C (lanes 4) in the presence of [35S]methionine/cysteine. Proteins (4 × 106 cells per lane) were separated by SDS-PAGE and the corresponding autoradiographies are shown (panels a). In parallel, cells were harvested and lysed, and the CAT protein was immunoprecipited using a specific antibody. Panel b shows the immunoprecipitation followed by autoradiography. Panel c shows the immunoprecipitation followed by Western blot using an anti-CAT antibody. The label intensity of the immunoprecipitated CAT protein (panels b) was measured by densitometric scanning and normalized relative to the total amount of immunoprecipitated CAT protein as determined by Western blot (panels c). The relative signals are shown in panels d. Data represent mean values derived from at least two independent experiments.

The HSP83 mRNA abundance transiently varied during the axenic promastigote-to-amastigote differentiation

In the past few years, successful methods for in vitro differentiation of promastigotes into amastigotes from several strains and species of Leishmania have been reported. Using a modification of the method of Saar et al. [2] to differentiate L. donovani, we induced L. infantum promastigotes to differentiate into axenic amastigotes. As shown in figure 7 (panels A and B), promastigotes exposed to pH 5.5 and 37°C differentiated to amastigote-shaped forms. Also, in parallel to the morphological differentiation, an increase in the steady-state level of A2 transcripts was detected (Fig. 7C); A2 transcripts are only expressed in amastigotes [26]. Given that temperature elevation is an important factor of the promastigote-amastigote differentiation, we analyzed the expression levels of HSP83 gene during the differentiation process (Fig. 7C). Unexpectedly, a decrease in the steady-state level of HSP83 transcripts was observed after one day of differentiation relative to the level in undifferentiated promastigotes. The HSP83 RNA level decreased further at day 3, showing a clear recovery at day 4.

Figure 7.

Differentiation of promastigotes to amastigotes in axenic conditions. Morphology of L. infantum promastigotes (A) and amastigote-like forms (B). Logarithmic promastigotes and amastigote-like forms (after 4 days of differentiation) were microscopically evaluated. Parasites were placed on slides and, after air dried, stained with DADE® Diff-Quik® (Baxter Diagnostics, Dudingen, Switzerland). The magnifications used to take the micrographs were: 400 × (top panels) and 630 × (bottom panels). (C) Expression of A2, α-tubulin, and HSP83 transcripts during differentiation of promastigotes to amastigotes. Promastigotes (lane 0) were differentiated to amastigotes (see Materials and methods for details). Aliquots of 5 × 107 cells were taken every 24 h (day 1, 2, 3, and 4) and used to extract RNA. The Northern blot was probed with the L. donovani A2 gene [26] and, after stripping, the blot was reprobed with the T. cruzi α-tubulin gene [38], and the 3'-UTR of the L. infantum HSP83 gene. A methylene blue staining of the blot is shown at the bottom (panel rRNA).

