Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the learning curves of three high-volume procedures, from distinct surgical specialties.

Setting

Tertiary care academic hospital.

Participants

A prospectively collected database comprising all medical records of patients undergoing isolated coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), total knee replacement (TKR) and bilateral reduction mammoplasty (BRM) at the Brigham and Women's Hospital, USA, 1996–2010. Multivariate generalised estimating equation (GEE) regression models were used to adjust for patient risk and clustering of procedures by surgeon.

Primary outcome measure

Operative efficiency.

Results

A total of 1052 BRMs, 3254 CABGs and 3325 TKRs performed by 30 surgeons were analysed. Median number of procedures per surgeon was 61 (range 11–502), 290 (52–973) and 99 (10–1871) for BRM, CABG and TKR, respectively. Mean operative times were 134.4 (SD 34.5), 180.9 (62.3) and 101.9 (30.3) minutes, respectively. For each procedure, attending surgeon experience was associated with significant reductions in operative time (p<0.05). After 15 years of experience, BRM operative time decreased by 69.8 min (38.3%), CABG operative time decreased by 17.5 min (7.8%) and TKR operative time decreased by 94.4 min (48.4%).

Conclusions

Common trends in surgical learning exist. Dependent on the procedure, experience can serve as a powerful driver of improvement or have clinically insignificant impacts on operative time.

Keywords: SURGERY, PUBLIC HEALTH, MEDICAL EDUCATION & TRAINING

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Use of high-granularity data on over 7000 procedures, performed by 30 surgeons.

Robust statistical demonstration of the effect of experience on operative efficiency.

Single centre, retrospective and focused on operative time, which although having clear relevance to operative efficiency and financial costs, is not a clear patient-centred outcome.

Introduction

Performance measurement and the application of quality, efficiency and safety metrics in surgery has dramatically expanded over the past two decades. This has met with variable degrees of compliance and success. The operating room (OR) represents a high-risk environment, requiring the coordination of technology, competence and resources under time pressure by the operating team.1 2 When combined with the technical and dexterous nature of surgery, it is apparent that several factors must be considered and accounted for to make accurate, equitable and comparable measurements of performance between surgeons. One of these factors is the learning curve inherent to operative procedures.3–8

Until recently, studies have lacked adequate data volume and resolution to gain an appropriate understanding of procedural dynamics, or to robustly identify suitable performance metrics. Work thus far has predominantly focused on surgery at the institutional or departmental level, rather than that of the individual surgeon. Furthermore, no studies to date have compared learning curves across different surgical specialties using statistically uniform methods.8

We performed a cross-specialty, comparative study evaluating the learning curves of three high-volume and well-defined procedures: bilateral reduction mammoplasty (BRM), isolated coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and total knee replacement (TKR). Our intent was to define commonalities and discrepancies in the learning curves of these procedures, and thereby identify overarching themes that may inform future surgical performance improvement efforts.

Methods

Design and population

Data for all CABG, TKR and BRM procedures performed at Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH), 2001–2010, 1996–2009 and 1995–2007, respectively, were culled from a combination of electronic medical records, an electronic operative time tracking application and physician employee databases. The data sets were filtered to exclude CABGs that were accompanied by concomitant procedures (eg, valve surgery, MAZE, etc); erroneously coded procedures including partial knee replacements, combined procedures and bilateral TKR procedures; gynaecomastia, resections and partial/total mastectomies; and incomplete or incorrect data entries (details of the exclusion process are included in the online supplementary appendix). Data sets were subsequently filtered to only include surgeons who conducted more than 10 procedures annually, focusing on the first 20 years of the learning curve.

For CABG, the primary dependent variable was operative time defined as the sum of cardiopulmonary bypass time (CPB) and cross clamp time. For TKR and BRM, operative time was defined as the time elapsed from skin incision to skin closure. The operative experience of the attending surgeon was calculated as the difference between the date of the procedure and that of the surgeon's completion of training. This study was performed under Institutional Review Board approval (protocol 2006p000586).

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of patients and surgeons were described using absolute frequencies with percentages for categorical variables. The mean values with SDs and median values with minimum–maximum intervals were calculated for continuous variables.

