Abstract

This article is one of ten reviews selected from the Annual Update in Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine 2015 and co-published as a series in Critical Care. Other articles in the series can be found online at http://ccforum.com/series/annualupdate2015. Further information about the Annual Update in Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine is available from http://www.springer.com/series/8901.

Introduction

Systemic vasodilatation and arterial hypotension are landmarks of septic shock. Whenever fluid resuscitation fails to restore arterial blood pressure and tissue perfusion, vasopressors agents are necessary [1]. Norepinephrine, a strong α-adrenergic agonist, is the standard vasopressor to treat septic shock-induced hypotension [1]. Adrenergic vasopressors have been associated with several detrimental effects, including organ dysfunction and increased mortality [2,3]. Therefore, alternative agents have been proposed, yet with disappointing results so far [4].

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) provides an important physiologic mechanism to prevent systemic hypotension under hypovolemic conditions, such as unresuscitated septic shock [5]. In addition to its classical hemodynamic function of regulating arterial blood pressure, angiotensin II plays a key role in several biological processes, including cell growth, apoptosis, inflammatory response, and coagulation. It may also affect mitochondrial function [6,7].

This review briefly discusses the main physiological functions of the RAS, and presents recent evidence suggesting a role for exogenous angiotensin II administration as a vasopressor in septic shock.

The renin-angiotensin system

Since the discovery of renin by Robert Tigerstedt and Per Gunnar Bergman in 1898, a lot of progress has been made towards better understanding of the role of the RAS in body homeostasis and in disease. The classical circulating RAS includes angiotensinogen (the precursor of angiotensin), the enzymes renin and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), which produces the bioactive angiotensin II, and its receptors, AT-1 and AT-2. Aldosterone is often considered together with the circulating RAS, then referred to as the RAAS (renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system). The major components of the classical ‘circulating’ RAS were described at the beginning of the 1970s. In the subsequent decades, knowledge about angiotensin receptors and the complex interaction between the RAS and other neuroendocrine pathways has increased [5]. One of the most remarkable advances has been the discovery of a tissue (or local) RAS, and more recently, the discovery of an intracellular RAS [8].

The local RAS contains all the components of the circulating RAS and exerts different functions in different organs. The local RAS has been identified in heart, brain, kidney, pancreas, and lymphatic and adipose tissues. It can operate independently, as in the brain, or in close connection with the circulating RAS, as in the kidneys and the heart [5]. While the circulating RAS is mainly responsible for blood pressure control and fluid and electrolyte homeostasis, the local RAS is predominantly related to inflammatory processes, modulating vascular permeability, apoptosis, cellular growth, migration and differentiation [6].

Agiontensin II production

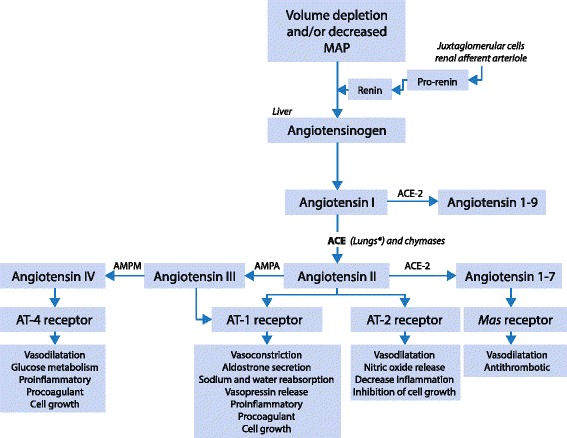

Juxtaglomerular cells of the renal afferent arteriole are responsible for renin synthesis. Renin, a proteolytic enzyme, is stored as an inactive form, called pro-renin. Extracellular fluid volume depletion and/or decreased arterial blood pressure trigger several enzymatic reactions resulting in the release of active renin into surrounding tissues and the systemic circulation. However, renin has no hemodynamic effects (Figure 1) [8].

Figure 1.

Overview of the renin-angiotensin system. MAP: mean arterial blood pressure; AT: angiotensin; ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; AMPA: aminopeptidase A; AMPM: aminopeptidase M; *: ACE is present mainly in lung capillaries, although it can also be found in the plasma and vascular beds of other organs, such as the kidneys, brain, heart and skeletal muscle.