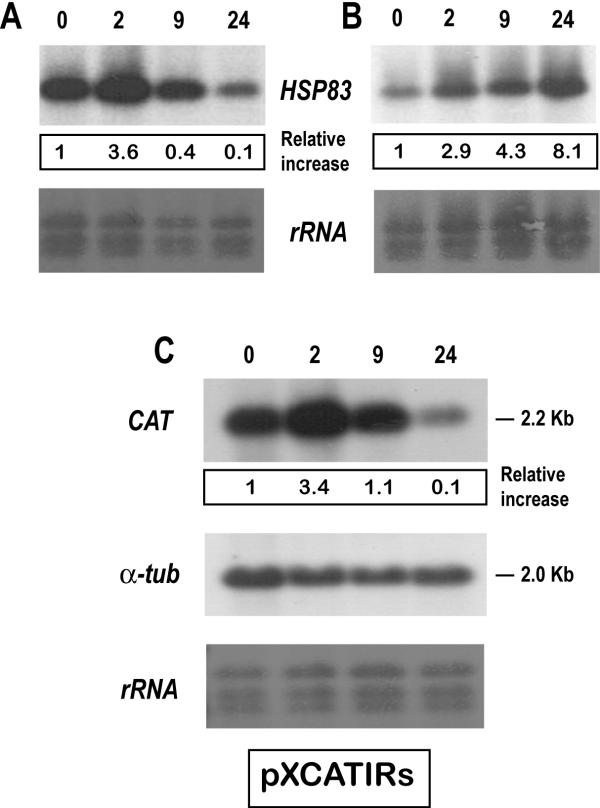

This result was rather surprising, since HSP83 transcripts accumulate in promastigotes after treatment at 37°C for 2 h (Fig. 1). To determine whether this decrease in the HSP83 RNA abundance was induced immediately after incubation in the axenic differentiation conditions, we analyzed the RNA expression at 2, 9 and 24 h after inducing differentiation (Fig. 8A). Interestingly, an increase in the steady-state level of HSP83 transcripts was observed after 2 h of incubation in the differentiation medium, but a drop in the HSP83 RNA abundance occurred at 9 h of differentiation, the steady-state level of HSP83 transcripts decreased further after 24 h of differentiation. HSP83 mRNAs from promastigotes exposed to 37°C (but not to acidic pH) were also analyzed in a Northern blot to compare the kinetics resulting from a simple exposure to a heat-shock to the kinetics occurring during differentiation (Fig. 8). The results showed that the HSP83 transcripts continuously accumulated under these conditions (Fig. 8B). Thus, the differentiation process induced a transient increase in HSP83 transcripts that was followed by a decrease to levels below that in promastigotes. However, this change did not seem to be due to a feed-back response induced by a prolonged heat shock, since this down-regulation was not observed in promastigotes continuously cultured at 37°C.

Figure 8.

Steady-state levels of HSP83 transcripts fluctuate during promastigote-to-amastigote differentiation. L. infantum promastigotes were cultured under amastigote growth conditions (panel A) or incubated at 37°C (panel B). RNA samples were prepared at various time points within the treatments (0, 2, 9 and 24 h), transferred onto a nylon membrane and hybridized with the HSP83 3'-UTR probe. C, pXCATIRs-transfected promastigotes were subjected to amastigote growth conditions for 0, 2, 9 and 24 h. The Northern blot was hybridized with the cat probe, and subsequently with the T. cruzi α-tubulin. Bottom panels show methylene blue staining of blots. The autoradiographs were quantified by densitometric scanning and normalized to the intensity at 26°C (arbitrary value 1). The data (relative increase) correspond to mean values derived from at least two independent experiments.

The involvement of the 3'UTR of the L. infantum HSP83 gene in the regulation of HSP83 RNA abundance during differentiation was analyzed using pXCATIRs-transfected parasites. As shown in Figure 8C, the relative abundance of cat transcripts varied in a similar manner to that of the HSP83 transcripts during the differentiation process. This suggests that the HSP83 3'-UTR contains the regulatory sequences responsible for the transient accumulation of the transcript.

A transient, preferential translation of HSP83 transcripts occurs during the promastigote-to-amastigote differentiation

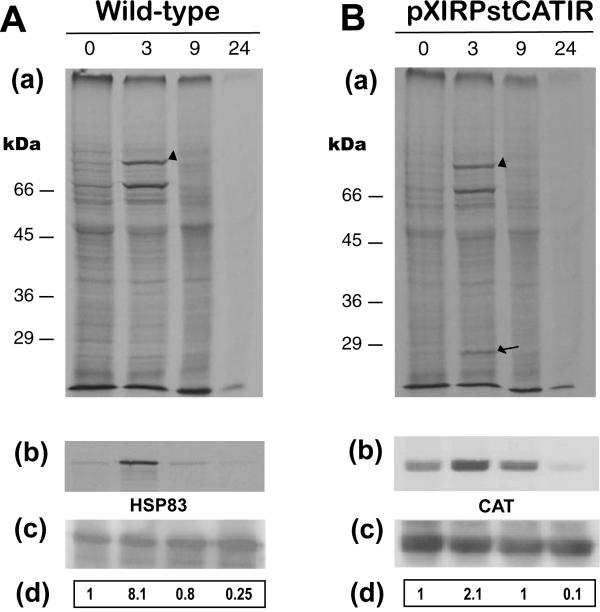

The observation that a transient increase in the steady-state level of the HSP83 transcripts, followed by a decrease, occurred during the promastigote-to-amastigote differentiation in axenic conditions, prompted us to study whether a preferential translation of these transcripts was also occurring concomitantly. We observed an increase in the synthesis of two protein bands by metabolic labeling (Fig. 9), that are likely to correspond to HSP70 and HSP83. After immunoprecipitation with an anti-HSP83 serum (Fig. 9A), an 8-fold increase in HSP83 de novo synthesis was observed after 3 h of incubation in amastigote differentiation conditions relative to the synthesis in promastigote cultures; at 9 h of differentiation the level of HSP83 synthesis was similar to that of promastigotes, and the rate of HSP83 synthesis decreased further after 24 h of differentiation. At 24 h of differentiation, a general decrease in protein synthesis was patent.

Figure 9.

The translation rate of the L. infantum HSP83 fluctuates during promastigote-to-amastigote differentiation. Wild-type (A) or pXIRPstCATIR-transfected (B) promastigotes were incubated during 0, 3, 9 and 24 h in amastigote growth conditions. The parasites were metabolically labeled with [35S]methionine/cysteine for the last 2 h of treatment. Proteins were extracted and analyzed by 10% SDS-PAGE, followed by autoradiography of the dried gels (panels a). The HSP83 band is marked with an arrowhead and the CAT band is marked with an arrow. The numbers at the left indicate the mobility and relative molecular weights (in kDa) of protein molecular weight standards. In parallel, cells were lysed and used to immunoprecipitate either the HSP83 (A) or CAT (B) using specific antibodies. Panels b show the immunoprecipitations followed by autoradiography; panels c show the immunoprecipitations followed by Western blotting. The label intensities of the immunoprecipitated proteins (panels b) were measured by densitometric scanning and normalized relative to the total amount of immunoprecipitated proteins (panels c). The relative signals are shown in panels d. Data represent mean values derived from at least three independent experiments.

