Abstract

Objective

Compliance with guidelines is increasingly used to benchmark the quality of hospital care, however, very little is known on patients admitted with acute coronary syndromes (ACS) and treated palliatively. This study aimed to evaluate the baseline characteristics and outcomes of these patients.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

Eighty-two Swiss hospitals enrolled patients from 1997 to 2014.

Participants

All patients with ACS enrolled in the AMIS Plus registry (n=45 091) were analysed according to three treatment groups: palliative treatment, defined as use of aspirin and analgesics only and no reperfusion; conservative treatment, defined as any treatment including antithrombotics or anticoagulants, heparins, P2Y12 inhibitors, GPIIb/IIIa but no pharmacological or mechanical reperfusion; and reperfusion treatment (thrombolysis and/or percutaneous coronary intervention during initial hospitalisation). The primary outcome measure was in-hospital mortality and the secondary measure was 1-year mortality.

Results

Of the patients, 1485 (3.3%) were palliatively treated, 11 119 (24.7%) were conservatively treated and 32 487 (72.0%) underwent reperfusion therapy. In 1997, 6% of all patients were treated palliatively and this continuously decreased to 2% in 2013. Baseline characteristics of palliative patients differed in comparison with conservatively treated and reperfusion patients in age, gender and comorbidities (all p<0.001). These patients had more in-hospital complications such as postadmission onset of cardiogenic shock (15.6% vs 5.2%; p<0.001), stroke (1.8% vs 0.8%; p=0.001) and a higher in-hospital mortality (25.8% vs 5.6%; p<0.001).The subgroup of patients followed 1 year after discharge (n=8316) had a higher rate of reinfarction (9.2% vs 3.4%; p=0.003) and mortality (14.0% vs 3.5%; p<0.001).

Conclusions

Patients with ACS treated palliatively were older, sicker, with more heart failure at admission and very high in-hospital mortality. While refraining from more active therapy may often constitute the most humane and appropriate approach, we think it is important to also evaluate these patients and include them in registries and outcome evaluations.

Clinical trial number

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01 305 785.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study presenting characteristics and outcomes of a large cohort of patients admitted for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and treated only palliatively. It compares the differences in baseline characteristics and outcomes in hospital and 1 year after discharge of these patients with patients treated conservatively or with reperfusion therapy.

Whereas it may often be completely appropriate to provide restrictive and palliative care only for elderly patients with very poor prognosis, this study shows a much larger grey zone of decision-making.

With this study, it was not possible to find evidence of the exact reasons for withholding active therapy by only treating patients palliatively.

This study showed that an international consensus should be reached on whether such patients should be included in the overall evaluation of patients with ACS outcomes.

Introduction

Guideline recommended strategies are derived from prospective randomised trials and expert consensus. This may result in bias since the therapies are only studied in patients who consent and do not have exclusion criteria. Thus, very little is known on an important subgroup of patients who at the time of admission for various reasons received restricted or palliative treatment only. Reasons for withholding comprehensive and/or invasive therapy may be a very limited life expectancy, advanced age or severe comorbidity. These patients are not represented in prospective trials and often not included in registries. They are a poorly defined group in terms of presentation characteristics and outcome, but they might have a profound influence on outcome statistics, benchmarking and resource utilisation.

Since 1997, we have followed diagnostic and treatment strategies in a long-term nationally based registry in which all patients are included once a hospital decides to collaborate for a defined period of time. The present details of the registry and participants have been described recently.1–3

Patients were assigned to one of three groups according to the therapy received. We present characteristics and outcomes of a large cohort of patients admitted to Swiss hospitals with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) who received primary palliative treatment.

Methods

The AMIS Plus project is an ongoing nationwide prospective registry of patients with ACS admitted to hospitals in Switzerland, supported by the Swiss Societies of Cardiology, Internal Medicine and Intensive Care Medicine. It was founded in 1997 with the goal to understand the transfer, use and practicability of knowledge gained from randomised trials and to generate data for the planning of subsequent prospective and randomised studies. Details have been previously published.1 Of 106 hospitals treating ACS in Switzerland, 82 temporarily or continuously enrolled patients in AMIS Plus. Participating centres, ranging from community institutions to large tertiary facilities, provide blinded data for each patient through standardised internet-based or paper-based questionnaires. Participating centres are strongly encouraged to enrol all patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria to avoid selection bias. Hospital data are provided and completed by the treating physician or a trained study nurse. All data are checked for completeness, plausibility and consistency by the AMIS Plus Data Centre in the Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Prevention Institute at the University of Zurich, and treating physicians or study nurses are queried when necessary. Centres are randomly audited and the quality of data checked by the Clinical Trials Unit on an annual basis since 2011.

