Abstract

Objective

While newcomers are often disproportionately concentrated in disadvantaged areas, little attention is given to the effects of immigrants’ postimmigration context on their mental health and care use. Intersectionality theory suggests that understanding the full impact of disadvantage requires considering the effects of interacting factors. This study assessed the inter-relationship between recent immigration status, living in deprived areas and service use for non-psychotic mental health disorders.

Study design

Matched population-based cross-sectional study.

Setting

Ontario, Canada, where healthcare use data for 1999–2012 were linked to immigration data and area-based material deprivation scores.

Participants

Immigrants in urban Ontario, and their age-matched and sex-matched long-term residents (a group of Canadian-born or long-term immigrants, n=501 417 pairs).

Primary and secondary outcome measures

For immigrants and matched long-term residents, contact with primary care, psychiatric care and hospital care (emergency department visits or inpatient admissions) for non-psychotic mental health disorders was followed for 5 years and examined using conditional logistic regression models. Intersectionality was investigated by including a material deprivation quintile by immigrant status (immigrant vs long-term resident) interaction.

Results

Recent immigrants in urban Ontario were more likely than long-term residents to live in most deprived quintiles (immigrants—males: 22.8%, females: 22.3%; long-term residents—both sexes: 13.1%, p<0.001). Living in more deprived circumstances was associated with greater use of mental health services, but increases were smaller for immigrants than for long-term residents. Immigrants used less mental health services than long-term residents.

Conclusions

This study adds to existing research by suggesting that immigrant status and deprivation have a combined effect on recent immigrants’ care use for non-psychotic mental health disorders. In settings where immigrants are over-represented in deprived areas, policymakers focused on increasing immigrants’ access of mental health services should broadly address the influence of structural and cultural factors beyond the disadvantage.

Keywords: MENTAL HEALTH, PSYCHIATRY, PRIMARY CARE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The main strength of this population-based study is that it used linked administrative databases to examine the inter-relationship between disadvantage, immigration and service use. Results indicate that while disadvantage and immigration each appear to affect mental health service use separately, they also have a combined effect that is complex. This is the first investigation of the relationship between deprivation and mental healthcare use for immigrants who are often over-represented in deprived areas.

The study is limited by the absence of information on mental health needs which limited the authors’ conclusions regarding potential drivers of these findings.

Another limitation is that non-insured mental health supports were not included.

Introduction

People are moving across the globe in larger numbers, faster and farther than at any other time in history.1 The postimmigration experience can have implications for newcomers’ mental health since it has been linked to distinct stressors, such as leaving behind family, creating new social networks and finding sustained appropriate employment.2–4 Mental health disorders are among the most common and disabling health conditions worldwide. Two such disorders, anxiety disorders and unipolar depression, are estimated to affect 61.5 million and 30.3 million people, respectively.5 Consequently, the first few years after arrival are an important time for the host country to support newcomers’ access to needed supports, including mental healthcare.6 Despite this importance, there are concerns that many countries are ill-prepared to deal with changing demographics, and suggestions that knowledge gaps and shortcomings in immigrant resettlement policy could jeopardise immigrants’ mental health.1 3

Immigrants face a myriad of stressors that can affect postimmigration mental health and access to care (eg, limited fluency in host country language, unfamiliarity with available services, beliefs about illness and treatment that diverge from the host culture, etc). Economic disadvantage is at the forefront of these challenges as recent immigrants are internationally often over-represented in deprived areas. This has been shown using varied indicators of deprivation, including low income7–10 (USA11–13) and ability to afford amenities like food (Germany, Luxembourg).14–16 In Canada, there are reports of an increasing earnings gap between recent immigrants and non-immigrants over the past two decades.17 Economic disadvantage can also serve as a barrier to accessing mental healthcare.7–13

Findings on the relationship between disadvantage and mental health service use for non-psychotic mental health disorders have not been entirely consistent even when studies were conducted in publically funded systems, where patients experience fewer financial barriers to the use of mental health services.18 Studies on outpatient mental healthcare that measured deprivation at the individual level or the neighbourhood level have had mixed findings, reporting negative associations19–21 or no association.22 23 For inpatient mental healthcare, studies on individual-level and area-level measures of socioeconomic deprivation mostly showed a positive relationship with likelihood of admission.19 24 25 However, one dated study reported no such relationship.26 None of these studies specifically examined immigrants contributing to a persisting knowledge gap surrounding the relationship between immigration status, disadvantage and mental health service use.

Examining the postimmigration settlement context can be complicated since being an immigrant and living in poverty are both significant social roles that can interact to influence mental health and mental healthcare use. Intersectionality theory27 28 argues that social disadvantage arises from intersecting social statuses (eg, recent newcomer, poverty), and that understanding the impact of social disadvantage should consider the combined effects of interacting factors rather than the effects of separate individual factors. In understanding immigrant service use postmigration, this theory supports the value of assessing the combined effect of two important factors which can inform the policy that aims to increase access to care for immigrants. The aim of the present study is to assess the relationship between recent immigration, material deprivation (MD) and mental health service use.

Methods

This population-based cross-sectional study used administrative data accessed through comprehensive research agreements between Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) and Ontario's Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, and between ICES and Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC). Data sets were linked using unique, encoded identifiers and analysed at ICES. Analyses were performed using SAS V.9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA).

This study was conducted in Ontario, a Canadian province with a single payer universal healthcare plan which insures outpatient physician services and services delivered in hospital settings without user fees, copayments or deductibles for all permanent residents.29 Population-level health and immigration databases were linked to examine mental health service use patterns among immigrants and a comparator group of long-term residents (LTRs) that consists largely of non-immigrants.

Data sources

Several databases were accessed for this study and were linked in an anonymous fashion using encrypted individual identifiers. The Ontario portion of the CIC database contains individual-level demographic information recorded on the date of issue for Ontario's permanent residents who landed from 1985 to 2010. In this study it helped identify immigrants who arrived from 1999 to 2007. The Registered Persons Database (RPDB) is Ontario's healthcare registry, and includes birth date, sex and postal code of all Ontario residents eligible for the province's single and universal Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP). An initial validation study30 of the linkage between the Ontario CIC and RPDB reported that 84.4% of records were successfully linked. The OHIP claims database from 1999 to 2012 was the source of outpatient visit data and the OHIP specialty code used to distinguish outpatient visits as either primary care or psychiatry visits. Hospital admissions were determined from the Canadian Institute for Health Information's Discharge Abstract Database (1981–present) and the Ontario Mental Health Reporting System (2005/2006–present). Emergency department (ED) visits were determined using the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System from 2002 onwards. ED-use data for 1999–2001 was ascertained from the location variable in OHIP claims data. Residence data from the 1996 and 2001 censuses, and Statistics Canada's Postal Code Conversion File were used to link patients’ first postal code after arrival (see supplementary appendix B) to urban or rural residences, and to link individuals to MD scores.