In order to determine the involvement of regulatory cis-elements within the HSP83 UTRs, we analyzed de novo synthesis of proteins in an L. infantum cell line transfected with construct pXIRPstCATIR (Fig. 9B). A 2-fold increase of de novo CAT synthesis was observed in this cell line after 3 h of differentiation. Similar increases were determined in cell lines transfected either with pXCATIRs or with pX5HisCATIR, but not in parasites transfected with pX5HisCAT3His (data not shown), indicating that this preferential translation that occurs after 3 h of differentiation is linked to the presence of the HSP83 3'-UTR. However, it must be noticed that the increase of CAT synthesis was found to be lower than the increase determined for the endogenous HSP83.

The parallelism between accumulation of HSP83 transcripts (Fig. 8A) and de novo HSP83 synthesis (Fig. 9A) during the promastigote-to-amastigote differentiation suggest that both processes are linked in the same molecular mechanism.

Conclusions

The lack of transcription initiation control in kinetoplastid parasites reveals the importance of specific post-transcriptional processes in regulation of gene expression [5,6]. The heat shock genes have been classically studied as excellent models to study gene regulation in a broad range of organisms, including Leishmania [27]. The key advantage of this system is that the expression of HSP genes can be induced experimentally in promastigote cultures by raising the temperature. Results shown in this work revealed that L. infantum HSP83 gene expression is regulated post-transcriptionally by molecular mechanisms operating at two levels: i) accumulation of transcripts at 37°C; and ii) enhanced translation of HSP83 during heat shock. The stabilization of HSP83 transcripts in L. infantum during heat shock depended on active protein synthesis, suggesting that a temperature-activated protein factor is involved. This result is in contrast with a previous report in L. amazonensis in which, even though it was found that HSP83 transcripts accumulated upon temperature, the stabilization of the transcripts at elevated temperatures seemed the result of a heat-shock dependent, blocking effect on a specific mRNA degradation apparatus that is very active at 26°C [7]. Therefore, some differences in the stabilization mechanism of the HSP83 mRNA may exist for these two Leishmania species. Remarkably, the regulation of the HSP83 RNA stabilization was found to be similar to that described for the regulation of L. infantum HSP70 gene expression [9], suggesting that a common mechanism could be responsible for the regulation of both heat-shock genes in L. infantum. Another observation made in this study is that the temperature-dependent accumulation of L. infantum HSP83 transcripts is regulated by sequences located at the 3'-UTR. This data is in agreement with the studies in L. amazonensis that show that HSP83 mRNA stability is conferred by a sequence element in the 3'-UTR [11]. There is a growing number of Leishmania genes whose mRNA levels are stage-specific regulated by cis-elements within the 3'-UTRs [21,22,24,28].

The second level of regulation of HSP83 gene expression is through a translational control. As shown in this work and in other reports [8,11], translation of heat shock transcripts in Leishmania increases dramatically upon temperature elevation. Similar to the process of HSP83 mRNA stabilization during heat shock, sequences located in the 3'-UTR are needed to confer preferential translation to HSP83 transcripts. Also, the 5'-UTR of HSP83 mRNAs has an effect on the translational efficiency of these transcripts, even though it can be replaced with a 5'-UTR from a different gene. Thus, we have found that the presence of the L. infantum HSP83 or H2A 5'-UTR in the cat transcripts significantly increases the translation rate of the CAT protein (Fig. 6). In conclusion, our data and those of Zilka et al. [11] support a model in which the enhanced translation at elevated temperatures of Leishmania HSP83 transcripts is driven by sequences located exclusively in the 3'-UTR. There are several examples of mRNAs that are regulated at the translation level via elements in the 3'-UTR. It has been demonstrated for different organisms ranging from viruses to humans that the interaction of RNA-binding proteins with 5'- and 3'-UTRs of the mRNAs leads to an "RNA circularization" that increases translational efficiency; this structure allows a 3'-UTR-mediated translational control [reviewed in [29] and [30]].

