Abstract

Objectives

To examine variation in source of information about sexual matters by sociodemographic factors, and associations with sexual behaviours and outcomes.

Design

Cross-sectional probability sample survey.

Setting

British general population.

Participants

3408 men and women, aged 17–24 years, interviewed from 2010–2012 for third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles.

Main outcome measures

Main source of information (school, a parent, other); age and circumstances of first heterosexual intercourse; unsafe sex and distress about sex in past year; experience of sexually transmitted infection (STI) diagnoses, non-volitional sex or abortion (women only) ever.

Results

Citing school was associated with younger age, higher educational level and having lived with both parents. Citing a parent was associated, in women, with lower educational level and having lived with one parent. Relative to other sources, citing school was associated with older age at first sex (adjusted HR 0.73 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.83) men, 0.73 (0.65 to 0.82) women), lower likelihood of unsafe sex (adjusted OR 0.58 (0.44 to 0.77) men, 0.69 (0.52 to 0.91) women) and previous STI diagnosis (0.55 (0.33 to 0.91) men, 0.58 (0.43 to 0.80) women) and, in women, with lower likelihood of lack of sexual competence at first sex; and experience of non-volitional sex, abortion and distress about sex. Citing a parent was associated with lower likelihood of unsafe sex (0.53 (0.28 to 1.00) men; 0.69 (0.48 to 0.99) women) and, in women, previous STI diagnosis.

Conclusions

Gaining information mainly from school was associated with lower reporting of a range of negative sexual health outcomes, particularly among women. Gaining information mainly from a parent was associated with some of these, but fewer cited parents as a primary source. The findings emphasise the benefit of school and parents providing information about sexual matters and argue for a stronger focus on the needs of men.

Keywords: sex eduction, first intercourse, sexual health, cross-sectional survey

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The size and nature of the sample which was selected using probability sampling and so is broadly representative of the British population.

The range of demographic and sexual health factors included in the survey that allow examination of how learning about sex varies by markers social inequality, and examination of associations between sources of information and a broader range of sexual health factors than has been investigated before.

Although the sample reflects the wider British population, in terms of demographic characteristics, it is possible that individuals who agree to take part in a sexual behaviour survey may differ from those who do not.

As an observational, cross-sectional study, we are not able to infer causality or for some outcomes, temporality.

Recall of the experience of learning about sexual matters may be recast with time, though we limited our analysis to individuals aged 17–24 years in order to minimise the potential bias associated with this.

Introduction

Over recent decades, school lessons have risen in prominence as the main source of information about sexual matters for both boys and girls in Britain.1 Although guidance exists,2 3 there is no statutory programme of study for sex and relationship education (SRE) beyond that included in the National Curriculum Sciencei 2 and there are concerns about variations in the content and quality of provision.4

Disparities in the provision of SRE may be a mediating factor in social inequalities observed in sexual health.5 Earlier first intercourse (before 16 years)—a known risk factor for subsequent negative sexual health outcomes—occurs more commonly among those of lower educational level and lower socioeconomic status.6 Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) disproportionately affect those living in more deprived areas7 and certain ethnic minority groups;8 among women, unplanned pregnancies are associated with lower educational levels9 and experience of non-volitional sex with living in more deprived areas.10

Evidence suggests that school-based sex education delays the onset of sexual activity, and increases condom and contraceptive use among those already sexually active.11–13 Opponents of school SRE tend to focus on the argument that teaching young people about sexual matters should be the responsibility of parents.14 However, few young people cite a parent as a source of information about sex1 and the evidence of a positive relationship between provision of sex education by parents and sexual behaviour and sexual health outcomes is mixed.15–17

Existing research has mainly focused on whether school SRE or parental communication about sex improves biomedical aspects of sexual health11 and thus, reflects the framing of sexual health predominantly in terms of the prevention of adverse sexual health outcomes, such as STIs and unintended conceptions. Pleas have, however, been made for the adoption of a broader concept of sexual health, one that includes outcomes relating to the quality and consensuality of sexual experience, not only as risk factors for outcomes such as STIs and unintended conception, but as important ends in themselves.18

The National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal) is a large and comprehensive probability sample survey of the British population. Findings from the first survey, conducted in 1990–1991,19 20 and the second, in 1999–2001,21–24 have been extensively used to inform sexual and reproductive health policy in Britain.25–27 We use data from the third survey (Natsal-3), in 2010–2012, to explore how sources of information about sexual matters vary by sociodemographic factors; we examine associations between these sources and a wider range of sexual health outcomes than has previously been explored.

Methods

Natsal-3 is a multistage, clustered and stratified probability sample survey of 15 162 men and women aged 16–74 years, resident in Britain. Postcode sectors were primary sampling units; addresses within them were selected at the second stage and one eligible adult was randomly selected at the final stage. To allow detailed exploration of behaviours in the age group at highest risk of certain sexual health outcomes, individuals aged 16–34 were oversampled. Addresses were randomly allocated to either the core sample (in which all individuals aged 16–74 were eligible) or one of two boost samples (boost 1, in which one person aged 16–34 years was selected or boost 2, in which one person aged 16–29 years was selected). The data was weighted to adjust for the unequal probabilities of selection and non-response. Participants were interviewed between September 2010 and August 2012 using computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI), including a computer-assisted self-interview for the more sensitive questions. The response rate was 57.7% for the whole sample, 64.8% for boost 1 and 67.3% for boost 2. Further details of the methods are described elsewhere.28

Questions relating to learning about sex were asked face-to-face in the CAPI section of the questionnaire (available at natsal.ac.uk). Participants were asked, “When you were growing up, in which of the ways listed on this card did you learn about sexual matters?” and “From which did you learn the most?” In response to the latter, they were requested to select one main source. In this paper, we categorised main source of sex education as: school lessons, provision by a parent and ‘other’ sources (which included first boyfriend/girlfriend/sexual partner, peers, siblings, internet sources, pornography, media sources, health professionals and other). All analyses were restricted to those aged 17–24 years at interview (1509 men and 1899 women). Participants aged 16 years were excluded as they could not be ascribed an educational level.

We examined the associations between a range of sociodemographic factors and main source of information about sexual matters by gender, including: age at interview; educational level; religiosity (a combined variable of religion considered ‘very’ or ‘fairly’ important and attendance at religious services at least once every two weeks); family structure (whether lived with both, one or neither natural parent(s) ‘more or less continuously’ until age 14); area-level deprivation (measured using the Index of Multiple Deprivation, a multidimensional measure combining income, employment, health, education, access to housing and services, crime and living environment29); type of school attended (mixed or single sex); and country of residence (England, Scotland or Wales).