Study populations

The eligible study sample included 1 618 672 immigrants listed in the Ontario CIC who arrived in Ontario from 1 April 1999 to 31 March 2007. The cut-off date of 1999 was used because the MD dimension was first calculated for dissemination areas (DAs) in 2001 and we linked immigrants to the measured MD calculated for the DA 2 years prior to the immigrants’ arrival or the 2 years following their arrival. The cut-off arrival date of 31 March 2007 allowed for a full 5-year follow-up period since the latest full health services records were available for 31 March 2012.

Further inclusion criteria for the immigrant sample were: adult age (18–105 years, excluded 25.5%), living in Ontario for entire 5-year follow-up (eg, no proof of having moved or died), and having at least one contact with the healthcare system during that time (excluded 5.1%), admission in the economic/business class, family reunification or refugee class (ie, not in the ‘other’ admission class, excluded 2.4%), and having immigrated from their country of birth (excluded 13.3%) since immigrants exposed to multiple immigration and resettlement experiences may be different from recent newcomers who immigrated from their birth country. Restricting the study to individuals living in urban areas led to the exclusion of 1.3% of immigrants who lived in rural areas. Subsequently we excluded 3.8% of immigrants whose neighbourhood postal codes could not be linked to census data since they could not receive an MD score. Finally, for reasons noted above, the sample was further restricted to immigrants who arrived between 1999 and 2007. This led to an immigrant sample of 545 073.

LTRs were Canadian-born or foreign-born individuals who settled in Ontario prior to 1985. LTRs were listed in the RPDB but were not in the CIC. However, immigrants who did not declare an intention to settle in Ontario were not included in the Ontario CIC. To avoid misclassifying these immigrants as LTRs, we excluded individuals absent from the CIC who became eligible for OHIP after 1999.

From these immigrant and LTR pools, further eligibility criteria were applied: being OHIP insured, adult (aged 18–105 years), and residing in a metropolitan area with data on MD score at the DA level. Of the 545 073 immigrants, 92.7% were matched on birth date (date, month and year) and sex to LTRs, creating a final sample of 505 417 immigrant–LTR matched pairs.

Variables

Outcomes

Outcomes were any outpatient visits to general practitioners or to psychiatrists, and any inpatient use for non-psychotic mental health disorders between 1999 and 2012. For each person, service use was followed for 5 years. For immigrants and their matched LTRs, it was measured over the same 5 years that followed the start of the immigrant's eligibility for OHIP. For immigrants eligibility for OHIP, the coverage begins after 3 months of residence in Ontario. For refugees this period is highly variable, but generally longer. The method for identifying non-psychotic visits to general practitioners (using codes in supplementary appendix A) has shown a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 97%.31 32 Mental health hospital visits (a composite of ED visits or hospital admissions) were defined as those for which any diagnosis fields were related to non-psychotic mental disorders based on International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes (see supplementary appendix A). Short-term inpatient admissions (ie, 72 h or shorter) were excluded because limited classification information did not permit identification of non-psychotic disorders.

Independent variables

Material deprivation

Among the area-level social measures33 34 is the MD dimension in the Ontario Marginalization Index (ON-MARG)35–37 that reflects marginalisation and shows area inequalities. It is composed of six indicators from census data (%): individual’s aged 20 years and over without a high school graduation; families who are lone parent families; individuals who are receiving government transfer payments; individuals 15 years and over who are unemployed; individuals living below the low income cut-off, which is a Statistics Canada defined measure that is adjusted for community size; and households living in dwellings in need of major repair. Postal codes from the 2001 and 2006 censuses (see supplementary appendix B) were used to derive individuals’ postal codes, their DA and the associated MD scores.

Since MD is an area-based index, individual health service use records were linked to the MD index associated with the individual's census DA of residence. MD scores from 2001 and 2006 were used for immigrants with landing dates from 1999 to 2003 and from 2004 to 2007, respectively. Each DA included an average of 944.5 and 1257.4 residents in 2001 and 2006, respectively. MD scores were then transformed into quintiles—higher scores/quintiles represent more deprivation.

Immigrant status

Persons were classified either as immigrants or LTRs (long-term immigrants or Canadian-born individuals) based on the CIC and RPDB.

Interaction term

To test for intersectionality, an interaction term was developed that represented the combined effect of MD quintile and immigrant status (immigrants vs LTR) on mental health service use.

Immigration characteristics

Descriptive information on immigrants (birth date, sex, source country, birth country, admission class, education level at landing, language spoken and period of arrival) was obtained from the CIC.

Sex

Analyses were stratified by sex as females are more likely than males to experience non-psychotic mental health disorders and more likely to use mental health services.38–44 In Canada, females are less likely than males to be employed and earn less.45

Analysis

Since MD is an area variable, we examined the appropriateness of a multilevel analysis by running a random intercept generalised linear mixed model to account for variation in the response variables attributable to persons living in the same area. In the multilevel generalised linear mixed model, random variation among DAs was not significant, so the random intercept was dropped from the model. The 17 879 DAs represented 1 059 295 individuals, with an average of 59.2 residents per DA (centiles—25th: 26 people, 50th: 40 people, 75th: 65 people; maximum: 1553 people).

Demographic characteristics were calculated for immigrants across MD quintiles and for LTRs by sex. Student t tests and χ2 tested if the differences across immigrants in different MD quintiles were statistically significant.

The likelihood of use of three services for non-psychotic mental health disorders (primary care, psychiatry care and hospital care) was examined using conditional logistic regression models.46 For each outcome, three models were run: (1) with MD quintile as the only predictor, (2) with the interaction term (MD quintile by immigrant status) and with sex as a covariate and (3) sex stratified with the interaction term. Significance testing of the interaction term determined if the relationship between MD and health service use was different for immigrants compared with LTRs for each sex. From each model we obtained estimates of expected number of users per service per 100 individuals from the least squares–means. Testing determined if estimates for adjacent MD quintiles were significantly different from each other. The inverse-link transformation was used to obtain event probabilities from the presented estimates of the linear predictors on the logit scale. To visually represent the relationship between MD and mental healthcare use for immigrants and LTRs the estimates were plotted on line graphs. Characteristics from the CIC that applied to immigrants could not be included in the adjusted models since there was no comparable data for LTRs.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses addressed two issues. The first pertained to how MD quintile score was determined since immigrants tend to be transient, especially after arrival.13 In the main analysis, MD quintile was determined from individuals’ first postal codes over the 5-year outcome window. In the sensitivity analysis, the postal code closest to the end of the individual's 5-year outcome window was used instead. Models were rerun with the MD quintile derived from the last postal code.