The expected learning curve of surgeons over time was generated based on a multivariate generalised estimating equations (GEE) regression model. A number of possible shapes of learning curves were tested in order to obtain the best fitting.9 Outcomes were adjusted for clustering of patients by surgeon, as well as patient case-mix factors (for CABG: patient age, sex, preoperative cardiogenic shock, diabetes mellitus and preoperative congestive heart failure; for TKR: patient age, sex and comorbidities including coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity and smoking; for BRM: volume of breast reduction).9 Selection of covariates for generation of case-mix models was achieved using the approach described by Collett.10 Model estimates were obtained using the GENMOD procedures in SAS V.9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA). The expected reductions in operative time associated with attending experience were plotted. All tests were two-tailed, and p values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

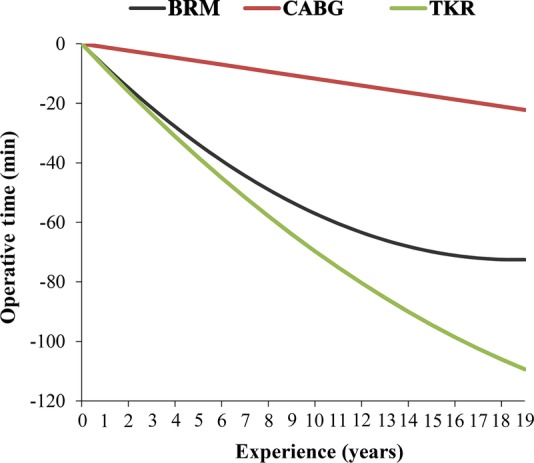

Surgeon and cohort characteristics for each procedure are listed in tables 1 and 2. Figure 1 displays the learning curve of each of the procedures. The number of procedures per surgeon per year are displayed in the online supplementary appendix.

Table 1.

Overview of study participants

| BRM | CABG | TKR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgeon | |||

| Attending surgeons (n) | 8 | 9 | 13 |

| Mean experience, years (SD) | 11.3 (4.5) | 9.7 (5.9) | 14.5 (3.8) |

| Minimum–maximum experience (years) | 1–19 | 1–19 | 1–19 |

| Median volume of cases | 61 | 290 | 99 |

| Range of cases | 11–502 | 52–973 | 10–1871 |

| Patients | |||

| Total number of cases | 1052 | 3254 | 3325 |

| Mean patient age, years (SD) | 36.4 (12.4) | 65.8 (10.4) | 66.0 (11.2) |

| Female sex (%) | 100 | 23.7 | 69.0 |

| Mean size of breast reduction (SD) | 1681.3 (934.4) | – | – |

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 2.3 | 100.0 | 21.4 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (%) | 12.9 | 9.9 | 6.4 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 5.6 | 38.0 | 17.9 |

| Obesity (%) | 33.1 | 34.9 | 25.9 |

| Smoking history (%) | 6.6 | 41.6 | 15.9 |

| Cardiac heart failure (%) | – | 24.2 | – |

| Preoperative cardiogenic shock (%) | – | 2.3 | – |

BRM, bilateral reduction mammoplasty; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; TKR, total knee replacement.

Table 2.

Surgeon and statistical model characteristics

| Surgical procedure | BRM | CABG | TKR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factors included in patient case-mix adjustment | Breast reduction volume | Age, sex, preoperative congestive heart failure, Preoperative cardiogenic shock, diabetes mellitus | Age, sex, coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity smoking |

| Time period data available | 13 years (18/1/1995–21/12/2007) | 9 years (1/5/2002–30/9/2010) | 14 years (28/7/1999–29/6/2009) |

| Surgeons (N) | 8 | 9 | 13 |

| Surgeon-years (N) | 52 | 48 | 123 |

| Procedures (N) | 1052 | 3254 | 3325 |

| Median number of procedures per surgeon (minimum–maximum) | 61 (11–502) | 290 (52–973) | 99 (10–1871) |

| Mean operative time (SD) | 134.4 (34.5) | 180.9 (62.3) | 101.9 (30.3) |

| Model | GEE (clustering and case-mix adjusted; linear and quadratic model used) | GEE (clustering and case-mix adjusted; logarithmic model used) | GEE (clustering and case-mix adjusted; linear and quadratic model used) |

BRM, bilateral reduction mammoplasty; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; GEE, generalised estimating equation; TKR, total knee replacement.

Figure 1.

Learning curves showing bilateral reduction mammoplasty (BRM), coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and total knee replacement (TKR) operative times versus surgeon experience.