We then examined associations between the main source of information about sexual matters, and key sexual behaviours and outcomes. These included: first heterosexual intercourse before age 16 years; lack of sexual competence at first heterosexual intercourse (defined as having not met the following self-reported four criteria: both partners ‘equally willing’, use of reliable contraception, autonomy of decision—not due to peer pressure, drunkenness or drugs—and occurrence at the perceived ‘right time’22); unsafe sex in the past year (defined as no condom used at the first occasion of sex with a new partner in the past year); distress about sex life in the past year (based on agreement with the statement: “I feel distressed or worried about my sex life”); and ever had an experience of STI diagnosis, non-volitional sex and for women, abortion. A composite variable of ‘overall sexual health’ was constructed and participants were coded as having good overall sexual health if they did not report distress or worry about sex life in the past year, or ever having had experience of an STI diagnosis, non-volitional sex or (for women only) abortion.

We performed all analyses using the survey commands in Stata V.13.1,30 which account for the weighting, clustering and stratification of the Natsal-3 data. We assessed the association between sociodemographic factors and the primary source of information among participants, aged 17–24 years, using univariate logistic regressions. We used survival analysis methods to estimate the distribution of age at first heterosexual intercourse by primary source of information about sexual matters, censoring those who had not yet had sex at their age at interview. We conducted proportional hazards regression to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) adjusting for year of birth, educational level and family structure to represent the effect of primary source of information on the rate of first heterosexual intercourse.

We examined the associations between reporting school lessons, a parent or an ‘other’ main source of information, and sexual behaviours and sexual health outcomes in multivariable logistic regression. In the multivariable analysis, we ran two models which adjusted for those sociodemographic variables found to be significantly associated with main source of sex education in our univariate analysis. In the first, we included all participants aged 17–24 years and adjusted for age, educational level and family structure. In the second, we restricted the analysis to sexually experienced individuals aged 17–24 years and adjusted for educational level, family structure, age at first intercourse and number of years sexually active. The latter approach was taken to assess the association between main source of information and sexual health outcomes independently of age at first sex; this informally represents the ‘direct effect’ of source of sex education on outcomes aside from any effect mediated through age at first intercourse.

Results

Main source of information and demographic factors

Overall, similar proportions of men and women reported lessons at school as their main source of information about sexual matters (37.5% (34.8% to 40.2%) and 39.5% (37.0% to 42.0%), respectively). Considerably fewer participants cited a parent and here there was a gender difference; the proportion of women doing so being twice that of men (14.6% (12.9% to 16.4%) and 7.3% (5.9% to 9.0%), respectively). The remainder—just over half of men (55.3% (52.4% to 58.1%)) and just under half of women (46.0% (43.4% to 48.5%))—reported their main source as being other than school or a parent (table 1).

Table 1.

Main source of information about sexual matters by sociodemographic factors, men and women

| Other* |

School |

A parent |

Denominators‡ | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Per cent | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | p Value† | Per cent | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | p Value† | Per cent | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | p Value† | ||

| All men, 17–24 years old | 55.3 | (52.4 to 58.1) | – | – | – | 37.5 | (34.8 to 40.2) | – | – | – | 7.3 | (5.9 to 9.0) | – | – | – | 1509, 1108 |

| Age at interview | 0.0041 | 0.0001 | 0.0610 | |||||||||||||

| 17–20 | 51.0 | (47.1 to 55.0) | 1.00 | 43.1 | (39.2 to 47.0) | 1.00 | 5.9 | (4.5 to 7.8) | 1.00 | 825, 564 | ||||||

| 21–24 | 59.7 | (55.4 to 63.8) | 1.42 | (1.12 to 1.80) | 31.7 | (28.0 to 35.6) | 0.61 | (0.48 to 0.78) | 8.7 | (6.4 to 11.6) | 1.51 | (0.98 to 2.32) | 684, 544 | |||

| Academic qualifications | 0.0031 | 0.0037 | 0.1919 | |||||||||||||

| Studying for/attained further academic qualifications | 51.7 | (48.1 to 55.3) | 1.00 | 41.5 | (38.1 to 44.9) | 1.00 | 6.9 | (5.3 to 8.9) | 1.00 | 957, 716 | ||||||

| Academic qualifications typically gained at age 16 | 59.1 | (53.5 to 64.4) | 1.35 | (1.03 to 1.77) | 33.0 | (28.2 to 38.2) | 0.69 | (0.53 to 0.91) | 8.0 | (5.2 to 12.1) | 1.18 | (0.69 to 2.00) | 416, 285 | |||

| No academic qualifications | 72.3 | (59.4 to 82.3) | 2.44 | (1.35 to 4.41) | 24.5 | (14.7 to 37.8) | 0.46 | (0.24 to 0.87) | 3.2 | (1.3 to 7.9) | 0.45 | (0.17 to 1.22) | 96, 71 | |||

| Religion important and practiced regularly | 0.8036 | 0.3190 | 0.2022 | |||||||||||||

| No | 55.4 | (52.4 to 58.3) | 1.00 | 37.1 | (34.3 to 39.9) | 1.00 | 7.6 | (6.1 to 9.4) | 1.00 | 1391, 1013 | ||||||

| Yes | 54.1 | (44.5 to 63.5) | 0.95 | (0.64 to 1.42) | 41.9 | (32.9 to 51.5) | 1.22 | (0.82 to 1.83) | 4.0 | (1.5 to 10.4) | 0.51 | (0.18 to 1.44) | 118, 94 | |||

| Family background until age 14 | 0.0200 | 0.0241 | 0.2003 | |||||||||||||

| Lived with both natural parents | 53.7 | (50.3 to 57.1) | 1.00 | 39.4 | (36.3 to 42.7) | 1.00 | 6.8 | (5.3 to 8.8) | 1.00 | 1032, 799 | ||||||

| Lived with one natural parent | 57.5 | (52.2 to 62.6) | 1.17 | (0.91 to 1.49) | 33.4 | (28.7 to 38.3) | 0.77 | (0.60 to 0.98) | 9.2 | (6.2 to 13.3) | 1.37 | (0.84 to 2.24) | 436, 283 | |||

| Lived with neither | 78.2 | (60.2 to 89.5) | 3.09 | (1.34 to 7.13) | 21.8 | (10.5 to 39.8) | 0.43 | (0.19 to 0.99) | 0.0 | – | NA | – | 41, 26 | |||

| Region | 0.7919 | 0.8044 | 0.2040 | |||||||||||||

| England | 55.2 | (52.1 to 58.2) | 1.00 | 37.7 | (34.8 to 40.7) | 1.00 | 7.1 | (5.6 to 9.0) | 1.00 | 1300, 954 | ||||||

| Wales | 52.8 | (42.4 to 62.8) | 0.91 | (0.59 to 1.39) | 34.6 | (26.4 to 43.9) | 0.88 | (0.58 to 1.31) | 12.6 | (6.3 to 23.8) | 1.89 | (0.85 to 4.19) | 90, 59 | |||

