Abstract

Objective

Theoretical and empirical support for the role of dysfunctional beliefs, safety behaviors, and increased sleep effort in the maintenance of insomnia has begun to accumulate. It is not yet known how these factors predict sleep disturbance and fatigue occurring in the context of anxiety and mood disorders. It was hypothesized that these three insomnia-specific cognitive–behavioral factors would be uniquely associated with insomnia and fatigue among patients with emotional disorders after adjusting for current symptoms of anxiety and depression and trait levels of neuroticism and extraversion.

Methods

Outpatients with a current anxiety or mood disorder (N = 63) completed self-report measures including the Dysfunctional Beliefs About Sleep Scale (DBAS), Sleep-Related Safety Behaviors Questionnaire (SRBQ), Glasgow Sleep Effort Scale (GSES), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), NEO Five-Factor Inventory (FFI), and the 21-item Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS). Multivariate path analysis was used to evaluate study hypotheses.

Results

SRBQ (B = .60, p < .001, 95% CI [.34, .86]) and GSES (B = .31, p <.01, 95% CI [.07, .55]) were both significantly associated with PSQI. There was a significant interaction between SRBQ and DBAS (B = .25, p < .05, 95% CI [.04, .47]) such that the relationship between safety behaviors and fatigue was strongest among individuals with greater levels of dysfunctional beliefs.

Conclusion

Findings are consistent with cognitive behavioral models of insomnia and suggest that sleep-specific factors might be important treatment target among patients with anxiety and depressive disorders with disturbed sleep.

Keywords: Insomnia, Anxiety, Depression, Safety behaviors, Dysfunctional beliefs, Sleep effort

Cognitive–behavioral models have emphasized the central role that dysfunctional beliefs about sleep, sleep-related safety behaviors, and increased sleep effort play in the development and maintenance of chronic insomnia disorder [1–4]. Dysfunctional beliefs about sleep include rigidly held beliefs about sleep need (e.g., needing 8 h of sleep to function) and the presumed catastrophic consequences of not sleeping well (e.g., sleeping poorly on one night affects the entire week) [1,2]. Sleep-related safety behaviors are maladaptive strategies the individual uses in an attempt to prevent these feared consequences from occurring, such as canceling obligations and reducing daytime activity levels on days following poor sleep [2]. Increased sleep effort refers to direct and active attempts to control sleep [3]. Increasing evidence supports the role these three psychological factors play in the maintenance of insomnia and daytime symptoms such as fatigue [5–12]. However, prior studies have not examined whether these three factors play a similar role in insomnia and fatigue occurring in the context of emotional (anxiety and mood) disorders. Furthermore, it is not known whether dysfunctional beliefs about sleep, sleep-related safety behaviors, and sleep effort represent unique maintaining factors for insomnia and fatigue in the context of emotional disorders, or whether they might simply be a byproduct of current symptoms of anxiety or depression or a proxy for neuroticism and extraversion, underlying trait vulnerabilities for anxiety and depressive disorders (cf. [13–17]). Such questions are directly relevant for the treatment of anxiety and mood disorders given the high rates of insomnia and fatigue among individuals with anxiety and depression [18–21]. If unique relationships are found, it would indicate that targeting current symptoms of anxiety and depression, or even underlying trait vulnerabilities, might not be sufficient for durable changes in sleep disturbance, or perhaps even the anxiety or depressive disorder. Based on the fact that the sleep and fatigue symptoms do not fully resolve with successful treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders [22–24] and given the data supporting residual insomnia as a risk factor for relapse [25,26] it was hypothesized that dysfunctional beliefs about sleep, sleep-related safety behaviors, and sleep effort would be uniquely associated with insomnia and fatigue among patients with emotional disorders after adjusting for current symptoms of anxiety and depression and the trait vulnerability dimensions of neuroticism and extraversion. Consistent with recent theoretical models of insomnia [27], it was further hypothesized that dysfunctional beliefs about sleep would interact with both sleep-related safety behaviors and sleep effort, such that safety behaviors and sleep effort would have a more deleterious effect on insomnia and fatigue severity to the extent that individuals endorsed dysfunctional beliefs more strongly.

