Abstract

Background

Academic medical centers (AMCs) have increasingly adopted conflict of interest policies governing physician-industry relationships; it is unclear how policies impact prescribing.

Objectives

Determine whether nine American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC)-recommended policies influence psychiatrists’ antipsychotic prescribing and compare prescribing between academic and non-academic psychiatrists.

Research Design

We measured number of prescriptions for 10 heavily-promoted and 9 newly-introduced/reformulated antipsychotics between 2008 and 2011 among 2,464 academic psychiatrists at 101 AMCs and 11,201 non-academic psychiatrists. We measured AMC compliance with 9 AAMC recommendations. Difference-in-difference analyses compared changes in antipsychotic prescribing between 2008 and 2011 among psychiatrists in AMCs compliant with ≥7/9 recommendations, those whose institutions had lesser compliance, and non-academic psychiatrists.

Results

Ten centers were AAMC-compliant in 2008, 30 attained compliance by 2011, and 61 were never compliant. Share of prescriptions for heavily promoted antipsychotics was stable and comparable between academic and non-academic psychiatrists (63.0-65.8% in 2008 and 62.7-64.4% in 2011). Psychiatrists in AAMC-compliant centers were slightly less likely to prescribe these antipsychotics compared to those in never compliant centers [Relative Odds Ratio (ROR), 0.95, 95% CI 0.94-0.97, <0.0001]. Share of prescriptions for new/reformulated antipsychotics grew from 5.3% in 2008 to 11.1% in 2011. Psychiatrists in AAMC-compliant centers actually increased prescribing of new/reformulated antipsychotics relative to those in never-compliant centers (ROR 1.39, 95% CI 1.35-1.44, p<0.0001), a relative increase of 1.1% in probability.

Conclusions

Psychiatrists exposed to strict conflict of interest policies prescribed heavily promoted antipsychotics at rates similar to academic psychiatrists non-academic psychiatrists exposed to less strict or no policies.

Keywords: Antipsychotics, pharmaceutical policy, practice variation, academic medical center

Physicians’ interactions with the pharmaceutical industry begin early in training,1 and take many forms including receipt of gifts, promotional contact with sales representatives, and participation in industry-sponsored continuing medical education and research.2 These interactions have been shown to influence physicians’ choice of medication, which in some cases is associated with higher costs.3 Increasingly, the financial relationships between physicians and industry and the potential conflicts of interest (COI) arising from these relationships has garnered substantial policy attention.4 Regulating professional-industry interactions to mitigate COI may be most challenging in academic medical centers (AMCs), where physicians conduct research, teach students, and supervise residents and fellows in addition to providing patient care.

Initial recommendations on regulation of physician-industry interactions in academic settings was focused on human subjects research activities.4 Between 2007 and 2009, the Institute of Medicine (IOM),4 American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC),5,6 and the American Medical Association (AMA)7 issued new policy recommendations focused on physician-industry interactions pertaining to clinical practice and medical education within AMCs. Institutions responded with a host of policies including public disclosure of remuneration from industry, which can approach income from patient care for some physicians,8,9 bans on gifts and other forms of promotion known to influence prescribing,10,11 and restrictions on funding of continuing medical education.12

It is important but challenging to determine the influence such COI policies have on physician prescribing. The IOM states the objectives of policies include preserving public trust and professional integrity but also pointed to more measurable effects such as increasing “evidence-based physician prescribing practices.”4 This point is particularly salient for drug classes such as antipsychotics, for which numerous choices exist without a clear first line treatment but with variation in prices and side effect profiles. Research on the impact of COI policies has focused on trainees only with mixed results13,14,15 while no studies have been examined the impact of policies on practicing physicians. Nor do we know how the prescribing practices of academic physicians compare with those in the community where restrictions on physician-industry relationships are far less common.

We examined prescribing of heavily-promoted antipsychotics among psychiatrists affiliated AMCs with varying adoption of COI policies as well as psychiatrists in non-academic settings between 2008 and 2011. Secondly, we examined prescribing of new and reformulated antipsychotics, which have been introduced and adopted during the era of COI regulation. We chose antipsychotics for several reasons. Antipsychotics have consistently ranked among the five highest selling drug classes in recent years.16 Physicians have many brand and generic options within the antipsychotic category with large randomized trials reporting comparable effectiveness among newer and older antipsychotics.17-19 Yet, new antipsychotics were rapidly adopted by physicians20 due to the lower risk of some side effects but also due to widespread off-label marketing and use.21-23 Thus, we expect antipsychotic prescribing patterns to be sensitive to changes in policies restricting physician-industry interactions.

