Abstract

Objectives

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) provides benefit for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in terms of quality of life (QoL) and exercise capacity; however, the effects diminish over time. Our aim was to evaluate a maintenance programme for patients who had completed PR.

Setting

Primary and secondary care PR programmes in Norfolk.

Participants

148 patients with COPD who had completed at least 60% of a standard PR programme were randomised and data are available for 110 patients. Patients had greater than 20 pack year smoking history and less than 80% predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 s but no other significant disease or recent respiratory tract infection.

Interventions

Patients were randomised to receive a maintenance programme or standard care. The maintenance programme consisted of 2 h (1 h individually tailored exercise training and 1 h education programme) every 3 months for 1 year.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire (CRQ) (primary outcome), endurance shuttle walk test (ESWT), EuroQol (EQ5D), hospital anxiety and depression score (HADS), body mass index (BMI), body fat, activity levels (overall score and activity diary) and exacerbations were assessed before and after 12 months.

Results

There was no statistically significant difference between the groups for the change in CRQ dyspnoea score (primary end point) at 12 months which amounted to 0.19 (−0.26 to 0.64) units or other domains of the CRQ. There was no difference in the ESWT duration (−10.06 (−191.16 to 171.03) seconds), BMI, body fat, EQ5D, MET-minutes, activity rating, HADS, exacerbations or admissions.

Conclusions

A maintenance programme of three monthly 2 h sessions does not improve outcomes in patients with COPD after 12 months. We do not recommend that our maintenance programme is adopted. Other methods of sustaining the benefits of PR are required.

Trial registration number

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study addresses an important clinical issue: the effects of pulmonary rehabilitation are short lived.

A well conducted randomised controlled study of maintenance sessions following pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

This study was adequately powered to detect a clinically relevant difference in a respiratory-related, health-related quality of life tool the Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire.

The intervention was not intensive enough, did not start early enough and was not of sufficient duration demonstrate a clinically relevant change.

Activity was assessed using questionnaires rather than measured directly using accelerometers.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major healthcare problem, with considerable human and economic costs. It is estimated that 3 million people in the UK have COPD and costs the National Health Service nearly £1 billion per year.1 COPD is a leading cause of death worldwide,2 is relatively unresponsive to treatment and is expected to have greater prevalence, morbidity and mortality in the future.3 However, pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) is an available therapeutic option with good evidence of benefit for patients in terms of quality of life and daily functioning4 and it is recommended in national and international guidelines.5 6

Although there is convincing evidence that PR offers clinically relevant benefit for patients in the short to medium term (6 months to 1 year), all studies have shown that the initial benefits diminish over time.6 Guidelines highlight the importance of continued exercise following PR; however, the utility of maintenance programmes is unclear. Current American PR guidelines5 state “the role of maintenance [PR] interventions…remains uncertain at this time” and there no specific recommendations about maintenance in the UK guidelines.6 Indeed there is a great variation in the delivery of PR, with only a third of UK centres offering any formal follow-on care or training after the initial PR programme,7 highlighting the need for more research in this area.

Previously, researchers have explored the utility of maintenance sessions and a recent meta-analysis has shown that intensive maintenance sessions have shown medium-term benefits in terms of exercise capacity.8 However, the majority of studies included in this analysis required that patients attend PR sessions on a weekly basis for a prolonged period of time. Indeed there is confusion as to whether these are maintenance programmes or continuation of the initial PR programme.6 In view of the considerable resource implications of intensive maintenance or continual programmes for all dyspnoeic patients with COPD we aimed to evaluate the long-term effect of a low-intensity (3 monthly) maintenance programme in terms of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in patients who had completed an initial PR programme. We also explored secondary end points that are relevant to patients with COPD, including exercise capacity, anxiety and depression, body mass index and fat-free mass, activity levels and exacerbations.

Methods

Design

This was a randomised, controlled, parallel, investigator-blind study of a maintenance programme in patients with COPD following a standard PR programme. Patients were recruited from primary and secondary care PR programmes in Norfolk, UK between July 2009 and November 2011. The study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice and all participants gave written informed consent.

Patients

Eligible patients were aged over 35 years, had a physician labelled diagnosis of COPD, emphysema or chronic bronchitis with a >20 pack-year smoking history and a forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) of <80%. Patients were excluded if they had significant cardiac or pulmonary disease other than COPD, a myocardial infarction within the previous 6 months or unstable angina, respiratory infection (defined as cough, antibiotic use or purulent sputum within 4 weeks prior to randomisation), severe or uncontrolled comorbid disease, or abnormalities in cognitive functioning that would limit the patient's ability to undertake the intervention. To enter the randomised part of the study, patients had to have completed at least 60% of the sessions in the initial PR programme.

