SUMMARY

Adult neurogenic niches harbor quiescent neural stem cells, however their in vivo identity has been elusive. Here, we prospectively isolate GFAP+CD133+ (quiescent neural stem cells, qNSCs) and GFAP+CD133+EGFR+ (activated neural stem cells, aNSCs) from the adult ventricular-subventricular zone. aNSCs are rapidly cycling, highly neurogenic in vivo and enriched in colony-forming cells in vitro. In contrast, qNSCs are largely dormant in vivo, generate olfactory bulb interneurons with slower kinetics, and only rarely form colonies in vitro. Moreover, qNSCs are Nestin-negative, a marker widely used for neural stem cells. Upon activation, qNSCs upregulate Nestin and EGFR, and become highly proliferative. Notably, qNSCs and aNSCs can interconvert in vitro. Transcriptome analysis reveals that qNSCs share features with quiescent stem cells from other organs. Finally, small molecule screening identified the GPCR ligands, S1P and PGD2, as factors that actively maintain the quiescent state of qNSCs.

INTRODUCTION

Quiescent and actively dividing (activated) stem cells co-exist in adult stem cell niches (Li and Clevers, 2010). Stem cell quiescence and activation play an essential role in many organs, underlying tissue maintenance, regeneration, function, plasticity, aging, and disease. Quiescent stem cells dynamically integrate extrinsic and intrinsic signals to either actively maintain their dormant state or become activated to divide and give rise to differentiated progeny (Cheung and Rando, 2013). To illuminate their biology and their molecular regulation, it is essential to be able to prospectively identify and purify quiescent stem cells. However, this has been exceedingly difficult in any organ, including the adult brain.

Adult neural stem cells continuously generate neurons throughout life in two brain regions: the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the hippocampus and the ventricular-subventricular zone (V-SVZ), adjacent to the lateral ventricles. The V-SVZ is the largest germinal region in the adult mammalian brain and generates olfactory bulb interneurons and oligodendrocytes. Within the V-SVZ, GFAP+ Type B cells with hallmark features of astrocytes are stem cells and have multipotent self-renewing capacity in vitro (Doetsch et al., 1999a; Laywell et al., 2000; Imura et al., 2003; Garcia et al., 2004; Sanai et al., 2004; Ahn and Joyner, 2005; Mirzadeh et al., 2008; Beckervordersandforth et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2012). In vivo, actively dividing V-SVZ stem cells are eliminated by antimitotic treatment (Pastrana et al., 2009). In contrast, slowly dividing astrocytes are label-retaining cells (LRCs), survive treatment with anti-mitotic drugs and regenerate the V-SVZ, and give rise to neurons under homeostasis (Doetsch et al., 1999a; Ahn and Joyner, 2005; Giachino and Taylor, 2009; Nam and Benezra, 2009; Kazanis et al., 2010; Basak et al., 2012).

Recently, novel features of the anatomical organization of the V-SVZ stem cell niche have been uncovered. GFAP+ Type B1 cells have a radial morphology and span different compartments of the stem cell niche (Silva-Vargas et al, 2013). Their apical processes contact the lateral ventricle at the center of pinwheel structures formed by ependymal cells, exhibit a primary cilium and are exposed to signals in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (Doetsch et al., 1999a, Mirzadeh et al., 2008, Beckervordersandforth et al., 2010, Kokovay et al., 2012). Their basal processes contact blood vessels, which are an important proliferative niche in the adult V-SVZ (Shen et al., 2008; Mirzadeh et al., 2008; Tavazoie et al., 2008; Kazanis et al., 2010; Kokovay et al., 2010, Lacar et al., 2011; Lacar et al., 2012).

Various molecular markers have been used for the in vivo identification of V-SVZ stem cells and their purification (reviewed in Pastrana et al., 2011). Nestin and Sox2 are widely used as neural stem cell markers in both the embryonic and adult brain (Lendahl et al., 1990; Graham et al., 2003; Kazanis et al., 2010; Imayoshi et al., 2011; Marques-Torrejon et al., 2013). CD133 (Prominin), a transmembrane glycoprotein expressed on primary cilia of neural progenitors (Uchida et al., 2000; Marzesco et al., 2005; Pinto et al., 2008; Cesetti et al., 2011) has been used to distinguish GFAP+CD133+ stem cells from niche astrocytes (Mirzadeh et al., 2008, Beckervordersandforth et al., 2010). Combinations of markers are beginning to be identified that allow the purification of different subpopulations of V-SVZ cells, in particular of activated stem cells, including Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) (Doetsch et al., 2002; Pastrana et al., 2009), and Brain Lipid Binding Protein (BLBP) (Giachino et al., 2013). To date, however, combinations of markers have not been identified that allow the prospective isolation of quiescent V-SVZ stem cells. This is crucial to illuminate the functional properties and gene regulatory networks of quiescent adult neural stem cells.

Here, for the first time, we prospectively identify and isolate quiescent adult neural stem cells from their niche. Our findings reveal that CD133+ astrocytes comprise two functionally distinct populations, quiescent (qNSCs) and activated (aNSCs) neural stem cells, which differ dramatically in their in vivo cell cycle status and lineage kinetics, in vitro colony-forming efficiencies and their molecular signatures. Notably, qNSCs only rarely form colonies in vitro and are natively Nestin-negative but upregulate both Nestin and EGFR upon activation. qNSCs also share common molecular features with their counterparts in other organs. Finally, we identify GPCR ligands that actively maintain the quiescent state of qNSCs.

RESULTS

Two populations of CD133+ V-SVZ astrocytes contact the lateral ventricle

The intermediate filament glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) is one of the few markers of Type B1 astrocytes (Doetsch et al., 1997; Mirzadeh et al., 2008). However, due to its filamentous nature, it is difficult to perform co-localization studies with GFAP, and it cannot be used for live cell sorting. GFAP::GFP mice in which GFP is expressed under the control of the human GFAP (hGFAP) promoter (Zhuo et al., 1997) are a useful tool for visualizing V-SVZ astrocytes in vivo and for their FACS purification (Tavazoie et al., 2008; Platel et al., 2009, Shen et al., 2008, Pastrana et al., 2009; Beckervordersandforth et al., 2010). Whole mount preparations allow the pinwheel architecture of the walls of the lateral ventricle to be clearly visualized. We confirmed that in GFAP::GFP mice, Type B1 astrocytes contacting the ventricle at the center of pinwheels were GFP+ and GFAP+, and frequently had a primary cilium, but lacked S100β expression, a marker of mature astrocytes that are found deeper in the tissue at the interface with the striatum (S1A and S1C–D).

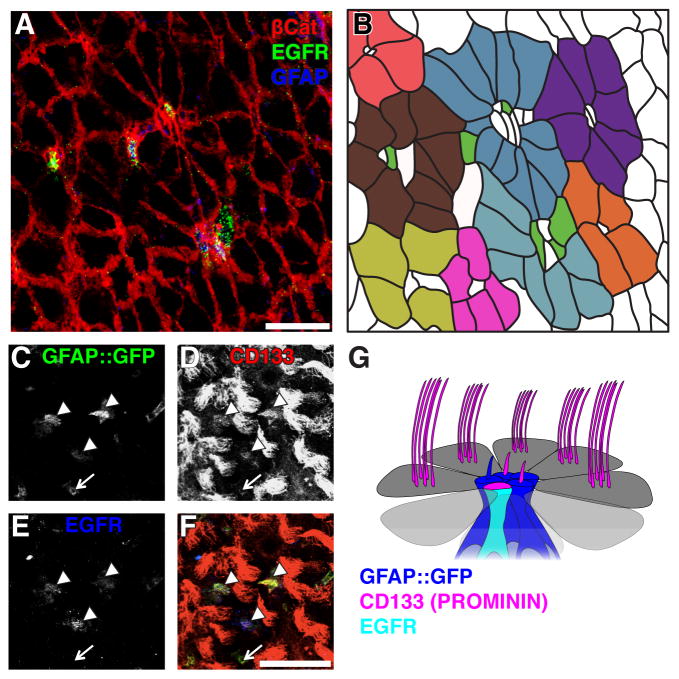

Strikingly, a subset of cells localized within individual pinwheels was EGFR+ (11.4±1.3%, n=129 pinwheels) (Figure 1AB). These ventricle-contacting EGFR+ cells co-expressed both GFAP protein and GFP in GFAP::GFP mice (Figure S1B, Pastrana et al., 2009) and were observed throughout the rostro-caudal axis of the V-SVZ, with 45.7±4.4% of pinwheels containing EGFR+ cells.

Figure 1. Two populations of CD133+ V-SVZ astrocytes contact the ventricle.

(A–B) A subset of GFAP+ cells at the center of pinwheels express EGFR. (A) Confocal image of a whole mount immunostained for β-Catenin (red) to visualize pinwheels, GFAP (blue) and EGFR (green). (B) Schematic representation of whole mount shown in A. Individual pinwheels are highlighted in different colors and EGFR expressing cells are green.

(C–F) Optical slice of a confocal Z-stack at the ventricular surface of a whole mount showing endogenous GFP expression GFP under the control of the human GFAP promoter (C) and immunostained for CD133 (D) and EGFR (E). (F) Merged image. Note that astrocytes contacting the ventricle with diffuse CD133 staining are EGFR+ (arrowheads), whereas those with CD133 restricted to the primary cilium are EGFR− (arrow).