METHODS

Data sources

We obtained three types of physician-level data from IMS Health. First, we obtained physician-level data on prescriptions dispensed for antipsychotics from the Xponent™ database, which directly captures over 70% of all US prescriptions filled in retail pharmacies and uses a patented proprietary projection methodology to represent 100% of prescriptions filled in these outlets. We obtained data on all monthly antipsychotic prescriptions from 2008 to 2011 for all US psychiatrists with >10 antipsychotic prescriptions in 2011. Xponent™ includes physician-level data on the number of filled prescriptions for all first- and second-generation antipsychotic products regardless of payer for patients of all ages. Second, IMS Health provided AMA Masterfile data linked to Xponent prescribing data. AMA Masterfile data, which is not limited to AMA members, includes prescriber characteristics such as demographics and medical education. Third, longitudinal information on each physician's organizational affiliations, including academic affiliations and organization size and specialty, was obtained from IMS Health's Healthcare Organizational Services (HCOS) Database, which captures physicians’ affiliations with over 29,000 practices, clinics, hospitals and integrated health systems.24 This information was used to classify psychiatrists as academic or non-academic affiliated and to classify academic psychiatrists based on exposure to different COI policies.

To identify heavily-promoted antipsychotics, we obtained monthly product-level promotion data from IMS Health's Integrated Promotional Services Audit, which tracks spending by pharmaceutical manufacturers on free samples, sales representatives’ contacts with physicians, and other promotion.

Sample definition and affiliation variables

We classified the psychiatrist population by academic affiliation. First, we identified psychiatrists affiliated with a hospital or clinic integrated with a single AMC throughout the study period, assuming that institutional policies have a stronger effect in integrated centers than in hospitals with separate administrative operations. Using the AAMC Organization Characteristics Database25 we identified integrated AMC hospitals (under common ownership with a medical school, or with a majority of medical school department chairs serving as hospital chiefs of service). Clinics were connected to teaching hospitals if they shared the organization name and city. Of the 135 US allopathic medical schools, 102 had integrated hospitals and 101 had identifiable COI policies and were thus included in the study (Supplemental Figure 1).

To examine secular trends in antipsychotic prescribing, we also collected data on psychiatrists with no academic affiliation from 2008-2011. These non-academic psychiatrists could be in private outpatient practice or affiliated with a non-AMC hospital. We excluded psychiatrists affiliated with Kaiser Permanente or Veterans Affairs health centers because prescriptions filled in Kaiser or Veterans Affairs pharmacies are not captured by Xponent™.

Conflict of interest policies

Longitudinal information on policies for the 101 integrated AMCs was obtained from the American Medical Student Association's PharmFree Scorecard26 and Columbia University's Institute on Medicine as a Profession database.27 Both databases collect information on policies from public websites and from institutions directly and have been used in previous studies.12-15 We reviewed policy descriptions for 9 domains (Gifts & Meals, Pharmaceutical Samples, Sales Representative Site Access, Speaking Relationships, Consulting, Off-Site Education, Disclosure, Purchasing and Formulary Committees, and On-Site and Continuing Medical Education) to determine compliance with AAMC recommendations.

Key independent variables

Consensus is lacking on which COI policies are the most important and on the appropriate stringency. Previous studies examined the impact of bans on gifts alone.14 However, most AMCs have adopted several additional policies often simultaneously, making it difficult to disentangle the effects of each policy. Our independent variable was affiliation with an AMC with a stringent set of policies. Our benchmark was compliance with the AAMC standard for each policy domain (Supplemental Table 1).6 As only 2 of 101 schools were compliant with all nine AAMC recommendations by 2011 we chose a cut off of ≥7/9 compliant policies for stringency among academically affiliated psychiatrists. We categorized academically affiliated psychiatrists into 3 groups based on whether their institution: 1) was ‘AAMC compliant throughout’ (≥7/9 policies compliant with AAMC recommendations throughout the study period), 2) ‘attained AAMC compliance’ (≥7/9 policies compliant after 2008), or 3) was ‘never AAMC compliant’ (<7/9 policies AAMC compliant throughout). No institution loosened its policies during the period. The fourth group of physicians was not affiliated with an academic institution at any point during the study period. We assume this group was exposed to few if any external restrictions on interactions with industry during the study period. Identification for the effect of a set of AAMC-compliant COI policies comes from comparing differences in prescribing between 2008 and 2011 among psychiatrists affiliated with academic institutions that had AAMC-compliant COI policies in 2011 but not in 2008 (the attained AAMC-compliant group) with 2008-to-2011 prescribing differences among psychiatrists in the other three groups (AAMC compliant throughout, never AAMC compliant and non-academic). Thus the key independent variables in this difference-indifferences model specification are year (2011 vs. 2008), physician group (3 academic groups and 1 non-academic group), and interaction terms between each physician group and year.