All patients underwent the current PR programme offered within Norfolk. This consists of eight weekly supervised exercise training sessions. Each session consisted of 1 h of strength and endurance training including walking, cycling, standing from sitting, arm exercises using dumbbells and step-ups. These are high-intensity sessions with patients being expected to exercise at 85% of their maximum capacity. Prior to, or following each exercise training session, patients attended an educational session for 1 h. This was in the form of a seminar and included the following topics: relaxation, physiology, medication, emotions, nutrition, coping skills, social services and maintenance techniques. In addition patients were asked to undertake endurance exercises every day, and strength exercises two more times a week at home as this has been shown to be as beneficial as twice weekly supervised sessions.9

Eligible patients were randomised after baseline post-PR measure on a 1:1 basis using a computer generated randomised sequence to either of the following.

Maintenance programme

This consisted of one session, of 2 h duration, conducted every 3 months comprising 1 h of education and 1 h of exercise training. The sessions were supervised, individually tailored and included strength and endurance training given the importance of these components.10–12 The sessions took place in the same gynmasium as the initial PR programme and for the majority of patients by the same PR multidisciplinary team. The groups comprised the same patients as in the initial PR programme to maximise peer support and improve adherence.13 The maintenance programme was a rolling programme for the duration of the study and the number of participants in the group varied between 4 and 10 individuals. Patients received a reminder letter 2 weeks before the session and a reminder phone call 1 week before the session. As with the initial programme, patients received an individually tailored exercise prescription, to be undertaken at home, which was reviewed at each session and modified as appropriate. This was in addition to the standard advice to undertake strength and endurance exercises at home and an invitation to attend the Norwich Breathe Easy Group. There was no formal phone call or other review/follow-up between the sessions.

The education sessions were entitled ‘Keeping Well’ (including topics such as smoking cessation, healthy eating, the importance of exercise and techniques for managing exacerbations), ‘Keeping Active’ (including coping with breathlessness, revision of exercise strategies, a brainstorm/group discussion on different strategies and overcoming the barriers to activity) and ‘Keeping Going’ (including psychological issues of a long-term condition, dealing with psychological problems, methods of being able to relax and how carers can help). They were repeated in 9 monthly cycles so that all patients underwent each education session once.

The exercise training comprised supervised strength and endurance training including walking, cycling, standing from sitting, arm exercises using dumbbells and step-ups. The training was individually tailored to the patients’ abilities and patients received a written report on their progress with positive re-enforcement being provided by demonstrating the extent to which they had improved during the initial programme if appropriate. Patients were encouraged to review and reset their personal goals. The groups comprised of patients who attended the initial PR session where possible and time was permitted for social interaction and peer support.

Control

Patients received the standard advice to undertake strength and endurance exercises at home and an invitation to attend the Norwich Breathe Easy Group.

Randomisation was undertaken by an independent researcher (CB), using the code generated by the statistician, who had no role other than this in the study and had no knowledge of the patients’ details or characteristics. This researcher mailed letters to the patients informing them of their allocation group and inviting those in the intervention group to attend the maintenance PR sessions.

Measurements

Prior to enrolment in the PR programme, all patients underwent standard baseline assessments. These included demographic details, medical history, height and weight, spirometry, an incremental shuttle walk test (ISWT)14 to determine a predicted maximum oxygen consumption (VO2 max), an endurance shuttle walk test (ESWT)15 at 85% of VO2 max, the CRQ,16 EuroQol (EQ5D),17 hospital anxiety and depression score (HADS),18 and skinfold thickness measured at four sites (biceps, triceps, subscapular and suprailiac). At the end of PR and, for those entering the clinical study, 12 months following randomisation, patients underwent ESWT at the same rate as baseline, CRQ, EQ5D, HADS, height and weight, skinfold thickness and an assessment of activity in the preceding month.

At 3, 6 and 9 months following randomisation patients completed the CRQ and a questionnaire to assess activity in the preceding month. Activity levels were recorded as an overall score on a visual analogue scale (from 0 to 100) and also from intensity and duration of activity recorded on a daily exercise diary. Details of exacerbations and hospitalisations were also captured from patient questionnaires retrospectively every 3 months. All of the questionnaires were collected by post. Vital status was obtained from hospital records.