(G) Schema showing Type B1 astrocytes contacting the ventricle at the center of a pinwheel structure formed by ependymal cells (grey). CD133 (Prominin, magenta) is detected on the cilia of ependymal cells, some primary cilia of some Type B1 astrocytes (blue) and is diffusely expressed on the apical surface of EGFR+ Type B1 astrocytes (cyan). Scale bars: 30 μm.

See also Figure S1 and S2.

To define markers for EGFR negative Type B1 cells contacting the ventricle, we examined the expression of CD133 (Prominin), which is expressed by ependymal cells and on the primary cilium of some Type B1 cells (Coskun et al., 2008; Mirzadeh et al., 2008; Beckervordersandforth et al., 2010). We immunostained whole mounts of GFAP::GFP mice for EGFR and CD133, in conjunction with β-Catenin to label pinwheels, or acetylated tubulin to detect primary cilia. We thereby identified two CD133+ astrocyte populations: GFAP::GFP+CD133+ and GFAP::GFP+CD133+EGFR+ (Figure 1G). GFAP::GFP+CD133+ cells had a primary cilium with CD133 staining localized to its tip (Figure 1C–F, S2A and S2C). In contrast, GFAP::GFP+CD133+EGFR+ cells exhibited diffuse CD133 staining over their apical surface and lacked a primary cilium (Figure 1C–F, S2B and S2D). Finally, we also observed GFAP::GFP+ cells contacting the ventricle, which had a primary cilium that was CD133-negative (Figure S2A and S2C).

Visualizing the in vivo morphology of CD133+ Type B1 cells is not feasible by immunostaining. To this end, we cloned and electroporated a construct that expresses membrane-targeted mCherry under the control of the mouse minimal P2 (Prominin1) promoter (mP2-mCherry, Figure S3A) into the lateral ventricle and analyzed whole mounts 2 days later. Both multi-ciliated flat ependymal cells possessing typical cuboidal morphology, and radial cells with B1 morphology were labeled by this construct (Figure 2A) and all co-expressed CD133 protein (23/23 cells, Figure S3B–D). Radial mP2-mCherry+ cells expressed CD133 either at the tip of their primary cilium (Figure S3C) or diffusely on their apical surface (Figure S3D) and were GFAP+ (data not shown). To define the cell cycle status and relationship of radial mP2-mCherry+ cells with ependymal cells and blood vessels, electroporated whole mounts were immunostained for combinations of EGF-A647, MCM2, β-Catenin and Laminin to label activated stem cells, dividing cells, pinwheels and blood vessels, respectively. All radial mP2-mCherry+ cells, regardless of MCM2 expression or EGF-ligand binding, had a typical B1 morphology with an apical process contacting the ventricle at the center of pinwheels and a long basal process extending away from the surface, which frequently terminated on blood vessels (Figure 2B–C and Figure S3E–N). Importantly, all MCM2+ radial mP2-mCherry+ astrocytes were co-labeled with EGF-ligand (70/70 cells MCM2− and EGF−; 5/5 cells MCM2+ and EGF+, Figure 2D–E).

Figure 2. Both quiescent and activated CD133+ V-SVZ astrocytes have radial morphology and contact the ventricle and blood vessels.

(A) Confocal images of whole mounts immunostained with β-Catenin (green) showing cells labeled by in vivo electroporation of the mP2-mCherry construct (red). Labeled cells are either radial cells that contact the ventricle at the center of pinwheels (open arrowheads in insets) or ependymal cells (asterisks).

(B–C) Confocal images of whole mounts immunostained with Laminin (cyan), β-Catenin (green) and MCM2 (blue) showing projections of mP2-mCherry+ cells (BI and CI). Insets show superficial (BII and CII) and deep (BIII and CIII) optical slices. Both MCM2− (B) and MCM2+ (C) cells contact the ventricle at the center of pinwheels as well as blood vessels.

(D–E) Confocal images of whole mounts immunostained with MCM2 (cyan) and β-Catenin (blue) and labeled with EGF-A647 (green) showing projections of mP2-mCherry+ cells (DI and EI). Insets show superficial (DII and EII) and deep (DIII and EIII) optical slices. Note that EGF negative cells are MCM2−. Scale bars: 30 μm.

See also Figure S3.

Prospective purification of V-SVZ astrocytes

The above in vivo characterization suggests that CD133 and EGFR could be used as markers to prospectively purify quiescent and activated neural stem cells directly from their in vivo niche using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). We previously developed a simple strategy to simultaneously isolate activated stem cells (GFAP::GFP+EGFR+), transit amplifying cells (EGFR+) and neuroblasts (CD24+) by combining EGF-A647 and CD24 in GFAP::GFP mice (Pastrana et al., 2009). By including CD133 in this sorting strategy, we separated two CD133+ astrocyte populations, GFAP::GFP+CD133+ and GFAP::GFP+CD133+EGFR+, from the remaining GFAP::GFP+ only cells (Figure 3A–B and S4A–I). GFAP::GFP+CD133+ (ranging from 25–30% of total GFP+ cells) and GFAP::GFP+CD133+EGFR+ (20–25% of total GFP+ cells) were both abundant, but differed in their GFP brightness (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Prospectively purified CD133+ astrocyte subpopulations exhibit different cell cycle properties.

(A–B) Representative FACS plots showing the gate used to select GFAP::GFP+CD24− cells (A), which are then gated on EGF-A647 and CD133-PE-Cy7. (B) Three populations are clearly defined: GFAP::GFP+ (grey), GFAP::GFP+CD133+ (blue) and GFAP::GFP+CD133+EGFR+ (cyan). See supplementary data for controls and other gating details (Figure S4).

(C) Histogram showing the intensity of GFP signal in GFAP::GFP+, GFAP::GFP+CD133+ and GFAP::GFP+CD133+EGFR+ populations (grey, blue and cyan respectively) compared to other V-SVZ cells (GFP−, black). Note that GFAP::GFP+CD133+EGFR+ cells are dimmer than GFAP::GFP + and GFAP::GFP+CD133 + cells.

(D) Proportion of each CD133+ purified astrocyte subpopulation that expresses Ki67 and MCM2 (n=3; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, unpaired Students’ t-test, mean±SEM).

(E) Proportion of each CD133+ purified astrocyte subpopulation labeled after a single pulse of BrdU (light green) or after 14 days of BrdU in the drinking water (dark green) (n=3 and n=4, respectively, **p<0.01, unpaired Students’ t-test, mean±SEM).

(F) Label-retaining cell (LRC) fraction in the CD133+ purified astrocyte populations 14 or 30 days after 14 days of BrdU administration (n=4, mean±SEM).

(G) Representative FACS plots of CD133+ astrocyte subpopulations from saline and Ara-C treated mice.

(H) Summary of markers expressed by CD133+ purified astrocytes.

See also Figure S4 and S6.

We assessed the purity of the sorted populations using qPCR and acute immunostaining. qPCR confirmed that sorted populations were appropriately enriched in Gfap, GFP, Prom1 and Egfr expression (Figure S4Q–T). Acute immunostaining showed that both GFAP::GFP+CD133+ and GFAP::GFP+CD133+EGFR+ populations were highly enriched in GLAST and GLT1 (Figure S4J–K), glutamate aspartate transporters expressed in astrocytes, as well as BLBP (Figure S4M), largely or completely lacked S100β (Figure S4L) and were almost completely negative for the neuroblast markers DCX and βIII Tubulin (Figure S4O–P). Notably, more than 90% of GFAP::GFP+CD133+ and GFAP::GFP+CD133+EGFR+ populations expressed the neural stem cell transcription factor Sox2 (Figure S4N and S4U). High Sox2 levels are related to a more proliferative state (Marques-Torrejon et al., 2013); interestingly, 92.8±1.5% of GFAP::GFP+CD133+EGFR+ cells expressed high levels of Sox2 protein whereas only 38.4±3.5% of GFAP::GFP+CD133+ cells were Sox2 bright, with the remainder being Sox2 dim. In contrast, the GFAP::GFP+ only population was more heterogeneous with significant neuroblast contamination, likely due to perdurance of GFP in neuroblasts (Figure S4O–P). We therefore focused our functional analyses below on GFAP::GFP+CD133+ and GFAP::GFP+CD133+EGFR+ populations (all data regarding the GFAP::GFP+ only population are included in Figure S6).

Purified GFAP+CD133+ V-SVZ cells have different cell cycle properties

Quiescent stem cells are largely dormant and lack markers of proliferation such as Ki67 and MCM2 that are expressed in actively dividing cells, but not during the quiescent G0 state (Maslov et al., 2004). Both markers are expressed during G1 with MCM2 being expressed earlier than Ki67. Cycling GFAP+ V-SVZ cells in vivo have a fast cell cycle (Ponti et al, 2013). To determine the cell cycle properties of CD133+ astrocyte subpopulations in vivo, we used multiple approaches. First, we determined the instantaneous cell cycle status of FACS-purified cells by acute immunostaining for proliferation-associated markers. GFAP::GFP+CD133+EGFR+ cells were highly enriched in both Ki67 and MCM2 (64±5.2% and 87.3±1.2%, respectively) whereas these two markers were almost absent in GFAP::GFP+CD133+ cells (1.4±0.9%; 0.0±0.0%) (Figure 3D). Similar patterns of proliferation were observed after a single in vivo pulse of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) one hour prior to FACS isolation: 35.5±1.8% of GFAP::GFP+CD133+EGFR+ cells were BrdU+, in contrast to 0.8±0.8% of GFAP::GFP+CD133+ cells (Figure 3E). Thus, at any given moment, the vast majority of GFAP::GFP+CD133+ cells are not proliferating.