In this study, patients with ACS were divided into groups according to the therapy received during the initial hospitalisation: palliative treatment, defined as use of aspirin and analgesics only, without the use of any other antithrombotics, anticoagulants, heparins, P2Y12 inhibitors, GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors and no pharmacological or mechanical reperfusion; conservative treatment, defined as any treatment including antithrombotics or anticoagulants, heparins, P2Y12 inhibitors (clopidogrel, prasugrel or ticagrelor), GPIIb/IIIa but no pharmacological or mechanical reperfusion; and reperfusion treatment, including thrombolysis and/or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Comorbidities of the patients were assessed using the weighted Charlson Index.4 5 Risk factors were documented in the patient's medical history: dyslipidaemia, arterial hypertension and diabetes were assigned if the patient had been previously treated and/or diagnosed by a physician. Documentation of the risk factors provided by the local physicians was accepted as stated. Patients were defined as obese if the body mass index was ≥30 kg/m2 and as smokers if the patient was a current smoker at the time of the cardiovascular event.

For the present analysis, the primary outcome measure was in-hospital mortality and the secondary outcome measure was 1-year mortality after discharge. Additionally, the major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events in-hospital (MACCE—composite end point of reinfarction, stroke and/or death) and adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events during follow-up (MACCE—composite end point of reinfarction, stroke, any reinterventions and/or death) were assessed.

Patient selection

The present analysis included all patients with ACS enrolled in AMIS Plus between January 1997 and April 2014. ACS included acute myocardial infarction (AMI), defined according to the universal definitions of MI by characteristic symptoms and/or ECG changes and cardiac marker elevation (either creatine kinase MB fraction at least twice the upper limit of normal or troponin I or T above individual hospital cut-off levels for MI), and unstable angina (symptoms or ECG changes compatible with ACS and cardiac marker levels lower than cut-off or normal levels).6 7 Classification of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) included evidence of AMI as above and ST-segment elevation and/or new left bundle branch block on the initial ECG. Non-STEMI (NSTEMI) included patients with ischaemic symptoms, ST-segment depression or T-wave abnormalities in the absence of ST elevation on the initial ECG.

Since 2006, patients from 59 centres were asked for written consent to a telephone follow-up contact 12 months after discharge.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as means ±1 SD or medians with IQR and were compared between groups using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical data are presented as percentages and compared between groups using Pearson's χ2 test. The Breslow-Day test of homogeneity of the OR was used to identify subgroups of patients with a particularly high reduction of palliative treatment between time periods. Linear regression was used to analyse trends in age over time and differences between trends of patients treated palliatively and those treated otherwise. Two-sided p Values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (V.22, Armonk, New York: IBM Corp.)

Results

Between January 1997 and April 2014, 45 279 patients with ACS from 82 Swiss hospitals were enrolled in the AMIS Plus registry. The data on the therapies received were missing for 188 (0.4%) patients. Therefore, complete data were available from 45 091 patients. Among these patients, 72% underwent reperfusion, 24.7% were treated conservatively and 3.3% palliatively.

The baseline characteristics according to therapy received during the index hospitalisation are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with ACS according to treatment (N=45 091)

| Palliative | Conservative | Reperfusion | p Value palliative vs others | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 1485 (3.3%) | 11 119 (24.7%) | 32 487 (72.0%) | |

| Sex, male (%) | 867 (58.4) | 7113 (64.0) | 24 844 (76.5) | <0.001 |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 76.7 (12.3) | 72.3 (12.9) | 63.5 (12.4) | <0.001 |

| Delay median (IQR) | 305 min (120, 984 min) | 350 min (135, 1005 min) | 209 min (105 540 min) | <0.001 |

| Resuscitation prior to admission | 84/1465 (5.7) | 1388/10 992 (3.5) | 1708/32 065 (5.3) | 0.14 |

| Symptoms at admission | ||||

| Pain (%) | 930/1363 (68.2) | 8584/10 674 (80.4) | 27 415/30 911 (88.7) | <0.001 |

| Dyspnoea (%) | 646/1266 (51.0) | 4014/10 138 (39.6) | 7034/28 607 (24.6) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 228/1205 (18.9) | 784/8272 (9.5) | 996/29 444 (3.4) | <0.001 |

| STEMI (%) | 585 (39.4) | 4578 (41.2) | 20 393 (62.8) | <0.001 |

| Killip classes 3/4 (%) | 266/1457 (18.3) | 1182/10 971 (10.8) | 1780/32 057 (5.6) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 984/1353 (72.7) | 7046/10 620 (66.3) | 17 576/30 931 (56.8) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes (%) | 420/1372 (30.6) | 2795/10 753 (26.0) | 5599/31 234 (17.9) | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidaemia (%) | 576/1124 (51.2) | 5194/9642 (53.9) | 17 237/29 302 (58.8) | <0.001 |

| Current smoker (%) | 255/1210 (21.1) | 2779/10 123 (27.5) | 12 817/30 069 (42.6) | <0.001 |

| Obesity (BMI>30) (%) | 185/983 (18.8) | 1559/8413 (18.5) | 5786/27 653 (20.9) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 675/1334 (50.6) | 460/9658 (47.8) | 9980/30 832 (32.4) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure (%) | 145/1061 (13.7) | 535/6692 (8.0) | 538/26 742 (2.0) | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease (%) | 150/1062 (14.1) | 710/6741 (10.5) | 1237/27 504 (4.5) | <0.001 |