Baseline measurements were undertaken by the PR team and outcome measurements were undertaken by a research team (AMW, HW, SR) who were blind to the intervention. We used a standard protocol for the ESWT to reduce inter observer bias.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome was the change from baseline in the dyspnoea domain of the CRQ score at 12 months. A sample size of 98 patients had 80% power to detect a treatment difference, at a two-sided 5% significance level, of 0.5 units in the dyspnoea domain of the CRQ, which is considered to be a clinically significant difference.19 This was based on a two-sample t test and on the assumption that the SD was 0.87 units obtained from unpublished local pilot data. Secondary outcomes were the change from baseline in other domains of the CRQ, ESWT, body mass index (calculated as weight divided by the square of the height), body fat (calculated from skin fold thickness as previously described),20 HADS and EQ5D questionnaire. Metabolic equivalents of energy were calculated by multiplying the intensity of exercise by the exercise duration from the daily exercise diary. Analysis was on the intention-to-treat principle with any drop-outs being replaced using imputation. This was undertaken by Iteratively Chain Equations imputing using the values of all observed baseline and post-baseline outcome measures as well as treatment group. A total of five imputed data sets were constructed and the results were combined using Rubin’s equation. An a priori PPl analysis was undertaken including those patients who attended all of the maintenance sessions and provided data for the final outcome measures. Continuous outcomes were assessed by the two-sample t test. Exacerbation and hospitalisation rates were analysed using a negative binomial regression model.

Results

Baseline characteristics

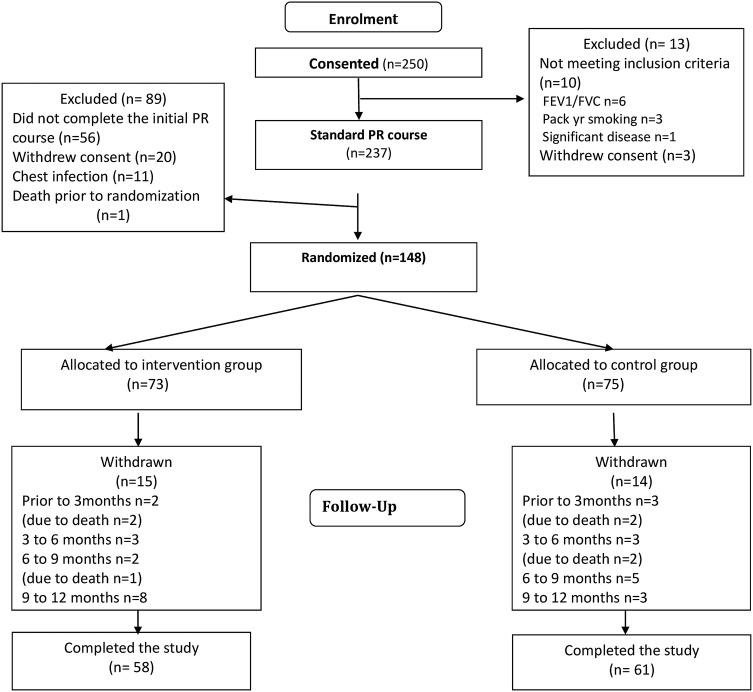

Two hundred and fifty (139 men; 111 women) patients provided informed consent to participate in the study. They had a mean (SD) age of 69.2 (9.2) years, FEV1 41 (16) % predicted, baseline CRQ dyspnoea score of 2.49 (0.99) units and baseline ESWT distance of 192.5 (132.1) metres. The majority (237 (94.8%) patients) started the standard PR programme (figure 1). There was a large withdrawal rate prior to randomisation mainly due to inability to complete the standard PR programme (56 (23.6%) patients) and 148 patients entered the randomised part of the study. These patients had a mean (95% CI) improvement in CRQ following the programme of 0.76 (0.59 to 0.93) units, which was statistically and clinically significant. There remained a significant improvement in CRQ dyspnoea at the end of maintenance period compared with the pre-PR session for the group as a whole. The intervention and control groups were well matched in terms of characteristics measured before and after the initial PR programme (table 1) although the control group walked further than the intervention group before and after initial PR in ESWT. Of the 73 patients randomised to the intervention, 38 (23 men; 15 women) patients (52%) completed all of the maintenance sessions. These patients had a baseline age: 70.1 (8.7) years, CRQ dyspnoea: 3.29 (1.1), ESWT duration 490.1 (400.0) seconds and ESWT distance (434.1 (378.7) metres.

Figure 1.

Disposition of patients. Although the majority (237 (94.8%) patients) started the standard pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) programme, there was a large withdrawal rate prior to randomisation mainly due to inability to complete the standard PR programme (56 (23.6%) patients). n=number of patients.