Dependent variables

We constructed two measures of prescribing behaviors. First, we measured the number of a psychiatrist's antipsychotic prescriptions filled for heavily promoted products defined as products averaging >50,000 detailing contacts annually from 2008 through 2011 (Supplemental Table 2). Second, we examined the combined number of a psychiatrist's antipsychotic prescriptions for new (introduced >2006) and orally-administered reformulated products. New products included: asenapine, paliperidone, iloperidone and lurasidone. Reformulations included dissolvable tablet reformulations of olanzapine, aripiprazole, and risperdione (Zyprexa Zydis, Abilify Discmelt, Risperdal ODT, respectively); and extended-release formulations of quetiapine (Seroquel XR); and a fixed-dose combination of olanzapine and fluoxetine (Symbyax).

Covariates

Prescribing behavior varies by physician demographic characteristics, specialty, medical education and practice setting.20,28-30 Therefore, our analyses adjusted for the following covariates: decade of medical school graduation, sex, psychiatric sub-specialty training, training at a top 20 medical school based on 2011 US News and World Report Rankings, training at a foreign medical school, and practice setting (inpatient only, both inpatient and outpatient practice, or outpatient only; affiliation with a behavioral health specialty hospital or clinic). We also adjusted for available measures of a physician's patient caseload (% of antipsychotic prescriptions paid for by Medicare or Medicaid as a proxy for disability, and % of prescriptions filled by adults). To adjust for regional variation in use of newer drugs, we included indicator variables for Census Division.

Statistical Analysis

We created graphical summaries of the number of a psychiatrist's heavily-promoted antipsychotic prescriptions filled and of the number of a psychiatrist's new or reformulated antipsychotic prescriptions filled on a quarterly basis for 2008 through 2011. We estimated non-linear mixed regression models assuming the number of heavily-promoted antipsychotics (or new/reformulated antipsychotics) per physician arose from Binomial distributions.31 We used a logit link to estimate the associations of the physician group, time (an indicator variable = 1 for prescriptions written in 2011, and 0 otherwise), and their interactions, adjusting for all covariates described above. We included a random physician term to adjust for clustering and variable prescription volumes. Two-tailed tests with p<0.05 were considered significant. Our main interest is the coefficient on the interaction term between physician group and 2011. We exponentiated the coefficient of the interaction term to obtain Odds Ratios (2011 vs. 2008) for both groups of academic psychiatrists whose institutions adopted COI policies and the non-academic group relative to the reference group (the never-AAMC compliant group) as Relative Odds Ratios. In addition, we transformed the regression coefficients from the log-odds scale to the probability scale and used bootstrapping techniques to summarize results. We randomly sampled physicians with replacement and estimated the mean difference-in-difference in the probability of prescribing heavily promoted (or new/reformulated) antipsychotics. We repeated this process 500 times to determine confidence intervals across the bootstrapped samples. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (CIs) were determined by ranking the difference-in-difference across the 500 samples and identifying the 2.5 and 97.5 percentiles. All analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approved this study.

We conducted three sensitivity analyses. First, we applied a less stringent cut off for AAMC compliance (≥5/9 instead of ≥7/9). Second, we estimated a physician fixed effects model to control for all time-invariant physician characteristics, including unmeasured variables. Third, to adjust for clustering by AMC we ran mixed models on the subset of academically affiliated physicians only that adjusted for clustering both at the physician- and the institution-level. Our results were robust to these alternate specifications, so we present only the primary analyses.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study sample

There were 5,239 psychiatrists who were affiliated with integrated AMCs at any point 2008-2011. Of those, 2,464 were affiliated with the same AMC throughout and were thus included in our analysis. We identified 11,201 psychiatrists consistently practicing in non-academic settings in the same period. Academic psychiatrists were more likely to practice in inpatient settings, and to be recent medical school graduates, and less likely to have graduated from a foreign medical school than were non-academic psychiatrists (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Psychiatrists in Sample

| AAMC Compliant Throughout | Attained AAMC Compliance | Never AAMC Compliant (reference) | All Academic (reference) | Non- Academic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychiatrists (N) | 376 (15%) | 576 (23%) | 1,512 (61%) | 2,464 | 11,201 |

| Physician Characteristics | |||||

| Mean age (SD) | 49.6 (11.6) | 48.8 (11.8)a | 50.4 (11.0) | 49.9 (11.3) | 53.5 (10.5)a |

| Female | 33.5%a | 36.8% | 38.7% | 37.5% | 31.6%a |

| % medical school graduation year > 2000 | 13.0% | 16%a | 10.4% | 12.1% | 3.5%a |