Label-retaining cells (LRCs) are slowly cycling cells whose DNA remains labeled after prolonged administration of thymidine analogues and a long chase period (Wilson et al., 2008). To label dividing cells and to identify LRCs, we administered BrdU via drinking water for 2 weeks, and analyzed the proportion of each population that was BrdU+. Immediately after BrdU treatment, almost all GFAP::GFP+CD133+EGFR+ cells were labeled, whereas only 3.9±0.4% of GFAP::GFP+CD133+ cells had incorporated BrdU, reflecting their much slower rate of division (Figure 3E). 14 days after ceasing BrdU treatment, GFAP::GFP+CD133+EGFR+ cells had already almost completely lost BrdU labeling (Figure 3F). In contrast, 52.4±17.3% of GFAP::GFP+CD133+ cells were still BrdU+ 30 days after BrdU withdrawal (Figure 3F).

Finally, we confirmed the different proliferation characteristics of both populations in vivo by infusing Cytosine-β-D-arabinofuranoside (Ara-C) directly on the brain surface to eliminate dividing cells (Doetsch et al., 1999b). GFAP::GFP+CD133+ cells survived 6 days of Ara-C treatment, whereas the more rapidly dividing GFAP::GFP+CD133+EGFR+ cells were eliminated (Figure 3G). Thus, although CD133 is regulated in a cell cycle-dependent manner in dividing neural cell lines (Sun et al., 2009), in the V-SVZ niche, CD133 is expressed in both dividing and non-dividing cells in vivo.

Together, these findings reveal that GFAP::GFP+CD133+ cells are largely quiescent in vivo whereas GFAP::GFP+CD133+EGFR+ cells are actively dividing. Based on their cell cycle properties and the functional studies described below, hereafter, we refer to these populations as qNSCs and aNSCs, respectively (Figure 3H).

Quiescent and activated neural stem cells are both neurogenic in vivo but differ in their kinetics

To assess the in vivo potential of quiescent and activated stem cells, we transplanted purified qNSCs (1 week, n=8; 1 month, n=5) and aNSCs (1 week, n=5; 1 month, n=11) isolated from GFAP::GFP;β-Actin-PLAP mice (DePrimo et al., 1996) into the SVZ of wild-type recipient mice (Figure 4A). The donor cells were histochemically visualized based on their expression of the reporter human Placental Alkaline Phosphatase (PLAP). In mice transplanted with aNSCs, many migrating neuroblasts were present in the V-SVZ, the rostral migratory stream (RMS) and the olfactory bulb after only 1 week (Figure 4E–G), confirming their activated state. However, in mice transplanted with qNSCs, no neuroblasts were observed at this time point and PLAP+ cells were only present in the V-SVZ (Figure 4B–D). In contrast, after 1 month, both populations generated mature olfactory bulb interneurons (Figure 4J and 4M), and PLAP+ cells were still present in the V-SVZ in all transplants (Figure 4H and 4K). Interestingly, migrating neuroblasts were also present in the RMS in 3 out of 5 qNSC and 3 out of 11 aNSC transplanted brains, demonstrating that both populations continue to generate neurons after 1 month in vivo (Figure 4I and 4L). Oligodendrocytes were also formed by both transplanted populations (data not shown). These data show that both qNSCs and aNSCs can give rise to neurons and retain long-term neurogenic potential in vivo but exhibit very different kinetics of cell generation.

Figure 4. qNSCs and aNSCs are neurogenic in vivo.

(A) Schema of experimental design.

(B–G) Horizontal brain sections showing PLAP+ cells (purple, arrowheads) 1 week after transplantation of qNSCs (B–D) and aNSCs (E–G). At this time point, aNSCs generated numerous migrating neuroblasts, whereas no cells were detected in the RMS or in the olfactory bulb of brains transplanted with qNSCs.

(H–M) Horizontal brain sections showing PLAP+ cells (purple, arrowheads) 1 month after transplantation of qNSCs (H–J) and aNSCs (K–M). In transplants from both populations, cells were present in the V-SVZ and RMS and had generated mature olfactory bulb interneurons. Scale bars: 200 μm. STR: Striatum; CP: Choroid Plexus; LV: Lateral Ventricle; RMS: Rostral Migratory Stream; GCL: Granular Cell Layer; PGL: Periglomerular Layer.

Quiescent and activated neural stem cells differ in their in vitro behavior and can interconvert states

Two in vitro assays are widely used to assess stem cell properties and to enumerate in vivo stem cells: adherent colony formation and neurospheres (Pastrana et al., 2011). With the ability to prospectively purify qNSCs for the first time, we directly tested their in vitro behaviour in both assays, as compared to aNSCs.

qNSCs and aNSCs were plated as single cells under adherent conditions in the presence of EGF or EGF/bFGF (basic fibroblast growth factor). Whereas aNSCs were enriched in colony formation (47.9±11.9% in EGF and 41.4±1.8% in EGF/bFGF), in striking contrast, qNSCs only rarely gave rise to colonies (1.2±0.1% in EGF and 0.7±0.2% in EGF/bFGF) (Figure 5A) and did so with much slower growth kinetics than aNSCs. Importantly, although rare, the colonies formed by single qNSCs were large and multipotent, giving rise to neurons, oligodendrocytes and mature astrocytes (Figure 5B–C).

Figure 5. Purified qNSCs and aNSCs give rise to neurospheres with different proliferative properties and kinetics.

(A) Single cell colony formation efficiency of FACS-purified qNSCs and aNSCs in adherent cultures (n=3, mean±SEM).

(B) Representative phase contrast image of an adherent colony from a single qNSC after 12 days in the presence of EGF. Scale bar: 100μm.

(C) Confocal image of neurons (βIII Tubulin, red), astrocytes (GFAP, green) and oligodendrocytes (O4, blue) derived from qNSCs plated under adherent conditions. Scale bar: 10μm

(D) Quantification of cell proliferation when plated at 1.4 cells/ul with EGF under non-adherent conditions after 6 or 12 days (n=5, **p<0.01 compared to qNSCs at the same time point, unpaired Students’ t-test, mean±SEM).

(E–H) Representative FACS plots of purified CD133+ astrocytes immediately resorted after isolation from the brain (E–F) and of primary neurospheres derived from each population after 12 days for qNSCs and 6 days for aNSCs cultured in EGF (G–H).

(I–J) Clonal activation efficiency of purified GFAP::GFP+, GFAP::GFP+CD133+ and GFAP::GFP+CD133+EGFR+ cells, isolated from primary neurospheres of each population (in EGF, n=3, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, unpaired Students’ t-test, mean±SEM).

(K) Neurosphere formation 12 hours after Ara-C treatment as compared to saline treated controls (n=6, mean±SEM).

See also Figure S5 and S6.

We next compared the ability of qNSCs and aNSCs to form neurospheres, and assessed self-renewal by serial passaging. Again, qNSCs only rarely gave rise to neurospheres (0.85% in EGF, 0.82% in EGF/bFGF), in contrast to aNSCs, which robustly generated neurospheres (Figure S5B). Moreover, the proliferation of the qNSC population was delayed by 6 days compared to aNSCs (Figure 5D and S5A). However, once activated, qNSCs exhibited similar rates of division to aNSCs. Neurospheres from both populations could be serially passaged more than three times and were multipotent, giving rise to neurons, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes (Figure S5B and E). Finally, we examined whether more qNSCs were recruited to form neurospheres during in vivo regeneration, at 12 hours post-Ara-C removal when stem cell astrocytes start to divide (Doetsch et al., 1999a; 1999b; Pastrana et al., 2009). Notably, the efficiency of neurosphere formation of qNSCs purified after Ara-C treatment did not increase (Figure 5K). However, as previously shown, total neurosphere formation was almost completely eliminated after Ara-C treatment (Doetsch et al., 2002; Imura et al., 2003; Morshead et al., 2003; Garcia et al., 2004 and data not shown), confirming that the vast majority of neurospheres arise from actively dividing cells.