| Scotland | 57.7 | (47.4 to 67.4) | 1.11 | (0.72 to 1.70) | 36.8 | (27.9 to 46.7) | 0.96 | (0.63 to 1.47) | 5.5 | (2.7 to 10.8) | 0.76 | (0.35 to 1.64) | 119, 95 | |||

| Quintiles of multiple deprivation | 0.4910 | 0.8631 | 0.3730 | |||||||||||||

| 1 (least deprived) | 52.1 | (45.0 to 59.2) | 1.00 | 40.6 | (33.8 to 47.7) | 1.00 | 7.3 | (4.1 to 12.7) | 1.00 | 269, 190 | ||||||

| 2 | 54.8 | (48.7 to 60.8) | 1.11 | (0.76 to 1.64) | 36.6 | (30.7 to 42.9) | 0.84 | (0.56 to 1.27) | 8.6 | (5.4 to 13.4) | 1.19 | (0.55 to 2.61) | 287, 212 | |||

| 3 | 51.6 | (44.9 to 58.2) | 0.98 | (0.67 to 1.43) | 38.7 | (32.5 to 45.3) | 0.93 | (0.62 to 1.37) | 9.7 | (6.4 to 14.4) | 1.37 | (0.64 to 2.91) | 279, 197 | |||

| 4 | 57.9 | (51.5 to 64.0) | 1.26 | (0.86 to 1.86) | 36.0 | (30.0 to 42.4) | 0.82 | (0.55 to 1.23) | 6.1 | (3.7 to 9.9) | 0.83 | (0.37 to 1.85) | 324, 260 | |||

| 5 (most deprived) | 58.3 | (52.2 to 64.1) | 1.28 | (0.88 to 1.87) | 36.4 | (31.1 to 42.1) | 0.84 | (0.58 to 1.22) | 5.3 | (3.1 to 8.8) | 0.71 | (0.31 to 1.61) | 350, 248 | |||

| Last school attended | 0.7647 | 0.5731 | 0.6364 | |||||||||||||

| Mixed school | 55.1 | (52.1 to 58.1) | 1.00 | 37.7 | (34.9 to 40.6) | 1.00 | 7.2 | (5.7 to 8.9) | 1.00 | 1387, 1015 | ||||||

| Single sex school | 56.7 | (46.3 to 66.5) | 1.07 | (0.70 to 1.64) | 34.8 | (25.8 to 45.0) | 0.88 | (0.57 to 1.37) | 8.5 | (4.2 to 16.3) | 1.20 | (0.56 to 2.59) | 121, 93 | |||

| All women, 17–24 years old | 46.0 | (43.4 to 48.5) | – | – | – | 39.5 | (37.0 to 42.0) | – | – | – | 14.6 | (12.9 to 16.4) | – | – | – | 1899, 1088 |

| Age at interview | 0.0041 | 0.0052 | 0.8286 | |||||||||||||

| 17–20 | 42.2 | (38.8 to 45.7) | 1.00 | 43.0 | (39.6 to 46.5) | 1.00 | 14.7 | (12.5 to 17.3) | 1.00 | 968, 531 | ||||||

| 21–24 | 49.5 | (45.9 to 53.2) | 1.34 | (1.10 to 1.64) | 36.1 | (32.7 to 39.6) | 0.75 | (0.61 to 0.92) | 14.4 | (12.1 to 17.0) | 0.97 | (0.74 to 1.28) | 931, 557 | |||

| Academic qualifications | 0.7822 | 0.0628 | 0.0307 | |||||||||||||

| Studying for/attained further academic qualifications | 45.6 | (42.6 to 48.7) | 1.00 | 40.6 | (37.6 to 43.7) | 1.00 | 13.7 | (11.7 to 16.1) | 1.00 | 1199, 720 | ||||||

| Academic qualifications typically gained at age 16 | 44.1 | (39.3 to 48.9) | 0.94 | (0.75 to 1.18) | 40.4 | (35.6 to 45.4) | 0.99 | (0.78 to 1.26) | 15.6 | (12.5 to 19.1) | 1.16 | (0.84 to 1.59) | 518, 266 | |||

| No academic qualifications | 47.3 | (38.1 to 56.7) | 1.07 | (0.73 to 1.57) | 29.5 | (21.8 to 38.6) | 0.61 | (0.41 to 0.92) | 23.2 | (16.0 to 32.4) | 1.90 | (1.17 to 3.08) | 133, 64 | |||

| Religion important and practiced regularly | 0.8944 | 0.8546 | 0.6811 | |||||||||||||

| No | 46.0 | (43.4 to 48.6) | 1.00 | 39.6 | (37.0 to 42.2) | 1.00 | 14.4 | (12.7 to 16.3) | 1.00 | 1757, 991 | ||||||

| Yes | 45.3 | (35.7 to 55.3) | 0.97 | (0.65 to 1.46) | 38.7 | (30.1 to 48.1) | 0.96 | (0.65 to 1.43) | 16.0 | (9.8 to 25.0) | 1.13 | (0.63 to 2.02) | 139, 96 | |||

| Family background until age 14 | 0.9069 | 0.0360 | 0.0003 | |||||||||||||

| Lived with both natural parents | 46.3 | (43.0 to 49.6) | 1.00 | 41.6 | (38.5 to 44.8) | 1.00 | 12.1 | (10.2 to 14.2) | 1.00 | 1163, 709 | ||||||

| Lived with one natural parent | 45.1 | (41.0 to 49.4) | 0.95 | (0.77 to 1.18) | 35.1 | (31.0 to 39.3) | 0.76 | (0.61 to 0.95) | 19.8 | (16.6 to 23.4) | 1.79 | (1.35 to 2.38) | 676, 353 | |||

| Lived with neither | 44.9 | (31.1 to 59.6) | 0.95 | (0.53 to 1.69) | 44.5 | (30.8 to 59.0) | 1.12 | (0.63 to 2.00) | 10.6 | (4.5 to 23.2) | 0.86 | (0.35 to 2.13) | 59, 24 | |||

| Region | 0.8625 | 0.2827 | 0.2689 | |||||||||||||

| England | 45.8 | (43.0 to 48.7) | 1.00 | 39.8 | (37.1 to 42.5) | 1.00 | 14.4 | (12.6 to 16.4) | 1.00 | 1605, 938 | ||||||

| Wales | 48.7 | (38.2 to 59.3) | 1.12 | (0.73 to 1.73) | 31.6 | (22.5 to 42.3) | 0.70 | (0.44 to 1.12) | 19.7 | (13.2 to 28.4) | 1.46 | (0.90 to 2.39) | 114, 56 | |||

| Scotland | 45.5 | (39.2 to 51.9) | 0.98 | (0.74 to 1.30) | 41.4 | (34.0 to 49.2) | 1.07 | (0.77 to 1.49) | 13.2 | (8.6 to 19.5) | 0.90 | (0.55 to 1.47) | 180, 93 | |||