The second pertained to the definition of mental health hospitalisations. In the main analysis, a hospital admission or ED visit was included if any diagnosis in the admission record (admissions may have up to 25 diagnoses and ED visits may have up to 10 diagnoses) was a mental health diagnosis. In the sensitivity analysis, these visits were included only if a mental health diagnosis was the most responsible diagnosis. The most responsible diagnosis is determined from the primary care provider's documentation, and refers to the diagnosis or condition identified as being most responsible for the patient's stay in hospital according to the WHO’s Rules and Guidelines for Mortality and Morbidity Coding.47

Results

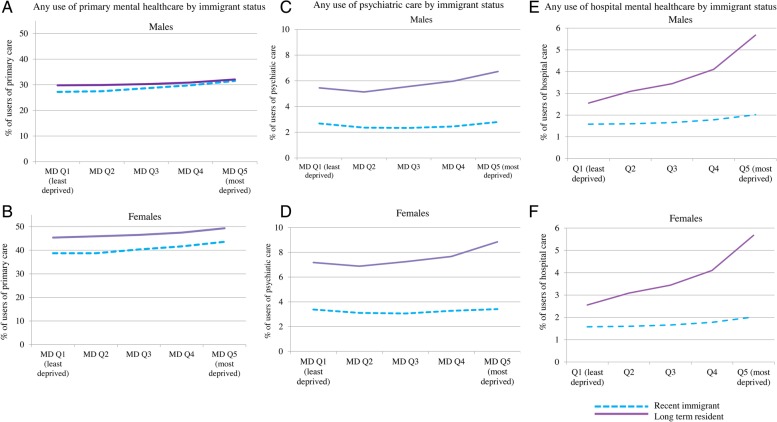

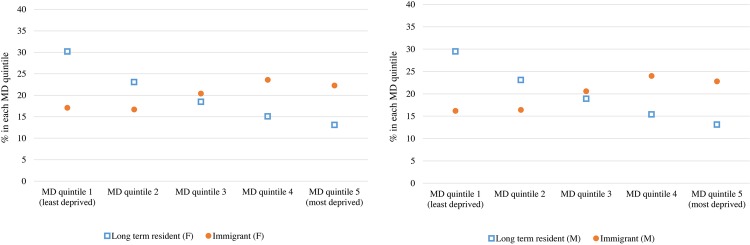

Overall, a higher proportion of immigrants than LTRs lived in areas in the most deprived quintile (immigrants: 22.8% of males and 22.3% of females; LTRs: 13.1% of males, 13.1% of females, p values <0.0001, see figure 1A, B). Immigrants in more deprived MD quintiles were more likely to be younger and admitted as refugees compared with immigrants in less deprived quintiles (table 1). Conversely, they were less likely to be admitted in the economic class, to have greater than high school education and to speak English or French (females only).

Figure 1.

Distribution across material deprivation (MD) quintiles of recent immigrants who arrived in urban Ontario between 1999 and 2007, and their matched long-term residents, by sex (F, female; M, male).

Table 1.

Characteristics for recent immigrants who arrived in urban Ontario between 1999 and 2007 by material deprivation (MD) quintile, and by sex

| MD quintile 1 (least deprived) | MD quintile 2 | MD quintile 3 | MD quintile 4 | MD quintile 5 (most deprived) | Total | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | |||||||

| N (%) | 49 921 (17.1) | 48 800 (16.7) | 59 822 (20.4) | 69 075 (23.6) | 65 145 (22.3) | 292 763 | |

| Age (years) | |||||||

| Mean±SD | 37.50±14.00 | 36.22±13.15 | 35.55±12.42 | 34.88±11.80 | 34.55±11.65 | 35.62±12.56 | <0.001 |

| Age (years, categories) | |||||||

| 18–34 | 26 539 (15.8) | 27 420 (16.3) | 34 430 (20.5) | 40 886 (24.3) | 38 658 (23) | 26 539 (15.8) | <0.001 |

| 35–49 | 13 936 (16.5) | 13 786 (16.3) | 17 232 (20.4) | 20 226 (23.9) | 19 323 (22.9) | 13 936 (16.5) | |

| 50–64 | 6158 (21.8) | 5210 (18.4) | 5842 (20.6) | 5795 (20.5) | 5294 (18.7) | 6158 (21.8) | |

| 65+ | 3288 (27.3) | 2384 (19.8) | 2318 (19.3) | 2168 (18) | 1870 (15.5) | 3288 (27.3) | |

| Admission class | |||||||

| Economic | 24 156 (48.4%) | 22 994 (47.1%) | 27 872 (46.6%) | 31 903 (46.2%) | 25 677 (39.4%) | 132 602 (45.3%) | <0.001 |

| Family | 23 485 (47.0%) | 22 428 (46.0%) | 25 894 (43.3%) | 28 075 (40.6%) | 25 898 (39.8%) | 125 780 (43.0%) | |

| Refugee | 2280 (4.6%) | 3378 (6.9%) | 6056 (10.1%) | 9097 (13.2%) | 13 570 (20.8%) | 34 381 (11.7%) | |

| Period of arrival | |||||||

| 1998–2002 | 23 846 (47.8%) | 23 272 (47.7%) | 27 183 (45.4%) | 32 928 (47.7%) | 31 054 (47.7%) | 138 283 (47.2%) | <0.001 |

| 2003–2007 | 26 075 (52.2%) | 25 528 (52.3%) | 32 639 (54.6%) | 36 147 (52.3%) | 34 091 (52.3%) | 154 480 (52.8%) | |

| Education level | |||||||

| None | 1709 (3.4%) | 1940 (4.0%) | 2479 (4.1%) | 2794 (4.0%) | 3317 (5.1%) | 12 239 (4.2%) | <0.001 |

| High school | 14 822 (29.7%) | 15 498 (31.8%) | 19 833 (33.2%) | 24 208 (35.0%) | 27 492 (42.2%) | 101 853 (34.8%) | |

