Abstract

Objective

To classify diseases based on age at peak incidence to identify risk factors for later disease in women's life course.

Design

A cross-sectional baseline survey of participants in the Japan Nurses’ Health Study.

Setting

A nationwide prospective cohort study on the health of Japanese nurses. The baseline survey was conducted between 2001 and 2007 (n=49 927).

Main outcome measures

Age at peak incidence for 20 diseases from a survey of Japanese women was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method with the Kernel smoothing technique. The incidence rate and peak incidence for diseases whose peak incidence occurred before the age of 45 years or before the perimenopausal period were selected as early-onset diseases. The OR and 95% CI were estimated to examine the risk of comorbidity between early-onset and other diseases.

Results

Four early-onset diseases (endometriosis, anaemia, migraine headache and uterine myoma) were significantly correlated with one another. Late-onset diseases significantly associated (OR>2) with early-onset diseases included comorbid endometriosis with ovarian cancer (3.65 (2.16 to 6.19)), endometrial cancer (2.40 (1.14 to 5.04)) and cerebral infarction (2.10 (1.15 to 3.85)); comorbid anaemia with gastric cancer (3.69 (2.68 to 5.08)); comorbid migraine with transient ischaemic attack (3.06 (2.29 to 4.09)), osteoporosis (2.11 (1.71 to 2.62)), cerebral infarction (2.04 (1.26 to 3.30)) and angina pectoris (2.00 (1.49 to 2.67)); and comorbid uterine myoma with colorectal cancer (2.31 (1.48 to 3.61)).

Conclusions

While there were significant associations between four early-onset diseases, women with a history of one or more of the early-onset diseases had a higher risk of other diseases later in their life course. Understanding the history of early-onset diseases in women may help reduce the subsequent risk of chronic diseases in later life.

Keywords: Comorbidity, women’s health, life-course approach, early-onset diseases

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study examined comprehensively the risks of comorbidity between early-onset gynaecological diseases and other subsequent chronic diseases in later life.

Age at peak incidence for 20 diseases from a large study population was estimated.

The study population, which was composed entirely of female nurses, is likely to report disease history more accurately than general population.

Data on disease histories were collected retrospectively, so only living participants were included in the study.

Women over the age of 60 years were under-represented relative to other age groups in the study.

Introduction

Women experience various diseases at different life stages that correspond to reproductive health-related events such as menarche and menopause.1 In particular, postmenarchal and premenopausal women may develop oestrogen-dependent diseases such as endometriosis and uterine myoma.2 While some diseases decline in frequency after menopause, others, such as hyperlipidaemia, occur more frequently, demonstrating that menopause represents a major transition event in a woman's life course.3–5

In women's health, it is important to understand how the history of gynaecological diseases that occur during premenopausal ages affects the risk of diseases that occur during perimenopausal or postmenopausal ages, from a life-course epidemiological point of view. A number of previous studies have highlighted the co-occurrence of gynaecological diseases with other disorders, such as the increased risk of ovarian cancer in women with endometriosis,6 the association between blood oestrogen levels and migraine in women,7 8 and the link between migraine and cardiovascular risk.9 However, few epidemiological studies have comprehensively examined the risks of comorbidity between early-onset gynaecological diseases and other subsequent chronic diseases in later life.

The Japan Nurses’ Health Study (JNHS) is a large-scale prospective cohort study investigating the effects of lifestyle, healthcare practices and history of diseases on women's health.10 In the cross-sectional baseline mail survey of the study, we investigated the prevalence of past diagnosis and age at first diagnosis for various diseases. The study population was designed for female registered nurses, public health nurses and midwives who were at least 25 years of age and resident in Japan at the baseline survey. Nurses were preferred as the study population because they were expected to accurately report medical information such as disease history. The objectives of this study were to classify diseases that occur frequently in women by identifying age at peak incidence and demonstrating their co-occurrence with other diseases based on the JNHS baseline data.

Methods

Survey participants

The study population comprised 49 927 female nurses who participated between 2001 and 2007 in the cross-sectional baseline survey of the JNHS, a nationwide prospective cohort study. The size of the study population was set to detect an increase of 1.5 or more in relative risk in the 10-year follow-up phase of the JNHS. The details of the study plan and the sample size calculation have been presented elsewhere.5 10 Data were obtained from a self-administered postal questionnaire covering a range of health topics including lifestyle habits, disease history, reproductive health and medication use.10 We included 48 632 women whose responses to the questions on disease histories were completed. Participants were informed of the study's purpose and procedures before recruitment.

Medical history questionnaire

Disease history was ascertained using a questionnaire. The baseline survey investigated participants’ medical histories and obtained information on previous diagnoses, age at first diagnosis and treatment histories for a range of major medical disorders.