| % with subspecialty | 17.3% | 24%a | 19.6% | 20.3% | 17.4%a |

| % graduated from a top 20 medical school | 16.8% | 13.2% | 16.2% | 15.6% | 8.2%a |

| % foreign medical graduate | 26.6% | 26.9% | 19.6% | 26.9% | 37.4%a |

| 2008 mean antipsychotic prescribing volume (SD) | 608.0 (1023.5) | 421.0 (706.6) | 462.4 (729.1) | 474.9 (778.2) | 939.6 (1079.9) |

| Practice Characteristics | |||||

| % inpatient only practice | 65.7% | 62.9% | 66.9% | 65.8% | 49.4%a |

| Affiliated with behavioral health organization | 54%a | 37.5% | 39.2% | 41.0% | 58.6%a |

| Patient Characteristics | |||||

| % Medicare or Medicaid payee (SD) | 44.9%a (25.1) | 46.1% (26.7%) | 45.1% (25.7%) | 45.3% (25.8%) | 51.5% (23.5%)a |

| % adult patient (SD) | 80.3% (30.2%) | 80.9% (29.9%) | 81.6% (29.4%) | 81.2% (29.6%) | 81.4% (26.4%) |

| Region | |||||

| East North Central | 0a b | 0a b | 25.5% | 15.7% | 16.2%a b |

| East South Central | 0 | 0 | 5.5% | 3.4% | 5.0% |

| Mid-Atlantic | 52.4% | 30.0% | 17.4% | 25.7% | 19.6% |

| Mountain | 0.3% | 0.0% | 2.7% | 1.7% | 5.8% |

| New England | 22.6% | 5.4% | 21.4% | 17.8% | 8.2% |

| Pacific | 9.8% | 26.7% | 5.4% | 11.0% | 13.7% |

| South Atlantic | 0.0% | 26.0% | 11.2% | 13.0% | 18.0% |

| West North Central | 14.9% | 11.8% | 2.2% | 6.4% | 6.4% |

| West South Central | 0 | 0 | 8.9% | 5.4% | 7.2% |

= Significance level is at 0.05

= This is the test for the overall difference of regional characteristics variable between the two groups, not for the individual regional comparison

Wilcoxon non-parametric test was used to test differences for continuous variables. Chi-square tests were used to test for differences for the categorical variables.

Sources: IMS Health, HealthCare Organizational Services™, 01/2008-12/2011, IMS Health Incorporated. All Rights Reserved. AMA Masterfile, 2011.

Adoption of conflict of interest policies by academic medical centers

Of the 101 AMCs with integrated hospitals, only 10 were AAMC-compliant in 2008. The mean number of AAMC-recommended policies adopted by these compliant AMCs was similar in 2008 (7.3) and 2011 (7.5). Another 30 attained compliance during the study period, increasing the mean number of AAMC policies from 3.2 to 7.5. The 61 AMCs deemed ‘never AAMC compliant’ only increased the mean number of policies from 2.9 to 4.7 between 2008 and 2011.

Exposure to conflict of interest policies among psychiatrists

In our sample, 376 (15%) psychiatrists were affiliated with academic centers that were AAMC-compliant throughout, 576 (23%) with centers attaining AAMC compliance, and 1,512 (61%) with never-AAMC compliant centers (Table 1). Uptake of AAMC policy recommendations by AMCs varied by domain. For example, in 2011, over 90% of psychiatrists were exposed to AAMC-compliant policies on sales representative site access vs. less than 20% to policies requiring public disclosure of financial relationships with industry (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Exposure of Academic Psychiatrists to AAMC-Compliant Conflict of Interest Policies, 2008 and 2011.

[] 2008

[] 2011

Market share for heavily promoted antipsychotics

The 13,665 physicians in our sample wrote 47.7 million antipsychotics prescriptions that were filled between January 2008 and December 2011. The share of prescriptions written for heavily promoted antipsychotics was remarkably consistent over time and across groups. In 2008, 63.0% of antipsychotic prescriptions by psychiatrists in AAMC-compliant centers were for heavily promoted products vs. 65.3% for psychiatrists in centers attaining AAMC compliance and 63.9% of psychiatrists in never-AAMC compliant centers (Figure 2). In 2011, the corresponding shares were 63.7%, 62.7% and 62.7% for these groups, respectively. Non-academic psychiatrists had a similar level and stable trend in prescribing for heavily promoted products (65.6% in 2008 vs. 64.4% in 2011).

Figure 2.

Quarterly Physician-Level Market Share of Heavily Promoted Antipsychotics, by Physician Group and Conflict of Interest Policy Exposure.