Methods

Participants (N = 63) were recruited from patients presenting for assessment and treatment at the Center for Anxiety and Related Disorders at Boston University.1 Individuals were eligible for inclusion as long as they had a current anxiety or mood disorder diagnosis, ascertained by trained interviewers who administered the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV — Lifetime Version [28]. No exclusions were made due to comorbid diagnoses, age, or medication use. Sixty-two percent of the sample was female, 96% identified as white, 4% identified as African-American, and the mean age of participants was 34.4 (SD = 13.2; range 18–74). The rates of current clinical diagnoses were: social phobia (38%), panic disorder with or without agoraphobia (25%), generalized anxiety disorder (25%), unipolar depression (24%), specific phobia (22%), obsessive–compulsive disorder (15%), anxiety disorder NOS (10%), agoraphobia without panic disorder (4%), and posttraumatic stress disorder (3%). At the time of the assessment, prior to initiating treatment, participants also completed the self-report measures described below.

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [29]

The PSQI is a self-report inventory that assesses a broad range of sleep domains, including sleep latency, sleep duration, and overall sleep quality. Its total score ranges from 0 to 21 and provides an index of sleep quality and sleep disturbance. The PSQI has excellent psychometric properties, and is commonly used in assessment and treatment studies of insomnia [29].

Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory [30]

The MFI is a 20-item self-report instrument designed to measure several empirically supported dimensions of fatigue, including general fatigue, physical fatigue, mental fatigue, reduced motivation, and reduced activity. Total scores range from 20 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater levels of fatigue. The MFI shows good internal consistency, and has been found to correlate with other measures of fatigue [30].

Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep Scale [1]

The DBAS is a 30-item scale tapping various beliefs, attitudes, expectations, and attributions about sleep and insomnia. Each item is rated from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating stronger endorsement of dysfunctional beliefs. Total scores are calculated by computing the average item score for all 30 items. The DBAS has excellent internal consistency and a strong average item-total correlation [31].

Sleep-Related Behaviors Questionnaire [8]

The SRBQ is a 32-item self-report questionnaire reflecting behavioral strategies used to cope with insomnia during the day and at night. Total scores range from 0 to 128, with higher scores indicating more frequent engagement in sleep-related safety behaviors. The SRBQ has demonstrated strong reliability and has been shown to reliably differentiate normal and poor sleepers [8].

Glasgow Sleep Effort Scale [11]

The GSES is a 7-item self-report questionnaire reflecting perceived controllability of sleep. Total scores range from 0 to 14, with higher scores indicating greater sleep effort over the past week. The GSES has demonstrated moderate to high scale reliability as well as strong sensitivity and specificity, successfully discriminating good sleepers from individuals with insomnia [11].

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale [32]

The 21-item version of the DASS is comprised of three 7-item subscales that assess symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress occurring over the past week. This scale has demonstrated good psychometric properties [32]. The 7-item depression (DASS-D) and anxiety (DASS-A) subscales were used for the present study. Scores for each subscale ranged from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating greater levels of depression and anxiety respectively.

NEO Five Factor Inventory [33]

The NEO FFI is a 60-item self-report measure with subscales assessing each of the big five personality traits (neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness). This measure has demonstrated adequate factor structure and strong convergent and divergent validity in both normative [34] and clinical samples [35]. The 12-item neuroticism (NEO-N) and extraversion (NEO-E) sub-scales were used for the present study. Subscale scores ranged from 12 to 60, with higher scores indicating greater levels of neuroticism and extraversion.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations were computed in order to examine interrelationships among study variables in a sample of individuals with anxiety and depressive disorders. In order to control for interrelationships among study variables, multivariate path analysis was used to evaluate study hypotheses. This analytic procedure allowed for the evaluation of unique relationships between fatigue and sleep disturbance and each of the independent variables (while accounting for overlap among the independent variables and between the two dependent variables).