Together, these results reveal that aNSCs are highly enriched in colony formation. In contrast, the qNSC population rarely forms colonies and does so more slowly than aNSCs. However, once activated, qNSCs are highly proliferative and multipotent, almost indistinguishable from aNSCs (Figure S5B). We therefore assessed whether qNSCs and aNSCs can interconvert in vitro by dissociating and analyzing primary spheres by flow cytometry. Intriguingly, the vast majority of cells in neurospheres derived from qNSCs expressed both EGFR and CD133 (Figure 5E and 5G), revealing that qNSCs give rise to GFAP::GFP+CD133+EGFR+ cells in vitro. Conversely, aNSCs gave rise to both GFAP::GFP+CD133+ and GFAP::GFP+ populations (Figure 5F and 5H). Moreover, when primary spheres were dissociated and GFAP::GFP+CD133+, GFAP::GFP+CD133+EGFR+ and GFAP::GFP+ cells re-isolated, each population exhibited similar sphere formation efficiencies to primary isolated cells, with the GFAP::GFP+CD133+EGFR+ population being greatly enriched in neurosphere formation compared to GFAP::GFP+CD133+ and GFAP::GFP+ populations (Figure 5I and 5J, and S5C and S5D). Therefore, qNSCs and aNSCs can interconvert between more quiescent and activated states, with each population giving rise to all other populations in vitro.

qNSCs do not express Nestin but upregulate EGFR and Nestin upon activation

Nestin is an intermediate filament protein; its expression is widely considered a hallmark of neural stem cells, both during development and in the adult (Lendahl et al., 1990; Imayoshi et al., 2011). Unexpectedly, our microarray analysis (see below) suggested that qNSCs express very low levels to no Nestin mRNA, in contrast to aNSCs in which Nestin mRNA is highly expressed. We confirmed this observation by qPCR (Figure S8E) as well as by immunostaining of acutely purified cells (Figure 6A). Out of 1,582 plated qNSCs, none were Nestin-protein positive. Finally, to assess the Nestin status of NSCs in vivo, we electroporated mice with the mP2-mCherry construct and co-immunostained whole mounts with Nestin and EGF-ligand. In vivo, Nestin is highly expressed by ependymal cells (Doetsch et al., 1997 and Figure 6DI–EI) as well as SVZ cells (Figure 6DII–EII). All radial EGF-ligand-negative mP2-mCherry+ cells were Nestin-protein negative (Figure 6D, 0/79 cells in 7 whole mounts). In contrast, only EGF-ligand-positive cells co-expressed Nestin protein (Figure 6E, 32/34 cells in 7 whole mounts).

Figure 6. qNSCs are Nestin negative.

(A) Proportion of acutely-plated purified qNSCs and aNSCs immunostained for MCM2 and Nestin (n=3, mean±SEM).

(B) Images of FACS-purified qNSCs cultured in EGF, fixed at different time points and immunostained with EGFR, MCM2 and Nestin. Three types of cells are present: rounded cells with a condensed nucleus that do not express EGFR, MCM2 or Nestin (Type 1); rounded cells with a larger nucleus that express EGFR, MCM2 and Nestin (Type 2); EGFR+MCM2+Nestin+ cells with elongated processes (Type 3). Type 3 cells resemble aNSCs after 3 days in culture. Scale bars: 10 μm.

(C) Quantification of activated qNSCs in culture after 2 hrs, 1, 3, 5 or 7 days after plating (n=4, mean±SEM).

(D–E) Confocal images showing mP2-mCherry+ cells (red) in whole mount labeled with EGF-A647 (green) and immunostained for Nestin (blue). In D, two cells contact the ventricle between ependymal cells, do not bind EGF-A647 (DI, arrows) and are Nestin negative in the subventricular projection (DII). In E, an EGF-A647-labeled cell (EI, arrow) is co-immunostained with Nestin in the subventricular projection (EII, arrowheads in inset). Interestingly, not all processes contained Nestin. Scale bars: 30 μm.

See also Figure S7.

To investigate whether qNSCs upregulate Nestin protein upon activation, we performed a time-course analysis of qNSCs cultured in adherent conditions and immunostained for Nestin, EGFR and MCM2 (Figure 6B–C). When first isolated and plated, qNSCs were small and round and did not express Nestin, EGFR or MCM2 (Type 1). As qNSCs became activated in vitro, they underwent morphological and molecular changes, enlarging their nuclei and upregulating all three markers (Type 2). They then extended processes (Type 3) (Figure 6B–C), and began to proliferate extensively, closely resembling cultured aNSCs.

To independently confirm the lack of Nestin expression in qNSC and its upregulation upon activation, we used Nestin::Kusabira Orange reporter mice (Kanki et al., 2010; Ishizuka et al., 2011) to FACS purify CD133+Nes::OR−EGFR−CD24− (Nestin and EGFR negative) cells (Figure S7A). Acutely plated cells all lacked Nestin protein (Figure S7B), and when cultured only rarely gave rise to neurospheres (Figure S7C and S7E). Importantly, CD133+Nes::OR−EGFR−CD24− cells, which originally lacked Nestin::Kusabira Orange reporter expression, upregulated the reporter in all neurospheres that formed (Figure S7C). In contrast, purified CD133+Nes::OR+EGFR+CD24− cells were very efficient in neurosphere formation (Figure S7D–E).

Finally, we examined whether Nestin-negative qNSCs contribute to the lineage during regeneration. At present, it is not feasible to directly lineage-trace qNSCs in vivo due to the lack of specific markers. We therefore administered tamoxifen to adult GFAP::CreERT2;CAG::tdTomato reporter mice to induce recombination in GFAP-expressing cells, and chased for 10 days after the first injection to allow actively dividing cells to progress down the lineage (Figure S7F). We then infused Ara-C for 6 days to eliminate dividing cells (Figure S7F) and confirmed that all remaining lineage labeled cells were Nestin-negative (0 out of 951, Figure S7G) immediately after termination of treatment. Six days after Ara-C removal, tdTomato+Nestin+ cells were present (Figure S7H–I), as well as tdTomato+DCX+ neuroblasts (Figure S7I). These data reveal that qNSCs upregulate Nestin, as well as EGFR, during activation and contribute to the lineage during regeneration in vivo.

Gene expression analysis of purified qNSCs and aNSCs reveals distinct molecular signatures

To gain insight into the biological properties of qNSCs and to define their molecular signatures, we performed microarray analysis on RNA from FACS-purified populations isolated directly from their in vivo niche (Figure 7A, Table S1). Gene Ontology (GO) and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) (Subramanian et al. 2005) revealed that qNSCs and aNSCs have distinct molecular features (Figure 7B–D). Confirming the actively dividing state of aNSCs in vivo, their transcriptome was enriched in genes involved in the cell cycle, transcription and translation, and DNA repair (Figure 7C–D, Table S2 and S3). In contrast, qNSCs were enriched in the GO categories of cell communication, response to stimulus and cell adhesion (Figure 7B, Table S2), underscoring the dynamic regulation of the quiescent state via interaction with the microenvironment. Indeed, the most represented GSEA groups for qNSCs were related to transport, signaling, receptors, cell surface and extracellular matrix (ECM) (Figure 7D, Table S3). Notably, qNSCs and aNSCs exhibited different metabolic profiles; the majority of the differentially enriched GSEA metabolism subsets in qNSCs were related to lipid metabolism (Figure S8A), which are emerging as important signals in neural stem cell regulation (Knobloch et al., 2013), whereas those in aNSCs were DNA/RNA-related metabolism and proteasome activity (Figure S8B).

Figure 7. Gene expression analysis of qNSCs and aNSCs reveals distinct molecular signatures.

(A) Volcano plot of differentially expressed probesets in qNSCs and aNSCs. Probes have at least 2-fold change in expression and a corrected p-value < 0.05. See also Table S1.

(B–C) Pie charts showing representative GO categories for differentially expressed probesets in qNSC and aNSC (as determined in A). See also Table S2.

(D) Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) for qNSCs vs aNSCs. Sets have FDR < 0.05 and are hand-curated into thematic categories. See also Table S3.

(E–F) Percentage of overlap with signatures of quiescent and dividing stem cells from other organs: long term (LT)/quiescent signatures (G) and short term (ST)/proliferative signatures (H) as determined by fold-change analysis of published lists compared to qNSC and aNSC populations. Qui: Quiescent, HSC: Hematopoietic Stem Cells, qMuSC: Quiescent Muscle Stem Cells, qBulgeSC: Quiescent Bulge Stem Cells, qISC: Quiescent Intestinal Stem Cells. See also Table S6.

(G–J) Targeted GPCR ligand screen. See also Table S7.

(G) Quantification of qNSC activation (fold change in % Nestin+ clones) as compared to controls (empty dots). For complete screening panel, see Figure S8L.

(H) Quantification of percentage of MCM2+ cells within activated Nestin+ clones.

(I) Quantification of aNSC clones (fold change of % clones that underwent division) as compared to controls (empty dots).

(J) Quantification of total MCM2+ aNSCs. n=3, *p<0.05, ***p<0.001.

Functional studies have implicated numerous genes in the regulation of adult neurogenesis. Many of these were differentially expressed in qNSCs and aNSCs (Table S5). Moreover, direct comparison of qNSC and aNSC transcription profiles with those of purified GFAP::GFP+CD133+ V-SVZ stem cells (Beckervordersandforth et al 2010) revealed that we have resolved two distinct subsets of NSCs with different molecular and functional properties within their data (Figure S8C–D, Table S8). Indeed, we found that neurogenic transcription factors such as Dlx1, Dlx2, Sox4, Sox11 and Ascl1, proposed to be hallmarks of neural stem cells (Beckervordersandforth et al., 2010), were in fact primarily expressed by or restricted to aNSCs (Table S4). We confirmed enrichment of Dlx2 and Ascl1 in aNSCs by qPCR (Figure S8F–G) as well as of Dll1 (Figure S8H), which is expressed in activated neural stem cells (Kawaguchi et al., 2013). In contrast, qNSCs expressed high levels of factors reported to be markers of quiescent stem cells in the adult V-SVZ, such as Vcam1 (Figure S8I and Table S5; Kokovay et al., 2012), and in other organs, such as Lrig1 (Figure S8J and Table S1; Jensen et al., 2006 and 2009; Powell et al., 2012).