The observation that the steady-state level of HSP83 transcripts varies during the axenic promastigote-to-amastigote differentiation is especially interesting. A rapid increase in the HSP83 RNA level was observed after 2 h of differentiation, but after 9 h the amount of HSP83 transcripts decreased to the initial level. After 24 h of differentiation, the HSP83 RNA level decreased further to levels lower than those present in promastigote cultures. This variation in the HSP83 RNA levels seems to be a consequence of incubating the parasites in differentiation growth conditions (37°C and pH 5.5), since promastigotes heat-shocked at 37°C along a 24-h period showed a continuously increased in the amount of HSP83 transcripts. The variations in HSP83 mRNA levels in the early steps of the differentiation process were accompanied by a drastic fluctuation in the de novo synthesis of HSP83 (Fig. 9). Thus, an 8-fold increase in the synthesis of HSP83 was observed after 3 h of differentiation relative to that observed in the promastigote forms. However, the rate of synthesis dropped to the initial level at 9 h of differentiation and was 4-fold lower after 24 h of differentiation than in promastigotes. In addition, it was demonstrated that the transient accumulation of HSP83 transcripts and the fluctuations in the de novo HSP83 synthesis during the promastigote-to-amastigote differentiation are driven also by the HSP83 3'-UTR. The parallelism in the regulation of Leishmania HSP83, both in heat shock and in differentiation, reinforce the general believe that temperature is a factor for differentiation in Leishmania [1].

An interesting question raised by the present data is whether the fluctuations in HSP83 gene expression observed during the axenic differentiation were reflecting a physiological reality or were only an experimentally induced artifact. Following experimental procedures of differentiation, in which environmental conditions that mimic the in vivo process are used [2,3], we differentiate L. infantum promastigotes into parasite forms that are morphologically similar to amastigotes. In addition, these axenic amastigotes express A2 transcripts, a product of the A2 gene family that is detectable only in fully differentiated amastigote forms [22,26]. Assuming that the amastigote-like forms obtained in this work represent truly L. infantum amastigotes, it is likely that the variations in HSP83 RNA and protein levels are relevant for the differentiation process of the parasite. In an outstanding work, Wiesgigl and Clos [13] showed that inactivation of L. donovani HSP83 (named HSP90 in that work) by geldanamycin or radicicol induces the differentiation from the promastigote to the amastigote stage. Thus, the decrease both in HSP83 RNA and in preferential translation of HSP83 transcripts observed after 9 h of differentiation could be a regulated cellular event that triggers the promastigote-to-amastigote differentiation. This finding supports the hypothesis that indicates that HSP83 homeostasis controls stage differentiation in Leishmania [13]. Increasing experimental evidence suggests that heat shock proteins HSP70 and HSP90 (=HSP83) interact with multiple key components of signaling pathways that regulate growth and development [31,32]. In particular, HSP90 is a molecular chaperone associated with the folding of signal-transducing proteins, such as steroid hormone receptors and protein kinases [33,34]. Pharmacologically impairment of the HSP90 has demonstrated that this protein is involved in several developmental pathways [35,36], leading to the suggestion that HSP90 is an evolutionary capacitor [37]. A revealing example of how fluctuations in HSP90 levels can affect a signal transduction pathway is found in the interaction of HSP90 with Ras/Raf-1 [[32] and references therein], a signaling pathway involved in cell proliferation and differentiation. The current model for HSP90/Raf-1 interaction suggests that HSP90 is essential for maturation of Raf-1, but it needs to be released for activation of Raf-1. Thus, naturally occurring variations in the expression levels of HSP90 may serve as a triggering factor for Raf-1 activation. In the case of Leishmania, taking into account the HSP90/Raf-1 interaction model and the HSP83 inhibition experiments in L. donovani [13], we can hypothesize that the variation observed in the levels of newly synthesized HSP83 during the promastigote-to-amastigote differentiation is a triggering factor of the Leishmania developmental program. Thus, a simplified picture on the involvement of HSP83 in the differentiation process can be depicted as follows. Initially, the heat stress, experienced by the promastigotes after transmission to the mammalian host, induces the synthesis of HSP83, which is needed for stabilizing partially denatured or newly synthesized regulatory proteins. Then, the inhibition of the HSP83 synthesis by an amastigote-specific mechanism leads to a decrease in chaperone capacity of the cell and, consequently, to the liberation of cellular regulators in an active conformation that triggers the differentiation program. Future studies based on this framework will help to elucidate the molecular role played by HSP83 (and other HSPs) in the Leishmania differentiation.

Methods

Parasites and treatments

L. infantum promastigotes (MCAN/ES/96/BCN150) were cultured at 26°C in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Paisley, UK) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) (Gibco), adding penicillin G (100 U ml-1) and streptomycin (0.1 mg ml-1). Logarithmic phase cultures (5–9 × 106 promastigotes ml-1) were used in all the experiments described. For heat shock experiments, L. infantum promastigotes were incubated at different temperatures (37, 39 or 41°C) for different periods of time. For axenic differentiation of L. infantum promastigotes, late logarithmic phase cultures (1–2 × 107 cells ml-1) were transferred to RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco) titrated to pH 5.5 by addition of 20 mM succinate (Sigma); the medium was supplemented with 25% FCS, penicillin G (100 U ml-1) and streptomycin (0.1 mg ml-1). Finally, parasites were incubated at 37°C (5% CO2). Under these conditions, promastigotes differentiated to amastigote-like forms within 96 h.