Diseases analysed and definition of comorbidity

We excluded diseases from the analysis that had a prevalence based on the diagnosis history of less than 0.001. We analysed 20 diseases including hypertension, angina pectoris, subarachnoid haemorrhage, cerebral infarction, transient ischaemic attack (TIA), diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, hypercholesterolaemia, cholelithiasis, endometriosis, uterine myoma, cervical cancer, endometrial cancer, ovarian cancer, breast cancer, gastric cancer, colorectal cancer, osteoporosis, anaemia and migraine. Comorbidity was defined as the co-occurrence of two diseases based on a participant's disease history at baseline survey regardless of the timing of disease onset.

Statistical analysis

We estimated the cumulative incidence and 95% CI by the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (product-limit method). In the survival analyses, we treated incidence at the age of first diagnosis as an event in women with a history of the disease and the observation was censored at the age recorded in the baseline survey in women without a history of the disease.11 We estimated the age at peak incidence using the Kernel smoothing method (Epanechnikov Kernel) and defined early-onset diseases (diseases occurring frequently before the perimenopausal period) as those having a peak incidence at less than 45 years of age.12

To examine the risk of comorbidity between early-onset diseases and other diseases, ORs and 95% CIs were calculated. A statistical analysis was conducted to examine homogeneity by the Breslow-Day test and to estimate a common OR by the Mantel-Haenszel method between the two age groups (<50 years or ≥50 years). The crude ORs were also calculated as part of a sensitivity analysis. Statistical significance was set at the 5% level (two tailed) and no adjustments were made for multiplicity. All analyses were performed using SAS V.9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Subject characteristics

Of the 49 927 women who participated in the JNHS baseline survey, 48 632 who responded to the questions of disease histories were included in the analysis. The average age (SD) at the time of the baseline survey was 41.2 (7.9) years. The smoking prevalence in the study population was 17.2% (table 1). In addition, 22.7% of respondents reported consuming alcoholic beverages more than three times per week. Most women, 32 642 (67.1%), were married at the time of the baseline survey and 32 295 (66.4%) were parous. Only 6086 women (12.5%) were postmenopausal. The average reported age at menopause (SD) in the postmenopausal women was 49.1 (4.4) years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study population at baseline survey

| Characteristics | N | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | ||

| <30 | 938 | 1.9 |

| 30–34 | 11 174 | 23.0 |

| 35–39 | 10 163 | 20.9 |

| 40–44 | 9656 | 19.9 |

| 45–49 | 8155 | 16.8 |

| 50–54 | 5929 | 12.2 |

| 55–59 | 2217 | 4.6 |

| 60–64 | 339 | 0.7 |

| 65≤ | 61 | 0.1 |

| Smoking status | ||

| Non-smoker | 33 918 | 69.7 |

| Current smoker | 8388 | 17.2 |

| Ex-smoker | 5648 | 11.6 |

| Missing | 678 | 1.4 |

| Alcohol intake | ||

| Non-drinker | 14 224 | 29.2 |

| <3 day/week | 20 391 | 41.9 |

| ≥3 day/week | 11 024 | 22.7 |

| Missing | 2993 | 6.2 |

| Marital status | ||

| Unmarried | 11 633 | 23.9 |

| Married | 32 642 | 67.1 |

| Divorced | 2850 | 5.9 |

| Separated/widowed | 980 | 2.0 |

| Missing | 527 | 1.1 |

| Pregnancy | ||

| Never | 12 786 | 26.3 |

| Ever | 33 618 | 69.1 |

| Missing | 2228 | 4.6 |

| Delivery | ||

| Never | 14 328 | 29.5 |

| Ever | 32 295 | 66.4 |

| Missing | 2009 | 4.1 |

| Menopause status | ||

| Premenopause | 40 010 | 82.3 |

| Postmenopause | 6086 | 12.5 |

| Unknown | 1947 | 4.0 |

| Missing | 589 | 1.2 |

Incidence of past diagnosis by disease

The cumulative incidences estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method at 30, 40, 50 and 60 years of age are shown in table 2. The high cumulative incidence at 50 years of age, around the mean age at menopause, was 29.0% for anaemia, 18.9% for uterine myoma, 13.0% for hypercholesterolaemia, 10.7% for migraine headache, 9.0% for hypertension, 7.4% for endometriosis and 6.0% for thyroid disease.

Table 2.