Results

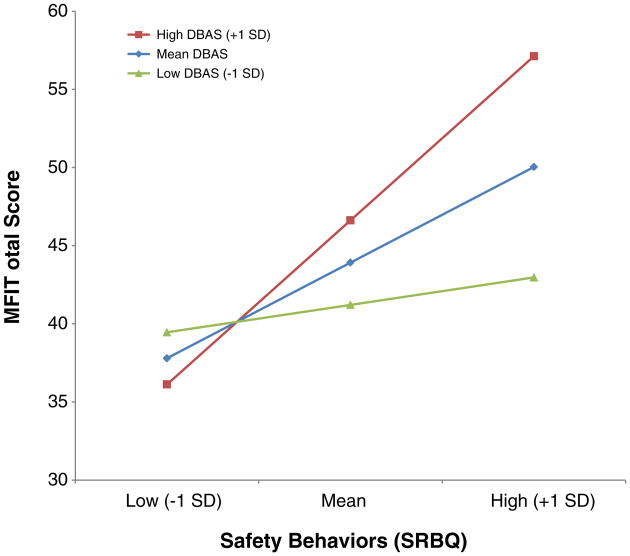

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among primary study variables are presented in Table 1. Multivariate relationships among study variables were evaluated in a single path analytic model (see Table 2). Trait neuroticism and extraversion as well as current symptoms of depression and anxiety were included in the model in order to ac-count for the possibility that relationships were better accounted for by trait vulnerabilities or state negative affect. Sleep-related safety behaviors (B = .60, p <.001, 95% CI [.34, .86]) and sleep effort (B = .31, p < .01, 95% CI [.07, .55]) were significantly associated with sleep disturbance while controlling for fatigue and interrelationships with other predictor variables. Dysfunctional beliefs about sleep (B = .06, p = .16, 95% CI [−.20, .32]) were not related to sleep disturbance. Sleep-related safety behaviors (B = .60, p<.001, 95% CI [.34, .86]) were also significantly associated with fatigue; however, this association was qualified by an interaction between sleep-related safety behaviors and dysfunctional beliefs about sleep (B = .25, p < .05, 95% CI [.04, .47]). Examination of the nature of the interaction revealed that individuals with greater levels of dysfunctional beliefs about sleep evidenced a strong relationship between sleep-related safety behaviors and fatigue, whereas individuals with lower levels of dysfunctional beliefs evidenced a much weaker relationship between safety behaviors and fatigue (see Fig. 1). Neither dysfunctional beliefs (B = .18, p = .16, 95% CI [−.07, .42]) nor sleep effort (B = −.04, p = .68, 95% CI [−.26, .17]) was related to fatigue while controlling for sleep disturbance and interrelationships with other predictor variables.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations among primary study variables in individuals with anxiety and depressive disorders (N = 63).

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PSQI | 6.05 | 3.24 | ||||||||

| 2 | MFI | 55.23 | 15.29 | .47*** | |||||||

| 3 | DBAS | 30.72 | 10.08 | 53*** | 59*** | ||||||

| 4 | SRBQ | 39.98 | 16.38 | .72*** | .64*** | .69*** | |||||

| 5 | GSES | 4.26 | 3.11 | .47*** | .24 | .49*** | .46*** | ||||

| 6 | DASS-D | 5.63 | 4.93 | .26* | .59*** | .46*** | .50*** | .30* | |||

| 7 | DASS-A | 4.19 | 4.41 | .15 | .24 | .36** | .34** | .34** | .53*** | ||

| 8 | NEO-N | 38.70 | 9.66 | .13 | .53*** | .47*** | .32* | .29* | .69*** | .37** | |

| 9 | NEO-E | 37.70 | 8.76 | −.17 | −.48*** | −.24 | −.30* | −.06 | −.53*** | −.10 | −.62*** |

Note: NEO-N = Five Factor Inventory-Neuroticism subscale; NEO-N = Five Factor Inventory-Extraversion subscale; DASS-D = Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-Depression subscale; DASS-A = Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-Anxiety subscale; DBAS = Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep; SRBQ = Sleep-Related Safety Behavior Questionnaire; GSES = Glasgow Sleep Effort Scale; PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; MFI = Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 2. Multivariate path model predicting sleep quality and fatigue among individuals with anxiety and depressive disorders (N = 63).