Academic Affiliation: Center Attained AAMC Compliance After 2008

Academic Affiliation: Center Never AAMC Compliant 2008-2011

Academic Affiliation: Center AAMC Compliant Since 2008

Non-Academic Affiliation

After adjusting for a number of physician characteristics, psychiatrists in centers that attained AAMC compliance had a slightly larger decrease in likelihood of prescribing heavily promoted antipsychotics between 2008 and 2011 compared to psychiatrists in never-AAMC compliant centers [Relative Odds Ratios (ROR) 0.95, p<0.0001]. This represents a 0.2% relative decrease in the probability of prescribing heavily promoted drugs between groups. There was no significant difference-in-the-differences between the AAMC-compliant throughout or non-academic groups compared to the never-AAMC compliant group (Table 2). Full regression output is provided in Supplemental Table 3.

Table 2.

Difference-in-Differences Estimates of the Effect of Institutional Affiliation and Aggregate Conflict of Interest Policy Exposure on Prescribing of Heavily Promoted and New/Reformulated Antipsychotics.

| Relative Odds Ratios [95% CI]a | p-value | Difference in Differences on Probability Scale [95% CI]a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heavily Promoted Antipsychotics | |||

| AAMC Compliant Since 2008 | 1.01 [0.99, 1.02] | 0.42 | 0.002 [0.000, 0.003] |

| Attained AAMC Compliance After 2008 | 0.95 [0.94, 0.97] | <0.001 | −0.002 [−0.003, −0.001] |

| Non-Academic | 1.00 [0.99, 1.00] | 0.25 | −0.001 [−0.001, 0.000] |

| New/Reformulated Antipsychotics | |||

| AAMC Compliant Since 2008 | 1.44 [1.39, 1.49] | <0.001 | 0 [−0.001, 0.000] |

| Attained AAMC Compliance After 2008 | 1.39 [1.35, 1.44] | <0.001 | 0.011 [0.010, 0.011] |

| Non-Academic | 1.16 [1.14, 1.18] | <0.001 | 0.020 [0.020, 0.021] |

Reference is 'never AAMC compliant' group = psychiatrists affiliated with academic centers with <7/9 policies meeting AAMC recommendations for the entire study period.

Abbreviation: AAMC, Association of American Medical Colleges

Estimates from difference-in-differences regression adjusted for physician characteristics (gender, medical school graduation date, sub-specialty, medical school characteristics), affiliation characteristics and geographic region.

Sources: IMS Health, Xponent™, 01/2008-12/2011, HealthCare Organizational Services™, 01/2008-12/2011, Integrated Promotional Services™, 01/2008-12/2011, IMS Health Incorporated. All Rights Reserved. AMA Masterfile, 2011.