Incidence peak and cumulative incidence for the K-M estimate

| Incidence peak* (%) |

Age at incidence peak (years) |

Cumulative incidence (%) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 years |

40 years |

50 years |

60 years |

|||||||

| K-M estimate | 95% CI | K-M estimate | 95% CI | K-M estimate | 95% CI | K-M estimate | 95% CI | |||

| Endometriosis | 0.25 | 36.0 | 2.19 | 2.07 to 2.33 | 4.91 | 4.70 to 5.12 | 7.36 | 7.06 to 7.67 | 7.76 | 7.41 to 8.12 |

| Anaemia | 0.85 | 36.0 | 12.4 | 12.1 to 12.7 | 19.2 | 18.8 to 19.5 | 29.0 | 28.5 to 29.6 | 31.8 | 31.1 to 32.6 |

| Migraine headache | 0.32 | 44.8 | 4.51 | 4.32 to 4.70 | 7.68 | 7.43 to 7.93 | 10.7 | 10.3 to 11.1 | 12.8 | 12.2 to 13.5 |

| Uterine myoma | 1.11 | 44.8 | 1.22 | 1.12 to 1.32 | 6.81 | 6.56 to 7.07 | 18.9 | 18.3 to 19.4 | 22.9 | 22.1 to 23.7 |

| Cervical cancer | 0.04 | 44.8 | 0.09 | 0.06 to 0.12 | 0.57 | 0.50 to 0.65 | 1.11 | 0.98 to 1.25 | 1.37 | 1.13 to 1.65 |

| Thyroid disease | 0.26 | 49.2 | 1.60 | 1.49 to 1.71 | 3.41 | 3.24 to 3.59 | 6.00 | 5.71 to 6.31 | 9.39 | 8.64 to 10.2 |

| Breast cancer | 0.10 | 50.0 | 0.04 | 0.03 to 0.06 | 0.33 | 0.27 to 0.39 | 1.50 | 1.33 to 1.70 | 2.72 | 2.20 to 3.37 |

| Cholelithiasis | 0.23 | 52.2 | 0.44 | 0.38 to 0.50 | 1.42 | 1.30 to 1.54 | 3.26 | 3.03 to 3.50 | 6.15 | 5.42 to 6.96 |

| Subarachnoid haemorrhage | 0.03 | 55.1 | 0.01 | 0.01 to 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.03 to 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.12 to 0.24 | 0.44 | 0.27 to 0.74 |

| Transient ischaemic attack | 0.07 | 55.1 | 0.14 | 0.11 to 0.18 | 0.29 | 0.24 to 0.35 | 0.66 | 0.56 to 0.77 | 1.50 | 1.10 to 2.04 |

| Endometrial cancer | 0.02 | 55.9 | 0.00 | 0.00 to 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.03 to 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.11 to 0.24 | 0.51 | 0.32 to 0.81 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.38 | 57.3 | 0.08 | 0.06 to 0.11 | 0.41 | 0.35 to 0.49 | 1.92 | 1.73 to 2.14 | 6.49 | 5.57 to 7.55 |

| Gastric cancer | 0.05 | 57.3 | 0.03 | 0.02 to 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.12 to 0.21 | 0.52 | 0.42 to 0.63 | 0.98 | 0.67 to 1.43 |

| Cerebral infarction | 0.11 | 58.8 | 0.02 | 0.01 to 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.04 to 0.10 | 0.28 | 0.21 to 0.37 | 1.36 | 0.95 to 1.94 |

| Ovarian cancer | 0.06 | 63.9 | 0.06 | 0.04 to 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.10 to 0.17 | 0.28 | 0.21 to 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.25 to 0.57 |

| Colorectal cancer | 0.14† | ≥65‡ | 0.01 | 0.00 to 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 to 0.07 | 0.34 | 0.26 to 0.45 | 0.97 | 0.70 to 1.34 |

| Angina pectoris | 0.56† | ≥65‡ | 0.04 | 0.03 to 0.06 | 0.20 | 0.16 to 0.25 | 0.99 | 0.85 to 1.15 | 3.03 | 2.46 to 3.74 |

| Osteoporosis | 2.23† | ≥65‡ | 0.07 | 0.05 to 0.09 | 0.26 | 0.21 to 0.32 | 1.18 | 1.03 to 1.35 | 6.73 | 5.73 to 7.89 |

| Hypertension | 3.86† | ≥65‡ | 0.36 | 0.31 to 0.42 | 1.74 | 1.61 to 1.88 | 9.05 | 8.62 to 9.49 | 23.4 | 21.9 to 25.0 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 4.74† | ≥65‡ | 0.94 | 0.86 to 1.03 | 3.27 | 3.10 to 3.45 | 13.0 | 12.5 to 13.5 | 41.3 | 39.4 to 43.2 |

*Incidence peak was estimated by the Kernel smoothing technique.

†Incidence at 65 years of age.