| Hemiplegia (%) | 23/1061 (2.2) | 103/6692 (1.5) | 108/26 742 (0.4) | <0.001 |

| Dementia (%) | 87/1061 (8.2) | 375/6692 (5.6) | 187/26 742 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| Chronic lung disease (%) | 121/1062 (11.4) | 696/6741 (10.3) | 1280/27 504 (4.7) | <0.001 |

| Moderate to severe liver disease (%) | 22/1062 (2.1) | 63/6741 (0.9) | 118/27 310 (0.4) | <0.001 |

| Moderate to severe renal disease (%) | 223/1062 (21.0) | 1013/6741 (15.0) | 1213/27 504 (4.4) | <0.001 |

| Cancer disease (%) | 120/1062 (11.3) | 572/6700 (8.5) | 1331/26 794 (5.0) | <0.001 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index >1 (%) | 577/1061 (54.4) | 2791/6692 (41.7) | 4901/26 742 (18.3) | <0.001 |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

The patients with ACS treated palliatively differed in all baseline characteristics from the patients treated conservatively as well as the patients who received thrombolytic therapy or underwent PCI. They were older, predominantly women, with more risk factors such as hypertension, and suffered more frequently from diabetes, heart failure, cerebrovascular diseases, renal disease and dementia. Patients with ACS treated palliatively more frequently presented with atypical symptoms, less pain, dyspnoea, atrial fibrillation, NSTEMI and a higher Killip class.

Seventy-two per cent of all patients with ACS treated with reperfusion, 45% of all patients treated palliatively and 45% of all those treated conservatively were admitted to hospitals with catheter laboratory facilities. For patients treated palliatively, the delay between symptom onset and admission was much longer than the reperfusion group but shorter than the conservative group. Furthermore, more than one-third of the patients treated palliatively (36.3%) were on anticoagulants before admission in comparison to those treated conservatively (6.4%) and those who underwent reperfusion (4.2%).

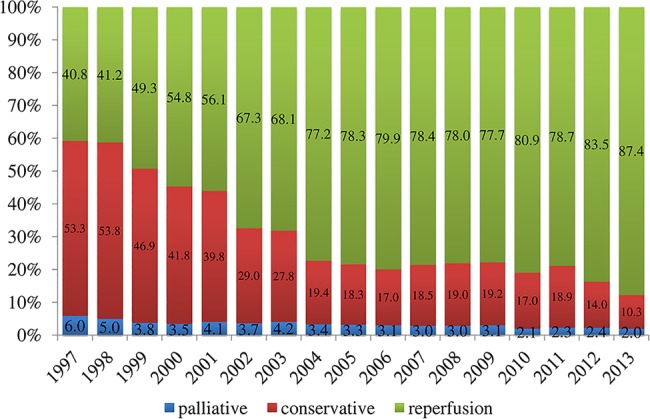

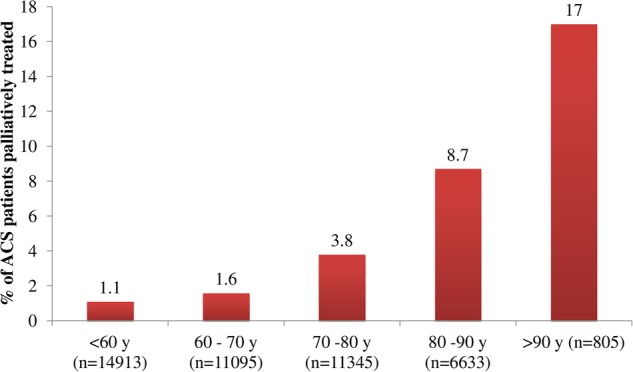

The percentage of patients with ACS treated without reperfusion continuously decreased between 1997 and 2013. Conservative treatment dropped from 53.3% to 10.3% and palliative treatment from 6% to 2% (figure 1). The percentage of patients with ACS who were palliatively treated increased with increased age (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Temporal trends of treatments, 1997–2014.

Figure 2.

Palliatively treated patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) according to age categories.

Comparison of the two periods (1997–2005 and 2006–2014) showed a significant decrease in the use of palliative therapy in patients with ACS, particularly in patients admitted with Killip class >2, from 11% to 5.9% (p for the test of homogeneity of the OR was 0.028). The same trend was seen for patients 75 years of age and younger, dropping from 2.2% to 1.1% (p for the test of homogeneity of the OR was <0.001).

Trend analyses per quartile of time showed more females and patients with moderate to severe renal diseases received palliative treatment, but less resuscitated patients, less patients with typical symptoms, less patients with coronary artery disease and heart failure and less patients who presented with STEMI or acute decompensation (table 2). Additionally, comparisons of the temporal trends of patients treated palliatively and those who underwent reperfusion showed significant differences in the trends of gender, age, resuscitation, typical symptoms, Killip classes above 2, dyslipidaemia and smoking, as well as heart failure and comorbidities (table 2).

Table 2.