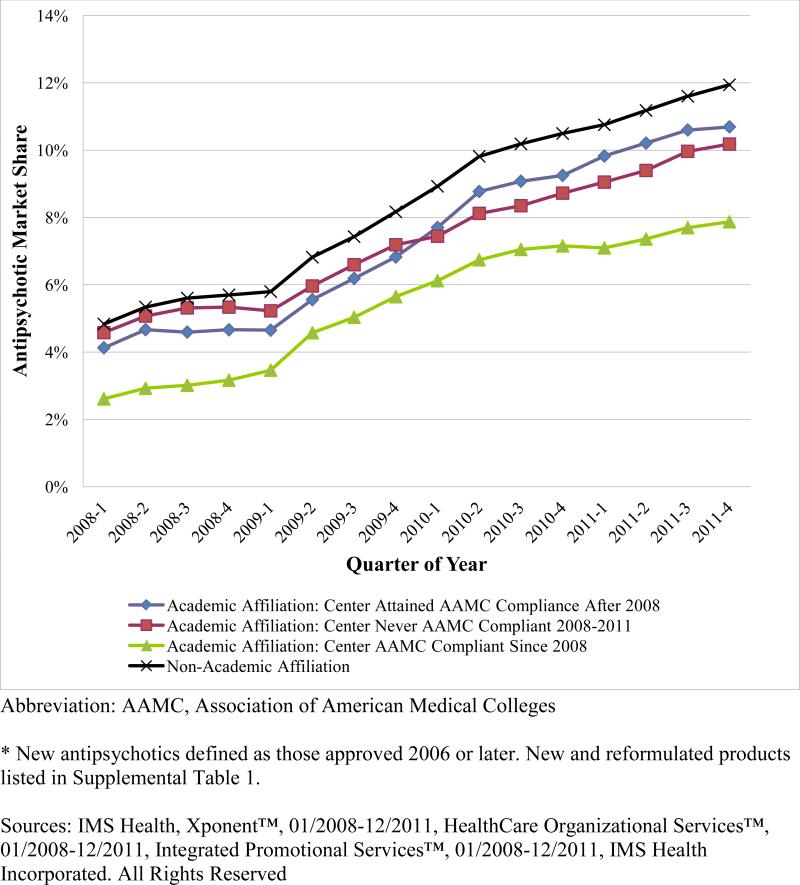

Prescribing of new and reformulated antipsychotics

The share of antipsychotic prescriptions for new and reformulated products increased in each physician group. Among the three groups of academic psychiatrists the share of prescriptions for new or reformulated products in 2008 was 2.6% in AAMC-compliant centers, 4.1% in centers attaining AAMC compliance, and 5.6% in never-compliant AMCs (Figure 3). By 2011, these shares increased to 7.9%, 10.7% and 10.2%, respectively. Non-academic psychiatrists increased prescribing of new and reformulated products from 4.8% in 2008 to 11.9% in 2011.

Figure 3.

Quarterly Physician-Level Market Share of New and Reformulated Antipsychotics, by Physician Group and Conflict of Interest Policy Exposure.

Academic Affiliation: Center Attained AAMC Compliance After 2008

Academic Affiliation: Center Never AAMC Compliant 2008-2011

Academic Affiliation: Center AAMC Compliant Since 2008

Non-Academic Affiliation

After adjusting for physician characteristics, psychiatrists in AAMC compliant centers actually had a larger relative increase in prescribing of new/reformulated antipsychotics compared to those in never-AAMC compliant centers with a ROR of 1.39 (95% CI 1.35-1.44 p<0.0001), a 1.1% relative increase. Non-academic psychiatrists also increased their prescribing of new/reformulated antipsychotics relative to the never-AAMC compliant academic group with a ROR of 1.16 (95% CI 1.14-1.18, p<0.0001), or a 2% relative increase (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

In the first study of the impact of conflict of interest policies and marketing restrictions on academic attending physicians we report three key findings. First, while there was a significant increase in adoption of strict COI policies in recent years, as of 2011, the majority of psychiatrists were affiliated with institutions only partially compliant with AAMC recommendations. Second, affiliation with an AMC adopting strict policies was associated with a small relative decrease in prescribing of heavily promoted antipsychotics but also with a small increase in prescribing of new or reformulated antipsychotics. Third, non-academic psychiatrists are significantly more likely to prescribe new and reformulated antipsychotics compared to academic psychiatrists but no more likely to prescribe heavily promoted antipsychotics.

This study adds to the small body of empirical evidence on the impact of COI policies on prescribing. Two prior studies examining prescribing of psychotropic pharmaceuticals found that exposure to restrictive policies during training was associated with small but significant reductions in prescribing of new and heavily promoted pharmaceuticals 2-7 years later.14,15 In comparison, our study of attending physicians showed minimal differences in prescribing of new and heavily promoted antipsychotics based upon exposure to restrictive policies whether newly implemented or in place for the entire study period.

There are a number of potential explanations for this unexpected finding. First, policy implementation by AMCs may influence prescribing less than other factors including comparative effectiveness research, regulatory warnings, media attention to fraudulent marketing, patient preferences and characteristics,32 physician training and prescribing volume,33 professional guidelines,34 and FDA advisories.35 We chose a difference in differences analysis approach to try to account for these secular trends.

A second potential explanation is that AAMC recommendations may not be stringent enough to impact physician prescribing behavior. Indeed, stricter policies such as banning all pharmaceutical samples and visits from sales representatives have been proposed and may have a stronger effect.36 The billions in pharmaceutical industry promotion and payments that physicians receive from the pharmaceutical industry likely exert substantial influence on prescribing.37 Industry influence is controversial, however, with some pointing to promotion as necessary for the diffusion of novel and important discoveries38 and others positing that marketing primarily drives prescribing of more expensive drugs.39 It remains intuitive that if marketing practices influence prescribing, policies that restrict marketing may result in a change in physician prescribing patterns, yet COI guidelines lacked measurable goals or expectations for changes in prescribing. Even the strictest institutional policies will not impact physician exposure to marketing within medical journals or at professional conferences, nor would such policies change patient exposure to direct to consumer marketing.40

Third, the majority of heavily-promoted antipsychotics were approved in the 1990s; thus prescribing patterns in this category may have been established before the adoption of COI policies in the late 2000s. To address this issue, we separately examined prescribing of newly introduced and reformulated antipsychotics. Again, we found that exposure to AAMC compliant policies had little impact on prescribing and all study groups greatly increased their prescribing of new and reformulated antipsychotics over the study period. In fact, physicians in AAMC-compliant centers had slightly larger increases in use of new or reformulated antipsychotics than those in never-compliant centers. We cannot rule out the possibility that some AMCs implemented strict policies in response to rapid adoption of new or reformulated products in their area and that these trends continued even after strict policy adoption. We did find that prescribing of new and reformulated antipsychotics was comparatively higher among non-academic psychiatrists, which may be due to shifting pharmaceutical marketing strategies, slower uptake of new medications by low volume prescribers, and community physicians’ preference to offer the newest treatments. Community psychiatrists practicing in outpatient settings may also be subject to different formulary restrictions.