Transfections

Plasmid DNAs used in transfections were obtained with the Plasmid Maxy Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Transfection of L. infantum promastigotes was essentially performed as described previously [14]. Briefly, logarithmic phase promastigotes of L. infantum were harvested by centrifugation (1000 × g, 10 min) and resuspended at a density of 108 ml-1 in ice-cold EPB buffer (21 mM Hepes, pH 7.5, 137 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 0.7 mM Na2HPO4, and 6 mM glucose). Afterwards, 0.4 ml of cell suspension (4 × 107 promastigotes) were put into a 0.2-cm electroporation cuvette and chilled on ice for 10 min. Thirty μg of plasmid DNA were added and the cells were pulsed two times (500 μF, 2.25 kV cm-1) using a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser with a capacitance extender module. Afterwards, samples were transferred to 10 ml of RPMI medium supplemented with 20% FCS and incubated for 24 h at 26°C. After incubation in medium lacking antibiotics, transfected cell lines were selected in the presence of 20 μg ml-1 of geneticin (G418; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Stable cultures were obtained after 10–15 days of incubation at 26°C.

Northern blot analysis and nuclear run-on assays

Total RNA was isolated from L. infantum promastigotes using the Total Quick RNA Cells and Tissues kit (Talent, Trieste, Italy). Northern analysis of RNA samples was carried out by separation of RNA in 1% agarose-formaldehyde gels and transferred to nylon membranes using the Transfer Power Lid system (Hoefer, San Francisco, USA). DNA probes were labeled by nick-translation according to standard techniques [15]. Hybridization was performed as reported earlier [9]. For reuse, blots were treated with 0.1% SDS for 30 minutes at 95°C to remove the previously hybridized probes.

Nuclear run-on assays were performed as described [9] using freshly isolated nuclei of exponential-phase promastigotes. Nuclei were isolated from promastigotes grown at 26°C or additionally incubated at 37°C for 10, 30, and 60 min.

Mapping of RNA ends by RT-PCR

To determine the sites of poly(A)+ and spliced leader addition in the HSP83 transcripts, cDNA was generated by reverse transcription of total RNA using a (dT)18 primer that included the EcoRI restriction sequence (5'-CGGAATTCTT TTTTTTTTTT TTTTTT-3'). Reverse transcription steps were performed with MuLV reverse transcriptase (Perkin-Elmer Corp.) following the manufacturer's protocol (1 μg of total RNA per reaction). To determine the 3' boundary of the HSP83 transcript, a cDNA aliquot was PCR amplified using the following primers: forward, 5'-ATGTCCAAGA AGACGATGGC-3'; reverse, the (dT)18-attached primer (see above). To map the 5' end, the cDNA was PCR-amplified using the following primers: forward, 5'-GCTATATAAG TATCAGTTTC TGTAC-3' (derived from the Leishmania spliced leader sequence); reverse, 5'-TGCAGGTAAT ACTAATGGTT-3' (L. infantum HSP83 specific primer). PCR products were cloned into pSTBlue-1 vector (Novagen, Madison, WI) and sequenced to determine the HSP83 gene boundaries. The clone containing the 3' end of the L. infantum HSP83 gene was further digested with PstI and religated in order to eliminate coding sequences, this clone was named pE2 and the PstI-SalI insert was used as an HSP83 3'-UTR specific probe.

Plasmid constructs

The genomic clone gLiB1.2 [16], containing the 5'-end of the L. infantum HSP83 gene cluster, was digested with SalI, and the 3.8-kb restriction fragment was cloned in pUC18 to generate clone 10S. This clone was used as template to PCR-amplify different regions of the L. infantum HSP83 gene. The relevant regions of each construct were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

In order to obtain plasmids pXCATIRs and pXCATIRas, clone 10S was digested with BglII and BamHI and the 2.0-kb fragment was cloned, downstream from the cat ORF, into the BglII site of pXcat plasmid [17]. This genomic fragment comprises the 3'UTR, IR and 5'UTR sequences located between the first and the second HSP83 genes of the L. infantum gene cluster. Both orientations were selected: sense (pXCATIRs) and antisense (pXCATIRas). It should be noted that pXcat is a pX63NEO derivative [18], in which the cat ORF was inserted in the BamHI site of pX63NEO [17].