Angiotensin I, a decapeptide with weak biological activity, is produced from angiotensinogen, an α2-globulin produced primarily in the liver and, to a lesser extent, in the kidneys and other organs. Angiotensin is rapidly converted to angiotensin II by an ACE and, to a lesser extent, by other chymases stored in secretory granules of mast cells. Angiotensin II, an octapeptide, has strong vasopressor activity [8].

ACE is present mainly in lung capillaries, although it can also be found in the plasma and vascular beds of other organs, such as the kidneys, brain, heart and skeletal muscle. The action of angiotensin II is terminated by its rapid degradation into angiotensin 2–8 heptapeptide (angiotensin III) and ultimately into angiotensin 3–8 heptapeptide (angiotensin IV) by aminopeptidases A and M, respectively [8]. ACE-2 is a carboxypeptidase responsible for the production of angiotensin 1–9 from angiotensin I and angiotensin 1–7 from angiotensin II [9,10]. Angiotensin 1–7 is a heptapeptide, which produces vasodilatation mediated by its interaction with the prostaglandin-bradykinin-nitric oxide system [10].

The balance between ACE and ACE-2 may play an important role in cardiovascular pathophysiology by modulating and controlling angiotensin II blood concentrations. The RAS is primary regulated by a negative feedback effect of angiotensin II on renin production by the juxtaglomerular cells of the renal afferent arteriole [5].

Angiotensin II receptors

The physiological effects of angiotensin II result from its binding to specific G protein-coupled receptors. So far, four angiotensin receptors have been described: AT-1, AT-2, AT-4 and Mas [11]. Additionally, two isoforms of AT-1 receptors (AT-1a and AT-1b) have been identified in rodents [12,13]. It has been postulated that human cells express only AT-1a receptors, located in the kidneys, vascular smooth muscle, heart, brain, adrenals, pituitary gland, liver and several other organs and tissues [11].

The major physiological activities of angiotensin II are mediated by AT-1 receptors. Thereby, angiotensin II acts to control arterial blood pressure, aldosterone release by the adrenal zona glomerulosa, sodium and water reabsorption in the proximal tubular cells, and vasopressin secretion (Figure 1) [14]. When chronically stimulated, AT-1 receptors have been shown to mediate cardiac hypertrophy and induce cardiac remodeling [15].

The function of AT-2 receptors in adults has not been completely determined and some authors suggest that their stimulation might counteract the AT-1 effects on blood pressure regulation, inflammation and cell growth [11]. Indeed, angiotensin II binding to AT-2 receptors results in vasodilatation and decreased systemic vascular resistance (Figure 1) [5].

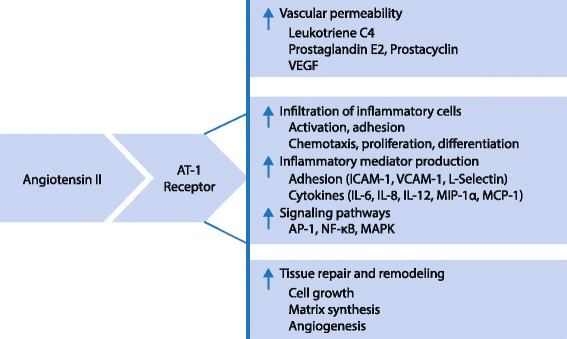

A large number of experimental studies have shown that angiotensin II mediates countless key elements of inflammatory processes [6] (Figure 2). By binding to AT-1 receptors, angiotensin II enhances the expression of proinflammatory mediators, increases vascular permeability by inducing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and stimulates the expression of endothelial adhesion molecules (P-selectin and E-selectin), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) (Figure 2) [6]. Angiotensin II also promotes reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, cell growth, apoptosis, angiogenesis, endothelial dysfunction, cell migration and differentiation, leukocyte rolling, adhesion and migration, extracellular matrix remodeling. Finally, it can play a role in multiple intracellular signaling pathways leading to organ and mitochondrial injury [16].

Figure 2.