Trends in baseline characteristics of patients with ACS according to treatment (N=45 091)

| Palliative (n=1485) |

Conservative (n=11 119) |

Reperfusion (n=32 487) |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1997–2001 | 2002–2005 | 2006–2009 | 2010–2013 | P for trends | P for difference in trends vs reperfusion | 1997–2001 | 2002–2005 | 2006– 2009 | 2010– 2013 | P for trends | P for difference in trends vs reperfusion | 1997–2001 | 2002–2005 | 2006–2009 | 2010– 2013 | P for trends | |

| Number of patients | 414 | 416 | 382 | 273 | 4337 | 2629 | 2277 | 1876 | 4398 | 8411 | 9742 | 9936 | |||||

| Males | 65.5 | 56.3 | 52.6 | 59.0 | 0.018 | 0.003 | 67.6 | 61.4 | 60.3 | 63.8 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 76.6 | 76.9 | 76.6 | 75.6 | 0.19 |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 78.8 (12) | 77.8 (12) | 80.6 (11) | 75.5 (13) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 68.9 (13) | 74.6 (12) | 75.8 (13) | 73.1 (13) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 62.2 (12) | 62.9 (12) | 63.5 (12) | 64.7 (13) | <0.001 |

| Resuscitation prior to admission | 8.7 | 6.1 | 3.1 | 4.4 | 0.002 | 0.011 | 5.2 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 3.1 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 5.9 | 4.4 | 5.2 | 6.0 | 0.019 |

| Symptoms at admission | |||||||||||||||||

| Pain | 81.6 | 57.8 | 66.3 | 67.3 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 87.4 | 72.5 | 76.4 | 80.5 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 93.2 | 78.3 | 90.3 | 94.4 | <0.001 |

| Dyspnoea | 54.9 | 45.7 | 54.5 | 49.4 | 0.68 | <0.001 | 31.6 | 41.2 | 46.1 | 47.1 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 21.3 | 17.2 | 26.4 | 31.6 | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 18.8 | 18.6 | 19.4 | 18.8 | 0.93 | 0.50 | 7.9 | 10.1 | 10.4 | 8.9 | 0.40 | 0.001 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 4.0 | 0.005 |

| STEMI | 51.0 | 41.1 | 32.2 | 29.3 | <0.001 | 0.083 | 48.6 | 39.4 | 35.7 | 33.0 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 78.8 | 63.5 | 59.5 | 58.2 | <0.001 |

| Killip classes 3/4 | 22.3 | 17.8 | 16.4 | 15.6 | 0.019 | 0.002 | 10.0 | 12.0 | 11.1 | 10.3 | 0.53 | <0.001 | 5.3 | 4.1 | 5.7 | 6.8 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 62.0 | 71.5 | 81.3 | 79.4 | <0.001 | 0.033 | 55.0 | 70.4 | 76.7 | 75.0 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 47.4 | 54.5 | 59.5 | 60.4 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 27.9 | 32.4 | 34.2 | 27.2 | 0.75 | 0.13 | 23.0 | 28.6 | 29.0 | 25.8 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 16.6 | 17.8 | 17.7 | 18.9 | 0.002 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 47.2 | 51.6 | 48.9 | 60.1 | 0.013 | 0.011 | 50.7 | 57.2 | 52.7 | 58.4 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 57.8 | 64.3 | 53.9 | 59.3 | 0.001 |

| Current smoker | 27.6 | 17.2 | 14.7 | 25.1 | 0.088 | 0.001 | 33.0 | 22.9 | 22.7 | 26.1 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 45.6 | 43.7 | 41.8 | 41.6 | <0.001 |

| Obesity (BMI>30) | 15.9 | 18.8 | 18.8 | 21.8 | 0.16 | 0.98 | 19.0 | 16.9 | 18.6 | 19.9 | 0.46 | 0.009 | 17.8 | 19.8 | 21.1 | 22.8 | <0.001 |

| CAD | 56.8 | 52.4 | 50.7 | 40.2 | <0.001 | 0.068 | 46.6 | 51.6 | 51.0 | 40.4 | 0.003 | <0.001 | 34.9 | 32.4 | 34.3 | 29.6 | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 23.5 | 15.9 | 14.6 | 7.8 | 0.001 | 0.039 | 12.4 | 9.3 | 8.1 | 5.7 | <0.001 | 0.030 | 3.1 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 0.083 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 17.6 | 13.4 | 14.3 | 14.5 | 0.87 | 0.74 | 8.8 | 11.6 | 10.0 | 9.9 | 0.16 | 0.049 | 5.5 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 0.12 |

| Dementia | 5.9 | 6.6 | 9.4 | 9.3 | 0.14 | 0.47 | 2.1 | 5.1 | 6.2 | 5.9 | 0.050 | 0.008 | 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.004 |

| Lung disease | 14.7 | 14.1 | 8.3 | 11.2 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 16.6 | 10.8 | 10.0 | 9.4 | 0.014 | 0.47 | 9.2 | 4.7 | 4.4 | 4.7 | 0.44 |

| Renal disease | 11.8 | 17.4 | 24.8 | 22.3 | 0.034 | 0.16 | 11.4 | 12.0 | 18.1 | 15.7 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 2.8 | 3.6 | 4.1 | 5.4 | <0.001 |

| Cancer disease | 11.8 | 10.6 | 12.4 | 10.8 | 0.91 | 0.25 | 5.7 | 9.0 | 8.5 | 8.3 | 0.81 | 0.001 | 7.1 | 4.5 | 4.3 | 6.0 | <0.001 |

| CCI>1 | 55.9 | 54.5 | 57.3 | 50.0 | 0.33 | 0.020 | 39.4 | 41.5 | 44.2 | 39.1 | 0.35 | <0.001 | 23.4 | 17.7 | 16.9 | 20.1 | 0.001 |

Age in mean (SD), all other results in percentage.