| More than high school | 33 390 (66.9%) | 31 362 (64.3%) | 37 510 (62.7%) | 42 073 (60.9%) | 34 336 (52.7%) | 178 671 (61.0%) | |

| Language | |||||||

| English/French | 33 530 (67.2%) | 30 316 (62.1%) | 35 218 (58.9%) | 39 861 (57.7%) | 38 434 (59.0%) | 177 359 (60.6%) | <0.001 |

| Neither | 16 391 (32.8%) | 18 484 (37.9%) | 24 604 (41.1%) | 29 214 (42.3%) | 26 711 (41.0%) | 115 404 (39.4%) | <0.001 |

| Males | |||||||

| N (%) | 40 892 (16.2) | 41 273 (16.4) | 51 949 (20.6) | 60 622 (24) | 57 574 (22.8) | 252 310 | |

| Age (years) | |||||||

| Age (years, categories) | |||||||

| Mean±SD | 38.09±13.21 | 37.00±12.48 | 36.37±11.72 | 35.86±11.08 | 35.33±10.91 | 36.39±11.81 | <0.001 |

| 18–34 | 19 740 (15.15) | 21 026 (16.14) | 27 093 (20.8) | 31 726 (24.35) | 30 688 (23.56) | 130 273 (100) | <0.001 |

| 35–49 | 14 171 (15.63) | 14 238 (15.71) | 18 398 (20.29) | 22 496 (24.82) | 21 351 (23.55) | 90 654 (100) | |

| 50–64 | 4392 (20.0) | 4073 (18.54) | 4574 (20.83) | 4684 (21.33) | 4240 (19.31) | 21 963 (100) | |

| 65+ | 2589 (27.48) | 1936 (20.55) | 1884 (20.0) | 1716 (18.22) | 1295 (13.75) | 9420 (100) | |

| Admission class | |||||||

| Economic | 24 773 (60.6%) | 24 455 (59.3%) | 30 475 (58.7%) | 35 160 (58.0%) | 28 929 (50.2%) | 143 792 (57.0%) | <0.001 |

| Family | 13 594 (33.2%) | 13 057 (31.6%) | 14 789 (28.5%) | 15 600 (25.7%) | 14 591 (25.3%) | 71 631 (28.4%) | |

| Refugee | 2525 (6.2%) | 3761 (9.1%) | 6685 (12.9%) | 9862 (16.3%) | 14 054 (24.4%) | 36 887 (14.6%) | |

| Period of arrival | |||||||

| 1998–2002 | 20 534 (50.2%) | 20 773 (50.3%) | 25 054 (48.2%) | 30 215 (49.8%) | 29 088 (50.5%) | 125 664 (49.8%) | <0.001 |

| 2003–2007 | 20 358 (49.8%) | 20 500 (49.7%) | 26 895 (51.8%) | 30 407 (50.2%) | 28 486 (49.5%) | 126 646 (50.2%) | |

| Education level | |||||||

| None | 675 (1.7%) | 816 (2.0%) | 1085 (2.1%) | 1139 (1.9%) | 1228 (2.1%) | 4943 (2.0%) | <0.001 |

| High school | 9499 (23.2%) | 10 844 (26.3%) | 14 160 (27.3%) | 17 236 (28.4%) | 20 095 (34.9%) | 71 834 (28.5%) | |

| More than high school | 30 718 (75.1%) | 29 613 (71.7%) | 36 704 (70.7%) | 42 247 (69.7%) | 36 251 (63.0%) | 175 533 (69.6%) | |

| Language | |||||||

| English/French | 31 198 (76.3%) | 29 636 (71.8%) | 36 322 (69.9%) | 42 764 (70.5%) | 42 021 (73.0%) | 181 941 (72.1%) | <0.001 |

| Neither | 9694 (23.7%) | 11 637 (28.2%) | 15 627 (30.1%) | 17 858 (29.5%) | 15 553 (27.0%) | 70 369 (27.9%) | |

Area deprivation and mental health service use

For the whole sample, increasing deprivation was associated with increasing use of primary care and hospital care (table 2). For psychiatric care, use was most common by those in the most deprived and least deprived quintiles.

Table 2.

Expected use of three mental health services by MD Q, by immigrant status and sex

| Estimates* for expected use for mental healthcare services by MD Q |

p Values for MD Q comparisons |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Least deprived |

Most deprived |

Less deprived |

More deprived |

Ratio of most deprived to least deprived Q, and p value | ||||||

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q2 vs Q1 | Q3 vs Q2 | Q4 vs Q3 | Q5 vs Q4 | Q5/Q1†, p value | |

| Primary mental healthcare | ||||||||||

| Deprivation as only predictor | ||||||||||

| Whole sample | 36.47 | 36.35 | 36.70 | 37.43 | 39.10 | 0.389‡ | 0.0168 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 1.07, <0.0001 |

| Deprivation, immigrant status, sex as predictors | ||||||||||

| Immigrant | 32.64 | 32.67 | 34.09 | 35.37 | 37.21 | 0.544 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 1.14, <0.0001 |

| LTR§ | 37.38 | 37.71 | 38.18 | 38.99 | 40.61 | 0.079 | 0.028 | 0.0007 | <0.0001 | 1.09, <0.0001 |

| Sex-stratified models that include an immigrant status by MD interaction | ||||||||||

| Immigrant (female) | 38.71 | 38.70 | 40.31 | 41.64 | 43.57 | NS | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 1.13, <0.0001 |

| LTR§ (female) | 45.35 | 45.88 | 46.46 | 47.43 | 49.32 | 0.043 | 0.050 | 0.004 | <0.0001 | 1.09, <0.0001 |

| Immigrant (male) | 27.22 | 27.49 | 28.64 | 29.81 | 31.51 | NS | 0.001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 1.16, <0.0001 |

| LTR§ (male) | 29.81 | 29.92 | 30.27 | 30.87 | 32.08 | NS | NS | NS | 0.001 | 1.08, <0.0001 |

| Psychiatric care | ||||||||||

| Deprivation as only predictor | ||||||||||

| Whole sample | 5.13 | 4.62 | 4.442 | 4.373 | 4.781 | <0.0001 | 0.0018 | 0.424 | <0.0001 | 0.93, <0.0001 |

| Deprivation, immigrant status, sex as predictors | ||||||||||

| Immigrant | 3.00 | 2.71 | 2.67 | 2.84 | 3.07 | 0.0002 | 0.6311 | 0.0108 | 0.0007 | 1.02, 0.3488 |