‡Age at incidence peak was undetermined because age-specific incidence was hockey stick shaped until age 65 years.

K-M, Kaplan-Meier.

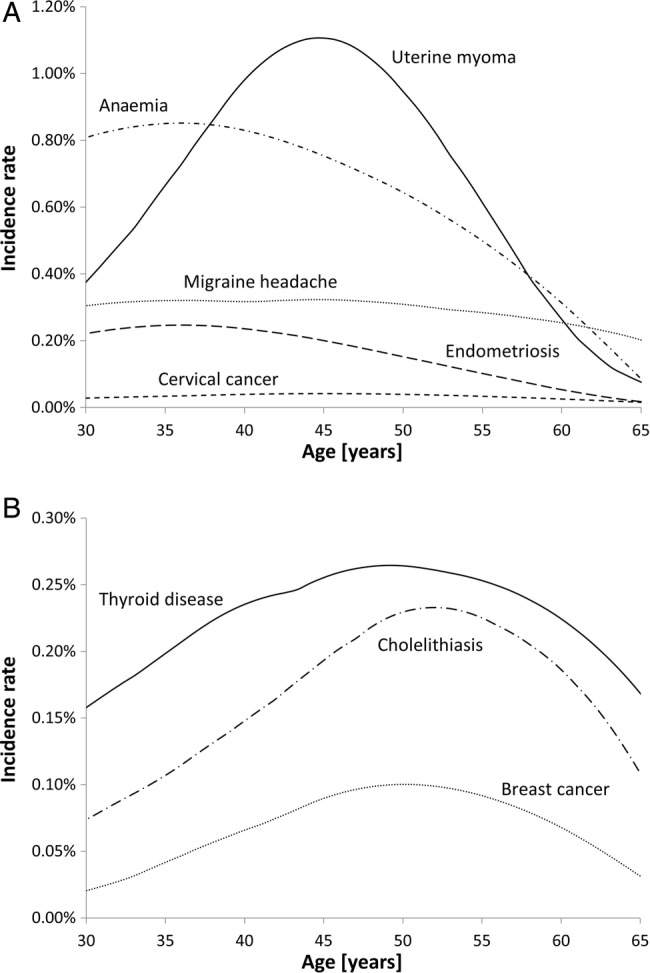

On the basis of the age at peak incidence of disease estimated by Kernel smoothing, the early-onset diseases that had a peak of incidence before 45 years of age (before the perimenopausal period) were endometriosis (36 years), anaemia (36 years), migraine headache (44.8 years), uterine myoma (44.8 years) and cervical cancer (44.8 years). Figure 1A shows the Kernel smoothing estimates of incidence for these early-onset diseases. The peak incidence of thyroid disease, breast cancer and cholelithiasis occurred between 45 and 54 years of age, or in the perimenopausal period (figure 1B). For the other 12 diseases (subarachnoid haemorrhage, TIA, endometrial cancer, diabetes mellitus, gastric cancer, cerebral infarction, ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer, angina pectoris, osteoporosis, hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia), the peak incidence occurred after 55 years of age, or in the postmenopausal period (table 2).

Figure 1.

(A) Kernel smoothing estimates of incidence for early-onset diseases with a peak incidence before 45 years of age. (B) Kernel smoothing estimates of incidence for diseases with a peak incidence between 45 and 54 years of age.

Comorbidity among early-onset diseases

The early-onset diseases were endometriosis, anaemia, migraine, uterine myoma and cervical cancer. Four early-onset diseases (endometriosis, anaemia, migraine headache and uterine myoma) were significantly correlated with one another (table 3). It is worth noting that the OR (95% CI) for comorbid endometriosis and uterine myoma was 4.47 (4.09 to 4.87).

Table 3.

MH common ORs (95% CI) for comorbidities

| Endometriosis |

Anaemia |

Migraine |

Uterine myoma |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MH OR |

95% CI | p Value for the Breslow-Day test | MH OR |

95% CI | p Value for the Breslow-Day test | MH OR |

95% CI | p Value for the Breslow-Day test | MH OR |

95% CI | p Value for the Breslow-Day test | |

| Endometriosis | 2.31 | (2.14 to 2.50) | 0.225 | 1.96 | (1.77 to 2.17) | 0.652 | 4.47 | (4.09 to 4.87) | 0.449 | |||

| Anaemia | 2.31 | (2.14 to 2.50) | 0.225 | 2.13 | (2.01 to 2.27) | 0.045 | 2.73 | (2.57 to 2.90) | 0.410 | |||

| Migraine headache | 1.96 | (1.77 to 2.17) | 0.652 | 2.13 | (2.01 to 2.27) | 0.045 | 1.30 | (1.20 to 1.42) | 0.246 | |||