The following constructs were first generated in pBluescript KS (-) prior to subcloning into pX63NEO [18]. In these constructs, cat ORF was PCR-amplified from plasmid pC4cat [19] using the following primers: forward, 5'-GCGATATCAT GGAGAAAAAA ATCACTGG-3', and reverse, 5'-CCCAAGCTTA CGCCCCGCCC TGCCACT-3' (the sequence coding for the cat termination codon is indicated in italics). The PCR product was double digested with EcoRV+HindIII and cloned into pBluescript to generate plasmid pBlCAT. The 3'UTR region of HSP83 gene was amplified using the primers: forward, 5'-CCAAGCTTAG GTGGACTGAG CCGGTA-3', and reverse, 5'-GCGTCGACG GATCCGCGGG TTATTGCTTT GCATT-3'. The PCR product was double digested with HindIII+SalI and cloned into pBlCAT to generate plasmid pBlCAT3H. Finally, the cat-HSP83 3'-UTR insert was excised from pBlCAT3H as a BamHI fragment and subcloned into the corresponding site of pX63NEO to generate the construct pXCAT3H.

The region 3'UTR+IR+5'UTR located between coding regions of genes 1 and 2 of the HSP83 gene cluster was amplified with different pairs of primers in order to orientate the cloning. Thus, when this region was to be placed upstream the cat ORF, the following primers were used: forward, 5'-CGGGATCCCG CGCACTGCTC TTTACATT-3', and reverse, 5'-TGCCTGCAGC GTCTCCGTCA TGGTTGCAG-3'. After digesting the PCR product with BamHI+PstI, the 1407-pb band was cloned into pBlCAT to generate pBl-IRCAT. On the other hand, when this region was to be placed downstream the cat ORF, the following primers were used: forward, 5'-CCAAGCTTAG GTGGACTGAG CCGGTA-3', and reverse, 5'-GCGTCGACGG ATCCGCTCTC CGTCATGGTT GCAG-3'. The PCR product was digested with HindIII+SalI and cloned into pBl-IRCAT; after digestion with BamHI, the chimeric gene was cloned into pX63NEO to generate plasmid pXIRPstCATIR.

Control constructs were generated using regulatory regions derived from the L. infantum H2A gene cluster [20]. The 5'UTR along with upstream sequences were PCR-amplified using as a template the clone pS4KHE; this clone contains the H2A4 gene (GenBank™, EMBL and DDBJ accession number AJ419627) and was obtained by insertion of an EcoRI+HindIII genomic fragment, derived from L. infantum locus 2, into pBluescriptII. For amplification, the following primers were used: 5'-GTAAAACGAC GGCCAGT-3' (M13/pUC Sequencing Primer (-20), New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA), and 5'-GCGATATCCA TGGCTGCGAT GGGTAGGT-3' (derived from L. infantum H2A4 gene). The 590-bp PCR-product was digested with BamHI+EcoRV and cloned into pBlCAT to generate clone pBl5HisCAT. Afterwards, the 3'UTR+IR+5'UTR fragment derived from HSP83 gene cluster (see above) was cloned downstream cat gene to generate clone pBl5HisCATIR. Finally, the chimeric gene was excised by BamHI digestion and inserted into pX63NEO to yield the construct pX5HisCATIR.

The 3'UTR and downstream sequences derived from L. infantum H2A4 gene was PCR-amplified using the following primers: forward, 5'-CCATCGATGT CCTCCGGCCT GACAGCGC-3'; and reverse, 5'-GCGTCGACGG ATCCCATGGT TGCGGAAAGG AGAC-3'. The 639-bp PCR-product was double digested with ClaI+SalI and cloned into pBl5HisCAT to generate clone pBl5HisCAT3His. Finally, the insert was excised by BamHI digestion and cloned into pX63NEO to generate the construct pX5HisCAT3His. Further details on the sequence of the plasmids can be obtained from the authors upon request.

Metabolic labeling

After appropriate treatment, 3 × 107 parasites were collected and resuspended in 100 μl of DMEM without methionine (Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium, Met-; Gibco, Paisley, UK) supplemented with 10% of FCS. Parasites were pre-incubated at different temperatures or pHs for 30 min and then labeled with 100 μCi of [35S]methionine/cysteine protein labeling mix (Redivue Pro-mix L-[35S], >1000 Ci mmol-1; Amersham, Aylesbury, UK) and incubated 2 h further in the same conditions. After labeling, cells were harvested, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline, and lysed in SDS-polyacrylamide gel sample buffer. Incorporation of 35S was measured using the Liquid Scintillation Counter 1209 RacKbeta (Wallac, Turku, Finland). Samples of proteins corresponding to a similar number of cells were separated over 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels.

Immunoprecipitation

For immunoprecipitation of CAT, parasites (6 × 107 cells) were harvested by centrifugation, washed with PBS and treated with 100 μl of lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, and a protease inhibitor cocktail (1 mM PMSF, 8 μg ml-1 of leupeptin, 4 μg ml-1 of pepstatin and 4 μg ml-1 of aprotinin). The mixture was incubated at 4°C for 30 min with gentle shaking, and sonicated for 10 min. The lysates were microcentrifuged at 4°C for 15 min. Seventy-five μl of soluble proteins were incubated with 60 μg of rabbit anti-CAT serum (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 12 h at 4°C with gentle shaking. Fifteen μl of Protein A-agarose slurry (Sigma-Aldrich) were equilibrated in 50 μl of lysis buffer and added to the Leishmania extract-CAT antiserum mixture. After incubation on an orbital rotator for 1 h at 4°C, the beads were collected by centrifugation and washed three times in 0.4 ml of buffer A (10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 30 mM NaCl, and 2% Triton X-100), two times in 0.4 ml of buffer B (10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Triton X-100) and one time in 0.4 ml of buffer C (10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 0.05% Triton X-100). Finally, the beads were resuspended in 60 μl of Laemmli's buffer. Immunoprecipitated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE on acrylamide gels.