A fourth potential explanation is that policies may have a greater impact on trainees than on practicing physicians, which is supported by the only two prior studies. Trainees may be a focus of marketing as their practices patterns are still forming however COI policies generally apply equally to physicians in training and attending physicians and trainee behavior is also likely to be modeled after their instructors’. Simultaneous with strict policy implementation, education and awareness of COI issues have increased over time and are now frequently a component of medical education.26 As both prior studies of trainees compare different generations of trainees, their difference-in-differences analyses adjust for secular trends but not cohort effects.14-15

This study has important limitations. First, we measure exposure to policies by affiliation with an AMC; however, we cannot capture the extent to which institutions enforce or educate faculty on new policies nor how application of policies may differ within or across institutions. In fact, one survey found minimal change in medical student reporting of exposure to promotion despite strict policies restricting marketing.13 This study measures exposure to policies aimed at reducing the influence of specific marketing practices; however, we are unable to directly measure physician exposure to marketing. Relatedly, we are unable to assess non-academic psychiatrists’ exposure to COI policies. Furthermore, the Xponent™ dataset has strengths in broad capture of both volume of prescriptions and individual prescribers; however it lacks patient-level data on diagnosis or indication for prescription of a medication, and on whether the prescription is new or refilled. As a result we are unable to examine prescribing for on vs. off-label uses. Finally, our findings may not be generalizable to other specialties or drug classes. We studied only psychiatrists, and focused solely on prescribing of antipsychotics, one of the most prescribed and most heavily marketed drug classes. Therapeutic options are more numerous and guidelines for selection of therapy less pronounced than in some other major drug classes.

Our study finds minimal impact of policies that restrict marketing practices on prescribing of antipsychotics, one of the most heavily marketed drug classes. These finding suggest that the intended goals and implementation of restrictive conflict of interest policies may need to be reassessed and their implementation may need to be revised.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: NIMH R01MH093359

REFERENCES

- 1.Austad KE, Avorn J, Kesselheim AS. Medical students’ exposure to and attitudes about the pharmaceutical industry: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2011;8(5):e1001037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kornfield R, Donohue JM, Berndt ER, Alexander GC. Promotion of prescription drugs to consumers and providers, 2001-2010. PLOS ONE. 2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055504. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spurling GK, Mansfield PR, Montgomery BD, et al. Information from pharmaceutical companies and the quality, quantity, and cost of physicians’ prescribing: a systematic review. PLoS medicine. 2010;7(10):e1000352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lo B, Field MJ. Conflict of interest in medical research, education, and practice. Institute of Medicine; Washington, DC: 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Association of American Medical Colleges . Protecting Patients, Preserving Integrity, Advancing Health: Accelerating the Implementation of COI Policies in Human Subjects Research. Washington, DC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Association of American Medical Colleges . Industry Funding of Medical Education: Report of an AAMC Task Force. Washington, DC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Medical Association . Conflict of Interest Guidelines for Organized Medical Staffs. Chicago, IL: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freshwater DM, Freshwater MF. Failure by Deans of Academic Medical Centers to Disclose Outside Income. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2011;171(6):586–587. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trudo H, Meyer T. [September 5, 2013];Dollars for Docs: The Top Earners 2012. 2012 http://www.propublica.org/article/dollars-for-docs-the-top-earners.

- 10.Berndt ER, Bui LT, Reiley DH, Urban GL. Information, marketing, and pricing in the US anti-ulcer drug market. American Economic Review. 1995;85(2):100–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donohue JM, Berndt ER. Direct-to-Consumer Advertising and Choice of Antidepressant. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing. 2004;23(2):115–127. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chimonas S, Evarts SD, Littlehale SK, Rothman DJ. Managing conflicts of interest in clinical care: the “race to the middle” at U.S. medical schools. Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1464–1470. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a2e204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Austad KE, Avorn J, Franklin JM, Kowal MK, Campbell EG, Kesselheim AS. Changing interactions between physician trainees and the pharmaceutical industry: a national survey. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2013;28:1064–1071. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2361-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King M, Essick C, Bearman P, Ross JS. Medical school gift restriction policies and physician prescribing of newly marketed psychotropic medications: difference-indifferences analysis. BMJ. 2013:346. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Epstein AJ, Busch SH, Busch AB, Asch DA, Barry CL. Does exposure to conflict of interest policies in psychiatry residency affect antidepressant prescribing? Med Care. 2013;51:199–203. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318277eb19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.IMS Institute for Health Informatics [March 3, 2014];The Use of Medicines in the United States: Review of 2010. 2011 http://www.imshealth.com/deployedfiles/imshealth/Global/Content/IMSInstitute/Static File/IHII_UseOfMed_report.pdf.