A total of 1052 BRMs were completed by eight surgeons. Mean attending experience was 11.3±4.5 years, with a median case volume of 61 (range: 11–502). Mean operative time was 134.4±34.5 min. Multivariate regression showed breast reduction volume to be the only case-mix factor to have a significant effect on operative time. After adjusting for patient characteristics and clustering, we found a significant association between operative time and attending surgeon experience entered both as a linear (p=0.0002) and a quadratic (p=0.0427) term in the model. Five, 10 and 15 years of experience were associated with 33.74, 57.02 and 69.82 min reductions in operative time, respectively, equating to 18.51%, 31.28% and 38.30% reductions (table 3).

Table 3.

Learning curve—reductions in operative time with surgical experience

| Experience | BRM |

CABG |

TKR |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operative time reduction (min) | Total operative time (min) | Operative time reduction (%) | Operative time reduction (min) | Total operative time (min) | Operative time reduction (%) | Operative time reduction (min) | Total operative time (min) | Operative time reduction (%) | |

| 0 | 0 | 193.3097 | 0.0 | 0 | 223.24841 | 0.0 | 0 | 200.1773 | 0.0 |

| 1 | −7.5867 | 185.723 | 3.9 | −1.1694099 | 222.079 | 0.5 | −8.1803 | 191.997 | 4.1 |

| 2 | −14.7546 | 178.5551 | 7.6 | −2.3388198 | 220.90959 | 1.0 | −16.0912 | 184.0861 | 8 |

| 3 | −21.5037 | 171.806 | 11.1 | −3.5082297 | 219.74018 | 1.6 | −23.7327 | 176.4446 | 11.9 |

| 4 | −27.834 | 165.4757 | 14.4 | −4.6776396 | 218.57077 | 2.1 | −31.1048 | 169.0725 | 15.5 |

| 5 | −33.7455 | 159.5642 | 17.5 | −5.8470495 | 217.40136 | 2.6 | −38.2075 | 161.9698 | 19.1 |

| 6 | −39.2382 | 154.0715 | 20.3 | −7.0164594 | 216.23195 | 3.1 | −45.0408 | 155.1365 | 22.5 |

| 7 | −44.3121 | 148.9976 | 22.9 | −8.1858693 | 215.06254 | 3.7 | −51.6047 | 148.5726 | 25.8 |

| 8 | −48.9672 | 144.3425 | 25.3 | −9.3552792 | 213.89313 | 4.2 | −57.8992 | 142.2781 | 28.9 |

| 9 | −53.2035 | 140.1062 | 27.5 | −10.524689 | 212.72372 | 4.7 | −63.9243 | 136.253 | 31.9 |

| 10 | −57.021 | 136.2887 | 29.5 | −11.694099 | 211.55431 | 5.2 | −69.68 | 130.4973 | 34.8 |

| 11 | −60.4197 | 132.89 | 31.3 | −12.863509 | 210.3849 | 5.8 | −75.1663 | 125.011 | 37.5 |

| 12 | −63.3996 | 129.9101 | 32.8 | −14.032919 | 209.21549 | 6.3 | −80.3832 | 119.7941 | 40.2 |

| 13 | −65.9607 | 127.349 | 34.1 | −15.202329 | 208.04608 | 6.8 | −85.3307 | 114.8466 | 42.6 |

| 14 | −68.103 | 125.2067 | 35.2 | −16.371739 | 206.87667 | 7.3 | −90.0088 | 110.1685 | 45 |

| 15 | −69.8265 | 123.4832 | 36.1 | −17.541148 | 205.70726 | 7.9 | −94.4175 | 105.7598 | 47.2 |

| 16 | −71.1312 | 122.1785 | 36.8 | −18.710558 | 204.53785 | 8.4 | −98.5568 | 101.6205 | 49.2 |

| 17 | −72.0171 | 121.2926 | 37.3 | −19.879968 | 203.36844 | 8.9 | −102.427 | 97.7506 | 51.2 |

| 18 | −72.4842 | 120.8255 | 37.5 | −21.049378 | 202.19903 | 9.4 | −106.027 | 94.1501 | 53 |

| 19 | −72.5325 | 120.7772 | 37.5 | −22.218788 | 201.02962 | 10 | −109.358 | 90.819 | 54.6 |

BRM, bilateral reduction mammoplasty; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; TKR, total knee replacement.