| Predictors | PSQI | MFI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| 95% CI | 95% CI | |||||

|

|

|

|||||

| B | Lower | Upper | B | Lower | Upper | |

| NEO-N | −.17 | −.49 | .14 | .26 | −.04 | .56 |

| NEO-E | −.08 | −.32 | .17 | −.11 | −.34 | .13 |

| DASS-D | −.03 | −.36 | .30 | .15 | −.14 | .43 |

| DASS-A | −.06 | −.29 | .16 | −.11 | −.31 | .09 |

| DBAS | .06 | −.20 | .32 | .18 | −.07 | .42 |

| SRBQ | .60*** | .34 | .86 | .36** | .11 | .60 |

| GSES | .31** | .07 | .55 | −.04 | −.26 | .17 |

| DBAS * SRBQ | .07 | −.16 | .30 | .25* | .04 | .47 |

| DBAS * GSES | −.13 | −.41 | .14 | −.13 | −.39 | .13 |

| SRBQ * GSES | −.07 | −.32 | .17 | −.03 | −.25 | .20 |

Note: NEO-N = Five Factor Inventory-Neuroticism subscale; NEO-N = Five Factor Inventory-Extraversion subscale; DASS-D = Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-Depression subscale; DASS-A = Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-Anxiety subscale; DBAS = Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep; SRBQ = Sleep-Related Safety Behavior Questionnaire; GSES = Glasgow Sleep Effort Scale; PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; MFI = Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory. Regression weights are completely standardized estimates.

p < 05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Fig. 1.

Simple slopes graph illustrating the regression of fatigue (MFI) on safety behaviors (SRBQ) at three different levels of dysfunctional beliefs (DBAS) among individuals with anxiety and depressive disorders (N = 63). DBAS = Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep; SRBQ = Sleep-Related Safety Behavior Questionnaire; MFI = Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory.

Discussion

Sleep-related safety behaviors and sleep effort were both significantly associated with the severity of sleep disturbance among people with anxiety and depressive disorders, similar to findings among those with primary insomnia [5,7,11]. The fact that these psychological factors contribute to poor sleep above and beyond trait vulnerabilities for emotional disorders and state negative affect may explain why poor sleep is a common residual symptom following treatment of anxiety and depression [22–24]. Given the evidence supporting sleep disturbance as a significant risk factor for relapse and symptom recurrence [25,26], our findings suggest that it may be important to directly target sleep-specific cognitive behavioral factors when sleep disturbance is present. This is an important area for further research and might even represent an avenue for improving long-term treatment outcomes for individuals with anxiety and depression. Indeed there are indications that treatment of insomnia among individuals with comorbid insomnia actually improves outcomes for the comorbid condition as well as insomnia symptoms [36,37].

Despite a significant bivariate relationship with sleep disturbance severity as measured by the PSQI (r = .53, p <.001), dysfunctional beliefs about sleep were not significantly related to extent of sleep disturbance in the multivariate model. This raises the possibility that safety behaviors and sleep effort might be more proximally related to sleep disturbance than beliefs that may be underlying them. Alternatively, it is possible that the observed and previously documented [38] relationship between dysfunctional beliefs about sleep and sleep disturbance was not present when controlling for affective factors because it may be better explained by current mood disturbance in this population. In order to evaluate this latter possibility, a second multivariate path model was evaluated without state affect and trait vulnerabilities included. The dysfunctional belief–sleep disturbance relationship remained non-significant in this model, consistent with the possibility that safety behaviors and sleep effort might be more proximally related to sleep disturbance. Unfortunately, the cross-sectional nature of the present data precludes proper evaluation of this proposed mediation hypothesis (cf. [39]). Although other studies have examined dysfunctional beliefs about sleep among individuals with anxiety and mood disorders [10,40], this is, to the best of our knowledge the first study to examine relationships with insomnia symptoms while controlling for current symptoms of depression and/or anxiety. Dysfunctional beliefs represent a global construct and this finding highlights the need for further specificity in examining how the dysfunctional belief construct might impact functioning. Future research is needed to examine these competing explanations.

We found that safety behaviors had a stronger relationship with fatigue among individuals with greater levels of dysfunctional beliefs. Consistent with cognitive–behavioral models of insomnia, this suggests that dysfunctional beliefs about sleep might make individuals more likely to interpret daytime symptoms such as fatigue as potentially threatening or “dangerous” and thus, ultimately, they would be more likely to engage in safety behaviors. It is possible that the perceived utility of the safety behaviors is what is driving this relationship [41]. Subsequent studies evaluating both frequency and perceived utility of safety behaviors might help clarify this relationship among people with emotional disorders.