| Quintiles of multiple deprivation | 0.3180 | 0.8963 | 0.4657 | |||||||||||||

| 1 (least deprived) | 42.1 | (36.4 to 48.0) | 1.00 | 40.8 | (35.1 to 46.7) | 1.00 | 17.1 | (13.4 to 21.7) | 1.00 | 319, 182 | ||||||

| 2 | 50.5 | (44.7 to 56.3) | 1.40 | (1.01 to 1.94) | 37.4 | (31.9 to 43.3) | 0.87 | (0.62 to 1.21) | 12.1 | (8.7 to 16.5) | 0.66 | (0.42 to 1.06) | 329, 185 | |||

| 3 | 45.1 | (39.1 to 51.1) | 1.13 | (0.80 to 1.60) | 39.3 | (33.6 to 45.3) | 0.94 | (0.66 to 1.33) | 15.7 | (11.9 to 20.3) | 0.90 | (0.59 to 1.37) | 357, 217 | |||

| 4 | 45.0 | (39.5 to 50.5) | 1.12 | (0.81 to 1.56) | 41.1 | (35.6 to 46.8) | 1.01 | (0.72 to 1.42) | 13.9 | (10.6 to 18.1) | 0.78 | (0.51 to 1.20) | 422, 250 | |||

| 5 (most deprived) | 47.1 | (41.8 to 52.5) | 1.23 | (0.89 to 1.69) | 38.7 | (33.5 to 44.2) | 0.92 | (0.66 to 1.28) | 14.1 | (10.8 to 18.2) | 0.80 | (0.52 to 1.21) | 472, 253 | |||

| Last school attended | 0.1859 | 0.5724 | 0.2410 | |||||||||||||

| Mixed school | 45.2 | (42.4 to 48.0) | 1.00 | 39.9 | (37.2 to 42.6) | 1.00 | 15.0 | (13.2 to 16.9) | 1.00 | 1692, 954 | ||||||

| Single sex school | 51.1 | (42.9 to 59.3) | 1.27 | (0.89 to 1.81) | 37.3 | (29.4 to 45.9) | 0.90 | (0.61 to 1.31) | 11.6 | (7.6 to 17.4) | 0.75 | (0.46 to 1.22) | 203, 132 | |||

*Includes first boyfriend/girlfriend/sexual partner, peers, siblings, internet sources, pornography, media sources, health professionals and other.

†χ2 test of heterogeneity.

‡Denominators are unweighted, weighted.

The likelihood of citing school as a main source was higher among those of younger age; men and women aged 21–24 years were less likely to report school compared with those aged 17–20 years (table 1). It was also higher among men and women studying for or who had achieved qualifications post 16—and for women among those with qualifications typically gained at 16—as opposed to those with none and among those living with both natural parents as opposed to only one (and for men who lived with neither).

The likelihood of citing a parent as the main source was, in women, higher among those without qualifications compared with those with or likely to obtain them, and among those who lived with one natural parent as opposed to two or neither (table 1).

The likelihood of citing an ‘other’ main source of sex education was higher among those aged 21–24 than those aged 17–20. Among men, it was also higher among those with minimum or no qualifications, and those living with neither natural parent.

Main source of information was not associated with religiosity, area level deprivation, whether the school attended was mixed or single sex, or country of residence (table 1).

Main source of information and sexual behaviour and outcomes

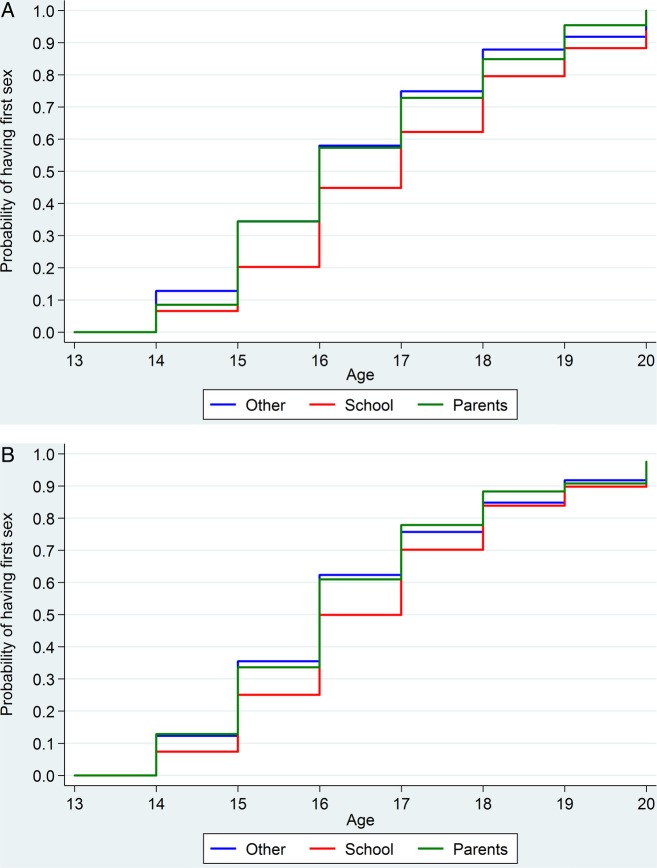

The survival analysis showed that after adjusting for age at interview, education and family structure, participants who reported school as their main source of sexual information had first intercourse at comparatively later ages than did those whose main source was ‘other’ (men who reported lessons from school had a HR of 0.73 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.83) for having first sex relative to men who reported an ‘other’ source, the corresponding ratio for women was 0.73 (0.65 to 0.82); figure 1A, B). No association was found between citing a parent as a main source and age at first intercourse. Note this regression analysis is informal because the assumption of proportional hazards is not met. Specifically, while citing school as main source of sex education is associated with a lower rate of having first sex relative to other sources at younger ages, it is associated with a higher rate at higher ages. By age 20 (more clearly among women) the proportion that has had sex seems unrelated to source of sex education.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of the probability of having first heterosexual sex at, or before, each age by main source of information (A) men aged 17–24 and (B) women aged 17–24.

Men for whom school was the main source of information were less likely than those reporting an ‘other’ main source to have had unsafe sex in the past year (OR 0.58 (95% CI 0.44 to 0.77)) or ever being diagnosed with an STI (0.55 (0.33 to 0.91); table 2). Among sexually experienced men, the association with unsafe sex in the past year remained strong (0.66 (0.49 to 0.89)), but was attenuated for ever being diagnosed with an STI (0.72 (0.43 to 1.22)).

Table 2.