| LTR§ | 6.27 | 5.97 | 6.35 | 6.76 | 7.73 | 0.0012 | 0.0002 | 0.0005 | <0.0001 | 1.23, <0.0001 |

| Sex-stratified models that include an immigrant status by MD interaction | ||||||||||

| Immigrant (female) | 3.38 | 3.11 | 3.06 | 3.28 | 3.41 | 0.014‡ | NS | 0.024‡ | NS | 1.01, 0.798 |

| LTR§ (female) | 7.18 | 6.88 | 7.24 | 7.67 | 8.85 | 0.032‡ | 0.020 | 0.015‡ | <0.0001 | 1.23, <0.0001 |

| Immigrant (male) | 2.69 | 2.36 | 2.34 | 2.45 | 2.80 | 0.003‡ | NS | NS | 0.000 | 1.04, 0.278 |

| LTR§ (male) | 5.45 | 5.13 | 5.56 | 5.98 | 6.72 | 0.014‡ | 0.003 | 0.011 | <0.0001 | 1.23, <0.0001 |

| Hospital mental healthcare | ||||||||||

| Deprivation as only predictor | ||||||||||

| Whole sample | 1.91 | 2.12 | 2.13 | 2.24 | 2.78 | <0.0001 | 0.7315 | 0.0156 | <0.0001 | 1.46, <0.0001 |

| Deprivation, immigrant status, sex as predictors | ||||||||||

| Immigrant | 1.25 | 1.27 | 1.29 | 1.38 | 1.56 | 0.7706 | 0.6311 | 0.0108 | <0.0001 | 1.25, <0.0001 |

| LTR§ | 2.20 | 2.66 | 30.11 | 3.54 | 4.83 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 2.20, <0.0001 |

| Sex-stratified models that include an immigrant status by MD interaction | ||||||||||

| Immigrant (female) | 1.58 | 1.60 | 1.66 | 1.78 | 2.02 | NS | NS | NS | 0.002 | 1.28, <0.0001 |

| LTR§ (female) | 2.55 | 3.09 | 3.44 | 4.10 | 5.68 | <0.0001 | 0.001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 2.23, <0.0001 |

| Immigrant (male) | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 1.01 | 1.14 | NS | NS | NS | 0.025 | 1.19, 0.005 |

| LTR§ (male) | 1.96 | 2.34 | 2.70 | 3.11 | 4.15 | <0.0001 | 0.000 | 0.001 | <0.0001 | 2.12, <0.0001 |

*Estimates of expected number of users per service per 100 males and per 100 females were obtained from sex-stratified models that included an interaction between MD Q and immigrant status.

†The most deprived Q was compared with the least deprived Q.

‡Estimates in the marked Q is significantly larger than the estimate for the next (more deprived) Q for the same group.

§LTR (Canadian-born or immigrants who arrived in Ontario prior to 1985).

LTR, long-term resident; MD, material deprivation; NS, not significant; Q, quintile.

Immigrant status and mental health service use

For all outcomes, immigrants used less mental healthcare than their matched LTRs. This relationship persisted across all deprivation quintiles with one exception—immigrant and LTR males in the most deprived quintiles were not significantly different from each other (immigrant males: 31.51%; LTR males: 32.08%, p=0.0849, figure 2A, table 2).

Figure 2.

Expected use (%) of primary care, psychiatric care and hospital care for non-psychotic mental health disorders for recent immigrants and long-term residents, by sex. †The material deprivation dimension from the Ontario Marginalization Index (ON-MARG) reflects area marginalization. ‡LTRs were Canadian born or immigrants who arrived in Ontario prior to 1985 (LTRs, long-term residents; MD, material deprivation; Q, quintile).

Intersectional analysis: area deprivation, immigration and mental healthcare use

For each of the sex-stratified models, the interaction between deprivation quintile and immigrant status was significant (all p values <0.001). The positive association between deprivation and mental healthcare use (high deprivation, with high use) observed among LTRs was modified among recent immigrants (high deprivation, with slightly higher use).

For immigrants and LTRs, living in more deprived quintiles was associated with small but mostly significant increases in primary mental health service use. The exception was male LTRs for whom changes in use across MD quintiles were mostly non-significant (table 2, figure 2).

For immigrants, the relationship between deprivation and psychiatric care use was variable across levels of MD. For LTRs living in more deprived quintiles was associated with small increases in use of psychiatric care (table 2, figure 2).

For immigrants and LTRs, expected use of hospital care was higher for people in more deprived quintiles, with much greater increases for LTRs than for immigrants (table 2; figure 2).

Sensitivity analyses

The first sensitivity analysis compared outcomes for MD quintiles based on the individuals’ first and last postal codes during the study window. Although over 60% of immigrants and over 50% of LTRs moved to areas associated with different MD quintiles during the 5-year outcome window (immigrants—males: 62.6%; females: 61.3%; LTRs—males: 51.9%; females: 51.8%), results were substantially the same as the primary analysis (see supplementary appendix C). One small difference was that in the primary analysis, there was no significant difference between persons in the most deprived versus the least deprived quintiles in their likelihood of seeing a psychiatrist, whereas the difference was significant in the sensitivity analysis.

The second sensitivity analysis compared the relationship between deprivation, immigrant status and hospital use, using two different definitions of hospital use. For LTRs, the results were generally the same as the primary analysis—there was increased use by persons in more deprived quintiles. However, for immigrants in the sensitivity analysis there was no clear linear trend of increased use across quintiles and differences between quintiles were mostly non-significant (see supplementary appendix C). In the primary analysis, for immigrants there was increasing trend of greater hospital use by individuals in more deprived areas, although not all differences were significant.

Discussion

This study found that immigrant status and deprivation had a combined effect on immigrants’ mental healthcare use. While for both immigrants and LTRs residence in more deprived quintiles was associated with increased use of primary mental healthcare and hospital mental health services, the increase was smaller for recent immigrants compared with LTRs.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to examine the combined effect of neighbourhood deprivation and immigrant status on mental health service use at the population level. It suggests that policymakers focused on improving health and healthcare of marginalised groups, such as immigrants, should broadly address inter-related social circumstances/roles that can individually or in combination deter use of services by vulnerable groups.