| Uterine myoma | 4.47 | (4.09 to 4.87) | 0.449 | 2.73 | (2.57 to 2.90) | 0.410 | 1.30 | (1.20 to 1.42) | 0.246 | |||

| Cervical cancer | 1.12 | (0.74 to 1.69) | 0.969 | 0.82 | (0.64 to 1.06) | 0.093 | 1.32 | (0.98 to 1.78) | 0.203 | 1.39 | (1.04 to 1.85) | 0.412 |

| Thyroid disease | 1.49 | (1.27 to 1.75) | 0.595 | 1.18 | (1.07 to 1.31) | 0.306 | 1.24 | (1.09 to 1.41) | 0.073 | 1.43 | (1.27 to 1.61) | 0.010 |

| Breast cancer | 1.34 | (0.91 to 1.96) | 0.272 | 0.76 | (0.59 to 0.98) | 0.212 | 0.82 | (0.58 to 1.17) | 0.061 | 1.54 | (1.19 to 1.99) | 0.119 |

| Cholelithiasis | 1.31 | (1.04 to 1.65) | 0.905 | 1.19 | (1.04 to 1.36) | 0.348 | 1.42 | (1.20 to 1.69) | 0.135 | 1.68 | (1.44 to 1.95) | 0.015 |

| Subarachnoid haemorrhage | 1.00 | (0.31 to 3.22) | 0.480 | 0.67 | (0.32 to 1.38) | 0.385 | 1.50 | (0.70 to 3.21) | 0.663 | 0.92 | (0.41 to 2.05) | 0.409 |

| Transient ischaemic attack | 1.91 | (1.26 to 2.90) | 0.748 | 1.44 | (1.09 to 1.90) | 0.899 | 3.06 | (2.29 to 4.09) | 0.384 | 1.38 | (0.99 to 1.94) | 0.529 |

| Endometrial cancer | 2.40 | (1.14 to 5.04) | 0.632 | 1.20 | (0.68 to 2.09) | 0.110 | 1.97 | (1.05 to 3.70) | 0.634 | 0.78 | (0.35 to 1.74) | 0.678 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.09 | (0.79 to 1.51) | 0.128 | 0.68 | (0.56 to 0.84) | 0.028 | 0.99 | (0.77 to 1.28) | 0.451 | 1.45 | (1.19 to 1.77) | <0.001 |

| Gastric cancer | 0.87 | (0.43 to 1.78) | 0.946 | 3.69 | (2.68 to 5.08) | 0.879 | 1.06 | (0.65 to 1.74) | 0.252 | 1.04 | (0.66 to 1.63) | 0.539 |

| Cerebral infarction | 2.10 | (1.15 to 3.85) | 0.447 | 0.89 | (0.56 to 1.42) | 0.987 | 2.04 | (1.26 to 3.30) | 0.581 | 1.39 | (0.85 to 2.25) | 0.120 |

| Ovarian cancer | 3.65 | (2.16 to 6.19) | 0.208 | 0.94 | (0.58 to 1.53) | 0.995 | 1.51 | (0.85 to 2.66) | 0.291 | 1.60 | (0.93 to 2.76) | 0.539 |

| Colorectal cancer | 1.59 | (0.80 to 3.16) | 0.594 | 1.56 | (1.02 to 2.37) | 0.506 | 1.78 | (1.06 to 2.97) | 0.618 | 2.31 | (1.48 to 3.61) | 0.384 |

| Angina pectoris | 1.55 | (1.03 to 2.32) | 0.093 | 1.12 | (0.86 to 1.45) | 0.170 | 2.00 | (1.49 to 2.67) | 0.283 | 1.45 | (1.09 to 1.91) | <0.001 |

| Osteoporosis | 1.89 | (1.43 to 2.51) | 0.532 | 1.49 | (1.24 to 1.80) | 0.010 | 2.11 | (1.71 to 2.62) | 0.622 | 1.54 | (1.24 to 1.90) | 0.441 |

| Hypertension | 1.26 | (1.07 to 1.47) | 0.003 | 0.98 | (0.90 to 1.08) | 0.035 | 1.69 | (1.52 to 1.90) | 0.455 | 1.50 | (1.35 to 1.66) | <0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 1.30 | (1.15 to 1.47) | 0.021 | 1.06 | (0.98 to 1.14) | <0.001 | 1.35 | (1.23 to 1.48) | 0.237 | 1.36 | (1.25 to 1.48) | <0.001 |

MH, Mantel-Haenszel.