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; CCI, Charlson comorbidity Index; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

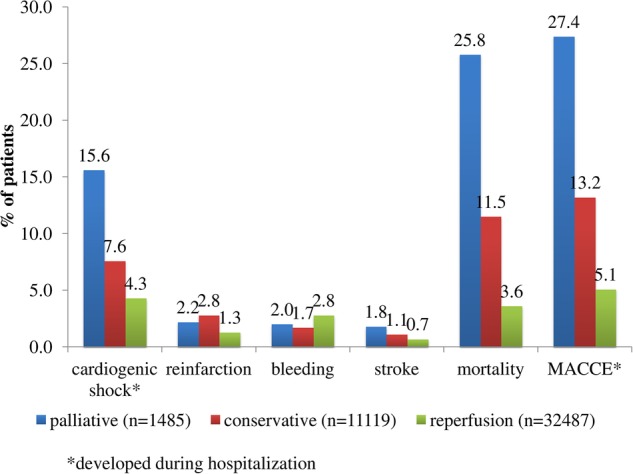

Patients treated palliatively compared with patients treated with antiplatelets and/or reperfusion were at greater risk of developing cardiogenic shock during hospitalisation (16% vs 5%; p<0.001) and stroke (2% vs 1%; p=0.001), while bleeding (2.0% vs 2.6%; p=0.36) and reinfarction in-hospital were similar (2.3% vs 1.7%; p=0.18). Crude in-hospital mortality was 25.8% in the palliative group compared with 5.6% for the others (p<0.001) and MACCE (27.4% vs 7.2%; p<0.001; figure 3). The median length of stay was 9 days (IQR 5–15 days) for the palliatively treated, 8 days (IQR 4–13 days) for the conservatively treated and 5 days (IQR 2–9 days) for the reperfusion patients (p<0.001). Of the palliatively treated patients who survived hospital stay (n=1102), 225 (20.4%) were discharged home with homecare assistance or transferred to a retirement or nursing home compared with 10.4% of conservatively treated patients (1005/9841) and 1.5% (464/31 318) of patients who underwent reperfusion.

Figure 3.

In-hospital complications and outcomes according to therapies received during the index hospitalisation. Cardiogenic shock—developing during hospitalisation. MACCE—major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events in-hospital—composite end point of reinfarction, stroke or death.

In-hospital mortality decreased significantly between 1997 and 2013 in the groups of patients treated palliatively or with reperfusion, but not in those treated conservatively (table 3).

Table 3.

Trends in mortality of patients with ACS according to treatment (N=45 091)

| Palliative (n=1485) |

Conservative (n=11 119) |

Reperfusion (n=32 487) |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1997–2001 | 2002–2005 | 2006–2009 | 2010–2013 | P for trends | 1997–2001 | 2002–2005 | 2006–2009 | 2010–2013 | P for trends | 1997–2001 | 2002–2005 | 2006–2009 | 2010–2013 | P for trends | |

| Number of patients | 414 | 416 | 382 | 273 | 4337 | 2629 | 2277 | 1876 | 4398 | 8411 | 9742 | 9936 | |||

| In-hospital mortality (%) | 30.4 | 23.8 | 25.7 | 22.0 | 0.025 | 10.9 | 13.1 | 11.9 | 10.0 | 0.55 | 5.1 | 3.1 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 0.002 |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome.

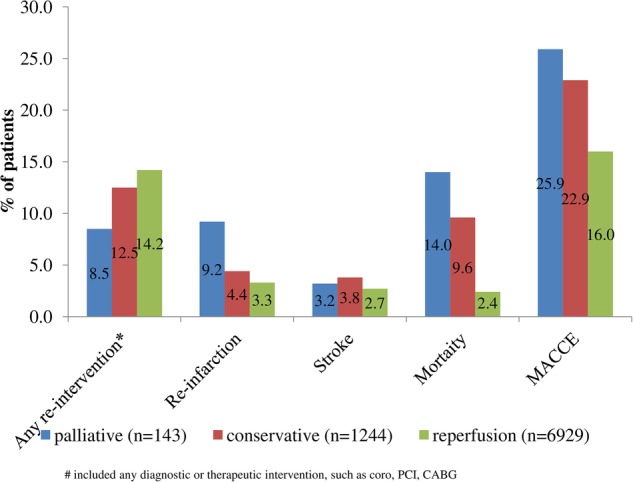

Since 2006, a subgroup of patients with ACS was followed 1 year after discharge. From a total of 22 926 patients who could have possibly been included in the follow-up, 10 770 (47%) were asked to take part. Of these patients, 1912 (17.8%) refused their consent leaving 8858 patients available for follow-up. The follow-up interview was consequently carried out with 8316 patients: 143 (1.7%) patients had been treated palliatively, 1244 (15%) conservatively and 6929 (83.3%) had received reperfusion treatment during the index hospitalisation. The outcomes of these patients 1 year after discharge are shown in figure 4.