Weaker relationships between MD and health service use by immigrants than LTRs may reflect immigrants’ exposure to unique structural and cultural factors that inhibit help seeking (eg, difficulties identifying available resources, fear of being misunderstood or being discriminated against by practitioners, etc).48–52 In addition, while the MD index is broad and multidimensional, some variables included in this index may not be sensitive indicators of variation in deprivation for immigrants. For example, having more education is generally associated with greater employment income for the general population. However, this relationship is weaker for immigrants who are more commonly underemployed or not employed.53

The observed slight but consistent increases in the likelihood of use of primary mental healthcare by people in more deprived areas depart from the body of literature on various populations that has not shown positive associations between deprivation and primary mental healthcare use. It is, however, consistent with other Canadian studies on general use of healthcare that have found that lower income and education groups were more likely than advantaged groups to contact physicians and hospital services.54–57 If mental health morbidity is greater among those with higher deprivation,19 58–64 present findings may be construed as aligning with recommended care use patterns. Ontario is among the jurisdictions that have made efforts to increase primary care use by more marginalised and disadvantaged groups.65 66

Psychiatric care was distinct from the other forms of care under study because there was no consistent pattern observed between deprivation level and psychiatric care use, suggesting a complex relationship between deprivation and publically insured psychiatric care. This may warrant further attention, particularly if deprivation is a proxy for need,19 58–64 since services do not appear to follow need. Immigrants routinely settle in urban areas, such as Toronto—Ontario's largest urban centre.67 Similarly, psychiatrists tend to be concentrated in this urban region; the ratio of number of psychiatrists to the population in Toronto exceeds the ratio recommended by Canadian Psychiatric Association.68 Even so, present findings suggest immigrants have limited access to psychiatry, accentuating the difference between availability and accessibility of health services.69 This appears to support conclusions in a recent Ontario study68 that the actual availability of psychiatrists in Toronto is much lower than the apparent availability since many psychiatrists care for relatively small number of high-income patients.

Even though living in disadvantaged circumstances have been linked to elevated risk of mental health disorders,19 58–64 immigrants used less of all mental health services than LTRs. Reasons for lower use may relate to disadvantage, other access barriers unique to newcomers or lower need, possibly due to self-selection and/or screening prior to arrival.70 71

Limitations

There were some limitations associated with the data sources used. The absence of information on mental health need, barriers, social support and use of non-insured services limited conclusions regarding potential drivers of these findings. Another data limitation is that the MD index and census derived variables (eg, urban–rural status) are measured once per 5 years and may change over time.

Regarding outcome measures, short-term hospital admissions and non-insured supports, such as Community Health Centres (CHCs), could not be included. While CHCs serve higher proportions of newcomers than other primary care models in Ontario,70 CHCs still only serve small proportions of immigrants (1.4% of recent newcomers). Hence, their exclusion likely did not significantly bias results.72 A related limitation is that mental health service use was only tracked when persons were covered by OHIP. While immigrants receive OHIP coverage after 3 months in Ontario, refugees can only apply for OHIP coverage after their claim has been accepted (generally more than 1 year).73 74 Consequently, refugees’ first years of OHIP coverage often do not immediately follow their arrival.

Since this study exclusively examined service use for non-psychotic disorders, results cannot be extrapolated to psychotic disorders. Since psychotic and non-psychotic disorders are so different (eg, in aetiology, symptom profile, acuity, common pathways to care and prevalence),5 service use for psychotic disorders was beyond the scope of the current work, but may be investigated in future studies.

Finally, this study did not include immigrants absent from the CIC—immigrants who entered Ontario from a different province; refugee claimants who have not been accepted or are appealing; other temporary residents/workers/visitors; or ‘non-status’ residents. Immigrants living in rural areas were also excluded although during the 2000s, only 5–8% of new immigrants to Canada settled in rural areas.67 Present results were not likely to be strongly affected by this limitation given the large sample of immigrants in this study and the smaller relative size of newcomers excluded because they are absent from the CIC75 and live in rural areas.67

In spite of these limitations, this study adds to existing research by examining the effect of a broad measure of MD on recent immigrants, for whom this relationship has not been examined. Linkage of population-based databases allowed for inclusion of a large group of newcomers—almost all immigrants who applied to settle in Ontario over an extended period (1999–2007). In addition, newcomers were matched to a standard comparison group (LTRs) on birth date and sex, which controlled for two important sources of variation. Using data from administrative sources was another strength since it is more objective than survey-derived data that are commonly used for research in this area and are often affected by biases (ie, recall, reporting and selection), and missing information.3 76–79 Finally, usage of an intersectionality lens represents a shift from focusing on direct effects by taking into account multiple facets of individuals and contexts, and multiple effects on outcomes.80

Conclusion

This population-based cross-sectional study considered the inter-relationship between disadvantage and immigration and health service use. Results indicate that while disadvantage and immigration each appear to affect mental health service use separately, they also have a combined effect that is complex. This first investigation of the relationship between MD and healthcare use for non-psychotic mental health disorders among immigrants was conducted in a large Canadian province where immigrants compose over one-quarter of the population and physician-provided services are insured. Consistent with other literature, immigrants were over-represented in deprived areas and used less care. This study added to existing research by suggesting that immigrant status and deprivation had a combined effect on immigrants’ mental healthcare use. Weaker relationships for immigrants provided an indication that their use of mental health services is influenced by factors beyond disadvantage. Policymakers who want to increase immigrants’ access of mental health services should broadly address the influence of structural and cultural factors beyond disadvantage.

Footnotes

Contributors: The project was conceived by AD and RHG. RM assisted AD and RHG with the development of the study design. AD worked under the guidance of RM to conduct the statistical analysis. All authors contributed substantially to the framing of the study, data interpretation and discussion of the implications of this work. AD drafted the manuscript, but all authors made suggestions and approved the final version for publication.

Funding: This study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). RHG and LSS were supported as clinician scientists in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Toronto and at St. Michael's Hospital.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The research protocol was approved by Research Ethics Boards at the University of Toronto and Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Administrative data used for this study could be accessed because of comprehensive research agreements between Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) and Ontario's Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, and between ICES and Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC).

References

- 1.Carballo M, Nerukar A. Migration, refugees, and health risks. Emerg Infect Dis 2001;7:556–60. 10.3201/eid0707.017733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reitmanova S, Gustafson DL. Mental health needs of visible minority immigrants in a small urban center: recommendations for policy makers and service providers. J Immigr Minor Health 2009;11:46–56. 10.1007/s10903-008-9122-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beiser M. The health of immigrants and refugees in Canada. Can J Public Health 2005;96(Suppl 2):S30–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gushulak BD, Pottie K, Roberts JH et al. on behalf of the Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health. Migration and health in Canada: health in the global village. CMAJ 2011;183:E952–8. 10.1503/cmaj.090287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wittchen HU, Jacobi F, Rehm J et al. The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2011;21:655–79. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Improving mental health services for immigrant, refugee, ethno-cultural and racialized groups: issues and options for service improvement. http://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/SiteCollectionDocuments/Key_Documents/en/2010/Issues_Options_FINAL_English%2012Nov09.pdf.