Comorbidity of four early-onset diseases and other diseases

The study population was stratified by age at survey into two strata, less than 50 years and 50 years of age or older. Examination for homogeneity of ORs across strata using the Breslow-Day test revealed that the risk of comorbidity was statistically heterogeneous for hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia in women with endometriosis, diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia in women with anaemia, thyroid disease, diabetes mellitus, angina pectoris, hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia in women with uterine myoma (table 3). In all of those comorbidities, the OR in the older age stratum was lower than in the younger age stratum. The strength of the association was diminished in the older stratum. The only statistically negative association of anaemia and diabetes mellitus was also heterogeneous between age strata (Breslow-Day test: p=0.028), indicating that the negative association was stronger in the older stratum, with the OR changing from 0.86 in <50 years to 0.54 in the ≥50 years of age stratum.

The common ORs (95% CI) greater than 2.00 for comorbid endometriosis were 3.65 (2.16 to 6.19), 2.40 (1.14 to 5.04) and 2.10 (1.15 to 3.85) for ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer and cerebral infarction, respectively. The common OR greater than 2.00 for comorbid anaemia was 3.69 (2.68 to 5.08) for gastric cancer. The common OR for comorbid anaemia and diabetes mellitus was significantly lower, 0.68 (0.56 to 0.84). The common ORs greater than 2.00 for comorbid migraine headache were 3.06 (2.29 to 4.09), 2.11 (1.71 to 2.62), 2.04 (1.26 to 3.30) and 2.00 (1.49 to 2.67) for TIA, osteoporosis, cerebral infarction and angina pectoris, respectively. The common OR greater than 2.00 for comorbid uterine myoma was 2.31 (1.48 to 3.61) for colorectal cancer only (table 3). The crude ORs without stratification were used in a sensitivity analysis. Similar estimates were obtained (data not shown).

Discussion

The age at peak incidence of diseases in Japanese women varies in the premenopausal, perimenopausal and postmenopausal periods. The early-onset diseases (those with a peak incidence before 45 years of age) were endometriosis, anaemia, migraine headache, uterine myoma and cervical cancer. The associations found in this comprehensive study between early-onset diseases and other diseases suggest that women with a history of early-onset diseases have a higher risk of other diseases later in their life course. Understanding the history of early-onset diseases in women may help reduce any subsequent risk of chronic diseases in later life.

In this study, we observed a skewed age distribution because of the smaller sample size of participants aged 50 years or older. We stratified the study population by age at the time of the survey into two strata (<50 years and ≥50 years of age) and examined the homogeneity of ORs between the age groups. In addition, we estimated the common ORs between the two age groups instead of overall crude ORs to adjust for the skewed age distribution. However, statistical significance in the comorbidity of very late-onset diseases such as osteoporosis was unlikely because of the small sample size in the older age group.

For endometriosis, the estimated age at peak incidence was 36 years of age and the cumulative incidence at 50 years of age was 7.4%; thus, endometriosis could be considered a common gynaecological disorder in relatively young women. Endometriosis is characterised by excessive growth of extrauterine endometrial tissue, resulting in subsequent bleeding into the abdominal cavity and ovaries, and presenting with symptoms such as peritonitis and painful defaecation or urination. While levels of high-sensitivity C reactive protein (CRP), a marker of inflammation, have been found to be significantly higher in women with endometriosis,13 other studies have reported an association between elevated blood levels of high-sensitivity CRP and ischaemic stroke.14 15 Inflammation resulting from endometriosis may therefore also be linked with an increased risk of ischaemic stroke. Our results suggest that endometriosis may increase the risk of cerebral infarction and TIA by triggering inflammation. The OR (95% CI) for comorbid endometriosis and ovarian cancer was 3.65 (2.16 to 6.19), which supports the conclusions of a previous study that found that endometriosis increases the risk of developing ovarian cancer.6

Anaemia was found to have a higher cumulative incidence (29.0% at 50 years of age). Anaemia is highly prevalent among women and may be diagnosed following pregnancy or heavy menstrual bleeding caused by uterine myoma. In the present study, the peak incidence for anaemia occurred at 36 years of age. Our results imply that relatively young, premenopausal women are more susceptible to anaemia than older, postmenopausal women. Our results also suggest a strong association between anaemia and gastric cancer. While anaemia can occur because of gastrectomy,16 pernicious anaemia is associated with increased risk of gastric cancer.17–19 The causal pathway, including a reverse effect, could not be determined because of the study's cross-sectional design. This study had a novel finding in that there was a significant negative association between anaemia and diabetes mellitus. Several studies have reported that body iron stores or elevated ferritin concentrations were associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus,20 21 potentially supporting our finding of the negative association between anaemia and diabetes mellitus.