A total of 3254 CABGs were completed by nine surgeons. Mean attending experience was 9.7±5.9 years, with a median case volume of 290 (range: 52–973). Mean operative time was 180.9±62.3 min. Multivariate regression showed the following case-mix factors to have a significant effect on operative time: patient age, sex, preoperative cardiogenic shock, diabetes mellitus and preoperative congestive heart failure. After adjusting for patient characteristics and clustering, we found a significant association between operative time and attending surgeon experience entered as a logarithmic term (p=0.0374) in the model. Five, 10 and 15 years of experience were associated with 5.85, 11.69 and 17.54 min reductions in operative time, respectively, equating to 2.61%, 5.22% and 7.83% reductions (table 3).

A total of 3325 TKRs were completed by 13 surgeons. Mean attending experience was 14.5±3.8 years, with a median case volume of 99 (range: 10–1871). Mean operative time was 101.9±30.3 min. Multivariate regression showed the following case-mix factors to have a significant effect on operative time: patient age, sex and comorbidities including coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity and smoking. After adjusting for patient characteristics and clustering, we found a significant association between operative time and attending surgeon experience entered both as a linear (p<0.0001) and a quadratic (p=0.0002) term in the model. Five, 10 and 15 years of experience were associated with 38.20, 69.68 and 94.41 min reductions in operative time, respectively, equating to 19.60%, 35.75% and 48.44% reductions (table 3).

Discussion

We performed a cross-specialty evaluation of learning curves in surgery, investigating over 7000 procedures performed by 30 attending surgeons. By comparing these learning curves using statistically uniform data and techniques, our study permits identification of important commonalities and differentiations, yielding several important findings.

First, in contrast to the notion that efficiency is optimised within a fairly narrow temporal window following the start of clinical practice, our data suggest that operative learning curves, for some procedures, exhibit ongoing improvement in efficiency over the course of a surgeon's career, with time courses much longer than previously anticipated. This emphasises the necessity to draw equitable comparisons between surgeons at similar stages of the learning curve,11 12 and supports proposals for continual monitoring, training and behavioural interventions aiming to accelerate operative maturation.13

Second, our results demonstrate the different learning curve dynamics that exist between procedures. BRM is typified by an initial phase of variability, followed by a period of rapid improvement, followed by a relative plateau phase. TKR and CABG, on the other hand, demonstrate a more linear improvement over time. Such findings suggest that certain procedures may demonstrate characteristic learning curves, with some achieving maturation more rapidly than others. The factors contributing to these characteristics should be the subject of further investigation.

Third, the magnitude of improvements in efficiency over time varies from procedure to procedure. In some cases, efficiency is markedly augmented with increasing surgeon experience (BRM and TKR); in others, however, the improvement is substantially more marginal, and possibly clinically insignificant (CABG; <10% reduction after 15 years of experience). This observation may be because cardiothoracic fellows begin their training as proficient and highly competent general surgery graduates. As demonstrated by previous studies, this may result in attendings achieving a significant portion of their maturation as CABG surgeons during their cardiothoracic fellowship,14–16 diminishing the impact of subsequent increases in experience. Superimposed on this is the possibility that plastic and orthopaedic surgeons may learn a broader range of procedures during their training than cardiothoracic surgeons, precluding as much experience to be gained in a given operative technique—a difference of breadth and depth. This observation suggests that interventions aiming to accelerate surgical experience acquisition, such as simulation training, may be particularly effective for enhancing efficiency in TKR and BRM, but possibly less so in CABG, given the differential impact of individual surgeon experience across these procedures.

In addition to this, procedural learning curves were found to have differential sensitivities to case-mix factors. BRM was only affected by breast reduction volume; in contrast, the TKR learning curve was found to be influenced by a variety of patient-factors including age, sex and comorbidities. This differential is no doubt due, at least in part, to varying tolerances on the part of surgeons in each of the highlighted specialties to operate on patients with marginal health status; this must be taken into consideration when making cross-procedural comparisons.

Importantly, the development of experience-based learning curves, such as those elucidated in this study, has the potential to inform efforts to prospectively monitor individual surgical performance metrics on an ongoing basis. Through the application of iterative quality improvement systems, such as statistical process control (SPC), the depicted learning curves could be utilised as a baseline against which to chart the progress of surgical personnel—whether to meet administrative or educational goals.17 18 Such methodologies are designed to first identify and then address unwarranted variation in clinical processes, which generally leads to substantial improvements in efficiency, safety and quality. While initially conceived for the manufacturing industry, they have recently been recognised as having increasing relevance to the healthcare sphere.19 20 Compared to more traditional approaches of quality control, they offer a more accurate means of assessing performance and guiding improvement initiatives, particularly when they are, as in the case of the data presented here, tailored to a specific operative procedure.11 12