- 7.Newbold B. The short-term health of Canada's new immigrant arrivals: evidence from LSIC. Ethn Health 2009;14:315–36. 10.1080/13557850802609956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durbin A, Lin E, Taylor L et al. First-generation immigrants and hospital admission rates for psychosis and affective disorders: an ecological study in Ontario. Can J Psychiatry 2011;56:418–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palameta B. Low income among immigrants and visible minorities. Catalogue no. 75–001-XIE. Perspectives on labour and income. Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Social Determinants of Health in Canada's Immigrant Population: Results from the National Population Health Survey. Research on immigration and integration in the metropolis. http://mbc.metropolis.net/assets/uploads/files/wp/1998/WP98–20.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams DR. Race, socioeconomic status, and health. The added effects of racism and discrimination. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1999;896:173–88. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08114.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chow JC, Jaffee K, Snowden L. Racial/ethnic disparities in the use of mental health services in poverty areas. Am J Public Health 2003;93:792–7. 10.2105/AJPH.93.5.792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Immigrant integration in low-income urban neighborhoods. Improving economic prospects and strengthening connections for vulnerable families. The Urban Institute. http://www.urban.org/uploadedpdf/411574_immigrant_integration.pdf

- 14. Measuring and accounting for the deprivation gap of Portuguese immigrants in Luxembourg. Working Paper No 2012–33. http://www.ceps.lu/publi_viewer.cfm?tmp=1880.

- 15.Alieva A. Educational inequalities in Europe: performance of students with migratory backgrounds in Luxemborg and Switzerland. International Academic Publishers, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haisken-DeNew J, Sinning M. Social deprivation and exclusion of immigrants in Germany. Rev Income Wealth 2010;56:715–33. 10.1111/j.1475-4991.2010.00417.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Deteriorating Economic Welfare of Immigrants and Possible Causes. Statistics Canada. Catalogue no. 11F0019MIE—No. 222. http://publications.gc.ca/Collection/Statcan/11F0019MIE/11F0019MIE2004222.pdf

- 18.Sareen J, Jagdeo A, Cox BJ et al. Perceived barriers to mental health service utilization in the United States, Ontario, and the Netherlands. Psychiatr Serv 2007;58:357–64. 10.1176/ps.2007.58.3.357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Driessen G, Gunther N, Van Os J. Shared social environment and psychiatric disorder: a multilevel analysis of individual and ecological effects. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1998;33:606–12. 10.1007/s001270050100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houle J, Beaulieu M, Lesperance F et al. Inequities in medical follow-up for depression: a population-based study in montreal. Psychiatr Serv 2010;61:258–63. 10.1176/ps.2010.61.3.258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vasiliadis HM, Lesage A, Adair C et al. Do Canada and the United States differ in prevalence of depression and utilization of services? Psychiatr Serv 2007;58:63–71. 10.1176/ps.2007.58.1.63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parslow RA, Jorm AF. Who uses mental health services in Australia? An analysis of data from the National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2000;34:997–1008. 10.1080/000486700276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alegria M, Bijl RV, Lin E et al. Income differences in persons seeking outpatient treatment for mental disorders: a comparison of the United States with Ontario and The Netherlands. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000;57:383–91. 10.1001/archpsyc.57.4.383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moustgaard H, Joutsenniemi K, Martikainen P. Does hospital admission risk for depression vary across social groups? A population-based register study of 231,629 middle-aged Finns. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2013;49:15–25. 10.1007/s00127-013-0711-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorant V, Kampfl D, Seghers A et al. Socio-economic differences in psychiatric in-patient care. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2003;107:170–7. 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00071.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrison J, Barrow S, Creed F. Social deprivation and psychiatric admission rates among different diagnostic groups. Br J Psychiatry 1995;167:456–62. 10.1192/bjp.167.4.456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Intersectionality in sociology. http://www.socwomen.org/wp-content/uploads/swsfactsheet_intersectionality.pdf.

- 28.Cairney J, Veldhuizen S, Vigod S et al. Exploring the social determinants of mental health service use using intersectionality theory and CART analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health 2014;68:145–50. 10.1136/jech-2013-203120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharfstein SS. Some interesting lessons from Canada. Psychiatr Serv 2006;57:297 10.1176/appi.ps.57.3.297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cernat G, Wall C, Iron K et al. Initial validation of Landed Immigrant Data System (LIDS) with the Registered Person's Database (RPDB) at ICES. Internal ICES Report to Health Canada. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steele LS, Glazier RH, Lin E et al. Using administrative data to measure ambulatory mental health service provision in primary care. Med Care 2004;42:960–5. 10.1097/00005650-200410000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steele LS. Ambulatory mental health service use in an inner city setting: Measurement, patterns and trends [Dissertation]. Chapter 2, Measuring ambulatory mental health services using administrative data. [Dissertation]. University of Toronto, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frohlich N, Mustard C. A regional comparison of socioeconomic and health indices in a Canadian province. Soc Sci Med 1996;42:1273–81. 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00220-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pampalon R, Raymond G. A deprivation index for health and welfare planning in Quebec. Chronic Dis Can 2000;21:104–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ontario Marginalization Index. User Guide Version 1.0. http://www.crunch.mcmaster.ca/documents/ON-Marg_user_guide_1.0_FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ontario Marginalization Index (ON-Marg). http://www.crunch.mcmaster.ca/ontario-marginalization-index [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matheson F, Dunn JR, Smith KL et al. Development of the Canadian Marginalization Index: a new tool for the study of inequality. Can J Public Health 2012;103(Suppl 2):S12–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vasiliadis HM, Lesage A, Adair C et al. Service use for mental health reasons: cross-provincial differences in rates, determinants, and equity of access. Can J Psychiatry 2005;50:614–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin E, Goering P, Offord DR et al. The use of mental health services in Ontario: epidemiologic findings. Can J Psychiatry 1996;41:572–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leaf PJ, Bruce ML, Tischler GL et al. Factors affecting the utilization of specialty and general medical mental health services. Med Care 1988;26:9–26. 10.1097/00005650-198801000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Piccinelli M, Wilkinson G. Gender differences in depression. Critical review. Br J Psychiatry 2000;177:486–92. 10.1192/bjp.177.6.486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bracke P. The three-year persistence of depressive symptoms in men and women. Soc Sci Med 2000;51:51–64. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00432-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Afifi M. Gender differences in mental health. Singapore Med J 2007;48:385–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muntaner C, Eaton WW, Miech R et al. Socioeconomic position and major mental disorders. Epidemiol Rev 2004;26:53–62. 10.1093/epirev/mxh001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Women in Canada: a gender-based statistical report. Statistics Canada, Ottawa, ON: http://ywcacanada.ca/data/research_docs/00000189.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 46.McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X et al. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:940–3. 10.1093/aje/kwg074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.World Health Organization. Rules and Guidelines for Mortality and Morbidity Coding. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, Volume 2. 2nd edn. Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Whitley R, Kirmayer LJ, Groleau D. Understanding immigrants’ reluctance to use mental health services: a qualitative study from Montreal. Can J Psychiatry 2006;51:205–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fenta H, Hyman I, Noh S. Health service utilization by Ethiopian immigrants and refugees in Toronto. J Immigr Minor Health 2007;9:349–57. 10.1007/s10903-007-9043-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kirmayer LJ, Weinfeld M, Burgos G et al. Use of health care services for psychological distress by immigrants in an urban multicultural milieu. Can J Psychiatry 2007;52:295–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kirmayer LJ, Narasiah L, Munoz M et al. Common mental health problems in immigrants and refugees: general approach in primary care. CMAJ 2011;183:1–9. 10.1503/cmaj.090292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clark N. Examining community capacity to support Karen refugee women's mental health in the context of resettlement in Canada. Social Aetiology of Mental Illness [SAMI] Webinar on May 27, 2014.