Sexual behaviours and outcomes by main source of information about sexual matters, men and women

| Of all men* |

Of sexually experienced men† |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other |

School |

A parent |

p Value‡ | Other |

School |

A parent |

p Value‡ | |||||||

| First sex before age 16 | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | ||||||||||||

| Per cent (95% CI) | 35.9% | (32.4 to 39.6) | 20.7% | (17.3 to 24.6) | 40.3% | (29.7 to 51.9) | 41.4% | (37.4 to 45.5) | 26.8% | (22.5 to 31.7) | 44.0% | (32.5 to 56.2) | ||

| AOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.47 | (0.35 to 0.64) | 1.12 | (0.69 to 1.82) | 1.00 | 0.50 | (0.37 to 0.69) | 1.04 | (0.63 to 1.73) | ||||

| Denominators | 793, 583 | 548, 399 | 102, 73 | 695, 508 | 411, 309 | 89, 66 | ||||||||

| Lack of sexual competence at first heterosexual sex§ | 0.7668 | 0.8434 | ||||||||||||

| Per cent (95% CI) | 45.0% | (41.0 to 49.1) | 40.5% | (34.6 to 46.6) | 47.6% | (36.2 to 59.2) | 45.0% | (41.0 to 49.1) | 40.5% | (34.6 to 46.6) | 47.6% | (36.2 to 59.2) | ||

| AOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.93 | (0.69 to 1.26) | 1.13 | (0.68 to 1.89) | 1.00 | 0.98 | (0.72 to 1.33) | 1.15 | (0.69 to 1.91) | ||||

| Denominators | 689, 504 | 407, 306 | 89, 66 | 689, 504 | 407, 306 | 89, 66 | ||||||||

| Unsafe sex¶ | 0.0003 | 0.0052 | ||||||||||||

| Per cent (95% CI) | 28.5% | (25.1 to 32.1) | 18.3% | (15.3 to 21.9) | 18.9% | (11.5 to 29.5) | 32.5% | (28.8 to 36.4) | 23.6% | (19.6 to 28.2) | 20.4% | (12.3 to 32.1) | ||

| AOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.58 | (0.44 to 0.77) | 0.53 | (0.28 to 1.00) | 1.00 | 0.66 | (0.49 to 0.89) | 0.49 | (0.25 to 0.95) | ||||

| Denominators | 782, 574 | 554, 403 | 102, 73 | 675, 494 | 406, 305 | 87, 65 | ||||||||

| Ever diagnosed with an STI | 0.0553 | 0.3840 | ||||||||||||

| Per cent (95% CI) | 9.5% | (7.6 to 11.9) | 4.8% | (3.2 to 7.1) | 8.2% | (3.6 to 17.7) | 10.5% | (8.3 to 13.2) | 6.3% | (4.2 to 9.3) | 9.2% | (4.0 to 19.6) | ||

| AOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.55 | (0.33 to 0.91) | 0.65 | (0.24 to 1.75) | 1.00 | 0.72 | (0.43 to 1.22) | 0.65 | (0.23 to 1.85) | ||||

| Denominators | 792, 582 | 560, 407 | 104, 74 | 684, 501 | 410, 308 | 89, 66 | ||||||||

| Non-volitional sex, ever | 0.6915 | 0.9410 | ||||||||||||

| Per cent (95% CI) | 1.0% | (0.5 to 2.1) | 0.7% | (0.2 to 1.9) | 1.5% | (0.3 to 7.0) | 1.2% | (0.6 to 2.5) | 0.9% | (0.3 to 2.5) | 1.7% | (0.3 to 7.8) | ||

| AOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.65 | (0.18 to 2.29) | 1.35 | (0.24 to 7.74) | 1.00 | 0.94 | (0.24 to 3.65) | 1.31 | (0.22 to 7.62) | ||||

| Denominators | 777, 571 | 552, 401 | 103, 73 | 672 ,493 | 405, 304 | 88, 65 | ||||||||

| Distressed/worried about sex life | 0.3971 | 0.6328 | ||||||||||||

| Per cent (95% CI) | 11.1% | (8.9 to 13.9) | 10.8% | (8.2 to 14.0) | 6.2% | (3.1 to 12.1) | 9.6% | (7.4 to 12.3) | 8.2% | (5.8 to 11.4) | 6.2% | (2.9 to 12.4) | ||

| AOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.95 | (0.64 to 1.42) | 0.59 | (0.27 to 1.27) | 1.00 | 0.84 | (0.52 to 1.36) | 0.71 | (0.31 to 1.61) | ||||

| Denominators | 762, 557 | 516, 378 | 102, 73 | 684, 501 | 410, 308 | 89, 66 | ||||||||

| Overall sexual health** | 0.3975 | 0.6780 | ||||||||||||

| Per cent (95% CI) | 80.6% | (77.2 to 83.6) | 84.2% | (80.5 to 87.3) | 83.8% | (74.0 to 90.4) | 81.4% | (78.0 to 84.4) | 85.6% | (81.7 to 88.9) | 82.8% | (72.1 to 90.0) | ||

| AOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.22 | (0.88 to 1.70) | 1.34 | (0.71 to 2.55) | 1.00 | 1.18 | (0.81 to 1.72) | 1.17 | (0.59 to 2.32) | ||||

| Denominators | 745, 544 | 511, 374 | 101, 73 | 670, 490 | 405, 304 | 88, 65 | ||||||||

| Of all women* |

Of sexually experienced women† |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other |

School |

A parent |

p Value‡ | Other |

School |

A parent |

p Value‡ | |||||||

| First sex before age 16 | 0.0001 | 0.0032 | ||||||||||||

| Per cent (95% CI) | 33.4% | (30.0 to 37.0) | 23.5% | (20.3 to 27.0) | 33.6% | (27.8 to 40.0) | 37.5% | (33.7–41.3) | 30.0% | (26.1–34.3) | 39.7% | (33.0–46.7) | ||

| AOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.56 | (0.43 to 0.72) | 0.84 | (0.62 to 1.14) | 1.00 | 0.63 | (0.48–0.82) | 0.92 | (0.66–1.27) | ||||

| Denominators | 823, 462 | 706, 408 | 273, 151 | 748, 414 | 565, 321 | 235, 127 | ||||||||

| Lack of sexual competence at first heterosexual sex§ | 0.0021 | 0.0131 | ||||||||||||

| Per cent (95% CI) | 56.3% | (52.3 to 60.1) | 47.1% | (42.6 to 51.6) | 52.5% | (45.5 to 59.4) | 56.3% | (52.3–60.1) | 47.1% | (42.6–51.6) | 52.5% | (45.5–59.4) | ||

| AOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.65 | (0.51 to 0.83) | 0.75 | (0.54 to 1.06) | 1.00 | 0.70 | (0.54–0.90) | 0.75 | (0.53–1.05) | ||||

| Denominators | 741, 409 | 564, 320 | 234, 127 | 741, 409 | 564, 320 | 234, 127 | ||||||||