Table 1.

Summary of baseline characteristics for all individuals

| Control Pre PR |

Intervention Pre PR |

Control Post PR |

Intervention Post PR |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | |

| Age (years) | 75 | 69.3 (8.9) | 73 | 67.3 (15.1) | 75 | 73 | ||

| Male n (%) | 75 | 50.0 (66.7) | 73 | 41.0 (56.2) | 75 | 73 | ||

| CRQ dyspnoea | 74 | 2.5 (1.2) | 72 | 2.6 (1.0) | 74 | 3.3 (1.3) | 72 | 3.2 (1.1) |

| CRQ fatigue | 74 | 3.4 (1.1) | 72 | 3.2 (1.1) | 74 | 4.0 (1.1) | 72 | 3.9 (1.2) |

| CRQ emotion | 74 | 4.4 (1.3) | 72 | 4.2 (1.3) | 74 | 4.9 (1.1) | 72 | 5.2 (4.5) |

| CRQ mastery | 74 | 4.8 (1.2) | 72 | 4.2 (1.4) | 74 | 5.0 (1.5) | 72 | 4.6 (1.6) |

| ESWT (s) | 69 | 223.5 (94.4) | 67 | 184.4 (84.1) | 69 | 540.7 (411.9) | 67 | 520.9 (400.5) |

| ESWT (m) | 70 | 232.0 (150.0) | 65 | 174.8 (98.7) | 70 | 573.5 (451.6) | 65 | 452.9 (372.2) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 59 | 28.2 (6.0) | 53 | 28.8 (5.7) | 59 | 28.6 (6.3) | 53 | 28.7 (5.8) |

| Body fat (%) | 69 | 30.6 (7.1) | 62 | 31.8 (7.4) | 69 | 30.5 (6.7) | 62 | 31.7 (7.2) |

| HADS | 61 | 12.4 (6.9) | 57 | 13.5 (6.9) | 61 | 11.5 (6.9) | 57 | 11.9 (7.0) |

| EQ5D | 70 | 0.7 (0.2) | 67 | 0.6 (0.3) | 70 | 0.7 (0.3) | 67 | 0.6 (0.2) |

| Activity (MET-minutes) | 60 | 541.8 (460.3) | 49 | 550.1 (411.6) | 60 | 611.1 (543.7) | 49 | 611.7 (460.6) |

| Activity (VAS) | 57 | 35.4 (22.5) | 58 | 34.5 (16.3) | 57 | 45.5 (20.6) | 58 | 39.6 (21.5) |

CRQ, Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire; EQ5D, EuroQol; ESWT, endurance shuttle walk test; HADS, hospital anxiety and depression score; MET, metabolic equivalents; PR, pulmonary rehabilitation; VAS, visual analogue scale.

Outcome

No statistically significant differences were detected between the intervention and control groups for the CRQ dyspnoea score (0.19 (−0.26 to 0.64) units) or other domains of the CRQ, the ESWT distance between the two groups (109.1 (−100.1 to 318.2) metres), BMI, body fat EQ5D, MET-minutes, activity rating, HADS, exacerbations or admissions (table 2). There was a higher level of self-reported activity according to the visual analogue score but not the reported metabolic equivalent (MET)-minutes per week (although these findings were based on a small number of patients responding appropriately). There were no study related adverse events. Three patients died in the intervention group and four patients died in the standard care group (figure 1). The results of the per protocol (PP) analysis were in keeping with the intention to treat analysis except that there was a significantly greater MET-minutes per week in the intervention group, but more exacerbations and admissions. However, these data (for activity especially) are based on small numbers of patients and caution should be exercised when interpreting them. In addition, the PP control group consists of individuals who would have complied with the intervention as well as individuals who would not have complied, whereas the intervention group in the PP only contains individuals who have complied. This means that, unlike the situation with a pharmaceutical intervention, the difference between the two groups differ by their compliance behaviour as well as the intervention. However, they do suggest that there may be some harm associated with the intervention. There was no difference with any measurement for the analyses which include imputed data.

Table 2.