For immunoprecipitation of Leishmania HSP83, the following modifications were introduced: (a) the lysis buffer contained 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 10 mM EDTA (pH 8), 1% SDS, and the above indicated protease inhibitors; (b) after lysis, 75 μl of soluble proteins were mixed with 675 μl of ChIP buffer (0.01% SDS, 1.1% Triton X-100, 1.2 mM EDTA, 16.7 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.1), 167 mM NaCl, and the protease inhibitor cocktail) and 20 μl of anti-HSP83 rabbit serum [16].

Quantitative analysis

Coomassie blue-stained gels and autoradiographs were scanned with the GS-710 Calibrated Imaging Densitometer (Quantity One version 4.3.1; BIO-RAD). Measurements were performed under conditions in which a linear correlation existed between the amount of proteins or RNA and the intensities of the bands.

List of abbreviations

CAT, chloramphenicol acetyltransferase; HSP, heat shock protein; IR, intergenic region; kb, kilobase; ORF, open reading frame; UTR, untranslated region.

Authors' contributions

RL & MS carried out the construction of transfection plasmids; RL performed those experiments shown in Figures 1, 2, 3, 7 &8; MS & CF performed those assays shown in Figure 5; MS & DRA performed the immunoprecipation assays shown in Figures 4, 6 &9; LQ supervised the differentiation experiments and edited the manuscript; CA critically read the manuscript and gave laboratory support; JMR participated in the experimental design, provide supervision and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología Grant BMC2002-04107-C02-01. Also, an institutional grant from Fundación Ramón Areces is acknowledged.

Contributor Information

Ruth Larreta, Email: rlarreta@cbm.uam.es.

Manuel Soto, Email: msoto@cbm.uam.es.

Luis Quijada, Email: lquijada@cbm.uam.es.

Cristina Folgueira, Email: cfolgueira@cbm.uam.es.

Daniel R Abanades, Email: drabanades@cbm.uam.es.

Carlos Alonso, Email: calonso@cbm.uam.es.

Jose M Requena, Email: jmrequena@cbm.uam.es.