| Unsafe sex¶ | 0.0141 | 0.1437 | ||||||||||||

| Per cent (95% CI) | 26.1% | (22.9 to 29.5) | 20.4% | (17.3 to 23.9) | 21.4% | (16.5 to 27.3) | 29.9% | (26.4–33.7) | 26.3% | (22.4–30.5) | 25.2% | (19.5–31.9) | ||

| AOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.69 | (0.52 to 0.91) | 0.69 | (0.48 to 0.99) | 1.00 | 0.81 | (0.60–1.08) | 0.71 | (0.48–1.04) | ||||

| Denominators | 828, 465 | 714, 411 | 278, 155 | 736, 405 | 555, 315 | 234, 127 | ||||||||

| Ever had an abortion | 0.1014 | 0.2692 | ||||||||||||

| Per cent (95% CI) | 10.5% | (8.4 to 13.0) | 6.9% | (5.2 to 9.0) | 7.7% | (5.1 to 11.4) | 12.1% | (9.8–14.9) | 8.5% | (6.4–11.2) | 9.3% | (6.2–13.7) | ||

| AOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.70 | (0.47 to 1.04) | 0.64 | (0.38 to 1.08) | 1.00 | 0.84 | (0.56–1.27) | 0.65 | (0.38–1.11) | ||||

| Denominators | 833, 470 | 723, 417 | 279, 155 | 740, 409 | 560, 319 | 235, 127 | ||||||||

| Ever diagnosed with an STI | 0.0004 | 0.0110 | ||||||||||||

| Per cent (95% CI) | 20.8% | (17.8 to 24.1) | 12.5% | (10.0 to 15.5) | 13.8% | (10.1 to 18.4) | 23.8% | (20.5–27.3) | 16.2% | (13.0–20.0) | 16.6% | (12.3–22.2) | ||

| AOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.58 | (0.43 to 0.80) | 0.54 | (0.36 to 0.82) | 1.00 | 0.71 | (0.50–0.99) | 0.57 | (0.38–0.86) | ||||

| Denominators | 833, 468 | 717, 414 | 277, 154 | 740, 407 | 557, 317 | 234, 127 | ||||||||

| Non-volitional sex, ever | 0.0320 | 0.1325 | ||||||||||||

| Per cent (95% CI) | 9.1% | (7.2 to 11.4) | 5.9% | (4.3 to 8.1) | 6.3% | (3.9 to 10.1) | 10.5% | (8.3–13.2) | 7.5% | (5.4–10.3) | 7.2% | (4.4–11.6) | ||

| AOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.61 | (0.40 to 0.94) | 0.58 | (0.32 to 1.03) | 1.00 | 0.76 | (0.49–1.18) | 0.55 | (0.30–1.04) | ||||

| Denominators | 813, 457 | 699, 404 | 272, 151 | 721, 397 | 538, 307 | 229, 124 | ||||||||

| Distressed/worried about sex life | 0.1757 | 0.0762 | ||||||||||||

| Per cent (95% CI) | 11.4% | (9.1 to 14.2) | 8.6% | (6.5 to 11.4) | 11.3% | (7.5 to 16.8) | 11.2% | (8.7–14.3) | 7.3% | (5.2–10.0) | 10.4% | (6.5–16.3) | ||

| AOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 0.70 | (0.47 to 1.03) | 1.00 | (0.58 to 1.70) | 1.00 | 0.60 | (0.38–0.94) | 0.94 | (0.52–1.68) | ||||

| Denominators | 812, 453 | 666, 380 | 264, 145 | 739, 407 | 557, 317 | 234, 127 | ||||||||

| Overall sexual health†† | 0.0001 | 0.0024 | ||||||||||||

| Per cent (95% CI) | 60.1% | (56.3 to 63.8) | 71.1% | (66.9 to 74.9) | 68.5% | (61.9 to 74.4) | 57.3% | (53.3–61.2) | 68.5% | (63.9–72.8) | 66.5% | (59.4–72.9) | ||

| AOR (95% CI) | 1.00 | 1.64 | (1.28 to 2.10) | 1.59 | (1.12 to 2.26) | 1.00 | 1.50 | (1.14–1.96) | 1.64 | (1.13–2.38) | ||||

| Denominators | 789, 440 | 641, 367 | 256, 141 | 717, 393 | 534, 306 | 228, 124 | ||||||||

Denominators are unweighted, weighted.

*OR is adjusted for age (continuous) educational level and family structure (binary variable of living with both natural parents/living with one/no parent).

†OR is adjusted for educational level, family structure, age at first sex (continuous) and years sexually active (continuous), except for “First sex before age 16” which is adjusted for educational level, family structure and age (continuous).

‡χ2 test of heterogeneity.

§Not met the following four criteria: both partners equally willing, use of reliable contraception, autonomy of decision, and that it happened at the ‘right time’. Excludes those who have not experienced heterosexual sex.

¶No condom used at the first occasion of sex with a new partner in the past year.

**Composite of: not experiencing non-volitional sex or STI diagnosis, and lack of distress about sex life in the past year.

††Composite of: not experiencing non-volitional sex, STI diagnosis, or abortion and lack of distress about sex life in the past year.

AOR, adjusted OR; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Men citing a parent as their main source were less likely to have reported unsafe sex in the past year than those citing an ‘other’ main source (0.53 (0.28 to 1.00))—an association that remained in the analysis of sexually active men (0.49 (0.25 to 0.95)—but were no less likely to have been diagnosed with an STI (table 2).

Among women, reporting school as the main source of information was associated with a decreased likelihood of all the negative sexual health indicators examined in the multivariable analysis (table 2). Among sexually active women, the associations with lack of sexual competence at first intercourse (0.70 (0.54 to 0.90)), ever experiencing STI diagnosis (0.71 (0.50 to 0.99)), distress about sex life in the past year (0.60 (0.38 to 0.94)) and good ‘overall sexual health’ (1.50 (1.14–1.96)) remained, while those with unsafe sex in the past year (0.81 (0.60 to 1.08)), ever had an experience of abortion (0.84 (0.56 to 1.27)) and non-volitional sex (0.76 (0.49 to 1.18)) were in the same direction but were attenuated.

Among women, reporting a parent as the main source of information was also associated with a decreased likelihood of all the sexual health factors examined in the multivariable analysis, with the exception of sex before age 16 years and distress about sex life (table 2). The adjusted ORs were similar to those among women reporting school as a main source, though the CIs were slightly wider reflecting the smaller number of women reporting a parent. Among sexually active women citing a parent, the associations remained largely unchanged: sexual competence at first intercourse (0.75 (0.53 to 1.05)); unsafe sex (0.71 (0.48 to 1.04)); ever had an abortion (0.65 (0.38 to 1.11)); ever had an STI (0.57 (0.38 to 0.86)); non-volitional sex (0.55 (0.30 to 1.04)) and good ‘overall sexual health’ (1.59 (1.12 to 2.26)).