There are a number of limitations in the present study that will need to be addressed in future studies. The cross-sectional nature of the study limits inferences that can be made regarding the temporal ordering of the study variables. Relatedly, the present study only included individuals with current emotional disorders, and thus cannot examine whether the predictor variables might predispose to or arise subsequent to the development of psychopathology. Finally, the present study utilized self-report measures to operationalize study variables and potentially comorbid conditions, such as sleep disordered breathing were not evaluated. Future studies will benefit from incorporating additional measurement modalities, such as using interview- and laboratory-based methods (for instance incorporating actigraphy or clinician-ratings of insomnia symptoms and polysomnography assessments of sleep disturbance to rule out sleep disordered breathing).

Conclusion

In an outpatient sample with anxiety and depressive disorders, sleep-related safety behaviors and sleep effort were significantly associated with sleep disturbance above and beyond trait vulnerabilities and state negative affect, suggesting the potential importance of these constructs as treatment targets. This is consistent with a burgeoning literature supporting the notion that insomnia is distinct from anxiety and depression [42] and that sleep-related processes might represent unique treatment targets. The present findings also suggest that further fine-grained analyses examining how global constructs such as dysfunctional beliefs might impact sleep disturbance in general are needed. For instance, do dysfunctional beliefs impact sleep disturbance by increasing sleep effort and safety behavior engagement? The finding that dysfunctional beliefs moderated the relationship between safety behaviors and fatigue also suggests that future studies examining how sleep-related cognitive behavioral factors might combine to impact sleep disturbance are warranted.

Footnotes

Individuals present to the Center based on referrals from health care professionals and self-referrals.

Conflict of interest statement: Drs. Fairholme and Manber have no competing interests to report.