Implementation of SPC offers several potential benefits. Through improvement of surgical performance, these efforts have the potential to simultaneously improve surgical efficiency, safety, quality and cost at the individual as well as institutional levels. In the context of training, mapping of performance throughout a surgeon's career will permit the evolution of young trainees to be monitored, giving rise to appraisals based on performance rather than career chronology alone, potentially ensuring progression only on acquisition of sufficient expertise.3 11 12 21 Deconstruction of the performance curve and comparison of curves between high and low performers will permit the elements contributing to training to be dissected. By doing so, the mechanics of surgical learning will be better understood, providing methods by which the learning curve can be accelerated. SPC methodology also presents a means of accurately assessing the efficacy of new training tools or simulation programmes at the individual level, both rapidly and sensitively. Finally, this methodology may have the capacity to identify deteriorations occurring towards the end of a surgeon's career, serving as a safety monitor and supplementing the introduction of continuing education programmes.4 22

These implications, however, must be considered in the context of this study's limitations:

Our focus on operative efficiency as an outcome for CABG, TKR and BRM did not explicitly incorporate considerations related to surgical safety such as complication rates, which may be considered more patient focused. However, in a variety of work both within surgery and outside, time of task completion has been used as a robust indicator of learning and outcome.3 23–27 Studies have indicated that faster completion of the TKR procedure is associated with better outcomes.28 Further, operative times in CABG are closely linked with patient outcome; specifically, elevated CPB times are associated with increased risks of stroke and renal failure.29

We performed a retrospective investigation at a single academic medical centre, which may be criticised for limiting data quality. This approach, however, removed any Hawthorne effect with regard to efficiency assessment. We also did not account for changes in technology, operative technique or local hospital resources occurring during the retrospective capture of our analysis.

Our investigation utilised years of training and/or practice as a proxy for surgical experience, rather than number of cases performed. The latter may have permitted volume-efficiency relationships to be better elucidated, and for the specific number of cases required to reach maturation to be determined. This limitation is due to our inability to capture procedures performed at other institutions by surgeons in our study cohort, either before or during the study phase; for the TKR and BRM data sets, several of the surgeons included in the data set performed procedures elsewhere; for the CABG data set, most of the surgeons operated exclusively at the host institution (with the exception of one). However, number of years of training and/or practice has been utilised as an acceptable substitute for surgical experience in prior published studies in the surgical literature.3 4 8 11 12 30

Additional controls could have been incorporated into the model, such as team familiarity, team experience, fellowship-status and the presence of a resident. Although cross-specialty analyses of such work have yet to be conducted, evidence exists at the procedure-specific level.16 30

This study quantitatively characterised the learning curves of three procedures from distinct surgical specialties. We identified common trends in surgical learning and demonstrated that, dependent on the procedure, surgical experience can serve as a powerful driver of improvement or have clinically insignificant impacts on efficiency. Appreciation of these findings may guide implementation of performance-tracking and quality-improvement strategies in surgery.