Discussion

Highlights

We found differences in the reporting of a range of sexual health indicators according to the main source of information about sexual matters. Receipt of information mainly from school, as opposed to other sources, was associated with lower reporting of a wide range of sexual health risk behaviours and outcomes. Receipt of information from a parent, as opposed to other sources, was associated with lower reporting of some but not all of these. For both school and parents, the range of outcomes where positive associations were found was wider in women than men.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The strength of this study lies in the size and nature of the sample, which was selected using probability sampling and so is broadly representative of the British population. Another strength is the range of demographic and sexual health factors included in the survey that allow examination of both how learning about sex varies by markers social inequality and the associations between sources of information and a broader range of sexual health factors than has been investigated hitherto.

Several limitations, however, should be considered. Although the sample reflects the wider British population in terms of demographic characteristics, it is possible that individuals who agree to take part in a survey of this nature may differ from those who do not. Since this was an observational, cross-sectional study, we are not able to infer causality or for some outcomes, temporality. Relatedly, we cannot know whether some antecedent factor may predispose young people to seek higher academic achievement and to privilege school-based information. It is also important to note that the recall of the experience of learning about sexual matters may be recast with time, though we limited our analysis to individuals aged 17–24 years in order to minimise the potential bias associated with this. We must also acknowledge that a possible consequence of singling out one main source of sex education for the purpose of analysis is that the nuances of learning about sexual matters from multiple sources are lost.

Strengths and weaknesses with respect to other studies and important differences in results

Our finding that school as the main source of sex education is associated with later age at first sex is consistent with that from other observational and intervention studies.11 13 31 As may be expected, associations with lower reporting of some of the sexual health factors we explored (for men, ever had diagnosis of an STI; and for women, unsafe sex in the past year and ever had experience of abortion or non-volitional sex) appear to be operating through later age at first intercourse. More surprising—and in contrast to research that has taken a similar approach elsewhere31—is the number of associations that remain after adjusting for age at first sex, years sexually active, educational level and family structure (for men a lower likelihood of having unsafe sex in the past year, and for women a lower likelihood of first sex being defined as lacking sexual competence, ever had diagnosis of an STI and distress about sex the past year), which suggests that school-based sex education is associated with additional benefit independent of that relating to later age at first sex.

As noted above, it has been suggested that variations in the provision of SRE may be a mediating factor in social inequalities observed in sexual health.5 Unlike researchers from the USA,32 we did not find area (neighbourhood) level deprivation to be associated with reporting school as a main source of sex education, though neighbourhood-level deprivation at the time of interview may have been different from that when growing up. We did, however, find school as a main source to be associated with educational level. Participants who had no qualifications (and among men only those typically gained at 16 years) were less likely to report school as their main source. Multiple, possibly inter-related, factors may help to explain this association. The Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted) found a strong correlation between a school's scores for performance generally and SRE, specifically.4 So it could be argued that ‘good’ SRE is an indicator of a ‘good’ school; one that better fosters the educational and personal and social development of young people. It has also been suggested that young people with lower psychosocial well-being do less well at school and are less engaged,33 traits which are both associated with increased risk of negative sexual health outcomes.6 9 34 Those ‘missing out’ on school-based SRE may be less of a concern in policy terms if they instead report a parent; indeed among women, those with no academic qualifications were more likely to do so, but this was not the case for men.

Studies exploring the relationship between parental communication and age at first sex have produced somewhat equivocal findings.16 17 Some have suggested that parents may initiate or intensify communication about sexual matters once they think their children have become sexually active.35 This may explain the absence of an association between parents as a main source of information and later age at first intercourse. We did, however, see positive associations with other sexual health outcomes, notably safe sex. There is evidence that wider aspects of parenting, including good communication generally, parental monitoring and family ‘connectedness’ are positively associated with sexual health outcomes16 and that parents may wield an effect through their influence on risk behaviours, such as alcohol use16 17 and/or by moderating peer pressure.35 As such, an exclusive focus on communication about sex may serve to underestimate the role of parents. However, the complex interplay of individual and family-related factors and their relative contribution to sexual health outcomes is poorly understood.

Meaning of the study, possible explanations and implications for clinicians and policy makers

We found learning about sex mainly from school to be associated with the ‘stalwarts’ of sex education (age at first intercourse, safe sex and STIs) in men and women. Our finding that receipt of information mainly from school was associated with a wider number of sexual behaviours and outcomes among women than men has implications for policy and practice, and may be seen to warrant greater attention to the broader framing of sexual health in sex education, particularly for men. It has been suggested that sex education is overly focused on ‘girls’ issues’ (the so called ‘three Ps’: periods, pills and pregnancy) (Emmersen L, personal communication) and it is important that “issues such as relationships, consent, contraception and infections, are considered from a young man's perspective.”36 According to our study, men are also less likely than women to report a parent as a main source of sex education and as with school, doing so is associated with fewer positive outcomes than in women.

Unanswered questions and future research

More nuanced research into the content, context and mode of delivery of sex education by both school and parents is needed. Also needed is longitudinal research to explore temporality in relation to learning about sex and sexual trajectories along with further intervention research, specifically exploring how best to meet the needs of young men and support parents in communicating about sexual matters in a timely manner. Multifaceted research exploring the relative contribution of different factors at play (including those related to community, school, family, peers and partners) and how they interact to mediate and/or moderate risk would be an important contribution to our understanding about how young people learn about sex and navigate early sexual experiences.

Conclusion

Our findings emphasise the benefit of school and parents providing information about sexual matters and argue for a stronger focus on the needs of men. Parents, in particular, need to recognise their role, which is important not just in relaying information about sexual matters but also, more generally, in moderating risks faced by young people.

Acknowledgments

Natsal-3 is a collaboration between University College London (London, UK), the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (London, UK), NatCen Social Research, Public Health England (formerly the Health Protection Agency), and the University of Manchester (Manchester, UK). The authors thank the study participants, the team of interviewers from NatCen Social Research, and operations and computing staff from NatCen Social Research.

Footnotes

Contributors: WM, CT, KGJ, JD, RL, KW, AMJ and CHM conceived this article. WM wrote the first draft, with further contributions from KGJ, CT, SC, AJC, CHM, MP, RL, JD, KRM, NF, PS, AMJ and KW. KGJ did the statistical analysis with support from CHM, AJC and CT. KW, AMJ, WM, CHM and PS—initial applicants on Natsal-3— wrote the study protocol and obtained funding. KW, AMJ, WM, CHM, CT, SC, KRM, JD, NF, and PS designed the Natsal-3 questionnaire, applied for ethics approval and undertook piloting of the questionnaire. CT, SC, RL and CHM managed data. All authors interpreted data, reviewed successive drafts and approved the final version of the article.

Funding: The study was supported by grants from the Medical Research Council (G0701757) and the Wellcome Trust (084840), with contributions from the Economic and Social Research Council and Department of Health. KGJ is funded by the National Institute for Health Research School for Public Health Research. NF is supported by a National Institute for Health Research Academic Clinical Lectureship.