Change from post-PR values after 12 months, ITT and PP analysis with no imputation

| Control (n=75) | Intervention (n=73) | Mean difference |

Intervention (n=38) | Mean difference |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | N | Mean | 95% CI | p Value | N | Mean | 95% CI | p Value | |

| CRQ dyspnoea | 57 | −0.54 (1.21) | 53 | −0.35 (1.17) | 0.19 (−0.26 to 0.64) | 0.397 | 34 | −0.37 (1.30) | 0.17 (−0.36 to 0.71) | 0.522 |

| CRQ fatigue | 58 | −0.41 (1.19) | 53 | −0.30 (1.09) | 0.12 (−0.31 to 0.55) | 0.592 | 34 | −0.12 (1.06) | 0.3 (−0.19 to 0.79) | 0.233 |

| CRQ emotion | 58 | 0.02 (1.32) | 53 | 0.00 (1.46) | −0.02 (−0.55 to 0.5) | 0.927 | 34 | 0.31 (1.59) | 0.29 (−0.32 to 0.9) | 0.353 |

| CRQ mastery | 58 | −0.06 (1.49) | 53 | 0.01 (1.42) | 0.07 (−0.48 to 0.62) | 0.8 | 34 | 0.35 (1.51) | 0.41 (−0.23 to 1.05) | 0.205 |

| ESWT (m) | 40 | −179.29 (451.37) | 40 | −70.22 (487.59) | 109.08 (−100.08 to 318.23) | 0.302 | 28 | 6.91 (477.15) | 186.2 (−41.13 to 413.53) | 0.107 |

| ESWT (s) | 43 | −142.84 (398.91) | 40 | −152.90 (430.32) | −10.06 (−191.16 to 171.03) | 0.912 | 27 | −103.15 (408.95) | 39.69 (−157.66 to 237.04) | 0.689 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 40 | −0.33 (1.52) | 33 | −0.58 (2.71) | −0.25 (−1.26 to 0.75) | 0.617 | 23 | −0.85 (2.85) | −0.52 (−1.62 to 0.58) | 0.345 |

| Body fat (%) | 46 | −0.52 (3.64) | 41 | −0.60 (3.54) | −0.08 (−1.62 to 1.45) | 0.916 | 29 | −0.39 (3.16) | 0.12 (−1.52 to 1.76) | 0.882 |

| HADS | 44 | 0.89 (5.16) | 41 | 0.68 (5.04) | −0.2 (−2.41 to 2) | 0.855 | 28 | 0.11 (5.62) | −0.78 (−3.36 to 1.8) | 0.548 |

| EQ5D | 59 | −0.10 (0.28) | 55 | −0.08 (0.25) | 0.01 (−0.08 to 0.11) | 0.786 | 33 | −0.04 (0.22) | 0.06 (−0.05 to 0.17) | 0.277 |

| Activity (MET-minutes) | 17 | −88.82 (407.53) | 16 | 134.38 (518.16) | 223.2 (−106.68 to 553.08) | 0.177 | 10 | 307.50 (522.97) | 396.32 (24.92 to 767.72) | 0.037 |

| Activity (VAS) | 18 | −4.83 (14.25) | 17 | 11.35 (18.92) | 16.19 (4.71 to 27.66) | 0.007 | 10 | 12.11 (17.40) | 16.94 (4.06 to 29.83) | 0.012 |

| Exacerbation (event per year)* | 75 | 0.57 (1.05) | 73 | 0.56 (1.11) | 0.99 (0.73 to 1.33) | 0.931 | 38 | 0.84 (1.35) | 1.46 (1.06 to 2.01) | 0.021 |

| Hospitalisation (events per year)* | 75 | 0.28 (0.69) | 73 | 0.22 (0.53) | 0.77 (0.51 to 1.16) | 0.204 | 38 | 0.24 (0.59) | 0.82 (0.49 to 1.37) | 0.445 |

*These are the actual values rather than changes.

CRQ, Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire; EQ5D, EuroQol; ESWT, endurance shuttle walk test; HADS, hospital anxiety and depression score; MET, metabolic equivalents; R, pulmonary rehabilitation; VAS, visual analogue scale.