Footnotes

Contributors: AD, DPO, MJC, MM, SRL contributed by taking part in study concept and design. MJC, MM were involved in data collection. AD and SRL analysed the data. AD, MJC and MM participated in manuscript preparation. AD, DPO, MJC, MM and SRL revised the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board (protocol number 2006p000586).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Catchpole K, Mishra A, Handa A et al. Teamwork and error in the operating room: analysis of skills and roles. Ann Surg 2008;247:699–706. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181642ec8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leape LL. Error in medicine. JAMA 1994;272:1851–7. 10.1001/jama.1994.03520230061039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carty MJ, Chan R, Huckman R et al. A detailed analysis of the reduction mammoplasty learning curve: a statistical process model for approaching surgical performance improvement. Plast Reconstr Surg 2009;124:706–14. 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181b17a13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duclos A, Peix JL, Colin C et al. Influence of experience on performance of individual surgeons in thyroid surgery: prospective cross sectional multicentre study. BMJ 2012;344:d8041 10.1136/bmj.d8041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrysson IJ, Cook J, Sirimanna P et al. Systematic review of learning curves for minimally invasive abdominal surgery: a review of the methodology of data collection, depiction of outcomes, and statistical analysis. Ann Surg 2014;260:37–45. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tekkis PP, Senagore AJ, Delaney CP et al. Evaluation of the learning curve in laparoscopic colorectal surgery: comparison of right-sided and left-sided resections. Ann Surg 2005;242:83–91. 10.1097/01.sla.0000167857.14690.68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sutton DN, Wayman J, Griffin SM. Learning curve for oesophageal cancer surgery. Br J Surg 1998;85:1399–402. 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00962.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maruthappu M, Gilbert B, El-Harasis MA et al. The influence of experience on individual surgical performance: a systematic review. Ann Surg 2014. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramsay CR, Grant AM, Wallace SA et al. Statistical assessment of the learning curves of health technologies. Health Technol Assess 2001;5:1–79. 10.3310/hta5120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collett D. Modelling survival data in medical research. Boca Raton, LA: CRC, Chapman Hall, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maruthappu M, Duclos A, Orgill D et al. A monitoring tool for performance improvement in plastic surgery at the individual level. Plast Reconstr Surg 2013;131:702e–10. 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182865a0c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duclos A, Carty MJ, Peix JL et al. Development of a charting method to monitor the individual performance of surgeons at the beginning of their career. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e41944 10.1371/journal.pone.0041944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawe SR, Windsor JA, Broeders JA et al. A systematic review of surgical skills transfer after simulation-based training: laparoscopic cholecystectomy and endoscopy. Ann Surg 2014;259:236–48. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murzi M, Cerillo AG, Bevilacqua S et al. Traversing the learning curve in minimally invasive heart valve surgery: a cumulative analysis of an individual surgeon's experience with a right minithoracotomy approach for aortic valve replacement. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Song M-H, Tajima K, Watanabe T et al. Learning curve of coronary surgery by a cardiac surgeon in Japan with the use of cumulative sum analysis. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2005;53:551–6. 10.1007/s11748-005-0066-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ElBardissi AW, Duclos A, Rawn JD et al. Cumulative team experience matters more than individual surgeon experience in cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013;145:328–33. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wheeler DJ, Chambers DS. Understanding statistical process control. Knoxville, Tenn: SPC Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duclos A, Touzet S, Soardo P et al. Quality monitoring in thyroid surgery using the Shewhart control chart. Br J Surg 2009;96:171–4. 10.1002/bjs.6418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tekkis PP, McCulloch P, Steger AC et al. Mortality control charts for comparing performance of surgical units: validation study using hospital mortality data. BMJ 2003;326:786 10.1136/bmj.326.7393.786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duclos A, Polazzi S, Lipsitz SR et al. Temporal variation in surgical mortality within French hospitals. Med Care 2013;51:1085–93. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182a97c54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maruthappu M, Carty MJ, Lipsitz SR et al. Patient- and surgeon-adjusted control charts for monitoring performance. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004046 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neumayer LA, Gawande AA, Wang J Jr et al. Proficiency of surgeons in inguinal hernia repair: effect of experience and age. Ann Surg 2005;242:344–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pisano GP, Bohmer MJ, Edmondson AC. Organizational differences in rates of learning: evidence from the adoption of minimally invasive cardiac surgery. Manag Sci 2001;47:752–68. 10.1287/mnsc.47.6.752.9811 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edmondson A, Winslow A, Bohmer R et al. Learning how and learning what: effects of tacit and codified knowledge on performance improvement following technology adoption. Decis Sci 2003;34:197–223. 10.1111/1540-5915.02316 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Epple D, Argote L, Devadas R. Organizational learning curves: a method for investigating intra-plant transfer of knowledge acquired through learning by doing. Organ Sci 1991;2:58–70. 10.1287/orsc.2.1.58 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Argote L, Epple D. Learning curves in manufacturing. Science 1990;247:920–4. 10.1126/science.247.4945.920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ballantyne GH, Ewing D, Capella RF et al. The learning curve measured by operating times for laparoscopic and open gastric bypass: roles of surgeon's experience, institutional experience, body mass index and fellowship training. Obes Surg 2005;15:172–82. 10.1381/0960892053268507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peersman G, Laskin R, Davis J et al. Prolonged operative time correlates with increased infection rate after total knee arthroplasty. HSS J 2006;2:70–2. 10.1007/s11420-005-0130-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sniecinski R, Chandler W. Activation of the hemostatic system during cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesth Analg 2011;113:1319–33. 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182354b7e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu R, Carty MJ, Orgill DP et al. The teaming curve: a longitudinal study of the influence of surgical team familiarity on operative time. Ann Surg 2013;258:953–7. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182864ffe [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]