References

- Zilberstein D, Shapira M. The role of pH and temperature in the development of Leishmania parasites. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:449–470. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.002313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saar Y, Ransford A, Waldman E, Mazareb S, Amin-Spector S, Plumblee J, Turco SJ, Zilberstein D. Characterization of developmentally-regulated activities in axenic amastigotes of Leishmania donovani. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;95:9–20. doi: 10.1016/S0166-6851(98)00062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somanna A, Mundodi V, Gedamu L. In vitro cultivation and characterization of Leishmania chagasi amastigote-like forms. Acta Trop. 2002;83:37–42. doi: 10.1016/S0001-706X(02)00054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence F, Robert-Gero M. Induction of heat shock and stress proteins in promastigotes of three Leishmania species. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:4414–4417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.13.4414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiles JK, Hicock PI, Shah PH, Meade JC. Genomic organization, transcription, splicing and gene regulation in Leishmania. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1999;93:781–807. doi: 10.1080/00034989957781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton CE. Life without transcriptional control? From fly to man and back again. EMBO J. 2002;21:1881–1888. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.8.1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argaman M, Aly R, Shapira M. Expression of heat shock protein 83 in Leishmania is regulated post-transcriptionally. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1994;64:95–110. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandau S, Dresel A, Clos J. High constitutive levels of heat-shock proteins in human-pathogenic parasites of the genus Leishmania. Biochem J. 1995;310:225–232. doi: 10.1042/bj3100225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quijada L, Soto M, Alonso C, Requena JM. Analysis of post-transcriptional regulation operating on transcription products of the tandemly linked Leishmania infantum hsp70 genes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4493–4499. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aly R, Argaman M, Halman S, Shapira M. A regulatory role for the 5' and 3' untranslated regions in differential expression of hsp83 in Leishmania. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:2922–2929. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.15.2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilka A, Garlapati S, Dahan E, Yaolsky V, Shapira M. Developmental Regulation of Heat Shock Protein 83 in Leishmania. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47922–47929. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108271200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerin PJ, Olliaro P, Sundar S, Boelaert M, Croft SL, Desjeux P, Wasunna MK, Bryceson AD. Visceral leishmaniasis: current status of control, diagnosis, and treatment, and a proposed research and development agenda. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:494–501. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(02)00347-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesgigl M, Clos J. Heat shock protein 90 homeostasis controls stage differentiation in Leishmania donovani. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:3307–3316. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.11.3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBowitz JH. Transfection experiments with Leishmania. Methods Cell Biol. 1994;45:65–78. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61846-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2. Cold Spring Harbor: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Angel SO, Requena JM, Soto M, Criado D, Alonso C. During canine leishmaniasis a protein belonging to the 83-kDa heat-shock protein family elicits a strong humoral response. Acta Trop. 1996;62:45–56. doi: 10.1016/S0001-706X(96)00020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quijada L, Soto M, Alonso C, Requena JM. Identification of a putative regulatory element in the 3'-untranslated region that controls expression of HSP70 in Leishmania infantum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2000;110:79–91. doi: 10.1016/S0166-6851(00)00258-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBowitz JH, Cobura CM, Beverley SM. Simultaneous transient expression assays of the trypanosomatid parasite Leishmania using a-galactosidase and a-glucuronidase as reporter enzymes. Gene. 1991;103:119–123. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90402-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thummel CS, Boulet AM, Lipshitz HD. Vectors for Drosophila P-element-mediated transformation and tissue culture transfection. Gene. 1988;74:445–456. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90177-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto M, Quijada L, Larreta R, Iborra S, Alonso C, Requena JM. Leishmania infantum possesses a complex family of histone H2A genes: structural characterization and analysis of expression. Parasitology. 2003;127:95–105. doi: 10.1017/S0031182003003445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly BL, Nelson TN, McMaster WR. Stage-specific expression in Leishmania conferred by 3' untranslated regions of L. major leishmanolysin genes (GP63) Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2001;116:101–104. doi: 10.1016/S0166-6851(01)00307-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charest H, Zhang WW, Matlashewski G. The developmental expression of Leishmania donovani A2 amastigote-specific genes is post-transcriptionally mediated and involves elements located in the 3'-untranslated region. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17081–17090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beetham JK, Myung KS, McCoy JJ, Wilson ME, Donelson JE. Glycoprotein 46 mRNA abundance is post-transcriptionally regulated during development of Leishmania chagasi promastigotes to an infectious form. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17360–17366. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher N, Wu Y, Dumas C, Dube M, Sereno D, Breton M, Papadopoulou B. A common mechanism of stage-regulated gene expression in Leishmania mediated by a conserved 3'-untranslated region element. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:19511–19520. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200500200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBowitz JH, Coburn CM, McMahon-Pratt D, Beverley SM. Development of a stable Leishmania expression vector and application to the study of parasite surface antigen genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9736–9740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charest H, Matlashewski G. Developmental gene expression in Leishmania donovani: differential cloning and analysis of an amastigote-stage-specific gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2975–2984. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.5.2975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clos J, Krobitsch S. Heat shock as a regular feature of the life cycle of Leishmania parasites. American Zoologist. 1999;39:848–856. [Google Scholar]

- Myung KS, Beetham JK, Wilson ME, Donelson JE. Comparison of the Post-transcriptional Regulation of the mRNAs for the Surface Proteins PSA (GP46) and MSP (GP63) of Leishmania chagasi. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:16489–16497. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200174200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder B, Seshadri V, Fox PL. Translational control by the 3'-UTR: the ends specify the means. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:91–98. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie GS, Dickson KS, Gray NK. Regulation of mRNA translation by 5'- and 3'-UTR-binding factors. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:182–188. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmbrecht K, Zeise E, Rensing L. Chaperones in cell cycle regulation and mitogenic signal transduction: a review. Cell Prolif. 2000;33:341–365. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2184.2000.00189.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nollen EA, Morimoto RI. Chaperoning signaling pathways: molecular chaperones as stress-sensing 'heat shock' proteins. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:2809–2816. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.14.2809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan AJ. Hsp90's secrets unfold: new insights from structural and functional studies. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:262–268. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(99)01580-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter K, Buchner J. Hsp90: chaperoning signal transduction. J Cell Physiol. 2001;188:281–290. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford SL, Lindquist S. Hsp90 as a capacitor for morphological evolution. Nature. 1998;396:336–342. doi: 10.1038/24550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queitsch C, Sangster TA, Lindquist S. Hsp90 as a capacitor of phenotypic variation. Nature. 2002;417:618–624. doi: 10.1038/nature749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford SL. Between genotype and phenotype: protein chaperones and evolvability. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:263–274. doi: 10.1038/nrg1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares CMA, de Carvalho EF, Urmenyi TP, Carvalho JFO, de Castro FT, Rondinelli E. Alpha- and beta-tubulin mRNAs of Trypanosoma cruzi originate from a single multicistronic transcript. FEBS Lett. 1989;250:497–502. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)80784-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]