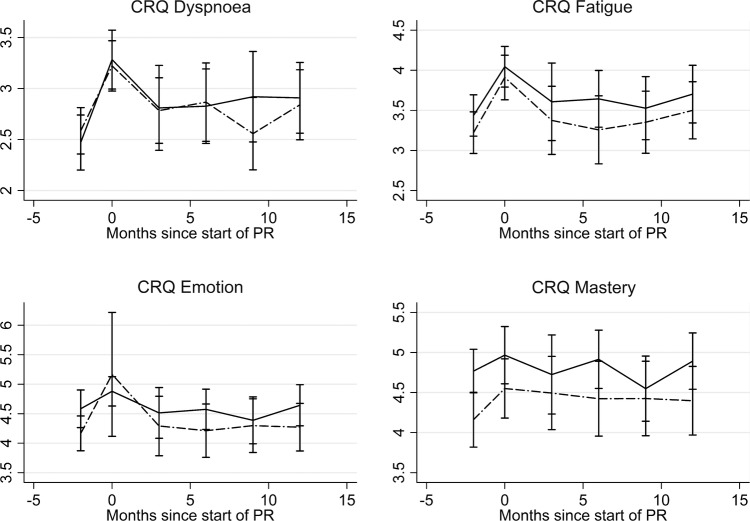

There was no difference in any of the CRQ measures at any of the 3-monthly measurements between the intervention and control groups (figure 2). Both groups had a significant deterioration in CRQ dyspnoea score 3 months following PR (control −0.45 (−0.68 to −0.23) units, intervention −0.38 (−0.70 to −0.06) units).

Figure 2.

Change in components of the Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire (CRQ) at 3−month intervals. There was no difference in any of the CRQ measures at any of three monthly measurements between the intervention and control groups. The control is the solid line and the intervention is dashed line. The bars represent the 95% CIs. PR, pulmonary rehabilitation.

Discussion

No significant between-group differences were found for changes at 12 months in HRQoL assessed by CRQ or EQ5D, exercise capacity assessed by ESWT, anxiety and/or depression, BMI or body fat (captured to ensure any potential change in BMI was not due to change in skeletal muscle bulk), although the magnitude of improvement in the ESWT distance (109 m) may have been clinically significant (difference of 70–82 m21). Our findings were not due to inadequacy of the initial PR programme as there was a statistically and clinically relevant improvement in the dyspnoea domain of the CRQ (primary outcome) with the initial PR and an overall sustained improvement compared to baseline in both groups. Although patients reported to be exercising more this did not translate into increased activity. However, the assessment of activity was captured using an unvalidated questionnaire and the post-PR values are likely to represent peak values given that this measurement reflects the period when patients were undergoing the initial PR programme. Our results suggest that maintenance programmes, delivered in the manner in this study, should not be used in order to achieve improvements in these outcomes.

Foglio et al22 evaluated the effect of repeating a PR course after 1 year compared to standard care and reported no significant difference in any of the outcome measures at 2 years except a lower frequency of exacerbations. In the intervention group, pre-PR values were back to baseline suggesting that a 12-month gap following initial PR is too long. This would be in keeping with data suggesting that by 6 months, patients are starting to lose the benefits of PR. By repeating the PR programme at 6 months, Romagnoli et al23 showed a reduction in the number of prolonged hospitalisations at 1 year, with improvements in symptoms and HRQoL, in a study of 35 patients. Ries et al24 randomised patients to attend a monthly maintenance schedule or standard care and demonstrated significant differences in exercise tolerance and health status at 1 year.

However, Brooks et al25 did not show any difference between patients undergoing a conventional maintenance PR (3-monthly follow-up) or enhanced maintenance PR (fortnightly phone calls and monthly supervised visits) after 1 year. The lack of effect may be due to the beneficial effect of the 3-monthly reviews as the rate of home exercise was the same in the two groups. Our study is in keeping with that of Brooks et al25 as we did not find any improvement in outcomes with 3-monthly revision supervised PR sessions. Despite our efforts to motivate the patients at these sessions we did not identify any significant increased daily activity. It is likely that the lack of sustained activity is related to the lack of improvement in exercise capacity and patient reported outcomes.

It is likely that our maintenance programme was not sufficiently frequent to sustain a benefit following initial PR. Several studies have evaluated the effect of maintenance PR programmes requiring frequent sessions. Indeed a recently published systematic review and meta-analysis reported improvement in medium-term outcomes with maintenance PR programmes, with significant improvements in exercise capacity, but not disease specific HRQOL as assessed by CRQ or St Georges Respiratory Questionnaire.8 All of the studies analysed within that meta-analysis, except the studies of Brooks et al25 and Ries et al24 (discussed above), evaluated maintenance programmes comprising supervised sessions of at least once per week. Given the costs associated with intensive sessions that are supervised by healthcare professionals, and the lack of effect of less intensive interventions, other methods of sustaining activity are required.