- 17.Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353(12):1209–1223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones PB, Barnes TRE, Davies L, et al. Randomized Controlled Trial of the Effect on Quality of Life of Second- vs First-Generation Antipsychotic Drugs in Schizophrenia: Cost Utility of the Latest Antipsychotic Drugs in Schizophrenia Study (CUtLASS 1). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(10):1079–1087. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tandon R, Carpenter WT, Davis JM. First- and second-generation antipsychotics: learning from CUtLASS and CATIE. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(8):977–978. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.8.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huskamp HA, O'Malley AJ, Horvitz-Lennon M, Berndt ER, Donohue JM. How quickly do physicians adopt new drugs? the case of antipsychotics. Psychiatr Serv. 2012 doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200186. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leonhauser M. Antipsychotics: Multiple Indications Drive Growth. [November 12th, 2013];Market Watch. 2012 http://www.imshealth.com/ims/Global/Content/Corporate/Press Room/IMS in the News/Documents/PM360_IMS_Antipsychotics_0112.pdf.

- 22.Alexander GC, Gallagher SA, et al. Increasing off-label use of antipsychotic medications in the United States, 1995-2008. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Safety. 2011;20(2):177–184. doi: 10.1002/pds.2082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leslie DL, Mohamed S, Rosenheck RA. Off-label use of antipsychotic medications in the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(9):1175–1181. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.9.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nyweide DJ, Weeks WB, Gottlieb DJ, et al. Relationship of primary care physicians’ patient caseload with measurement of quality and cost performance. JAMA. 2009;302(22):2444–2450. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Association of American Medical Colleges [August 9th, 2013];Organizational Characteristics Database. https://http://www.aamc.org/data/ocd/.

- 26.American Medical Student Association [July 20th, 2013];AMSA PharmFree Scorecard 2013. 2013 http://www.amsascorecard.org.

- 27.Institute on Medicine as a Profession [March 3, 2014];IMAP Conflict of Interest Database. 2014 http://www.imapny.org/conflicts_of_interest/search-policies.

- 28.Schneeweiss S, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Solomon DH. A Medicare database review found that physician preferences increasingly outweighed patient characteristics as determinants of first-time prescriptions for COX-2 inhibitors. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2005;58(1):98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamann J, Adjan S, Leucht S, Kissling W. Psychiatric decision making in the adoption of a new antipsychotic in Germany. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(5):700–703. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.5.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoblyn J, Noda A, Yesavage JA, et al. Factors in choosing atypical antipsychotics: Toward understanding the bases of physicians’ prescribing decisions. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2006;40(2):160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gelman A, Hill J. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. Cambridge University Press; 2007. p. 321. Chapter 14. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoffmann TC, Montori VM, Mar CD. The Connection Between Evidence-Based Medicine and Shared Decision Making. JAMA. 2014;312(13):1295–1296. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.10186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donohue JM, O'Malley AJ, Horvitz-Lennon M, Taub AL, Berndt ER, Huskamp HA. Changes in physician antipsychotic prescribing preferences, 2002-2007. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(3):315–322. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Donohue JM, Berndt ER, Rosenthal M, Epstein AM, Frank RG. Effects of pharmaceutical promotion on adherence to the treatment guidelines for depression. Med Care. 2004;42(12):1176–1185. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dusetzina SB, Busch AB, Conti RM, Donohue JM, Alexander GC, Huskamp HA. Changes in antipsychotic use among patients with severe mental illness after a Food and Drug Administration advisory. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(12):1251–60. doi: 10.1002/pds.3272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Korn D, Carlat D. Conflicts of Interest in Medical Education Recommendations From the Pew Task Force on Medical Conflicts of Interest. JAMA. 2013;310:2397–2398. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ornstein C. [October 5, 2014];Our First Dive Into the New Open Payments System. 2014 http://www.propublica.org/article/our-first-dive-into-the-new-open-payments-system.

- 38.Stossel T. Has the hunt for conflicts of interest gone to far? Yes. BMJ. 2008;336:476. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39493.489213.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dana J, Loewenstein G. A social science perspective on gifts to physicians from industry. JAMA. 2010;290:252–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.2.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenthal MB, Berndt ER, Donohue JM, Frank RG, Epstein AM. Promotion of prescription drugs to consumers. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346(7):498–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.