Key potential mechanism attributed to angiotensin II’s action via AT-1 receptors. AT-1: angiotensin receptor 1; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; ICAM-1: intercellular adhesion molecule-1; VCAM-1: vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; IL: interleukin; MIP-1α: macrophage inflammatory protein-1α; MCP-1: monocyte chemotactic protein-1; AP-1: activating protein-1; NF-κB: nuclear factor-kappa B; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase.

The renin-angiotensin system in sepsis

Activation of the RAS during sepsis is a well know phenomenon, observed in experimental [17] and clinical studies [18-20]. However, so far, most of our knowledge about the RAS system during septic shock has come from a few experimental studies performed with healthy rodents [17,21-26], sheep [27,28] or pigs [7]. The role of exogenous angiotensin II administration or its inhibition in sepsis is poorly understood [29].

Unresuscitated septic shock is characterized by marked hypovolemia, extracellular fluid volume depletion, decreased cardiac output, low arterial blood pressure and decreased systemic vascular resistance [30]. Septic shock triggers a complex neuro-humoral response, releasing several vasoactive substances in the circulation [31]. Four main mechanisms are involved in effective circulating volume and arterial blood pressure restoration in septic shock [32]. These mechanisms are sympathetic nervous system activation, the release of arginine vasopressin by the posterior pituitary gland, inhibition of atrial and cerebral natriuretic peptide secretion from the atria of the heart, and the increase in renin secretion by the juxtaglomerular cells, resulting in elevated angiotensin II plasma levels and an increased secretion of aldosterone from the adrenal cortex [32].

During sepsis, the activity of plasma renin, angiotensin I and angiotensin II are increased [19]. Despite the high angiotensin II plasma levels, pronounced hypotension, associated with a reduced vasopressor effect of angiotensin II, has been reported [17]. Moreover, RAS activation contributes to oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction [24], which has been associated with development of kidney [33] and pulmonary [25,26] injury and with the severity of organ dysfunction [19].

Data from experimental animal models have suggested that sepsis can induce a systemic downregulation of both AT-1 [21] and AT-2 receptors [22]. Proinflammatory cytokines, e.g., interleukin (IL)-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interferon (IFN)γ and nitric oxide (NO), released during Gram-positive and Gram-negative sepsis, downregulate AT-1 receptor expression. This leads to systemic hypotension and low aldosterone secretion despite increased plasma renin activity and angiotensin-II levels [21,22]. Very recently, it has been demonstrated that sepsis down-regulates the expression of an AT-1 receptor-associated protein (Arap1), which contributes to the development of hypotension secondary to reduced vascular sensitivity to angiotensin II [23]. Downregulation of adrenal AT-2 receptors may impair catecholamine release by the adrenal medulla and, thereby, play a critical role in the pathogenesis of sepsis-induced hypotension [22]. Mediators of the RAS have also been associated with microvascular dysfunction in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock [19].

Infusion of angiotensin II in septic shock

Some early observations suggested that angiotensin II may be used as an alternative vasopressor in cases of norepinephrine unresponsive septic shock [34-36]. The main concern about exogenous administration of angiotensin II in septic shock is related to its strong vasoconstrictor effect, which may impair regional blood flow and aggravate tissue perfusion. Angiotensin II binding to AT-1 receptors causes dose-dependent vasoconstriction of both afferent and efferent glomerular arterioles. Indeed, the most pronounced effect of angiotensin II occurs on efferent arterioles [37], resulting in reduced renal blood flow and increased glomerular filtration pressure [27].

Wan et al. demonstrated in a hyperdynamic sepsis model in conscious sheep that a six-hour infusion of angiotensin II was effective in restoring arterial blood pressure and increased urinary output and creatinine clearance, despite a marked decrease in renal blood flow [27]. In this study, mesenteric, coronary and iliac artery blood flow were also affected but to a lesser degree [27]. In a similar model in anesthetized sheep, the same group reported an equal decrease in renal blood flow in controls and angiotensin II treated animals, but renal conductance was lower in angiotensin II-treated animals [28].