Several researchers have investigated less staff intensive methods of improving activity and quality of life in patients with COPD. In a small study of 21 patients, alternate day phone calls for 2 weeks increased activity, measured using accelerometers, exercise capacity and quality of life.26 However, this intervention involved frequent phone calls and the sustained effects are not known. Although a pilot study of an internet–based self-management programme for dyspnoea improved symptoms in patients with COPD,27 a larger study did not show improvements in dyspnoea compared with controls receiving general health education.28 However, this intervention was well received and did improve exercise behaviour and self-efficacy. In another study, patients with COPD were able to review their activity and receive educational and motivational material on a web-page, by wearing a pedometer which was linked to the internet.29 The patients increased their activity, were more informed about their potential level of achievement and stated they would recommend the programme to others. Other researchers have incorporated exercise training with a home exercise programme and goal setting within a patient directed self-management manual for COPD. The Self-Management Programme of Activity, Coping and Education for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (SPACE for COPD) programme, has been shown to improve exercise capacity and breathless in a pilot study30 and a larger study (presented at the European Respiratory Society Congress 2012) showed improvements in CRQ, ESWT distance and anxiety.

There was a considerable rate of drop-out in terms of patients withdrawing from the initial programme and also the maintenance programme. This is despite our encouragement for patients to continue to exercise and also a referral to the local patient support group (Breathe Easy Norwich) which is associated with the British Lung Foundation. In a qualitative review of focus groups comprising patients attending a maintenance programme, patients expressed more overall benefits than barriers to attending the programme. Attendance was improved by a feeling of improved quality of life but exacerbations, fatigue, transport and poor weather were barriers.31

This was a large adequately powered study with broad inclusion criteria and therefore we are confident that the results are robust and generalisable; however, there may have been some differences between the two groups at baseline. Although we ensured that the study investigator was blind, the patients could not be blind to the treatment allocation and did not have a sham intervention. By collecting activity questionnaires at 3-month intervals in both groups, we may have increased the activity in the control group; however, this does not seem likely from our data. Assessing activity levels using accelerometer or patient independent device would have provided more accurate data than that obtained from questionnaires. There was a relatively poor concordance rate with only half of patients attending all of the 3-monthly maintenance sessions. However, our results were similar when analysing the subgroup of patients complying with the intervention in the PP analysis suggesting that improved patient attendance would not have changed the findings of the study. Our initial PR comprised weekly visits rather than twice weekly visits as is usual in the UK;6 however, there are no data suggesting that twice weekly PR is superior to once weekly PR sessions. Indeed O'Neill et al9 have shown that these interventions result in similar long-term outcomes. Furthermore, our short-term benefits of PR were clinically significant and there remained a significant improvement in CRQ dyspnoea at the end of maintenance period compared with the pre-PR session for the group as a whole. It is unlikely that a twice weekly or longer initial PR programme will alter the conclusions of this study. We corrected for baseline values in order to account for any differences including the ESWT.

In conclusion, a maintenance programme of a 2 h session every 3 months does not improve outcomes in patients with COPD after 12 months. Despite our efforts to motivate the patients at these sessions we did not identify any significant increased daily activity. In addition, much of the beneficial effects of the initial PR were lost before the first maintenance session at 3 months. We do not recommend that our maintenance programme is adopted and suggest that other methods of sustaining the benefits of PR are required.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Claire Brockwell for her assistance with the randomisation of patients.

Footnotes

Contributors: AMW was the chief investigator. AMW, PB, SO, AC, PG, ED, ECFW, LS participated in the study concept and design. AMW, HW, SR were responsible for the data collection. AC undertook the statistical analysis. All authors participated in the data interpretation, writing and revision of the report and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Research for Patient Benefit (RfPB) Programme (Grant Reference Number PB-PG-0408-16225). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by Cambridgeshire 1 Research Ethics Committee and was registered on the clinicaltrials.gov database—identifier NCT00925171.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Centre. NCG. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in adults in primary and secondary care. London: National Clinical Guideline Centre, 2010. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG101/Guidance/pdf/English (accessed 26 Mar 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calverley PM, Walker P. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Lancet 2003;362:1053–61. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14416-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mannino DM, Buist AS. Global burden of COPD: risk factors, prevalence, and future trends. Lancet 2007;370:765–73. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61380-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh SJ, Smith DL, Hyland ME et al. A short outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation programme: immediate and longer-term effects on exercise performance and quality of life. Respir Med 1998;92:1146–54. 10.1016/S0954-6111(98)90410-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ries AL, Bauldoff GS, Carlin BW et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation: joint ACCP/AACVPR evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2007;131(5 Suppl):4S–42S. 10.1378/chest.06-2418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolton CE, Bevan-Smith EF, Blakey JD et al. ; British Thoracic Society Pulmonary Rehabilitation Guideline Development Group; British Thoracic Society Standards of Care Committee. British Thoracic Society guideline on pulmonary rehabilitation in adults. Thorax 2013;68(Suppl 2):ii1–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.British Lung Foundation. The Pulmonary Rehabilitation Survey, 2002. http://www.blf.org.uk/Page/Special-Reports (accessed 28 Apr 2014).