We then performed comparative analysis of our gene expression data with transcriptional signatures from quiescent or proliferative hematopoietic, muscle, skin and intestinal stem cells (Ivanova et al., 2002; Venezia et al., 2004; Forsberg et al., 2010; Pallafacchina et al., 2010; Powell et al., 2012; Blanpain et al., 2004: Fukada et al., 2007; Cheung and Rando, 2013). The majority of genes in long term/quiescent populations were upregulated in our quiescent V-SVZ stem cells, whereas those in the short term/proliferative stem cell lists from other tissues were upregulated in our activated population (Figure 7E–F, Table S6). Together, this suggests that common transcriptional programs for quiescence or activation are shared between stem cell lineages in different tissues.

GPCR signaling maintains the quiescent state

To gain insight into signaling pathways that modulate quiescence in qNSCs, we mined our transcriptome data. G Protein-Coupled Receptor (GPCR) signaling was highly enriched in qNSCs (30% of all GSEA signaling sets, Table S3). We selected 25 GPCRs that were more than 10 fold enriched in qNSCs over aNSCs (Table S7) as a basis for a functional screen to assess their role in the regulation of qNSCs. FACS purified qNSCs were plated under adherent conditions for four days in the presence of different ligands and their activation (number of Nestin+ clones) quantified (Figure S8K). Two compounds, Sphingosine-1-Phosphate (S1P) and Prostaglandin D2 (PGD2), had a significant effect, with both decreasing the activation of qNSCs by approximately one half (Figure 7G and S8L). Both ligands also decreased the number of MCM2+ qNSCs. PGD2 exerted a more potent effect, completely abolishing MCM2 expression. To determine whether these compounds act specifically on qNSCs or also affect aNSCs, we plated FACS-purified aNSCs in the presence of S1P or PGD2 and fixed the cells after 24hrs. This shorter time course is necessary as aNSC divide very rapidly making it difficult to distinguish individual clones (Figure S8K). S1P did not alter the number of aNSC clones (Figure 7I) or number of MCM2+ cells. As such, S1P selectively targets qNSCs, and appears to act at the level of qNSC recruitment (Figure 7H). In contrast, PGD2 had a potent inhibitory effect on the number of clones formed by aNSC (Figure 7I). PGD2 also reduced the number of MCM2+ aNSCs (Figure 7J). As such, PGD2 exerts a similar effect on qNSCs and aNSCs. Thus, these GPCR ligands actively maintain the adult neural stem cell quiescent state.

DISCUSSION

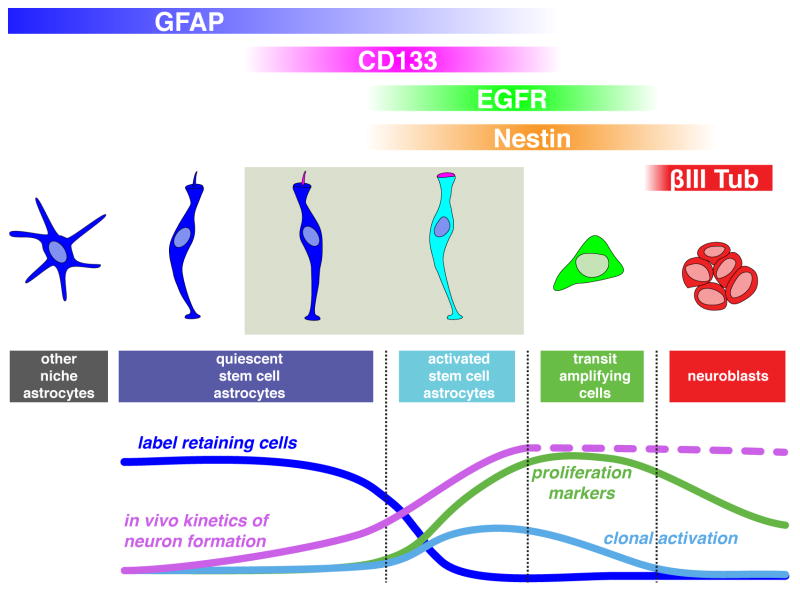

Here, we prospectively identify and isolate quiescent adult neural stem cells for the first time by defining a combination of markers (CD133, GFAP and EGFR) that allows the simultaneous purification of quiescent and activated populations of stem cell astrocytes. Together, our analyses of their cell cycle properties, morphological and anatomical localization, their in vitro and in vivo functional behavior, and their gene expression profiles reveal the distinct functional and molecular properties of qNSCs and aNSCs (Figure 8). Our functional analyses reveal important novel features of quiescent neural stem cells, which impact the interpretation of commonly used in vitro neural stem cell assays and lineage tracing strategies.

Figure 8. In vivo and in vitro properties of V-SVZ stem cells and their progeny.

Quiescent stem cells (GFAP+CD133+) are Nestin negative, label-retaining (blue line) and neurogenic in vivo (magenta line), but only very rarely give rise to neurospheres and adherent colonies in vitro (light blue line). Activated stem cells (GFAP+CD133+EGFR+) are highly proliferative (green line) and rapidly generate neurons in vivo, and are enriched in neurosphere/colony formation. Previous work has shown that EGFR+ transit amplifying cells are also highly proliferative in vivo and give rise to neurospheres. Of note, quiescent stem cells were also present among CD133− astrocytes. Niche astrocytes have a branched morphology.

In the adult mouse brain, CD133 was originally proposed to be exclusively expressed by ependymal cells, with FACS purified CD133+ cells giving rise to neurospheres in vitro and generating neurons in vivo (Coskun et al., 2008). However, CD133 is also expressed by a subset of astrocytes, which behave as neural stem cells (Mirzadeh et al., 2008; Beckervordersandforth et al., 2010), suggesting that the earlier findings can be attributed to CD133+ astrocytes instead of ependymal cells. Here, we show that CD133 is expressed by both quiescent and activated V-SVZ stem cells.

The neurosphere assay is widely used as a read-out of in vivo stem cells (reviewed in Pastrana et al., 2011). Neurospheres were originally proposed to arise from relatively quiescent stem cells in vivo (Morshead et al., 1994). With the ability to prospectively purify cells at different stages of the stem cell lineage, it is now feasible to directly assess the potential of distinct populations to give rise to neurospheres. Here, we show that qNSCs only very rarely give rise to either neurospheres or adherent colonies and do not increase their neurosphere-forming efficiency during regeneration. In contrast, aNSCs are enriched in neurosphere and adherent colony formation. Together, our current findings and previous reports highlight that the major source of neurosphere-initiating cells are actively dividing in vivo, including both GFAP+ aNSCs and EGFR+GFAP− transit amplifying cells (Doetsch et al., 2002, Imura et al., 2003; Morshead et al., 2003; Garcia et al., 2004, Pastrana et al., 2009, data not shown). Thus, the neurosphere assay is a useful tool for assessing the in vitro stem cell potential of proliferative populations, but does not allow the identification and enumeration of in vivo quiescent stem cells. This emphasizes the need to develop novel assays, or identify additional niche factors, that allow qNSCs to be expanded in vitro.

Nestin is frequently used both as a marker of neural stem cells and for their genetic manipulation and lineage tracing in the embryonic (Lendahl et al., 1990; Zimmerman et al., 1994) and adult brain (reviewed in Imayoshi et al., 2011). Nestin+ cells have also been implicated as putative glioblastoma forming cells (Holland et al., 2000, Chen et al., 2012). Strikingly, we found that adult V-SVZ qNSCs do not express Nestin, but upregulate it upon activation in vitro, as well as during regeneration in vivo. This data is consistent with previous observations that Nestin−/CD133+ cells are neurogenic in vivo and give rise to Nestin+ neurospheres in vitro (Coskun et al., 2008). Recently, both Nestin negative and Nestin-positive radial glia-like stem cells have also been described in the hippocampus (DeCarolis et al., 2013). As we show here in the V-SVZ, in the SGZ almost all of the dividing radial glia-like stem cells express Nestin (DeCarolis et al., 2013). Interestingly, in embryonic development, Nestin expression is also regulated in a cell-cycle dependent manner (Sunabori et al., 2008). Thus Nestin expression is dynamically regulated in neural stem cells. Importantly, our study highlights that Nestin immunostaining cannot be used to identify adult qNSCs in vivo. Thus, whether recombination and reporter expression occur in qNSCs needs to be carefully assessed when using Nestin transgenes for in vivo targeting of adult NSCs, V-SVZ lineage tracing, genetic manipulation or purification. Moreover, interpretation of such assays is further complicated by the high expression of Nestin in ependymal cells, which can lead to non-autonomous effects.

qNSCs are multipotent and self-renewing in vitro. Moreover, in vivo, qNSCs are long-term neurogenic, and exhibit delayed kinetics of neuron formation as compared to aNSCs. Interestingly, some aNSC transplants also continue to make neurons thirty days after transplantation. These may arise from a more quiescent subpopulation of aNSCs or from aNSCs that have reverted back to the quiescent state, as occurs in vitro. Interestingly, we also observed oligodendrocyte formation by both transplanted qNSCs and aNSCs (data not shown). In vivo, adult V-SVZ NSCs have regional identity and generate distinct neuronal subtypes, or oligodendrocytes (Merkle et al., 2007; Ventura and Goldman, 2007; Young et al., 2007; Ortega et al., 2013). At present, we cannot distinguish whether neurons and oligodendrocytes arise from regionally distinct subpopulations of NSCs in the transplanted populations, or whether some, or all, NSCs are multipotent in vivo. The extent of in vivo V-SVZ stem cell heterogeneity and population dynamics of qNSCs and aNSCs, as well as their lineage relationships and potential under homeostasis and during regeneration, will require the identification of novel markers allowing the specific targeting of qNSCs and aNSCs. Importantly, our present strategy allows qNSCs to be isolated irrespective of their regional origin. Of note, the GFAP::GFP+CD133− population also contains quiescent stem cells. Moreover, by combining different reporter mice, it is emerging that V-SVZ stem cells are molecularly heterogeneous (Giachino et al, 2013). The iterative identification of additional markers that allow subpopulations of neural stem cells to be isolated and targeted in vivo is a key future step.