We recently evaluated in pigs the long term effects of exogenous angiotensin II administration on systemic and regional hemodynamics, tissue perfusion, inflammatory response, coagulation and mitochondrial function [7]. In this study, 16 pigs were randomized to receive either norepinephrine or angiotensin II for 48 hours after a 12-hour period of untreated sepsis. An additional group was pre-treated with enalapril (20 mg/d orally) for one week prior to the experiment, and then with intravenous enalapril (0.02 mg/kg/h) until the end of the study. We found that angiotensin II was as effective as norepinephrine to restore arterial blood pressure, and cardiac output increased similarly as in animals resuscitated with norepinephrine. Renal plasma flow, incidence of acute kidney injury, inflammation and coagulation patterns did not differ between the two groups [7]. However, enalapril-treated animals did not achieve the blood pressure targets despite receiving high norepinephrine doses (approximately 2.0 mcg/kg/min), and they had a higher incidence of acute kidney injury at the end of the study [7].

Our data demonstrate that the effects of angiotensin II on regional perfusion are different in vasodilatatory states compared to normal conditions: in healthy pigs, angiotensin II infusion resulted in net reduction of renal blood flow, while portal blood flow decreased in parallel with cardiac output, and fractional blood flow increased dose-dependently in carotid, hepatic and femoral arteries [38]. As in sepsis, angiotensin II infusion had no effects on diuresis or creatinine clearance [38]. The discrepant findings on renal perfusion can be explained by sepsis-induced hyporeactivity of the renal arteries [39]. It seems, therefore, that organ perfusion is not at risk in experimental septic shock treated with angiotensin II.

Currently, a few studies are recruiting septic patients for evaluation of the effects of angiotensin II as a vasopressor (Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT00711789 and NCT01393782).

Angiotensin II and mitochondrial function

In sepsis, mitochondrial dysfunction occurs, but its relevance in the development of organ failure is unclear [40]. Angiotensin II itself can stimulate mitochondrial ROS production in endothelial cells [41] and alter cardiac mitochondrial electron transport chains [15].

Evidence has indicated a direct interaction between angiotensin II and mitochondrial components [42-45]. In a study using 125 I-labeled angiotensin II in rats, angiotensin II was detected in the mitochondria and nuclei of the heart, brain and smooth muscle cells [42,43]. In rat adrenal zona glomerulosa, renin, angiotensinogen and ACE were detected within intramitochondrial dense bodies [44], and renin has been detected in the cytosol of cardiomyocyte cell lines [45]. However, we recently demonstrated that high-affinity angiotensin II binding sites are actually located in the mitochondria-associated membrane fraction of rat liver cells, but not in purified mitochondria [46]. Moreover, we found that angiotensin II had no effect on the function of isolated mitochondria at physiologically relevant concentrations [46]. It, therefore, seems unlikely that the effects of angiotensin II on cellular energy metabolism are mediated through its direct binding to mitochondrial targets.

In septic pigs, a 48-hour angiotensin II infusion did not affect kidney, heart or liver mitochondrial respiration in comparison to norepinephrine-treated animals [7]. Although other mitochondrial functions, such as ROS production or enzymatic activity, were not assessed in this study, it seems unlikely that angiotensin II diminishes oxygen consumption in sepsis.

Conclusion

The RAS plays a key role in fluid and electrolyte homeostasis, arterial blood pressure and blood flow regulation. A better understanding of its complex interactions with other neuroendocrine regulating systems is crucial for the development of new therapeutic options to treat septic shock. Angiotensin II is a powerful vasopressor in experimental septic shock, and has proved to be safe in the tested settings. Administration of angiotensin II as an alternative to norepinephrine should be further evaluated in clinical trials.

Declarations

Publication of this article was funded by SNF (Swiss National Science Foundation), grant no. 32003B_127619/1.

Abbreviations

- AMPA

Aminopeptidase A

- AMPM

Aminopeptidase M

- AP-1

Activating protein-1

- ARAP1

AT-1 receptor-associated protein

- AT

Angiotensin

- AT-1

Angiotensin receptor 1

- ICAM-1

Intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- IL

Interleukin

- MAP

Mean arterial blood pressure

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MCP-1

Monocyte chemotactic protein-1

- MIP-1α

Macrophage inflammatory protein-1α

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor-kappa B

- NO

Nitric oxide

- RAAS

Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

- RAS

Renin-angiotensin system

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- TNF

Tumor necrosis factor

- VCAM-1

Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Thiago D Corrêa, Email: thiagodct@gmail.com.