The age at incidence peak of migraine headache was 44.8 years. Several studies reported that migraine was associated with oestrogen levels,7 8 and the incidence significantly increased from menarche onwards.22 23 Migraine also increased the risk of ischaemic stroke and cardiovascular disease in another study.9 This study's findings of a significantly enhanced risk of TIA, cerebral infarction and angina pectoris in migraine sufferers appear to support this.

The cumulative incidence at 50 years of age of uterine myoma was 18.9%. Although uterine myoma is often asymptomatic, we diagnosed a number of participants with the condition after they underwent cancer screening or a prenatal test. Uterine myoma is associated with elevated body mass index24 and body fat percentage,25 suggesting that uterine myoma may be associated with obesity. Obesity is also associated with increased risk of colon cancer.26 27 The OR of comorbid colorectal cancer was 2.31 (1.48 to 3.61) in this study, suggesting that obesity is a potential common risk factor for uterine myoma and colorectal cancer.

The estimated age at peak incidence of early-onset diseases, as well as other diseases in this study, revealed the nature of diseases in a woman's life course. The diseases included hypercholesterolaemia, hypertension and osteoporosis, which occur more frequently among postmenopausal women over 60 years of age. The cumulative incidences at 60 years of age for hypercholesterolaemia, hypertension and osteoporosis were 41.3%, 23.4% and 6.7%, respectively, and these diseases exhibited a marked increase in incidence after the perimenopausal period.

The peak incidence for breast cancer occurred at 50 years (figure 1B), indicating that Japanese women are more likely to develop the disease before menopause rather than after the perimenopausal period. Our results suggest that, unlike women in Western countries where the incidence of breast cancer increases with age even after menopause,28 the incidence among women in Japan and other Asian settings exhibits a bell-shaped pattern with a peak at 45–50 years.29 Our findings therefore support the current consensus that the incidence of breast cancer in Japan is higher before menopause than after.

This study has several limitations. In this study, we defined disease onset as a diagnosis by a medical doctor that was reported on the self-administered questionnaire. Participants could only report a diagnosis; asymptomatic or undiagnosed diseases were excluded. Use of diagnoses rather than self-reported prevalence may affect correlation in some diseases. Information on disease diagnosis was based on self-reporting, which may have led to a misclassification of diagnoses. However, nurses are likely to report such information more accurately than the general population because of their medical knowledge and clinical experience. In addition, our study population, which was composed entirely of nurses, was likely to exhibit different health behaviours and be exposed to different risk factors compared with the general Japanese population. Thus, our findings may not be generalisable to the national population, reducing this study's external validity. However, we have no reason to suspect that the general population of women would differ in terms of risk of comorbidity between early-onset and other diseases later in the life course. Additionally, data on disease histories were collected retrospectively, so only living participants were included in the survey. This may have led to an underestimation of disease incidence. Furthermore, we were unable to determine the causal relationship between comorbidities because of the cross-sectional design. Recall bias may have caused an overestimation of ORs since sick people tend to report more about disease history. However, since the participants were nurses, we think that recall bias was minimised since they have medical knowledge and are more likely to have answered correctly. A further analysis of the JNHS cohort using follow-up data is needed to determine the causal relationships between these comorbidities. Finally, women over the age of 60 years were under-represented relative to other age groups in the study.

Conclusions

While there were significant associations between the four early-onset diseases (endometriosis, anaemia, migraine headache and uterine myoma), women with a history of early-onset diseases had a higher risk of other diseases later in the life course. Understanding the history of early-onset diseases in women may help reduce the subsequent risk of chronic diseases in later life. Further research based on follow-up studies is needed to clarify the cause–effect associations between these diseases.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the assistance of Mr Toshio Kobayashi and Dr Fumie Tokuda in data entry and management. They also appreciate the late Professor Toshiharu Fujita's contributions to the Japan Nurses’ Health Study. This manuscript was checked by a native-English-speaking science editor.