References

- 1.Morin CM. Insomnia: psychological assessment and management. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvey AG. A cognitive model of insomnia. Behav Res Ther. 2002;40:869–93. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Espie CA, Broomfield NM, MacMahon KMA, Macphee LM, Taylor LM. The attention– intention–effort pathway in the development of psychophysiologic insomnia: a theoretical review. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10:215–45. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lundh LG, Broman JE. Insomnia as an interaction between sleep-interfering and sleep-interpreting processes. J Psychosom Res. 2000;49:299–310. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00150-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jansson-Frojmark M, Harvey AG, Norell-Clarke A, Linton SJ. Associations between psychological factors and night-time/daytime symptomatology in insomnia. J Sleep Res. 2012;21:168–9. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2012.672454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kohn L, Espie CA. Sensitivity and specificity of measures of the insomnia experience: a comparative study of psychophysiologic insomnia, insomnia associated with mental disorder and good sleepers. Sleep. 2005;28:104–12. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harvey AG. Identifying safety behaviors in insomnia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2002;190:16–21. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200201000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ree MJ, Harvey AG. Investigating safety behaviours in insomnia: the development of the sleep-related behaviours questionnaire (SRBQ) Behav Change. 2004;21:26–36. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Semler CN, Harvey AG. An investigation of monitoring for sleep-related threat in primary insomnia. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42:1403–20. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carney CE, Edinger JD, Morin CM, Manber R, Rybarczyk B, Stepanski EJ, et al. Examining maladaptive beliefs about sleep across insomnia patient groups. J Psychosom Res. 2010;68:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Broomfield NM, Espie CA. Towards a valid, reliable measure of sleep effort. J Sleep Res. 2005;14:401–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2005.00481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Semler CN, Harvey AG. An experimental investigation of daytime monitoring for sleep-related threat in primary insomnia. Cogn Emot. 2007;21:146–61. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barlow DH. Unraveling the mysteries of anxiety and its disorders from the perspective of emotion theory. Am Psychol. 2000;55:1247–63. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.11.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown TA. Temporal course and structural relationships among dimensions of temperament and DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorder constructs. J Abnorm Psychol. 2007;116:313–28. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. Structural relationships among dimensions of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders and dimensions of negative affect, positive affect, and autonomic arousal. J Abnorm Psychol. 1998;107:179–92. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown TA, Naragon-Gainey K. Evaluation of the unique and specific contributions of dimensions of the triple vulnerability model to the prediction of DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorder constructs. Behav Ther. 2013;44:277–92. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown TA, Rosellini AJ. The direct and interactive effects of neuroticism and life stress on the severity and longitudinal course of depressive symptoms. J Abnorm Psychol. 2011;120:844–56. doi: 10.1037/a0023035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soehner AM, Harvey AG. Prevalence and functional consequences of severe insomnia symptoms in mood and anxiety disorders: results from a nationally representative sample. Sleep. 2012;35:1367–75. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Mill JG, Hoogendijk WJG, Vogelzangs N, van Dyck R, Penninx BWJH. Insomnia and sleep duration in a large cohort of patients with major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders. J Clin Psychiat. 2010;71:239–46. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05218gry. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohayon MM, Roth T. Place of chronic insomnia in the course of depressive and anxiety disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 2003;37:9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(02)00052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roth T, Jaeger S, Jin R, Kalsekar A, Stang PE, Kessler RC. Sleep problems, comorbid mental disorders, and role functioning in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiat. 2006;60:1364–71. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Belanger L, Morin CM, Langlois F, Ladouceur R. Insomnia and generalized anxiety disorder: effects of cognitive behavior therapy for gad on insomnia symptoms. J Anxiety Disord. 2004;18:561–71. doi: 10.1016/S0887-6185(03)00031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carney CE, Harris AL, Friedman J, Segal ZV. Residual sleep beliefs and sleep disturbance following cognitive behavioral therapy for major depression. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28:464–70. doi: 10.1002/da.20811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nierenberg AA, Keefe BR, Leslie VC, Alpert JE, Pava JA, Worthington JJ, et al. Residual symptoms in depressed patients who respond acutely to fluoxetine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:221–5. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cho HJ, Lavretsky H, Olmstead R, Levin MJ, Oxman MN, Irwin MR. Sleep disturbance and depression recurrence in community-dwelling older adults: a prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:1543–50. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07121882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perlis ML, Giles DE, Buysse DJ, Tu X, Kupfer DJ. Self-reported sleep disturbance as a prodromal symptom in recurrent depression. J Affect Disord. 1997;42:209–12. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(96)01411-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ong JC, Ulmer CS, Manber R. Improving sleep with mindfulness and acceptance: a metacognitive model of insomnia. Behav Res Ther. 2012;50:651–60. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di Nardo PA, Brown TA, Barlow DH. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Lifetime Version (ADIS-IV-L) San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index — a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiat Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smets EMA, Garssen B, Bonke B, Dehaes JCJM. The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (Mfi) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39:315–25. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)00125-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Espie CA, Inglis SJ, Harvey L, Tessier S. Insomniacs' attributions: psychometric properties of the Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep Scale and the Sleep Disturbance Questionnaire. J Psychosom Res. 2000;48:141–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states — comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33:335–43. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Costa PT, McCrae RR. NEO PI-R professional manual: Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marsh HW, Ludtke O, Muthen B, Asparouhov T, Morin AJS, Trautwein U, et al. A new look at the big five factor structure through exploratory structural equation modeling. Psychol Assess. 2010;22:471–91. doi: 10.1037/a0019227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosellini AJ, Brown TA. The NEO Five-Factor Inventory: latent structure and relationships with dimensions of anxiety and depressive disorders in a large clinical sample. Assessment. 2011;18:27–38. doi: 10.1177/1073191110382848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manber R, Edinger JD, Gress JL, Pedro-Salcedo MGS, Kuo TF, Kalista T. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia enhances depression outcome in patients with comorbid major depressive disorder and insomnia. Sleep. 2008;31:489–95. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.4.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Margolies SO, Rybarczyk B, Vrana SR, Leszczyszyn DJ, Lynch J. Efficacy of a cognitive– behavioral treatment for insomnia and nightmares in Afghanistan and Iraq veterans with PTSD. J Clin Psychol. 2013;69:1026–42. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park JH, An H, Jang ES, Chung S. The influence of personality and dysfunctional sleep-related cognitions on the severity of insomnia. Psychiatry Res. 2012;197:275–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112:558–77. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carney CE, Edinger JD, Manber R, Garson C, Segal ZV. Beliefs about sleep in disorders characterized by sleep and mood disturbance. J Psychosom Res. 2007;62:179–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hood HK, Carney CE, Harris AL. Rethinking safety behaviors in insomnia: examining the perceived utility of sleep-related safety behaviors. Behav Ther. 2011;42:644–54. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harvey AG. Insomnia: symptom or diagnosis? Clin Psychol Rev. 2001;21:1037–59. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(00)00083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]