- 8.Beauchamp MK, Evans R, Janaudis-Ferreira T et al. Systematic review of supervised exercise programs after pulmonary rehabilitation in individuals with COPD. Chest 2013;144:1124–33. 10.1378/chest.12-2421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Neill B, McKevitt A, Rafferty S et al. A comparison of twice- versus once-weekly supervision during pulmonary rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007;88:167–72. 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norweg AM, Whiteson J, Malgady R et al. The effectiveness of different combinations of pulmonary rehabilitation program components: a randomized controlled trial. Chest 2005;128:663–72. 10.1378/chest.128.2.663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Puente-Maestu L, Sanz ML, Sanz P et al. Comparison of effects of supervised versus self-monitored training programmes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 2000;15:517–25. 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.15.15.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Puhan MA, Schunemann HJ, Frey M et al. How should COPD patients exercise during respiratory rehabilitation? Comparison of exercise modalities and intensities to treat skeletal muscle dysfunction. Thorax 2005;60:367–75. 10.1136/thx.2004.033274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnold E, Bruton A, Ellis-Hill C. Adherence to pulmonary rehabilitation: a qualitative study 1. Respir Med 2006;100:1716–23. 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh SJ, Morgan MD, Scott S et al. Development of a shuttle walking test of disability in patients with chronic airways obstruction. Thorax 1992;47:1019–24. 10.1136/thx.47.12.1019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Revill SM, Morgan MD, Singh SJ et al. The endurance shuttle walk: a new field test for the assessment of endurance capacity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 1999;54:213–22. 10.1136/thx.54.3.213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guyatt GH, Berman LB, Townsend M et al. A measure of quality of life for clinical trials in chronic lung disease. Thorax 1987;42:773–8. 10.1136/thx.42.10.773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. The EuroQol Group. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208. 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Redelmeier DA, Guyatt GH, Goldstein RS. Assessing the minimal important difference in symptoms: a comparison of two techniques. J Clin Epidemiol 1996;49:1215–19. 10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00206-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durnin JV, Womersley J. Body fat assessed from total body density and its estimation from skinfold thickness: measurements on 481 men and women aged from 16 to 72 years. Br J Nutr 1974;32:77–97. 10.1079/BJN19740060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borel B, Pepin V, Mahler DA et al. Prospective validation of the endurance shuttle walking test in the context of bronchodilation in COPD. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1166–76. 10.1183/09031936.00024314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foglio K, Bianchi L, Ambrosino N. Is it really useful to repeat outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation programs in patients with chronic airway obstruction? A 2-year controlled study. Chest 2001;119:1696–704. 10.1378/chest.119.6.1696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Romagnoli M, Dell'Orso D, Lorenzi C et al. Repeated pulmonary rehabilitation in severe and disabled COPD patients. Respiration 2006;73:769–76. 10.1159/000092953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ries AL, Kaplan RM, Myers R et al. Maintenance after pulmonary rehabilitation in chronic lung disease: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003;167:880–8. 10.1164/rccm.200204-318OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brooks D, Krip B, Mangovski-Alzamora S et al. The effect of postrehabilitation programmes among individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 2002;20:20–9. 10.1183/09031936.02.01852001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wewel AR, Gellermann I, Schwertfeger I et al. Intervention by phone calls raises domiciliary activity and exercise capacity in patients with severe COPD. Respir Med 2008;102:20–6. 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen HQ, Donesky-Cuenco D, Wolpin S et al. Randomized controlled trial of an internet-based versus face-to-face dyspnea self-management program for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: pilot study. J Med Internet Res 2008;10:e9 10.2196/jmir.990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nguyen HQ, Donesky D, Reinke LF et al. Internet-based dyspnea self-management support for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;46:43–55. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moy ML, Weston NA, Wilson EJ et al. A pilot study of an internet walking program and pedometer in COPD. Respir Med 2012;106:1342–50. 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Apps LD, Mitchell KE, Harrison SL et al. The development and pilot testing of the self-management programme of activity, coping and education for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (SPACE for COPD). Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2013;8:317–27. 10.2147/COPD.S40414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Desveaux L, Rolfe D, Beauchamp M et al. Participant experiences of a community-based maintenance program post-pulmonary rehabilitation. Chron Respir Dis 2014;11:23–30. 10.1177/1479972313516880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]