Footnotes

Contributors: KN analysed the data and drafted the report. KH designed and initiated the study. KN, KH, TY and KK contributed to the interpretation and discussion of the data and writing of the manuscript. KN, KH, TY, KK, HI, YK, AW, TK and HM approved the final draft to be published and agreed to account for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This study was supported partly by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B: 22390128 to KH) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Gunma University and the National Institute of Public Health.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Mishra GD, Anderson D, Schoenaker DA et al. . InterLACE: a new international collaboration for a life course approach to women's reproductive health and chronic disease events. Maturitas 2013;74:235–40. 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D et al. . Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol 2004;160:784–96. 10.1093/aje/kwh275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yasui T, Matsui S, Tani A et al. . Androgen in postmenopausal women. J Med Invest 2012;59:12–27. 10.2152/jmi.59.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee JS, Hayashi K, Mishra G et al. . Independent association between age at natural menopause and hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus: Japan nurses’ health study. J Atheroscler Thromb 2013;20:161–9. 10.5551/jat.14746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujita T, Hayashi K, Katanoda K et al. . Prevalence of diseases and statistical power of the Japan Nurses’ Health Study. Ind Health 2007;45:687–94. 10.2486/indhealth.45.687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aris A. Endometriosis–associated ovarian cancer: a ten–year cohort study of women living in the Estrie Region of Quebec, Canada. J Ovarian Res 2010;3:2 10.1186/1757-2215-3-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacGregor EA. Oestrogen and attacks of migraine with and without aura. Lancet Neurol 2004;3:354–61. 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00768-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brandes JL. The influence of estrogen on migraine: a systematic review. JAMA 2006;295:1824–30. 10.1001/jama.295.15.1824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bigal ME, Kurth T, Santanello N et al. . Migraine and cardiovascular disease: a population-based study. Neurology 2010;74:628–35. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d0cc8b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayashi K, Mizunuma H, Fujita T et al. . Design of the Japan Nurses’ Health Study: a prospective occupational cohort study of women's health in Japan. Ind Health 2007;45:679–86. 10.2486/indhealth.45.679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, May S. Applied survival analysis: regression modeling of time-to-event data. 2nd edn. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2008:16–66. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allison PD. Survival analysis using SAS: a practical guide. 2nd edn. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc., 2010:29–70. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kinugasa S, Shinohara K, Wakatsuki A. Increased asymmetric dimethylarginine and enhanced inflammation are associated with impaired vascular reactivity in women with endometriosis. Atherosclerosis 2011;219:784–8. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makita S, Nakamura M, Satoh K et al. . Serum C-reactive protein levels can be used to predict future ischemic stroke and mortality in Japanese men from the general population. Atherosclerosis 2009;204:234–8. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.07.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chei CL, Yamagishi K, Kitamura A et al. . C-reactive protein levels and risk of stroke and its subtype in Japanese: the Circulatory Risk in Communities Study (CIRCS). Atherosclerosis 2011;217:187–93. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim CH, Kim SW, Kim WC et al. . Anemia after gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: long-term follow-up observational study. World J Gastroenterol 2012;18:6114–19. 10.3748/wjg.v18.i42.6114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mellemkjaer L, Gridley G, Møller H et al. . Pernicious anaemia and cancer risk in Denmark. Br J Cancer 1996;73:998–1000. 10.1038/bjc.1996.195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ye W, Nyrén O. Risk of cancers of the oesophagus and stomach by histology or subsite in patients hospitalised for pernicious anaemia. Gut 2003;52:938–41. 10.1136/gut.52.7.938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vannella L, Lahner E, Osborn J et al. . Systematic review: gastric cancer incidence in pernicious anaemia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;37:375–82. 10.1111/apt.12177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang R, Mason JE, Meigs JB et al. . Body iron stores in relation to risk of type 2 diabetes in apparently healthy women. JAMA 2004;291:711–17. 10.1001/jama.291.6.711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun L, Franco OH, Hu FB et al. . Ferritin concentrations, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes in middle-aged and elderly Chinese. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:4690–6. 10.1210/jc.2008-1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S et al. . Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache 2001;41:646–57. 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2001.041007646.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Celentano DD et al. . Prevalence of migraine headache in the United States. Relation to age, income, race, and other sociodemographic factors. JAMA 1992;267:64–9. 10.1001/jama.1992.03480010072027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takeda T, Sakata M, Isobe A et al. . Relationship between metabolic syndrome and uterine leiomyomas: a case-control study. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2008;66:14–17. 10.1159/000114250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sato F, Nishi M, Kudo R et al. . Body fat distribution and uterine leiomyomas. J Epidemiol 1998;8:176–80. 10.2188/jea.8.176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harriss DJ, Atkinson G, George K et al. , C-CLEAR group. Lifestyle factors and colorectal cancer risk (1): systematic review and meta-analysis of associations with body mass index. Colorectal Dis 2009;11:547–63. 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01766.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larsson SC, Wolk A. Obesity and colon and rectal cancer risk: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;86:556–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsuno RK, Anderson WF, Yamamoto S et al. . Early- and late-onset breast cancer types among women in the United States and Japan. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2007;16:1437–42. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toi M, Ohashi Y, Seow A et al. . The Breast Cancer Working Group presentation was divided into three sections: the epidemiology, pathology and treatment of breast cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2010;40(Suppl 1):i13–18. 10.1093/jjco/hyq122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]