Recent findings suggest that quiescent and activated states are differentially regulated at multiple levels, including cell-cell and extracellular matrix interactions, diffusible signals and distinct transcriptional programs coupling cell cycle regulators, quiescence, self-renewal and differentiation (Kazanis et al., 2010; Young et al., 2011; Le Belle et al., 2011; Alfonso et al., 2012; Basak et al., 2012; Marques-Torrejon et al., 2012; Kokovay et al, 2012; Porlan et al., 2013; Giachino et al., 2013; Kawaguchi et al., 2013, López-Juárez et al., 2013; Martynoga et al., 2013). Our transcriptome data of qNSCs and aNSCs isolated directly from their in vivo niche provide a platform to functionally assess the gene regulatory networks active in each state. Interestingly, our GSEA analysis reveals that GPCR signaling is specifically enriched in qNSCs. While GPCRs modulate many different facets of adult neurogenesis (Doze and Perez, 2012), our findings highlight that they are also key regulators of qNSCs. Strikingly, both functional ligands we identify in our GPCR screen, S1P and PGD2, inhibit the activation of qNSCs, suggesting that stem cell quiescence is an actively maintained state. Both S1P and PGD2 are present in the CSF (Sato et al., 2007; Kondabolu et al., 2011), which is emerging as a reservoir of factors in the embryo and the adult important for stem cell regulation (Silva-Vargas et al., 2013). As such, the CSF may be a key niche compartment mediating quiescence in the adult V-SVZ. Interestingly, PGD2 has been implicated in promoting the quiescent phase of the hair follicle cycle (Garza et al., 2012), consistent with our transcriptome data suggesting that quiescent and activated stem cells in different tissues share common molecular pathways.

As additional mediators of stem cell quiescence and activation are uncovered, it will be important to investigate how clinical drugs targeting these pathways impact neural stem cells in vivo. For instance, Fingolimod, an immunomodulatory drug approved by the FDA for the treatment of Multiple Sclerosis (Kappos et al., 2006), acts on S1P receptors. Recent studies have shown that Fingolimod also acts on multiple CNS cell types (Groves et al., 2013), including astrocytes. Our identification of S1P as a regulator of stem cell quiescence suggests that this drug may have an effect on neural stem cells in the adult brain.

The ability to purify quiescent neural stem cells from the adult brain opens new vistas into elucidating the biology of stem cell quiescence, enabling studies into their intrinsic and extrinsic molecular regulation and defining their dynamics during development and aging. V-SVZ GFAP+ stem cells are also present in humans, where they are largely quiescent (Sanai et al., 2004; van der Berge et al., 2010; Sanai et al., 2011). Understanding the biology of stem cell quiescence and activation will ultimately lead to insight into how neural stem cells contribute to brain pathology and can be harnessed for brain repair.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animal use

Experiments were performed in accordance with institutional and national guidelines for animal use. All mice used were between 2- and 3-months old.

FACS

The FACS strategy was adapted from Pastrana et al., 2009. Briefly, the V-SVZ was microdissected from GFAP::GFP mice, dissociated with papain, the single cell suspension immunostained and cell populations purified by FACS as described in the detailed protocol in Supplementary Methods.

Immunostaining

Whole mounts were dissected and processed as previously described (Doetsch et al., 1999b; Tavazoie et al., 2008; Mirzadeh et al., 2010). Briefly, whole mounts were blocked in 10% serum, incubated with primary antibodies for 48 hours at 4C, revealed with secondary antibodies and imaged with a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope. All immunostainings were performed in triplicate. Immunostaining details for whole mounts and cell cultures are in the Supplementary Methods.

In vitro assays

For neurosphere assays, FACS-purified cells were collected in neurosphere medium without growth factors and plated at clonal density with EGF (20 ng/ml) or EGF/bFGF (20 ng/ml each). For adherent cultures, purified cells were collected in neurosphere medium and plated on poly-D-Lysine and Fibronectin coated 96-well plates as single cells or at clonal density and cultured with EGF or EGF/bFGF. Further details are in the Supplementary Methods.

Ara-C infusion

A micro-osmotic pump (ALZET, 1007D) filled with 2% Ara-C (Sigma) in 0.9% saline was implanted onto the surface of the brain as previously described (Doetsch et al., 1999b). After 6 days of Ara-C infusion, mice were sacrificed either immediately or 12 hours after pump removal.

Electroporation

1 μl of a solution containing 5 μg/μl of the mP2-mCherry plasmid in 0.9% saline was electroporated according to Barnabe-Heider et al., 2008 using the following coordinates: AP 0.0, L 0.85, V −2.5 mm relative to bregma. The mP2-mCherry plasmid was made by cloning the mouse P2 element of the Prominin1 promoter into the CherryPicker control vector (Clontech), using the XhoI and AgeI digestion sites. See supplementary information for details.

Transplants

Three injections of 0.2 μl delivering 1,000–3,000 cells purified from GFAP::GFP/β-actin-PLAP mice were performed in the SVZ of wild-type recipient mice, using the following coordinates: (1) AP 0.0, L 1.4, V −2.1; (2) AP 0.5, L 1.1, V−2.2; (3) AP 1.0, L 1.0, V −2.5 mm relative to bregma. Recipient mice were sacrificed 1 week or 1 month after transplantation. Transplanted cells were revealed by NBT/BCIP staining.

RNA isolation and microarray hybridization

RNA was purified from FACS sorted populations by the miRNeasy kit (Qiagen) from 3 biological replicates. cDNA was synthesized with Nugen Pico amplification kit and hybridized to Affymetrix MOE430.2 chips. See supplementary information for details of bioinformatic analysis.

qPCR

RNA was purified from FACS sorted populations by the miRNeasy kit (Qiagen) and cDNA generated using WT-Ovation Pico System (NuGEN). See supplementary information for details on primer sequences.

GPCR compound screen

Cells were isolated by FACS and plated on Poly-D-Lys and Fibronectin coated 96-well plates in the presence of EGF. To assay the effect on qNSCs, compounds were added one day after plating and cells fixed and immunostained at day 4. To assay the effect on aNSCs, cells were plated with compounds, and fixed and immunostained one day later. Further details are in the Supplementary Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the Doetsch and Wichterle labs for insightful discussion and to Hynek Wichterle and Jun-An Chen for comments. We thank Hideyuki Okano for kindly providing the Nestin::Kusabira Orange and James Stringer the alkaline phosphatase reporter mice, Kristie Gordon and Sandra Tetteh of the HICCC of Columbia University for assistance with FACS and flow cytometry and Jiri Zavadil and Yutong Zhang of the OCS Genome Technology Center of NYU Langone Medical Center for microarray processing. This work was supported by NIH NINDS NS053884, NIH NINDS ARRA NS053884-03S109, NIH NINDS NS074039, NYSTEM C024287, NYSTEM C026401, and The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, The Irma T. Hirschl Foundation, The David and Lucile Packard Foundation (F.D.), Human Frontiers Scientific Program Long-Term Fellowship (V.S-V.), a NIH T32 MH 15174-29 and a fellowship from the Spanish Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia (E.P.), NIH NINDS 1F31NS079057 (A.R.M.S.) and NIH T32 GM008224 and TL1 TR000082 (A.M.D.). Work was also supported by the Jerry and Emily Spiegel Laboratory for Cell Replacement Therapies.

Footnotes

ACCESSION NUMBERS

All data are deposited in NCBI GEO under accession number GSE54653.