Figure 4.

Outcome of patients with ACS 1 year after discharge according to therapy received. Any reintervention included any diagnostic (coronary angiography) or therapeutic intervention, such as percutaneous coronary intervention, implantation of pacemaker, bypass surgery, etc. MACCE during follow-up, major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events—composite end point of reinfarction, stroke, any reinterventions and/or death; ACS, acute coronary syndrome.

Patients admitted for ACS and treated palliatively suffered reinfarction (9.2% vs 3.4% in others; p=0.003) more frequently and died more often during the first year after discharge (14.0% vs 3.5%; p<0.001).

There were no significant differences in mortality 1 year after discharge over time across the three treatment groups (table 4).

Table 4.

Trends in mortality of patients with ACS according to treatment 1 year after discharge (N=8316)

| Palliative (n=143) |

Conservative (n=1244) |

Reperfusion (n=6929) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002–2005 | 2006–2009 | 2010–2013 | P for trends | 2002–2005 | 2006–2009 | 2010–2013 | P for trends | 2002–2005 | 2006–2009 | 2010–2013 | P for trends | |

| Number of patients | 28 | 83 | 32 | 171 | 707 | 366 | 734 | 3824 | 2371 | |||

| Mortality 1 year after discharge (%) | 21.4 | 12.0 | 12.5 | 0.34 | 12.3 | 9.5 | 8.7 | 0.24 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 0.067 |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome.

Discussion

This study provides evidence that the population which received palliative therapy is older and sicker when compared with patients who underwent conservative or reperfusion treatment and the percentage of palliatively treated patients increased with age. Adding days and weeks to a life is not the only goal but to add quality of life to this time. The study shows that these questions are addressed individually. Owing to the substantial lack of studies on this issue, it is difficult to compare these results with other situations. It is beyond the scope of this study and manuscript to analyse why a palliative option was chosen. Age may at least in part explain the restrictive treatment decision. A former analysis showed that elderly patients admitted for ACS received fewer guideline-recommended medical and interventional therapies.8 Whereas a higher proportion of patients with malignant disease is to be expected in the palliative treated group, the higher prevalence of heart failure should be interpreted more cautiously, although a palliative care for patients with advanced heart failure is well established.9 Only patients presenting with cardiogenic shock may be considered for restrictive end-of-life care in connection with other unfavourable characteristics. Our data, however, show a substantial number of patients who were initially stable on admission but developed shock while receiving palliative treatment. This, and the relatively high survival rate after 1 year for the group as a whole, may be indicators for undertreatment in certain subgroups. At least for the long-term survivors, the restrictive treatment decision should be questioned as they have a more complicated follow-up with more reinfarctions and rehospitalisations.

Over time the population offered palliative treatment only has decreased and was smaller in tertiary care centres. This may point to non-homogenous criteria for treatment decisions which may have changed over time given the increasing age and increasing comorbidities of the whole infarct population. Whereas it may often be completely appropriate to provide restrictive and palliative care only for elderly patients with a very poor prognosis, our analysis shows a much larger grey zone of decision-making. This warrants further investigation.

To the best our knowledge, there are no systematic data available on patients with ACS who were not given active therapy for whatever reason. There are few case reports with regard to treatment of patients with MI and concomitant severe cancer diseases.10 11 Fenning et al12 used two prognostic tools (Golden Standards Framework and GRACE Score) to identify patients with ACS approaching end of life and who were therefore eligible for palliative care. The patients with ACS identified as requiring end-of-life care were older, had more comorbidities, were more likely to be readmitted during follow-up and had higher mortality than those who did not meet these criteria. This is in accordance with our results, which showed that palliatively treated patients suffered reinfarction more frequently during the 1 year period after discharge.

This raises the question of whether an effort is necessary to improve compliance by also strictly adhering to guidelines for patients where analgesic therapy only would be the most humane approach. The second question is how these palliative patients impact the quality control and benchmarking processes. According to the results of this study, the overall crude in-hospital mortality of all patients with ACS during the past 17 years was 6.3%, but after exclusion of the patients treated palliatively this was significantly lower with a mortality rate of 5.6%.

Limitations

An important limitation of our study is the lack of evidence for the exact reasons to withhold active therapy and to treat palliatively only. We did not analyse the reasons for choosing ‘palliative care’ as the initial strategy and thereby withholding prognostic favourable treatment options to these patients; nor do we have the means to do this at random. Analysis of such decision-making under time pressure involving medical perspectives (age, comorbidity) and patient's wishes and their quality of life equally is beyond the scope of an infarction registry, and we accept that there are good reasons for deciding on palliative treatment for some patients.

However, it would be almost impossible to gain reliable data on decision-making in the context of a national registry. Furthermore, some misclassifications cannot be excluded due to the fact that some palliatively treated patients died before they could be treated invasively.