- 53. Recent immigrants are the most educated and yet underemployed in the Canadian Labour Force. http://martinprosperity.org/2009/03/12/recent-immigrants-are-the-most-educated-and-yet-underemployed-in-the-canadian-labour-force/2013.

- 54. Health-care utilization in Canada: 25 years of evidence. SEDAP Research Paper No. 190. http://socserv.mcmaster.ca/sedap/p/sedap190.pdf.

- 55.Kephart G, Thomas VS, MacLean DR. Socioeconomic differences in the use of physician services in Nova Scotia. Am J Public Health 1998;88:800–3. 10.2105/AJPH.88.5.800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Katz SJ, Hofer TP, Manning WG. Physician use in Ontario and the United States: the impact of socioeconomic status and health status. Am J Public Health 1996;86:520–4. 10.2105/AJPH.86.4.520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roos NP, Mustard CA. Variation in health and health care use by socioeconomic status in Winnipeg, Canada: does the system work well? Yes and no. Milbank Q 1997;75:89–111. 10.1111/1468-0009.00045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Adler NE, Newman K. Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21:60–76. 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Averina M, Nilssen O, Brenn T et al. Social and lifestyle determinants of depression, anxiety, sleeping disorders and self-evaluated quality of life in Russia—a population-based study in Arkhangelsk. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2005;40:511–18. 10.1007/s00127-005-0918-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lorant V, Deliege D, Eaton W et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:98–112. 10.1093/aje/kwf182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Amaddeo F, Jones J. What is the impact of socio-economic inequalities on the use of mental health services? Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc 2007;16:16–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Silver E, Mulvey EP, Swanson JW. Neighborhood structural characteristics and mental disorder: Faris and Dunham revisited. Soc Sci Med 2002;55:1457–70. 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00266-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Caron J, Liu A. Factors associated with psychological distress in the Canadian population: a comparison of low-income and non low-income sub-groups. Community Ment Health J 2011;47:318–30. 10.1007/s10597-010-9306-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Boardman AP, Hodgson RE, Lewis M et al. Social indicators and the prediction of psychiatric admission in different diagnostic groups. Br J Psychiatry 1997;171:457–62. 10.1192/bjp.171.5.457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Advancing Health Equity. http://www1.toronto.ca/wps/portal/contentonly?vgnextoid=31a64485d1210410VgnVCM10000071d60f89RCRD

- 66.Ontario Public Health Standards 2008. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/oph_standards/docs/ophs_2008.pdf

- 67.Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity in Canada. http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99–010-x/99–010-x2011001-eng.cfm (accessed 2014).

- 68.Kurdyak P, Stukel TA, Goldbloom D et al. Universal coverage without universal access: a study of psychiatrist supply and practice patterns in Ontario. Open Med 2014;8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Aday LA, Andersen R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res 1974;9:208–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ali JS, McDermott S, Gravel RG. Recent research on immigrant health from statistics Canada's population surveys. Can J Public Health 2004;95:I9–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Breslau J, Borges G, Hagar Y et al. Immigration to the USA and risk for mood and anxiety disorders: variation by origin and age at immigration. Psychol Med 2009;39:1117–27. 10.1017/S0033291708004698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Glazier RH, Zagorski BM, Rayner J. Comparison of primary care models in Ontario by demographics, case mix and emergency department use, 2008/09 to 2009/10. ICES Investigative Report Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Flight to Canada: The Refugee Process. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/flight-to-canada-the-refugee-process-1.889045, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 74.OHIP Coverage Waiting Period. © QUEEN'S PRINTER FOR ONTARIO, 2009–2010. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/publications/ohip/ohip_waiting_pd.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 75.Institutionalizing Precarious Immigration Status in Canada (CERIS Working Paper No. 61). http://digitalcommons.ryerson.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=ece, 2013

- 76.Breslau J, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Borges G et al. Risk for psychiatric disorder among immigrants and their US-born descendants: evidence from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. J Nerv Ment Dis 2007;195:189–95. 10.1097/01.nmd.0000243779.35541.c6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fuller-Thomson E, Noack AM, George U. Health decline among recent immigrants to Canada: findings from a nationally-representative longitudinal survey. Can J Public Health 2011;102:273–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rotermann M. The impact of considering birthplace in analyses of immigrant health (Catalogue no. 82–003-XPE). Statistics Canada; December 2011.

- 79.Edge S, Newbold B. Discrimination and the health of immigrants and refugees: exploring Canada's evidence base and directions for future research in newcomer receiving countries. J Immigr Minor Health 2013;15:141–8. 10.1007/s10903-012-9640-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gender, Ethnicity and Depression: Intersectionality in Mental Health Research with African American Women. http://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1005&context=psych_scholarship [Google Scholar]