Jukka Takala, Email: jukka.takala@insel.ch.

Stephan M Jakob, Email: stephan.jakob@insel.ch.

References

- 1.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2012;41:580–637. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e83af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunser MW, Ruokonen E, Pettila V, et al. Association of arterial blood pressure and vasopressor load with septic shock mortality: a post hoc analysis of a multicenter trial. Crit Care. 2009;13:R181. doi: 10.1186/cc8167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Backer D, Aldecoa C, Njimi H, Vincent JL. Dopamine versus norepinephrine in the treatment of septic shock: a meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:725–730. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31823778ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russell JA, Walley KR, Singer J, et al. Vasopressin versus norepinephrine infusion in patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:877–887. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fyhrquist F, Saijonmaa O. Renin-angiotensin system revisited. J Intern Med. 2008;264:224–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.01981.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suzuki Y, Ruiz-Ortega M, Lorenzo O, Ruperez M, Esteban V, Egido J. Inflammation and angiotensin II. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;35:881–900. doi: 10.1016/S1357-2725(02)00271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Correa TD, Jeger V, Pereira AJ, Takala J, Djafarzadeh S, Jakob SM. Angiotensin II in septic shock: effects on tissue perfusion, organ function, and mitochondrial respiration in a porcine model of fecal peritonitis. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:e550–e559. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paul M, Poyan MA, Kreutz R. Physiology of local renin-angiotensin systems. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:747–803. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00036.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donoghue M, Hsieh F, Baronas E, et al. A novel angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) converts angiotensin I to angiotensin 1–9. Circ Res. 2000;87:E1–E9. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.87.5.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santos RA, Ferreira AJ. Angiotensin-(1–7) and the renin-angiotensin system. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2007;16:122–128. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328031f362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhuo JL, Li XC. New insights and perspectives on intrarenal renin-angiotensin system: focus on intracrine/intracellular angiotensin II. Peptides. 2011;32:1551–1565. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sasamura H, Hein L, Krieger JE, Pratt RE, Kobilka BK, Dzau VJ. Cloning, characterization, and expression of two angiotensin receptor (AT-1) isoforms from the mouse genome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;185:253–259. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(05)80983-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwai N, Inagami T. Identification of two subtypes in the rat type I angiotensin II receptor. FEBS Lett. 1992;298:257–260. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80071-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lavoie JL, Sigmund CD. Minireview: overview of the renin-angiotensin system – an endocrine and paracrine system. Endocrinology. 2003;144:2179–2183. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larkin JE, Frank BC, Gaspard RM, Duka I, Gavras H, Quackenbush J. Cardiac transcriptional response to acute and chronic angiotensin II treatments. Physiol Genomics. 2004;18:152–166. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00057.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benigni A, Cassis P, Remuzzi G. Angiotensin II revisited: new roles in inflammation, immunology and aging. EMBO Mol Med. 2010;2:247–257. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201000080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schaller MD, Waeber B, Nussberger J, Brunner HR. Angiotensin II, vasopressin, and sympathetic activity in conscious rats with endotoxemia. Am J Physiol. 1985;249:H1086–H1092. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1985.249.6.H1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamion F, Le Cam-Duchez V, Menard JF, Girault C, Coquerel A, Bonmarchand G. Erythropoietin and renin as biological markers in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2004;R328–R335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Doerschug KC, Delsing AS, Schmidt GA, Ashare A. Renin-angiotensin system activation correlates with microvascular dysfunction in a prospective cohort study of clinical sepsis. Crit Care. 2010;14:R24. doi: 10.1186/cc8887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hilgenfeldt U, Kienapfel G, Kellermann W, Schott R, Schmidt M. Renin-angiotensin system in sepsis. Clin Exp Hypertens A. 1987;9:1493–1504. doi: 10.3109/10641968709158998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bucher M, Ittner KP, Hobbhahn J, Taeger K, Kurtz A. Downregulation of angiotensin II type 1 receptors during sepsis. Hypertension. 2001;38:177–182. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.38.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bucher M, Hobbhahn J, Kurtz A. Nitric oxide-dependent down-regulation of angiotensin II type 2 receptors during experimental sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1750–1755. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200109000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mederle K, Schweda F, Kattler V, et al. The angiotensin II AT1 receptor-associated protein Arap1 is involved in sepsis-induced hypotension. Crit Care. 2013;17:R130. doi: 10.1186/cc12809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lund DD, Brooks RM, Faraci FM, Heistad DD. Role of angiotensin II in endothelial dysfunction induced by lipopolysaccharide in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H3726–H3731. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01116.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Imai Y, Kuba K, Rao S, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protects from severe acute lung failure. Nature. 2005;436:112–116. doi: 10.1038/nature03712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein N, Gembardt F, Supe S, et al. Angiotensin-(1–7) protects from experimental acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:e334–e343. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828a6688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wan L, Langenberg C, Bellomo R, May CN. Angiotensin II in experimental hyperdynamic sepsis. Crit Care. 2009;13:R190. doi: 10.1186/cc8185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.May CN, Ishikawa K, Wan L, et al. Renal bioenergetics during early gram-negative mammalian sepsis and angiotensin II infusion. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:886–893. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2487-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salgado DR, Rocco JR, Silva E, Vincent JL. Modulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in sepsis: a new therapeutic approach? Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2010;14:11–20. doi: 10.1517/14728220903460332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Correa TD, Vuda M, Blaser AR, et al. Effect of treatment delay on disease severity and need for resuscitation in porcine fecal peritonitis. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2841–2849. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31825b916b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cuesta JM, Singer M. The stress response and critical illness: a review. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:3283–3289. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31826567eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rolih CA, Ober KP. The endocrine response to critical illness. Med Clin North Am. 1995;79:211–224. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)30093-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.du Cheyron D, Lesage A, Daubin C, Ramakers M, Charbonneau P. Hyperreninemic hypoaldosteronism: a possible etiological factor of septic shock-induced acute renal failure. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:1703–1709. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1986-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas VL, Nielsen MS. Administration of angiotensin II in refractory septic shock. Crit Care Med. 1991;19:1084–1086. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199108000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wray GM, Coakley JH. Severe septic shock unresponsive to noradrenaline. Lancet. 1995;346:1604. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)91933-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yunge M, Petros A. Angiotensin for septic shock unresponsive to noradrenaline. Arch Dis Child. 2000;82:388–389. doi: 10.1136/adc.82.5.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Denton KM, Anderson WP, Sinniah R. Effects of angiotensin II on regional afferent and efferent arteriole dimensions and the glomerular pole. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;279:R629–R638. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.2.R629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pereira AJ, Jeger V, Fahrner R, et al. Interference of angiotensin II and enalapril with hepatic blood flow regulation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;307:G655–663. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00150.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu HP, Hsu JC, Yen CH, Ma YH, Lau YT. Hyporeactivity of renal artery to angiotensin II in septic rats. Chin J Physiol. 2008;51:301–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jeger V, Djafarzadeh S, Jakob SM, Takala J. Mitochondrial function in sepsis. Eur J Clin Invest. 2013;43:532–542. doi: 10.1111/eci.12069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kimura S, Zhang GX, Nishiyama A, et al. Mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species and vascular MAP kinases: comparison of angiotensin II and diazoxide. Hypertension. 2005;45:438–444. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000157169.27818.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robertson AL, Jr, Khairallah PA. Angiotensin II: rapid localization in nuclei of smooth and cardiac muscle. Science. 1971;172:1138–1139. doi: 10.1126/science.172.3988.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sirett NE, McLean AS, Bray JJ, Hubbard JI. Distribution of angiotensin II receptors in rat brain. Brain Res. 1977;122:299–312. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90296-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peters J, Kranzlin B, Schaeffer S, et al. Presence of renin within intramitochondrial dense bodies of the rat adrenal cortex. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:E439–E450. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.271.3.E439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wanka H, Kessler N, Ellmer J, et al. Cytosolic renin is targeted to mitochondria and induces apoptosis in H9c2 rat cardiomyoblasts. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:2926–2937. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00448.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Astin R, Bentham R, Djafarzadeh S, et al. No evidence for a local renin-angiotensin system in liver mitochondria. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2467. doi: 10.1038/srep02467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]