Our study should also be interpreted in the context of the following limitations: the weaknesses of AMIS Plus are common to all registries. Participation in the AMIS Plus registry is voluntary; the number of hospitals varied over the years and this might have caused an unrecognised exclusion bias in patients treated palliatively. However, the large number of patients and the long-lasting continuous collection of data involving more than 75% of Swiss hospitals treating patients with ACS enable analysis of the observed data. Data quality was checked by external audits.

Conclusions

Patients with ACS treated palliatively were older, sicker, with more heart failure at admission and very high in-hospital mortality. Changes of treatment decisions over time and the proportion of patients surviving 1 year suggest in part non-homogenous and potentially questionable decision criteria. While refraining from more active therapy may be the most humane and appropriate approach in many patients, in others it represents under treatment. In any case, this patient group warrants further study and should be included in outcome statistics and registries.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank our sponsors for their financial support. They also thank Jenny Piket for proofreading this manuscript.

Footnotes

Collaborators: AMIS Plus Participants 1997–2014: The authors would like to express their gratitude to the teams of the following hospitals (listed in alphabetical order with the names of the local principal investigators): Aarau, Kantonsspital (P Lessing), Affoltern am Albis, Spital (F Hess), Altdorf, Kantonsspital Uri (R Simon), Altstätten, Spital (PJ Hangartner), Baden, Kantonsspital (U Hufschmid), Basel, St. Claraspital (B Hornig), Basel, Universitätsspital (R Jeger), Bern, Beau-Site Klinik (S Trummler), Bern, Inselspital (S Windecker), Bern, Hirslanden Salem-Spital (T Rueff), Bern, Tiefenauspital (P Loretan), Biel, Spitalzentrum (C Roethlisberger), Brig-Glis, Oberwalliser Kreisspital (D Evéquoz), Bülach, Spital (G Mang), Burgdorf, Regionalspital Emmental (D Ryser), Chur, Rätisches Kantons- und Regionalspital (P Müller), Chur, Kreuzspital (R Jecker), Davos, Spital (W Kistler), Dornach, Spital (A. Droll), Einsiedeln, Regionalspital (S Stäuble), Flawil, Spital (G Freiwald), Frauenfeld Kantonsspital (HP Schmid), Fribourg, Hôpital cantonal (JC Stauffer/S Cook), Frutigen, Spital (K Bietenhard), Genève, Hôpitaux universitaires (M Roffi), Glarus, Kantonsspital (W. Wojtyna), Grenchen, Spital (R Schönenberger), Grosshöchstetten, Bezirksspital (C Simonin), Heiden, Kantonales Spital (R Waldburger), Herisau, Kantonales Spital (M Schmidli), Horgen, See Spital (B Federspiel), Interlaken, Spital (EM Weiss), Jegenstorf, Spital (H Marty), Kreuzlingen, Herzzentrum Bodensee (K Weber), La Chaux-de-Fonds, Hôpital (H Zender), Lachen, Regionalspital (I Poepping), Langnau im Emmental, Regionalspital (A Hugi), Laufenburg, Gesundheitszentrum Fricktal (E Koltai), Lausanne, Centre hospitalier universitaire vaudois (JF Iglesias), Lugano, Cardiocentro Ticino (G Pedrazzini), Luzern, Luzerner Kantonsspital (P Erne, Luzern, 1997–2013, presently at St. Anna, Luzern, 2014- F. Cuculi), Männedorf, Kreisspital (T Heimes), Martigny, Hôpital régional (B Jordan), Mendrisio, Ospedale regionale (A Pagnamenta), Meyrin, Hôpital de la Tour (P Urban), Monthey, Hôpital du Chablais (P Feraud), Montreux, Hôpital de Zone (E Beretta), Moutier, Hôpital du Jura bernois (C Stettler), Münsingen, Spital (F Repond), Münsterlingen, Kantonsspital (F Widmer), Muri, Kreisspital für das Freiamt (C Heimgartner), Nyon, Group. Hosp. Ouest lémanique (R Polikar), Olten, Kantonsspital (S Bassetti), Rheinfelden, Gesundheitszentrum Fricktal (HU Iselin), Rorschach, Spital (M Giger), Samedan, Spital Oberengadin (P Egger), Sarnen, Kantonsspital Obwalden (T Kaeslin), Schaffhausen, Kantonsspital (A Fischer), Schlieren, Spital Limmattal (T Herren), Schwyz, Spital (P Eichhorn), Scuol, Ospidal d'Engiadina Bassa (C Neumeier/G Flury), Sion, Hôpital du Valais (G Girod), Solothurn, Bürgerspital (R Vogel), Stans, Kantonsspital Nidwalden (B Niggli), St. Gallen, Kantonsspital (H Rickli), Sursee, Luzerner Kantonsspital (Se-l Yoon, -2013, J Nossen, 2014-), Thun, Spital (U Stoller), Thusis, Krankenhaus (UP Veragut), Uster, Spital (E Bächli), Uznach, Spital Linth (A Weber), Walenstadt, Kantonales Spital (D Schmidt/J Hellermann), Wetzikon, GZO Spital (U Eriksson), Winterthur, Kantonsspital (T Fischer), Wolhusen, Luzener Kantonsspital (M Peter), Zofingen, Spital (S Gasser), Zollikerberg, Spital (R Fatio), Zug, Kantonsspital (M Vogt/D Ramsay), Zürich, Hirslanden Klinik im Park (O Bertel), Zürich, Universitätsspital (M Maggiorini), Zürich, Stadtspital Triemli (F Eberli), Zürich, Stadtspital Waid (S Christen).