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures, eight figures and eight tables and can be found with this article online at http://xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahn S, Joyner AL. In vivo analysis of quiescent adult neural stem cells responding to Sonic hedgehog. Nature. 2005;437:894–897. doi: 10.1038/nature03994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso J, Le Magueresse C, Zuccotti A, Khodosevich K, Monyer H. Diazepam binding inhibitor promotes progenitor proliferation in the postnatal SVZ by reducing GABA signaling. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnabé-Heider F, Meletis K, Eriksson M, Bergmann O, Sabelström H, Harvey MA, Mikkers H, Frisén J. Genetic manipulation of adult mouse neurogenic niches by in vivo electroporation. Nat Methods. 2008;5:189–96. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basak O, Giachino C, Fiorini E, Macdonald HR, Taylor V. Neurogenic subventricular zone stem/progenitor cells are Notch1-dependent in their active but not quiescent state. J Neurosci. 2012;32:5654–66. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0455-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckervordersandforth R, Tripathi P, Ninkovic J, Bayam E, Lepier A, Stempfhuber B, Kirchhoff F, Hirrlinger J, Haslinger A, Lie DC, et al. In vivo fate mapping and expression analysis reveals molecular hallmarks of prospectively isolated adult neural stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:744–758. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanpain C, Lowry WE, Geoghegan A, Polak L, Fuchs E. Self-renewal, multipotency, and the existence of two cell populations within an epithelial stem cell niche. Cell. 2004;118:635–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesetti T, Fila T, Obernier K, Bengtson CP, Li Y, Mandl C, Hölzl-Wenig G, Ciccolini F. GABAA receptor signaling induces osmotic swelling and cell cycle activation of neonatal prominin+ precursors. Stem Cells. 2011;29:307–319. doi: 10.1002/stem.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Li Y, Yu TS, McKay RM, Burns DK, Kernie SG, Parada LF. A restricted cell population propagates glioblastoma growth after chemotherapy. Nature. 2012;488:522–6. doi: 10.1038/nature11287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung TH, Rando TA. Molecular regulation of stem cell quiescence. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14:329–40. doi: 10.1038/nrm3591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coskun V, Wu H, Blanchi B, Tsao S, Kim K, Zhao J, Biancotti JC, Hutnick L, Krueger RC, Fan G, et al. CD133+ neural stem cells in the ependyma of mammalian postnatal forebrain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:1026–1031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710000105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decarolis NA, Mechanic M, Petrik D, Carlton A, Ables JL, Malhotra S, Bachoo R, Götz M, Lagace DC, Eisch AJ. In vivo contribution of nestin- and GLAST-lineage cells to adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Hippocampus. 2013 Apr 4; doi: 10.1002/hipo.22130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePrimo SE, Stambrook PJ, Stringer JR. Human placental alkaline phosphatase as a histochemical marker of gene expression in transgenic mice. Transgenic Res. 1996;5:459–66. doi: 10.1007/BF01980211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doetsch F, García-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Cellular composition and three-dimensional organization of the subventricular germinal zone in the adult mammalian brain. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5046–5061. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-13-05046.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doetsch F, Caillé I, Lim DA, García-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Subventricular zone astrocytes are neural stem cells in the adult mammalian brain. Cell. 1999a;97:703–716. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80783-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doetsch F, García-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Regeneration of a germinal layer in the adult mammalian brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999b;96:11619–11624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doetsch F, Petreanu L, Caillé I, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. EGF converts transit-amplifying neurogenic precursors in the adult brain into multipotent stem cells. Neuron. 2002;36:1021–1034. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01133-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doze VA, Perez DM. G-protein-coupled receptors in adult neurogenesis. Pharmacol Rev. 2012;64:645–75. doi: 10.1124/pr.111.004762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg EC, Passegué E, Prohaska SS, Wagers AJ, Koeva M, Stuart JM, Weissman IL. Molecular signatures of quiescent, mobilized and leukemia-initiating hematopoietic stem cells. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8785. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukada S, Uezumi A, Ikemoto M, Masuda S, Segawa M, Tanimura N, Yamamoto H, Miyagoe-Suzuki Y, Takeda S. Molecular signature of quiescent satellite cells in adult skeletal muscle. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2448–59. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia ADR, Doan NB, Imura T, Bush TG, Sofroniew MV. GFAP-expressing progenitors are the principal source of constitutive neurogenesis in adult mouse forebrain. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:1233–1241. doi: 10.1038/nn1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garza LA, Liu Y, Yang Z, Alagesan B, Lawson JA, Norberg SM, Loy DE, Zhao T, Blatt HB, Stanton DC, et al. Prostaglandin D2 inhibits hair growth and is elevated in bald scalp of men with androgenetic alopecia. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:126ra34. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giachino C, Taylor V. Lineage analysis of quiescent regenerative stem cells in the adult brain by genetic labelling reveals spatially restricted neurogenic niches in the olfactory bulb. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:9–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giachino C, Basak O, Lugert S, Knuckles P, Obernier K, Fiorelli R, Frank S, Raineteau O, Alvarez-Buylla A, Taylor V. Molecular diversity subdivides the adult forebrain neural stem cell population. Stem Cells. 2013 doi: 10.1002/stem.1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham V, Khudyakov J, Ellis P, Pevny L. SOX2 functions to maintain neural progenitor identity. Neuron. 2003;39:749–765. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00497-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves A, Kihara Y, Chun J. Fingolimod: direct CNS effects of sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptor modulation and implications in multiple sclerosis therapy. J Neurol Sci. 2013;328:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland EC, Celestino J, Dai C, Schaefer L, Sawaya RE, Fuller GN. Combined activation of Ras and Akt in neural progenitors induces glioblastoma formation in mice. Nat Genet. 2000;25:55–7. doi: 10.1038/75596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imayoshi I, Sakamoto M, Kageyama R. Genetic methods to identify and manipulate newly born neurons in the adult brain. Front Neurosci. 2011;5:64. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2011.00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imura T, Kornblum HI, Sofroniew MV. The predominant neural stem cell isolated from postnatal and adult forebrain but not early embryonic forebrain expresses GFAP. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2824–2832. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02824.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizuka K, Kamiya A, Oh EC, Kanki H, Seshadri S, Robinson JF, Murdoch H, Dunlop AJ, Kubo K, Furukori K, et al. DISC1-dependent switch from progenitor proliferation to migration in the developing cortex. Nature. 2011;473:92–6. doi: 10.1038/nature09859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova NB, Dimos JT, Schaniel C, Hackney JA, Moore KA, Lemischka IR. A stem cell molecular signature. Science. 2002;298:601–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1073823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen KB, Watt FM. Single-cell expression profiling of human epidermal stem and transit-amplifying cells: Lrig1 is a regulator of stem cell quiescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11958–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601886103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen KB, Collins CA, Nascimento E, Tan DW, Frye M, Itami S, Watt FM. Lrig1 expression defines a distinct multipotent stem cell population in mammalian epidermis. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:427–39. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanki H, Shimabukuro MK, Miyawaki A, Okano H. “Color Timer” mice: visualization of neuronal differentiation with fluorescent proteins. Mol Brain. 2010;3:5. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappos L, Antel J, Comi G, Montalban X, O’Connor P, Polman CH, Haas T, Korn AA, Karlsson G, Radue EW, et al. Oral fingolimod (FTY720) for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1124–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi D, Furutachi S, Kawai H, Hozumi K, Gotoh Y. Dll1 maintains quiescence of adult neural stem cells and segregates asymmetrically during mitosis. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1880. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazanis I, Lathia JD, Vadakkan TJ, Raborn E, Wan R, Mughal MR, Eckley DM, Sasaki T, Patton B, Mattson MP, et al. Quiescence and activation of stem and precursor cell populations in the subependymal zone of the mammalian brain are associated with distinct cellular and extracellular matrix signals. J Neurosci. 2010;30:9771–9781. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0700-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knobloch M, Braun SM, Zurkirchen L, von Schoultz C, Zamboni N, Araúzo-Bravo MJ, Kovacs WJ, Karalay O, Suter U, Machado RA, et al. Metabolic control of adult neural stem cell activity by Fasn-dependent lipogenesis. Nature. 2013;493:226–30. doi: 10.1038/nature11689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokovay E, Goderie S, Wang Y, Lotz S, Lin G, Sun Y, Roysam B, Shen Q, Temple S. Adult SVZ lineage cells home to and leave the vascular niche via differential responses to SDF1/CXCR4 signaling. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokovay E, Wang Y, Kusek G, Wurster R, Lederman P, Lowry N, Shen Q, Temple S. VCAM1 is essential to maintain the structure of the SVZ niche and acts as an environmental sensor to regulate SVZ lineage progression. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:220–30. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondabolu S, Adsumelli R, Schabel J, Glass P, Pentyala S. Evaluation of prostaglandin D2 as a CSF leak marker: implications in safe epidural anesthesia. Local Reg Anesth. 2011;4:21–4. doi: 10.2147/LRA.S18053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacar B, Young SZ, Platel JC, Bordey A. Gap junction-mediated calcium waves define communication networks among murine postnatal neural progenitor cells. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;34:1895–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07901.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacar B, Herman P, Platel JC, Kubera C, Hyder F, Bordey A. Neural progenitor cells regulate capillary blood flow in the postnatal subventricular zone. J Neurosci. 2012;32:16435–48. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1457-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laywell ED, Rakic P, Kukekov VG, Holland EC, Steindler DA. Identification of a multipotent astrocytic stem cell in the immature and adult mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13883–13888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250471697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Belle JE, Orozco NM, Paucar AA, Saxe JP, Mottahedeh J, Pyle AD, Wu H, Kornblum HI. Proliferative neural stem cells have high endogenous ROS levels that regulate self-renewal and neurogenesis in a PI3K/Akt-dependant manner. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:59–71. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Hu J, Ralls S, Kitamura T, Loh YP, Yang Y, Mukouyama YS, Ahn S. The molecular profiles of neural stem cell niche in the adult subventricular zone. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50501. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lendahl U, Zimmerman LB, McKay RD. CNS stem cells express a new class of intermediate filament protein. Cell. 1990;60:585–95. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90662-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Clevers H. Coexistence of quiescent and active adult stem cells in mammals. Science. 2010;327:542–545. doi: 10.1126/science.1180794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Juárez A, Howard J, Ullom K, Howard L, Grande A, Pardo A, Waclaw R, Sun YY, Yang D, Kuan CY, et al. Gsx2 controls region-specific activation of neural stem cells and injury-induced neurogenesis in the adult subventricular zone. Genes Dev. 2013;27:1272–87. doi: 10.1101/gad.217539.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marqués-Torrejón MÁ, Porlan E, Banito A, Gómez-Ibarlucea E, Lopez-Contreras AJ, Fernández-Capetillo O, Vidal A, Gil J, Torres J, Fariñas I. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 controls adult neural stem cell expansion by regulating Sox2 gene expression. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:88–100. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martynoga B, Mateo JL, Zhou B, Andersen J, Achimastou A, Urbán N, van den Berg D, Georgopoulou D, Hadjur S, Wittbrodt J, et al. Epigenomic enhancer annotation reveals a key role for NFIX in neural stem cell quiescence. Genes Dev. 2013;27:1769–86. doi: 10.1101/gad.216804.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzesco AM, Janich P, Wilsch-Bräuninger M, Dubreuil V, Langenfeld K, Corbeil D, Huttner WB. Release of extracellular membrane particles carrying the stem cell marker prominin–1 (CD133) from neural progenitors and other epithelial cells. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:2849–2858. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslov AY, Barone TA, Plunkett RJ, Pruitt SC. Neural stem cell detection, characterization, and age-related changes in the subventricular zone of mice. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1726–33. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4608-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkle FT, Mirzadeh Z, Alvarez-Buylla A. Mosaic organization of neural stem cells in the adult brain. Science. 2007;317:381–384. doi: 10.1126/science.1144914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzadeh Z, Doetsch F, Sawamoto K, Wichterle H, Alvarez-Buylla A. The subventricular zone en-face: wholemount staining and ependymal flow. J Vis Exp. 2010 doi: 10.3791/1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzadeh Z, Merkle FT, Soriano-Navarro M, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Neural stem cells confer unique pinwheel architecture to the ventricular surface in neurogenic regions of the adult brain. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:265–278. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morshead CM, Reynolds BA, Craig CG, McBurney MW, Staines WA, Morassutti D, Weiss S, van der Kooy D. Neural stem cells in the adult mammalian forebrain: a relatively quiescent subpopulation of subependymal cells. Neuron. 1994;13:1071–1082. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morshead CM, Garcia AD, Sofroniew MV, van Der Kooy D. The ablation of glial fibrillary acidic protein-positive cells from the adult central nervous system results in the loss of forebrain neural stem cells but not retinal stem cells. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:76–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam HS, Benezra R. High levels of Id1 expression define B1 type adult neural stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:515–526. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega F, Gascón S, Masserdotti G, Deshpande A, Simon C, Fischer J, Dimou L, Chichung Lie D, Schroeder T, Berninger B. Oligodendrogliogenic and neurogenic adult subependymal zone neural stem cells constitute distinct lineages and exhibit differential responsiveness to Wnt signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:602–13. doi: 10.1038/ncb2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallafacchina G, François S, Regnault B, Czarny B, Dive V, Cumano A, Montarras D, Buckingham M. An adult tissue-specific stem cell in its niche: a gene profiling analysis of in vivo quiescent and activated muscle satellite cells. Stem Cell Res. 2010;4:77–91. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastrana E, Cheng LC, Doetsch F. Simultaneous prospective purification of adult subventricular zone neural stem cells and their progeny. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:6387–6392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810407106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastrana E, Silva-Vargas V, Doetsch F. Eyes wide open: a critical review of sphere-formation as an assay for stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:486–498. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platel JC, Gordon V, Heintz T, Bordey A. GFAP-GFP neural progenitors are antigenically homogeneous and anchored in their enclosed mosaic niche. Glia. 2009;57:66–78. doi: 10.1002/glia.20735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponti G, Obernier K, Guinto C, Jose L, Bonfanti L, Alvarez-Buylla A. Cell cycle and lineage progression of neural progenitors in the ventricular-subventricular zones of adult mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:1045–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219563110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porlan E, Morante-Redolat JM, Marqués-Torrejón MÁ, Andreu-Agulló C, Carneiro C, Gómez-Ibarlucea E, Soto A, Vidal A, Ferrón SR, Fariñas I. Transcriptional repression of Bmp2 by p21(Waf1/Cip1) links quiescence to neural stem cell maintenance. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1567–75. doi: 10.1038/nn.3545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell AE, Wang Y, Li Y, Poulin EJ, Means AL, Washington MK, Higginbotham JN, Juchheim A, Prasad N, Levy SE, et al. The pan-ErbB negative regulator Lrig1 is an intestinal stem cell marker that functions as a tumor suppressor. Cell. 2012;149:146–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto L, Mader MT, Irmler M, Gentilini M, Santoni F, Drechsel D, Blum R, Stahl R, Bulfone A, Malatesta P, et al. Prospective isolation of functionally distinct radial glial subtypes—Lineage and transcriptome analysis. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience. 2008;38:15–42. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanai N, Tramontin AD, Quinones-Hinojosa A, Barbaro NM, Gupta N, Kunwar S, Lawton MT, McDermott MW, Parsa AT, Manuel-García Verdugo J, et al. Unique astrocyte ribbon in adult human brain contains neural stem cells but lacks chain migration. Nature. 2004;427:740–744. doi: 10.1038/nature02301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanai N, Nguyen T, Ihrie RA, Mirzadeh Z, Tsai HH, Wong M, Gupta N, Berger MS, Huang E, Garcia-Verdugo JM, et al. Corridors of migrating neurons in the human brain and their decline during infancy. Nature 2011. 2011;478:382–6. doi: 10.1038/nature10487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Malchinkhuu E, Horiuchi Y, Mogi C, Tomura H, Tosaka M, Yoshimoto Y, Kuwabara A, Okajima F. HDL-like lipoproteins in cerebrospinal fluid affect neural cell activity through lipoprotein-associated sphingosine 1-phosphate. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;359:649–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Q, Wang Y, Kokovay E, Lin G, Chuang SM, Goderie SK, Roysam B, Temple S. Adult SVZ stem cells lie in a vascular niche: a quantitative analysis of niche cell-cell interactions. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Vargas V, Crouch EE, Doetsch F. Adult neural stem cells and their niche: a dynamic duo during homeostasis, regeneration, and aging. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2013;23:935–42. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15545–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Kong W, Falk A, Hu J, Zhou L, Pollard S, Smith A. CD133 (Prominin) negative human neural stem cells are clonogenic and tripotent. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5498. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunabori T, Tokunaga A, Nagai T, Sawamoto K, Okabe M, Miyawaki A, Matsuzaki Y, Miyata T, Okano H. Cell-cycle-specific nestin expression coordinates with morphological changes in embryonic cortical neural progenitors. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:1204–12. doi: 10.1242/jcs.025064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavazoie M, Van der Veken L, Silva-Vargas V, Louissaint M, Colonna L, Zaidi B, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Doetsch F. A specialized vascular niche for adult neural stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida N, Buck DW, He D, Reitsma MJ, Masek M, Phan TV, Tsukamoto AS, Gage FH, Weissman IL. Direct isolation of human central nervous system stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:14720–14725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berge SA, Middeldorp J, Zhang CE, Curtis MA, Leonard BW, Mastroeni D, Voorn P, van de Berg WD, Huitinga I, Hol EM. Longterm quiescent cells in the aged human subventricular neurogenic system specifically express GFAP-delta. Aging Cell. 2010;9:313–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venezia TA, Merchant AA, Ramos CA, Whitehouse NL, Young AS, Shaw CA, Goodell MA. Molecular signatures of proliferation and quiescence in hematopoietic stem cells. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura RE, Goldman JE. Dorsal radial glia generate olfactory bulb interneurons in the postnatal murine brain. J Neurosci. 2007;27:4297–4302. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0399-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson A, Laurenti E, Oser G, der Wath van RC, Blanco-Bose WE, Jaworski M, Offner S, Dunant CF, Eshkind L, Bockamp E, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells reversibly switch from dormancy to self-renewal during homeostasis and repair. Cell. 2008;135:1118–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young KM, Fogarty M, Kessaris N, Richardson WD. Subventricular zone stem cells are heterogeneous with respect to their embry- onic origins and neurogenic fates in the adult olfactory bulb. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8286–8296. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0476-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SZ, Taylor MM, Bordey A. Neurotransmitters couple brain activity to subventricular zone neurogenesis. Eur J Neurosci. 2011;33:1123–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07611.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman L, Parr B, Lendahl U, Cunningham M, McKay R, Gavin B, Mann J, Vassileva G, McMahon A. Independent regulatory elements in the nestin gene direct transgene expression to neural stem cells or muscle precursors. Neuron. 1994;12:11–24. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo L, Sun B, Zhang CL, Fine A, Chiu SY, Messing A. Live astrocytes visualized by green fluorescent protein in transgenic mice. Dev Biol. 1997;187:36–42. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.