Competing interests: AMJ has been a Governor of the Wellcome Trust since 2011.

Ethics approval: Natsal-3 was granted ethical approval by the Oxfordshire Research Ethics Committee A (reference: 09/H0604/27).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The Natsal-3 data are due to be archived with the UK Data Archive in 2015, before then, researchers are welcome to contact the Natsal-3 team to seek advance access to the corresponding data and are directed to the Natsal website for further information (http://www.natsal.ac.uk).

At the time of writing, a Government Education Select Committee was holding an inquiry into Personal, Social, Health and Economic Education (PSHE), and SRE in schools addressing: whether PSHE ought to be statutory; whether the current accountability system is sufficient to ensure that schools focus on PSHE; the overall provision of SRE in schools and the quality of its teaching; whether recent steps to supplement the guidance on teaching about sex and relationships are adequate; and how the effectiveness of SRE should be measured [http://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/commons-select/education-committee/inquiries/parliament-2010/pshe-and-sre-in-schools].

References

- 1. Tanton C, Jones KG, Macdowall W, et al. Patterns and trends in sources of information about sex among young people in Britain: evidence from three National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007834. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department for Education and Employment. Sex and Relationship Education Guidance. Crown Copyright, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blake S, Emmerson L, Hayman J et al. Sex and Relationship Education (SRE) for the 21st Century: Supplementary Advice to the Sex and Relationship Education Guidance DfEE (0116/2000). Brook, PSHE Association and Sex Education Forum, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted). Not yet good enough: personal, social, health and economic education in schools. Crown Copyright, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mclaughlin M, Thompson K, Parahoo K et al. Inequalities in the provision of sexual health information for young people. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2007;33:99–105. 10.1783/147118907780254178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mercer CH, Tanton C, Prah P et al. Changes in sexual attitudes and lifestyles in Britain through the life course and over time: findings from the National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal). Lancet 2013;382:1781–94. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62035-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sonnenberg P, Clifton S, Beddows S et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and uptake of interventions for sexually transmitted infections in Britain: findings from the National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal). Lancet 2013;382:1795–806. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61947-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Low N, Sterne JAC, Barlow D. Inequalities in rates of gonorrhoea and chlamydia between black ethnic groups in south east London: cross sectional study. Sex Transm Infect 2001;77:15–20. 10.1136/sti.77.1.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wellings K, Jones KG, Mercer CH et al. The prevalence of unplanned pregnancy and associated factors in Britain: findings from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). Lancet 2013;382:1807–16. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62071-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macdowall W, Gibson LJ, Tanton C et al. Lifetime prevalence, associated factors, and circumstances of non-volitional sex in women and men in Britain: findings from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). Lancet 2013;382:1845–55. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62300-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirby DB, Laris B, Rolleri LA. Sex and HIV education programs: their impact on sexual behaviors of young people throughout the world. J Adolesc Health 2007;40:206–17. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.11.143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Downing J, Jones L, Cook PA, et al. HIV prevention: a review of reviews assessing the effectiveness of interventions to reduce the risk of sexual transmission. Liverpool: Liverpool John Moores University, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.UNESCO. International Technical Guidance on Sexuality Education. Paris: UNESCO, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14. http://www.parliament.uk. [26/11/2014]. Commons Select Committee, Personal, Social, Health and Economic education and Sex and Relationships Education in schools, written evidence. http://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/commons-select/education-committee/inquiries/parliament-2010/pshe-and-sre-in-schools-inquiry/inquiry-publications-page-/

- 15.Wight D, Williamson L, Henderson M. Parental influences on young people's sexual behaviour: a longitudinal analysis. J Adolesc 2006;29:473–94. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Markham CM, Lormand D, Gloppen KM et al. Connectedness as a predictor of sexual and reproductive health outcomes for youth. J Adolesc Health 2010;46(3 Suppl):S23–41. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller BC, Benson B, Galbraith KA. Family relationships and adolescent pregnancy risk: a research synthesis. Dev Rev 2001;21:1–38. 10.1006/drev.2000.0513 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wellings K, Johnson AM. Framing sexual health research: adopting a broader perspective. Lancet 2013;382:1759–62. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62378-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson A, Wadsworth J, Wellings K et al. The national survey of sexual attitudes and lifestyles. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wellings K, Field J, Johnson A et al. Sexual behaviour in Britain. London: Penguin, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson AM, Mercer CH, Erens B et al. Sexual behaviour in Britain: partnerships, practices, and HIV risk behaviours. Lancet 2001;358:1835–42. 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06883-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wellings K, Nanchahal K, Macdowall W et al. Sexual behaviour in Britain: early heterosexual experience. Lancet 2001;358: 1843–50. 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06885-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fenton KA, Korovessis C, Johnson AM et al. Sexual behaviour in Britain: reported sexually transmitted infections and prevalent genital Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Lancet 2001;358:1851–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06886-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fenton K, Mercer C, McManus S et al. Ethnic variations in sexual behaviour in Great Britain and risk of sexually transmitted infections: a probability survey. Lancet 2005;365:1246–55. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74813-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Department of Health. The national strategy for sexual health and HIV. London: Department of Health, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scottish Executive. Respect and responsibility: strategy and action plan for improving sexual health. Edinburgh: Scottish Government, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.The National Assembly for Wales. A Strategic Framework for Promoting Sexual Health in Wales 2001.

- 28.Erens B, Phelps A, Clifton S et al. Methodology of the third British National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). Sex Transm Infect 2014;90:84–9. 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Payne RA, Abel GA. UK indices of multiple deprivation—a way to make comparisons across constituent countries easier. Health statistics quarterly/Office for National Statistics; 2012;22–37. [Google Scholar]

- 30.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindberg LD, Maddow-Zimet I. Consequences of sex education on teen and young adult sexual behaviors and outcomes. J Adolesc Health 2012;51:332–8. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kraft JM, Kulkarni A, Hsia J et al. Sex education and adolescent sexual behavior: do community characteristics matter? Contraception 2012;86:276–80. 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gutman LM, Vorhaus J. The impact of pupil behaviour and wellbeing on educational outcomes. London: DfE, 2012.

- 34.Bonell C, Allen E, Strange V et al. The effect of dislike of school on risk of teenage pregnancy: testing of hypotheses using longitudinal data from a randomised trial of sex education. J Epidemiol Community Health 2005;59:223–30. 10.1136/jech.2004.023374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van de Bongardt D, de Graaf H, Reitz E et al. Parents as moderators of longitudinal associations between sexual peer norms and Dutch adolescents’ sexual initiation and intention. J Adolesc Health 2014;55:388–93. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Department of Health. A Framework for Sexual Health Improvement in England. London: Crown Copyright, 2013. [Google Scholar]