Contributors: PE contributed to the conception and design, acquisition of data and critical revision of manuscript for intellectual content. DR contributed to conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data and drafting of the article. BS contributed to analysis and interpretation of data, and a critical revision of the manuscript. OB and PU contributed to acquisition of data and a critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content.

Funding: The AMIS Plus registry is funded by unrestricted grants from the Swiss Heart Foundation and from Abbot AG, Switzerland; AMGEN Switzerland AG, Switzerland; Astra-Zeneca AG, Switzerland; Bayer (Schweiz) AG, Switzerland; Biotronik AG, Switzerland; Bristol-Myers Squibb AG, Switzerland; Daiichi-Sankyo/Lilly AG, Switzerland; Johnson & Johnson AG–Cordis Division, Switzerland; A Menarini AG, Switzerland; Merck Sharp & Dohme-Chibret AG, Switzerland; Medtronic AG, Switzerland; Pfizer AG, Switzerland; SISMedical AG, Switzerland; St. Jude Medical, Switzerland; Takeda Pharma AG, Switzerland; Vascular Medical AG, Switzerland.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The registry was approved by the Supra-Regional Ethics Committee for Clinical Studies, the Swiss Board for Data Security and the all Cantonal Ethics Commissions.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Contributor Information

on behalf of the AMIS Plus Investigators:

P Lessing, F Hess, R Simon, PJ Hangartner, U Hufschmid, B Hornig, R Jeger, S Trummler, S Windecker, T Rueff, P Loretan, C Roethlisberger, D Evéquoz, G Mang, D Ryser, P Müller, R Jecker, W Kistler, A. Droll, S Stäuble, G Freiwald, HP Schmid, JC Stauffer, S Cook, K Bietenhard, M Roffi, W. Wojtyna, R Schönenberger, C Simonin, R Waldburger, M Schmidli, B Federspiel, EM Weiss, H Marty, K Weber, H Zender, I Poepping, A Hugi, E Koltai, JF Iglesias, G Pedrazzini, P Erne, T Heimes, B Jordan, A Pagnamenta, P Urban, P Feraud, E Beretta, C Stettler, F Repond, F Widmer, C Heimgartner, R Polikar, S Bassetti, HU Iselin, M Giger, P Egger, T Kaeslin, A Fischer, T Herren, P Eichhorn, C Neumeier, G Flury, G Girod, R Vogel, B Niggli, H Rickli, J Nossen, U Stoller, UP Veragut, E Bächli, A Weber, D Schmidt, J Hellermann, U Eriksson, T Fischer, M Peter, S Gasser, R Fatio, M Vogt, D Ramsay, O Bertel, M Maggiorini, F Eberli, and S Christen

Collaborators: on behalf of the AMIS Plus Investigators

References

- 1.Radovanovic D, Erne P. AMIS Plus: Swiss registry of acute coronary syndrome. Heart 2010;96:917–21. 10.1136/hrt.2009.192302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Radovanovic D, Nallamothu BK, Seifert B et al. . Temporal trends in treatment of ST-elevation myocardial infarction among men and women in Switzerland between 1997 and 2011. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care 2012;1:183–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Witassek F, Schwenkglenks M, Erne P et al. . Impact of body mass index on mortality in Swiss hospital patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: does an obesity paradox exist? Swiss Med Wkly 2014;144:w13986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL et al. . A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radovanovic D, Seifert B, Urban P et al. . Validity of Charlson Comorbidity Index in patients hospitalised with acute coronary syndrome. Insights from the nationwide AMIS Plus registry 2002–2012. Heart 2014;100:288–94. 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thygesen K, Alpert JP, White HD et al. . Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2007;28:2525–38. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Urban P, Radovanovic D, Erne P et al. . Impact of changing definitions for myocardial infarction: a report from the AMIS registry. Am J Med 2008;121:1065–71. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schoenenberger AW, Radovanovic D, Stauffer JC et al. . Age-related differences in the use of guideline-recommended medical and interventional therapies for acute coronary syndromes: a cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:510–16. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01589.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaarsma T, Beattie JM, Ryder M et al. . Palliative care in heart failure: a position statement from the palliative care workshop of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2009;11:433–43. 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jao GT, Knovich MA, Savage RW et al. . ST-elevation myocardial infarction and myelodysplastic syndrome with acute myeloid leukemia transformation. Tex Heart Inst J 2014;41:234–7. 10.14503/THIJ-12-2905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vastbinder MB, Drost H, Muller EW. [Acute coronary syndrome after chemotherapy]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2014;158:A6940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fenning S, Woolcock R, Haga K et al. . Identifying acute coronary syndrome patients approaching end-of-life. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e35536 10.1371/journal.pone.0035536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]